A good place to start with testing web servers is at the beginning of the HTTP request, by enumerating the HTTP methods. The HTTP method is sent by the client and indicates to the web server the type of action that the client is expecting.

As specified in RFC 7231, all web servers must support GET and HEAD methods, and all other methods are optional. As there are a lot of common methods beyond the initial GET and HEAD methods, this makes it a good place to focus testing on, as each server will be written to handle requests and send responses in a different way.

An interesting HTTP method to look out for is TRACE, as its availability leads to

Cross Site Tracing (XST). TRACE is a loop-back test and basically echoes the request it receives back to the user. This means it can be used for Cross-site scripting attacks (called in this case Cross Site Tracing). To do this, the attacker gets a victim to send a TRACE request, with a JavaScript payload in the body, which would then get executed locally when returned. Modern browsers now have defenses built-in to protect the user from these attacks by blocking TRACE requests made through JavaScript, so this technique now only works against old browsers or when leveraging other technologies such as Java or Flash.

In this recipe, we are going to connect to the target web server and attempt to enumerate the various HTTP methods available. We shall also be looking for the presence of the TRACE method and highlighting it, if available:

import requests

verbs = ['GET', 'POST', 'PUT', 'DELETE', 'OPTIONS', 'TRACE', 'TEST']

for verb in verbs:

req = requests.request(verb, 'http://packtpub.com')

print verb, req.status_code, req.reason

if verb == 'TRACE' and 'TRACE / HTTP/1.1' in req.text:

print 'Possible Cross Site Tracing vulnerability found'The first line imports the requests library; this will be used a lot in this section:

import requests

The next line creates an array of the HTTP methods we are going to send. Notice the standard ones—GET, POST, PUT, HEAD, DELETE, and OPTIONS—followed by a non-standard TEST method. This has been added to check how the server handles input that it's not expecting. Some web frameworks treat a non-standard verb as a GET request and respond accordingly. This can be a good way to bypass firewalls, as they may have a strict list of methods to match against and not process requests from unexpected methods:

verbs = ['GET', 'POST', 'PUT', 'HEAD', 'DELETE', 'OPTIONS', 'TRACE', 'CONNECT', 'TEST']

Next is the main loop of the script. This part sends the HTTP packet; in this case, to the target http://packtpub.com web server. It prints out the method and the response status code and reason:

for verb in verbs:

req = requests.request(verb, 'http://packtpub.com')

print verb, req.status_code, req.reasonFinally, there is a section of code to specifically test for XST:

if verb == 'TRACE' and 'TRACE / HTTP/1.1' in req.text:

print 'Possible Cross Site Tracing vulnerability found'This code checks the server response when sending a TRACE call, checking to see if the response contains the request text.

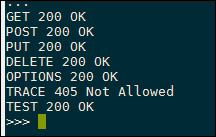

Running the script gives the following output:

Here, we can see that the web server is correctly handling the first five requests, returning a 200 OK response for all these methods. The TRACE response returns 405 Not Allowed, showing that this has been explicitly denied by the web server. One interesting thing with the target server here is that it returns a 200 OK response for the TEST method. This means that the server is processing the TEST request as a different method; for example, it's treating it as a GET request. As earlier mentioned, this makes a good way to bypass some firewalls, as they may not process the unexpected TEST method.

In this recipe, we've shown how to test a target web server for the XST vulnerability and test how it handles various HTTP methods. This script could be extended further by expanding the example HTTP method array to include various other valid and invalid data values; perhaps you could try sending Unicode data to test how the web server handles unexpected character sets or send a very long HTTP method and to test for buffer overflows in custom web servers. A good resource for this data is to check back to the fuzzing scripts in Chapter 3, Vulnerability Identification, for example, using payloads from Mozilla's FuzzDB.