In the last chapter, we introduced ourselves to the Bash shell environment in Linux. You learned basic commands and wrote your first Shell script as well.

You also learned about process management and job control. This information will be very useful for system administrators in automation and solving many problems.

In this chapter, we will cover the following topics:

- Monitoring processes with ps

- Job management—working with fg, bg, jobs, and kill

- Exploring at and crontab

A running instance of a program is called as process. A program stored in the hard disk or pen drive is not a process. When that stored program starts executing, then we say that process has been created and is running.

Let's very briefly understand the Linux operating system boot-up sequence:

- In PCs, initially the BIOS chip initializes system hardware, such as PCI bus, display device drivers, and so on.

- Then the BIOS executes the boot loader program.

- The boot loader program then copies kernel in memory, and after basic checks, it calls a kernel function called

start_kenel(). - The kernel then initiates the OS and creates the first process called

init. - You can check the presence of this process with the following command:

$ ps –ef - Every process in the OS has one numerical identification associated with it. It is called a process ID. The process ID of the

initprocess is 1. This process is the parent process of all user space processes. - In the OS, every new process is created by a system call called

fork(). - Therefore, every process has a process ID as well as the parent process ID.

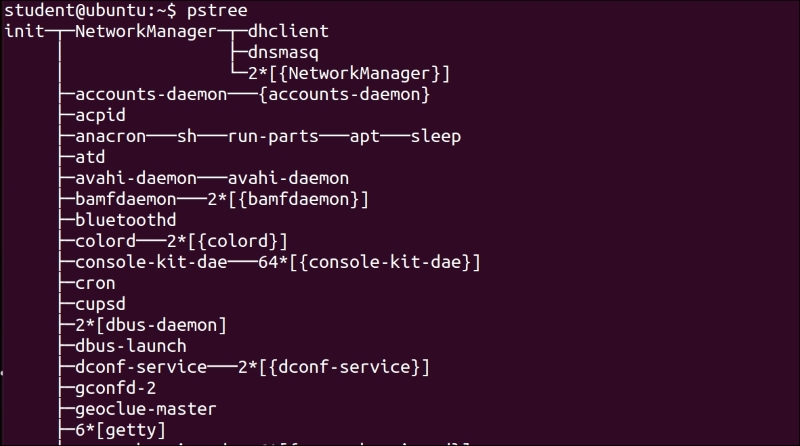

- We can see the complete process tree using the following command:

$ pstree

You can see the very first process as init as well as all other processes with a complete parent and child relation between them. If we use the $ps –ef command, then we can see that the init process is owned by root and its parent process ID is 0. This means that there is no parent for init:

Therefore, except the init process, all other processes are created by some other process. The init process is created by the kernel itself.

The following are the different types of processes:

- Orphan process: If by some chance the parent process is terminated, then the child process becomes an orphan process. The process which created the parent process, such as the grandparent process, becomes the parent of orphan child process. In the last resort, the

initprocess becomes the parent of the orphan process. - Zombie process: Every process has one data structure called the process control table. This is maintained in the operating system. This table contains the information about all the child processes created by the parent process. If by chance the parent process is sleeping or is suspended due to some reason and the child process is terminated, then the parent process cannot receive the information about the child process termination. In such cases, the child process that has been terminated is called the zombie process. When the parent process awakes, it will receive a signal regarding the child process termination and the process control block data structure will be updated. The child process termination is then completed.

- Daemon process: Until now, we had started every new process in a Bash terminal. Therefore, if we print any text with the

$ echo "Hello"command, it will be printed in the terminal itself. There are certain processes that are not associated with any terminal. Such processes are called a daemon process. These processes are running in background. An advantage of the daemon process is they are immune to the changes happening to Bash shell, which has created it. When we want to run certain background processes, such as DHCP server and so on, then the daemon processes are very useful.