Command line arguments are required for the following reasons:

- They inform the utility or command as to which file or group of files to process (reading/writing of files)

- Command line arguments tell the command/utility which option to use

Check the following command line:

student@ubuntu:~$ my_program arg1 arg2 arg3

If my_command is a bash Shell script, then we can access every command line positional parameters inside the script as follows:

$0 would contain "my_program" # Command $1 would contain "arg1" # First parameter $2 would contain "arg2" # Second parameter $3 would contain "arg3" # Third parameter

The following is the summary of positional parameters:

|

$0 |

Shell script name or command |

|

$1–$9 |

Positional parameters 1–9 |

|

${10} |

Positional parameter 10 |

|

$# |

Total number of parameters |

|

$* |

Evaluates to all the positional parameters |

|

$@ |

Same as $*, except when double quoted |

|

"$*" |

Displays all parameters as "$1 $2 $3", and so on |

|

"$@" |

Displays all parameters as "$1" "$2" "$3", and so on |

Let's create a script param.sh as follows:

#!/bin/bash echo "Total number of parameters are = $#" echo "Script name = $0" echo "First Parameter is $1" echo "Second Parameter is $2" echo "Third Parameter is $3" echo "Fourth Parameter is $4" echo "Fifth Parameter is $5" echo "All parameters are = $*"

Then as usual, give execute permission to script and then execute it:

./parameter.sh London Washington Delhi Dhaka Paris

Output:

Total number of parameters are = 5 Command is = ./parameter.sh First Parameter is London Second Parameter is Washington Third Parameter is Delhi Fourth Parameter is Dhaka Fifth Parameter is Paris All parameters are = London Washington Delhi Dhaka Paris

Many times we may not pass arguments on the command line, but we may need to set parameters internally inside the script.

We can declare parameters by the set command as follows:

$ set USA Canada UK France $ echo $1 USA $ echo $2 Canada $ echo $3 UK $ echo $4 France

We can use this inside the set_01.sh script as follows:

#!/bin/bash set USA Canada UK France echo $1 echo $2 echo $3 echo $4

Run the script as:

$ ./set.sh

Output:

USA Canada UK France

|

Table declare Options | |

|---|---|

|

Option |

Meaning |

|

–a | |

|

–f | |

|

–F | |

|

–i | |

|

–r | |

|

–x | |

We give commands as follows:

set One Two Three Four Five echo $0 # This will show command echo $1 # This will show first parameter echo $2 echo $* # This will list all parameters echo $# # This will list total number of parameters echo ${10} ${11} # Use this syntax for parameters for 10th and # 11th parameters

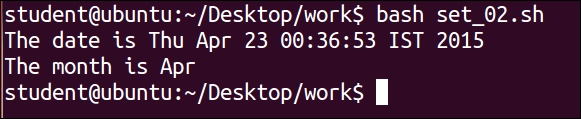

Let us write script set_02.sh as follows:

#!/bin/bash echo The date is $(date) set $(date) echo The month is $2 exit 0

Output:

In the script $(date), the command will execute and the output of that command will be used as $1, $2, $3 and so on. We have used $2 to extract the month from the output.

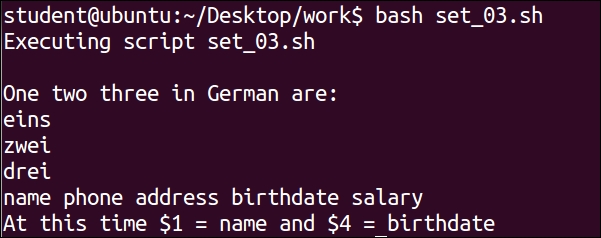

Let's write script set_03.sh as follows:

#!/bin/bash echo "Executing script $0" echo $1 $2 $3 set eins zwei drei echo "One two three in German are:" echo "$1" echo "$2" echo "$3" textline="name phone address birthdate salary" set $textline echo "$*" echo 'At this time $1 = ' $1 'and $4 = ' $4

Output:

Using shift, we can change the parameter to which $1 and $2 are pointing to the next variable.

Create a script shift_01.sh as follows:

#!/bin/bash echo "All Arguments Passed are as follow : " echo $* echo "Shift By one Position :" shift echo "Value of Positional Parameter $ 1 after shift :" echo $1 echo "Shift by Two Positions :" shift 2 echo "Value of Positional Parameter $ 1 After two Shifts :" echo $1

Execute the command as follows:

$ chmod +x shift_01.sh $ ./shift_01.sh One Two Three Four

Output:

student@ubuntu$ ./shift_01.sh One Two Three Four

All arguments passed are as follows:

One Two Three Four

Shift by one position.

Here, the value of the positional parameter $1 after shift is:

Two

Shift by two positions.

The value of the positional parameter $1 after two shifts:

Four

We observed that initially $1 was One. After shift, $1 will be pointing to Two. Once shift is done, the value in position 1 is always destroyed and is inaccessible.

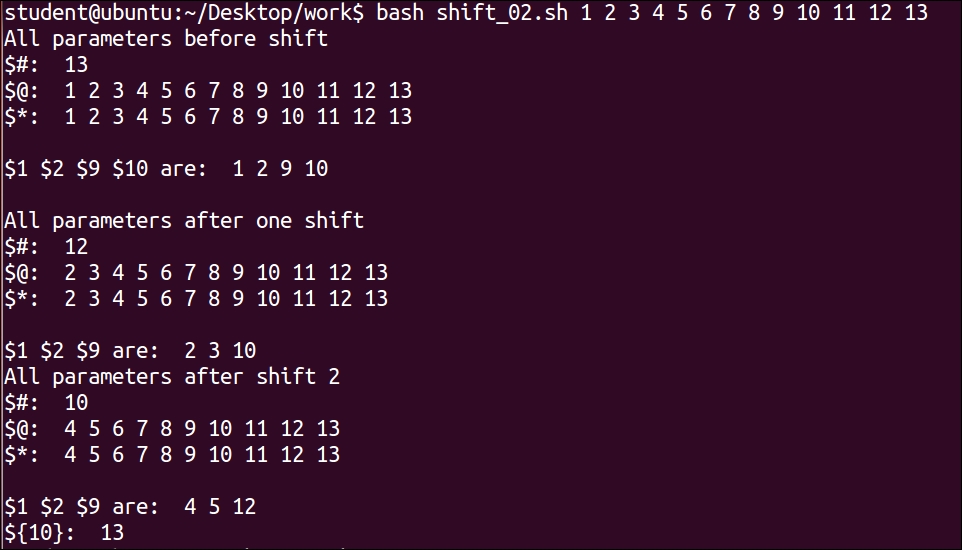

Create a shift_02.sh script as follows:

#!/bin/bash

echo '$#: ' $#

echo '$@: ' $@

echo '$*: ' $*

echo

echo '$1 $2 $9 $10 are: ' $1 $2 $9 $10

echo

shift

echo '$#: ' $#

echo '$@: ' $@

echo '$*: ' $*

echo

echo '$1 $2 $9 are: ' $1 $2 $9

shift 2

echo '$#: ' $#

echo '$@: ' $@

echo '$*: ' $*

echo

echo '$1 $2 $9 are: ' $1 $2 $9

echo '${10}: ' ${10}

In this script execution, the following output shows:

- Initially,

$1to$13were numerical values 1 to 13, respectively. - When we called the command shift, then

$1shifted to number2and accordingly all $numbers are shifted. - When we called the command shift

2, then$1shifted to number 4 and accordingly all $numbers are shifted.

In certain situations, we may need to reset original positional parameters.

Let's try the following:

set Alan John Dennis

This will reset the positional parameters.

Now $1 is Alan, $2 is John, and $3 is Dennis.

Inside the scripts, we can save positional parameters in a variable as follows:

oldargs=$*

Then, we can set new positional parameters.

Later on, we can bring back our original positional parameters as follows:

set $oldargs