In this section, we will see how padding works in the PKCS # 7 system and then show you a system with the PADDING ERROR message. Plus, we'll also deal with the padding oracle attack, which makes it possible to craft ciphertext that will decode 20 plaintext we want.

Here is the encryption routine:

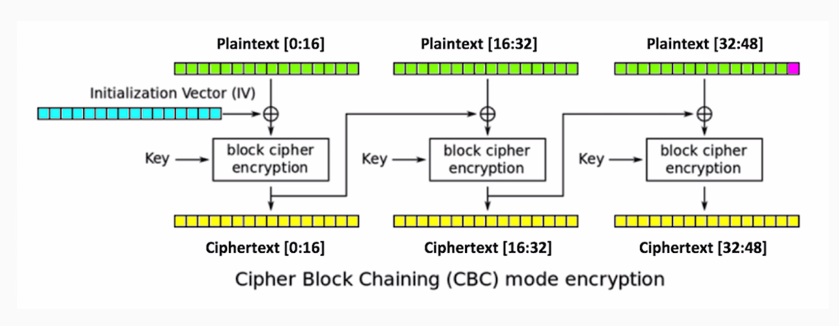

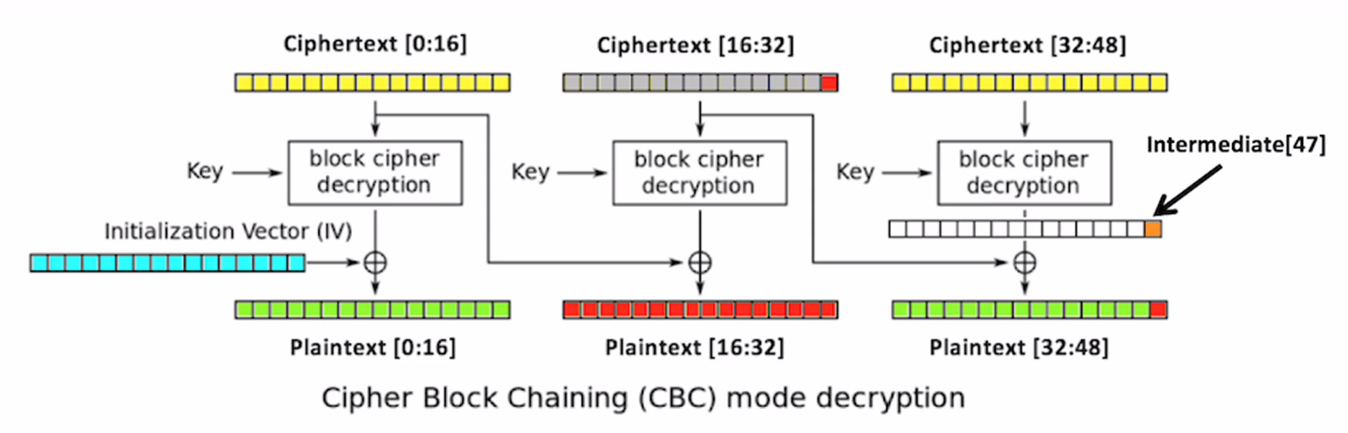

We'll have three blocks of data, each 16-bytes long. We'll encrypt the data with AES in CBC mode, so in comes the initialization vector and the key. You produce three blocks of ciphertext, and each one of the blocks after the first uses the output of the previous encryption routine as an initialization vector to XOR with the plaintext.

Here's how PKCS#7 padding works:

- If one byte of padding is needed, use 01

- If two bytes of padding are needed, use 0202

- If three bytes of padding are needed, use 030303

- And so on...

If we have a message here that is only 47-bytes long, then we can't fill the last block, so we have to add a byte of padding. You could use a variety of numbers as the padding, but in this system, we use one binary value one, if you have one byte of padding needed if you have two, you use two for both bytes and three for all three bytes for three bytes of padding and so on. This means that, if we decrypt it, we'll have three blocks of ciphertext. We decrypt it and we'll get the 47-byte message:

The last byte here will always be the padding byte, and that will be 0-1, a binary value of 1.

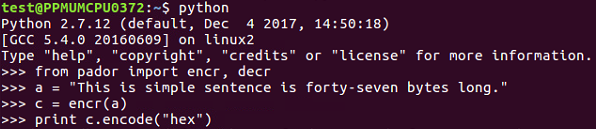

Here is an example of a vulnerable system that you can attack. This is just using the same techniques we've made before where we just encrypt things with AES and CBC mode, which you can save in pador.py, and then you can just import it to make it easy to use and more realistic. There have been real systems that use this. So, we import, encrypt, and decrypt methods so that we can put in a 47-pipe message and encrypt it. We'll get a long blob of hexadecimal output.

If we decrypt that, we will get our original input plus one byte of 01 at the end. x01 is the Python notation for a single byte with the binary value of 1. If you modify the input by keeping the first 47 bytes alone and changing the last byte to A or 65 and decrypt it, you'll get a padding error. This error message may seem harmless, but in fact it makes it possible to completely subvert the encryption.

Let's take a look at that:

- Open the Terminal and start python.

- We will enter the following command:

- We will encrypt and decrypt routines. You can see we have the plaintext. When we encrypt 47 bytes of plaintext, we get a long binary blob:

941dc2865db9204c40dd6f0898cbe0086fc6d915e288ed4ef223766a02967b81c6c431778a40f517e9e4aa86856e0a3b68297e102b1ec93713bf89750cdfa80e

- When we decrypt that, we get the following:

We can see that it in fact added the single byte of padding at the end of it.

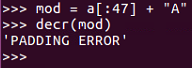

Now, we should do the deformed one. If we set our modified text equal to the original plaintext going up to character 47 and then we add "A" at the end, when we decrypt it, we get 'PADDING ERROR':

That is the error message that we can exploit to subvert the system. So, here's how the padding oracle attacked works change:

- Change ciphertext [16:31] to any bytes

- Change ciphertext [31] until padding is valid

- Intermediate [47] must be 1

Here is a diagram of CBC:

Leave the first 16 bytes of the ciphertext alone. Change this to anything you like, such as all-As, and then decrypt that. What will happen is, because you changed the bytes in the second block, the second block will turn to random characters, and so will the third block. But it'll give you a padding error unless the, very last byte of the very last block is one. So, you brute force it. You change a byte to all 256 possible values until the byte becomes 1, and when that happens, you know this value is 1. You know this value because it's the one that did not give you a padding error message, and you can XOR them to determine this intermediate value right here. So, proceeding byte by byte to the left, you can determine these intermediate values. If you know them, you can put in ciphertext that will make anything you like appear in the third block. So, you can defeat the encryption even though you don't know the key or the initialization vector.

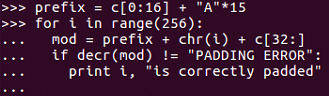

Here's the code that does it:

And will get the following output:

We set the ciphertext equal to the first original 16 bytes of ciphertext and then 15 bytes of A. Then we vary the next byte through all possible 256 values and add the third block of data unchanged. After that, we look to see when we no longer get a padding error, and that will be 234, so the intermediate value is 234 XOR one:

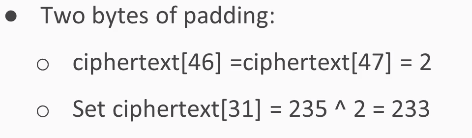

- Now, if we want to get the next byte back, we have to arrange two bytes of padding, both of which will be 2, as shown:

So, the final two bytes of ciphertext 46 and 47 will both be two. So, we set ciphertext 31 to the value needed to create two there. Now that we know the intermediate value, we can calculate it.

- We vary ciphertext 30 until the padding is valid and that will determine the next byte of the intermediate:

- Leave the first block unchanged and add 14 bytes of a vary the next byte. Leave the byte at the chosen value of 233 so you know that the final byte of the decrypted output will be 2, and when the padding error message goes away, you can take that number, XOR it with 2, and you get the next value of the intermediate. So, now we can make messages. We would have to repeat this more times to get more bytes, but for this demonstration, we'll settle for a message just one letter long. We'll make an A followed by a binary value of 1 for valid padding. That's our goal, and in order to do that, all we have to do is set ciphertext 30 and 31 to these chosen values:

- ciphertext[30] = ord("A") ^ 113

- ciphertext[31] = 16 235

- Since we know the intermediate values are 113 and 235, we just need to XOR these intermediate values with the values we want.

- We will create ciphertext that will decrypt to a message ending in A and a binary 1, so let's see that go. Now, this one is a little complicated, so we've chosen to save some of the text here in a text editor so we can do it stage by stage:

- Here's our Python:

>>> from pador import encr, decr

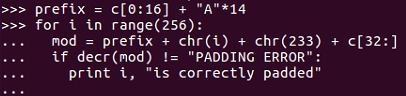

>>> prefix = c[0:16] + "A"*14

>>> for i in range(256):

... mod = prefix + chr(i) + chr(233) + c[32:]

... if decr(mod) != "PADDING ERROR":

... print i, "is correctly padded"

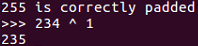

- Alright, we import the library, which we already had anyway. Here we leave the first 16 bytes unchanged and fill in 15 bytes with A. Then, we have the loop that changes the next byte's every possible value and leave the third block of data unchanged. We run through the loop until we no longer get a padding error. This tells us that 234 is the value that gives us correct padding:

234 is correctly padded

- So, we take 234 to the 1, which tells us the intermediate value, all over cut the indentation right, so it's 234 XOR 1. This tells us that the value is 235. That's the intermediate value. For the next bit, use a very similar process, so now we have 14 bytes of padding. We will vary the next byte, and the byte after that is 233, which is chosen to always give us a 2 at the end. So, when we run this loop through, it is correctly padded at 115:

...

115 is correctly padded

- So, 115 XOR 2 is 113:

>>> 115 ^ 2

113

Therefore, 113 is the next byte of intermediate value.

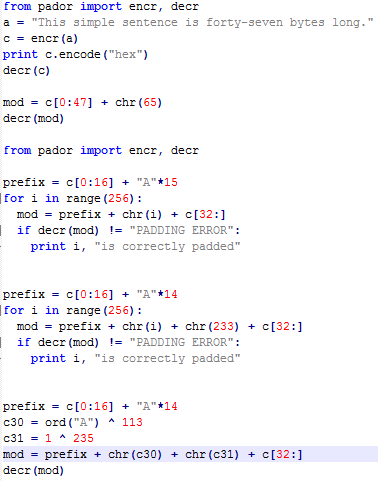

- Now that we know these two numbers, 235 and 113, we can control the last two bytes of plaintext. Now we will keep the first block of input data unchanged. We have 14 bytes of padding:

>>> prefix = c[0:16] + "A"*14

>>> c30 = ord("A") ^ 113

>>> c31 = 1 ^ 235 mod = prefix + chr(c30) + chr(c31) + c[32:]

>>> decr(mod)

- We choose to make A and a binary one with the two bytes, 235 and 113. When we create the modified ciphertext and decrypt it, we get the following message:

"This simple sent\xc6\x8d\x12;y.\xdc\xa2\xb4\xa9)7c\x95b\xd1I\xd0(\xbb\x1f\x8d\xebRlY'\x17\xf6wA\x01"

The first block of data is unmodified. The second block and most of the third block have changed to random characters, but we controlled the last two bytes and we could make them say anything we wanted. So, we are able to create ciphertext that will decrypt at least partly two values we choose, even though we don't know the key or the initialization vector.