The clients ssh and scp are quite configurable, with many settings that can be changed to suit your whim. If you want to modify the behavior of these clients, three general techniques are at your disposal:

We now present a general overview of these three methods.

Command-line options let you change a client’s behavior just once, at invocation. For example, if you’re using ssh over a slow modem connection, you can tell it to compress the data with the -C command-line option:

$ ssh -C server.example.com

ssh, scp, and most of their support programs, when invoked with the --help option, will print a helpful summary describing all their command-line options.[102] For example:

$ ssh --help

$ scp --help

$ ssh-keygen -helpIf you don’t want to retype command-line options continually, configuration files let you change a client’s behavior now and in the future, until you change the configuration file again. For example, you can enable compression for all clients you invoke by inserting this line into a client configuration file:

Compression yes

In a client configuration file, client settings are changed by

specifying keywords and values. In the example, the keyword is

Compression and the value is

yes. You may also separate the

keyword and value with an equals sign, with optional

whitespace:

Compression = yes

You may configure clients to behave differently for each remote host you visit. This can be done on the fly with command-line options, but for anything reasonably complex, you’ll end up typing long, inconvenient command lines like:

$ ssh -a -p 220 -c blowfish -l sally -i myself server.example.com

Alternatively, you can set these options within a configuration file. The following entry duplicates the function of the preceding command-line options, collecting them under the name “myserver”:

# OpenSSH (Tectia's syntax differs slightly as we'll see later)

Host myserver

ForwardAgent no

Port 220

Cipher blowfish

User sally

IdentityFile myself

HostName server.example.comNow, to run a client with these options enabled, simply type:

$ ssh myserver

Configuration files take some time to set up, but in the long run they are significant timesavers. We now discuss the general structure of these files (host specifications followed by keyword/value pairs), then dive into specific keywords.

Configuration files and command-line options have two important relationships:

Every configuration keyword can appear on the command line with the -o option.

Alternative configuration files are referenced with the -F option.

For any configuration line of the form:

Keyword Valueyou may type:

$ ssh -o "Keyword Value" ...For example, the configuration file lines:

User sally

Port 220can be specified on the command line as:

$ ssh -o "User sally" -o "Port 220" server.example.com

As in the configuration file, an equals sign (with optional whitespace) is permitted between the keyword and the value:

$ ssh -o User=sally -o Port=220 server.example.com

If you use an equals sign, and the value for the keyword contains special characters that would be misinterpreted by the shell, surround the value with quotes.

The -o option may appear multiple times on the same command line, for both ssh and scp:

# OpenSSH

$ scp -o "User sally" -o "Port 220" myfile server.example.com:The other relationship between command-line options and configuration keywords is found in the -F option, which instructs a client to use a different configuration file instead of the default. For example:

$ ssh -F /usr/local/ssh/other_config

Warning

OpenSSH and Tectia treat the -F option differently. OpenSSH will ignore the default configuration file (/etc/ssh/ssh_config) and use only the one you provide. Tectia, on the other hand, will still process its default configuration file (/etc/ssh2/ssh2_config), and then your provided file can override those settings.

Client configuration files come in two flavors. A single, global client configuration file, usually created by a system administrator, governs client behavior for an entire computer. The file is traditionally /etc/ssh/ssh_config (OpenSSH) or /etc/ssh2/ssh2_config (Tectia). (Don’t confuse these with the server configuration files in the same directories.) Each user may also create a local client configuration file within his or her account, usually ~/.ssh/config (OpenSSH) or ~/.ssh2/ssh2_config (Tectia). This file controls the behavior of clients run in the user’s login session.[103]

Values in a user’s local file take precedence over those in the global file. For instance, if the global file turns on data compression, and your local file turns it off, the local file wins for clients run in your account. We cover precedence in more detail later. [7.2]

Client configuration files are divided into sections. Each section contains settings for one remote host or for a set of related remote hosts, such as all hosts in a given domain.

The beginning of a section is marked differently in different

SSH implementations. For OpenSSH, the keyword Host begins a new section, followed by a

string called a host specification. The string

may be a hostname:

Host server.example.com

an IP address:

Host 123.61.4.10

a nickname for a host: [7.1.2.5]

Host my-nickname

or a wildcard pattern representing a set of hosts, where ? matches any single character and * any sequence of characters (just like filename wildcards in your favorite Unix shell):

Host *.example.com

Host 128.220.19.*Some further examples of wildcards:

Host *.edu Any hostname in the edu domain Host a* Any hostname whose name begins with "a" Host *1* Any hostname (or IP address!) with 1 in it Host * Any hostname or IP address

Tectia, in contrast, does not use a Host keyword. A new section is marked by a

host specification string followed by a colon. This string may

likewise be a computer name:

server.example.com:

an IP address:

123.61.4.10:

a nickname:

my-nickname:

or a wildcard pattern:

*.example.com:

128.220.19.*:You then follow the host-specification line with one or more settings, i.e., configuration keywords and values, as in the example we saw earlier. The following table contrasts OpenSSH and Tectia configuration files:

OpenSSH | Tectia |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

The settings apply only to the hosts named in the host specification. The section ends at the next host specification or the end of the file, whichever comes first.

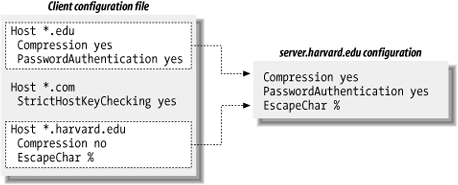

Because wildcards are permitted in host specifications, a single hostname might match two or more sections in the configuration file. For example, if one section begins:[104]

Host *.edu

and another begins:

Host *.harvard.edu

and you connect to server.harvard.edu, which section applies? Believe it or not, they both do. Every matching section applies, and if a keyword is set more than once with different values, only one value applies. For OpenSSH, the earliest value takes precedence, whereas for Tectia the latest value wins.

Suppose your client configuration file contains two sections to control data compression, password authentication, and the ssh escape character:

Host *.edux

Compression yes

PasswordAuthentication yes

Host *.harvard.edu

Compression no

EscapeChar %and you connect to server.harvard.edu:

$ ssh server.harvard.edu

Notice that the string server.harvard.edu matches both Host patterns, *.edu and *.harvard.edu. As we’ve said, the keywords

in both sections apply to your connection. Therefore, the preceding

ssh command sets values for the keywords

Compression, PasswordAuthentication, and EscapeChar.

But notice, in the example, that the two sections set

different values for Compression.

What happens? The rule is that the first value prevails -- in this

case, yes. So, in the previous

example, the values used for server.harvard.edu are:

Compression yes The first of the Compression lines PasswordAuthentication yes Unique to first section EscapeChar % Unique to second section

and as shown in Figure

7-2. Compression no is

ignored because it is the second Compression line encountered. Likewise, if

10 different Host lines match

server.harvard.edu, all 10 of those sections

apply, and if a particular keyword is set multiple times, only the

first value is used.

While this feature might seem confusing, it has useful properties. Suppose you want some settings applied to all remote hosts. Simply create a section beginning with:

Host *

and place the common settings within it. This section should be either the first or the last in the file. If first, its settings take precedence over any others. This can be used to guard against your own errors. For example, if you want to make sure you never, ever, accidentally use the old SSH-1 protocol, at the beginning of your configuration file put:

# First section of file

Host *

Protocol 2Alternatively, if you place Host

* as the last section in the configuration file, its

settings are used only if no other section overrides them. This is

useful for changing SSH’s default behavior, while still permitting

overrides. For example, by default, data compression is disabled.

You can make it enabled by default by ending your configuration file

with:

# Last section of file

Host *

Compression yesVoilá, you have changed the default behavior of

ssh and scp for your

account! Any other section, earlier in the configuration file, can

override this default simply by setting Compression to no.

Tip

The precedence rule is different for keywords that can apply

multiple times in a section. For example, you can legitimately

have more than one IdentityFile

keyword in a section of ~/.ssh/config (OpenSSH), meaning to try

all the listed keys in turn. [7.4.2] Likewise, if more

than one section applies to a host, and they each contain IdentityFile lines, then the union of

all the named keys will be tried for authentication. In other

words, IdentityFile values

accumulate rather than override each

other.

Suppose your client configuration file contains a section for the remote host myserver.example.com :

Host myserver.example.com

...One day, while logged onto ourclient.example.com, you decide to establish an SSH connection to myserver.example.com. Since both computers are in the same domain, example.com, you can omit the domain name on the command line and simply type:

$ ssh myserver

This does establish the SSH connection, but you run into an unexpected nuance of configuration files. ssh compares the command-line string “myserver” to the Host string “myserver.example.com”, determines that they don’t match, and doesn’t apply the section of the configuration file. Yes, the software requires an exact textual match between the hostnames on the command line and in the configuration file.

You can get around this limitation by declaring myserver to be a nickname for

myserver.example.com. In OpenSSH, this is done

with the Host and HostName keywords. Simply use Host with the nickname and HostName with the fully qualified

hostname:

# OpenSSH

Host myserver

HostName myserver.example.com

...ssh will now recognize that this section applies to your command ssh myserver. You may define any nickname you like for a given computer, even if it isn’t related to the original hostname:

# OpenSSH

Host simple

HostName myserver.example.com

...Then you can use the nickname on the command line:

$ ssh simple

For Tectia, the syntax is different but the effect is the

same. Use the nickname in the host specification, and provide the

full name to the Host

keyword:

# Tectia

simple:

Host myserver.example.com

...Then type:

$ ssh simple

Nicknames are convenient for testing new client settings. Suppose you have an OpenSSH configuration for server.example.com:

Host server.example.com

...and you want to experiment with different settings. You could just modify the settings in place, but if they don’t work, you’d have to waste time changing them back. The following steps demonstrate a more convenient way:

Within the configuration file, make a copy of the section you want to change:

# Original Host server.example.com ... # Copy for testing Host server.example.com ...In the copy, change “Host” to “HostName”:

# Original Host server.example.com ... # Copy for testing HostName server.example.com ...Add a new

Hostline at the beginning of the copy, using a phony name; for example, “Host my-test”:# Original Host server.example.com ... # Copy for testing Host my-test HostName server.example.com ...Setup is done. In the copy (

my-test), make all the changes you want and connect using ssh my-test. You can conveniently compare the old and new behavior by running ssh server.example.com versus ssh my-test. If you decide against the changes, simply delete themy-testsection. If you like the changes, copy them to the original section (or delete the original and keep the copy).

You can do the same with Tectia:

# Original

server.example.com:

...

# Copy for testing

my-test:

Host server.example.com

...You probably noticed in the previous examples that we

use the # symbol to represent

comments:

# This is a comment

In fact, any line beginning with # in the configuration file is treated as a comment and ignored. Likewise, blank lines (empty or containing only whitespace) are also ignored.

You might also have noticed that the lines following a host specification are indented:

# OpenSSH

Host server.example.com

Keyword1 value1

Keyword2 value2

# Tectia

server.example.com:

Keyword1 value1

Keyword2 value2Indenting is considered good style because it visually indicates the beginning of a new section. It isn’t required, but we recommend it.

SSH clients set a number of environment variables, and a few miscellaneous features are controlled by variables you can set. We’ll point out these variables as we encounter them from time to time. Environment variables may be set in your current shell by the standard methods:

# C shell family (csh, tcsh)

$ setenv MY_VARIABLE 1

# Bourne shell family (sh, ksh, bash)

$ MY_VARIABLE=1

$ export MY_VARIABLEAlternatively, environment variables and values may be specified in a file. System administrators can set environment variables for all users in /etc/environment, and users can set them in ~/.ssh/environment (OpenSSH) and ~/.ssh2/environment (Tectia). These files contain lines of the format:

NAME=VALUE

where NAME is the name of an

environment variable, and VALUE is its

value. The value is taken literally, read from the equals sign to the

end of the line. Don’t enclose the value in quotes, even if it

contains whitespace, unless you want the quotes to be part of the

value.

[102] Tectia recognizes -h as an abbreviation of --help.

[103] The system administrator may change the locations of

client configuration files via the compile-time flag

--with-etcdir [4.3.5.1] or the

serverwide keyword UserConfigDirectory. [5.3.1.5] If the files

aren’t in their default locations on your computer, contact your

system administrator.

[104] We use only the OpenSSH file syntax here to keep things tidy, but the explanation is true of Tectia as well.