GNU Assembly Syntax

Abstract

This chapter begins with a high-level description of assembly language and the assembler. It then explains the five elements of assembly language syntax, and gives some examples. It then goes in to more depth about how the assembler converts assembly language files into object files, which are then linked with other object files to create an executable file. Then it explains the most commonly used directives for the GNU assembler, and gives some examples to help relate the assembly code to equivalent C code.

Keywords

Compiler; Assembler; Linker; Labels; Comments; Directives; Instructions; Sections; Symbols

All modern computers consist of three main components: the central processing unit (CPU), memory, and devices. It can be argued that the major factor that distinguishes one computer from another is the CPU architecture. The architecture determines the set of instructions that can be performed by the CPU. The human-readable language which is closest to the CPU architecture is assembly language.

When a new processor architecture is developed, its creators also define an assembly language for the new architecture. In most cases, a precise assembly language syntax is defined and an assembler is created by the processor developers. Because of this, there is no single syntax for assembly language, although most assembly languages are similar in many ways and have certain elements in common.

The GNU assembler (GAS) is a highly portable re-configurable assembler. GAS uses a simple, general syntax that works for a wide variety of architectures. Although the syntax used by GAS for the ARM processor is slightly different from the syntax defined by the developers of the ARM processor, it provides the same capabilities.

2.1 Structure of an Assembly Program

An assembly program consists of four basic elements: assembler directives, labels, assembly instructions, and comments. Assembler directives allow the programmer to reserve memory for the storage of variables, control which program section is being used, define macros, include other files, and perform other operations that control the conversion of assembly instructions into machine code. The assembly instructions are given as mnemonics, or short character strings that are easier for human brains to remember than sequences of binary, octal, or hexadecimal digits. Each assembly instruction may have an optional label, and most assembly instructions require the programmer to specify one or more operands.

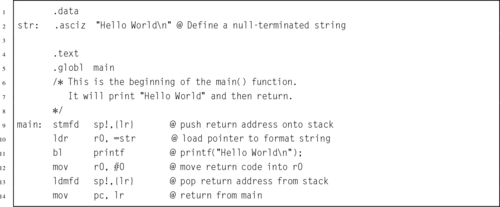

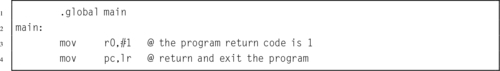

Most assembly language programs are written in lines of 80 characters organized into four columns. The first column is for optional labels. The second column is for assembly instructions or assembler directives. The third column is for specifying operands, and the fourth column is for comments. Traditionally, the first two columns are 8 characters wide, the third column is 16 characters wide, and the last column is 48 characters wide. However, most modern assemblers (including GAS) do not require a fixed column widths. Listing 2.1 shows a basic “Hello World” program written in GNU ARM Assembly to run under Linux. For comparison, Listing 2.2 shows an equivalent program written in C. The assembly language version of the program is significantly longer than the C version, and will only work on an ARM processor. The C version is at a higher level of abstraction, and can be compiled to run on any system that has a C compiler. Thus, C is referred to as a high-level language, and assembly is a low-level language.

2.1.1 Labels

Most modern assemblers are called two-pass assemblers because they read the input file twice. On the first pass, the assembler keeps track of the location of each piece of data and each instruction, and assigns an address or numerical value to each label and symbol in the input file. The main goal of the first pass is to build a symbol table, which maps each label or symbol to a numerical value.

On the second pass, the assembler converts the assembly instructions and data declarations into binary, using the symbol table to supply numerical values whenever they are needed. In Listing 2.1, there are two labels: main and str. During assembly, those labels are assigned the value of the address counter at the point where they appear. Labels can be used anywhere in the program to refer to the address of data, functions, or blocks of code. In GNU assembly syntax, labels always end with a colon (:) character.

2.1.2 Comments

There are two basic comment styles: multi-line and single-line. Multi-line comments start with /* and everything is ignored until a matching sequence of */ is found. These comments are exactly the same as multi-line comments in C and C++. In ARM assembly, single line comments begin with an @ character, and all remaining characters on the line are ignored. Listing 2.1 shows both types of comment. In addition, if the name of the file ends in .S, then single line comments can begin with //. If the file name does not end with a capital .S, then the // syntax is not allowed.

2.1.3 Directives

Directives are used mainly to define symbols, allocate storage, and control the behavior of the assembler, allowing the programmer to control how the assembler does its job. The GNU assembler has many directives, but assembly programmers typically need to know only a few of them. All assembler directives begin with a period “.” which is followed by a sequence of letters, usually in lower case. Listing 2.1 uses the .data, .asciz, .text, and .globl directives. The most commonly used directives are discussed later in this chapter. There are many other directives available in the GNU Assembler which are not covered here. Complete documentation is available online as part of the GNU Binutils package.

2.1.4 Assembly Instructions

Assembly instructions are the program statements that will be executed on the CPU. Most instructions cause the CPU to perform one low-level operation, In most assembly languages, operations can be divided into a few major types. Some instructions move data from one location to another. Others perform addition, subtraction, and other computational operations. Another class of instructions is used to perform comparisons and control which part of the program is to be executed next. Chapters 3 and 4 explain most of the assembly instructions that are available on the ARM processor.

2.2 What the Assembler Does

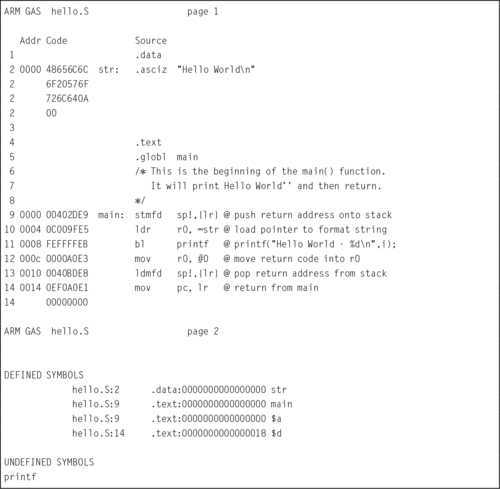

Listing 2.3 shows how the GNU assembler will assemble the “Hello World” program from Listing 2.1. The assembler converts the string on input line 2 into the binary representation of the string. The results are shown in hexadecimal in the Code column of the listing. The first byte of the string is stored at address zero in the .data section of the program, as shown by the 0000 in the Addr column on line 2.

On line 4, the assembler switches to the .text section of the program and begins converting instructions into binary. The first instruction, on line 9, is converted into its 4-byte machine code, 00402DE916, and stored at location 0000 in the .text section of the program, as shown in the Code and Addr columns on line 6.

Next, the assembler converts the ldr instruction on line 10 into the four-byte machine instruction 0C009FE516 and stores it at address 0004. It repeats this process with each remaining instruction until the end of the program. The assembler writes the resulting data into a specially formatted file, called an object file. Note that the assembler was unable to locate the printf function. The linker will take care of that. The object file created by the assembler, hello.o, contains the data in the Code column of Listing 2.3, along with information to help the linker to link (or “patch”) the instruction on line 11 so that printf is called correctly.

After creating the object file, the next step in creating an executable program would be to invoke the linker and request that it link hello.o with the C standard library. The linker will generate the final executable file, containing the code assembled from hello.S, along with the printf function and other start-up code from the C standard library. The GNU C compiler is capable of automatically invoking the assembler for files that end in .s or .S, and can also be used to invoke the linker. For example, if Listing 2.1 is stored in a file named hello.S in the current directory, then the command

will run the GNU C compiler, telling it to create an executable program file named hello, and to use hello.S as the source file for the program. The C compiler will notice the .S extension, and invoke the assembler to create an object file which is stored in a temporary file, possibly named hello.o. Then the C compiler will invoke the linker to link hello.o with the C standard library, which provides the printf function and some start-up code which calls the main function. The linker will create an executable file named hello. When the linker has finished, the C compiler will remove the temporary object file.

2.3 GNU Assembly Directives

Each processor architecture has its own assembly language, created by the designers of the architecture. Although there are many similarities between assembly languages, the designers may choose different names for various directives. The GNU assembler supports a relatively large set of directives, some of which have more than one name. This is because it is designed to handle assembling code for many different processors without drastically changing the assembly language designed by the processor manufacturers. We will now cover some of the most commonly used directives for the GNU assembler.

2.3.1 Selecting the Current Section

The instructions and data that make up a program are stored in different sections of the program file. There are several standard sections that the programmer can choose to put code and data in. Sections can also be further divided into numbered subsections. Each section has its own address counter, which is used to keep track of the location of bytes within that section. When a label is encountered, it is assigned the value of the current address counter for the currently active section.

Selecting a section and subsection is done by using the appropriate assembly directive. Once a section has been selected, all of the instructions and/or data will go into that section until another section is selected. The most important directives for selecting a section are:

Instructs the assembler to append the following instructions or data to the data subsection numbered subsection. If the subsection number is omitted, it defaults to zero. This section is normally used for global variables and constants which have labels.

Tells the assembler to append the following statements to the end of the text subsection numbered subsection. If the subsection number is omitted, subsection number zero is used. This section is normally used for executable instructions, but may also contain constant data.

The bss (short for Block Started by Symbol) section is used for defining data storage areas that should be initialized to zero at the beginning of program execution. The .bss directive tells the assembler to append the following statements to the end of the bss subsection numbered subsection. If the subsection number is omitted, subsection number zero is used. This section is normally used for global variables which need to be initialized to zero. Regardless of what is placed into the section at compile-time, all bytes will be set to zero when the program begins executing. This section does not actually consume any space in the object or executable file. It is really just a request for the loader to reserve some space when the program is loaded into memory.

In addition to the three common sections, the programmer can create other sections using this directive. However in order for custom sections to be linked into a program, the linker must be made aware of them. Controlling the linker is covered in Section 14.4.3.

2.3.2 Allocating Space for Variables and Constants

There are several directives that allow the programmer to allocate and initialize static storage space for variables and constants. The assembler supports bytes, integer types, floating point types, and strings. These directives are used to allocate a fixed amount of space in memory and optionally initialize the memory. Some of these directives allow the memory to be initialized using an expression. An expression can be a simple integer, or a C-style expression. The directives for allocating storage are as follows:

.byte expects zero or more expressions, separated by commas. Each expression is assembled into the next byte. If no expressions are given, then the address counter is not advanced and no bytes are reserved.

.hword expressions .short expressions

For the ARM processor, these two directives do exactly the same thing. They expect zero or more expressions, separated by commas, and emit a 16-bit number for each expression. If no expressions are given, then the address counter is not advanced and no bytes are reserved.

.word expressions .long expressions

For the ARM processor, these two directives do exactly the same thing. They expect zero or more expressions, separated by commas. They will emit four bytes for each expression given. If no expressions are given, then the address counter is not advanced and no bytes are reserved.

The .ascii directive expects zero or more string literals, each enclosed in quotation marks and separated by commas. It assembles each string (with no trailing ASCII NULL character) into consecutive addresses.

.asciz ” string ” .string ” string ”

The .asciz directive is similar to the .ascii directive, but each string is followed by an ASCII NULL character (zero). The “z” in .asciz stands for zero. .string is just another name for .asciz.

.float flonums .single flonums

This directive assembles zero or more floating point numbers, separated by commas. On the ARM, they are 4-byte IEEE standard single precision numbers. .float and .single are synonymous.

The .double directive expects zero or more floating point numbers, separated by commas. On the ARM, they are stored as 8-byte IEEE standard double precision numbers.

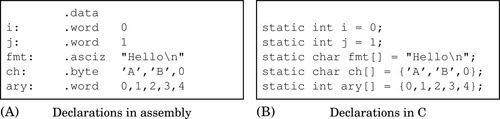

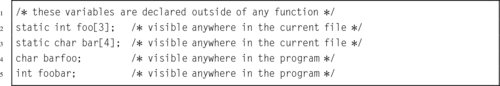

Fig. 2.1A shows how these directives are used to declare variables and constants. Fig. 2.1B shows the equivalent statements for creating global variables in C or C++. Note that in both cases, the variables created will be visible anywhere within the file that they are declared, but not visible in other files which are linked into the program.

In C, the declaration of an array can be performed by leaving out the number of elements and specifying an initializer, as shown in the last three lines of Fig. 2.1B. In assembly, the equivalent is accomplished by providing a label, a type, and a list of values, as shown in the last three lines of Fig. 2.1A. The syntax is different, but the result is precisely the same.

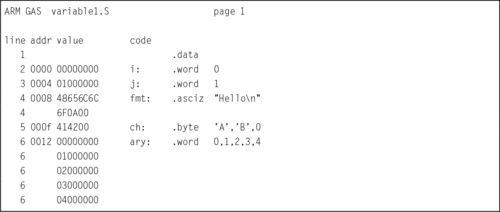

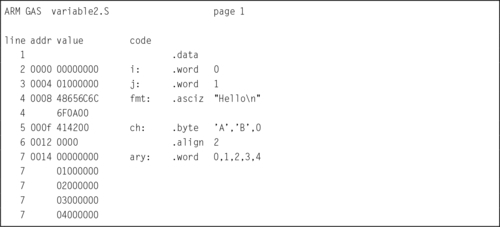

Listing 2.4 shows how the assembler assigns addresses to these labels. The second column of the listing shows the address (in hexadecimal) that is assigned to each label. The variable i is assigned the first address. Since it is a word variable, the address counter is incremented by four bytes and the next address is assigned to the variable j. The address counter is incremented again, and fmt is assigned the address 0008. The fmt variable consumes seven bytes, so the ch variable gets address 000f. Finally, the array of words named ary begins at address 0012. Note that 1216 = 1810 is not evenly divisible by four, which means that the word variables in ary are not aligned on word boundaries.

2.3.3 Filling and Aligning

On the ARM CPU, data can be moved to and from memory one byte at a time, two bytes at a time (half-word), or four bytes at a time (word). Moving a word between the CPU and memory takes significantly more time if the address of the word is not aligned on a four-byte boundary (one where the least significant two bits are zero). Similarly, moving a half-word between the CPU and memory takes significantly more time if the address of the half-word is not aligned on a two-byte boundary (one where the least significant bit is zero). Therefore, when declaring storage, it is important that words and half-words are stored on appropriate boundaries. The following directives allow the programmer to insert as much space as necessary to align the next item on any boundary desired.

.align abs-expr, abs-expr, abs-expr

Pad the location counter (in the current subsection) to a particular storage boundary. For the ARM processor, the first expression specifies the number of low-order zero bits the location counter must have after advancement. The second expression gives the fill value to be stored in the padding bytes. It (and the comma) may be omitted. If it is omitted, then the fill value is assumed to be zero. The third expression is also optional. If it is present, it is the maximum number of bytes that should be skipped by this alignment directive.

.balign [lw] abs-expr, abs-expr, abs-expr

These directives adjust the location counter to a particular storage boundary. The first expression is the byte-multiple for the alignment request. For example, .balign 16 will insert fill bytes until the location counter is an even multiple of 16. If the location counter is already a multiple of 16, then no fill bytes will be created. The second expression gives the fill value to be stored in the fill bytes. It (and the comma) may be omitted. If it is omitted, then the fill value is assumed to be zero. The third expression is also optional. If it is present, it is the maximum number of bytes that should be skipped by this alignment directive.

The .balignw and .balignl directives are variants of the .balign directive. The .balignw directive treats the fill pattern as a 2-byte word value, and .balignl treats the fill pattern as a 4-byte long word value. For example, “.balignw 4,0x368d” will align to a multiple of four bytes. If it skips two bytes, they will be filled in with the value 0x368d (the exact placement of the bytes depends upon the endianness of the processor).

.skip size, fill .space size, fill

Sometimes it is desirable to allocate a large area of memory and initialize it all to the same value. This can be accomplished by using these directives. These directives emit size bytes, each of value fill. Both size and fill are absolute expressions. If the comma and fill are omitted, fill is assumed to be zero. For the ARM processor, the .space and .skip directives are equivalent. This directive is very useful for declaring large arrays in the .bss section.

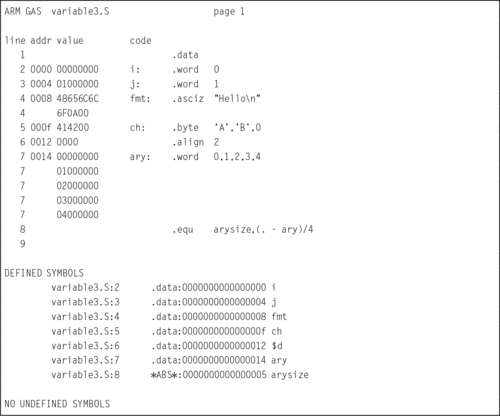

Listing 2.5 shows how the code in Listing 2.4 can be improved by adding an alignment directive at line 6. The directive causes the assembler to emit two zero bytes between the end of the ch variable and the beginning of the ary variable. These extra “padding” bytes cause the following word data to be word aligned, thereby improving performance when the word data is accessed. It is a good practice to always put an alignment directive after declaring character or half-word data.

2.3.4 Setting and Manipulating Symbols

The assembler provides support for setting and manipulating symbols that can then be used in other places within the program. The labels that can be assigned to assembly statements and directives are one type of symbol. The programmer can also declare other symbols and use them throughout the program. Such symbols may not have an actual storage location in memory, but they are included in the assembler’s symbol table, and can be used anywhere that their value is required. The most common use for defined symbols is to allow numerical constants to be declared in one place and easily changed. The .equ directive allows the programmer to use a label instead of a number throughout the program. This contributes to readability, and has the benefit that the constant value can then be easily changed every place that it is used, just by changing the definition of the symbol. The most important directives related to symbols are:

.equ symbol, expression .set symbol, expression

This directive sets the value of symbol to expression. It is similar to the C language #define directive.

The .equiv directive is like .equ and .set, except that the assembler will signal an error if the symbol is already defined.

.global symbol .globl symbol

This directive makes the symbol visible to the linker. If symbol is defined within a file, and this directive is used to make it global, then it will be available to any file that is linked with the one containing the symbol. Without this directive, symbols are visible only within the file where they are defined.

This directive declares symbol to be a common symbol, meaning that if it is defined in more than one file, then all instances should be merged into a single symbol. If the symbol is not defined anywhere, then the linker will allocate length bytes of uninitialized memory. If there are multiple definitions for symbol, and they have different sizes, the linker will merge them into a single instance using the largest size defined.

Listing 2.6 shows how the .equ directive can be used to create a symbol holding the number of elements in an array. The symbol arysize is defined as the value of the current address counter (denoted by the .) minus the value of the ary symbol, divided by four (each word in the array is four bytes). The listing shows all of the symbols defined in this program segment. Note that the four variables are shown to be in the data segment, and the arysize symbol is marked as an “absolute” symbol, which simply means that it is a number and not an address. The programmer can now use the symbol arysize to control looping when accessing the array data. If the size of the array is changed by adding or removing constant values, the value of arysize will change automatically, and the programmer will not have to search through the code to change the original value, 5, to some other value in every place it is used.

2.3.5 Conditional Assembly

Sometimes it is desirable to skip assembly of portions of a file. The assembler provides some directives to allow conditional assembly. One use for these directives is to optionally assemble code to aid in debugging.

.if marks the beginning of a section of code which is only considered part of the source program being assembled if the argument (which must be an absolute expression) is non-zero. The end of the conditional section of code must be marked by the .endif directive. Optionally, code may be included for the alternative condition by using the .else directive.

Assembles the following section of code if the specified symbol has been defined.

Assembles the following section of code if the specified symbol has not been defined.

Assembles the following section of code only if the condition for the preceding .if or.ifdef was false.

Marks the end of a block of code that is only assembled conditionally.

2.3.6 Including Other Source Files

This directive provides a way to include supporting files at specified points in the source program. The code from the included file is assembled as if it followed the point of the .include directive. When the end of the included file is reached, assembly of the original file continues. The search paths used can be controlled with the ‘-I’ command line parameter. Quotation marks are required around file. This assembler directive is similar to including header files in C and C++ using the #include compiler directive.

2.3.7 Macros

The directives .macro and .endm allow the programmer to define macros that the assembler expands to generate assembly code. The GNU assembler supports simple macros. Some other assemblers have much more powerful macro capabilities.

.macro macname .macro macname macargs …

Begin the definition of a macro called macname. If the macro definition requires arguments, their names are specified after the macro name, separated by commas or spaces. The programmer can supply a default value for any macro argument by following the name with ‘=deflt’.

The following begins the definition of a macro called reserve_str, with two arguments. The first argument has a default value, but the second does not:

When a macro is called, the argument values can be specified either by position, or by keyword. For example, reserve_str 9,17 is equivalent to reserve_str p2=17,p1=9. After the definition is complete, the macro can be called either as

(with \p1 evaluating to x and \p2 evaluating to y), or as

(with \p1 evaluating as the default, in this case 0, and \p2 evaluating to y). Other examples of valid .macro statements are:

End the current macro definition.

Exit early from the current macro definition. This is usually used only within a .if or .ifdef directive.

This is a pseudo-variable used by the assembler to maintain a count of how many macros it has executed. That number can be accessed with ‘\@’, but only within a macro definition.

Macro example

The following definition specifies a macro SHIFT that will emit the instruction to shift a given register left by a specified number of bits. If the number of bits specified is negative, then it will emit the instruction to perform a right shift instead of a left shift.

After that definition, the following code:

will generate these instructions:

The meaning of these instructions will be covered in Chapters 3 and 4.

Recursive macro example

The following definition specifies a macro enum that puts a sequence of numbers into memory by using a recursive macro call to itself:

With that definition, ‘enum 0,5’ is equivalent to this assembly input:

2.4 Chapter Summary

There are four elements to assembly syntax: labels, directives, instructions, and comments. Directives are used mainly to define symbols, allocate storage, and control the behavior of the assembler. The most common assembler directives were introduced in this chapter, but there are many other directives available in the GNU assembler. Complete documentation is available online as part of the GNU Binutils package.

Directives are used to declare statically allocated storage, which is equivalent to declaring global static variables in C. In assembly, labels and other symbols are visible only within the file that they are declared, unless they are explicitly made visible to other files with the .global directive. In C, variables that are declared outside of any function are visible to all files in the program, unless the static keyword is used to make them visible only within the file where they are declared. Thus, both C and assembly support file and global scope for static variables, but with the opposite defaults and different syntax.

Directives can also be used to declare macros. Macros are expanded by the assembler and may generate multiple statements. Careful use of macros can automate some simple tasks, allowing several lines of assembly code to be replaced with a single macro invocation.

Exercises

2.1 What is the difference between

(a) the .data section and .bss section?

(b) the .ascii and .asciz directives?

(c) the .word and the .long directives?

2.2 What is the purpose of the .align assembler directive? What does “.align 2” do in GNU ARM assembly?

2.3 Assembly language has four main elements. What are they?

2.4 Using the directives presented in this chapter, show three different ways to create a null-terminated string containing the phrase “segmentation fault”.

2.5 What is the total memory, in bytes, allocated for the following variables?

2.6 Identify the directive(s), label(s), comment(s), and instruction(s) in the following code:

2.7 Write assembly code to declare variables equivalent to the following C code:

2.8 Show how to store the following text as a single string in assembly language, while making it readable and keeping each line shorter than 80 characters:

The three goals of the mission are:

1) Keep each line of code under 80 characters,

2) Write readable comments,

3) Learn a valuable skill for readability.

2.9 Insert the minimum number of .align directives necessary in the following code so that all word variables are aligned on word boundaries and all halfword variables are aligned on halfword boundaries, while minimizing the amount of wasted space.

2.10 Re-order the directives in the previous problem so that no .align directives are necessary to ensure proper alignment. How many bytes of storage were wasted by the original ordering of directives, compared to the new one?

2.11 What are the most important directives for selecting a section?

2.12 Why are .ascii and .asciz directives usually followed by an .align directive, but .word directives are not?

2.13 Using the “Hello World” program shown in Listing 2.1 as a template, write a program that will print your name.

2.14 Listing 2.3 shows that the assembler will assign the location 0000000016 to the main symbol and also to the str symbol. Why does this not cause problems?