So, we've looked at fuzzing before for XSS and error messages. This time, we're doing something similar but with SQL Injection, instead. The crux of any SQLi starts with a single quotation mark, tick, or apostrophe, depending on your personal choice of word. We throw a tick into the URL targeted and check the response to see what version of SQL is running if successful.

We will create a script that sends the basic SQL Injection string to our targeted URL, record the output, and compare to known phrases in error messages to identify the underlying system.

The script we will be using is as follows:

import requests url = “http://127.0.0.1/SQL/sqli-labs-master/Less-1/index.php?id=” initial = “'” print “Testing “+ url first = requests.post(url+initial) if “mysql” in first.text.lower(): print “Injectable MySQL detected” elif “native client” in first.text.lower(): print “Injectable MSSQL detected” elif “syntax error” in first.text.lower(): print “Injectable PostGRES detected” elif “ORA” in first.text.lower(): print “Injectable Oracle detected” else: print “Not Injectable J J”

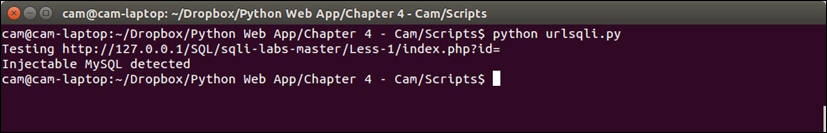

The following is an example of the output produced when using this script:

Testing http://127.0.0.1/SQL/sqli-labs-master/Less-1/index.php?id= Injectable MySQL detected

We import our libraries and set our URL manually. We can set it as a sys.argv variable if needs be; however, I have hardcoded it here to show the expected format. We set the initial injection string as a single quotation mark and print that the test is starting:

url = “http://127.0.0.1/SQL/sqli-labs-master/Less-1/index.php?id=” initial = “'” print “Testing “+ url

We make our first request as our provided URL and the apostrophe:

first = requests.post(url+initial)

The next few lines are our detection methods to identify what the underlying database is. The MySQL standard error is:

You have an error in your SQL syntax; check the manual that corresponds to your MySQL server version for the right syntax to use near '\'' at line 1

Correspondingly, our detection attempt reads in the text of response and searches for the MySQL string and, if so, prints out that the attempt was successful:

if “mysql” in first.text.lower(): print “Injectable MySQL detected”

For MS SQL, an example error message is:

Microsoft SQL Native Client error '80040e14' Unclosed quotation mark after the character string

Since there are multiple potential error messages, we need to identify one constant that occurs across as many of them as possible. For this, I have chosen native client, though Microsoft SQL could also be used:

elif “native client” in first.text.lower(): print “Injectable MSSQL detected”

The standard error message for PostgreSQL is:

Query failed: ERROR: syntax error at or near “'” at character 56 in /www/site/test.php on line 121.

Interestingly, for what is always a syntax error in SQL, the only solution that regularly uses the syntax word is PostGRES, which allows us to use that as the distinguishing word:

elif “syntax error” in first.text.lower(): print “Injectable PostGRES detected”

The last system we check is Oracle. An example error message for Oracle is:

ORA-00933: SQL command not properly ended

ORA is the prefix for the majority of Oracle errors and therefore can be used as the identifier here. There are only a few fringe cases where a non-ORA error message would apply to a trailing tick:

elif “ORA” in first.text.lower(): print “Injectable Oracle detected”

In the event in which none of these apply, we have a final else statement that declares the parameter is not injectable and that an error was made in picking this parameter.

An example output is shown in the following screenshot:

Tying this script in with the spider found in Chapter 1, Gathering Open Source Intelligence, would make for a quick efficient way of identifying injectable URLs across a web page. A method of identifying parameters to inject would be necessary, which can be achieved through simple regex manipulation in most cases.

A set of useful SQLi test pages were made by Audi-1 and can be found at https://github.com/Audi-1/sqli-labs.