First Edition

Part I: Assembly as a Language

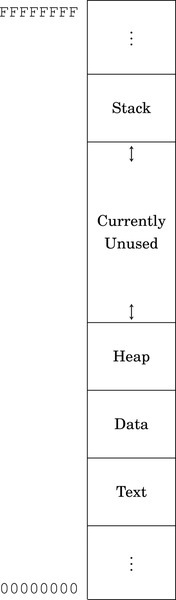

1.4 Memory Layout of an Executing Program

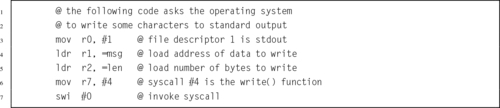

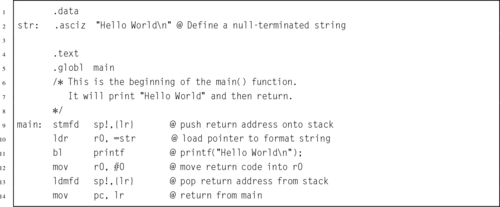

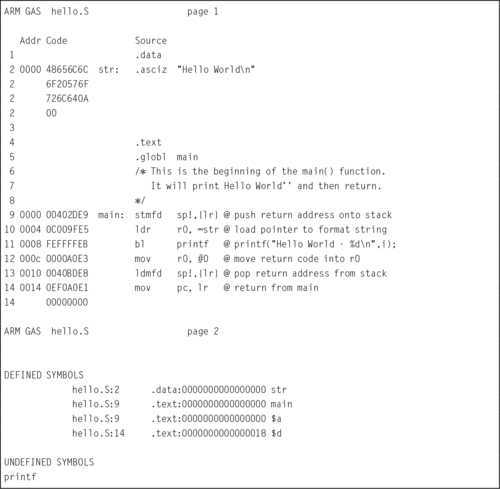

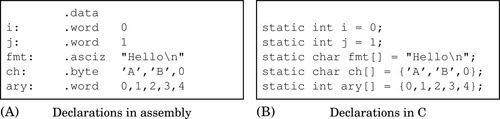

Chapter 2: GNU Assembly Syntax

2.1 Structure of an Assembly Program

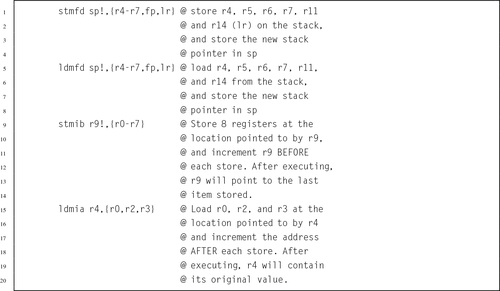

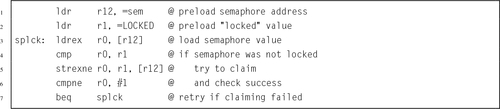

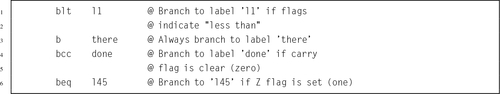

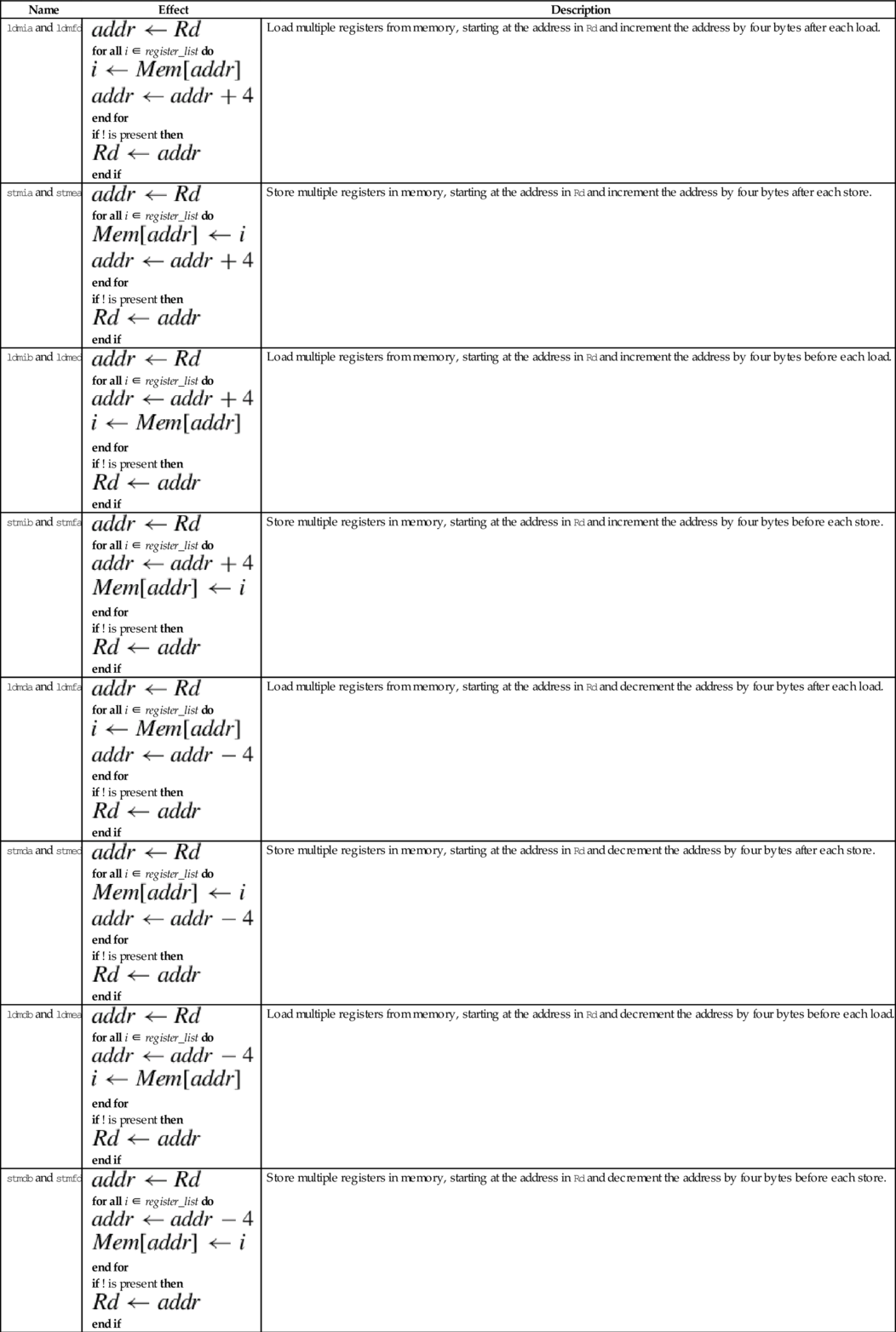

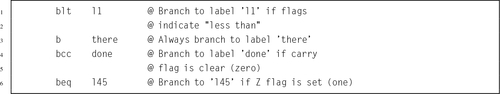

Chapter 3: Load/Store and Branch Instructions

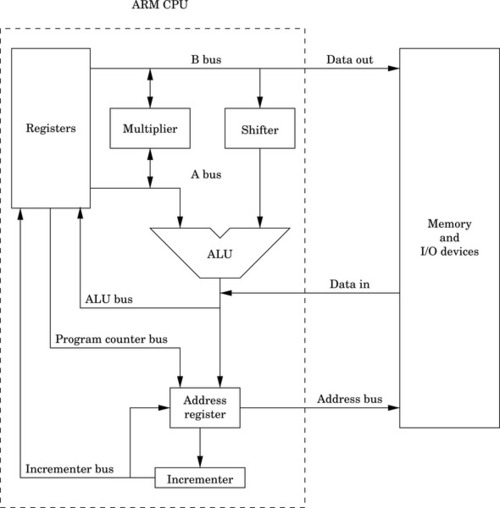

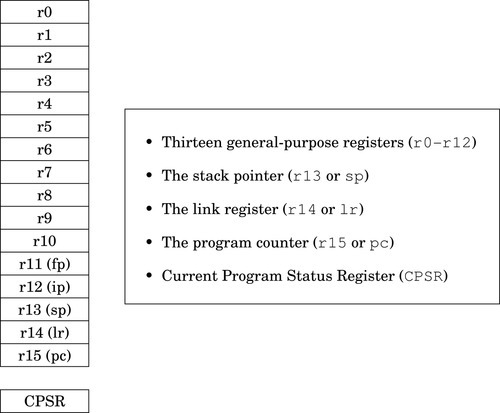

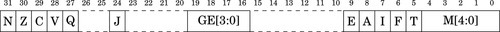

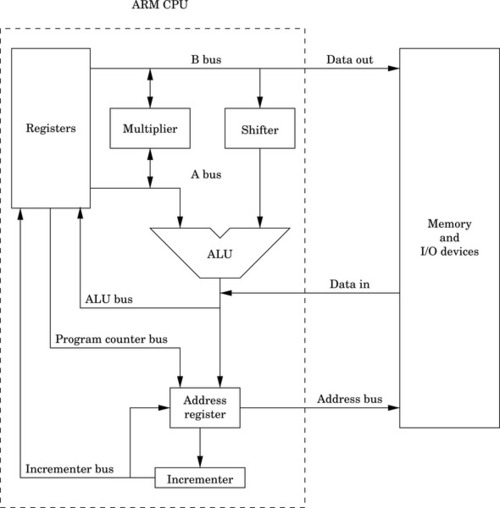

3.1 CPU Components and Data Paths

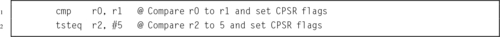

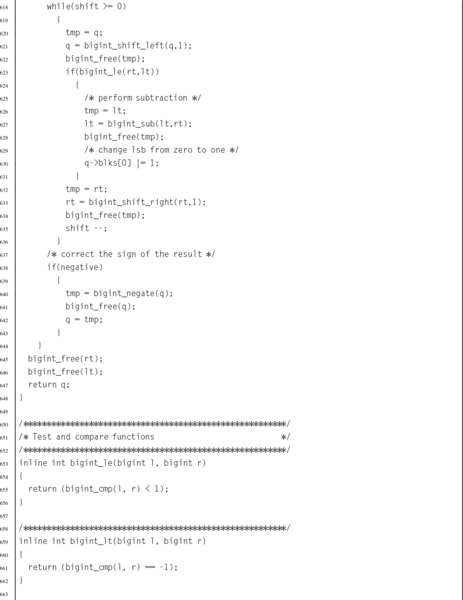

Chapter 4: Data Processing and Other Instructions

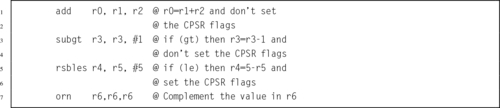

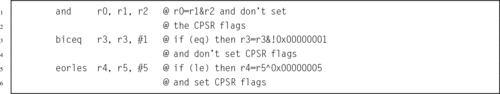

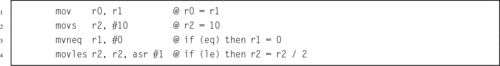

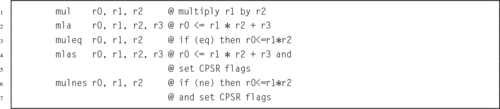

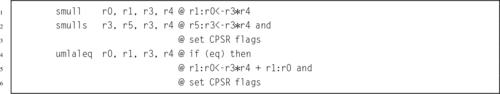

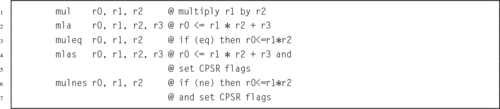

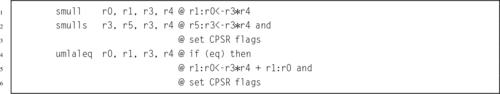

4.1 Data Processing Instructions

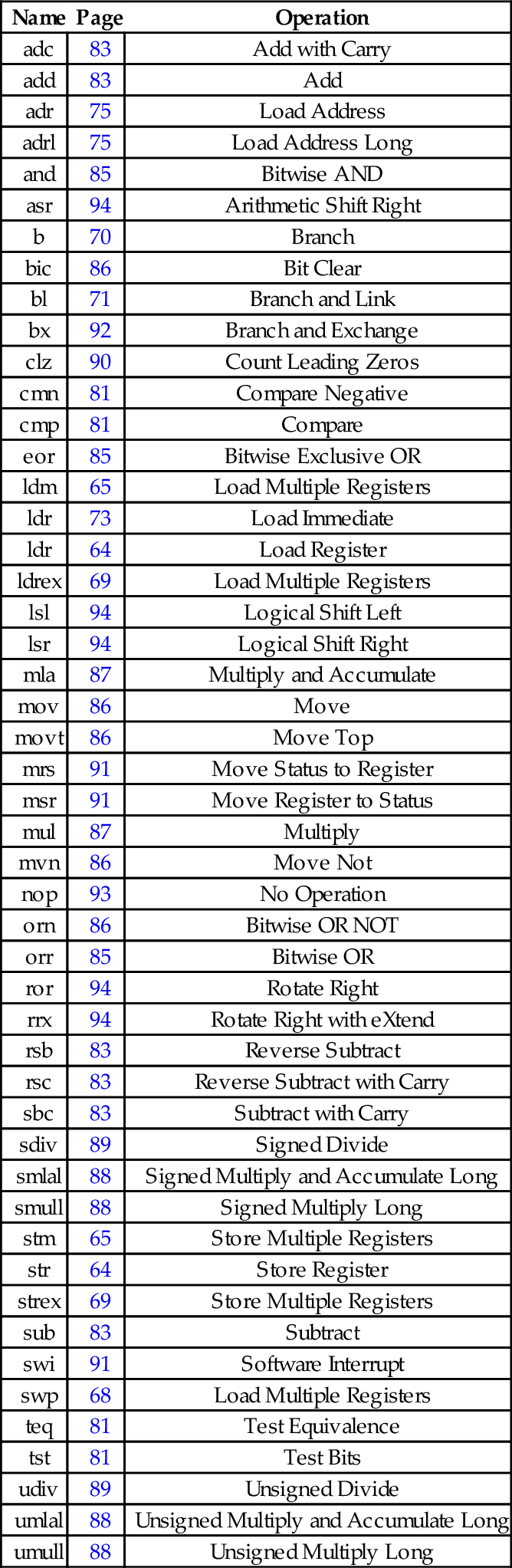

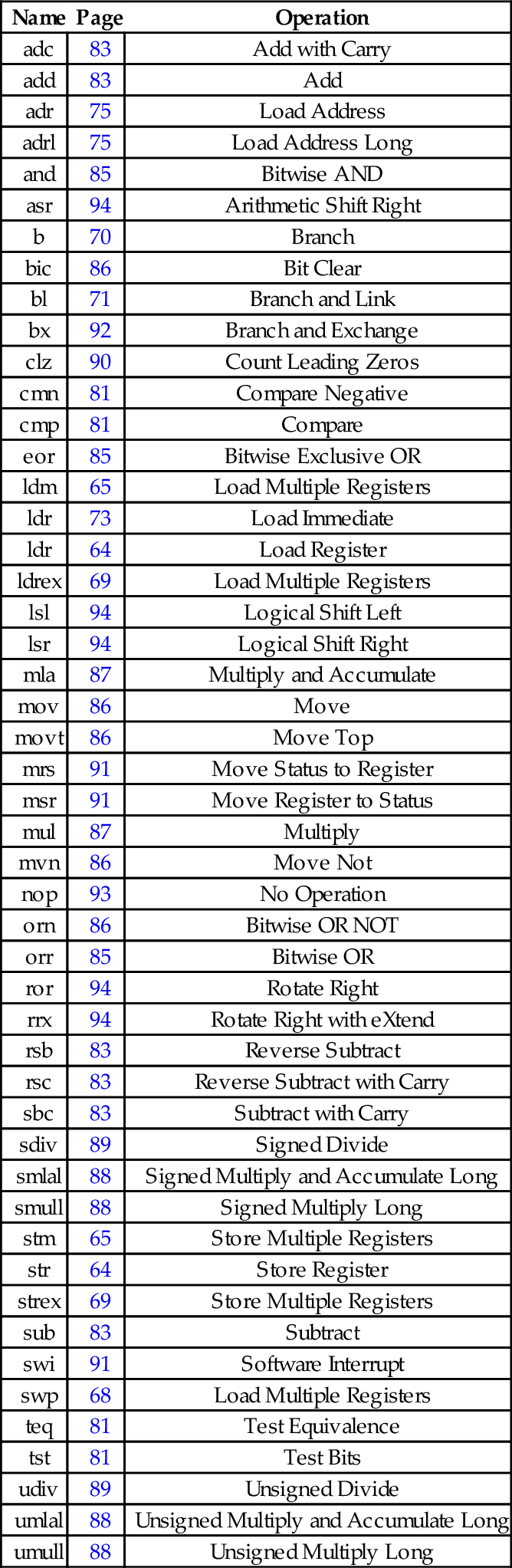

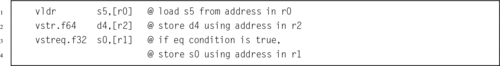

4.4 Alphabetized List of ARM Instructions

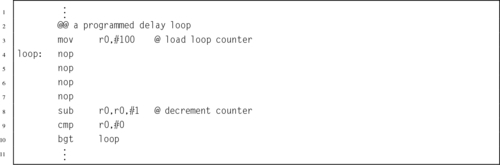

Chapter 5: Structured Programming

Chapter 6: Abstract Data Types

6.3 Ethics Case Study: Therac-25

Part II: Performance Mathematics

Chapter 7: Integer Mathematics

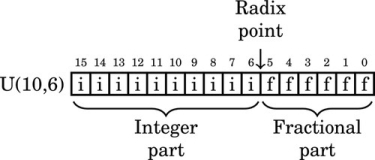

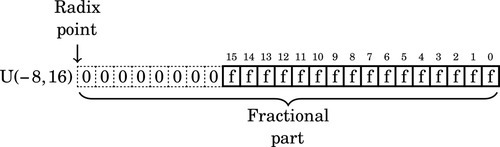

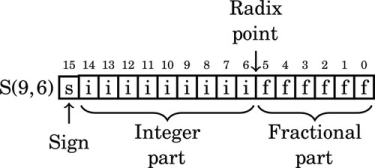

Chapter 8: Non-Integral Mathematics

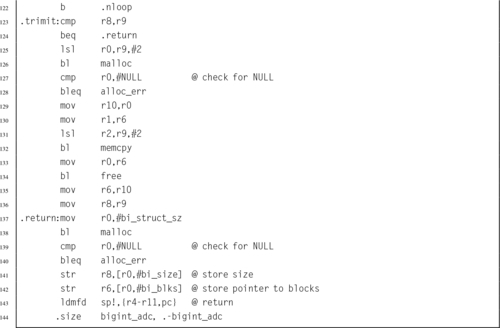

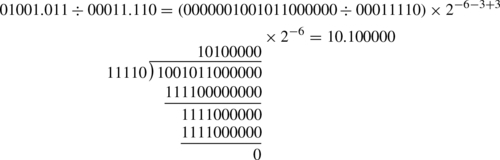

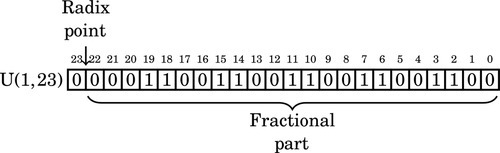

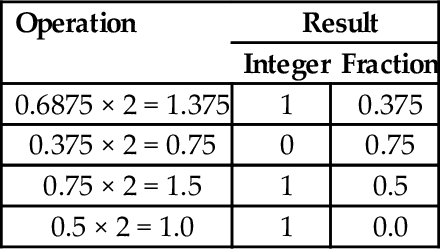

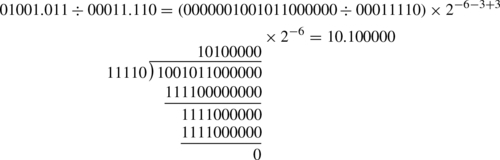

8.1 Base Conversion of Fractional Numbers

8.8 Ethics Case Study: Patriot Missile Failure

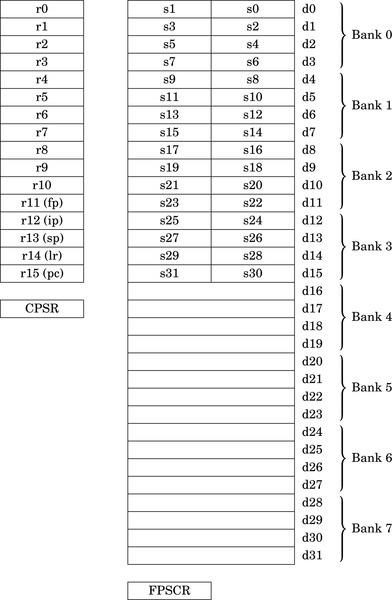

Chapter 9: The ARM Vector Floating Point Coprocessor

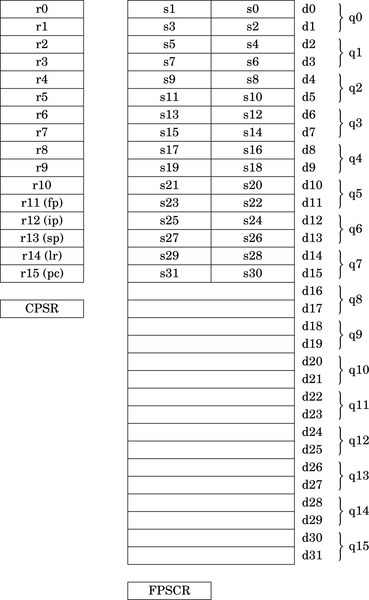

9.1 Vector Floating Point Overview

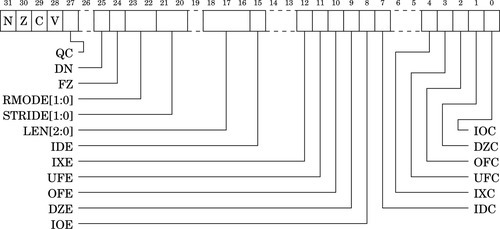

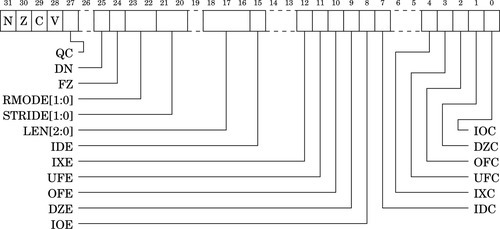

9.2 Floating Point Status and Control Register

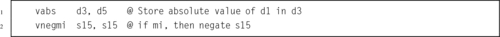

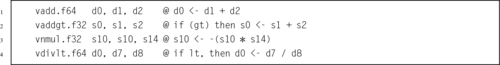

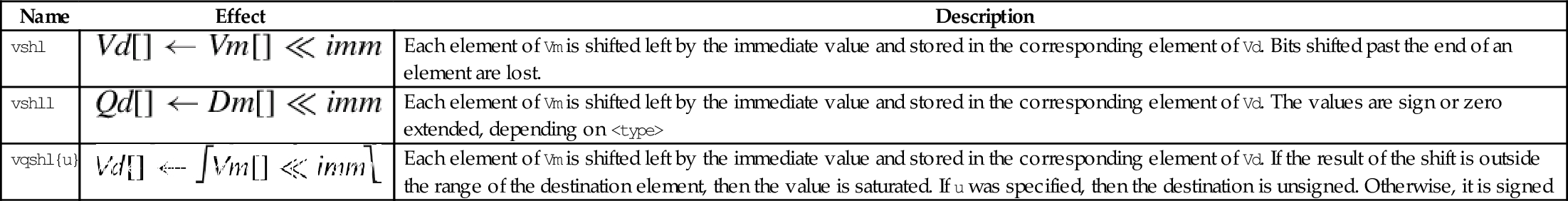

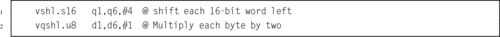

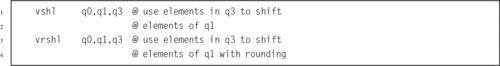

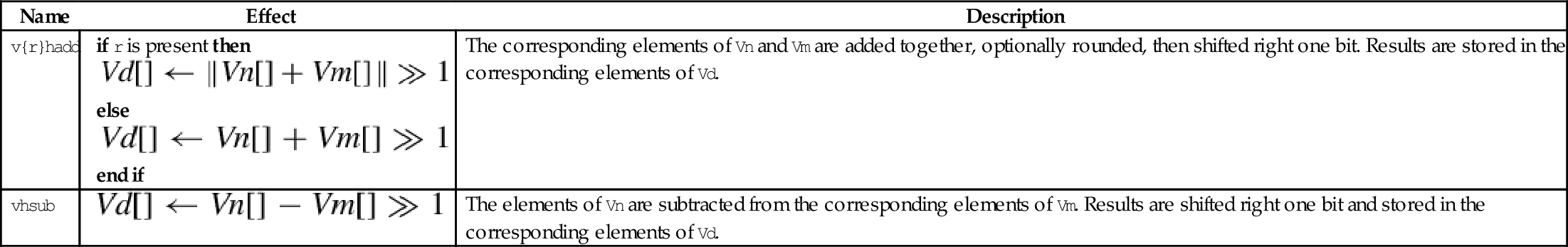

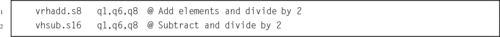

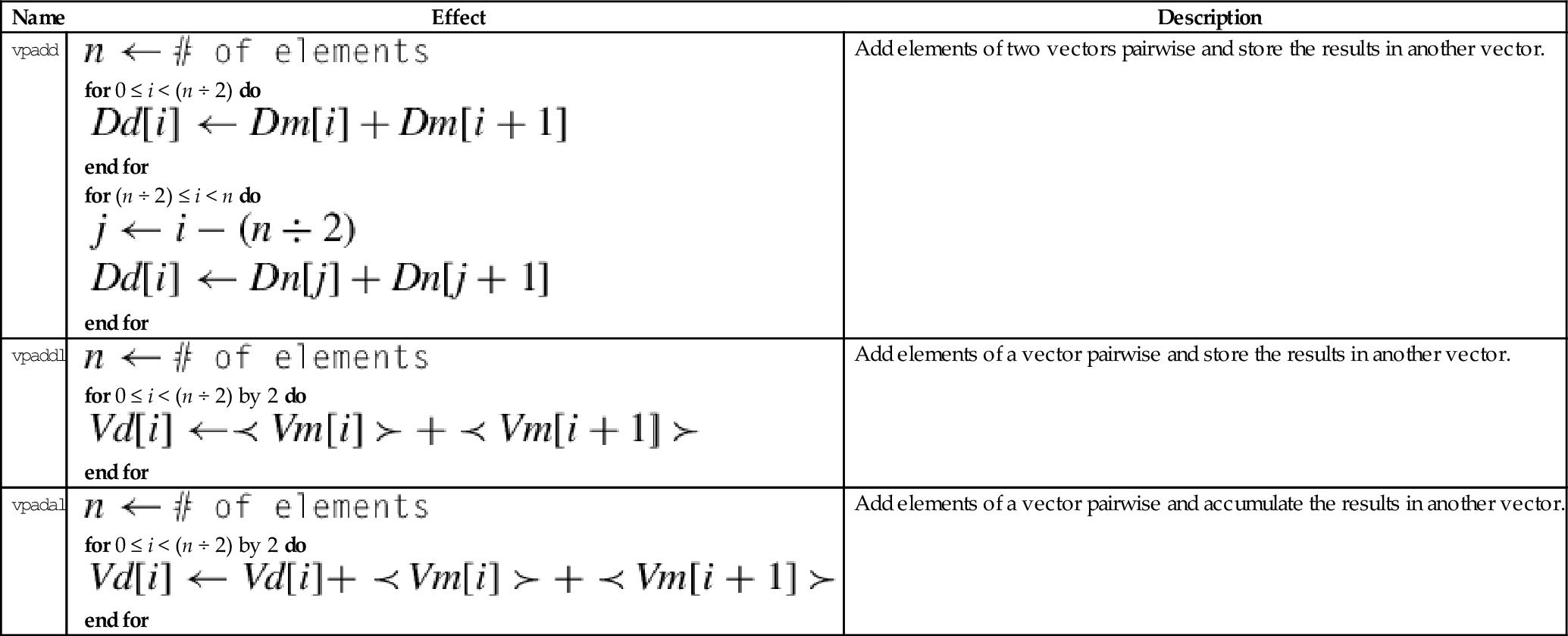

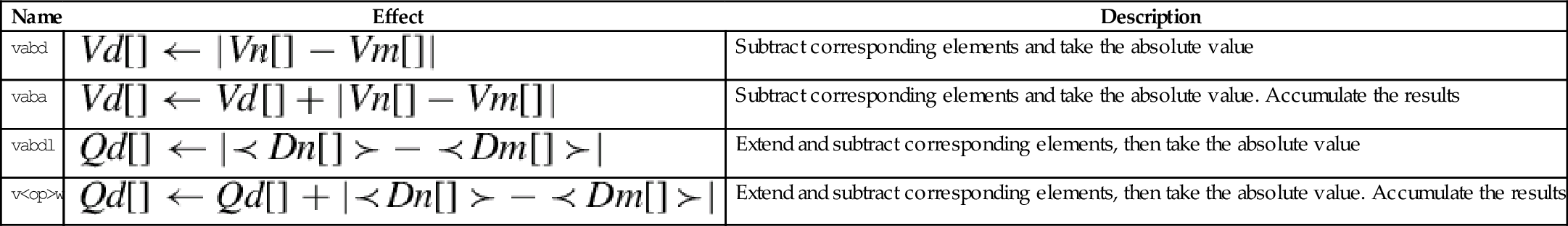

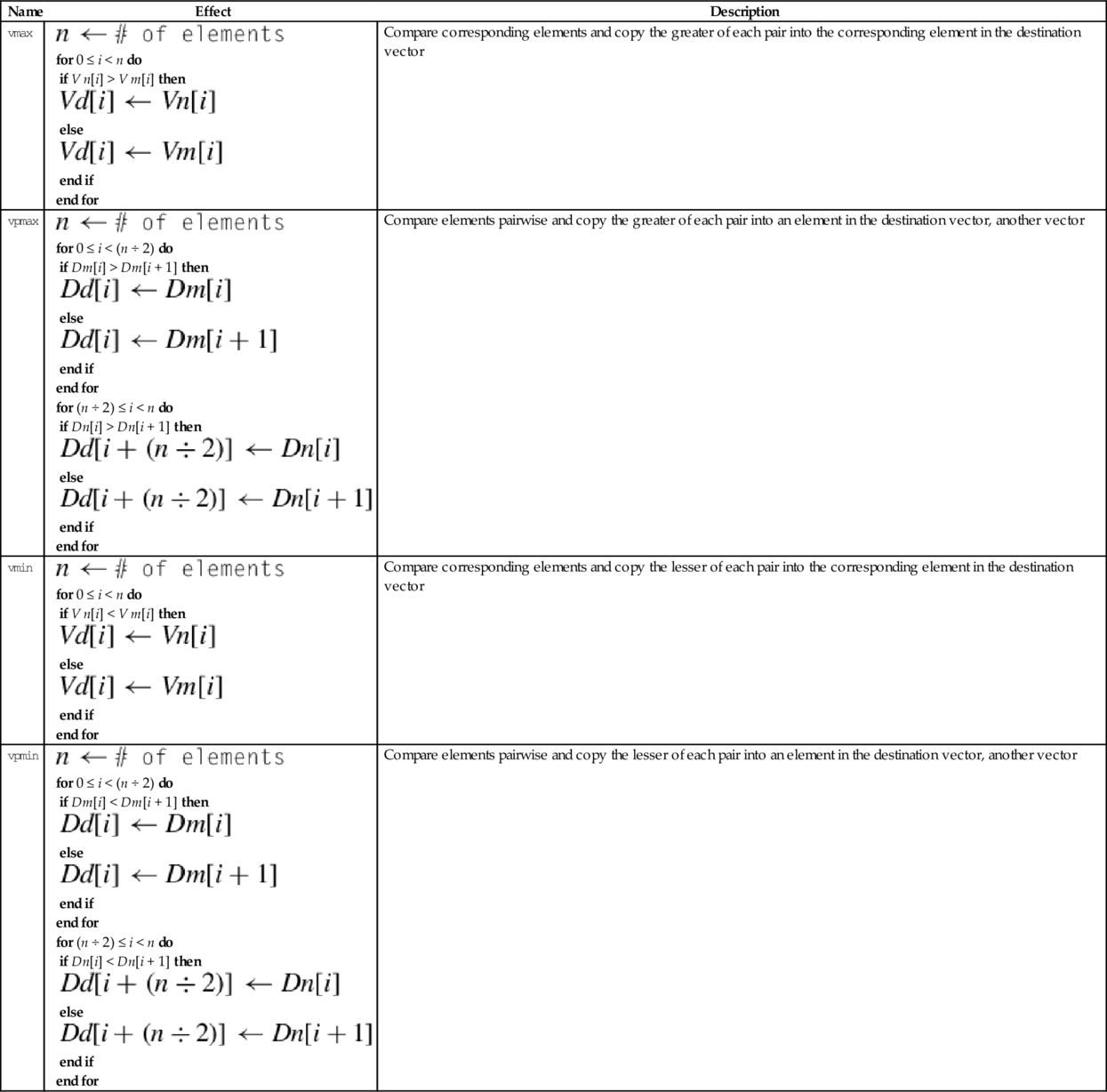

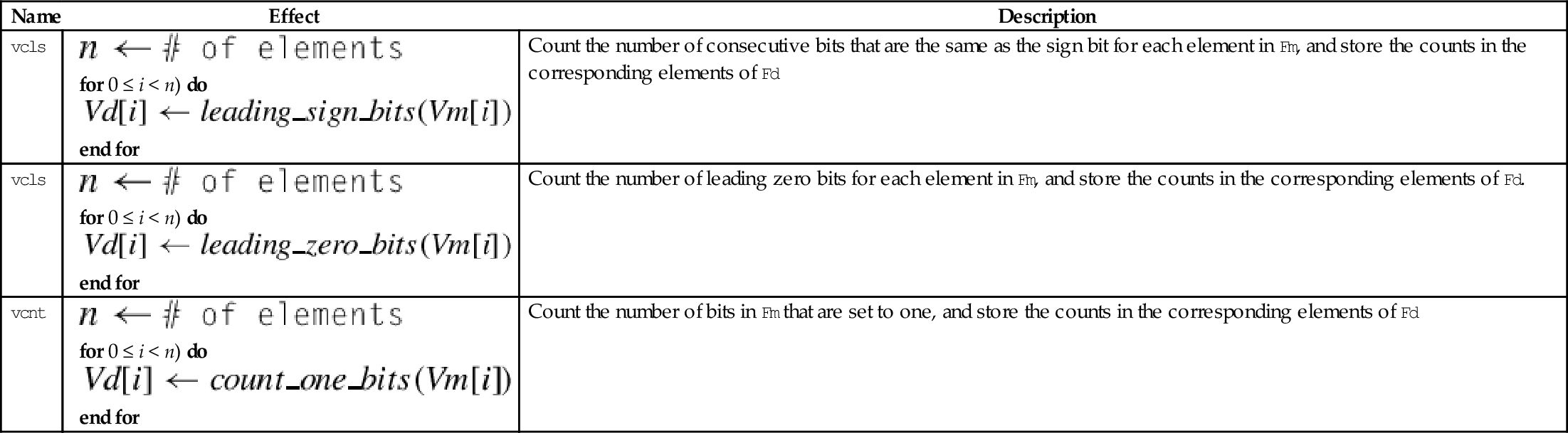

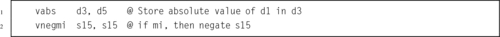

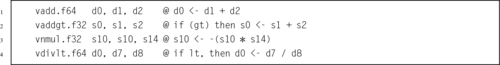

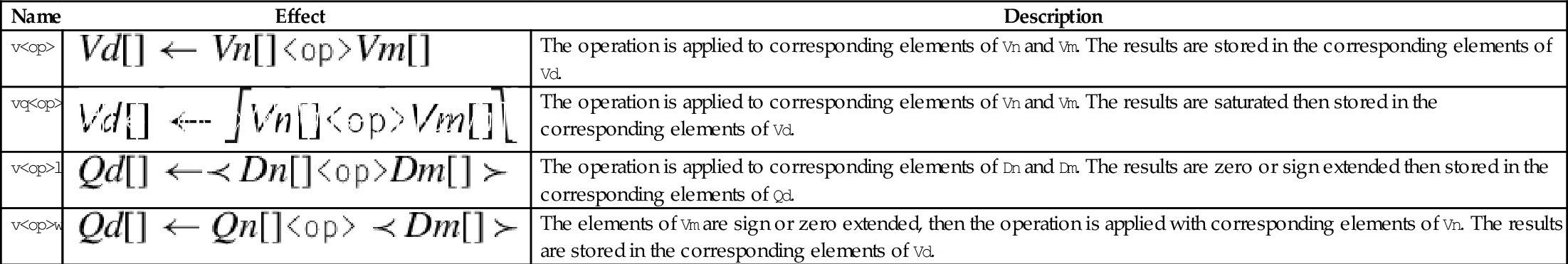

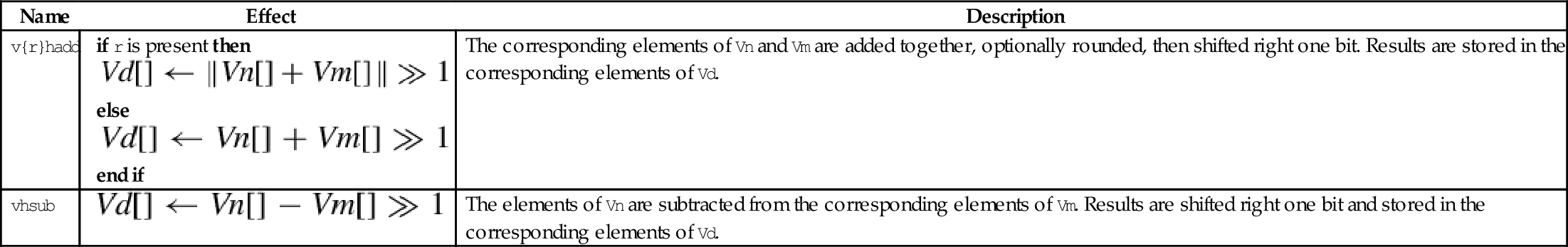

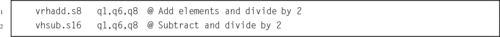

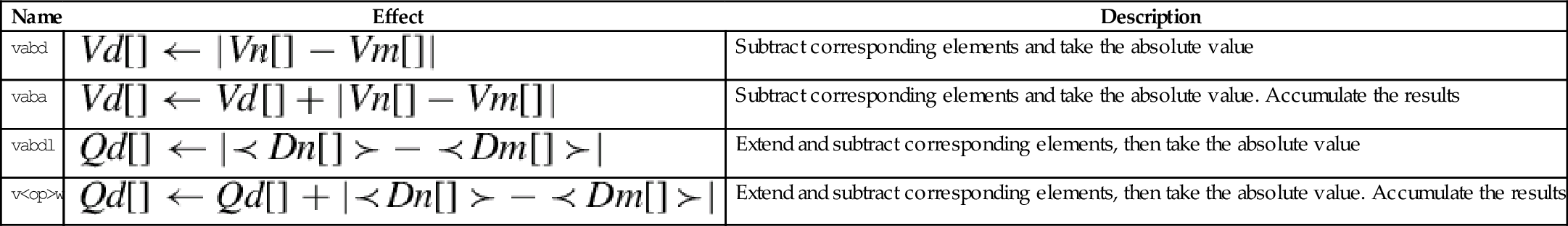

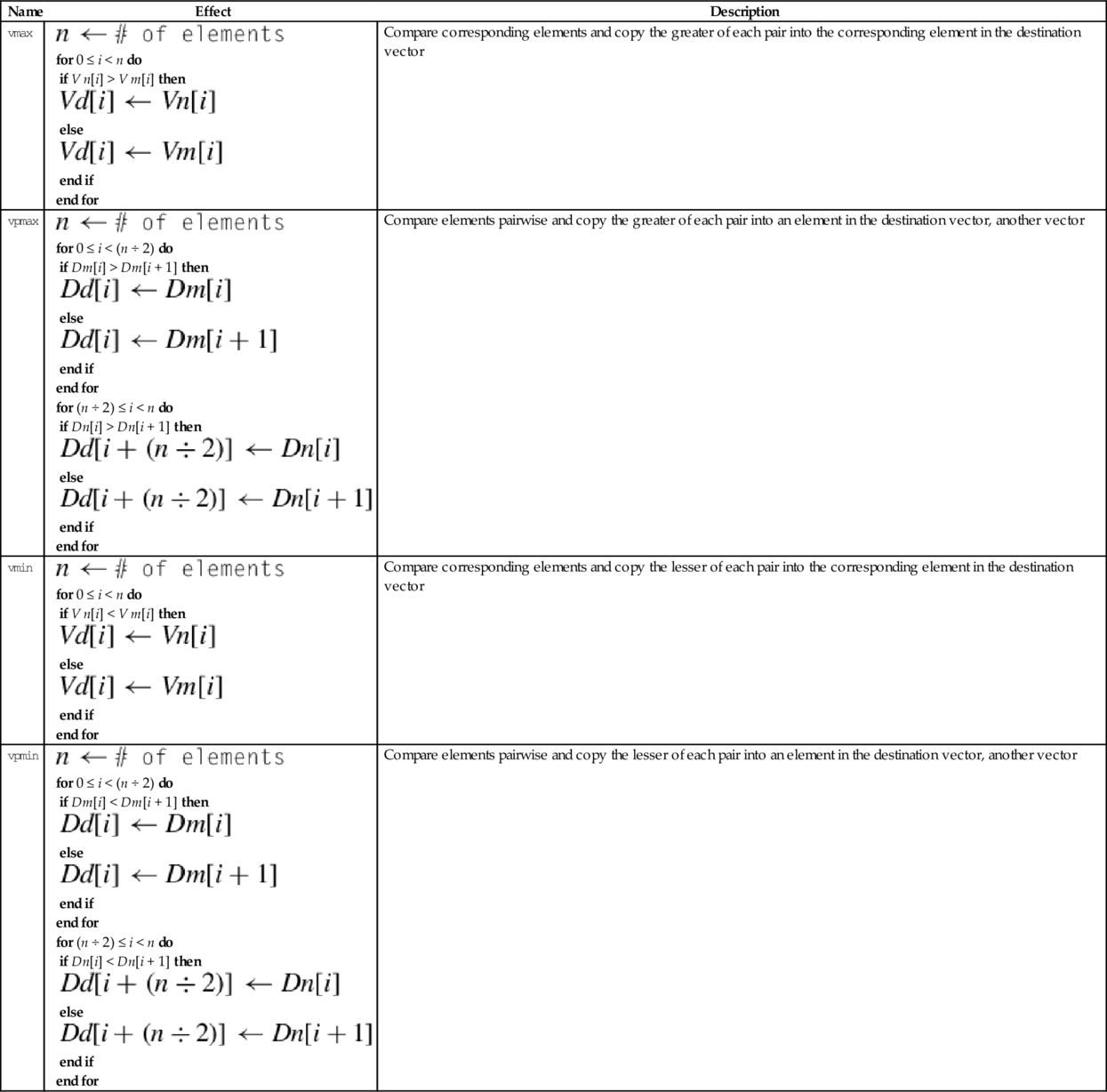

9.5 Data Processing Instructions

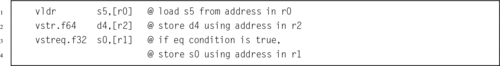

9.6 Data Movement Instructions

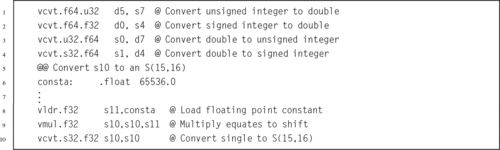

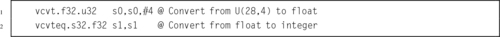

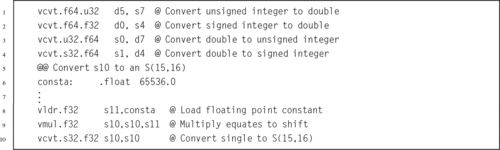

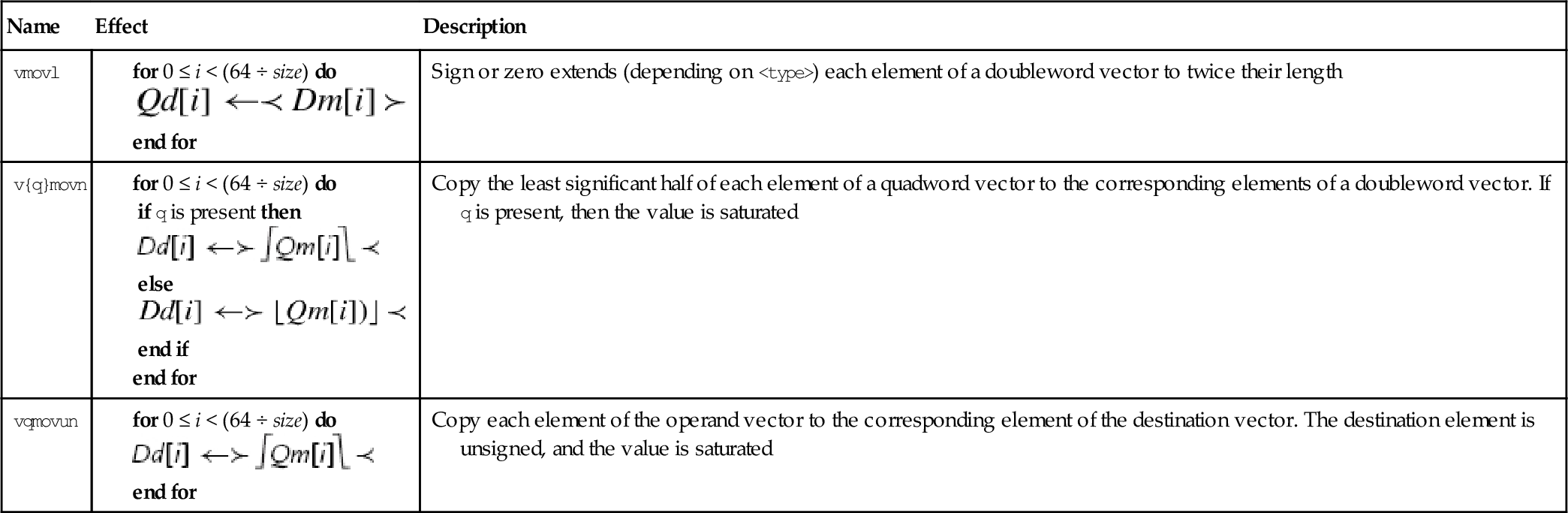

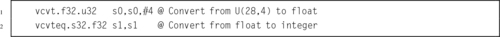

9.7 Data Conversion Instructions

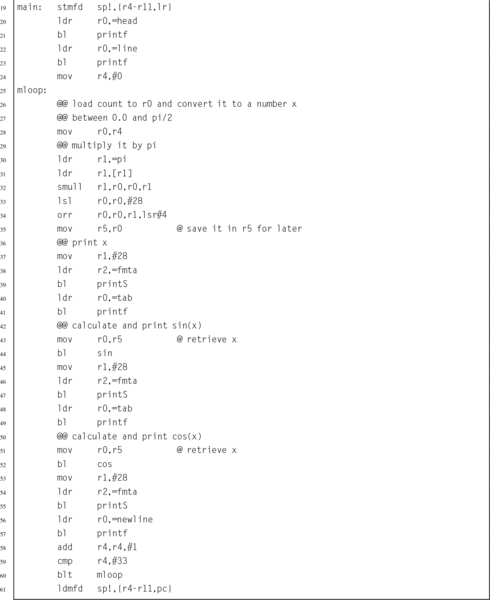

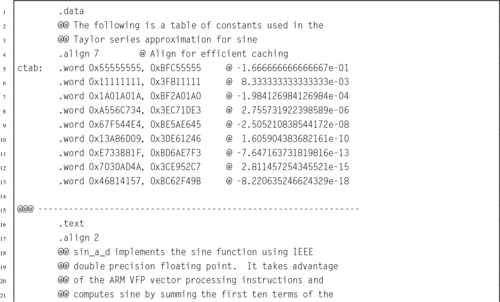

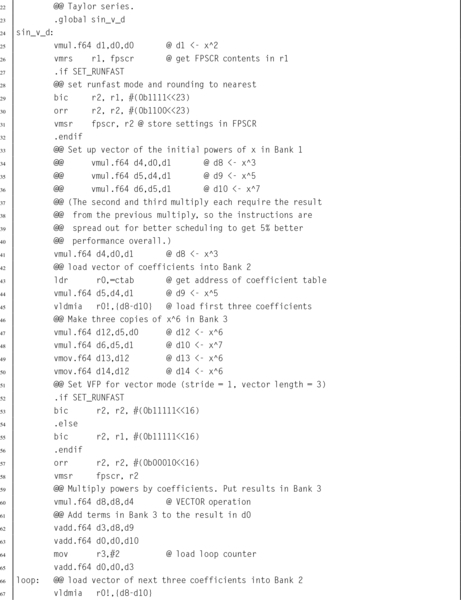

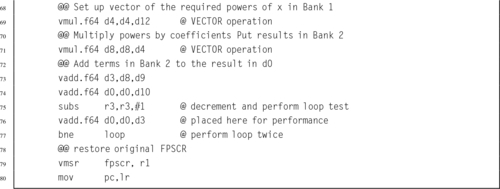

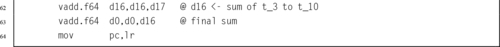

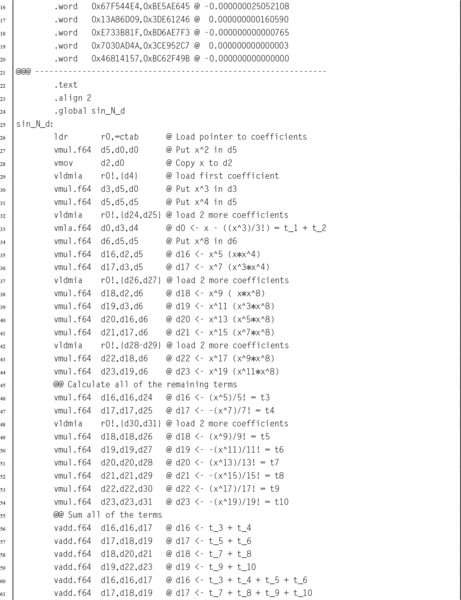

9.8 Floating Point Sine Function

9.9 Alphabetized List of VFP Instructions

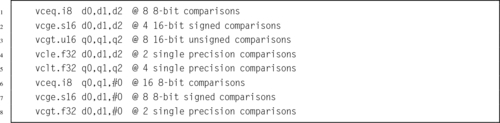

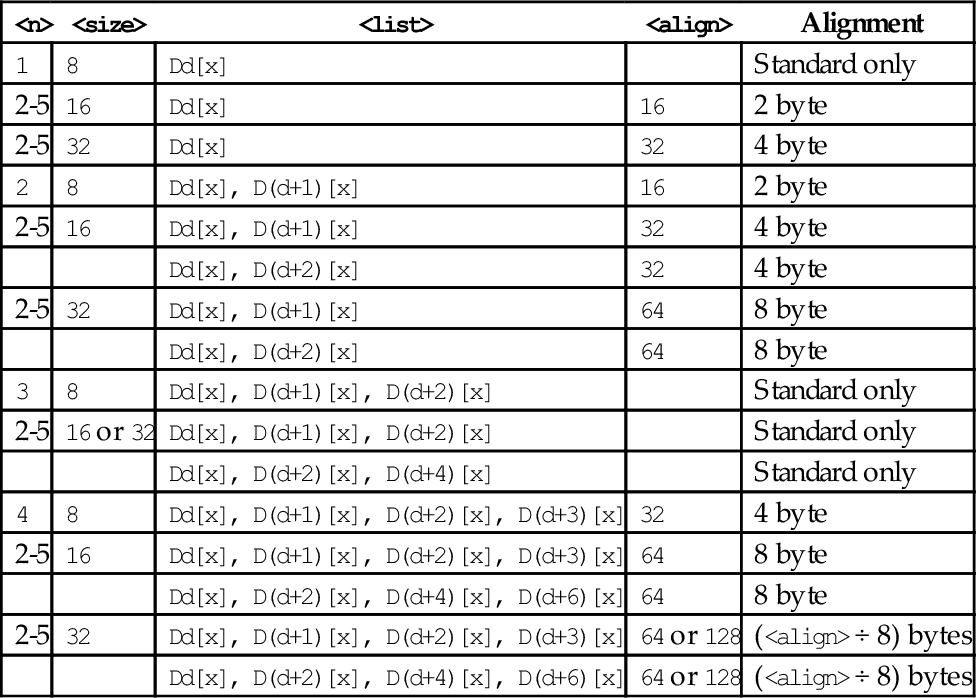

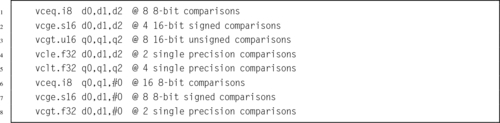

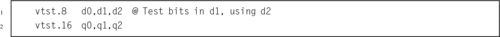

Chapter 10: The ARM NEON Extensions

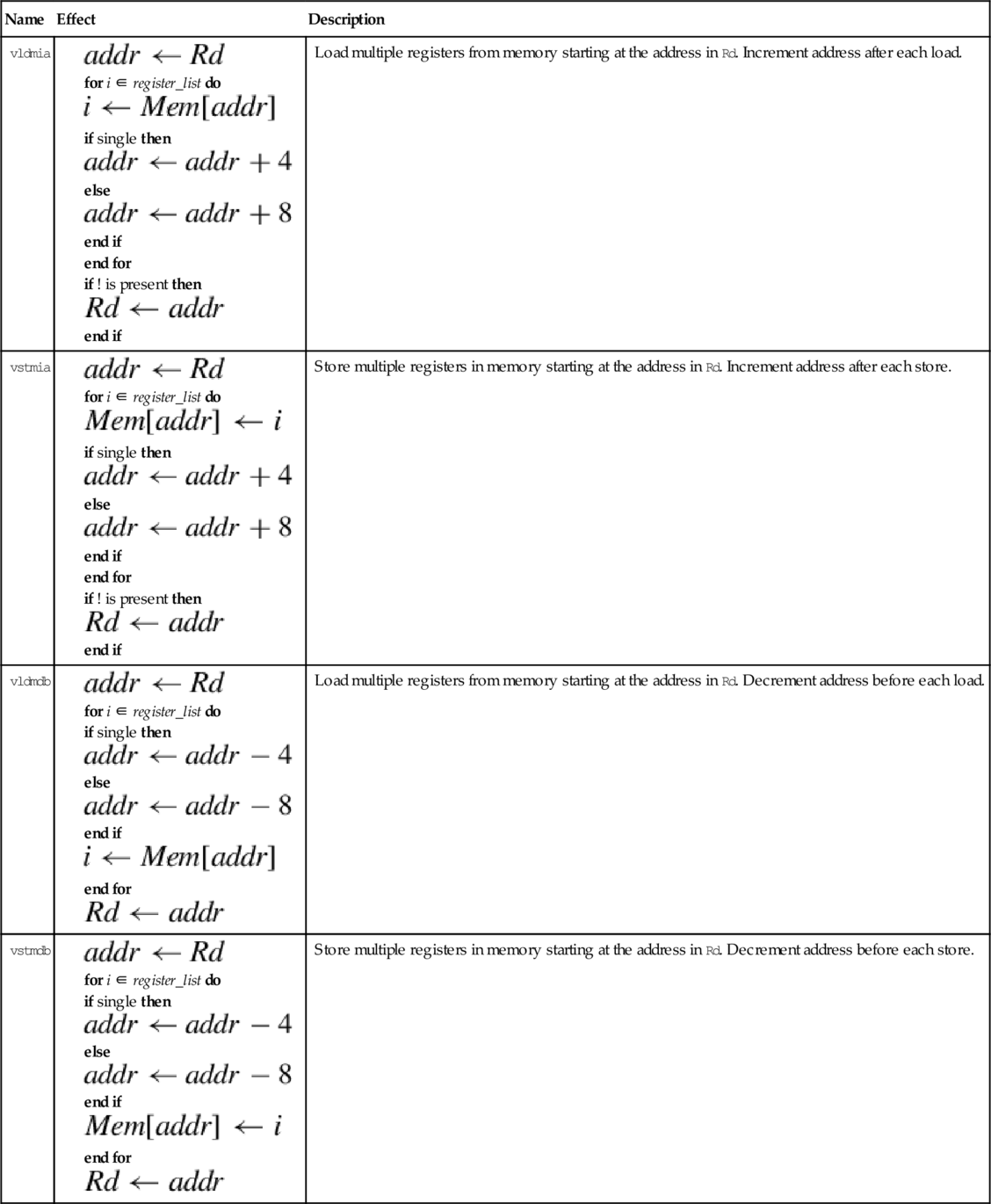

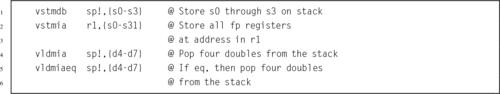

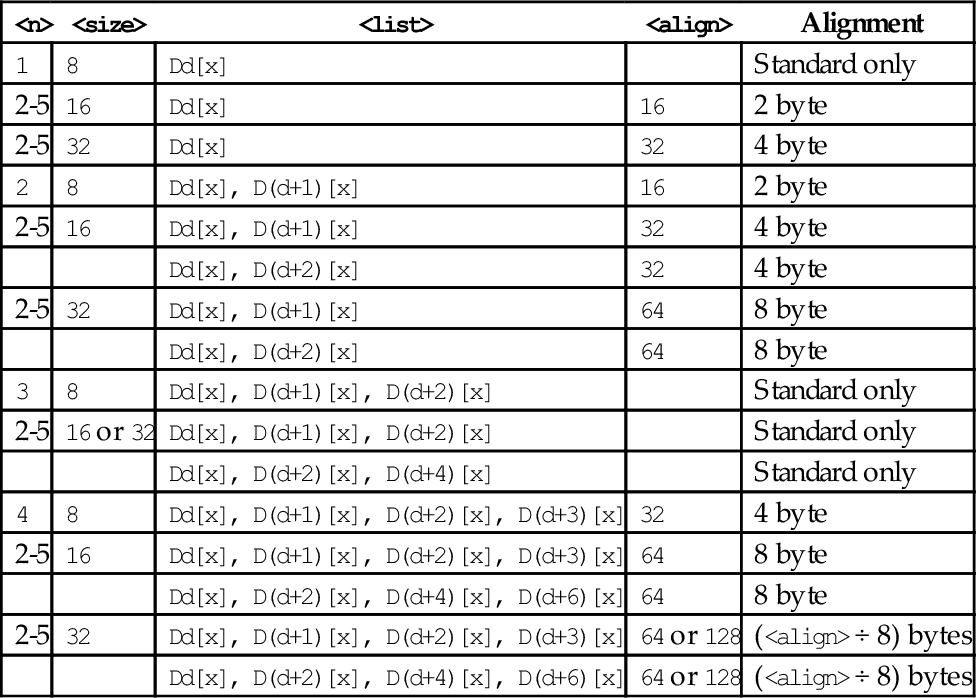

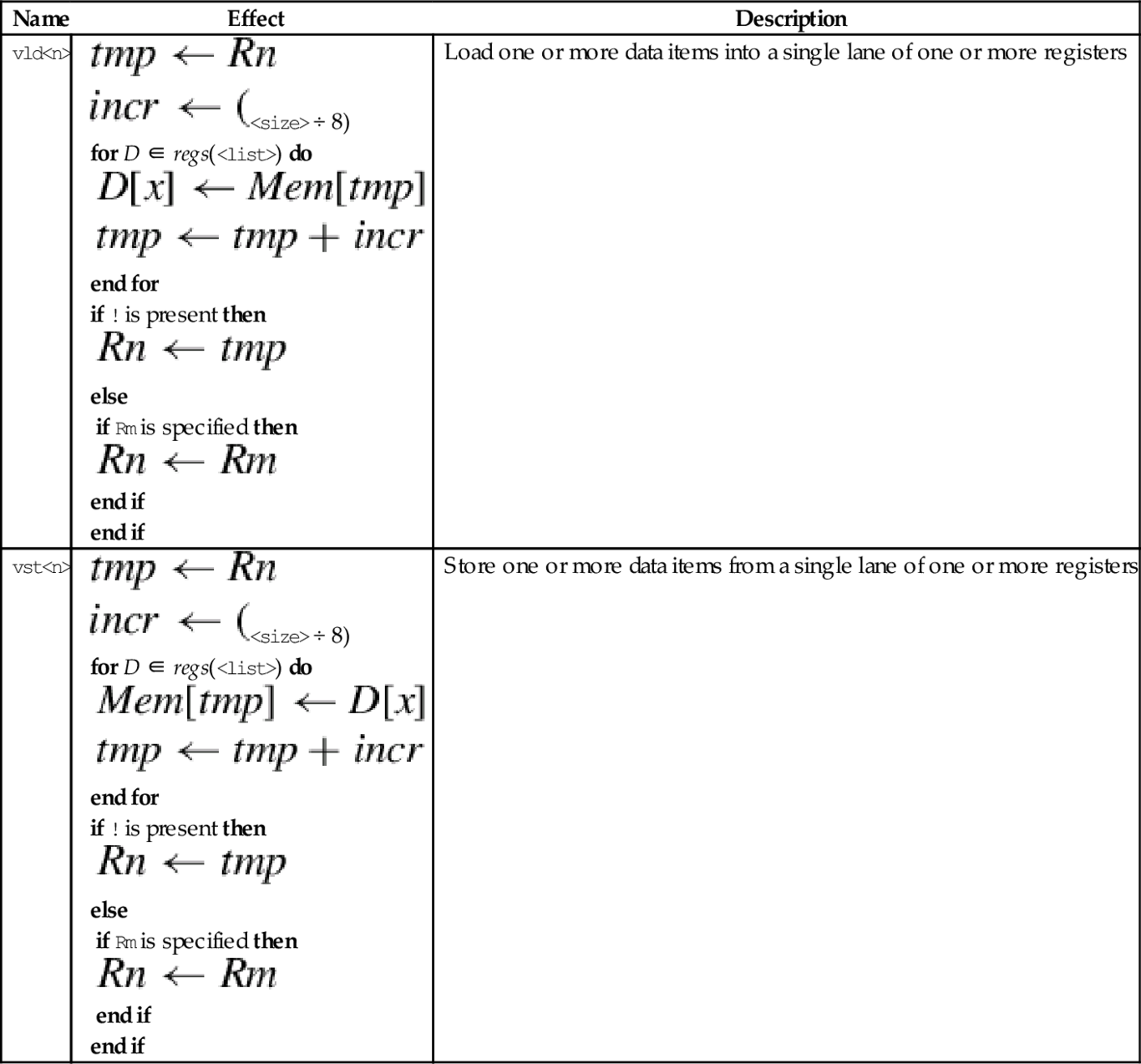

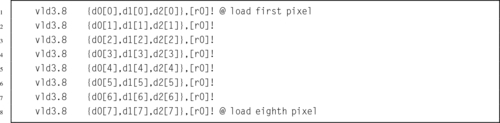

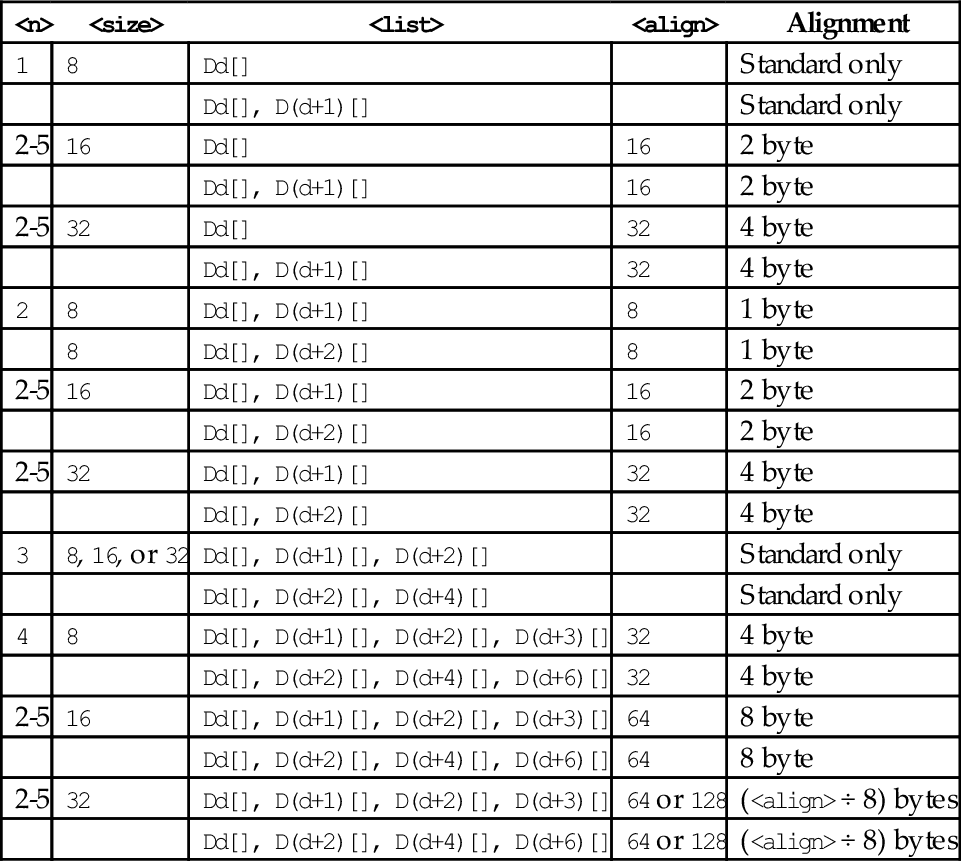

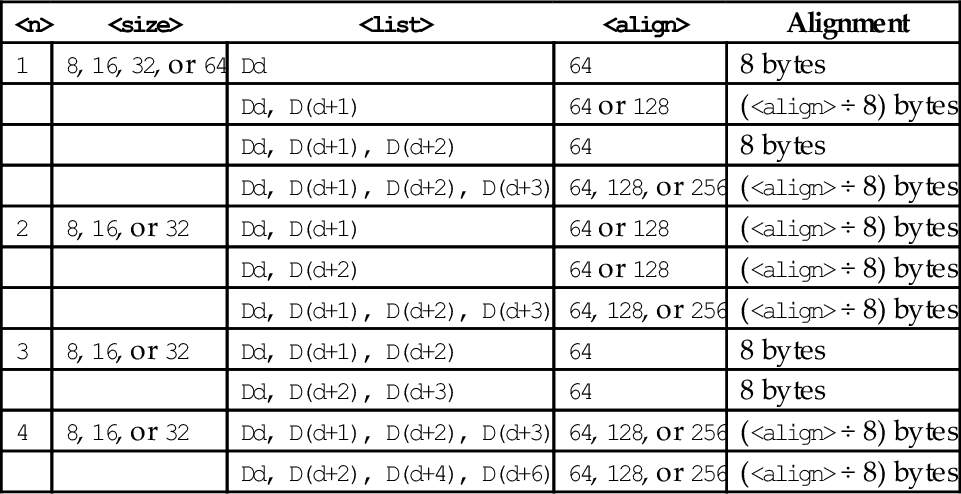

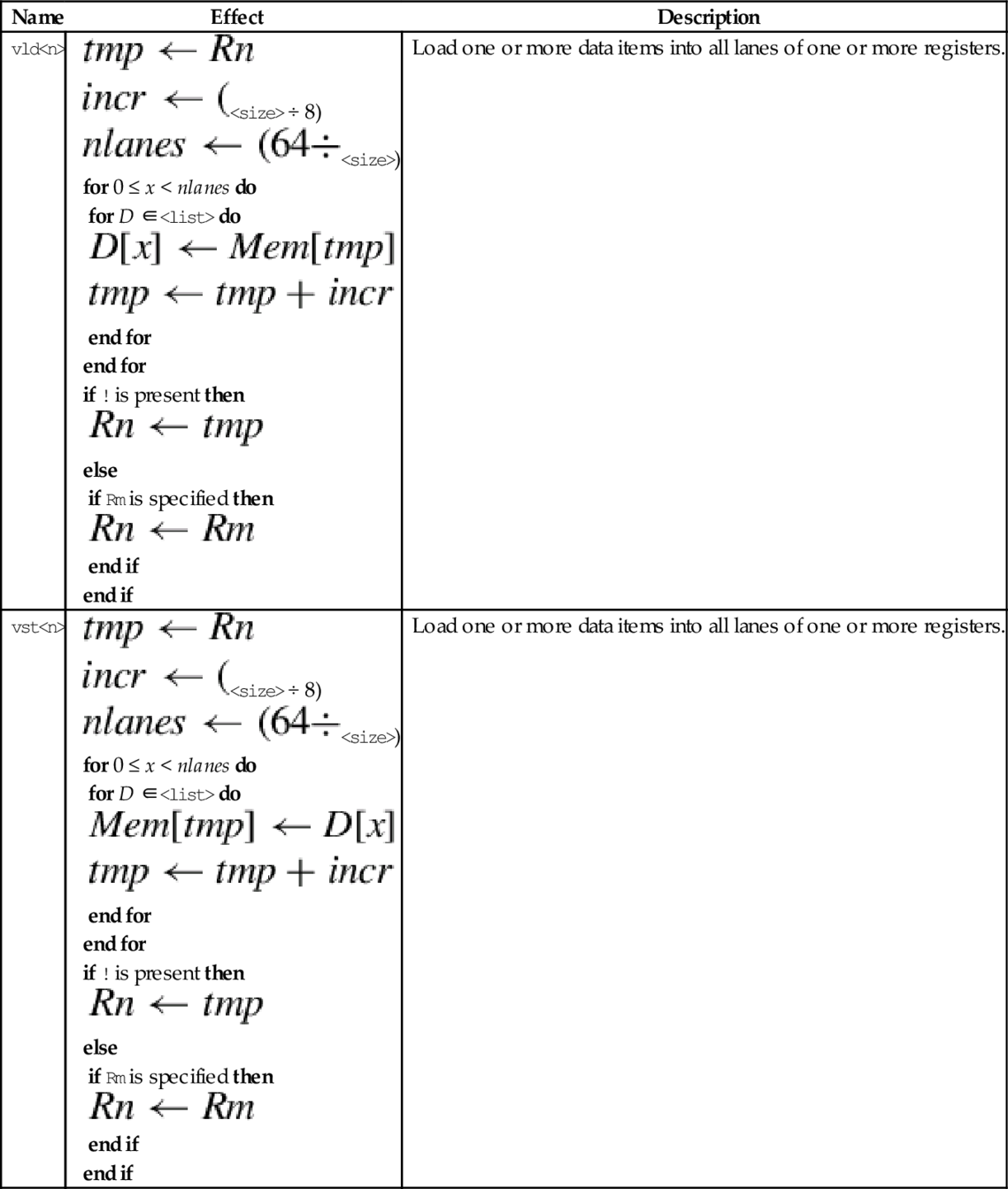

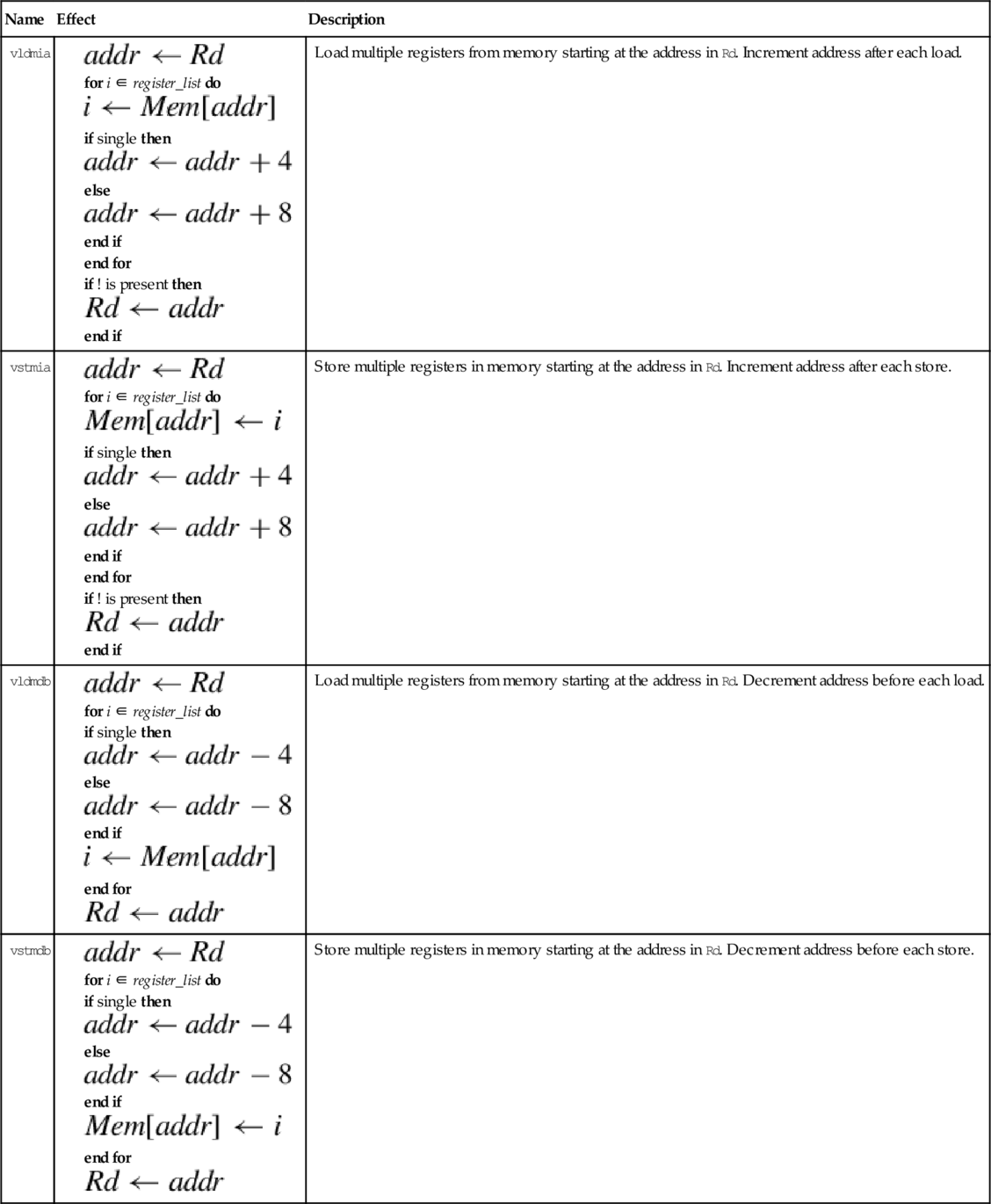

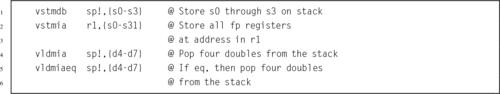

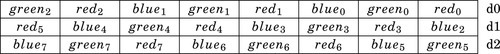

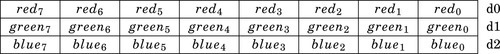

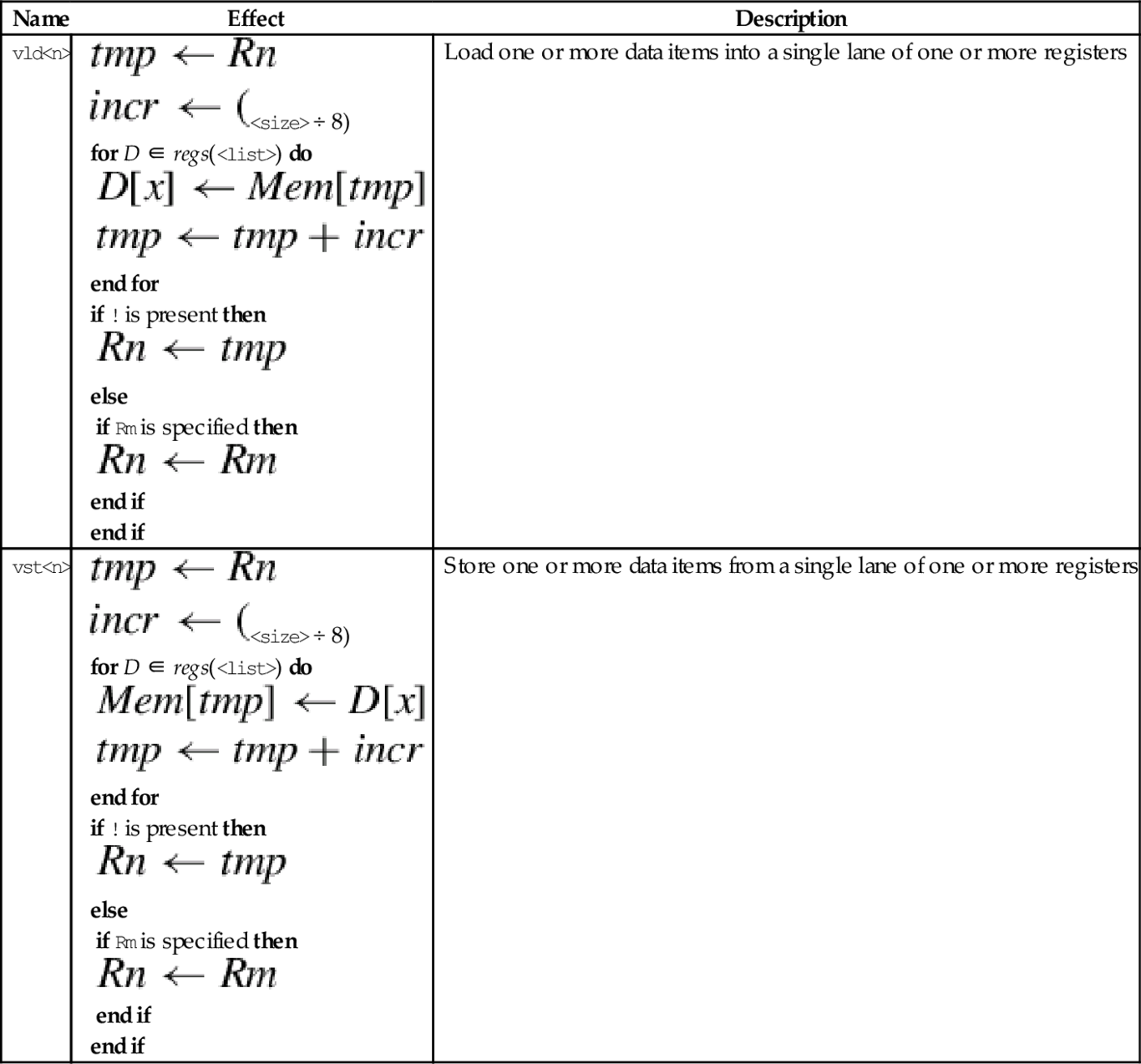

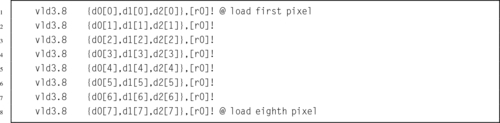

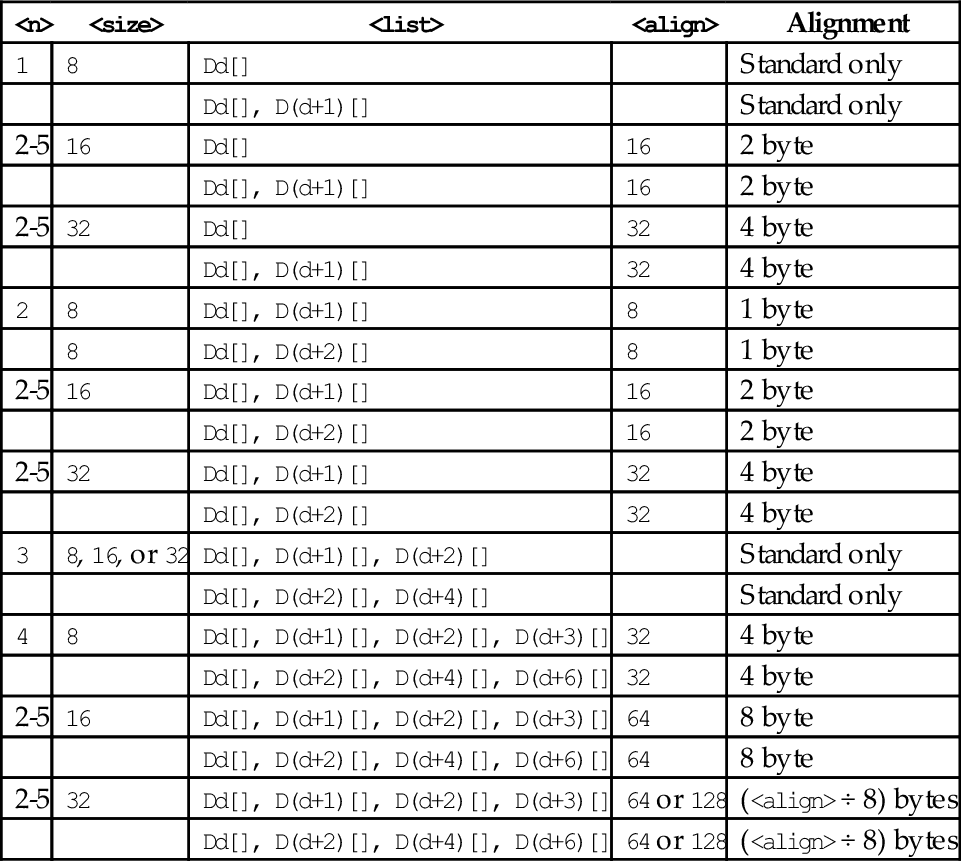

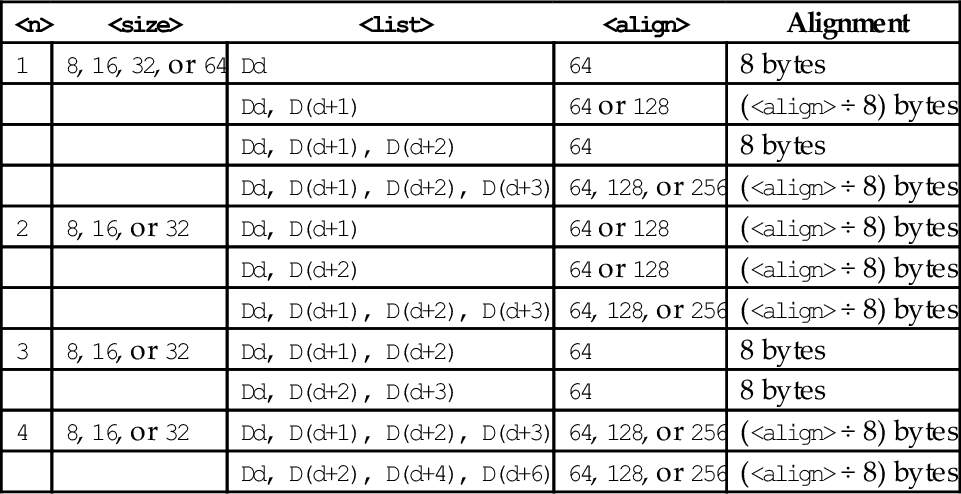

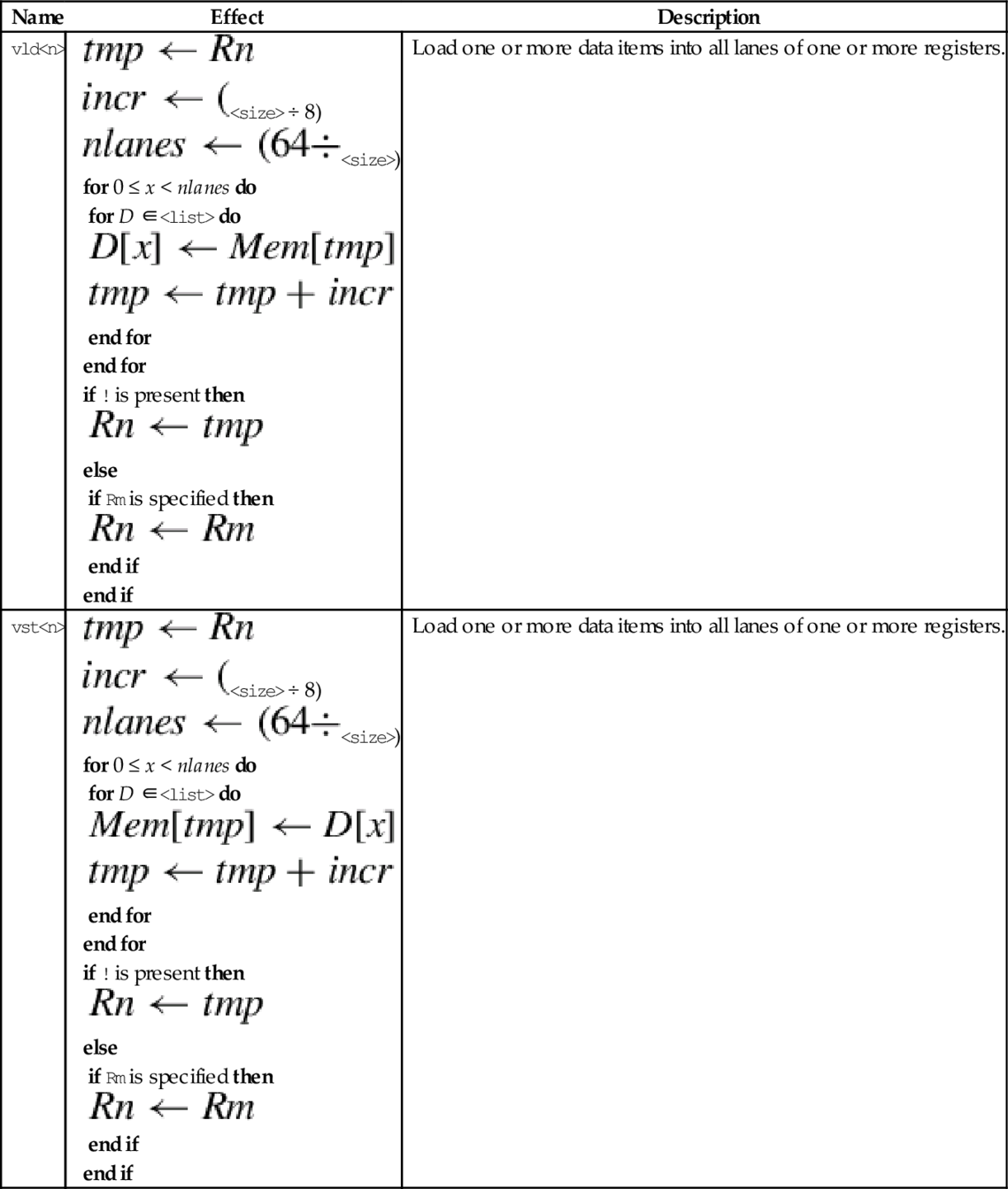

10.3 Load and Store Instructions

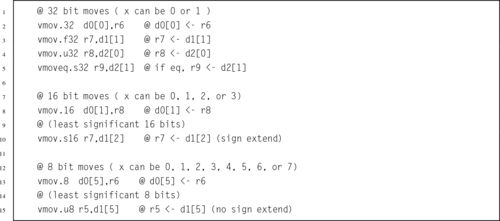

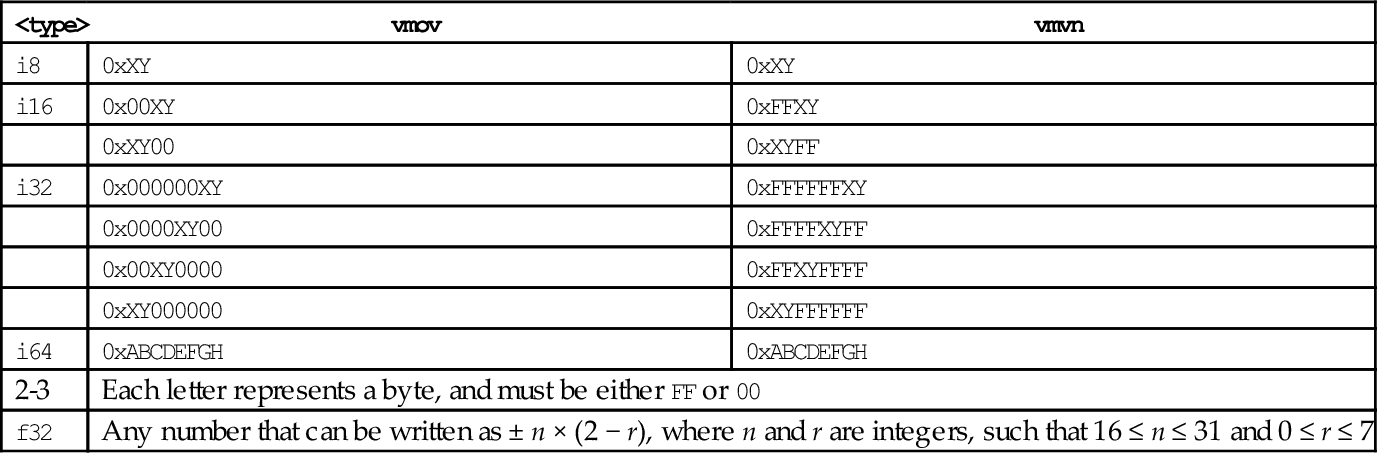

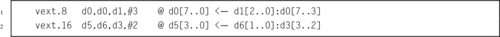

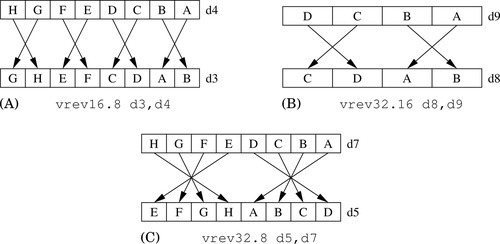

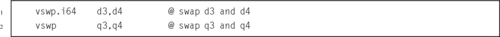

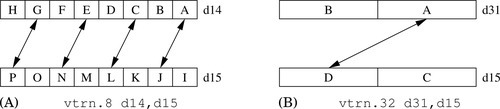

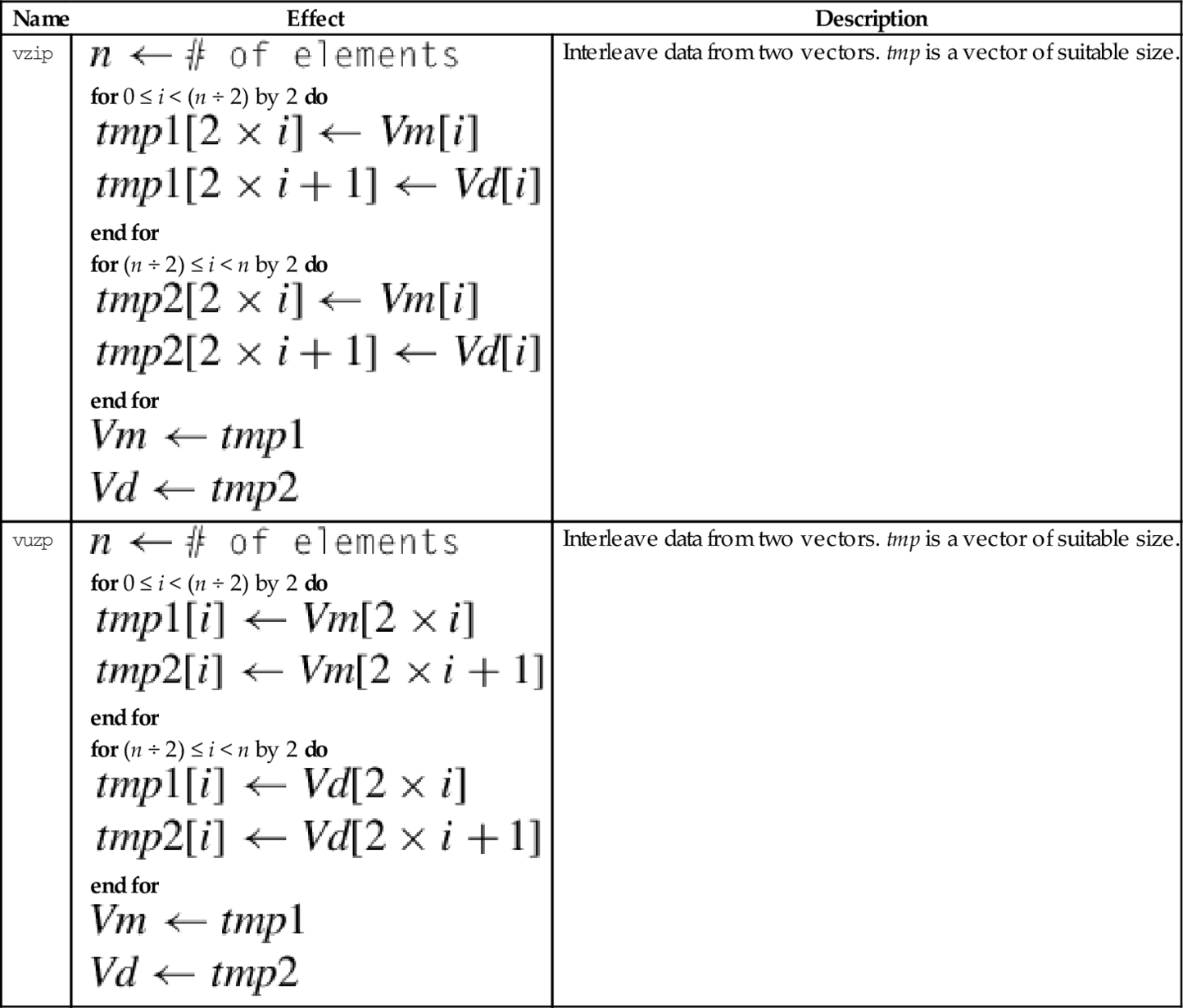

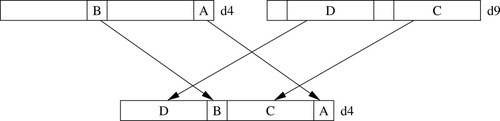

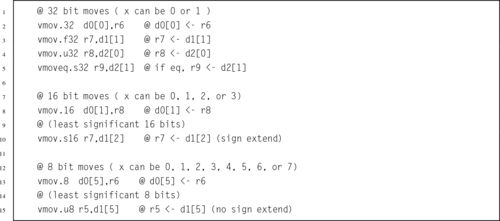

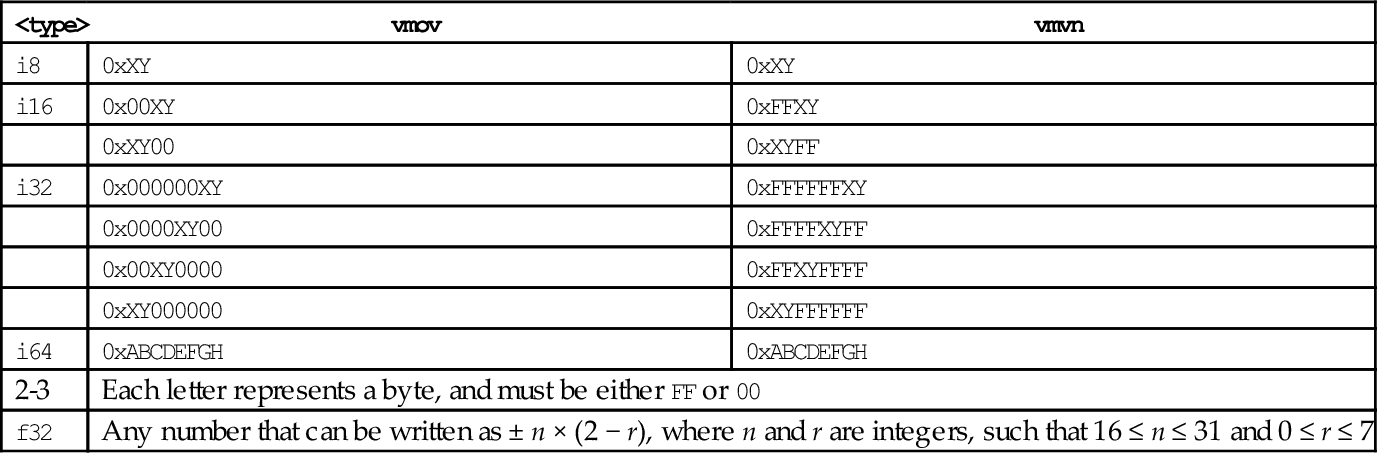

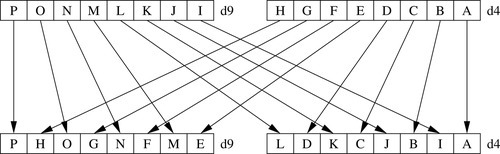

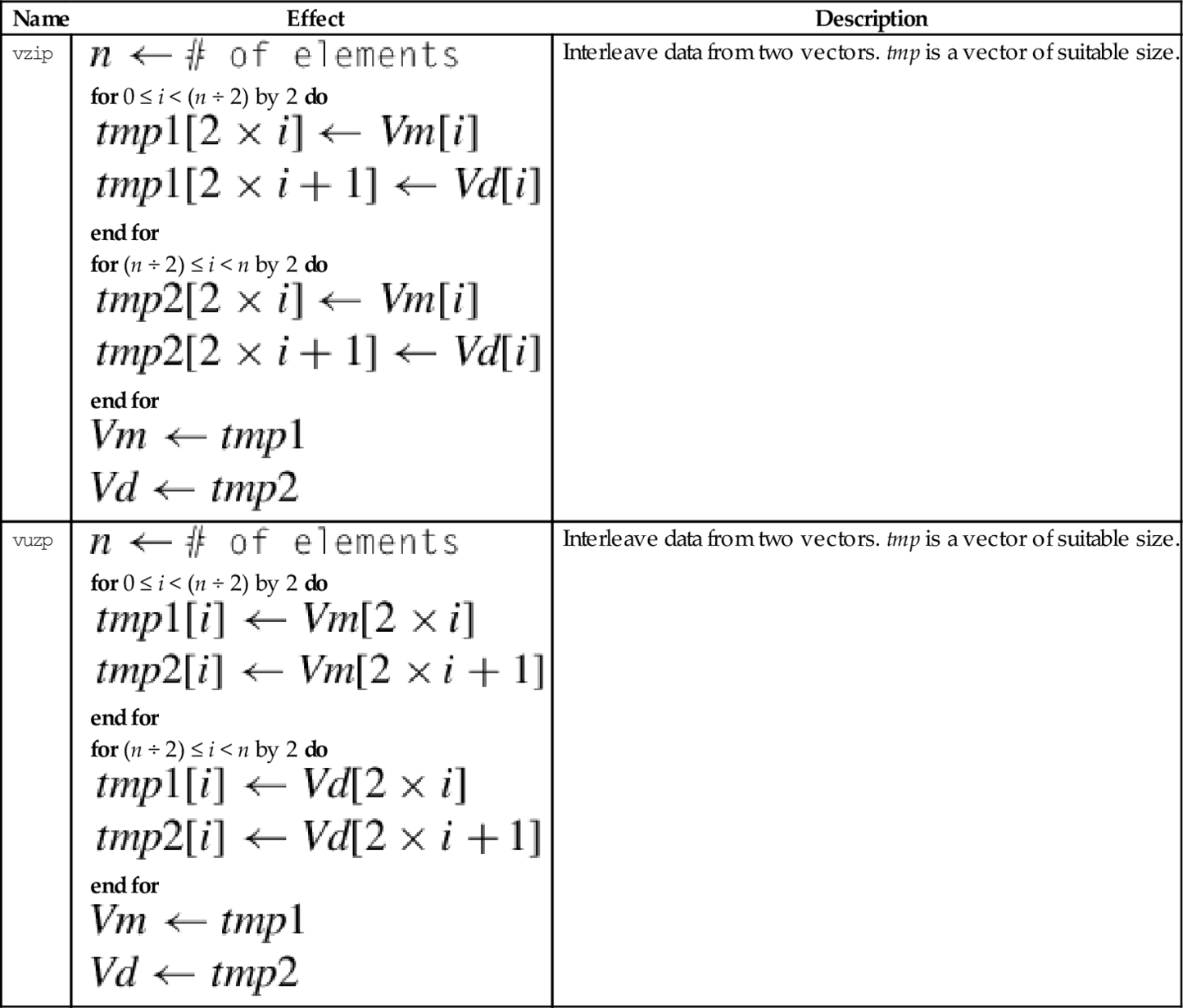

10.4 Data Movement Instructions

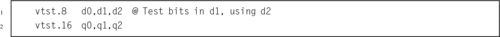

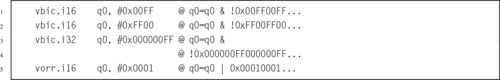

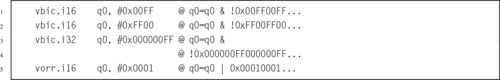

10.7 Bitwise Logical Operations

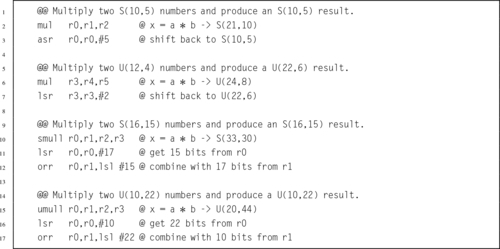

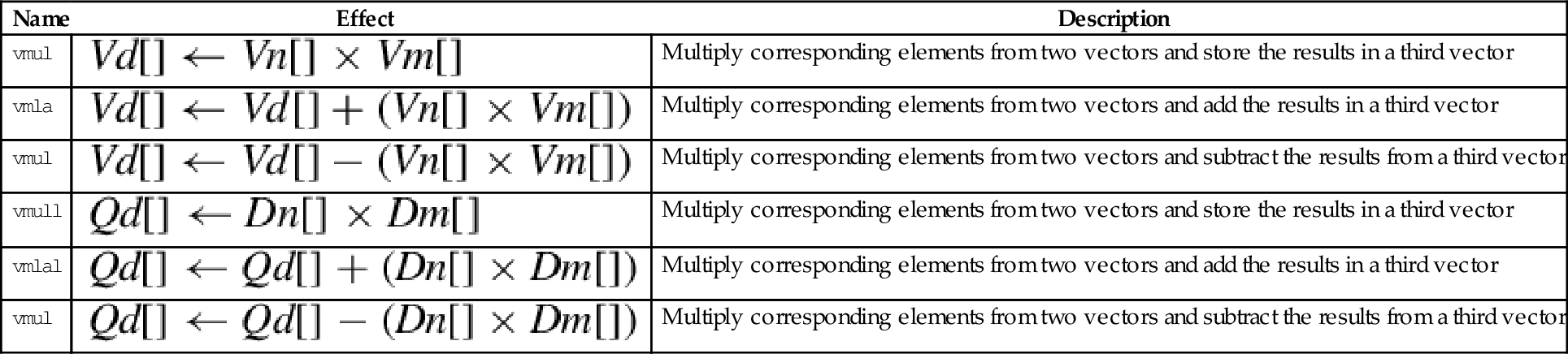

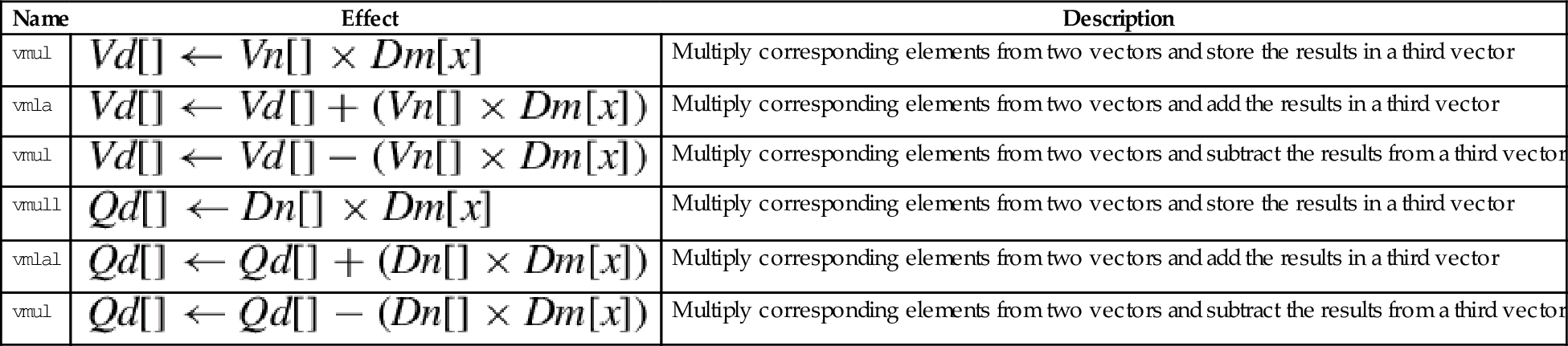

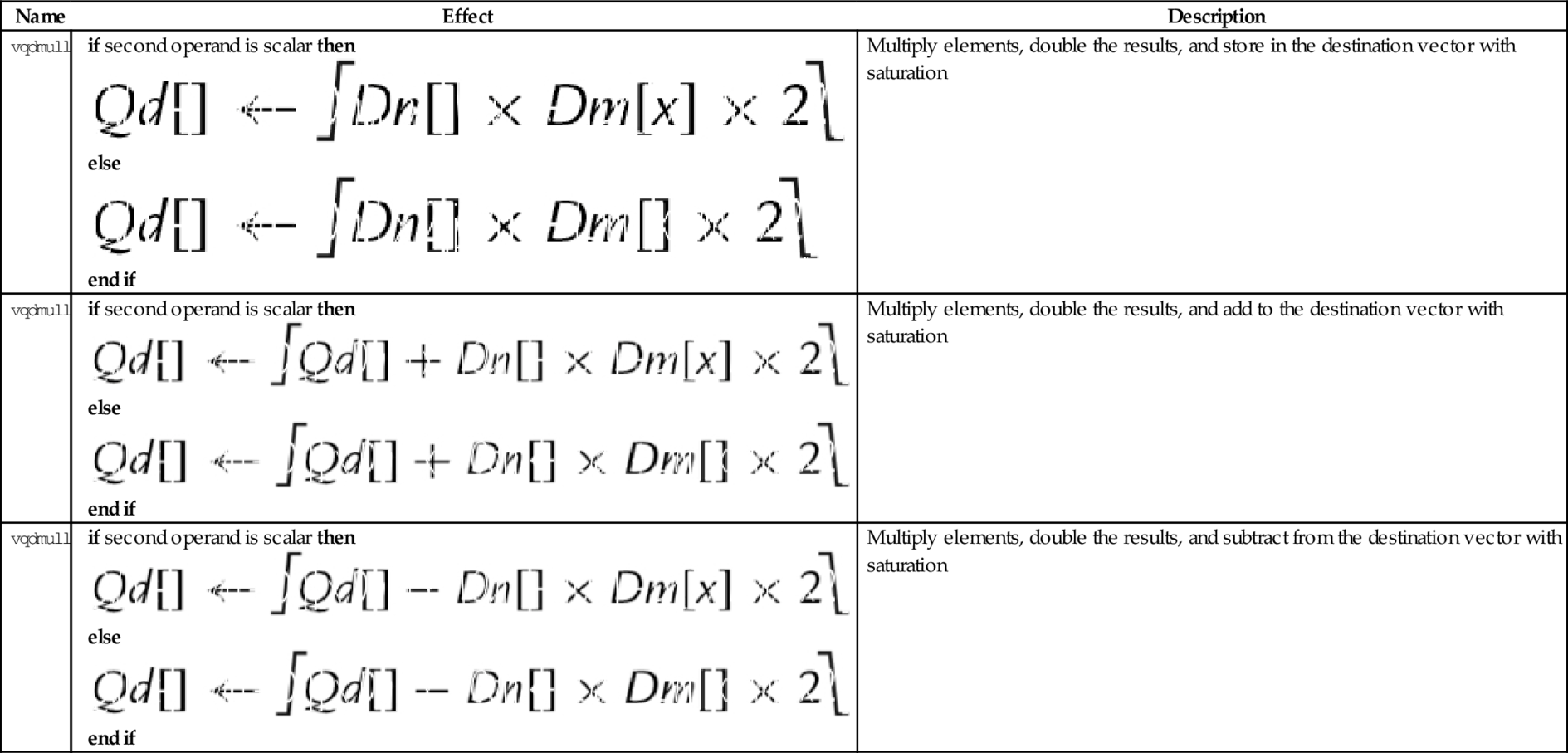

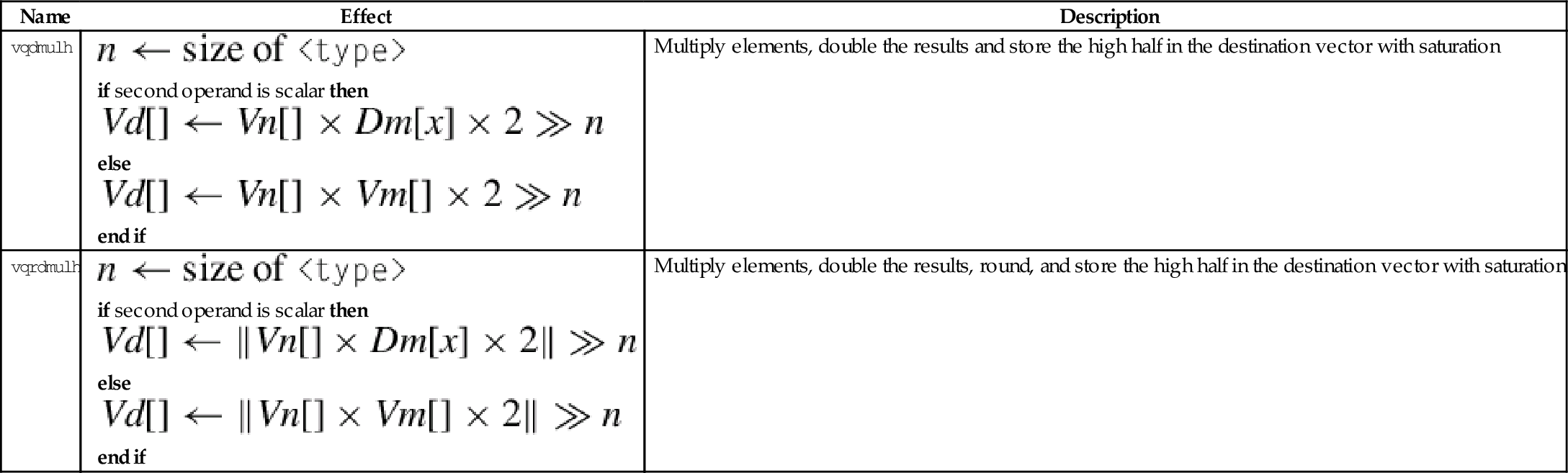

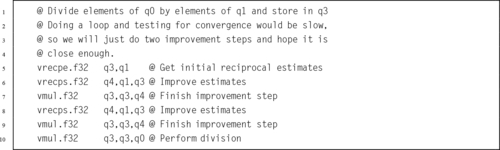

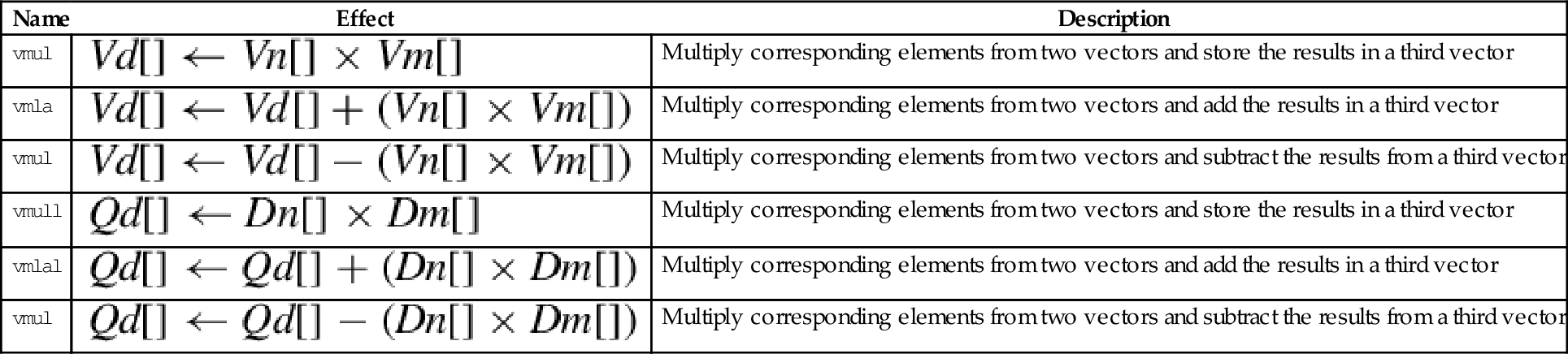

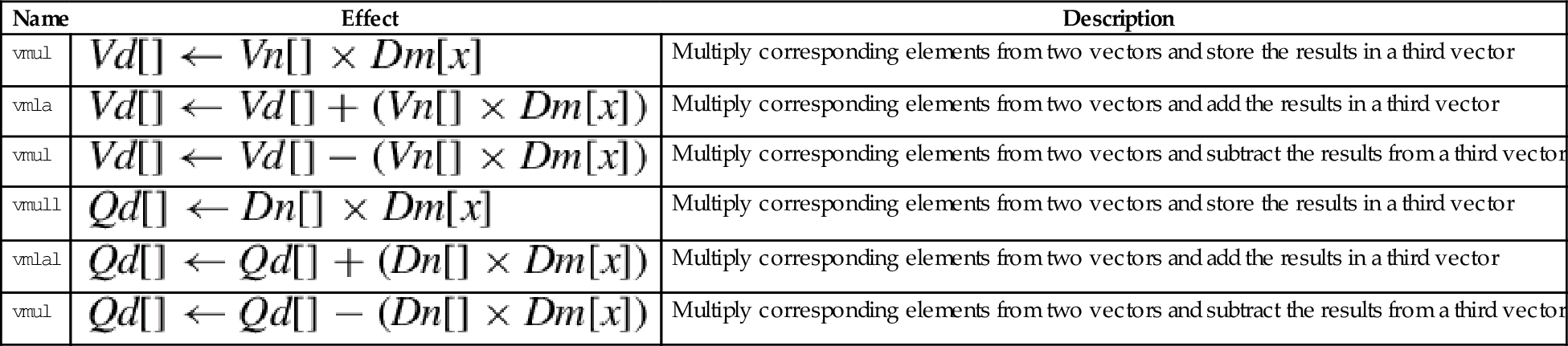

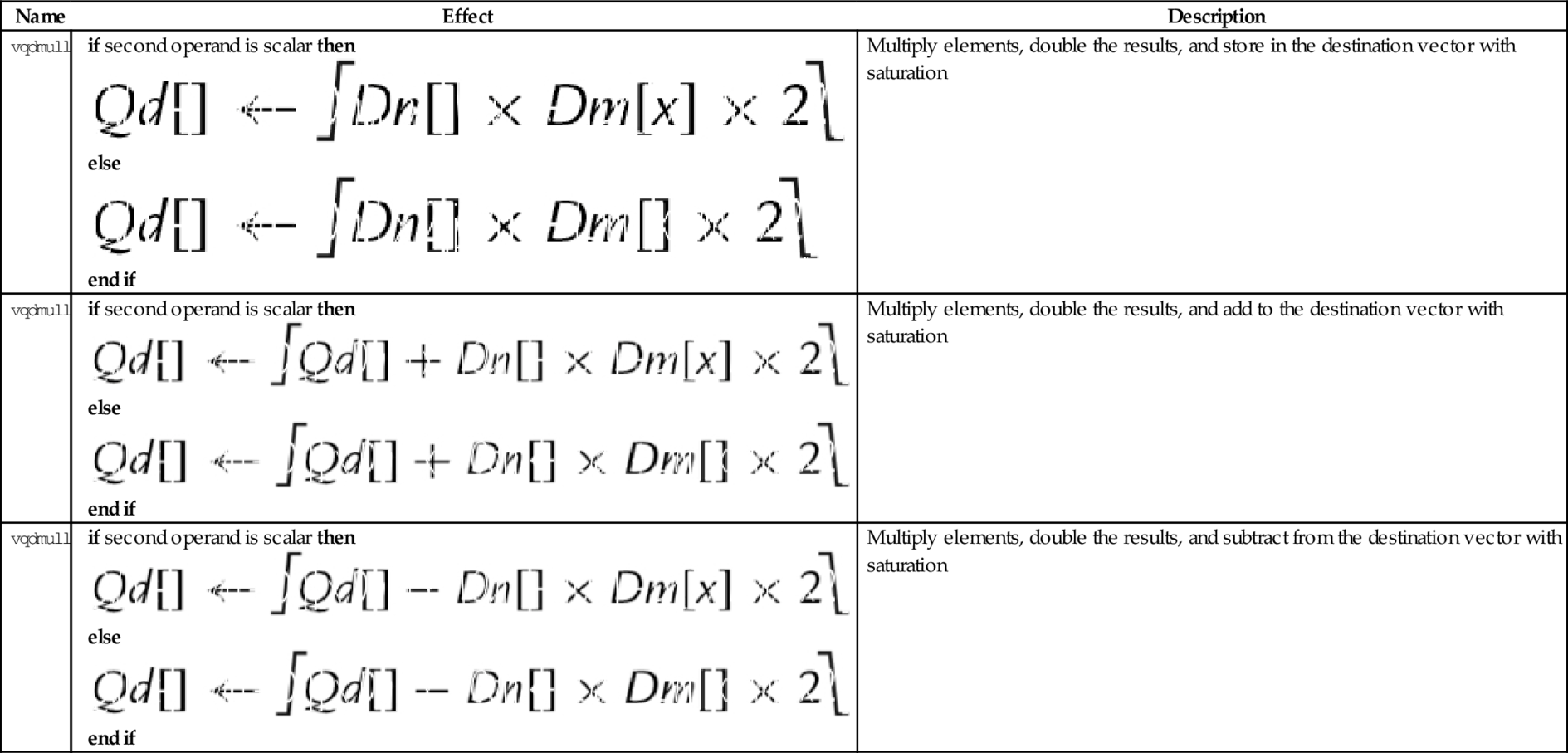

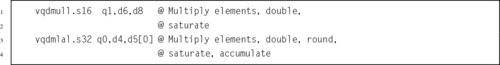

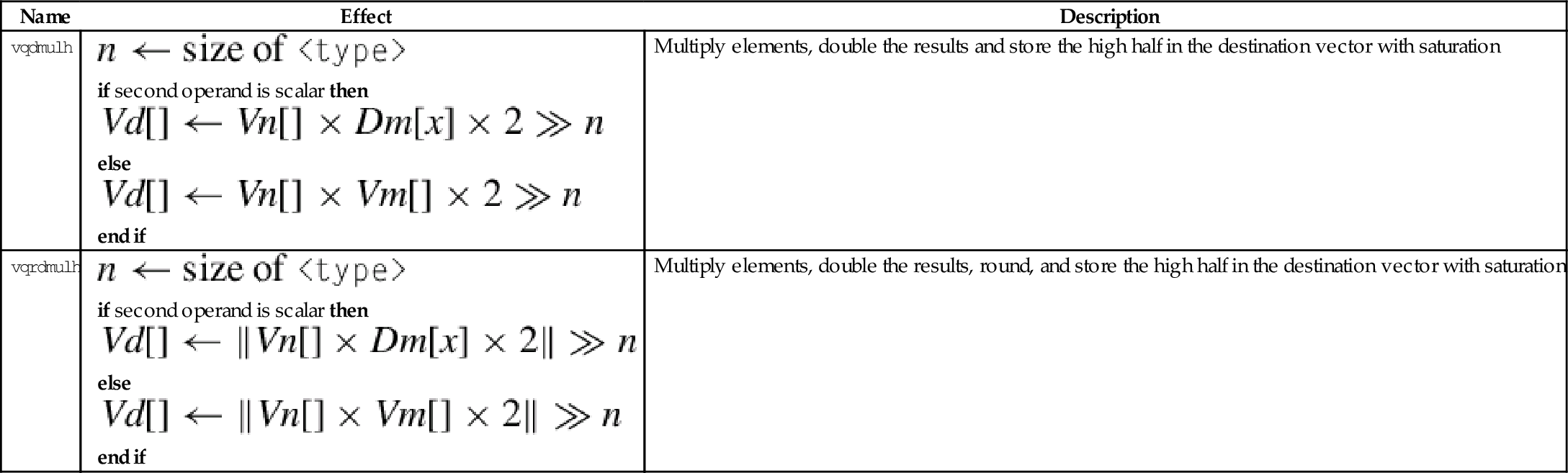

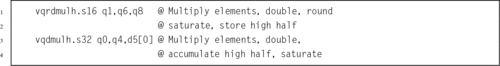

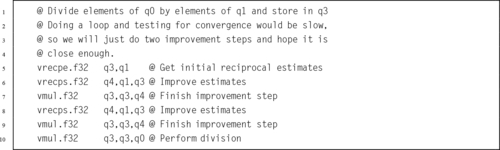

10.10 Multiplication and Division

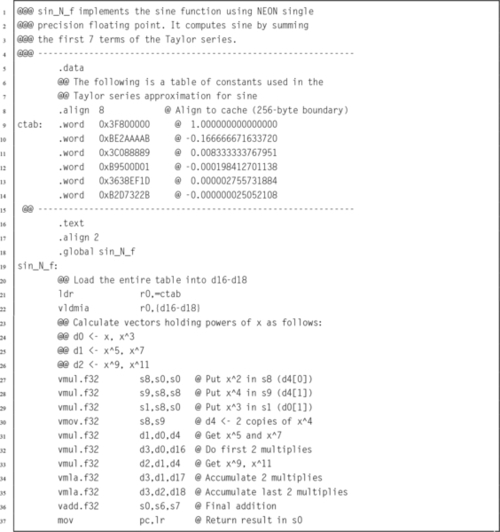

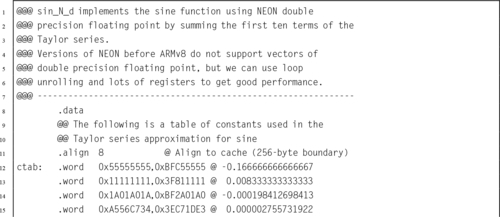

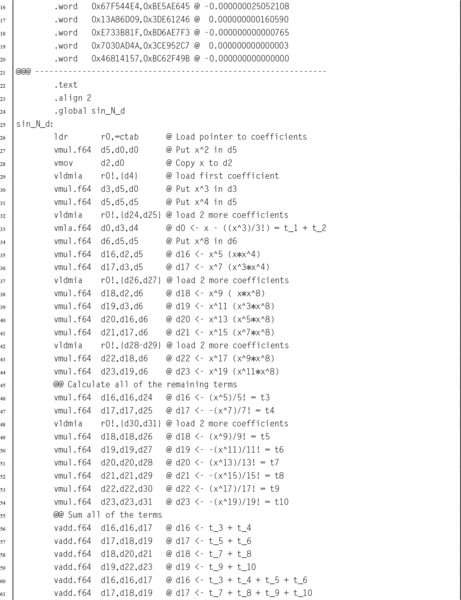

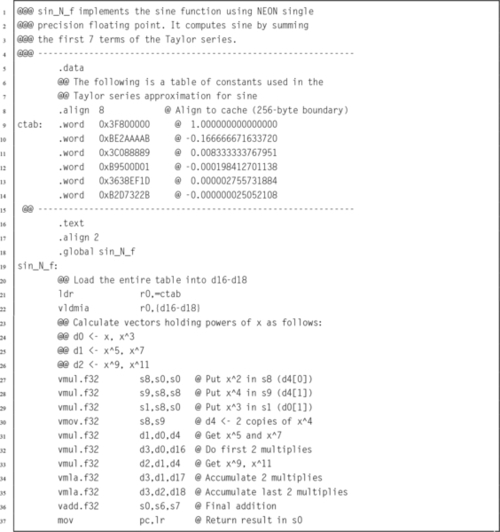

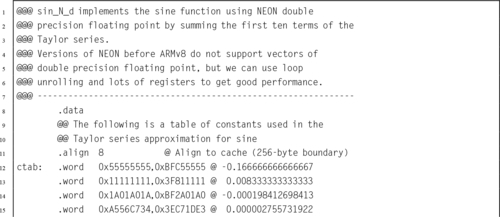

10.12 Performance Mathematics: A Final Look at Sine

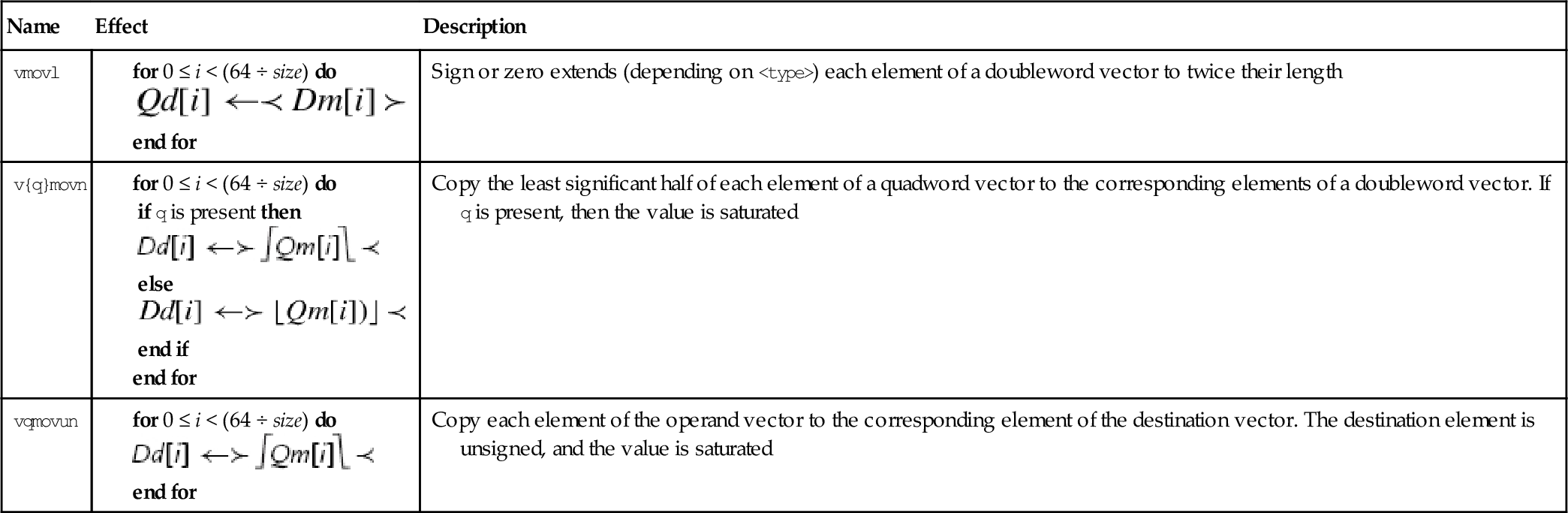

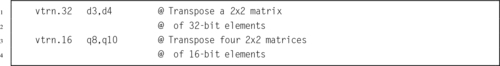

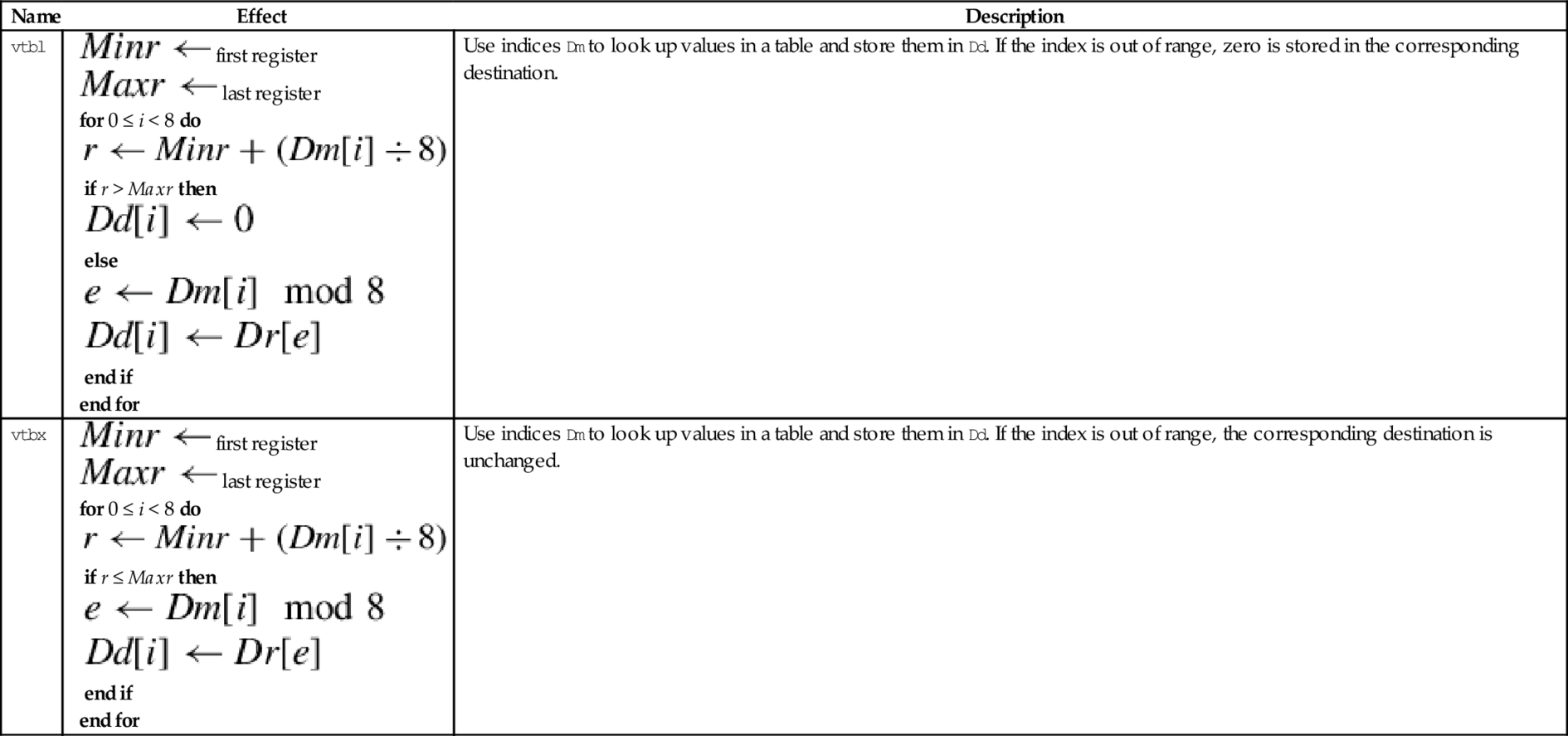

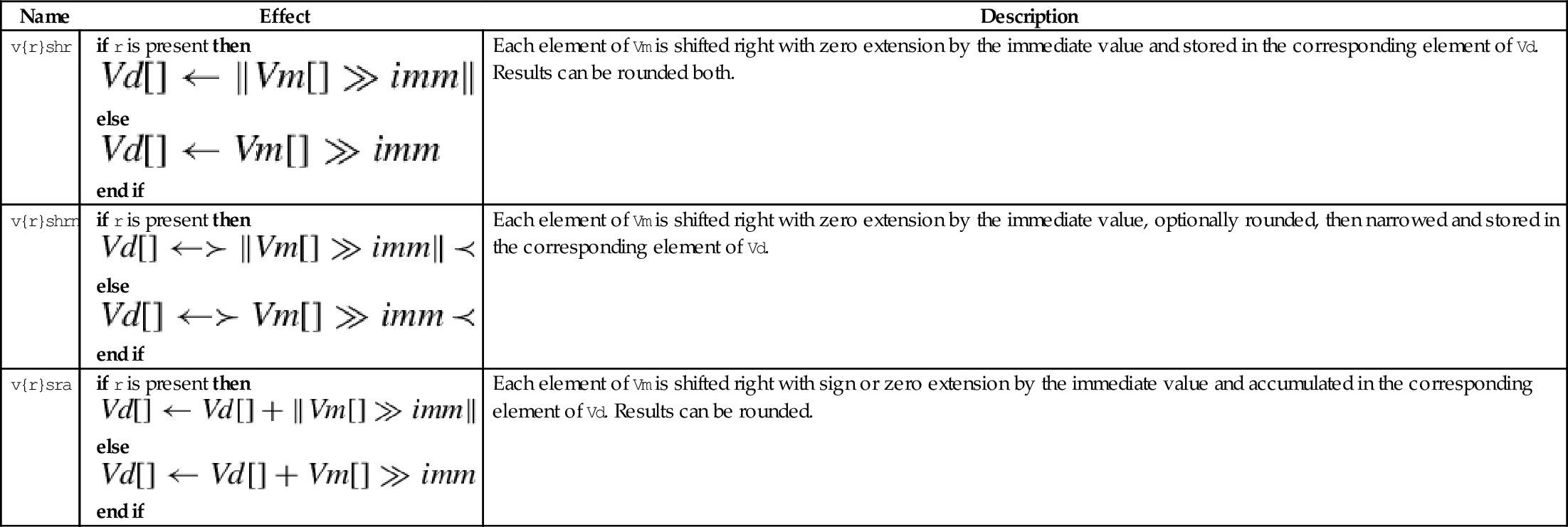

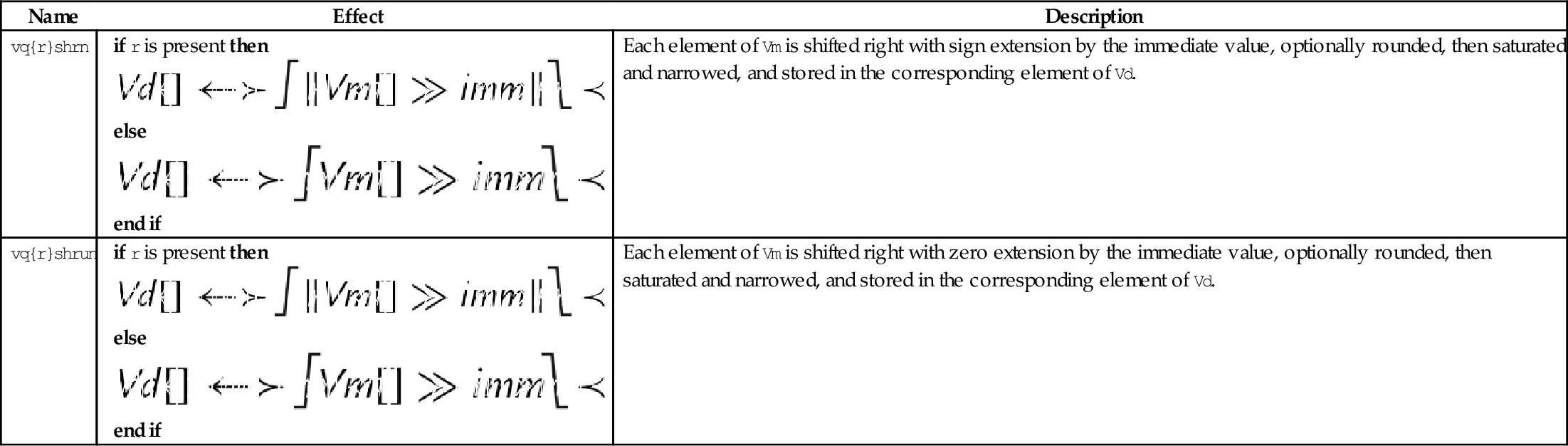

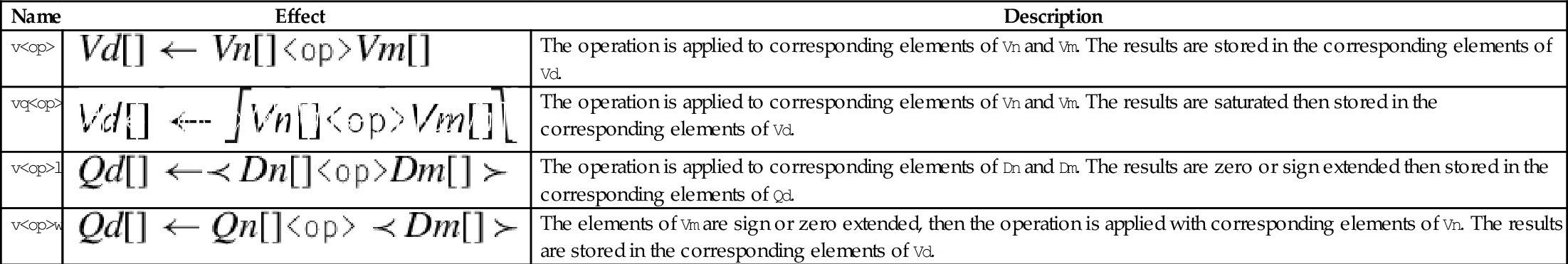

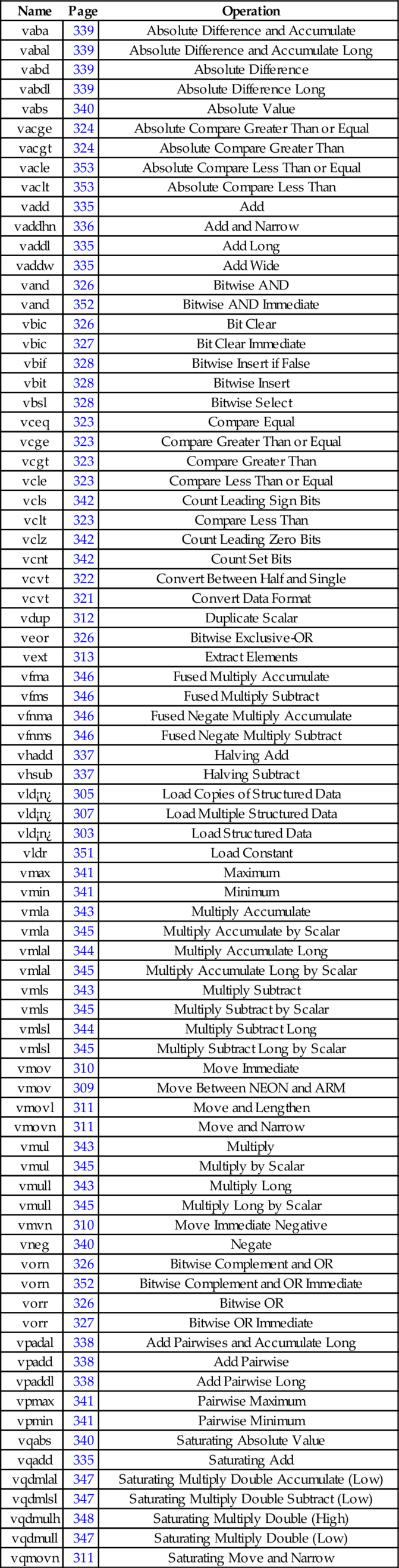

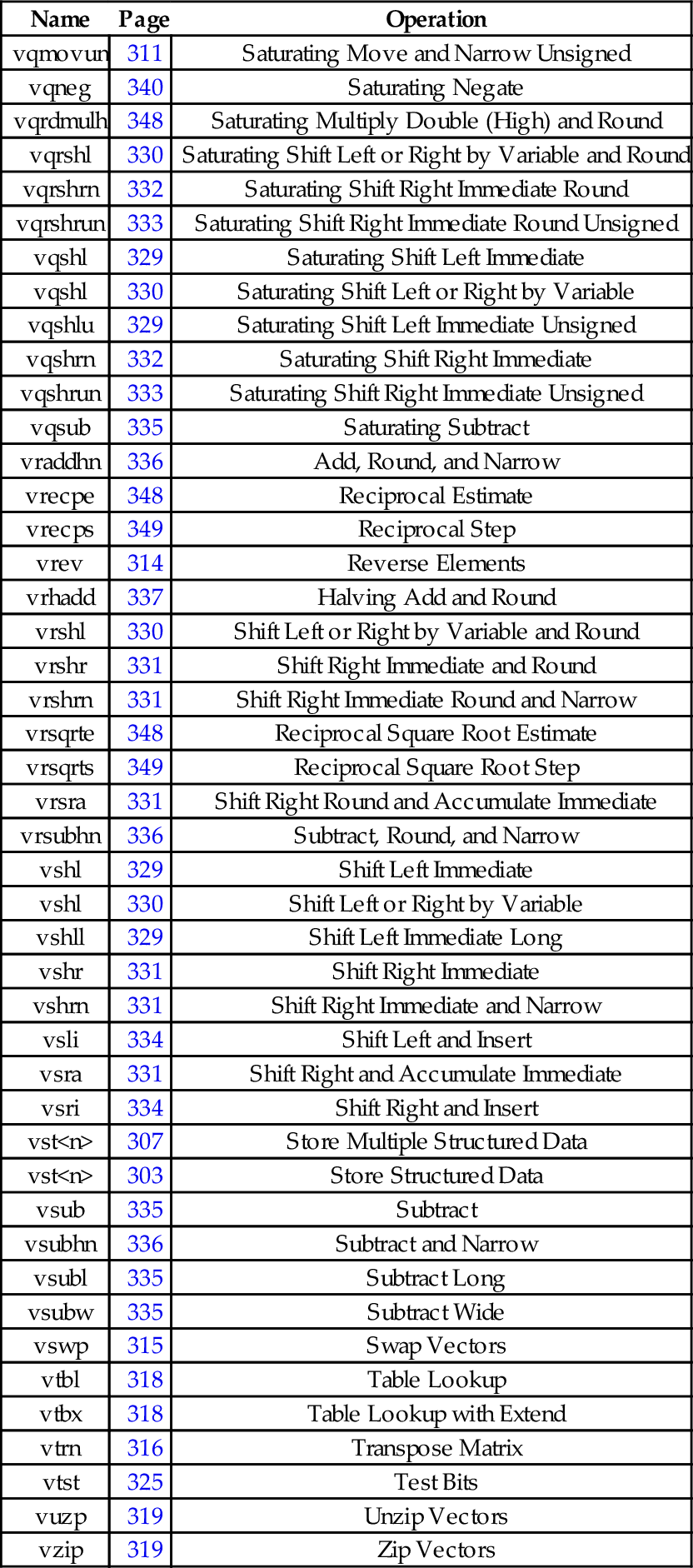

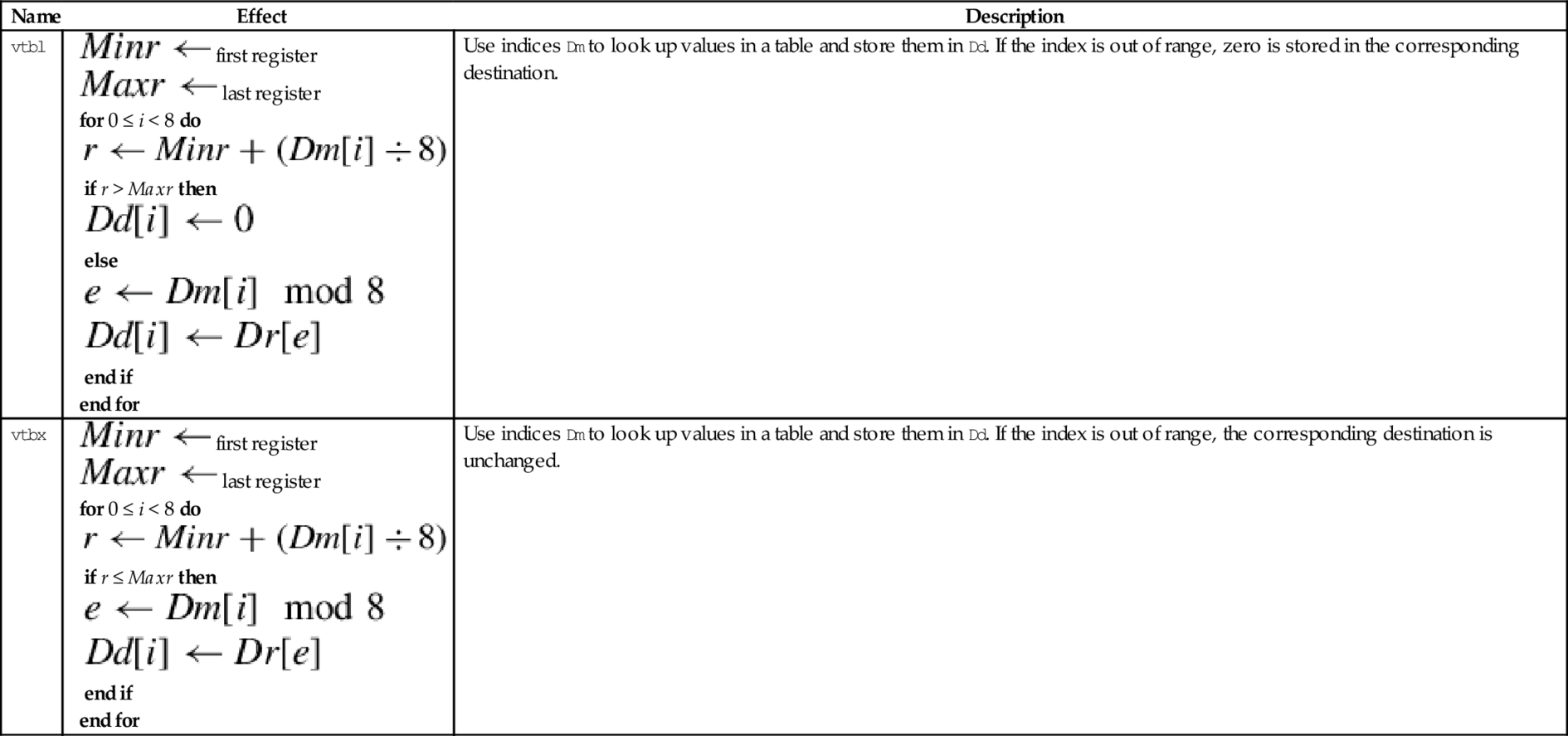

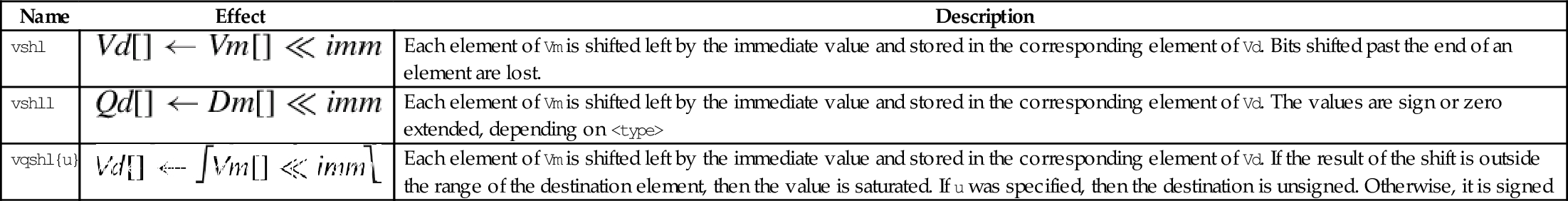

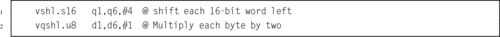

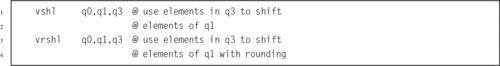

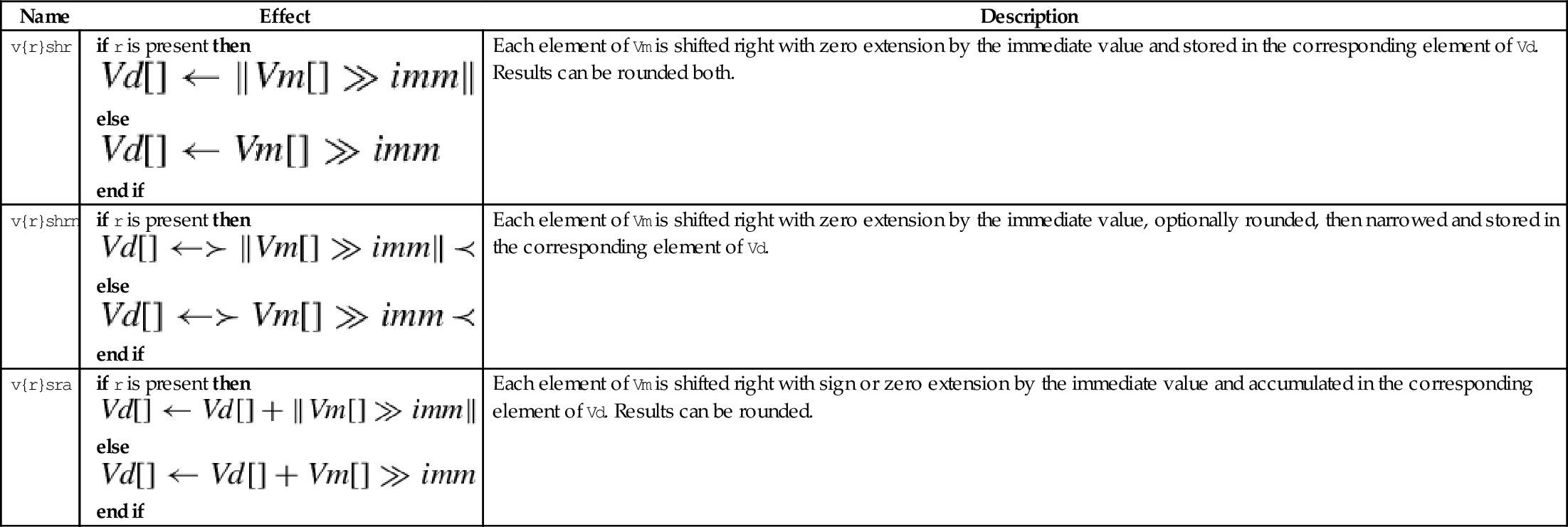

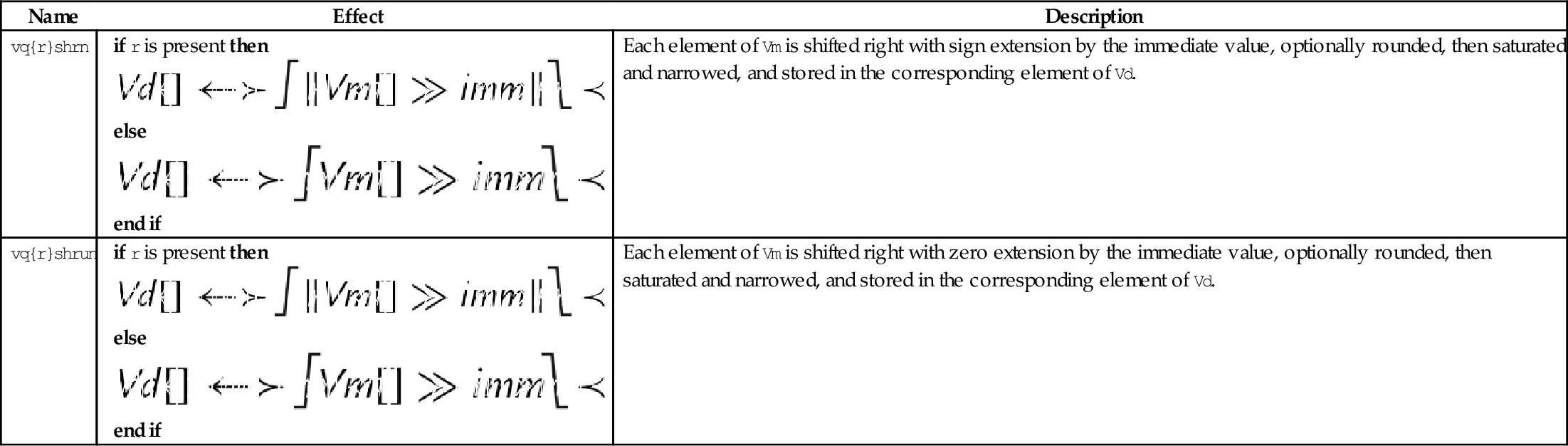

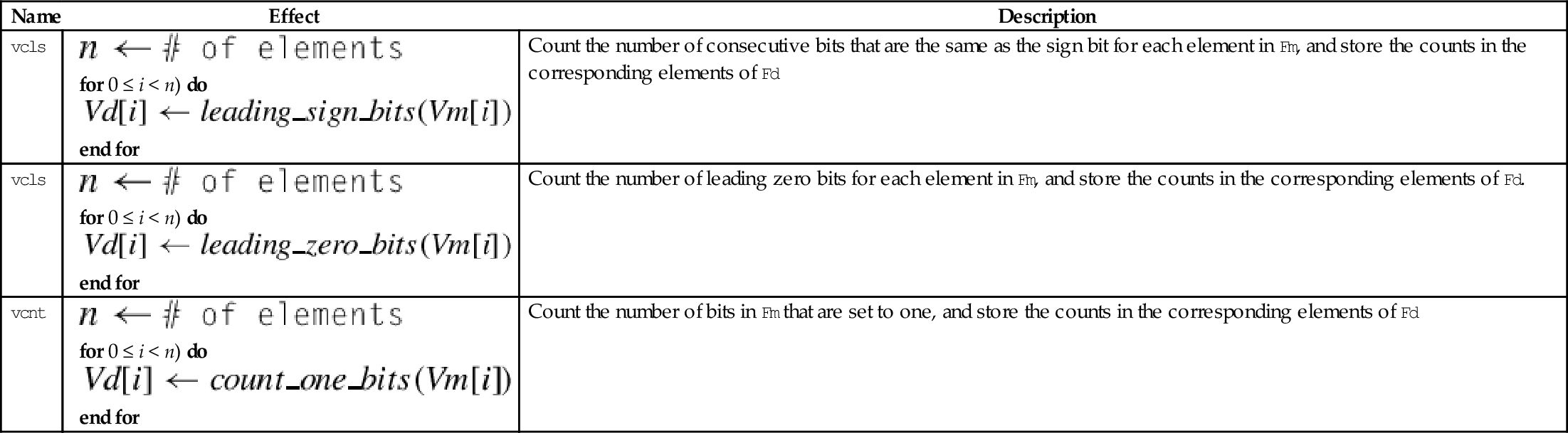

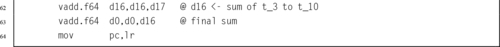

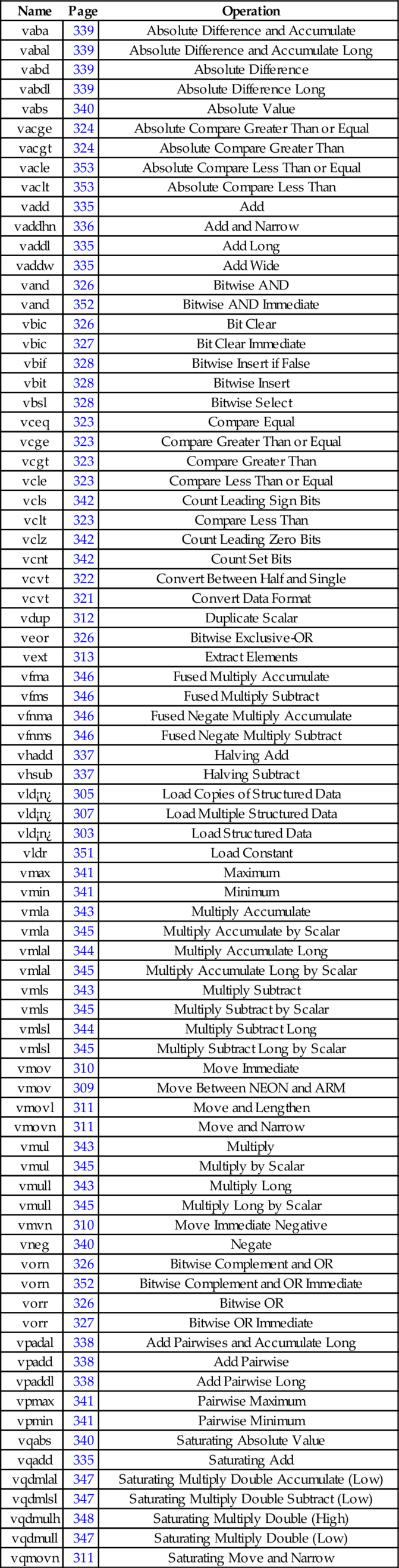

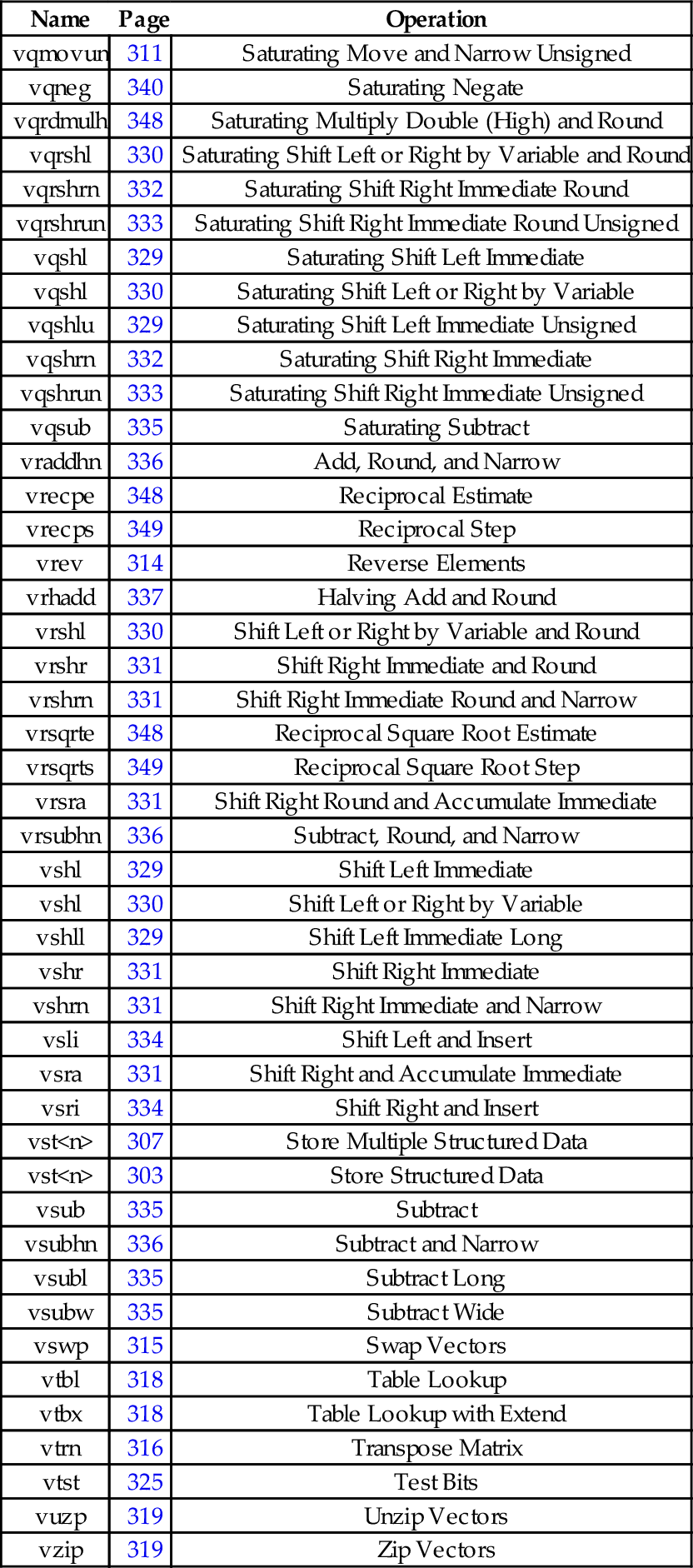

10.13 Alphabetized List of NEON Instructions

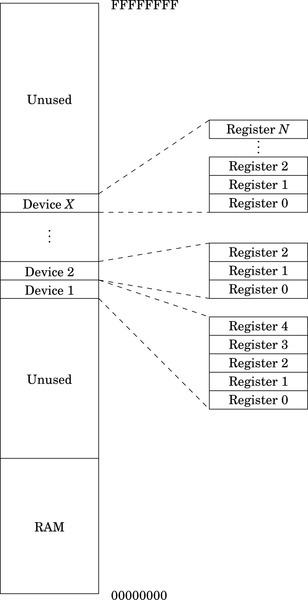

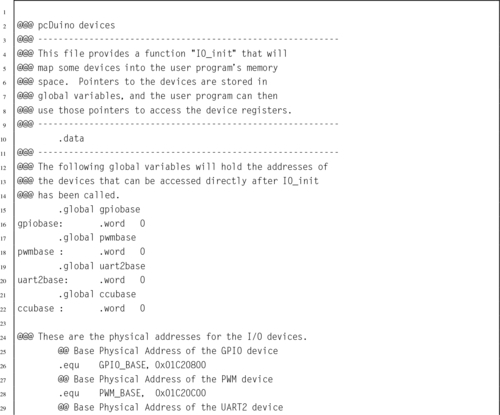

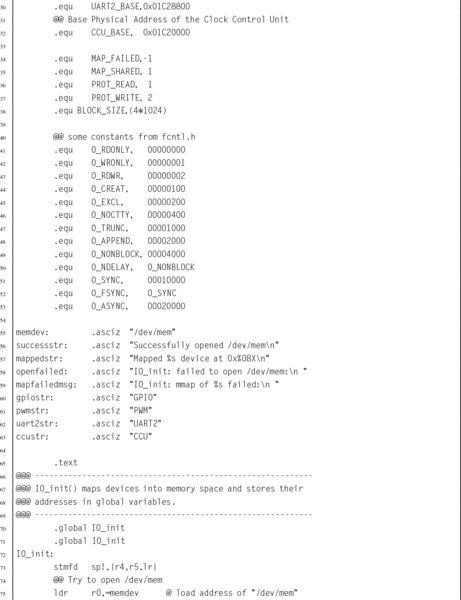

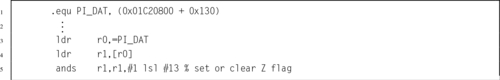

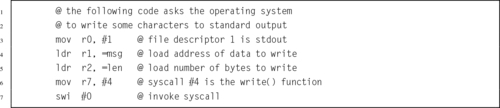

11.1 Accessing Devices Directly Under Linux

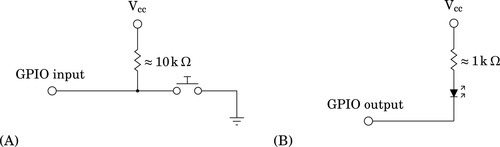

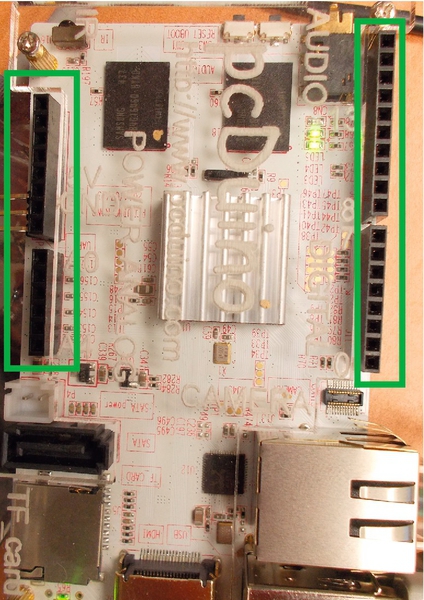

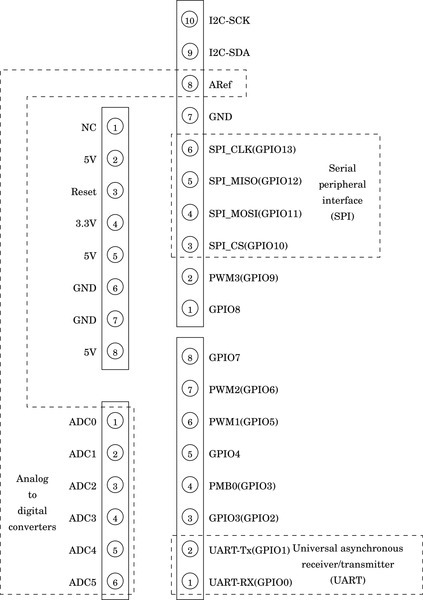

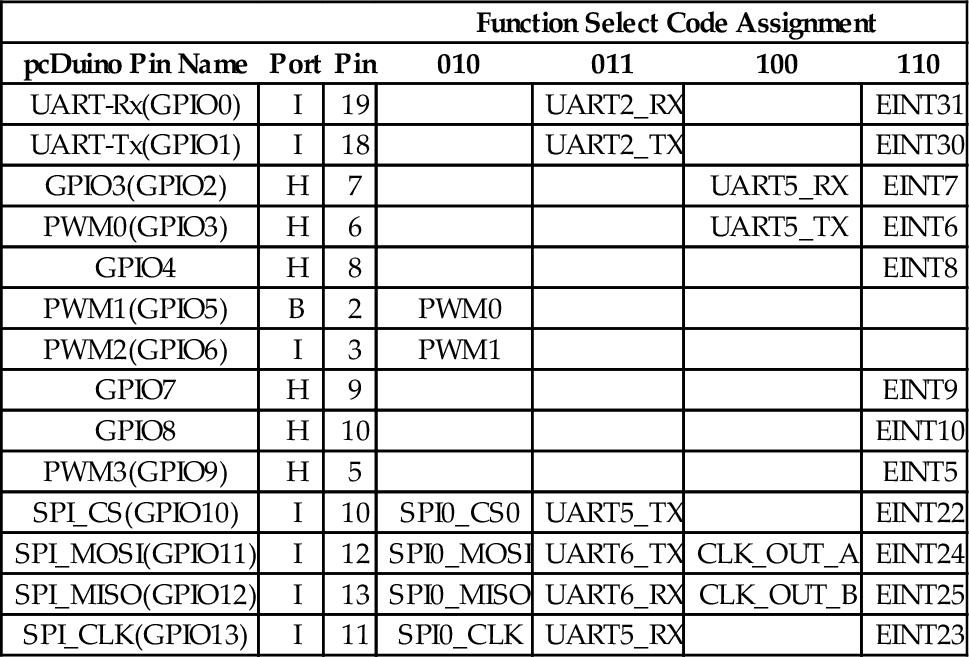

11.2 General Purpose Digital Input/Output

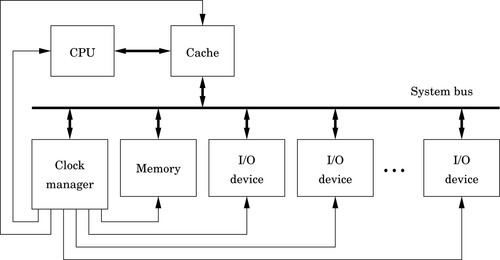

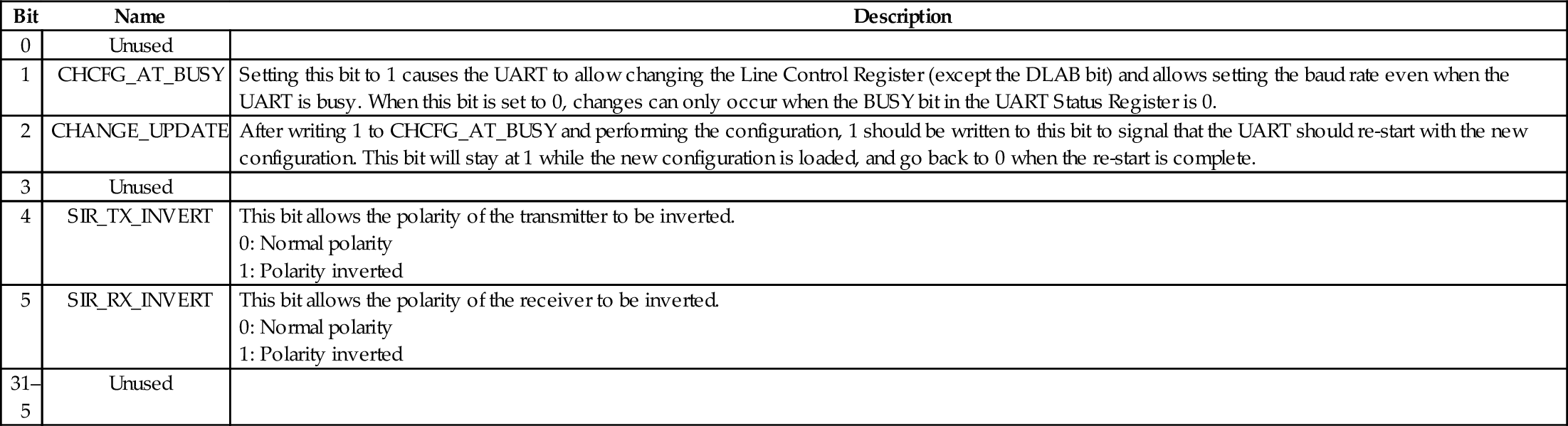

Chapter 13: Common System Devices

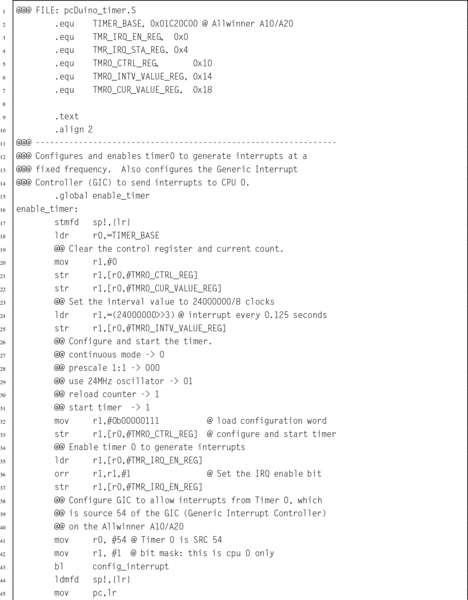

Chapter 14: Running Without an Operating System

Newnes is an imprint of Elsevier

The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford OX5 1GB, UK

50 Hampshire Street, 5th Floor, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA

Copyright © 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-12-803698-3

For information on all Newnes publications visit our website at https://www.elsevier.com/

Publisher: Joe Hayton

Acquisition Editor: Tim Pitts

Editorial Project Manager: Charlotte Kent

Production Project Manager: Julie-Ann Stansfield

Designer: Mark Rogers

Typeset by SPi Global, India

Table 1.1 Values represented by two bits 9

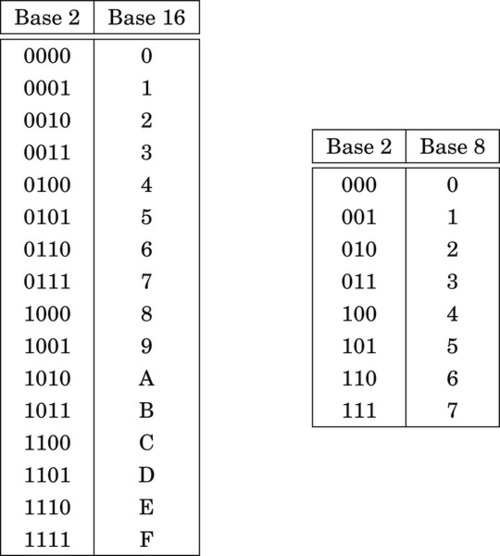

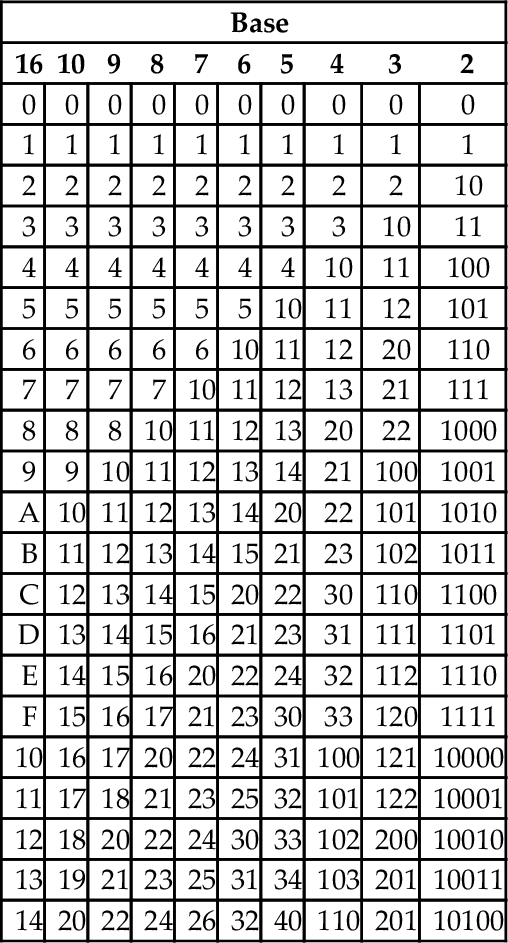

Table 1.2 The first 21 integers (starting with 0) in various bases 10

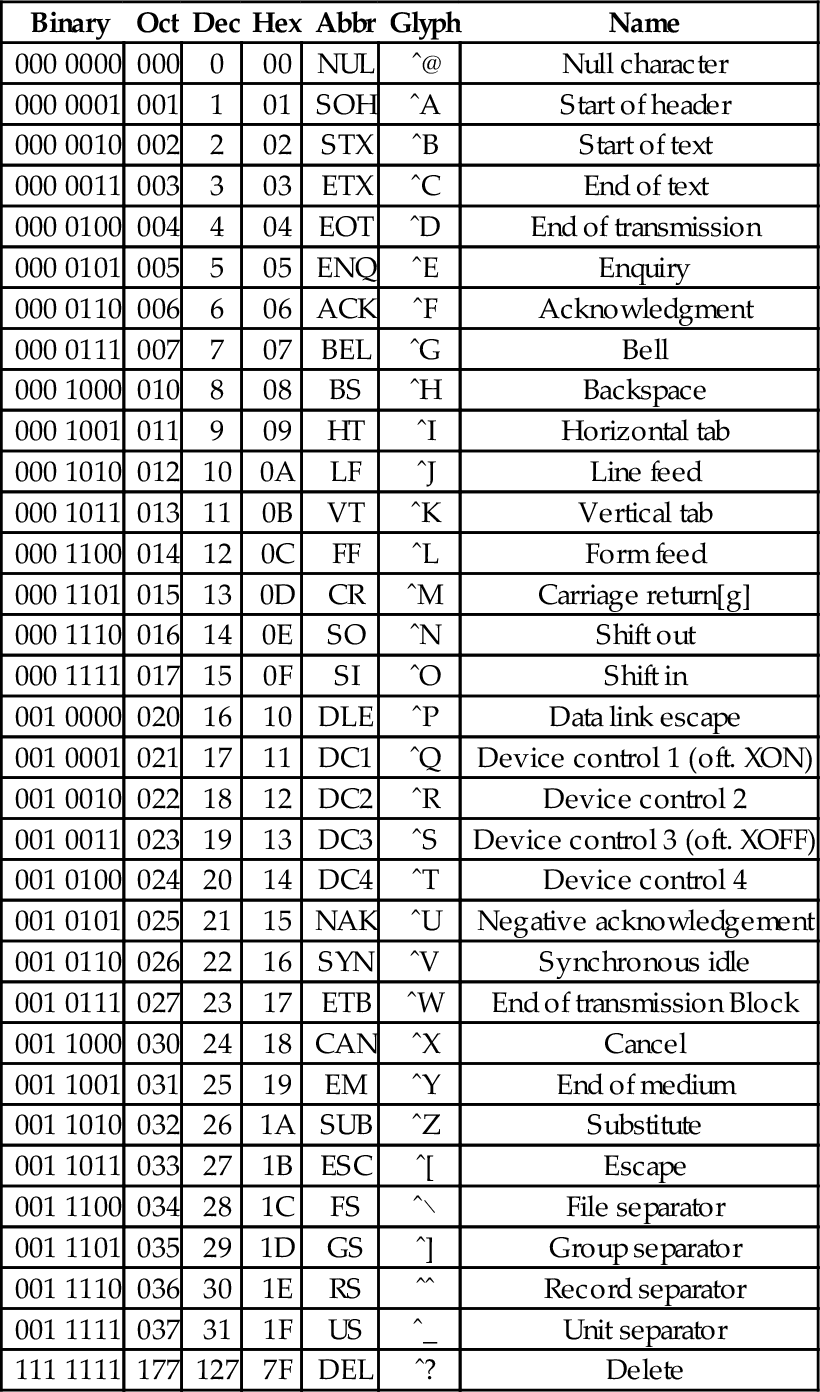

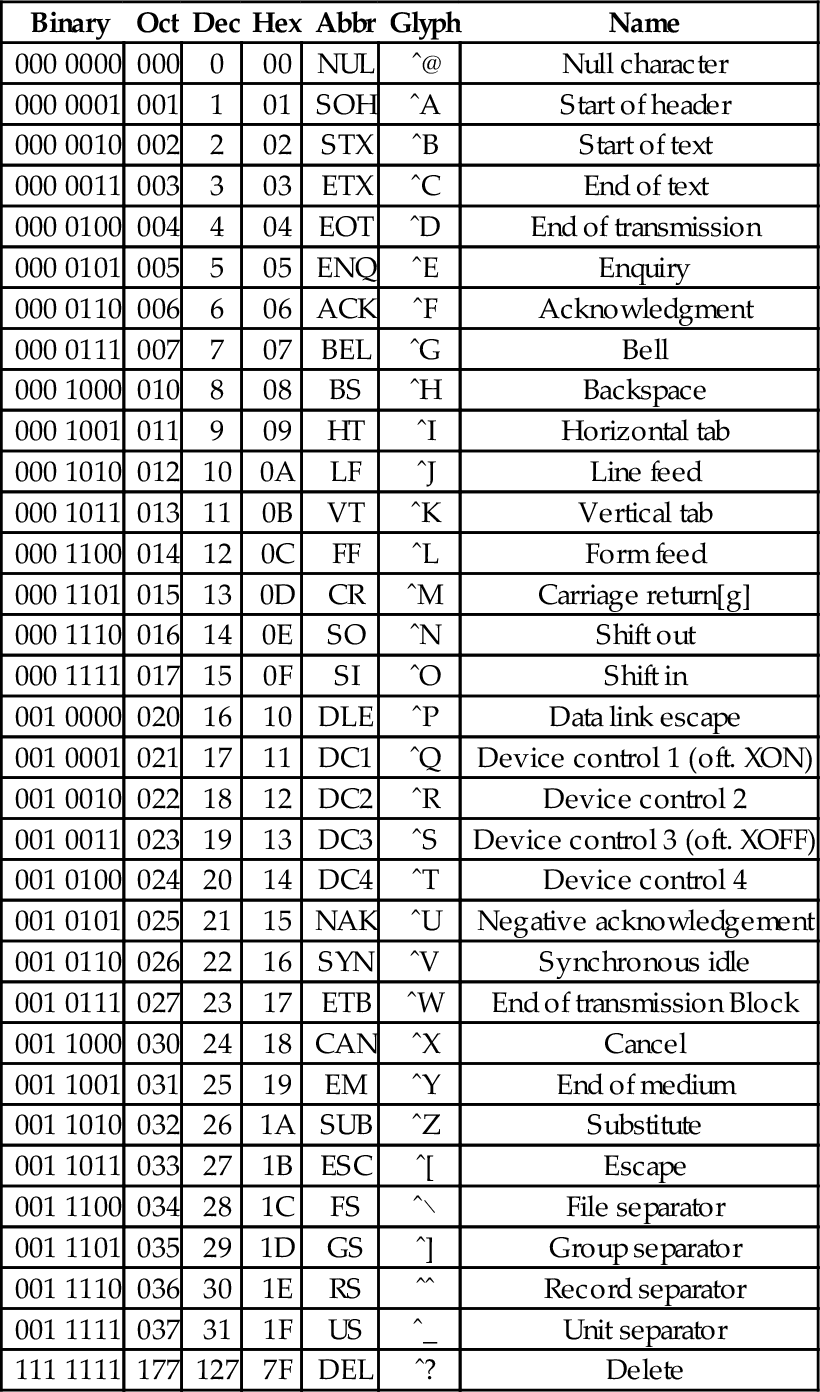

Table 1.3 The ASCII control characters 21

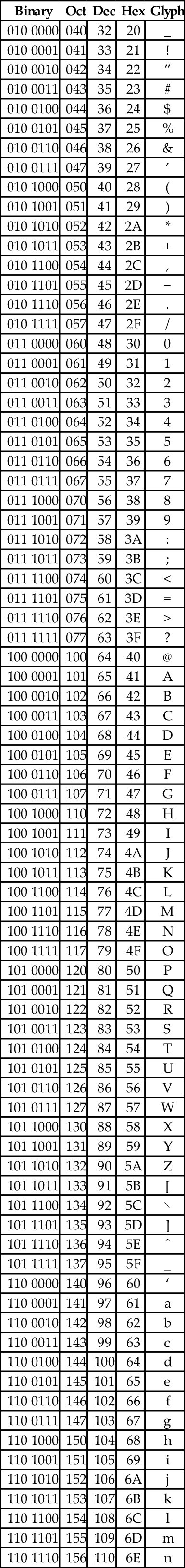

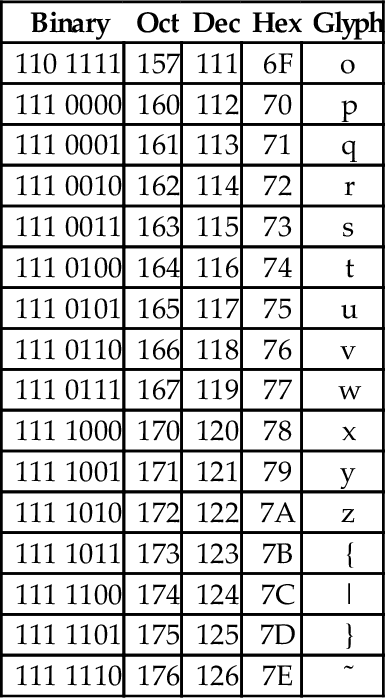

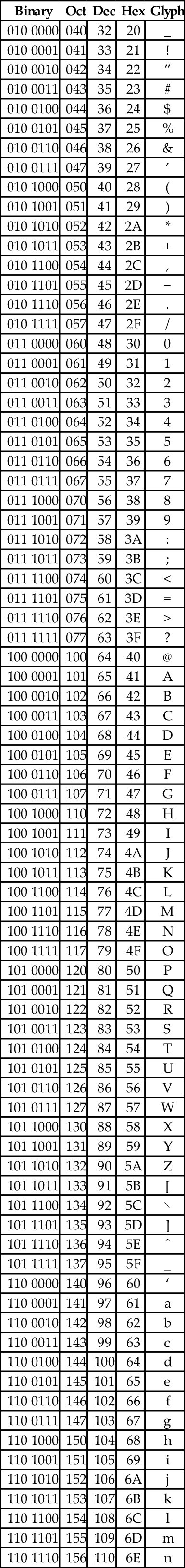

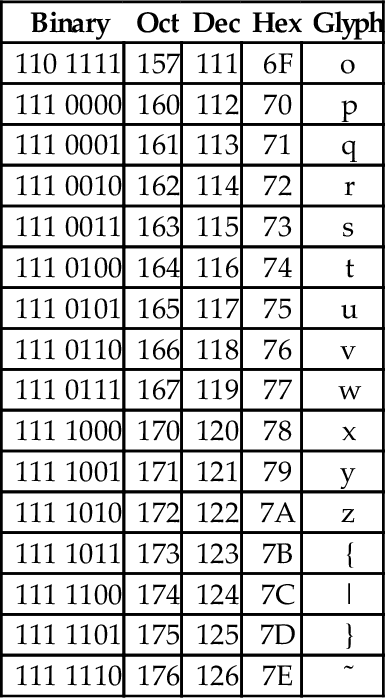

Table 1.4 The ASCII printable characters 22

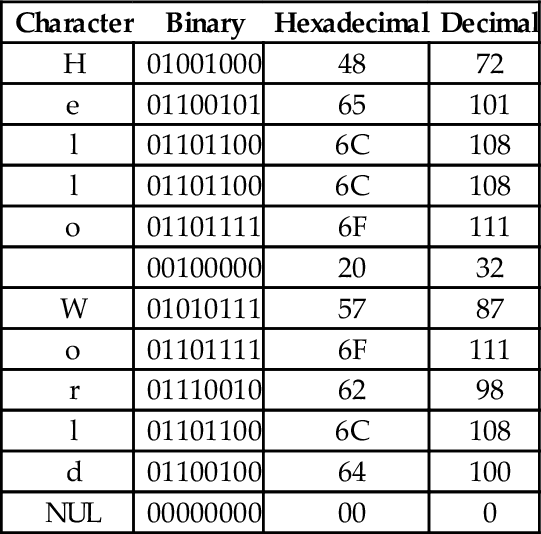

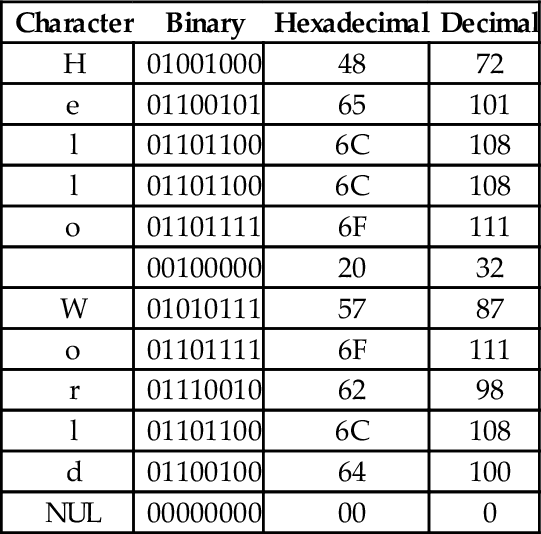

Table 1.5 Binary equivalents for each character in “Hello World” 23

Table 1.6 Binary, hexadecimal, and decimal equivalents for each character in “Hello World” 24

Table 1.7 Interpreting a hexadecimal string as ASCII 24

Table 1.8 Variations of the ISO 8859 standard 25

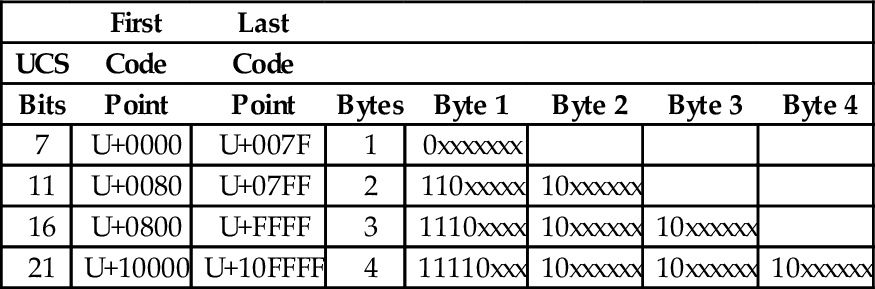

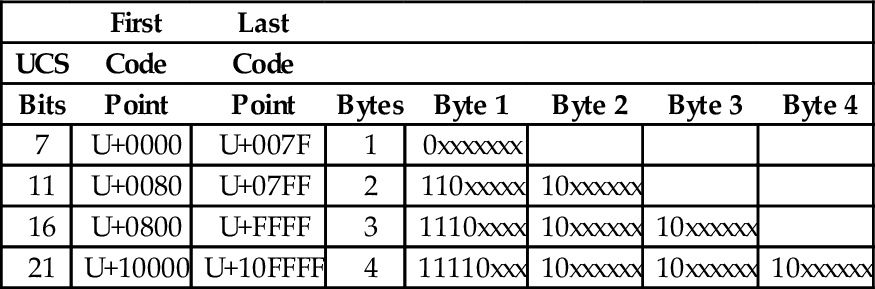

Table 1.9 UTF-8 encoding of the ISO/IEC 10646 code points 27

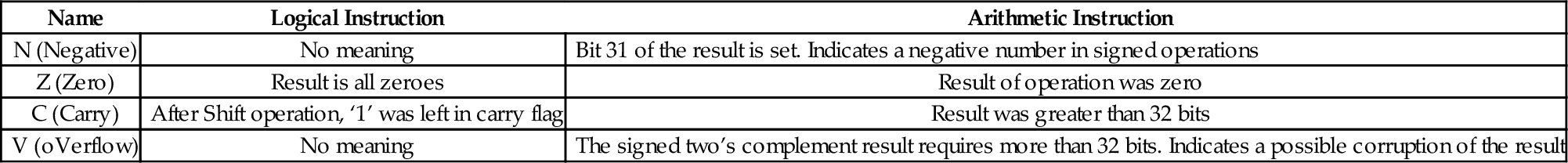

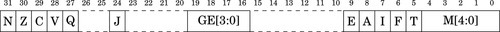

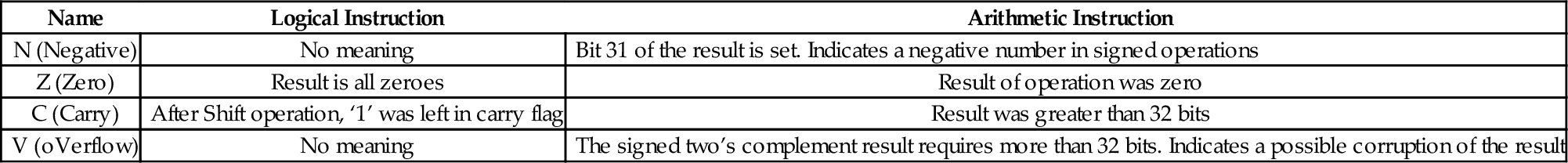

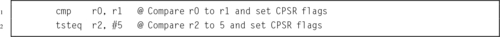

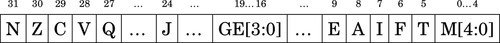

Table 3.1 Flag bits in the CPSR register 58

Table 3.2 ARM condition modifiers 59

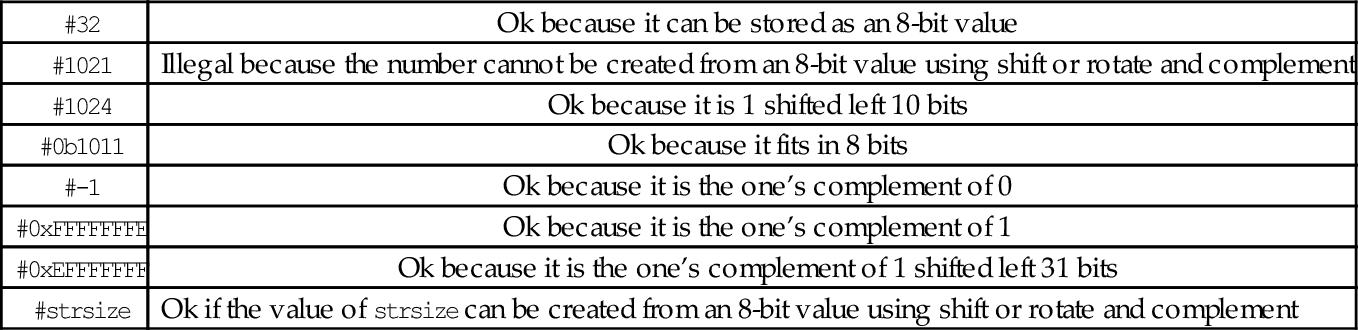

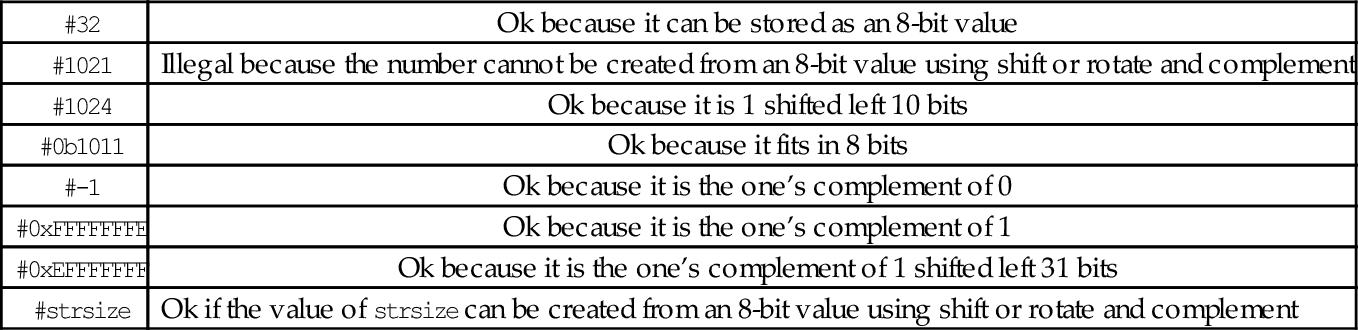

Table 3.3 Legal and illegal values for #<immediate|symbol> 60

Table 3.4 ARM addressing modes 61

Table 3.5 ARM shift and rotate operations 61

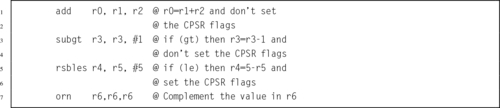

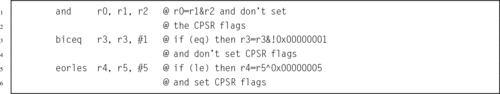

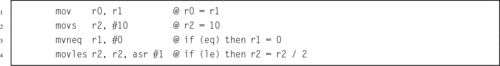

Table 4.1 Shift and rotate operations in Operand2 80

Table 4.2 Formats for Operand2 81

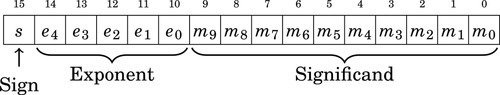

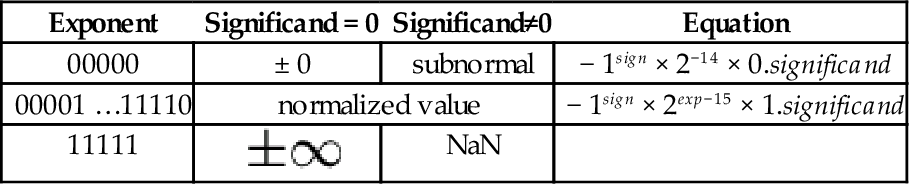

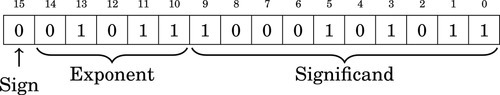

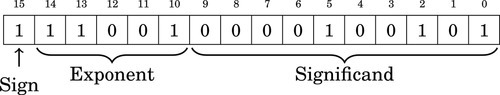

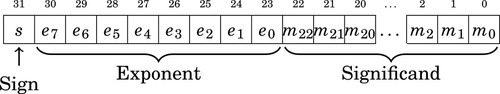

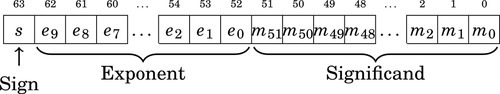

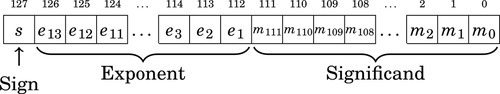

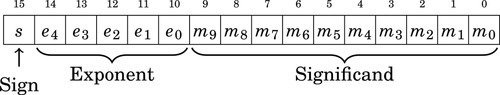

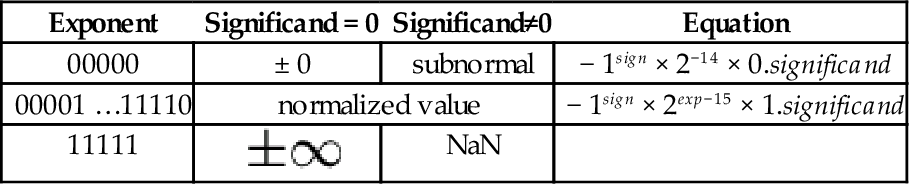

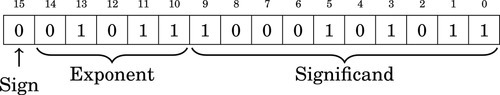

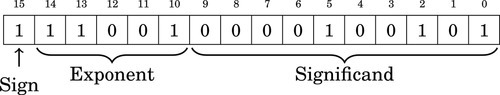

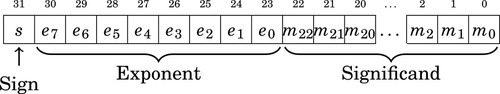

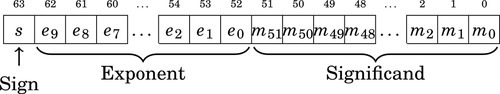

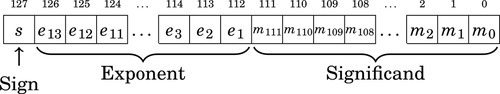

Table 8.1 Format for IEEE 754 half-precision 244

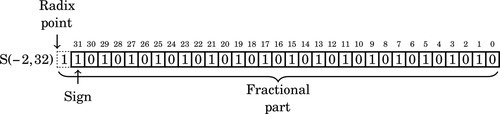

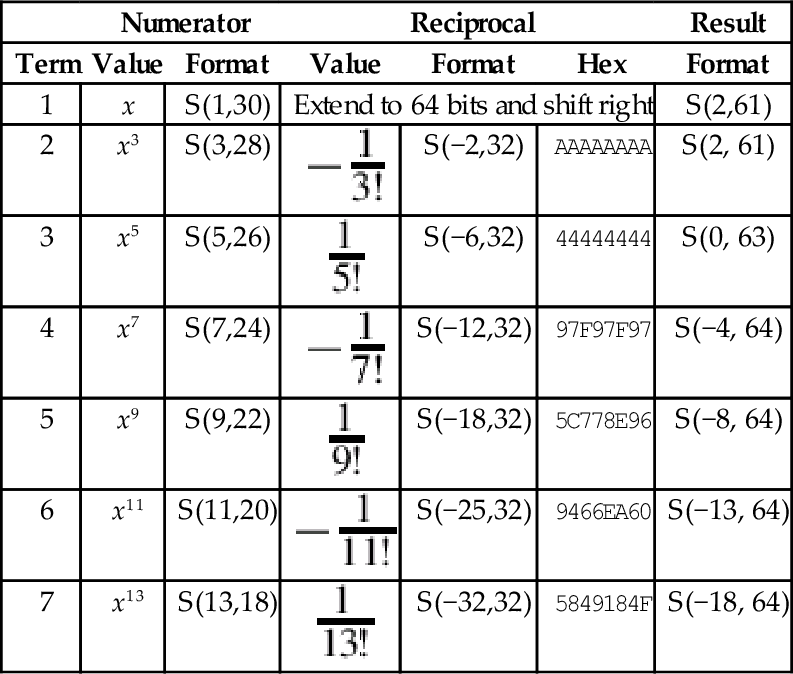

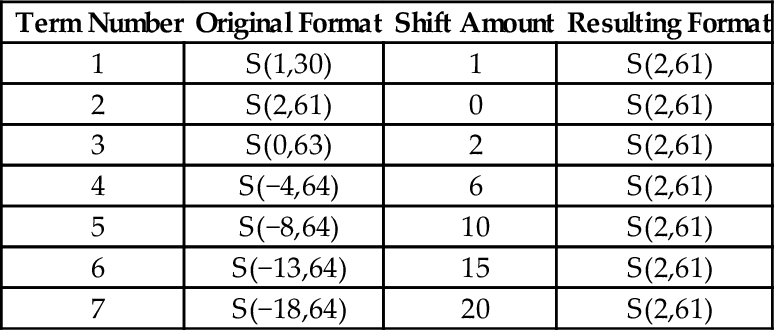

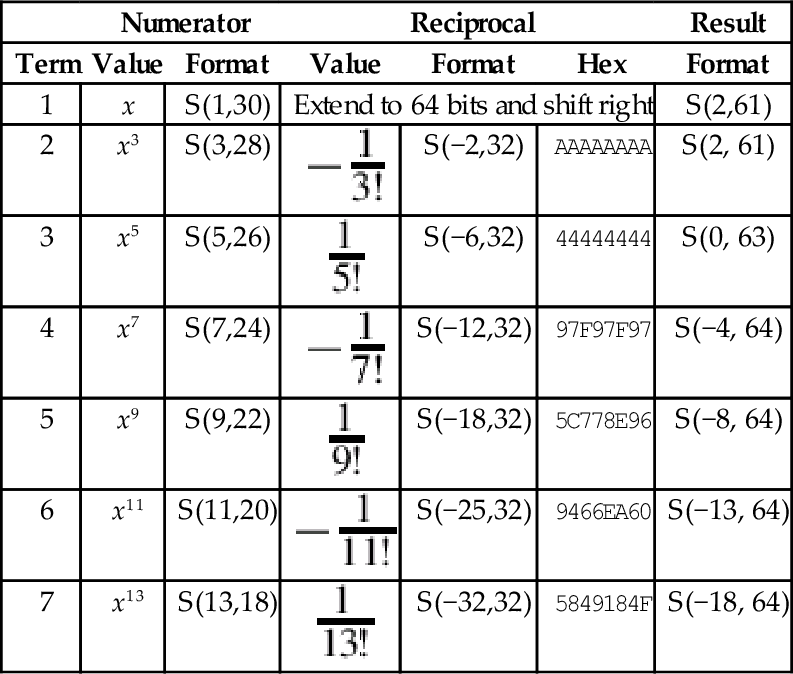

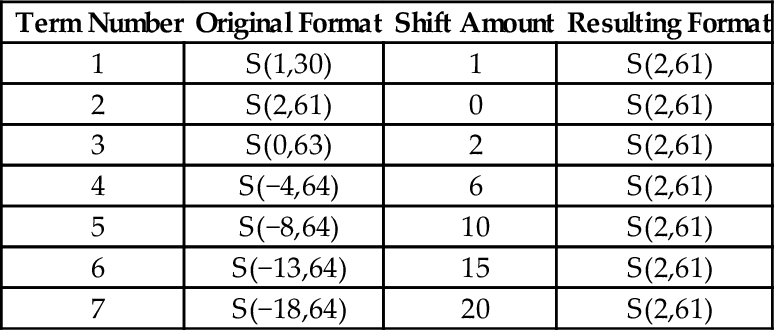

Table 8.2 Result formats for each term 252

Table 8.3 Shifts required for each term 252

Table 8.4 Performance of sine function with various implementations 259

Table 9.1 Condition code meanings for ARM and VFP 271

Table 9.2 Performance of sine function with various implementations 292

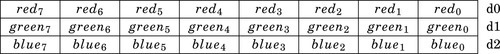

Table 10.1 Parameter combinations for loading and storing a single structure 304

Table 10.2 Parameter combinations for loading multiple structures 306

Table 10.3 Parameter combinations for loading copies of a structure 308

Table 10.4 Performance of sine function with various implementations 357

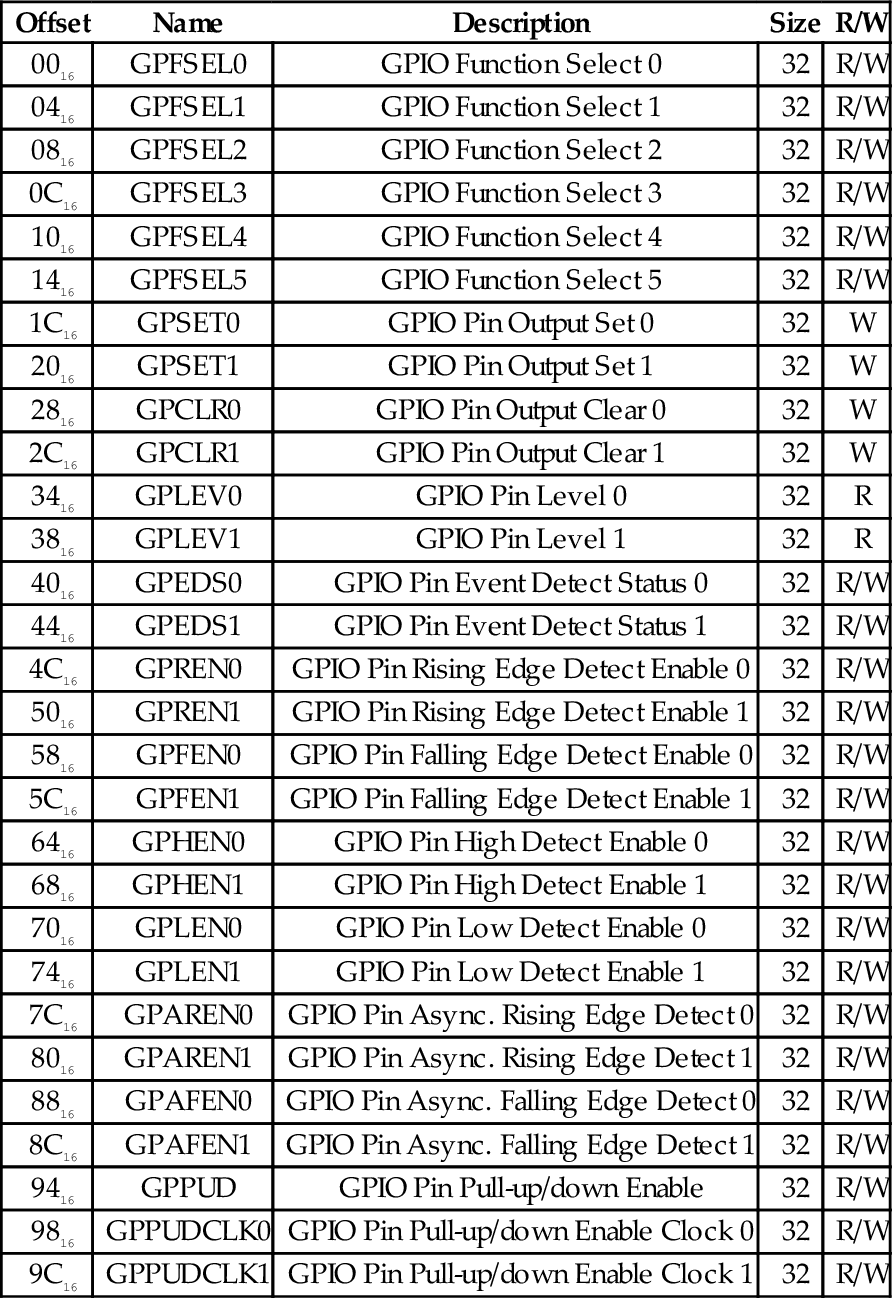

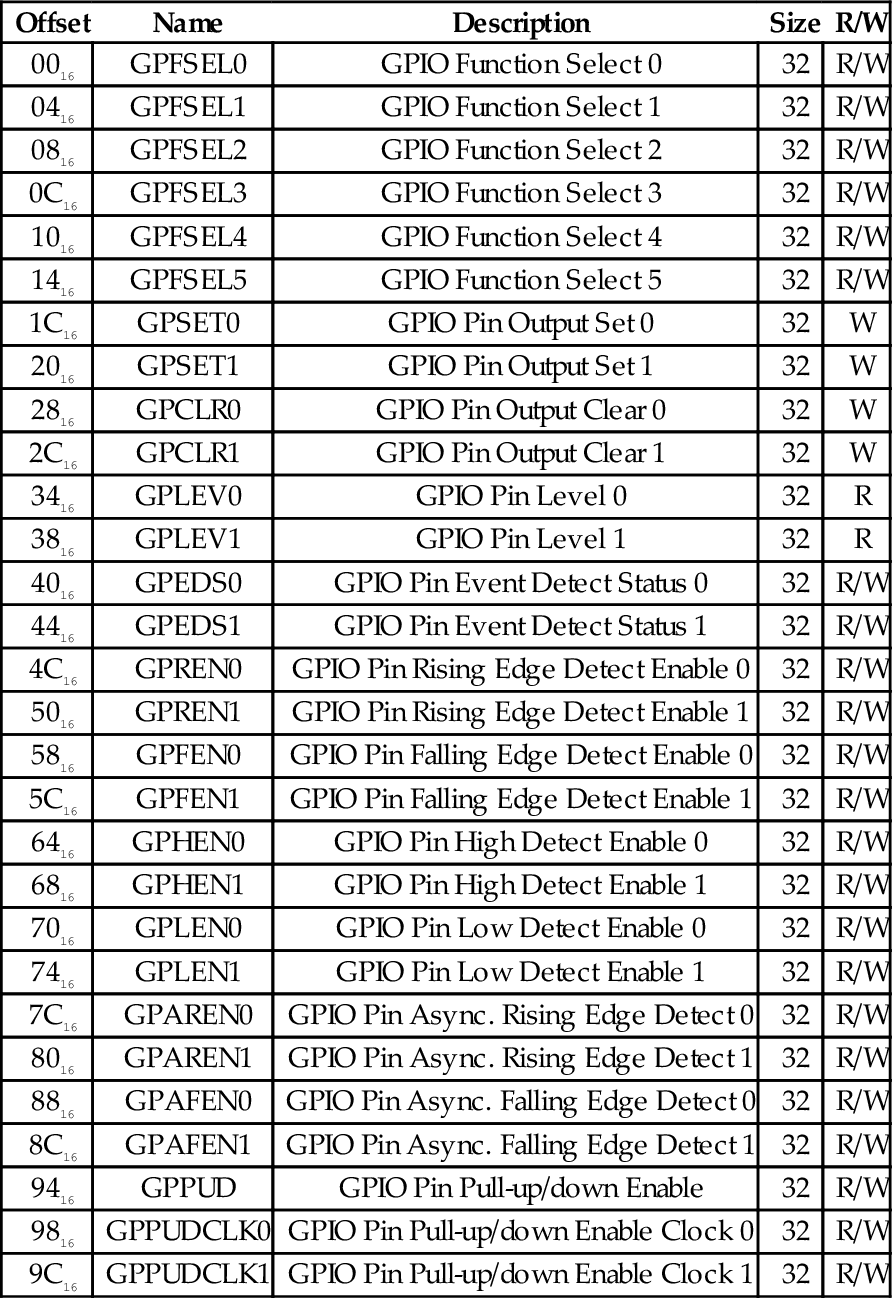

Table 11.1 Raspberry Pi GPIO register map 379

Table 11.2 GPIO pin function select bits 380

Table 11.3 GPPUD control codes 381

Table 11.4 Raspberry Pi expansion header useful alternate functions 385

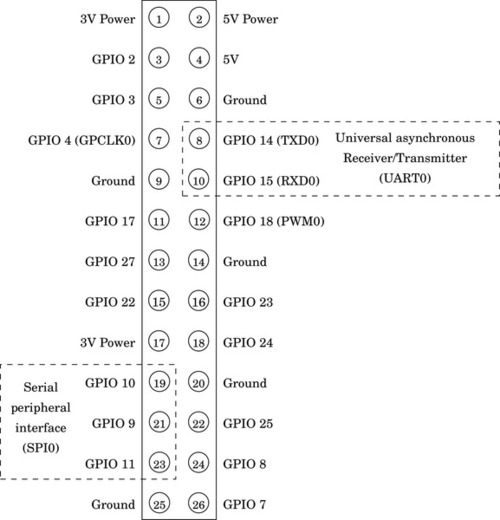

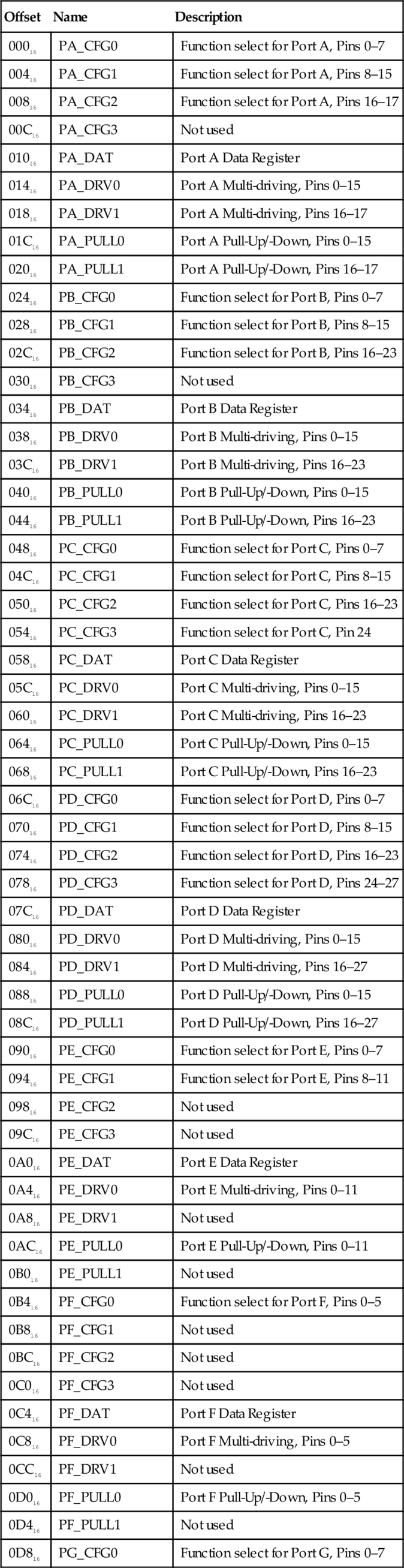

Table 11.5 Number of pins available on each of the AllWinner A10/A20 PIO ports 385

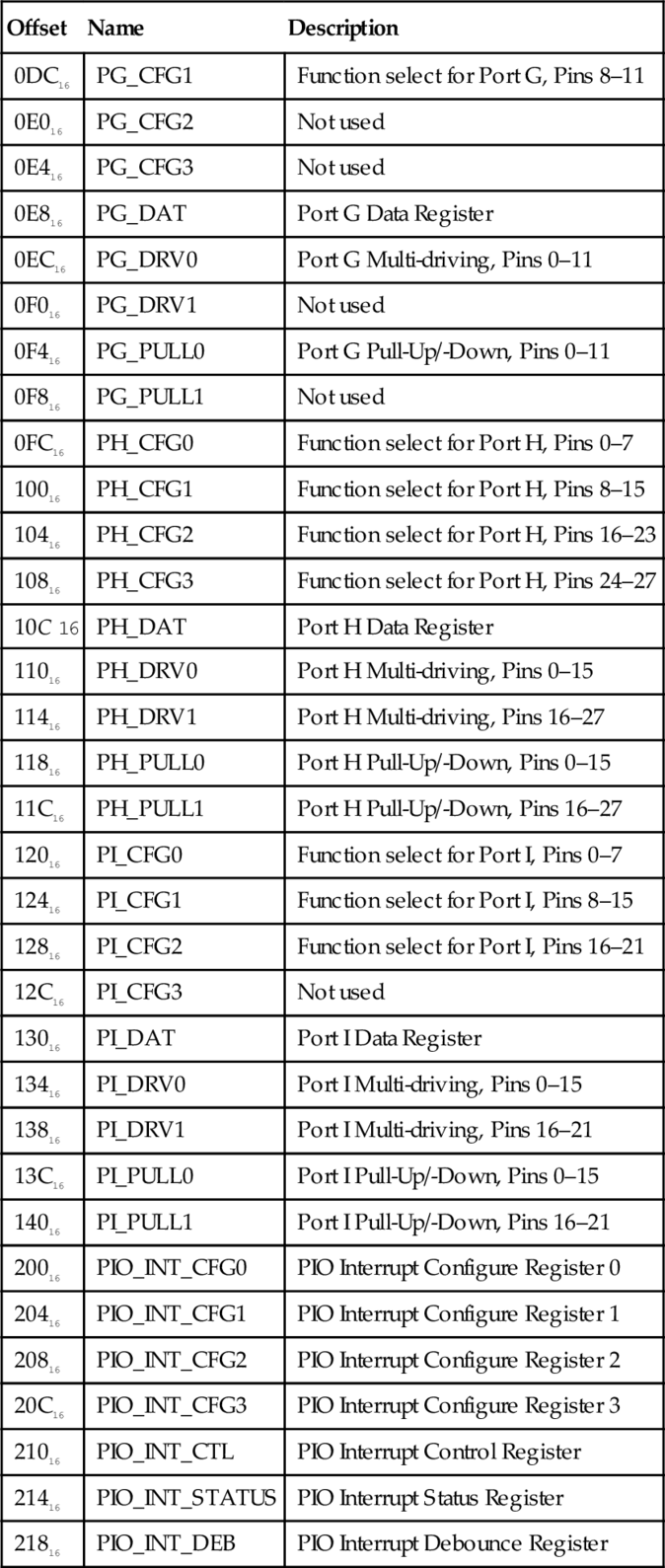

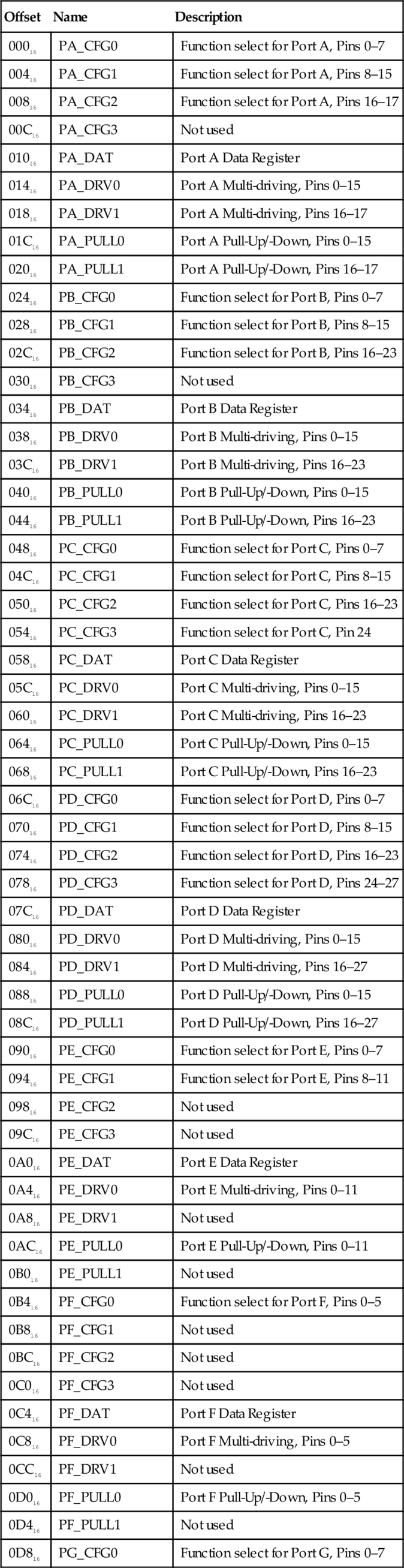

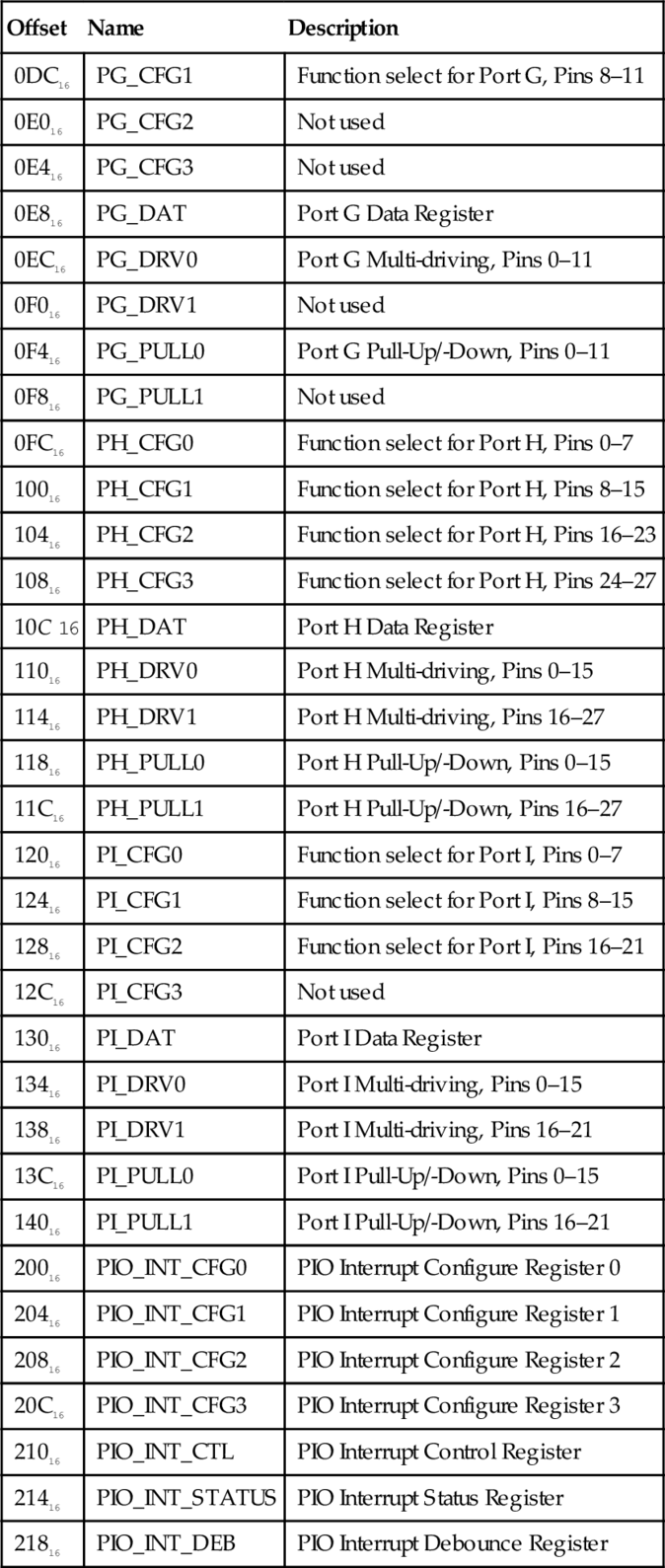

Table 11.6 Registers in the AllWinner GPIO device 386

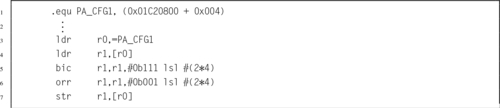

Table 11.7 Allwinner A10/A20 GPIO pin function select bits 388

Table 11.8 Pull-up and pull-down resistor control codes 389

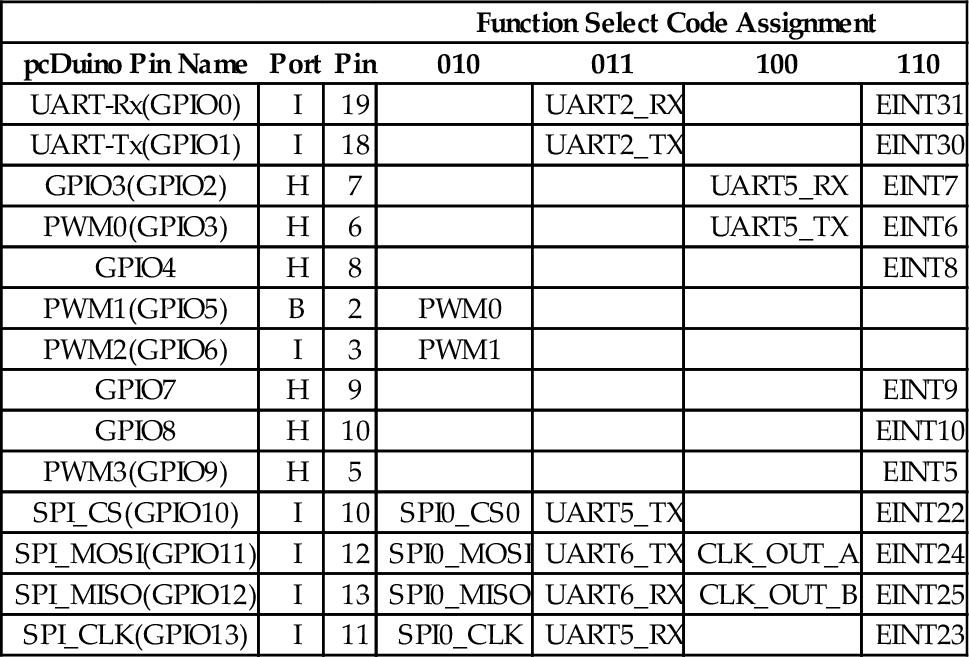

Table 11.9 pcDuino GPIO pins and function select code assignments. 392

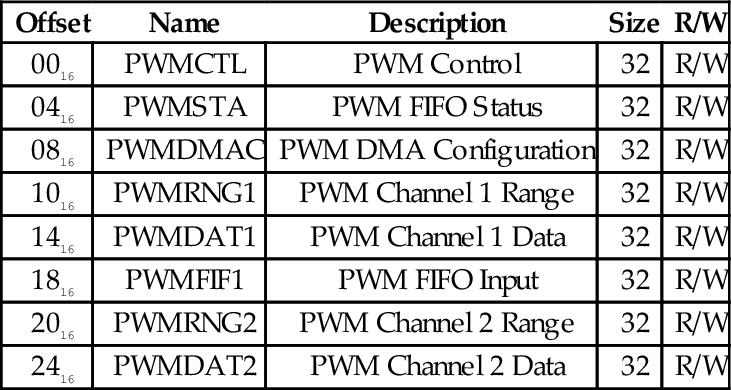

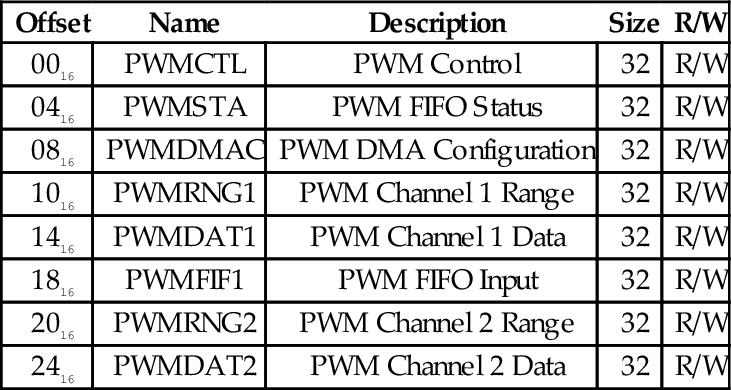

Table 12.1 Raspberry Pi PWM register map 398

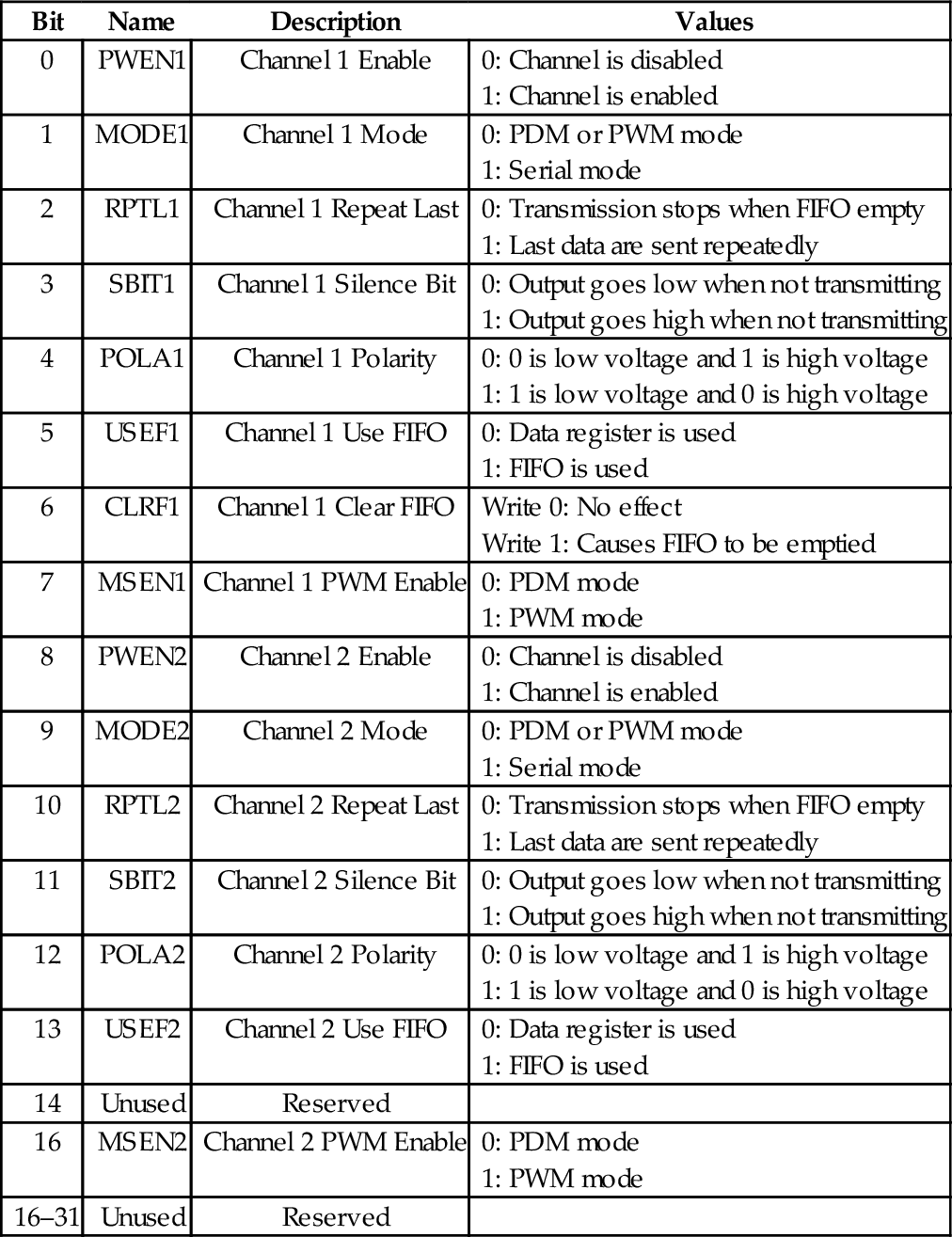

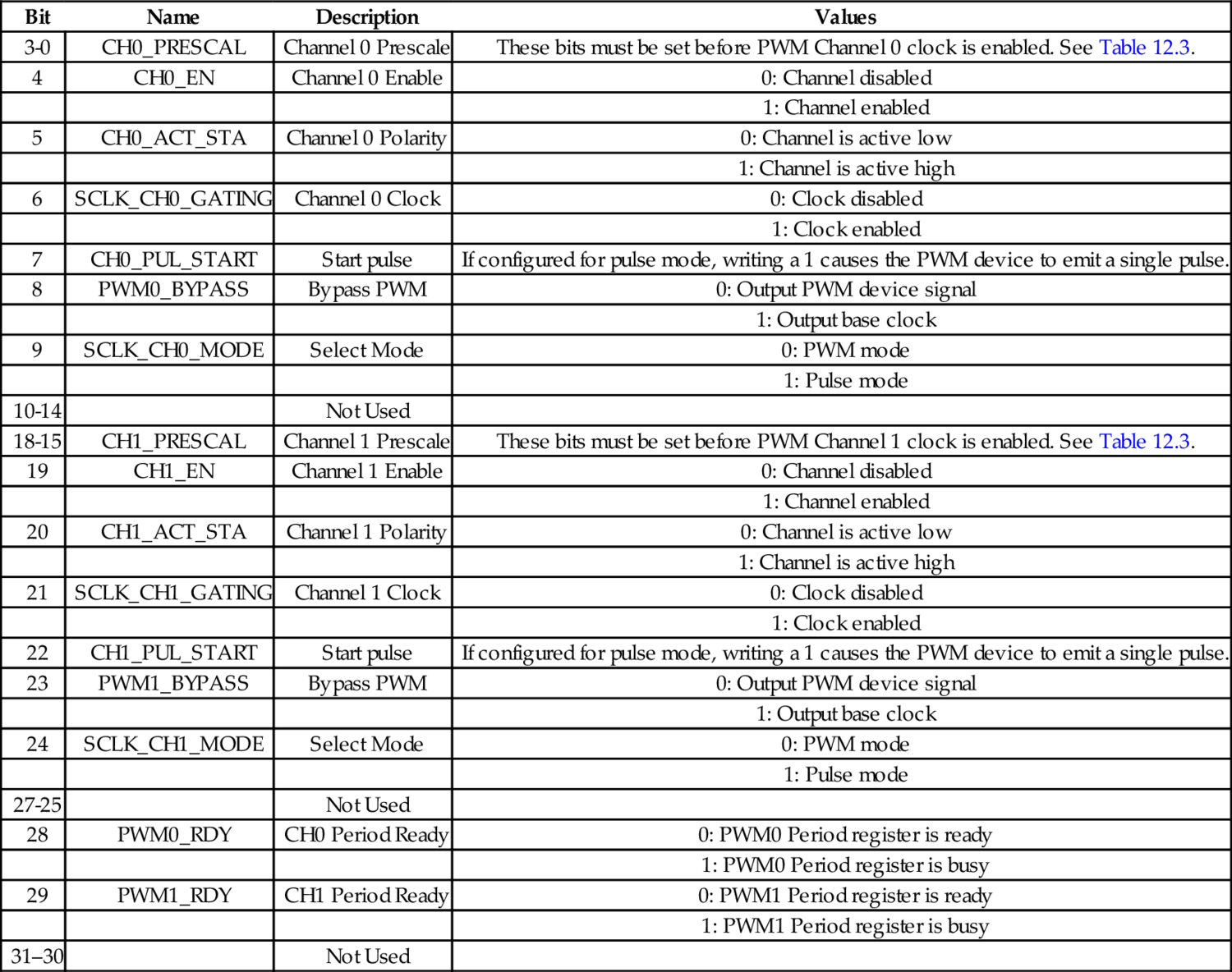

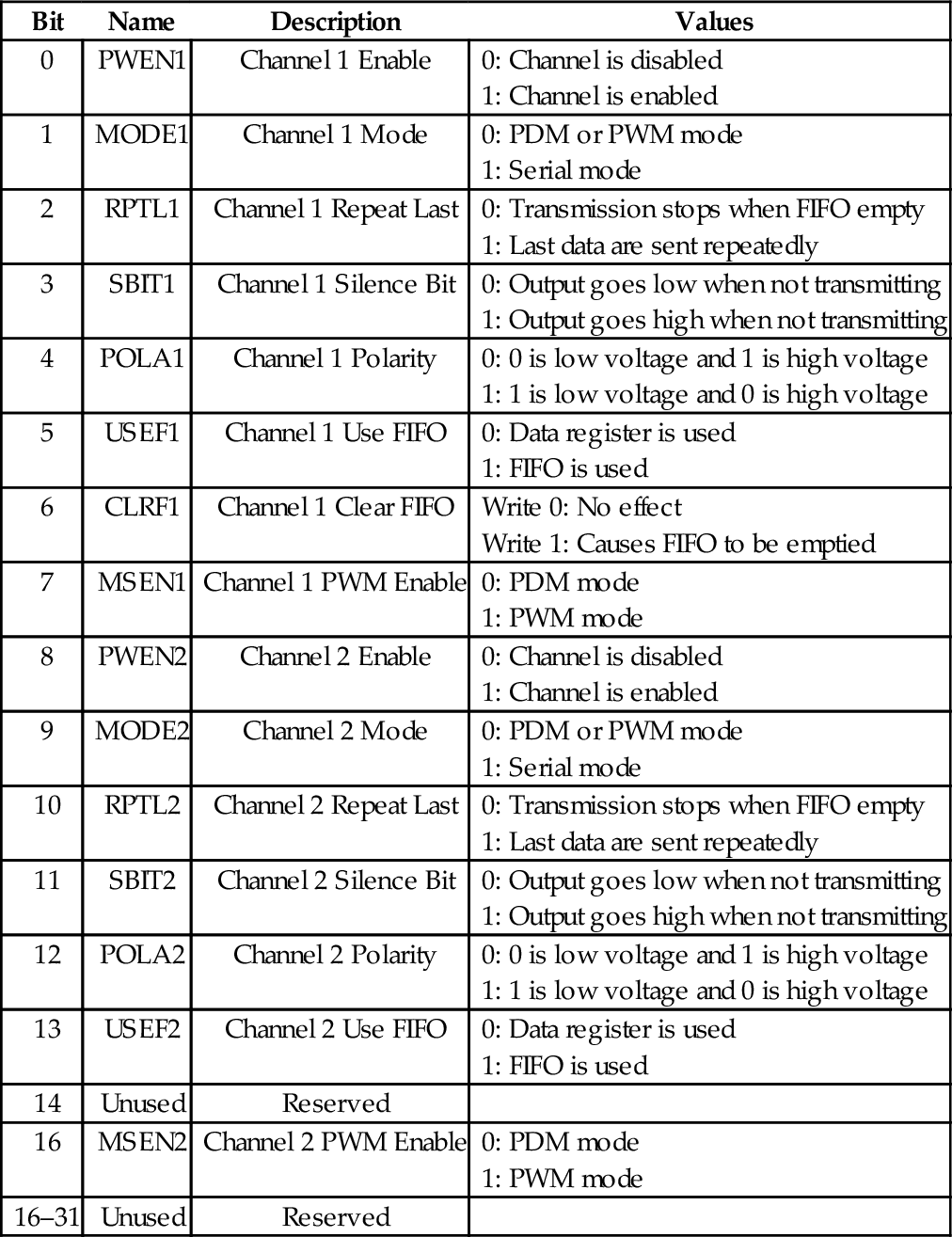

Table 12.2 Raspberry Pi PWM control register bits 399

Table 12.3 Prescaler bits in the pcDuino PWM device 401

Table 12.4 pcDuino PWM register map 401

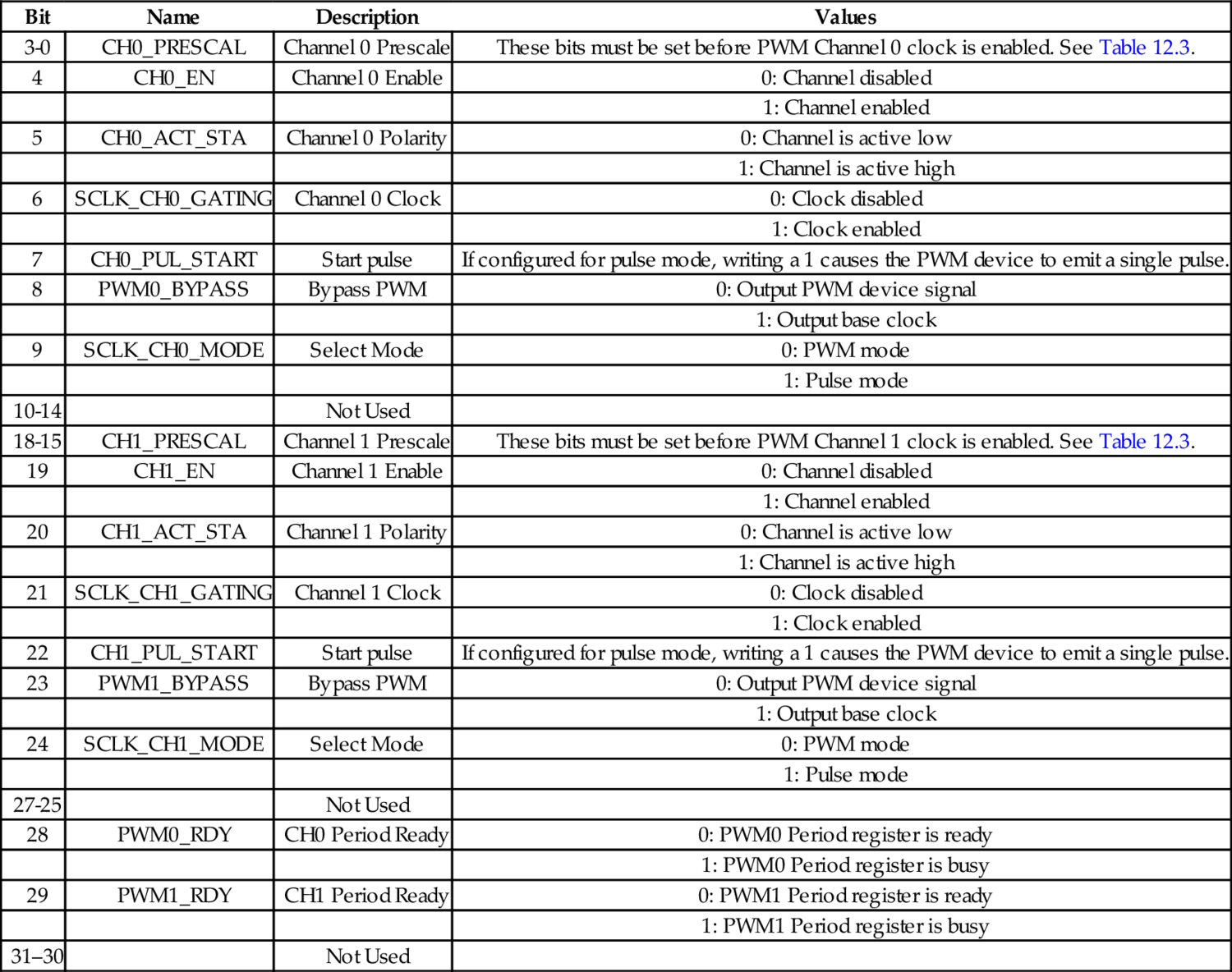

Table 12.5 pcDuino PWM control register bits 402

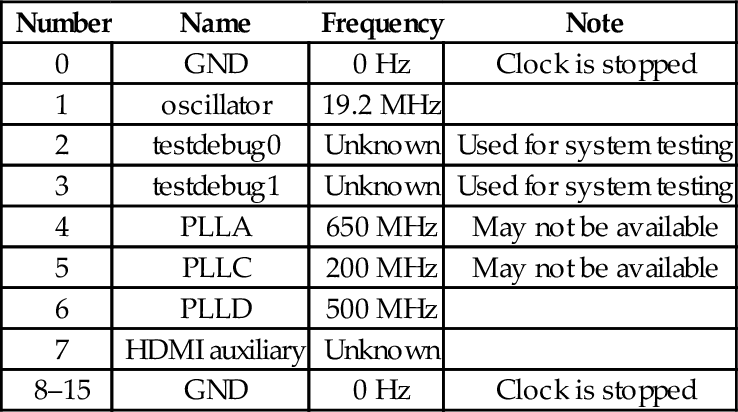

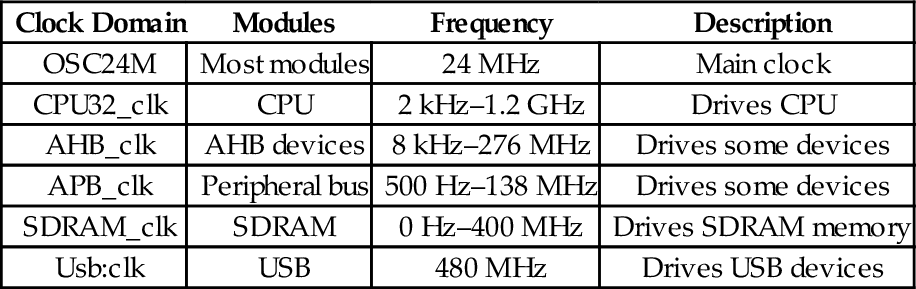

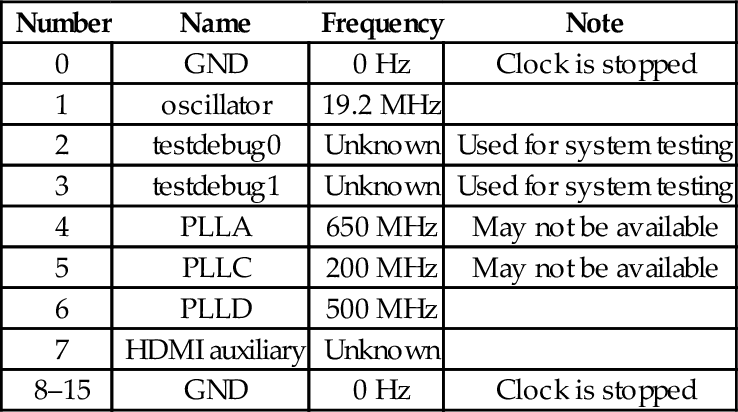

Table 13.1 Clock sources available for the clocks provided by the clock manager 407

Table 13.2 Some registers in the clock manager device 407

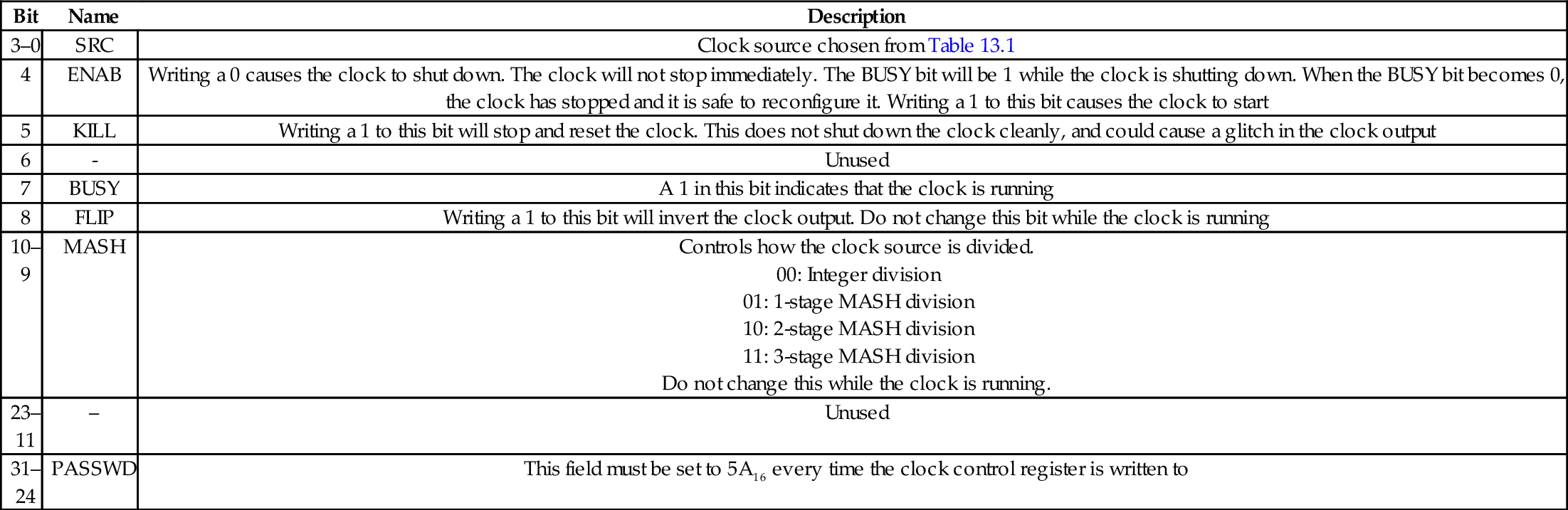

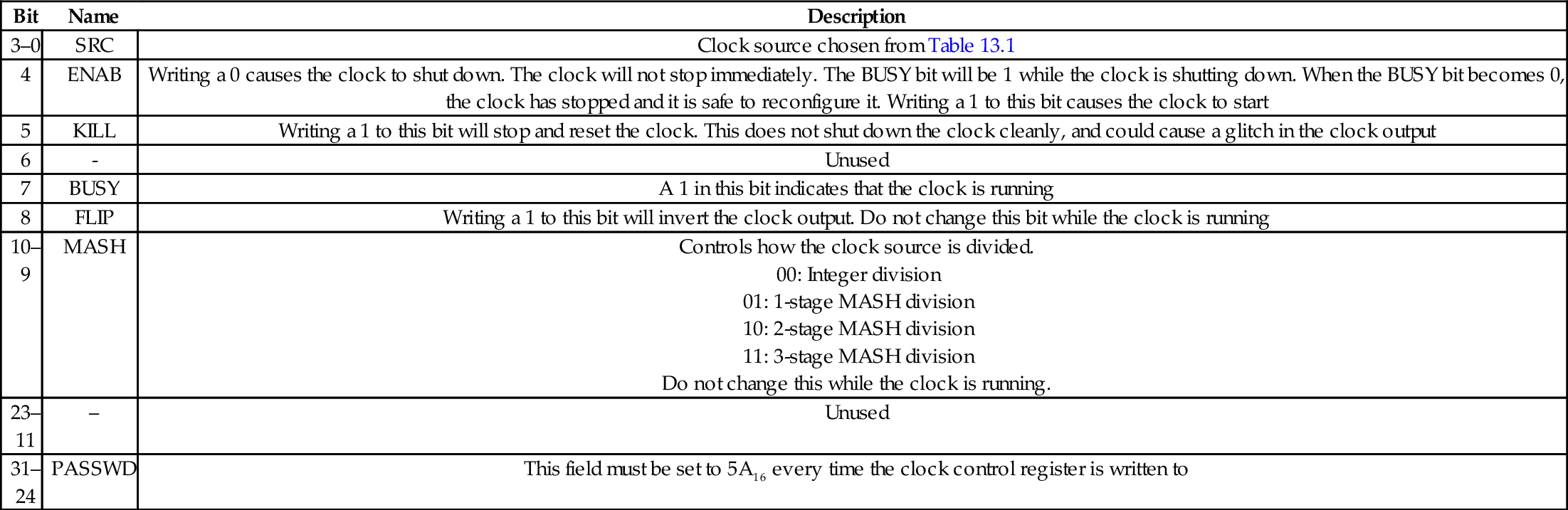

Table 13.3 Bit fields in the clock manager control registers 408

Table 13.4 Bit fields in the clock manager divisor registers 408

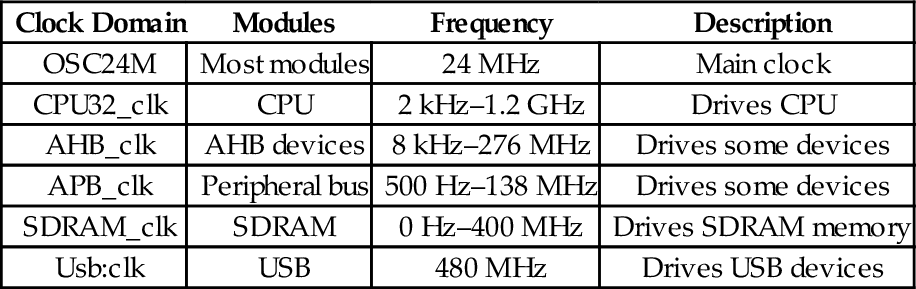

Table 13.5 Clock signals in the AllWinner A10/A20 SOC 409

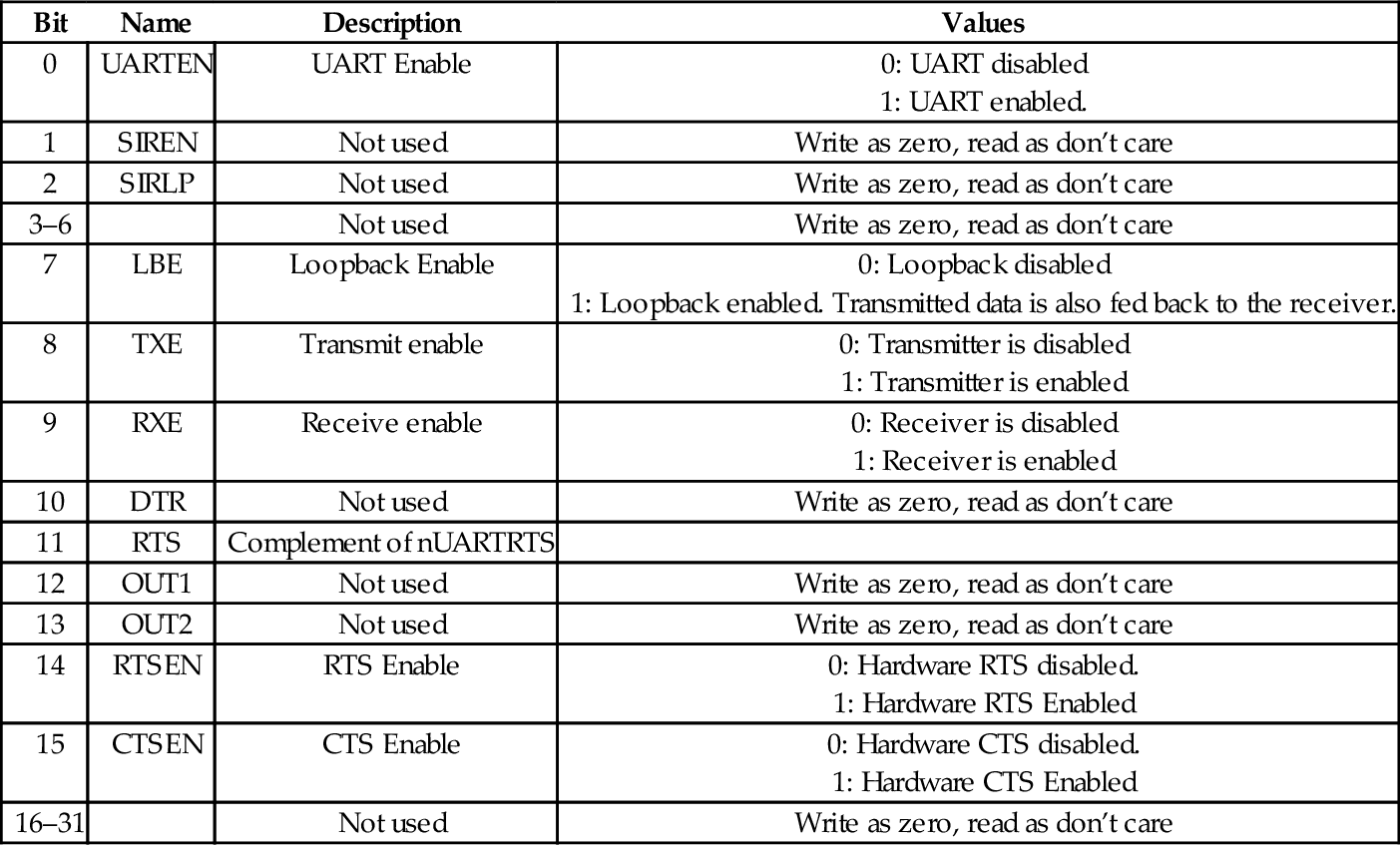

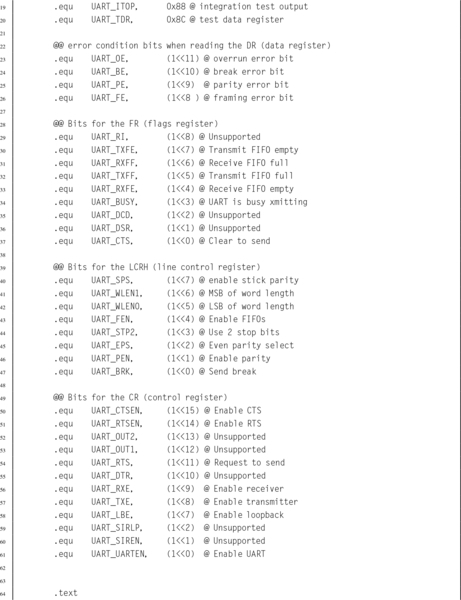

Table 13.6 Raspberry Pi UART0 register map 413

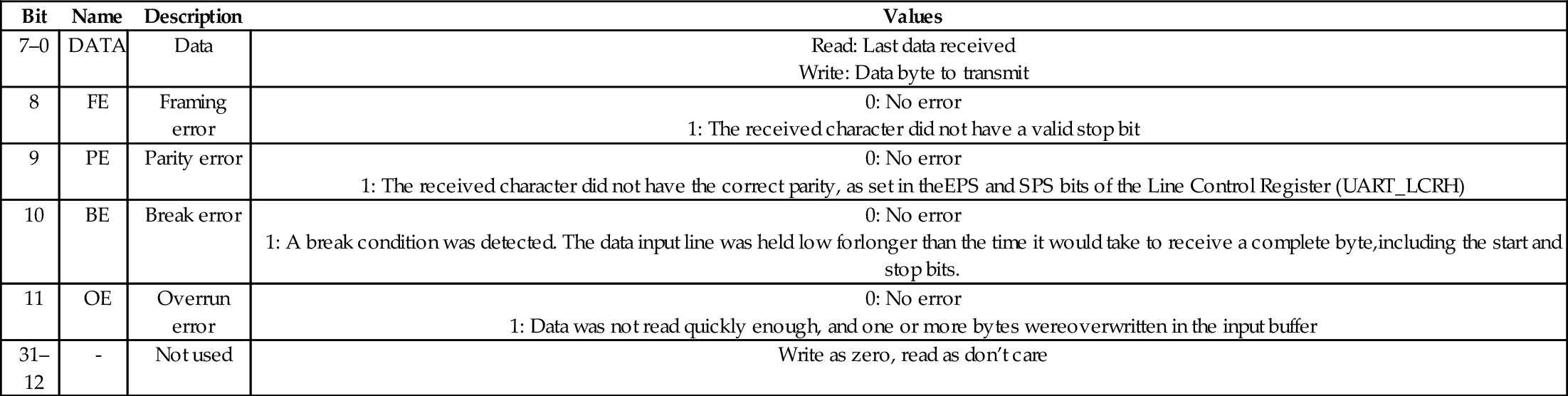

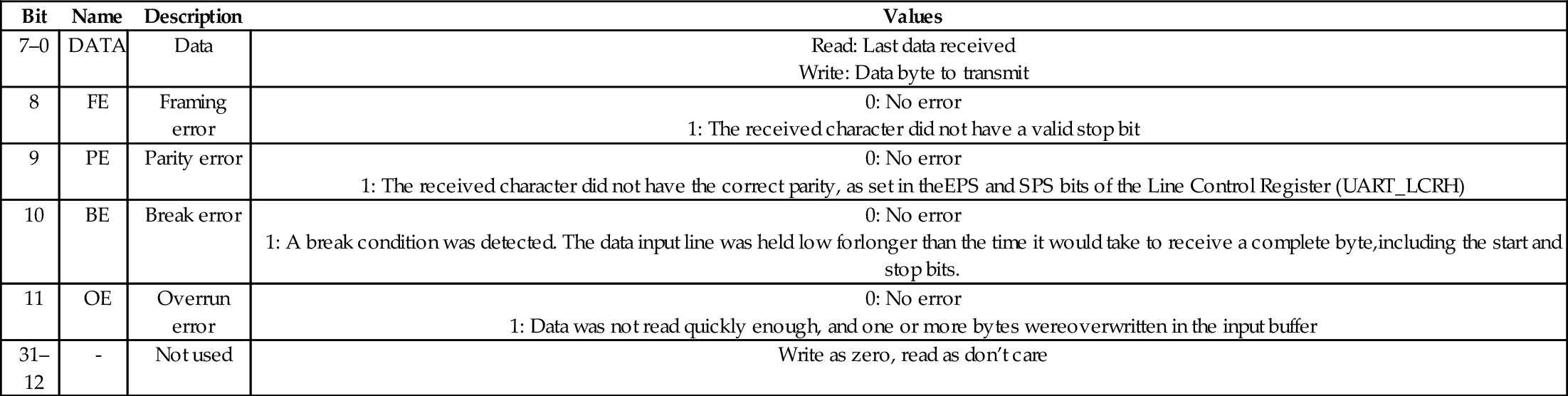

Table 13.7 Raspberry Pi UART data register 414

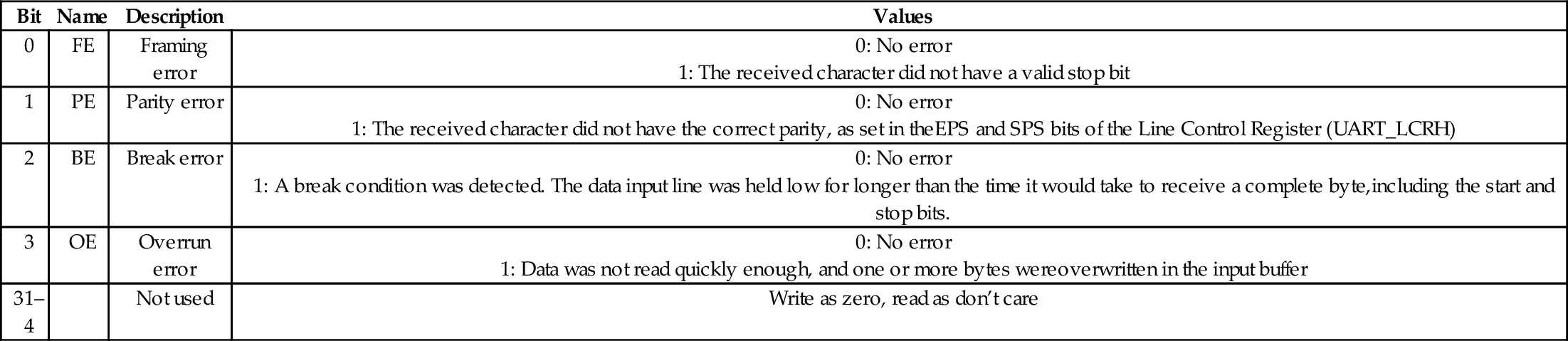

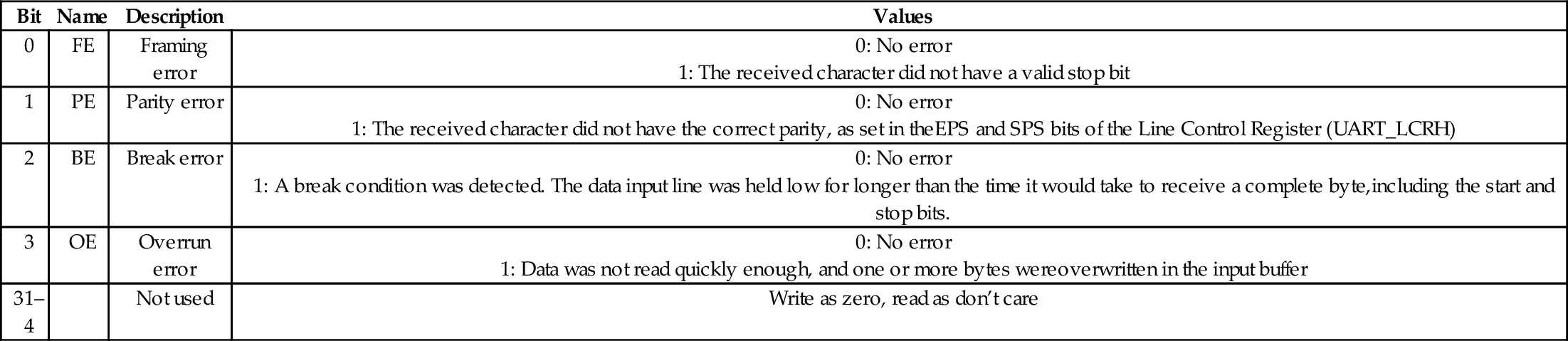

Table 13.8 Raspberry Pi UART receive status register/error clear register 415

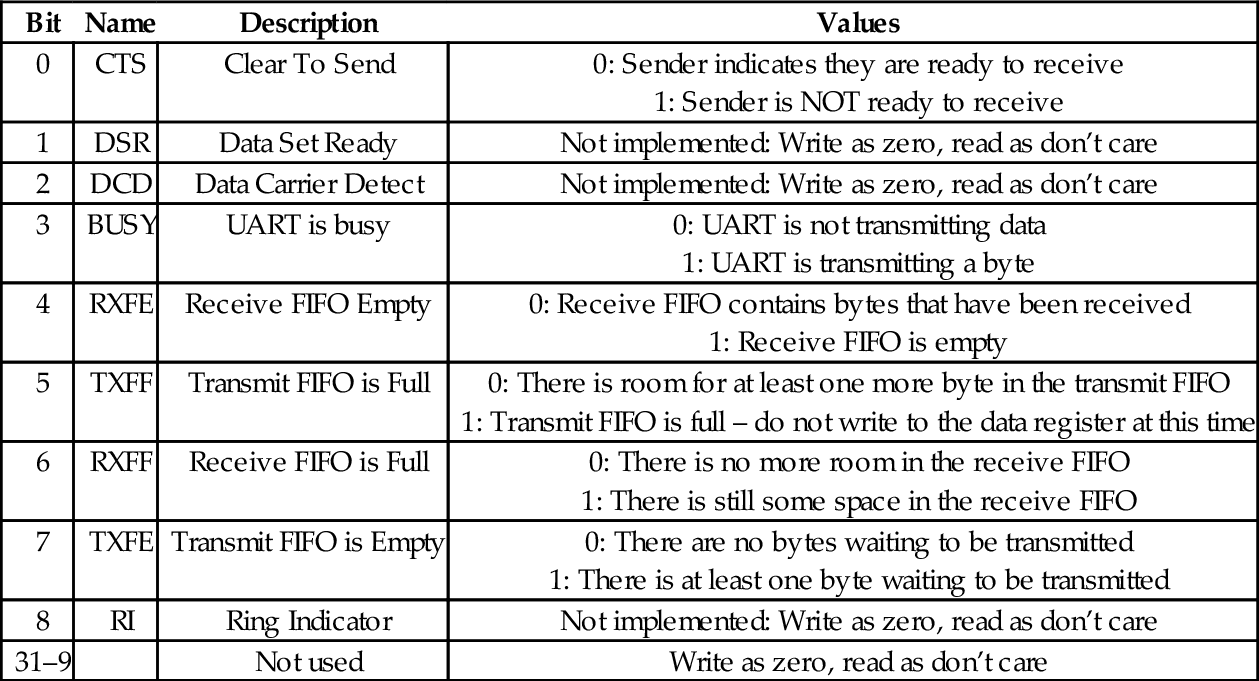

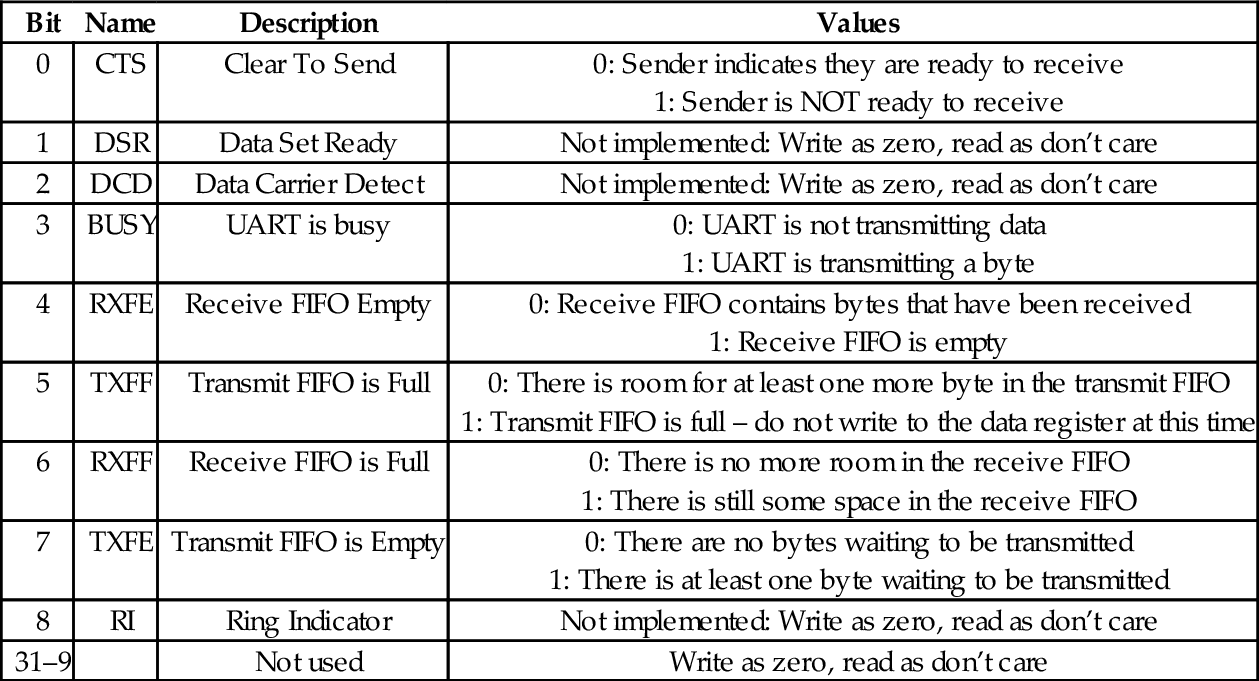

Table 13.9 Raspberry Pi UART flags register bits 415

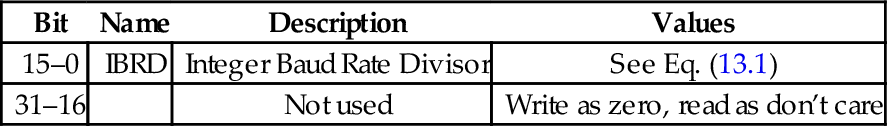

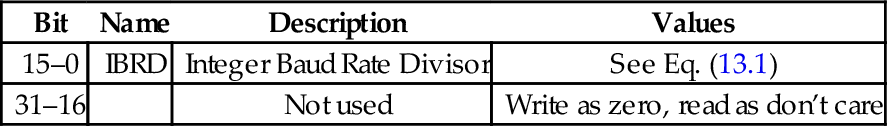

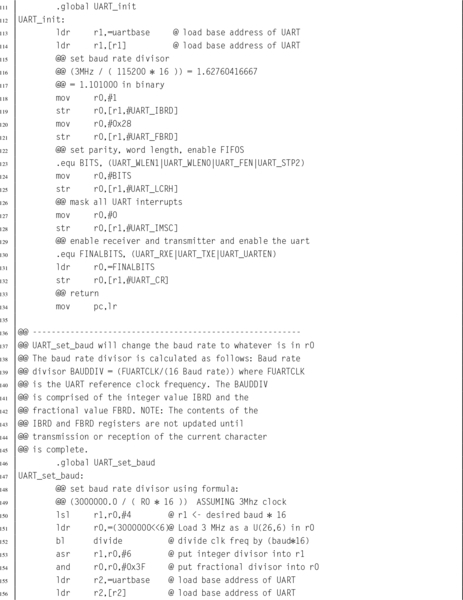

Table 13.10 Raspberry Pi UART integer baud rate divisor 416

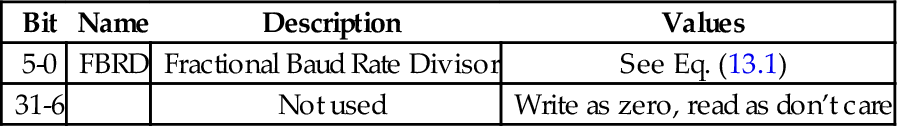

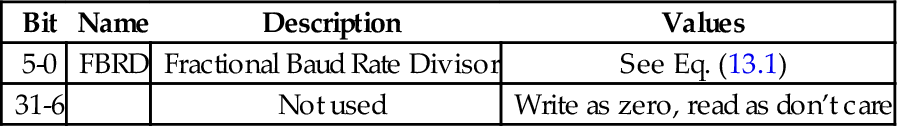

Table 13.11 Raspberry Pi UART fractional baud rate divisor 416

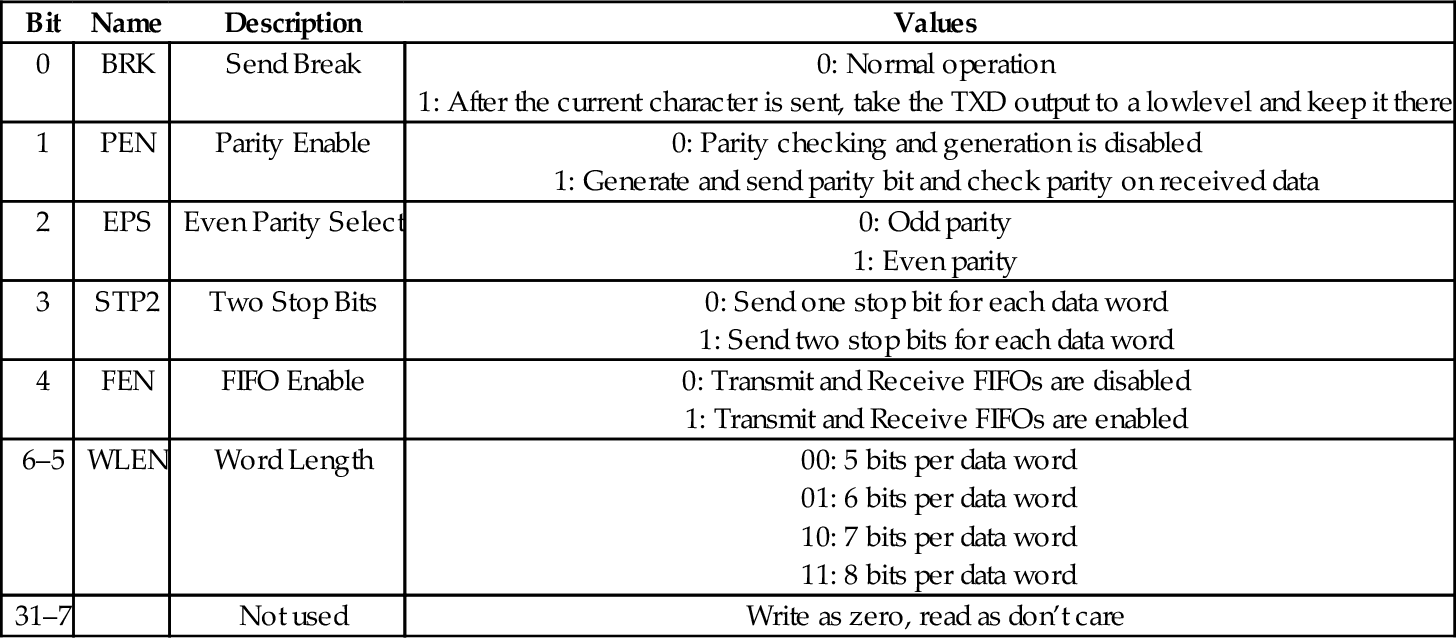

Table 13.12 Raspberry Pi UART line control register bits 416

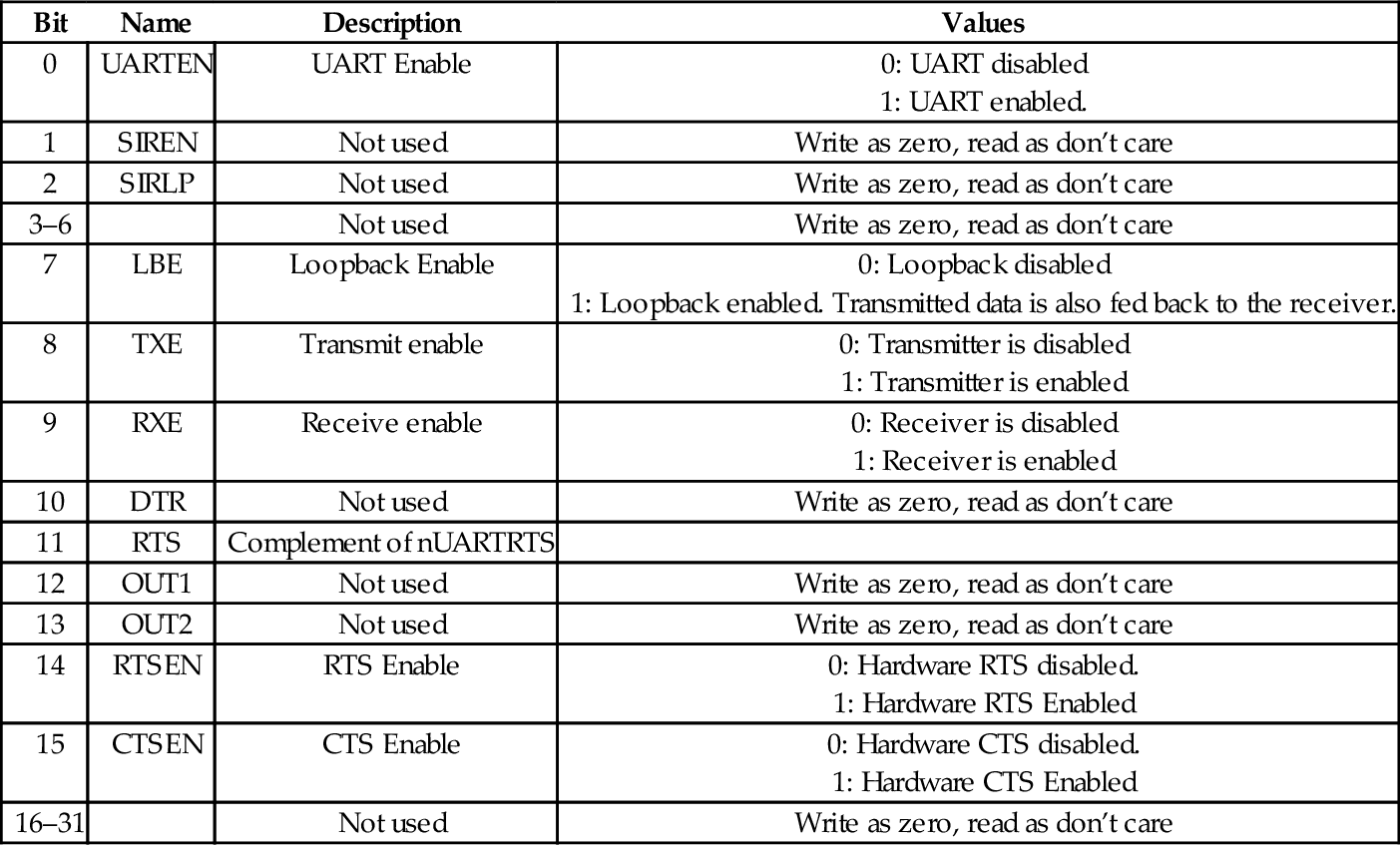

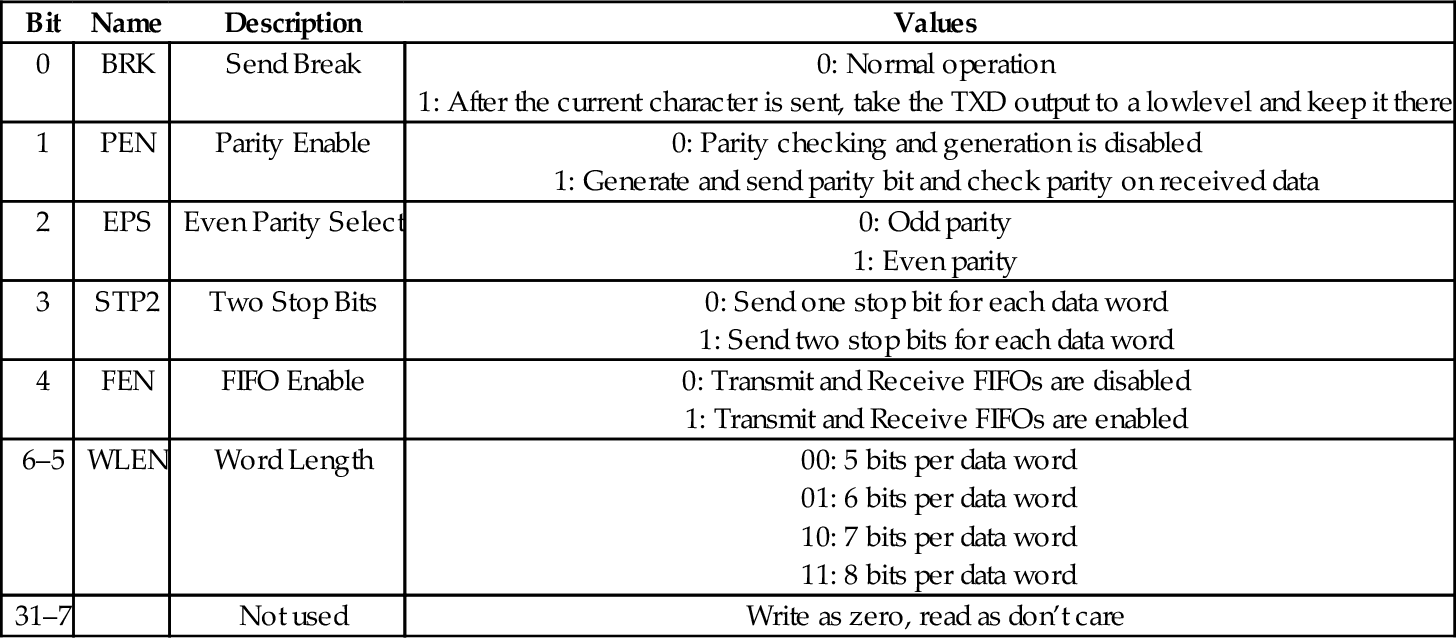

Table 13.13 Raspberry Pi UART control register bits 417

Table 13.14 pcDuino UART addresses 422

Table 13.15 pcDuino UART register offsets 423

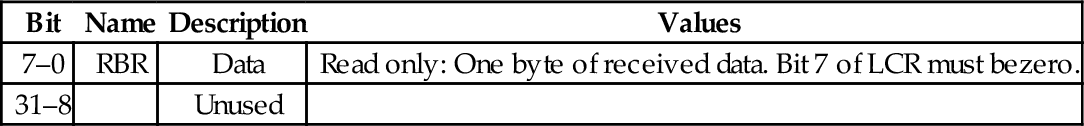

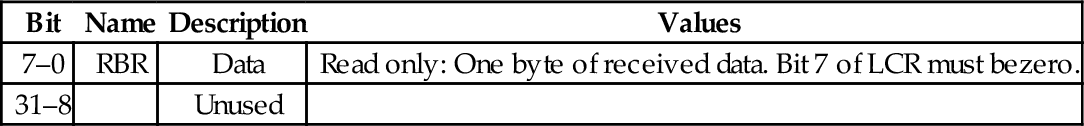

Table 13.16 pcDuno UART receive buffer register 424

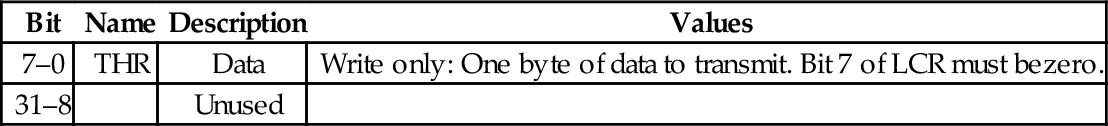

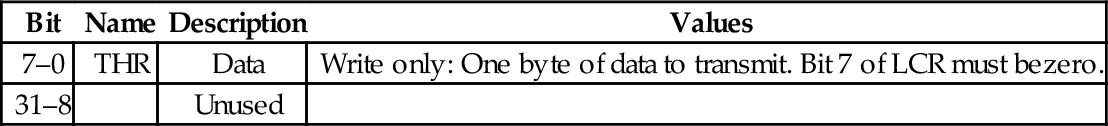

Table 13.17 pcDuno UART transmit holding register 424

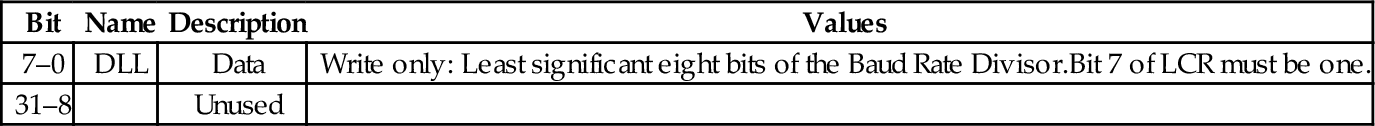

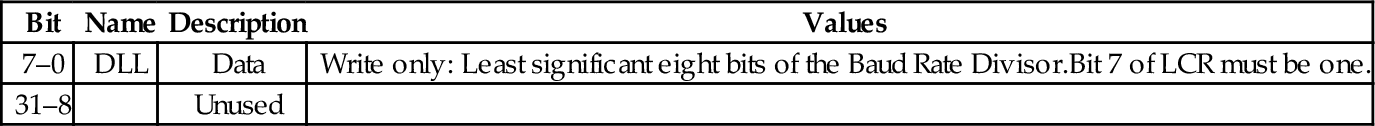

Table 13.18 pcDuno UART divisor latch low register 424

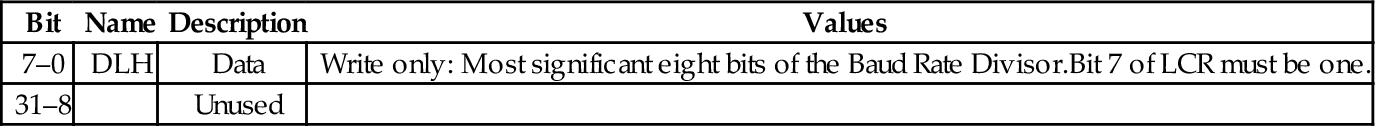

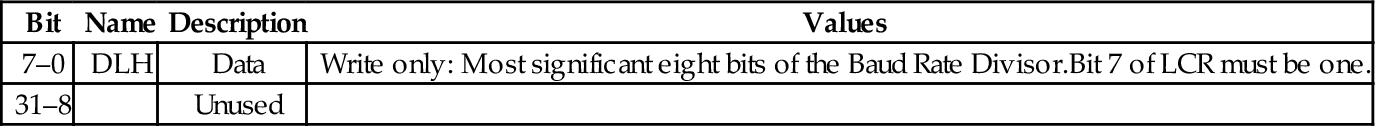

Table 13.19 pcDuno UART divisor latch high register 425

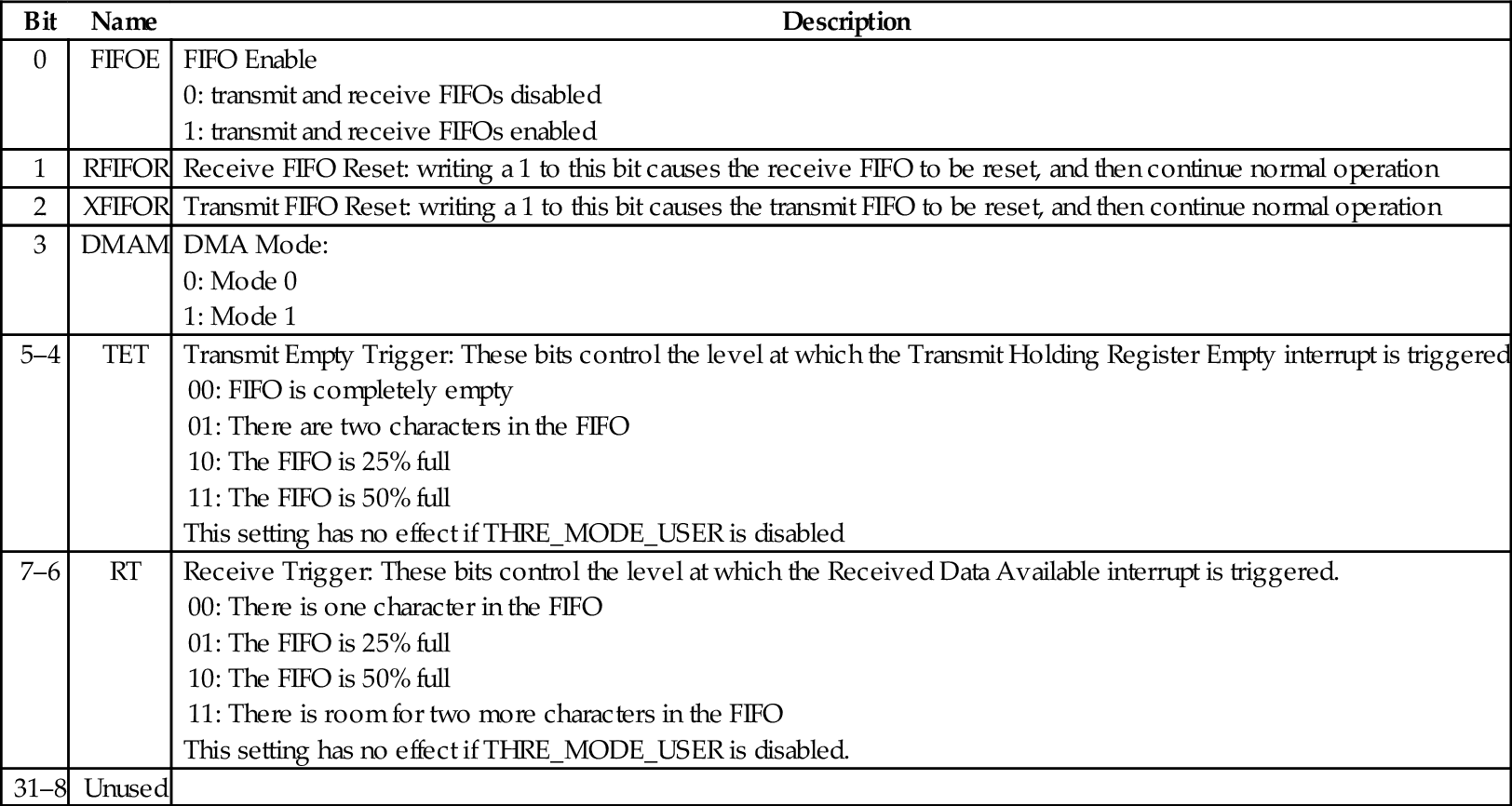

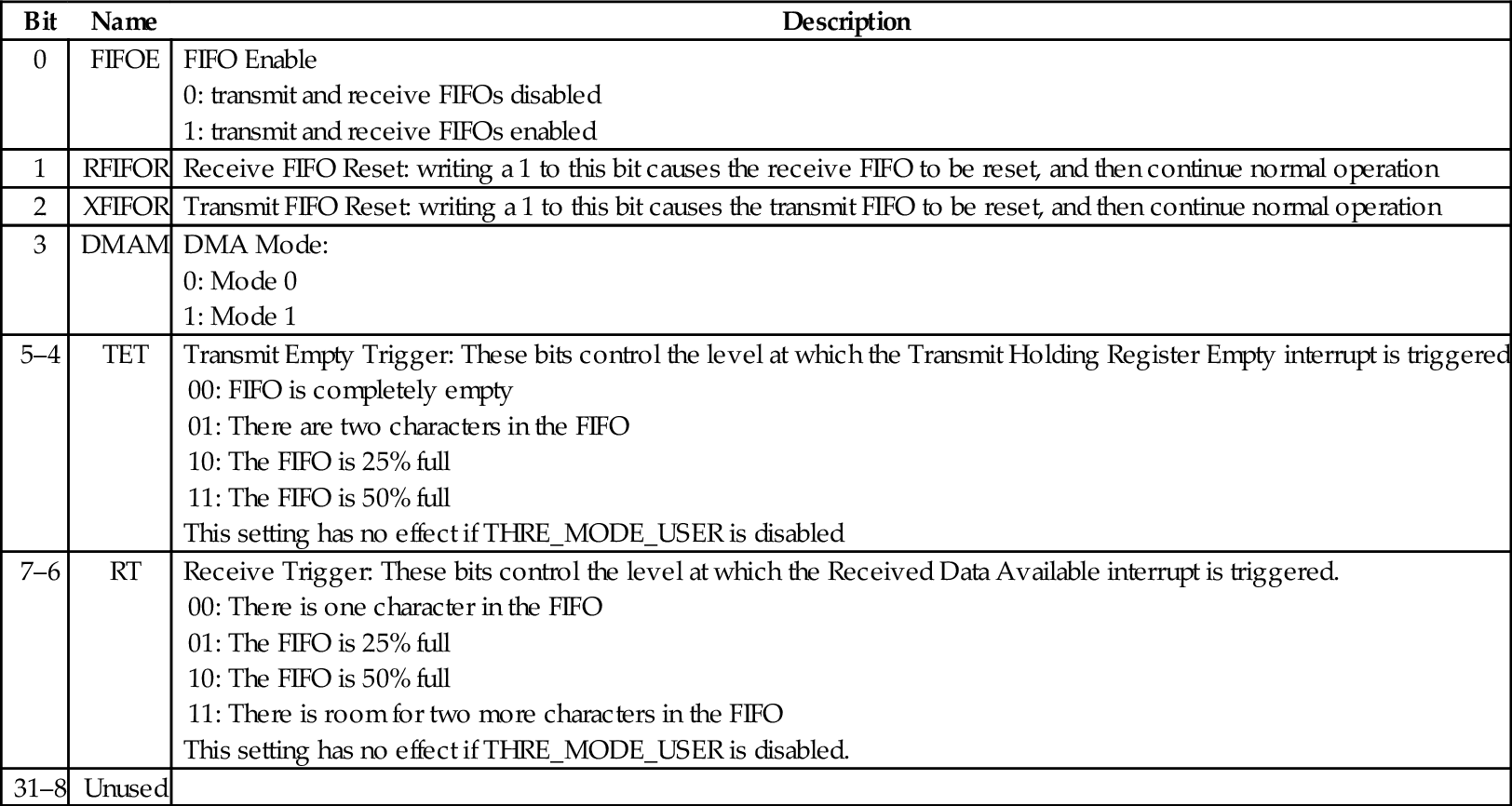

Table 13.20 pcDuno UART FIFO control register 425

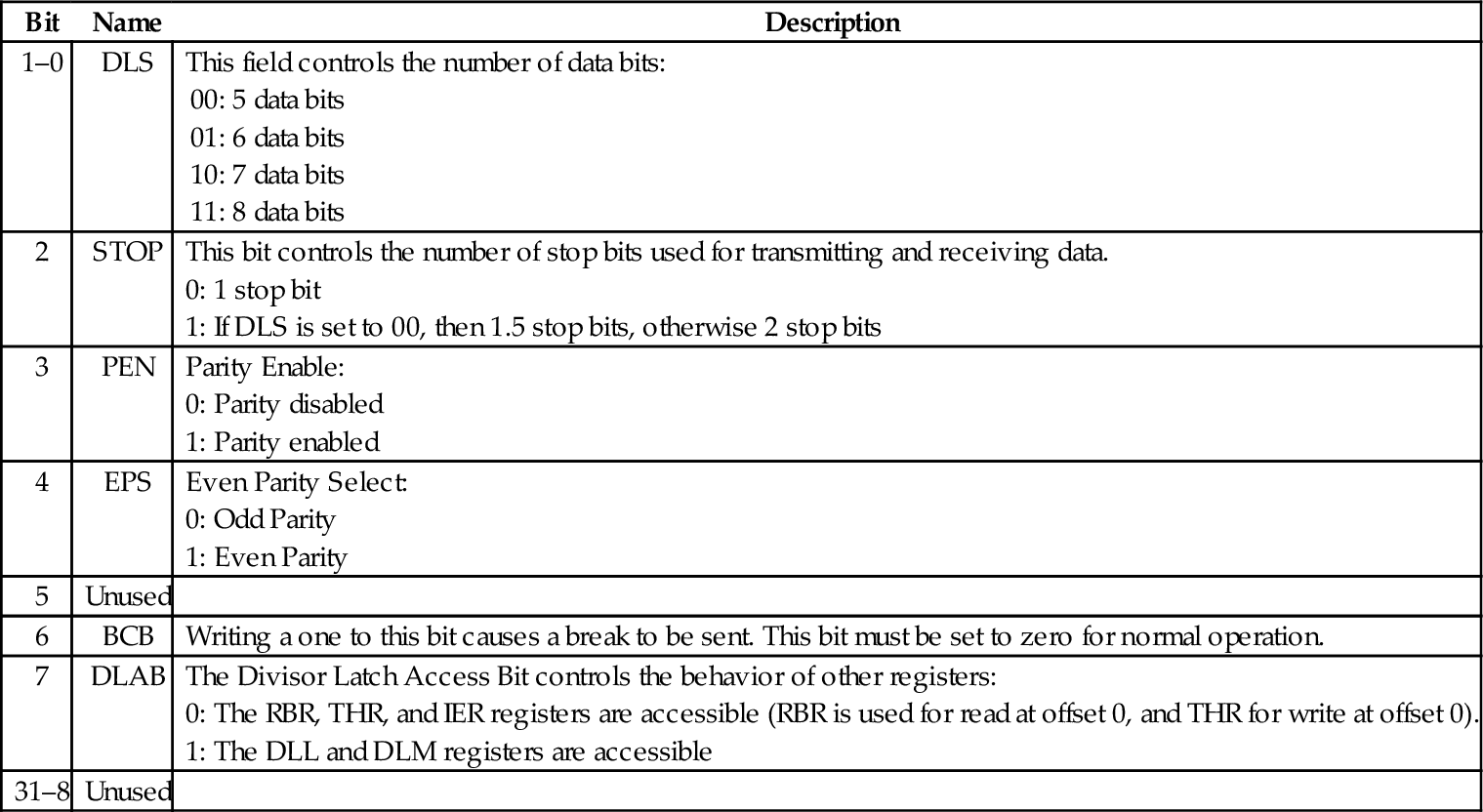

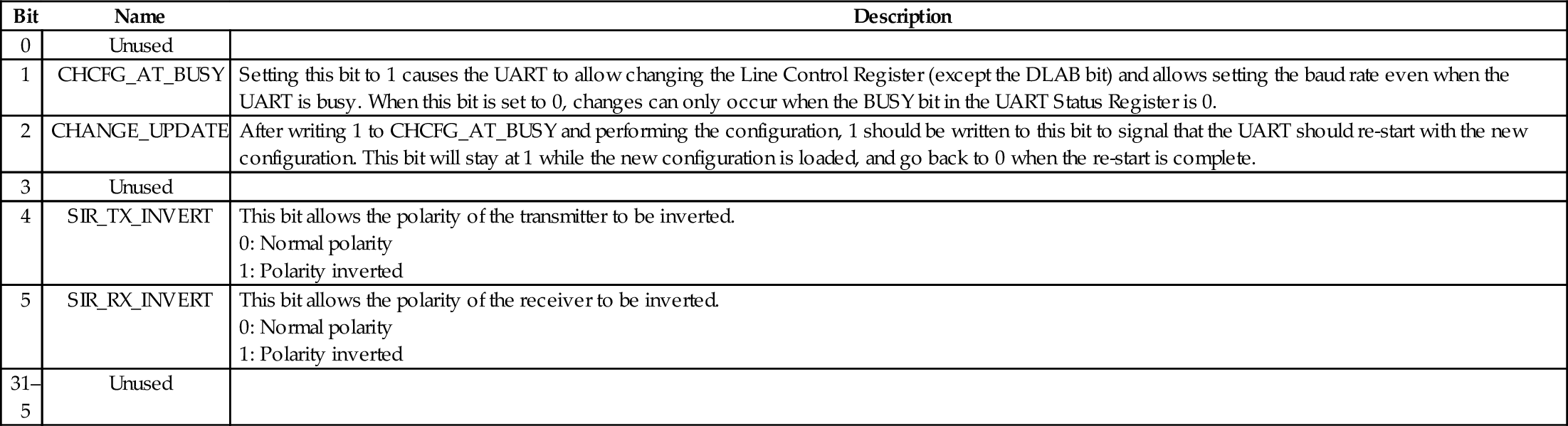

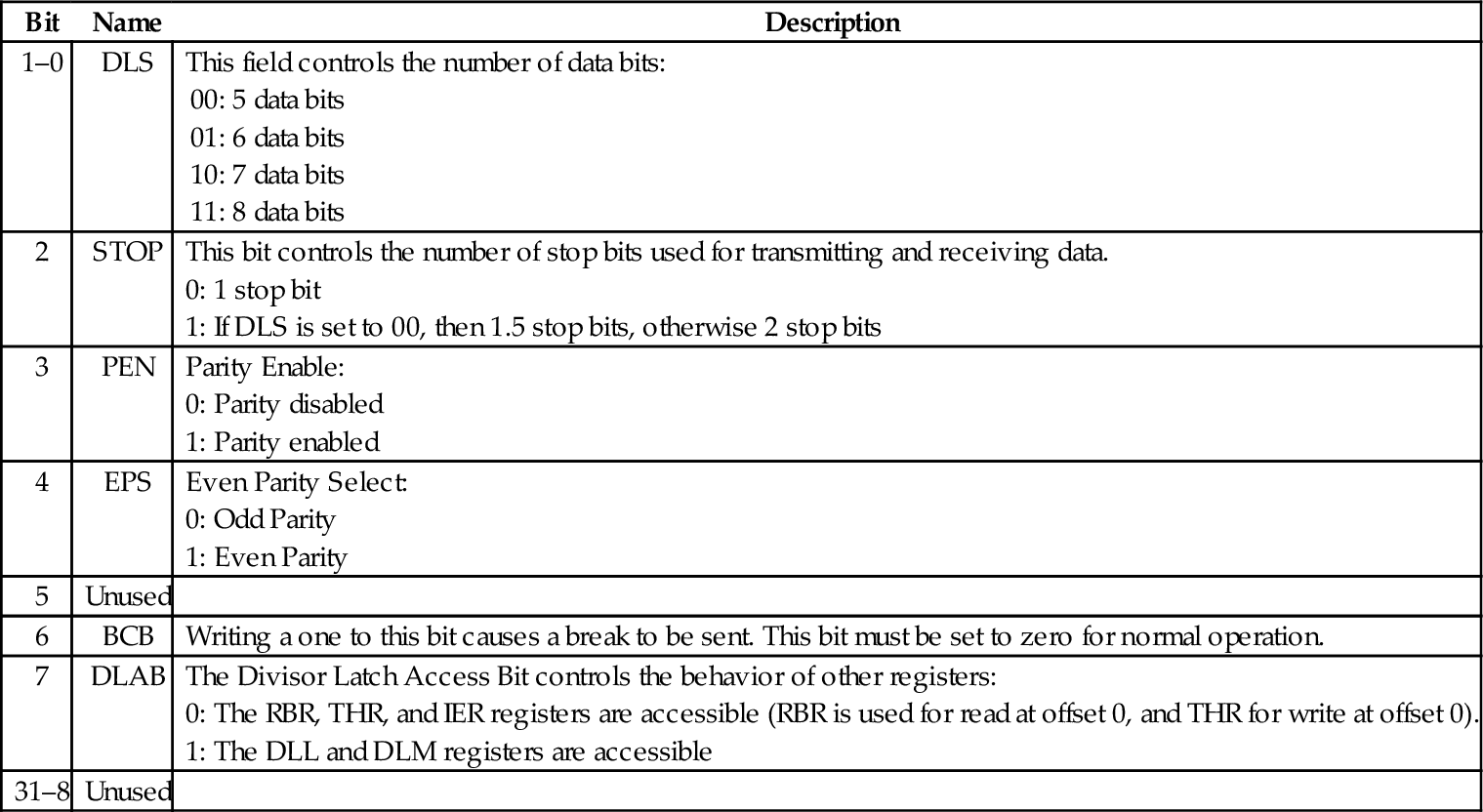

Table 13.21 pcDuno UART line control register 426

Table 13.22 pcDuno UART line status register 427

Table 13.23 pcDuno UART status register 427

Table 13.24 pcDuno UART transmit FIFO level register 428

Table 13.25 pcDuno UART receive FIFO level register 428

Table 13.26 pcDuno UART transmit halt register 428

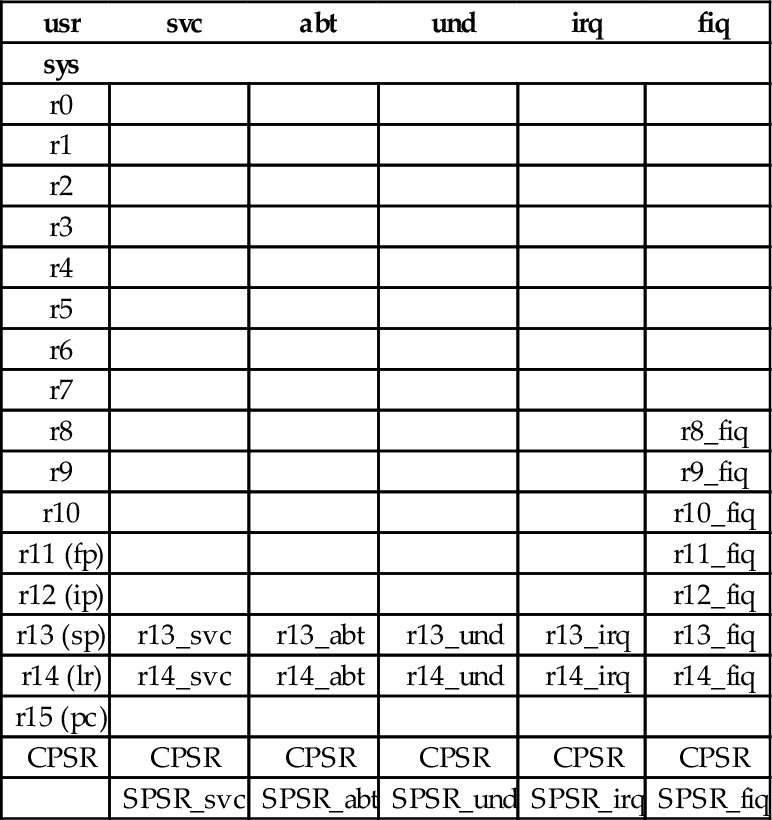

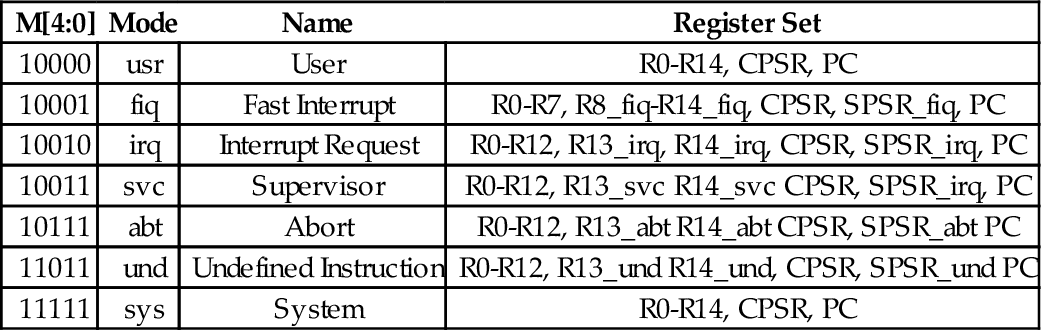

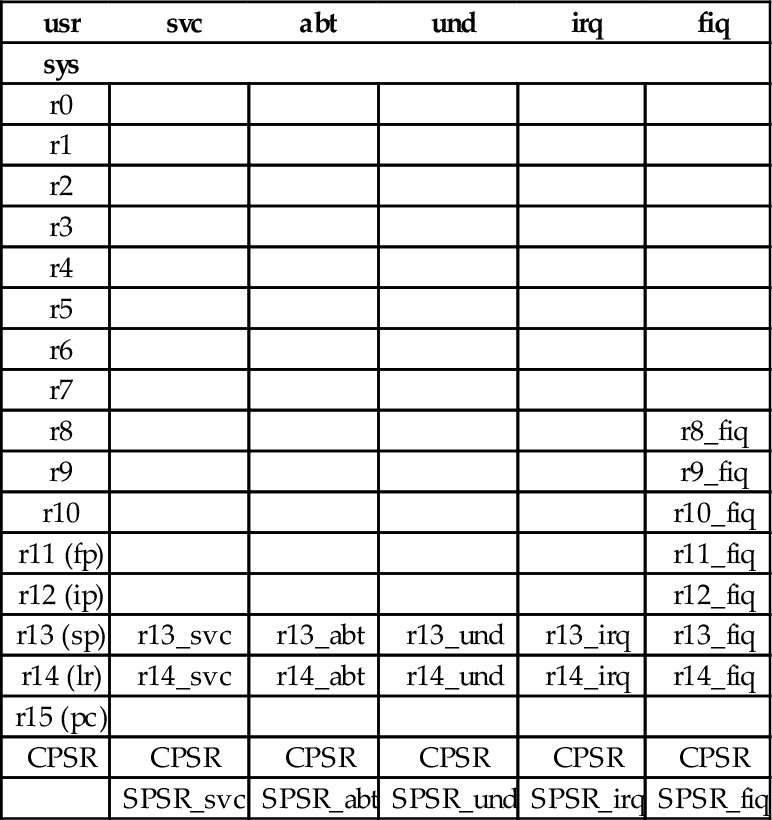

Table 14.1 The ARM user and system registers 433

Table 14.2 Mode bits in the PSR 434

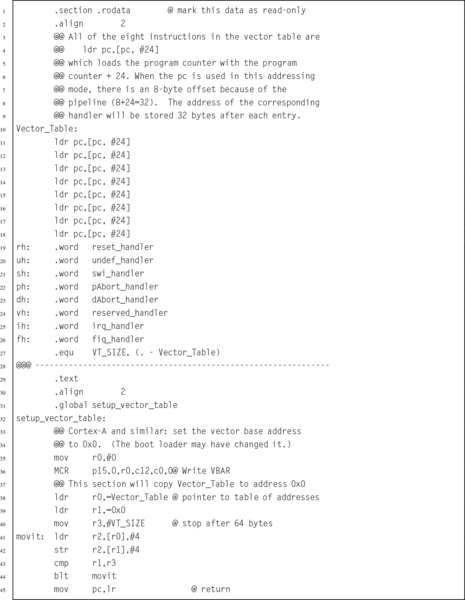

Table 14.3 ARM vector table 435

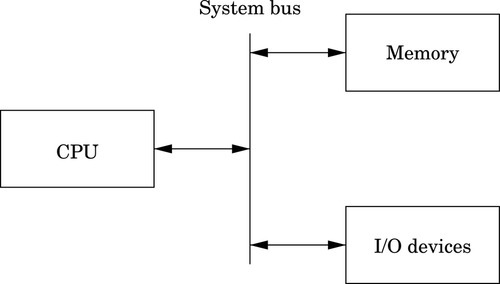

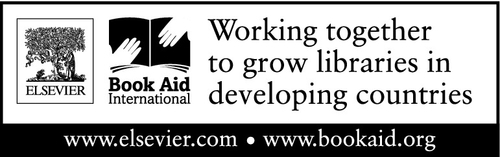

Figure 1.1 Simplified representation of a computer system 4

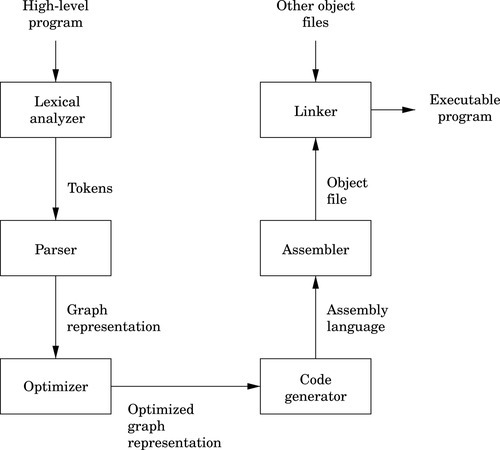

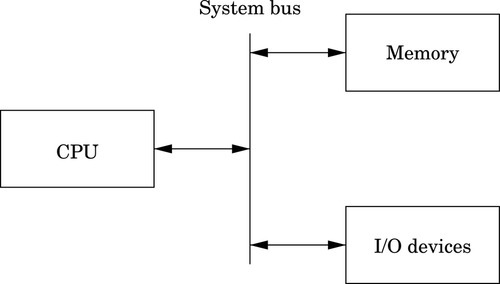

Figure 1.2 Stages of a typical compilation sequence 6

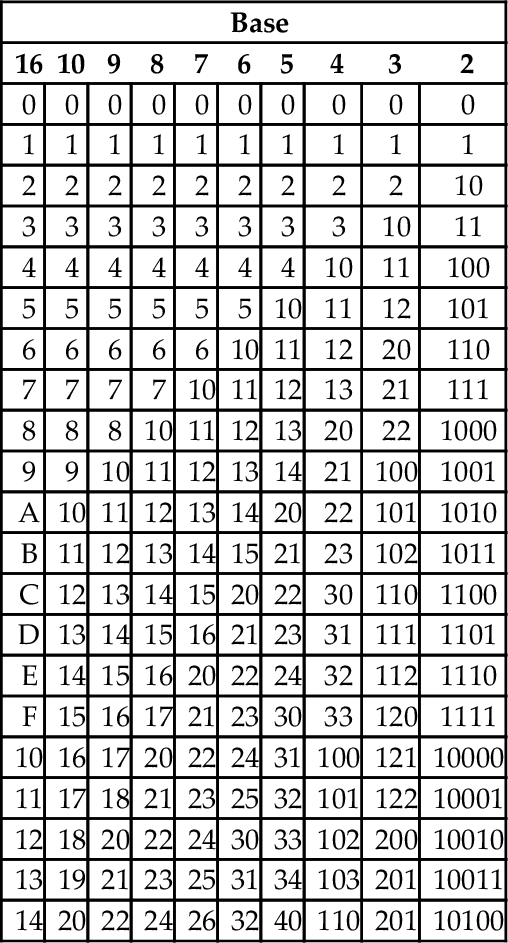

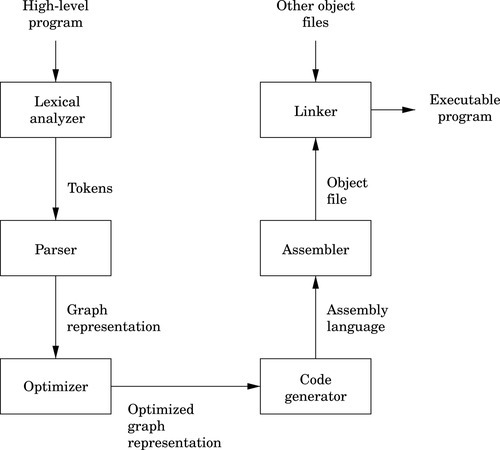

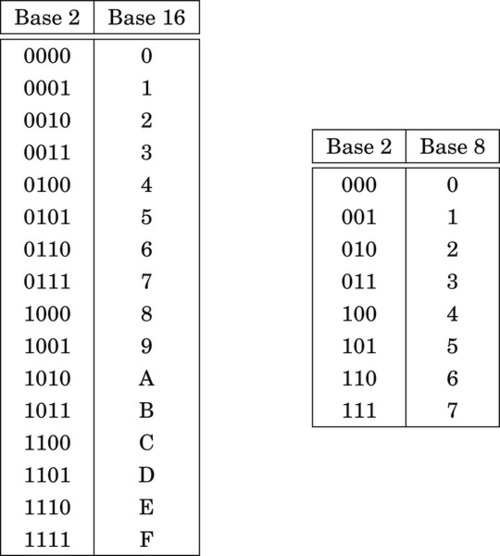

Figure 1.3 Tables used for converting between binary, octal, and hex 14

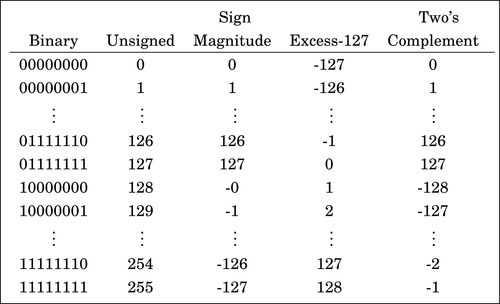

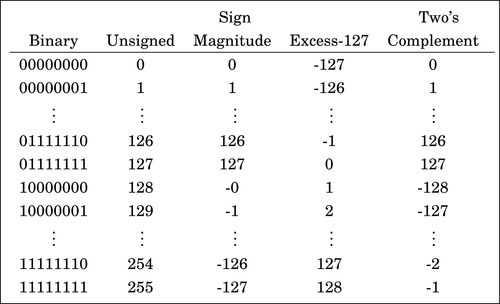

Figure 1.4 Four different representations for binary integers 16

Figure 1.5 Complement tables for bases ten and two 17

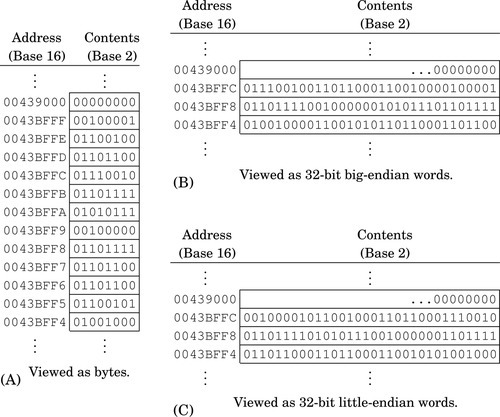

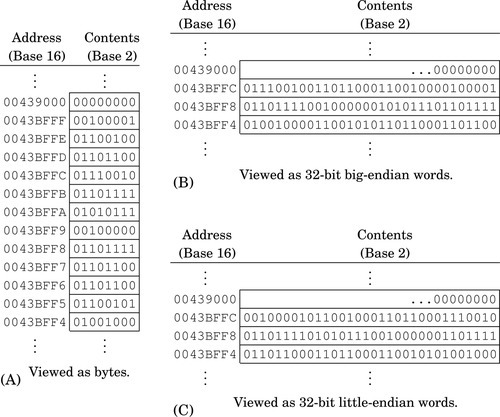

Figure 1.6 A section of memory 29

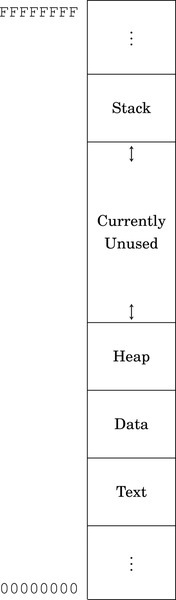

Figure 1.7 Typical memory layout for a program with a 32-bit address space 30

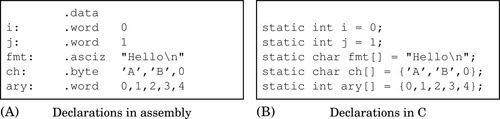

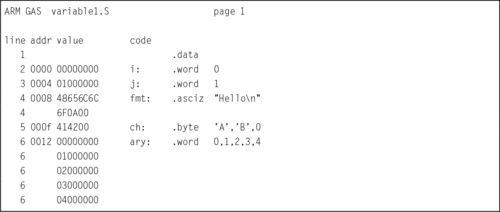

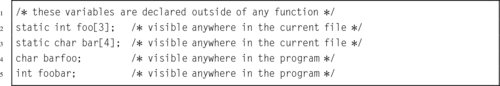

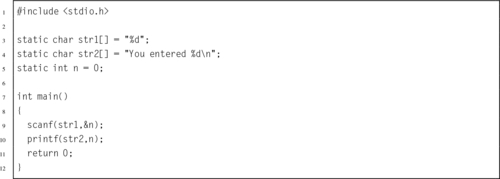

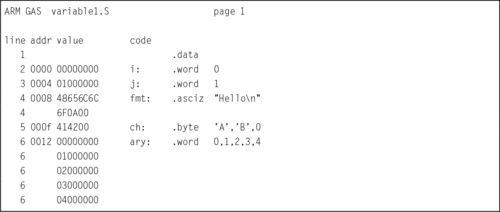

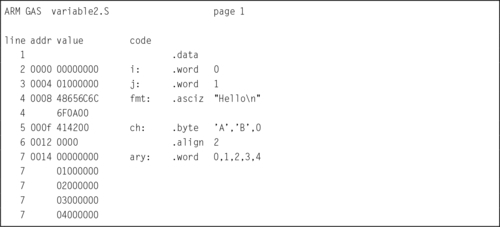

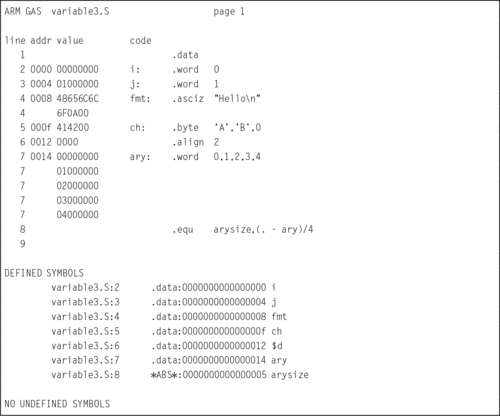

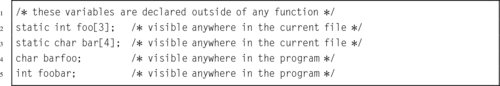

Figure 2.1 Equivalent static variable declarations in assembly and C 42

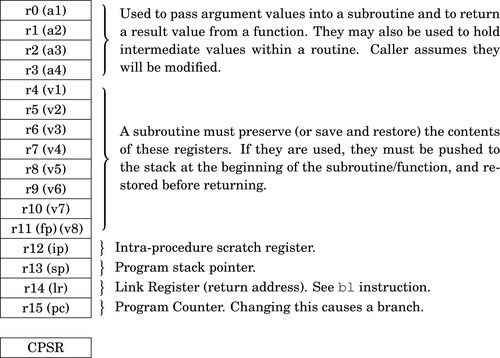

Figure 3.1 The ARM processor architecture 54

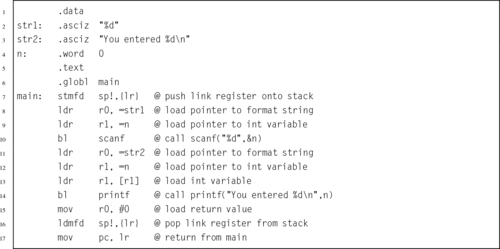

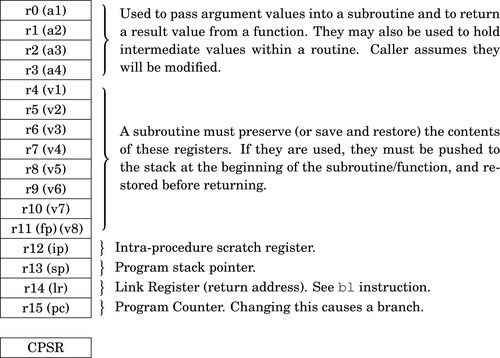

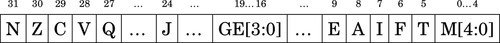

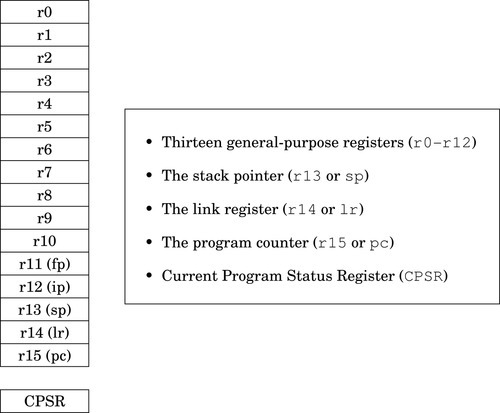

Figure 3.2 The ARM user program registers 56

Figure 3.3 The ARM process status register 57

Figure 5.1 ARM user program registers 112

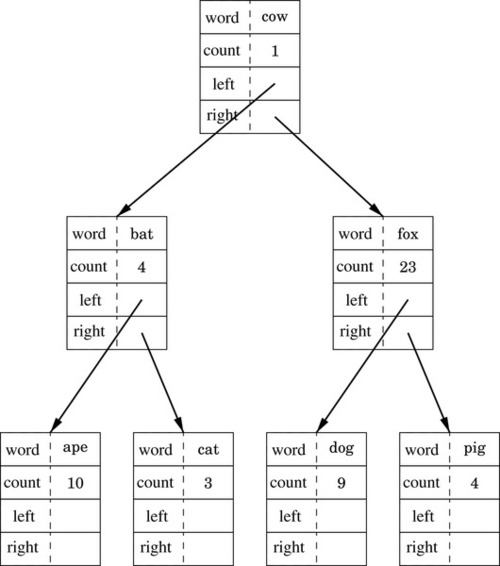

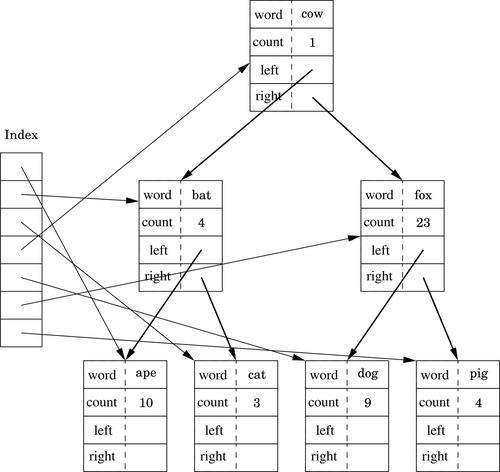

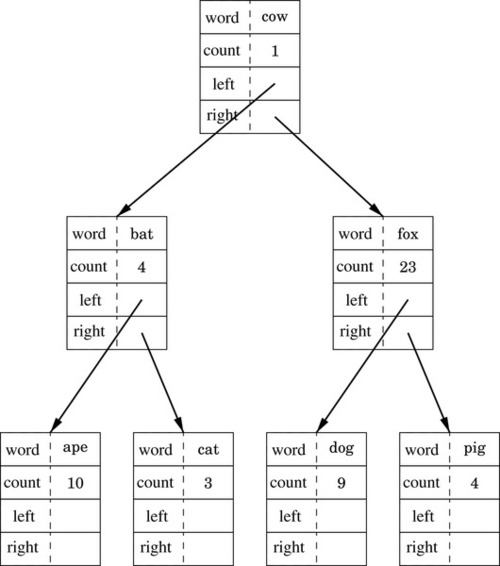

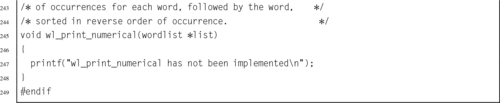

Figure 6.1 Binary tree of word frequencies 151

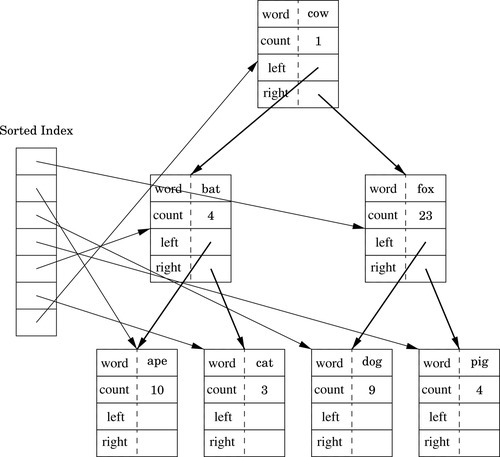

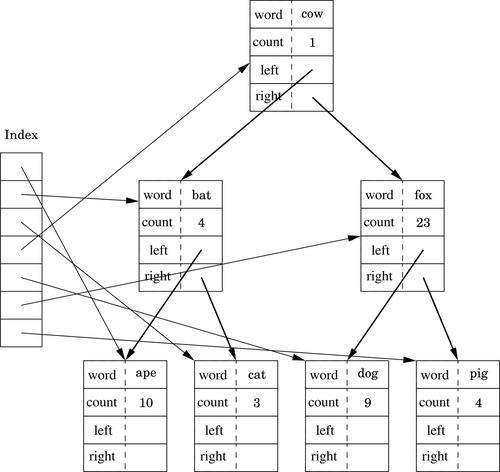

Figure 6.2 Binary tree of word frequencies with index added 157

Figure 6.3 Binary tree of word frequencies with sorted index 158

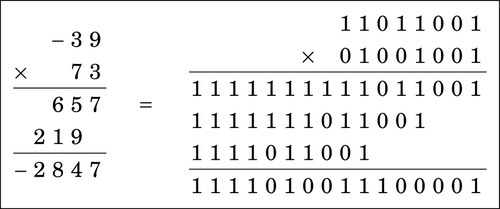

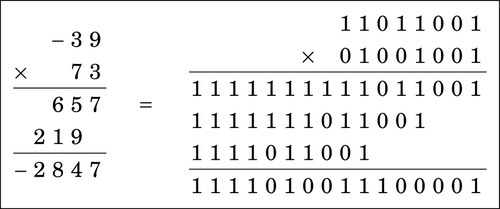

Figure 7.1 In signed 8-bit math, 110110012 is −3910 179

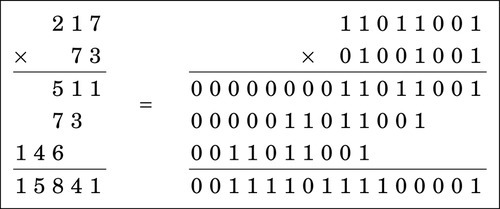

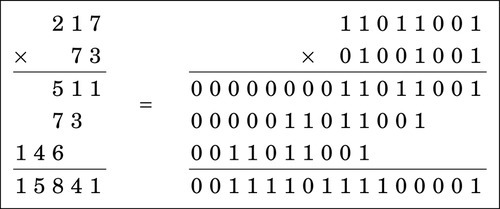

Figure 7.2 In unsigned 8-bit math, 110110012 is 21710 179

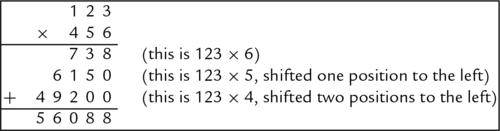

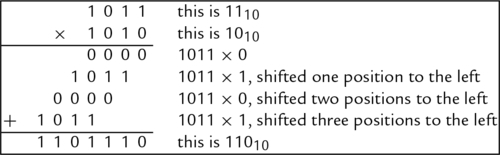

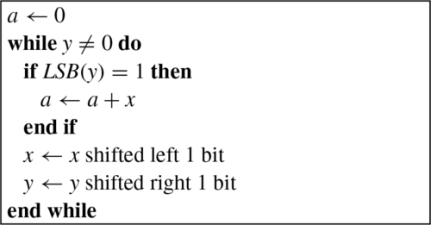

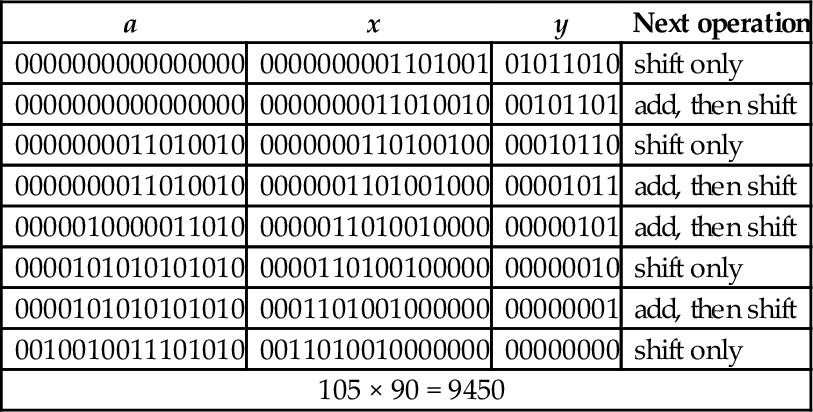

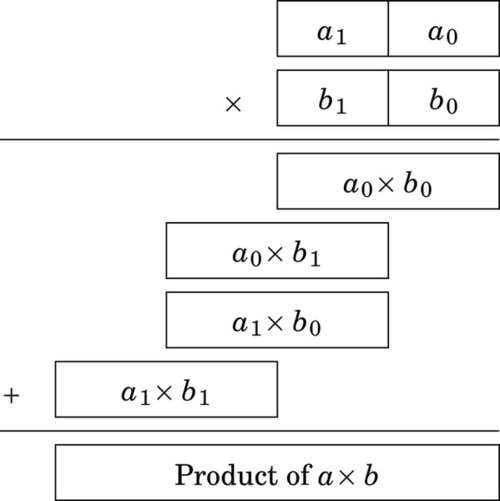

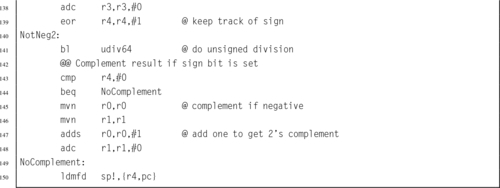

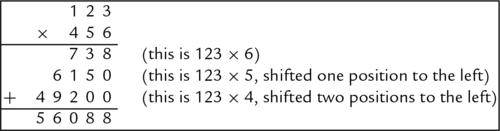

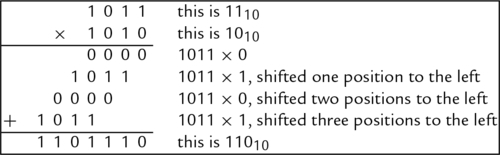

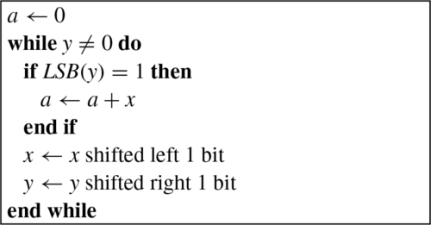

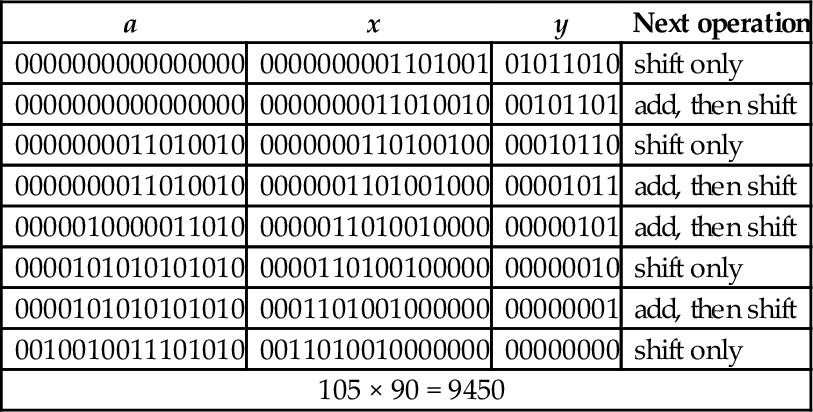

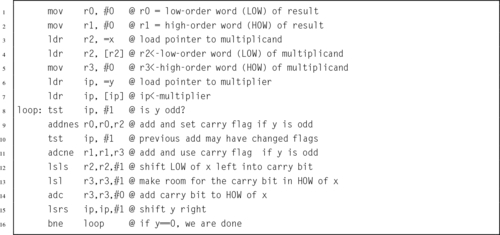

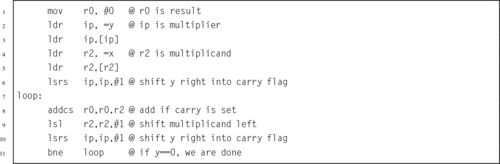

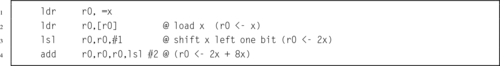

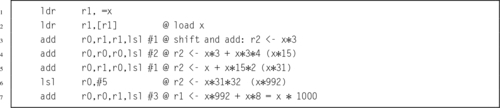

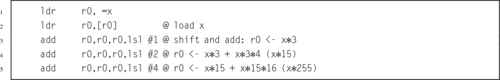

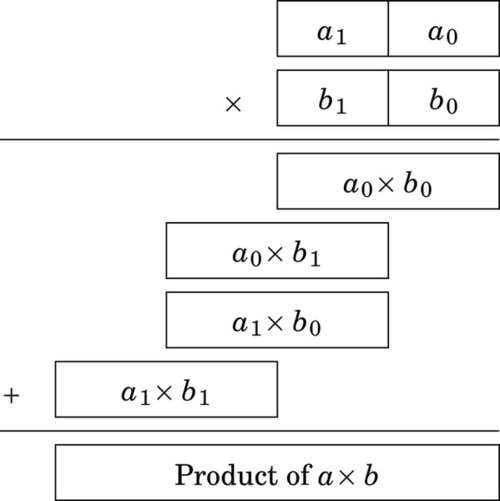

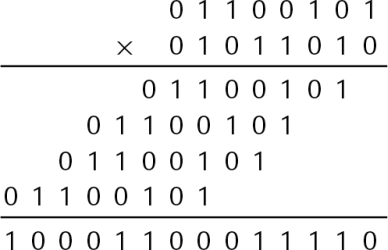

Figure 7.3 Multiplication of large numbers 180

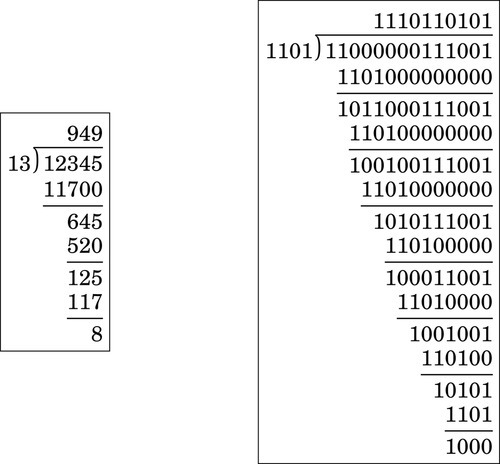

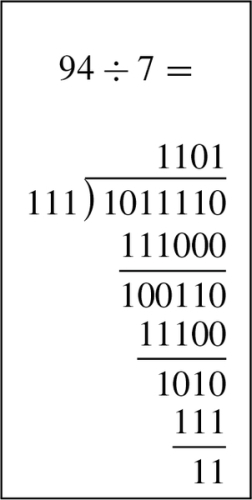

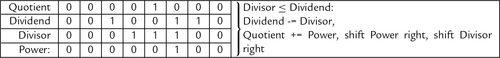

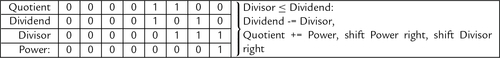

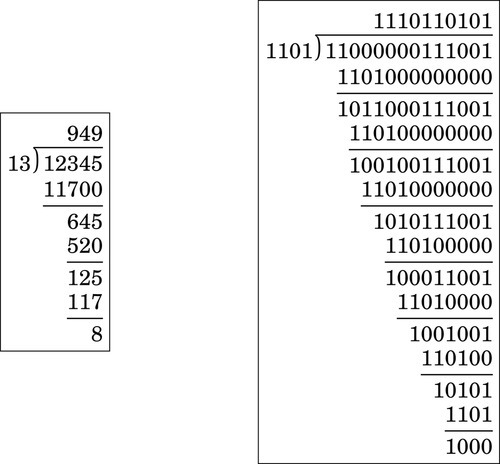

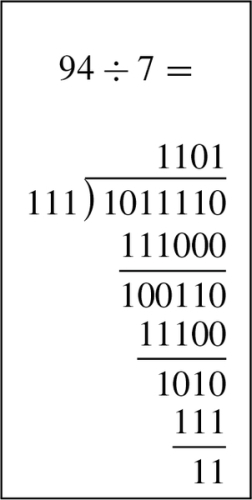

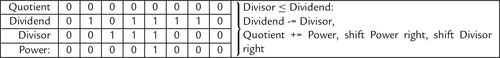

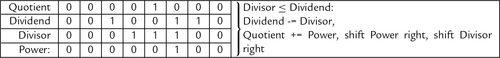

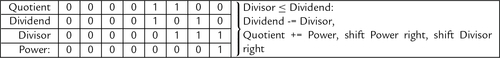

Figure 7.4 Longhand division in decimal and binary 181

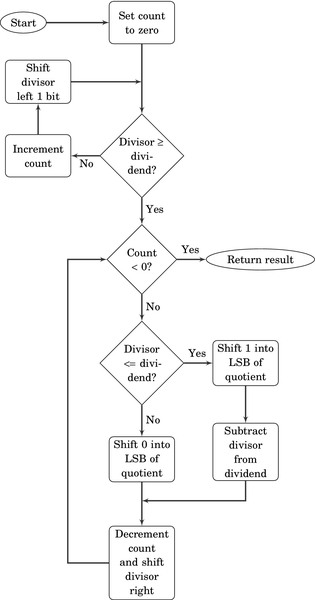

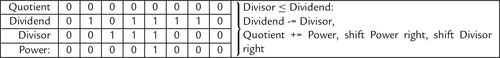

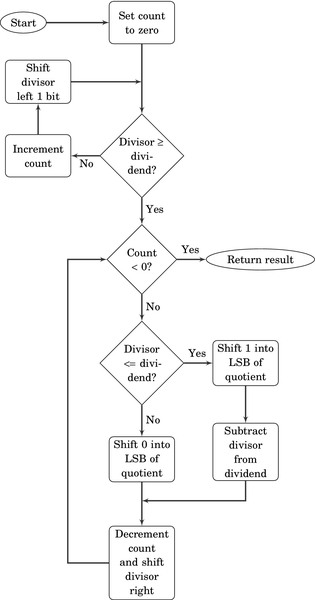

Figure 7.5 Flowchart for binary division 183

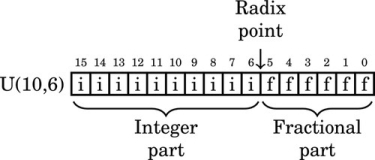

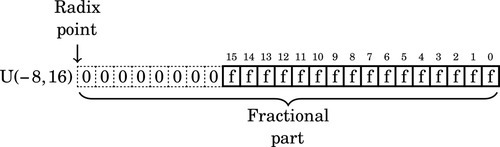

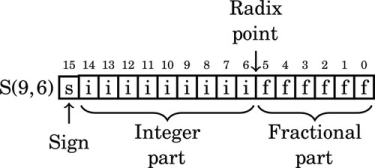

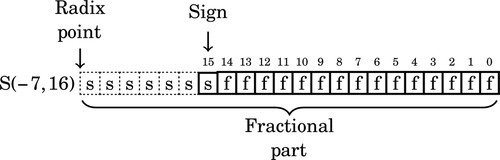

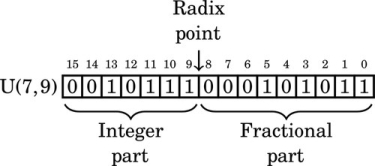

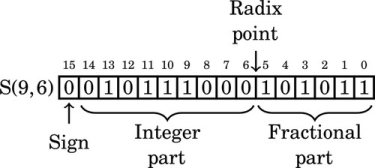

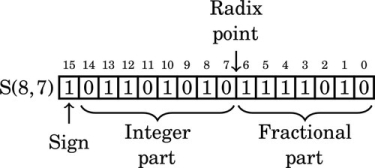

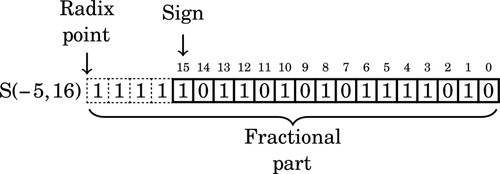

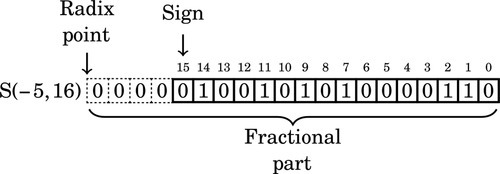

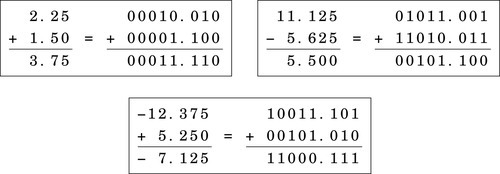

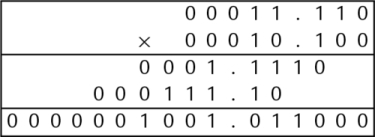

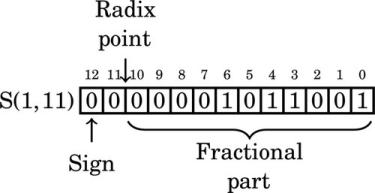

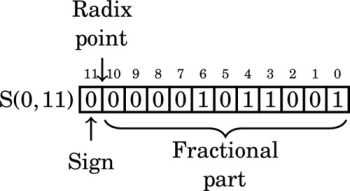

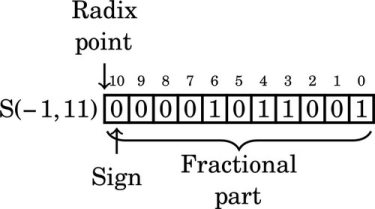

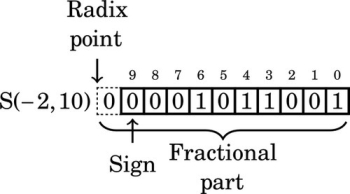

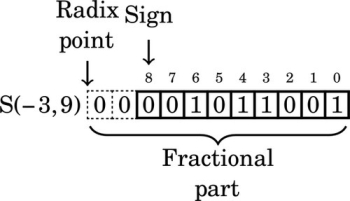

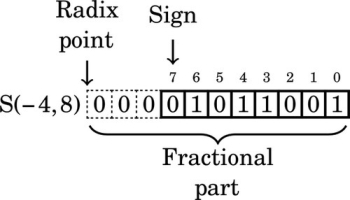

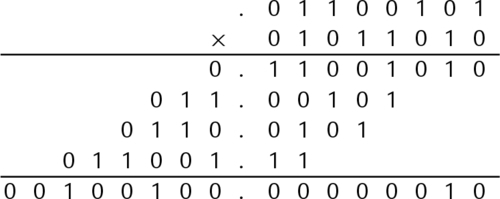

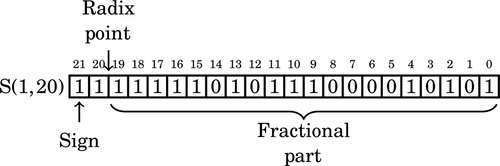

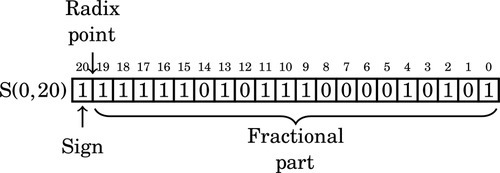

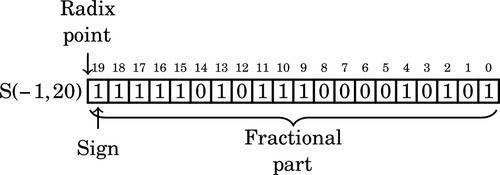

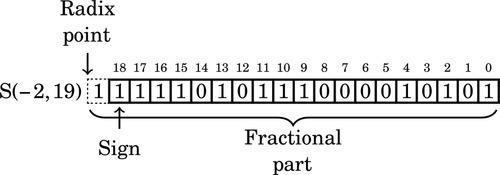

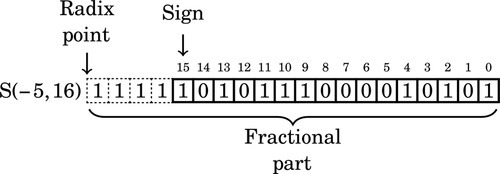

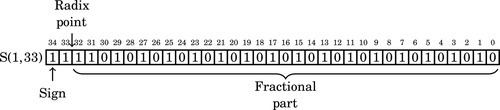

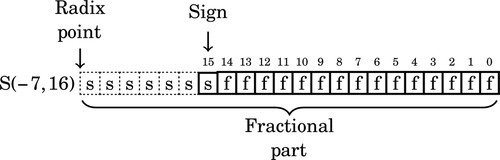

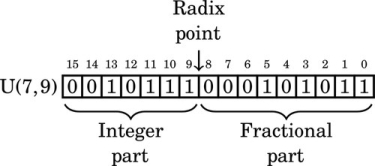

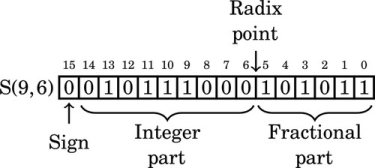

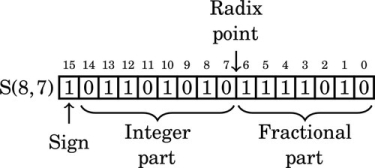

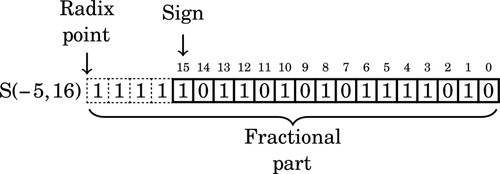

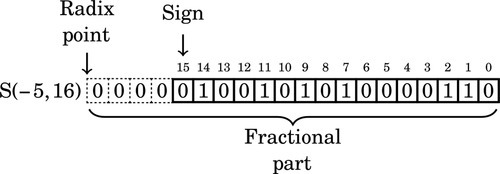

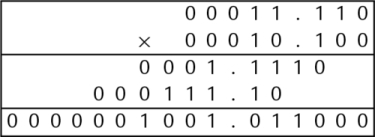

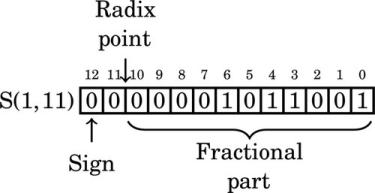

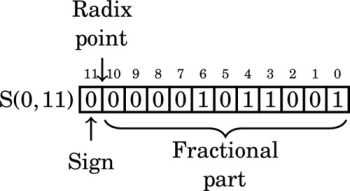

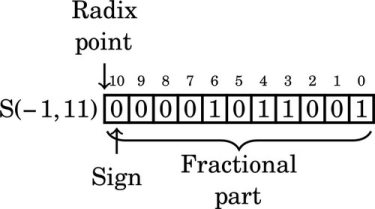

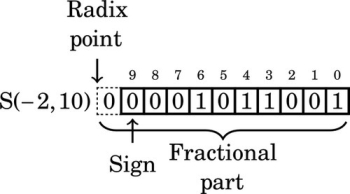

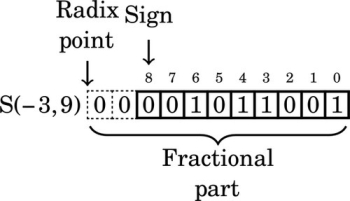

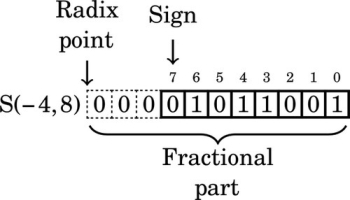

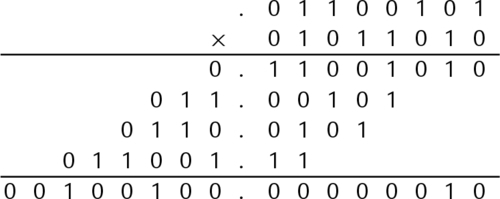

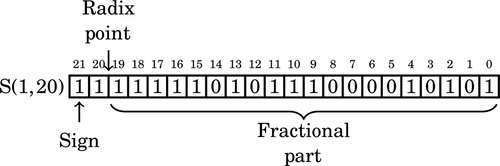

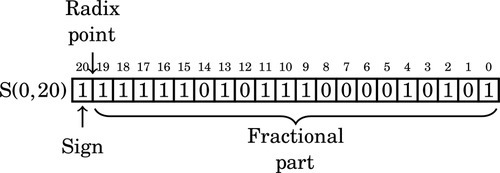

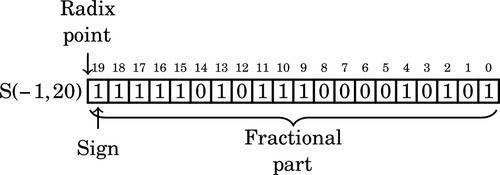

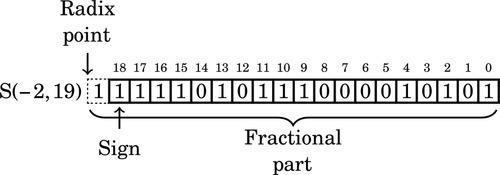

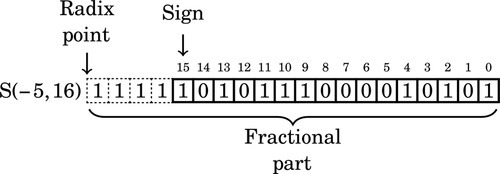

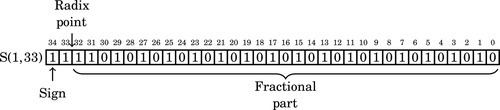

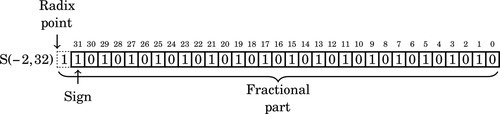

Figure 8.1 Examples of fixed-point signed arithmetic 232

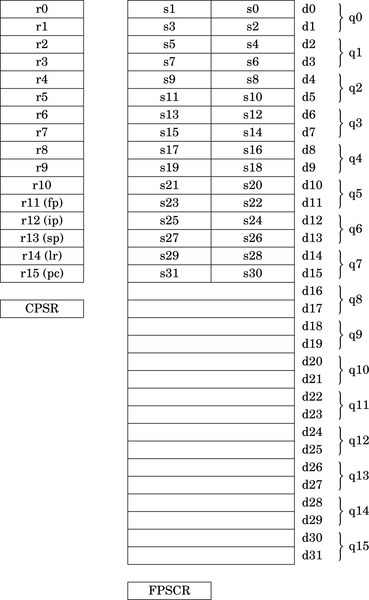

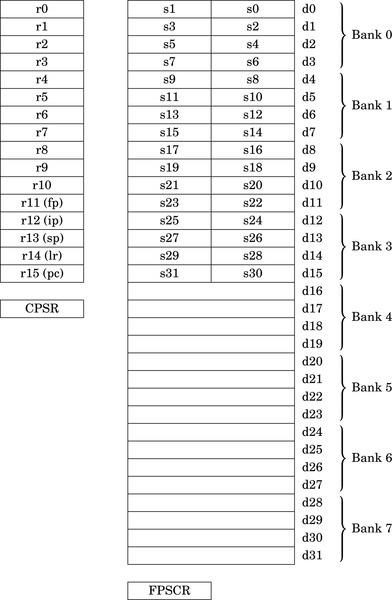

Figure 9.1 ARM integer and vector floating point user program registers 267

Figure 9.2 Bits in the FPSCR 268

Figure 10.1 ARM integer and NEON user program registers 300

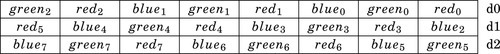

Figure 10.2 Pixel data interleaved in three doubleword registers 302

Figure 10.3 Pixel data de-interleaved in three doubleword registers 303

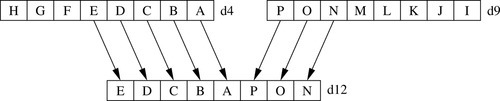

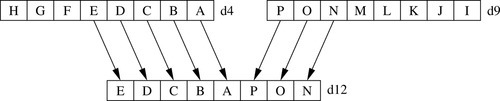

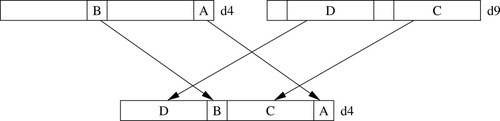

Figure 10.4 Example of vext.8 d12,d4,d9,#5 313

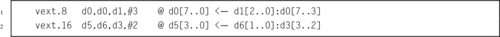

Figure 10.5 Examples of the vrev instruction. (A) vrev16.8 d3,d4; (B) vrev32.16 d8,d9; (C) vrev32.8 d5,d7 315

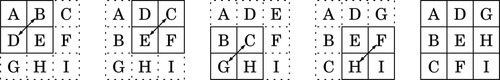

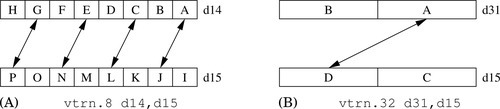

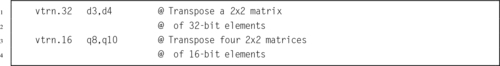

Figure 10.6 Examples of the vtrn instruction. (A) vtrn.8 d14,d15; (B) vtrn.32 d31,d15 316

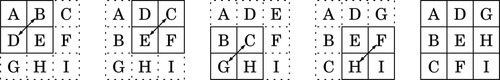

Figure 10.7 Transpose of a 3 × 3 matrix 317

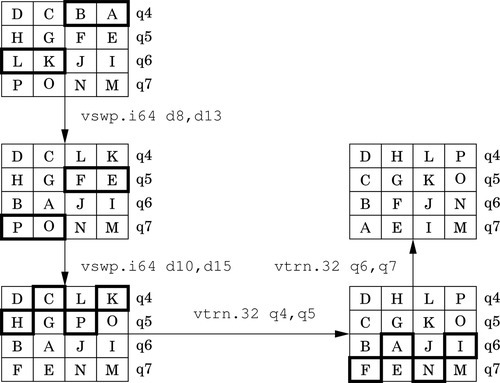

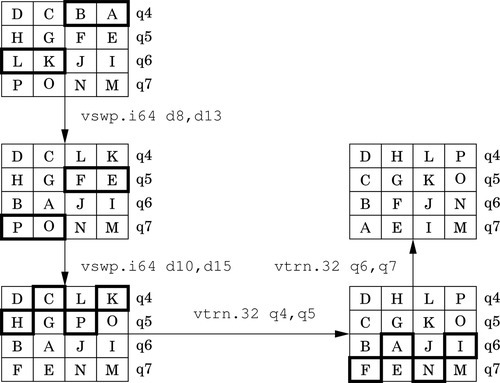

Figure 10.8 Transpose of a 4 × 4 matrix of 32-bit numbers 318

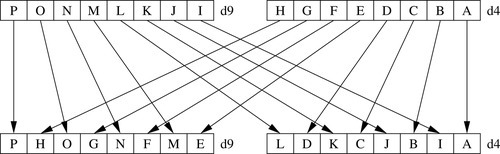

Figure 10.9 Example of vzip.8 d9,d4 320

Figure 10.10 Effects of vsli.32 d4,d9,#6 334

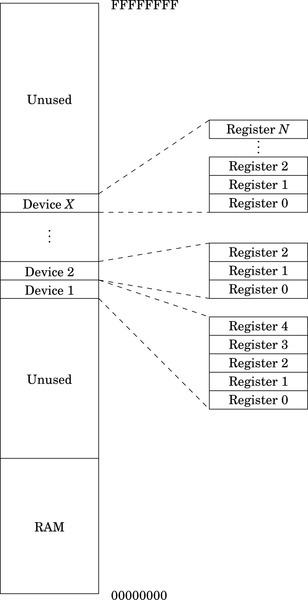

Figure 11.1 Typical hardware address mapping for memory and devices 366

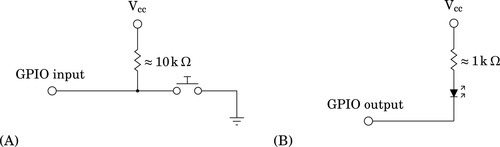

Figure 11.2 GPIO pins being used for input and output. (A) GPIO pin being used as input to read the state of a push-button switch. (B) GPIO pin being used as output to drive an LED 378

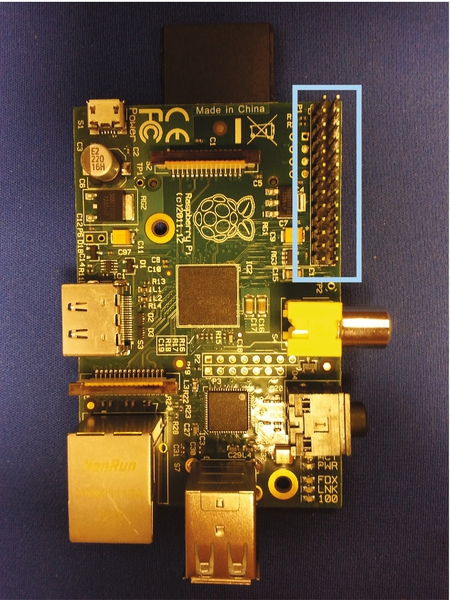

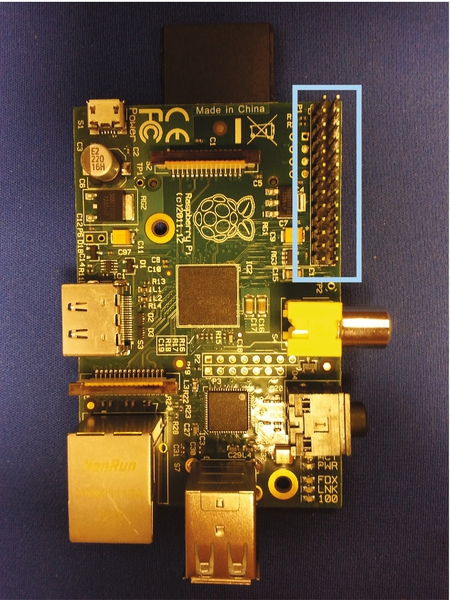

Figure 11.3 The Raspberry Pi expansion header location 383

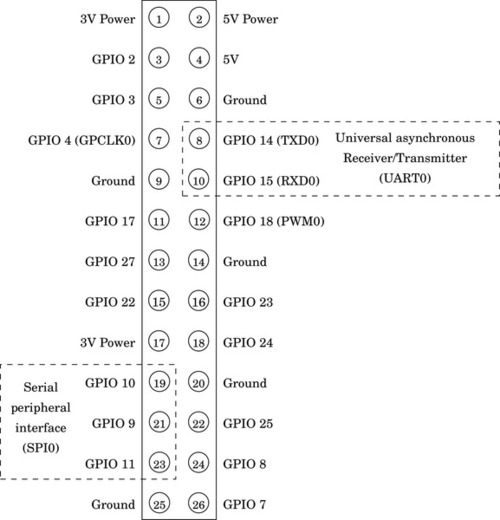

Figure 11.4 The Raspberry Pi expansion header pin assignments 384

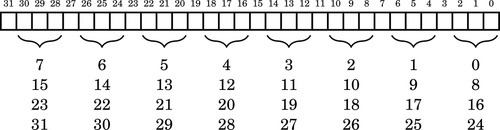

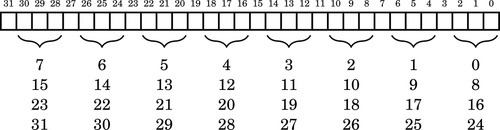

Figure 11.5 Bit-to-pin assignments for PIO control registers 388

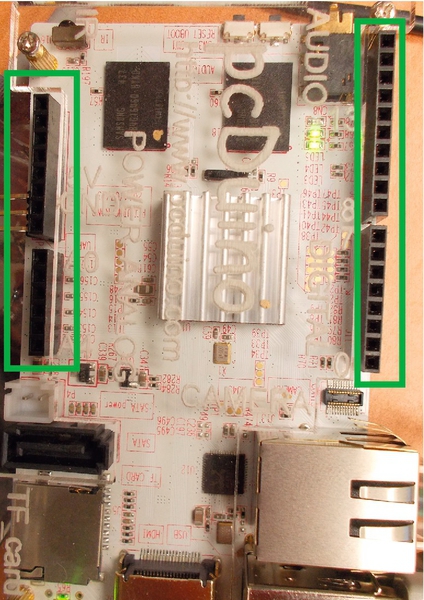

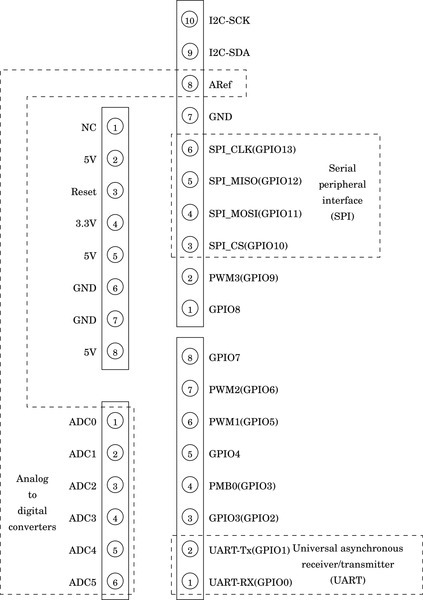

Figure 11.6 The pcDuino header locations 390

Figure 11.7 The pcDuino header pin assignments 391

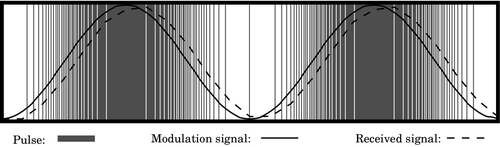

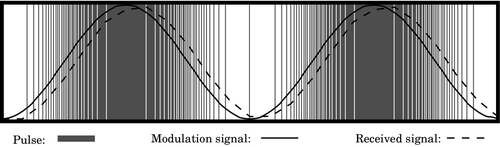

Figure 12.1 Pulse density modulation 396

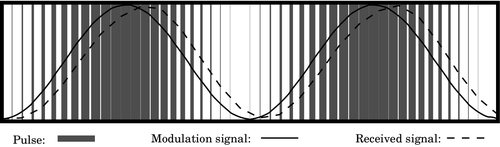

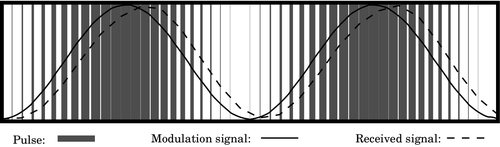

Figure 12.2 Pulse width modulation 397

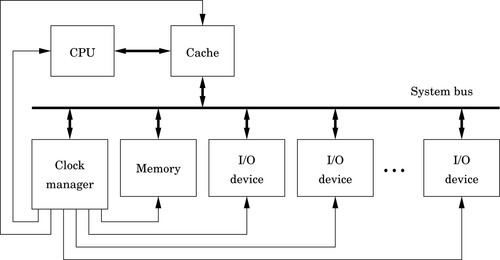

Figure 13.1 Typical system with a clock management device 406

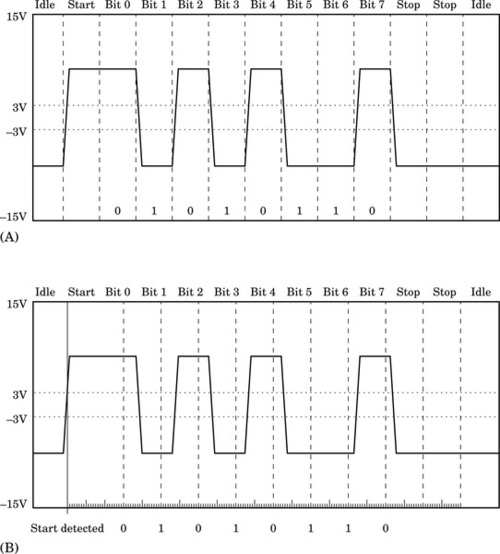

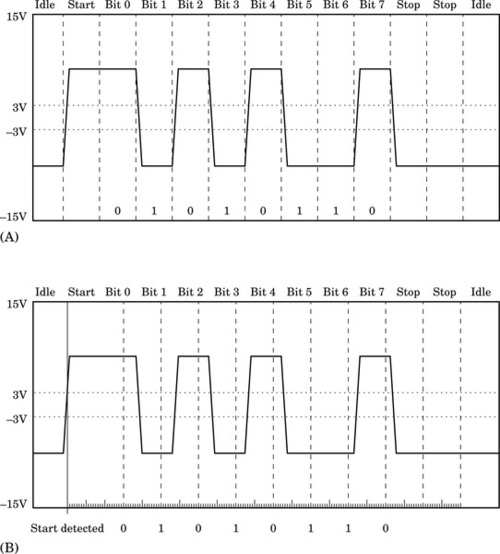

Figure 13.2 Transmitter and receiver timings for two UARTS. (A) Waveform of a UART transmitting a byte. (B) Timing of UART receiving a byte 411

Figure 14.1 The ARM process status register 433

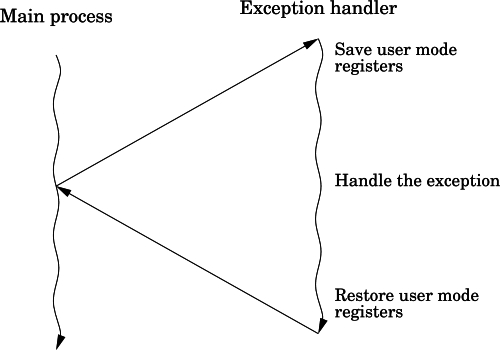

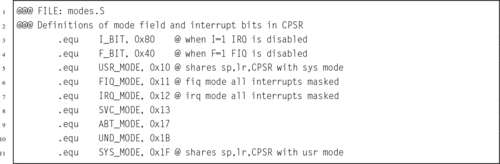

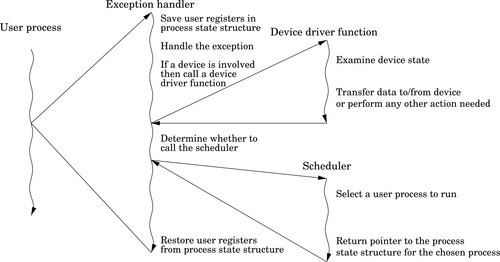

Figure 14.2 Basic exception processing 436

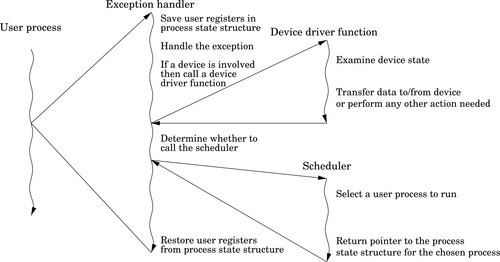

Figure 14.3 Exception processing with multiple user processes 437

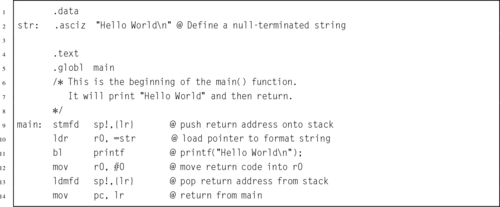

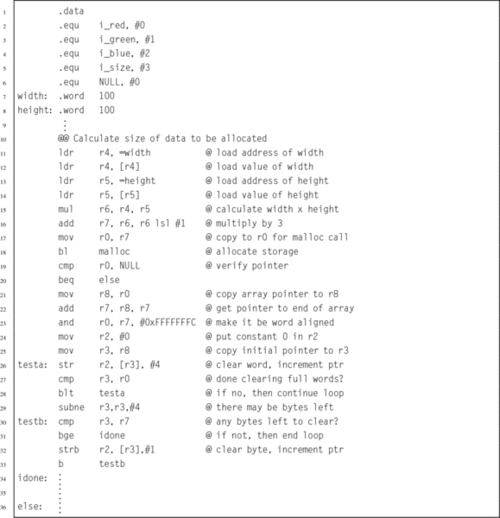

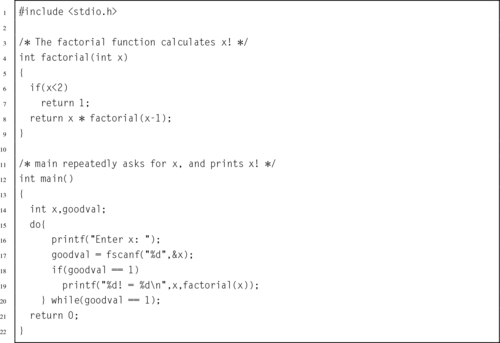

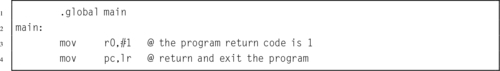

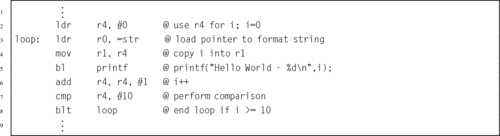

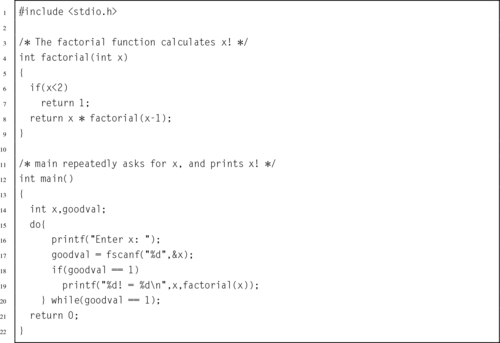

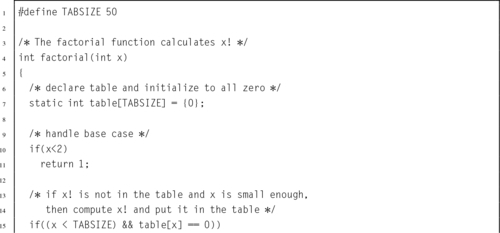

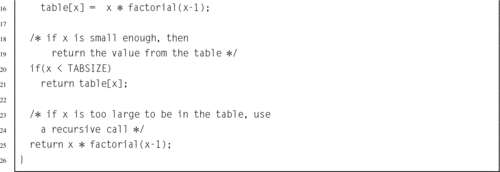

Listing 2.1 “Hello World” program in ARM assembly 36

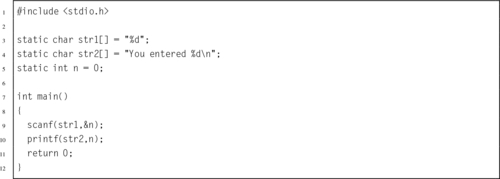

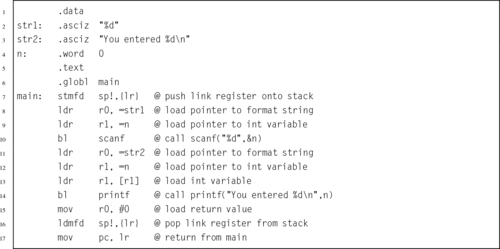

Listing 2.2 “Hello World” program in C 37

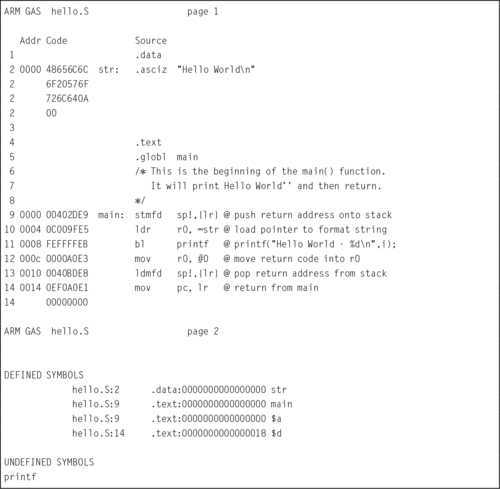

Listing 2.3 “Hello World” assembly Listing 39

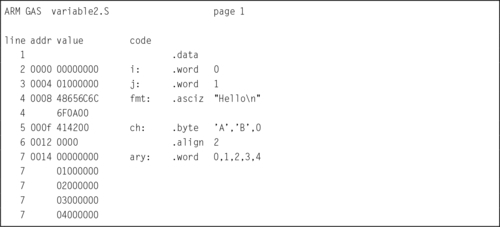

Listing 2.4 A Listing with mis-aligned data 43

Listing 2.5 A Listing with properly aligned data 45

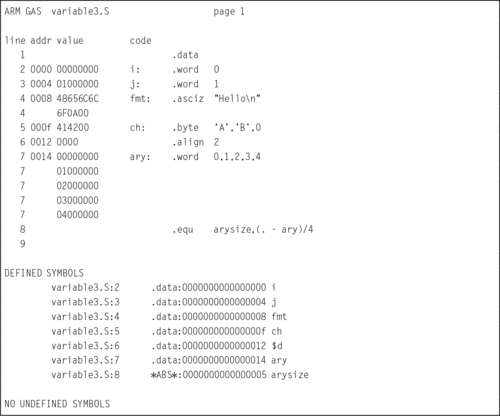

Listing 2.6 Defining a symbol for the number of elements in an array 47

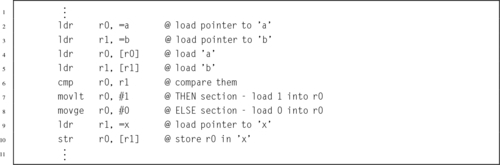

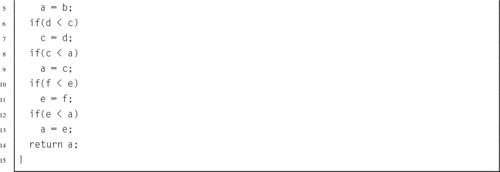

Listing 5.1 Selection in C 101

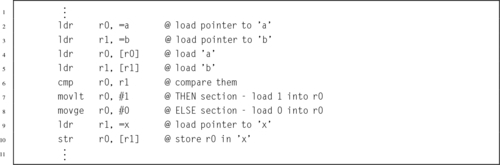

Listing 5.2 Selection in ARM assembly using conditional execution 102

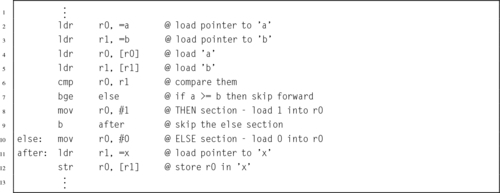

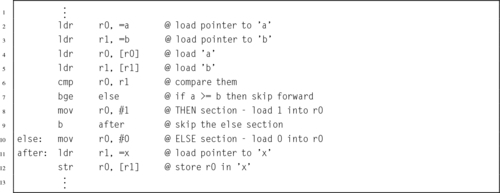

Listing 5.3 Selection in ARM assembly using branch instructions 102

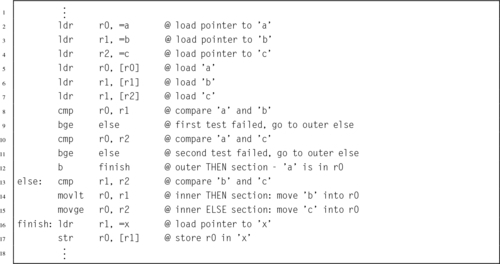

Listing 5.4 Complex selection in C 103

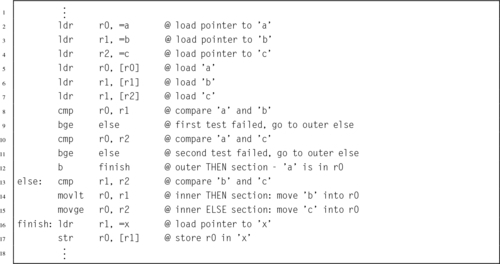

Listing 5.5 Complex selection in ARM assembly 104

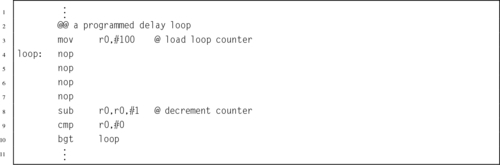

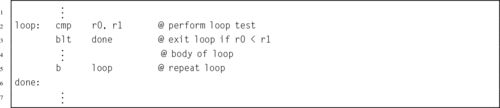

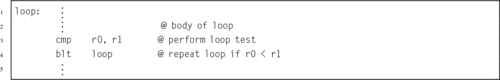

Listing 5.6 Unconditional loop in ARM assembly 105

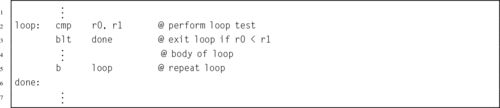

Listing 5.7 Pre-test loop in ARM assembly 105

Listing 5.8 Post-test loop in ARM assembly 106

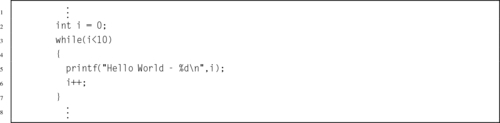

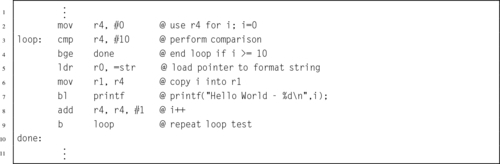

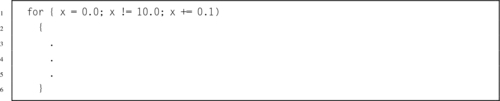

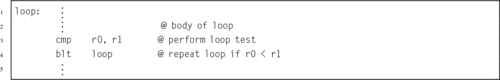

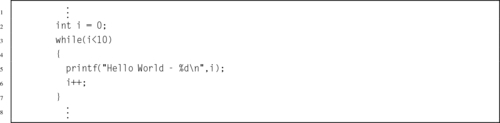

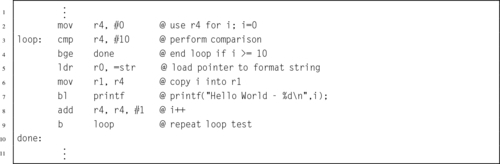

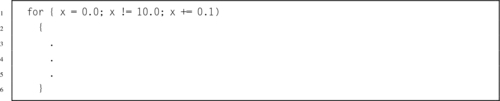

Listing 5.9 for loop in C 106

Listing 5.10 for loop rewritten as a pre-test loop in C 107

Listing 5.11 Pre-test loop in ARM assembly 107

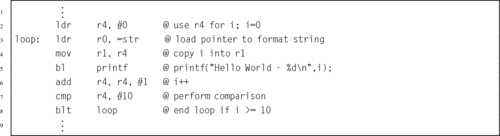

Listing 5.12 for loop rewritten as a post-test loop in C 108

Listing 5.13 Post-test loop in ARM assembly 108

Listing 5.14 Calling scanf and printf in C 111

Listing 5.15 Calling scanf and printf in ARM assembly 111

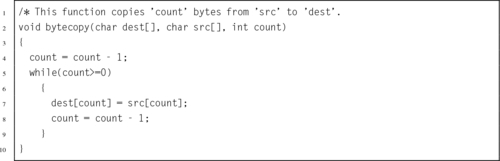

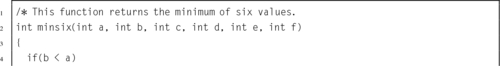

Listing 5.16 Simple function call in C 114

Listing 5.17 Simple function call in ARM assembly 114

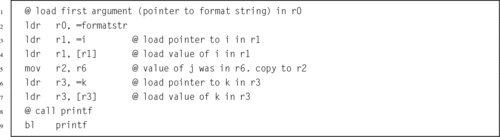

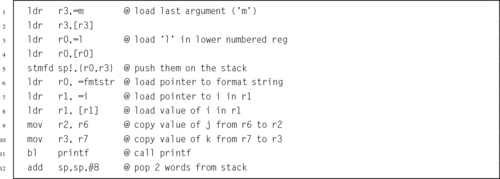

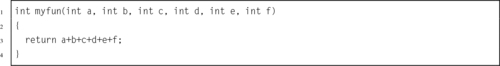

Listing 5.18 A larger function call in C 114

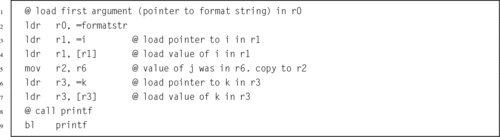

Listing 5.19 A larger function call in ARM assembly 115

Listing 5.20 A function call using the stack in C 115

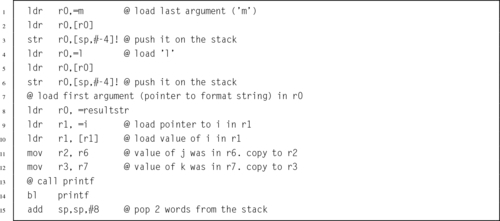

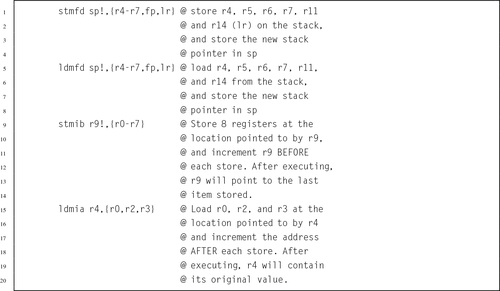

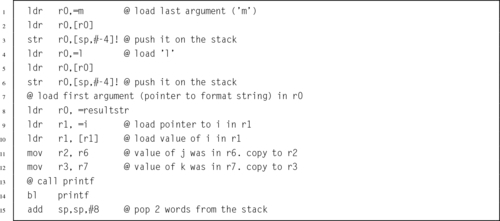

Listing 5.21 A function call using the stack in ARM assembly 116

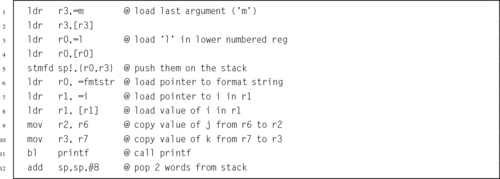

Listing 5.22 A function call using stm to push arguments onto the stack 116

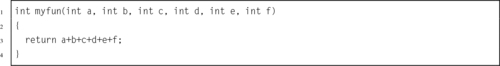

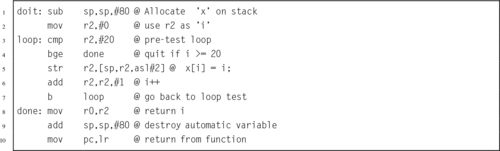

Listing 5.23 A small function in C 118

Listing 5.24 A small function in ARM assembly 118

Listing 5.25 A small C function with a register variable 119

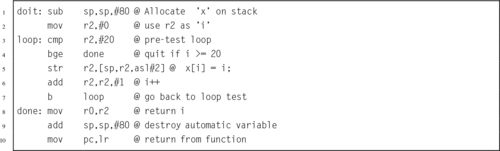

Listing 5.26 Automatic variables in ARM assembly 119

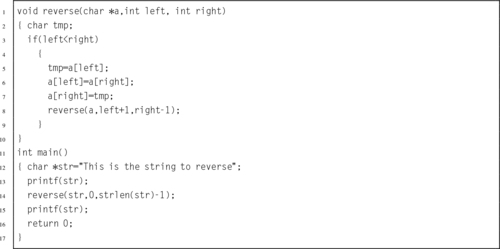

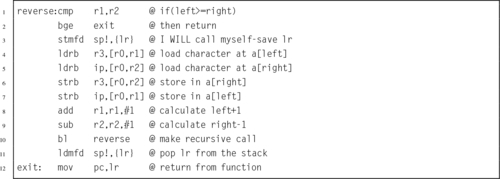

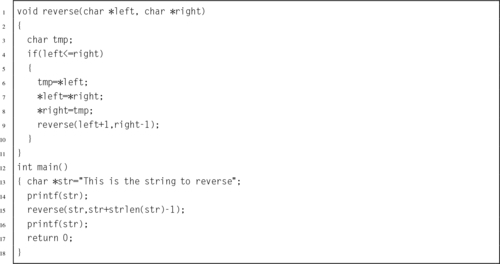

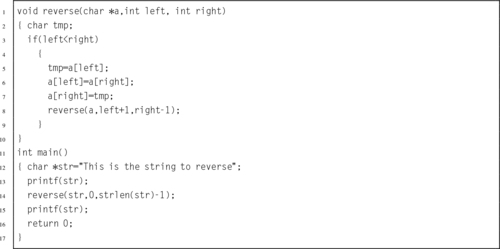

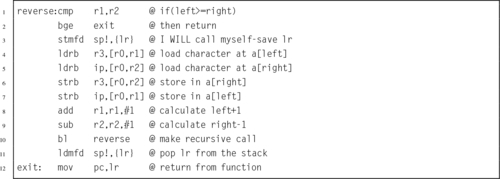

Listing 5.27 A C program that uses recursion to reverse a string 120

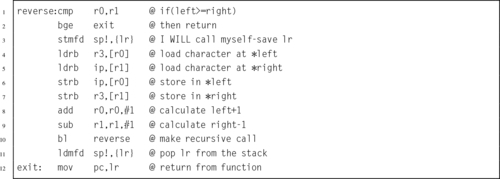

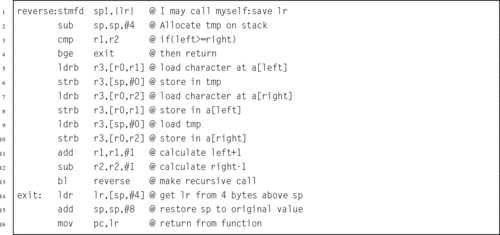

Listing 5.28 ARM assembly implementation of the reverse function 121

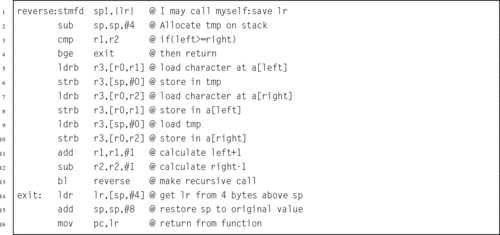

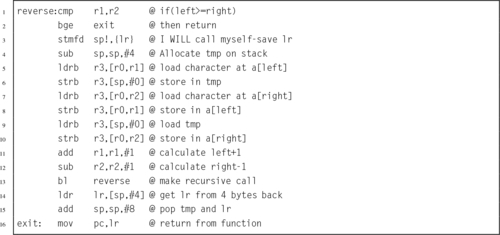

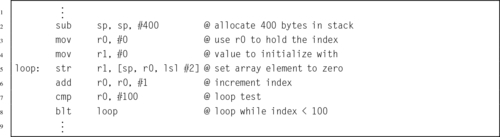

Listing 5.29 Better implementation of the reverse function 122

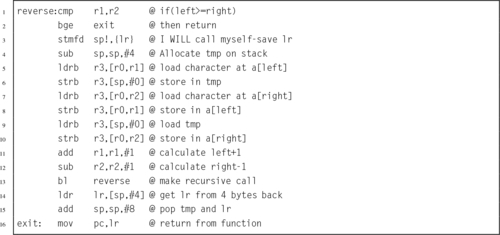

Listing 5.30 Even better implementation of the reverse function 122

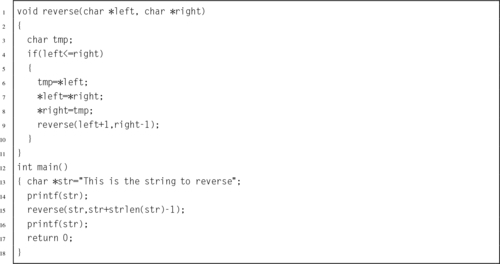

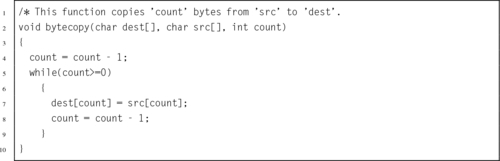

Listing 5.31 String reversing in C using pointers 123

Listing 5.32 String reversing in assembly using pointers 123

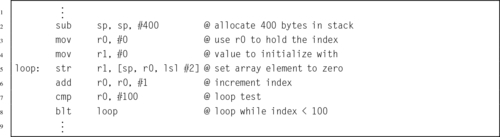

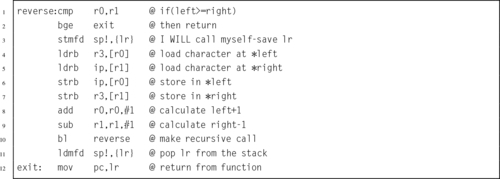

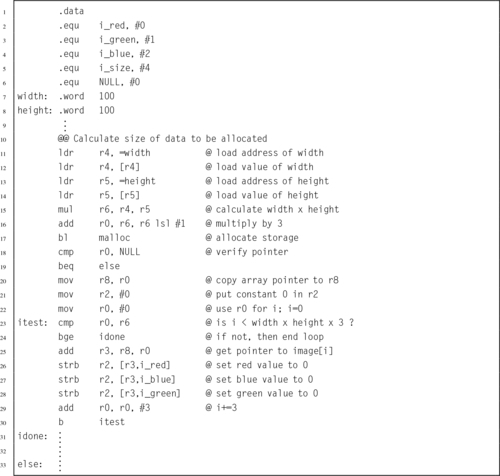

Listing 5.33 Initializing an array of integers in C 124

Listing 5.34 Initializing an array of integers in assembly 125

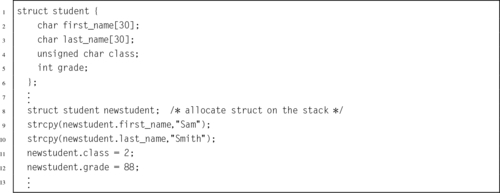

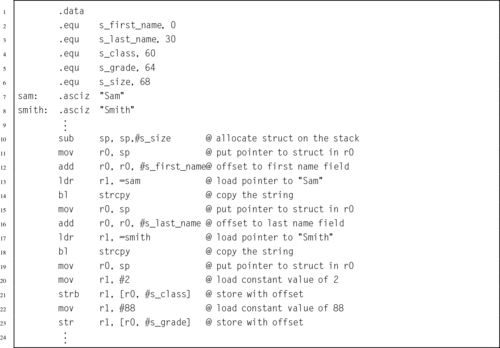

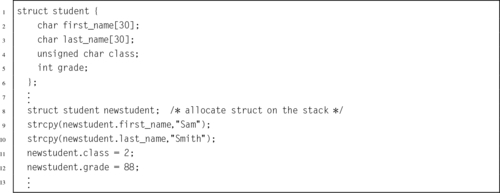

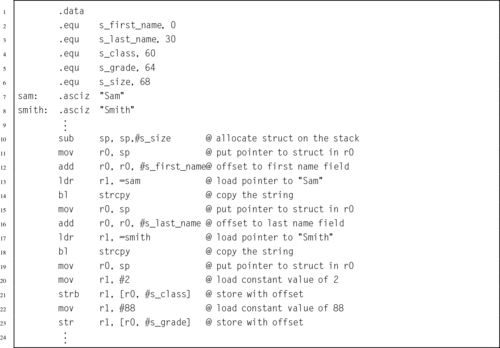

Listing 5.35 Initializing a structured data type in C 125

Listing 5.36 Initializing a structured data type in ARM assembly 126

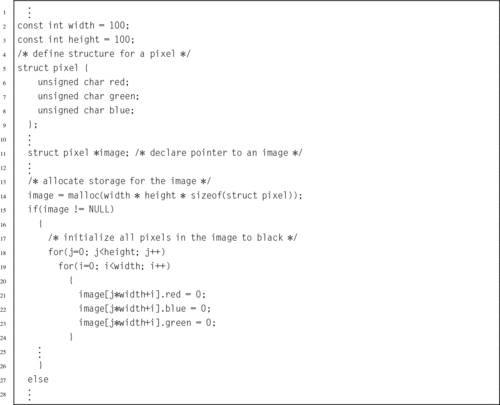

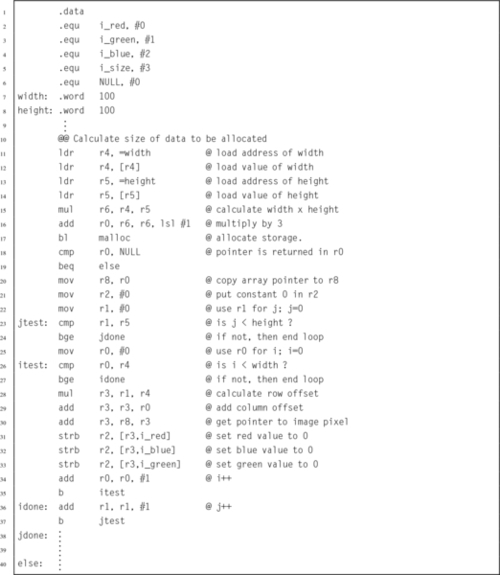

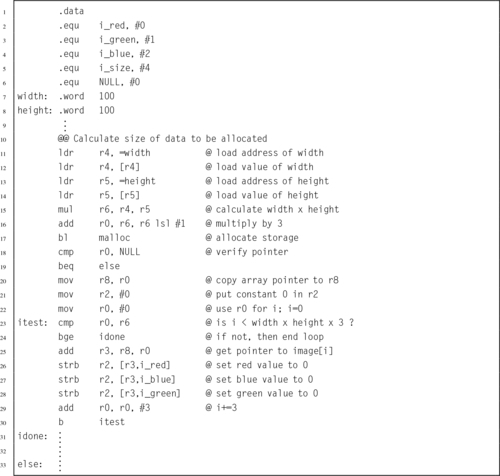

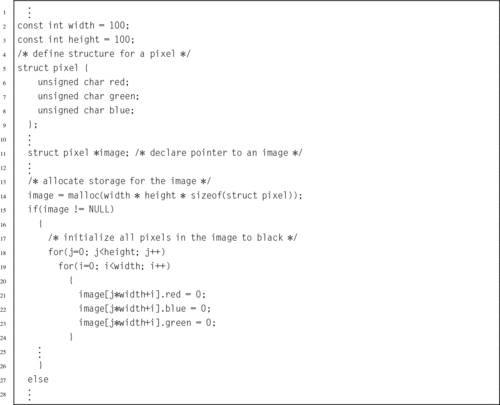

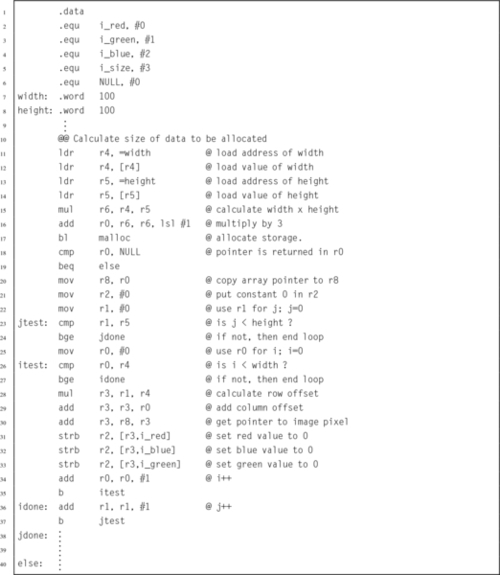

Listing 5.37 Initializing an array of structured data in C 127

Listing 5.38 Initializing an array of structured data in assembly 128

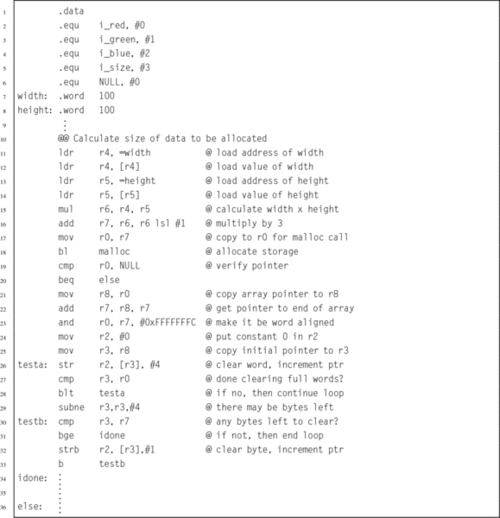

Listing 5.39 Improved initialization in assembly 129

Listing 5.40 Very efficient initialization in assembly 130

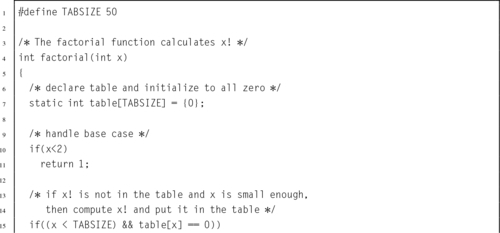

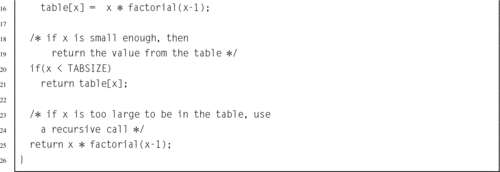

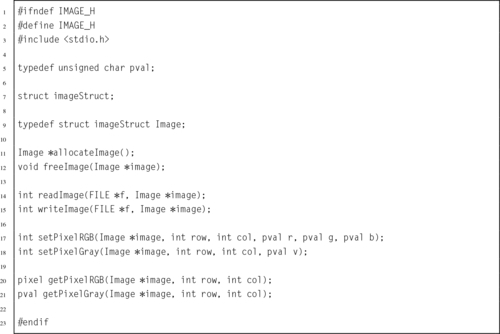

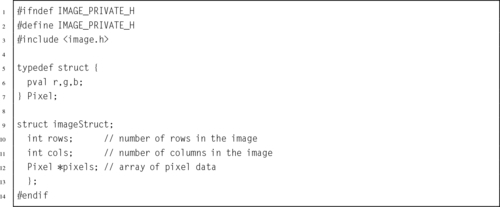

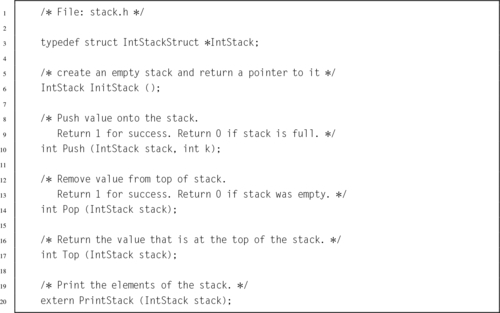

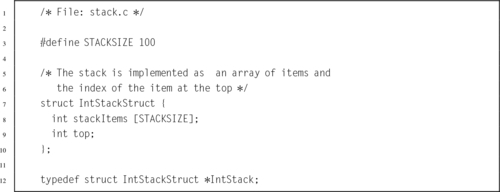

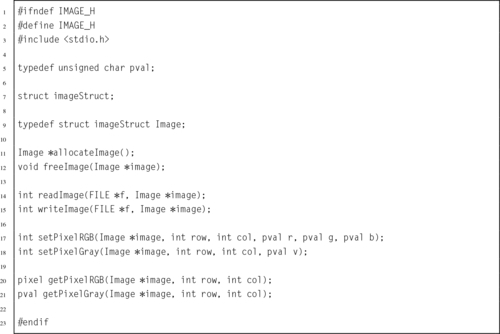

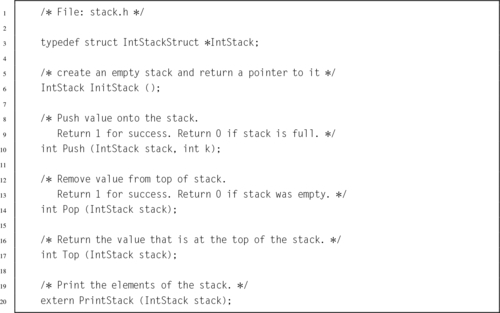

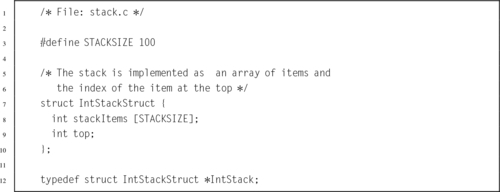

Listing 6.1 Definition of an Abstract Data Type in a C header file 138

Listing 6.2 Definition of the image structure may be hidden in a separate header file 139

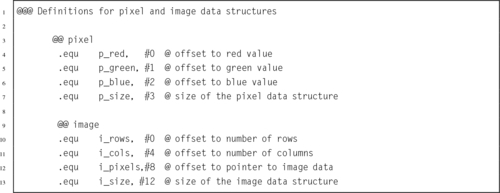

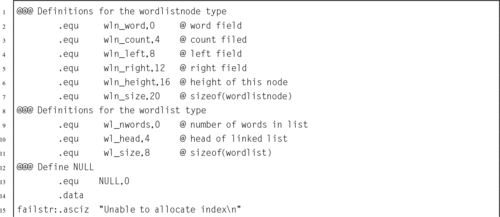

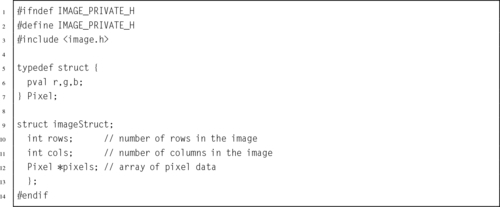

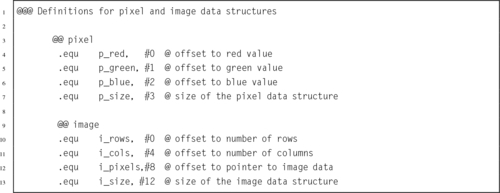

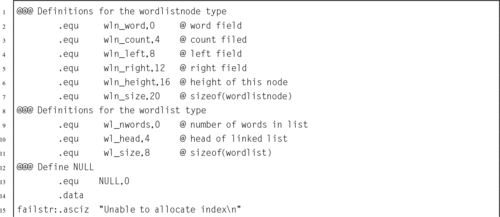

Listing 6.3 Definition of an ADT in Assembly 140

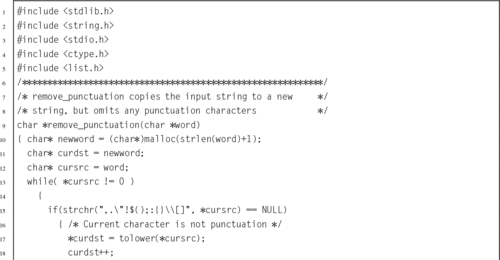

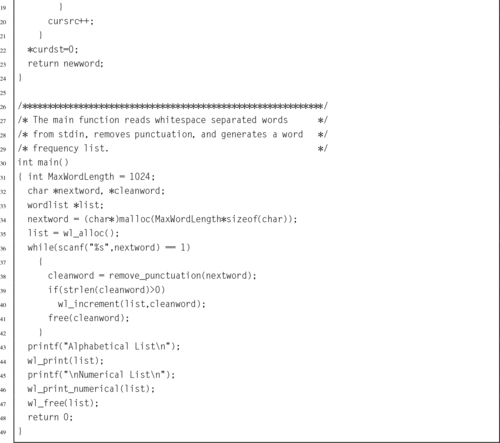

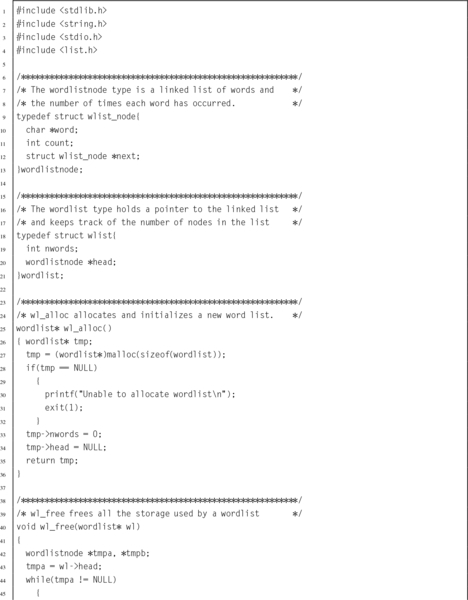

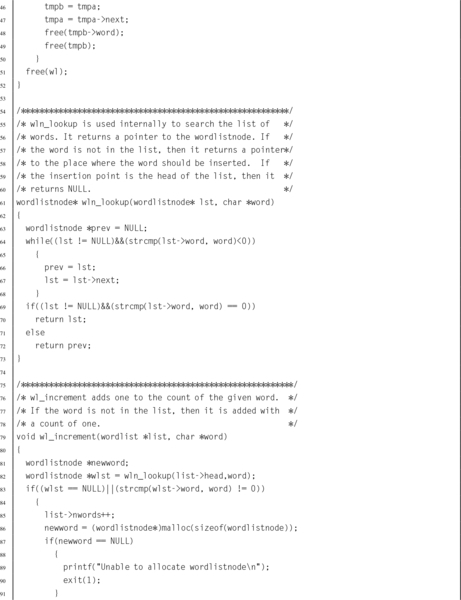

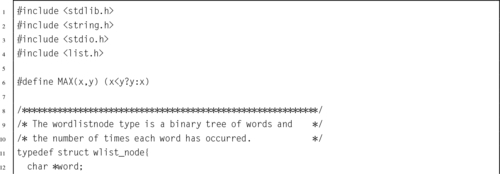

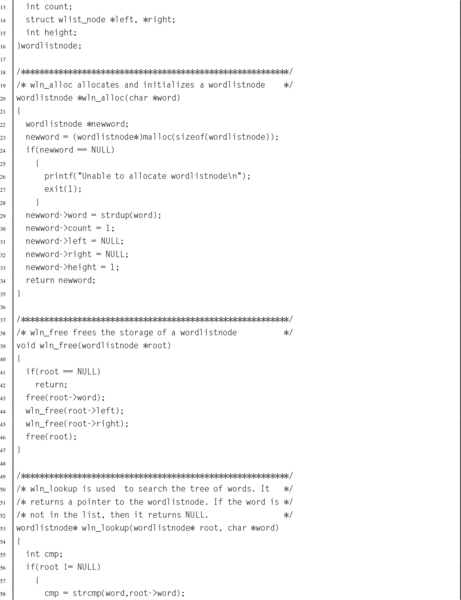

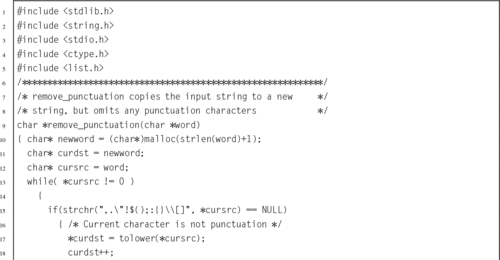

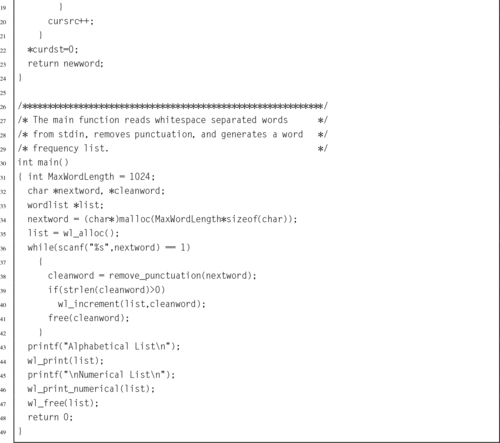

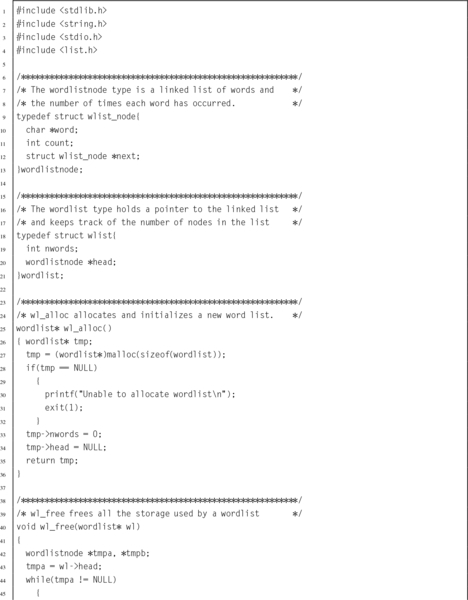

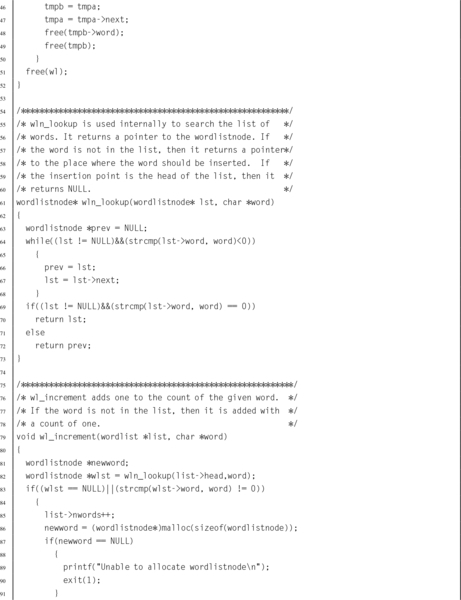

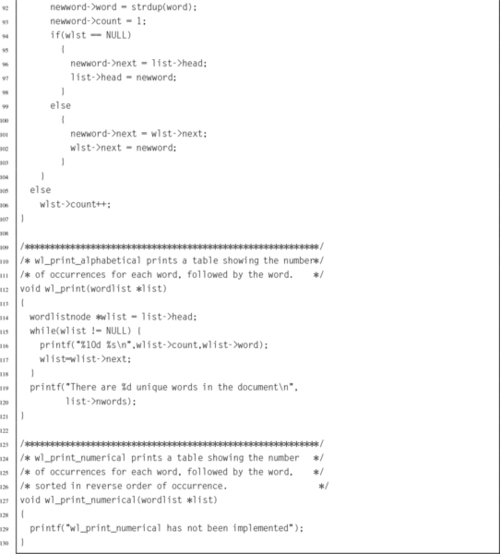

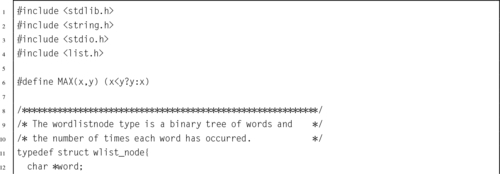

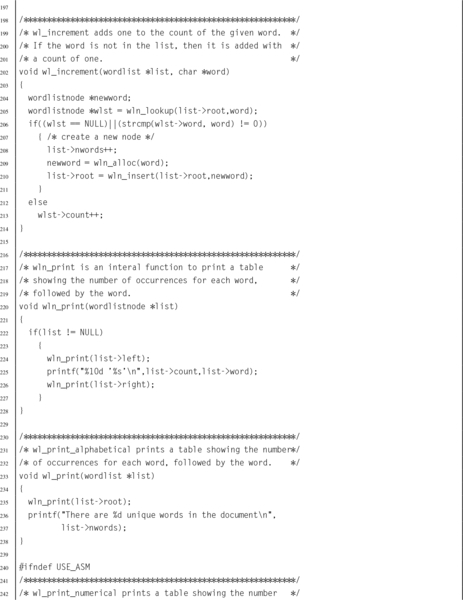

Listing 6.4 C program to compute word frequencies 140

Listing 6.5 C header for the wordlist ADT 142

Listing 6.6 C implementation of the wordlist ADT 143

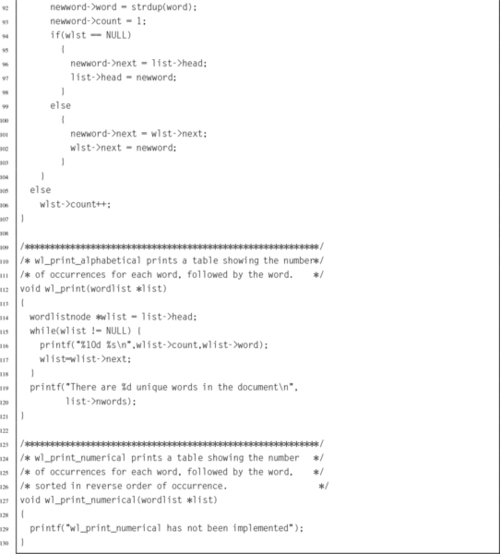

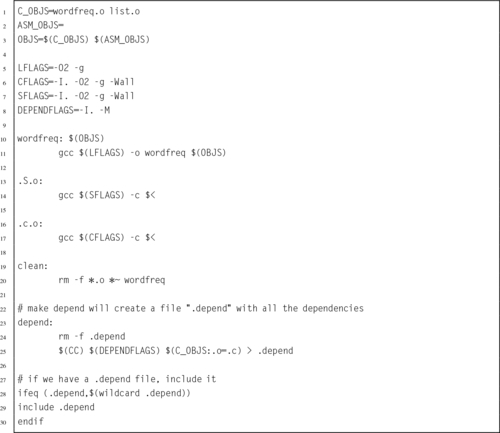

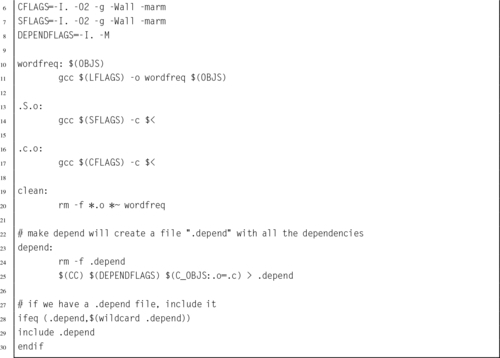

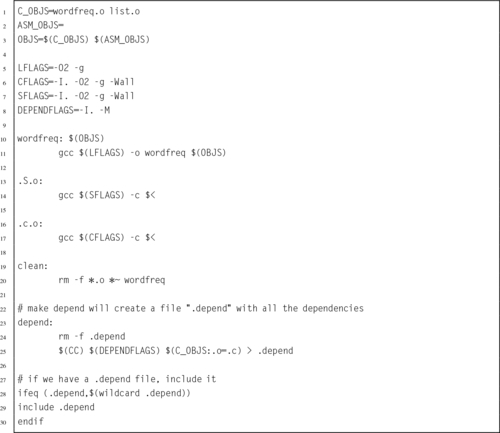

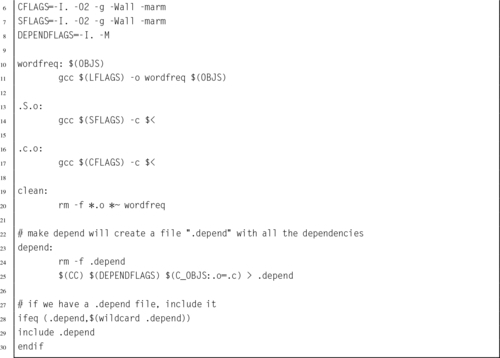

Listing 6.7 Makefile for the wordfreq program 146

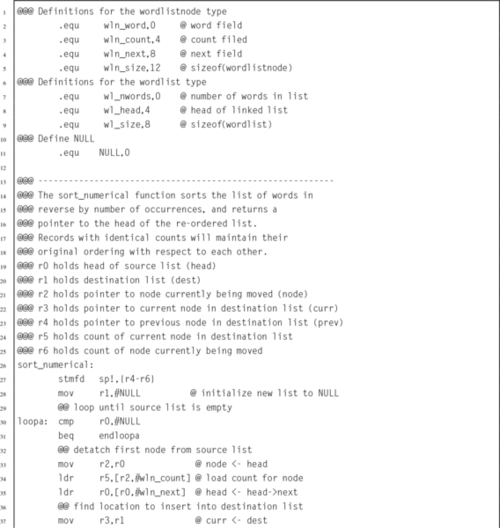

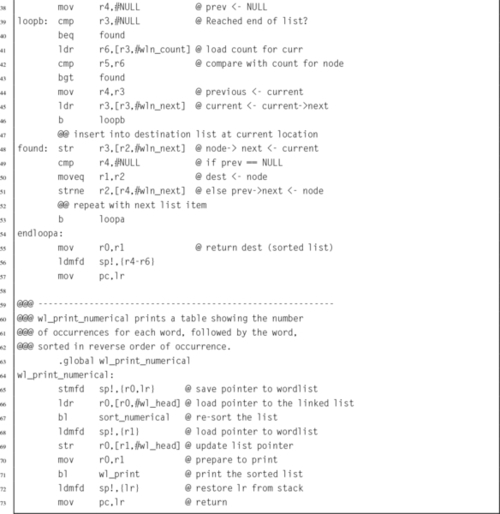

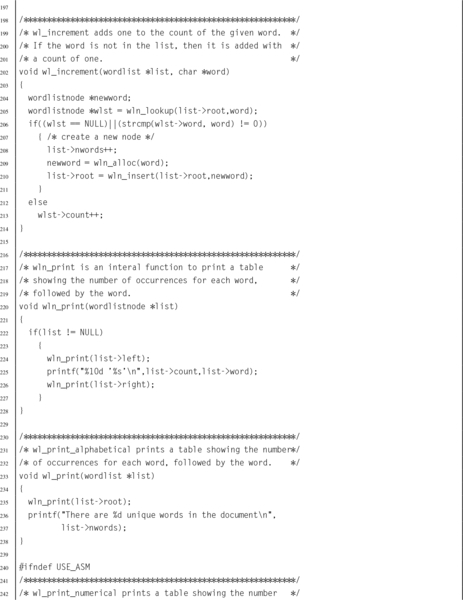

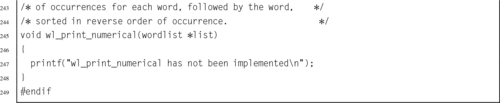

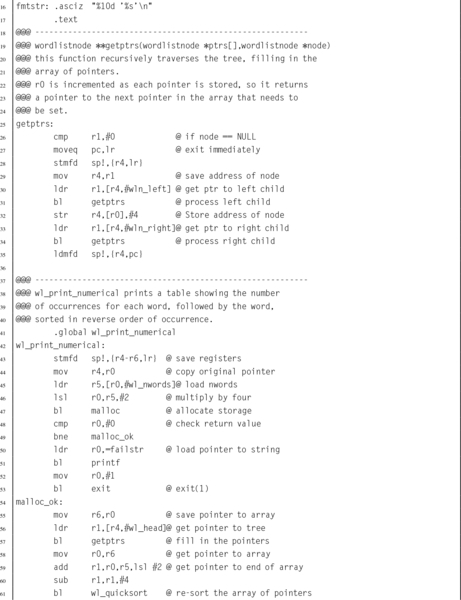

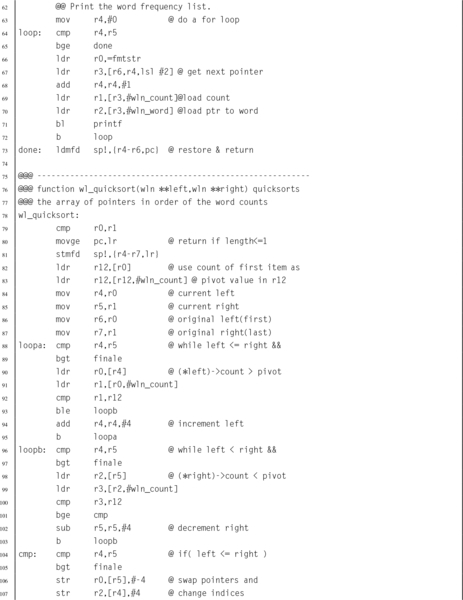

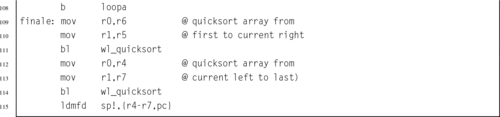

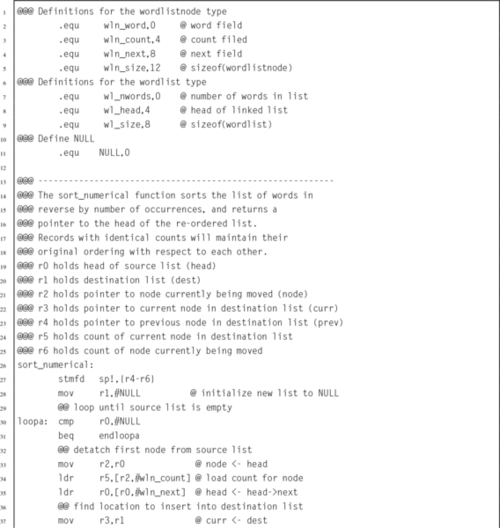

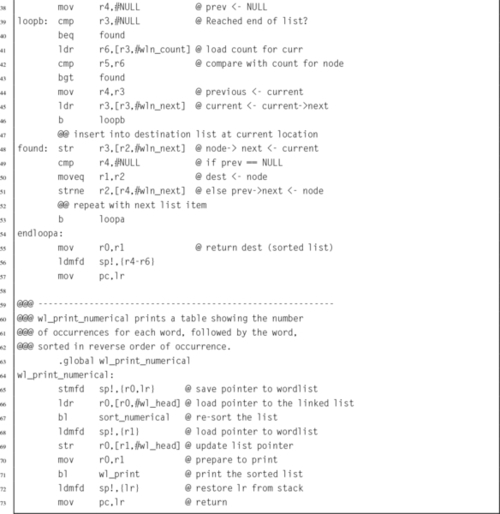

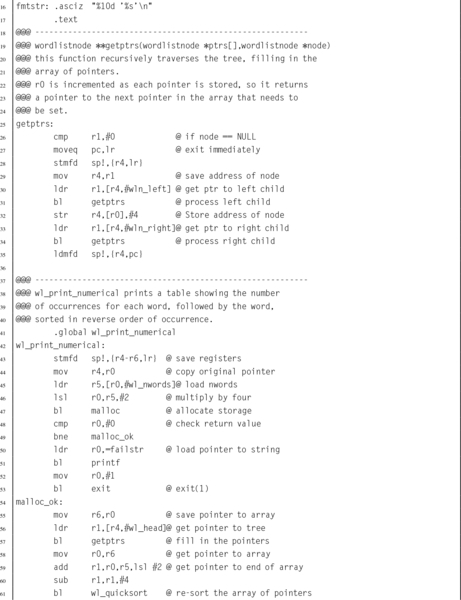

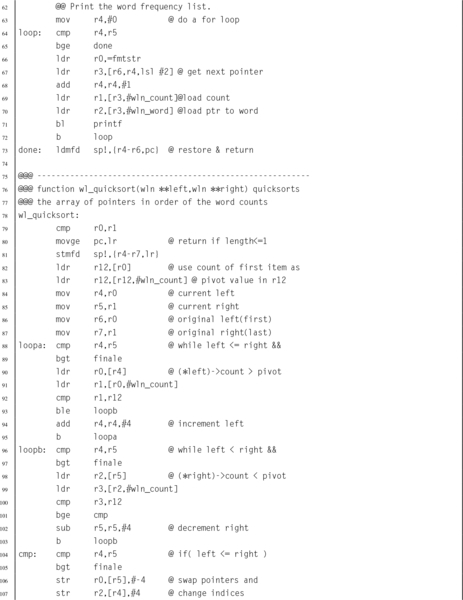

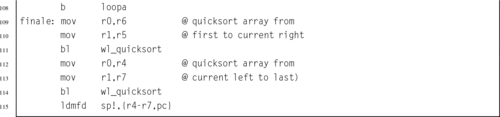

Listing 6.8 ARM assembly implementation of wl_print_numerical() 148

Listing 6.9 Revised makefile for the wordfreq program 149

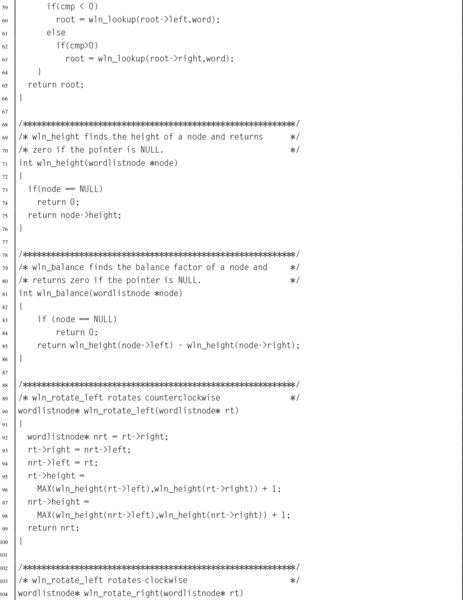

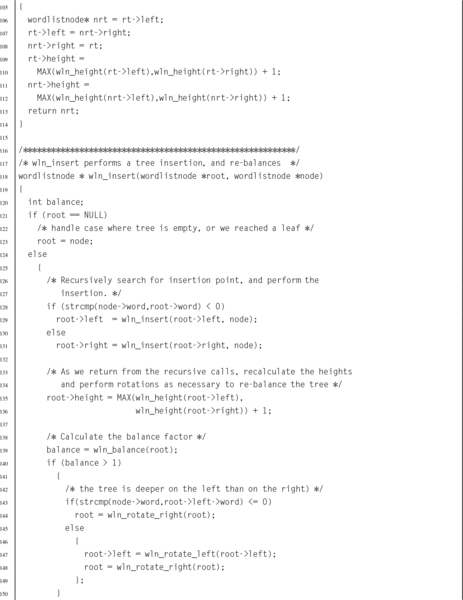

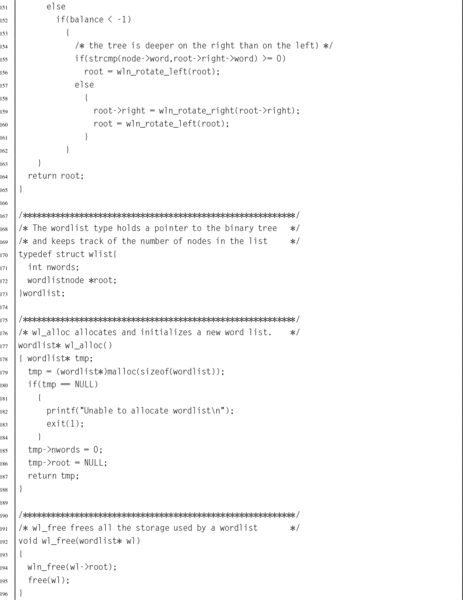

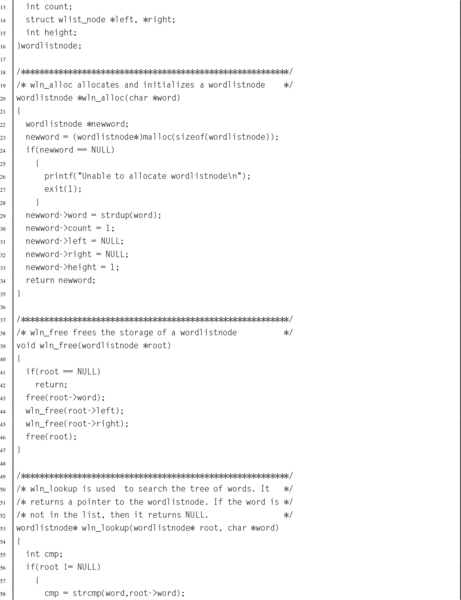

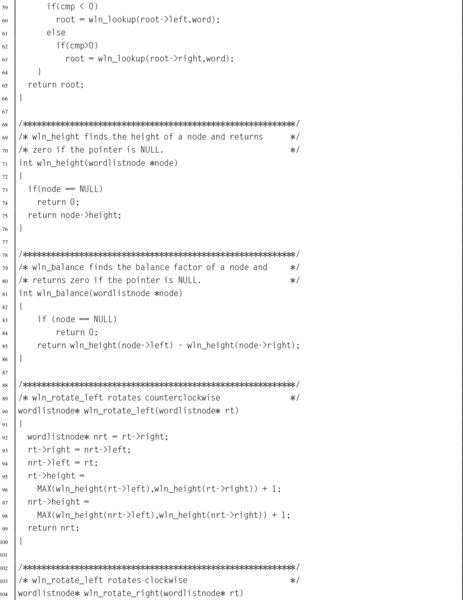

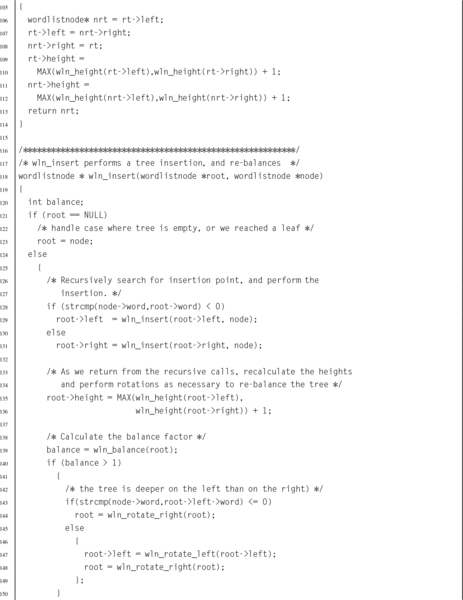

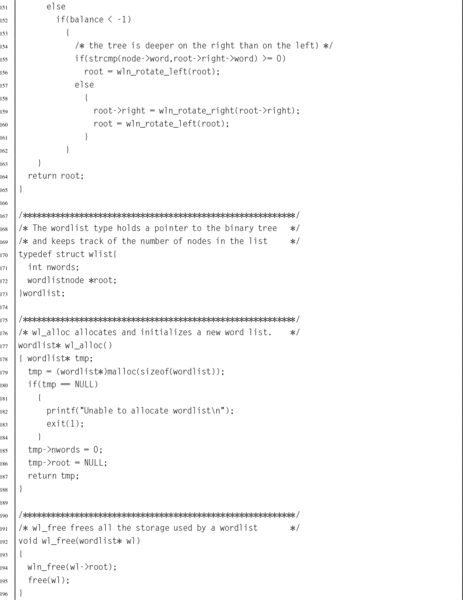

Listing 6.10 C implementation of the wordlist ADT using a tree 151

Listing 6.11 ARM assembly implementation of wl_print_numerical() with a tree 158

Listing 7.1 ARM assembly code for adding two 64 bit numbers 176

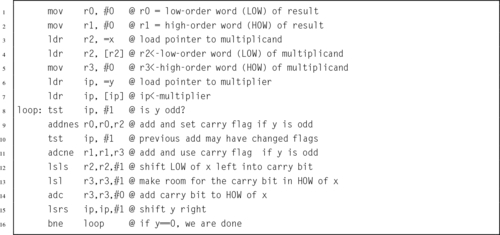

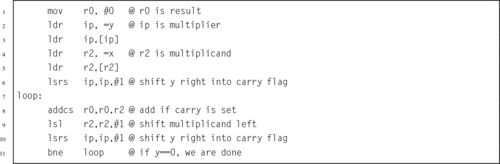

Listing 7.2 ARM assembly code for multiplication with a 64 bit result 176

Listing 7.3 ARM assembly code for multiplication with a 32 bit result 177

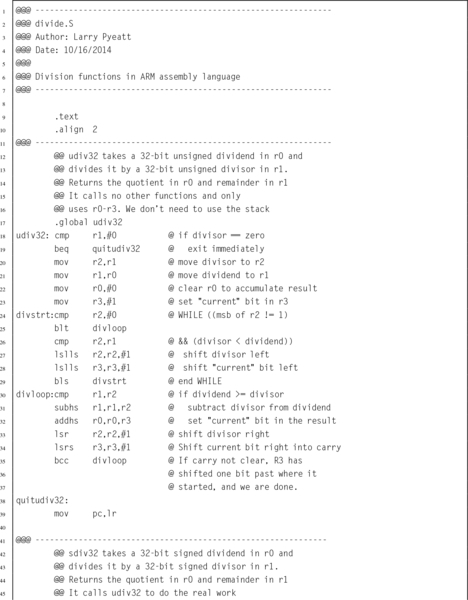

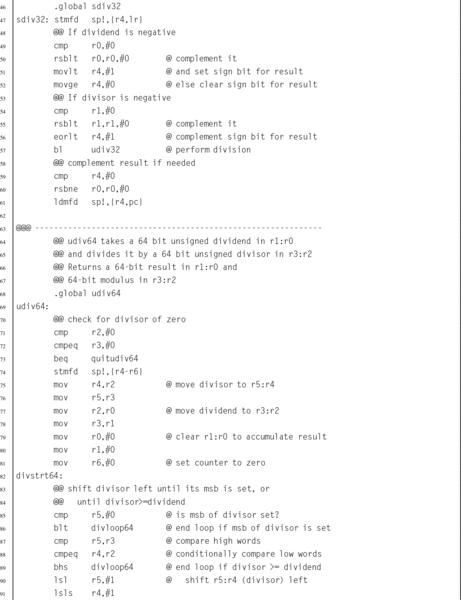

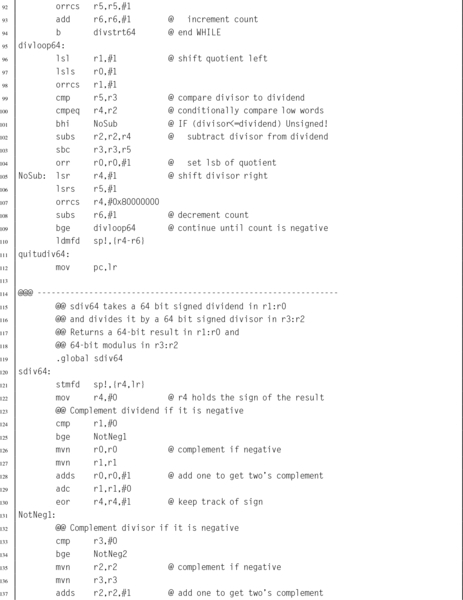

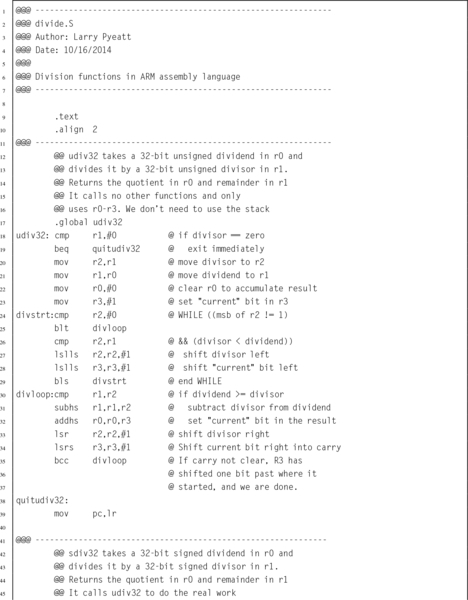

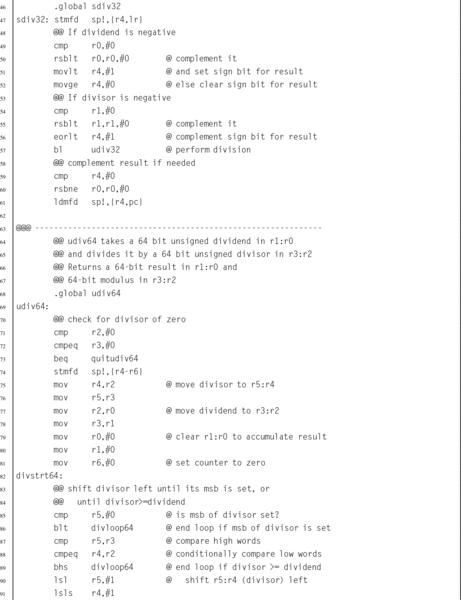

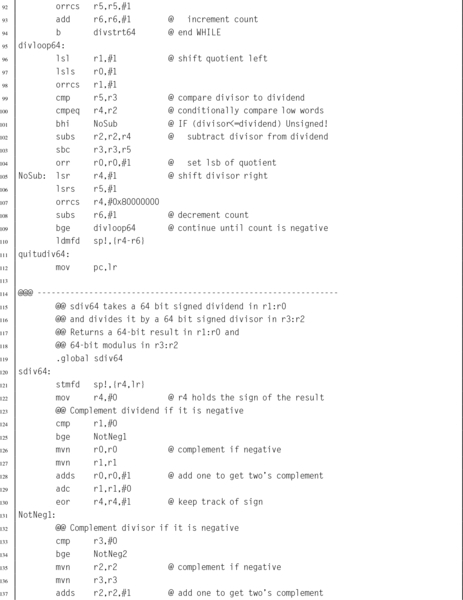

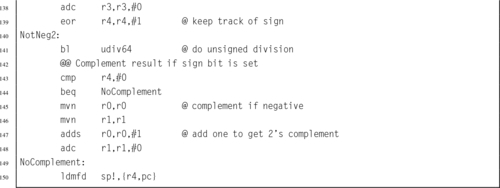

Listing 7.4 ARM assembly implementation of signed and unsigned 32-bit and 64-bit division functions 187

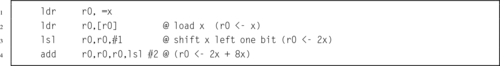

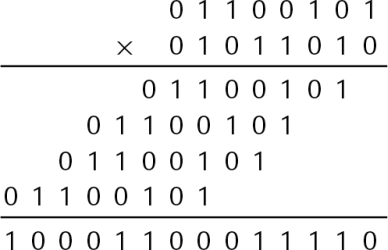

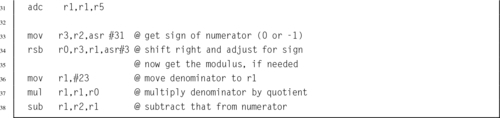

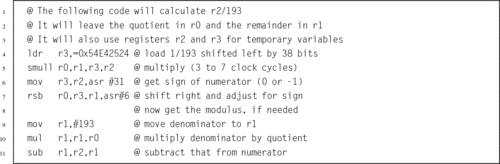

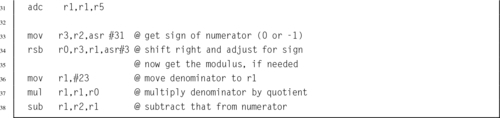

Listing 7.5 ARM assembly code for division by constant 193 192

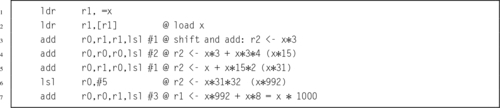

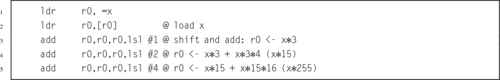

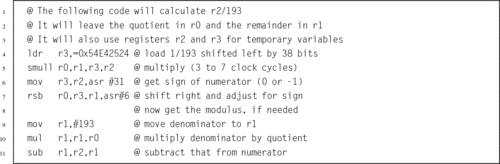

Listing 7.6 ARM assembly code for division of a variable by a constant without using a multiply instruction 193

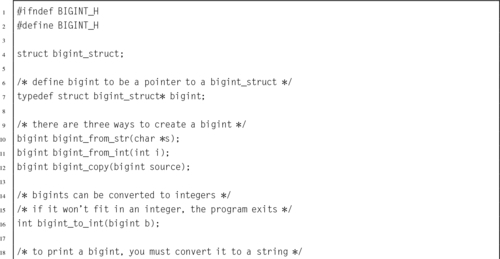

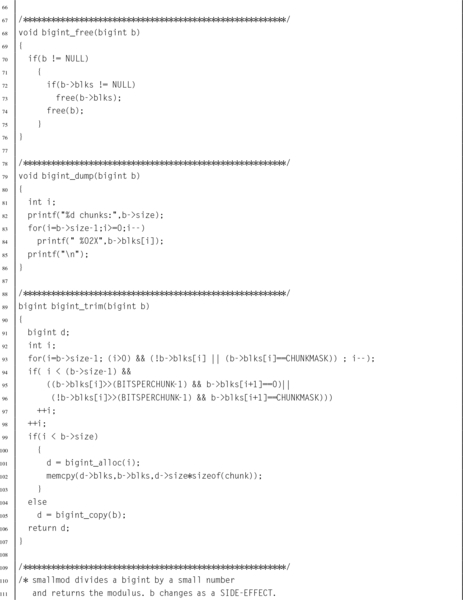

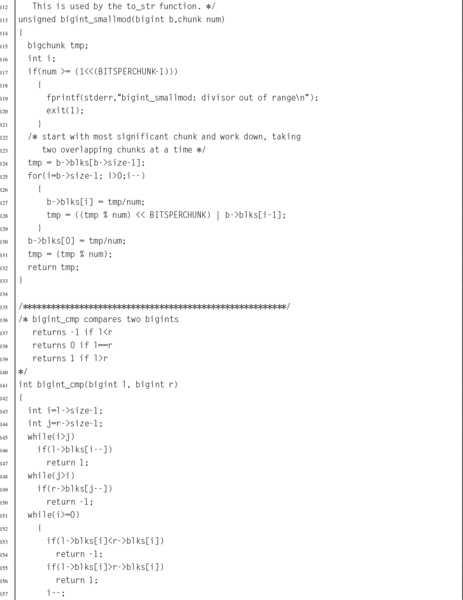

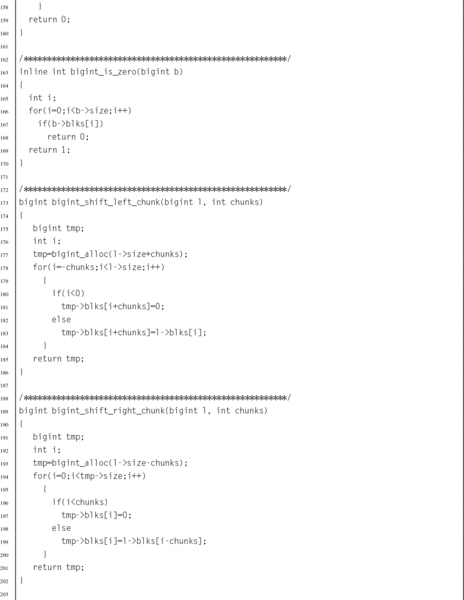

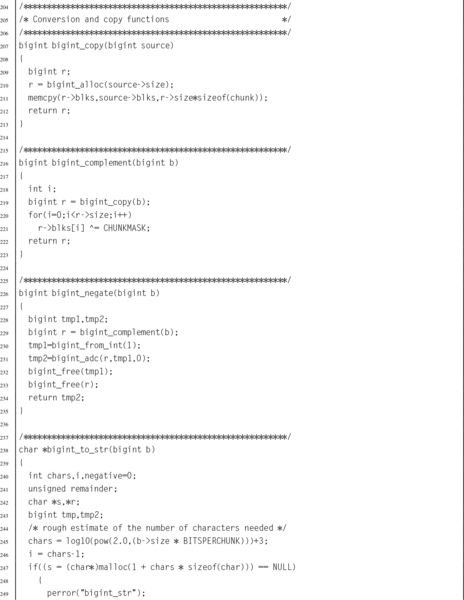

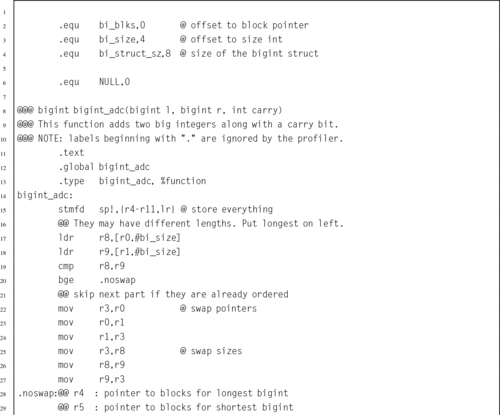

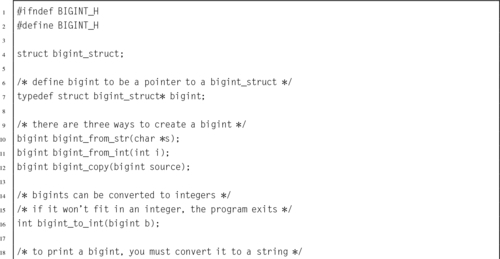

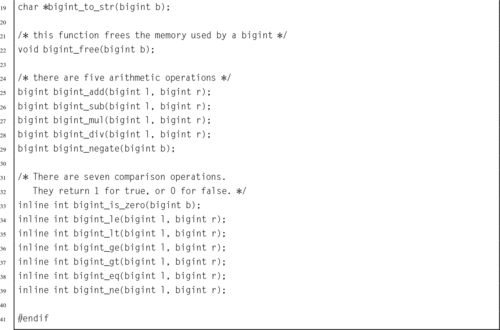

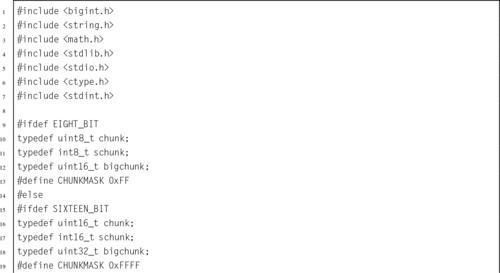

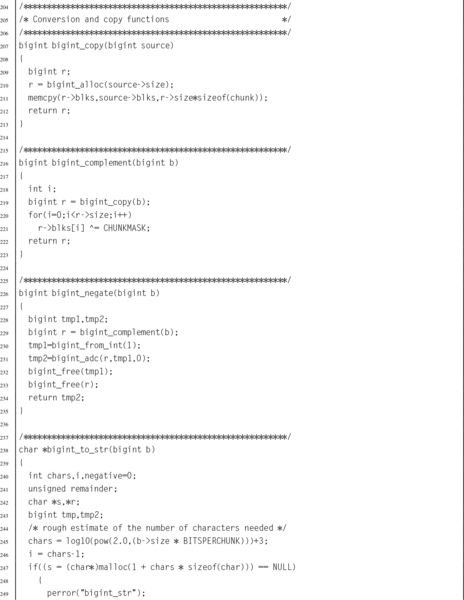

Listing 7.7 Header file for a big integer abstract data type 195

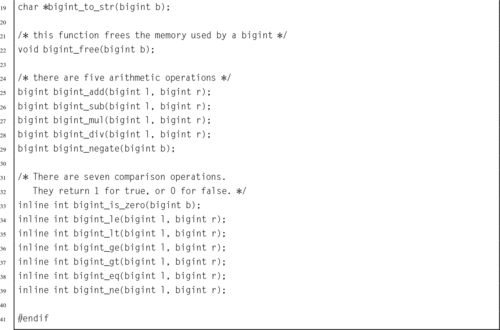

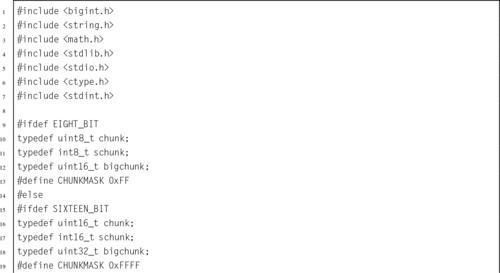

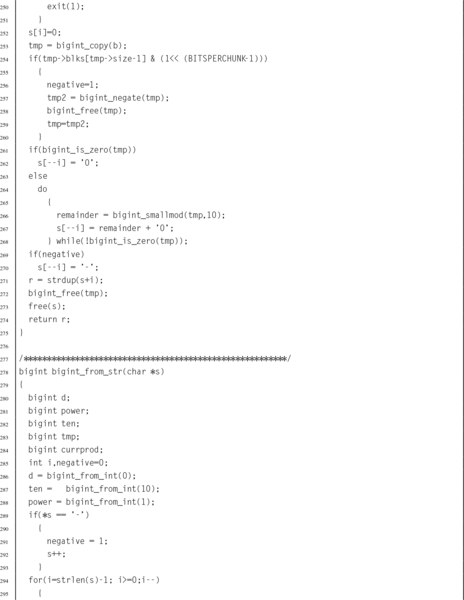

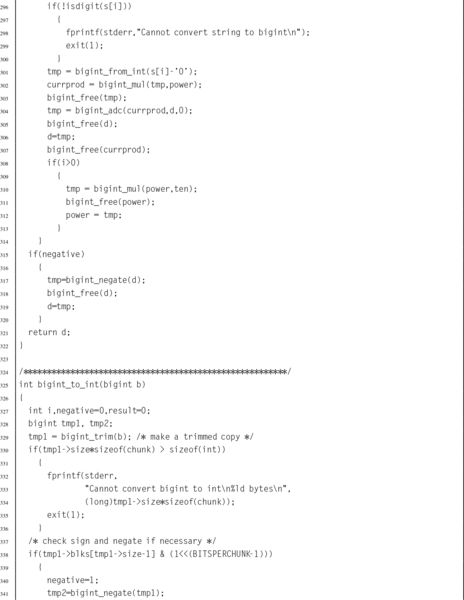

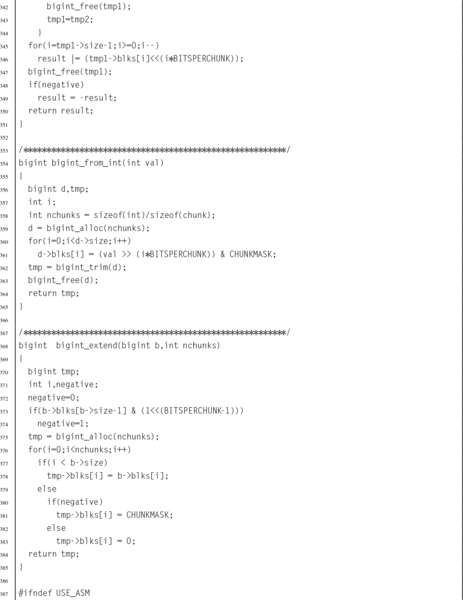

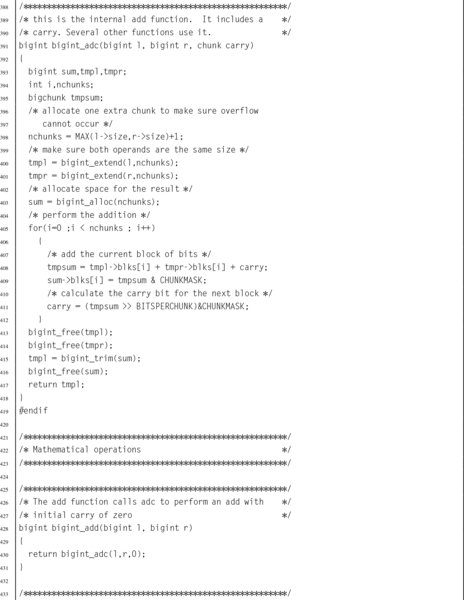

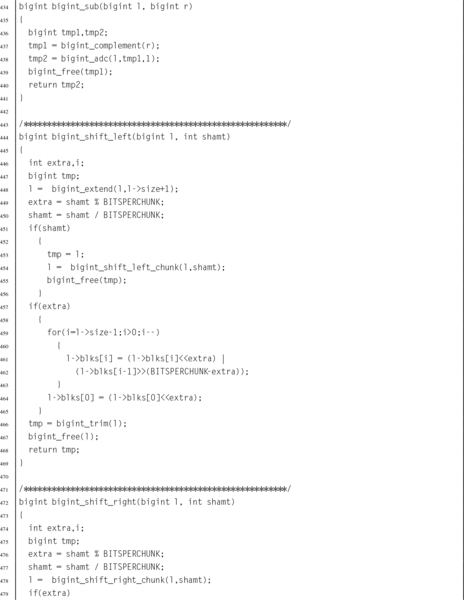

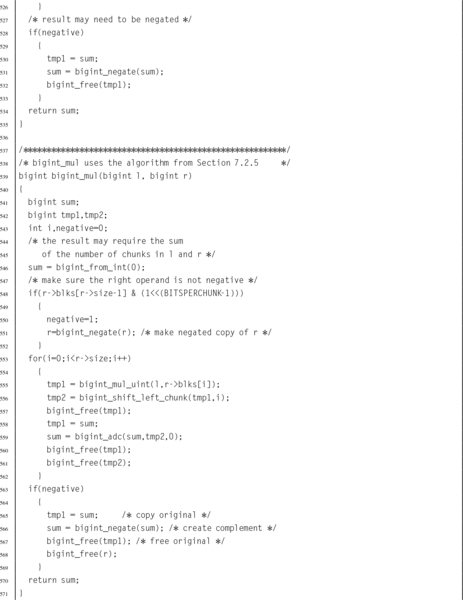

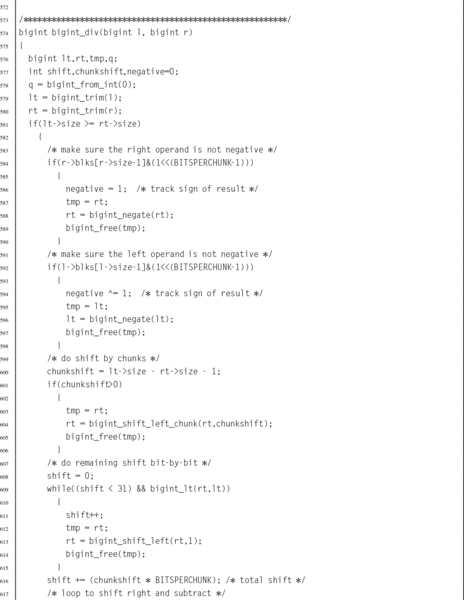

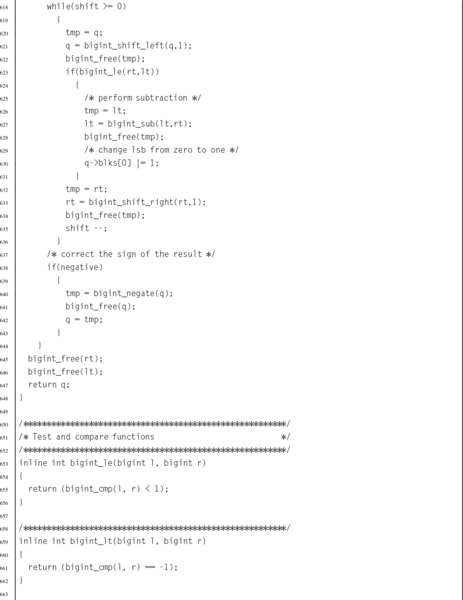

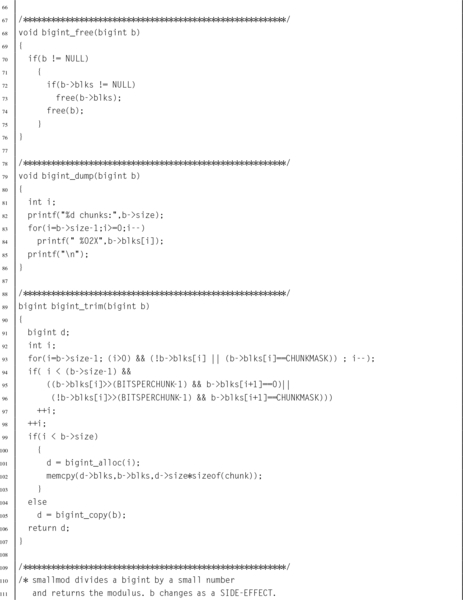

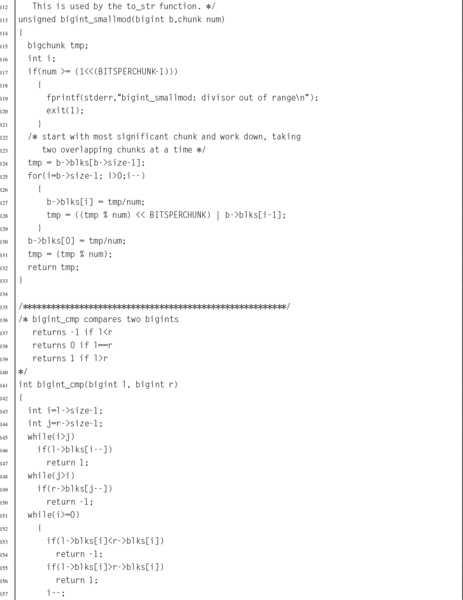

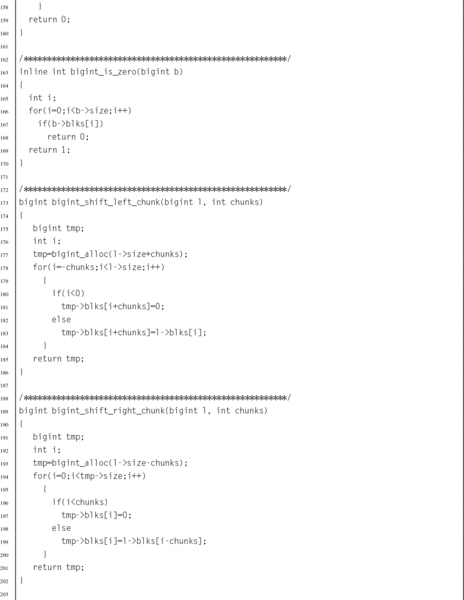

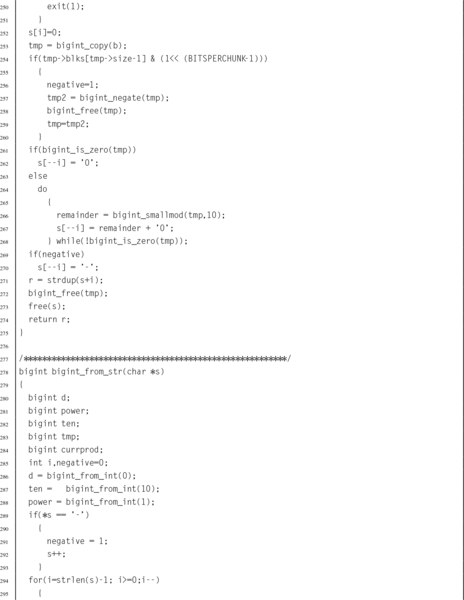

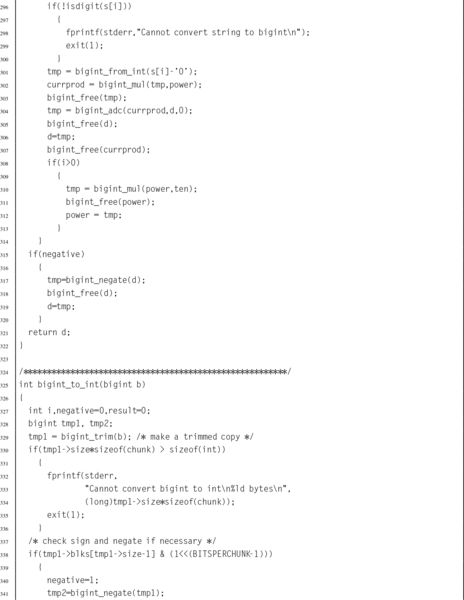

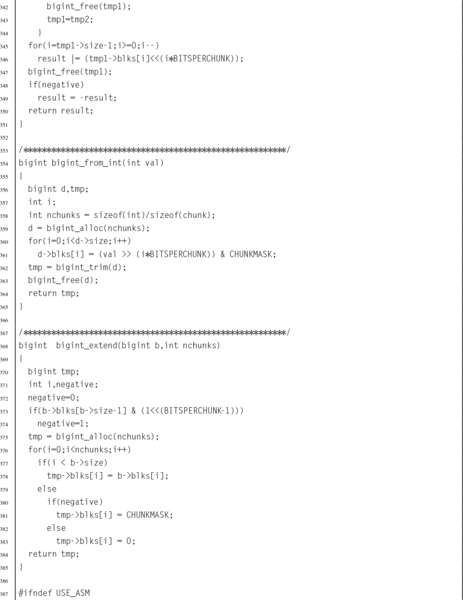

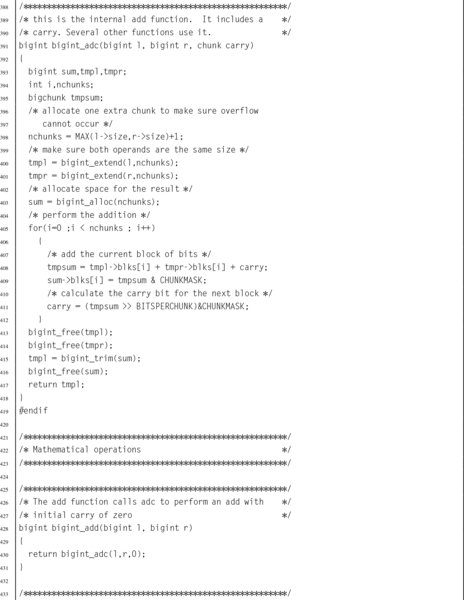

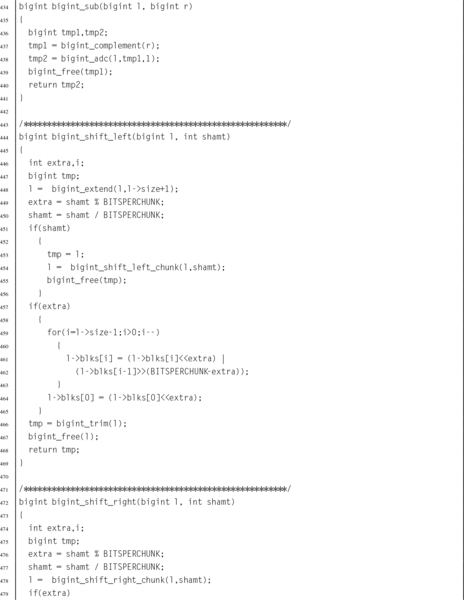

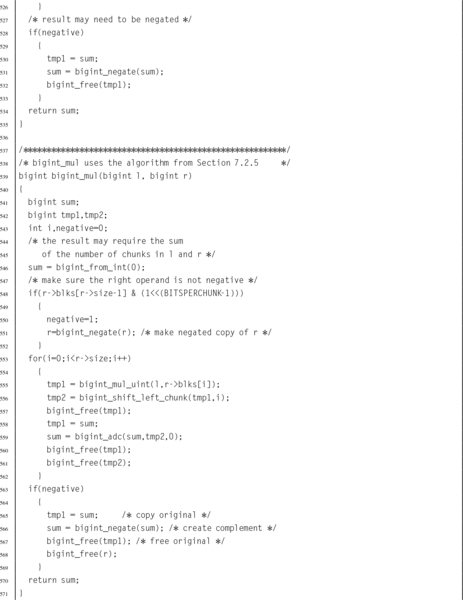

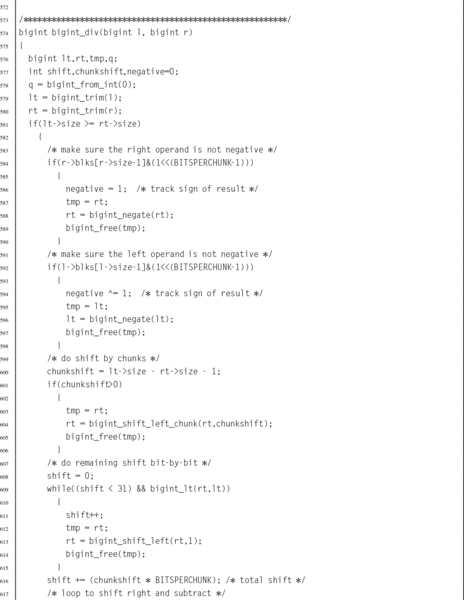

Listing 7.8 C source code file for a big integer abstract data type 196

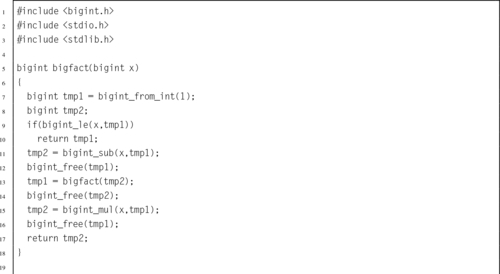

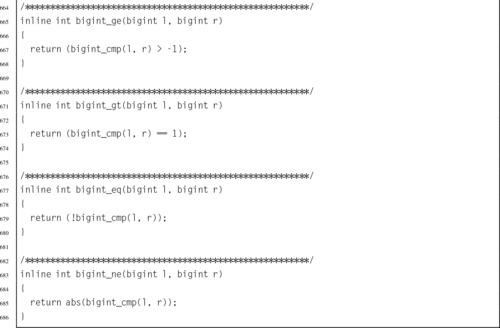

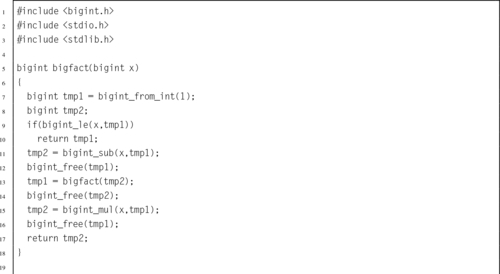

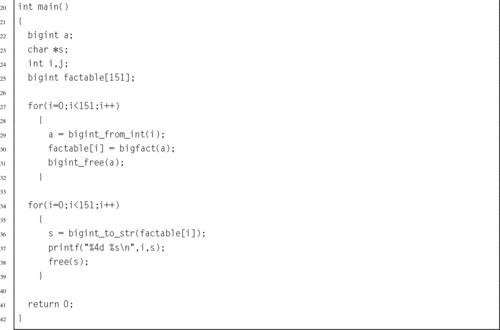

Listing 7.9 Program using the bigint ADT to calculate the factorial function 211

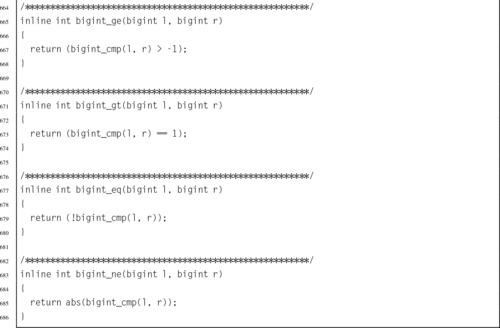

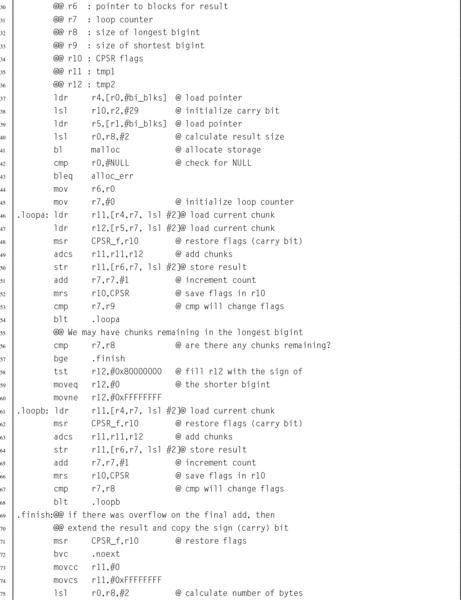

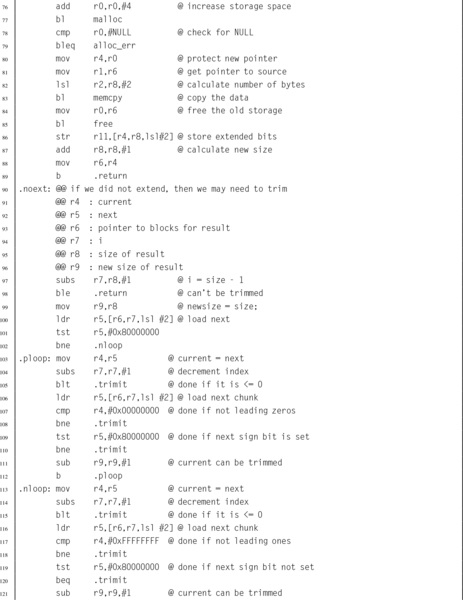

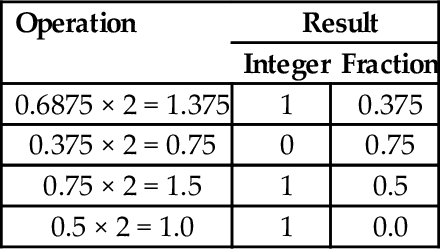

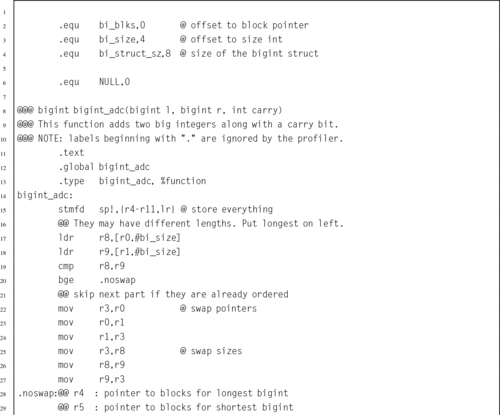

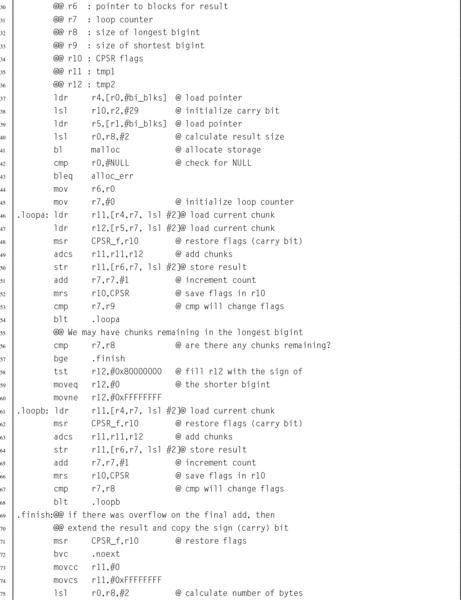

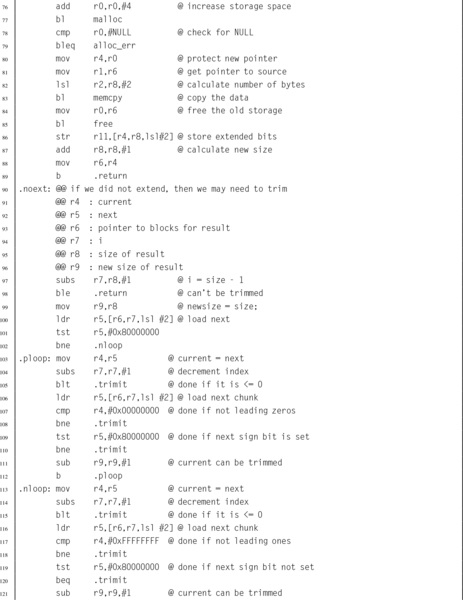

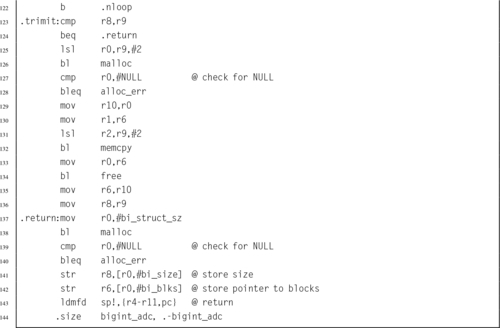

Listing 7.10 ARM assembly implementation if the bigint_adc function 213

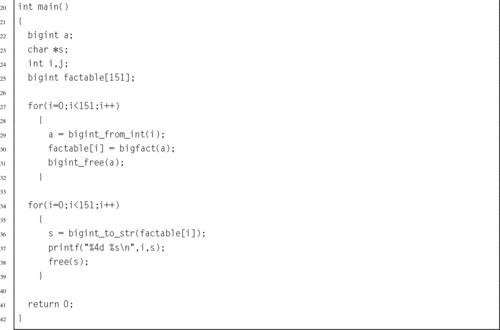

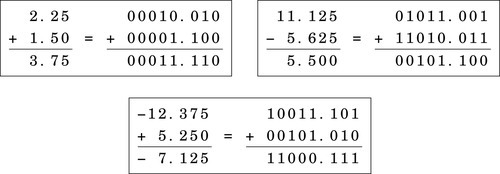

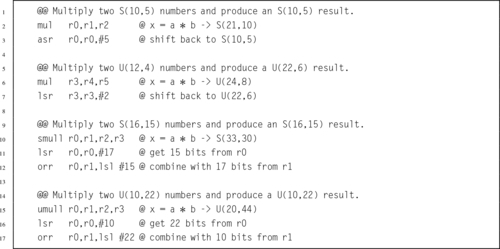

Listing 8.1 Examples of fixed-point multiplication in ARM assembly 233

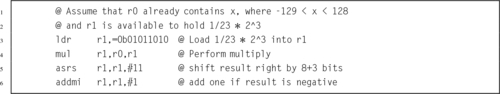

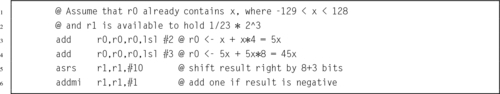

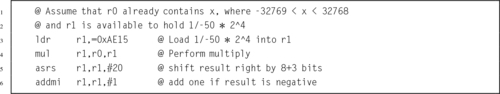

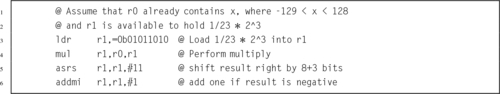

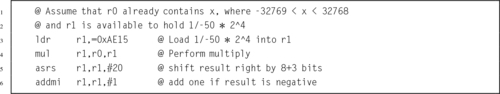

Listing 8.2 Dividing x by 23 239

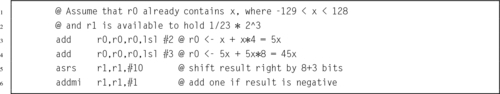

Listing 8.3 Dividing x by 23 Using Only Shift and Add 240

Listing 8.4 Dividing x by − 50 242

Listing 8.5 Inefficient representation of a binimal 242

Listing 8.6 Efficient representation of a binimal 243

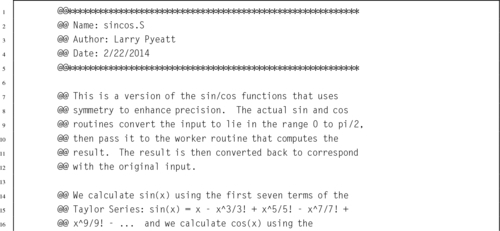

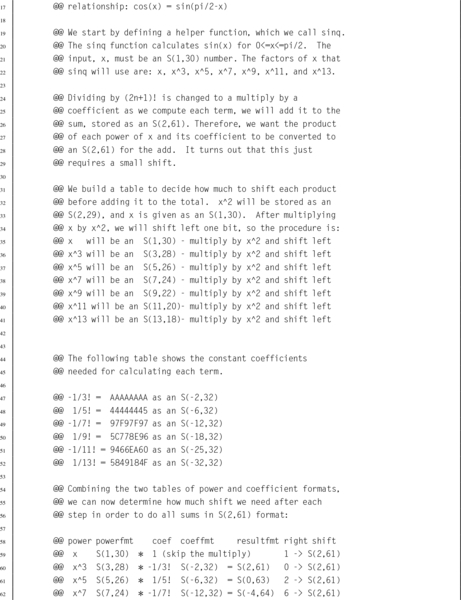

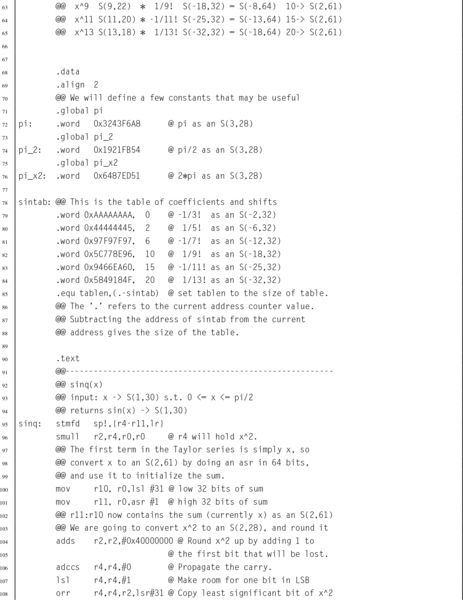

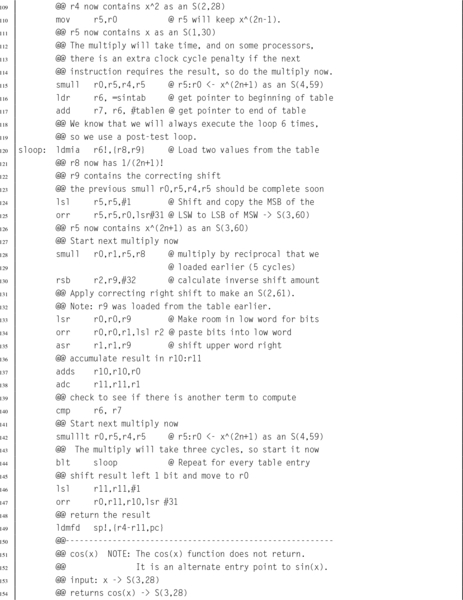

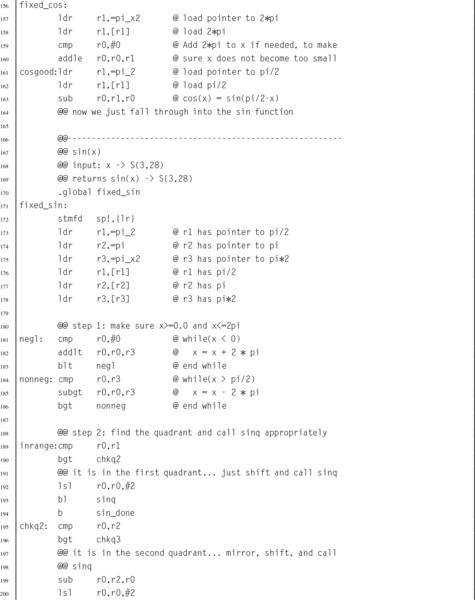

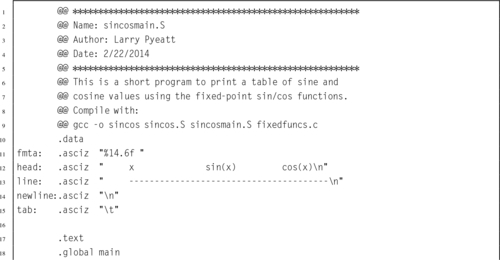

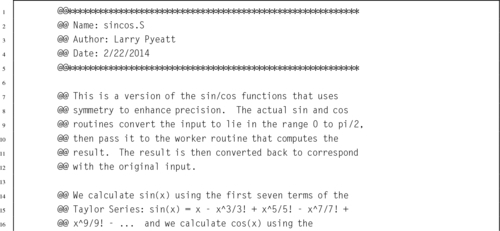

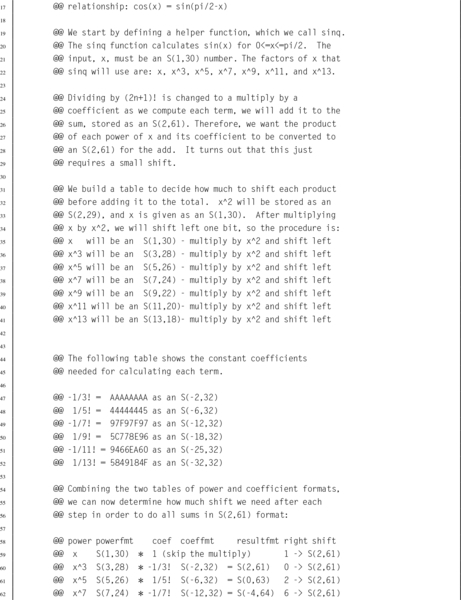

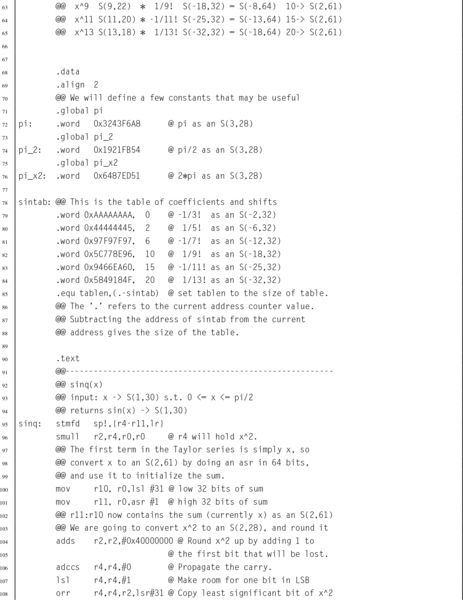

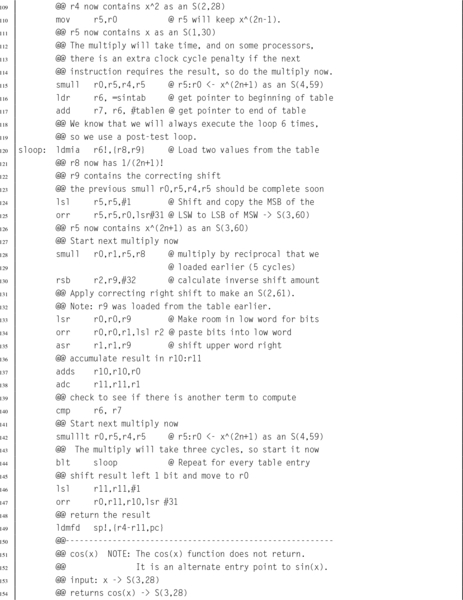

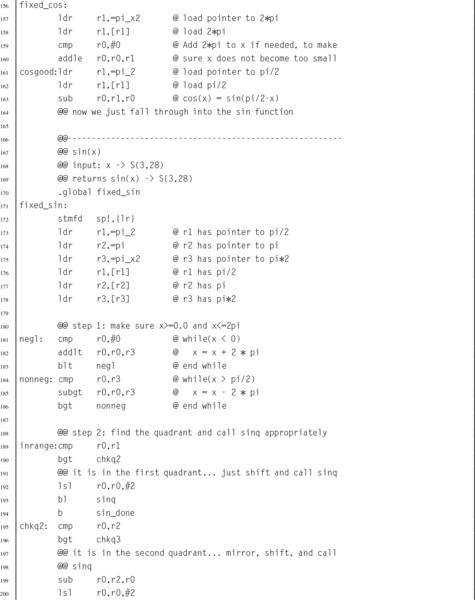

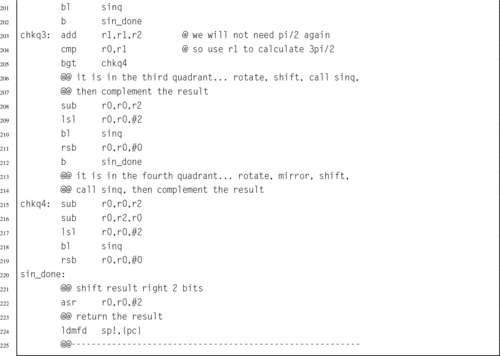

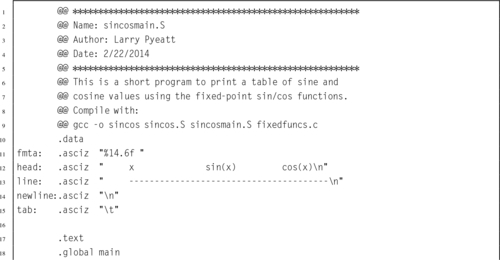

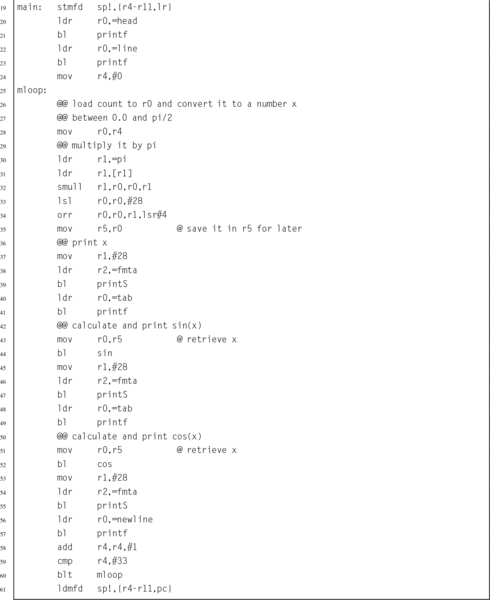

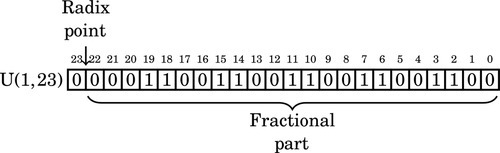

Listing 8.7 ARM assembly implementation of sin x and cos x using fixed-point calculations 252

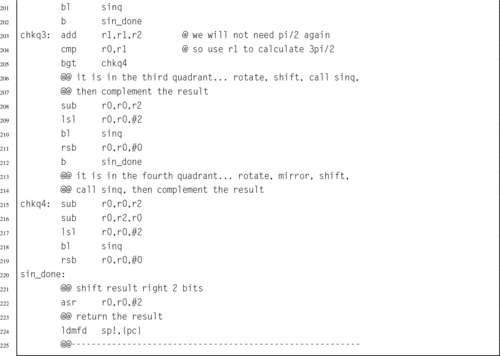

Listing 8.8 Example showing how the sin x and cos x functions can be used to print a table 257

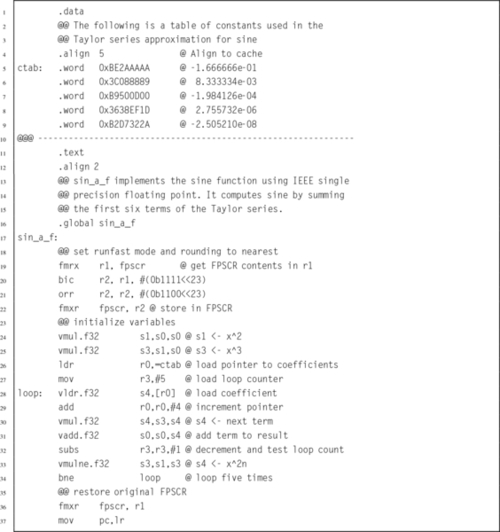

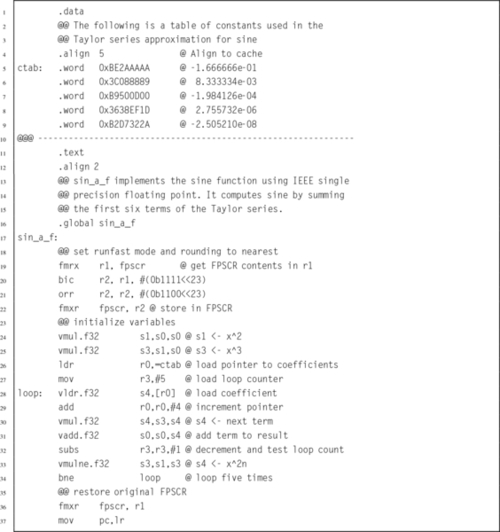

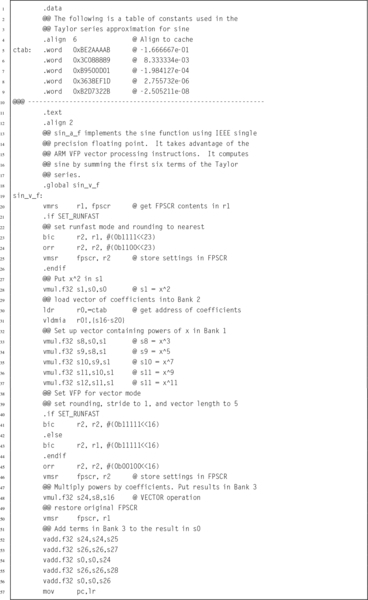

Listing 9.1 Simple scalar implementation of the sin x function using IEEE single precision 285

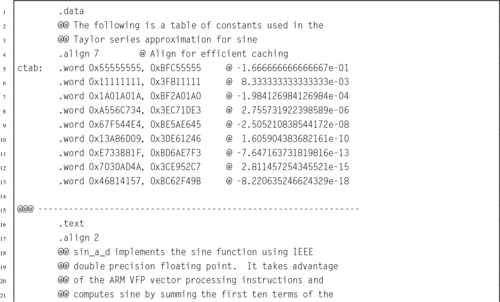

Listing 9.2 Simple scalar implementation of the sin x function using IEEE double precision 286

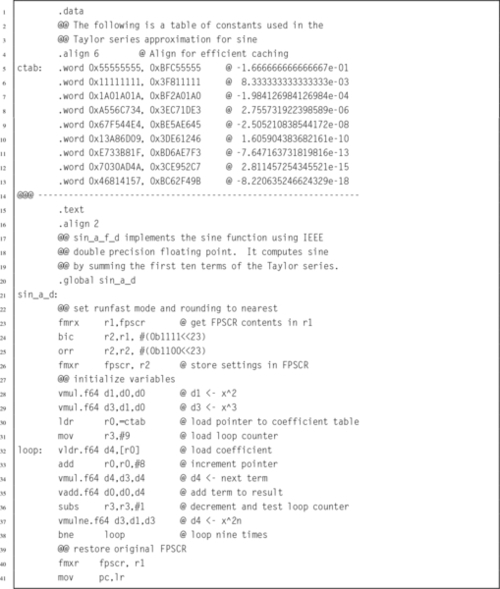

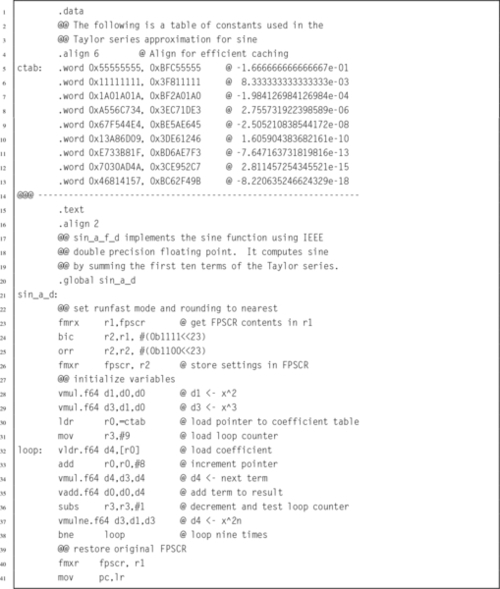

Listing 9.3 Vector implementation of the sin x function using IEEE single precision 288

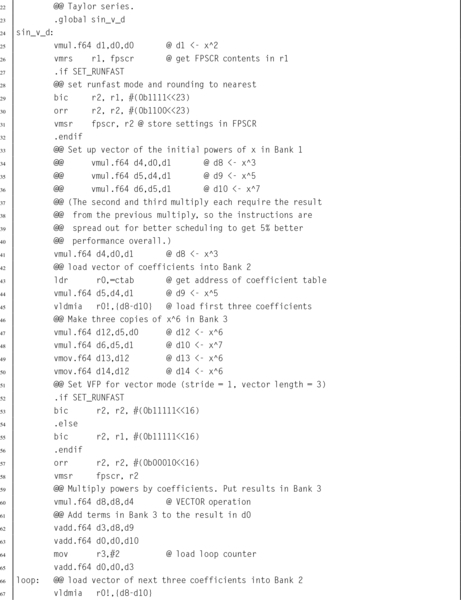

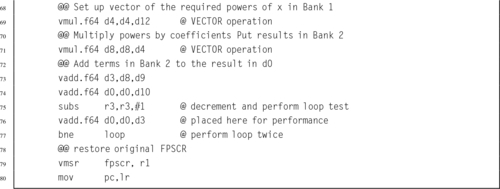

Listing 9.4 Vector implementation of the sin x function using IEEE double precision 289

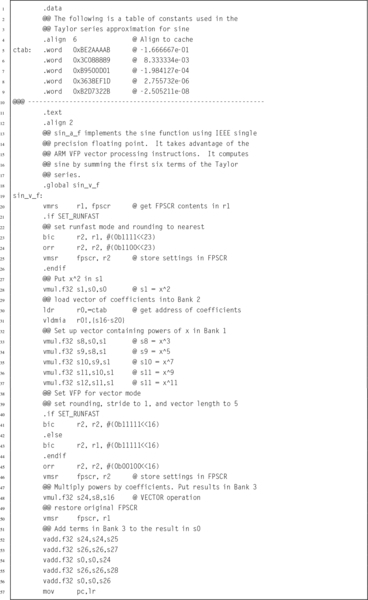

Listing 10.1 NEON implementation of the sin x function using single precision 354

Listing 10.2 NEON implementation of the sin x function using double precision 355

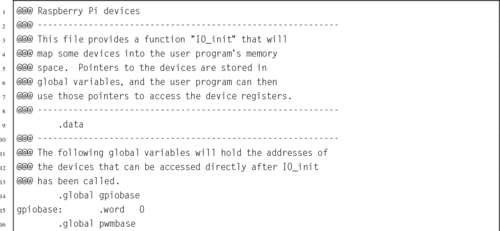

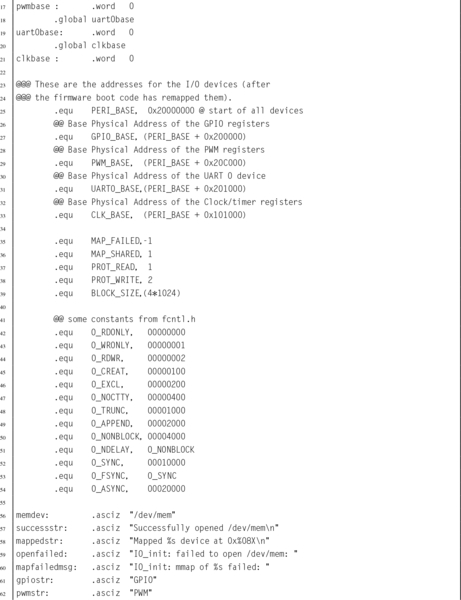

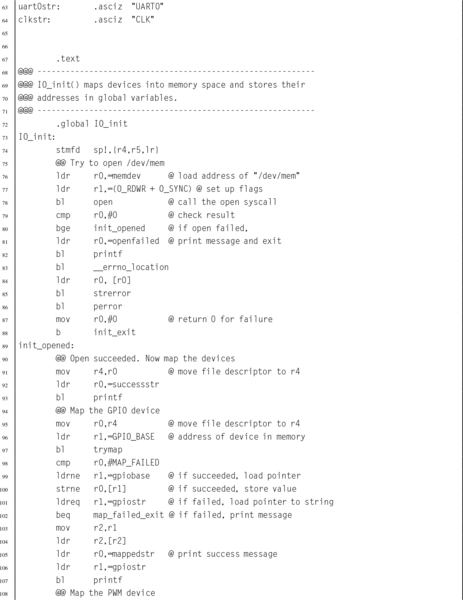

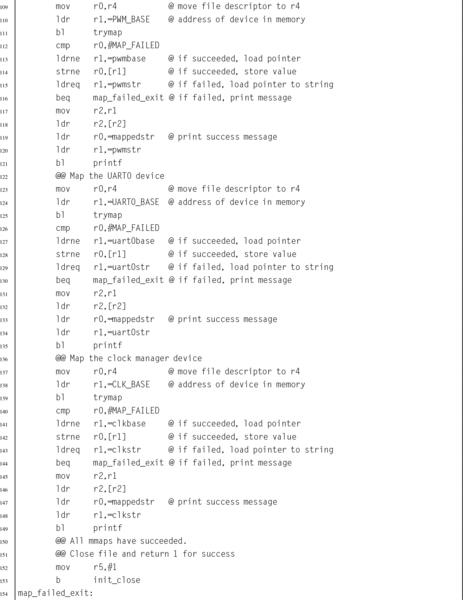

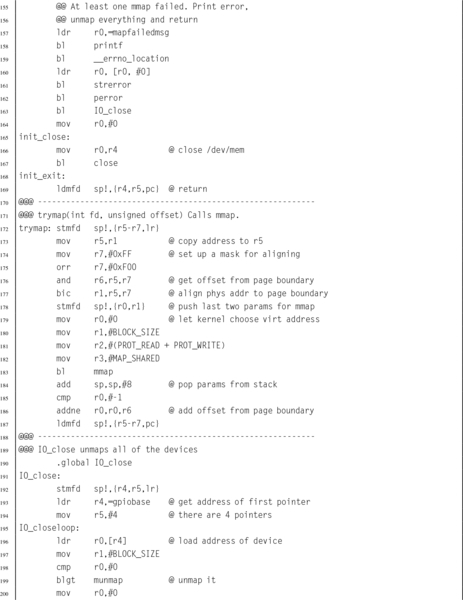

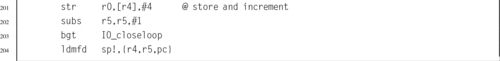

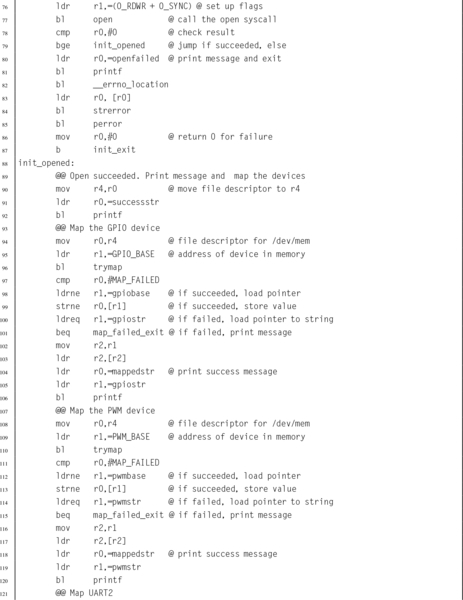

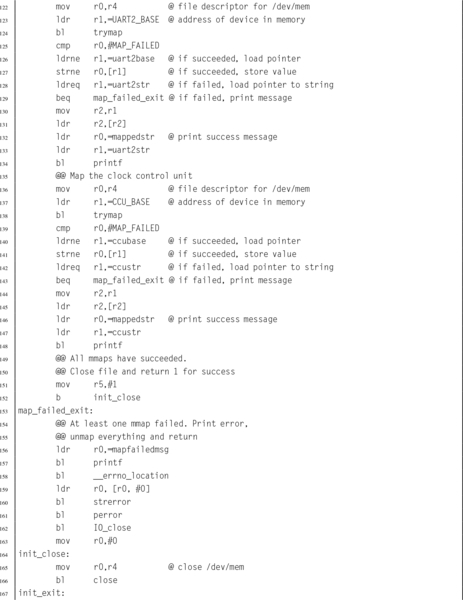

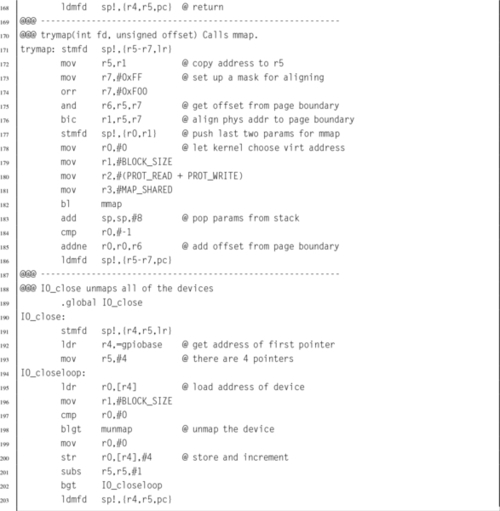

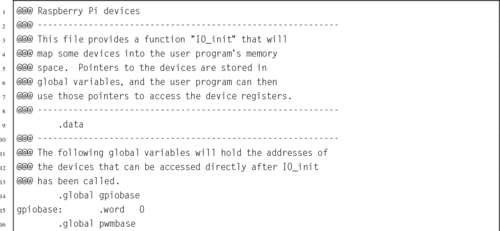

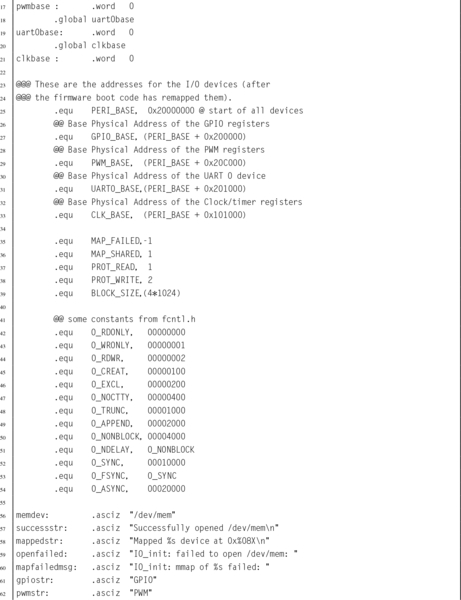

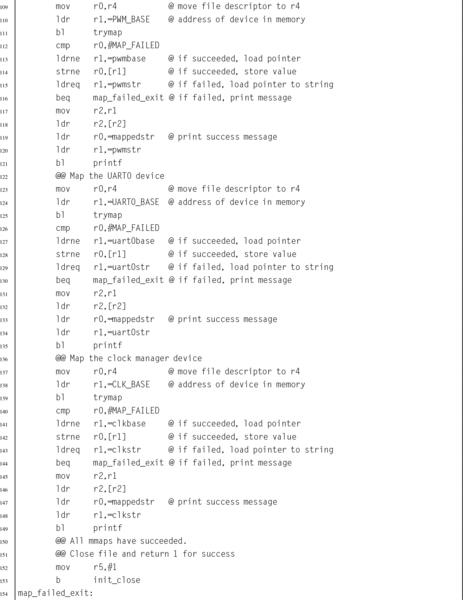

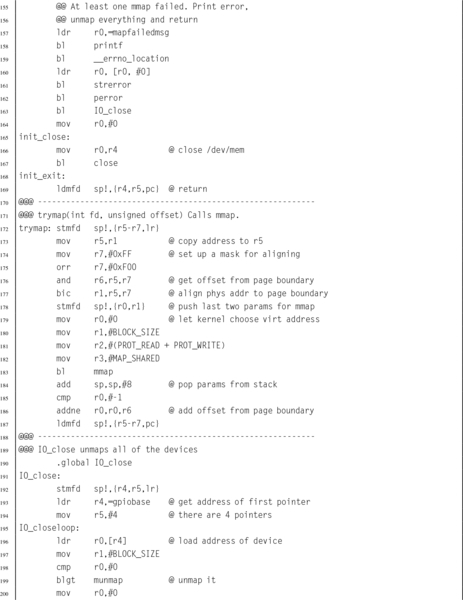

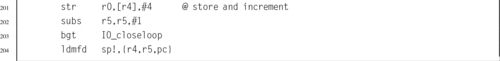

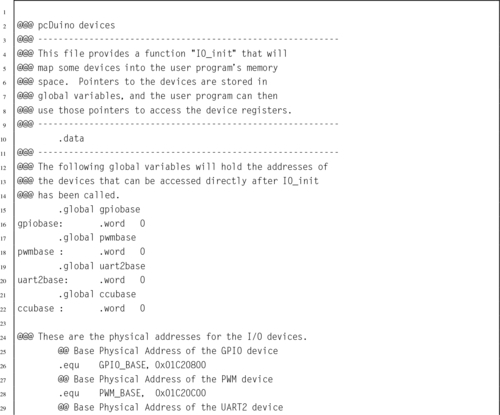

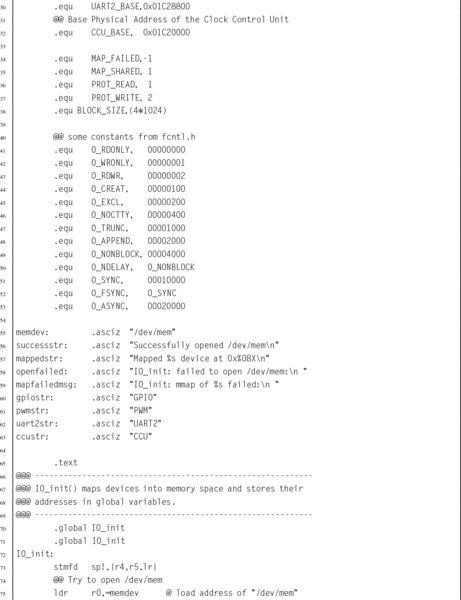

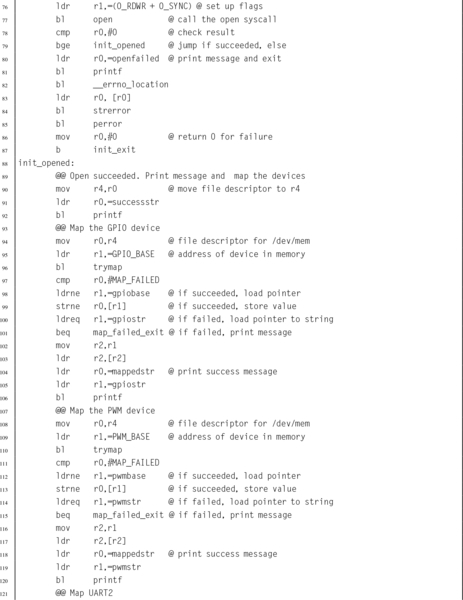

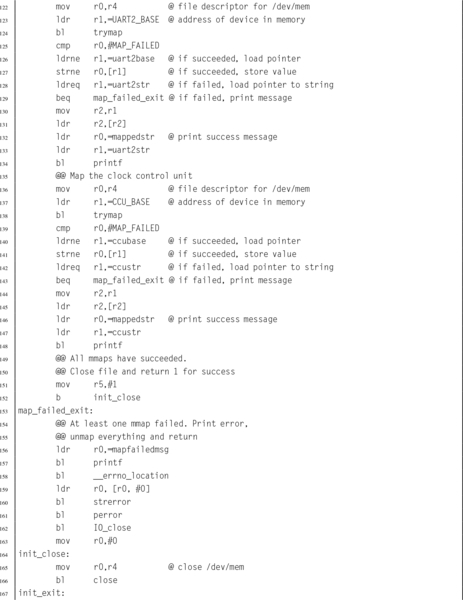

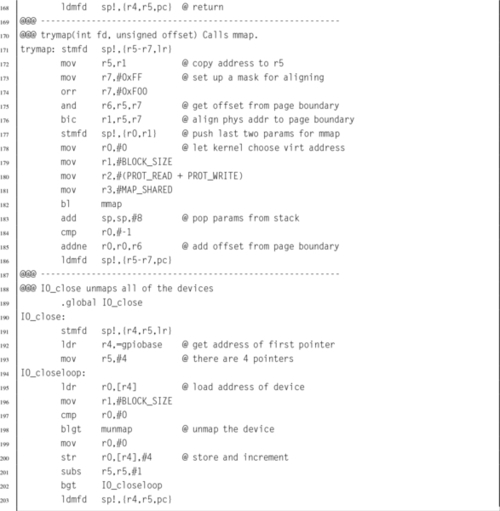

Listing 11.1 Function to map devices into the user program memory on a Raspberry Pi 367

Listing 11.2 Function to map devices into the user program memory space on a pcDuino 372

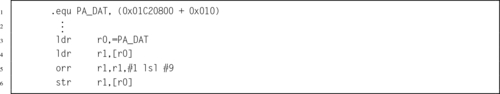

Listing 11.3 ARM assembly code to set GPIO pin 26 to alternate function 1 381

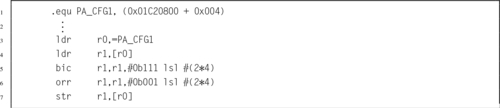

Listing 11.4 ARM assembly code to configure PA10 for output 388

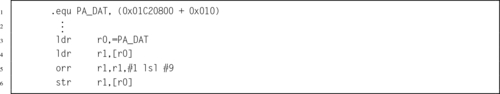

Listing 11.5 ARM assembly code to set PA10 to output a high state 389

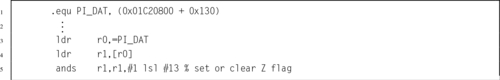

Listing 11.6 ARM assembly code to read the state of PI14 and set or clear the Z flag 389

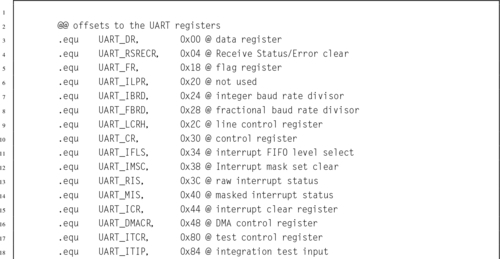

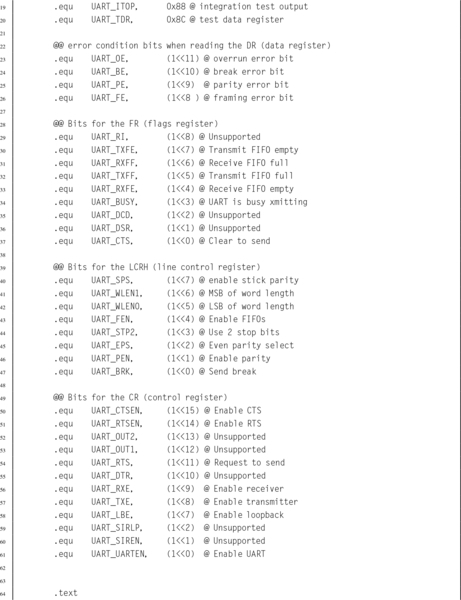

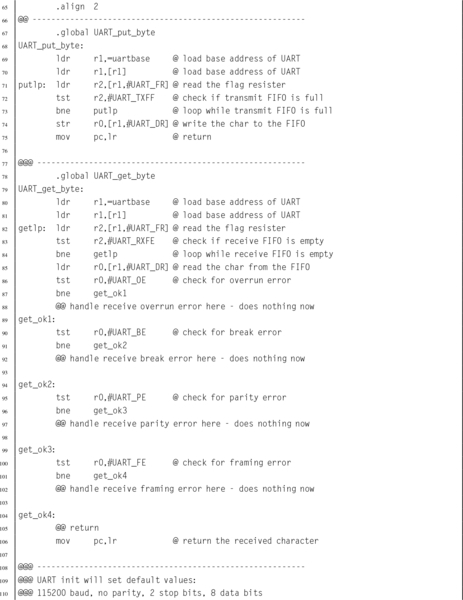

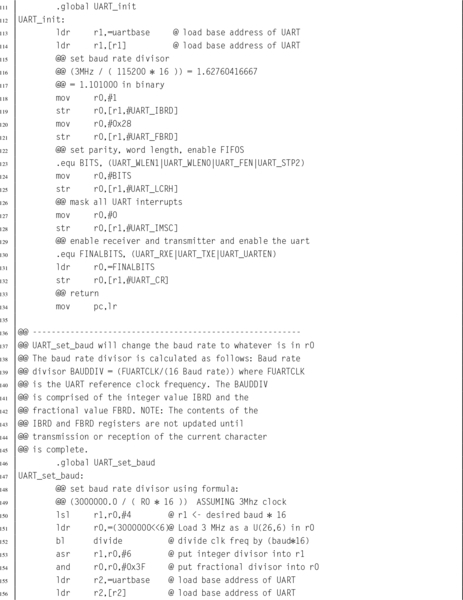

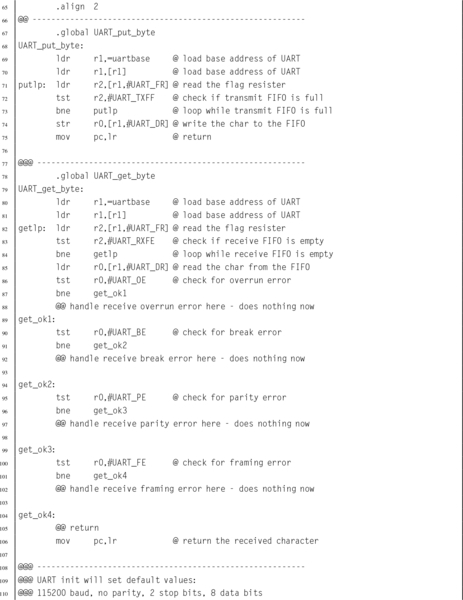

Listing 13.1 Assembly functions for using the Raspberry Pi UART 418

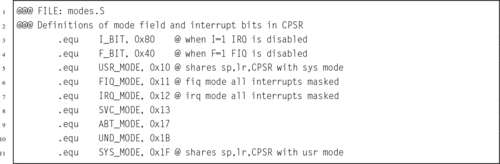

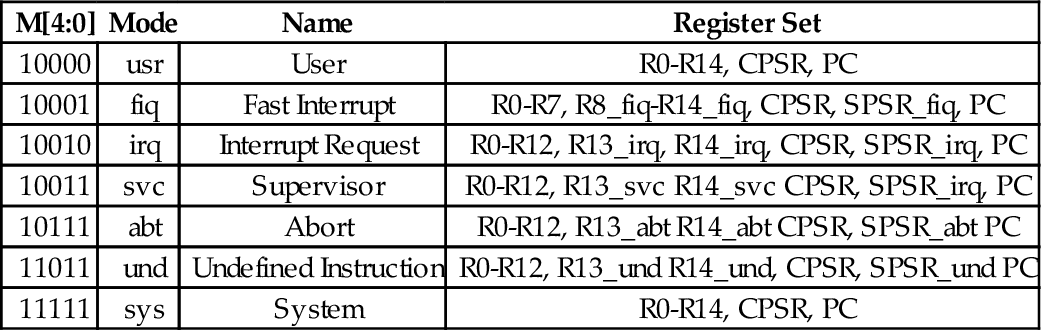

Listing 14.1 Definitions for ARM CPU modes 435

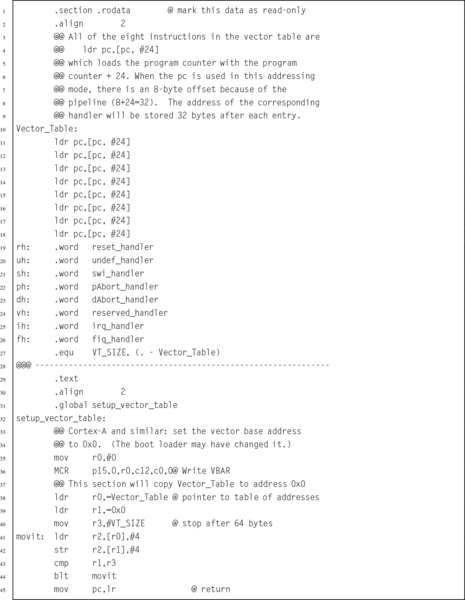

Listing 14.2 Function to set up the ARM exception table 439

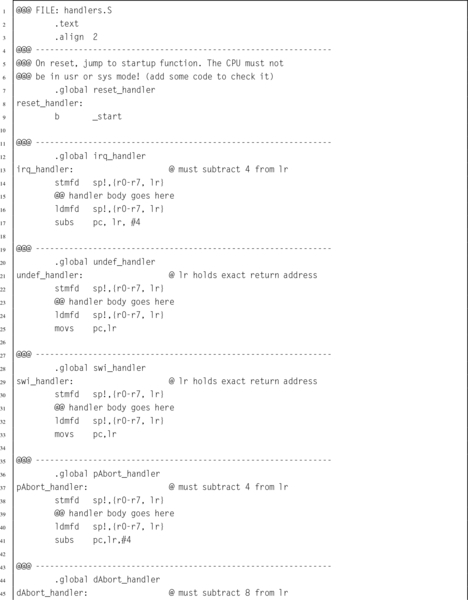

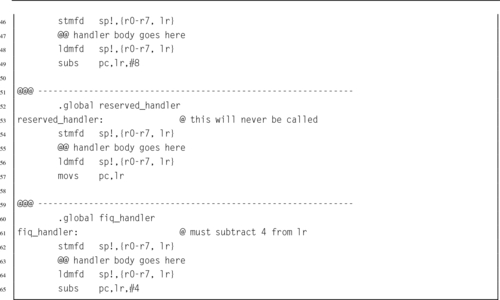

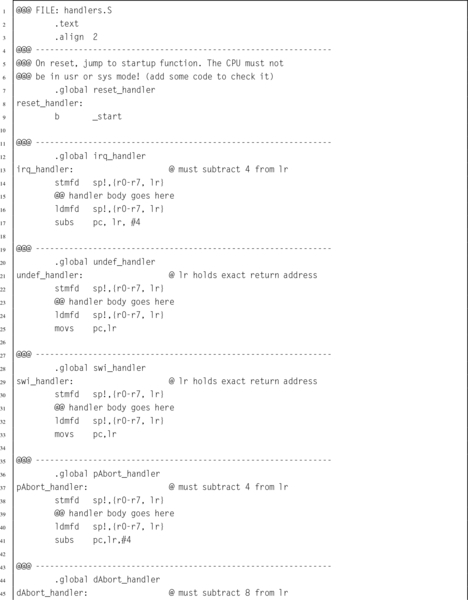

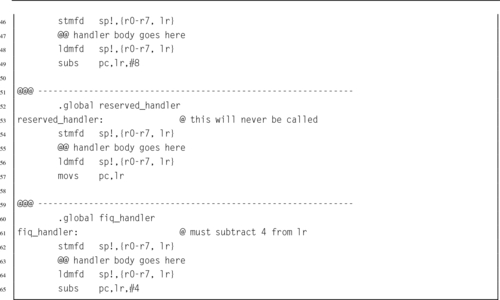

Listing 14.3 Stubs for the exception handlers 440

Listing 14.4 Skeleton for an exception handler 441

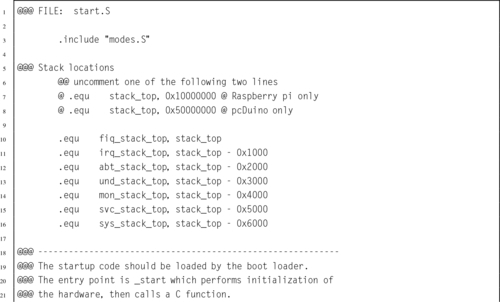

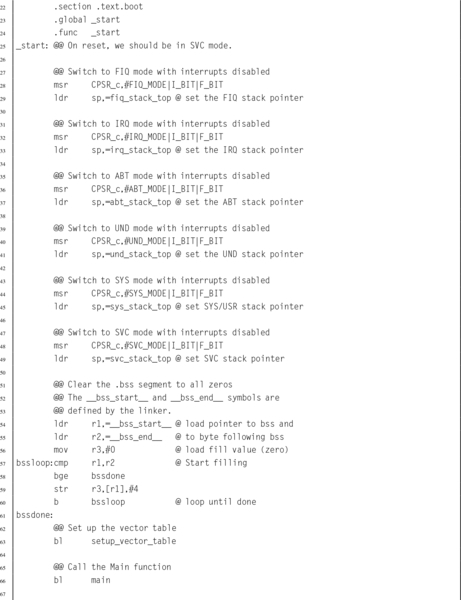

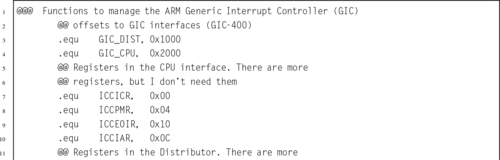

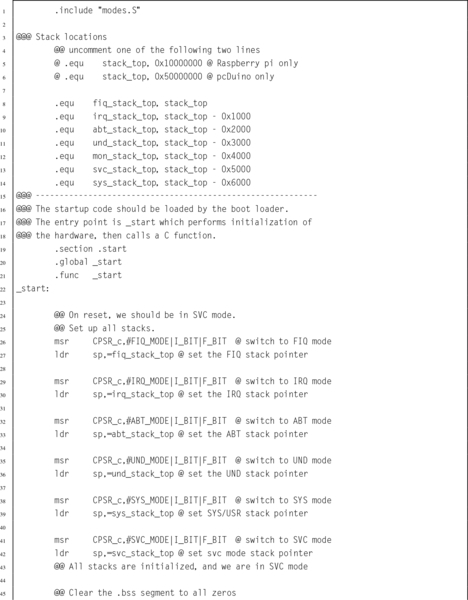

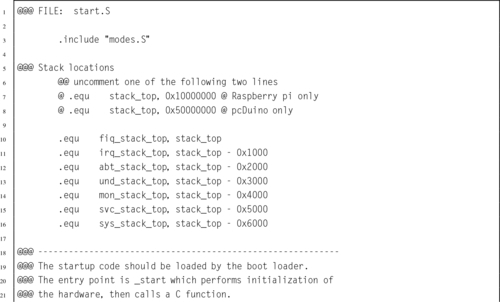

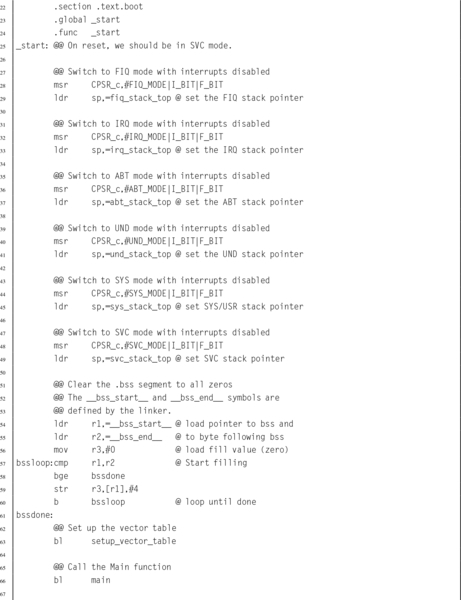

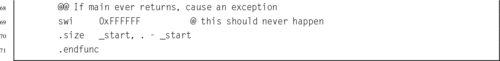

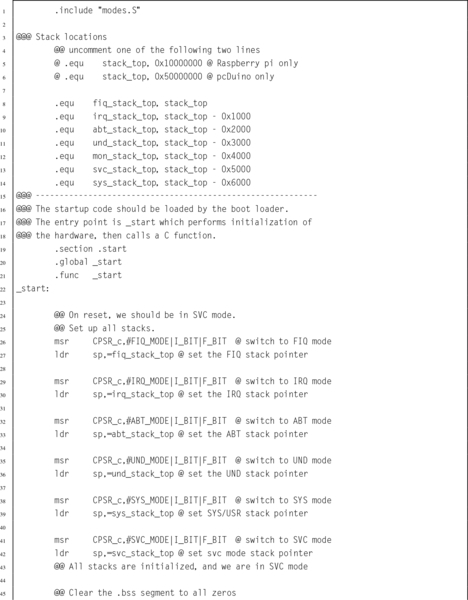

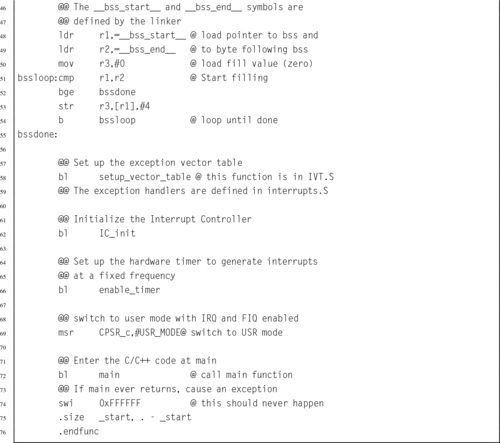

Listing 14.5 ARM startup code 443

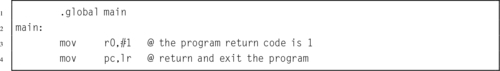

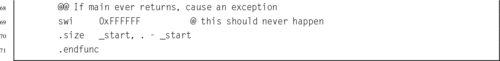

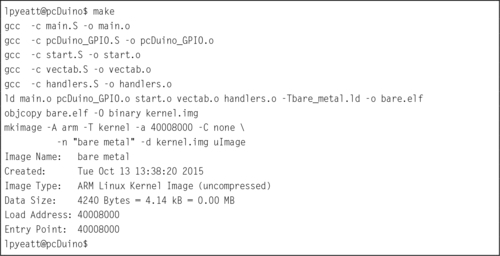

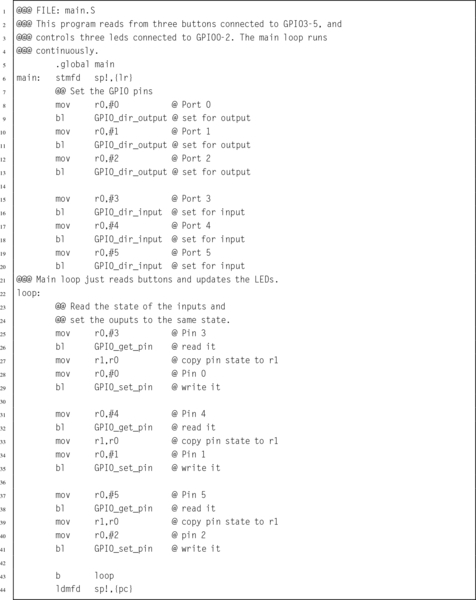

Listing 14.6 A simple main program 446

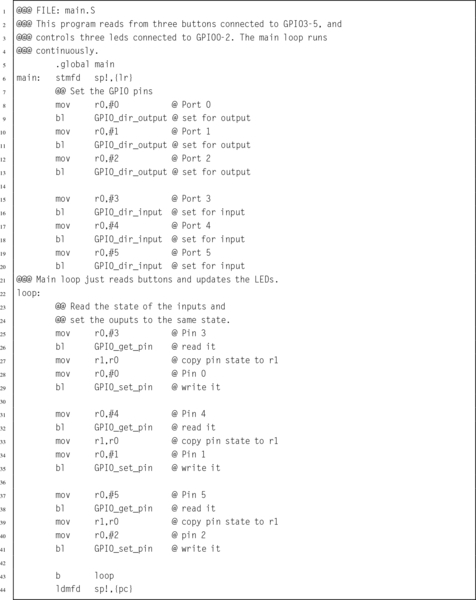

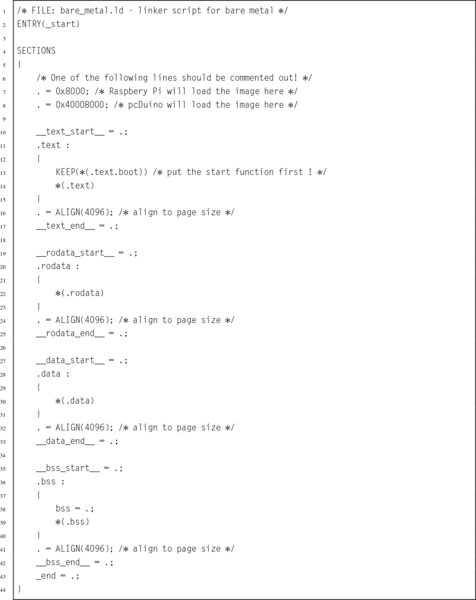

Listing 14.7 A sample Gnu linker script 448

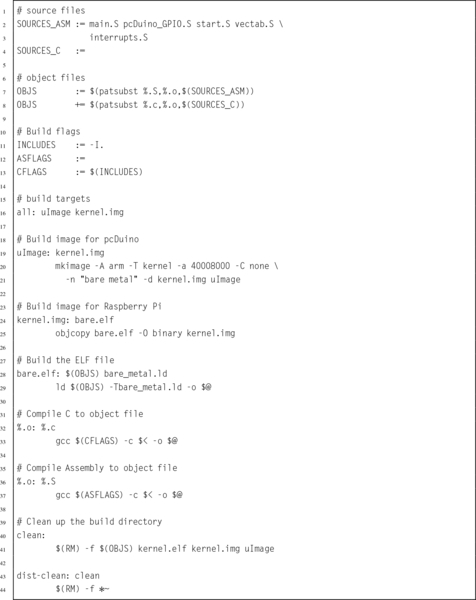

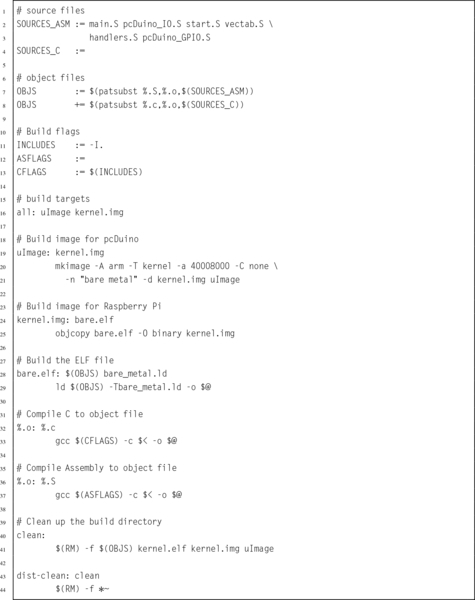

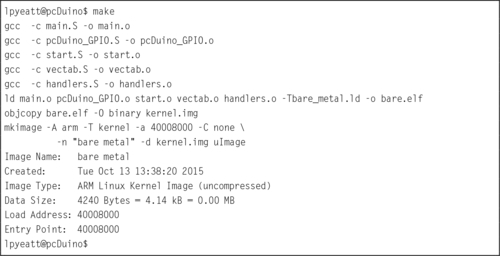

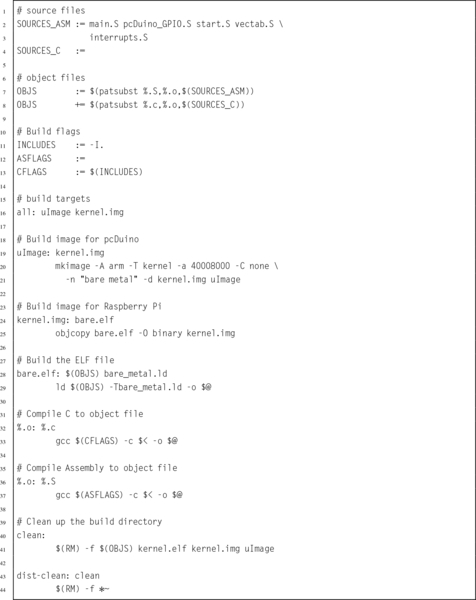

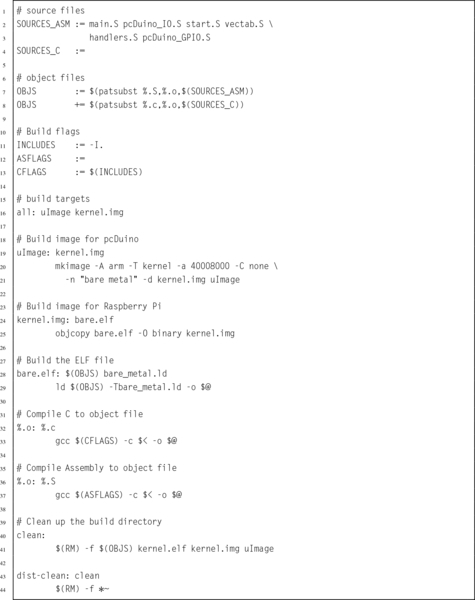

Listing 14.8 A sample make file 450

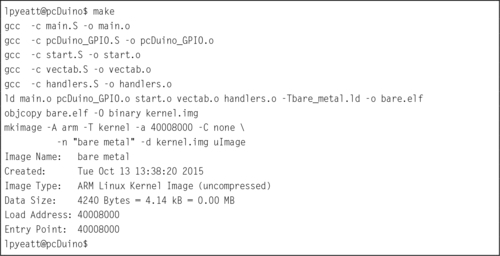

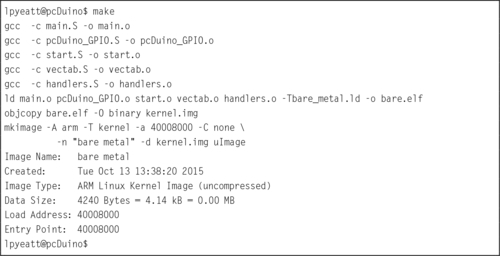

Listing 14.9 Running make to build the image 451

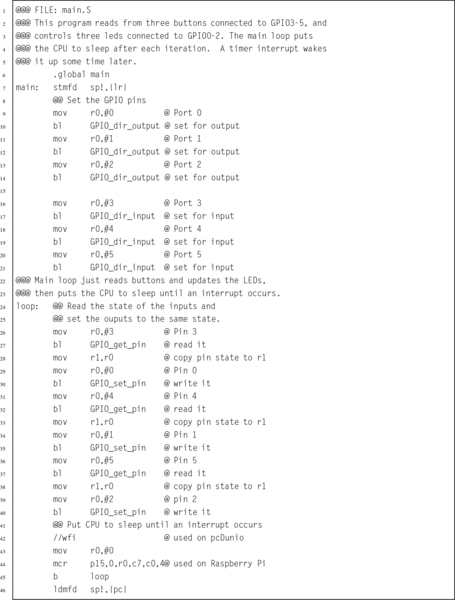

Listing 14.10 An improved main program 452

Listing 14.11 ARM startup code with timer interrupt 453

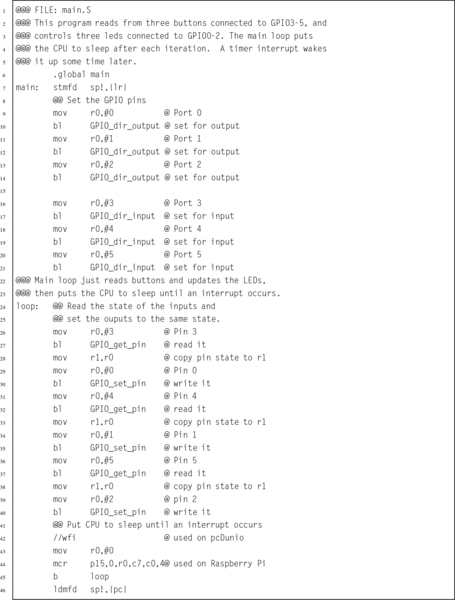

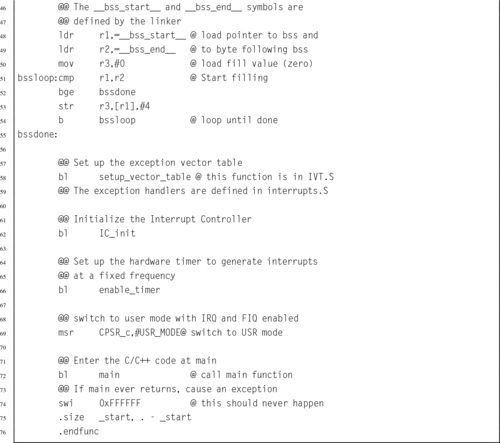

Listing 14.12 Functions to manage the pdDuino interrupt controller 454

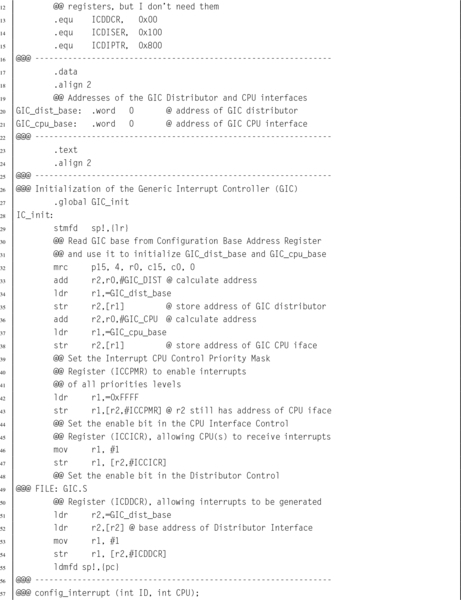

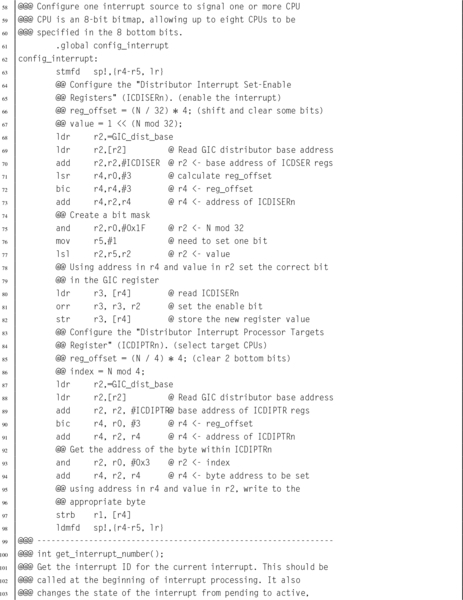

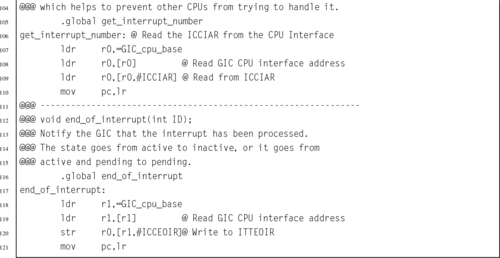

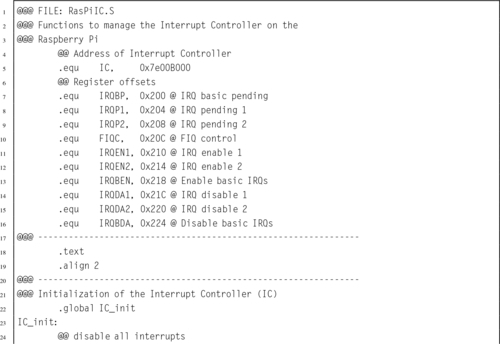

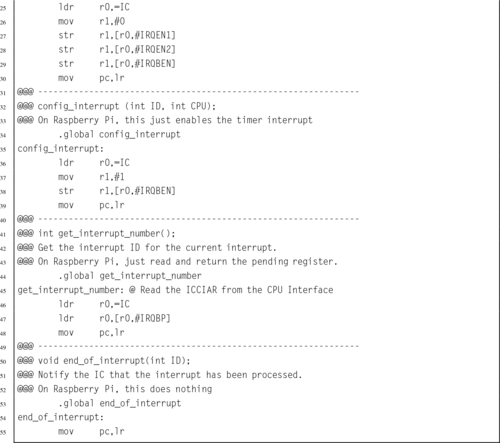

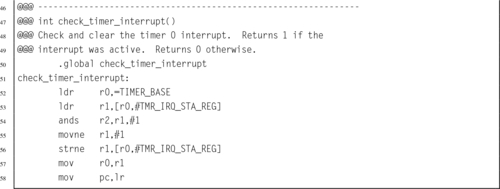

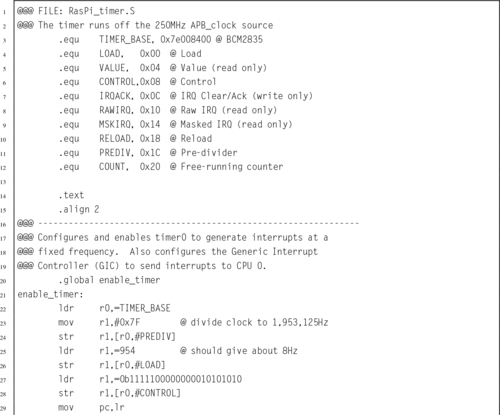

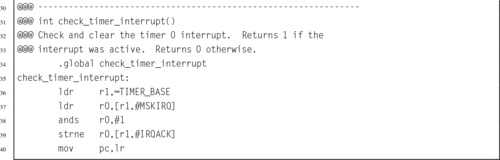

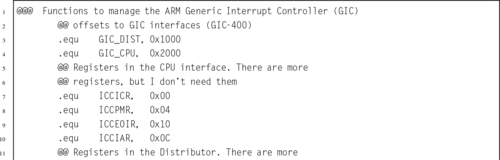

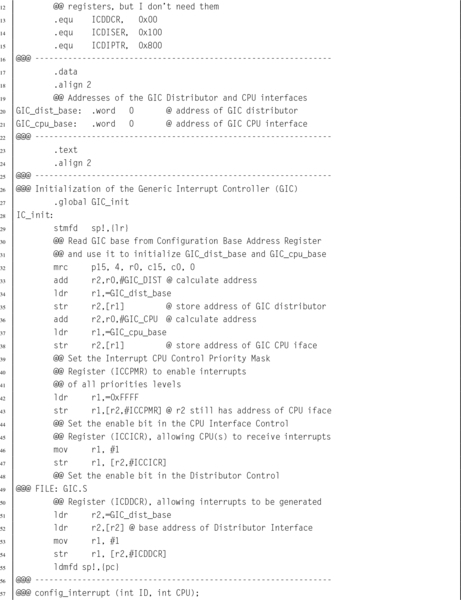

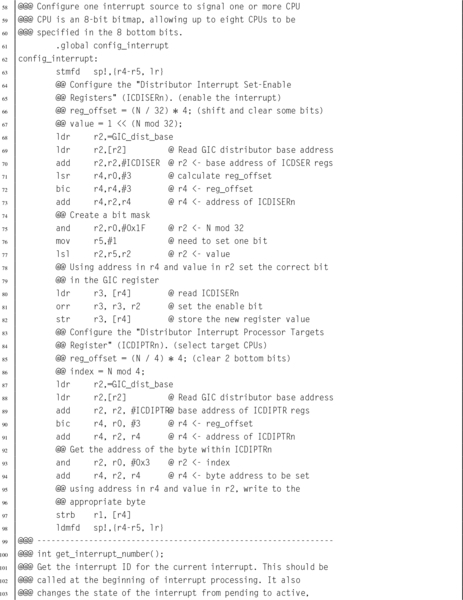

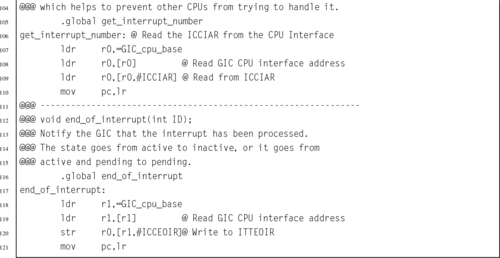

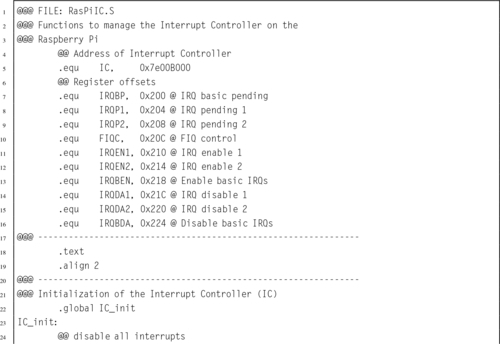

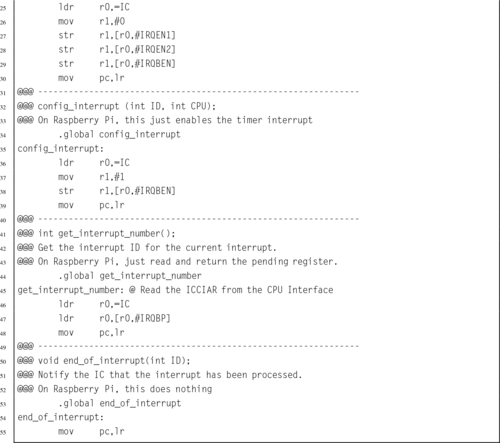

Listing 14.13 Functions to manage the Raspberry Pi interrupt controller 457

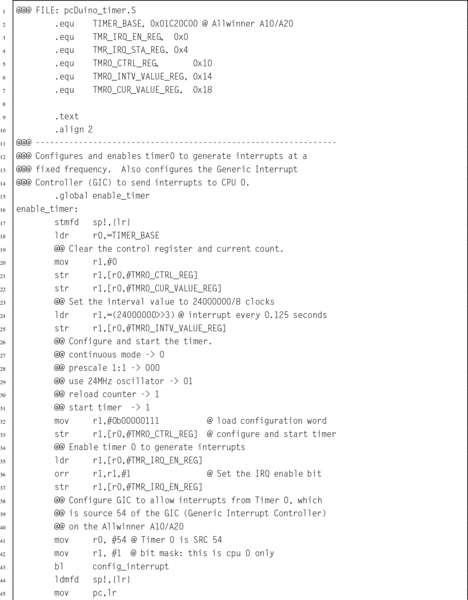

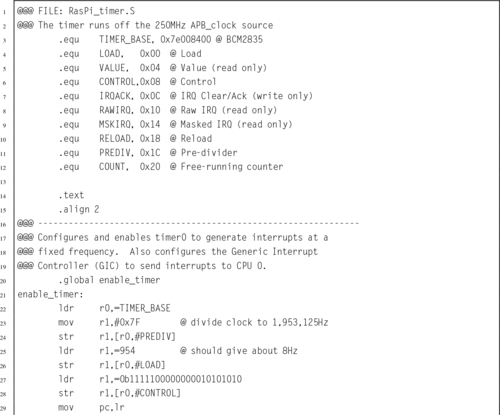

Listing 14.14 Functions to manage the pdDuino timer0 device 459

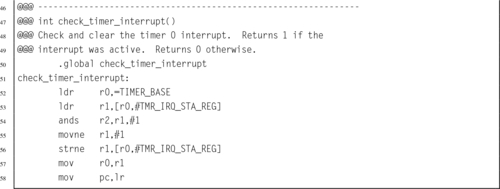

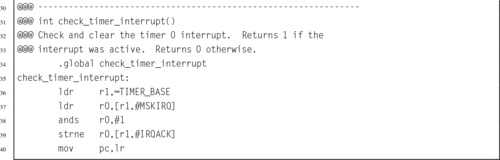

Listing 14.15 Functions to manage the Raspberry Pi timer0 device 460

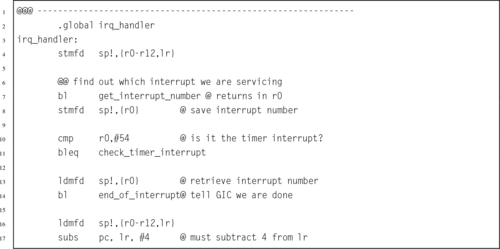

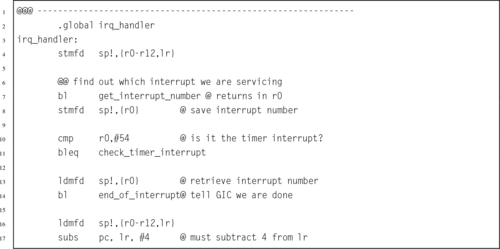

Listing 14.16 IRQ handler to clear the timer interrupt 462

Listing 14.17 A sample make file 463

Listing 14.18 Running make to build the image 464

This book is intended to be used in a first course in assembly language programming for Computer Science (CS) and Computer Engineering (CE) students. It is assumed that students using this book have already taken courses in programming and data structures, and are competent programmers in at least one high-level language. Many of the code examples in the book are written in C, with an assembly implementation following. The assembly examples can stand on their own, but students who are familiar with C, C++, or Java should find the C examples helpful.

Computer Science and Computer Engineering are very large fields. It is impossible to cover everything that a student may eventually need to know. There are a limited number of course hours available, so educators must strive to deliver degree programs that make a compromise between the number of concepts and skills that the students learn and the depth at which they learn those concepts and skills. Obviously, with these competing goals it is difficult to reach consensus on exactly what courses should be included in a CS or CE curriculum.

Traditionally, assembly language courses have consisted of a mechanistic learning of a set of instructions, registers, and syntax. Partially because of this approach, over the years, assembly language courses have been marginalized in, or removed altogether from, many CS and CE curricula. The author feels that this is unfortunate, because a solid understanding of assembly language leads to better understanding of higher-level languages, compilers, interpreters, architecture, operating systems, and other important CS an CE concepts.

One of the goals of this book is to make a course in assembly language more valuable by introducing methods (and a bit of theory) that are not covered in any other CS or CE courses, while using assembly language to implement the methods. In this way, the course in assembly language goes far beyond the traditional assembly language course, and can once again play an important role in the overall CS and CE curricula.

Because of their ubiquity, x86 based systems have been the platforms of choice for most assembly language courses over the last two decades. The author believes that this is unfortunate, because in every respect other than ubiquity, the x86 architecture is the worst possible choice for learning and teaching assembly language. The newer chips in the family have hundreds of instructions, and irregular rules govern how those instructions can be used. In an attempt to make it possible for students to succeed, typical courses use antiquated assemblers and interface with the antiquated IBM PC BIOS, using only a small subset of the modern x86 instruction set. The programming environment has little or no relevance to modern computing.

Partially because of this tendency to use x86 platforms, and the resulting unnecessary burden placed on students and instructors, as well as the reliance on antiquated and irrelevant development environments, assembly language is often viewed by students as very difficult and lacking in value. The author hopes that this textbook helps students to realize the value of knowing assembly language. The relatively simple ARM processor family was chosen in hopes that the students also learn that although assembly language programming may be more difficult than high-level languages, it can be mastered.

The recent development of very low-cost ARM based Linux computers has caused a surge of interest in the ARM architecture as an alternative to the x86 architecture, which has become increasingly complex over the years. This book should provide a solution for a growing need.

Many students have difficulty with the concept that a register can hold variable x at one point in the program, and hold variable y at some other point. They also often have difficulty with the concept that, before it can be involved in any computation, data has to be moved from memory into the CPU. Using a load-store architecture helps the students to more readily grasp these concepts.

Another common difficulty that students have is in relating the concepts of an address and a pointer variable. You can almost see the little light bulbs light up over their heads, when they have the “eureka!” moment and realize that pointers are just variables that hold an address. The author hopes that the approach taken in this book will make it easier for students to have that “eureka!” moment. The author believes that load-store architectures make that realization easier.

Many students also struggle with the concept of recursion, regardless of what language is used. In assembly, the mechanisms involved are exposed and directly manipulated by the programmer. Examples of recursion are scattered throughout this textbook. Again, the clean architecture of the ARM makes it much easier for the students to understand what is going on.

Some students have difficulty understanding the flow of a program, and tend to put many unnecessary branches into their code. Many assembly language courses spend so much time and space on learning the instruction set that they never have time to teach good programming practices. This textbook puts strong emphasis on using structured programming concepts. The relative simplicity of the ARM architecture makes this possible.

One of the major reasons to learn and use assembly language is that it allows the programmer to create very efficient mathematical routines. The concepts introduced in this book will enable students to perform efficient non-integral math on any processor. These techniques are rarely taught because of the time that it takes to cover the x86 instruction set. With the ARM processor, less time is spent on the instruction set, and more time can be spent teaching how to optimize the code.

The combination of the ARM processor and the Linux operating system provides the least costly hardware platform and development environment available. A cluster of 10 Raspberry Pis, or similar hosts, with power supplies and networking, can be assembled for 500 US dollars or less. This cluster can support up to 50 students logging in through ssh. If their client platform supports the X window system, then they can run GUI enabled applications. Alternatively, most low-cost ARM systems can directly drive a display and take input from a keyboard and mouse. With the addition of an NFS server (which itself could be a low-cost ARM system and a hard drive), an entire Linux ARM based laboratory of 20 workstations could be built for 250 US dollars per seat or less. Admittedly, it would not be a high-performance laboratory, but could be used to teach C, assembly, and other languages. The author would argue that inexperienced programmers should learn to program on low-performance machines, because it reinforces a life-long tendency towards efficiency.

The approach of this book is to present concepts in different ways throughout the book, slowly building from simple examples towards complex programming on bare-metal embedded systems. Students who don’t understand a concept when it is explained in a certain way may easily grasp the concept when it is presented later from a different viewpoint.

The main objective of this book is to provide an improved course in assembly language by replacing the x86 platform with one that is less costly, more ubiquitous, well-designed, powerful, and easier to learn. Since students are able to master the basics of assembly language quickly, it is possible to teach a wider range of topics, such as fixed and floating point mathematics, ethical considerations, performance tuning, and interrupt processing. The author hopes that courses using this book will better prepare students for the junior and senior level courses in operating systems, computer architecture, and compilers.

Please visit the companion web site to access additional resources. Instructors may download the author’s lecture slides and solution manual for the exercises. Students and instructors may also access the laboratory manual and additional code examples. The author welcomes suggestions for additional lecture slides, laboratory assignments, or other materials.

I would like to thank Randy Warner for reading the manuscript, catching errors, and making helpful suggestions. I would also like to thank the following students for suggesting exercises with answers and catching numerous errors in the drafts: Zach Buechler, Preston Cook, Joshua Daybrest, Matthew DeYoung, Josh Dodd, Matt Dyke, Hafiza Farzami, Jeremy Goens, Lawrence Hoffman, Colby Johnson, Benjamin Kaiser, Lauren Keene, Jayson Kjenstad, Murray LaHood-Burns, Derek Lane, Yanlin Li, Luke Meyer, Matthew Mielke, Forrest Miller, Christopher Navarro, Girik Ranchhod, Josh Schweigert, Christian Sieh, Weston Silbaugh, Jacob St. Amand, Njaal Tengesdal, Dylan Thoeny, Michael Vortherms, Dicheng Wu, and Kekoa (Peter) Yamaguchi. Finally, I am also very grateful for my assistants, Scott Logan, Ian Carlson, and Derek Stotz, who gave very valuable feedback during the writing of this book.

Assembly as a Language

This chapter first gives a very high-level description of the major components of function of a computer system. It then motivates the reader by giving reasons why learning assembly language is important for Computer Scientists and Computer Engineers. It then explains why the ARM processor is a good choice for a first assembly language. Next it explains binary data representations, including various integer formats, ASCII, and Unicode. Finally, it describes the memory sections for a typical program during execution. By the end of the chapter, the groundwork has been laid for learning to program in assembly language.

Instruction; Instruction stream; Central processing unit; Memory; Input/output device; High-level language; Assembly language; ARM processor; Binary; Hexadecimal; Decimal; Radix or base system; Base conversion; Sign magnitude; Unsigned; Complement; Excess-n; ASCII; Unicode; UTF-8; Stack; Heap; Data section; Text section

An executable computer program is, ultimately, just a series of numbers that have very little or no meaning to a human being. We have developed a variety of human-friendly languages in which to express computer programs, but in order for the program to execute, it must eventually be reduced to a stream of numbers. Assembly language is one step above writing the stream of numbers. The stream of numbers is called the instruction stream. Each number in the instruction stream instructs the computer to perform one (usually small) operation. Although each instruction does very little, the ability of the programmer to specify any sequence of instructions and the ability of the computer to perform billions of these small operations every second makes modern computers very powerful and flexible tools. In assembly language, one line of code usually gets translated into one machine instruction. In high-level languages, a single line of code may generate many machine instructions.

A simplified model of a computer system, as shown in Fig. 1.1, consists of memory, input/output devices, and a central processing unit (CPU), connected together by a system bus. The bus can be thought of as a roadway that allows data to travel between the components of the computer system. The CPU is the part of the system where most of the computation occurs, and the CPU controls the other devices in the system.

Memory can be thought of as a series of mailboxes. Each mailbox can hold a single postcard with a number written on it, and each mailbox has a unique numeric identifier. The identifier, x is called the memory address, and the number stored in the mailbox is called the contents of address x. Some of the mailboxes contain data, and others contain instructions which control what actions are performed by the CPU.

The CPU also contains a much smaller set of mailboxes, which we call registers. Data can be copied from cards stored in memory to cards stored in the CPU, or vice-versa. Once data has been copied into one of the CPU registers, it can be used in computation. For example, in order to add two numbers in memory, they must first be copied into registers on the CPU. The CPU can then add the numbers together and store the result in one of the CPU registers. The result of the addition can then be copied back into one of the mailboxes in the memory.

Modern computers execute instructions sequentially. In other words, the next instruction to be executed is at the memory address immediately following the current instruction. One of the registers in the CPU, the program counter (PC), keeps track of the location from which the next instruction is to be fetched. The CPU follows a very simple sequence of actions. It fetches an instruction from memory, increments the PC, executes the instruction, and then repeats the process with the next instruction. However, some instructions may change the PC, so that the next instruction is fetched from a non-sequential address.

There are many high-level programming languages, such as Java, Python, C, and C++ that have been designed to allow programmers to work at a high level of abstraction, so that they do not need to understand exactly what instructions are needed by a particular CPU. For compiled languages, such as C and C++, a compiler handles the task of translating the program, written in a high-level language, into assembly language for the particular CPU on the system. An assembler then converts the program from assembly language into the binary codes that the CPU reads as instructions.

High-level languages can greatly enhance programmer productivity. However, there are some situations where writing assembly code directly is desirable or necessary. For example, assembly language may be the best choice when writing

• the first steps in booting the computer,

• code to handle interrupts,

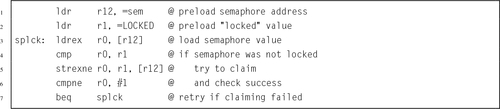

• low-level locking code for multi-threaded programs,

• code for machines where no compiler exists,

• code which needs to be optimized beyond the limits of the compiler,

• on computers with very limited memory, and

• code that requires low-level access to architectural and/or processor features.

Aside from sheer necessity, there are several other reasons why it is still important for computer scientists to learn assembly language.

One example where knowledge of assembly is indispensable is when designing and implementing compilers for high-level languages. As shown in Fig. 1.2, a typical compiler for a high-level language must generate assembly language as its output. Most compilers are designed to have multiple stages. In the input stage, the source language is read and converted into a graph representation. The graph may be optimized before being passed to the output, or code generation, stage where it is converted to assembly language. The assembly is then fed into the system’s assembler to generate an object file. The object file is linked with other object files (which are often combined into libraries) to create an executable program.

The code generation stage of a compiler must traverse the graph and emit assembly code. The quality of the assembly code that is generated can have a profound influence on the performance of the executable program. Therefore, the programmer responsible for the code generation portion of the compiler must be well versed in assembly programming for the target CPU.

Some people believe that a good optimizing compiler will generate better assembly code than a human programmer. This belief is not justified. Highly optimizing compilers have lots of clever algorithms, but like all programs, they are not perfect. Outside of the cases that they were designed for, they do not optimize well. Many newer CPUs have instructions which operate on multiple items of data at once. However, compilers rarely make use of these powerful single instruction multiple data ( SIMD) instructions. Instead, it is common for programmers to write functions in assembly language to take advantage of SIMD instructions. The assembly functions are assembled into object file(s), then linked with the object file(s) generated from the high-level language compiler.

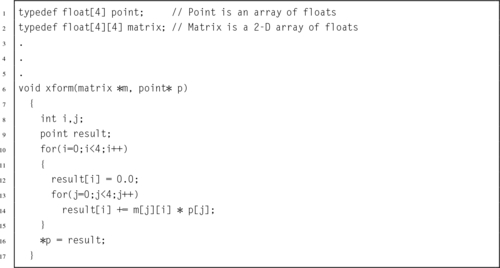

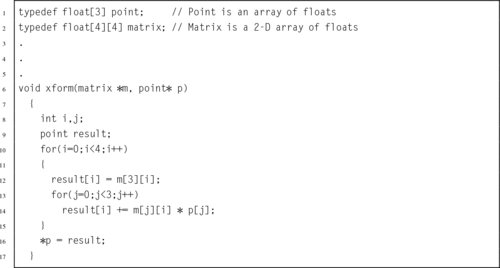

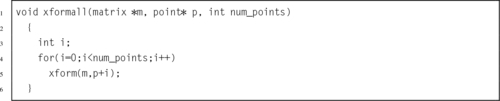

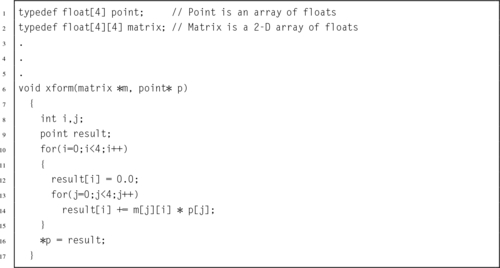

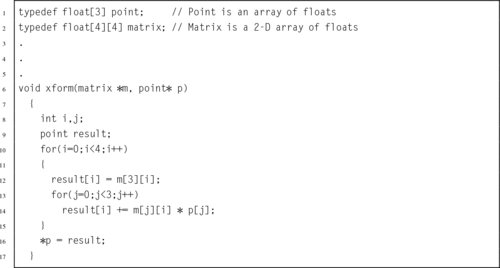

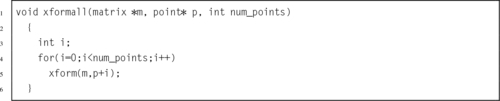

Many modern processors also have some support for processing vectors (arrays). Compilers are usually not very good at making effective use of the vector instructions. In order to achieve excellent vector performance for audio or video codecs and other time-critical code, it is often necessary to resort to small pieces of assembly code in the performance-critical inner loops. A good example of this type of code is when performing vector and matrix multiplies. Such operations are commonly needed in processing images and in graphical applications. The ARM vector instructions are explained in Chapter 9.

Another reason for assembly is when writing certain parts of an operating system. Although modern operating systems are mostly written in high-level languages, there are some portions of the code that can only be done in assembly. Typical uses of assembly language are when writing device drivers, saving the state of a running program so that another program can use the CPU, restoring the saved state of a running program so that it can resume executing, and managing memory and memory protection hardware. There are many other tasks central to a modern operating system which can only be accomplished in assembly language. Careful design of the operating system can minimize the amount of assembly required, but cannot eliminate it completely.

Another good reason to learn assembly is for debugging. Simply understanding what is going on “behind the scenes” of compiled languages such as C and C++ can be very valuable when trying to debug programs. If there is a problem in a call to a third party library, sometimes the only way a developer can isolate and diagnose the problem is to run the program under a debugger and step through it one machine instruction at a time. This does not require a deep knowledge of assembly language coding but at least a passing familiarity with assembly is helpful in that particular case. Analysis of assembly code is an important skill for C and C++ programmers, who may occasionally have to diagnose a fault by looking at the contents of CPU registers and single-stepping through machine instructions.

Assembly language is an important part of the path to understanding how the machine works. Even though only a small percentage of computer scientists will be lucky enough to work on the code generator of a compiler, they all can benefit from the deeper level of understanding gained by learning assembly language. Many programmers do not really understand pointers until they have written assembly language.

Without first learning assembly language, it is impossible to learn advanced concepts such as microcode, pipelining, instruction scheduling, out-of-order execution, threading, branch prediction, and speculative execution. There are many other concepts, especially when dealing with operating systems and computer architecture, which require some understanding of assembly language. The best programmers understand why some language constructs perform better than others, how to reduce cache misses, and how to prevent buffer overruns that destroy security.

Every program is meant to run on a real machine. Even though there are many languages, compilers, virtual machines, and operating systems to enable the programmer to use the machine more conveniently, the strengths and weaknesses of that machine still determine what is easy and what is hard. Learning assembly is a fundamental part of understanding enough about the machine to make informed choices about how to write efficient programs, even when writing in a high-level language.

As an analogy, most people do not need to know a lot about how an internal combustion engine works in order to operate an automobile. A race car driver needs a much better understanding of exactly what happens when he or she steps on the accelerator pedal in order to be able to judge precisely when (and how hard) to do so. Also, who would trust their car to a mechanic who could not tell the difference between a spark plug and a brake caliper? Worse still, should we trust an engineer to build a car without that knowledge? Even in this day of computerized cars, someone needs to know the gritty details, and they are paid well for that knowledge. Knowledge of assembly language is one of the things that defines the computer scientist and engineer.

When learning assembly language, the specific instruction set is not critically important, because what is really being learned is the fine detail of how a typical stored-program machine uses different storage locations and logic operations to convert a string of bits into a meaningful calculation. However, when it comes to learning assembly languages, some processors make it more difficult than it needs to be. Because some processors have an instruction set that is extremely irregular, non-orthogonal, large, and poorly designed, they are not a good choice for learning assembly. The author feels that teaching students their first assembly language on one of those processors should be considered a crime, or at least a form of mental abuse. Luckily, there are processors that are readily available, low-cost, and relatively easy to learn assembly with. This book uses one of them as the model for assembly language.

In the late 1970s, the microcomputer industry was a fierce battleground, with several companies competing to sell computers to small business and home users. One of those companies, based in the United Kingdom, was Acorn Computers Ltd. Acorn’s flagship product, the BBC Micro, was based on the same processor that Apple Computer had chosen for their Apple IITM line of computers; the 8-bit 6502 made by MOS Technology. As the 1980s approached, microcomputer manufacturers were looking for more powerful 16-bit and 32-bit processors. The engineers at Acorn considered the processor chips that were available at the time, and concluded that there was nothing available that would meet their needs for the next generation of Acorn computers.

The only reasonably-priced processors that were available were the Motorola 68000 (a 32-bit processor used in the Apple Macintosh and most high-end Unix workstations) and the Intel 80286 (a 16-bit processor used in less powerful personal computers such as the IBM PC). During the previous decade, a great deal of research had been conducted on developing high-performance computer architectures. One of the outcomes of that research was the development of a new paradigm for processor design, known as Reduced Instruction Set Computing (RISC). One advantage of RISC processors was that they could deliver higher performance with a much smaller number of transistors than the older Complex Instruction Set Computing (CISC) processors such as the 68000 and 80286. The engineers at Acorn decided to design and produce their own processor. They used the BBC Micro to design and simulate their new processor, and in 1987, they introduced the Acorn ArchimedesTM. The ArchimedesTM was arguably the most powerful home computer in the world at that time, with graphics and audio capabilities that IBM PCTM and Apple MacintoshTM users could only dream about. Thus began the long and successful dynasty of the Acorn RISC Machine (ARM) processor.

Acorn never made a big impact on the global computer market. Although Acorn eventually went out of business, the processor that they created has lived on. It was re-named to the Advanced RISC Machine, and is now known simply as ARM. Stewardship of the ARM processor belongs to ARM Holdings, LLC which manages the design of new ARM architectures and licenses the manufacturing rights to other companies. ARM Holdings does not manufacture any processor chips, yet more ARM processors are produced annually than all other processor designs combined. Most ARM processors are used as components for embedded systems and portable devices. If you have a smart phone or similar device, then there is a very good chance that it has an ARM processor in it. Because of its enormous market presence, clean architecture, and small, orthogonal instruction set, the ARM is a very good choice for learning assembly language.

Although it dominates the portable device market, the ARM processor has almost no presence in the desktop or server market. However, that may change. In 2012, ARM Holdings announced the ARM64 architecture, which is the first major redesign of the ARM architecture in 30 years. The ARM64 is intended to compete for the desktop and server market with other high-end processors such as the Sun SPARC and Intel Xeon. Regardless of whether or not the ARM64 achieves much market penetration, the original ARM 32-bit processor architecture is so ubiquitous that it clearly will be around for a long time.

The basic unit of data in a digital computer is the binary digit, or bit. A bit can have a value of zero or one. In order to store numbers larger than 1, bits are combined into larger units. For instance, using two bits, it is possible to represent any number between zero and three. This is shown in Table 1.1. When stored in the computer, all data is simply a string of binary digits. There is more than one way that such a fixed-length string of binary digits can be interpreted.

Computers have been designed using many different bit group sizes, including 4, 8, 10, 12, and 14 bits. Today most computers recognize a basic grouping of 8 bits, which we call a byte. Some computers can work in units of 4 bits, which is commonly referred to as a nibble (sometimes spelled “nybble”). A nibble is a convenient size because it can exactly represent one hexadecimal digit. Additionally, most modern computers can also work with groupings of 16, 32 and 64 bits. The CPU is designed with a default word size. For most modern CPUs, the default word size is 32 bits. Many processors support 64-bit words, which is increasingly becoming the default size.

A numeral system is a writing system for expressing numbers. The most common system is the Hindu-Arabic number system, which is now used throughout the world. Almost from the first day of formal education, children begin learning how to add, subtract, and perform other operations using the Hindu-Arabic system. After years of practice, performing basic mathematical operations using strings of digits between 0 and 9 seems natural. However, there are other ways to count and perform arithmetic, such as Roman numerals, unary systems, and Chinese numerals. With a little practice, it is possible to become as proficient at performing mathematics with other number systems as with the Hindu-Arabic system.

The Hindu-Arabic system is a base ten or radix ten system, because it uses the ten digits 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. For our purposes, the words radix and base are equivalent, and refer to the number of individual digits available in the numbering system. The Hindu-Arabic system is also a positional system, or a place-value notation, because the value of each digit in a number depends on its position in the number. The radix ten Hindu-Arabic system is only one of an infinite family of closely related positional systems. The members of this family differ only in the radix used (and therefore, the number of characters used). For bases greater than base ten, characters are borrowed from the alphabet and used to represent digits. For example, the first column in Table 1.2 shows the character “A” being used as a single digit representation for the number 10.

Table 1.2

The first 21 integers (starting with 0) in various bases

| Base | |||||||||

| 16 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 11 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 11 | 100 |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 101 |

| 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 20 | 110 |

| 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 21 | 111 |

| 8 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 20 | 22 | 1000 |

| 9 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 21 | 100 | 1001 |

| A | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 20 | 22 | 101 | 1010 |

| B | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 21 | 23 | 102 | 1011 |

| C | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 20 | 22 | 30 | 110 | 1100 |

| D | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 21 | 23 | 31 | 111 | 1101 |

| E | 14 | 15 | 16 | 20 | 22 | 24 | 32 | 112 | 1110 |

| F | 15 | 16 | 17 | 21 | 23 | 30 | 33 | 120 | 1111 |

| 10 | 16 | 17 | 20 | 22 | 24 | 31 | 100 | 121 | 10000 |

| 11 | 17 | 18 | 21 | 23 | 25 | 32 | 101 | 122 | 10001 |

| 12 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 24 | 30 | 33 | 102 | 200 | 10010 |

| 13 | 19 | 21 | 23 | 25 | 31 | 34 | 103 | 201 | 10011 |

| 14 | 20 | 22 | 24 | 26 | 32 | 40 | 110 | 201 | 10100 |

In base ten, we think of numbers as strings of the 10 digits, “0”–“9”. Each digit counts 10 times the amount of the digit to its right. If we restrict ourselves to integers, then the digit furthest to the right is always the ones digit. It is also referred to as the least significant digit. The digit immediately to the left of the ones digit is the tens digit. To the left of that is the hundreds digit, and so on. The leftmost digit is referred to as the most significant digit. The following equation shows how a number can be decomposed into its constituent digits:

Note that the subscript of “10” on 5783910 indicates that the number is given in base ten.

Imagine that we only had 7 digits: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. We need 10 digits for base ten, so with only 7 digits we are limited to base seven. In base seven, each digit in the string represents a power of seven rather than a power of ten. We can represent any integer in base seven, but it may take more digits than in base ten. Other than using a different base for the power of each digit, the math works exactly the same as for base ten. For example, suppose we have the following number in base seven: 3304257. We can convert this number to base ten as follows:

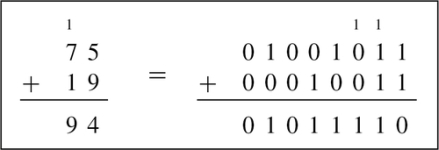

Base two, or binary is the “native” number system for modern digital systems. The reason for this is mainly because it is relatively easy to build circuits with two stable states: on and off (or 1 and 0). Building circuits with more than two stable states is much more difficult and expensive, and any computation that can be performed in a higher base can also be performed in binary. The least significant (rightmost) digit in binary is referred to as the least significant bit, or LSB, while the leftmost binary digit is referred to as the most significant bit, or MSB.

The most common bases used by programmers are base two (binary), base eight (octal), base ten (decimal) and base sixteen (hexadecimal). Octal and hexadecimal are common because, as we shall see later, they can be translated quickly and easily to and from base two, and are often easier for humans to work with than base two. Note that for base sixteen, we need 16 characters. We use the digits 0 through 9 plus the letters A through F. Table 1.2 shows the equivalents for all numbers between 0 and 20 in base two through base ten, and base sixteen.

Before learning assembly language it is essential to know how to convert from any base to any other base. Since we are already comfortable working in base ten, we will use that as an intermediary when converting between two arbitrary bases. For instance, if we want to convert a number in base three to base five, we will do it by first converting the base three number to base ten, then from base ten to base five. By using this two-stage process, we will only need to learn to convert between base ten and any arbitrary base b.

Converting from an arbitrary base b to base ten simply involves multiplying each base b digit d by bn, where n is the significance of digit d, and summing all of the results. For example, converting the base five number 34215 to base ten is performed as follows:

This conversion procedure works for converting any integer from any arbitrary base b to its equivalent representation in base ten. Example 1.1 gives another specific example of how to convert from base b to base ten.

Converting from base ten to an arbitrary base b involves repeated division by the base, b. After each division, the remainder is used as the next more significant digit in the base b number, and the quotient is used as the dividend for the next iteration. The process is repeated until the quotient is zero. For example, converting 5610 to base four is accomplished as follows:

Reading the remainders from right to left yields: 3204. This result can be double-checked by converting it back to base ten as follows:

Since we arrived at the same number we started with, we have verified that 5610 = 3204. This conversion procedure works for converting any integer from base ten to any arbitrary base b. Example 1.2 gives another example of converting from base ten to another base b.

Although it is possible to perform the division and multiplication steps in any base, most people are much better at working in base ten. For that reason, the easiest way to convert from any base a to any other base b is to use a two step process. First step is to convert from base a to decimal. The second step is to convert from decimal to base b. Example 1.3 shows how to convert from any base to any other base.

In addition to the methods above, there is a simple method for quickly converting between base two, base eight, and base sixteen. These shortcuts rely on the fact that 2, 8, and 16 are all powers of two. Because of this, it takes exactly four binary digits (bits) to represent exactly one hexadecimal digit. Likewise, it takes exactly three bits to represent an octal digit. Conversely, each hexadecimal digit can be converted to exactly four binary digits, and each octal digit can be converted to exactly three binary digits. This relationship makes it possible to do very fast conversions using the tables shown in Fig. 1.3.

When converting from hexadecimal to binary, all that is necessary is to replace each hex digit with the corresponding binary digits from the table. For example, to convert 5AC416 to binary, we just replace “5” with “0101,” replace “A” with “1010,” replace “C” with “1100,” and replace “4” with “0100.” So, just by referring to the table, we can immediately see that 5AC416 = 01011010110001002. This method works exactly the same for converting from octal to binary, except that it uses the table on the right side of Fig. 1.3.

Converting from binary to hexadecimal is also very easy using the table. Given a binary number, n, take the four least significant digits of n and find them in the table on the left side of Fig. 1.3. The hexadecimal digit on the matching line of the table is the least significant hex digit. Repeat the process with the next set of four bits and continue until there are no bits remaining in the binary number. For example, to convert 00111001010101112 to hexadecimal, just divide the number into groups of four bits, starting on the right, to get: 0011|1001|0101|01112. Now replace each group of four bits by looking up the corresponding hex digit in the table on the left side of Fig. 1.3, to convert the binary number to 395716. In the case where the binary number does not have enough bits, simply pad with zeros in the high-order bits. For example, dividing the number 10011000100112 into groups of four yields 1|0011|0001|00112 and padding with zeros in the high-order bits results in 0001|0011|0001|00112. Looking up the four groups in the table reveals that 0001|0011|0001|00112 = 131316.

The computer stores groups of bits, but the bits by themselves have no meaning. The programmer gives them meaning by deciding what the bits represent, and how they are interpreted. Interpreting a group of bits as unsigned integer data is relatively simple. Each bit is weighted by a power-of-two, and the value of the group of bits is the sum of the non-zero bits multiplied by their respective weights. However, programmers often need to represent negative as well as non-negative numbers, and there are many possibilities for storing and interpreting integers whose value can be both positive and negative. Programmers and hardware designers have developed several standard schemes for encoding such numbers. The three main methods for storing and interpreting signed integer data are two’s complement, sign-magnitude, and excess-N, Fig. 1.4 shows how the same binary pattern of bits can be interpreted as a number in four different ways.

The sign-magnitude representation simply reserves the most significant bit to represent the sign of the number, and the remaining bits are used to store the magnitude of the number. This method has the advantage that it is easy for humans to interpret, with a little practice. However, addition and subtraction are slightly complicated. The addition/subtraction logic must compare the sign bits, complement one of the inputs if they are different, implement an end-around carry, and complement the result if there was no carry from the most significant bit. Complements are explained in Section 1.3.3. Because of the complexity, most integer CPUs do not directly support addition and subtraction of integers in sign-magnitude form. However, this method is commonly used for mantissa in floating-point numbers, as will be explained in Chapter 8. Another drawback to sign-magnitude is that it has two representations for zero, which can cause problems if the programmer is not careful.

Another method for representing both positive and negative numbers is by using an excess-N representation. With this representation, the number that is stored is N greater than the actual value. This representation is relatively easy for humans to interpret. Addition and subtraction are easily performed using the complement method, which is explained in Section 1.3.3. This representation is just the same as unsigned math, with the addition of a bias which is usually (2n−1 − 1). So, zero is represented as zero plus the bias. In n = 12 bits, the bias is 212−1 − 1 = 204710, or 0111111111112. This method is commonly used to store the exponent in floating-point numbers, as will be explained in Chapter 8.

A very efficient method for dealing with signed numbers involves representing negative numbers as the radix complements of their positive counterparts. The complement is the amount that must be added to something to make it “whole.” For instance, in geometry, two angles are complementary if they add to 90°. In radix mathematics, the complement of a digit x in base b is simply b − x. For example, in base ten, the complement of 4 is 10 − 4 = 6.

In complement representation, the most significant digit of a number is reserved to indicate whether or not the number is negative. If the first digit is less than  (where b is the radix), then the number is positive. If the first digit is greater than or equal to

(where b is the radix), then the number is positive. If the first digit is greater than or equal to  , then the number is negative. The first digit is not part of the magnitude of the number, but only indicates the sign of the number. For example, numbers in ten’s complement notation are positive if the first digit is less than 5, and negative if the first digit is greater than 4. This works especially well in binary, since the number is considered positive if the first bit is zero and negative if the first bit is one. The magnitude of a negative number can be obtained by taking the radix complement. Because of the nice properties of the complement representation, it is the most common method for representing signed numbers in digital computers.

, then the number is negative. The first digit is not part of the magnitude of the number, but only indicates the sign of the number. For example, numbers in ten’s complement notation are positive if the first digit is less than 5, and negative if the first digit is greater than 4. This works especially well in binary, since the number is considered positive if the first bit is zero and negative if the first bit is one. The magnitude of a negative number can be obtained by taking the radix complement. Because of the nice properties of the complement representation, it is the most common method for representing signed numbers in digital computers.

Finding the complement: The radix complement of an n digit number y in radix ( base) b is defined as

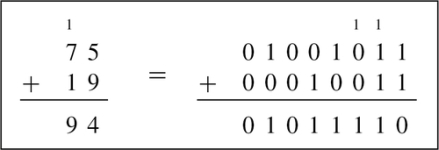

For example, the ten’s complement of the four digit number 873410 is 104 − 8734 = 1266. In this example, we directly applied the definition of the radix complement from Eq. (1.4). That is easy in base ten, but not so easy in an arbitrary base, because it involves performing a subtraction. However, there is a very simple method for calculating the complement which does not require subtraction. This method involves finding the diminished radix complement, which is (bn − 1) − y by substituting each digit with its complement from a complement table. The radix complement is found by adding one to the diminished radix complement. Fig. 1.5 shows the complement tables for bases ten and two. Examples 1.4 and 1.5 show how the complement is obtained in bases ten and two respectively. Examples 1.6 and 1.7 show additional conversions between binary and decimal.

Subtraction using complements One very useful feature of complement notation is that it can be used to perform subtraction by using addition. Given two numbers in base b, xb, and yb, the difference can be computed as:

where C(yb) is the radix complement of yb. Assume that xb and yb are both positive where yb ≤ xb and both numbers have the same number of digits n (yb may have leading zeros). In this case, the result of xb + C(yb) will always be greater than or equal to bn, but less than 2 × bn. This means that the result of xb + C(yb) will always begin with a ‘1’ in the n + 1 digit position. Dropping the initial ‘1’ is equivalent to subtracting bn, making the result x − y + bn − bn or just x − y, which is the desired result. This can be reduced to a simple procedure. When y and x are both positive and y ≤ x, the following four steps are to be performed:

1. pad the subtrahend (y) with leading zeros, as necessary, so that both numbers have the same number of digits (n),

2. find the b’s complement of the subtrahend,

3. add the complement to the minuend,

4. discard the leading ‘1’.

The complement notation provides a very easy way to represent both positive and negative integers using a fixed number of digits, and to perform subtraction by using addition. Since modern computers typically use a fixed number of bits, complement notation provides a very convenient and efficient way to store signed integers and perform mathematical operations on them. Hardware is simplified because there is no need to build a specialized subtractor circuit. Instead, a very simple complement circuit is built and the adder is reused to perform subtraction as well as addition.

In the previous section, we discussed how the computer stores information as groups of bits, and how we can interpret those bits as numbers in base two. Given that the computer can only store information using groups of bits, how can we store textual information? The answer is that we create a table, which assigns a numerical value to each character in our language.

Early in the development of computers, several computer manufacturers developed such tables, or character coding schemes. These schemes were incompatible and computers from different manufacturers could not easily exchange textual data without the use of translation software to convert the character codes from one coding scheme to another.

Eventually, a standard coding scheme, known as the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) was developed. Work on the ASCII standard began on October 6, 1960, with the first meeting of the American Standards Association’s (ASA) X3.2 subcommittee. The first edition of the standard was published in 1963. The standard was updated in 1967 and again in 1986, and has been stable since then. Within a few years of its development, ASCII was accepted by all major computer manufacturers, although some continue to support their own coding schemes as well.

ASCII was designed for American English, and does not support some of the characters that are used by non-English languages. For this reason, ASCII has been extended to create more comprehensive coding schemes. Most modern multilingual coding schemes are based on ASCII, though they support a wider range of characters.

At the time that it was developed, transmission of digital data over long distances was very slow, and usually involved converting each bit into an audio signal which was transmitted over a telephone line using an acoustic modem. In order to maximize performance, the standards committee chose to define ASCII as a 7-bit code. Because of this decision, all textual data could be sent using seven bits rather than eight, resulting in approximately 10% better overall performance when transmitting data over a telephone modem. A possibly unforeseen benefit was that this also provided a way for the code to be extended in the future. Since there are 128 possible values for a 7-bit number, the ASCII standard provides 128 characters. However, 33 of the ASCII characters are non-printing control characters. These characters, shown in Table 1.3, are mainly used to send information about how the text is to be displayed and/or printed. The remaining 95 printable characters are shown in Table 1.4.

Table 1.3

The ASCII control characters

| Binary | Oct | Dec | Hex | Abbr | Glyph | Name |

| 000 0000 | 000 | 0 | 00 | NUL | ˆ@ | Null character |

| 000 0001 | 001 | 1 | 01 | SOH | ˆA | Start of header |

| 000 0010 | 002 | 2 | 02 | STX | ˆB | Start of text |

| 000 0011 | 003 | 3 | 03 | ETX | ˆC | End of text |

| 000 0100 | 004 | 4 | 04 | EOT | ˆD | End of transmission |

| 000 0101 | 005 | 5 | 05 | ENQ | ˆE | Enquiry |

| 000 0110 | 006 | 6 | 06 | ACK | ˆF | Acknowledgment |

| 000 0111 | 007 | 7 | 07 | BEL | ˆG | Bell |

| 000 1000 | 010 | 8 | 08 | BS | ˆH | Backspace |

| 000 1001 | 011 | 9 | 09 | HT | ˆI | Horizontal tab |

| 000 1010 | 012 | 10 | 0A | LF | ˆJ | Line feed |

| 000 1011 | 013 | 11 | 0B | VT | ˆK | Vertical tab |

| 000 1100 | 014 | 12 | 0C | FF | ˆL | Form feed |

| 000 1101 | 015 | 13 | 0D | CR | ˆM | Carriage return[g] |

| 000 1110 | 016 | 14 | 0E | SO | ˆN | Shift out |

| 000 1111 | 017 | 15 | 0F | SI | ˆO | Shift in |

| 001 0000 | 020 | 16 | 10 | DLE | ˆP | Data link escape |

| 001 0001 | 021 | 17 | 11 | DC1 | ˆQ | Device control 1 (oft. XON) |

| 001 0010 | 022 | 18 | 12 | DC2 | ˆR | Device control 2 |

| 001 0011 | 023 | 19 | 13 | DC3 | ˆS | Device control 3 (oft. XOFF) |

| 001 0100 | 024 | 20 | 14 | DC4 | ˆT | Device control 4 |

| 001 0101 | 025 | 21 | 15 | NAK | ˆU | Negative acknowledgement |

| 001 0110 | 026 | 22 | 16 | SYN | ˆV | Synchronous idle |

| 001 0111 | 027 | 23 | 17 | ETB | ˆW | End of transmission Block |

| 001 1000 | 030 | 24 | 18 | CAN | ˆX | Cancel |

| 001 1001 | 031 | 25 | 19 | EM | ˆY | End of medium |

| 001 1010 | 032 | 26 | 1A | SUB | ˆZ | Substitute |

| 001 1011 | 033 | 27 | 1B | ESC | ˆ[ | Escape |

| 001 1100 | 034 | 28 | 1C | FS | ˆ\ | File separator |

| 001 1101 | 035 | 29 | 1D | GS | ˆ] | Group separator |

| 001 1110 | 036 | 30 | 1E | RS | ˆˆ | Record separator |

| 001 1111 | 037 | 31 | 1F | US | ˆ_ | Unit separator |

| 111 1111 | 177 | 127 | 7F | DEL | ˆ? | Delete |

Table 1.4

The ASCII printable characters

| Binary | Oct | Dec | Hex | Glyph |

| 010 0000 | 040 | 32 | 20 | _ |

| 010 0001 | 041 | 33 | 21 | ! |

| 010 0010 | 042 | 34 | 22 | ” |

| 010 0011 | 043 | 35 | 23 | # |

| 010 0100 | 044 | 36 | 24 | $ |

| 010 0101 | 045 | 37 | 25 | % |

| 010 0110 | 046 | 38 | 26 | & |

| 010 0111 | 047 | 39 | 27 | ’ |

| 010 1000 | 050 | 40 | 28 | ( |

| 010 1001 | 051 | 41 | 29 | ) |

| 010 1010 | 052 | 42 | 2A | * |

| 010 1011 | 053 | 43 | 2B | + |

| 010 1100 | 054 | 44 | 2C | , |

| 010 1101 | 055 | 45 | 2D | − |

| 010 1110 | 056 | 46 | 2E | . |

| 010 1111 | 057 | 47 | 2F | / |

| 011 0000 | 060 | 48 | 30 | 0 |

| 011 0001 | 061 | 49 | 31 | 1 |

| 011 0010 | 062 | 50 | 32 | 2 |

| 011 0011 | 063 | 51 | 33 | 3 |

| 011 0100 | 064 | 52 | 34 | 4 |

| 011 0101 | 065 | 53 | 35 | 5 |

| 011 0110 | 066 | 54 | 36 | 6 |

| 011 0111 | 067 | 55 | 37 | 7 |

| 011 1000 | 070 | 56 | 38 | 8 |

| 011 1001 | 071 | 57 | 39 | 9 |

| 011 1010 | 072 | 58 | 3A | : |

| 011 1011 | 073 | 59 | 3B | ; |

| 011 1100 | 074 | 60 | 3C | < |

| 011 1101 | 075 | 61 | 3D | = |

| 011 1110 | 076 | 62 | 3E | > |

| 011 1111 | 077 | 63 | 3F | ? |

| 100 0000 | 100 | 64 | 40 | @ |

| 100 0001 | 101 | 65 | 41 | A |

| 100 0010 | 102 | 66 | 42 | B |

| 100 0011 | 103 | 67 | 43 | C |

| 100 0100 | 104 | 68 | 44 | D |

| 100 0101 | 105 | 69 | 45 | E |

| 100 0110 | 106 | 70 | 46 | F |

| 100 0111 | 107 | 71 | 47 | G |

| 100 1000 | 110 | 72 | 48 | H |

| 100 1001 | 111 | 73 | 49 | I |

| 100 1010 | 112 | 74 | 4A | J |

| 100 1011 | 113 | 75 | 4B | K |

| 100 1100 | 114 | 76 | 4C | L |

| 100 1101 | 115 | 77 | 4D | M |

| 100 1110 | 116 | 78 | 4E | N |

| 100 1111 | 117 | 79 | 4F | O |

| 101 0000 | 120 | 80 | 50 | P |

| 101 0001 | 121 | 81 | 51 | Q |

| 101 0010 | 122 | 82 | 52 | R |

| 101 0011 | 123 | 83 | 53 | S |

| 101 0100 | 124 | 84 | 54 | T |

| 101 0101 | 125 | 85 | 55 | U |

| 101 0110 | 126 | 86 | 56 | V |

| 101 0111 | 127 | 87 | 57 | W |

| 101 1000 | 130 | 88 | 58 | X |

| 101 1001 | 131 | 89 | 59 | Y |

| 101 1010 | 132 | 90 | 5A | Z |

| 101 1011 | 133 | 91 | 5B | [ |

| 101 1100 | 134 | 92 | 5C | \ |

| 101 1101 | 135 | 93 | 5D | ] |

| 101 1110 | 136 | 94 | 5E | ˆ |

| 101 1111 | 137 | 95 | 5F | _ |

| 110 0000 | 140 | 96 | 60 | ‘ |

| 110 0001 | 141 | 97 | 61 | a |

| 110 0010 | 142 | 98 | 62 | b |

| 110 0011 | 143 | 99 | 63 | c |

| 110 0100 | 144 | 100 | 64 | d |

| 110 0101 | 145 | 101 | 65 | e |

| 110 0110 | 146 | 102 | 66 | f |

| 110 0111 | 147 | 103 | 67 | g |

| 110 1000 | 150 | 104 | 68 | h |

| 110 1001 | 151 | 105 | 69 | i |

| 110 1010 | 152 | 106 | 6A | j |

| 110 1011 | 153 | 107 | 6B | k |

| 110 1100 | 154 | 108 | 6C | l |

| 110 1101 | 155 | 109 | 6D | m |

| 110 1110 | 156 | 110 | 6E | n |

| 110 1111 | 157 | 111 | 6F | o |

| 111 0000 | 160 | 112 | 70 | p |

| 111 0001 | 161 | 113 | 71 | q |

| 111 0010 | 162 | 114 | 72 | r |

| 111 0011 | 163 | 115 | 73 | s |

| 111 0100 | 164 | 116 | 74 | t |

| 111 0101 | 165 | 117 | 75 | u |

| 111 0110 | 166 | 118 | 76 | v |

| 111 0111 | 167 | 119 | 77 | w |

| 111 1000 | 170 | 120 | 78 | x |

| 111 1001 | 171 | 121 | 79 | y |

| 111 1010 | 172 | 122 | 7A | z |

| 111 1011 | 173 | 123 | 7B | { |

| 111 1100 | 174 | 124 | 7C | | |

| 111 1101 | 175 | 125 | 7D | } |

| 111 1110 | 176 | 126 | 7E | ˜ |

The non-printing characters are used to provide hints or commands to the device that is receiving, displaying, or printing the data. The FF character, when sent to a printer, will cause the printer to eject the current page and begin a new one. The LF character causes the printer or terminal to end the current line and begin a new one. The CR character causes the terminal or printer to move to the beginning of the current line. Many text editing programs allow the user to enter these non-printing characters by using the control key on the keyboard. For instance, to enter the BEL character, the user would hold the control key down and press the G key. This character, when sent to a character display terminal, will cause it to emit a beep. Many of the other control characters can be used to control specific features of the printer, display, or other device that the data is being sent to.

Suppose we wish to covert a string of characters, such as “Hello World” to an ASCII representation. We can use an 8-bit byte to store each character. Also, it is common practice to include an additional byte at the end of the string. This additional byte holds the ASCII NUL character, which indicates the end of the string. Such an arrangement is referred to as a null-terminated string.

To convert the string “Hello World” into a null-terminated string, we can build a table with each character on the left and its equivalent binary, octal, hexadecimal, or decimal value (as defined in the ASCII table) on the right. Table 1.5 shows the characters in “Hello World” and their equivalent binary representations, found by looking in Table 1.4. Since most modern computers use 8-bit bytes (or multiples thereof) as the basic storage unit, an extra zero bit is shown in the most significant bit position.

Table 1.5

Binary equivalents for each character in “Hello World”

| Character | Binary |

| H | 01001000 |

| e | 01100101 |

| l | 01101100 |

| l | 01101100 |

| o | 01101111 |

| 00100000 | |

| W | 01010111 |

| o | 01101111 |

| r | 01110010 |

| l | 01101100 |

| d | 01100100 |

| NUL | 00000000 |

Reading the Binary column from top to bottom results in the following sequence of bytes: 01001000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111 00100000 01010111 01101111 01110010 01101100 01100100 0000000. To convert the same string to a hexadecimal representation, we can use the shortcut method that was introduced previously to convert each 4-bit nibble into its hexadecimal equivalent, or read the hexadecimal value from the ASCII table. Table 1.6 shows the result of extending Table 1.5 to include hexadecimal and decimal equivalents for each character. The string can now be converted to hexadecimal or decimal simply by reading the correct column in the table. So “Hello World” expressed as a null-terminated string in hexadecimal is “48 65 6C 6C 6F 20 57 6F 62 6C 64 00” and in decimal it is ”72 101 108 108 111 32 87 111 98 108 100 0”.

Table 1.6

Binary, hexadecimal, and decimal equivalents for each character in “Hello World”

| Character | Binary | Hexadecimal | Decimal |

| H | 01001000 | 48 | 72 |

| e | 01100101 | 65 | 101 |

| l | 01101100 | 6C | 108 |

| l | 01101100 | 6C | 108 |

| o | 01101111 | 6F | 111 |

| 00100000 | 20 | 32 | |

| W | 01010111 | 57 | 87 |

| o | 01101111 | 6F | 111 |

| r | 01110010 | 62 | 98 |

| l | 01101100 | 6C | 108 |

| d | 01100100 | 64 | 100 |

| NUL | 00000000 | 00 | 0 |

It is sometimes necessary to convert a string of bytes in hexadecimal into ASCII characters. This is accomplished simply by building a table with the hexadecimal value of each byte in the left column, then looking in the ASCII table for each value and entering the equivalent character representation in the right column. Table 1.7 shows how the ASCII table is used to interpret the hexadecimal string “466162756C6F75732100” as an ASCII string.

ASCII was developed to encode all of the most commonly used characters in North American English text. The encoding uses only 128 of the 256 codes that are available in a 8-bit byte. ASCII does not include symbols frequently used in other countries, such as the British pound symbol (£) or accented characters (ü). However, the International Standards Organization (ISO) has created several extensions to ASCII to enable the representation of characters from a wider variety of languages.

The ISO has defined a set of related standards known collectively as ISO 8859. ISO 8859 is an 8-bit extension to ASCII which includes the 128 ASCII characters along with an additional 128 characters, such as the British Pound symbol and the American cent symbol. Several variations of the ISO 8859 standard exist for different language families. Table 1.8 provides a brief description of the various ISO standards.

Table 1.8

Variations of the ISO 8859 standard

| Name | Alias | Languages |

| ISO8859-1 | Latin-1 | Western European languages |

| ISO8859-2 | Latin-2 | Non-Cyrillic Central and Eastern European languages |

| ISO8859-3 | Latin-3 | Southern European languages and Esperanto |

| ISO8859-4 | Latin-4 | Northern European and Baltic languages |

| ISO8859-5 | Latin/Cyrillic | Slavic languages that use a Cyrillic alphabet |

| ISO8859-6 | Latin/Arabic | Common Arabic language characters |

| ISO8859-7 | Latin/Greek | Modern Greek language |

| ISO8859-8 | Latin/Hebrew | Modern Hebrew languages |

| ISO8859-9 | Latin-5 | Turkish |

| ISO8859-10 | Latin-6 | Nordic languages |

| ISO8859-11 | Latin/Thai | Thai language |

| ISO8859-12 | Latin/Devanagari | Never completed. Abandoned in 1997 |

| ISO8859-13 | Latin-7 | Some Baltic languages not covered by Latin-4 or Latin-6 |

| ISO8859-14 | Latin-8 | Celtic languages |

| ISO8859-15 | Latin-9 | Update to Latin-1 that replaces some characters. Most |

| notably, it includes the euro symbol (€), which did not | ||

| exist when Latin-1 was created | ||

| ISO8859-16 | Latin-10 | Covers several languages not covered by Latin-9 and |

| includes the euro symbol (€) |

Although the ISO extensions helped to standardize text encodings for several languages that were not covered by ASCII, there were still some issues. The first issue is that the display and input devices must be configured for the correct encoding, and displaying or printing documents with multiple encodings requires some mechanism for changing the encoding on-the-fly. Another issue has to do with the lexicographical ordering of characters. Although two languages may share a character, that character may appear in a different place in the alphabets of the two languages. This leads to issues when programmers need to sort strings into lexicographical order. The ISO extensions help to unify character encodings across multiple languages, but do not solve all of the issues involved in defining a universal character set.

In the late 1980s, there was growing interest in developing a universal character encoding for all languages. People from several computer companies worked together and, by 1990, had developed a draft standard for Unicode. In 1991, the Unicode Consortium was formed and charged with guiding and controlling the development of Unicode. The Unicode Consortium has worked closely with the ISO to define, extend, and maintain the international standard for a Universal Character Set (UCS). This standard is known as the ISO/IEC 10646 standard. The ISO/IEC 10646 standard defines the mapping of code points (numbers) to glyphs (characters). but does not specify character collation or other language-dependent properties. UCS code points are commonly written in the form U+XXXX, where XXXX in the numerical code point in hexadecimal. For example, the code point for the ASCII DEL character would be written as U+007F. Unicode extends the ISO/IEC standard and specifies language-specific features.

Originally, Unicode was designed as a 16-bit encoding. It was not fully backward-compatible with ASCII, and could encode only 65,536 code points. Eventually, the Unicode character set grew to encompass 1,112,064 code points, which requires 21 bits per character for a straightforward binary encoding. By early 1992, it was clear that some clever and efficient method for encoding character data was needed.

UTF-8 (UCS Transformation Format-8-bit) was proposed and accepted as a standard in 1993. UTF-8 is a variable-width encoding that can represent every character in the Unicode character set using between one and four bytes. It was designed to be backward compatible with ASCII and to avoid the major issues of previous encodings. Code points in the Unicode character set with lower numerical values tend to occur more frequently than code points with higher numerical values. UTF-8 encodes frequently occurring code points with fewer bytes than those which occur less frequently. For example, the first 128 characters of the UTF-8 encoding are exactly the same as the ASCII characters, requiring only 7 bits to encode each ASCII character. Thus any valid ASCII text is also valid UTF-8 text. UTF-8 is now the most common character encoding for the World Wide Web, and is the recommended encoding for email messages.

In November 2003, UTF-8 was restricted by RFC 3629 to end at code point 10FFFF16. This allows UTF-8 to encode 1,114,111 code points, which is slightly more than the 1,112,064 code points defined in the ISO/IEC 10646 standard. Table 1.9 shows how ISO/IEC 10646 code points are mapped to a variable-length encoding in UTF-8. Note that the encoding allows each byte in a stream of bytes to be placed in one of the following three distinct categories:

Table 1.9

UTF-8 encoding of the ISO/IEC 10646 code points

| First | Last | ||||||