Environmental variables are inherited by any subshells or child processes. For example, HOME, PATH. Every shell terminal has the memory area called environment. Shell keeps all details and settings in the environment. When we start a new terminal or shell, this environment is created every time.

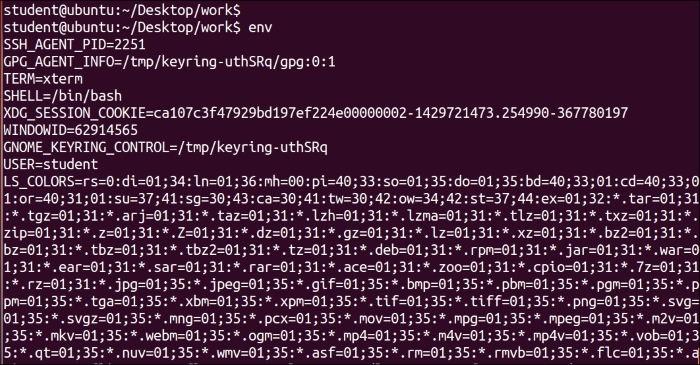

We can view environment variables by the following command:

$ env

Or:

$ printenv

Output:

This is the output of the $ env command. The list of environment variables will be quite extensive. I advise you to browse through the complete list. We can change the content of any of these environment variables.

Environmental variables are defined in a terminal or shell. They will be available in subshells or child shells created from the current shell terminal. You will learn about these activities in the next few sections. You have already learned that every command in shell creates a new subshell from the current shell.

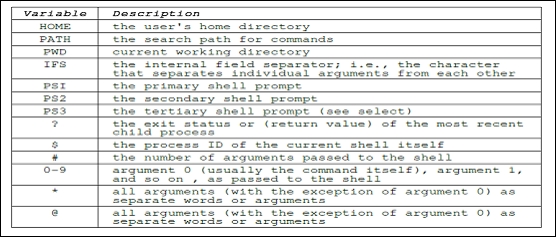

The following is a brief summary of the few environmental variables:

Whenever any user logs in, the /etc/profile Shell script is executed.

For every user, the .bash_profile Shell script is stored in the home folder. The complete path or location is /home/user_name/.profile.

Whenever a new terminal is created, every new terminal will execute the script .bashrc, which is located in the home folder of every user.

In the current shell, we can create and store user defined variables. These may contain characters, digits, and "_". A variable should not start with a digit. Normally for environment variables, upper case characters are used.

If we create a new variable, it will not be available in subshells. The newly created variable will be available only in the current shell. If we run Shell script, then local variables will not be available in the commands called by Shell script. Shell has one special variable $$. This variable contains the process ID of the current shell.

Let's try a few commands:

$ echo $$ 1234

This is the process ID of the current shell.

$ name="Ganesh Naik" $ echo $name Ganesh Naik

We declared the variable name and initialized it.

$ bash

This command will create a new subshell.

$ echo $$ 1678

This is the process ID of the newly created subshell.

$ echo $name

Nothing will be displayed, as the local variables from the parent shell are not inherited in the newly created child shell or subshell:

$ exit

We will exit the subshell and return to the original shell terminal.

$ echo $$ 1234

This is the process ID of the current shell or parent shell.

$ echo $name Ganesh Naik

This is displaying the variable's presence in the original shell or parent shell.

Variables created in the current shell will not be available in a subshell or child shell. If we need to use a variable in a child shell, then we need to export them using the export command.

Using the export command, we are making variables available in the child process or subshell. But if we declare new variables in the child process and export it in the child process, the variable will not be available in parent process. The parent process can export variables to child, but the child process cannot export variables to the parent process.

Whenever we create a Shell script and execute it, a new shell process is created and the Shell script runs in that process. Any exported variable values are available to the new shell or to any subprocess.

We can export any variable as follows:

$ export NAME

Or:

$ declare -x NAME

Let's understand the concept of exporting the variable by the following example:

$ PERSON="Ganesh Naik" $ export PERSON $ echo $PERSON Ganesh Naik $ echo $$ 515

The process ID of the current shell or parent shell is 515.

$ bash

This will start a subshell.

$ echo $$ 555

This is the process ID of new or subshell.

$ echo $PERSON Ganesh Naik $ PERSON="Author" $ echo $PERSON Author $ exit

This will terminate the subshell, and will be placed in the parent shell.

$ echo $$ 515

This is the process ID of the parent shell.

$ echo $PERSON Author

Let's write Shell script to use the concept we learned:

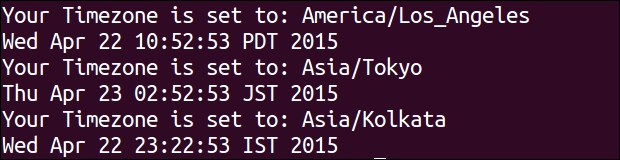

# Ubuntu Timezone files location : /usr/share/zoneinfo/ # redhat "/etc/localtime" instead of "/etc/timezone" # In Redhat # ln -sf /usr/share/zoneinfo/America/Los_Angeles /etc/localtime export TZ=America/Los_Angeles echo "Your Timezone is = $TZ" date export TZ=Asia/Tokyo echo "Your Timezone is = $TZ" date unset TZ echo "Your Timezone is = $(cat /etc/timezone)" # For Redhat or Fedora /etc/localtime date

The date command checks the TZ environmental variable. We initialized the TZ for Los_Angeles, then to Tokyo, and then finally we removed it. We can see the difference in the date command output.

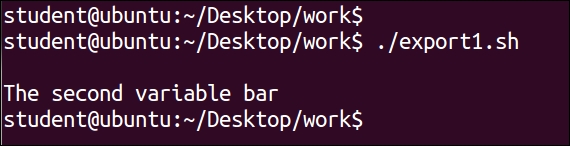

Let's write another Shell script to study the parent and child process and exportation of variables.

Create the export1.sh Shell script:

#!/bin/bash foo="The first variable foo" export bar="The second variable bar" ./export2.sh Create another shell script export2.sh #!/bin/bash echo "$foo" echo "$bar"

The Shell script export1.sh runs as a parent process and export2.sh is started as a child process of export1.sh. We can clearly observe that the variable bar, which was exported, is available in the child process; but variable foo, which was not exported, is not available in the child process.