Appendix

Frequently Asked University Questions With Solutions

PART A - Brief Questions

1. What do you mean by cryptanalysis?

Ans: Cryptanalysis: It is a process of attempting to discover the key or plaintext or both Cryptography: It is a science of writing Secret code using mathematical techniques. The many schemes used for enciphering constitute the area of study known as cryptography

2. What is difference between a block cipher and a stream cipher?

Ans: A block cipher processes the input one block of elements at a time, producing an output block for each input block. A stream cipher processes the input elements continuously, producing output one element at a time, as it goes along.

3. What is key distribution center?

Ans: A key distribution center is responsible for distributing keys to pairs of users (hosts, processes, applications) as needed. Each user must share a unique key with the key distribution center for purposes of key distribution. The use of a key distribution center is based on the use of a hierarchy of keys. At a minimum, two levels of keys are used. Communication between end systems is encrypted using a temporary key, often referred to as a session key .

4. Mention the application of public key cryptography.

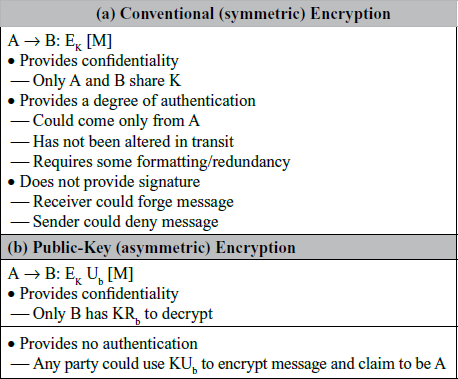

Ans: Public-key systems are characterized by the use of a cryptographic algorithm with two keys, one held private and one available publicly. Depending on the application, the sender uses either the sender’s private key or the receiver’s public key, or both, to perform some type of cryptographic function. In broad terms, we can classify the use of public-key cryptosystems into three categories:

Encryption/decryption: The sender encrypts a message with the recipient’s public key.

Digital signature: The sender “signs” a message with its private key. Signing is achieved by a cryptographic algorithm applied to the message or to a small block of data that is a function of the message.

Key exchange: Two sides cooperate to exchange a session key. Several different approaches are possible, involving the private key(s) of one or both parties.

5. Specify the requirements for message authentication.

Ans: Authentication Requirements

In the context of communications across a network, the following attacks can be identified:

- Disclosure: Release of message contents to any person or process not possessing the appropriate cryptographic key.

- Traffic analysis: Discovery of the pattern of traffic between parties. In a connection-oriented application, the frequency and duration of connections could be determined. In either a connection-oriented or connectionless environment, the number and length of messages between parties could be determined.

- Masquerade: Insertion of messages into the network from a fraudulent source. This includes the creation of messages by an opponent that are purported to come from an authorized entity. Also included are fraudulent acknowledgments of message receipt or non receipt by someone other than the message recipient.

- Content modification: Changes to the contents of a message, including insertion, deletion, transposition, and modification.

- Sequence modification: Any modification to a sequence of messages between parties, including insertion, deletion, and reordering.

- Timing modification: Delay or replay of messages. In a connection-oriented application, an entire session or sequence of messages could be a replay of some previous valid session, or individual messages in the sequence could be delayed or replayed. In a connectionless application, an individual message (e.g., datagram) could be delayed or replayed.

- Source repudiation: Denial of transmission of message by source.

- Destination repudiation: Denial of receipt of message by destination.

6. What are the two important key issues related to authenticated key exchange?

Ans: Two key issues are confidentiality and timeliness. To prevent masquerade and to prevent compromise of session keys, essential identification and session key information must be communicated in encrypted form. This requires the prior existence of secret or public keys that can be used for this purpose. The second issue, timeliness, is important because of the threat of message replays. Such replays, at worst, could allow an opponent to compromise a session key or successfully impersonate another party. At minimum, a successful replay can disrupt operations by presenting parties with messages that appear genuine but are not.

7. What entities constitute a full-service Kerberos environment?

Ans: If a set of users is provided with dedicated personal computers that have no network connections, then a user’s resources and files can be protected by physically securing each personal computer. When these users instead are served by a centralized time-sharing system, the time-sharing operating system must provide the security. The operating system can enforce access control policies based on user identity and use the logon procedure to identify users.Today, neither of these scenarios is typical. More common is a distributed architecture consisting of dedicated user workstations (clients) and distributed or centralized servers. In this environment, three approaches to security can be envisioned:

- Rely on each individual client workstation to assure the identity of its user or users and rely on each server to enforce a securitypolicy based on user identification (ID).

- Require that client systems authenticate themselves to servers, but trust the client system concerning the identity of its user.

- Require the user to prove his or her identity for each service invoked. Also require that servers prove their identitytoclients.

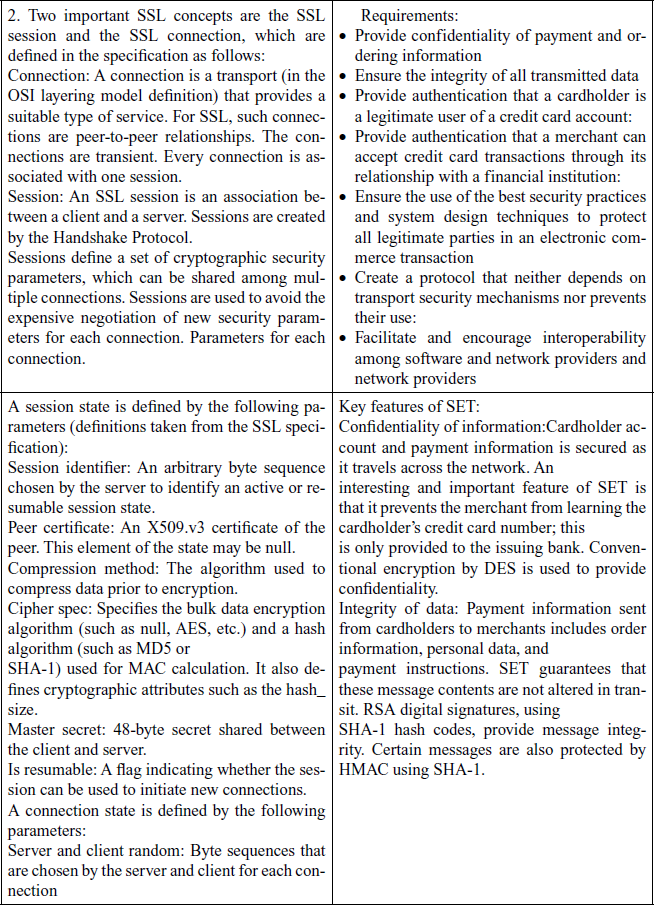

8. Why does ESP include a padding field?

Ans: The Padding field serves several purposes:

- If an encryption algorithm requires the plaintext to be a multiple of some number of bytes (e.g., the multiple of a single block for a block cipher), the Padding field is used to expand the plaintext (consisting of the Payload Data, Padding, Pad Length, and Next Header fields) to the required length.

- The ESP format requires that the Pad Length and Next Header fields be right aligned within a 32-bit word. Equivalently, the cipher text must be an integer multiple of 32 bits. The Padding field is used to assure this alignment.

- Additional padding may be added to provide partial traffic flow confidentiality by concealing the actual length of the payload.

9. What are the two types of audit records?

Ans:

- Native audit records: Virtually all multiuser operating systems include accounting software that collects information on user activity. The advantage of using this information is that no additional collection software is needed. The disadvantage is that the native audit records may not contain the needed information or may not contain it in a convenient form.

- Detection-specific audit records: A collection facility can be implemented that generates audit records containing only that information required by the intrusion detection system. One advantage of such an approach is that it could be made vendor independent and ported to a variety of systems. The disadvantage is the extra overhead involved in having, in effect, two accounting packages running on a machine.

10. What is an access control matrix? What are its elements?

Ans: The basic elements of the model are as follows:

- Subject: An entity capable of accessing objects. Generally, the concept of subject equates with that of process. Any user or application actually gains access to an object by means of a process that represents that user or application.

- Object: Anything to which access is controlled. Examples include files, portions of files, programs, and segments of memory.

- Access right: The way in which an object is accessed by a subject. Examples are read, write, and execute.

11. Give the types of attack.

Ans:

Passive Attacks

Passive attacks are in the nature of eavesdropping on, or monitoring of, transmissions. The goal of the opponent is to obtain information that is being transmitted. Two types of passive attacks are release of message contents and traffic analysis.

Active Attacks

Active attacks involve some modification of the data stream or the creation of a false stream and can be subdivided into four categories: masquerade, replay, modification of messages, and denial of service.

12. List out the problems of one time pad?

Ans: The one-time pad offers complete security but, in practice, has two fundamental difficulties:

- There is the practical problem of making large quantities of random keys. Any heavily used system might require millions of random characters on a regular basis. Supplying truly random characters in this volume is a significant task.

- Even more daunting is the problem of key distribution and protection. For every message to be sent, a key of equal length is needed by both sender and receiver. Thus, a mammoth key distribution problem exists.

- Because of these difficulties, the one-time pad is of limited utility, and is useful primarily for low-bandwidth channels requiring very high security.

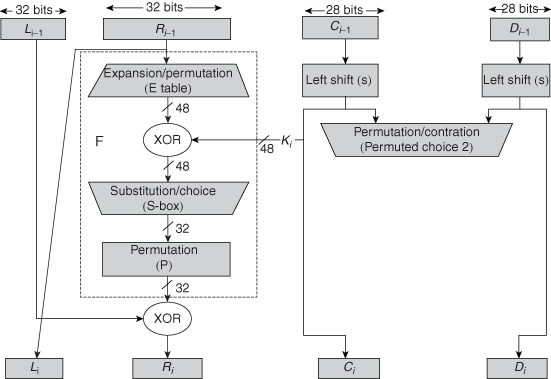

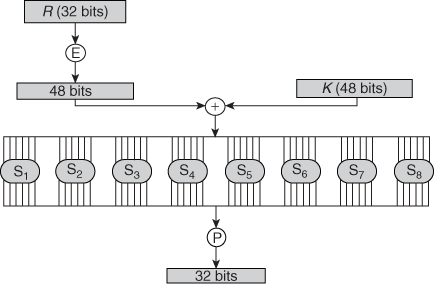

13. Write down the purpose of the S-Boxes in DES?

Ans: The role of the S-boxes in the function F is illustrated as the substitution consists of a set of eight S-boxes, each of which accepts 6 bits as input and produces 4 bits as output. These transformations are interpreted as follows: The first and last bits of the input to box Si form a 2-bit binary number to select one of four substitutions defined by the four rows in the table for Si. The middle four bits select one of the sixteen columns. The decimal value in the cell selected by the row and column is then converted to its 4-bit representation to produce the output. For example, in S1 for input 011001, the row is 01 (row 1) and the column is 1100 (column 12). The value in row 1, column 12 is 9, so the output is 1001.

14. Define : Diffusion.

Ans: Statistical structure of the plaintext is dissipated into long-range statistics of cipher text.

Confusion: Relationship between cipher text and key is made complex.

15. Define: Replay attack.

Ans: An attack in which a service already authorized and completed is forged by another “duplicate request” in an attempt to repeat authorized commands.

- Simple replay: The opponent simply copies a message and replays it later.

- Repetition that can be logged: An opponent can replay a timestamped message within the valid time window.

- Repetition that cannot be detected: This situation could arise because the original message could have been suppressed and thus did not arrive at its destination; only the replay message arrives.

- Backward replay without modification: This is a replay back to the message sender. This attack is possible if symmetric

encryption is used and the sender cannot easily recognize the difference between messages sent and messages received on the basis of content.

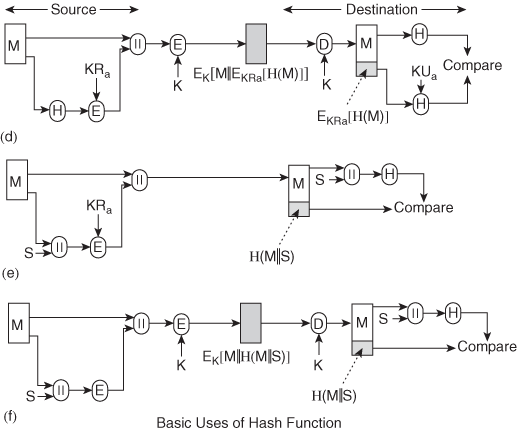

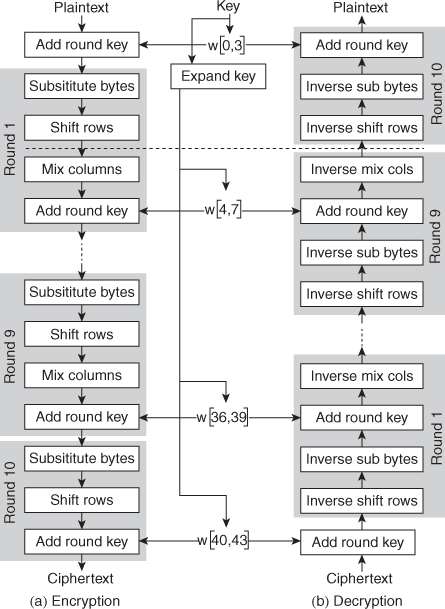

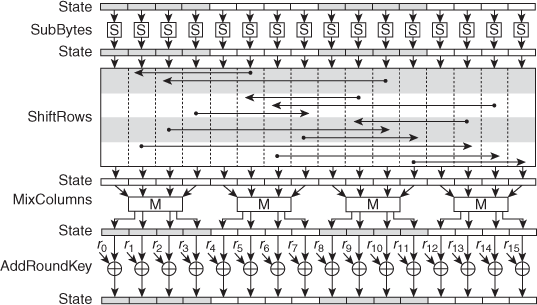

16. List out the parameters of AES.

Ans:

17. Define : Primality test.

Ans:

It is necessary to select one or more very large prime numbers at random. Thus we are faced with the task of determining whether a given large number is prime.

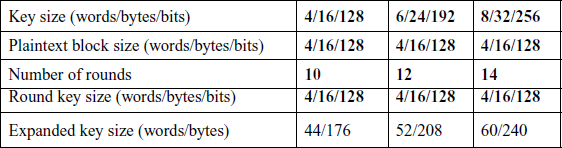

18. State the difference between conventional encryption and public-key encryption.

Ans:

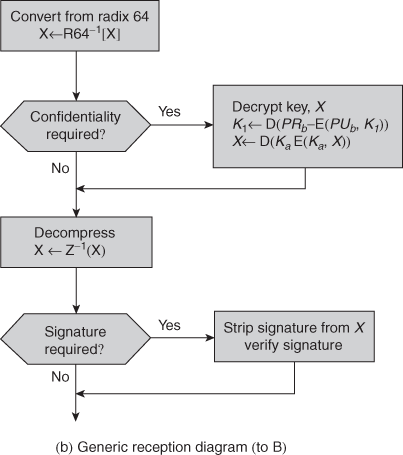

19. Define : Malicious software.

Ans:

Malicious software is software that is intentionally included or inserted in a system for a harmful purpose.

20. Name any two security standards.

Ans: RC4 is used in the SSL/TLS (Secure Sockets Layer/Transport Layer Security) standards that have been defined for communication between Web browsers and servers. SET used by visa Card.

21. Differentiate passive attack from active attack with exzmple.

Ans: Passive attacks are in the nature of eavesdropping on, or monitoring of, transmissions. The goal of the opponent is to obtain information that is being transmitted. Two types of passive attacks are release of message contents and traffic analysis.

Eg: A telephone conversation, an electronic mail message, and a transferred file may contain sensitive or confidential information. We would like to prevent an opponent from learning the contents of these transmissions.

Active attacks involve some modification of the data stream or the creation of a false stream and can be subdivided into four categories: masquerade, replay, modification of messages, and denial of service.

A masquerade takes place when one entity pretends to be a different entity .Masquerade attack usually includes one of the other forms of active attack. For example, authentication sequences can be captured and replayed after a valid authentication sequence has taken place, thus enabling an authorized entity with few privileges to obtain extra privileges by impersonating an entity that has those privileges.

22. What is the use of Fermat’s theorem?

Ans: Fermat’s theorem states the following: If p is prime and a is a positive integer not divisible by p, then

aP-1=1(mod P)

Proof: Consider the set of positive integers less than p:{1,2,..., p 1} and multiply each element bya, modulo p, to get the set X = {a mod p,

2a mod p, . . . (p 1)a mod p}. None of the elements of X is equal to zero because p does not divide a.

23. What are the different modes of operation in DES?

Ans:

- Electronic code Book

- Cipher Block chaining

- Cipher feedback mode

- Output Feedback mode

- Counter

24. Name any two methods for testing prime numbers.

Ans:

- Miller-Rabin Algorithm

- A Deterministic Primality Algorithm

- Chinese Remainder algorithm

25. What is discrete logarithm?

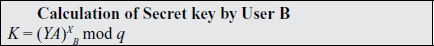

Ans: Discrete logarithms are fundamental to a number of public-key algorithms, including Diffie-Hellman key exchange and the digital signature algorithm (DSA).

Calculation of Discrete Logarithms

Consider the equation

y = gx mod p

Given g, x, and p, it is a straightforward matter to calculate y. At the worst, we must perform x repeated multiplications, and algorithms exist for achieving greater efficiency

26. What do you mean by one-way property in hash function?

Ans: A variation on the message authentication code is the one-way hash function. As with the message authentication code, a hash function accepts a variable-size message M as input and produces a fixed-size output, referred to as a hash code H(M). Unlike a MAC, a hash code does not use a key but is a function only of the input message. The hash code is also referred to as a message digest or hash value. The hash code is a function of all the bits of the message and provides an error-detection capability: A change to any bit or bits in the message results in a change to the hash code.

27. List out the requirements of Kerberos.

Ans: Kerberos listed the following requirements:

- Secure: A network eavesdropper should not be able to obtain the necessary information to impersonate a user. Generally, Kerberos should be strong enough that a potential opponent does not find it to be the weak link.

- Reliable: For all services that rely on Kerberos for access control, lack of availability of the Kerberos service means lack of availability of the supported services. Hence, Kerberos should be highly reliable and should employ a distributed server architecture, with one system able to back up another.

- Transparent: Ideally, the user should not be aware that authentication is taking place, beyond the requirement to enter a password.

- Scalable: The system should be capable of supporting large numbers of clients and servers. This suggests a modular, distributed architecture.

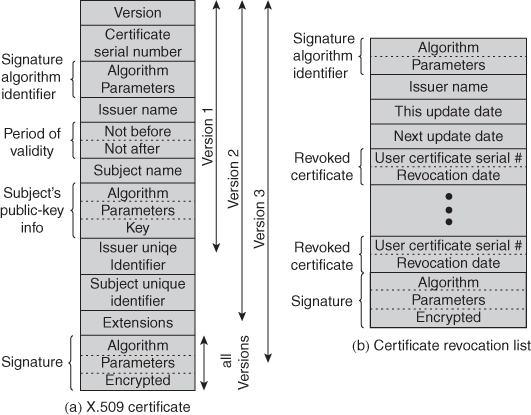

28. Mention four SSL protocols.

Ans:

- SSL Handshake protocol

- SSL change cipher spec protocol

- SSL Alert Protocol

- SSL Record Protocol

29. Define Intruders. Name three different classes of Intruders.

Ans: Threats to security is the intruder (the other is viruses), generally referred to as a hacker or cracker.

- Classes of intruders:

- Masquerader: An individual who is not authorized to use the computer and who penetrates a system’s access controls to exploit a legitimate user’s account

- Misfeasor: A legitimate user who accesses data, programs, or resources for which such access is not authorized, or who is authorized for such access but misuses his or her privileges

Clandestine user: An individual who seizes supervisory control of the system and uses this control to evade auditing and access controls or to suppress audit collection

30. What do you mean by Trojan Horses?

Ans: Trojan horse is a useful, or apparently useful, program or command procedure containing hidden code that, when invoked, performs some unwanted or harmful function.

Example, to gain access to the files of another user on a shared system, a user could create a Trojan horse program that, when executed, changed the invoking user’s file permissions so that the files are readable by any user.

31. Define threads and attacks.

Ans:

Threat: A potential for violation of security, which exists when there is a circumstance, capability, action,or event that could breach security and cause harm.That is, a threat is a possible danger that might exploit a vulnerability.

Attack: An assault on system security that derives from an intelligent threat; that is, an intelligent act that is a deliberate attempt to evade security services and violate the security policy of a system.

32. What are the resources for secure use of conventional encrytion?

Ans: Plaintext,Encryption Algorithm,Secret Key,Ciphertext and Decryption algorithm are the resources for secure use of conventional encrytion.

33. Using Fermat theorem find 3201 mod 11.

Ans:

a=3 ; p=201

ap=a(mod p)

310= 1 (mod 11)

3201=(3)(310)(320)=(3)(310)(320)=(3)(1)20= 3(mod11)n.

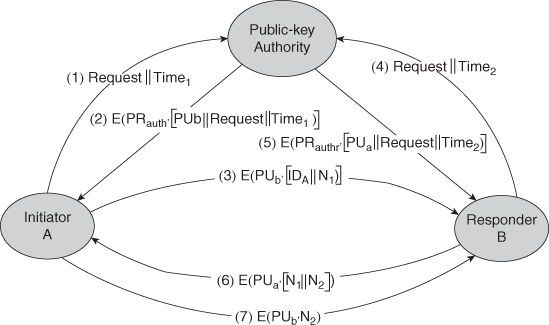

34. List the techniques for distribution of public keys.

Ans:

- Public Announcement

- Publicly available directory

- Public Key Authority

- Public Key Certificates

35. What is suppress reply attack.

Ans: The problem occurs when a sender’s clock is ahead of the intended recipient’s clock. In this case, an opponent can intercept a message from the sender and replay it later when the timestamp in the message becomes current at the recipient’s site. This replay could cause unexpected results. This attack is known as suppress replay attack.

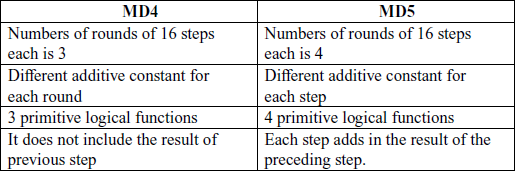

36. What is the difference between MD4 and MD5 ?

Ans:

37. What is a realm?

Ans: A kerberos realm is a set of managed nodes that store the same kerberos database. The kerberos database resides on the kerberos master computer.

PART B - Detailed Questions

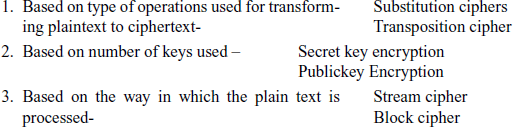

1. Explain about substitution and transposition techniques with two examples for each.

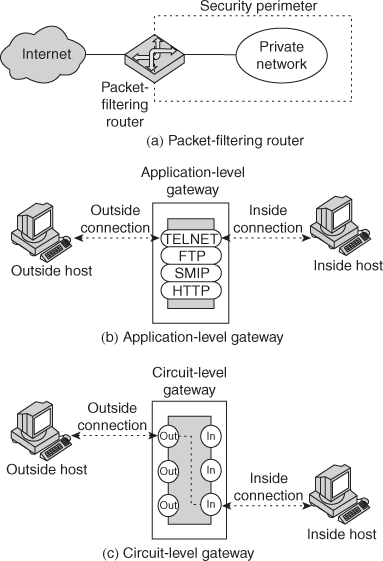

Ans: Classification of Cryptographic systems:

Substitution Techniques

The two basic building blocks of all encryption techniques are substitution and transposition. A substitution technique is one in which the letters of plaintext are replaced by other letters or by numbers or symbols. If the plaintext is viewed as a sequence of bits, then substitution involves replacing plaintext bit patterns with cipher text bit patterns.

1. Ceaser cipher

2. monoalphabetic cipher

3. Homophonic substitution cipher

4. Polygram Substitution cipher

5. Polyalphabetic cipher

Caesar Cipher

The earliest known use of a substitution cipher, and the simplest, was by Julius Caesar. The Caesar cipher involves replacing each letter of the alphabet with the letter standing three places further down the alphabet.

For example,

plain: meet me after the toga party

cipher: PHHW PH DIWHU WKH WRJD SDUWB

The alphabet is wrapped around, so that the letter following Z is A. We can define the transformation by listing all possibilities, as follows:

plain: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

cipher: D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C

we can also assign a numerical equivalent to each letter:

Monoalphabetic Ciphers

With only 25 possible keys, the Caesar cipher is far from secure. A dramatic increase in the key space can be achieved by allowing an arbitrary substitution. Recall the assignment for the Caesar cipher:

plain: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

cipher: D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C

If, instead, the “cipher” line can be any permutation of the 26 alphabetic characters, then there are 26! or greater than 4 x 10 26 possible keys. This is 10 orders of magnitude greater than the key space for DES and would seem to eliminate brute-force techniques for cryptanalysis. Such an approach is referred to as a monoalphabetic substitution cipher, because a single cipher alphabet (mapping from plain alphabet to cipher alphabet) is used per message.

Playfair Cipher

The best-known multiple-letter encryption cipher is the Playfair, which treats digrams in the plaintext as single units and translates these

M O N A R

C H Y B D

E F G I/J K

L P Q S T

U V W X Z

In this case, the keyword is monarchy. The matrix is constructed by filling in the letters of the keyword (minus duplicates) from left to rightand from top to bottom, and then filling in the remainder of the matrix with the remaining letters in alphabetic order. The letters I and Jount as one letter. Plaintext is encrypted two letters at a time, according to the following rules:

1. Repeating plaintext letters that are in the same pair are separated with a filler letter, such as x, so that balloon would be treated as ba lx lo on.

2. Two plaintext letters that fall in the same row of the matrix are each replaced by the letter to the right, with the first element of the row circularly following the last. For example, ar is encrypted as RM.

3. Two plaintext letters that fall in the same column are each replaced by the letter beneath, with the top element of the column circularly following the last. For example, mu is encrypted as CM.

4. Otherwise, each plaintext letter in a pair is replaced by the letter that lies in its own row and the column occupied by the other plaintext letter. Thus, hs becomes BP and ea becomes IM (or JM, as the encipherer wishes).

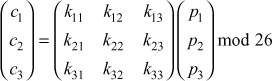

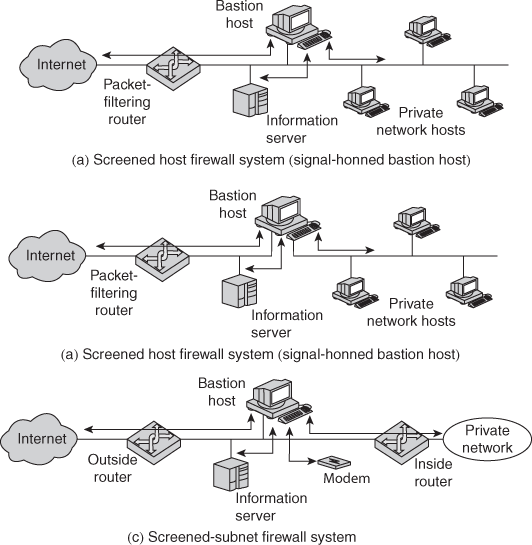

Hill Cipher

This cipher is somewhat more difficult to understand than the others in this chapter, but it illustrates an important point about cryptanalysis that will be useful later on. This subsection can be skipped on a first reading.

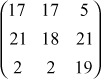

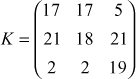

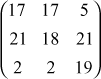

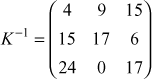

Another interesting multiletter cipher is the Hill cipher, developed by the mathematician Lester Hill in 1929. The encryption algorithm takes m successive plaintext letters and substitutes for them m ciphertext letters. The substitution is determined by m linear equations in which each character is assigned a numerical value (a = 0, b = 1 ... z = 25). For m = 3, the system can be described as follows:

c3 = (k31P1 + k32P2 + k33P3) mod 26

This can be expressed in term of column vectors and matrices:

C = KP mod 26

where C and P are column vectors of length 3, representing the plaintext and ciphertext, and K is a 3 x 3 matrix, representing the encryption key. Operations are performed mod 26.

Polyalphabetic Ciphers

Another way to improve on the simple monoalphabetic technique is to use different monoalphabetic substitutions as one proceeds through the plaintext message. The general name for this approach is polyalphabetic substitution cipher. All these techniques have the following features in common:

1. A set of related monoalphabetic substitution rules is used.

2. A key determines which particular rule is chosen for a given transformation.

The best known, and one of the simplest, such algorithm is referred to as the Vigenère cipher. In this scheme, the set of related monoalphabetic substitution rules consists of the 26 Caesar ciphers, with shifts of 0 through 25. Each cipher is denoted by a key letter, which is the ciphertext letter that substitutes for the plaintext letter a.

One-Time Pad

An Army Signal Corp officer, Joseph Mauborgne, proposed an improvement to the Vernam cipher that yields the ultimate in security. Mauborgne suggested using a random key that is as long as the message, so that the key need not be repeated. In addition, the key is to be used to encrypt and decrypt a single message, and then is discarded. Each new message requires a new key of the same length as the new message. Such a scheme, known as a one-time pad, is unbreakable. It produces random output that bears no statistical relationship to the plaintext. Because the ciphertext contains no information whatsoever about the plaintext, there is simply no way to break the code.

Transposition Techniques

- Rail Fence Techniques

- Columnar transposition Techniques

- Book cipher

- Vernam Cipher/one time pad

All the techniques examined so far involve the substitution of a ciphertext symbol for a plaintext symbol. A very different kind of mapping is achieved by performing some sort of permutation on the plaintext letters. This technique is referred to as a transposition cipher. The simplest such cipher is the rail fence technique, in which the plaintext is written down as a sequence of diagonals and then read off as a sequence of rows. For example, to encipher the message “meet me after the toga party” with a rail fence of depth 2, we write the following:

The encrypted message is

MEMATRHTGPRYETEFETEOAAT

This sort of thing would be trivial to cryptanalyze. A more complex scheme is to write the message in a rectangle, row by row, and read the message off, column by column, but permute the order of the columns. The order of the columns then becomes the key to the algorithm. For example,

Key: 4 3 1 2 5 6 7

Plaintext: a t t a c k p

o s t p o n e

d u n t i l t

w o a m x y z

Ciphertext: TTNAAPTMTSUOAODWCOIXKNLYPETZ

A pure transposition cipher is easily recognized because it has the same letter frequencies as the original plaintext. For the type of columnar transposition just shown, cryptanalysis is fairly straightforward and involves laying out the ciphertext in a matrix and playing around with column positions. Digram and trigram frequency tables can be useful. The transposition cipher can be made significantly more secure by performing more than one stage of transposition. The result is a more complex permutation that is not easily reconstructed. Thus, if the foregoing message is reencrypted using the same algorithm,

Key: 4 3 1 2 5 6 7

Input: t t n a a p t

m t s u o a o

d w c o i x k

n l y p e t z

Output: NSCYAUOPTTWLTMDNAOIEPAXTTOKZ

To visualize the result of this double transposition, designate the letters in the original plaintext message by the numbers designating their position. Thus, with 28 letters in the message, the original sequence of letters is

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14

15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

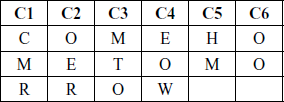

Rail Fence techniques:

1. Write down the plain text message as a sequence of diagonals.

2. Read the plaintext written in step 1 as a sequence of rows.

plain text: Come home tomorrow

Cipher text: cmh mt mr ooeoeoorw.

Columnar transposition technique:

1 Writ the plain text message row by row in a rectangle of a predefined size.

2. Read the message column by column .it need not be in the order of the column 1,2,3…

3. The message thus obtained is the cipher text message.

plain text: Come home tomorrow

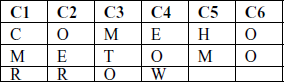

Let us consider a rectangle with six columns.

the order of columns chosen in random order say 4,6,1,2,5,3 .Then read the text in order of these columns.

Cipher text: eowoocmroerhmmto

Vernam cipher:

1. Treat each plain text alphabet as a number in an increasing sequence.

2. do the same for each character of the input cipher text.

3. Add each number corresponding to the plaintext alphabet to the corresponding input ciphertext alphabet number.

4. If the sum has produced is greater than 26,subtract 26 from it.

5. translate each number of the sum back to the corresponding alphabet. This gives the cipher test.

2. What is the need for triple DES? Write the disadvantages of double DES and explain triple DES.

Ans: The use of double DES results in a mapping that is not equivalent to a single DES encryption. But there is a way to attack this scheme, one that does not depend on any particular property of DES but that will work against any block encryption cipher.

The algorithm, known as a meet-in-the-middle attack, C = E(K2, E(K1, P))

then (X = E(K1, P) = D(K2, P)

Given a known pair, (P, C), the attack proceeds as follows. First, encrypt P for all 256 possible values of K1 Store these results in a table and then sort the table by the values of X. Next, decrypt C using all 256 possible values of K2. As each decryption is produced, check the result against the table for a match. If a match occurs, then test the two resulting keys against a new known plaintext-ciphertext pair. If the two keys produce the correct ciphertext, accept them as the correct keys.

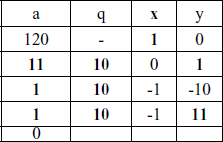

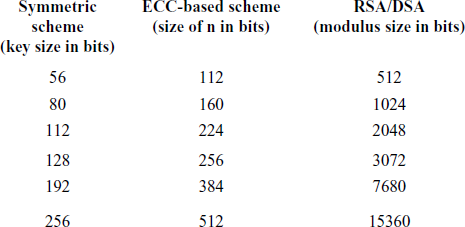

3. Explain how the elliptic curves are useful for cryptography?

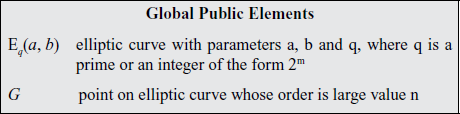

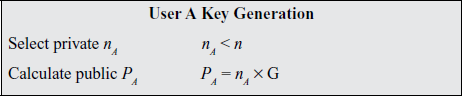

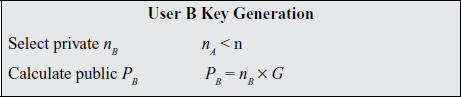

Ans: Several approaches to encryption/decryption using elliptic curves . The first task in this system is to encode the plaintext message m to be sent as an x-y point Pm. It is the point Pm that will be encrypted as a ciphertext and subsequently decrypted. Note that we cannot simply encode the message as the x or y coordinate of a point, because not all such coordinates are in Eq(a, b);. Again, there are several approaches to this encoding, which we will not address here, but suffice it to say that there are relatively straightforward techniques that can be used. As with the key exchange system, an encryption/decryption system requires a point G and an elliptic group Eq(a, b) as parameters. Each user A selects a private key nA and generates a public key PA = nA x G.

To encrypt and send a message Pm to B, A chooses a random positive integer k and produces the ciphertext Cm consisting of the pair of points:

Cm = {kG, Pm + kPB}

Note that A has used B’s public key PB. To decrypt the ciphertext, B multiplies the first point in the pair by B’s secret key and subtracts the result from the second point:

Pm + kPB nB(kG) = Pm + k(nBG) nB(kG) = Pm

A has masked the message Pm by adding kPB to it. Nobody but A knows the value of k, so even though PB is a public key, nobody can remove the mask kPB. However, A also includes a “clue,” which is enough to remove the mask if one knows the private key n B. For an attacker to recover the message, the attacker would have to compute k given G and kG, which is assumed hard. As an example of the encryption process take p = 751; Ep(1, 188), which is equivalent to the curve y2= x3x + 188;and G = (0, 376). Suppose that A wishes to send a message to B that is encoded in the elliptic poinPtm = (562, 201) and that A selects the random number k = 386. B’s public key is PB = (201, 5). We have 386(0, 376) = (676, 558), and (562, 201) + 386(201, 5) = (385, 328). Thus A sends the cipher text {(676, 558), (385, 328)}.

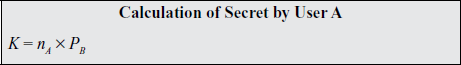

A key exchange between users A and B can be accomplished as follows .A selects an integer nA less than n. This is A’s private key.

1. A then generates a public keyP A = nA x G; the public key is a point in Eq(a, b).

2. B similarly selects a private key nB and computes a public key PB.

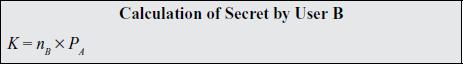

3. A generates the secret key K = nA x PB. B generates the secret keyK = nB x PA.

ECC Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange

The two calculations in step 3 produce the same result because

nA x PB = nA x (nB x G) = nB x (nA x G) = nB x PA

To break this scheme, an attacker would need to be able to compute k given G and kG, which is assumed hard.

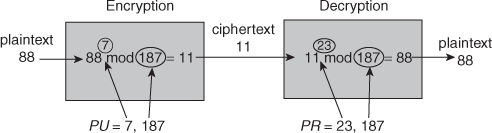

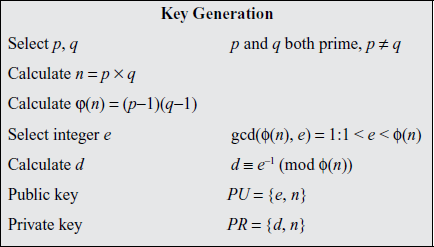

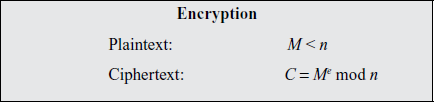

4. In a public key system using RSA, you intercept the cipher text C = 10 sent to a user whose public key is e=5, n=35. What is the plain text? Explain the above problem with an algorithm description.

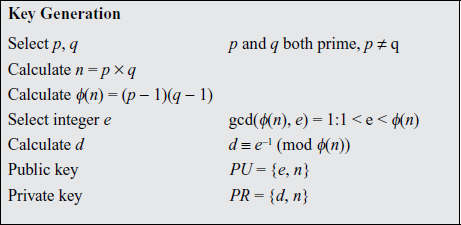

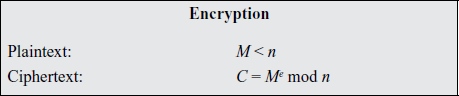

Ans: Description of the Algorithm

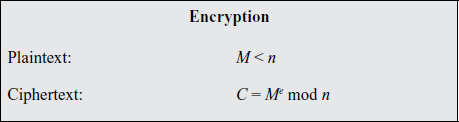

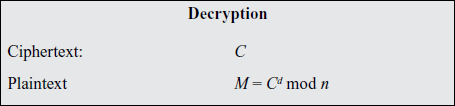

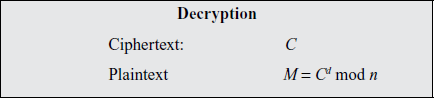

The scheme developed by Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman makes use of an expression with exponentials. Plaintext is encrypted in blocks, with each block having a binary value less than some number n. That is, the block size must be less than or equal to log2(n); in practice, the block size is i bits, where 2 I ≤ n 2 i+1. Encryption and decryption are of the following form, for some plaintext blockM and ciphertext block C:

C = Memod n

M = Cdmod n = (Me)dmod n = Medmod n

Both sender and receiver must know the value of n. The sender knows the value of e, and only the receiver knows the value of d. Thus, this is a public-key encryption algorithm with a public key of PU = {e, n} and a private key of PU = {d, n}.

For this algorithm to be satisfactory for public-key encryption, the following requirements must be met:

1. It is possible to find values of e, d, n such that M ed mod n = M for all M < n.

2. It is relatively easy to calculate mod Memod n and Cdmod n . for all values of M < n.

3. It is infeasible to determine d given e and n.

To find a relationship of the form Medmod n = M

4. if e and d are multiplicative inverses modulo f(n), where f(n) is the Euler totient function. It is shown in

that for p, q prime, f(pq) = (p- 1)(q-1) The relationship between e and d can be expressed as

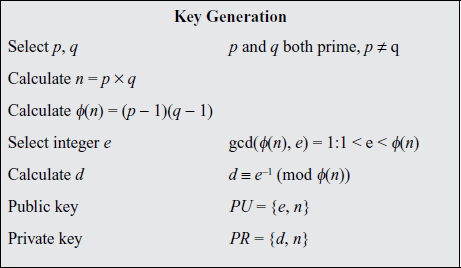

1. Select two prime numbers, p = 17 and q = 11.

2. Calculate n = pq = 17 x 11 = 187.

3. Calculate f(n) = (p- 1)(q-1) = 16 x 10 = 160.

4. Select e such that e is relatively prime to f(n) = 160 and less than f(n) we choose e = 7.

Determine d such that de 1 (mod 160) and d < 160. The correct value is d = 23, because 23 x 7 = 161 = 1x 160 + 1; d can be calculated using the extended Euclid’s algorithm.

C=10

e=5

n=35

if n=35 ,p=7,q=5 O(n)=(7-1)(5-1)=24

ed= 1 mod O(n)=5*21=105 mod 24

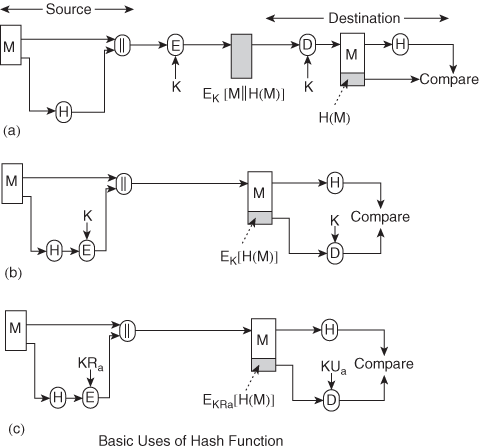

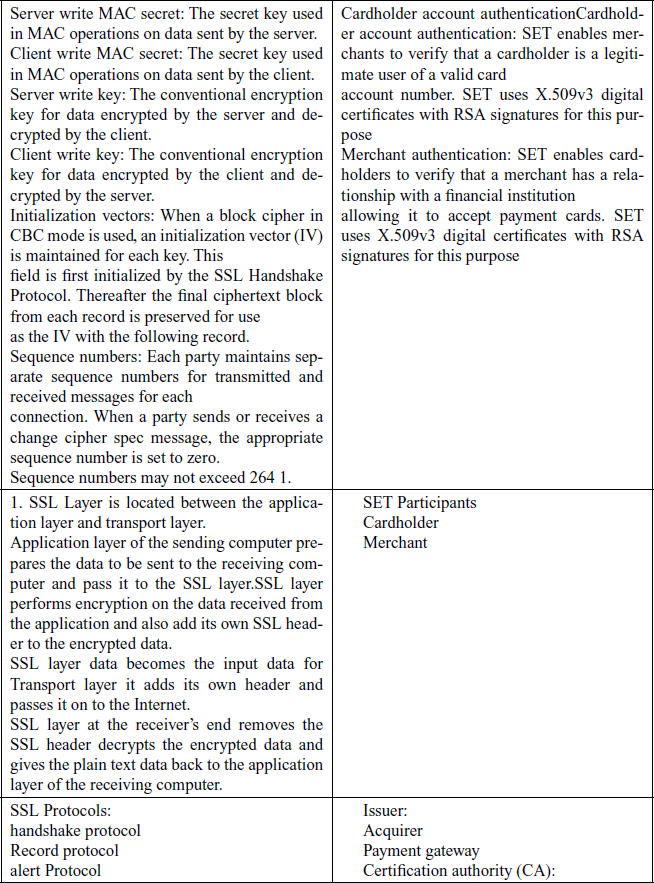

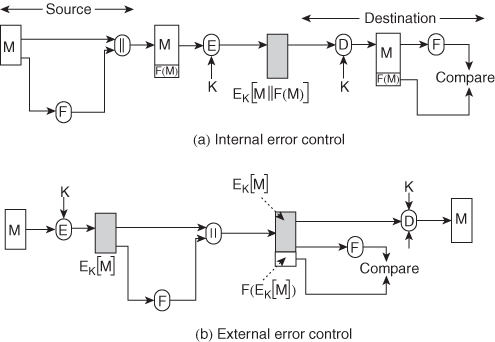

5. Write about the basic uses of MAC and list out the applications.

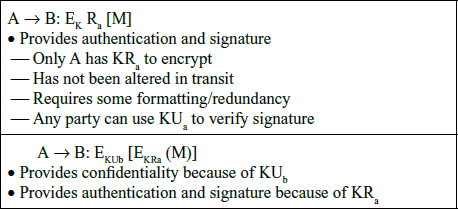

Ans: An alternative authentication technique involves the use of a secret key to generate a small fixed-size block of data, known as a cryptographic checksum or MAC that is appended to the message. This technique assumes that two communicating parties, say A and B, share a common secret key K. When A has a message to send to B, it calculates the MAC as a function of the message and the key:

MAC= C(K, M), where

M = input message

C = MAC function

K = shared secret key

MAC = message authentication code

The message plus MAC are transmitted to the intended recipient. The recipient performs the same calculation on the received message, using the same secret key, to generate a new MAC. The received MAC is compared to the calculated MAC .If we assume that only the receiver and the sender know the identity of the secret key, and if the received MAC matches the calculated MAC, then

1. The receiver is assured that the message has not been altered. If an attacker alters the message but does not alter the MAC, then the receiver’s calculation of the MAC will differ from the received MAC. Because the attacker is assumed not to know the secret key, the attacker cannot alter the MAC to correspond to the alterations in the message.

2. The receiver is assured that the message is from the alleged sender. Because no one else knows the secret key, no one else could prepare a message with a proper MAC.

3. If the message includes a sequence number (such as is used with HDLC, X.25, and TCP), then the receiver can be assured of the proper sequence because an attacker cannot successfully alter the sequence number.

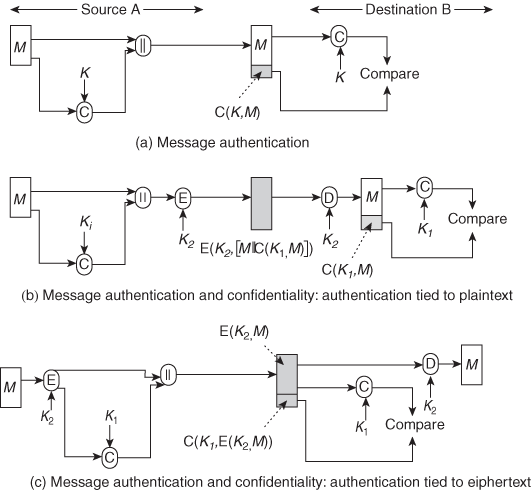

It suggests three situations in which a message authentication code is used:

- There are a number of applications in which the same message is broadcast to a number of destinations. It is cheaper and more reliable to have only one destination responsible for monitoring authenticity. Thus, the message must be broadcast in plaintext with an associated message authentication code. The responsible system has the secret key and performs authentication. If a violation occurs, the other destination systems are alerted by a general alarm.

- An exchange in which one side has a heavy load and cannot afford the time to decrypt all incoming messages. Authentication is carried out on a selective basis, messages being chosen at random for checking.

- Authentication of a computer program in plaintext is an attractive service. The computer program can be executed without having to decrypt it every time, which would be wasteful of processor resources. However, if a message authentication code were attached to the program, it could be checked whenever assurance was required of the integrity of the program.

Three other rationales may be added, as follows:

- For some applications, it may not be of concern to keep messages secret, but it is important to authenticate messages. An example is the Simple Network Management Protocol Version 3 (SNMPv3), which separates the functions of confidentiality and authentication. For this application, it is usually important for a managed system to authenticate incoming SNMP messages, particularly if the message contains a command to change parameters at the managed system. On the other hand, it may not be necessary to conceal the SNMP traffic.

- Separation of authentication and confidentiality functions affords architectural flexibility.

- A user may wish to prolong the period of protection beyond the time of reception and yet allow processing of message contents. With message encryption, the protection is lost when the message is decrypted, so the message is protected against fraudulent modifications only in transit but not within the target system.

- Finally, note that the MAC does not provide a digital signature because both sender and receiver share the same key.

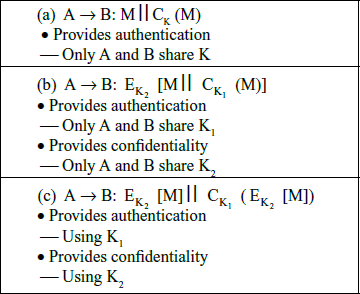

- Provides authentication

Only A and B share K

(a) Message authentication

A B:E(K2, [M||C(K, M)])

B:E(K2, [M||C(K, M)])

Provides authentication

Only A and B share K1

Provides confidentiality

Only A and B share K2

(b) Message authentication and confidentiality: authentication tied to plaintext

A B:E(K2, M)||C(K1, E(K2, M))

B:E(K2, M)||C(K1, E(K2, M))

Provides authentication

Using K1

Provides confidentiality Using K2

(c) Message authentication and confidentiality: authentication tied to ciphertext

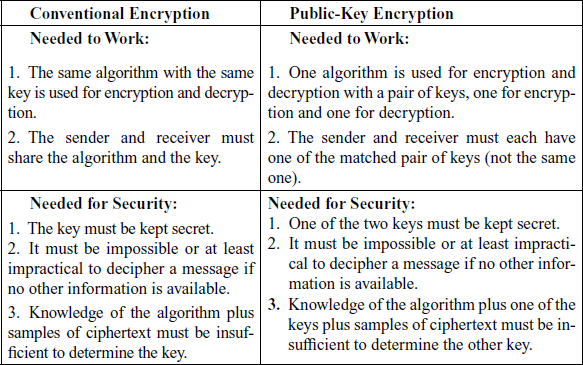

6. With a neat sketch, explain signing and verifying functions of DSA.

Ans: Message authentication protects two parties who exchange messages from any third party. However, it does not protect the two parties against each other.

Requirements for a digital signature:

- The signature must be a bit pattern that depends on the message being signed.

- The signature must use some information unique to the sender, to prevent both forgery and denial.

- It must be relatively easy to produce the digital signature.

- It must be relatively easy to recognize and verify the digital signature.

- It must be computationally infeasible to forge a digital signature, either by constructing a new message for an existing digital signature or by constructing a fraudulent digital signature for a given message.

- It must be practical to retain a copy of the digital signature in storage.

A variety of approaches has been proposed for the digital signature function. These approaches fall into two categories: direct and arbitrated.

Direct Digital Signature

- The direct digital signature involves only the communicating parties (source, destination).

- It is assumed that the destination knows the public key of the source.

- A digital signature may be formed by encrypting the entire message with the sender’s private key or by encrypting a hash code of the message with the sender’s private key

- Confidentiality can be provided by further encrypting the entire message plus signature with either the receiver’s public key (public-key encryption) or a shared secret key (symmetric encryption);

- It is important to perform the signature function first and then an outer confidentiality function.

- In case of dispute, some third party must view the message and its signature.

- If the signature is calculated on an encrypted message, then the third party also needs access to the decryption key to read the original message.

- However, if the signature is the inner operation, then the recipient can store the plaintext message and its signature for later use in dispute resolution.

Limitations:

- The validity of the scheme depends on the security of the sender’s private key.

- If a sender later wishes to deny sending a particular message, the sender can claim that the private key was lost or stolen and that someone else forged his or her signature.

- Administrative controls relating to the security of private keys can be employed to thwart or at least weaken this ploy, but the threat is still there, at least to some degree.

- One example is to require every signed message to include a timestamp (date and time) and to require prompt reporting of compromised keys to a central authority.

- Another threat is that some private key might actually be stolen from X at time T. The opponent can then send a message signed with X’s signature and stamped with a time before or equal to T.

Arbitrated Digital Signature

- The problems associated with direct digital signatures can be addressed by using an arbiter.

- Every signed message from a sender X to a receiver Y goes first to an arbiter A, who subjects the message and its signature to a number of tests to check its origin and content.

- The message is then dated and sent to Y with an indication that it has been verified to the satisfaction of the arbiter.

- The presence of A solves the problem faced by direct signature schemes: that X might disown the message.

- The arbiter plays a sensitive and crucial role in this sort of scheme, and all parties must have a great deal of trust that the arbitration mechanism is working properly.

- In the first, symmetric encryption is used. It is assumed that the sender X and the arbiter A share a secret key Kxa and that A and Y share secret key Kay.

- X constructs a message M and computes its hash value H(M).

- Then X transmits the message plus a signature to A.

- The signature consists of an identifier IDX of X plus the hash value, all encrypted using Kxa.

- A decrypts the signature and checks the hash value to validate the message.

- Then A transmits a message to Y, encrypted with Kay. The message includes IDX, the original message from X, the signature, and a timestamp.

- Y can decrypt this to recover the message and the signature.

- The timestamp informs Y that this message is timely and not a replay. Y can store M and the signature.

- In case of dispute, Y, who claims to have received M from X, sends the following message to A:

- The following format is used. A communication step in which P sends a messageM to Q is represented as P Q: M.

- E(Kay, [IDX||M||E(Kxa, [IDX||H(M)])])

Arbitrated Digital Signature Techniques

(a) Conventional Encryption, Arbiter Sees Message

(1) X A: M||E(Kxa,, [IDX||H(M)])

A: M||E(Kxa,, [IDX||H(M)])

(2) A Y: EKay, [IDX||M||E(Kxa,, [IDX||H(M)])||T])

Y: EKay, [IDX||M||E(Kxa,, [IDX||H(M)])||T])

(b) Conventional Encryption, Arbiter Does Not See Message

(1) X A: IDX||E(Kxy, M)||E(Kxa, [IDX||H(E(Kxy, M))])

A: IDX||E(Kxy, M)||E(Kxa, [IDX||H(E(Kxy, M))])

(2) A Y: EKay,[IDX||E(Kxy, M)])||E(Kxa, [IDX||H(E(Kxy, M))||T])

Y: EKay,[IDX||E(Kxy, M)])||E(Kxa, [IDX||H(E(Kxy, M))||T])

(c) Public-Key Encryption, Arbiter Does Not See Message

(1) X A: IDX||E(KRx, [IDX||E(PUy, E(KRx, M))])

A: IDX||E(KRx, [IDX||E(PUy, E(KRx, M))])

(2) A Y: EKRa, [IDX||E(PUy, E(PRx, M))||T])

Y: EKRa, [IDX||E(PUy, E(PRx, M))||T])

Notation:

X = sender

Y = recipient

A = Arbiter

M = message

T = timestamp

The arbiter uses Kay to recover IDX, M, and the signature, and then uses Kxa to decrypt the signature and verify the hash code.

In this scheme, Y cannot directly check X’s signature; the signature is there solely to settle disputes. Y considers the message from X authentic because it comes through A.

In this scenario, both sides must have a high degree of trust in A:

X must trust A not to reveal Kxa and not to generate false signatures of the form E(Kxa, [IDX||H(M)]). Y must trust A to send E(Kay, [IDX||M||E(Kxa, [IDX||H(M)])||T]) only if the hash value is correct and the signature was generated by X. Both sides must trust A to resolve disputes fairly.

If the arbiter does live up to this trust, then X is assured that no one can forge his signature and Y is assured that X cannot disavow his signature.

The preceding scenario also implies that A is able to read messages from X to Y and, indeed, that any eavesdropper is able to do so.

In fig B. shows a scenario that provides the arbitration as before but also assures confidentiality. In this case it is assumed that X and Y share the secret key Kxy. Now, X transmits an identifier, a copy of the message encrypted with K xy, and a signature to A. The signature consists of the identifier plus the hash value of the encrypted message, all encrypted using Kxa. As before, A decrypts the signature and checks the hash value to validate the message. In this case, A is working only with the encrypted version of the message and is prevented from reading it. A then transmits everything that it received from X, plus a timestamp, all encrypted with Kay, to Y.

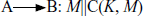

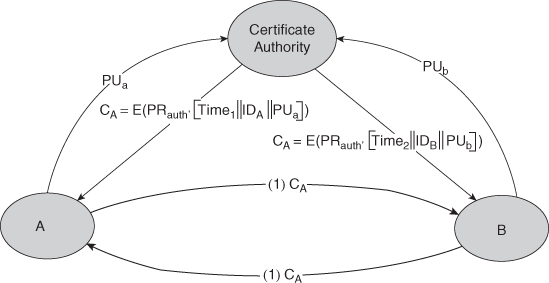

7. Describe briefly about X.509 authentication procedures. And also list out the drawbacks of X.509 version 2.

Ans: X.509 is based on the use of public-key cryptography and digital signatures. The standard does not dictate the use of a specific algorithm but recommends RSA. The digital signature scheme is assumed to require the use of a hash function. Again, the standard does not dictate a specific hash algorithm.

Certificates

The heart of the X.509 scheme is the public-key certificate associated with each user. These user certificates are assumed to be created by some trusted certification authority (CA) and placed in the directory by the CA or by the user. The directory server itself is not responsible for the creation of public keys or for the certification function; it merely provides an easily accessible location for users to obtain certificates.

It shows the general format of a certificate, which includes the following elements:

Version: Differentiates among successive versions of the certificate format; the default is version 1. If the Issuer Unique Identifier or Subject Unique Identifier are present, the value must be version 2. If one or more extensions are present, the version must be version 3.

Serial number: An integer value, unique within the issuing CA, that is unambiguously associated with this certificate.

Signature algorithm identifier: The algorithm used to sign the certificate, together with any associated parameters. Because this information is repeated in the Signature field at the end of the certificate, this field has little, if any, utility.

Issuer name: X.500 name of the CA that created and signed this certificate.

Period of validity: Consists of two dates: the first and last on which the certificate is valid.

Subject name: The name of the user to whom this certificate refers. That is, this certificate certifies the public key of the subject who holds the corresponding private key.

Subject’s public-key information: The public key of the subject, plus an identifier of the algorithm for which this key is to be used, together with any associated parameters.

Issuer unique identifier: An optional bit string field used to identify uniquely the issuing CA in the event the X.500 name has been reused for different entities.

Subject unique identifier: An optional bit string field used to identify uniquely the subject in the event the X.500 name has been reused for different entities.

Extensions: A set of one or more extension fields. Extensions were added in version 3 .

Signature: Covers all of the other fields of the certificate; it contains the hash code of the other fields, encrypted with the CA’s private key. This field includes the signature algorithm identifier.

The unique identifier fields were added in version 2 to handle the possible reuse of subject and/or issuer names over time. These fields are rarely used.

The standard uses the following notation to define a certificate:

CA<<A>> = CA {V, SN, AI, CA, TA, A, Ap}

where

Y <<X>> = the certificate of user X issued by certification authority Y

Y {I} = the signing of I by Y. It consists of I with an encrypted hash code appended

The CA signs the certificate with its private key. If the corresponding public key is known to a user, then that user can verify that a certificate signed by the CA is valid.

Obtaining a User’s Certificate

User certificates generated by a CA have the following characteristics:

- Any user with access to the public key of the CA can verify the user public key that was certified.

- No party other than the certification authority can modify the certificate without this being detected.

- Because certificates are unforgeable, they can be placed in a directory without the need for the directory to make special efforts to protect them.

- If all users subscribe to the same CA, then there is a common trust of that CA. All user certificates can be placed in the directory for access by all users. In addition, a user can transmit his or her certificate directly to other users. In either case, once B is in possession of A’s certificate, B has confidence that messages it encrypts with A’s public key will be secure from eavesdropping and that messages signed with A’s private key are unforgeable.

- If there is a large community of users, it may not be practical for all users to subscribe to the same CA. Because it is the CA that signs certificates, each participating user must have a copy of the CA’s own public key to verify signatures. This public key must be provided to each user in an absolutely secure (with respect to integrity and authenticity) way so that the user has confidence in the associated certificates. Thus, with many users, it may be more practical for there to be a number of CAs, each of which securely provides its public key to some fraction of the users.

- Now suppose that A has obtained a certificate from certification authority X1 and B has obtained a certificate from CA X2. If A does not securely know the public key of X2, then B’s certificate, issued by X2, is useless to A. A can read B’s certificate, but A cannot verify the signature. However, if the two CAs have securely exchanged their own public keys, the following procedure will enable A to obtain B’s public key:

A obtains, from the directory, the certificate of X2 signed by X1. Because A securely knows X1’s public key, A can obtain X2’s public key from its certificate and verify it by means of X1’s signature on the certificate.

1. A then goes back to the directory and obtains the certificate of B signed by X2 Because A now has a trusted copy of X2’s public key, A can verify the signature and securely obtain B’s public key.

2. A has used a chain of certificates to obtain B’s public key. In the notation of X.509, this chain is expressed as

X1<<X2>> X2 <<B>>

In the same fashion, B can obtain A’s public key with the reverse chain:

X2<<X1>> X1 <<A>>

This scheme need not be limited to a chain of two certificates. An arbitrarily long path of CAs can be followed to produce a chain. A chain with N elements would be expressed as

X1<<X2>> X2 <<X3>>... XN<<B>>

In this case, each pair of CAs in the chain (Xi, Xi+1) must have created certificates for each other. All these certificates of CAs by CAs need to appear in the directory, and the user needs to know how they are linked to follow a path to another user’s public-key certificate. X.509 suggests that CAs be arranged in a hierarchy so that navigation is straightforward.

CAs; the associated boxes indicate certificates maintained in the directory for each CA entry. The directory entry for each CA includes two types of certificates:

Forward certificates: Certificates of X generated by other CAs

Reverse certificates: Certificates generated by X that are the certificates of other CAs

Revocation of Certificates

Each certificate includes a period of validity, much like a credit card. Typically, a new certificate is issued just before the expiration of the old one. In addition, it may be desirable on occasion to revoke a certificate before it expires, for one of the following reasons:

1. The user’s private key is assumed to be compromised.

2. The user is no longer certified by this CA.

3. The CA’s certificate is assumed to be compromised.

Each CA must maintain a list consisting of all revoked but not expired certificates issued by that CA, including both those issued to users and to other CAs. These lists should also be posted on the directory.

Each certificate revocation list (CRL) posted to the directory is signed by the issuer and includes the issuer’s name, the date the list was created, the date the next CRL is scheduled to be issued, and an entry for each revoked certificate. Each entry consists of the serial number of a certificate and revocation date for that certificate. Because serial numbers are unique within a CA, the serial number is sufficient to identify the certificate.

When a user receives a certificate in a message, the user must determine whether the certificate has been revoked. The user could check the directory each time a certificate is received.

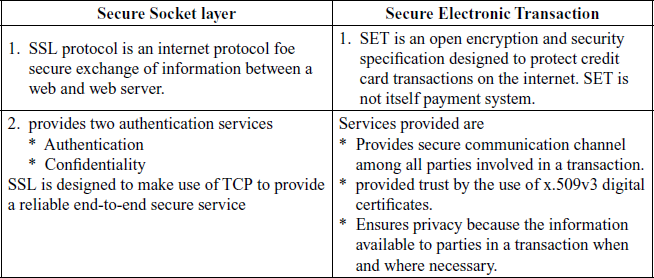

8. Write about SSL and TLS.

Ans: SSL (Secure Socket Layer):

- transport layer security service

- originally developed by Netscape

- version 3 designed with public input

- subsequently became Internet standard known as TLS (Transport Layer Security)

- uses TCP to provide a reliable end-to-end service

- SSL has two layers of protocols

SSL connection

- a transient, peer-to-peer, communications link

- associated with 1 SSL session

SSL session

- an association between client & server

- created by the Handshake Protocol

- define a set of cryptographic parameters

- may be shared by multiple SSL connections

SSL Record Protocol Services:

- message integrity

- using a MAC with shared secret key

- similar to HMAC but with different padding

- confidentiality

- using symmetric encryption with a shared secret key defined by Handshake Protocol

• AES, IDEA, RC2-40, DES-40, DES, 3DES, Fortezza, RC4-40, RC4-128

• message is compressed before encryption

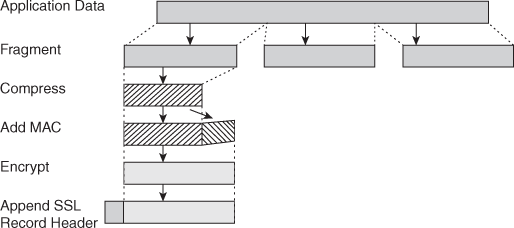

SSL Record Protocol Operation:

SSL Change Cipher Spec Protocol:

- one of 3 SSL specific protocols which use the SSL Record protocol

- a single message

- causes pending state to become current

- hence updating the cipher suite in use

SSL Alert Protocol:

- conveys SSL-related alerts to peer entity

- severity

- warning or fatal

- specific alert

- fatal: unexpected message, bad record mac, decompression failure, handshake failure, illegal parameter

- warning: close notify, no certificate, bad certificate, unsupported certificate, certificate revoked, certificate expired, certificate unknown

- compressed & encrypted like all SSL data

SSL Handshake Protocol:

- allows server & client to:

- authenticate each other

- to negotiate encryption & MAC algorithms

- to negotiate cryptographic keys to be used

- comprises a series of messages in phases

- Establish Security Capabilities

- Server Authentication and Key Exchange

- Client Authentication and Key Exchange

- Finish

Phase 1. Establish Security Capabilities

This phase is used to initiate a logical connection and to establish the security capabilities that will be associated with it. The exchange is initiated by the client, which sends a client_hello message with the following parameters:

Version: The highest SSL version understood by the client.

Random: A client-generated random structure, consisting of a 32-bit timestamp and 28 bytes generated by a secure random number generator. These values serve as nonces and are used during key exchange to prevent replay attacks.

Session ID: A variable-length session identifier. A nonzero value indicates that the client wishes to update the parameters of an existing connection or create a new connection on this session. A zero value indicates that the client wishes to establish a new connection on a new session.

CipherSuite: This is a list that contains the combinations of cryptographic algorithms supported by the client, in decreasing order of preference. Each element of the list (each cipher suite) defines both a key exchange algorithm and a CipherSpec;

Compression Method: This is a list of the compression methods the client supports.

Phase 2. Server Authentication and Key Exchange

The server begins this phase by sending its certificate, if it needs to be authenticated; the message contains one or a chain of X.509 certificates. The certificate message is required for any agreed-on key exchange method except anonymous Diffie-Hellman. If fixed Diffie-Hellman is used, this certificate message functions as the server’s key exchange message because it contains the server’s public Diffie-Hellman parameters. Next, a server_key_exchange message may be sent if it is required. It is not required in two instances:

(1) The server has sent a certificate with fixed Diffie-Hellman parameters, or

(2) RSA key exchange is to be used.

Phase 3. Client Authentication and Key Exchange

Upon receipt of the server_done message, the client should verify that the server provided a valid certificate if required and check that the server_hello parameters are acceptable. If all is satisfactory, the client sends one or more messages back to the server. If the server has requested a certificate, the client begins this phase by sending a certificate message. If no suitable certificate is available, the client sends a no_certificate alert instead. Next is the client_key_exchange message, which must be sent in this phase.

The content of the message depends on the type of key exchange, as follows:

RSA: The client generates a 48-byte pre-master secret and encrypts with the public key from the server’s certificate or temporary RSA key from a server_key_exchange message. Its use to compute a master secret.

Ephemeral or Anonymous Diffie-Hellman: The client’s public Diffie-Hellman parameters are sent.

Fixed Diffie-Hellman: The client’s public Diffie-Hellman parameters were sent in a certificate message, so the content of this message is null.

Fortezza: The client’s Fortezza parameters are sent.

Finally, in this phase, the client may send a certificate_verify message to provide explicit verification of a client certificate. This message is only sent following any client certificate that has signing capability (i.e., all certificates except those containing fixed Diffie-Hellman parameters).

Phase 4. Finish

This phase completes the setting up of a secure connection. The client sends a change_cipher_spec message and copies the pending CipherSpec into the current CipherSpec. Note that this message is not considered part of the Handshake Protocol but is sent using the Change Cipher Spec Protocol. The client then immediately sends the finished message under the new algorithms, keys, and secrets. The finished message verifies that the key exchange and authentication processes were successful.

9. Explain about intrusion detection techniques in detail.

Ans: Intrusion detection system can be broadly classified based on two parameters .

(a) Analysis method used to identify intrusion, which is classified into Misuse IDS and Anomaly IDS.

(b) Source of data that is used in the analysis method, which is classified into Host, based IDS and Network based IDS

2.1. Misuse IDS

Misuse based IDS is a very prominent system and is widely used in industries. Most of the organizations that develop anti-virus solutions base their design methodology on Misuse IDS. The system is constructed based on the signature of all-known attacks. Rules and signatures define abnormal and unsafe behavior. It analyzes the traffic flow over a network and matches against known signatures. Once a known signature is encountered the IDS triggers an alarm. With the advancement in latest technologies, the number of signatures also increase. This demands for constant upgrade and modification of new attack signatures from the vendors and paying more to vendors for their support [6].

- The advantages of this model are easy creation of attack signature databases, faster and easier implementation of IDS and minimal usage of the system resources.

- The main weakness of the traditional and established rule based techniques is that rule based detection is highly dependent on the audit results.

- This one-to-one correspondence between rules and audit records makes the system inflexible. For example, given a particular penetration scenario, the audit results may vary in the sequences of events. This results in variations in the detection outcome.

- This may lead to large number of false positives (Section 3) and in some cases, false negatives too.

- The inability to predict a mishap and take preemptive action. The rule-based technique only helps in prevention of an intrusion when the details and patterns of it are available.

- Rules are framed when a set of administrators are interviewed, different observed penetrations are recorded, rules are set to those penetration scenarios based on the expected outcomes from the analysis of audit records. Therefore, updating of rules is expensive in terms of time and money.

2.2. Anomaly IDS

Anomaly IDS is built by studying the behavior of the system over a period of time in order to construct activity profiles that represent normal use of the system. The anomaly IDS computes the similarity of the traffic in the system with the profiles to detect intrusions. The biggest advantage of this model is that new attacks can be identified by the system as it will be a deviation from normal behavior.

The drawbacks of this model are summarized

(a) There is no defined process or model available to select the threshold value against which the profile is compared.

(b) They are computationally expensive because the profiles have to be constantly updated and compared against.

(c) User behaviors generally vary with time and hence the model must provide a provision to revise and update it.

2.3. Host Based IDS

When the source of data for IDS comes from a single host (System), then it is classified as Host based IDS. They are generally used to monitor user activity and useful to track IDS intrusions caused when an authorized user tries to access confidential information.

2.4. Network Based IDS

The source of data for these type of IDS is obtained by listening to all nodes in a network. Attacks from illegitimate user can be identified using a network based IDS. Commercial IDSs are always a combination of the two types mentioned above. The possible kinds of IDS are host based misuse IDS, network based misuse IDS, host based anomaly IDS and network based anomaly IDS. However, with greater interest and research in this field, new models are being developed such as Network Security monitor.

10. Write about trusted systems in detail.

Ans: One way to enhance the ability of a system to defend against intruders and malicious programs is to implement trusted system technology

Data Access Control

Following successful logon, the user has been granted access to one or a set of hosts and applications. This is generally not sufficient for a system that includes sensitive data in its database. Through the user access control procedure, a user can be identified to the system. Associated with each user, there can be a profile that specifies permissible operations and file accesses. The operating system can then enforce rules based on the user profile. The database management system, however, must control access to specific records or even portions of records. For example, it may be permissible for anyone in administration to obtain a list of company personnel, but only selected individuals may have access to salary information. The issue is more than just one of level of detail. Whereas the operating system may grant a user permission to access a file or use an application, following which there are no further security checks, the database management system must make a decision on each individual access attempt. That decision will depend not only on the user’s identity but also on the specific parts of the data being accessed and even on the information already divulged to the user.

A general model of access control as exercised by a file or database management system is that of an access matrix

The basic elements of the model are as follows:

Subject: An entity capable of accessing objects. Generally, the concept of subject equates with that of process. Any user or application actually gains access to an object by means of a process that represents that user or application.

Object: Anything to which access is controlled. Examples include files, portions of files, programs, and segments of memory.

Access right: The way in which an object is accessed by a subject. Examples are read, write, and execute.

When multiple categories or levels of data are defined, the requirement is referred to as multilevel security. The general statement of the requirement for multilevel security is that a subject at a high level may not convey information to a subject at a lower or noncomparable level unless that flow accurately reflects the will of an authorized user. For implementation purposes, this requirement is in two parts and is simply stated. A multilevel secure system must enforce the following:

No read up: A subject can only read an object of less or equal security level. This is referred to in the literature as th SimpleSecurity Property.

No write down: A subject can only write into an object of greater or equal security level. This is referred to in the literature as the *-Property

[1] The “*” does not stand for anything. No one could think of an appropriate name for the property during the writing of the first report on the model. The asterisk was a dummy character entered in the draft so that a text editor could rapidly find and replace all instances of its use once the property was named. No name was ever devised, and so the report was published with the “*” intact.

These two rules, if properly enforced, provide multilevel security. For a data processing system, the approach that has been taken, and has been the object of much research and development, is based on the reference monitor concept.

The reference monitor is a controlling element in the hardware and operating system of a computer that regulates the access of subjects to objects on the basis of security parameters of the subject and object. The reference monitor has access to a file, known as the security kernel database, that lists the access privileges (security clearance) of each subject and the protection attributes (classification level) of each object. The reference monitor enforces the security rules (no read up, no write down) and has the following properties:

Complete mediation: The security rules are enforced on every access, not just, for example, when a file is opened.

Isolation: The reference monitor and database are protected from unauthorized modification.

Verifiability: The reference monitor’s correctness must be provable. That is, it must be possible to demonstrate mathematically that the reference monitor enforces the security rules and provides complete mediation and isolation.

These are stiff requirements. The requirement for complete mediation means that every access to data within main memory and on disk and tape must be mediated. Pure software implementations impose too high a performance penalty to be practical; the solution must be at least partly in hardware. The requirement for isolation means that it must not be possible for an attacker, no matter how clever, to change the logic of the reference monitor or the contents of the security kernel database. Finally, the requirement for mathematical proof is formidable for something as complex as a general-purpose computer. A system that can provide such verification is referred to as a trusted system.

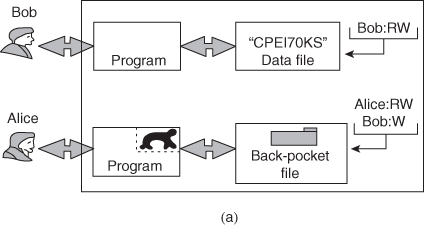

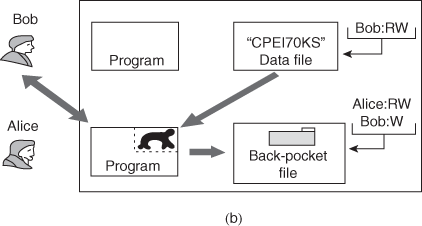

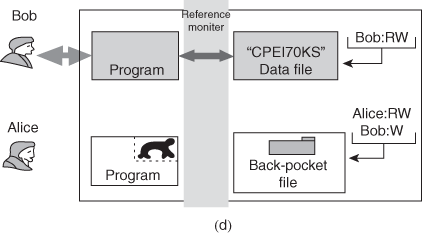

Trojan Horse Defense

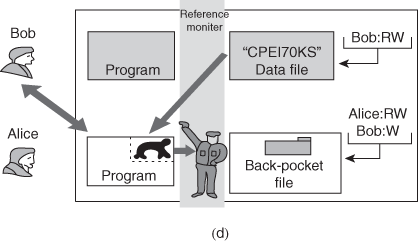

One way to secure against Trojan horse attacks is the use of a secure, trusted operating system. Figure illustrates an example. In this case, a Trojan horse is used to get around the standard security mechanism used by most file management and operating systems: the access control list. In this example, a user named Bob interacts through a program with a data file containing the critically sensitive character string “CPE170KS.” User Bob has created the file with read/write permission provided only to programs executing on his own behalf: that is, only processes that are owned by Bob may access the file.

The Trojan horse attack begins when a hostile user, named Alice, gains legitimate access to the system and installs both a Trojan horse program and a private file to be used in the attack as a “back pocket.” Alice givesread/write permission to herself for this file and gives Bob write-only permission .Alice now induces Bob to invoke the Trojan horse program, perhaps by advertising it as a useful utility. When the program detects that it is being executed by Bob, it reads the sensitive character string from Bob’s file and copies it into Alice’s back-pocket file (Figure). Both the read and write operations satisfy the constraints imposed by access control lists. Alice then has only to access Bob’s file at a later time to learn the value of the string. Now consider the use of a secure operating system in this scenario .Security levels are assigned to subjects at logon on the basis of criteria such as the terminal from which the computer is being accessed and the user involved, as identified by password/ID. In this example, there are two security levels, sensitive and public, ordered so that sensitive is higher than public. Processes owned by Bob and Bob’s data file are assigned the security level sensitive. Alice’s file and processes are restricted to public. If Bob invokes the Trojan horse program , that program acquires Bob’s security level. It is therefore able, under the simple security property, to observe the sensitive character string. When the program attempts to store the string in a public file (the back-pocket file), however, the is violated and the attempt is disallowed by the reference monitor. Thus, the attempt to write into the back-pocket file is denied even though the access control list permits it: The security policy takes precedence over the access control list mechanism.

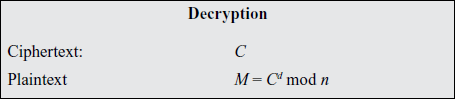

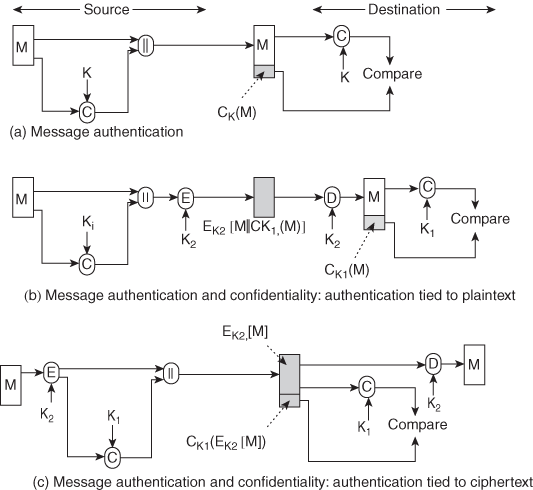

11. Explain the Key Generation, Encryption and Decryption of SDES algorithm in detail.

Ans: Simplified DES

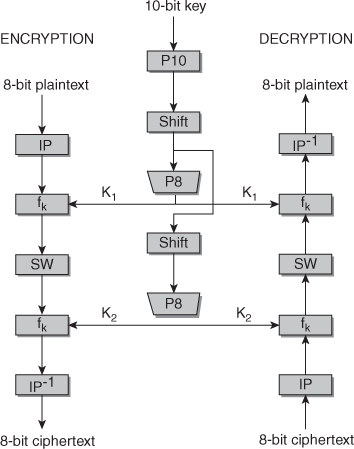

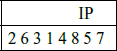

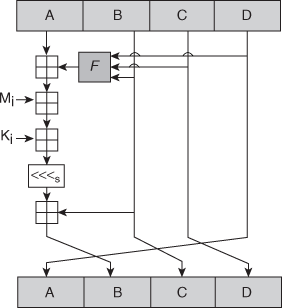

S-DES encryption (decryption) algorithm takes 8-bit block of plaintext (ciphertext) and a 10-bit key, and produces 8-bit ciphertext (plaintext) block. Encryption algorithm involves 5 functions: an initial permutation (IP); a complex function fK, which involves both permutation and substitution and depends on a key input; a simple permutation function that switches (SW) the 2 halves of the data; the function fK again; and finally, a permutation function that is the inverse of the initial permutation (IP-1). Decryption process is similar.

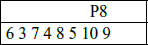

The function fK takes 8-bit key which is obtained from the 10-bit initial one two times. The key is first subjected to a permutation P10. Then a shift operation is performed. The output of the shift operation then passes through a permutation function that produces an 8-bit output (P8) for the first subkey (K1). The output of the shift operation also feeds into another shift and another instance of P8 to produce the 2nd subkey K2.

We can express encryption algorithm as superposition:

Ciphertext= IP-1 (fk2.SW.fk1.IP) or IP-1(fk2 (SW (fk1 (IP(plaintext))))

Where

k1=P8(shift(P10(key)))

k2= P8(shift(shift(P10(key)))

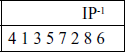

Decryption is the reverse of encryption:

Plaintext= (IP-1(fk1 (SW (fk2 (IP(ciphertext))))

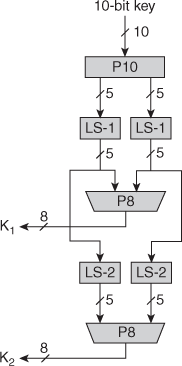

S-DES key generation

Scheme of key generation:

Figure Key Generation for Simplified DES

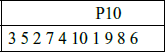

First, permute the 10-bit key k1,k2,..,k10:

P10(k1,k2,k3,k4,k5,k6,k7,k8,k9,k10)=(k3,k5,k2,k7,k4,k10,k1,k9,k8,k6)

Or it may be represented in such a form

Each position in this table gives the identity of the input bit that produces the output bit in this position. So, the 1st output bit is bit 3 (k3), the 2nd is k5 and so on. For example, the key (1010000010) is permuted to (1000001100).

Next, perform a circular shift (LS-1), or rotation, separately on the 1st 5 bits and the 2nd 5 bits. In our example, the result is (00001 11000)

Next, we apply P8, which picks out and permutes 8 out of 10 bits according to the following rule:

The result is subkey K1. In our example, this yields (10100100)

We then go back to the pair of 5-bit strings produced by the 2 LS-1 functions and perform a circular left shift of 2 bit positions on each string. In our example, the value (00001 11000) becomes (00100 00011). Finally, P8 is applied again to produce K2. In our example, the result is (01000011)

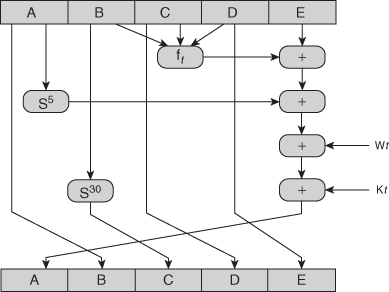

S-DES encryption

Simplified-DES encryption Detail

The input to the algorithm is an 8-bit block of plaintext, which is permuted by IP function:

At the end of the algorithm, the inverse permutation is used:

It may be verified, that IP-1(IP(X)) = X.

The most complex component of S-DES is the function fK, which consists of a combination of permutation and substitution functions. The function can be expressed as follows. Let L and R be the leftmost 4 bits and rightmost 4 bits of the 8-bit input to fK, and let F be a mapping (not necessarily one to one) from 4-bit strings to 4-bit strings. Then we let fK(L,R) = (L⊕F(R,SK),R)

where SK is a subkey and ⊕ is the bit-by-bit XOR operation. For example, suppose the output of the IP stage in Fig.3.3 is (1011 1101) and F(1101,SK) = (1110) for some key SK. Then fK(1011 1101) = (0101 1101) because (1011) ⊕ (1110) = (0101).

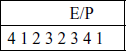

We now describe the mapping F. The input is a 4-bit number (n1 n2 n3 n4). The 1st operation is an expansion/permutation:

For what follows, it is clearer to depict result in this fashion:

n4|n1 n2|n3

n2|n3 n4|n1

The 8-bit subkey K1 = (k11, k12, k13, k14, k15, k16, k17, k18) is added to this value using XOR:

4+k11|n1+k12 n2+k13|n3+k14

n2+k15|n3+k16 n4+k17|n1+k18

Let us rename these bits:

p00|p01 p02|p03

p10|p11 p12|p13

The 1st 4 bits (1st row of the preceding matrix) are fed into the S-box S0 to produce a 2-bit output, and the remaining 4 bits (2nd row) are fed into S1 to produce another 2-bit output. These 2 boxes are defined as follows:

0 12 3 0 12 3

The S-boxes operate as follows. The 1st and 4th input bits are treated as a 2-bit number that specify a row of the S-box, and the 2nd and 3rd input bits specify a column of the S-box. The entry in that row and column, in base 2, is the 2-bit output. For example, if (p00, p03) = (00) and (p01, p02) = (10), then the output is from row 0, column 2 of S0, which is 3, or (11) in binary. Similarly, (p10, p13) and (p11, p12) are used to index into a row and column of S1 to produce an additional 2 bits.

Next, the 4 bits produced by S0 and S1 undergo a further permutation as follows:

The output of P4 is the output of function F.

The function fK only alters the leftmost 4 bits of input.

The switch function SW interchanges the left and right bits so that the 2nd instance of fK operates on a different 4 bits. In the 2nd instance, the E/P, S0, S1, and P4 functions are the same. The key input is K2.

Analysis of simplified DES

A brute-force attack on S-DES is feasible since with a 10-bit key there are only 1024 possibilities.

What about cryptanalysis? If we know plaintext (p1p2p3p4p5p6p7p8) and respective ciphertext (c1c2c3c4c5c6c7c8), and key (k1k2k3k4k5k6k7k8k9k10) is unknown, then we can express this problem as a system of 8 nonlinear equations with 10 unknowns. The nonlinearity comes from the S-boxes. It is useful to write down equations for these boxes. For clarity, rename (p00,p01,p02,p03)=(a,b,c,d) and (p10,p11,p12,p13)=(w,x,y,z). Then the operation of S0 is defined in the following equations:

q=abcd+ab+ac+b+d

r=abcd+abd+ab+ac+ad+a+c+1

where all additions are made modulo 2. Similar equations define S1.

12. Write the algorithm of RSA and explain with an example.

Ans: Diffie and Hellman introduced a new approach to cryptography and, in effect, challenged cryptologists to come up with a cryptographic algorithm that met the requirements for public-key systems. One of the first of the responses to the challenge was developed in 1977 by Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Len Adleman at MIT .

The RSA scheme is a block cipher in which the plaintext and ciphertext are integers between 0 and n 1 for some n. A typical size for n is 1024 bits, or 309 decimal digits. That is, n is less than 21024.

Description of the Algorithm