Chapter 5. Python Basics

5.0 Introduction

Although there are many languages that can be used to program the Raspberry Pi, Python is the most popular. In fact, the Pi in Raspberry Pi is inspired by the word Python.

In this chapter, you will find a host of recipes to help you get programming with Raspberry Pi.

5.1 Deciding Between Python 2 and Python 3

Solution

Use both. Use Python 3 until you face a problem that is best solved by reverting to version 2.

Discussion

Although the latest version of Python is Python 3 and has been for years, you will find that a lot of people stick to Python 2. In fact, in the Raspbian distribution, both versions are supplied and version 2 is just called Python, whereas version 3 is called Python 3. You even run Python 3 by using the command python3. The examples in this book are written for Python 3 unless otherwise stated. Most will run on both Python 2 and Python 3 without modification.

This reluctance on the part of the Python community to ditch the old Python 2 is largely because Python 3 introduced some changes that broke compatibility with version 2. This means that some of the huge body of third-party libraries that have been developed for Python 2 won’t work under Python 3.

My strategy is to write in Python 3 wherever possible, and revert to Python 2 when I have to because of compatibility problems.

See Also

For a good summary of the Python 2 versus Python 3 debate, see the Python wiki.

5.2 Editing Python Programs with IDLE

Solution

The common Raspberry Pi distributions come with the IDLE Python development tool in both the Python 2 and Python 3 versions. If you are using Raspbian, you will find shortcuts to both versions of IDLE labeled Python 2 and Python 3 in the Programming section of your Start menu (Figure 5-1).

Figure 5-1. Starting Python with IDLE

Discussion

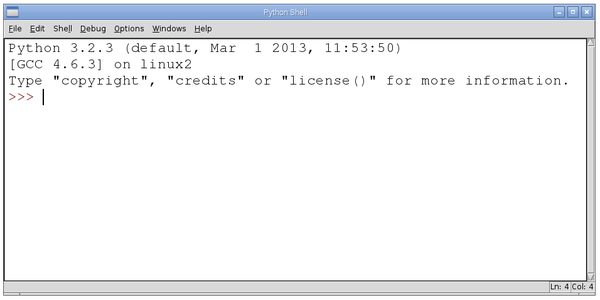

IDLE and IDLE 3 appear to be identical; the only difference is the version of Python that they use, so open IDLE 3 (Figure 5-2).

Figure 5-2. IDLE Python console

The window that opens is labeled Python Shell. This is an interactive area where you can type Python and see the results immediately. So try typing the following into the shell next to the >>> prompt:

>>>2+24>>>

Python has evaluated the expression 2 + 2 and given us the answer of 4.

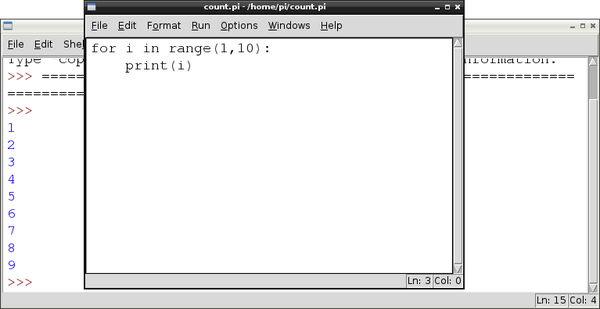

The Python Shell is fine for trying things out, but if you want to write programs, then you need to use an editor. To open a new file to edit using IDLE, select New Window from the File menu (Figure 5-3).

You can now enter your program into the editor window. Just to try things, paste the following text into the editor, save the file as count.py, and then select Run Module from the Run menu. You can see the results of the program running in the Python console:

foriinrange(1,10):(i)

Figure 5-3. IDLE editor

Python is unusual for a programming language in that indentation is a fundamental part of the language. Whereas many C-based languages use { and } to delimit a block of code, Python uses the indentation level. So in the preceding example, Python knows that print is to be invoked repeatedly as part of the for loop because it is indented out four spaces.

The convention used in this book is to use four spaces for a level of indentation.

Tip

When you’re starting out in Python, it’s not uncommon to see an error such as IndentationError: unexpected indent, which means that somewhere things are not indented correctly. If everything appears to line up, double-check that none of the indents contain Tab characters. Python treats tabs differently.

Notice how IDLE uses color-coding to highlight the structure of the program.

See Also

Many of the recipes in this chapter use IDLE to edit Python examples.

As well as using IDLE to edit and run Python files, you can also edit files in nano (Recipe 3.6) and then run them from a Terminal session (Recipe 5.4).

5.3 Using the Python Console

Solution

Use the Python console, either within IDLE (Recipe 5.2) or in a Terminal session.

Discussion

To start a Python 2 console in a Terminal window, just type the command python; for a Python 3 console, enter the command python3.

The >>> prompt indicates that you can type Python commands. If you need to type multiline commands, then the console will automatically provide a continuation line indicated by three dots. You still need to indent any such lines, by four spaces, as shown in the following session:

>>>foriinrange(1,10):...(i)...123456789>>>

You will need to press Enter twice after your last command for the console to recognize the end of the indented block and run the code.

The Python console also provides a command history so that you can move back and forth through your previous commands using the up and down keys.

See Also

If you have more than a couple of lines that you want to type in, then chances are you would be better off using IDLE (Recipe 5.2) to edit and run a file.

5.4 Running Python Programs from the Terminal

Solution

Use the python or python3 command in a Terminal, followed by the filename containing the program you want to run.

Discussion

To run a Python 2 program from the command line, use a command like this:

$ python myprogram.py

If you want to run the program using Python 3, then change the command python to python3. The Python program that you wish to run should be in a file with the extension .py.

You can run most Python programs as a normal user; however, there are some, especially those that use the GPIO port, that you need to run as superuser. If this is the case for your program, prefix the command with sudo:

$ sudo python myprogram.py

In the earlier examples, you have to include python in the command to run the program, but you can also add a line to the start of a Python program so that Linux knows it is a Python program. This special line is called a shebang (a contraction of hash-bang) and the following single-line example program has it as its first line.

#!/usr/bin/python

print("I'm a program, I can run all by myself")

Before you can run this directly from the command line, you have to give the file write permissions by using the command below (see Recipe 3.13).

$ chmod +x test.py

The parameter +x means add execute permission.

Now you will be able to run the Python program test.py by using the single command:

$ ./test.py I'm a program, I can run all by myself $

The ./ at the start of the line is needed for the command line to find the file.

See Also

Recipe 3.23 allows you to run a Python program as a timed event.

To automatically run a program at startup, see Recipe 3.22.

5.5 Variables

Solution

Assign a value to a name using =.

Discussion

In Python, you don’t have to declare the type of a variable, you can just assign it a value, as shown in the following examples:

a=123b=12.34c="Hello"d='Hello'e=True

You can define character-string constants using either single or double quotes. The logical constants in Python are True and False, and are case-sensitive.

By convention, variable names begin with a lowercase letter and if the variable name consists of more than one word, the words are joined together with an underscore character. It is always a good idea to give your variables descriptive names.

Some examples of valid variable names are x, total, and number_of_chars.

See Also

Variables can also be assigned a value that is a list (Recipe 6.1) or dictionary (Recipe 6.12).

For more information on arithmetic with variables, see Recipe 5.8.

5.6 Displaying Output

Solution

Use the print command. You can try the following example in the Python console (Recipe 5.3):

>>>x=10>>>(x)10>>>

Discussion

In Python 2, you can use the print command without brackets. However, this is not true in Python 3, so for compatibility with both versions of Python, use brackets around the value you are printing.

See Also

To read user input, see Recipe 5.7.

5.7 Reading User Input

Solution

Use the input (Python 3) or raw_input (Python 2) command. You can try the following example in the Python 3 console (Recipe 5.3):

>>>x=input("Enter Value:")EnterValue:23>>>(x)23>>>

Discussion

In Python 2, raw_input must be substituted for input in the preceding example.

Python 2 also has an input function, but this validates the input and attempts to convert it into a Python value of the appropriate type, whereas raw_input does the same thing as input in Python 3 and just returns a string.

See Also

Find more information on Python 2 input.

5.8 Arithmetic

Solution

Use the +, -, *, and / operators.

Discussion

The most common operators for arithmetic are +, -, *, and /, which are, respectively, add, subtract, multiply, and divide.

You can also group parts of the expression together with parentheses, as shown in the following example, which, given a temperature in degrees Celsius, converts it to degrees Fahrenheit:

>>>tempC=input("Enter temp in C: ")EntertempinC:20>>>tempF=(int(tempC)*9)/5+32>>>(tempF)68.0>>>

Other arithmetic operators include % (modulo remainder) and ** (raise to the power of). For example, to raise 2 to the power of 8, you would write the following:

>>>2**8256

See Also

See Recipe 5.7 on using the input command, and Recipe 5.12 on converting the string value from input to a number.

The Math library has many useful math functions that you can use.

5.9 Creating Strings

Solution

Use the assignment operator and a string constant to create a new string. You can use either double or single quotation marks around the string, but they must match.

For example:

>>>s="abc def">>>(s)abcdef>>>

Discussion

If you need to include double or single quotes inside a string, then pick the type of quotes that you don’t want to use inside the string as the beginning and end markers of the string. For example:

>>>s="Isn't it warm?">>>(s)Isn't it warm?>>>

Sometimes you’ll need to include special characters such as tab or newline inside your string. This requires the use of what are called escape characters. To include a tab, use \t, and for a newline, use \n. For example:

>>>s="name\tage\nMatt\t14">>>(s)nameageMatt14>>>

See Also

For a full list of escape characters, see the Python Reference Manual.

5.10 Concatenating (Joining) Strings

Solution

Use the + (concatenate) operator.

For example:

>>>s1="abc">>>s2="def">>>s=s1+s2>>>(s)abcdef>>>

Discussion

In many languages, you can have a chain of values to concatenate, some of which are strings and some of which are other types such as numbers; numbers will automatically be converted into strings during the concatenation. This is not the case in Python, and if you try the following command, you will get an error:

>>>"abc"+23Traceback(mostrecentcalllast):File"<stdin>",line1,in<module>TypeError:Can't convert 'int' object to str implicitly

You need to convert each component that you want to concatenate to a string before concatenating, as shown in this example:

>>>"abc"+str(23)'abc23'>>>

See Also

See Recipe 5.11 for more information about converting numbers to strings using the str function.

5.11 Converting Numbers to Strings

Solution

Use the str Python function. For example:

>>>str(123)'123'>>>

Discussion

A common reason for wanting to convert a number into a string is so you can then concatenate it with another string (Recipe 5.10).

See Also

For the reverse operation of turning a string into a number, see Recipe 5.12.

5.12 Converting Strings to Numbers

Solution

Use the int or float Python function.

For example, to convert -123 into a number, you could use:

>>>int("-123")-123>>>

This will work on both positive and negative whole numbers.

To convert a floating-point number, use float instead of int:

>>>float("00123.45")123.45>>>

Discussion

Both int and float will handle leading zeros correctly and are tolerant of any spaces or other whitespace characters around the number.

You can also use int to convert a string representing a number in a number base other than the default of 10 by supplying the number base as the second argument. The following example converts the string representation of binary 1001 into a number:

>>>int("1001",2)9>>>

This second example converts the hexadecimal number AFF0 to an integer:

>>>int("AFF0",16)45040>>>

See Also

For the reverse operation of turning a number into a string, see Recipe 5.11.

5.13 Finding the Length of a String

Solution

Use the len Python function.

Discussion

For example, to find the length of the string abcdef, you would use:

>>>len("abcdef")6>>>

See Also

The len command also works on lists (Recipe 6.3).

5.14 Finding the Position of One String Inside Another

Solution

Use the find Python function.

For example, to find the starting position of the string def within the string abcdefghi, you would use:

>>>s="abcdefghi">>>s.find("def")3>>>

Note that the character positions start at 0, so a position of 3 means the fourth character in the string.

Discussion

If the string you’re looking for doesn’t exist in the string being searched, then find returns the value -1.

See Also

The replace function is used to find and then replace all occurrences of a string (Recipe 5.16).

5.15 Extracting Part of a String

Solution

Use the Python [:] notation.

For example, to cut out a section from the second character to the fifth character of the string abcdefghi, you would use:

>>>s="abcdefghi">>>s[1:5]'bcde'>>>

Note that the character positions start at 0, so a position of 1 means the second character in the string, and 5 means the sixth, but the character range is exclusive at the high end so the letter f is not included in this example.

Discussion

The [:] notation is actually quite powerful. You can omit either argument, in which case, the start or end of the string is assumed as appropriate. For example:

>>>s[:5]'abcde'>>>

and

>>>s="abcdefghi">>>s[3:]'defghi'>>>

You can also use negative indices to count back from the end of the string. This can be useful in situations such as when you want to find the three-letter extension of a file, as in the following example:

>>>"myfile.txt"[-3:]'txt'

See Also

Recipe 5.10 describes joining strings together rather than splitting them.

Recipe 6.10 uses the same syntax but with lists rather than strings.

5.16 Replacing One String of Characters with Another Inside a String

Solution

Use the replace function.

For example, to replace all occurrences of X with times, you would use:

>>>s="It was the best of X. It was the worst of X">>>s.replace("X","times")'It was the best of times. It was the worst of times'>>>

Discussion

The string being searched for must match exactly; that is, the search is case-sensitive and will include spaces.

See Also

See Recipe 5.14 for searching a string without performing a replacement.

5.17 Converting a String to Upper- or Lowercase

Solution

Use the upper or lower function as appropriate.

For example, to convert aBcDe to uppercase, you would use:

>>>"aBcDe".upper()'ABCDE'>>>

To convert it to lowercase, you would use:

>>>"aBcDe".lower()'abcde'>>>

Discussion

Like most functions that manipulate a string in some way, upper and lower do not actually modify the string but rather return a modified copy of the string.

For example, the following code returns a copy of the string s, but note how the original string is unchanged.

>>>s="aBcDe">>>s.upper()'ABCDE'>>>s'aBcDe'>>>

If you want to change the value of s to be all uppercase, then you need to do the following:

>>>s="aBcDe">>>s=s.upper()>>>s'ABCDE'>>>

See Also

See Recipe 5.16 for replacing text within strings.

5.18 Running Commands Conditionally

Solution

Use the Python if command.

The following example will print the message x is big only if x has a value greater than 100:

>>>x=101>>>ifx>100:...("x is big")...xisbig

Discussion

After the if keyword, there is a condition. This condition often, but not always, compares two values and gives an answer that is either True or False. If it is True, then the subsequent indented lines will all be executed.

It is quite common to want to do one thing if a condition is True and something different if the answer is False. In this case, the else command is used with if, as shown in this example:

x=101ifx>100:("x is big")else:("x is small")("This will always print")

You can also chain together a long series of elif conditions. If any one of the conditions succeeds, then that block of code is executed and none of the other conditions are tried. For example:

x=90ifx>100:("x is big")elifx<10:("x is small")else:("x is medium")

This example will print x is medium.

See Also

See Recipe 5.19 for more information on different types of comparisons you can make.

5.19 Comparing Values

Discussion

You used the < (less than) and > (greater than) operators in Recipe 5.18. Here’s the full set of comparison operators:

| < | Less than |

| > | Greater than |

| <= | Less than or equal to |

| >= | Greater than or equal to |

| == | Exactly equal to |

| != | Not equal to |

Some people prefer to use the <> operator in place of !=. Both work the same.

You can test these commands using the Python console (Recipe 5.3), as shown in the following exchange:

>>>1!=2True>>>1!=1False>>>10>=10True>>>10>=11False>>>10==10True>>>

A common mistake is to use = (set a value) instead of == (double equals) in comparisons. This can be difficult to spot because if one half of the comparison is a variable, it is perfectly legal syntax and will run, but it will not produce the result you were expecting.

As well as comparing numbers, you can also compare strings by using these comparison operators, as shown here:

>>>'aa'<'ab'True>>>'aaa'<'aa'False

The strings are compared lexicographically—that is, in the order that you would find them in a dictionary.

This is not quite correct because, for each letter, the uppercase version of the letter is considered less than the lowercase equivalent. Each letter has a value that is its ASCII code.

5.20 Logical Operators

Solution

Use one of the logical operators: and, or, and not.

Discussion

As an example, you may want to check whether a variable x has a value between 10 and 20. For that, you would use the and operator:

>>>x=17>>>ifx>=10andx<=20:...('x is in the middle')...xisinthemiddle

You can combine as many and and or statements as you need and also use brackets to group them if the expressions become complicated.

5.21 Repeating Instructions an Exact Number of Times

Solution

Use the Python for command and iterate over a range.

For example, to repeat a command 10 times, use the following example:

>>>foriinrange(1,11):...(i)...12345678910>>>

See Also

If the condition for stopping the loop is more complicated than simply repeating a number of times, see Recipe 5.22.

If you are trying to repeat commands for each element of a list or dictionary, see Recipes 6.7 or 6.15, respectively.

5.22 Repeating Instructions Until Some Condition Changes

Problem

You need to repeat some program code until something changes.

Solution

Use the Python while statement. The while statement repeats its nested commands until its condition becomes false. The following example will stay in the loop until the user enters X for exit:

>>>answer=''>>>whileanswer!='X':...answer=input('Enter command:')...Entercommand:AEntercommand:BEntercommand:X>>>

Discussion

Note that the preceding example uses the input command as it works in Python 3. To run the example in Python 2, substitute the command raw_input for input.

See Also

If you just want to repeat some commands a number of times, see Recipe 5.21.

If you are trying to repeat commands for each element of a list or dictionary, then see Recipes 6.7 or 6.15, respectively.

5.23 Breaking Out of a Loop

Solution

Use the Python break statement to exit either a while or for loop.

The following example behaves in exactly the same way as the example code in Recipe 5.22:

>>>whileTrue:...answer=input('Enter command:')...ifanswer=='X':...break...Entercommand:AEntercommand:BEntercommand:X>>>

Discussion

Note that this example uses the input command as it works in Python 3. To run the example in Python 2, substitute the command raw_input for input.

This example behaves in exactly the same way as the example of Recipe 5.22. However, in this case, the condition for the while loop is just True, so the loop will never end unless we use break to exit the loop when the user enters X.

See Also

You can also leave a while loop by using its condition; see Recipe 5.18.

5.24 Defining a Function in Python

Solution

Create a function that groups together lines of code, allowing it to be called from multiple places.

Creating and then calling a function in Python is illustrated in the following example:

defcount_to_10():foriinrange(1,11):(i)count_to_10()

In this example, we have defined a function using the def command that will print out the numbers between 1 and 10 whenever it is called:

count_to_10()

Discussion

The conventions for naming functions are the same as for variables in Recipe 5.5; that is, they should start with a lowercase letter, and if the name consists of more than one word, the words should be separated by underscores.

The example function is a little inflexible because it can only count to 10. If we wanted to make it more flexible—so it could count up to any number—then we can include the maximum number as a parameter to the function, as this example illustrates:

defcount_to_n(n):foriinrange(1,n+1):(i)count_to_n(5)

The parameter name n is included inside the parentheses and then used inside the range command, but not before 1 is added to it.

Using a parameter for the number you want to count up to means that if you usually count to 10 but sometimes count to a different number, you will always have to specify the number. You can, however, specify a default value for a parameter, and hence have the best of both worlds, as shown in this example:

defcount_to_n(n=10):foriinrange(1,n+1):(i)count_to_n()

This will now count to 10 unless a different number is specified when you call the function.

If your function needs more than one parameter, perhaps to count between two numbers, then the parameters are separated by commas:

defcount(from_num=1,to_num=10):foriinrange(from_num,to_num+1):(i)count()count(5)count(5,10)

All these examples are functions that do not return any value; they just do something. If you need a function to return a value, you need to use the return command.

The following function takes a string as an argument and adds the word please to the end of the string.

defmake_polite(sentence):returnsentence+" please"(make_polite("Pass the cheese"))

When a function returns a value, you can assign the result to a variable, or as in this example, print out the result.

See Also

To return more than one value from a function, see Recipe 7.3.