You will learn the very useful concept of I/O redirection in this section.

All I/O, including files, pipes, and sockets, are handled by the kernel via a mechanism called the file descriptor. A file descriptor is a small unsigned integer, an index into a file-descriptor table maintained by the kernel and used by the kernel to reference open files and I/O streams. Each process inherits its own file-descriptor table from its parent. The first three file descriptors are 0, 1, and 2. File descriptor 0 is standard input (stdin), 1 is standard output (stdout), and 2 is standard error (stderr). When you open a file, the next available descriptor is 3, and it will be assigned to the new file.

When a file descriptor is assigned to something other than a terminal, it is called I/O redirection. The shell performs redirection of output to a file by closing the standard output file descriptor 1 (the terminal) and then assigning that descriptor to the file. When redirecting standard input, the shell closes file descriptor 0 (the terminal) and assigns that descriptor to a file. The Bash shells handle errors by assigning a file to the file descriptor 2.

The following command will take input from the sample.txt file:

$ wc < sample.txt

The preceding command will take content from the sample.text file. The wc command will print the number of lines, words, and characters in the sample.txt file.

$ echo "Hello world" > log.txt

This command will redirect output to be saved in the log.txt file.

$ echo "Welcome to Shell Scripting" >> log.txt

This command will append the Hello World text in the log.txt file.

The single > will overwrite or replace the existing text in log file. And double >> will append the text in the log file.

Let's see a few more examples:

$ tr '[A-Z]' '[a-z]' < sample.txt

The preceding tr command will read text from the sample.txt file. The tr command will convert all uppercase letters to lower case letters and will print converted text on screen:

$ ls > log.txt $ cat log.txt

The output of command will be as follows:

dir_1 sample.txt extra.file

In this example command, ls is sending directory content to file log.txt. Whenever we want to store the result of the command in the file, we can use the preceding example.

$ date >> log.txt $ cat log.txt

Output:

dir_1 dir_2 file_1 file_2 file_3 Sun Sept 17 12:57:22 PDT 2004

In the preceding example, we are redirecting and appending the result of the date command to the log.txt file.

$ gcc hello.c 2> error_file

The gcc is a C language compiler program. If an error is encountered during compilation, then it will be redirected to error_file. The > character is used for a success result and 2> is used for error results redirection. We can use error_file for debugging purposes:

$ find . –name "*.sh" > success_file 2> /dev/null

In the preceding example, we are redirecting output or success results to success_file and errors to /dev/null. /dev/null is used to destroy the data, which we do not want to be shown on screen.

$ find . –name "*.sh" &> log.txt

The preceding command will redirect both output and error to log.txt.

$ find . –name "*.sh" > log.tx 2>&1

The preceding command will redirect result to log.txt and send errors to where the output is going, such as log.txt.

$ echo "File needs an argument" 1>&2

The preceding command will send a standard output to the standard error. This will merge the output with the standard error.

The summary of all I/O redirection commands will be as follows:

|

< sample.txt |

The command will take input from |

|

> sample.txt |

The success result will be stored in |

|

>> sample.txt |

The successive outputs will be appended to |

|

2> sample.txt |

The error results will be stored in |

|

2>> sample.txt |

The successive error output will be appended to |

|

&> sample.txt |

This will store success and errors, such as in |

|

>& sample.txt |

This will store success and errors, such as in |

|

2>&1 |

This will redirect an error to where output is going |

|

1>&2 |

This will redirects output to where error is going |

|

>| |

This overrides no clobber when redirecting the output |

|

<> filename |

This uses the file as both standard input and output if a device file (from |

|

cat xyz > success_file 2> error_file |

This stores success and failure in different files |

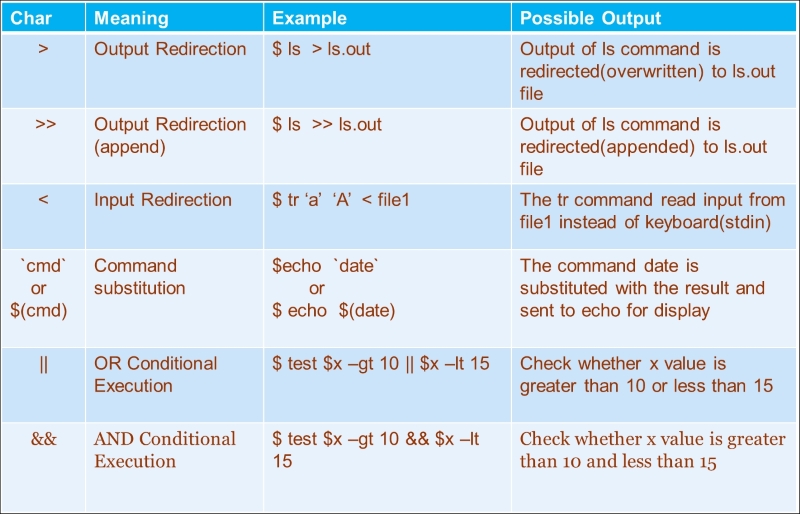

The following is the summary of various metacharacters:

$ touch filea fileb filec fileab filebc filead filebd filead $ touch file{1,2,3}

Try the following command out:

$ ls s* $ ls file $ ls file[abc] $ ls file[abc][cd] $ ls file[^bc] $ touch file file1 file2 file3 … file20 $ ls ????? file1 file2 file3 $ ls file* file file1 file10 file2 file3 $ ls file[0-9] file1 file2 file3 $ ls file[0-9]* file1 file10 file2 file3 $ ls file[!1-2] file3

Curly braces allow you to specify a set of characters from which the shell automatically forms all possible combinations. To make this work, the characters to be combined with the given string must be specified as a comma separated list with no spaces:

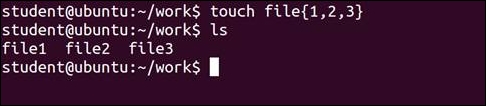

$ touch file{1,2,3} $ ls

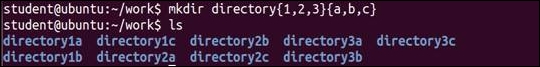

$ mkdir directory{1,2,3}{a,b,c} $ ls

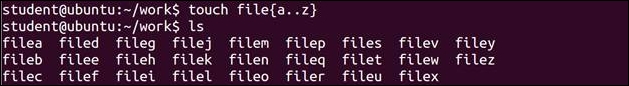

$ touch file{a..z} $ ls

The following is the summary of various io-redirection and logical operators:

For example:

$ ls || echo "Command un-successful" $ ls a abcd || echo "Command un-successful"

These commands will print Command un-successful if the ls command is unsuccessful.