Structured Programming

Abstract

This chapter first introduces the structured programming concepts and describes the principles of good software design. It then shows how the language elements covered in the previous three chapters are used to create the elements required by structured programming, giving comparative examples of these elements in C and assembly language. It covers programming elements for sequencing, selection, and iteration. Then it covers in greater detail how to access the standard C library functions from assembly language, and how to access assembly language functions from C. It then explains how automatic variables are allocated, and covers writing recursive functions in assembly language. Finally, it explains the implementation of C structs and shows how they can be accessed from assembly language, then covers arrays in the same way.

Keywords

Structured programming; Sequencing; Selection; Iteration; Loop; Subroutine; Function; Recursion; Struct; Aggregate data; Array

Before IBM released FORTRAN in 1957, almost all programming was done in assembly language. Part of the reason for this is that nobody knew how to design a good high-level language, nor did they know how to write a compiler to generate efficient code. Early attempts at high-level languages resulted in languages that were not well structured, difficult to read, and difficult to debug. The first release of FORTRAN was not a particularly elegant language by today’s standards, but it did generate efficient code.

In the 1960s, a new paradigm for designing high-level languages emerged. This new paradigm emphasized grouping program statements into blocks of code that execute from beginning to end. These basic blocks have only one entry point and one exit point. Control of which basic blocks are executed, and in what order, is accomplished with highly structured flow control statements. The structured program theorem provides the theoretical basis of structured programming. It states that there are three ways of combining basic blocks: sequencing, selection, and iteration. These three mechanisms are sufficient to express any computable function. It has been proven that all programs can be written using only basic blocks, the pre-test loop, and if-then-else structure. Although most high-level languages provide additional statements for the convenience of the programmer, they are just “syntactical sugar.” Other structured programming concepts include well-formed functions and procedures, pass-by-reference and pass-by-value, separate compilation, and information hiding.

These structured programming languages enabled programmers to become much more productive. Well-written programs that adhere to structured programming principles are much easier to write, understand, debug, and maintain. Most successful high-level languages are designed to enforce, or at least facilitate, good programming techniques. This is not generally true for assembly language. The burden of writing a well-structured code lies with the programmer, and not with the language.

The best assembly programmers rely heavily on structured programming concepts. Failure to do so results in code that contains unnecessary branch instructions and, in the worst cases, results in something called spaghetti code. Consider a code listing where a line has been drawn from each branch instruction to its destination. If the result looks like someone spilled a plate of spaghetti on the page, then the listing is spaghetti code. If a program is spaghetti code, then the flow of control is difficult to follow. Spaghetti code is much more likely to have bugs and is extremely difficult to debug. If the flow of control is too complex for the programmer to follow, then it cannot be adequately debugged. It is the responsibility of the assembly language programmer to write code that uses a block-structured approach.

Adherence to structured programming principles results in code that has a much higher probability of working correctly. Well-written code also has fewer branch statements, making the percentage of data processing statements versus branch statements is higher. High data processing density results in higher throughput of data. In other words, writing code in a structured manner leads to higher efficiency.

5.1 Sequencing

Sequencing simply means executing statements (or instructions) in a linear sequence. When statement n is completed, statement n + 1 will be executed next. Uninterrupted sequences of statements form basic blocks. Basic blocks have exactly one entry point and one exit point. Flow control is used to select which basic block should be executed next.

5.2 Selection

The first control structure that we will examine is the basic selection construct. It is called selection because it selects one of the two (or possibly more) blocks of code to execute, based on some condition. In its most general form, the condition could be computed in a variety of ways, but most commonly it is the result of some comparison operation or the result of evaluating a Boolean expression.

Most languages support selection in the form of an if-then-else statement. Selection can be implemented very easily in ARM assembly language with a two-stage process:

1. perform an operation that updates the CPSR flags, and

2. use conditional execution to select a block of instructions to execute.

Because the ARM architecture supports conditional execution on almost every instruction, there are two basic ways to implement this control structure: by using conditional execution on all instructions in a block, or by using branch instructions. The conditional execution can be applied directly to instructions following the flag update, or to branch instructions that transfer execution to another location. Listing 5.1 shows a typical if-then-else statement in C.

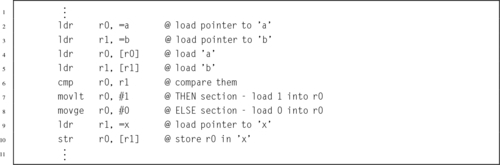

5.2.1 Using Conditional Execution

Listing 5.2 shows the ARM code equivalent to Listing 5.1, using conditional execution. The then and else are written with one instruction each on lines 7 and 8. The then section is written as a conditional instruction with the lt condition attached. The else section is a single instruction with the opposite (ge) condition. Therefore only one of the two instructions will actually execute, depending on the results of the cmp instruction. If there are three or fewer instructions in each block that can be selected, then this is the preferred and most efficient method of writing the bodies of the then and else selections.

5.2.2 Using Branch Instructions

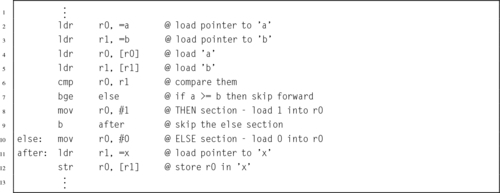

Listing 5.3 shows the ARM code equivalent to Listing 5.1, using branch instructions. Note that this method requires a conditional branch, an unconditional branch, and two labels. If there are more than three instructions in either basic block, then this is the preferred and most efficient method of writing the bodies of the then and else selections.

5.2.3 Complex Selection

More complex selection structures should be written with care. Listing 5.4 shows a fragment of C code which compares the variables a, b, and c, and sets the variable x to the least of the three values. In C, Boolean expressions use short-circuit evaluation. For example, consider the Boolean AND operator in the expression ((a<b)&&(a<c)). If the first sub-expression evaluates to false, then the truth value of the complete expression can be immediately determined to be false, so the second sub-expression is not evaluated. This usually results in the compiler generating very efficient assembly code. Good programmers can take advantage of short-circuiting by checking array bounds early in a Boolean expression and accessing array elements later in the expression. For example, the expression ((i<15)&&(array[i]<0)) makes sure that the index i is less than 15 before attempting to access the array. If the index is greater than 14, the array access will not take place. This prevents the program from attempting to access the 16th element on an array that has only 15 elements.

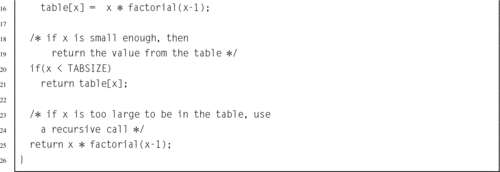

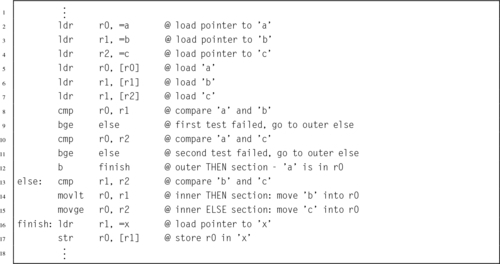

Listing 5.5 shows an ARM assembly code fragment which is equivalent to Listing 5.4. In this code fragment, r0 is used to store a temporary value for the variable x, and the value is only stored to memory once at the end of the fragment of code. The outer if-then-else statement is implemented using branch instructions. The first comparison is performed on line 8. If the comparison evaluates to false, then it immediately branches to the else block of the outer if-then-else statement. But if the first comparison evaluates to true, then it performs the second comparison. Again, if that comparison evaluates to false, then it branches to the else block of the outer if-then-else statement. If both comparisons evaluate to true, then it executes the then block of the outer if-then-else statement, and then branches to the statement following the else block.

The if-then-else statement on line 5 of Listing 5.4 is implemented using conditional execution. The comparison is performed on line 13 of Listing 5.5. Lines 14 and 15 contain instructions that are conditionally executed. Since they have complementary conditions, it is guaranteed that one of them will move a value into r0. The comparison on line 13 determines which statement executes.

Note that the number of comparisons performed will always be minimized, and the number of branches has also been minimized. The only way that line 13 can be reached is if one of the first two comparisons evaluates to false. If line 2 is executed, then no matter which sequence of events occurs, the program fragment will always reach line 16 and a value will be stored in x. Thus, the ARM assembly code fragment in Listing 5.5 can be considered to be a block of code with exactly one entry point and one exit point.

When writing nested selection structures, it is important to maintain a block structure, even if the bodies of the blocks consist of only a single instruction. It is often very helpful to write the algorithm in pseudo-code or a high-level language, such as C or Java, before converting it to assembly. Prolific commenting of the code is also strongly encouraged.

5.3 Iteration

Iteration involves the transfer of control from a statement in a sequence to a previous statement in the sequence. The simplest type of iteration is the unconditional loop, also known as the infinite loop. This type of loop may be used in programs or tasks that should continue running indefinitely. Listing 5.6 shows an ARM assembly fragment containing an unconditional loop. Few high-level languages provide a true unconditional loop, but the high-level programmer can achieve a similar effect by using a conditional loop and specifying a condition that always evaluates to true.

5.3.1 Pre-Test Loop

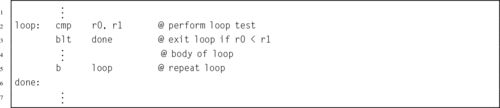

A pre-test loop is a loop in which a test is performed before the block of instructions forming the loop body is executed. If the test evaluates to true, then the loop body is executed. The last instruction in the loop body is a branch back to the beginning of the test. If the test evaluates to false, then execution branches to the first instruction following the loop body. All structured programming languages have a pre-test loop construct. For example, in C, the pre-test loop is called a while loop. In assembly, a pre-test loop is constructed very similarly to an if-then statement. The only difference is that it includes an additional branch instruction at the end of the sequence of instructions that form the body. Listing 5.7 shows a pre-test loop in ARM assembly.

5.3.2 Post-Test Loop

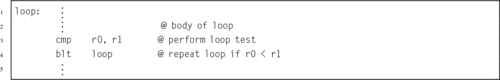

In a post-test loop, the test is performed after the loop body is executed. If the test evaluates to true, then execution branches to the first instruction in the loop body. Otherwise, execution continues sequentially. Most structured programming languages have a post-test loop construct. For example, in C, the post-test loop is called a do-while loop. Listing 5.8 shows a post-test loop in ARM assembly. The body of a post-test loop will always be executed at least once.

5.3.3 For Loop

Many structured programming languages have a for loop construct, which is a type of counting loop. The for loop is not essential, and is only included as a matter of syntactical convenience. In some cases, a for loop is easier to write and understand than an equivalent pre-test or post-test loop. However, with the addition of an if-then construct, any loop can be implemented as a pre-test loop. The following sections show how loops can be converted from one form to another.

Pre-test conversion

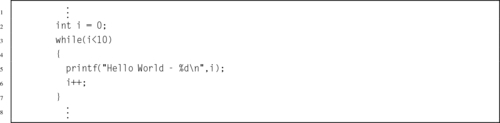

Listing 5.9 shows a simple C program with a for loop. The program prints “Hello World” 10 times, appending an integer to the end of each line.

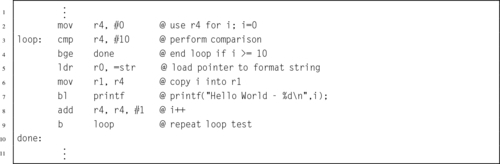

In order to write an equivalent program in assembly, the programmer must first rewrite the for loop as a pre-test loop. Listing 5.10 shows the program rewritten so that it is easier to translate into assembly. Note that the initialization of the loop variable has been moved to its own line before the while statement. Also, the loop variable is modified on the last line of the loop body. This is a straightforward conversion from one type of loop to another type. Listing 5.11 shows a translation of the pre-test loop structure into ARM assembly.

Post-test conversion

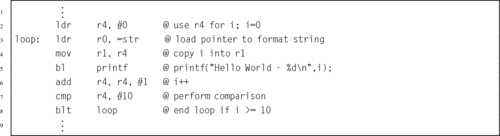

If the programmer can guarantee that the body of a for loop will always execute at least once, then the for loop can be converted to an equivalent post-test loop. This form of loop is more efficient, because the loop control variable is tested one time less than for a pre-test loop. Also, a post-test loop requires only one label and one conditional branch instruction, whereas a pre-test loop requires two labels, a conditional branch, and an unconditional branch.

Since the loop in Listing 5.9 always executes the body exactly 10 times, we know that the body will always execute at least once. Therefore, the loop can be converted to a post-test loop. Listing 5.12 shows the program rewritten as a post-test loop so that it is easier to translate into assembly. Note that, as in the previous example, the initialization of the loop variable has been moved to its own line before the do-while loop, and the loop variable is modified on the last line of the loop body. This post-test version will produce the same output as the pre-test version. This is a straightforward conversion from one type of loop to an equivalent type. Listing 5.13 shows a straightforward translation of the post-test loop structure into ARM assembly.

5.4 Subroutines

A subroutine is a sequence of instructions to perform a specific task, packaged as a single unit. Depending on the particular programming language, a subroutine may be called a procedure, a function, a routine, a method, a subprogram, or some other name. Some languages, such as Pascal, make a distinction between functions and procedures. A function must return a value and must not alter its input arguments or have any other side effects (such as producing output or changing static or global variables). A procedure returns no value, but may alter the value of its arguments or have other side effects.

Other languages, such as C, make no distinction between procedures and functions. In these languages, functions may be described as pure or impure. A function is pure if:

1. the function always evaluates the same result value when given the same argument value(s), and

2. evaluation of the result does not cause any semantically observable side effect or output.

The first condition implies that the result of the function cannot depend on any hidden information or state that may change as program execution proceeds, or between different executions of the program, nor can it depend on any external input from I/O devices. The result value of a pure function does not depend on anything other than the argument values. If the function returns multiple result values, then these two conditions must apply to all returned values. Otherwise the function is impure. Another way to state this is that impure functions have side effects while pure functions have no side effects.

Assembly language does not impose any distinction between procedures and functions, pure or impure. Although every assembly language will provide a way to call subroutines and return from them, it is up to the programmer to decide how to pass arguments to the subroutines and how to pass return values back to the section of code that called the subroutine. Once again, the expert assembly programmer will use structured programming concepts to write efficient, readable, debugable, and maintainable code.

5.4.1 Advantages of Subroutines

Subroutines help programmers to design reliable programs by decomposing a large problem into a set of smaller problems. It is much easier to write and debug a set of small code pieces than it is to work on one large piece of code. Careful use of subroutines will often substantially reduce the cost of developing and maintaining a large program, while increasing its quality and reliability. The advantages of breaking a program into subroutines include:

• enabling reuse of code across multiple programs,

• reducing duplicate code within a program,

• enabling the programming task to be divided between several programmers or teams,

• decomposing a complex programming task into simpler steps that are easier to write, understand, and maintain,

• enabling the programming task to be divided into stages of development, to match various stages of a project, and

• hiding implementation details from users of the subroutine (a programming principle known as information hiding).

5.4.2 Disadvantages of Subroutines

There are two minor disadvantages in using subroutines. First, invoking a subroutine (versus using in-line code) imposes overhead. The arguments to the subroutine must be put into some known location where the subroutine can find them. if the subroutine is a function, then the return value must be put into a known location where the caller can find it. Also, a subroutine typically requires some standard entry and exit code to manage the stack and save and restore the return address.

In most languages, the cost of using subroutines is hidden from the programmer. In assembly, however, the programmer is often painfully aware of the cost, since they have to explicitly write the entry and exit code for each subroutine, and must explicitly write the instructions to pass the data into the subroutine. However, the advantages usually outweigh the costs. Assembly programs can get very large and failure to modularize the code by using subroutines will result in code that cannot be understood or debugged, much less maintained and extended.

5.4.3 Standard C Library Functions

Subroutines may be defined within a program, or a set of subroutines may be packaged together in a library. Libraries of subroutines may be used by multiple programs, and most languages provide some built-in library functions. The C language has a very large set of functions in the C standard library. All of the functions in the C standard library are available to any program that has been linked with the C standard library. Even assembly programs can make use of this library. Linking is done automatically when gcc is used to assemble the program source. All that the programmer needs to know is the name of the function and how to pass arguments to it.

5.4.4 Passing Arguments

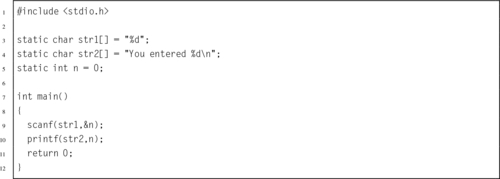

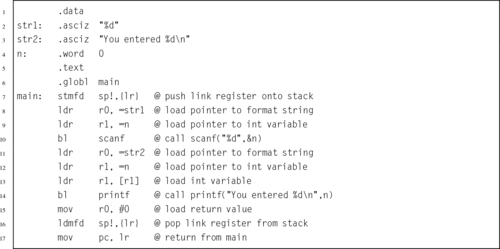

Listing 5.14 shows a very simple C program which reads an integer from standard input using scanf and prints the integer to standard output using printf. An equivalent program written in ARM assembly is shown in Listing 5.15. These examples show how arguments can be passed to subroutines in C and equivalently in assembly language.

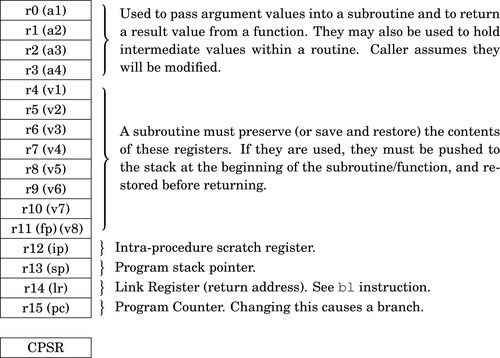

All processor families have their own standard methods, or function calling conventions, which specify how arguments are passed to subroutines and how function values are returned. The function call standard allows programmers to write subroutines and libraries of subroutines that can be called by other programmers. In most cases, the function calling standards are not enforced by hardware, but assembly programmers and compiler writers conform to the standards in order to make their code accessible to other programmers. The basic subroutine calling rules for the ARM processor are simple:

• The first four arguments go in registers r0-r3.

• Any remaining arguments are pushed to the stack.

If the subroutine returns a value, then it is stored in r0 before the function returns to its caller. Calling a subroutine in ARM assembly usually requires several lines of code. The number of lines required depends on how many arguments the subroutine requires and where the data for those arguments are stored. Some variables may already be in the correct register. Others may need to be moved from one register to another. Still others may need to be pushed onto the stack. Careful programming is required to minimize the amount of work that must be done just to move the subroutine arguments into their required locations.

The ARM register set was introduced in Chapter 3. Some registers have special purposes that are dictated by the hardware design. Others have special purposes that are dictated by programming conventions. Programmers follow these conventions so that their subroutines are compatible with each other. These conventions are simply a set of rules for how registers should be used. In ARM assembly, all registers have alternate names which can be used to help remember the rules for using them. Fig. 5.1 shows an expanded view of the ARM registers, including their alternate names and conventional use.

Registers r0-r3 are also known as a1-a4, because they are used for passing arguments to subroutines. Registers r4-r11 are also known as v1-v8, because they are used for holding local variables in a subroutine. As mentioned in Section 3.2, register r11 can also be referred to as fp because it is used by the C compiler to track the stack frame, unless the code is compiled using the --omit-frame- pointer command line option.

The intra-procedure scratch register, r12, is used by the C library when calling dynamically linked functions. If a subroutine does not call any C library functions, then it can use r12 as another register to store local variables. If a C library function is called, it may change the contents of r12. Therefore, if r12 is being used to store a local variable, it should be saved to another register or to the stack before a C library function is called.

5.4.5 Calling Subroutines

The stack pointer (sp), link register (lr), and program counter (pc), along with the argument registers, are all involved in performing subroutine calls. The calling subroutine must place arguments in the argument registers, and possibly on the stack as well. Placing the arguments in their proper locations is known as marshaling the arguments. After marshaling the arguments, the calling subroutine executes the bl instruction, which will modify the program counter and link register. The bl instruction copies the contents of the program counter to the link register, then loads the program counter with the address of the first instruction in the subroutine that is being called. The CPU will then fetch and execute its next instruction from the address in the program counter, which is the first instruction of the subroutine that is being called.

Our first examples of calling a function will involve the printf function from the C standard library. The printf function can be a bit confusing at first, but it is an extremely useful and flexible function for printing formatted output. The printf function examines its first argument to determine how many other arguments have been passed to it. The first argument is a format string, which is a null-terminated ASCII string. The format string may include conversion specifiers, which start with the \% character. For each conversion specifier, printf assumes that an argument has been passed in the correct register or location on the stack. The argument is retrieved, converted according to the specified format, and printed. Other specifiers include \%X to print the matching argument as an integer in hexadecimal, \%c to print the matching argument as an ASCII character, \%s to print a zero-terminated string. The integer specifiers can include an optional width and zero-padding specification. For example \%8X will print an integer in hexadecimal, using 8 characters. Any leading zeros will be printed as spaces. The format string \%08X will print an integer in hexadecimal, using 8 characters. In this case, any leading zeros will be printed as zeros. Similarly, \%15d can be used to print an integer in base 10 using spaces to pad the number up to 15 characters, while \%015d will print an integer in base 10 using zeros to pad up to 15 characters.

Listing 5.16 shows a call to printf in C. The printf function requires one argument, and can accept more than one. In this case, there is only one argument, the format string. Listing 5.17 shows an equivalent call made in ARM assembly language. The single argument is loaded into r0 in conformance with the ARM subroutine calling convention.

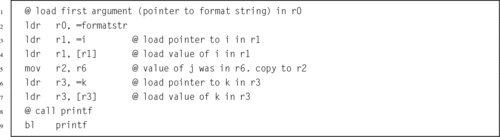

Passing arguments in registers

Listing 5.18 shows a call to printf in C having four arguments. The format string is the first argument. The format string contains three conversion specifiers, and is followed by three more arguments. Arguments are matched to conversion specifiers according to their positions. The type of each argument matches the type indicated in the conversion specifier. The first conversion specifier is applied to the second argument, the second conversion specifier is applied to the third argument, and the third conversion specifier is applied to the fourth argument. The \%d conversion specifiers indicate that the arguments are to be interpreted as integers and printed in base 10.

Listing 5.19 shows an equivalent call made in ARM assembly language. The arguments are loaded into r0-r3 in conformance with the ARM subroutine calling convention. Note that we assume that formatstr has previously been defined using a .asciz or .string assembler directive or equivalent method. As long as there are four or fewer arguments that must be passed, they can all fit in registers r0-r3 (a.k.a a1-a4), but when there are more arguments, things become a little more complicated. Any remaining arguments must be passed on the program stack, using the stack pointer r13. Care must be taken to ensure that the arguments are pushed to the stack in the proper order. Also, after the function call, the arguments must be removed from the stack, so that the stack pointer is restored to its original value.

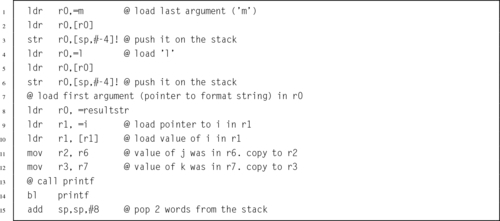

Passing arguments on the stack

Listing 5.20 shows a call to printf in C having more than four arguments. The format string is the first argument. The format string contains five conversion specifiers, which implies that the format string must be followed by five additional arguments. Arguments are matched to conversion specifiers according to their positions. The type of each argument matches the type indicated in the conversion specifier. The first conversion specifier is applied to the second argument, the second conversion specifier is applied to the third argument, the third conversion specifier is applied to the fourth argument, etc. The \%d conversion specifiers indicate that the arguments are to be interpreted as integers and printed in base 10.

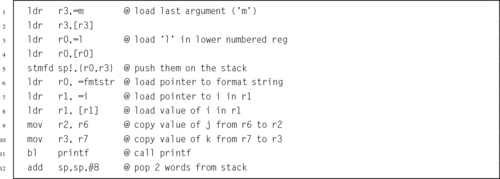

Listing 5.21 shows an equivalent call made in ARM assembly language. Since there are six arguments, the last two must be pushed to the program stack. The arguments are loaded into r0 one at a time and then the register pre-indexed addressing mode is used to subtract four bytes from the stack pointer and then store the argument at the top of the stack. Note that the sixth argument is pushed to the stack first, followed by the fifth argument. The remaining arguments are loaded in r0-r3. Note that we assume that formatstr has previously been defined to be ”The results are: or \ lstinline { .string assembler directive.

Listing 5.22 shows how the fifth and sixth arguments can be pushed to the stack using a single stmfd instruction. The sixth argument is loaded into r3 and the fifth argument is loaded into r0, then the stmfd instruction is used to store them on the stack and adjust the stack pointer. A little care must be taken to ensure that the arguments are stored in the correct order on the stack. Remember that the stmfd instruction will always push the lowest-numbered register to the lowest address, and the stack grows downward. Therefore, r3, the sixth argument, will be pushed onto the stack first, making it grow downward by four bytes. Next, r0 is pushed, making the stack grow downward by four more bytes. As in the previous example, the remaining four arguments are loaded into a1-a4.

After the printf function is called, the fifth and sixth arguments must be popped from the stack. If those values are no longer needed, then there is no need to load them into registers. The quickest way to pop them from the stack is to simply adjust the stack pointer back to its original value. In this case, we pushed two arguments onto the stack, using a total of eight bytes. Therefore, all we need to do is add eight to the stack pointer, thereby restoring its original value.

5.4.6 Writing Subroutines

We have looked at the conventions that are followed for calling functions. Now we will examine these same conventions from the point of view of the function being called. Because of the calling conventions, the programmer writing a function can assume that

• the first four arguments are in r0-r3,

• any additional arguments can be accessed with ldr rd,[sp,# offset ],

• the calling function will remove arguments from the stack, if necessary,

• if the function return type is not void, then they must enusure that the return value is in r0 (and possibly r1, r2, r3), and

• the return address will be in lr.

Also because of the conventions, there are certain registers that can be used freely while others must be preserved or restored so that the calling function can continue operating correctly. Registers which can be used freely are referred to as volatile, and registers which must be preserved or restored before returning are referred to as non-volatile. When writing a subroutine (function),

• registers r0-r3 and r12 are volatile,

• registers r4-r11 and r13 are non-volatile (they can be used, but their contents must be restored to their original value before the function returns),

• register r14 can be used by the function, but its contents must be saved so that the return address can be loaded into r15 when the function returns to its caller,

• if the function calls another function, then it must save register r14 either on the stack or in a non-volatile register before making the call.

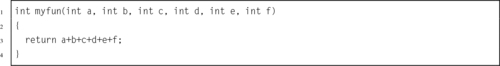

Listing 5.23 shows a small C function that simply returns the sum of its six arguments. The ARM assembly version of that function is shown in Listing 5.24. Note that on line 5, the fifth argument is loaded from the stack, and on line 7, the sixth argument is loaded in a similar way, using an offset from the stack pointer. If the calling function has followed the conventions, then the fifth and sixth arguments will be where they are expected to be in relation to the stack pointer.

5.4.7 Automatic Variables

In block-structured high-level languages, an automatic variable is a variable that is local to a block of code and not declared with static duration. It has a lifetime that lasts only as long as its block is executing. Automatic variables can be stored in one of two ways:

1. the stack is temporarily adjusted to hold the variable, or

2. the variable is held in a register during its entire life.

When writing a subroutine in assembly, it is the responsibility of the programmer to decide what automatic variables are required and where they will be stored. In high-level languages this decision is usually made by the compiler. In some languages, including C, it is possible to request that an automatic variable be held in a register. The compiler will attempt to comply with the request, but it is not guaranteed. Listing 5.25 shows a small function which requests that one of its variables be kept in a register instead of on the stack.

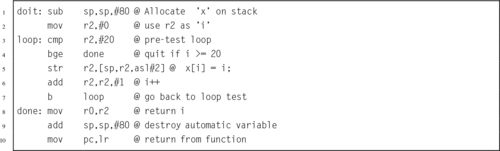

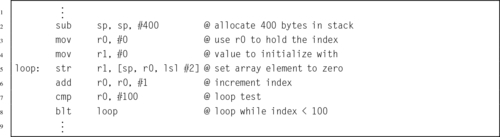

Listing 5.26 shows how the function could be implemented in assembly. Note that the array of integers consumes 80 bytes of storage on the stack, and could not possibly fit into the registers available on the ARM processor. However, the loop control variable can easily be stored in one of the registers for the duration of the function. Also notice that on line 1 the storage for the array is allocated simply by adjusting the stack pointer, and on line 9 the storage is released by restoring the stack pointer to its original contents. It is critical that the stack pointer be restored, no matter how the function returns. Otherwise, the calling function will probably mysteriously fail. For this reason, each function should have exactly one block of instructions for returning. If the function needs to return from some location other than the end, then it should branch to the return block rather than returning directly.

5.4.8 Recursive Functions

A function that calls itself is said to be recursive. Certain problems are easy to implement recursively, but are more difficult to solve iteratively. A problem exhibits recursive behavior when it can be defined by two properties:

1. a simple base case (or cases), and

2. a set of rules that reduce all other cases toward the base case.

For example, we can define person’s ancestors recursively as follows:

1. one’s parents are one’s ancestors (base case),

2. the ancestors of one’s ancestors are also one’s ancestors (recursion step).

Recursion is a very powerful concept in programming. Many functions are naturally recursive, and can be expressed very concisely in a recursive way. Numerous mathematical axioms are based upon recursive rules. For example, the formal definition of the natural numbers by the Peano axioms can be formulated as:

2. each natural number has a successor, which is also a natural number.

Using one base case and one recursive rule, it is possible to generate the set of all natural numbers. Other recursively defined mathematical objects include functions and sets.

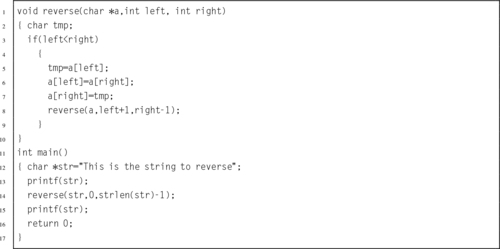

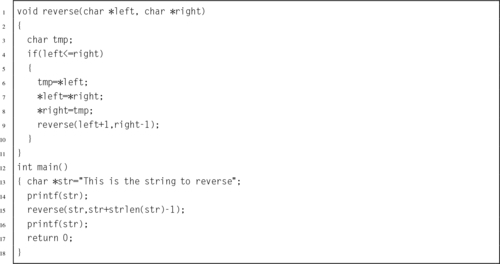

Listing 5.27 shows the C code for a small program which uses recursion to reverse the order of characters in a string. The base case where recursion ends is when there are fewer than two characters remaining to be swapped. The recursive rule is that the reverse of a string can be created by swapping the first and last characters and then reversing the string between them. In short, a string is reversed if:

1. the string has a length of zero or one character, or

2. the first and last characters have been swapped and the remaining characters have been reversed.

In Listing 5.27, line 3 checks for the base case. If the string has not been reversed according to the first rule, then the second rule is applied. Lines 5–7 swap the first and last characters, and line 8 recursively reverses the characters between them.

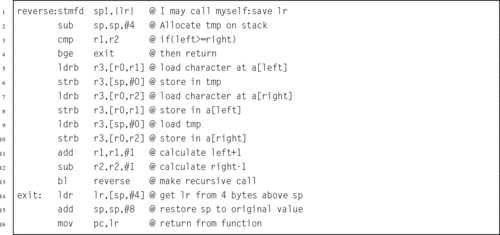

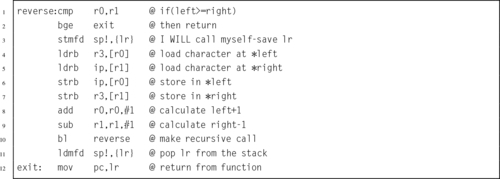

Listing 5.28 shows how the reverse function can be implemented using recursion in ARM assembly. Line 1 saves the link register to the stack and decrements the stack pointer. Next, storage is allocated for an automatic variable. Lines 3 and 4 test for the base case. If the current case is the base case, then the function simply returns (restoring the stack as it goes). Otherwise, the first and last characters are swapped in lines 5 through 10 and a recursive call is made in lines 11 through 13.

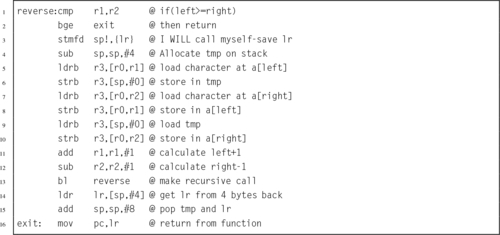

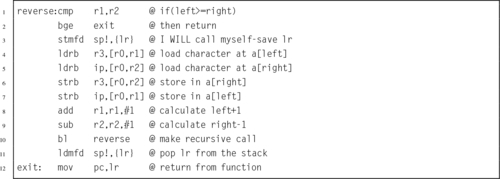

The code in Listing 5.28 can be made a bit more efficient. First, the test for the base case can be performed before anything else is done, as shown in Listing 5.29. Also, the local variable tmp can be stored in a volatile register rather than stored on the stack, because it is only needed for lines 4 through 8. It is not needed after the recursive call, so there is really no need to preserve it on the stack. This means that our function can use half as much stack space and will run much faster. This further refined version is shown in Listing 5.30. This version uses ip (r12) as the tmp variable instead of using the stack.

The previous examples used the concept of an array of characters to access the string that is being reversed. Listing 5.31 shows how this problem can be solved in C using pointers to the first and last characters rather than array indices. This version only has two parameters in the reverse function, and uses pointer dereferencing rather than array indexing to access each character. Other than that difference, it works the same as the original version. Listing 5.32 shows how the reverse function can be implemented efficiently in ARM assembly. This implementation has the same number of instructions as the previous version, but lines 4 through 7 use a different addressing mode. On the ARM processor, the pointer method and the array index method are equally efficient. However, many processors do not have the rich set of addressing modes available on the ARM. On those processors, the pointer method may be significantly more efficient.

5.5 Aggregate Data Types

An aggregate data item can be referenced as a single entity, and yet consists of more than one piece of data. Aggregate data types are used to keep related data together, so that the programmer’s job becomes easier. Some examples of aggregate data are arrays, structures or records, and objects, In most programming languages, aggregate data types can be defined to create higher-level structures. Most high-level languages allow aggregates to be composed of basic types as well as other aggregates. Proper use of structured data helps to make programs less complicated and easier to understand and maintain.

In high-level languages, there are several benefits to using aggregates. Aggregates make the relationships between data clear, and allow the programmer to perform operations on blocks of data. Aggregates also make passing parameters to functions simpler and easier to read.

5.5.1 Arrays

The most common aggregate data type is an array. An array contains zero or more values of the same data type, such as characters, integers, floating point numbers, or fixed point numbers. An array may also contain values of another aggregate data type. Every element in an array must have the same type. Each data item in an array can be accessed by its array index.

Listing 5.33 shows how an array can be allocated and initialized in C. Listing 5.34 shows the equivalent code in ARM assembly. Note that in this case, the scaled register offset addressing mode was used to access each element in the array. This mode is often convenient when the size of each element in the array is an integer power of 2. If that is not the case, then it may be necessary to use a different addressing mode. An example of this will be given in Section 5.5.3.

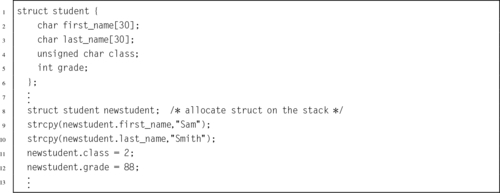

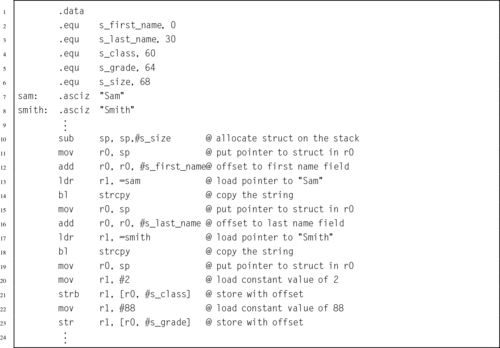

5.5.2 Structured Data

The second common aggregate data type is implemented as the struct in C or the record in Pascal. It is commonly referred to as a structured data type or a record. This data type can contain multiple fields. The individual fields in the structured data may also be referred to as structured data elements, or simply elements. In most high-level languages, each element of a structured data type may be one of the base types, an array type, or another structured data type. Listing 5.35 shows how a struct can be declared, allocated, and initialized in C. Listing 5.36 shows the equivalent code in ARM assembly.

Care must be taken using assembly to access data structures that were declared in higher level languages such as C and C++. The compiler will typically pad a data structure to ensure that the data fields are aligned for efficiency. On most systems, it is more efficient for the processor to access word-sized data if the data is aligned to a word boundary. Some processors simply cannot load or store a word from an address that is not on a word boundary, and attempting to do so will result in an exception. The assembly programmer must somehow determine the relative address of each field within the higher-level language structure. One way that this can be accomplished in C is by writing a small function which prints out the offsets to each field in the C structure. The offsets can then be used to access the fields of the structure from assembly language. Another method for finding the offsets is to run the program under a debugger and examine the data structure.

5.5.3 Arrays of Structured Data

It is often useful to create arrays of structured data. For example, a color image may be represented as a two-dimensional array of pixels, where each pixel consists of three integers which specify the amount of red, green, and blue that are present in the pixel. Typically, each of the three values is represented using an unsigned eight bit integer. Image processing software often adds a fourth value, α, specifying the transparency of each pixel.

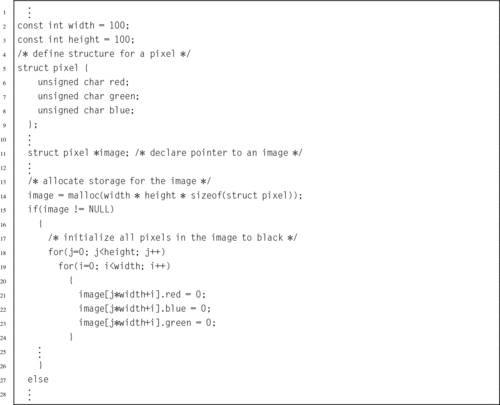

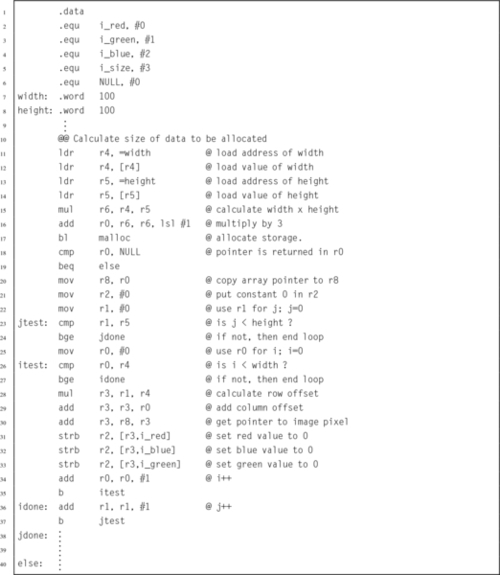

Listing 5.37 shows how an array of pixels can be allocated and initialized in C. The listing uses the malloc() function from the C standard library to allocate storage for the pixels from the heap (see Section 1.4). Note that the code uses the sizeof () function to determine how many bytes of memory are consumed by a single pixel, then multiplies that by the width and height of the image. Listing 5.38 shows the equivalent code in ARM assembly.

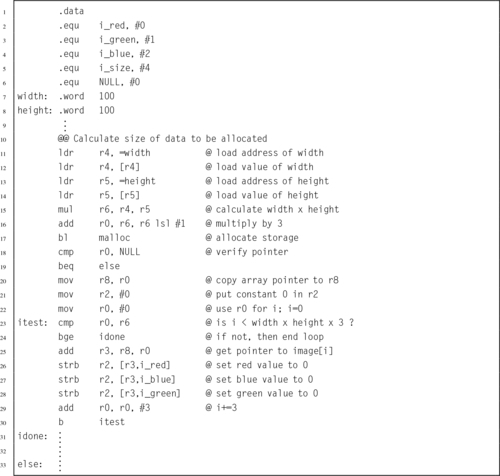

Note that the code in Listing 5.38 is far from optimal. It can be greatly improved by combining the two loops into one loop. This will remove the need for the multiply on line 28 and the addition on line 29, and will simplify the code structure. An additional improvement would be to increment the single loop counter by three on each loop iteration, making it very easy to calculate the pointer for each pixel. Listing 5.39 shows the ARM assembly implementation with these optimizations.

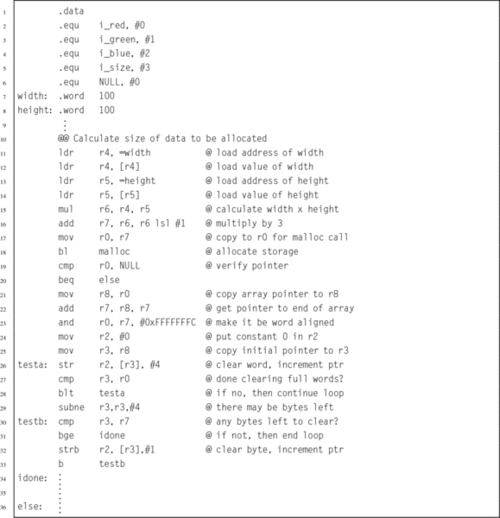

Although the implementation shown in Listing 5.39 is more efficient than the previous version, there are several more improvements that can be made. If we consider that the goal of the code is to allocate some number of bytes and initialize them all to zero, then the code can be written more efficiently. Rather than using three separate store instructions to set 3 bytes to zero on each iteration of the loop, why not use a single store instruction to set four bytes to zero on each iteration? The only problem with this approach is that we must consider the possibility that the array may end in the middle of a word. However, this can be dealt with by using two consecutive loops. The first loop sets one word of the array to zero on each iteration, and the second loop finishes off any remaining bytes. Listing 5.40 shows the results of these additional improvements. This third implementation will run much faster than the previous implementations.

5.6 Chapter Summary

Spaghetti code is the bane of assembly programming, but it can easily be avoided. Although assembly language does not enforce structured programming, it does provide the low-level mechanisms required to write structured programs. The assembly programmer must be aware of, and assiduously practice, proper structured programming techniques. The burden of writing properly structured code blocks, with selection structures and iteration structures, lies with the programmer, and failure to apply structured programming techniques will result in code that is difficult to understand, debug, and maintain.

Subroutines provide a way to split programs into smaller parts, each of which can be written and debugged individually. This allows large projects to be divided among team members. In assembly language, defining and using subroutines is not as easy as in higher level languages. However, the benefits usually outweigh the costs. The C library provides a large number of functions. These can be accessed by an assembly program as long as it is linked with the C standard library.

Assembly provides the mechanisms to access aggregate data types. Arrays can be accessed using various addressing modes on the ARM processor. The pre-indexing and post-indexing modes allow array elements to be accessed using pointers, with the pointers being incremented after each element access. Fields in structured data records can be accessed using immediate offset addressing mode. The rich set of addressing modes available on the ARM processor allows the programmer to use aggregate data types more efficiently than on most processors.

Exercises

5.1 What does it mean for a register to be volatile? Which ARM registers are considered volatile according to the ARM function calling convention?

5.2 Fully explain the differences between static variables and automatic variables.

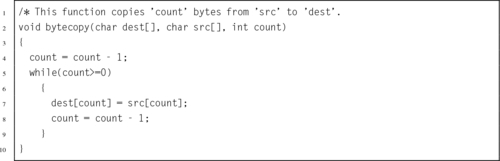

5.3 In ARM assembly language, write a function that is equivalent to the following C function.

5.4 What are the two places where an automatic variable can be stored?

5.5 You are writing a function and you decided to use registers r4 and r5 within the function. Your function will not call any other functions; it is self-contained. Modify the following skeleton structure to ensure that r4 and r5 can be used within the function and are restored to comply with the ARM standards, but without unnecessary memory accesses.

5.6 Convert the following C program to ARM assembly, using a post-test loop:

5.7 Write a complete ARM function to shift a 64-bit value left by any given amount between 0 and 63 bits. The function should expect its arguments to be in registers r0, r1, and r2. The lower 32 bits of the value are passed in r0, the upper 32 bits of the value are passed in r1, and the shift amount is passed in r2.

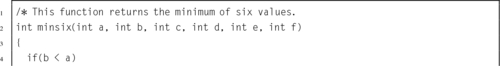

5.8 Write a complete subroutine in ARM assembly that is equivalent to the following C subroutine.

5.9 Write a complete function in ARM assembly that is equivalent to the following C function.

5.10 Write an ARM assembly function to calculate the average of an array of integers, given a pointer to the array and the number of items in the array. Your assembly function must implement the following C function prototype:

Assume that the processor does not support the div instruction, but there is a function available to divide two integers. You do not have to write this function, but you may need to call it. Its C prototype is:

5.11 Write a complete function in ARM assembly that is equivalent to the following C function. Note that a and b must be allocated on the stack, and their addresses must be passed to scanf so that it can place their values into memory.

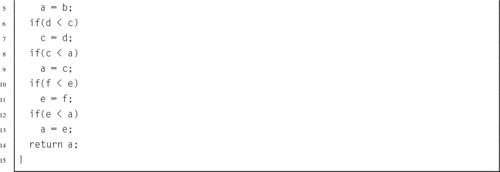

5.12 The factorial function can be defined as:

The following C program repeatedly reads x from the user and calculates x! It quits when it reads end-of-file or when the user enters a negative number or something that is not an integer.

Write this program in ARM assembly.

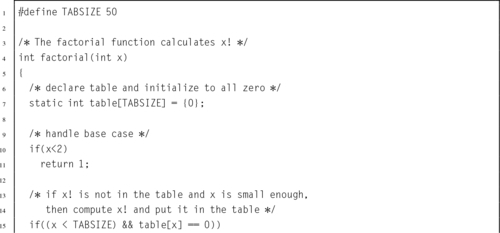

5.13 For large x, the factorial function is slow. However, a lookup table can be added to the function to improve average performance. This technique is commonly known as memoization or tabling, but is sometimes called dynamic programming. The following C implementation of the factorial function uses memoization. Modify your ARM assembly program from the previous problem to include memoization.