Integer Mathematics

Abstract

This chapter introduces the concept of high performance mathematics. The chapter starts by explaining basic math in bases other than 10. It explains subtraction using complement mathematics. Next it gives efficient algorithms for performing signed and unsigned multiplication in binary. It explains how multiplication by a constant can often be converted into a much more efficient sequence of shift and add or subtract operations, and gives a method for multiplying two arbitrarily large numbers. Next, an efficient algorithm is given for binary division, followed by a technique for converting division by a constant into multiplication by a related constant. The next section introduces an ADT, written in C, which can be used to perform basic mathematical operations on integers of any size. The chapter concludes by showing that the ADT can be made much more efficient by replacing some of the functions with assembly language implementations.

Keywords

Addition; Subtraction; Complement; Multiplication; Division; Big integer; High performance; Abstract data type

There are some differences between the way calculations are performed in a computer versus the way most of us were taught as children. The first difference is that calculations are performed in binary instead of base ten. Another difference is that the computer is limited to a fixed number of binary digits, which raises the possibility of having a result that is too large to fit in the number of bits available. This occurrence is referred to as overflow. The third difference is that subtraction is performed using complement addition.

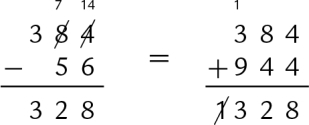

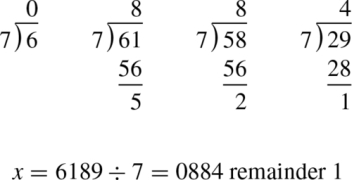

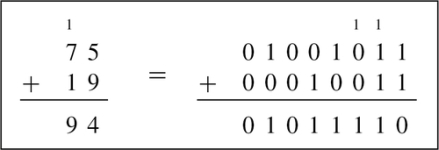

Addition in base b is very similar to base ten addition, except that the result of each column is limited to b − 1. For example, binary addition works exactly the same as decimal addition, except that the result of each column is limited to 0 or 1. The following figure shows an addition in base ten and the equivalent addition in base two.

The carry from one column to the next is shown as a small number above the column that it is being carried into. Note that carries from one column to the next are done the same way in both bases. The only difference is that there are more columns in the base two addition because it takes more digits to represent a number in binary than it does in decimal.

7.1 Subtraction by Addition

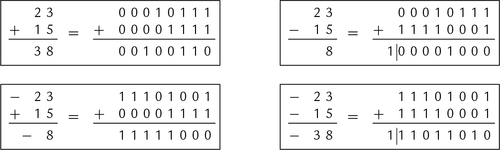

Finding the complement was explained in Section 1.3.3. Subtraction can be computed by adding the radix complement of the subtrahend to the menuend. Example 7.1 shows a complement subtraction with positive results. When x < y, the result will be negative. In the complement method, this means that there will be a ‘1’ in the most significant bit, and in order to convert the result to base ten, we must take the radix complement. Example 7.2 shows complement subtraction with negative results. Example 7.3 shows several more signed addition and subtraction operations in base ten and binary.

7.2 Binary Multiplication

Many processors have hardware multiply instructions. However hardware multipliers require a large number of transistors, and consume significant power. Processors designed for extremely low power consumption or very small size usually do not implement a multiply instruction, or only provide multiply instructions that are limited to a small number of bits. On these systems, the programmer must implement multiplication using basic data processing instructions.

7.2.1 Multiplication by a Power of Two

If the multiplier is a power of two, then multiplication can be accomplished with a shift to the left. Consider the 4-bit binary number x = x3 × 23 + x2 × 22 + x1 × 21 + x0 × 20, where xn denotes bit n of x. If x is shifted left by one bit, introducing a zero into the least significant bit, then it becomes  Therefore, a shift of one bit to the left is equivalent to multiplication by two. This argument can be extended to prove that a shift left by n bits is equivalent to multiplication by 2n.

Therefore, a shift of one bit to the left is equivalent to multiplication by two. This argument can be extended to prove that a shift left by n bits is equivalent to multiplication by 2n.

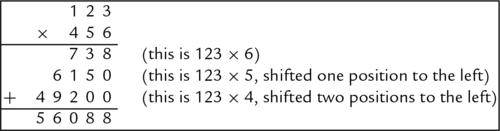

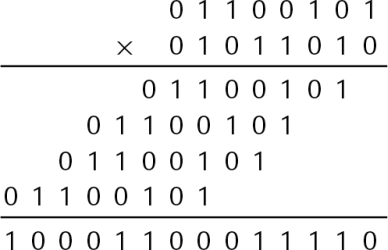

7.2.2 Multiplication of Two Variables

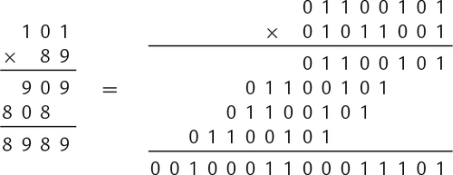

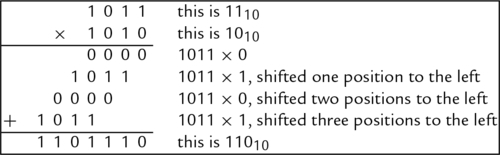

Most techniques for binary multiplication involve computing a set of partial products and then summing the partial products together. This process is similar to the method taught to primary schoolchildren for conducting long multiplication on base ten integers, but has been modified here for application to binary. The method typically taught in school for multiplying decimal numbers is based on calculating partial products, shifting them to the left and then adding them together. The most difficult part is to obtain the partial products, as that involves multiplying a long number by one base ten digit. The following example shows how the partial products are formed when multiplying 123 by 456.

The first partial product can be written as 123 × 6 × 100 = 738. The second is 123 × 5 × 101 = 6150, and the third is 123 × 4 × 102 = 49200. In practice, we usually leave out the trailing zeros. The procedure is the same in binary, but is simpler because the partial product involves multiplying a long number by a single base 2 digit. Since the multiplier is always either zero or one, the partial product is very easy to compute. The product of multiplying any binary number x by a single binary digit is always either 0 or x. Therefore, the multiplication of two binary numbers comes down to shifting the multiplicand left appropriately for each non-zero bit in the multiplier, and then adding the shifted numbers together.

Suppose we wish to multiply two four-bit numbers, 1011 and 1010:

Notice in the previous example that each partial sum is either zero or x shifted by some amount. A slightly quicker way to perform the multiplication is to leave out any partial sum which is zero. Example 7.4 shows the results of multiplying 10110 by 8910 in decimal and binary using this shorter method. For implementation in hardware and software, it is easier to accumulate the partial products, by adding each to a running sum, rather than building a circuit to add multiple binary numbers at once.

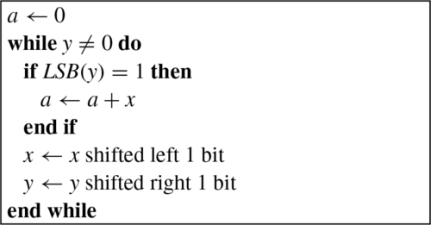

Binary multiplication can be implemented as a sequence of shift and add instructions. Given two registers, x and y, and an accumulator register a, the product of x and y can be computed using Algorithm 1. When applying the algorithm, it is important to remember that, in the general case, the result of multiplying an n bit number by an m bit number is (at most) an n + m bit number. For instance 112 × 112 = 10012. Therefore, when applying Algorithm 1, it is necessary to know the number of bits in x and y. Since x is shifted left on each iteration of the loop, the registers used to store x and a must both be at least as large as the number of bits in x plus the number of bits in y.

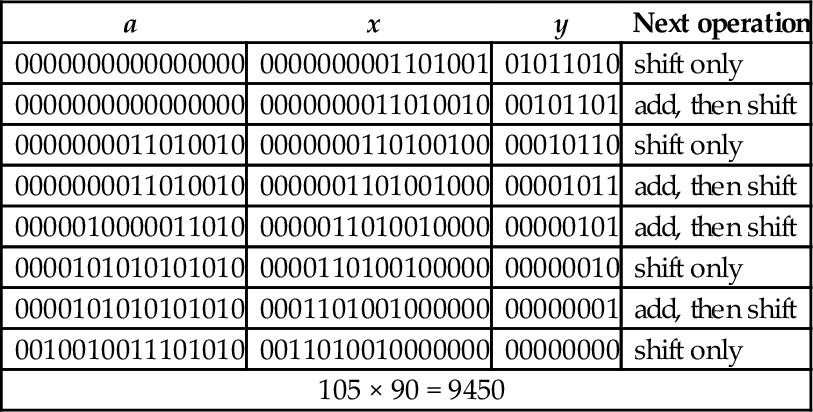

Assume we wish to multiply two numbers, x = 01101001 and y = 01011010. Applying Algorithm 1 results in the following sequence:

| a | x | y | Next operation |

| 0000000000000000 | 0000000001101001 | 01011010 | shift only |

| 0000000000000000 | 0000000011010010 | 00101101 | add, then shift |

| 0000000011010010 | 0000000110100100 | 00010110 | shift only |

| 0000000011010010 | 0000001101001000 | 00001011 | add, then shift |

| 0000010000011010 | 0000011010010000 | 00000101 | add, then shift |

| 0000101010101010 | 0000110100100000 | 00000010 | shift only |

| 0000101010101010 | 0001101001000000 | 00000001 | add, then shift |

| 0010010011101010 | 0011010010000000 | 00000000 | shift only |

| 105 × 90 = 9450 | |||

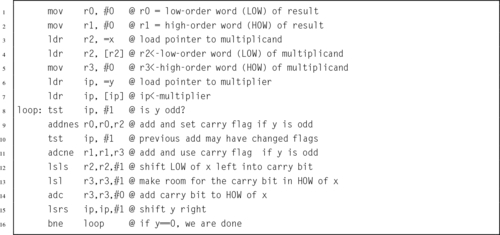

To multiply two n bit numbers, you must be able to add two 2n-bit numbers. On the ARM processor, n is usually assumed to be 32-bits, because that is the natural word size for the ARM processor. Adding 64-bit numbers requires two add instructions and the carry from the least-significant 32 bits must be added to the sum of the most-significant 32 bits. The ARM processor provides a convenient way to perform the add with carry. Assume we have two 64 bit numbers, x and y. We have x in r0, r1 and y in r2, r3, where the high order words of each number are in the higher-numbered registers, and we want to calculate x = x + y. Listing 7.1 shows a two instruction sequence for the ARM processor. The first instruction adds the two least-significant words together and sets (or clears) the carry bit and other flags in the CPSR. The second instruction adds the two most significant words along with the carry bit.

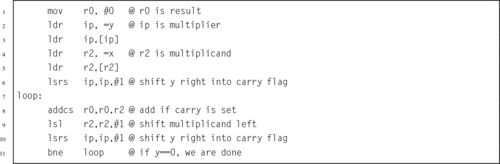

On the ARM processor, the algorithm to multiply two 32-bit unsigned integers is very efficient. Listing 7.2 shows one possible algorithm for multiplying two 32-bit numbers to obtain a 64-bit result. The code is a straightforward implementation of the algorithm, and some modifications can be made to improve efficiency. For example, if we only want a 32-bit result, we do not need to perform 64-bit addition. This significantly simplifies the code, as shown in Listing 7.3.

7.2.3 Multiplication of a Variable by a Constant

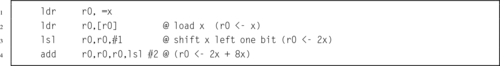

If x or y is a constant, then a loop is not necessary. The multiplication can be directly translated into a sequence of shift and add operations. This will result in much more efficient code than the general algorithm. If we inspect the constant multiplier, we can usually find a pattern to exploit that will save a few instructions. For example, suppose we want to multiply a variable x by 1010. The multiplier 1010 = 10102, so we only need to add x shifted left 1 bit to x shifted left 3 bits as shown below:

Now suppose we want to multiply a number x by 1110. The multiplier 1110 = 10112, so we will add x to x shifted left one bit plus x shifted left 3 bits as in the following:

If we wish to multiply a number x by 100010, we note that 100010 = 11111010002 It looks like we need one shift plus five add/shift operations, or six add/shift operations. With a little thought, the number of operations can be reduced from six to five as shown below:

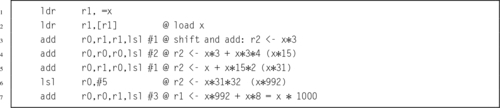

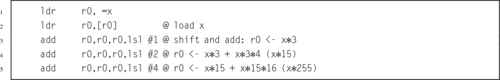

Applying the basic multiplication algorithm to multiply a number x by 25510 would result in seven add/shift operations, but we can do it with only three operations and use only one register, as shown below:

Most modern systems have assembly language instructions for multiplication, but hardware multiply units require a relatively large number of transistors. For that reason, processors intended for small embedded applications often do not have a multiply instruction. Even when a hardware multiplier is available, on some processors it is often more efficient to use shift, add, and subtract operations when multiplying by a constant. The hardware multiplier units that are available on most ARM processors are very powerful. They can typically perform multiplication with a 32-bit result in as little as one clock cycle. The long multiply instructions take between three and five clock cycles, depending on the size of the operands. Using the multiply instruction on an ARM processor to multiply by a constant usually requires loading the constant into a register before performing the multiply. Therefore, if the multiplication can be performed using three or fewer shift, add, and subtract instructions, then it will be equal to or better than using the multiply instruction.

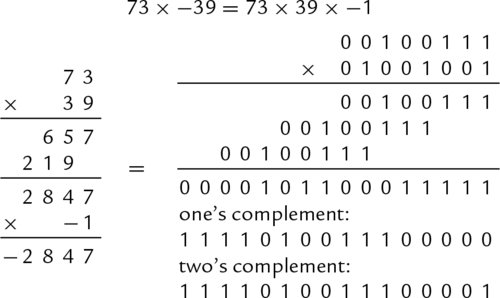

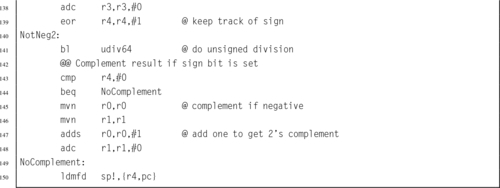

7.2.4 Signed Multiplication

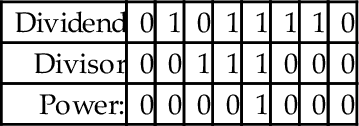

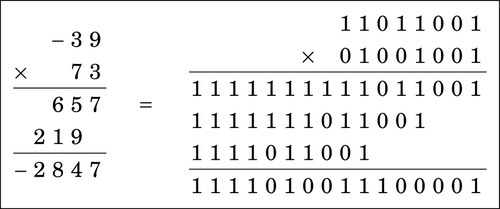

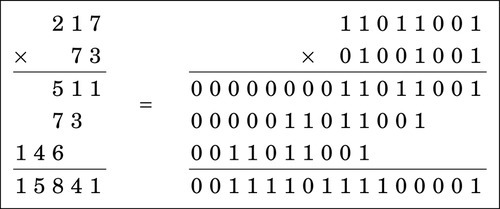

Consider the two multiplication problems shown in Figs. 7.1 and 7.2. Note that the result of a multiply depends on whether the numbers are interpreted as unsigned numbers or signed numbers. For this reason, most computer CPUs have two different multiply operations for signed and unsigned numbers.

If the CPU provides only an unsigned multiply, then a signed multiply can be accomplished by using the unsigned multiply operation along with a conditional complement. The following procedure can be used to implement signed multiplication.

1. if the multiplier is negative, take the two’s complement,

2. if the multiplicand is negative, take the two’s complement,

3. perform unsigned multiply, and

4. if the multiplier or multiplicand was negative (but not both), then take two’s complement of result.

Example 7.5 demonstrates this method using one negative number.

7.2.5 Multiplying Large Numbers

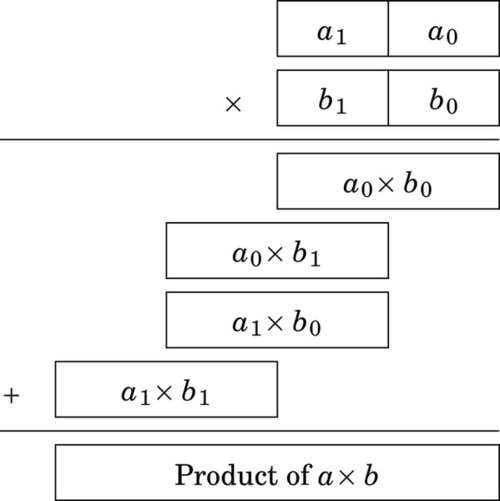

Consider the method used for multiplying two digit numbers is base ten, using only the one-digit multiplication tables. Fig. 7.3 shows how a two digit number a = a1 × 101 + a0 × 100 is multiplied by another two digit number b = b1 × 101 + b0 × 100 to produce a four digit result using basic multiplication operations which only take one digit from a and one digit from b at each step.

This technique can be used for numbers in any base and for any number of digits. Recall that one hexadecimal digit is equivalent to exactly four binary digits. If a and b are both 8-bit numbers, then they are also 2-digit hexadecimal numbers. In other words 8-bit numbers can be divided into groups of four bits, each representing one digit in base sixteen. Given a multiply operation that is capable of producing an 8-bit result from two 4-bit inputs, the technique shown above can then be used to multiply two 8-bit numbers using only 4-bit multiplication operations.

Carrying this one step further, suppose we are given two 16-bit numbers, but our computer only supports multiplying eight bits at a time and producing a 16-bit result. We can consider each 16-bit number to be a two digit number in base 256, and use the above technique to perform four eight bit multiplies with 16-bit results, then shift and add the 16-bit results to obtain the final 32-bit result. This approach can be extended to implement efficient multiplication of arbitrarily large numbers, using a fixed-sized multiplication operation.

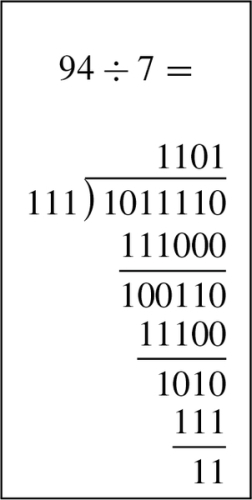

7.3 Binary Division

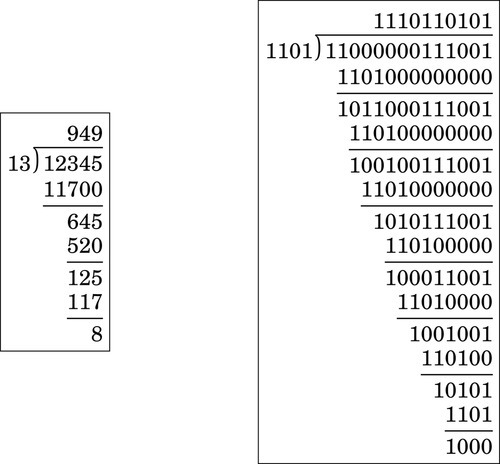

Binary division can be implemented as a sequence of shift and subtract operations. When performing binary division by hand, it is convenient to perform the operation in a manner very similar to the way that decimal division is performed. As shown in Fig. 7.4, the operation is identical, but takes more steps in binary.

7.3.1 Division by a Power of Two

If the divisor is a power of two, then division can be accomplished with a shift to the right. Using the same approach as was used in Section 7.2.1, it can be shown that a shift right by n bits is equivalent to division by 2n. However, care must be taken to ensure that an arithmetic shift is used if the numerator is a signed two’s complement number, and a logical shift is used if the numerator is unsigned.

7.3.2 Division by a Variable

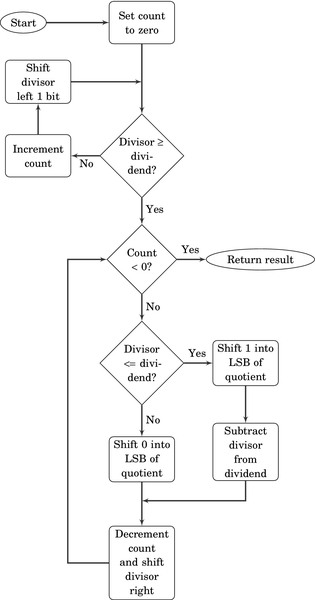

The algorithm for dividing binary numbers is somewhat more complicated than the algorithm for multiplication. The algorithm consists of two main phases:

1. shift the divisor left until it is greater than dividend and count the number of shifts, then

2. repeatedly shift the divisor back to the right and subtract whenever possible.

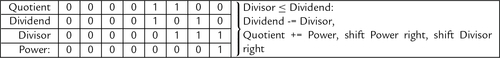

Fig. 7.5 shows the algorithm in more detail. Because of the complexity of the algorithm, division in hardware requires a significant number of transistors. The ARM architecture did not introduce a divide instruction until ARMv7, and even then it was not implemented on all processors. Many ARM systems (including the Raspberry Pi) do not have hardware division. However, the ARM processor instruction set makes it possible to write very efficient code for division.

Before we introduce the ARM code, we will take some time to step through the algorithm using an example. Let us begin by dividing 94 by 7. The result is shown below:

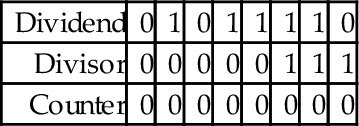

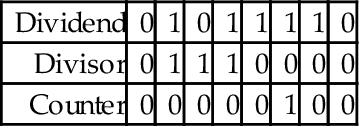

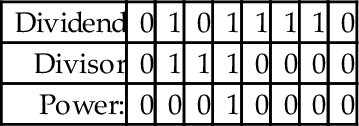

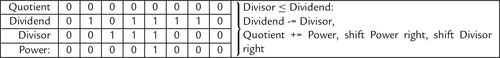

To implement the algorithm, we need three registers, one for the dividend, one for the divisor, and one for a counter. The dividend and divisor are loaded into their registers and the counter is initialized to zero as shown below:

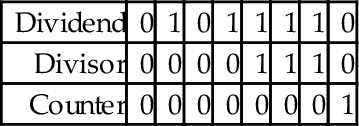

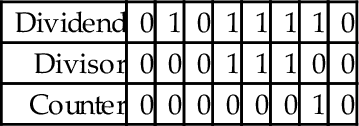

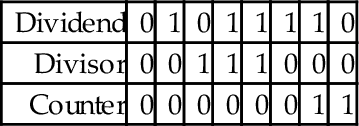

Next, the divisor is shifted left and the counter incremented repeatedly until the divisor is greater than the dividend. This is shown in the following sequence:

Next, we allocate a register for the quotient and initialize it to zero. Then, according to the algorithm, we repeatedly subtract if possible, shift to the right, and decrement the counter. This sequence continues until the counter becomes negative. For our example this results in the following sequence:

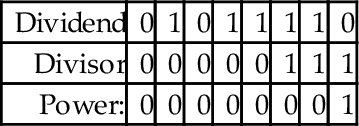

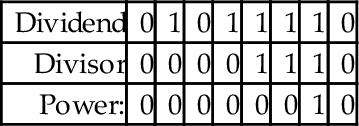

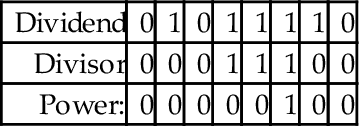

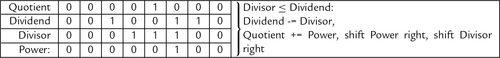

When the algorithm terminates, the quotient register contains the result of the division, and the modulus (remainder) is in the dividend register. Thus, one algorithm is used to compute both the quotient and the modulus at the same time. There are variations on this algorithm. For example, one variation is to shift a single bit left in a register, rather than incrementing a count. This variation has the same two phases as the previous algorithm, but counts in powers of two rather than by ones. The following sequence shows what occurs after each iteration of the first loop in the algorithm.

The divisor is greater than the dividend, so the algorithm proceeds to the second phase. In this phase, if the divisor is less than or equal to the dividend, then the power register is added to the quotient and the divisor is subtracted from the dividend. Then, the power and Divisor registers are shifted to the right. The process is repeated until the power register is zero. The following sequence shows what the registers will contain at the end of each iteration of the second loop.

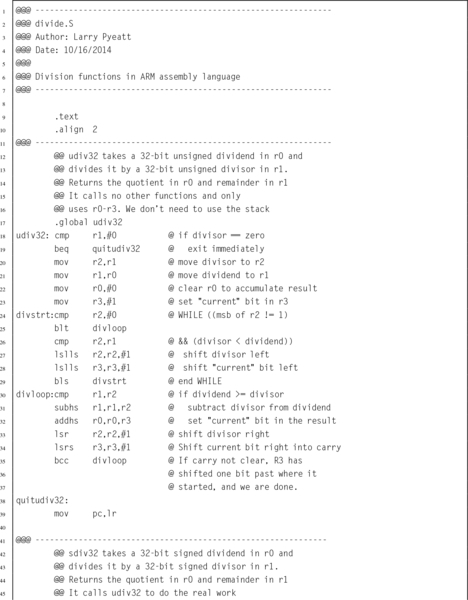

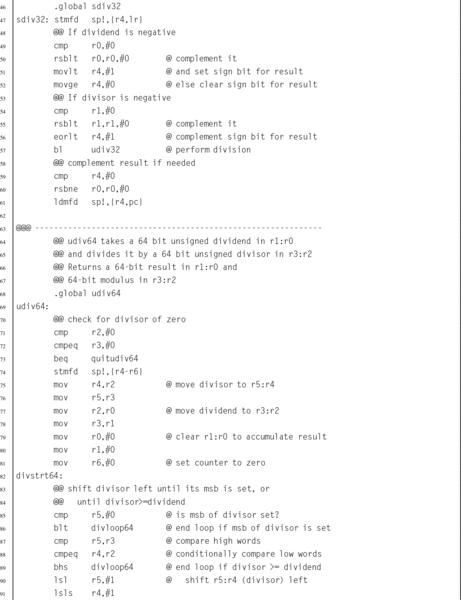

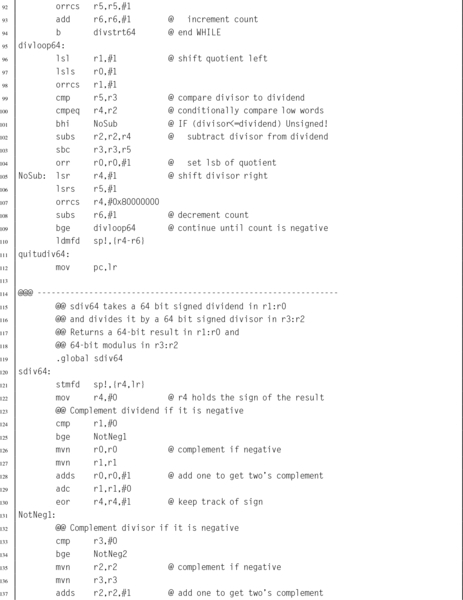

As with the previous version, when the algorithm terminates, the quotient register contains the result of the division, and the modulus (remainder) is in the dividend register. Listing 7.4 shows the ARM assembly code to implement this version of the division algorithm for 32-bit numbers, and the counting method for 64-bit numbers.

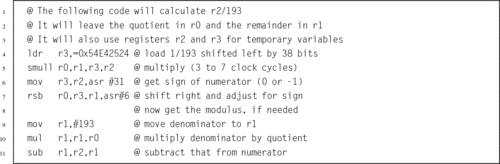

7.3.3 Division by a Constant

In general, division is slow. Newer ARM processors provide a hardware divide instruction which requires between two and twelve clock cycles to produce a result, depending on the size of the operands. Older processors must perform division using software, as previously described. In either case, division is by far the slowest of the basic mathematical operations. However, division by a constant c can be converted to a multiply by the reciprocal of c. It is obviously much more efficient to use a multiply instead of a divide wherever possible. Efficient division of a variable by a constant is achieved by applying the following equality:

The only difficulty is that we have to do it in binary, using only integers. If we modify the right-hand side by multiplying and dividing by some power of two (2n), we can rewrite Eq. (7.1) as follows:

Recall that, in binary, multiplying by 2n is the same as shifting left by n bits, while multiplying by 2−n is done by shifting right by n bits. Therefore, Eq. (7.2) is just Eq. (7.1) with two shift operations added. The two shift operations cancel each other out. Now, let

We can rewrite Eq. (7.2) as:

We now have a method for dividing by a constant c which involves multiplying by a different constant, m, and shifting the result. In order to achieve the best precision, we want to choose n such that m is as large as possible with the number of bits we have available.

Suppose we want efficient code to calculate x ÷ 23 using 8-bit signed integer multiplication. Our first task is to find  such that 011111112 ≥ m ≥ 010000002. In other words, we want to find the value of n where the most significant bit of m is zero, and the next most significant bit of m is one. If we choose n = 11, then

such that 011111112 ≥ m ≥ 010000002. In other words, we want to find the value of n where the most significant bit of m is zero, and the next most significant bit of m is one. If we choose n = 11, then

Rounding to the nearest integer gives m = 89. In 8 bits, m is 010110012 or 5916. We now have values for m and n, and therefore we can apply Eq. (7.4) to divide any number x by 23. The procedure is simple: calculate y = x × m, then shift y right by 11 bits.

However, there are two more considerations. First, when the divisor is positive, the result for some values of x may be incorrect due to rounding error. It is usually sufficient to increment the reciprocal value by one in order to avoid these errors. In the previous example, the number would be changed from 5916 to 5A16. When implementing this technique for finding the reciprocal, the programmer should always verify that the results are correct for all input values. The second consideration is when the dividend is negative. In that case it is necessary to subtract one from the final result.

For example, to calculate 10110 ÷ 2310 in binary, with eight bits of precision, we first perform the multiplication as follows:

Then shift the result right by 11 bits. 100011000111012 shifted right 1110 bits is: 1002 = 410. If the modulus is required, it can be calculated as 101 mod 23 = 101 − (4 × 23) = 9, which once again requires multiplication by a constant.

In the previous example the shift amount of 11 bits provided the best precision possible. But how was that number chosen? The shift amount, n, can be directly computed as

where p is the desired number of bits of precision. The value of m can then be computed as

For example, to divide by the constant 33, with 16 bits of precision, we compute n as

and then we compute m as

Therefore, multiplying a 16 bit number by 7C2016 and then shifting right 20 bits is equivalent to dividing by 33.

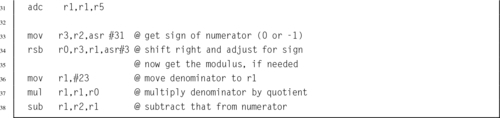

Example 7.6 shows how to calculate m and n for division by 193. On the ARM processor, division by a constant can be performed very efficiently. Listing 7.5 shows how division by 193 can be implemented using only a few lines of code. In the listing, the numbers are 32 bits in length, so the constant m is much larger than in the example that was multiplied by hand, but otherwise the method is the same.

On processors without the multiply instruction, we can use the technique of shifting and adding shown previously. If we wish to divide by 23 using 32 bits of precision, we compute the multiplier as

That is 010110010000101100100001011001012. Note that there are only 12 non-zero bits, and the pattern 1011001 appears three times in the 32-bit multiplier. The multiply can be implemented as 224(26x + 24x + 23x + 20x) + 213(26x + 24x + 23x + 20x) +22(26x + 24x + 23x + 20x) + 20x. So the following code sequence can be used on processors that do not have the multiply instruction:

7.3.4 Dividing Large Numbers

Section 7.2.5 showed how large numbers can be multiplied by breaking them into smaller numbers and using a series of multiplication operations. There is no similar method for synthesizing a large division operation with an arbitrary number of digits in the dividend and divisor. However, there is a method for dividing a large dividend by a divisor given that the division operation can operate on numbers with at least the same number of digits as in the divisor.

Suppose we wish to perform division of an arbitrarily large dividend by a one digit divisor using a basic division operation that can divide a two digit dividend by a one digit divisor. The operation can be performed in multiple steps as follows:

1. Divide the most significant digit of the dividend by the divisor. The result is the most significant digit of the quotient.

2. Prepend the remainder from the previous division step to the next digit of the dividend, forming a two-digit number, and divide that by the divisor. This produces the next digit of the result.

3. Repeat from step 2 until all digits of the dividend have been processed.

4. Take the final remainder as the modulus.

The following example shows how to divide 6189 by 7 using only 2-digits at a time:

This method can be applied in any base and with any number of digits. The only restriction is that the basic division operation must be capable of dividing a 2n digit number by an n digit number and producing a 2n digit quotient and an n digit remainder. for example, the div instruction available on Cortex M3 and newer processors is capable of dividing a 32-bit dividend by a 32-bit divisor, producing a 32-bit quotient. The remainder can be calculated by multiplying the quotient by the divisor and subtracting the product from the dividend. Using this division operation it is possible to divide an arbitrarily large number by a 16-bit divisor.

We have seen that, given a divide operation capable of dividing an n digit number by an n digit number, it is possible to divide a dividend with any number of digits by a divisor with  digits. Unfortunately, there is no similar method to deal with an arbitrarily large divisor, or to divide an arbitrarily large dividend by a divisor with more than

digits. Unfortunately, there is no similar method to deal with an arbitrarily large divisor, or to divide an arbitrarily large dividend by a divisor with more than  digits. In those cases the division must be performed using a general division algorithm as shown previously.

digits. In those cases the division must be performed using a general division algorithm as shown previously.

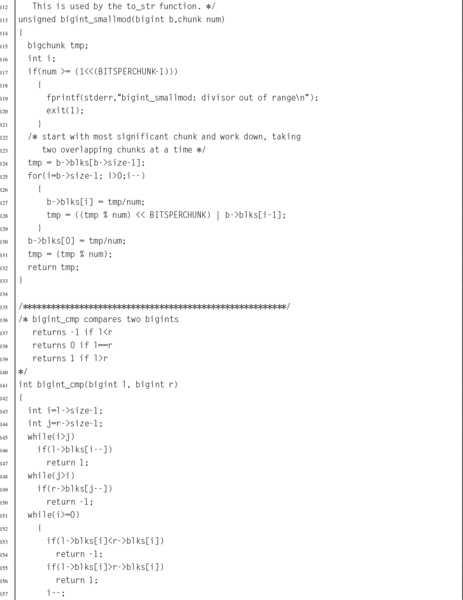

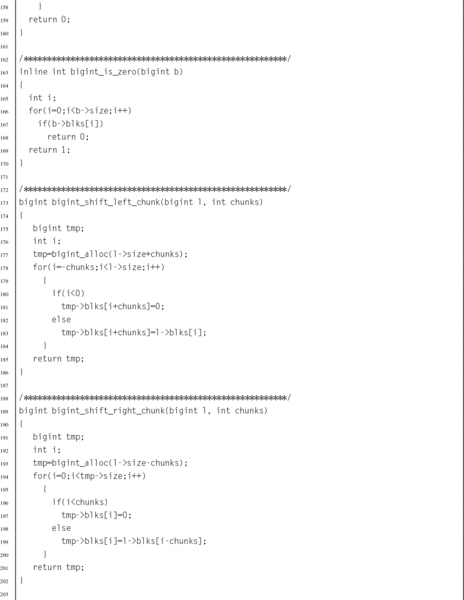

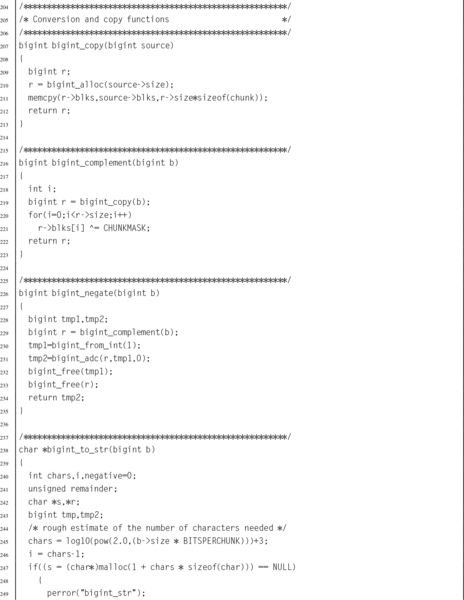

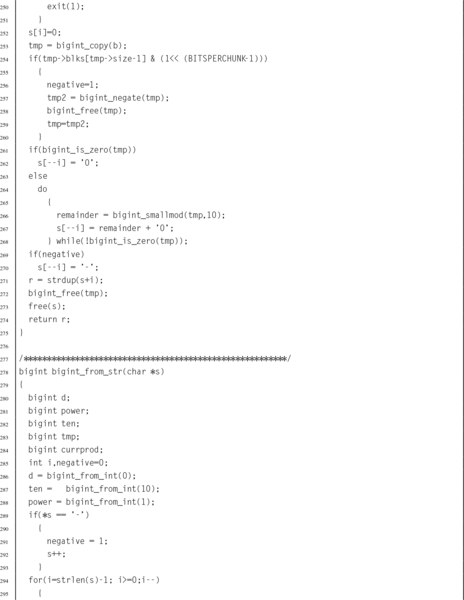

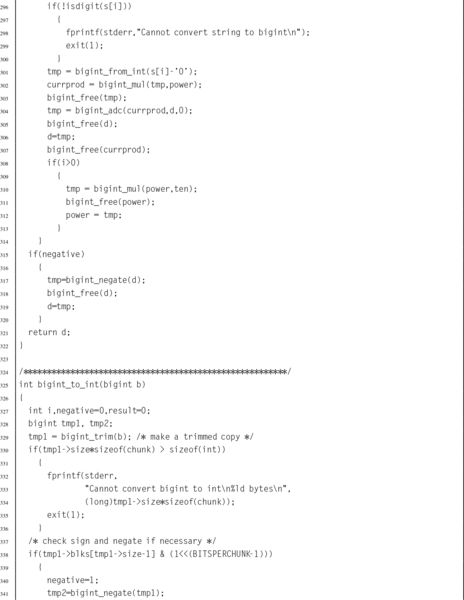

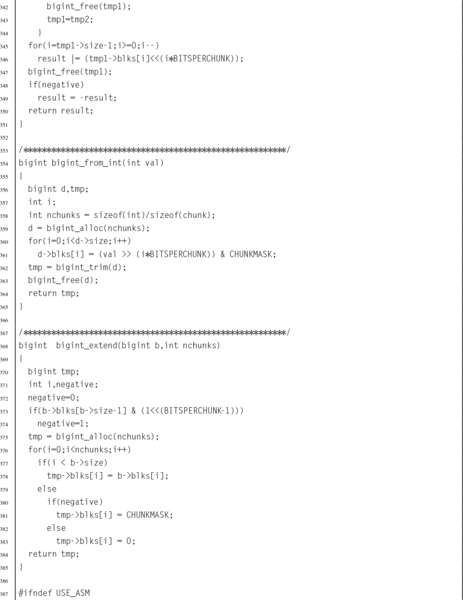

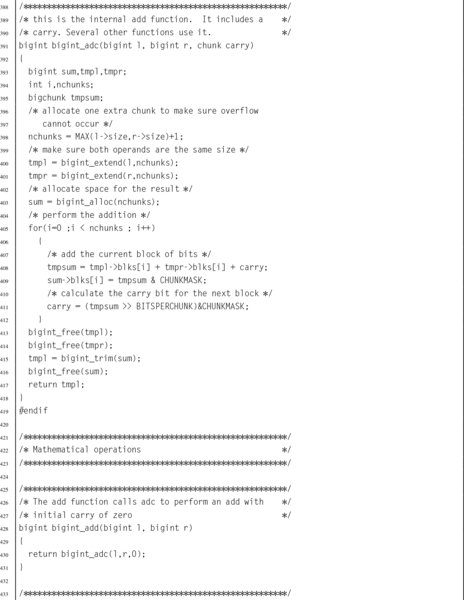

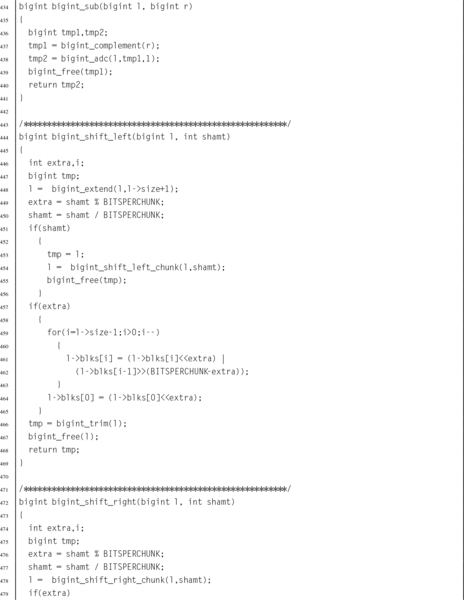

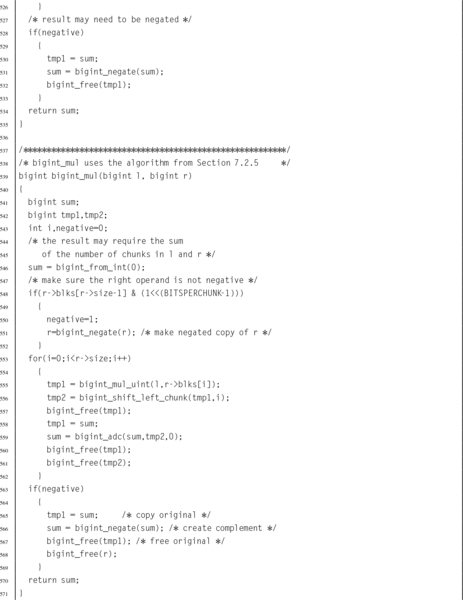

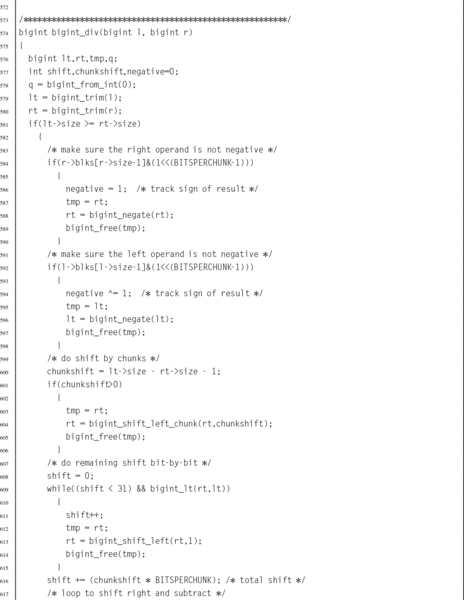

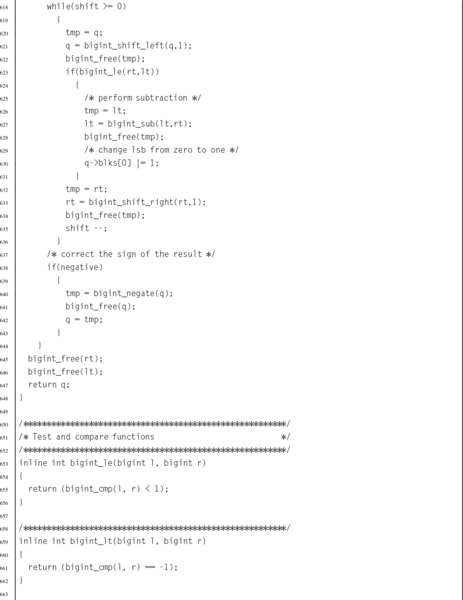

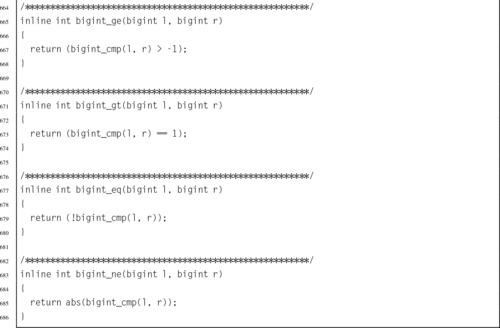

7.4 Big Integer ADT

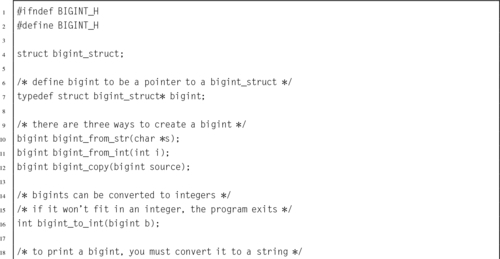

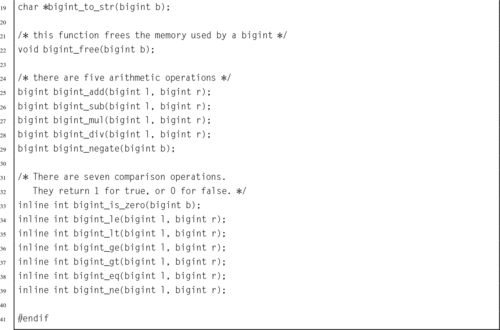

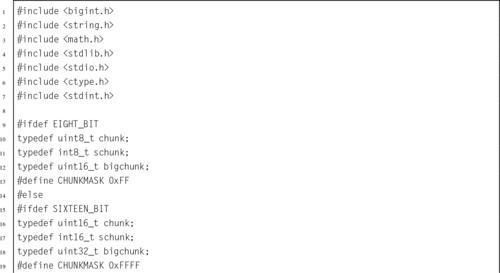

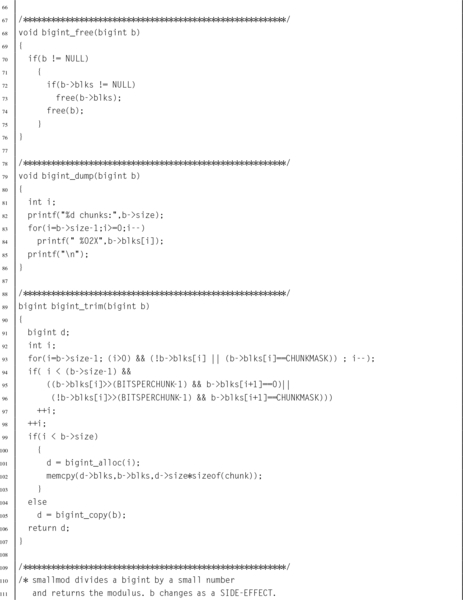

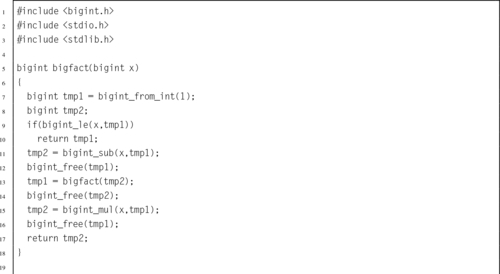

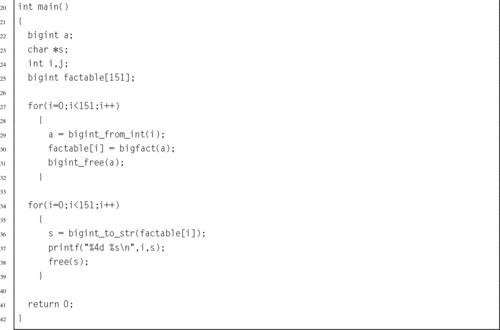

For some programming tasks, it may be helpful to deal with arbitrarily large integers. For example, the factorial function and Ackerman’s function grow very quickly and will overflow a 32-bit integer for small input values. In this section, we will outline an abstract data type which provides basic operations for arbitrarily large integer values. Listing 7.7 shows the C header for this ADT, and Listing 7.8 shows the C implementation. Listing 7.9 shows a small program that uses the bigint ADT to create a table of x! for all x between 0 and 100.

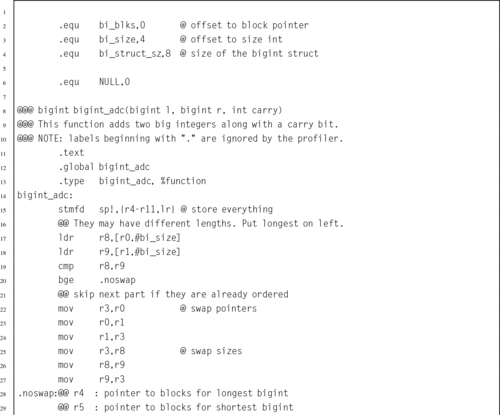

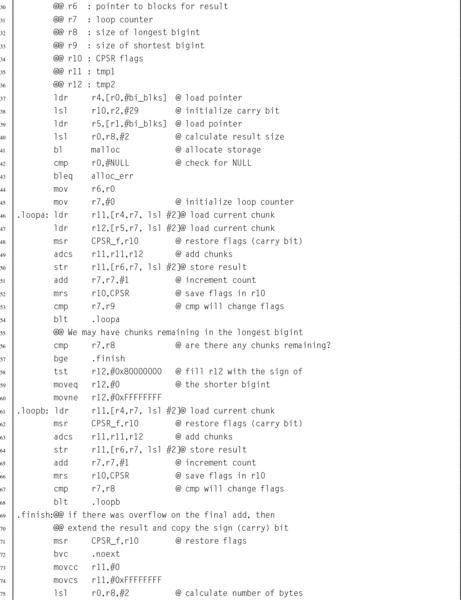

The implementation could be made more efficient by writing some of the functions in assembly language. One opportunity for improvement is in the add function, which must calculate the carry from one chunk of bits to the next. In assembly, the programmer has direct access to the carry bit, so carry propagation should be much faster.

When attempting to speed up a C program by converting selected parts of it to assembly language, it is important to first determine where the most significant gains can be made. A profiler, such as gprof, can be used to help identify the sections of code that will matter most. It is also important to make sure that the result is not just highly optimized C code. If the code cannot benefit from some features offered by assembly, then it may not be worth the effort of re-writing in assembly. The code should be re-written from a pure assembly language viewpoint.

It is also important to avoid premature assembly programming. Make sure that the C algorithms and data structures are efficient before moving to assembly. if a better algorithm can give better performance, then assembly may not be required at all. Once the assembly is written, it is more difficult to make major changes to the data structures and algorithms. Assembly language optimization is the final step in optimization, not the first one.

Well-written C code is modularized, with many small functions. This helps readability, promotes code reuse, and may allow the compiler to achieve better optimization. However, each function call has some associated overhead. If optimal performance is the goal, then calling many small functions should be avoided. For instance, if the piece of code to be optimized is in a loop body, then it may be best to write the entire loop in assembly, rather than writing a function and calling it each time through the loop. Writing in assembly is not a guarantee of performance. Spaghetti code is slow. Load/store instructions are slow. Multiplication and division are slow. The secret to good performance is avoiding things that are slow. Good optimization requires rethinking the code to take advantage of assembly language.

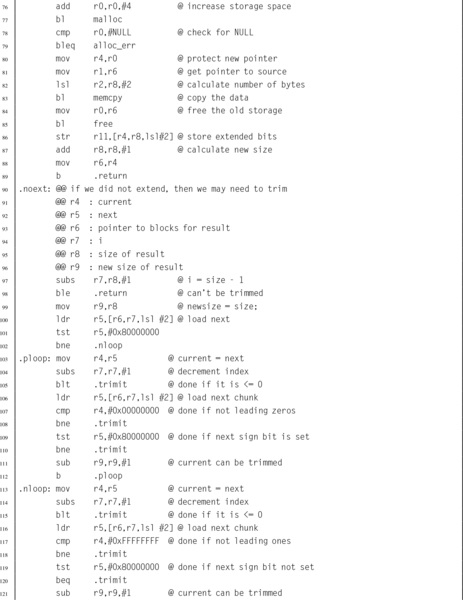

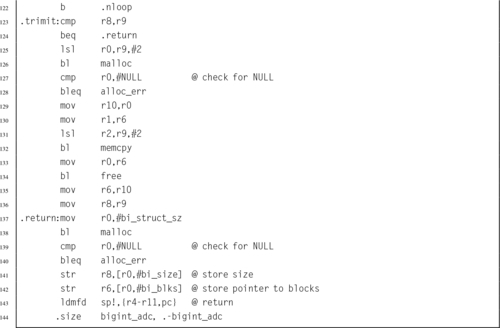

The bigint_adc function was re-written in assembly, as shown in Listing 7.10. This function is used internally by several other functions in the bigint ADT to perform addition and subtraction. The profiler indicated that it is used more than any other function. If assembly language can make this function run faster, then it should have a profound effect on the program.

The bigfact main function was executed 50 times on a Raspberry Pi, using the C version of bigint_adc and then with the assembly version. The total time required using the C version was 27.65 seconds, and the program spent 54.0% of its time (14.931 seconds) in the bigint_adc function. The assembly version ran in 15.07 seconds, and the program spent 15.3% of its time (2.306 seconds) in the bigint_adc function. Therefore the assembly version of the function achieved a speedup of 6.47 over the C implementation. Overall, the program achieved a speedup of 1.83 by writing one function in assembly.

Running gprof on the improved program reveals that most of the time is now spent in the bigint_mul function (63.2%) and two functions that it calls: bigint_mul_uint (39.1%) and bigint_shift_left_chunk (21.6%). It seems clear that optimizing those two functions would further improve performance.

7.5 Chapter Summary

Complement mathematics provides a method for performing all basic operations using only the complement, add, and shift operations. Addition and subtraction are fast, but multiplication and division are relatively slow. In particular, division should be avoided whenever possible. The exception to this rule is division by a power of the radix, which can be implemented as a shift. Good assembly programmers replace division by a constant c with multiplication by the reciprocal of c. They also replace the multiply instruction with a series of shifts and add or subtract operations when it makes sense to do so. These optimizations can make a big difference in performance.

Writing sections of a program in assembly can result in better performance, but it is not guaranteed. The chance of achieving significant performance improvement is increased if the following rules are used:

1. Only optimize the parts that really matter.

2. Design data structures with assembly in mind.

3. Use efficient algorithms and data structures.

4. Write the assembly code last.

5. Ignore the C version and write good, clean, assembly.

6. Reduce function calls wherever it makes sense.

7. Avoid unnecessary memory accesses.

8. Write good code. The compiler will beat poor assembly every time, but good assembly will beat the compiler every time.

Understanding the basic mathematical operations can enable the assembly programmer to work with integers of any arbitrary size with efficiency that cannot be matched by a C compiler. However, it is best to focus the assembly programming on areas where the greatest gains can be made.

Exercises

7.1 Multiply − 90 by 105 using signed 8-bit binary multiplication to form a signed 16-bit result. Show all of your work.

7.2 Multiply 166 by 105 using unsigned 8-bit binary multiplication to form an unsigned 16-bit result. Show all of your work.

7.3 Write a section of ARM assembly code to multiply the value in r1 by 1310 using only shift and add operations.

7.4 The following code will multiply the value in r0 by a constant C. What is C?

7.5 Show the optimally efficient instruction(s) necessary to multiply a number in register r0 by the constant 6710.

7.6 Show how to divide 7810 by 610 using binary long division.

7.7 Demonstrate the division algorithm using a sequence of tables as shown in Section 7.3.2 to divide 15510 by 1110.

7.8 When dividing by a constant value, why is it desirable to have m as large as possible?

7.9 Modify your program from Exercise 5.13 in Chapter 5 to produce a 64-bit result, rather than a 32-bit result.

7.10 Modify your program from Exercise 5.13 in Chapter 5 to produce a 128-bit result, rather than a 32-bit result. How would you do this in C?

7.11 Write the bigint_shift_left_chunk function from Listing 7.8 in ARM assembly, and measure the performance improvement.

7.12 Write the bigint_mul_uint function in ARM assembly, and measure the performance improvement.

7.13 Write the bigint_mul function in ARM assembly, and measure the performance improvement.