Chapter 16. Using Wine

Although Ubuntu supports a wealth of different applications, spanning just about any subject you can think of, there are still occasions when it may not completely meet your needs. For example, OpenOffice.org is a fully featured office suite, providing all the functions you would expect and that exist in other similar applications such as Microsoft Office. And it can even read and write Office files. But it isn’t totally compatible with Office, because many documents display and print differently in the two packages.

And why should OpenOffice.org be fully compatible? It’s a completely different program that’s been independently developed and approaches things in different ways that are completely logical in its own frame of reference. Once you get used to it, you can produce documents, spreadsheets, and presentations that are easily the equal of any you can create in Office.

But what if you have to collaborate on documents with someone who uses Office, while you use OpenOffice.org? You will almost certainly find that you both introduce changes that don’t display correctly on each other’s computers. They may be little things like changed tab settings, different page lengths, and so on, but these little things are also time-consuming to fix.

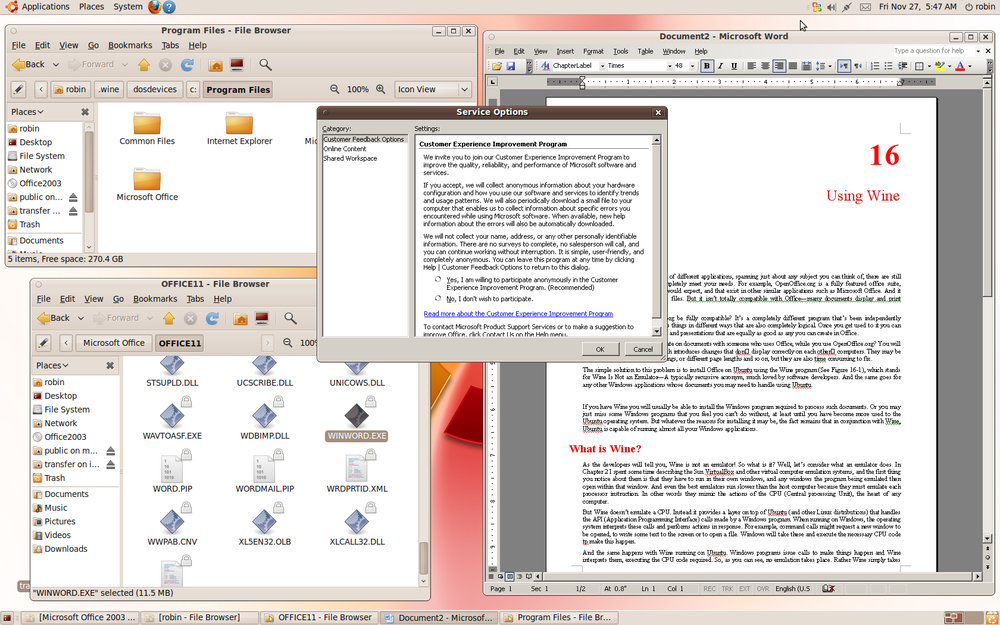

The simple solution to this problem is to install Office on Ubuntu using the Wine program (see Figure 16-1), which stands for Wine Is Not an Emulator—a typically recursive acronym, much loved by software developers. And the same goes for any other Windows applications whose documents you may need to handle using Ubuntu. If you have Wine, you’ll usually be able to install the Windows program required to process such documents.

Or you may just miss some Windows programs that you feel you can’t do without, at least until you have become more used to the Ubuntu operating system. But whatever the reasons, the fact remains that in conjunction with Wine, Ubuntu is capable of running almost all your Windows applications.

What Is Wine?

As the developers will tell you, Wine is not an emulator! So, what is it? Well, let’s consider what an emulator does. In Chapter 2, I spent some time describing the Sun VirtualBox (and other virtual computer emulation systems). The first thing you notice about them is that they have to run in their own windows, which in turn contain the windows running the programs they emulate.

And even the best virtual machines run slower than the host computer because they must emulate each processor instruction. In other words, they mimic the actions of the central processing unit (CPU), the hardware at the heart of any computer.

But Wine doesn’t emulate a CPU. Instead, it provides a layer on top of Ubuntu (and other Linux distributions) that handles the application programming interface (API) calls made by a Windows program. When running on Windows, the operating system interprets these calls and performs actions in response. For example, calls might request a new window to be opened, to write some text to the screen, or to open a file, and Windows will interpret these and execute the necessary CPU machine code to make this happen.

And the same happens with Wine when running on Ubuntu. Windows programs issue calls to make things happen and Wine interprets them, executing the CPU code required, and no emulation takes place. Rather, Wine simply takes the place of Windows in providing resources to Windows programs running on Ubuntu. And because of this, Wine can run these programs natively, at the fastest possible speed.

The Benefits of Wine

Wine offers many benefits compared to running Windows within a virtual machine emulator such as VirtualBox, the first being cost. With an emulator you must install a full version of a Windows operating system, which requires you to pay for a license. On the other hand, Wine is free to use. (However, if you use Microsoft Office or other commercial programs in Wine, you need licenses for those programs to run them legally.)

Another benefit of Wine is that it integrates with the Ubuntu desktop, which means that you can run Windows and Linux programs alongside one another, both as full-speed native applications, and with full copy and paste integration between the two.

If you look again at Figure 16-1, you’ll see that the top-left window contains the Ubuntu File Browser, which is currently displaying the folders in a new C: drive that Wine has created. Below this, the OFFICE11 folder on that drive is also being displayed, showing WINWORD.EXE, which has just been clicked, calling up the Microsoft Word program shown in the window to the right.

The small window on top of them all is for Microsoft’s Customer Experience Improvement program. It has been called up by clicking the icon that was added to the top status bar, which normally would have been added to a Windows computer’s system tray. So as you can see, Ubuntu and Windows programs integrate with each other seamlessly when Wine is installed.

Wine’s Limitations

Wine is still in development, and as long as there are new versions of Windows, it probably always will be, so there are known issues with the application. Although the majority of Windows software will run correctly with it, there are some programs that you may have problems with or that will simply refuse to work. Among these are various versions of iTunes, some games that rely on obscure Windows features, and so on.

The only way of knowing for certain whether a particular Windows program will work with Wine is to install it and test it for yourself. If it doesn’t run correctly, maybe a future release of Wine will fix the problem. Just try another program instead, and consider that it’s pretty amazing that Wine can run the number of programs it does.

Installing Wine

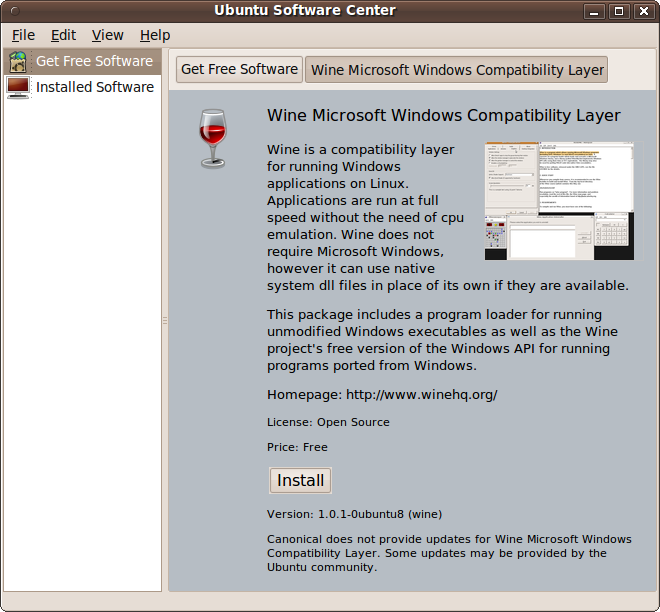

To install Wine, call up the Ubuntu Software Center and enter “wine” into the search field. This should result in three or so matching applications. You should double-click the first one, Wine Microsoft Windows Compatibility Layer, as shown in Figure 16-2.

Warning

Unless you wish to become a beta tester, you should not install any version marked as a beta release, because it could be unstable and may crash.

This will bring up the description shown in Figure 16-3. When you are ready to install the program, click the Install button and enter your password if prompted. The installation process may take a while, depending on the speed of your Internet connection, and the progress bar may appear to stall, but be patient and wait for it to complete.

When finished, you can now install your Windows programs. For example, to install Microsoft Office, insert the disc into the drive, and it will be mounted onto the desktop. Double-click the mounted disc, and then double-click SETUPPRO.EXE (or whatever the setup file in your version is called). You can then follow through with the installation, in the same way as if you are using Windows.

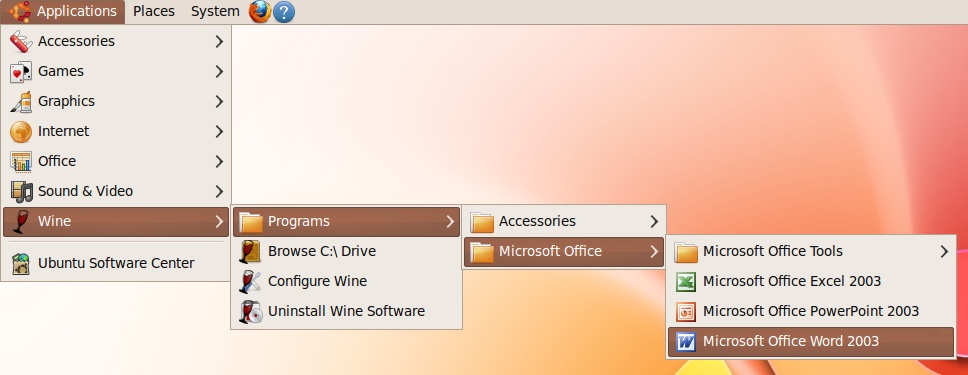

Once installed, you can run a program from its folder or use the Applications → Wine → Programs menu to open it (see Figure 16-4), although you may need to restart your computer to make new entries appear there.

There’s no Add/Remove Programs control panel, because Wine is not a full implementation of Windows. Just use Applications → Wine → Uninstall Wine Software to uninstall any Windows programs you no longer need.

Installing Microsoft Fonts

If the fonts used by Windows programs don’t look right to you, you might not have the Microsoft core fonts installed. This is easy enough to fix by entering the following command into a Terminal window, and then entering your password when prompted:

sudo apt-get install msttcorefontsEither the fonts will install and you can now close and reopen your Windows programs to use them, or you’ll be informed that you already have them.

Note

Microsoft originally licensed these core fonts for anyone to use freely, regardless of their operating system. This Web Fontpack, as it was called, was meant to help boost the market share of Internet Explorer. However, after IE became the dominant browser, these files were removed from the Microsoft website. Nevertheless, the End User License Agreement (EULA) continues to allow redistribution as long as the packages are kept in their original format and are not sold for profit. The license details are viewable on Microsoft’s website at http://microsoft.com/typography/fontpack/eula.htm.

Configuring Wine

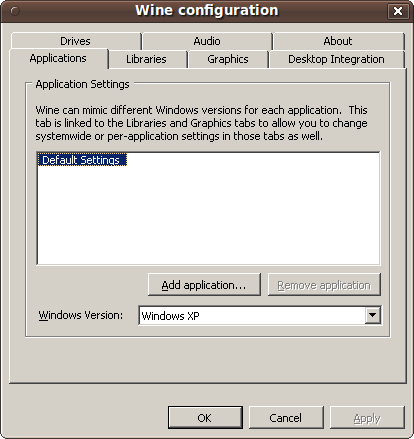

You can configure Wine to your preferences by selecting Applications → Wine → Configure Wine. This will open up the window shown in Figure 16-5, which is actually a Windows application itself running under Wine.

The utility displays seven tabs offering many options, including adding and removing applications, adding Dynamic Link Libraries (DLLs) to override Wine libraries, handling DirectX and Direct3D, managing themes, mapping disc drives, configuring audio, and more.

Some of these functions, such as adding DLLs, require a solid knowledge of how Windows works, so you shouldn’t use them unless you know why you are doing so.

Accessing the Windows C: Drive

Wine emulates a Windows computer’s C: drive by creating a collection of folders within your home folder, starting with the subfolder .wine. So, C:\ is actually located at ~/.wine/dosdevices/c:.

So, for example, to change to the emulated c:\Program Files folder using the Terminal, you would enter the following command (remembering that you need quotation marks around any nonalphanumeric characters):

cd ~/.wine/dosdevices/c:/"Program Files"You can also use the Nautilus file manager to browse the emulated drive by selecting Applications → Wine → Browse C:\ Drive.

Further Information

Wine is maintained and developed by the Wine Project. There, you can get assistance, report bugs, and make suggestions. I also recommend you view the wiki at http://wiki.winehq.org, which details everything you could want to know about the program and the project.

Summary

You have now come to the end of your journey to get Ubuntu up and running. I hope you have enjoyed the ride and will tell your friends, family, and colleagues just how easy and yet how powerful Ubuntu is.

If you like, come and visit this book’s web page at http://ubuntubook.net, where you can also leave your comments about Ubuntu and this book. I’m always pleased to hear from readers, and do my best to help with any problems.