At several points in this chapter, we have talked about security

issues and limitations of forwarding. So far, we’ve seen very little

control over who can connect to a forwarded port. The OpenSSH default is

to allow connections only from the local host, which is reasonably

secure for a single-user machine. But if you need to allow connections

from elsewhere, you have a problem, since it’s all or nothing: to allow

connections from elsewhere (using -g or GatewayPorts yes), you must allow them from

anywhere. And with Tectia it’s worse: forwarded

ports always accept connections from anywhere. X

forwarding is in a slightly better position, since the X protocol has

its own authentication, but you might still prefer to restrict access,

preventing intruders from exploiting an unknown security flaw or

performing a denial-of-service attack. SSH on the Unix platform provides

an optional feature for access control based on the client address,

called “TCP-wrappers.”

The term “TCP-wrappers” refers to software written by Wietse Venema. If it isn’t already installed in your Unix distribution, you can get it at:

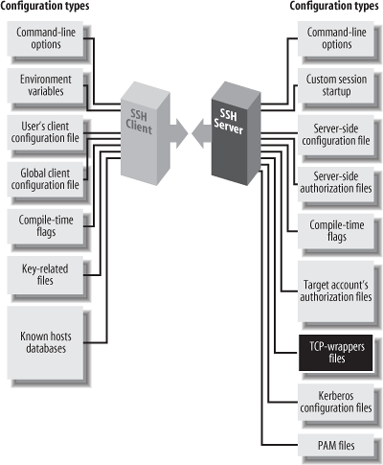

TCP-wrappers are a global access control mechanism that integrates with other TCP-based servers, such as sshd or telnetd. Access control is based on the source address of incoming TCP connections. That is, a TCP-wrapper permits or denies connections based on their origin, as specified in the configuration files /etc/hosts.allow and /etc/hosts.deny. Figure 9-12 shows where TCP-wrappers fit into the scheme of SSH configuration.

There are two ways to use TCP-wrappers. The most common method, wrapping, is applied to TCP servers that are normally invoked by inetd. You “wrap” the server by editing /etc/inetd.conf and modifying the server’s configuration line. Instead of invoking the server directly, you invoke the TCP-wrapper daemon, tcpd, which in turn invokes the original server. Then, you edit the TCP-wrapper configuration files to specify your desired access control. tcpd makes authorization decisions based on the their contents.

The inetd technique applies access control

without having to modify the TCP server program. This is nice. However,

sshd is usually not invoked by

inetd [5.3.3.2], so the second

method, source code modification, must be applied.

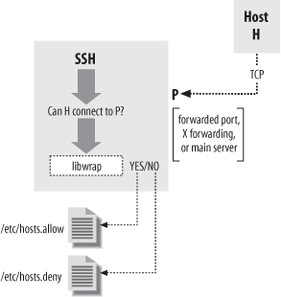

To participate in TCP-wrapper control, the SSH server must be compiled

with the flag --with-tcp-wrappers [4.2.4.5] or

--with-libwrap [4.3.5.3] to enable internal

support for TCP-wrappers. sshd then invokes

TCP-wrapper library functions to do explicit access-control checks

according to the rules in /etc/hosts.allow and /etc/hosts.deny. So, in a sense, the term

“wrapper” is misleading since sshd is modified, not

wrapped, to support TCP-wrappers. Figure 9-13 illustrates the

process.

The access control language for TCP-wrappers has quite a few options and may vary depending on whose package you use and what version it is. We won’t cover the language completely in this book. Consult your local documentation for a complete

understanding: the manpages on tcpd, hosts_access, and hosts_options. We just indicate some simple, common configurations.

The TCP-wrapper configuration is kept in the files /etc/hosts.allow and /etc/hosts.deny. These files contain patterns of the form:

service_1 [service_2 service_3 ...] : client_1 [client_2 client_3 ...]

Each pattern matches some (server,client) pairs, and hence may match a particular client/server TCP connection. Specifically, a connection between client C and server S matches this rule if some service servicei matches S, and some clientj matches C. (We explain the format and matching rules for these subpatterns shortly.) The hosts.allow file is searched first, followed by hosts.deny. If a matching pattern is found in hosts.allow, the connection is allowed. If none is found there, but one matches in hosts.deny, the connection is dropped. Finally, if no patterns match in either file, the connection is allowed. Nonexistence of either file is treated as if the file existed and contained no matching patterns. Note that the default, then, is to allow everything.

There is also an extended syntax, documented on the hosts_options manpage. It may or may not be available, depending on how your TCP-wrapper library was built. It has many more options, but in particular, it allows tagging an individual rule as denying or rejecting a matching connection, for example:

sshd : bad.host.com : DENY

Using this syntax, you can put all your rules into the hosts.allow file, rather than having to use

both files. To reject anything not explicitly allowed, just put

ALL : ALL : DENY at the end of the

file.

In a pattern, each service is a name indicating a server to which this pattern applies. SSH recognizes the following service names:

- sshd

The main SSH server. This can be sshd, sshd1, sshd2, or whatever name you invoke the daemon under (its

argv[0]value, in C-programmer-speak).- sshdfwd-x11

The X forwarding port.

- sshdfwd-N

Forwarded TCP port n (e.g., forwarded port 2001 is

service sshdfwd-2001).

Tip

The X and port -orwarding control features are available only in Tectia; OpenSSH uses libwrap only to control access to the main server.

Each client is a pattern that matches a connecting client. It can be:

An IP address in dotted-quad notation (e.g., 192.168.10.1).

A hostname (DNS, or whatever naming services the host is using).

An IP network as

network-number/mask(e.g., 192.168.10.0/255.255.255.0; note that the “/n-mask-bits" syntax, 192.168.10.0/24, isn’t recognized).“ALL”, matching any client source address.

Example 9-1 shows a sample /etc/hosts.allow configuration. This setup allows connections to any service from the local host’s loopback address, and from all addresses 192.168.10.x. This host is running publicly available servers for POP and IMAP, so we allow connections to these from anywhere, but SSH clients are restricted to sources in another particular range of networks.

Example 9-1. Sample /etc/hosts.allow file

# # /etc/hosts.allow # # network access control for programs invoked by tcpd (see inetd.conf) or # using libwrap. See the manpages hosts_access(5) and hosts_options(5). # allow all connections from my network or localhost (loopback address) # ALL : 192.168.10.0/255.255.255.0 localhost # allow connections to these services from anywhere # ipop3d imapd : ALL # allow SSH connections from these eight class C networks # 192.168.20.0, 192.168.21.0, ..., 192.168.27.0 # sshd : 192.168.20.0/255.255.248.0 # allow connections to forwarded port 1234 from host blynken # Tectia only sshdfwd-1234 : blynken.sleepy.net # restrict X forwarding access to localhost # Tectia only sshdfwd-x11 : localhost # deny everything else # ALL : ALL : DENY

We allow connections to the forwarded port 1234 from a particular host, blynken.sleepy.net. Note that this host doesn’t have to be on any of the networks listed so far but can be anywhere at all. The rules so far say what is allowed, but don’t by themselves forbid any connections. So, for example, the forwarding established by the command ssh -L1234:localhost:21 remote is accessible only to the local host, since Tectia defaults to binding only the loopback address in any case. But ssh -g -L1234:localhost:21 remote is accessible to blynken.sleepy.net as well. The important difference is that with this use of TCP-wrappers, sshd rejects connections to the forwarded port, 1234, from any other address.

The sshdfwd-x11 line

restricts X-forwarding connections to the local host. This means that

if ssh connects to this host

with X forwarding, only local X clients can use the forwarded X

connection. X authentication does this already, but this configuration

provides an extra bit of protection.

The final line denies any connection that doesn’t match the earlier lines, making this a default-to-closed configuration. If you wanted instead to deny some particular connections but allow all others, you would use something like this:

ALL : evil.mordor.net : DENY

telnetd : completely.horked.edu : DENY

ALL : ALL : ALLOWThe final line is technically not required, but it’s a good idea to make your intentions explicit. If you don’t have the host_options syntax available, you instead have an empty hosts.allow file, and the following lines in hosts.deny:

ALL : evil.mordor.net

telnetd : completely.horked.eduHere are a few things to remember when using TCP-wrappers:

You can’t distinguish between ports forwarded by SSH-1 and SSH-2: the “sshdfwd” rules refer to both simultaneously. You can work around this limitation by linking each against a different libwrap.a, compiled with different filenames for the allow and deny files, or by patching the ssh and sshd executables directly, but then you have to keep track of these changes and extra files.

The big drawback to TCP-wrappers is that it affects all users simultaneously. An individual user can’t specify custom access rules for himself; there’s just the single set of global configuration files for the machine. This limits its usefulness on multiuser machines.

If you compile SSH with the

--with-libwrapoption, it is automatically and always turned on; there’s no configuration or command-line option to disable the TCP-wrappers check. Remember that SSH does this check not only for forwarded ports and X connections, but also for connections to the main SSH server! As soon as you install a version of sshd with TCP-wrappers, you must ensure that the TCP-wrappers configuration allows connections to the server—for instance, with the rulesshd : ALLin /etc/hosts.allow.Using hostnames instead of addresses in the TCP-wrappers rule set involves the usual security trade-off. Names are more convenient, and their use avoids breakage in the future if a host address changes. On the other hand, an attacker can potentially subvert the naming service and circumvent the access control. If the host machine is configured to use only its /etc/hosts file for name lookup, this may be acceptable even in a highly secure environment.

The TCP-wrappers package includes a program called tcpdchk. This program examines the wrapper control files and reports inconsistencies that might signal problems. Many sites run this periodically as a safety check. Unfortunately, tcpdchk is written only with explicit wrapping via inetd.conf in mind. It doesn’t have any way of knowing about programs that refer to the control files via the libwrap routines, as does sshd. When tcpdchk reads control files with SSH rules, it finds uses of the service names “sshd1,” “sshdfwd-

n,” etc., but no corresponding wrapped services in inetd.conf, and it generates a warning. Unfortunately, we know of no workaround.