The only difficult thing about performing time-based SQL Injections is that plague of gamers everywhere, lag. A human can easily sit down and account for lag mentally, taking a string of returned values, and sensibly going over the output and working out that cgris is chris. For a machine, this is much harder; therefore, we should attempt to reduce delay.

We will be creating a script that makes multiple requests to a server, records the response time, and returns an average time. This can then be used to calculate fluctuations in responses in time-based attacks known as jitter.

Identify the URLs you wish to attack and provide to the script through a sys.argv variable:

import requests import sys url = sys.argv[1] values = [] for i in xrange(100): r = requests.get(url) values.append(int(r.elapsed.total_seconds())) average = sum(values) / float(len(values)) print “Average response time for “+url+” is “+str(average)

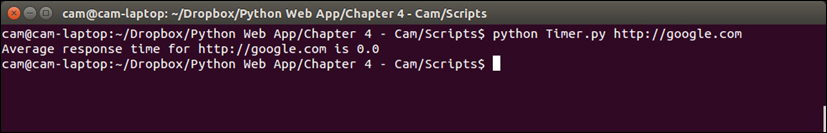

The following screenshot is an example of the output produced when using this script:

We import the libraries we require for this script, as with every other script we've done in this book so far. We set the counter I to zero and create an empty list for the times we are about to generate:

while i < 100: r = requests.get(url) values.append(int(r.elapsed.total_seconds())) i = i + 1

Using the counter I, we run 100 requests to the target URL and append the response time of the request to list we created earlier. R.elapsed is a timedelta object, not an integer, and therefore must be called with .total_seconds() in order to get a usable number for our later average. We then add one to the counter to account for this loop and so that the script ends appropriately:

average = sum(values) / float(len(values)) print “Average response time for “+url+” is “+average

Once the loop is complete, we calculate the average of the 100 requests by calculating the total values of the list with sum and dividing it by the number of values in the list with len.

We then return a basic output for ease of understanding.

This is a very basic way of performing this action and only really performs the function as a standalone script to prove a point. To be performed as part of another script, we would do the following:

import requests

import sys

input = sys.argv[1]

def averagetimer(url):

i = 0

values = []

while i < 100:

r = requests.get(url)

values.append(int(r.elapsed.total_seconds()))

i = i + 1

average = sum(values) / float(len(values))

return average

averagetimer(input)