The next topic of interest from the HTTP protocol is cookies. As HTTP is a stateless protocol, cookies provide a way to store persistent data on the client side. This allows a web server to have session management by persisting data to the cookie for the length of the session.

Cookies are set from the web server in the HTTP response using a Set-Cookie header. They are then sent back to the server through the Cookie header. This recipe will look at ways to audit the cookies being set by a website to verify if they have secure attributes or not.

The following is a recipe to enumerate through each of the cookies set on a target site and flag any insecure settings that are present:

import requests

req = requests.get('http://www.packtpub.com')

for cookie in req.cookies:

print 'Name:', cookie.name

print 'Value:', cookie.value

if not cookie.secure:

cookie.secure = '\x1b[31mFalse\x1b[39;49m'

print 'Secure:', cookie.secure

if 'httponly' in cookie._rest.keys():

cookie.httponly = 'True'

else:

cookie.httponly = '\x1b[31mFalse\x1b[39;49m'

print 'HTTPOnly:', cookie.httponly

if cookie.domain_initial_dot:

cookie.domain_initial_dot = '\x1b[31mTrue\x1b[39;49m'

print 'Loosly defined domain:', cookie.domain_initial_dot, '\n'We enumerate each cookie sent from the web server and check their attributes. The first two attributes are the name and value of the cookie:

print 'Name:', cookie.name print 'Value:', cookie.value

We then check for the secure flag on the cookie:

if not cookie.secure:

cookie.secure = '\x1b[31mFalse\x1b[39;49m'

print 'Secure:', cookie.secureThe Secure flag on a cookies means it is only sent over HTTPS. This is good for cookies used for authentication because it means they can't be sniffed over the wire if, for example, someone is monitoring open network traffic.

Also note that the \x1b[31m code is a special ANSI escape code used to change the color of the terminal font. Here, we've highlighted the headers that are insecure in red. The \x1b[39;49m code resets the color back to default. See the Wikipedia page on ANSI for more information at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ANSI_escape_code.

The next check is for the httponly attribute:

if 'httponly' in cookie._rest.keys():

cookie.httponly = 'True'

else:

cookie.httponly = '\x1b[31mFalse\x1b[39;49m'

print 'HTTPOnly:', cookie.httponlyIf this is set to True, it means JavaScript cannot access the contents of the cookie, and it is sent to the browser and can only be read by the browser. This is used to mitigate against XSS attempts, so when penetration testing, the lack of this cookie attribute is a good thing.

We finally check for the domain in the cookie, to see if it starts with a dot:

if cookie.domain_initial_dot:

cookie.domain_initial_dot = '\x1b[31mTrue\x1b[39;49m'

print 'Loosly defined domain:', cookie.domain_initial_dot, '\n'If the domain attribute of the cookie starts with a dot, it indicates the cookie is used across all subdomains and therefore possibly visible beyond the intended scope.

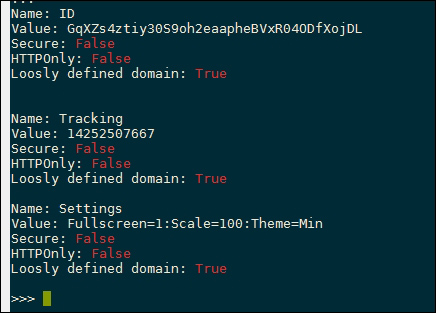

The following screenshot shows how the insecure flags are highlighted in red for the target website:

We've previously seen how to enumerate the technologies used to serve a website by extracting the headers. Certain frameworks also store information in the cookie, for example, PHP creates a cookies called PHPSESSION , which is used to store session data. Therefore, the presence of this data indicates the use of PHP, and the server can then be enumerated further in an attempt to test it for known PHP vulnerabilities.