The next part of the HTTP protocol that we will be concentrating on are the HTTP headers. Found in both the requests and responses from the web server, these carry extra information between the client and server. Any area with extra data makes a great place to parse information about the servers and to look for potential issues.

The following is a simple header grabbing script that will parse the response headers in an attempt to identify the web server technology in use:

import requests

req = requests.get('http://packtpub.com')

headers = ['Server', 'Date', 'Via', 'X-Powered-By', 'X-Country-Code']

for header in headers:

try:

result = req.headers[header]

print '%s: %s' % (header, result)

except Exception, error:

print '%s: Not found' % headerThe first part of the script makes a simple GET request to the target web server, through the familiar requests library:

req = requests.get('http://packtpub.com')Next, we generate an array of headers to look out for:

headers = ['Server', 'Date', 'Via', 'X-Powered-By', 'X-Country- Code']

In this script, we have used a try/except block around the main code:

try:

result = req.headers[header]

print '%s: %s' % (header, result)

except:

print '%s: Not found' % headerWe need this error handling because headers are not mandatory; therefore, if we tried to retrieve a key from the array for a header that didn't exist, Python would raise an exception. To overcome this, we simply print out Not found if the specified header wasn't present in the response.

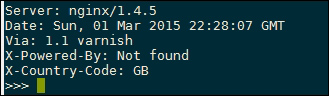

The following is a screenshot of the output from running the script against the target server in this example:

The first output line show the Server header, which displays the underlying web server technology. This is a great place for finding vulnerable web server versions, but be aware that it is possible to disable and also spoof this header, so don't explicitly rely on this for guessing the target server platform.

The Date header contains useful information that can be used to guess where the server is located. For example, you can figure out the time difference relative to your local time zone to give a rough indication of where it is.

The Via header is used by proxies, both outgoing and incoming, and will display the proxy name, in this case 1.1 varnish.

The X-Powered-By is a standard header used in common web frameworks such as PHP. A default PHP installation will respond with PHP and the version number, making it another great target for reconnaissance.

The final line prints the X-Country-Code short code, another useful piece of information to identify where the server is located.

Be aware that all these headers can be set or overridden on the server side, so do not rely on this information explicitly and be wary of parsing data directly from remote servers; even these headers could contain malicious values.

This script currently contain the version of the server, but it could then be extended further to query online CVE databases, such as https://cve.mitre.org/cve/, looking for vulnerabilities affecting the web server version.

Another technique that can be used to increase the confidence of fingerprinting is to check the order of the response headers. For example, Microsoft IIS returns the Server header before the Date header, whereas Apache returns Date and then Server. This slightly different ordering can be used to verify any server versions that you may have deduced from the header values in this recipe.