Chapter 3. Operating System

3.1 Moving Files Around Graphically

Solution

Use the File Manager.

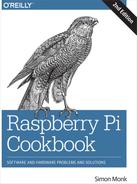

You can find this program on your Start menu in the Accessories group (Figure 3-1).

Using the File Manager, you can drag a file or directory from one directory to another or use the Edit menu to copy a file from one location and paste it to a second. This operates in much the same way as the Windows File Manager or Mac OS X Finder.

Figure 3-1. The File Manager

Discussion

The lefthand side of the File Manager shows the volumes that are mounted, so if you connect a USB flash drive or external USB drive, it will appear here.

The central area displays the files in the current folder, which you can navigate using the buttons in the toolbar or by typing a location in the file path area at the top.

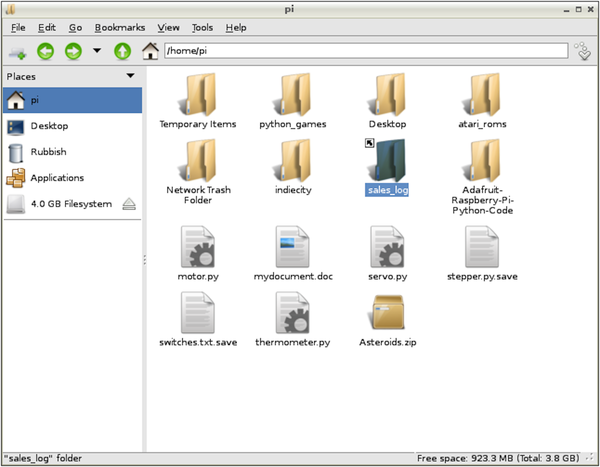

Right-click a file to reveal options that can be used on that file (Figure 3-2).

Figure 3-2. The File Manager options

See Also

See also Recipe 3.4.

3.2 Starting a Terminal Session

Solution

Select the LX Terminal icon (looks like a black computer monitor) at the top of the Raspberry Pi Desktop, or select the Terminal menu option on the Start menu in the Accessories group (Figure 3-3).

Figure 3-3. Opening LX Terminal

Discussion

When the LX Terminal starts, it is set to your home directory (/home/pi).

You can open as many Terminal sessions as you want. It is often useful to have a couple of sessions open in different directories so that you don’t have to constantly switch directories using cd (Recipe 3.3).

See Also

In the next section (Recipe 3.3), you will look at navigating the directory structure using the Terminal.

3.3 Navigating the Filesystem Using a Terminal

Solution

The main command used for navigating the filesystem is cd (change directory). After cd, you have to specify the directory that you want to change to. This can either be a relative path to a directory inside your current directory, or an absolute path to somewhere else on the filesystem.

To see what the current directory is, you can use the command pwd (print working directory).

Discussion

Try out a few examples. Open a Terminal session, and you should see a prompt like this:

pi@raspberrypi ~ $

The prompt that you will see after each command (pi@raspberrypi ~ $) is a reminder of your username (pi) and your computer name (raspberrypi). The ~ character is shorthand for your home directory (/home/pi). So, at any point, you can change your current directory to your home directory as follows:

$ cd ~

Tip

Throughout the book, I use a $ at the start of each line where you are expected to type a command. The response from the command line will not be prefixed by anything; it will appear just as it does on the Raspberry Pi’s screen.

You can confirm that the command did indeed set the directory to the home directory by using the pwd command:

$ pwd /home/pi

If you want to move up one level in the directory structure, you can use the special value .. (two dots) after the cd command, as shown here:

$ cd .. $ pwd /home

As you may have deduced by now, the path to a particular file or directory is made up of words separated by a /. So the very root of the whole filesystem is /, and to access the home directory within / you would refer to /home/. Then, to find the pi directory within that, you would use /home/pi/. The final / can be omitted from a path.

Paths can also be absolute (starting with a / and specifying the full path from the root), or they can be relative to the current working directory, in which case they must not start with a /.

You will have full read and write access to the files in your home directory, but once you move into the places where system files and applications are kept, your access to some files will be restricted to read only. You can override this (Recipe 3.11), but some care is required.

Check out the root of the directory structure by entering the following commands:

$ cd / $ ls bin dev home lost+found mnt proc run selinux sys usr boot etc lib media opt root sbin srv tmp var

The ls command (list) shows us all the files and directories underneath / the root directory. You will see that there is a home directory listed, which is the directory you have just come from.

Now change into one of those directories by using the command:

$ cd etc $ ls adduser.conf hosts.deny polkit-1 alternatives hp profile apm iceweasel profile.d apparmor.d idmapd.conf protocols apt ifplugd pulse asound.conf init python

You will notice a couple of things. First, there are a lot of files and folders listed, more than can fit on the screen at once. Use the scroll bar on the side of the Terminal window to move up and down.

Second, you will see that the files and folders have some color-coding. Files are displayed in white, whereas directories are blue.

Unless you particularly like typing, the Tab key offers a convenient shortcut. If you start typing the name of a file, pressing the Tab key allows the autocomplete feature to attempt to complete the filename. For example, if you’re going to change directory to network, type the command cd netw and then press the Tab key. Because netw is enough to uniquely identify the file or directory, pressing the Tab key will autocomplete it.

If what you have typed is not enough to uniquely identify the file or directory name, then pressing the Tab key another time will display a list of possible options that match what you have typed so far. So, if you had stopped at net and pressed the Tab key, you would see the following:

$ cd net netatalk/ network/

You can provide an extra argument after ls to narrow down the things you want to list. Change directory to /etc and then run the following:

$ ls f* fake-hwclock.data fb.modes fstab fuse.conf fonts: conf.avail conf.d fonts.conf fonts.dtd foomatic: defaultspooler direct filter.conf fstab.d: pi@raspberrypi /etc $

The * character is called a wildcard. In specifying f* after ls, we are saying that we want to list everything that starts with an f.

Helpfully, the results first list all the files within /etc that start with f, and then the contents of all the directories in that folder starting with f.

A common use of wildcards is to list all files with a certain extension (e.g., ls *.docx).

A convention in Linux (and many other operating systems) is to prefix files that should be hidden from the user by starting their name with a period. Any so-named files or folders will not appear when you type ls unless you also supply ls with the option -a. For example:

$ cd ~ $ ls -a . Desktop .pulse .. .dillo .pulse-cookie Adafruit-Raspberry-Pi-Python-Code .dmrc python_games .advance .emulationstation sales_log .AppleDB .fltk servo.py .AppleDesktop .fontconfig .stella .AppleDouble .gstreamer-0.10 stepper.py.save Asteroids.zip .gvfs switches.txt.save atari_roms indiecity Temporary Items .bash_history .local thermometer.py .bash_logout motor.py .thumbnails .bashrc .mozilla .vnc .cache mydocument.doc .Xauthority .config Network Trash Folder .xsession-errors .dbus .profile .xsession-errors.old

As you can see, most of the files and folders in your home directory are hidden.

See Also

See also Recipe 3.13.

3.4 Copying a File or Folder

Solution

Use the cp command to copy files and directories.

Discussion

You can, of course, copy files by using the File Manager and its copy and paste menu options (Recipe 3.1).

The simplest example of copying in a Terminal session is to make a copy of a file within your working directory. The cp command is followed first by the file to copy, and then by the name to be given to the new file.

For example, the following example creates a file called myfile.txt and then makes a copy of it with the name myfile2.txt. You can find out more about the trick of creating a file using the > command in Recipe 3.8.

$ echo "hello" > myfile.txt $ ls myfile.txt $ cp myfile.txt myfile2.txt $ ls myfile.txt myfile2.txt

Although in this example, both file paths are local to the current working directory, the file paths can be to anywhere in the filesystem where you have write access. The following example copies the original file to an area /tmp, which is a location for temporary files. Do not put anything important in that folder.

$ cp myfile.txt /tmp

Note that in this case, the name to be given to the new file is not specified, just the directory where it is to go. This will create a copy of myfile.txt in /tmp with the same name of myfile.tmp.

Sometimes, rather than copying just one file, you may want to copy a whole directory full of files and possibly other directories. To copy such a directory, you need to use the -r option (for recursive). This will copy the directory and all its contents.

$ cp -r mydirectory mydirectory2

Whenever you are copying files or folders, if you do not have permission, the result of the command will tell you that. You will need to either change the permissions of the folder into which you are copying (Recipe 3.13) or copy the files with superuser privileges (Recipe 3.11).

3.5 Renaming a File or Folder

Discussion

The mv (move) command is used in a similar way to the cp command, except that the file or folder being moved is simply renamed rather than a duplicate being made.

For example, to simply rename a file from my_file.txt to my_file.rtf, you use the command:

$ mv my_file.txt my_file.rtf

Changing a directory name is just as straightforward, and you don’t need the recursive -r option you used when copying because changing a directory’s name implicitly means that everything within it is contained in a renamed directory.

3.6 Editing a File

Solution

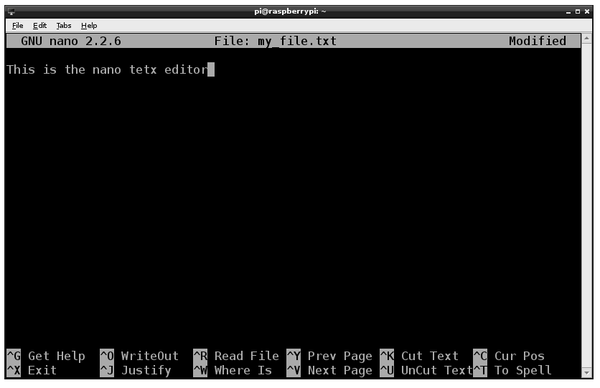

Use the editor nano included with most Raspberry Pi distributions.

Discussion

To use nano, simply type the command nano followed by the name or path to the file that you want to edit. If the file does not exist, it will be created when you save it from the editor. However, this will only happen if you have write permissions in the directory where you are trying to write the file.

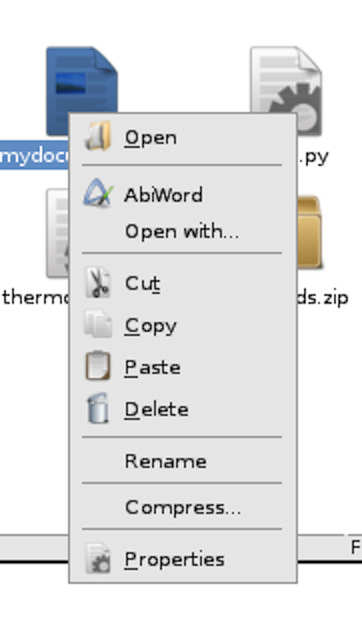

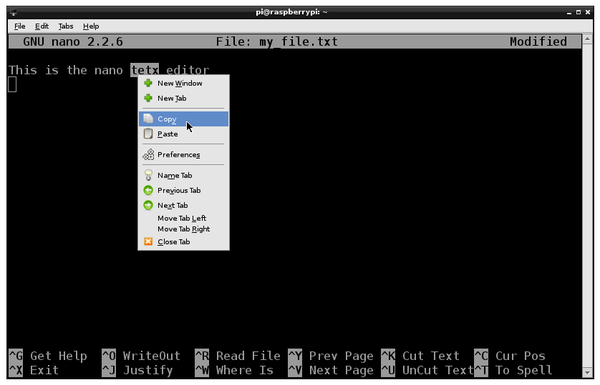

From your home directory, type the command nano my_file.txt to edit or create the file nano my_file.txt. Figure 3-4 shows nano in action.

Figure 3-4. Editing a file with nano

You cannot use the mouse to position the cursor; use the arrow keys instead.

The area at the bottom of the screen lists a number of commands that you access by holding down the Ctrl key and pressing the letter indicated. Most of these are not that useful. The ones that you are likely to use most of the time are:

- Ctrl-X

-

Exit. You will be prompted to save the file before nano exits.

- Ctrl-V

-

Next page. Think of it as an arrow pointing downward. This allows you to move through a large file one screen at a time.

- Ctrl-Y

-

Previous page.

- Ctrl-W

-

Where is. This allows you to search for a piece of text.

There are also some fairly crude cut-and-paste type options there, but in practice, it’s easier to use the normal clipboard from the menu that you access with a right-click.

Figure 3-5. Using the clipboard in nano

Using this clipboard also allows you to copy and paste text between other windows such as your browser.

When you’re ready to save your changes to the file and exit nano, use the command Ctrl-X. Type Y to confirm that you want to save the file. nano then displays the filename as the default name to save the file under. Press Enter to save and exit.

If you want to abandon changes you have made, enter N in place of Y.

See Also

Editors are very much a matter of personal taste. Many other editors that are available for Linux will work just fine on Raspberry Pi. The vim (vi improved) editor has many fans in the Linux world. This is also included in the popular Raspberry Pi distributions. It is not, however, an easy editor for the beginner. You can run it in the same way as nano, but using the command vi instead of nano. There are more details on using vim at http://newbiedoc.sourceforge.net/text_editing/vim.html.en.

3.7 Viewing the Contents of a File

Discussion

The cat command displays the whole contents of the file, even if it is longer than will fit on the screen.

The more command just displays one screen of text at a time. Press the space bar to display the next screen.

See Also

You can also use cat to concatenate (join together) a number of files (Recipe 3.30).

Another popular command related to more is less. less is like more except it allows you to move backward in the file as well as forward.

3.8 Creating a File Without Using an Editor

Discussion

This can be useful for quickly creating a file.

See Also

To use the more command to view files without using an editor, see Recipe 3.7.

To use > to capture other kinds of system output, see Recipe 3.29.

3.9 Creating a Directory

Discussion

To create a directory, use the mkdir command. Try out the following example:

$ cd ~ $ mkdir my_directory $ cd my_directory $ ls

You need to have write permission in the directory within which you are trying to create the new directory.

See Also

For general information on using the Terminal to navigate the filesystem, see Recipe 3.3.

3.10 Deleting a File or Directory

Solution

The rm (remove) command will delete a file or directory and its contents. It should be used with extreme caution.

Discussion

Deleting a single file is simple and safe. The following example will delete the file my_file.txt from the home directory:

$ cd ~ $ rm my_file.txt $ ls

You need to have write permission in the directory within which you are trying to carry out the deletion.

You can also use the * wildcard when deleting files. This example will delete all the files starting with my_file. in the current directory:

$ rm my_file.*

You could also delete all the files in the directory by typing:

$ rm *

If you want to recursively delete a directory and all its contents, including any directories that it contains, you can use the -r option:

$ rm -r mydir

Warning

When deleting files from a Terminal window, remember that you do not have the safety net of a recycle bin from which files can be undeleted. Also, generally speaking, you won’t be given the option to confirm; the files will just be immediately deleted. This can be totally devastating if you combine it with the command sudo (Recipe 3.11).

See Also

See also Recipe 3.3.

If you are concerned about accidentally deleting files or folders, you can force the rm command to confirm by setting up a command alias (Recipe 3.34).

3.11 Performing Tasks with Superuser Privileges

Solution

The sudo (substitute user do) command allows you to perform actions with superuser privileges. Just prefix the command with sudo.

Discussion

Most tasks that you want to perform on the command line can usually be performed without superuser privileges. The most common exceptions to this are when you’re installing new software and editing configuration files.

For example, if you try to use the command apt-get update, you will receive a number of permission denied messages:

$ apt-get update E: Could not open lock file /var/lib/apt/lists/lock - open (13: Permission denied) E: Unable to lock directory /var/lib/apt/lists/ E: Could not open lock file /var/lib/dpkg/lock - open (13: Permission denied) E: Unable to lock the administration directory (/var/lib/dpkg/), are you root?

The message at the end—are you root?—gives the game away. If you issue the same command prefixed with sudo, the command will work just fine:

$ sudo apt-get update Get:1 http://mirrordirector.raspbian.org wheezy InRelease [12.5 kB] Hit http://archive.raspberrypi.org wheezy InRelease Get:2 http://mirrordirector.raspbian.org wheezy/main Sources [6,241 kB] Hit http://archive.raspberrypi.org wheezy/main armhf Packages Ign http://archive.raspberrypi.org wheezy/main Translation-en_GB Ign http://archive.raspberrypi.org wheezy/main Translation-en 40% [2 Sources 2,504 kB/6,241 kB 40%]

If you have a whole load of commands to run as superuser and don’t want to have to prefix each command with sudo, you can use the following command:

$ sudo sh #

Note how the prompt changes from $ to #. All subsequent commands will be run as superuser. When you want to revert to being a regular user, enter the command:

# exit $

See Also

To understand more about file permissions, see Recipe 3.12.

To install software using apt-get, see Recipe 3.16.

3.12 Understanding File Permissions

Discussion

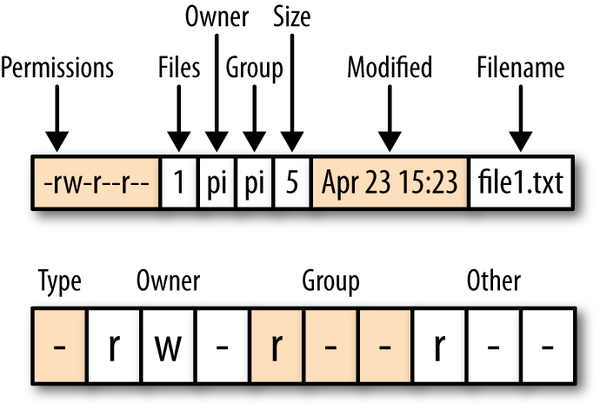

Run the command ls -l, and you will see a result like this:

$ ls -l total 16 -rw-r--r-- 1 pi pi 5 Apr 23 15:23 file1.txt -rw-r--r-- 1 pi pi 5 Apr 23 15:23 file2.txt -rw-r--r-- 1 pi pi 5 Apr 23 15:23 file3.txt drwxr-xr-x 2 pi pi 4096 Apr 23 15:23 mydir

Figure 3-6 shows the different sections of the listing information. The first section contains the permissions. In the second column, the number 1 (labeled “Files”) indicates how many files are involved. This field only makes sense if the listing entry is for a directory; if it is a file, it will mostly be just 1. The next two entries (both pi) are the owner and group of the file. The size entry (the fifth column) indicates the size of the file in bytes. The modified date will change every time the file is edited or changed and the final entry is the actual name of the file or directory.

Figure 3-6. File permissions

The permissions string is split into four sections (Type, Owner, Group, and Other). The first section is the type of the file. If this is a directory, it will be the character d; if it is just a file, the entry will be just a -.

The next section of three characters specifies the owner permissions for that file. Each character is a flag that is either on or off. So if the owner has read permissions, there will be a r in the first character position. If he has write permissions, there will be a w in the second slot. The third position, which is - in this example, can be x if the file is executable (a program or script) for the owner.

The third section has the same three flags but for any users in the group. Users can be organized into groups. So, in this case, the file has a user pi and a group ownership of pi. If there were any other users in the group pi, they would have the permissions specified here.

The final section specifies the permissions for any other users who are neither pi nor in the group pi.

Since most people will only ever use the Raspberry Pi as the user pi, the permissions of most interest are in the first section.

See Also

To change file permissions, see Recipe 3.13.

3.13 Changing File Permissions

Discussion

Common reasons why you might want to change file permissions include needing to edit a file that is marked as read-only and giving a file execute permissions so that it can run as a program or script.

The chmod command allows you to add or remove permissions for a file. There are two syntaxes for doing this; one requires the use of octal (base 8) and the other is text-based. You will use the easier-to-understand text method.

The first parameter to chmod is the change to make, and the second is the file or folder to which it should apply. This change parameter takes the form of the permission scope (+, -, = for add, remove, and set, respectively) and then the permission type.

For example, the following code will add execute (x) rights to the file for the owner of the file file2.txt.

$ chmod u+x file2.txt

If we now list the directory, we can see that the x permission has been added.

$ ls -l total 16 -rw-r--r-- 1 pi pi 5 Apr 23 15:23 file1.txt -rwxr--r-- 1 pi pi 5 Apr 24 08:08 file2.txt -rw-r--r-- 1 pi pi 5 Apr 23 15:23 file3.txt drwxr-xr-x 2 pi pi 4096 Apr 23 15:23 mydir

If we wanted to add execute permission for the group or other users, then we could use g and o, respectively. The letter a will add the permission to everyone.

See Also

For background on file permissions, see Recipe 3.12.

See Recipe 3.14 for changing file ownership.

3.14 Changing File Ownership

Discussion

As we discovered in Recipe 3.12, any file or directory has both an owner and a group associated with it. Since most users of the Raspberry Pi will just have the single user of pi, we don’t really need to worry about groups.

Occasionally, you will find files on your system that have been installed with a different user than pi. If this is the case, you can change the ownership of the file by using the chown command.

To just change the owner of a file, use chown followed by the new owner and group, separated by a colon, and then the name of the file.

You will probably find that you need superuser privileges to change ownership, in which case, prefix the command with sudo (Recipe 3.11).

$ sudo chown root:root file2.txt $ ls -l total 16 -rw-r--r-- 1 pi pi 5 Apr 23 15:23 file1.txt -rwxr--r-- 1 root root 5 Apr 24 08:08 file2.txt -rw-r--r-- 1 pi pi 5 Apr 23 15:23 file3.txt drwxr-xr-x 2 pi pi 4096 Apr 23 15:23 mydir

See Also

For background on file permissions, see Recipe 3.12.

Also see Recipe 3.13 for changing file permissions.

3.15 Making a Screen Capture

Solution

Install and use the delightfully named scrot screen capture software.

Discussion

To install scrot, run the following command from Terminal:

$ sudo apt-get install scrot

The simplest way to trigger a screen capture is to just enter the command scrot. This will immediately take an image of the primary display and save it in a file named something like 2013-04-25-080116_1024x768_scrot.png within the current directory.

Sometimes you want a screenshot to show a menu being opened or something that generally disappears when the window in which you are interested loses focus. For such situations, you can specify a delay before the capture takes place using the -d option.

$ scrot -d 5

The delay is specified in seconds.

If you capture the whole screen, you can crop it later with image editing software, such as Gimp (Recipe 4.11). However, it is more convenient to just capture an area of the screen in the first place, which you can do using the -s option.

To use this option, type this command and then drag out the area of screen that you want to capture with the mouse.

$ scrot -s

The filename will include the dimensions in pixels of the image captured.

See Also

The scrot command has a number of other options to control things like using multiple screens and changing the format of the saved file. You can find out more about scrot from its manpage by entering the following command.

$ man scrot

For more information on installing with apt-get, see Recipe 3.16.

3.16 Installing Software with apt-get

Solution

The most frequently used tool for installing software from a Terminal session is apt-get.

The basic format of the command, which you must run as a superuser, is:

$ sudo apt-get install <name of software>

For example, to install the AbiWord word processing software, you would enter the command:

$ sudo apt-get install abiword

Discussion

The apt-get package manager uses a list of available software. This list is included with the Raspberry Pi operating system distribution that you use but is likely to be out-of-date. So if the software that you try to install is reported by apt-get as not found, run the following command to update the list:

$ sudo apt-get update

The list and the software packages for installation are all on the Internet, so none of this will work unless your Raspberry Pi has an Internet connection.

Tip

If you find that when you update, you get an error like E: Problem with MergeList /var/lib/dpkg/status, try running these commands:

sudo rm /var/lib/dpkg/status sudo touch /var/lib/dpkg/status

The installation process can often take a while because the files have to be downloaded and installed. Some installations will also add shortcuts to your desktop, or the program groups on your Start menu.

You can search for software to install using the command apt-get search followed by a search string such as abiword. This will then display a list of matching packages that you could install.

See Also

See Recipe 3.17 for removing programs that you no longer need so that you can free up space.

See also Recipe 3.20 for downloading source code from GitHub.

3.17 Removing Software Installed with apt-get

Solution

The apt-get utility has an option (remove) that will remove a package, but it will only remove packages that have been installed with apt-get install.

For example, if you wanted to remove AbiWord, you would use the command:

$ sudo apt-get remove abiword

Discussion

Removing a package like this does not always delete everything, as packages often also have prerequisite packages that are installed as well. To remove these, you can use the autoremove option, as shown here:

$ sudo apt-get autoremove abiword $ sudo apt-get clean

The apt-get clean option will do some further tidying up of unused package installation files.

See Also

See Recipe 3.16 for installing packages using apt-get.

3.18 Installing Python Packages with Pip

Solution

If you have the latest version of Raspbian, then pip will already be installed and you can run pip from the command line as shown in the example here, which is taken from Recipe 8.1 where it is used to install the Python library svgwrite.

$ sudo pip install svgwrite

If pip is not installed on your system, then you can install it by using the commands:

$ sudo apt-get install python-pip

Discussion

Although many Python libraries can be installed using apt-get (see Recipe 3.16), some cannot and you must use pip.

See Also

To install software using apt-get, see Recipe 3.16.

3.19 Fetching Files from the Command Line

Solution

Use the wget command to fetch a file from the Internet.

For example:

$ wget http://www.icrobotics.co.uk/wiki/images/c/c3/Pifm.tar.gz --2013-06-07 07:35:01-- http://www.icrobotics.co.uk/wiki/images/c/c3/Pifm.tar.gz Resolving www.icrobotics.co.uk (www.icrobotics.co.uk)... 155.198.3.147 Connecting to www.icrobotics.co.uk (www.icrobotics.co.uk)|155.198.3.147| :80... connected. HTTP request sent, awaiting response... 200 OK Length: 5521400 (5.3M) [application/x-gzip] Saving to: `Pifm.tar.gz' 100%[==================================================>] 5,521,400 601K/s 2013-06-07 07:35:11 (601 KB/s) - `Pifm.tar.gz' saved [5521400/5521400]

If your URL contains any special characters, it is a good idea to enclose it in double quotes. This example URL is from Recipe 4.10.

Discussion

You will find instructions for installing software that rely on using wget to fetch files. It is often more convenient to do this from the command line rather than use a browser, find the file, download it, and then copy it to the place you need it.

The wget command takes the URL to download as its argument and downloads it into the current directory. It’s typically used to download an archive file of some type but will also download any web page.

See Also

For more information on installing with apt-get, see Recipe 3.16.

For information on selecting and using a browser, see Recipe 4.3.

3.20 Fetching Source Code with Git

Solution

To use code in Git repositories, you need to use the git clone command to fetch the files.

Discussion

For example, the following command will fetch all the source code examples from this book:

$ git clone https://github.com/simonmonk/raspberrypi_cookbook_ed2.git

3.21 Running a Program or Script Automatically on Startup

Solution

Modify your rc.local file to run the program you want.

Edit the file /etc/rc.local by using the command:

$ sudo nano /etc/rc.local

Add the following line after the first block of comment lines that begin with #:

$ /usr/bin/python /home/pi/my_program.py &

It is important to include the & on the end of the command line so that it is run in the background; otherwise, your Raspberry Pi will not boot.

Discussion

This way of autorunning a program needs a very careful edit of rc.local, or you may stop your Raspberry Pi from booting.

See Also

A safer way of autorunning a program is detailed in Recipe 3.22.

3.22 Running a Program or Script Automatically as a Service

Solution

Debian Linux, upon which most Raspberry Pi distributions are based, uses a dependency-based mechanism for automating the running of commands at startup. This is a little tricky to use and involves creating a configuration file for the script or program that you want to run in a folder called init.d.

Discussion

The following example shows you how to run a Python script in your home directory. The script could do anything, but in this case, the script runs a simple Python web server, which is described further in Recipe 7.17.

The steps involved in this are:

-

Create an init script.

-

Make the init script executable.

-

Tell the system about the new init script.

First, create the init script. This needs to be created in the folder /etc/init.d/. The script can be called anything, but in this example, you will call it my_server.

Create the new file by using nano with the following command:

$ sudo nano /etc/init.d/my_server

Paste the following code into the editor window and save the file:

### BEGIN INIT INFO# Provides: my_server# Required-Start: $remote_fs $syslog $network# Required-Stop: $remote_fs $syslog $network# Default-Start: 2 3 4 5# Default-Stop: 0 1 6# Short-Description: Simple Web Server# Description: Simple Web Server### END INIT INFO#! /bin/sh# /etc/init.d/my_serverexportHOMEcase"$1"in start)echo"Starting My Server"sudo /usr/bin/python /home/pi/myserver.py 2>&1&;;stop)echo"Stopping My Server"PID=`ps auxwww|grep myserver.py|head -1|awk'{print $2}'`kill-9$PID;;*)echo"Usage: /etc/init.d/my_server {start|stop}"exit1;;esacexit0

This is quite a lot of work to automate the running of a script, but most of it is boiler-plate code. To run a different script, just work your way through the script, changing the descriptions and the name of the Python file you want to run.

The next step is to make this file executable for the owner, which you do using this command:

$ sudo chmod +x /etc/init.d/my_server

Now that the program is set up as a service, you can test that everything is OK before you set it to autostart as part of the boot sequence, using the following command:

$ /etc/init.d/my_server start Starting My Server Bottle v0.11.4 server starting up (using WSGIRefServer())... Listening on http://192.168.1.16:80/ Hit Ctrl-C to quit.

Finally, if that runs OK, use the following command to make the system aware of the new service that you have defined:

$ sudo update-rc.d my_server defaults

See Also

For a simpler approach to making a program run automatically, see Recipe 3.21.

For more information on changing file and folder permissions, see Recipe 3.12.

3.23 Running a Program or Script Automatically at Regular Intervals

Solution

Use the Linux crontab command.

To do this, the Raspberry Pi needs to know the time and date, and therefore needs a network connection or a real-time clock. See Recipe 12.13.

Discussion

The command crontab allows you to schedule events to take place at regular intervals. This can be daily or hourly, and you can even define complicated patterns so different things happen on different days of the week. This is useful for backup tasks that you might want to run in the middle of the night.

You can edit the scheduled events by using the following command:

$ crontab -e

If the script or program that you want to run needs to be run by a superuser, then prefix all the crontab commands with sudo (Recipe 3.11).

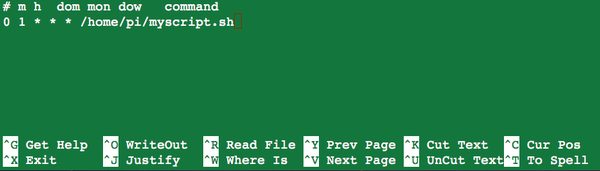

The comment line indicates the format of a crontab line. The digits are, in order, minute, hour, day of month, month, day of week, and then the command that you want to run.

The first line that starts with a # is just a comment line to remind you of the format for a crontab line.

If there is a * in the digit position, that means every; if there is a number there instead, the script will only be run at that minute/hour/day of the month.

So, to run the script every day at 1 a.m., you would add the line shown in Figure 3-7.

Figure 3-7. Editing crontab

Using only a single digit, you can specify ranges to run the script just on weekdays; for example:

0 1 * * 1-5 /home/pi/myscript.sh

If your script needs to be run from a particular directory, you can use a semicolon (;) to separate multiple commands as shown here:

0 1 * * * cd /home/pi; python mypythoncode.py

See Also

You can see the full documentation for crontab by entering this command:

$ man crontab

3.24 Finding Things

Discussion

Starting with a directory specified in the command, the find command will search, and if it finds the file, display its location. For example:

$ find /home/pi -name gemgem.py /home/pi/python_games/gemgem.py

You can start the search higher up the tree, even at the root of the whole filesystem (/). This will make the search take a lot longer, and will also produce error messages. You can redirect these error messages by adding 2>/dev/null to the end of the line.

To search for the file throughout the entire filesystem, use the following command:

$ find / -name gemgem.py 2>/dev/null /home/pi/python_games/gemgem.py

You can also use wildcards with find as follows:

$ find /home/pi -name match* /home/pi/python_games/match4.wav /home/pi/python_games/match2.wav /home/pi/python_games/match1.wav /home/pi/python_games/match3.wav /home/pi/python_games/match0.wav /home/pi/python_games/match5.wav

See Also

The find command has a number of other advanced features for searching. To see the full manpage documentation for find, use this command:

$ man find

3.25 Using the Command-Line History

Solution

Use the up and down arrow keys to select previous commands from the command history, and the history command with grep to find older commands.

Discussion

You can access the previous command you ran by pressing the up arrow key. Pressing it again will take you to the command before that, and so on. If you overshoot the command you wanted, the down arrow key will take you back in the other direction.

If you want to cancel without running the selected command, use Ctrl-C.

Over time, your command history will grow too large to find a command that you used ages ago. To find a command from way back, you can use the history command.

$ history

1 sudo nano /etc/init.d/my_server

2 sudo chmod +x /etc/init.d/my_server

3 /etc/init.d/my_server start

4 cp /media/4954-5EF7/sales_log/server.py myserver.py

5 /etc/init.d/my_server start

6 sudo apt-get update

7 sudo apt-get install bottle

8 sudo apt-get install python-bottle

This lists all your command history and is likely to have far too many entries for you to find the one you want. To remedy this, you can pipe the history command into the grep command, which will just display results matching a search string. So, for example, to find all the apt-get (Recipe 3.16) commands that you’ve issued, you can use the line:

$ history | grep apt-get

6 sudo apt-get update

7 sudo apt-get install bottle

8 sudo apt-get install python-bottle

55 history | grep apt-get

Each history item has a number next to it, so if you find the line you were looking for, you can run it using ! followed by the history number, as shown here:

$ !6 sudo apt-get update Hit http://mirrordirector.raspbian.org wheezy InRelease Hit http://mirrordirector.raspbian.org wheezy/main armhf Packages Hit http://mirrordirector.raspbian.org wheezy/contrib armhf Packages .....

See Also

To find files rather than commands, see Recipe 3.24.

3.26 Monitoring Processor Activity

Solution

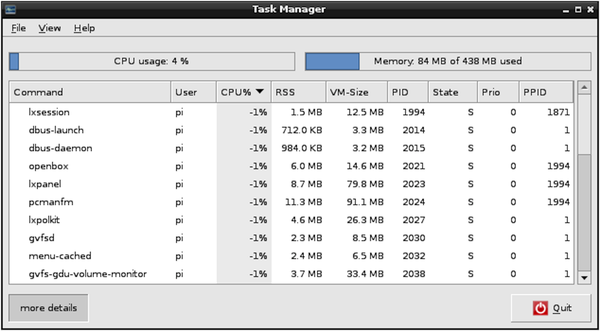

Use the Task Manager utility, which you’ll find on the Start menu in the System Tools program group (Figure 3-8).

Figure 3-8. The Task Manager

The Task Manager allows you to see at a glance how much CPU and memory are being used. You can also right-click on a process and select the option to kill it from the pop-up menu.

The graphs at the top of the window display the total CPU usage and memory. The processes are listed below that, and you can see the CPU share each is taking.

Discussion

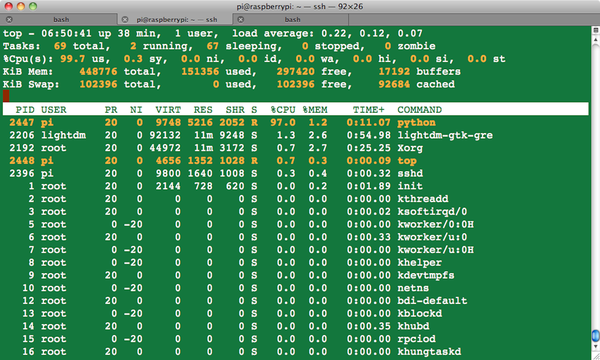

If you prefer to do this type of thing from the command line, use the Linux top command to display very similar data about processor and memory and which processes are using the most resources (Figure 3-9). You can then use the kill command to kill a process. You will need to do this as superuser.

In this case, you can see that the top process is a Python program that uses 97% of CPU. The first column shows its process ID (2447). To kill this process, enter this command:

$ kill 2447

It is quite possible to kill some vital operating system process this way, but if you do, powering off your Pi and turning it back on again will restore things to normal.

Figure 3-9. Using the top command to see resource usage

Sometimes, you may have a process running that is not immediately visible when you use top. If this is the case, you can search all the processes running by using the ps command and piping (Recipe 3.31) the results to the grep command, which will search the results and highlight items of interest.

For example, to find the process ID for our CPU-hogging Python process, we could run the following command:

$ ps -ef | grep "python" pi 2447 2397 99 07:01 pts/0 00:00:02 python speed.py pi 2456 2397 0 07:01 pts/0 00:00:00 grep --color=auto python

In this case, the process ID for the Python program speed.py is 2447. The second entry in the list is the process for the ps command itself.

A variation on the kill command is the killall command. Use this with caution, as it kills all processes that match its argument. So, for example, the following command will kill all Python programs running on the Raspberry Pi:

$ sudo killall python

See Also

See also the manpages for top, ps, grep, kill, and killall. You can view these by typing man followed by the name of the command, as shown here:

$ man top

3.27 Working with File Archives

Discussion

If the file that you want to uncompress just has the extension .gz, you can unzip it using the command:

$ gunzip myfile.gz

You also often find files (called tarballs) that contain a directory that has been archived with the Linux tar utility and then compressed with gzip into a file with a name like myfile.tar.gz.

You can extract the original files and folders out of a tarball by using the tar command:

$ tar -xzf myfile.tar.gz

See Also

You can find out more about tar from the manpages, which you can access by using the command man tar.

3.28 Listing Connected USB Devices

Solution

Use the lsusb command. This will list all the devices attached to the USB ports on your Raspberry Pi:

$ lsusb Bus 001 Device 002: ID 0424:9512 Standard Microsystems Corp. Bus 001 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0002 Linux Foundation 2.0 root hub Bus 001 Device 003: ID 0424:ec00 Standard Microsystems Corp. Bus 001 Device 004: ID 15d9:0a41 Trust International B.V. MI-2540D [Optical mouse]

Discussion

This command will tell you whether a device is connected or not, but it will not guarantee that it is working correctly. There may be drivers to install or configuration changes to make for the hardware.

See Also

For an example of using lsusb when attaching an external webcam, see Recipe 4.5.

3.29 Redirecting Output from the Command Line to a File

Solution

Use the > command to redirect output that would otherwise appear on the command line.

For example, to copy a directory listing into a file called myfiles.txt, do the following:

$ ls > myfiles.txt $ more myfiles.txt Desktop indiecity master.zip mcpi

Discussion

You can use the > command on any Linux command that produces output, even if you are running, say, a Python program.

You can also use the opposite (<) command to redirect user input, although this is not nearly as useful as >.

See Also

To use cat to join together a number of files, see Recipe 3.30.

3.30 Concatenating Files

Discussion

Joining files is the real purpose of the cat command. You can supply as many filenames as you like, and they will all be written to the file you direct to. If you do not redirect the output, then it will just appear in your Terminal window. If they are big files, this might take some time!

See Also

See also Recipe 3.7, where cat is used to display the contents of a file.

3.31 Using Pipes

Solution

Use the pipe command, which is the bar symbol (|) on your keyboard, to pipe the output of one command to another. For example:

$ ls -l *.py | grep Jun -rw-r--r-- 1 pi pi 226 Jun 7 06:49 speed.py

This example will find all the files with the extension py that also have Jun in their directory listing, indicating that they were last modified in June.

Discussion

At first sight, this looks rather like output redirection using > (Recipe 3.29). The difference is that +>_ will not work where the target is another program. It will only work for redirecting to a file.

You can chain together as many programs as you like, as shown here, although this isn’t something you will do often:

$ command1 | command2 | command3

See Also

See Recipe 3.26 for an example of using grep to find a process, and Recipe 3.25 to search your command history, using a pipe and grep.

3.32 Hiding Output to the Terminal

Solution

Redirect the output to /dev/null using >.

For example:

$ ls > /dev/null

Discussion

This example illustrates the syntax but is otherwise pretty useless. A more common use is where you’re running a program and the developer has left a lot of trace messages in her code, which you don’t really want to see. The following example hides superfluous output from the find command (see Recipe 3.34).

$ find / -name gemgem.py 2>/dev/null /home/pi/python_games/gemgem.py

See Also

For more information about redirecting standard output, see Recipe 3.29.

3.33 Running Programs in the Background

Solution

Run the program or command in the background using the & command.

For example:

$ python speed.py & [1] 2528 $ ls

Rather than wait until the program has finished running, the command line displays the process ID (the second number) and immediately allows you to continue with whatever other commands you want to run. You can then use this process ID to kill the background process (Recipe 3.26).

To bring the background process back to the foreground, use the fg command:

$ fg python speed.py

This will report the command or program that is running and then wait for it to finish.

Discussion

Output from the background process will still appear in the Terminal.

An alternative to putting processes in the background is to just open more than one Terminal window.

See Also

For information on managing processes, see Recipe 3.26.

3.34 Creating Command Aliases

Solution

Edit the file ~/.bashrc using nano (Recipe 3.6), and then move to the end of the file and add as many lines as you want, like this:

alias l='ls -a'

This creates an alias called l that, when entered, will be interpreted as the command ls -a.

Save and exit the file using Ctrl-X and Ctrl-Y, and then to update the Terminal with the new alias, type the following command:

$ source .bashrc

Discussion

Many Linux users set up an alias for rm like the following, so that it confirms deletions.

$ alias rm='rm -i'

This is not a bad idea, as long as you do not forget when you use someone else’s system that doesn’t have this alias set up!

See Also

For more information about rm, see Recipe 3.10.

3.35 Setting the Date and Time

Solution

Use the Linux date command.

The date and time format is MMDDHHMMYYYY, where MM is the month number, DD is the day of the month, HH and MM are the hours and minutes, respectively, and YYYY is the year.

For example:

$ sudo date 010203042013 Wed Jan 2 03:04:00 UTC 2013

Discussion

If the Raspberry Pi is connected to the Internet, then as it boots up it will automatically set its own time using an Internet time server.

You can also use date to display the UTC time by just entering date on its own:

$ date Wed Jan 2 03:08:14 UTC 2013

See Also

If you want your Raspberry Pi to maintain the correct time even when there is no network, then you can use a real-time clock (RTC) module (Recipe 12.13).

3.36 Finding Out How Much Room You Have on the SD Card

Solution

Use the Linux df command:

$ df -h Filesystem Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on rootfs 3.6G 1.7G 1.9G 48% / /dev/root 3.6G 1.7G 1.9G 48% / devtmpfs 180M 0 180M 0% /dev tmpfs 38M 236K 38M 1% /run tmpfs 5.0M 0 5.0M 0% /run/lock tmpfs 75M 0 75M 0% /run/shm /dev/mmcblk0p1 56M 19M 38M 34% /boot