Chapter 17

Additional Programming Examples

This chapter presents programming examples from topics presented in previous chapters in the book. The programming designs are accomplished using assembly language only and also using assembly language modules embedded in C programs. Each example shows the outputs obtained from executing the program. There are numerous examples designed in the text and also numerous programs to be designed in the problem set at the end of the chapter.

17.1 Programming Examples

The various topics that will be covered in the examples include: logic instructions, bit test instructions, compare instructions, unconditional and conditional jump instructions, unconditional and conditional loop instructions, fixed-point instructions, floating-point instructions, string instructions, and arrays. The problem set includes the above instructions plus additional select instructions.

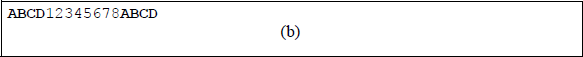

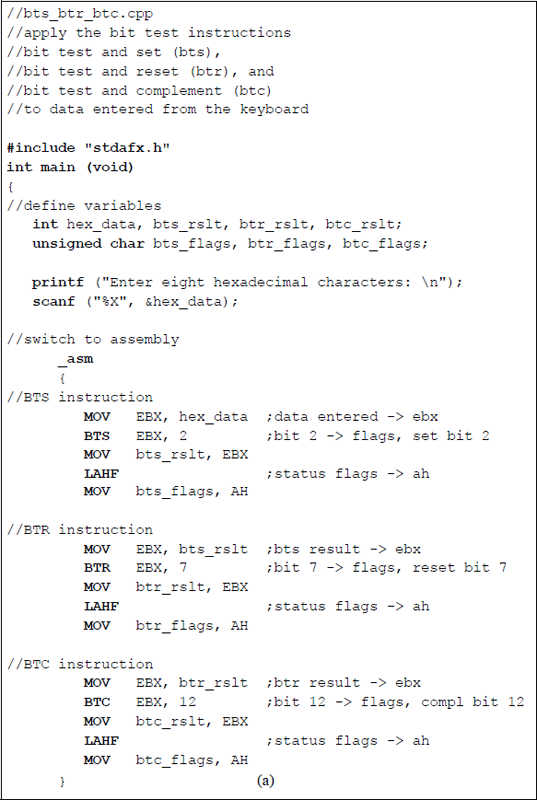

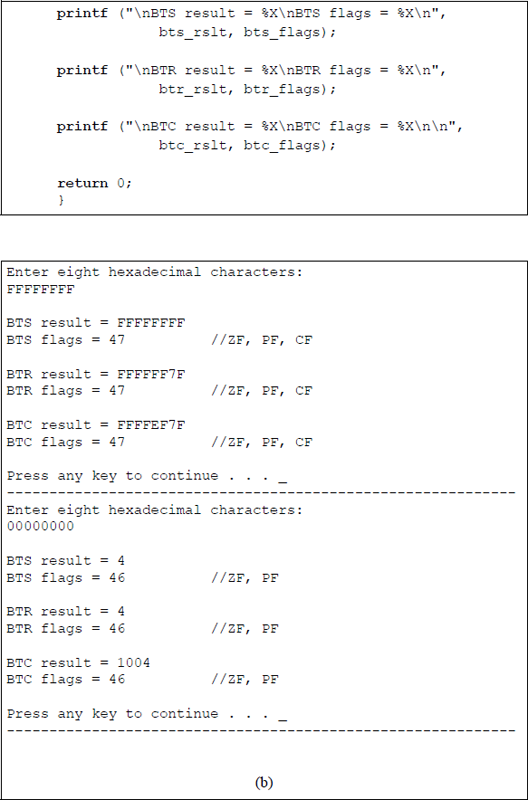

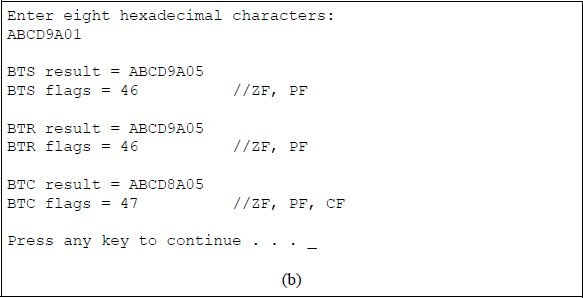

Example 17.1 This example uses the following instructions: the bit test instructions bit test and set (BTS), bit test and reset (BTR), and bit test and complement (BTC). These instructions are used in conjunction with the load status flags into AH register (LAHF) instruction and the move (MOV) instruction. The program is designed using an assembly language module embedded in a C program. Figure 17.1(a) shows the program. Figure 17.1(b) shows the outputs.

Program illustrating the use of bit test instructions: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

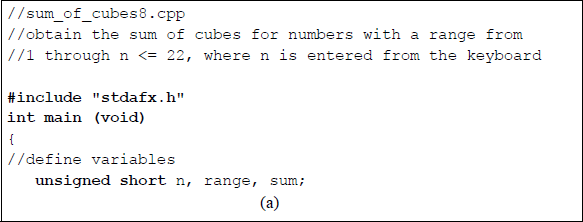

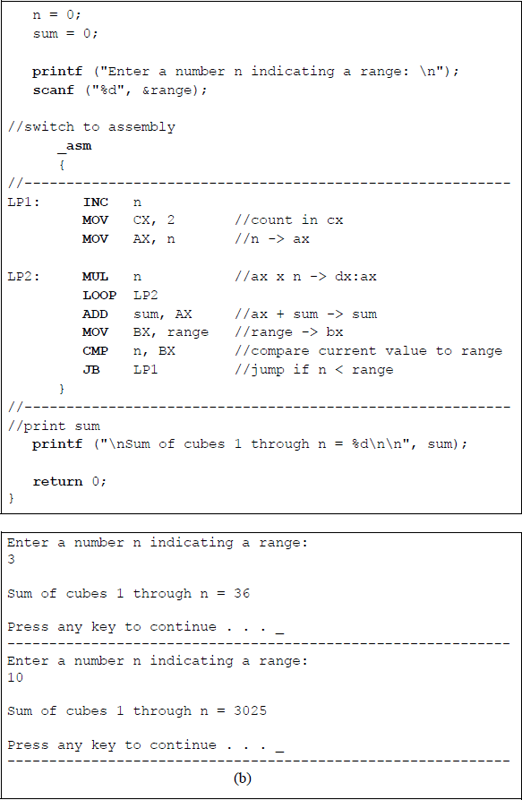

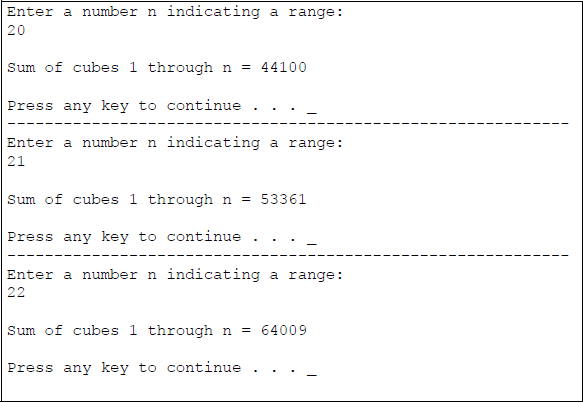

Example 17.2 This example calculates the sum of cubes for numbers in the following range: 1 to n, where n is ≤ 22. The range number is entered from the keyboard. The sum of cubes can be obtained from any of the expressions shown in Equation 17.1. The three expressions will be used in Examples 17.2, Example 17.3, and Example 17.4, respectively. This example uses the first expression listed using an assembly language module embedded in a C program, as shown in Figure 17.2.

Program to calculate the sum of cubes in the range from 1 to ≤ 22: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

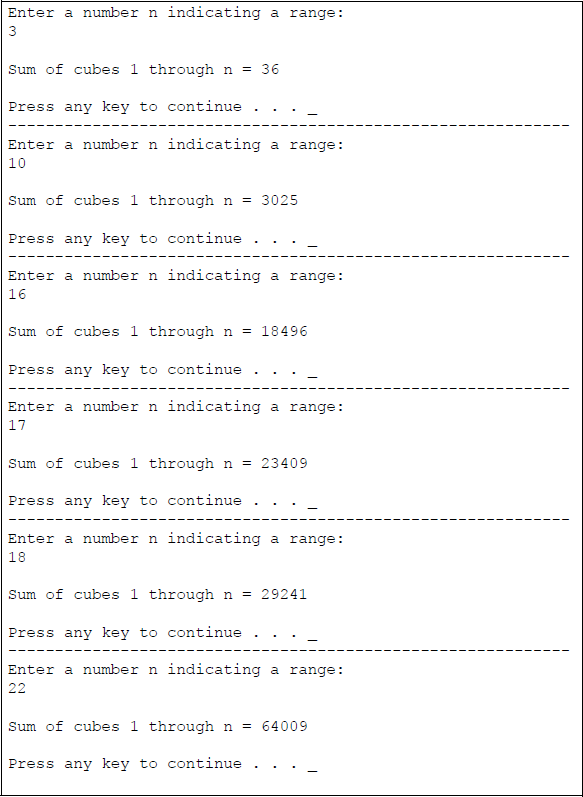

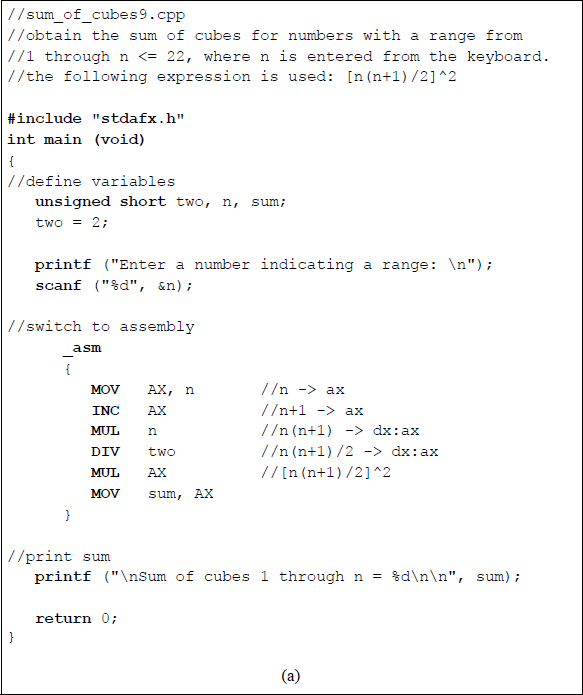

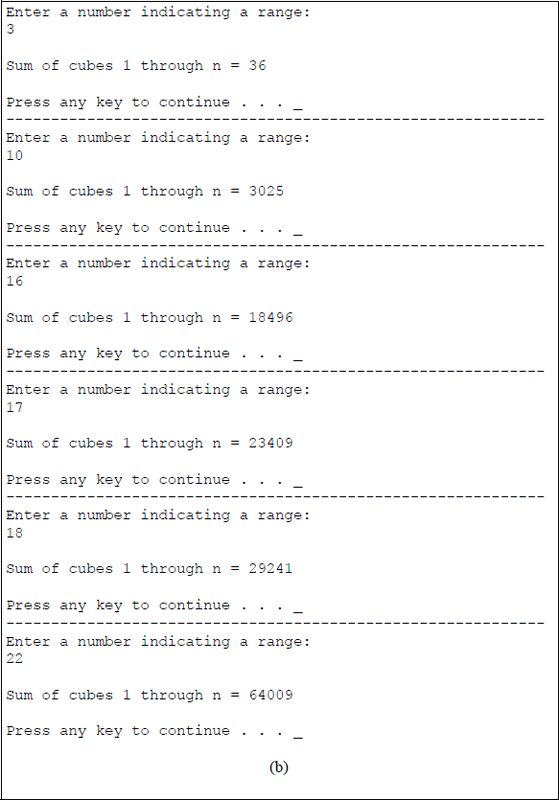

Example 17.3 This example calculates the sum of cubes for numbers in the following range: 1 to n, where n is ≤ 22. The range number is entered from the keyboard. The sum of cubes for this example is obtained from second expression listed in Equation 17.1 and shown below. This example uses an assembly language module embedded in a C program, as shown in Figure 17.3.

Program to calculate the sum of cubes in the range from 1 to ≤ 22 using the expression shown above: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

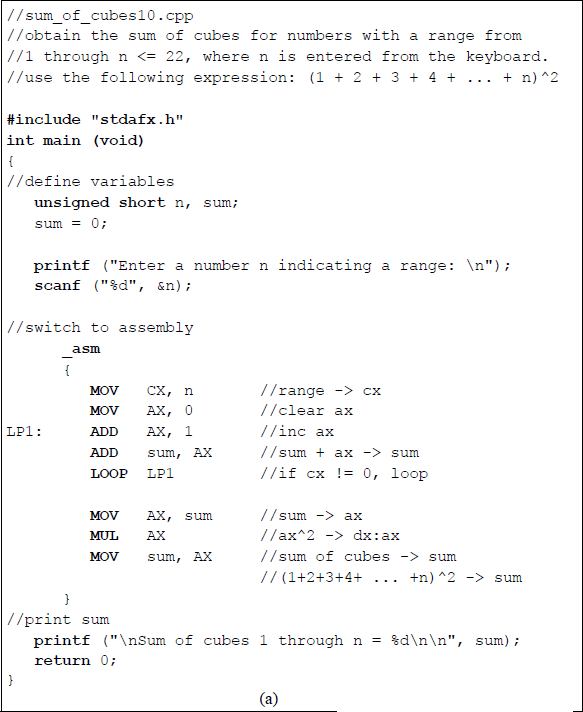

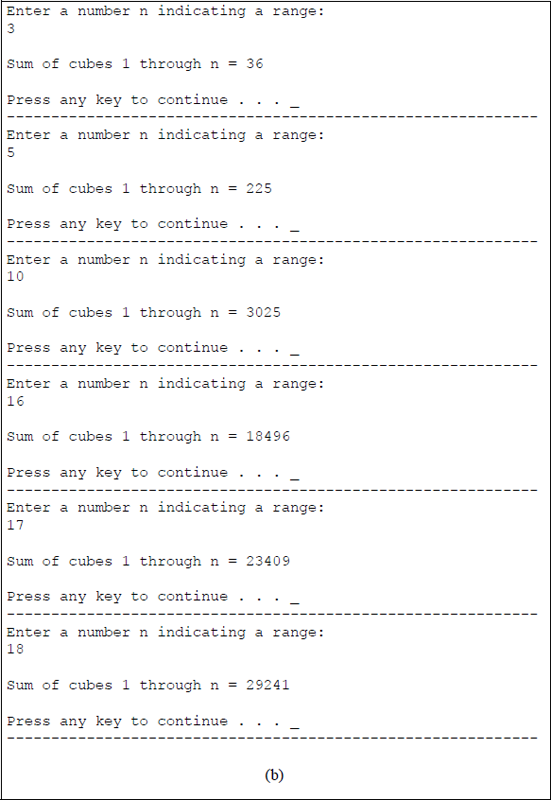

Example 17.4 This example calculates the sum of cubes for numbers in the following range: 1 to n, where n is ≤ 22. The range number is entered from the keyboard. The sum of cubes for this example is obtained from third expression listed in Equation 17.1 and shown below. This example uses an assembly language module embedded in a C program, as shown in Figure 17.4.

Program to calculate the sum of cubes in the range from 1 to ≤ 22 using the expression shown above: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

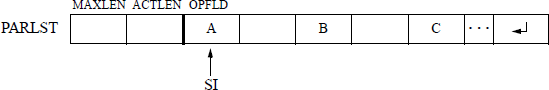

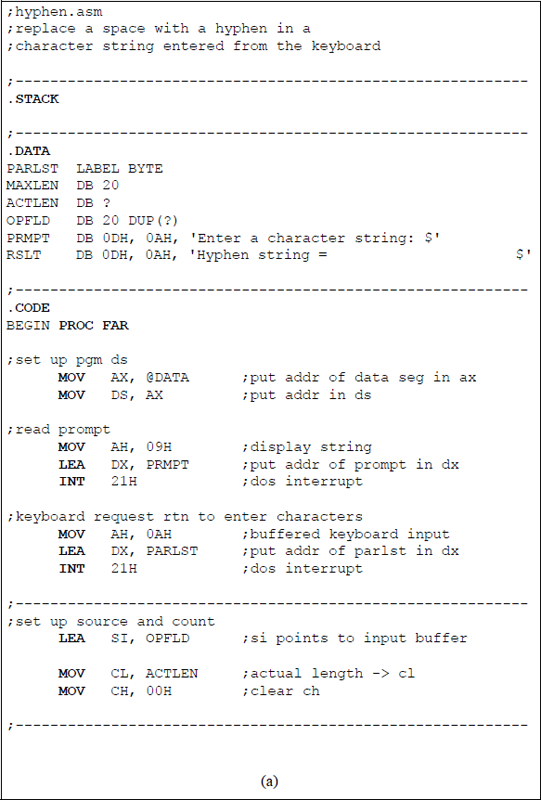

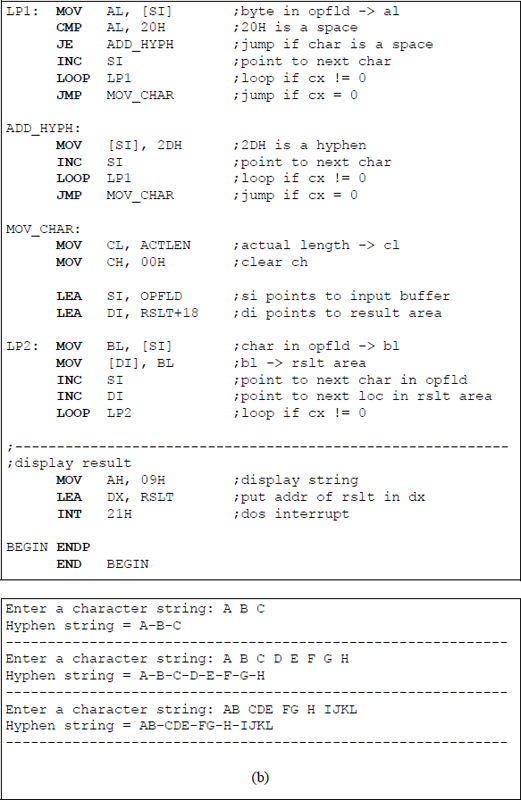

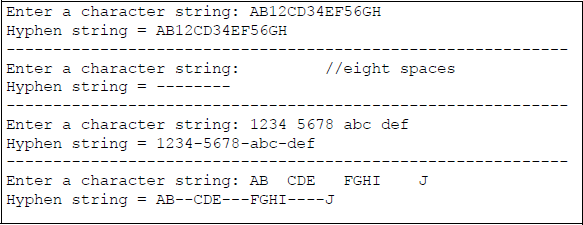

Example 17.5 This example replaces all spaces with hyphens in a character string that is entered from the keyboard. The character string is stored in the operand field (OPFLD) of the parameter list (PARLST). The parameter list is reproduced in Figure 17.5 for convenience and illustrates an example for this program. The program in this example uses an assembly language program — not embedded in a C program — as shown in Figure 17.6. This program does not use the MOVSB string instruction — the same program using the MOVSB instruction is left as a problem at the end of the chapter. The comments at the end of each line of code in Figure 17.6 explain the operation of that individual line.

Program to replace spaces with hyphens in a character string that is entered from the keyboard: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

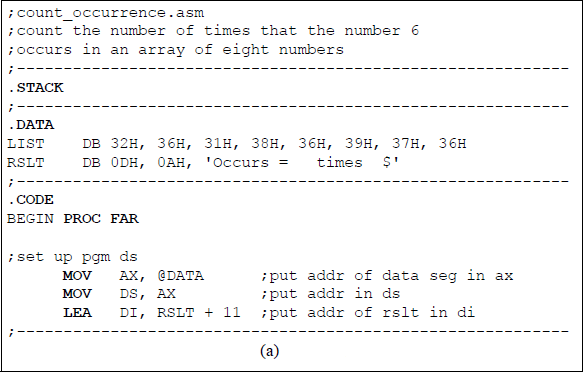

Example 17.6 This example counts the number of times that the integer 6 occurs in an array of eight integers. The program in this example uses an assembly language program — not embedded in a C program — as shown in Figure 17.7. The array is defined in the data segment (.DATA) and is labelled LIST. The comments at the end of each line of code in Figure 17.7 explain the operation of that individual line. A similar program that uses data entered from the keyboard is left as a problem at the end of the chapter.

Program to count the number of times that the integer 6 occurs in an array of eight integers: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

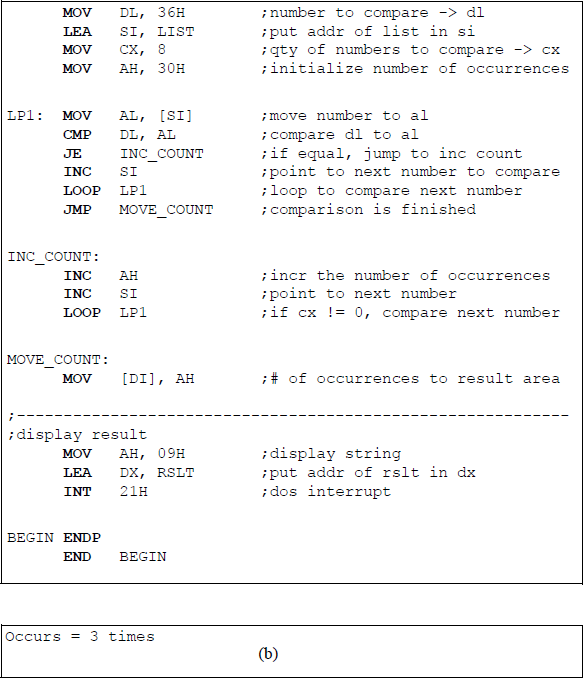

Example 17.7 This example determines the largest integer in an array of eight integers. The program in this example uses an assembly language program — not embedded in a C program — as shown in Figure 17.8. The array is defined in the data segment (.DATA) and is labelled LIST. The comments at the end of each line of code in Figure 17.8 explain the operation of that individual line. A similar program that uses data entered from the keyboard is left as a problem at the end of the chapter.

Program to determine the largest integer in an array of eight integers: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

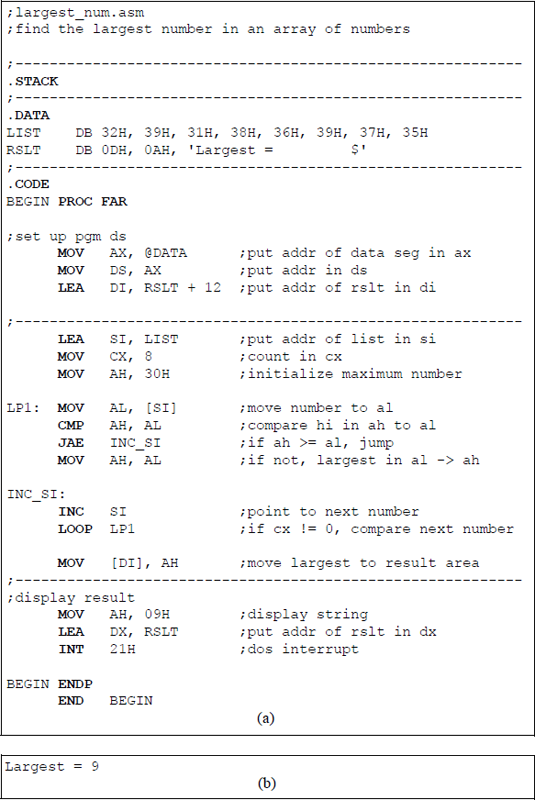

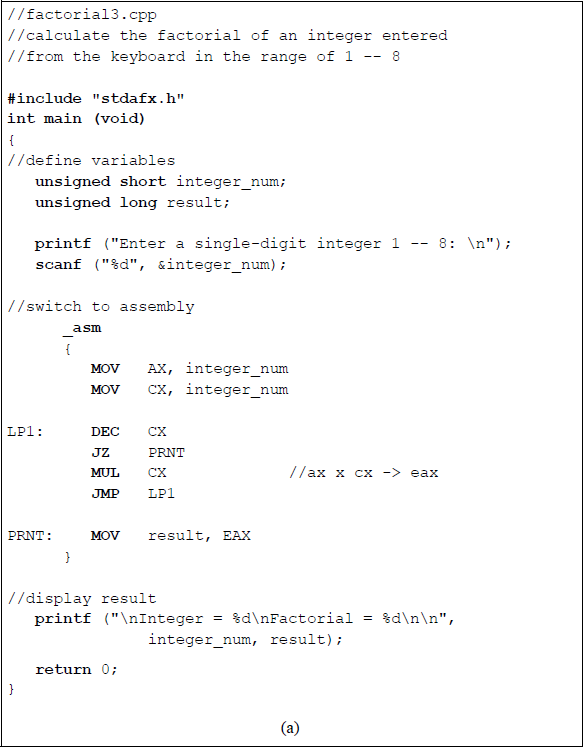

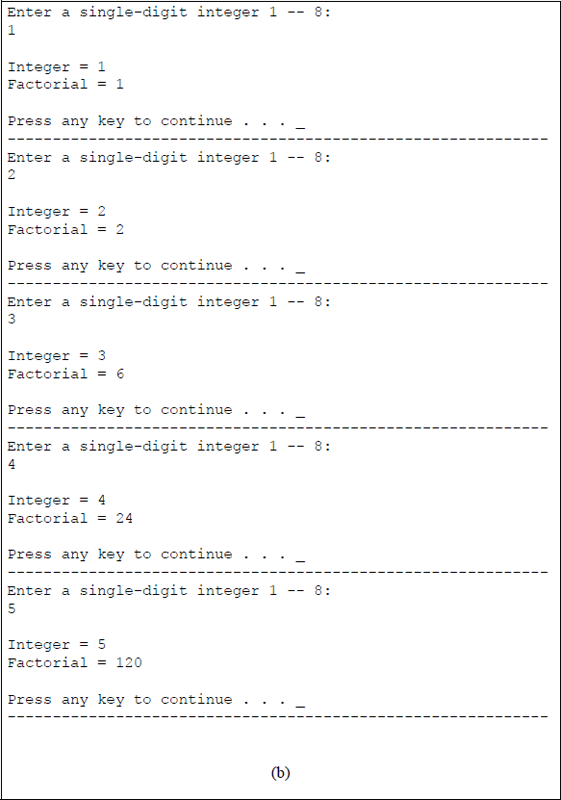

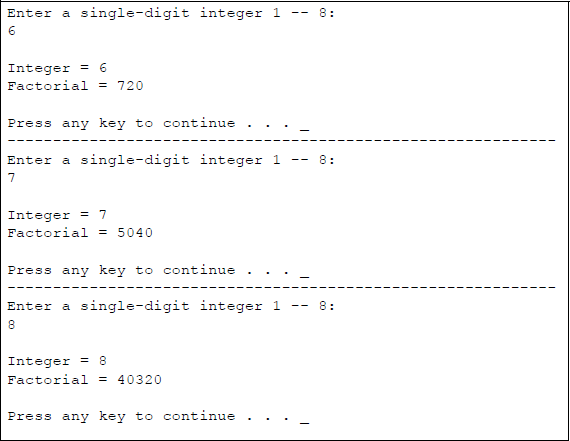

Example 17.8 This example calculates the factorial of single-digit integers in the range of 1 through 8 that are entered from the keyboard. The program in this example is designed using an assembly language module embedded in a C program, as shown in Figure 17.9. A similar program using assembly language only — that uses data entered from the keyboard — is left as a problem at the end of the chapter.

Program to calculate the factorial of single-digit integers that are entered from the keyboard: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

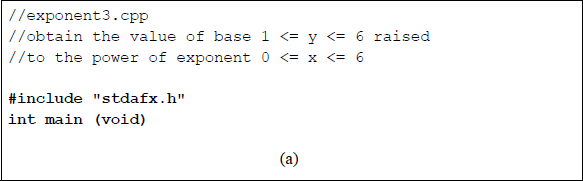

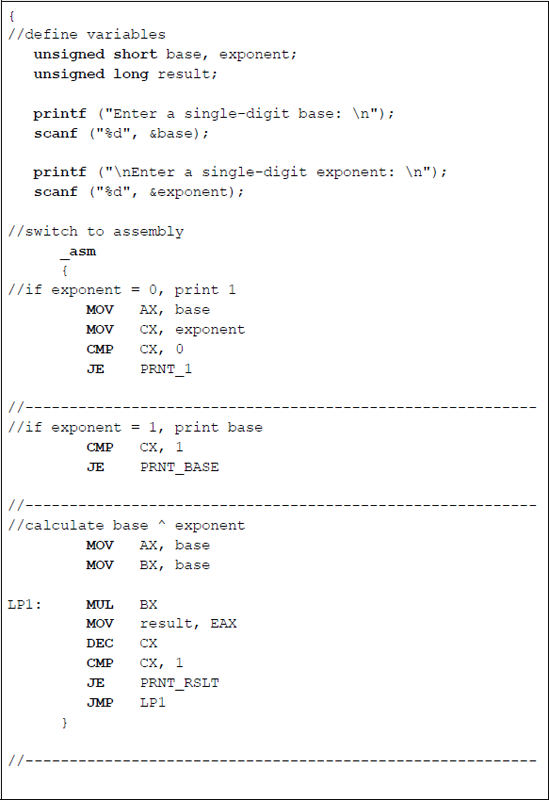

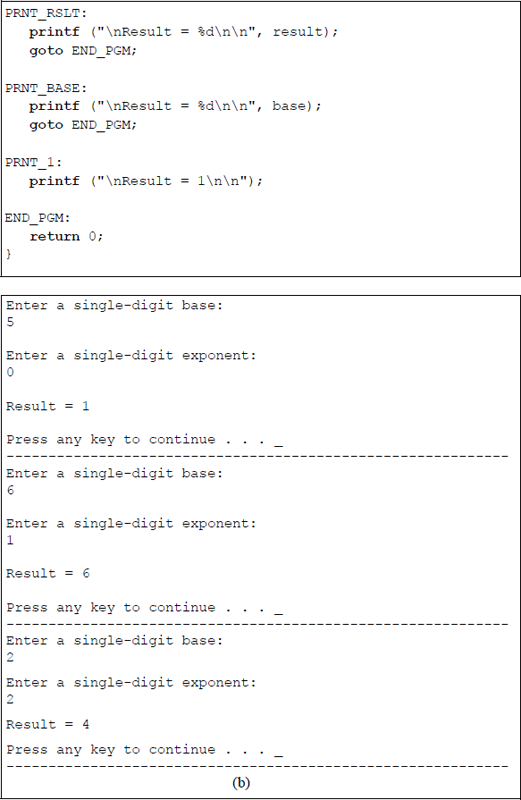

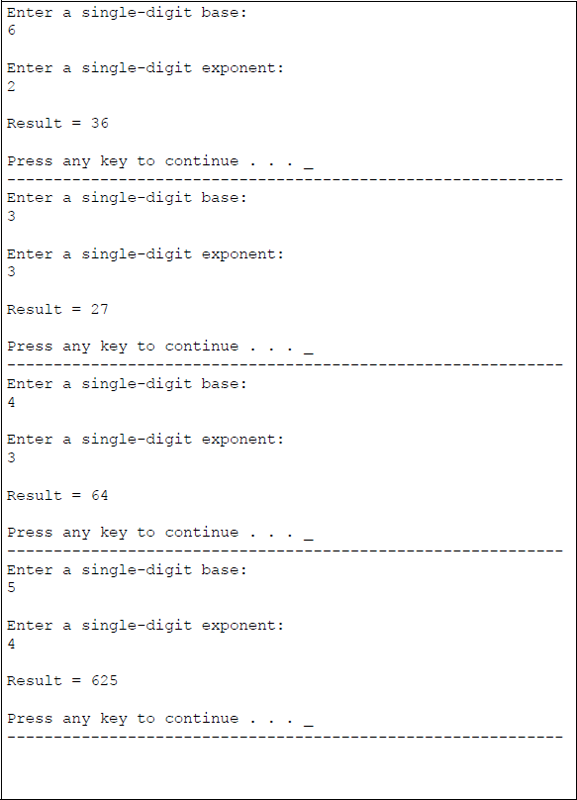

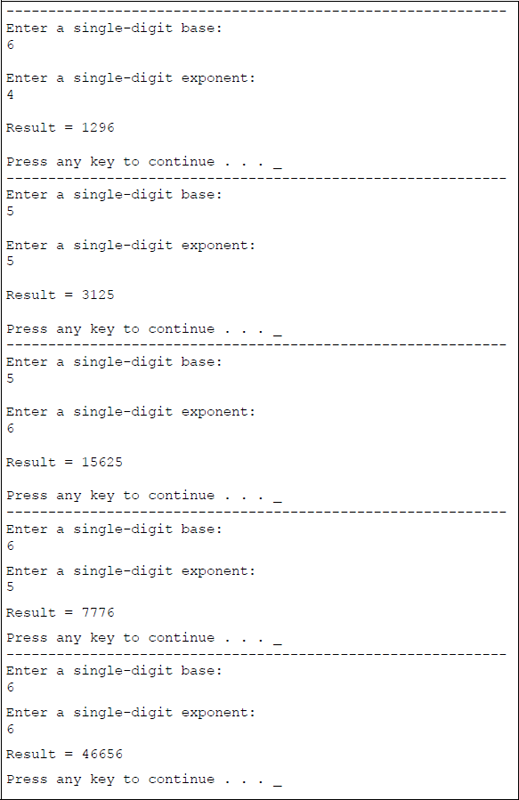

Example 17.9 This example calculates the value of single-digit integer bases in the range of 1 ≤ y ≤ 6 raised to the power of single-digit integer exponents in the range of 0 ≤ × ≤ 6 — bases and exponents are entered from the keyboard. The program in this example is designed using an assembly language module embedded in a C program, as shown in Figure 17.10.

Program to calculate single-digit bases raised to the power of single-digit exponents: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

Example 17.10 This example calculates the value of the following expression using integers for fixed-point arithmetic:

The program in this example is designed using an assembly language module embedded in a C program. Both the quotient and remainder will be obtained after the division operation is executed.

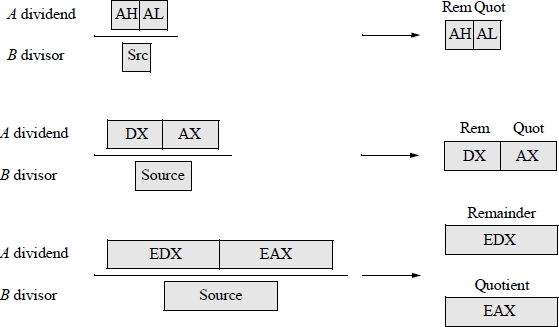

Recall that the DIV instruction divides the unsigned dividend in an implied general-purpose register by the unsigned divisor source operand in a register or memory location. The results are stored in the implied registers. The syntax for the DIV instruction is shown below.

DIV register/memory

The locations of the DIV operands are as follows: the dividend registers are AX, DX:AX, EDX:EAX, and RDX:RAX and the size of the corresponding divisors are 8 bits, 16 bits, 32 bits, and 64 bits, respectively; the resulting quotients are stored in registers AL, AX, EAX, and RAX, respectively; the resulting remainders are stored in registers AH, DX, EDX, and RDX, respectively. Results that are not integers are truncated to integers. Figure 17.11 illustrates pictorially the division operation.

An example is shown below using the following values for variables A, B, and C: A = 200, B = 200, and C = 1000, yielding a quotient of 207 and a remainder of 100.

A second example is shown below using the following values for variables A, B, and C: A = 790, B = 650, and C = 1500, yielding a quotient of 652 and a remainder of 420.

Figure 17.12 illustrates a program to calculate the given expression using the fixed-point arithmetic instructions of MUL, ADD, and DIV.

![Figure showing program to calculate the value of [(A × B) + C + 500] / A: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.](image/fig17_12a.png)

![Figure showing program to calculate the value of [(A × B) + C + 500] / A: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.](image/fig17_12b.png)

Program to calculate the value of [(A × B) + C + 500] / A: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

Example 17.11 This example calculates the value of the following expression using integers for fixed-point arithmetic:

This example is similar to Example 17.10, except that doublewords are used and only the quotient is obtained after the division operation is executed; therefore, all fractions are truncated. The program in this example is designed using an assembly language module embedded in a C program and is shown in Figure 17.13.

![Figure showing program to calculate the value of [(A × B) + C + 500] / A using doubleword operands to obtain the quotient only: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.](image/fig17_13a.png)

![Figure showing program to calculate the value of [(A × B) + C + 500] / A using doubleword operands to obtain the quotient only: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.](image/fig17_13b.png)

Program to calculate the value of [(A × B) + C + 500] / A using doubleword operands to obtain the quotient only: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

Example 17.12 This example calculates the value of the following expression using variables for floating-point arithmetic:

This example is similar to previous examples, except that floating-point operands are used and a floating-point quotient is obtained after the division operation is executed; therefore, all fractions are retained and are not truncated. The program in this example is designed using an assembly language module embedded in a C program.

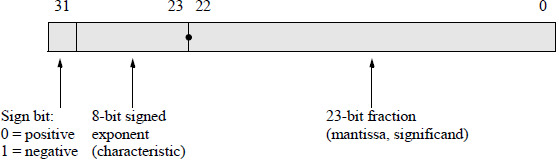

Recall that floating-point numbers consist of the following three fields: a sign bit, s; an exponent, e; and a fraction, f. These parts represent a number that is obtained by multiplying the fraction, f , by a radix, r, raised to the power of the exponent, e, as shown in Equation 17.2 for the number A, where f and e are signed fixed-point numbers, and r is the radix (or base).

Figure 17.14 shows the format for 32-bit single-precision floating-point numbers. The single-precision format consists of a sign bit that indicates the sign of the number, an 8-bit signed exponent, and a 23-bit unsigned fraction.

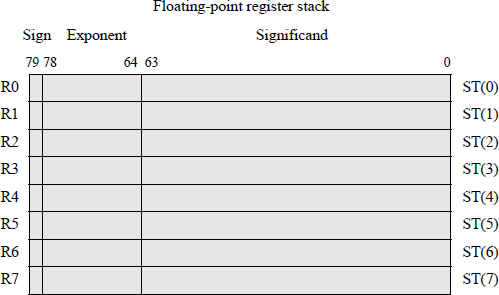

Figure 17.15 shows the eight data registers — called the register stack — used in the floating-point unit. The stack top, ST(0), is register R0 and, like a normal stack, builds towards lower-numbered registers. The register immediately below the stack top is referred to as ST(1); the register immediately below ST(1) is referred to as ST(2), etc.

When the stack is full; that is, the registers at ST(0) through the register at ST(7) contain valid data, a stack wraparound occurs if an attempt is made to store additional data on the stack. This results in a stack overflow because the unsaved data is overwritten. The stack registers are specified by three bits — 000 through 111 — to reference ST(0) through ST(7), respectively. Therefore, ST(i) references the ith register from the current stack top. Chapter 11 can be reviewed for more details on floatingpoint operations.

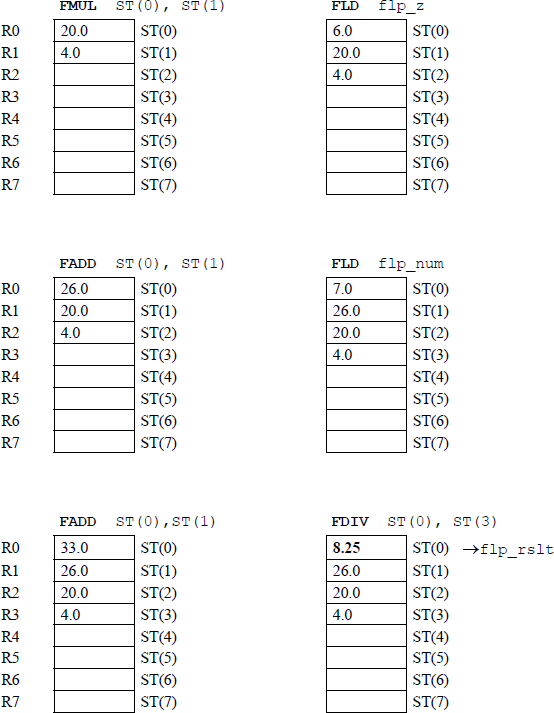

Figure 17.16 shows the assembly language module embedded in a C program to perform the calculations for the expression shown in Figure 17.16. Figure 17.17 shows the contents of the register stack during execution of the program for variables X, Y, Z, and a constant that are equal to 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, and 7.0, respectively.

![Figure showing program to perform calculations on [(X × Y) + Z + constant] / X: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.](image/fig17_16a.png)

![Figure showing program to perform calculations on [(X × Y) + Z + constant] / X: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.](image/fig17_16b.png)

![Figure showing program to perform calculations on [(X × Y) + Z + constant] / X: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.](image/fig17_16c.png)

Program to perform calculations on [(X × Y) + Z + constant] / X: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

Assume that instructions FLD flp_x and FLD flp_y have been executed.

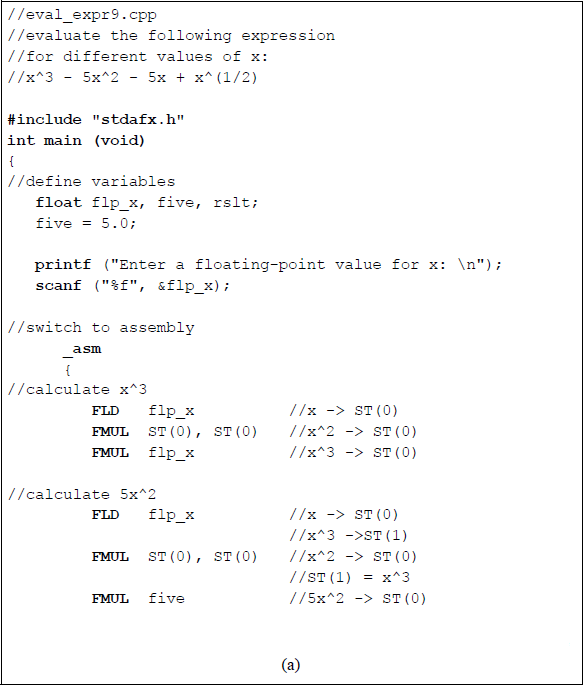

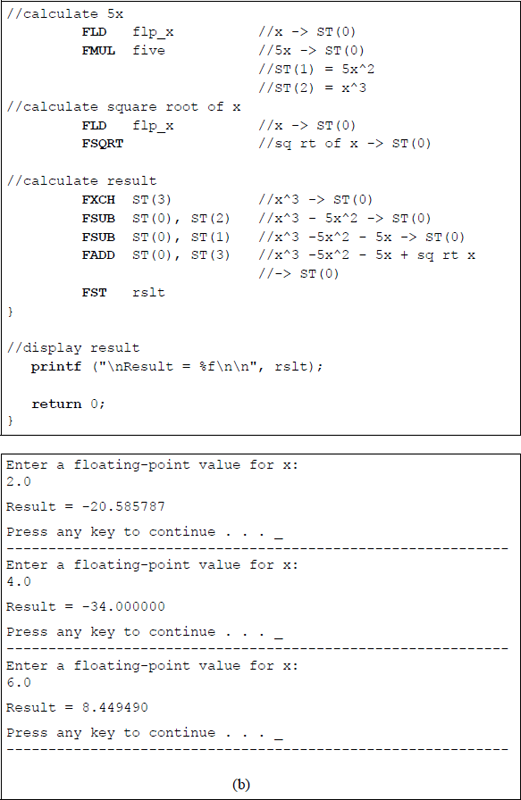

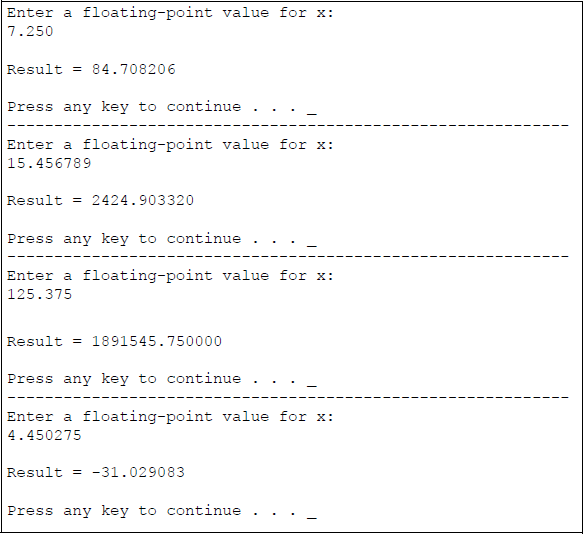

Example 17.13 This example calculates the value of the following expression using x as a variable for floating-point arithmetic:

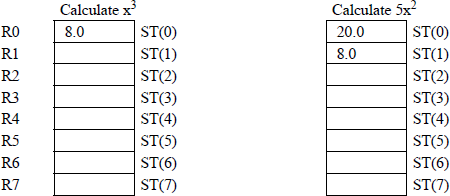

Figure 17.18 shows the assembly language module embedded in a C program to perform the calculations for the given expression. Figure 17.19 shows the contents of the register stack during execution of the program for the variable x that is equal to 2.0.

Program to calculate the given expression for different values of x: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

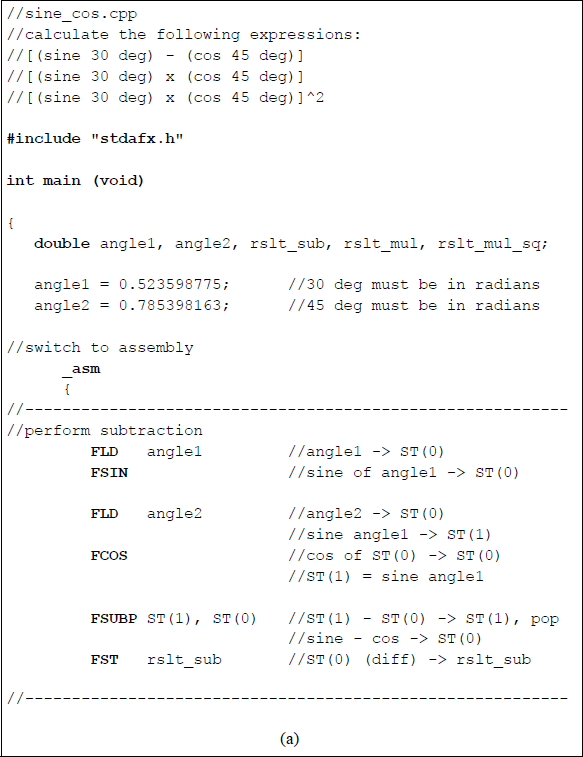

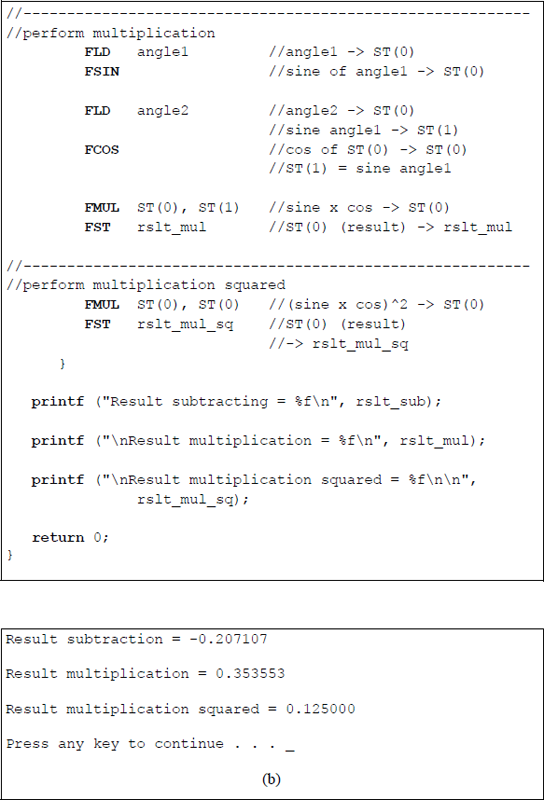

Example 17.14 This example calculates the value of the following trigonometric expressions using floating-point arithmetic:

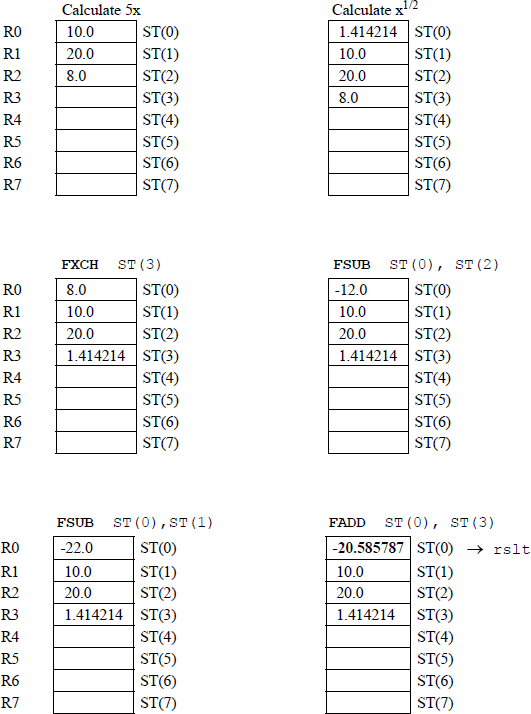

Figure 17.20 shows the assembly language module embedded in a C program to perform the calculations for the given trigonometric expressions. Note that the degrees must be given in radians. Figure 17.21 shows the contents of the register stack during execution of the program for the [(sine 30°) – (cosine 45°)] operation.

Program to calculate the values of the given trigonometric expressions: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

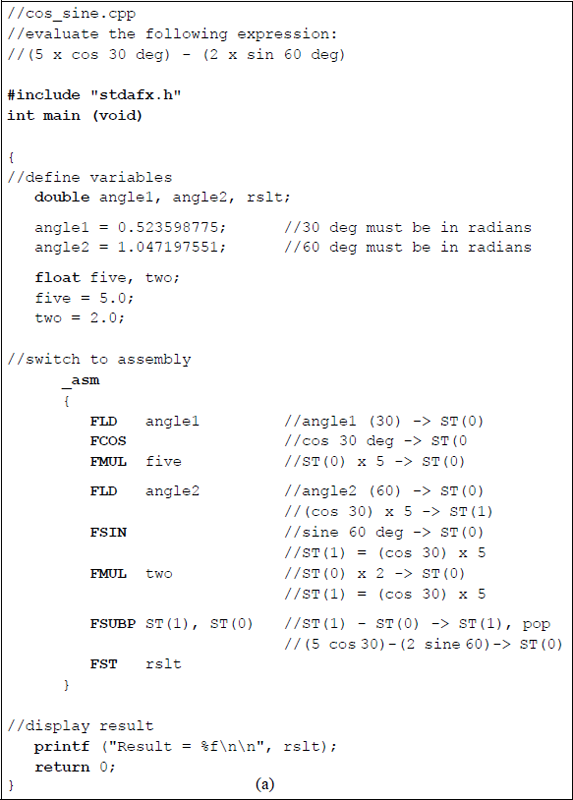

Example 17.15 This example calculates the value of the following trigonometric expression using floating-point arithmetic:

Figure 17.22 shows the assembly language module embedded in a C program to perform the calculation for the given trigonometric expression. Note that the degrees must be given in radians.

Program to calculate the value of the given trigonometric expression: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

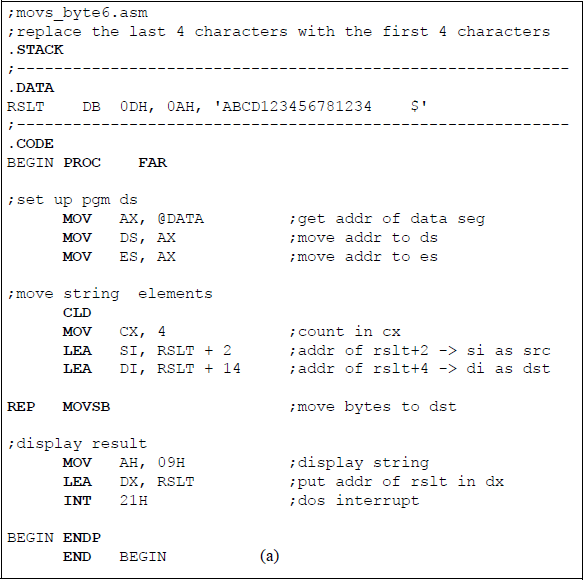

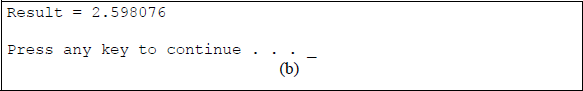

Example 17.16 This example uses the move data from string to string for bytes (MOVSB) instruction to overwrite data in a given string. The repeat prefix (REP) is also used in the program to copy four bytes from the given string to a different location in the same string. Figure 17.23 shows the assembly language program — not embedded in a C program — to perform the operation.

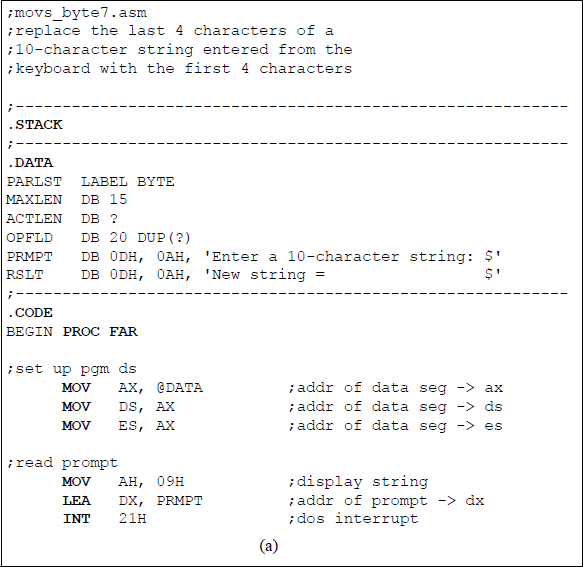

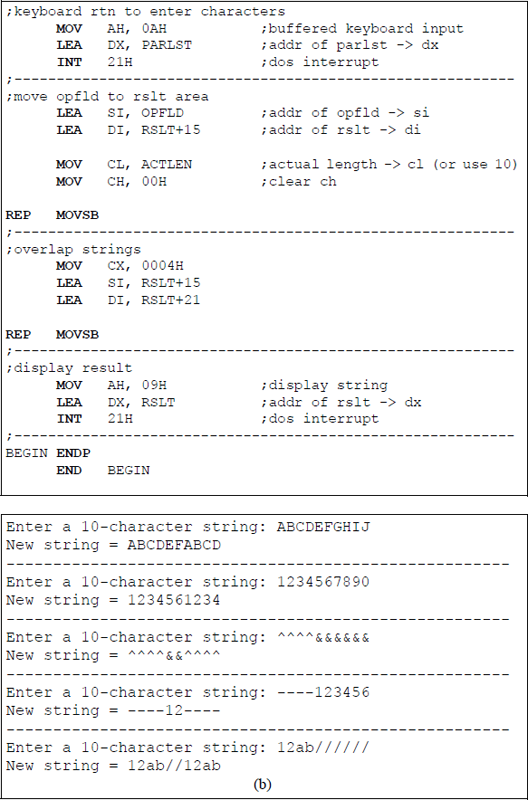

Example 17.17 This example is similar to Example 17.16; however, the string is entered from the keyboard. The move data from string to string for bytes (MOVSB) instruction is also used together with the repeat prefix (REP) to replace the last four characters of a 10-character string with the first four characters. Figure 17.24 shows the assembly language program — not embedded in a C program — to perform the operation.

Program to exchange the last four characters of a 10-character string with the first four characters: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

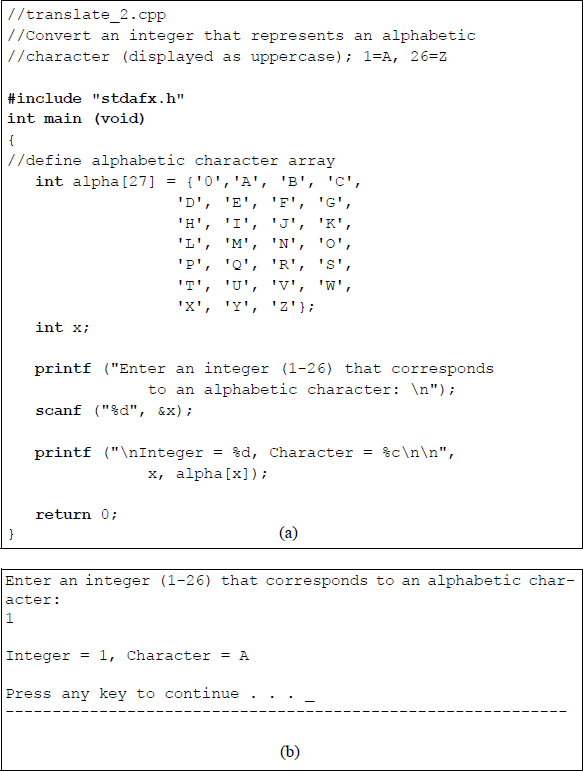

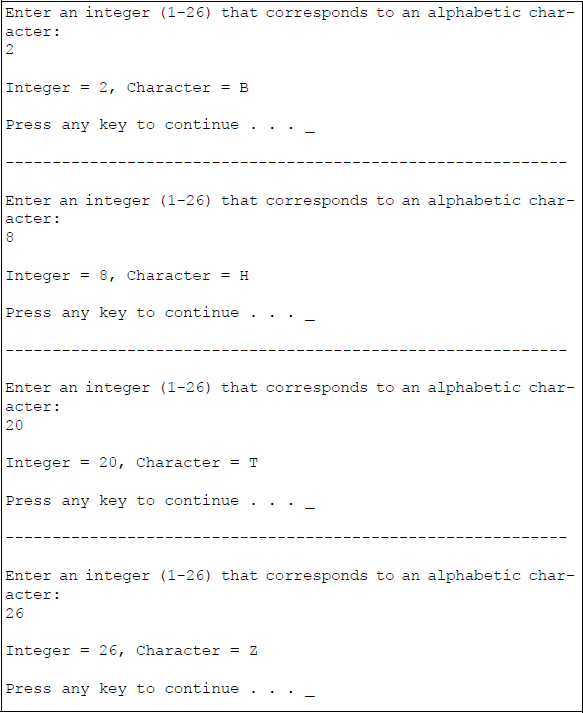

Example 17.18 This example converts an integer (1 — 26) that is entered from the keyboard to the corresponding uppercase alphabetic character. An array is used to define the uppercase alphabetic characters. Figure 17.25 illustrates the program written in the C programming language.

Program to convert an integer to the corresponding uppercase alphabetic character: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

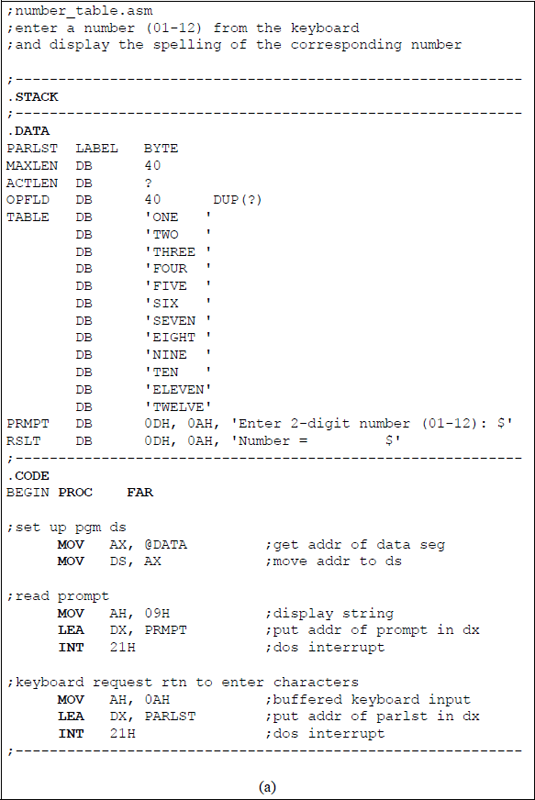

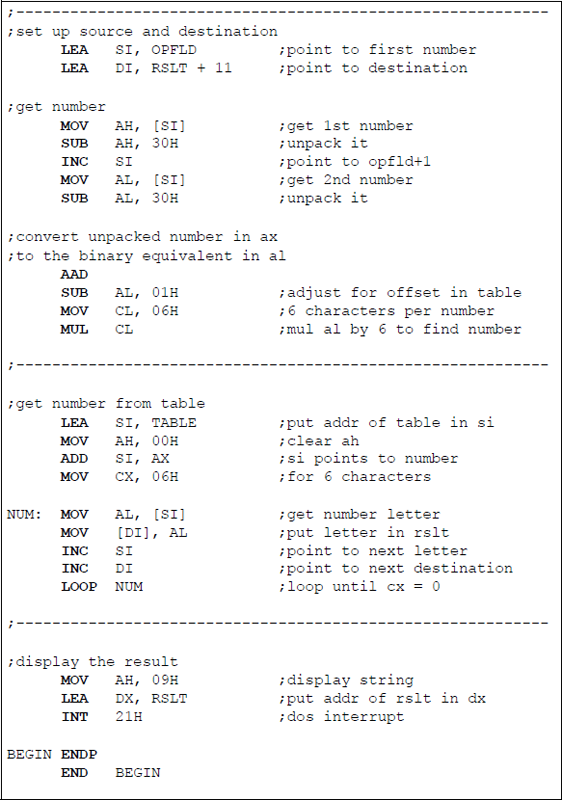

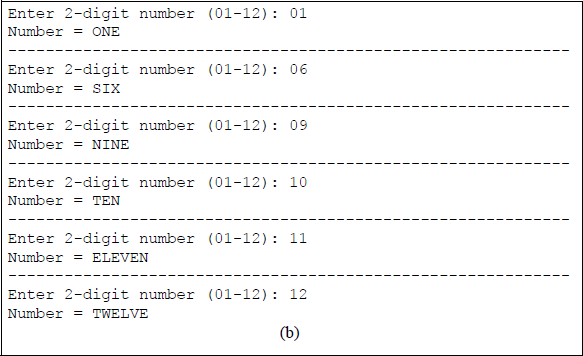

Example 17.19 This example utilizes an array to translate a 2-digit number that is entered from the keyboard to the correct spelling of the corresponding number. The 2-digit numbers are in the following range: 01 — 12. Figure 17.26 shows the assembly language program — not embedded in a C program — to perform the translation operation. Since the length of the longest number is six characters, each table entry in the array must contain six locations.

Program to translate a 2-digit number to the correct spelling of the number: (a) the program and (b) the outputs.

17.2 Problems

17.1 Write a program in assembly language — not embedded in a C program — that determines the largest number from eight single-digit numbers that are entered from the keyboard, then display the number.

17.2 Write a program in assembly language — not embedded in a C program — that counts the number of times that a number occurs in an array of eight numbers. The first number entered from the keyboard is the number that is being compared to the remaining eight numbers. Display the result.

17.3 Write a program in assembly language — not embedded in a C program — that translates an ASCII character (0 through 9) that is entered from the keyboard to the letters a through j, respectively.

17.4 Write an assembly language module embedded in a C program that uses the exclusive-OR function to operate on a string of hexadecimal characters that are entered from the keyboard. Perform the operation on the following character positions in the specified sequence, then display the results:

17.5 Write a program in assembly language — not embedded in a C program — that calculates the factorial of numbers entered from the keyboard in the range of 1 through 6. Display the results.

17.6 Write an assembly language module embedded in a C program to obtain the sum of cubes for the numbers 1 through 5. Display the resulting sum of cubes.

17.7 Write an assembly language module embedded in a C program to calculate 2 to power of n (0 – 8), where the variable n is entered from the keyboard.

17.8 Write an assembly language module embedded in a C program to evaluate the following expression using fixed-point integers for bytes, words, and double-words and obtain the quotients only:

17.9 Write an assembly language module embedded in a C program to evaluate the expression shown below for Y using a floating-point number for the variable X. The range for X is –3.0 ≤ X ≤ +3.0. Enter several numbers for X and display the corresponding results.

17.10 Write an assembly language module embedded in a C program to determine the result of the equation shown below, where L and C are floating-point numbers. The variables L and C are entered from the keyboard. Display the results.

17.11 Given the program segment shown below, obtain the results for the following floating-point numbers: 2.0, 10.0, and 15.0.

. . .FLD flp_numFMUL ST(0), ST(0)FLDPIFMUL ST(0), ST(1)FST rslt. . .17.12 Given the program segment shown below, obtain the results for the following floating-point numbers:

flp_num1 = 125.0, flp_num2 = 245.0

flp_num1 = 650.0, flp_num2 = 375.0

flp_num1 = 755.125, flp_num2 = 575.150. . .FLD flp_num1FSQRTFLD flp_num2FSQRTFSUBP ST(1), ST(0)FST rslt. . .17.13 Write an assembly language module embedded in a C program to determine the result of the following equation:

17.14 Write an assembly language module embedded in a C program to calculate the tangent of the following angles using the sine and cosine of the angles:

17.15 Write an assembly language program — not embedded in a C program — that replaces all spaces with hyphens in a character string entered from the keyboard.