Chapter 4

C Programming Fundamentals

The C programming language was developed by Bell Laboratories in 1972 and has become the predominant high-level programming language. As a high-level language, C programs are machine independent; that is, they can be run on different computer systems. Assembly language uses an assembler to convert the symbolic program to machine code; whereas, the C programming language uses a compiler to convert the source code into machine code.

The C language is case sensitive; therefore, add () and ADD () are different function names. It is common practice to use lowercase for both the code statements and the comments. The main purpose of this chapter is to provide sufficient information regarding C programming in order to demonstrate how a C program can be linked to an assembly language program. This concept will be used in subsequent chapters.

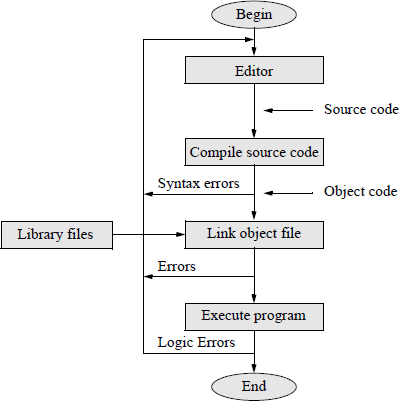

An editor is used to create a disk file for the source code, which is saved with a .c or a .cpp extension. The source code is then compiled to create an object file, which is linked with library files to assign addresses and to create an executable file that can be run on a computer. The flowchart of Figure 4.1 illustrates this development cycle.

4.1 Structure of a C Program

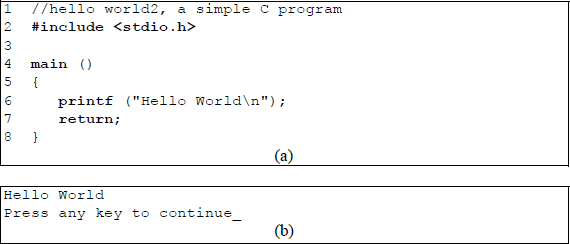

A simple C program is shown in Figure 4.2 displaying both the program code and the outputs obtained from the program. The program contains some basic statements and symbols that are inherent to C programs. Line 1 is a comment line indicated by double forward slashes //. This comment syntax is used for single-line comments only. A second syntax to specify a multiple-line comment uses the symbol /* before the first comment character, followed by the comment, and terminated by the symbol */. This syntax can also be used for single-line comments. Examples of different types of comments are shown below.

//This is a single-line comment.

/*This is a single-line comment.*/printf (“Hello World\n”); //comment for this line of code/*

This is a multiple-line comment

used to accommodate information

that spans several lines.

*/

A simple C program to illustrate some basic characteristics: (a) the C program and (b) the resulting output generated by the program.

Line 2 is a preprocessor directive used to read in another file and include it in the program. Preprocessor directives begin with symbol #. It informs the compiler to include at this location in the program information that is contained in the stdio.h file. The angle brackets < > indicate that the stdio.h file is located in a specific machine-dependent location. The stdio.h files are specified by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) and include the printf () function used in this program. Line 3 is a separation line.

Line 4 consists of a function called main (), where the parentheses indicate to the compiler that it is a function. The keyword void can also be included within the parentheses to indicate that no arguments are being passed to the function. Line 5 contains a left brace {, which marks the beginning of the body of the function. Left and right braces are also used as delimiters to group statements together.

Line 6 invokes the print function printf (), which displays information on the monitor screen. This function is part of the standard library of functions contained in the C programming environment. Information pertaining to the printf () function is contained in the stdio.h header file. The data within the parentheses is a series of characters called a string argument contained within double quotation marks. The string is called an argument and is displayed on the screen, except for the symbol (\ n), which is a newline character. This character is not displayed, but simply places the cursor at the beginning of the next line. Line 6 is terminated with a semicolon — all declarations and statements are terminated with a semicolon.

Line 7 indicates that the function returns to the calling function main (). This is part of the ANSI requirement for a C program. An expression can be passed to the calling function, in which case the expression is usually enclosed in parentheses. The expression may be the result of a calculation requested by the calling function. A value of zero means that the program was executed correctly — a nonzero integer indicates that the function main () was unsuccessful. Line 8 is the closing right brace and indicates the end of the program specified by the function main ().

It is important to make the program format easy to read. This makes the program easier to understand and to correct or modify. One technique to make the program easier to understand is to make the variable names meaningful. Comments also help to clarify certain tasks in the program and indicate more clearly how the program functions. Comments should be placed before a code segment to illustrate the function of the segment and also on individual lines of code, where applicable.

Blank lines help to delineate different segments of the program by separating them. Although C is classified as a free-form language — allowing more than one statement per line — the code is easier to read if there is only one statement per line. The braces should be placed on the extreme left of the page with the body of the segment right-indented a few spaces. These techniques make the program easier to read and understand at a later date for both the programmer who wrote the code and others.

4.2 Variables and Constants

This section describes how the C programming language defines and stores variables and constants. Variables store values in memory and the type of each variable must be specified; that is, the variable must be declared as type character, integer, and so forth. The focus will be on numeric variables and numeric constants.

4.2.1 Variables

A variable is a named memory location and must be declared before it is used in the program. The declaration of a variable with an assigned type permits the compiler to assign an appropriate amount of storage for the variable. A variable is defined by indicating the type of variable followed by the name of the variable, which can range from a single first letter to 31 characters, including underscore characters. Some typical variables are shown in Table 4.1. The typical ranges for the variables listed in Table 4.1 are shown in Table 4.2.

Some Typical C Variables

Type |

Keyword |

Meaning |

|---|---|---|

Character |

char |

Signed character (one byte) |

Unsigned character |

unsigned char |

Unsigned character (one byte) |

Integer |

int |

Signed integer (two bytes) |

Unsigned integer |

unsigned int |

Unsigned integer (two bytes) |

Float |

float |

Single-precision floating-point numbers |

Double |

double |

Double-precision floating-point numbers |

Typical Ranges for Some Typical C Variables

Type |

Range |

Bits required |

|---|---|---|

char |

–128 to +127 |

8 bits |

unsigned char |

0 to 255 |

8 bits |

int |

–32,768 to +32,767 |

16 bits |

unsigned int |

0 to 65,535 |

16 bits |

float |

10−38 to 10+38 (approximate range) |

32 bits |

double |

10−308 to 10+308 (approximate range) |

64 bits |

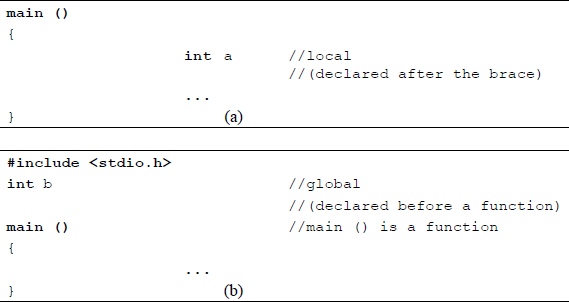

Variables that are declared outside a function — defined before the function brace — are global variables and can be accessed by any function in the remainder of the program. It is preferable to have global variables declared at the beginning of the program prior to main (), because this makes them easier to notice.

Variables that are declared inside a function — defined after the brace at the start of the function — are local variables and can be accessed only by the function in which they are defined. They are unique from other variables of the same name that are declared at other locations in the program; that is, they are distinct and separate variables with the same name. Variables are declared as follows: type var_name; for example: int counter;. Examples of global and local variable declarations are shown in Figure 4.3.

More than one variable can be declared by using commas to separate the variable names; for example, the floating-point numbers x, y, and z: float x, y, z;. Variables can be assigned values by using the assignment operator (=) in an assignment statement, as follows: var_name = value (or expression); for example: num = 100;. The variable name is any variable that has been previously defined. Commas are not allowed in numerical values; thus, the number 36,000 is invalid.

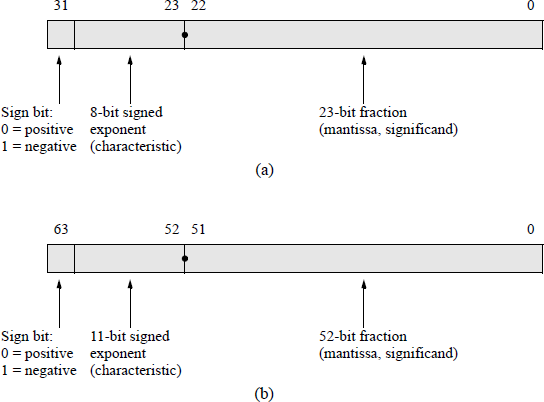

Variables can be initialized when they are declared; for example, int num = 100;. Since an integer has a range of –32,768 to +32,767, a value of 50,000 would be beyond the range of an integer. Errors of this type are undetected by the compiler. An integer value has no fractional part; however, a floating-point value must include a decimal point. Floating-point numbers are segmented into the sign, the exponent (characteristic), and the fraction (mantissa or significand), as shown in Figure 4.4 for single-precision and double-precision formats.

IEEE floating-point formats: (a) 32-bit single precision and (b) 64-bit double precision.

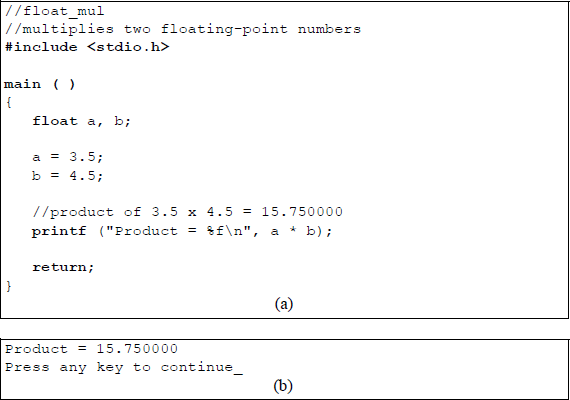

The result of a floating-point operation can be displayed on the monitor by using the print function printf (), as shown in the short program of Figure 4.5, which multiplies two floating-point numbers a and b, then displays the product. The symbol %f is a conversion specifier that causes the result of the multiply operation to be displayed as a floating-point number. Conversion specifiers are covered in more detail in a later section. The symbol (*) is the multiplication operator. Operators are also covered in a later section.

Example of floating-point multiplication: (a) the C program and (b) the resulting output generated by the program.

4.2.2 Constants

Unlike variables, constants are fixed values that cannot be altered by the program. There are primarily four types of constants in the C programming language: integer constants, floating-point constants, character constants, and string constants.

Integer constants An integer is a whole number without a decimal point, such as the natural numbers and their negatives, including the number zero. Examples of integer constants are 10 and –100. Integer constants can be represented in three different radices: decimal (radix 10, with digits 0 through 9), octal (radix 8, with digits 0 through 7), and hexadecimal (radix 16, with digits 0 through 9 and letters A through F that represent digits 10 through 15 as one character).

A decimal number in C is entered as shown above for 10 and –100 with no prefix. If there is no leading plus or minus sign, then the compiler assumes that the number is positive. An octal number is preceded by a zero (0) prefix; for example, . Octal numbers can be preceded by a plus or minus sign. A hexadecimal number is preceded by a 0x prefix; for example, and can have a plus or minus sign.

An integer constant can also be written as a literal constant in which the integer constant is entered directly into the statement that specifies the integer; for example: int num = 35;.

Floating-point constants A floating-point number consists of a sign, either plus or minus — if there is no sign indicated, then the number is assumed to be positive; an exponent character — either E or e; an integer exponent; and a significand containing a decimal point.

Floating-point constants are decimal digits that are of type float, double, long, or long double. Unless otherwise specified, floating-point numbers are stored as double as the default type; that is, they are stored in the double-precision format. A suffix can be added to the constant, however, to uniquely specify the type. A suffix of f or F specifies a single-precision number; a suffix of l or L specifies a double-precision number. The C compiler maps long double to type double.

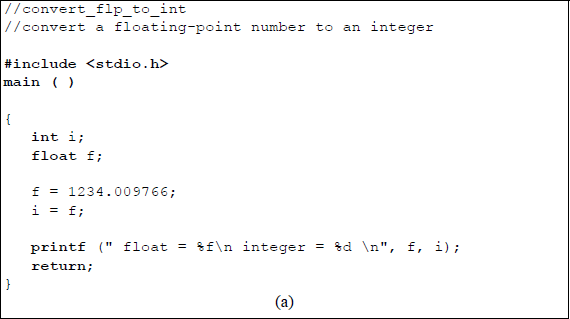

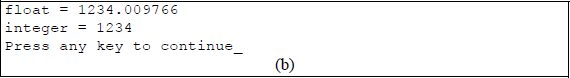

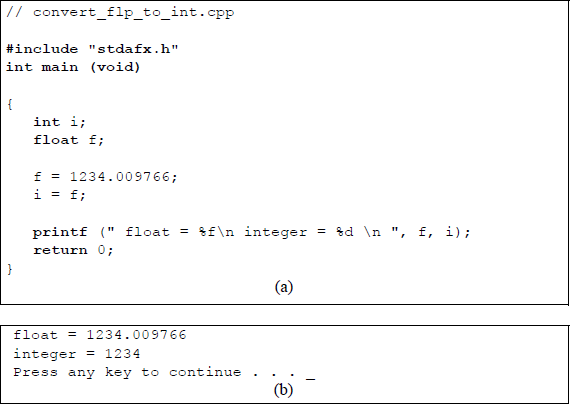

Floating-point numbers can also be written in scientific notation. Thus, ; ; and . When converting a floating-point number to an integer, the fraction is truncated, as shown in Figure 4.6, where the conversion specifier %f is a floating-point number and %d is a signed decimal integer.

Program to illustrate converting a floating-point number to an integer: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs obtained from the program.

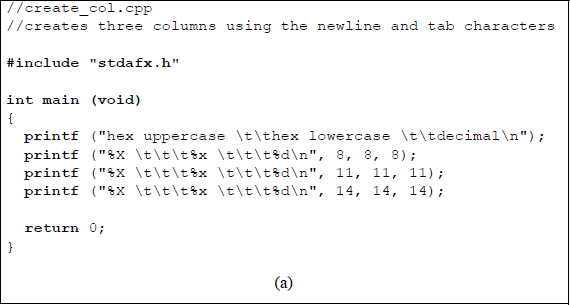

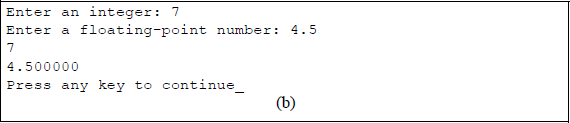

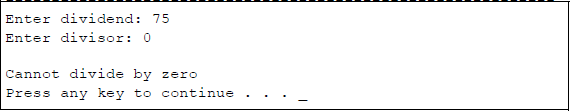

When using the Microsoft Visual C++ Express Edition, the #include directive is slightly different and main is preceded by the int data type, as shown in Figure 4.7 for the floating-point-to-decimal conversion of Figure 4.6. The stdafx.h directive is a precompiled header directive, which is an abbreviation for Standard Application Framework Extensions. This directive contains standard and project-specific files that are to be included in the program.

Program to illustrate converting a floating-point number to an integer using C++ Express Edition: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs obtained from the program.

The construct int main (void) is a function prototype that has two components. The int is the return type, which is the type of variable that is returned to the operating system at the completion of the program and represents the status of the program execution. The main (void) indicates to the compiler where program execution begins and that no arguments are being passed to the invoked function. The left and right braces indicate the beginning and end of the function.

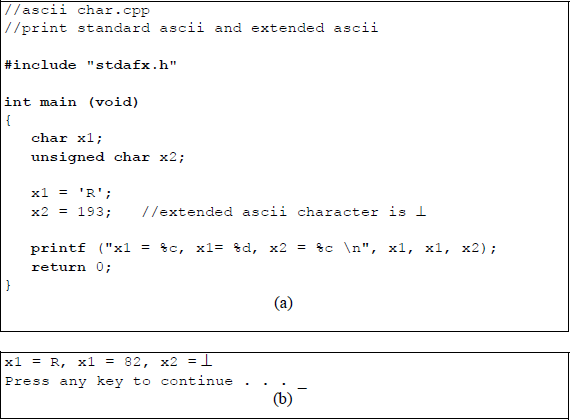

Character constants Unlike variables, the value of a constant cannot be changed. The keyword char indicates the type used for letters and other characters, such as !, &, $, %, and *, among others. When characters are stored, they are actually stored as integers using the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII). A different code is used for IBM mainframes, called the Extended Binary Coded Decimal Interchange Code (EBCDIC).

For example, to store an uppercase A represented in ASCII, 6510 (4116) is stored; whereas, to store a lowercase a, 9710 (6116) is stored. The standard ASCII code has a range of decimal 0 to 127 (hexadecimal 00 to 7F). The extended ASCII code has a range of decimal 128 to 255 (hexadecimal 80 to FF) for special characters, such as ≥ or ≤. Both standard ASCII and extended ASCII characters are stored as one-byte integers.

Character constants are written within single quotation marks, such as ‘#’ and ‘R’, which act as delimiters for the character. The single quotation marks indicate to the compiler that a single character is specified. Note that the number 7 and the character constant ‘7’ are different — the number 7 has an integer value of seven; the character constant ‘7’ has an integer value of 5510 (3716).

The program shown in Figure 4.8 illustrates printing a standard ASCII character and an extended ASCII character. The conversion specifier %c specifies a character value. An extended ASCII character must be unsigned.

Program to illustrate a program to print standard ASCII and extended ASCII characters: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs obtained from the program.

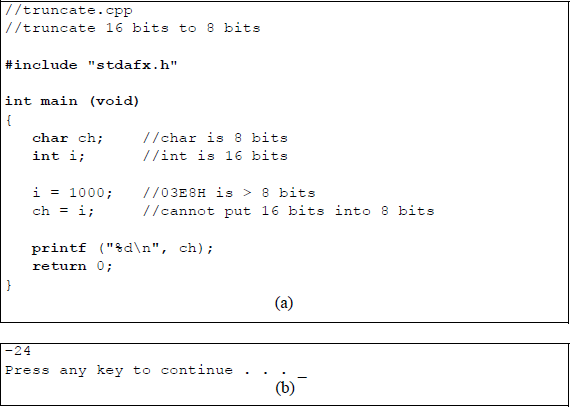

If an attempt is made to place a 16-bit character into an 8-bit integer, only the low-order eight bits will be retained — the high-order eight bits will be removed. For example, 100010 = 03E816. This value is represented in eight bits as E816 = 1110 10002 = –24 in 2s complement representation. Figure 4.9 illustrates this concept.

Program to illustrate high-order truncation when attempting to place a 16-bit variable into an 8-bit variable: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

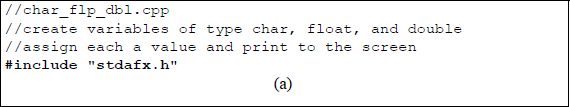

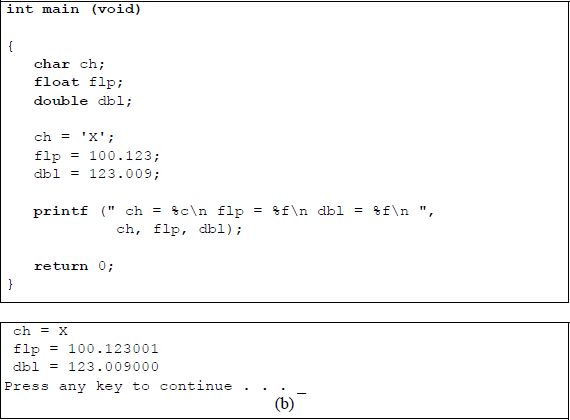

The program shown in Figure 4.10 illustrates declaring three different types: char, float, and double, then assigns a value to each type and then prints the output to the screen using one print statement.

Program to illustrate assigning values to types char, float, and double: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

String constants String constants are a set of characters enclosed by double quotation marks. The string characters are terminated by a null zero (\0). This is a binary zero (0000 0000) and is inserted by the compiler to mark the end of the string — it is not the number zero (0011 0000). The null zero is also called the string delimiter. Since the quotation marks are not stored as part of the string, the only indication that the compiler has that the string has ended is the null zero.

Strings produce a one-dimensional array in memory, including the terminating null zero. To use double quotation marks in the string, precede the quotation mark with a backslash. Examples of strings are shown in Table 4.3 together with the string lengths.

String Examples and their Lengths

String |

Length in Bytes |

|---|---|

"012" |

3 |

"Hello World" |

11 |

"Temperature is 74 degrees Fahrenheit." |

36 |

4.3 Input and Output

This section presents additional detail on the printf () function and introduces the scanf () function. These are the only two input/output (I/O) functions that will be used in later chapters when linking C to an assembly language program. Other I/O functions that will not be covered in this section include the getchar () function, which reads the next character typed from the keyboard as an integer; the putchar () function, which writes a single character to the screen; the getche () function, which reads the next character and then displays the character on the screen; and the getch () function, which is similar to the getche () function, but does not display the character on the screen, among others.

4.3.1 Printf () Function

The printf () function, together with the scanf () function, are two of the most versatile I/O functions in the C repertoire. The printf () function has the general format shown below. It prints the characters that are contained within the double quotation marks. Some of the more common conversion specifiers are shown in Table 4.4.

printf ("format_string and conversion specifier(s)\n",

one or more arguments);

Some Common Conversion Specifiers

Conversion Specifiers |

Resulting Output |

|---|---|

%c |

Single character |

%d |

Signed decimal integer |

%u |

Unsigned decimal integer |

%f |

Decimal floating-point number |

%s |

Character string |

%o |

Unsigned octal integer |

%x |

Unsigned hexadecimal integer (a–f) |

%X |

Unsigned hexadecimal integer (A–F) |

%% |

Percent sign |

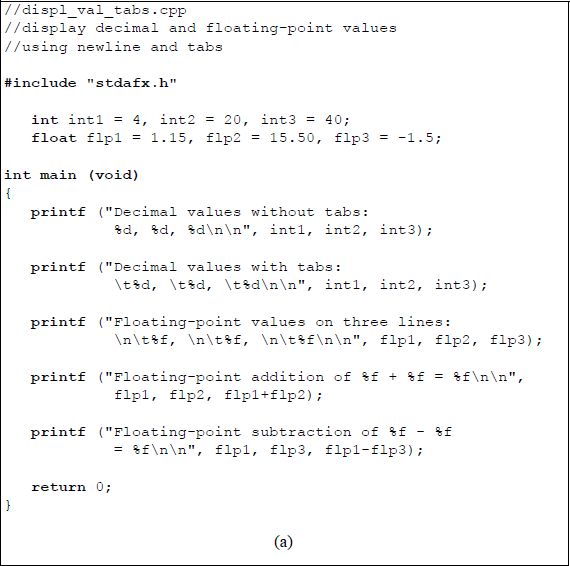

The escape character for a newline (\n) has already been discussed. This character causes a carriage return and a line feed. Another escape character is the tab character (\t), which advances the output horizontally to the next tab stop. Use of these two escape characters is shown in the program of Figure 4.11, which displays decimal and floating-point numbers in various configurations using the newline and tab characters.

Program to illustrate the use of the newline character and the tab character: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

Three integers are defined: int1 = 4, int2 = 20, and int3 = 40. These are displayed on separate lines with and without tabs. The double newline characters cause the next printed line to be two lines below the current line. The floating-point numbers are displayed on three separate lines and indented by placing a newline character and a tab character before each floating-point conversion specifier. The sum of the two floating-point numbers flp1 = 1.15 and flp2 = 15.50 is obtained by the mathematical operator (+) to yield a sum of flp1 + flp2 = 16.650000. The subtraction of the two floatingpoint numbers positive flp1 = 1.15 and negative flp3 = –1.5 is obtained by the mathematical operator (–) to yield a result of flp1 – flp3 = 2.650000. The mathematical operators are discussed in detail in the next section.

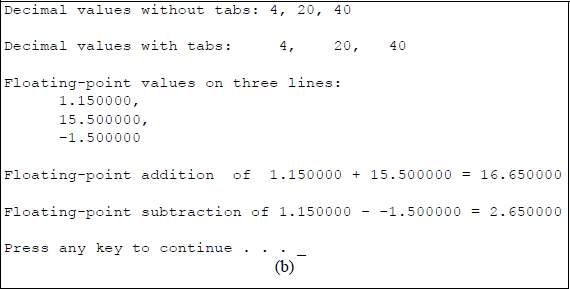

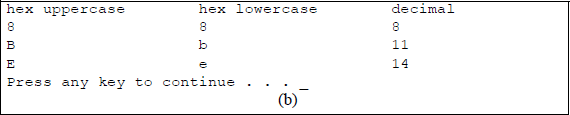

Figure 4.12 illustrates a method to align columns using the newline and tab characters. The columns display decimal numbers in both the uppercase and lowercase hexadecimal number representation. The conversion specifiers %X and %x specify uppercase and lowercase hexadecimal, respectively.

Program to illustrate the use of the newline character and the tab character to create columns: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

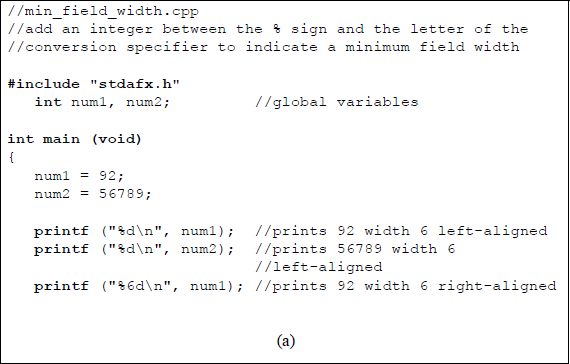

One final example to illustrate alignment is shown in Figure 4.13, which adds a minimum field width integer between the percent sign (%) and the letter (d) of a conversion specifier. The integer is referred to as a minimum field width specifier and provides a minimum field width for the output. For example, a minimum right-aligned field width of six spaces is specified by %6d, as shown in the program of Figure 4.13.

Program to illustrate the use of the minimum field width specifier: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

If no minimum field width is specified, the output is left-aligned. A minimum field width of %06d will right-align the output with high-order zeroes, if necessary, to fill in the minimum field width. If the minimum field width is less than the width of the output, then the entire output is printed since the output is greater than the specified minimum width.

4.3.2 Scanf () Function

The scanf () function is the most commonly used input function of the several input functions in the C programming language. The customary use for the scanf () function is to input data from the keyboard. It converts inputs to the following formats: decimal integers, floating-point numbers, characters, and strings. The scanf () function can contain spaces and tabs — which are ignored — to make the string more readable. The scanf () function is similar to the printf () function — it contains a control string of format specifiers (also called conversion specifiers) %d, %c, %f, and so forth, which describe the format of each input variable. The general format for the scanf () function is shown below, together with a specific format to read a decimal integer.

scanf () ("conversion specifiers", argument names);

scanf ("%d", &num);

The ampersand (&) is the address-of operator, which indicates that the decimal input number is to be stored in the location assigned to the variable num. The conversion specifiers for the scanf () function are the same as for the print () function and are reproduced in Table 4.5 for convenience. When the scanf () stores input data, it converts the data to the corresponding conversion specifier in the format string.

The scanf () function is normally preceded by the printf () function, which requests the user to enter information. The scanf () function then assigns the input data to a specific location.

Some Common Conversion Specifiers

Conversion Specifiers |

Resulting Output |

|---|---|

%c |

Single character |

%d |

Signed decimal integer |

%u |

Unsigned decimal integer |

%f |

Decimal floating-point number |

%s |

Character string |

%o |

Unsigned octal integer |

%x |

Unsigned hexadecimal integer (a–f) |

%X |

Unsigned hexadecimal integer (A–F) |

%% |

Percent sign |

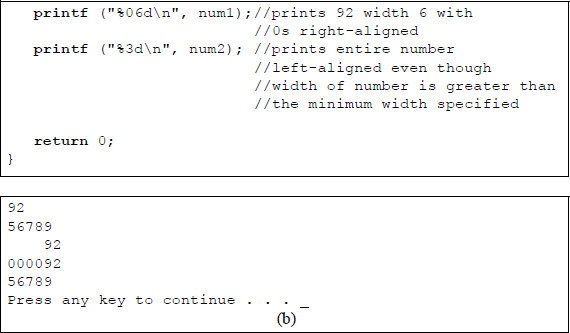

The example shown in Figure 4.14 requests the user to enter an integer number and a floating-point number using the printf () function, then stores the data in specific locations using the scanf () function, then prints the input data to the monitor screen.

Program to illustrate the use of the printf () and scanf () functions to enter and print an integer and a floating-point number: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

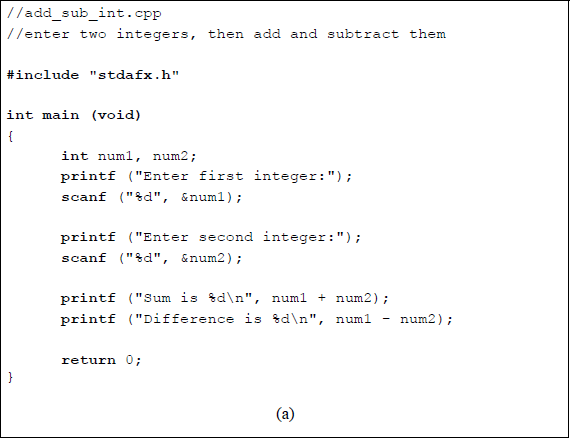

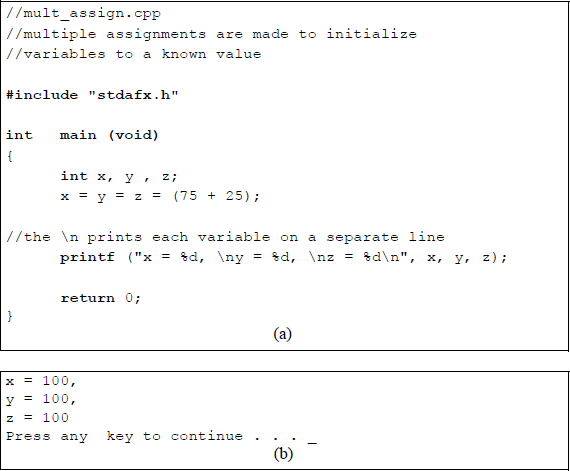

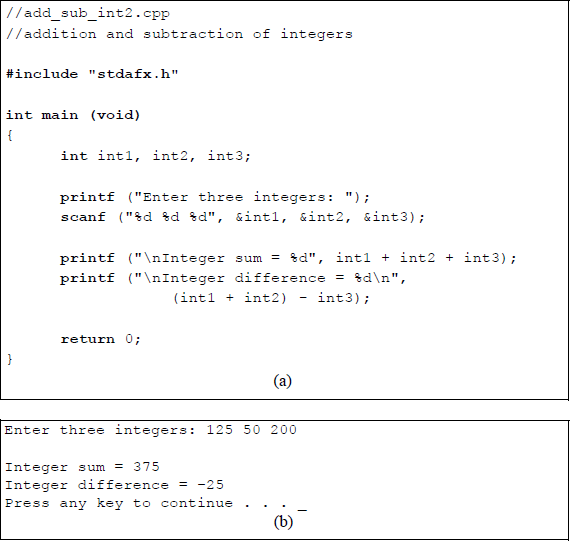

The example shown in Figure 4.15 uses the printf () function and the scanf () function to request the user to enter two integer numbers, perform an addition and subtraction on the numbers, then print the sum and difference. This program uses the arithmetic operators of addition (+) and subtraction (–), which are covered in more detail in the next section.

Program to illustrate the use of the printf() and scanf () functions to enter two integers, perform addition and subtraction on the two numbers, then print the sum and difference: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

4.4 Operators

Operators are symbols that direct C to execute specific operations. Some of the more common operators are used to perform the following operations: an arithmetic operation, a relational operation to determine the relationship between two expressions, a logical operation of AND, OR, or NOT, a conditional operation to replace the if-else statement, an increment or decrement operation, and bitwise operations that perform logical operations on a bit-by-bit basis. Table 4.6 lists the more common operators.

Common Operators Used in C Programming

Operator |

Function |

|---|---|

= |

Assignment |

+ |

Addition |

– |

Subtraction |

* |

Multiplication |

/ |

Division |

% |

Modulus (remainder) |

= = |

Equal to |

> |

Greater than |

< |

Less than |

>= |

Greater than or equal to |

<= |

Less than or equal to |

!= |

Not equal to |

&& |

Logical AND |

| | |

Logical OR |

! |

Logical NOT |

? : |

Conditional |

++ |

Increment the operand by 1 |

− − |

Decrement the operand by 1 |

& |

Bitwise AND |

| |

Bitwise OR |

^ |

Bitwise exclusive-OR |

~ |

Bitwise 1s complement |

4.4.1 Arithmetic Operators

An expression is a conjunction of operators and operands — or expressions — and may also contain variables and constants. Expressions can contain multiple operators that are evaluated in a specific sequence, depending on the precedence of the operators; for example, multiplication, division, and modulus have a higher precedence than addition. However, parentheses can be utilized to alter the precedence, as shown in the following example:

result = (6 + 7) * 8;

Normally, the multiplication operator (*) would have a higher precedence than the addition operator (+). The use of parentheses, however, places a higher precedence on the addition operation than on the multiply operation. This provides a value of 104 for the right-hand expression, which is assigned to the variable result.

Assignment operator The assignment operator (=) does not signify equality — it means to copy the right-hand side expression to the left-hand side tar expression. For example, the statement x = y means to copy the value of y into x, that is, y is assigned to x, where the variable x refers to a memory location. However, a value cannot be assigned to a constant.

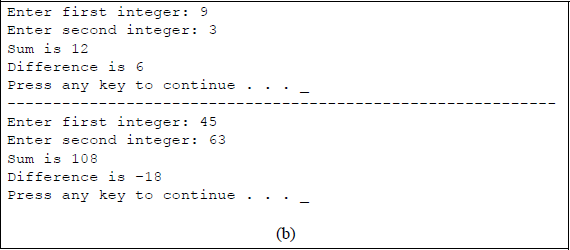

There can be multiple assignments in a single statement, where the order of assignments is in a right-to-left sequence. For example, the statement shown below first assigns 75 to z, then assigns 75 to y, and finally assigns 75 to x. The program shown in Figure 4.16 illustrates this concept. Multiple assignments is a simple way to initialize variables to a known value.

x = y = z = 75;

Program to illustrate using multiple assignments: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

Addition and subtraction operators The operands used for addition are the augend and the addend. The addend is added to the augend to form the sum, which replaces the augend in most computers — the addend is unchanged. The addition operator (+) performs the addition operation on the two operands, which can be either constants or variables. The rules for binary addition are shown in Table 4.7. A carry of 1 indicates a carry-out to the next higher-order column.

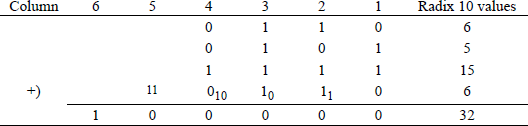

An example of binary addition is shown in Figure 4.17. The sum of column 1 is 210 (102); therefore, the sum is 0 with a carry of 1 to column 2. The sum of column 2 is 410 (1002); therefore, the sum is 0 with a carry of 0 to column 3 and a carry of 1 to column 4. The sum of column 3 is 410 (1002); therefore, the sum is 0 with a carry of 0 to column 4 and a carry of 1 to column 5. The sum of column 4 is 210 (102); therefore, the sum is 0 with a carry of 1 to column 5. The sum of column 5 is 2 (102); therefore, the sum is 0 with a carry of 1 to column 6. The unsigned radix 10 values of the binary operands are shown in the rightmost column together with the resulting sum.

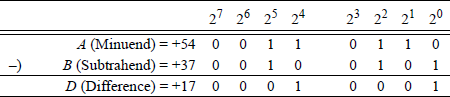

The operands used for subtraction are the minuend and the subtrahend. The subtrahend is subtracted from the minuend to obtain the difference. The subtraction operator (–) performs the subtraction operation on the two operands, which can be either constants or variables. The rules for binary subtraction are shown in Table 4.8. A borrow of 1 indicates a borrow from the minuend in the next higher-order column.

Rules for Binary Subtraction

Minuend |

Subtrahend |

Borrow |

Difference |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

0 |

− |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

− |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

− |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

− |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Two 8-bit operands are shown in Figure 4.18 to illustrate the rules for radix 2 subtraction in which all four combinations of two bits are provided. The borrow from the minuend in column 21 to the minuend in column 20 changes column 21 from 10 to 00; that is, the operation of column 21 then becomes 0 – 0 = 0. The program shown in Figure 4.19 illustrates the addition and subtraction operations utilizing three integers.

Program to illustrate the addition and subtraction of integers: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

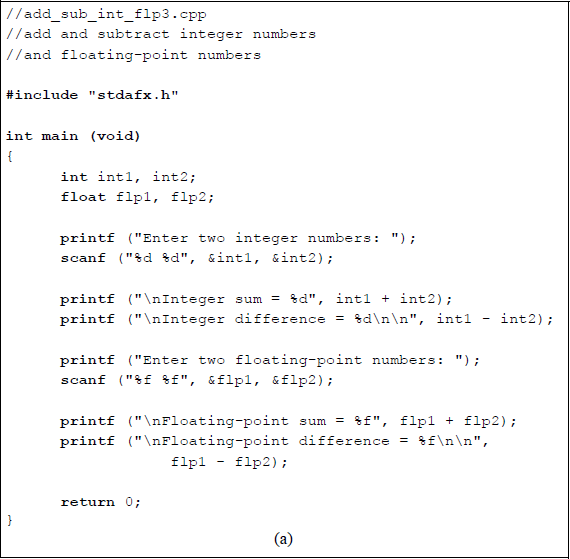

The program shown in Figure 4.20 illustrates addition and subtraction operations utilizing integer numbers and floating-point numbers. The keyword int establishes int1 and int2 as integers; in the same way, flp1 and flp2 are declared as type float. The scanf () function stores the two integers in the locations specified by &int1 and &int2, where the ampersand indicates the address-of. The arguments (or parameters) of the second print function specify an addition of int1and int2, in the same way that the arguments of the third print function specify a subtraction of int1and int2. In both print functions, the newline character (\ n) at the beginning of the format strings places the sum and difference on separate lines. The double newline characters insert a blank line between the integer difference result and the print function to enter two floatingpoint numbers. The conversion specifier (%d) in both cases indicate a decimal integer value.

Program to illustrate the addition and subtraction of integer numbers and floating-point numbers: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

The second scanf () function stores the two floating-point numbers in the locations specified by &flp1 and &flp2. The conversion specifier (%f) in both cases indicates a decimal floating-point value. The arguments of the print function specify an addition of flp1 and flp2, in the same way that the arguments in the next print function specify a subtraction of flp1 and flp2.

Multiplication and division operators The multiplication operator (*) multiplies the multiplicand by the multiplier to produce a product. In a hardware multiplication unit, the multiplicand and multiplier are both n-bit operands that produce a 2n-bit result. If the operands are in 2s complement notation, then the sign bit is treated in a manner identical to the other bits; however, the sign bit of the multiplicand is extended left in the partial product to accommodate the 2n-bits of the product.

The only requirement is that the multiplier must be positive — the multiplicand can be either positive or negative. This can be resolved by either 2s complementing both operands or by 2s complementing the multiplier, performing the multiplication, then 2s complementing the result.

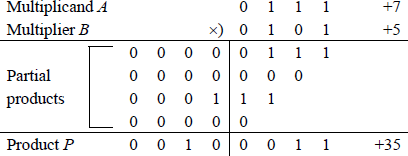

A simple example of multiplying two 4-bit operands is shown in Figure 4.21. Let the multiplicand and multiplier be a[3:0] = 0111 (+7) and b[3:0] = 0101 (+5), respectively to produce a product p[7:0] = 0010 0011 (+35). A multiplier bit of 1 copies the multiplicand to the partial product; a multiplier bit of 0 enters 0s in the partial product. This is the sequential add-shift multiplication algorithm. There are numerous methods to perform multiplication; however, since the topic of this book is programming, the multiplication algorithms are not important.

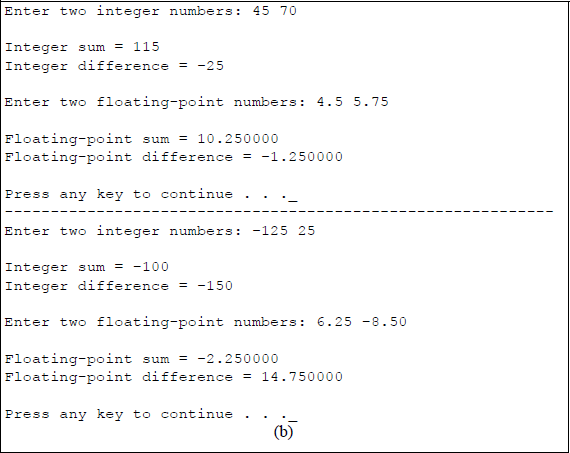

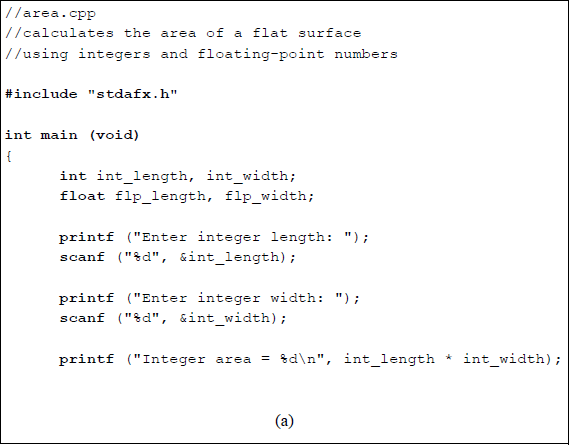

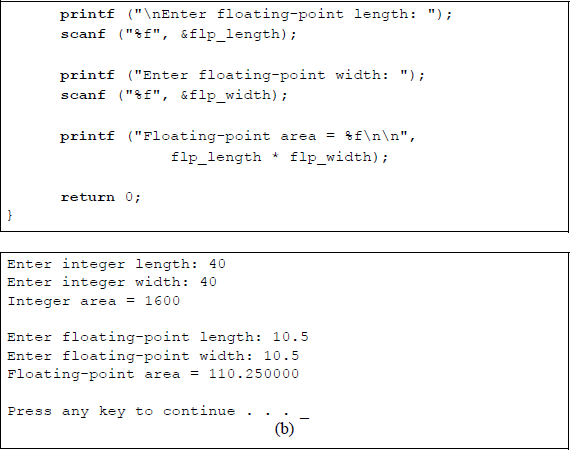

An example of integer and floating-point multiplication is shown in Figure 4.22, which prompts the user to enter an integer length and width, then prints the integer area. Next a floating-point length and width are entered, then the program prints the floating-point area.

Program to illustrate the multiplication of integer numbers and floating-point numbers: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

The division operator (/) divides the dividend by the divisor to produce a quotient when used in integer division. The integer division operation in C programming produces a quotient result only — the remainder is discarded; that is, any fraction is truncated, because integer division produces an integer result. If a remainder is desired, then this can be obtained by using the modulus operator (%) for integer division. Division can take place using either integer operands or floating-point operands. In a hardware division unit, a 2n-bit dividend is divided by an n-bit divisor to produce an n-bit quotient and an n-bit remainder.

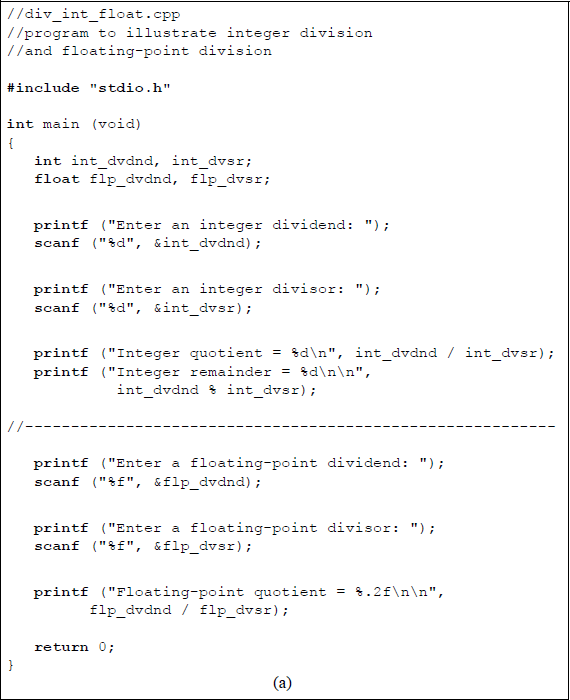

The example shown in Figure 4.23 is a program to illustrate integer division, the modulus operator, and floating-point division. The integer quotient is obtained by the operands that were entered by the user, as shown below.

Integer quotient = int_dvdnd / int_dvsr

The integer remainder is obtained using the modulus operator (%) as shown below.

Integer remainder = int_dvdnd % int_dvsr

The floating-point quotient is obtained by the division operator (/). Note that the conversion specifier for the result is %.2f, which means that the result is to be rounded up to two digits to the right of the decimal point.

Program to illustrate integer division, the modulus operator, and floating-point division: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

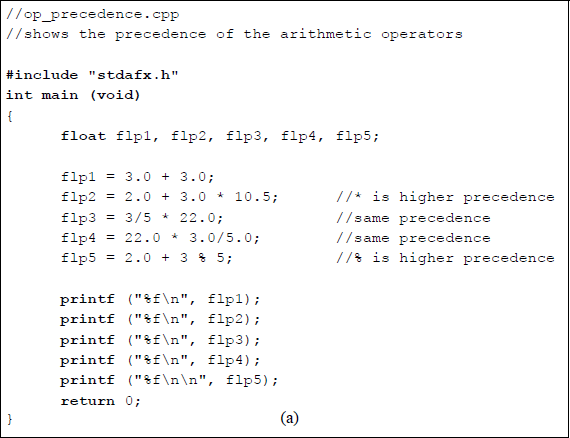

The program shown in Figure 4.24 illustrates the order of precedence of the arithmetic operators. The order of precedence is reproduced below for convenience. The value of the flp1 variable is straightforward, it is simply the sum of 3.0 + 3.0 = 6.000000. The value of the flp2 uses the operator precedence in the calculation, where the value of the variable is obtained by first multiplying 3.0 × 10.5 to yield 31.5; this result is then added to a value of 2.0 to yield a result of 33.500000.

In the calculation of flp3, both the division operator and the multiplication operator have the same precedence. Therefore, the operation proceeds in a left-to-right sequence. The division of 3/5 yields a result of zero; therefore, 0 × 22.0 = 0.00000. In the equation for flp4, both operators again have the same precedence and the operation proceeds in a left-to-right sequence. Thus, 22.0 × 3 = 66.0, which is then divided by 5.0 to yield a result of 13.200000. To obtain the value of flp5, the modulus operator takes precedence over the addition operator. The remainder of 3/5 is 3, which is added to 2.0 to yield a value of 5.000000.

Precedence Order |

Arithmetic Operator |

|---|---|

Highest order |

Multiplication (*), division (/), modulus remainder (%) |

Next highest order |

Addition (+), subtraction (−) |

4.4.2 Relational Operators

Relational operators compare data to determine the relationship between the data. There are six relational operators that are used for comparing data, where the data can be constants, variables, or expressions, or a combination of these. When determining the relationship between data, if the relationship is true, then a value of 1 (or nonzero) is returned; if the relationship is false, then a value of 0 is returned. The six relational operators are defined in Table 4.9.

Relational Operators

Operator Symbol |

Relationship |

Example |

|---|---|---|

= = |

Equal |

x = = y |

! = |

Not equal |

x ! = y |

> |

Greater than |

x > y |

> = |

Greater than or equal |

x > = y |

< |

Less than |

x < y |

< = |

Less than or equal |

x < = y |

Relational operators can be used for both integers and floating-point numbers. Relational operators have a lower precedence than the arithmetic operators. The relational operators (>), (> =), (<), and (< =) have a higher precedence than (= =) or (! =). Note that (= =) and (=) have distinct meanings:

x = 5; Assigns a value of 5 to x; whereas

x == 5; Checks to determine if x = 5

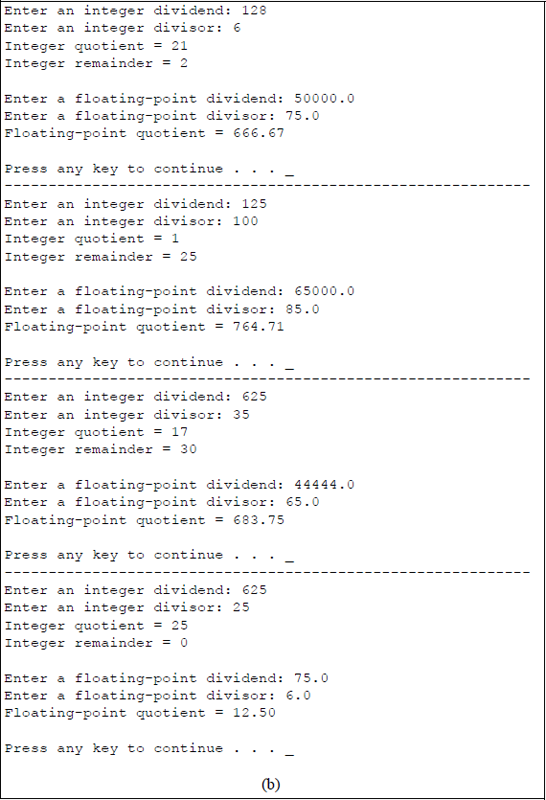

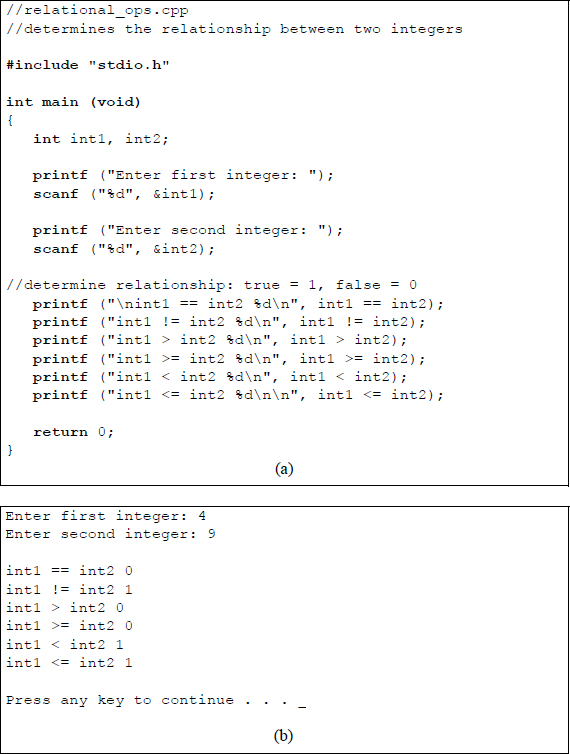

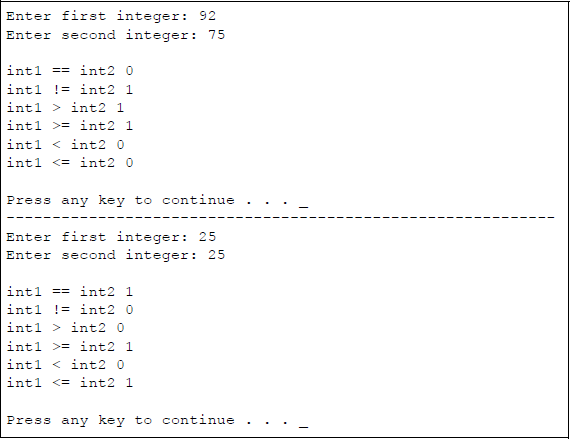

An expression generated by relational operators is also referred to as a relational expression. Relational operators are placed between the expressions that are being compared. The program shown in Figure 4.25 provides an example of utilizing the six relational operators. The user is prompted to enter two integers, then the program applies the relational operators to determine the relationship between the integers.

Program to illustrate using the relational operators: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

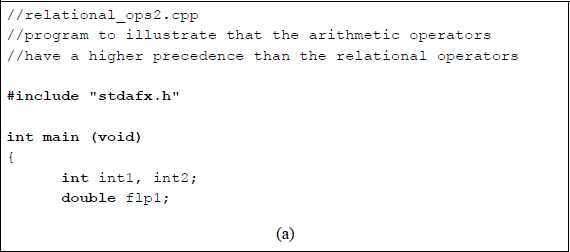

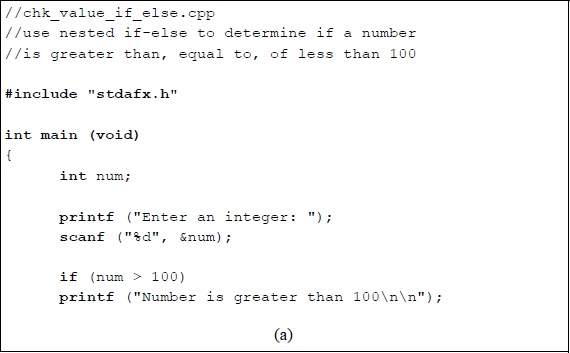

As a final example on relational operators, the program in Figure 4.26 illustrates that the arithmetic operators have a higher precedence than relational operators.

Program to illustrate using the relational operators: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

4.4.3 The If Statement

Conditional statements, such as the if statement, alter the flow within a program based on certain conditions. The if statement is also referred to as a program control statement, a selection statement, or a decision statement. The if statement makes a decision based on the result of a test. The choice among alternative statements depends on the Boolean value of an expression. The alternative statements can be a single statement or a block of statements. The syntax for the if statement is shown below, where a true value is 1 or any nonzero value; a false value is 0. If the expression is true, then the statement, or block of statements, is executed; if the expression is false, then the statement, or block of statements, is not executed, then the next statement in the program flow is executed.

if (expression/condition)

{statement or block of statements}

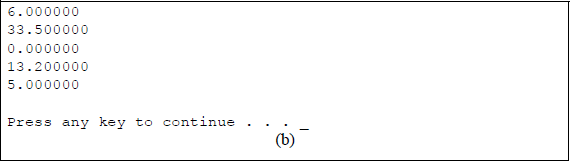

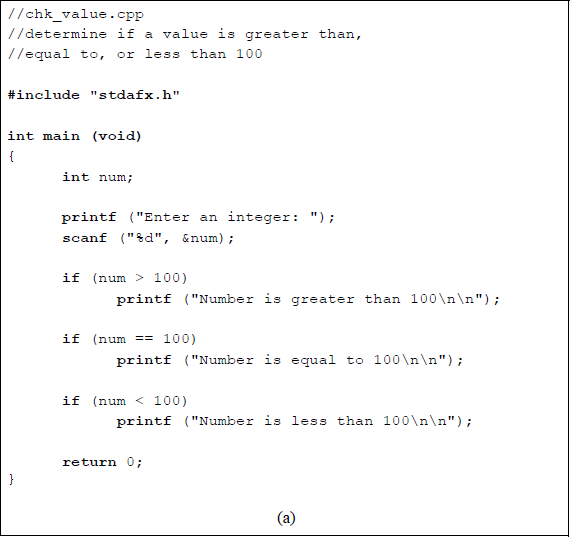

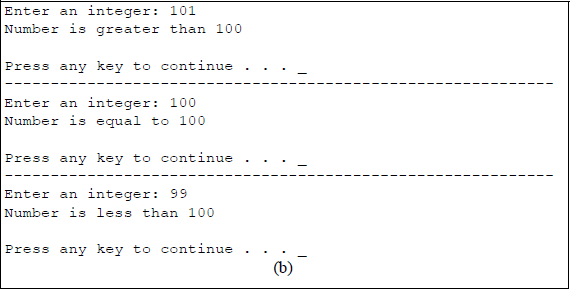

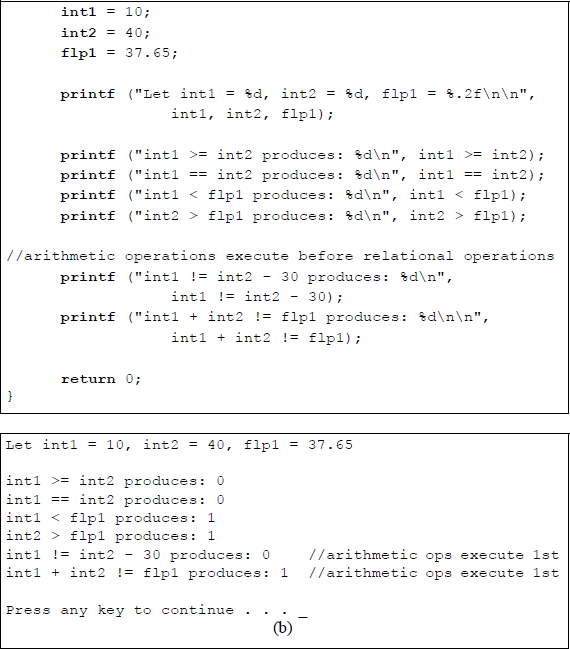

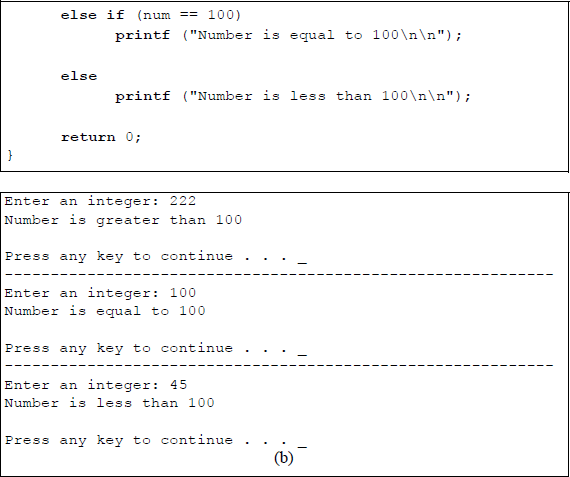

Figure 4.27 illustrates an example of a C program to determine if an integer entered by the user is greater than, equal to, or less than 100. This program requires three if statements, one for each comparison.

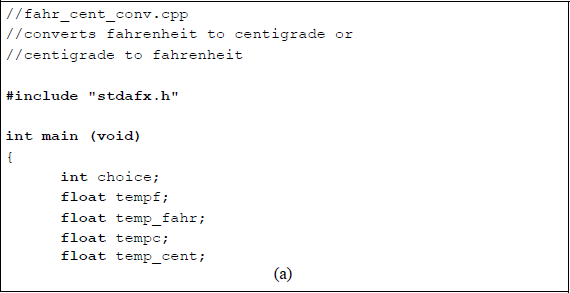

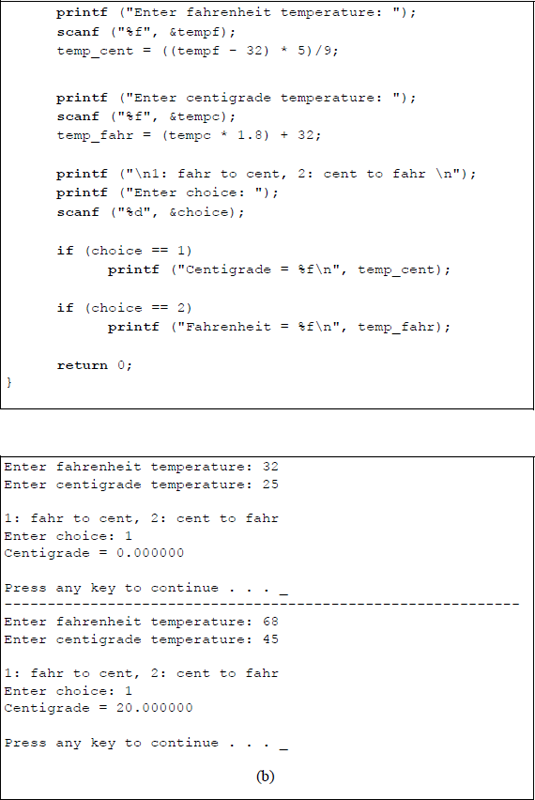

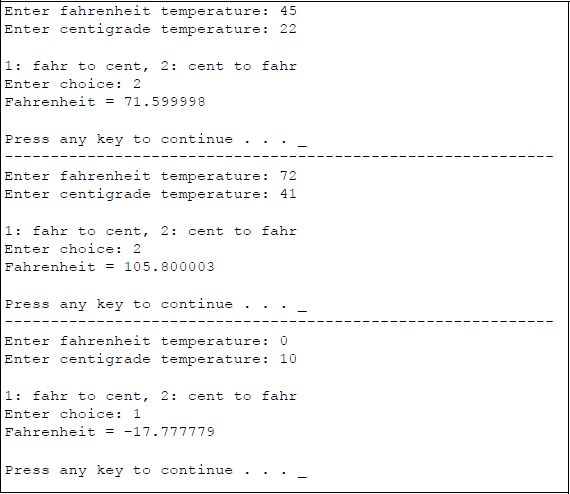

A final example to illustrate the if statement is shown in Figure 4.28, which converts Fahrenheit to centigrade or centigrade to Fahrenheit, depending on the user's request. The conversion equations are shown.

4.4.4 The Else Statement

The else statement is used in conjunction with the if statement to provide alternative paths through the program. The syntax for the conditional branching if-else construct is shown below. When the if expression is true, then the statement(s) following the if statement will be executed. When the if expression is false, then the statement(s) contained in the else block are executed.

if (expression/condition)

{statement or block of statements}else

{statement or block of statements}

The statement(s) in the if block will be executed only when the condition is true (1). However, when the condition is false (0), the else statement(s) will be executed. When the if expression/condition returns a true value, then the statements in the else block are not executed. This technique provides a two-way decision path.

A variation of the if-else construct is the nested if statements in which only one block of statements is executed. The syntax is shown below. If expression_1 is true, then statement_1 (or block of statements) is executed and the program exits the nested if statements. If expression_1 is false and expression_2 is true, then statement_2 (or block of statements) is executed and the program exits the nested if statements. If expression_2 is false, then the program executes statement_3 (or block of statements).

if (expression_1/condition_1)

{statement_1 or block of statements}else if (expression_2/condition_2)

{statement2 or block of statements}else {statement_3 or block of statements}

The program of Figure 4.27 will be redesigned using the nested if technique to determine if a number that is entered from the keyboard is greater than, equal to, or less than 100. The program is listed in Figure 4.29.

Program to illustrate using the nested if statement: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

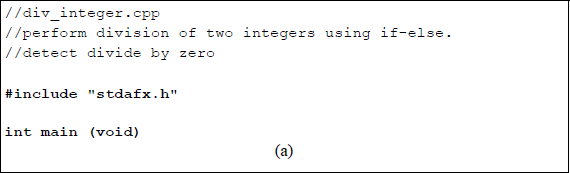

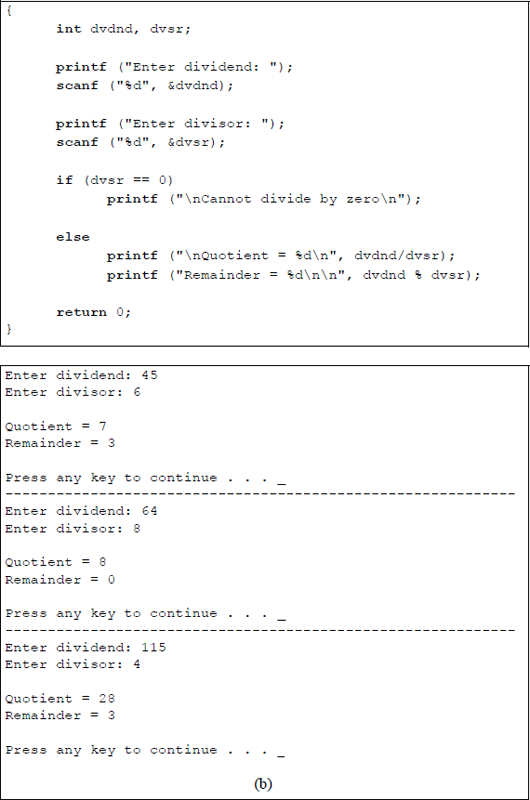

The program shown in Figure 4.30 depicts an example of integer division. If the divisor is zero, then the division operation is invalid. The user is requested to enter a dividend and a divisor. If the divisor is not zero, then the divide operation is performed; otherwise, a message is displayed stating that division by zero is invalid.

Program to illustrate using the if-else construct for a divide operation: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

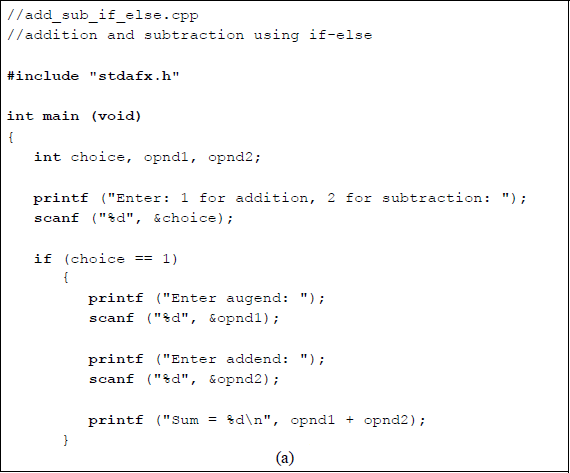

As a final example in this section, Figure 4.31 provides an example illustrating using the if-else construct to either add two operands or subtract two operands. For addition, the addend is added to the augend; for subtraction, the subtrahend is subtracted from the minuend. The variable named opnd1 is the augend/minuend; the variable named opnd2 is the addend/subtrahend. If the user enters a choice of 1, then the operation is addition; otherwise, the operation is subtraction. The blocks of code for the if statement and the else statement are delimited by beginning and ending braces.

Program to illustrate using the if-else construct for addition and subtraction operations: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

4.4.5 Logical Operators

There are three logical operators, as shown in Table 4.10. The AND operation evaluates as true (1) only if both expression 1 AND expression 2 are true; otherwise, it evaluates as false (0). The OR operation evaluates as true (1) if either expression 1 OR expression 2 is true; it evaluates as false (0) if both expressions are false. The OR operator is also referred to as the inclusive OR; the exclusive OR is discussed later. The NOT operation evaluates as false (0) if expression 1 is true; otherwise, it evaluates as true (1) if expression 1 is false. Table 4.11 is a truth table that illustrates the three logical operators using binary values.

Logical Operators

Operator Symbol |

Operation |

Example |

&& |

AND |

expression 1 && expression 2 |

| | |

OR |

expression 1 | | expression 2 |

! |

NOT |

! expression 1 |

Truth Table for the Logical Operators

x1 |

x2 |

x1 && x2 |

x1 | | x2 |

! x1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

Logical operators can be combined with relational operators to form a single expression that evaluates to either true (1) or false (0). When used in this context, they are sometimes referred to as compound relational operators. When relational and logical operators are combined, relational operators have a higher precedence. Logical operators are used with expressions, not with individual bits — individual bits are evaluated using bitwise operators. The arithmetic operators have a higher precedence than the relational operators, which have a higher precedence than the logical operators. The precedence of relational and logical operators is shown in Table 4.12.

Precedence of Relational and Logical Operators

Operator Symbol |

Precedence |

|---|---|

! |

Highest |

>, >=, <, <= |

|

= =, ! = |

|

&& |

|

| | |

Lowest |

Relational and logical operators can be used in if statements. For example, in the statement shown below, since the first expression is true, C will not evaluate the second expression. This is because a logic 1 ORed with anything will generate a logic 1 regardless of the value of the second expression.

if (10 > 9) || (2 > 1)

In a similar manner, in the statement shown below, since the first expression is false, C will not evaluate the second expression. This is because a logic 0 ANDed with anything will generate a logic 0 regardless of the value of the second expression.

if (10 < 9) && (1< 2)

The exclusive-OR function is defined for two variables x1 and x2 as shown below; that is, only when the variables are different will a logic 1 be generated.

The C programming language does not provide an exclusive-OR operator; however, the function can be easily obtained by utilizing the logical operands && and | | , as follows:

(x1 && ! x2) || (! x1 && x2)

Examples of logical operators are shown below together with the resulting evaluation.

Expression |

Evaluates as |

|---|---|

(14 = = 14) && (20 != 10) |

True (1), because both expressions are true |

(20 > 10) | | (15 < 10) |

True (1), because one expression is true |

(10 = = 10) && (30 < 20) |

False (0), because one expression is false |

!(10 = = 15) |

True (1), because the expression is false |

(30 > 10) && (20 = = 20) |

True (1), because both expressions are true |

!(10 = = 10) |

False (0), because the expression is true |

!(20 > 10) && (30 = = 30) |

False (0), because both expressions are true |

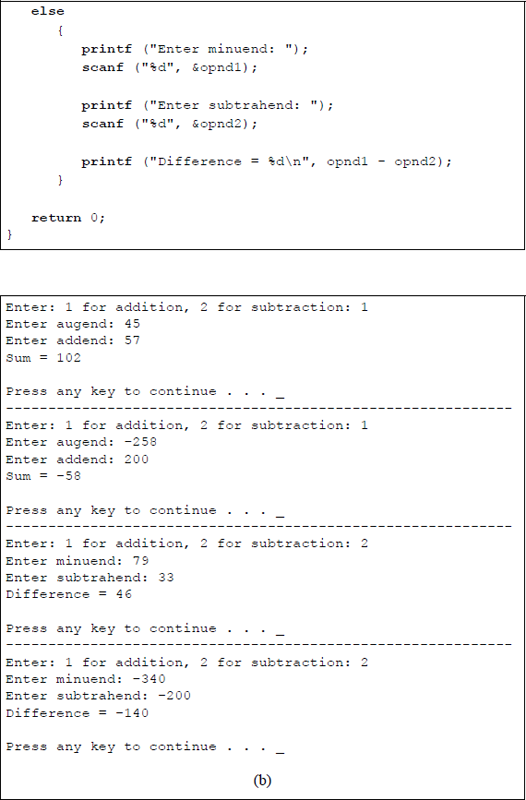

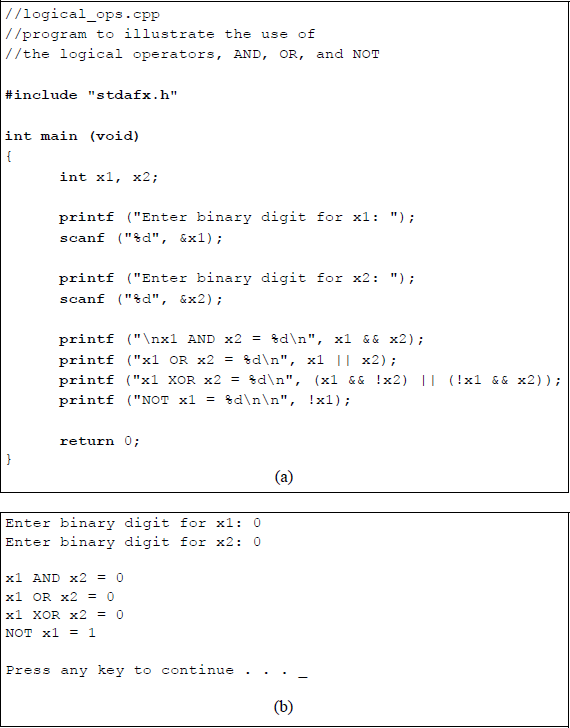

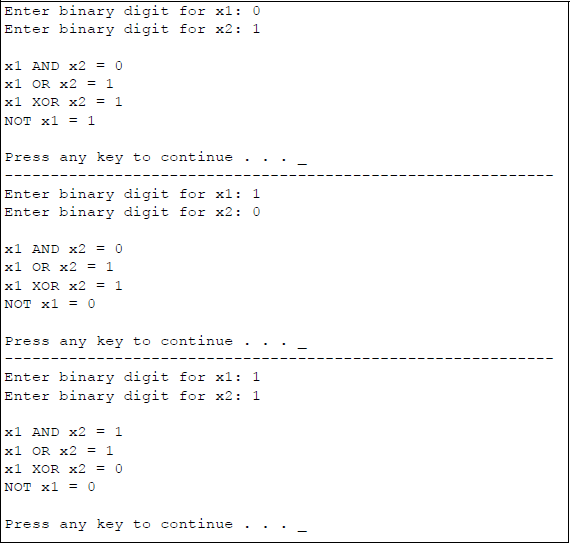

Figure 4.32 shows a program to illustrate the logical operators, including the exclusive-OR function. The user enters two binary digits and the program performs the appropriate logical operations. All combinations of two variables are entered.

Program to illustrate using the logical operators: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

4.4.6 Conditional Operator

The conditional operator (? :) has three operands, as shown in the syntax below. The conditional_expression is evaluated. If the result is true (1), then the true_expression is evaluated; if the result is false (0), then the false_expression is evaluated.

conditional_expression ? true_expression : false_expression;

The conditional operator can be used when one of two expressions is to be selected. For example, in the statement below, if x1 is greater than or equal to x2 , then z1 is assigned the value of x3 ; if x1 is less than x2 , then z1 is assigned the value of x4.

z1 = (x1 >= x2) ? x3 : x4;

Since the conditional operator selects one of two values, depending on the result of the conditional_expression evaluation, the operator can be used in place of the if-else construct. Conditional operators can be nested; that is, each true_expression and false_expression can be a conditional operation, as shown below.

conditional_expression ? (cond expr1 ? true expr1 : false expr1)

: (cond expr2 ? true expr2 : false expr2);

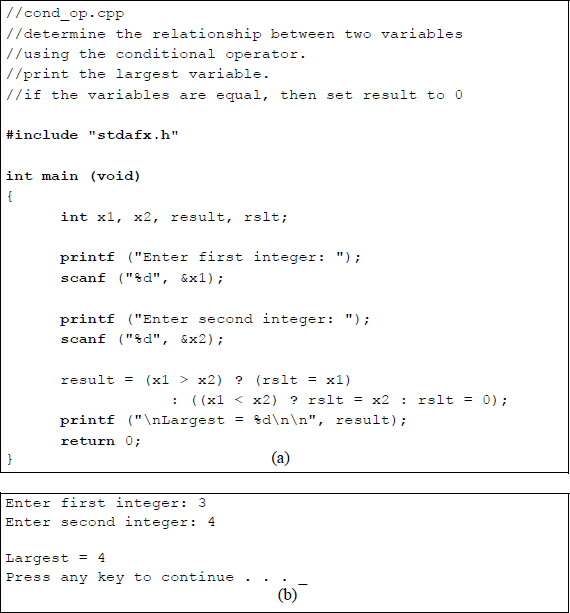

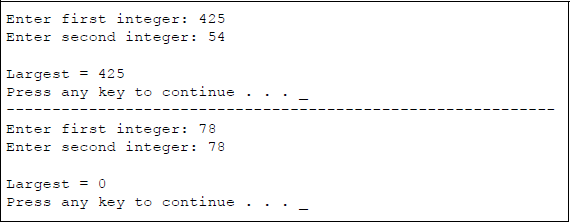

The program shown in Figure 4.33 illustrates a method to determine whether one integer is less than, equal to, or greater than the other integer using the conditional operator.

Program to illustrate using the conditional operator: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

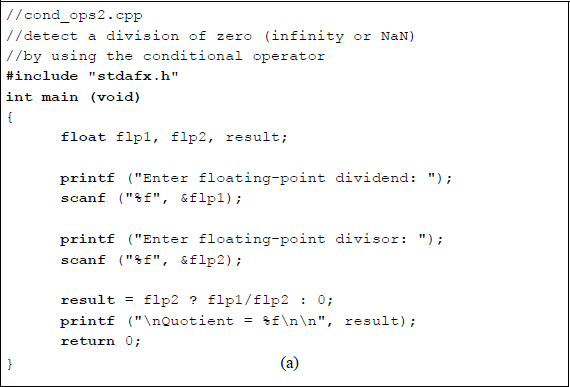

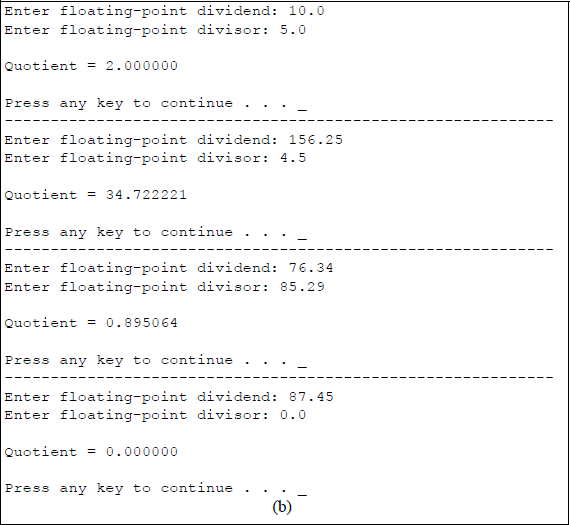

As a final example in this section, consider the program listed in Figure 4.34, which detects a division by zero. Division by zero generates a result of infinity or Not a Number (NaN). Most calculators will display an error message when an attempt is made to divide by zero, because division of any number by zero is not defined. A NaN is a value that is unrepresentable in floating-point calculations and is defined in the IEEE 754-1985 (Reaffirmed 1990) floating-point standard.

Program to illustrate using the conditional operator to detect a division by zero: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

4.4.7 Increment and Decrement Operators

There are four versions of the increment and decrement operators, as shown below. The increment/decrement operators are unary operators and can be placed before or after the variable — they cannot be used with constants.

Prefix Mode |

Postfix Mode |

||

|---|---|---|---|

+ + x |

Increment operand x before it is used |

x + + |

Increment operand x after it is used |

– – x |

Decrement operand x before it is used |

x – – |

Decrement operand x after it is used |

The increment operator An example of a preincrement operator is shown below. After execution, x = 11 and y = 11; that is, x was incremented, then its value was assigned to y.

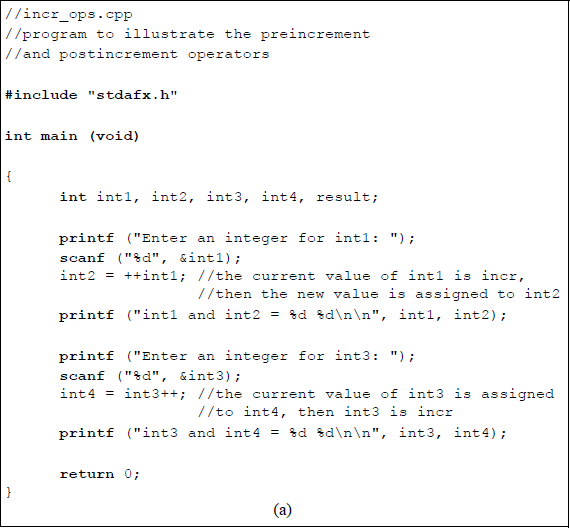

An example of a postincrement operator is shown below. After execution, x = 11 and y = 10; that is, the value of x was assigned to y, then x was incremented. The program shown in Figure 4.35 illustrates using the preincrement and postincrement operators.

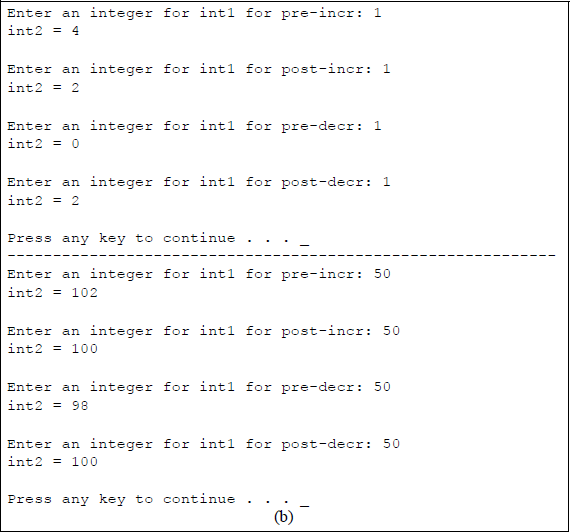

Program to illustrate using the preincrement and postincrement operators: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

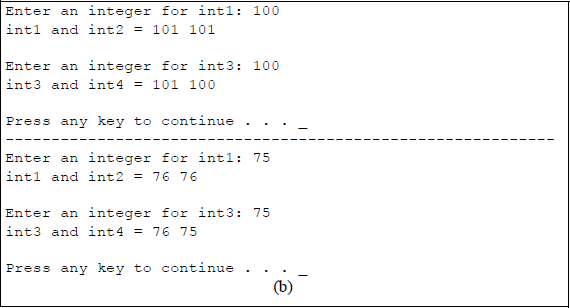

The decrement operator An example of a predecrement operator is shown below. The current value of x is decremented, then the new value is assigned to y. After execution, x = 9 and y = 9; that is, x was decremented, then its value was assigned to y.

An example of a postdecrement operator is shown below. After execution, x = 9 and y = 10; that is, the value of x was assigned to y, then x was decremented. The program shown in Figure 4.36 illustrates using the predecrement and postdecrement operators.

Program to illustrate using the predecrement and postdecrement operators: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

As can be seen in both the programs of Figure 4.35 and Figure 4.36, there is only one operand utilized in the unary arithmetic operators. An expression cannot be incremented or decremented, thus the statement shown below is invalid.

z = ++(x * y);

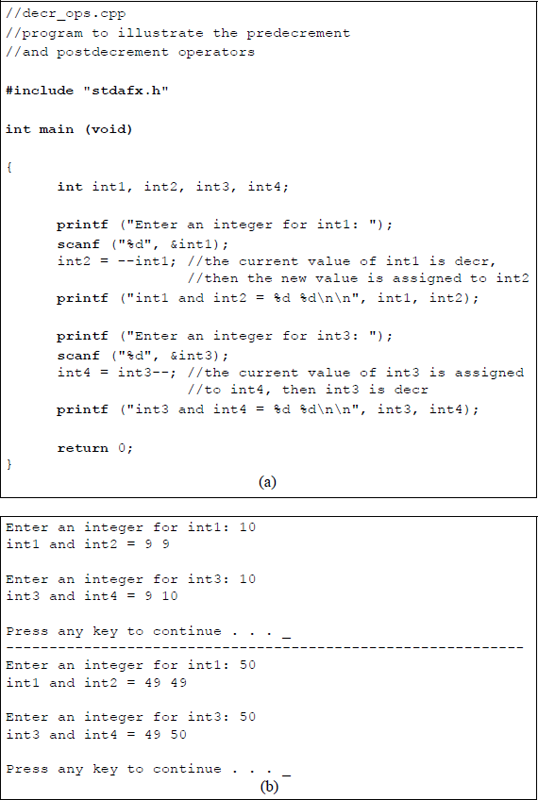

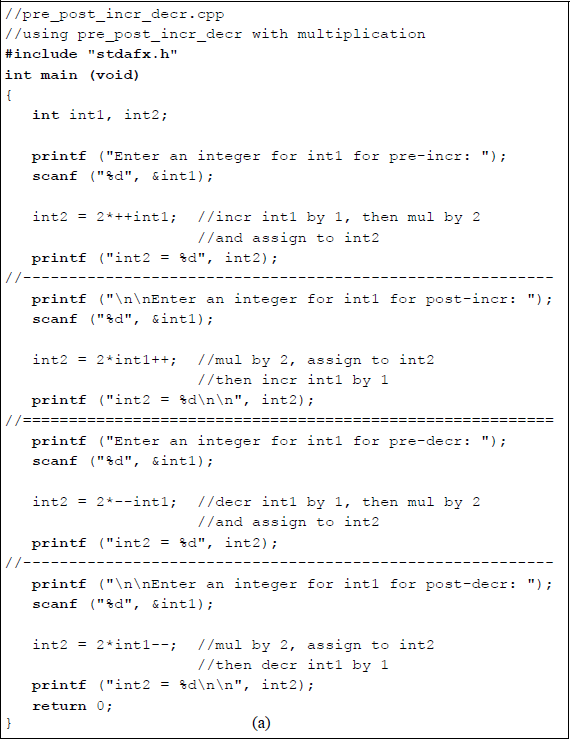

As a final example in this section, the program shown in Figure 4.37 illustrates using the unary increment/decrement operators with the binary multiplication operator. Note that parentheses are not required for the prefix unary operators when used with the binary operator, because the prefix operators have a higher precedence than the multiplication operator in a left-to-right sequence.

Program to illustrate using the pre/postincrement and pre/postdecrement operators with the multiply operator: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

4.4.8 Bitwise Operators

There are three bitwise operators: AND, OR, and the exclusive-OR, that operate on the individual bits of two operands; the NOT operator performs the 1s complement on one operand. The operators (or symbols) used for the bitwise operations and the corresponding function definitions are listed in Table 4.13. Table 4.14 illustrates the truth tables for the bitwise operators, where z1 is the result of the operation.

Boolean Operators for Variables x1 and x2

Operator |

Function |

Definition |

|---|---|---|

& |

AND |

x1 & x2 |

| |

OR |

x1 | x2 |

^ |

Exclusive-OR |

x1 ^ x2 = (x1 x2′) + (x1′ x2) |

~ |

NOT (1s complement) |

~x1 |

Truth Table for AND, OR, Exclusive-OR, and NOT

AND |

OR |

Exclusive-OR |

NOT |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

x1 x2 |

z1 |

x1 x2 |

z1 |

x1 x2 |

z1 |

x1 |

z1 |

0 0 |

0 |

0 0 |

0 |

0 0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 1 |

0 |

0 1 |

1 |

0 1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 0 |

0 |

1 0 |

1 |

1 0 |

1 |

||

1 1 |

1 |

1 1 |

1 |

1 1 |

0 |

||

The AND operator corresponds to the Boolean product and generates a logic 1 output if both bits are a logic 1; otherwise a logic 0 is generated. The OR operator corresponds to the Boolean sum and generates a logic 1 output if either or both bits are a logic 1 — if both bits are a logic 0, then a logic 0 is generated. The exclusive-OR operator generates a logic 1 if both bits are different — if both bits are the same, then the output is a logic 0.

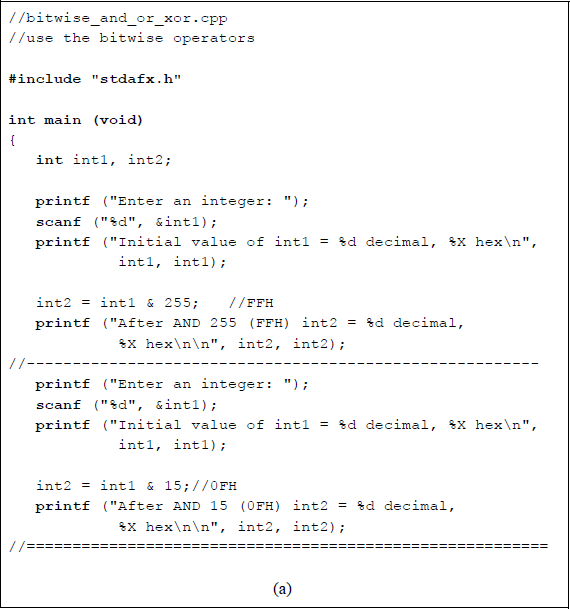

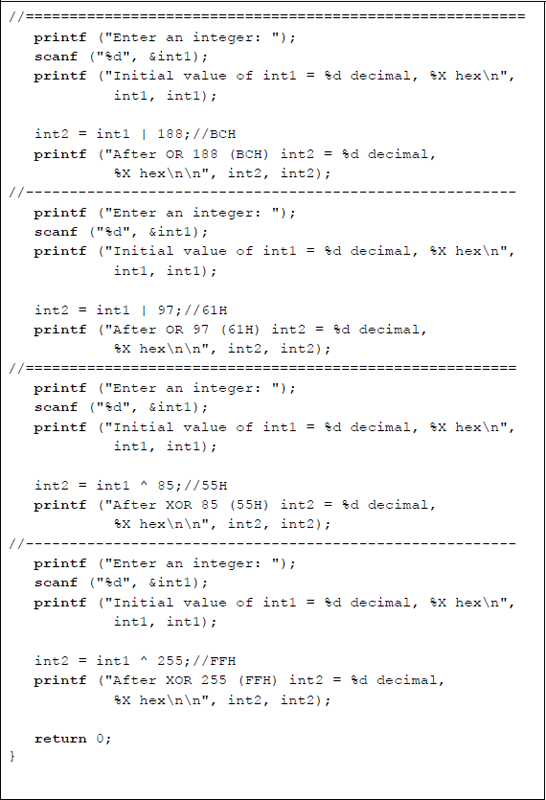

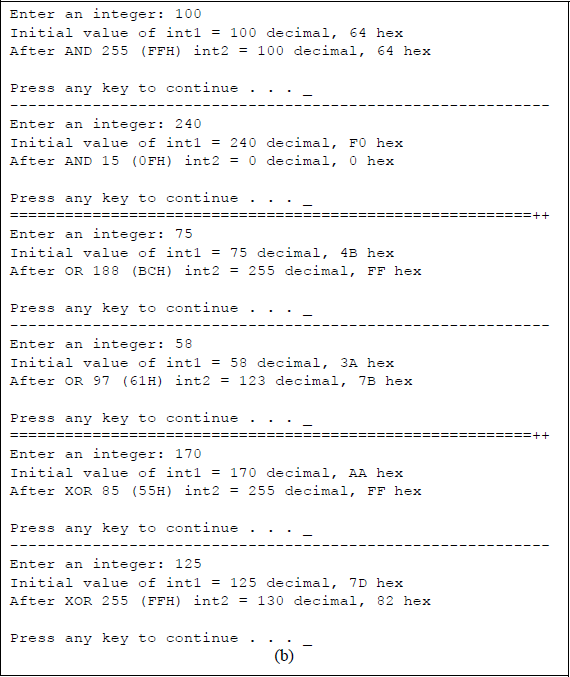

The program shown in Figure 4.38 illustrates using the three bitwise operators of AND, OR, and exclusive-OR for various user-generated inputs. Integers are entered by the user and the values are displayed in both decimal and hexadecimal number representations. The bitwise operator is then executed and the result is displayed in both decimal and hexadecimal.

Program to illustrate using the bitwise operators of AND, OR, and exclusive-OR: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

For the first AND operation, a value or 10010 (6416) was entered. This value was ANDed with 25510 (FF16), as shown below, to yield a result of 10010 (6416). Thus, the initial value was unchanged, since 1 & 1 = 1 and 1 & 0 = 0.

For the second OR operation, a value or 5810 (3A16) was entered. This value was ORed with 9710 (6116), as shown below, to yield a result of 12310 (7B16). Thus, the initial value was changed, since 1 | 1 = 1 and 1 | 0 = 1.

For the second exclusive-OR operation, a value or 12510 (7D16) was entered. This value was exclusive-ORed with 25510 (FF16), as shown below, to yield a result of 13010 (8216). Thus, the initial value was changed, because the result is a logic 1 only when the bits being exclusive-ORed are different. The NOT operator produces the 1s complement of the operand. This will be left as a problem in which a program is written to illustrate the operation of the NOT operator.

4.5 While Loop

The while loop (or while statement) executes a statement or block of statements as long as a test expression is true (nonzero). The statements that are controlled by the while statement loop repeatedly until the expression becomes false (0). If a block of statements is executed, then the block is delimited by beginning and ending braces; for a single statement, braces are not required. The syntax for the while loop is shown below. The expression is checked at the beginning of the loop and may contain relational and logical operators.

while (expression)

{block of statements}

The statements in the block must change the value of the expression, since this determines the duration of the loop. If the expression does not change (always true), then the loop would never stop, resulting in an infinite loop. When the expression becomes false (0), the program exits the loop and transfers control to the first statement following the block of statements. If the expression is initially false, then the block is not executed.

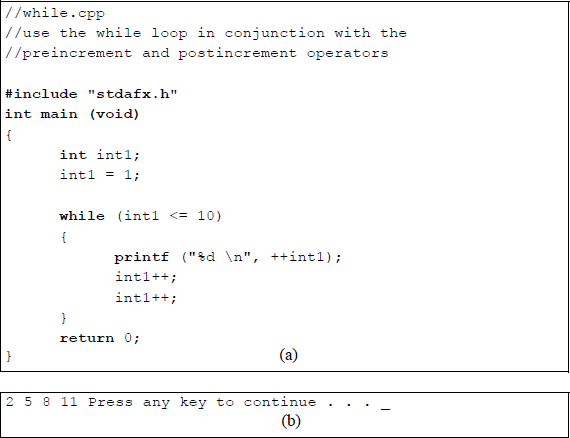

Figure 4.39 shows a simple program that uses the while statement in conjunction with the preincrement and postincrement operators. The while loop adds 3 to the integer int1 during each iteration of the loop. The integer int1 is initially assigned a value of 1. The printf () argument adds 1 to int1 in the preincrement mode, increasing int1 to 2. Then the two postincrement operators add 2 to int1, increasing int1 to 4. At the next iteration of the loop, the printf () function increases int1 to a value of 5.

Program to illustrate using the while loop with the preincrement and postincrement operators: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

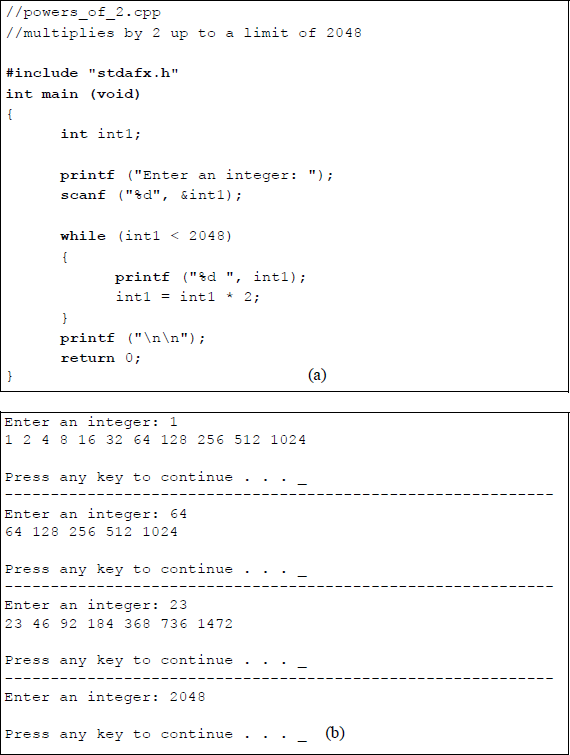

The program shown in Figure 4.40 illustrates the while loop to multiply an integer from the keyboard by 2 until the number becomes equal to or greater than 2048. The integer int1 is defined as a local variable, is printed, then multiplied by 2. This process repeats until the value reaches or exceeds 2048.

Program to illustrate using the while loop to multiply by 2 up to a limit of 2048: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

4.6 For Loop

The for loop repeats a statement or block of statements a specific number of times. This is different than the while loop, which repeats the loop as long as a certain condition is met. When the for loop has completed the final loop, the program exits the loop and transfers control to the first statement following the block of statements. The syntax for the for loop is shown below.

for (initialization; conditional test; increment)

{one or more statements}

The initialization step sets a variable to a specific value; this is the loop control variable and is executed only once. The conditional test is performed at the start of the loop to determine if the loop should be entered. This is usually a relational expression that tests the loop control variable against a target value. If the test is true (nonzero), then the loop is entered; otherwise, the loop is exited and the next instruction following the loop is executed. The increment step is performed at the end of the loop; this can also be a decrement depending on the initialization and conditional test.

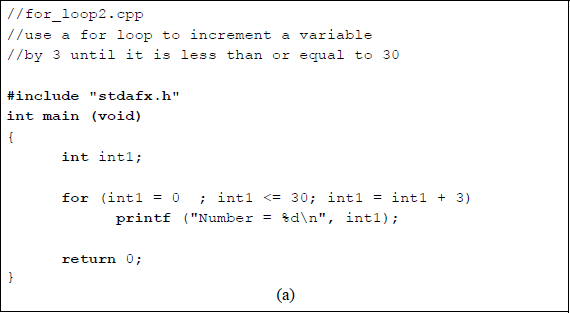

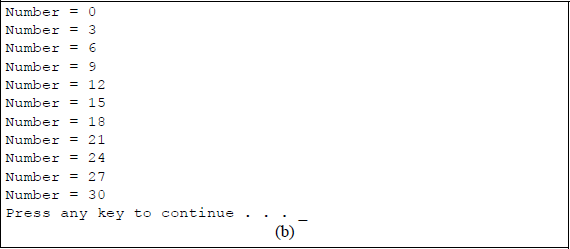

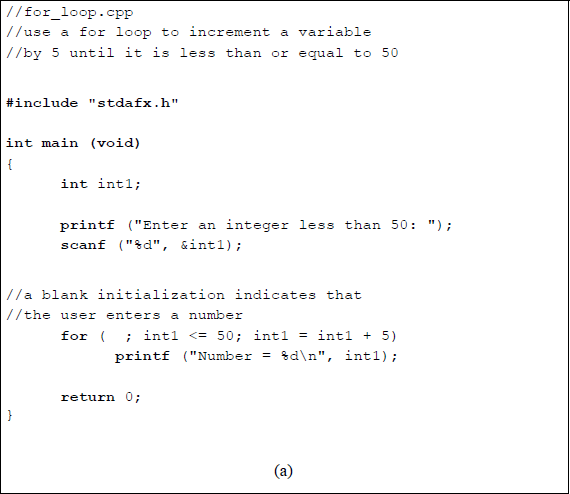

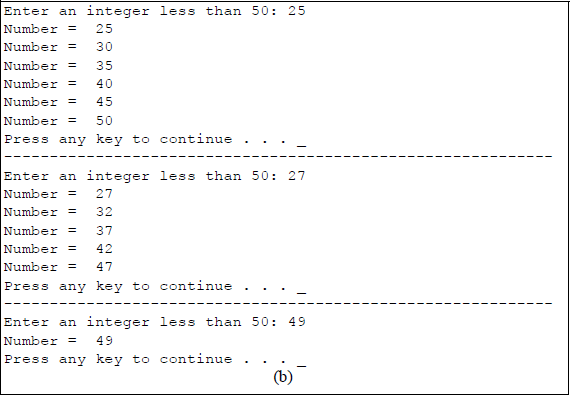

Figure 4.41 and Figure 4.42 show two examples of using a for loop to increment an integer. Figure 4.41 has no user input. The integer int1 is initialized to a value of 0; the loop continues until the value is equal to or less than 30; the integer is incremented by 3 at the beginning of the loop. Figure 4.42 requires a user input. A space for the initialization step of the for loop indicates that a user input is required. An integer is entered for the initialization step and is stored in location int1. The conditional test specifies an end result of less than or equal to 50; the integer is incremented by 5 at the beginning of the loop.

Program to illustrate using the for loop to increment a variable by 3 up to a limit of less than or equal to 30: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

Program to illustrate using the for loop to increment a variable by 5 up to a limit of less than or equal to 50: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

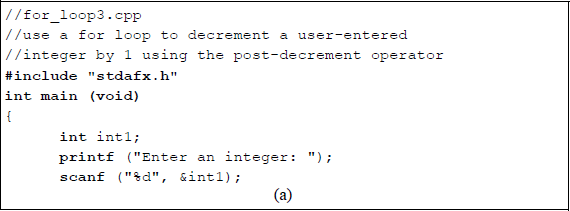

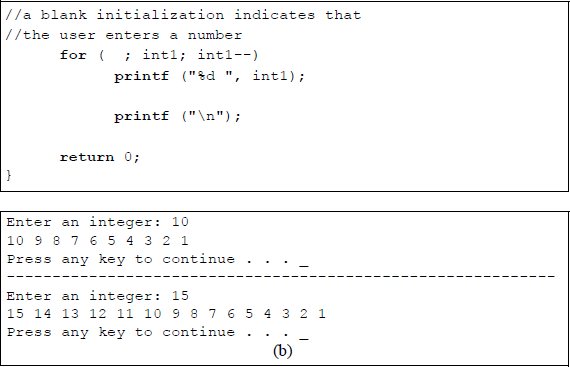

As a final example, the program shown in Figure 4.43 illustrates a for loop consisting of a user-entered integer and the postdecrement operator, which decrements the integer by 1. As long as the integer int1 is nonzero, as determined by the conditional test, the looping continues. When the value of int1 reaches a value of zero, the program exits the loop. The printf ("\n"); simply places the cursor at the beginning of a new line. Since there is only one statement in the for loop, braces are not required.

Program to illustrate using the for loop to postdecrement a variable by 1 until its value is 0: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

4.7 Additional C Constructs

This section gives a short introduction to arrays, strings, pointers, and functions. Arrays are one-dimensional or multidimensional structures that contain a series of elements of a specific data type; that is, an array is a list of variables with the same name. The declaration and initialization of arrays is discussed in which arrays are used to declare a set of variables of the same data type.

Strings are usually one-dimensional character arrays that are terminated with a null character (\ 0) — the null character is automatically appended to the end of the string by the compiler to mark the end of the string. Strings are part of the printf () function and are contained in the format_string and conversion section of the print function.

Pointers are variables that address (or point to) a memory location where a data type is stored. The memory location can be selected by the pointer to access or modify the data. Pointers provide an effective method to access arrays.

A function is an independent procedure (or subroutine) which is invoked by a calling function. The invoked function receives arguments from the calling program, performs specific operations on the arguments, then returns the results to the calling program. A function is identified by a pair of parentheses. Functions are useful in avoiding repetitive programming — a function can be defined once then used by several invoking functions.

4.7.1 Arrays

An array can be initialized by simply listing the array elements, as shown below together with examples. The type can be char, int, float, double, or any valid C type. The value list is a sequence of constants that are the same type as the array_name type and enclosed in braces.

type array_name [size] = {value list};

int array[5] = {1, 4, 9, 16, 25};

char array[3] = {'A', 'B', 'C'};

The size of the array does not have to be specified, as shown below for an array of eight elements — the compiler creates the array based upon the number of elements. The length of the array is one element longer than the value list; the compiler supplies the null terminator.

int powers[] = {1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128};

An array is an ordered structure, in which the location of the individual elements is known. An array is homogeneous; that is, every element is of the same type. The array can be an array of integers, an array of floating-point numbers, or an array of any other data types — array types cannot be mixed. An automatic array is an array that is defined inside the main () function. An external array is defined outside a function, usually before main (). A static array is defined inside a function with the keyword static, but retains its values between function calls.

One-dimensional array A one-dimensional array is declared as shown below, where the type is a valid C type, var_name is the name of the array, and size is the number of elements in the array. An example of a one-dimensional array of type int, called array with 20 elements, is also shown below.

type var_name [size]

int array [20]

Arrays start at element 0; therefore, the second element is accessed as follows: array [1]. The first element of the array can be set to a value of 200 by the following statement: array [0] = 200. One-dimensional arrays are stored in contiguous memory locations, with the first array element at the lowest address.

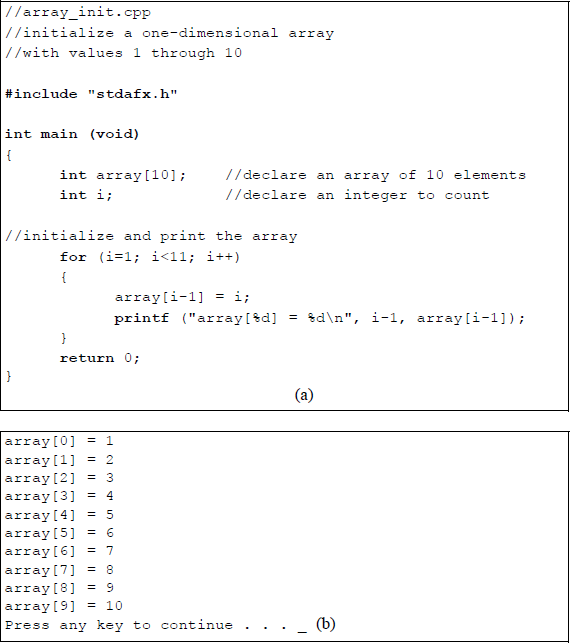

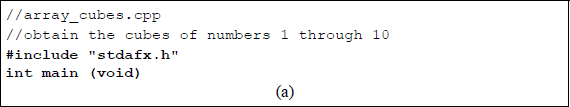

Figure 4.44 illustrates a method to initialize a one-dimensional array with ten elements to values 1 through 10. The integer i is set to a value of 1 in the for loop, then the first element (array[i–1]), which is array[0], is set to a value of 1 by the following statement: array[i–1] = i; that is, array[0] = 1. The array is then printed, where the first element (i–1) is assigned the value of array[i–1], which is the contents of the first element — a value of 1. A similar structure is shown in the program of Figure 4.45, which generates the cubes of integers 1 through 10.

Program to illustrate initializing and printing a one-dimensional array: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

Program to illustrate an array to obtain the cubes of integers 1 through 10: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

Two-dimensional array A two-dimensional array has the syntax shown below for a 10 × 12 array, where the type is int, the array name is count, the number of rows is 10, and the number of columns is 12.

int count [10][12];

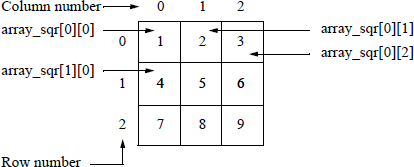

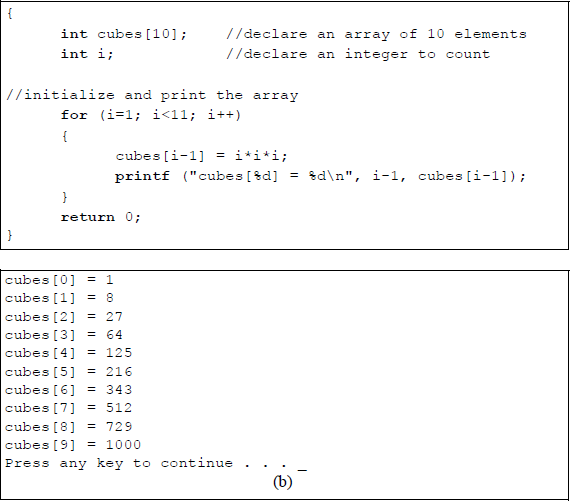

A two-dimensional array is an array of one-dimensional arrays that is accessed one row at a time from left to right. The rightmost index (columns) will change faster than the leftmost index (rows). Figure 4.46 shows a 3 × 3 array consisting of nine elements with addresses for select elements. Figure 4.47 shows a program to initialize and print the two-dimensional array of Figure 4.46 using nested for loops. The array elements can also be listed in a single line. The row index does not have to be specified — C will index the array properly. This permits the construction of arrays of varying lengths; the compiler allocates storage automatically.

Program to illustrate initializing and printing a two-dimensional array: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

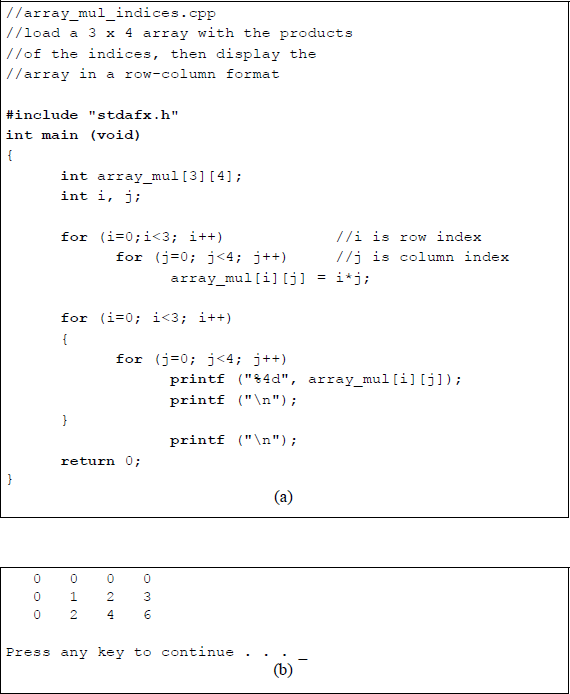

Figure 4.48 illustrates a program that loads a 3 × 4 array with the products of the indices, then displays the array in a row–column format. This program also uses nested for loops. Note that a for loop block that has only one statement does not require delimiting braces. Integers i and j represent the row and column indices, respectively.

Program to illustrate loading a 4 × 5 array with the product of the indices then printing the array: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

4.7.2 Strings

A string is a one-dimensional character array that is terminated by a null character (\ 0). The string can be defined to be a certain length and must include the null character as part of the overall length. There are many library functions that apply to strings, including input/output functions. The following string functions are described in this section: gets (), puts (), strcpy (), strcat (), strcmp (), and strlen ().

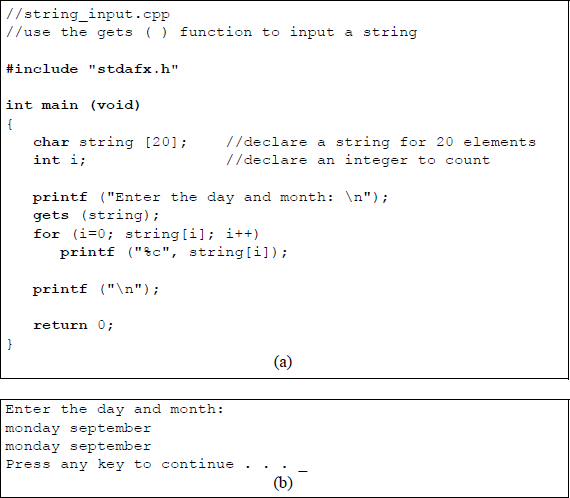

Gets () The gets (string) function stores input data — primarily from the keyboard — into the string named string. The gets () function inputs the string data until a new-line (\ n) character is detected, which is generated by pressing the Enter key. The gets () function discards the newline character and adds the null character (\ 0) or (0016), which indicates the end of the string. The length of the string array must be large enough to hold the entire string, because the bounds of the string are not checked. Figure 4.49 shows a simple program to illustrate the use of the gets () function.

Program to illustrate using the gets () function: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

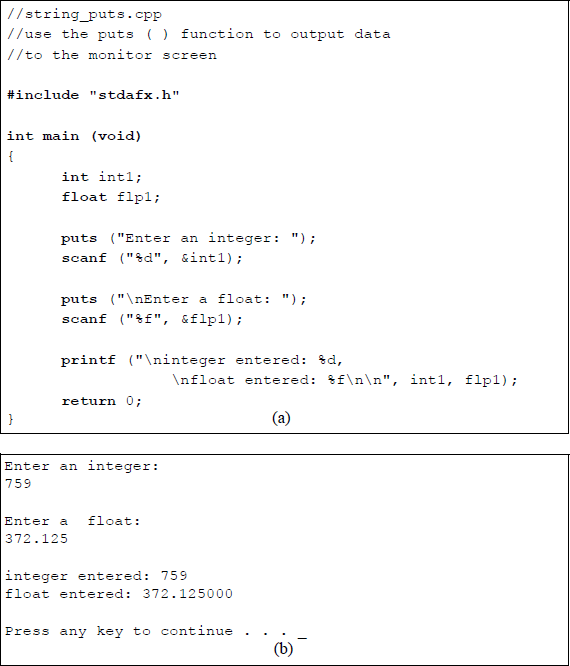

Puts () The puts () function displays text on the monitor screen and automatically adds a newline character (\ n) at the end of the string; therefore, a newline character does not have to be inserted by the programmer. When a string is to be output to the screen, the puts () function is faster than the printf (). The program shown in Figure 4.50 illustrates the use of the puts () function to tell the user to enter an integer number followed by a floating-point number. The numbers are read by the scanf () function and displayed on the screen by the printf () function.

Program to illustrate using the puts () function: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

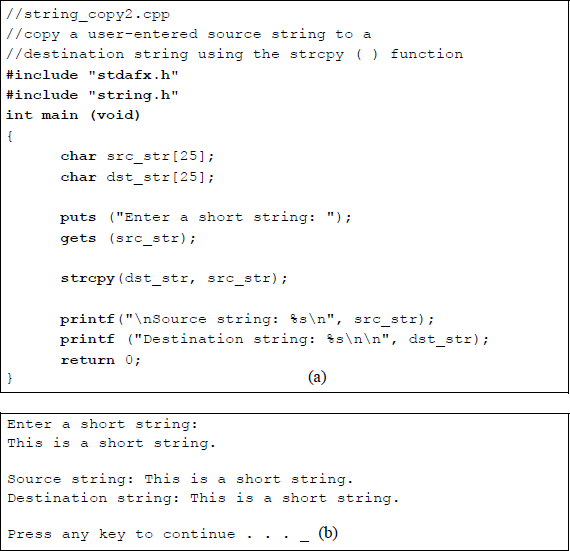

Strcpy () The strcpy () function copies the source string to the destination string, including the null character (\ 0). Both the source and destination strings are arrays. Since the strcpy () function does not perform bounds checking on the destination string, the destination array must be of sufficient length to accommodate the source string plus the terminating null character. The syntax for the strcpy () function is shown below.

strcpy (destination_string, source-string);

Figure 4.51 shows a program that illustrates a user-entered source string being copied to a destination string. The "string.h" header is required in order to make some string operations valid. The gets () function stores the keyboard input string into the source string src_str, which is initialized to 25 characters. This is then transferred to the destination string dst_str, also initialized to 25 characters.

Program to illustrate using the strcpy () function: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

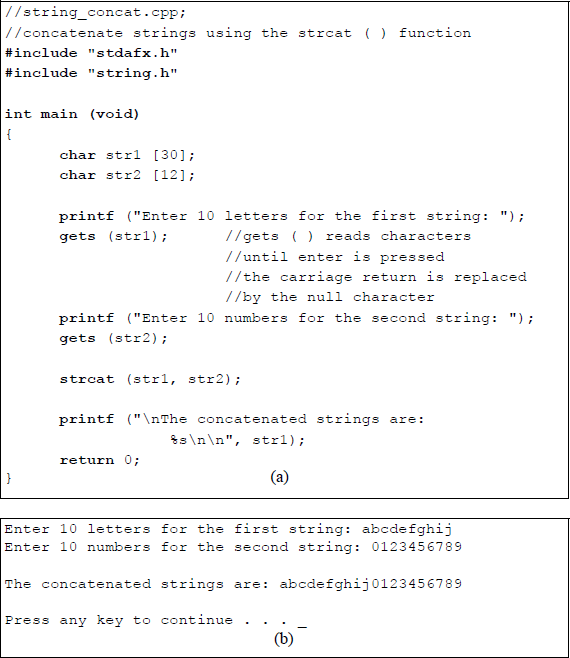

Strcat () String concatenation is performed by the strcat () function, shown in Figure 4.52. The syntax is shown below, containing two arguments: string1 and string2, where string2 is concatenated to the right of string1 to generate a new string. The terminating null character is moved to the right of the new string. The strcat () function performs no bounds checking; therefore, the array of string1 must be of sufficient length to accommodate both strings plus the null character. Figure 4.52 shows a program illustrating the use of the strcat () function.

strcat (string1, string2);

Program to illustrate using the strcat () function: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

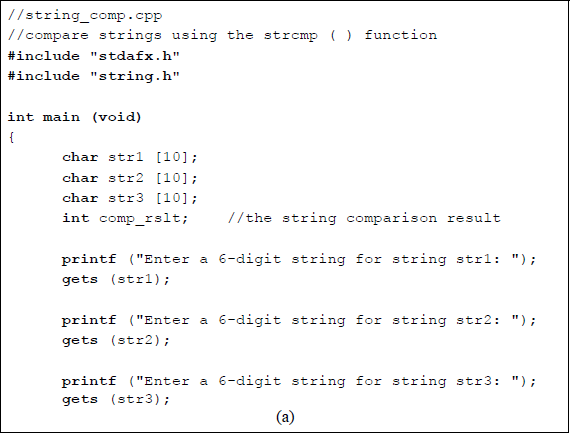

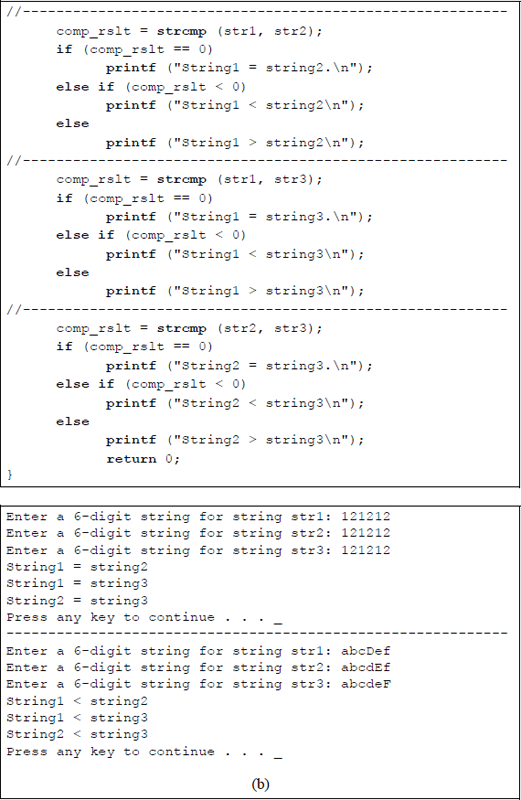

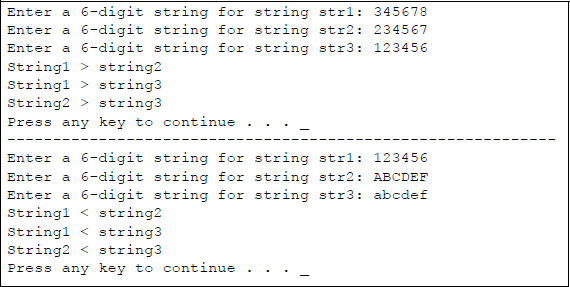

Strcmp () String comparison is performed by the strcmp () function. The syntax is shown below, which contains two arguments: string1 and string2, where string1 is compared to string2. The string arrays do not have to be the same size, because comparison is not based on the length of the strings. The strcmp () function returns a value of 0 if the strings are the same; it returns a value of < 0 if string1 is less than string2; it returns a value of > 0 if string1 is greater than string2.

strcmp (string1, string2);

The strings are compared character by character; that is, lexicographically, as in a dictionary. The comparison is case sensitive and in the same order as shown in the ASCII character code chart in Appendix A for hexadecimal 20 through 7F. Lowercase letters are greater than uppercase letters, because they have a higher decimal value.

Figure 4.53 shows a program illustrating the use of the strcmp () function to compare two strings from a set of three strings. The result of the string comparison is contained in the comp_rslt variable. The value of comp_rslt will be either 0, less than 0, or greater than 0. This is determined by the conditional if, else-if, and else statements. If comp_rslt is equal to zero, then this indicates that string1 is equal to string2; if comp_rslt is less than zero, then this indicates that string1 is less than string2; if comp_rslt is greater than zero, then this indicates that string1 is greater than string2.

Program to illustrate using the strcmp () function: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

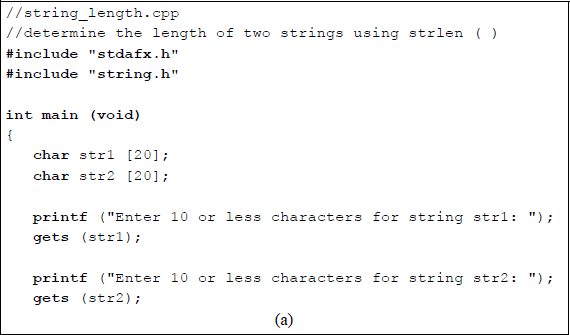

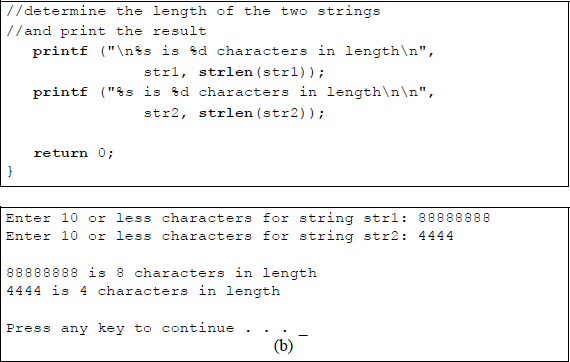

Strlen () The strlen () function returns the length of a string, but does not include the null character. The number of characters defined for the string is irrespective of the length of the string. The syntax for the strlen () function is shown below. Figure 4.54 shows a program illustrating the use of the strlen () function to determine the length of two strings.

strlen (string);

Program to illustrate using the strlen () function: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

4.7.3 Pointers

A pointer is a variable that contains the address of (points to) another variable. The syntax for a pointer declaration is shown below, where type is the type of variable addressed by the pointer, such as char, int, and float, for example. The asterisk is a pointer operator that returns the contents of the variable to which it points — the asterisk, as used here, has a different meaning than the asterisk used for multiplication.

type *pointer_name;

Another pointer operator that was presented previously is the address-of operator (&), which returns the address of the variable. Examples of pointers that return the contents of the variable to which they point are as follows:

char *character_pointer;

int *integer_pointer;

float *flp_pointer;

The asterisk is also referred to as the indirection operator. A simple program to illustrate one use of a pointer is shown in Figure 4.55. The program declares two floating-point variables: a pointer *ptr and a floating-point number flp. The floating-point number, flp, is assigned a value of 75.25 and ptr is assigned the address of flp. The floating-point value is then printed using the *ptr pointer that points to the address of flp, which contains 75.25. Pointers are also an effective way to access arrays, in which the array name is the address of the first element [0] of the array. Pointers used in this manner, however, are beyond the scope of this book.

//pointer_ex.cpp

//program to illustrate the use of a pointer#include "stdafx.h"int main (void)

{

float *ptr;

float flp; flp = 75.25;

ptr = &flp;//print the floating-point value of the variable flp

printf ("Floating-point value of flp: %f\n\n", *ptr); return 0;

}

(a)

Floating-point value of flp: 75.250000Press any key to continue . . . _

(b)

Program to illustrate one use of a pointer: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

4.7.4 Functions

A function is a procedure, or subroutine, that is written once and can be executed several times by calling routines. Functions perform specific tasks and may return results to the calling program. Each function is assigned a specific name that is different from the names of other functions. The use of functions is referred to as structured programming or modular programming. The general syntax for a function is shown below, where type is the return type of the function, followed by the unique function name, followed by a parameter list, or arguments, which can be int, char, float, and so forth.

type function_name (parameter list)

{

Statements

}

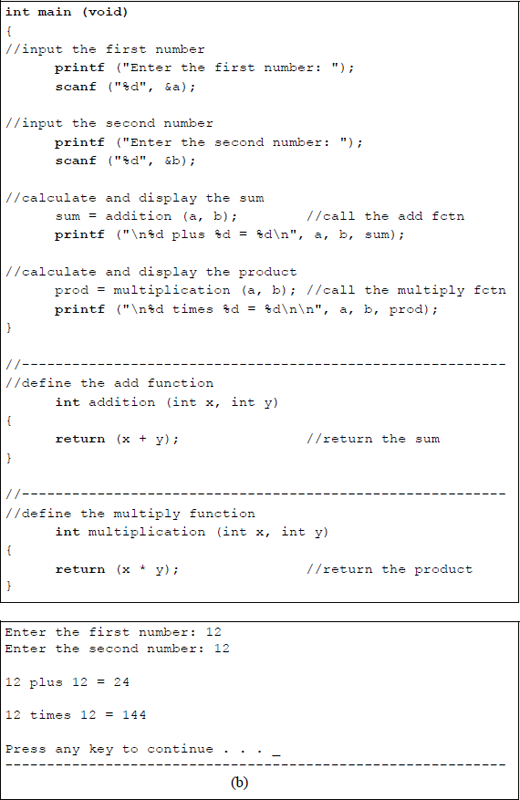

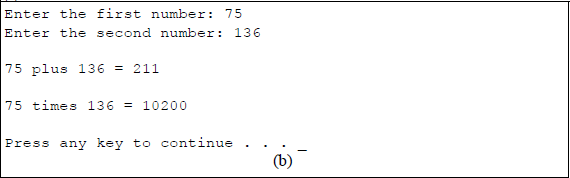

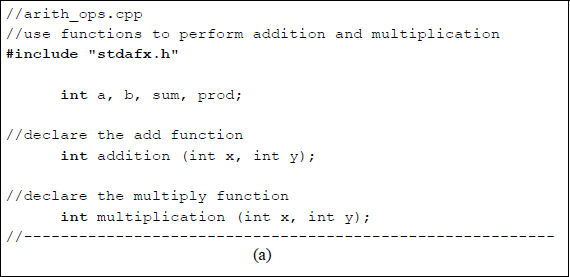

Program to illustrate one use of functions to perform addition and multiplication: (a) the C program and (b) the outputs.

The return type is specified as a global variable — also called an external variable — and indicates the type of value that the function will return to the calling program after execution of the function. In the program listing of Figure 4.56, a, b, sum, and prod are declared as type int prior to the main () function. Integers a and b are the arguments that are passed to the functions; the return values from the functions are assigned to sum and prod. The function statements are delimited by a beginning and an ending brace.

The addition function is called by the following statement, where a and b are the arguments that are passed to the function — the a and b values were entered by the user:

sum = addition (a, b);

The addition function is defined as shown below, where the type is int and the arguments, int x and int y, are declared as local variables to perform the addition operation. The return statement returns the sum of the integers that were entered by the user.

int addition (int x, int y)

{

return (x + y);

}

This chapter has presented only a minimal introduction to the C programming language, but is sufficient for the purpose of this book, which focuses on X86 assembly language programming. As stated previously, this book will link C programs with assembly language programs — this will occur in the remaining chapters of the book.

There are over 330 instructions in the X86 assembly language; therefore, in order to keep the number of pages to a reasonable number, only the most commonly used instructions will be presented. The remaining chapters in the book will discuss both the 16-bit general-purpose register (GPR) set and the 32-bit extended GPR register set to give variety to the presentation. Both sets of GPRs will incorporate linkage of C programs with assembly language.

4.8 Problems

4.1 Enter three floating-point numbers from the keyboard, add them, then print the sum.

4.2 Write a program to create three columns that show the binary numbers 1 through 256 as powers of 2.

4.3 Write a program to change the following Fahrenheit temperatures to centigrade temperatures: 32.0, 100.0, and 85.0. Then print the results.

4.4 Write a program that displays on three lines:

the number 10 as five digits right-aligned;

the number 99.95 as a floating-point number preceded by a $;

the first 10 characters of a 20-character string.

4.5 Write a program to calculate the volume of a parallelepiped. A parallelepiped is a six-faced polyhedron all of whose faces are parallelograms lying in pairs of parallel planes. Prompt for length, width, and height as integers, calculate the volume, then display the volume.

4.6 Write a program to determine the quotient and remainder of the following operations: 216 ÷ 5, 76 ÷ 6, and 744 ÷ 9.

4.7 Write a program to illustrate the difference between integer division and floating-point division regarding the remainder, using the following dividends and divisors: 742 ÷ 16 and 1756 ÷ 24. For the floating-point result, let the integer be two digits and the fraction be four digits.

4.8 Write a program to prompt for five integers, then display their average. Then display the five numbers in five-space increments.

4.9 Indicate which of the following expressions return a value of 1 (true) or 0 (false).

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

4.10 Indicate the value to which each of the following expressions evaluate.

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

4.11 Given x = 7, y = 25, and z = 24.46, write a program that generates either a 1 (true) or a 0 (false) for the following relational operators:

4.12 Write a program to convert from feet to meters or from meters to feet. Prompt for a value to be entered for feet or meters, then prompt for a choice: 1 means feet to meters; 2 means meters to feet. Check for both conversions.

4.13 Write a program to compare two integers that are entered from the keyboard. Indicate the relationship between the two integers — less than, equal, or greater than.

4.14 Write a program that prompts for two integers, then prompts whether the arithmetic operation is to be addition, subtraction, multiplication, or division. Display the resulting sum, difference, product, or quotient and remainder. Enter numbers for all four operations.

4.15 After execution of the following program, indicate the value of the expression for x:

(a) Without parentheses.

(b) With parentheses

// log_op_precedence.cpp

/* Determine to what the expression evaluateswithout and with parentheses.*/

#include <stdio.h>

int a = 5, b = 6, c = 5, d = 1;int x;

main (void){x = a < b || a < c && c < d;printf ("\nWithout parentheses, the expressionevaluates as %d", x);

x = (a < b || a < c) && c < d;printf ("\nWith parentheses, the expressionevaluates as %d\n\n", x);return 0;}4.16 Write a program to illustrate the relational, arithmetic, and logical operators. Prompt for three integers separated by spaces, then use the three operators on combinations of the inputs. Print the resulting outputs.

4.17 Given the values a = 3 and b = 4, write a program to evaluate the following two conditional statements:

(5 + 2 * (a > b)) ? a : b;(6>(a > b)) ? a : b;4.18 To what does the expression evaluate?

Rewrite the expression, adding parentheses, so that it evaluates to 16.

4.19 Given the program shown below, obtain the output for a, b, and c.

//pre_post_incr.cpp//example of preincrement and postincrement

#include "stdafx.h"

int main (void){int a, b;int c = 2;

a = ++c;b = c++;

printf ("%d %d %d\n\n", a, b, ++c);

return 0;}4.20 Given the program shown below, obtain the output for a and x.

//pre_post_incr2.cpp//evaluate preincrement and postincrement expressions

#include "stdafx.h"

int main (void){

int a;int x = 10;