Copyright © 2015 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing, and its dealers and distributors will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

First published: December 2015

Production reference: 1211215

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78528-621-6

Author

Ganesh Sanjiv Naik

Reviewers

Advait Deo

Eax Melanhovich

Shawn Solomon

Commissioning Editor

Nadeem Bagban

Acquisition Editor

Tushar Gupta

Content Development Editor

Nikhil Potdukhe

Technical Editor

Rupali R. Shrawane

Copy Editor

Charlotte Carneiro

Project Coordinator

Izzat Contractor

Proofreader

Safis Editing

Indexer

Rekha Nair

Production Coordinator

Manu Joseph

Cover Work

Manu Joseph

Ganesh Sanjiv Naik is an author, consultant, and corporate trainer for embedded Android, embedded Linux, and Internet of Things related product development.

He completed his computer engineering in 1988. Since then, he has worked in this industry. He has worked on projects including micro-controller based projects to advanced Embedded Android projects. He has more than 20 years of professional experience and project accomplishment in information technology.

Ganesh has a passion and deep desire for teaching. He has trained 1,000 engineers in Linux and Android product development. He has developed a lot of training material as well as curriculum for various universities and training institutes.

He has an interest in spiritual study and practices such as meditation. He is a certified yoga teacher. His hobbies include yoga and martial arts.

He has worked as a corporate trainer for Indian Space Research Organization, Intel, GE, Samsung, Motorola, Penang Skill Development Center (Malaysia), various companies in Singapore as well as various other corporates in India and other countries. He has started a company called Levana Technologies, which works with the Penang Skill Development Center (Malaysia) for consulting and training activities. If you would like to send feedback, suggestions, or corrections in the book, he can be contacted at https://in.linkedin.com/in/naikganesh.

This book is his real-life experience….

He has worked as a consultant and corporate trainer in the following skills:

I would like to thank my wife, Vishalakshi, for putting up with my late night writing sessions. Even though Vishalakshi is from microbiology background, on my request, she proofed all the chapters to spot language shortcomings. She patiently read my complete book, and even after not being a programmer, she gave me many valuable suggestions. Without her support and continuous motivation, this book would not have been possible. My professional friend, Kuldeep Vaity, has also read all chapters from a developer's perspective. His feedback was very valuable from technical angles, such as unclear code, insufficient explanation, and similar.

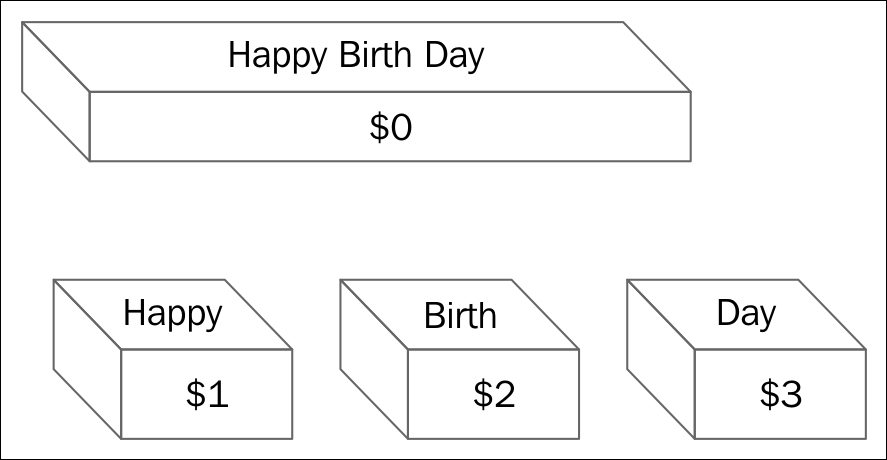

I feel proud to say that the book's cover picture was designed by my daughter, Roopali. She conceptualized the theme and took a lot of effort to properly convey the meaning of the book to readers.

My special thanks to the technical reviewers of the book. Their valuable suggestions have helped me add value to this book.

I would like to thank the entire Packt Publishing team. I would especially like to thank, Aditya Nair and Nikhil Potdukhe of Packt Publishing for the positive, motivating support given to me during the initial period to the end of the completion of this book. Nikhil was very helpful and patient in following up with me for chapters. Due to my busy schedule of consulting and training activities, I was not able to complete my chapters as per schedule; but Nikhil used to follow up very nicely, understandingly, and patiently for the chapter's completion. Without his patient follow up, either I would have completed this book very late, or I would have left the writing work incomplete.

Advait Deo has more than 10 years of experience in database domain, has spent time on many aspects of databases until now, starting from Oracle version 8 until 12c. He mainly focuses on database performance tuning, integrating database with front end application, scripting, and automation. He is currently working as a senior database administrator for (world leader in retail business).

Prior to this book, Advait has reviewed Oracle Database 11g R2 Performance Tuning Cookbook, Packt Publishing (ISBN 1849682607). He also publishes some of his work and learnings on his website at http://avdeo.com.

Eax Melanhovich is 27 and lives in Moscow, Russia. Most people don't know his real name or where he works since Eax is concerned about his privacy. Eax is an author of probably the most popular Russian standalone technical blog eax.me. He is also one of the co-hosts of the popular Russian IT podcast devzen.ru. Eax is an Ubuntu user and a functional programming enthusiast.

Shawn Solomon is a technology veteran with a broad background of experience from more than 20 years of pioneering in various technologies. While working in the ISP, VoIP, educational, open source development, and disaster recovery fields, his skillset has adapted and broadened over the years.

For support files and downloads related to your book, please visit www.PacktPub.com.

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at <service@packtpub.com> for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

https://www2.packtpub.com/books/subscription/packtlib

Do you need instant solutions to your IT questions? PacktLib is Packt's online digital book library. Here, you can search, access, and read Packt's entire library of books.

If you have an account with Packt at www.PacktPub.com, you can use this to access PacktLib today and view 9 entirely free books. Simply use your login credentials for immediate access.

I wish to dedicate this book to my Gurudev His Holiness Dr. Jayant Balaji Athavale. I wish to express gratitude for his guidance, which I have received for, how to become good human being, good professional and a seeker on the path of spiritual progress.

- Ganesh Sanjiv Naik

Shell scripts are an essential part of any modern operating system, such as UNIX, Linux, Windows, and similar. The scripting language or its syntax may vary from OS to OS; but the fundamental principles remain the same. I first encountered Linux Shell scripts during the development of embedded Linux product development. Shell scripts were initializing the complete product from the basic booting procedure until users logged in and a complete operating system was initialized. Another situation was in the automation of regular activities, such as the build and release management of source codes of very complex products, where more than 10,000 files were a part of a single project. Similarly, another very common requirement comes while using the make utility, which is used to compile and build complex product source codes.

Initially, I had learned scripts to solve practical problems and customize already existing products. This book is the summary of what I have learned over the years in Linux Shell scripting during project development work, consultancy, and corporate trainings and their Q&A sessions.

In this book, you will learn about the very basics of Shell scripting to complex, customized automation. By the end of this book, you will be able to confidently use your own Shell scripts for the real-world problems out there. The idea is to be as practical as possible and give you the look and feel of what real-world scripting looks like.

This book covers bash, the GNU Bourne-Again Shell scripting. You can use the knowledge gained by reading this book for any shell of any of the UNIX flavors or distributions. You will need to take care of a few syntax changes if you are working in other shells, such as Korn, and similar. You should be able to read this book cover to cover, or you can just pick it up and read anything that you might find interesting. But perhaps most importantly, if you have a question about how to solve a particular problem or you need a hint, you will find it easy to find the right solution or something close enough to save your time and energy.

Chapter 1, Getting Started and Working with Shell Scripting, you will learn different ways to write and run Shell scripts. You will also learn ways to handle files and directories, and you will learn about working with permissions.

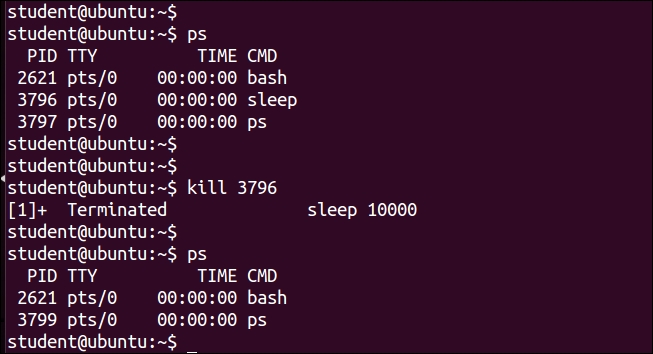

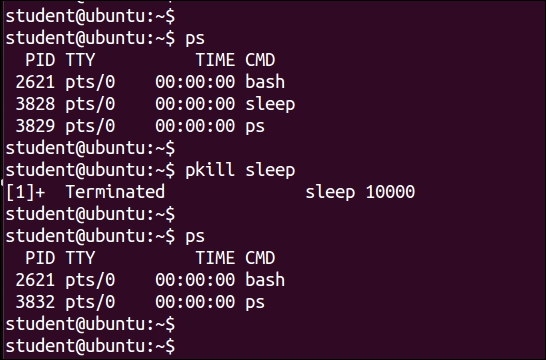

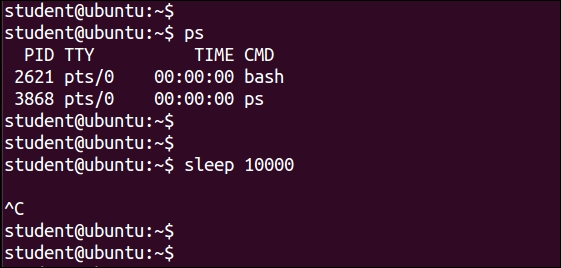

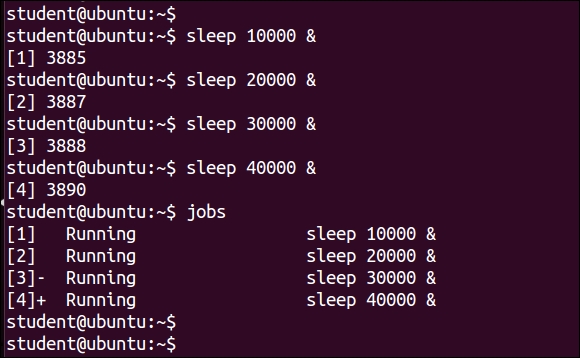

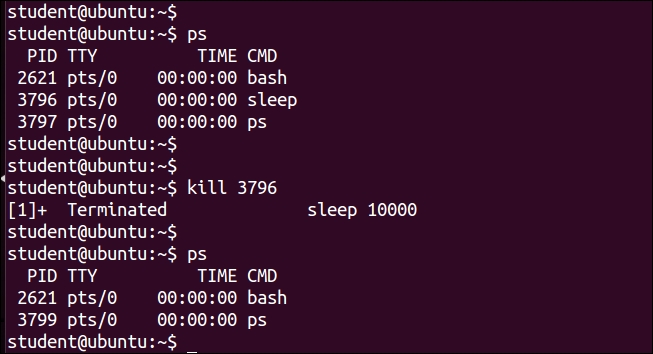

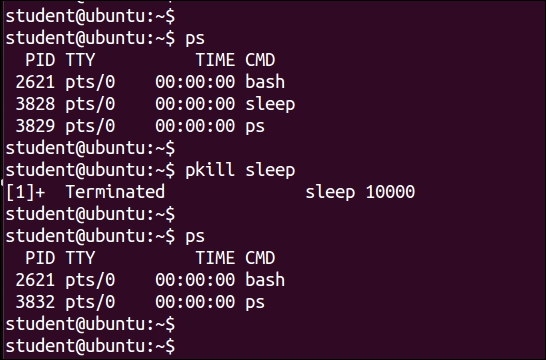

Chapter 2, Drilling Deep into Process Management, Job Control, and Automation, you will learn about basic process management. You will learn about command ps and job management using commands such as jobs, fg, bg, kill, and pkill. Later on, you will learn about process monitoring tools: top, iostat, vmstat and sar.

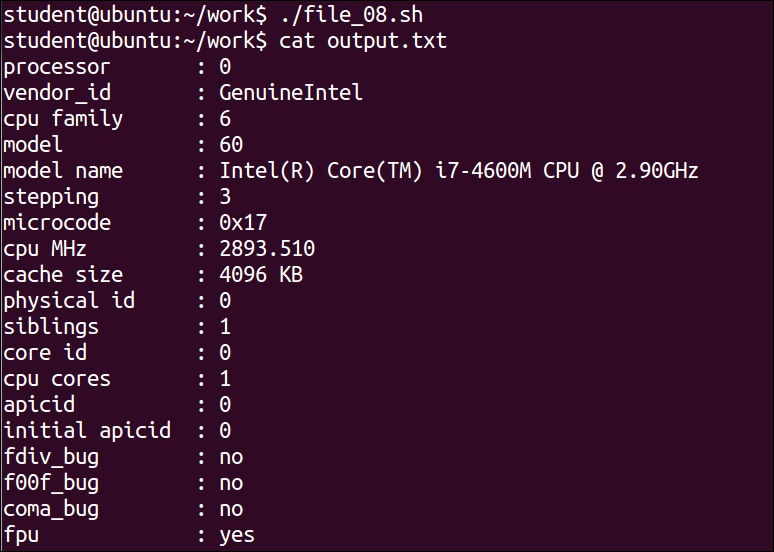

Chapter 3, Using Text Processing and Filters in Your Scripts, you will learn about using more, less, head, and tail commands. You will also learn text processing tools such as, cut, paste, comm, and uniq. You will learn about standard input, output, and error. Later on, you will learn about metacharacters and pattern matching using vi and grep.

Chapter 4, Working with Commands, you will learn about how shell interprets any command entered on the command line. You will also learn command substitution, separators, and pipes in detail.

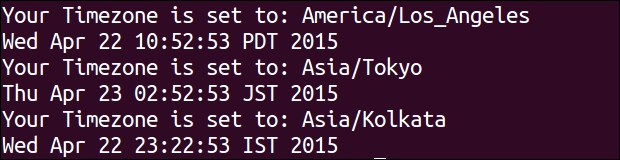

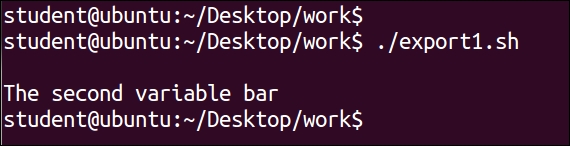

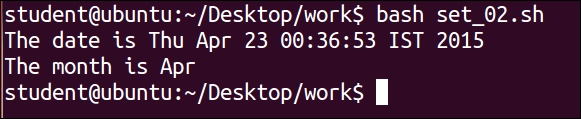

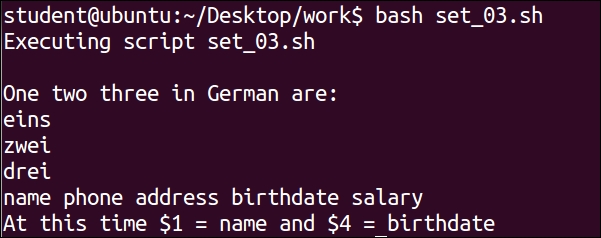

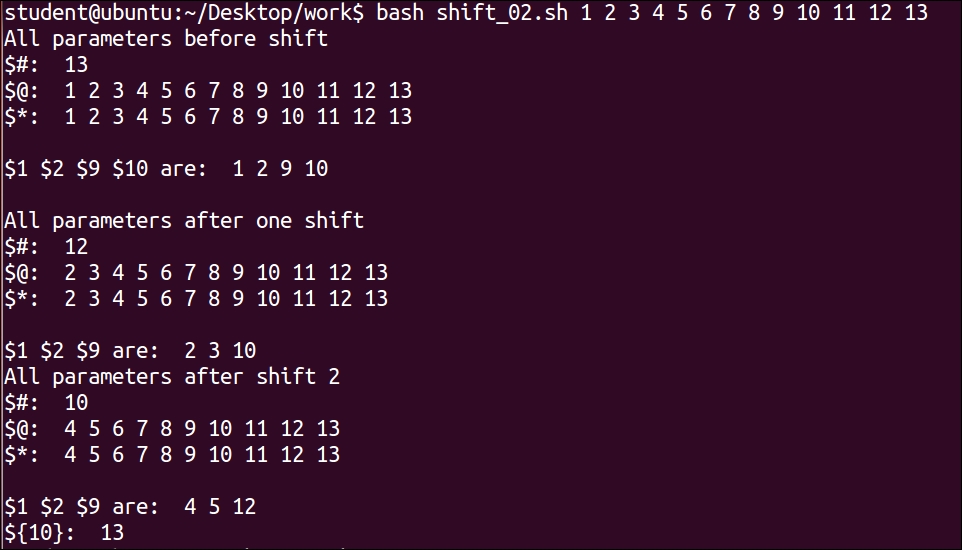

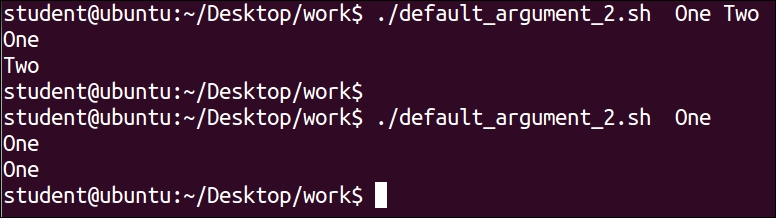

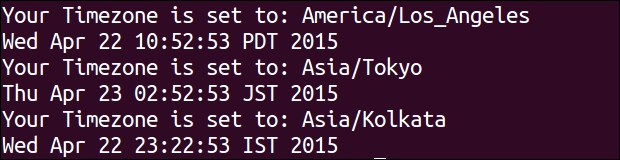

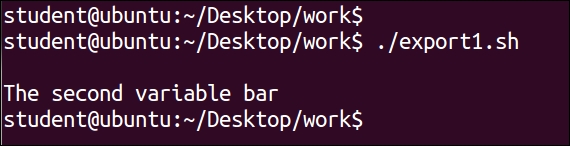

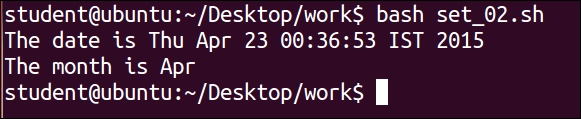

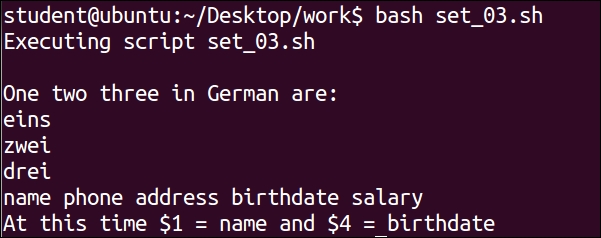

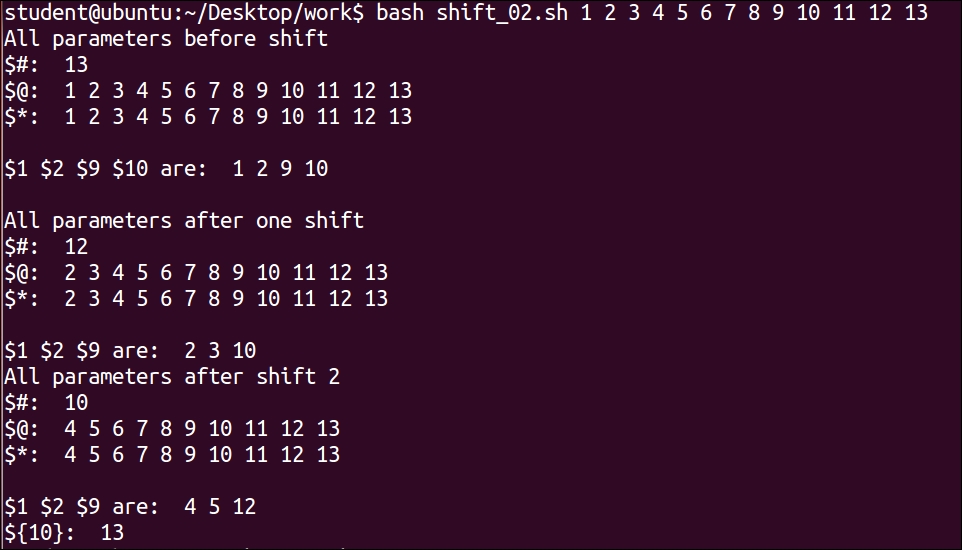

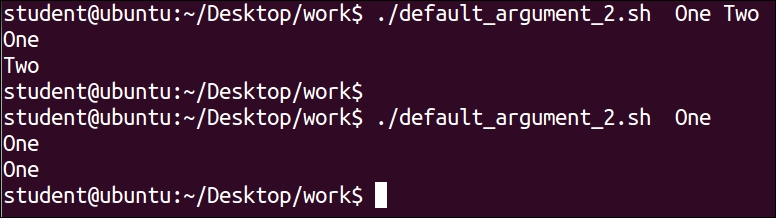

Chapter 5, Exploring Expressions and Variables, you will learn about variables—environment variables. This will include how to export environment variables, set, shift, read-only variables, command-line arguments, and about creating and handling arrays.

Chapter 6, Neat Tricks with Shell Scripting, you will learn about debugging, the here operator, interactive Shell scripts for taking input from the keyboard, and file handling.

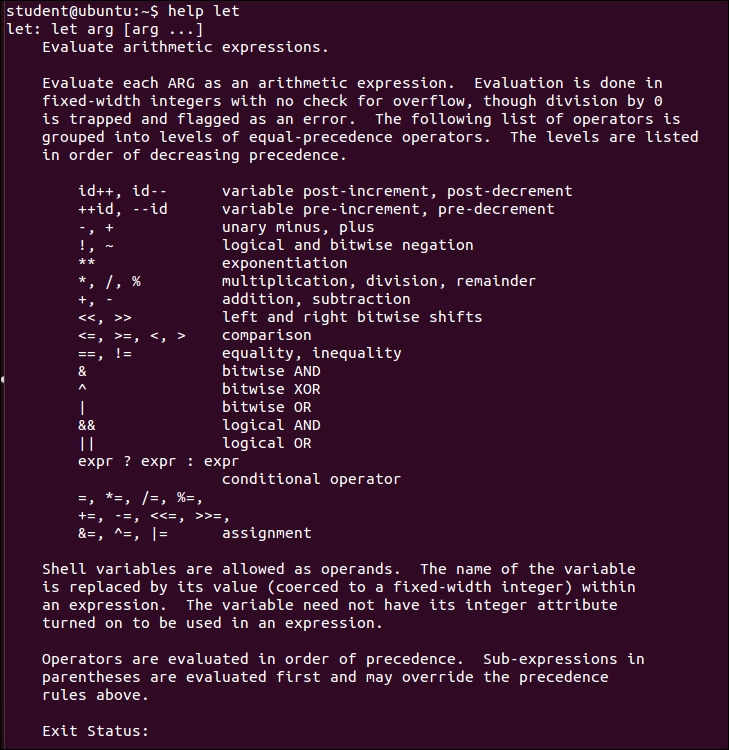

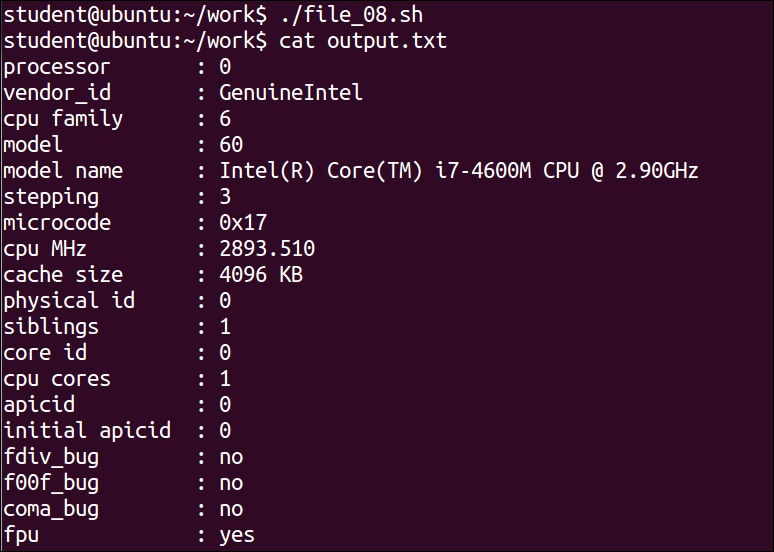

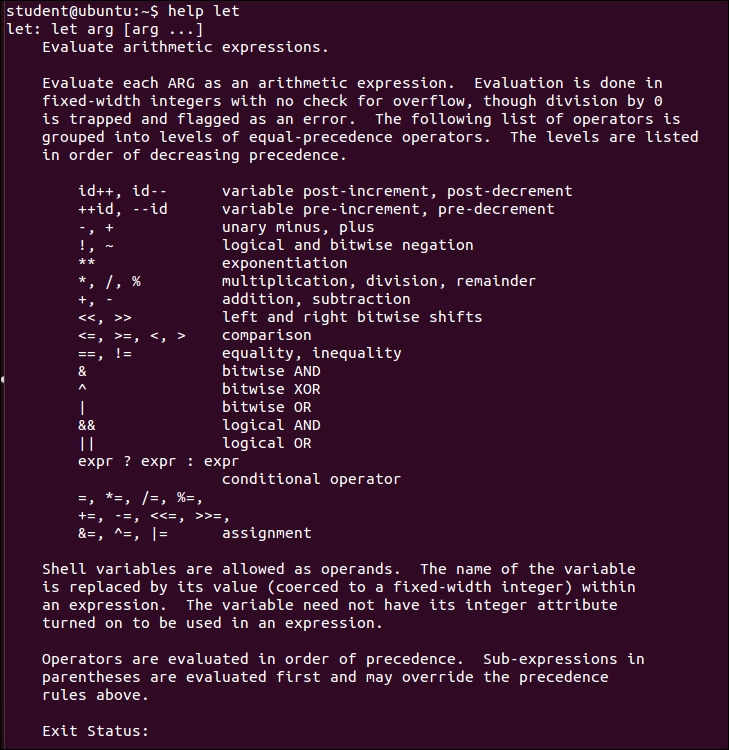

Chapter 7, Performing Arithmetic in Shell Scripts, you will learn about doing arithmetic operations in various ways, such as using declare, let, expr, and arithmetic expressions. You will also learn about representing numbers in different bases, such as hex, octal, and binary. You will learn about using the bc utility for doing floating point or fractional arithmetic.

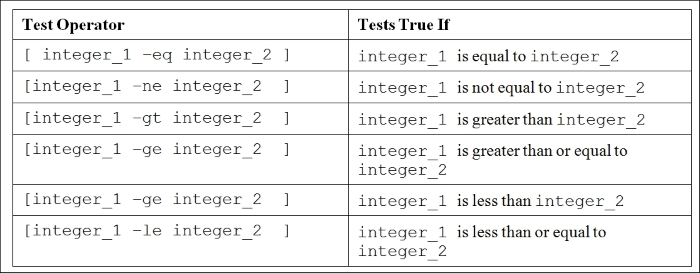

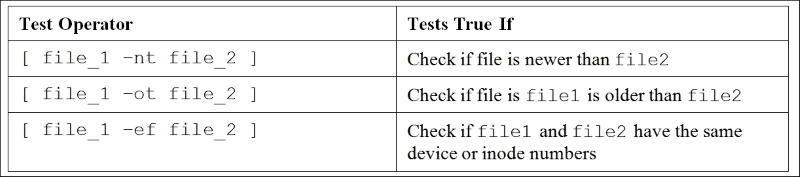

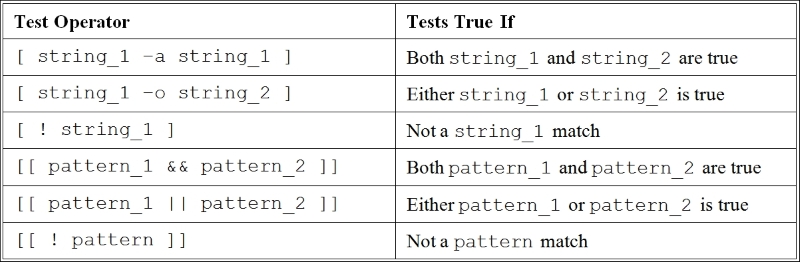

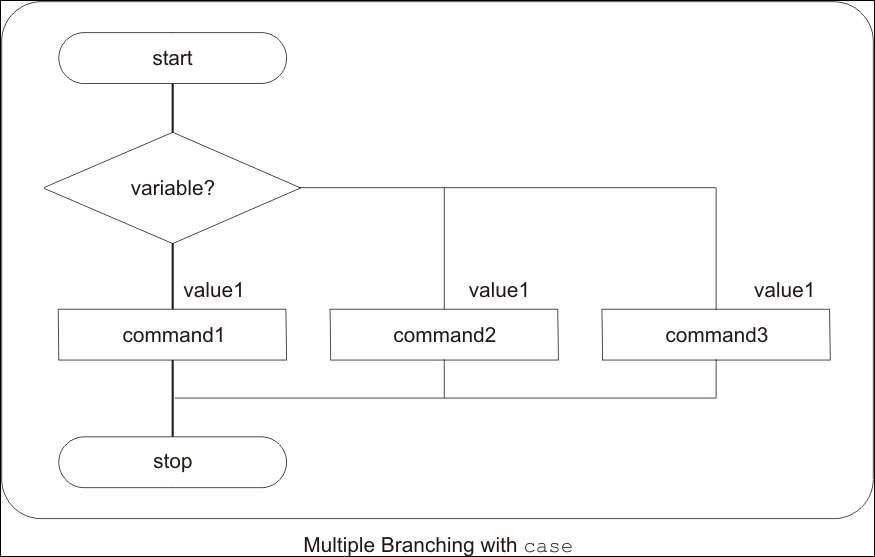

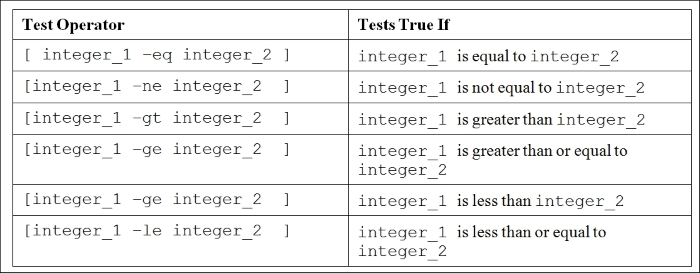

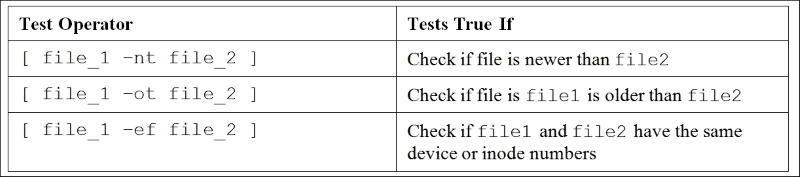

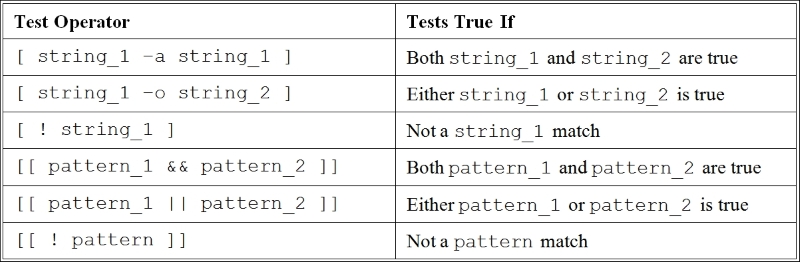

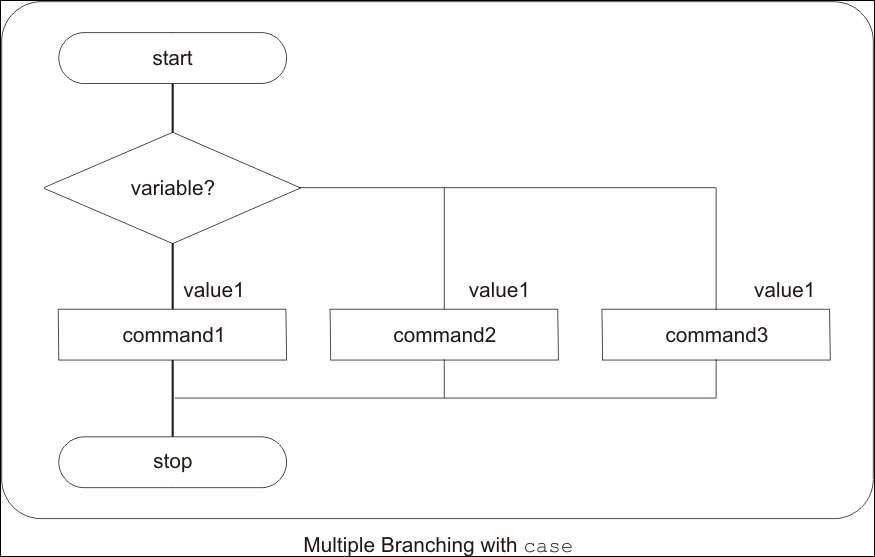

Chapter 8, Automating Decision Making in Scripts, you will learn about using decision making in scripts working with test, if…else, and switching case. You will also use select for loop with menu. For repeating tasks such as processing lists, you will learn about using for loop, while loop and do while. You will also learn about how to control loops using break and continue statements.

Chapter 9, Working with Functions, we will understand about functions in Shell scripts. You will learn about the definition and display of functions by removing the function from the shell. You will also learn about passing arguments to functions, sharing data between functions, declaring local variables in functions, returning results from functions, and running functions in background. You will finally learn about using source and . commands. We will use these commands to use the library of functions.

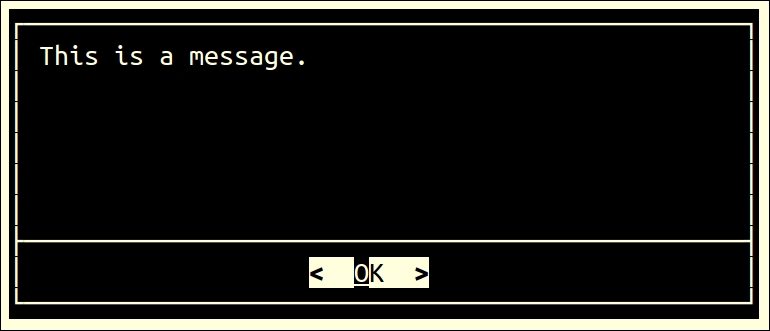

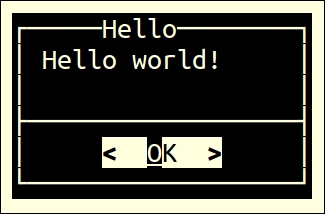

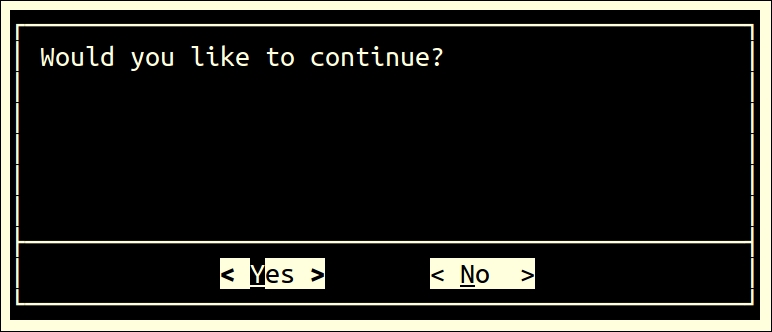

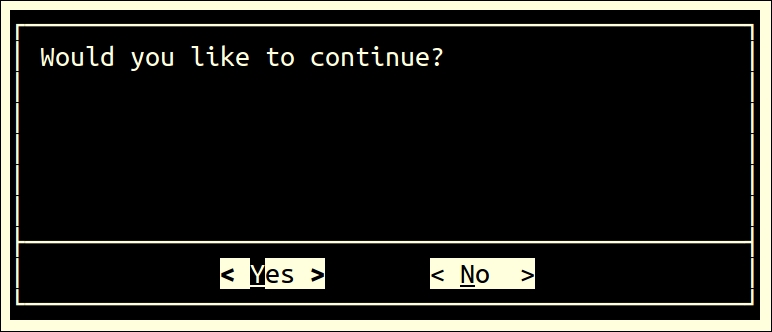

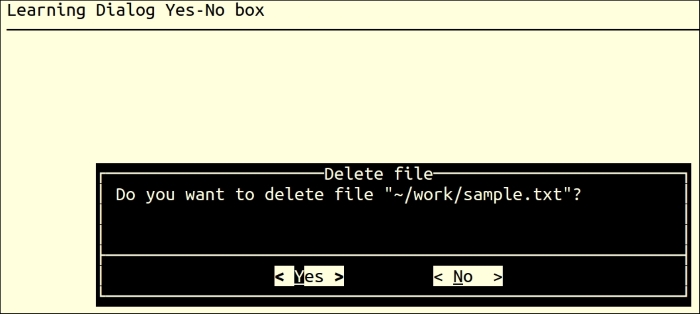

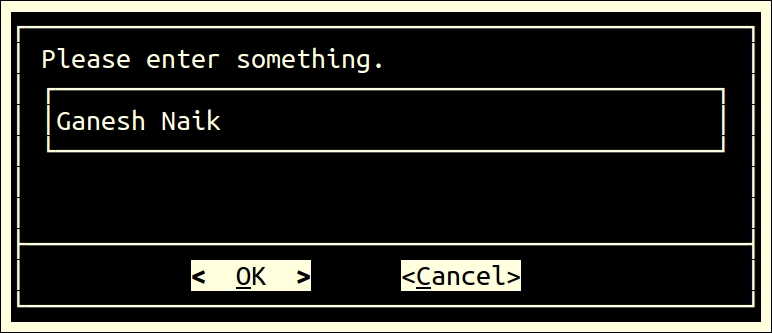

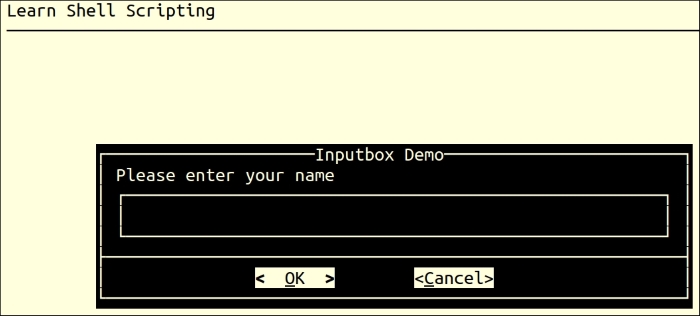

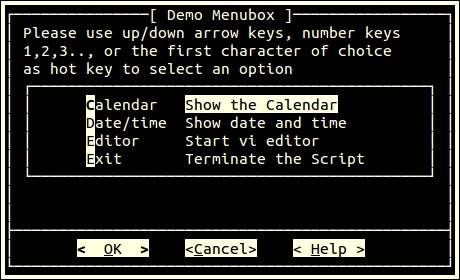

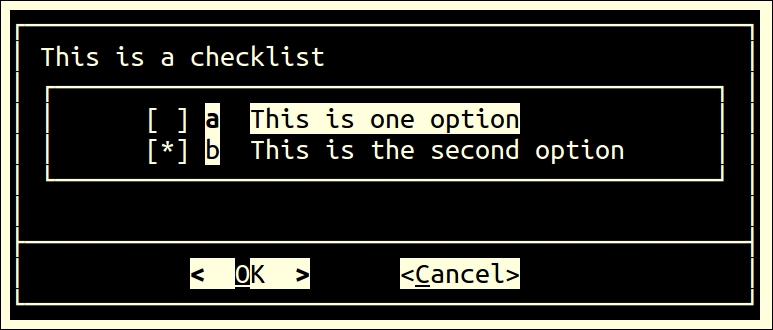

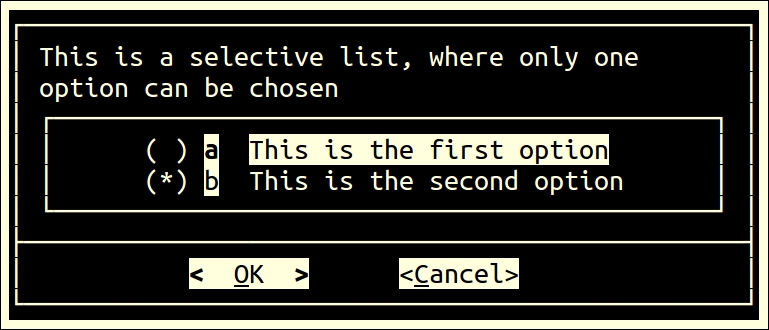

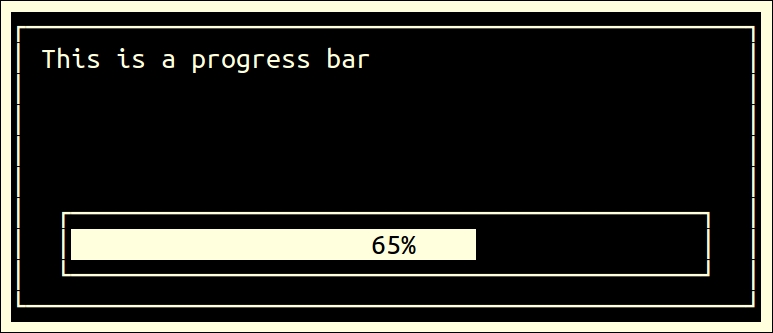

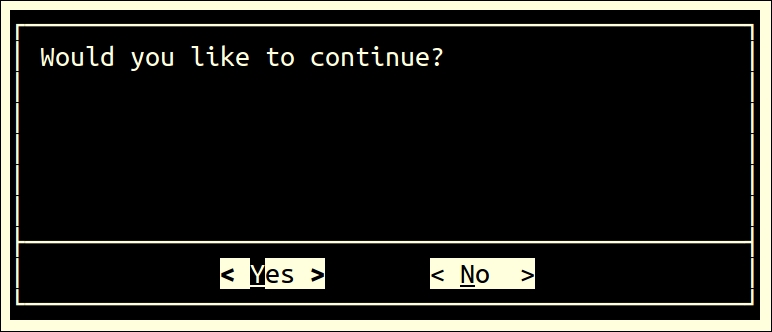

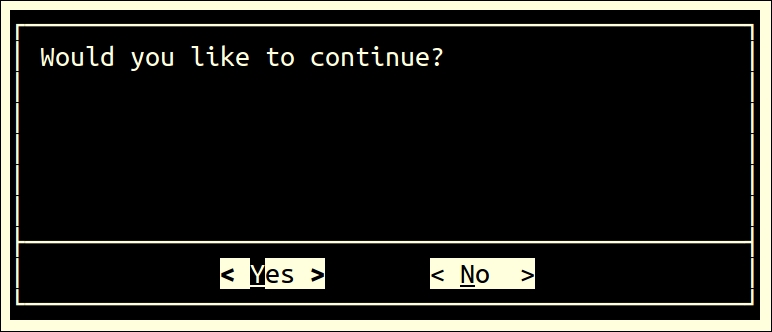

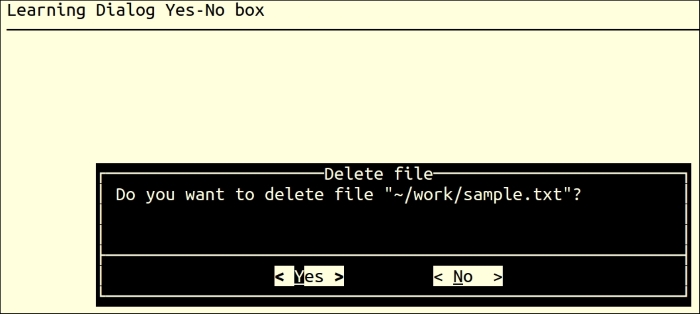

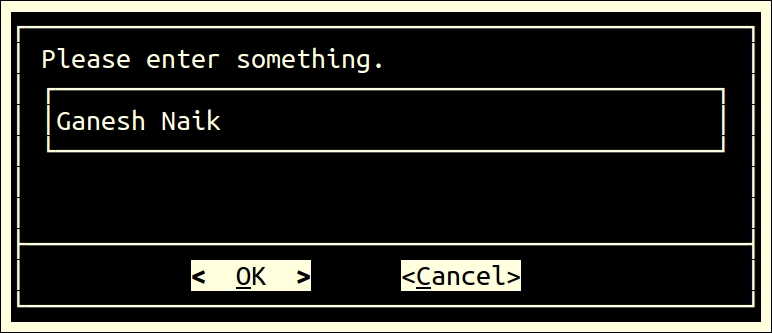

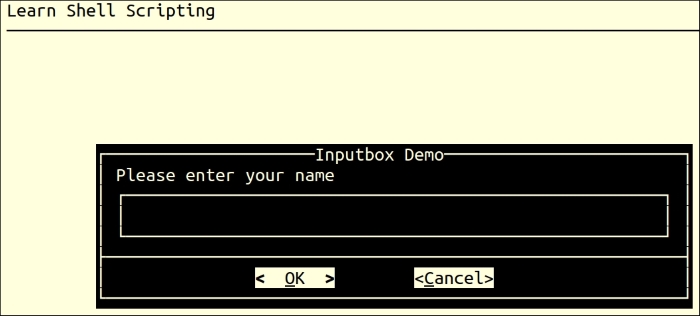

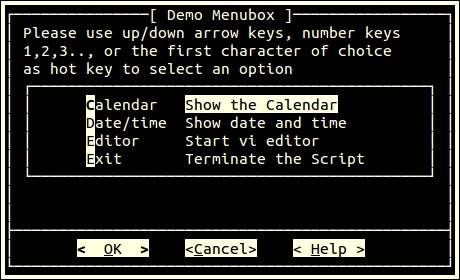

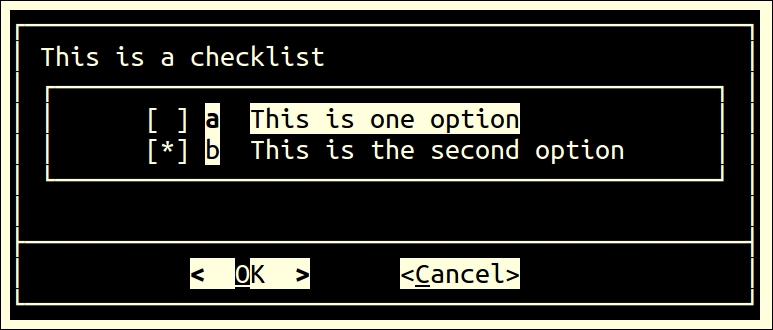

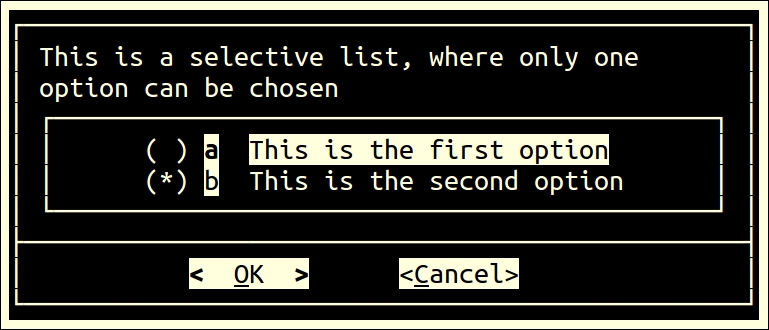

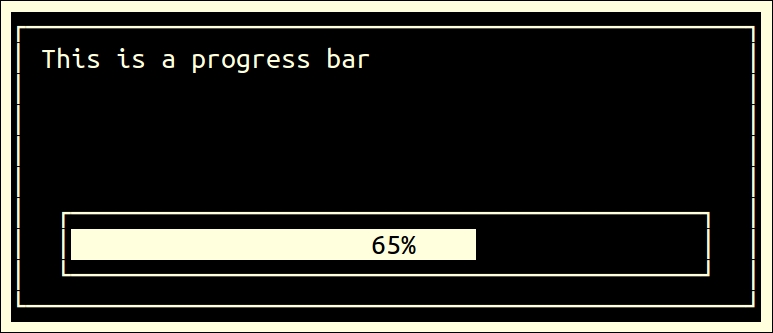

Chapter 10, Using Advanced Functionality in Scripts, you will learn about using traps and signals. You will also learn about creating menus with the help of the dialog utility.

Chapter 11, System Startup and Customizing a Linux System, you will learn about Linux system startup from power on until the user login and how to customize a Linux system environment.

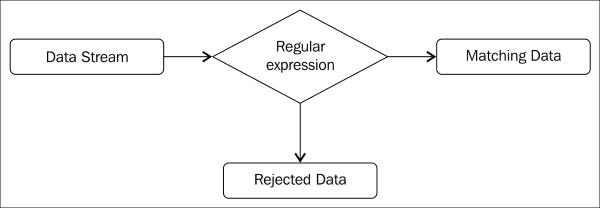

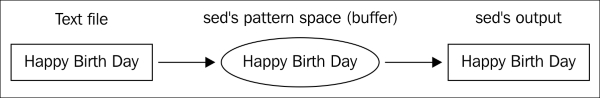

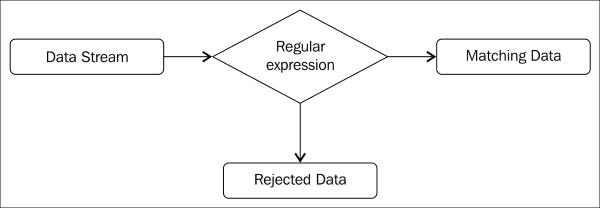

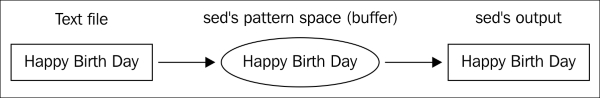

Chapter 12, Pattern Matching and Regular Expressions with sed and awk, you will learn about regular expressions and using sed (stream editor) and awk for text processing. You will learn about the usage of various commands and options along with a lot of examples for using sed and awk.

Any computer that has Linux OS installed on it will be sufficient for learning all the topics discussed in this book. I have personally tested all the commands and scripts in Ubuntu 12.10 distribution.

While learning, if you find that any utility has not installed alongside Ubuntu or any Debian-based distribution, then enter the following command to install this utility:

$ sudo apt-get update $ sudo apt-get install package-name

The Internet should be available for the previous commands to run.

In Red Hat or any other rpm-based distribution, enter the following commands:

$ sudo yum update $ sudo yum install package-name

If the Internet is connected, then using these commands, you can install any command or utility that is not already installed.

This book is for the readers that are proficient at working with Linux, and who want to learn about Shell scripting to improve their efficiency and practical skills. The following are a few examples where we can use skills learned in this book:

In this book, you will find a number of text styles that distinguish between different kinds of information. Here are some examples of these styles and an explanation of their meaning.

Code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles are shown as follows: "In the output, 4d3 tells us that line number 4 is deleted in file2. Similarly, the change command will show us changes in the file as well."

A block of code is set as follows:

#!/bin/bash # This is comment line echo "Hello World" ls date

When we wish to draw your attention to a particular part of a code block, the relevant lines or items are set in bold:

$ expr 4 * 10

expr: syntax error

With command expr, we cannot use * for multiplication. We need to use \* for multiplication.

$ expr "4 * 10"

4 * 10

$ expr 4 \* 10

40Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

$ sed '1,3d' datafile > tempfile $ awk -F: '/Marie/{print $1, $2}' people1.txt

New terms and important words are shown in bold.

Feedback from our readers is always welcome. Let us know what you think about this book—what you liked or disliked. Reader feedback is important for us as it helps us develop titles that you will really get the most out of.

To send us general feedback, simply e-mail <feedback@packtpub.com>, and mention the book's title in the subject of your message.

If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, see our author guide at www.packtpub.com/authors.

Now that you are the proud owner of a Packt book, we have a number of things to help you to get the most from your purchase.

We also provide you with a PDF file that has color images of the screenshots/diagrams used in this book. The color images will help you better understand the changes in the output. You can download this file from https://www.packtpub.com/sites/default/files/downloads/LearningLinuxShellScripting_ColorImages.pdf.

Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you find a mistake in one of our books—maybe a mistake in the text or the code—we would be grateful if you could report this to us. By doing so, you can save other readers from frustration and help us improve subsequent versions of this book. If you find any errata, please report them by visiting http://www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details of your errata. Once your errata are verified, your submission will be accepted and the errata will be uploaded to our website or added to any list of existing errata under the Errata section of that title.

To view the previously submitted errata, go to https://www.packtpub.com/books/content/support and enter the name of the book in the search field. The required information will appear under the Errata section.

Piracy of copyrighted material on the Internet is an ongoing problem across all media. At Packt, we take the protection of our copyright and licenses very seriously. If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, please provide us with the location address or website name immediately so that we can pursue a remedy.

Please contact us at <copyright@packtpub.com> with a link to the suspected pirated material.

We appreciate your help in protecting our authors and our ability to bring you valuable content.

If you have a problem with any aspect of this book, you can contact us at <questions@packtpub.com>, and we will do our best to address the problem.

Whoever works with Linux will come across shell as the first program to work with. The Graphical user interface (GUI) usage has become very popular due to the ease of use. Those who want to take advantage of the power of Linux will use the shell program by default.

Shell is a program which provides the user direct interaction with the operating system. Let's understand the stages in the evolution of the Linux operating system. Linux was developed as a free and open source substitute for UNIX OS. The chronology can be as follows:

In this chapter, we will cover the following topics:

Initially, the UNIX OS used a shell program called Bourne Shell. Then eventually, many more shell programs were developed for different flavors of UNIX. The following is brief information about different shells:

A brief comparison of various shells is presented in the following table:

|

Feature |

Bourne |

C |

TC |

Korn |

Bash |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aliases |

no |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

|

Command-line editing |

no |

no |

yes |

yes |

yes |

|

Advanced pattern matching |

no |

no |

no |

yes |

yes |

|

Filename completion |

no |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

|

Directory stacks (pushd and popd) |

no |

yes |

yes |

no |

yes |

|

History |

no |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

|

Functions |

yes |

no |

no |

yes |

yes |

|

Key binding |

no |

no |

yes |

no |

yes |

|

Job control |

no |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

|

Spelling correction |

no |

no |

yes |

no |

yes |

|

Prompt formatting |

no |

no |

yes |

no |

yes |

What we see here is that, generally, the syntax of all these shells is 95% similar. In this book, we are going to follow Bash shell programming.

Whenever we type any text in the shell terminal, it is the responsibility of shell to execute the command properly. The activities done by shell are as follows:

We will discuss the preceding topics in the subsequent chapters.

Let's get started by opening the terminal, and we will familiarize ourselves with the Bash Shell environment:

$ echo $SHELL /bin/bash

/bin/bash such as BASH shell:$ bash --version GNU bash, version 2.05.0(1)-release (i386-redhat-linux-gnu) Copyright 2000 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

Hereafter, we will use the word Shell to signify the BASH shell only. If we intend any other shell, then it will be specifically mentioned by name such as KORN and similar other shells.

In Linux, filenames in lowercase and uppercase are different; for example, the files Hello and hello are two distinct files. This is unlike Windows, where case does not matter.

As far as possible, avoid using spaces in filenames or directory names such as:

Hello World.txtHello_World.txt or HelloWorld.txtThis will make certain utilities or commands fail or not work as expected, for example, the make utility.

While typing in filenames or directory names of the existing files or folders, use the tab completion feature of Linux. This will make working with Linux faster.

The following table lists a few basic Linux commands:

Since we learned basic commands to use Linux OS, we will now write our first Shell script called hello.sh. You can use any editor of your choice such as vi, gedit, nano, and other similar editors. I prefer to use the vi editor.

hello.sh file as follows:#!/bin/bash # This is comment line echo "Hello World" ls date

The #!/bin/bash line is called the shebang line. The combination of the characters # and ! is called the magic number. The shell uses this to call the intended shell such as /bin/bash in this case. This should always be the first line in a Shell script.

The next few lines in the Shell script are self explanatory.

#, will be treated as a comment line. An exception to this would be the first line with #!/bin/bashecho command will print Hello World on the screenls command will display directory content on the consoledate command will show the current date and timeWe can execute the newly created file by the following commands:

$ bash hello.sh

$ chmod +x hello.sh

By running any of the preceding commands, we are adding executable permission to our newly created file. You will learn more about file permissions in later in this same chapter.

$ ./hello.sh

By running the preceding command, we are executing hello.sh as the executable file. By technique one, we passed filename as an argument to Bash shell.

The output of executing hello.sh will be as follows:

Hello World hello.sh Sun Jan 18 22:53:06 IST 2015

Since we have successfully executed our first script, we will proceed to develop a more advanced script, hello1.sh. Please create the new script hello.sh as follows:

#!/bin/bash # This is the first Bash shell # Scriptname : Hello1.sh # Written by: Ganesh Naik echo "Hello $LOGNAME, Have a nice day !" echo "Your are working in directory `pwd`." echo "You are working on a machine called `uname -n`." echo "List of files in your directory is." ls # List files in the present working directory echo "Bye for now $LOGNAME. The time is `date +%T`!"

The output of executing hello.sh will be as follows:

Hello student, Have a nice day !. Your are working in directory /home/student/work. You are working on a machine called ubuntu. List of files in your directory is. hello1.sh hello.sh Bye for now student. The time is 22:59:03!

You will learn about the LOGNAME, uname, and other similar commands as we go on with the book.

In any program development, the following are the two options:

When we use a compiler-based language, we compile the complete source code, and as a result of compilation, we get a binary executable file. We then execute the binary to check the performance of our program.

On the contrary, when we develop the Shell script, such as an interpreter-based program, every line of the program is input to Bash shell. The lines of Shell script are executed one by one sequentially. Even if the second line of a script has an error, the first line will be executed by the shell interpreter.

Shell scripts have certain advantages over compiler-based programs, such as C or C++ language. However, Shell scripting has certain limitations as well.

The following are the advantages:

The following are the limitations of Shell scripts:

We will explore the directory structure in Linux so that it will be useful later on:

/bin/: This contains commands used by a regular user./boot/: The files required for the operating system startup are stored here./cdrom/: When CD-ROM is mounted, the CD-ROM files are accessible here./dev/: The device driver files are stored in this folder. These device driver files will point to hardware-related programs running in kernel./etc/: This folder contains configuration files and startup scripts./home/: This folder contains a home folder of all users except the administrator./lib/: The library files are stored in this folder./media/: External media such as a USB pen drive is mounted in this folder./opt/: The optional packages are installed in this folder./proc/: This contains files which give information about kernel and every process running in OS./root/: This is the administrators home folder./sbin/: This contains commands used by the administrator or root user./usr/: This contains secondary programs, libraries, and documentation about user-related programs./var/: This contains variable data such as http, tftp, and similar other./sys/: This dynamically creates the sys filesLet us learn a few commands, which are required very often, such as man, echo, cat and similar:

man command:

$ man man

From the following table, you can get an idea about various types of man pages for the same command:

|

Section number |

Subject area |

|---|---|

|

1 |

User commands |

|

2 |

System calls |

|

3 |

Library calls |

|

4 |

Special files |

|

5 |

File formats |

|

6 |

Games |

|

7 |

Miscellaneous |

|

8 |

System admin |

|

9 |

Kernel routines |

man command to display corresponding manual pages as follows:$ man 1 command $ man 5 command

passwd command, which is used for changing the current password of a user, you can type the command as follows:$ man command man -k passwd // show all pages with keyword man –K passwd // will search all manual pages for pattern $ man passwd

This will show information about the passwd command:

$ man 5 passwd

The preceding command will give information about the file passwd, which is stored in /etc /passwd.

$ whatis passwd

Output:

passwd (1ssl) - compute password hashes passwd (1) - change user password passwd (5) - the password file

$ which passwd /usr/bin/passwd

The preceding line tells us that the binary file of the passwd command is located in the /usr/bin/passwd folder.

$ whereis passwd

The output will be as follows:

passwd: /usr/bin/passwd /etc/passwd /usr/bin/X11/passwd /usr/share/man/man1/passwd.1.gz /usr/share/man/man1/passwd.1ssl.gz /usr/share/man/man5/passwd.5.gz

$ whoami

This command displays the user name of the logged in user:

$ su

The su command (switch user) will make the user as the administrator; but, you should know the administrators, password. The sudo command (superuser do) will run the command with administrator's privileges. It is necessary that the user should have been added in the sudoers list.

# who am i

This command will show the effective user who is working at that moment.

# exit

$ alias ll='ls –l' $ alias copy='cp –rf'

To list all declared aliases, use the following command:

$ alias

To remove an alias, use the following command:

$ unalias copy

$ uname

Output:

Linux

This will display the basic OS information (UNIX name)

$ uname –r

Output:

3.13.0-32-generic

$ uname –a

Output:

Linux ubuntu 3.13.0-32-generic #57~precise1-Ubuntu SMP Tue Jul 15 03:50:54 UTC 2014 i686 i686 i386 GNU/Linux

$ cat /proc/version // detailed info about distribution $ cat /etc/*release # lsb_release -a // will tell distribution info for Ubuntu

The command

cat is used for reading files and displayed on the standard output.

$ ln -s file file_link

$ file fil_name // show type of file

But this is very rarely used, as many powerful editors are already existing, such as vi or gedit.

Hello World on the console. The echo command is very useful for Shell script writers:

$ echo "Hello World"

Hello World to the hello.c file:

$ echo "Hello World" > hello.c

The command echo with > overwrites the content of the file. If content already exists in the file, it will be deleted and new content will be added in the file. In a situation, when we need to append the text to the file, then we can use the echo command as follows:

$ echo "Hello World" >> hello.c will append the text

$ cat hello.c

The following are the types of permissions:

The following are the commands for changing the file permissions:

To check the file permission, give the following command:

$ ll file_name

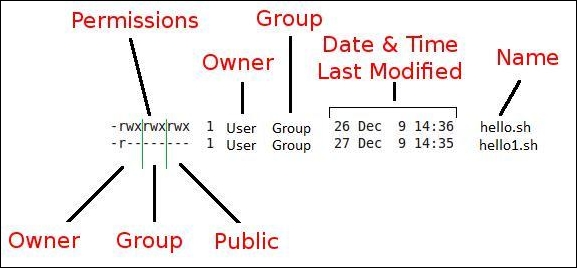

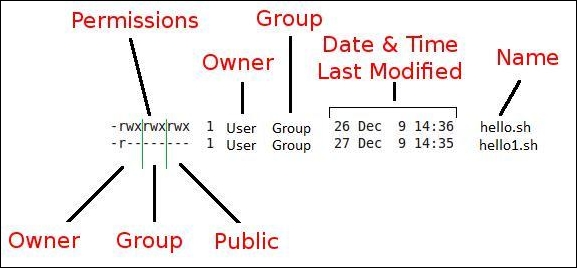

The details of file permissions are as seen in the following image:

In the preceding diagram, as we can see, permissions are grouped in owner-user and group and other users' permissions. Permissions are of three types such as read, write, and execute permissions. As per the requirement, we may need to change permissions of the various files.

We can change the file or directory permissions by the following two ways:

We will see how Linux decides the default permissions of the newly created file or folder:

$ umask 0002

The meaning of the preceding output is that, if we create a new directory, then from the permissions of +rwx, the permission 0002 will be subtracted. This means that for a newly created directory, the permissions will be 775 or rwx rwx r-x. For a newly created file, the file permissions will be rw- rw- r--. By default, for any newly created text file, the execute bit will never be set. Therefore, the newly created text file and directory will have different permissions even though the umask is same.

Another very interesting functionality is the setuid feature. If the setuid bit is set for a script, then the script will always run with the owner's privileges irrespective of which user is running the script. If the administrator wants to run script written by him by other users, then he can set this bit.

Consider either of the following situations:

$ chmod u+s file_name $ chmod 4777 file

The file permissions after any of the preceding two commands will be drwsrwxrwx.

Similar to setuid, the setgid functionality gives the user the ability to run scripts with group owner's privileges, even if it is executed by any other user.

$ chmod g+s filename

Alternatively, you can use the following command:

$ chmod 2777 filename

File permissions after any of the preceding two commands will be drwxrwsrwtx.

Sticky bit is a very interesting functionality. Let's say, in the administration department there are 10 users. If one folder has been set with sticky bit, then all other users can copy files to that folder. All users can read the files, but only the owner of the respective file can edit or delete the file. Other user can only read but not edit or modify the files if the sticky bit is set.

$ chmod +t filename

Alternatively, you can use the following command:

$ chmod 1777

File permissions after any of the preceding two commands will be drwxrwxrwt.

In the last chapter, we introduced ourselves to the Bash shell environment in Linux. You learned basic commands and wrote your first Shell script as well.

You also learned about process management and job control. This information will be very useful for system administrators in automation and solving many problems.

In this chapter, we will cover the following topics:

A running instance of a program is called as process. A program stored in the hard disk or pen drive is not a process. When that stored program starts executing, then we say that process has been created and is running.

Let's very briefly understand the Linux operating system boot-up sequence:

start_kenel().init.

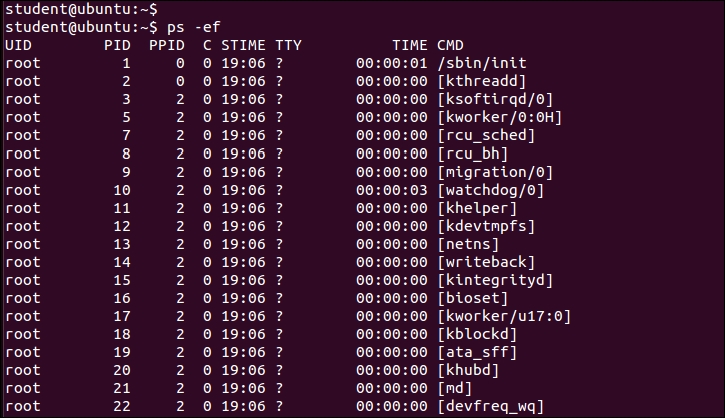

$ ps –ef

init process is 1. This process is the parent process of all user space processes.fork().

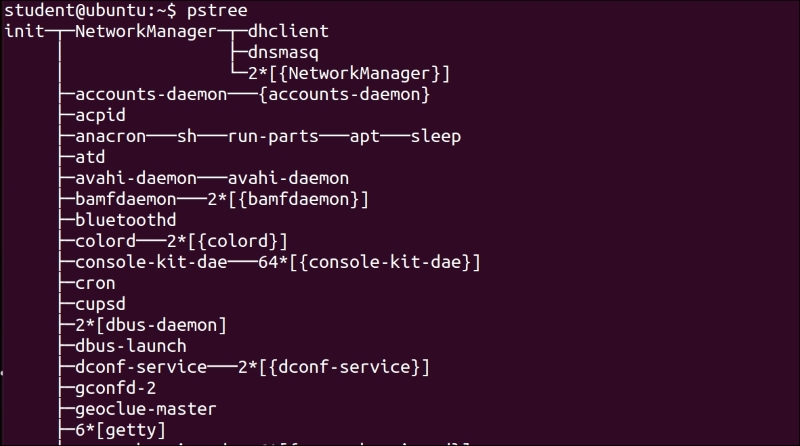

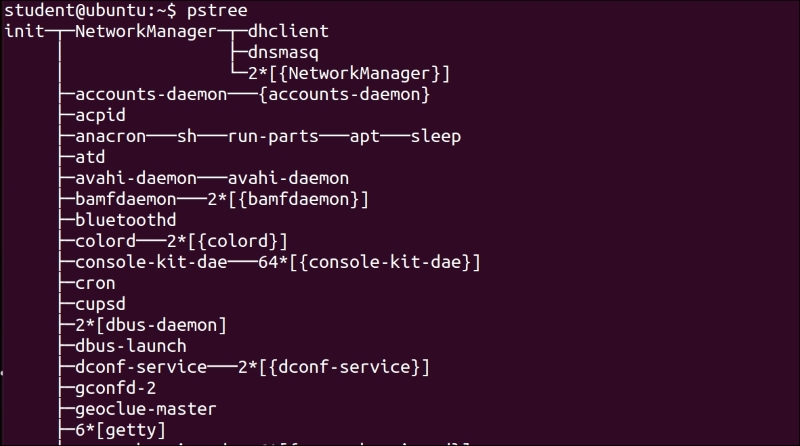

$ pstree

You can see the very first process as init as well as all other processes with a complete parent and child relation between them. If we use the $ps –ef command, then we can see that the init process is owned by root and its parent process ID is 0. This means that there is no parent for init:

Therefore, except the init process, all other processes are created by some other process. The init process is created by the kernel itself.

The following are the different types of processes:

init process becomes the parent of the orphan process.$ echo "Hello" command, it will be printed in the terminal itself. There are certain processes that are not associated with any terminal. Such processes are called a daemon process. These processes are running in background. An advantage of the daemon process is they are immune to the changes happening to Bash shell, which has created it. When we want to run certain background processes, such as DHCP server and so on, then the daemon processes are very useful.We have used the command ps in the introduction. Let's learn more about it:

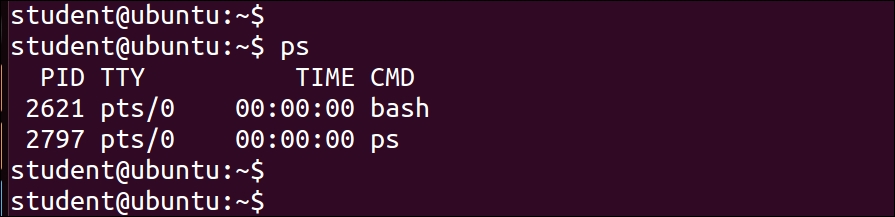

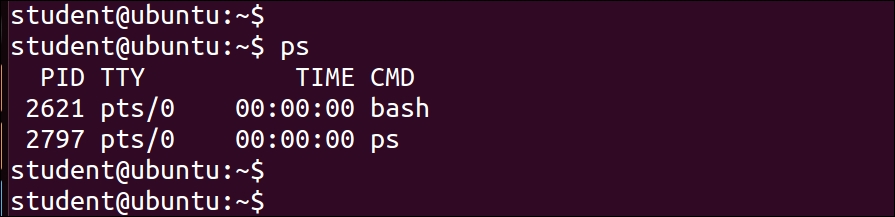

$ ps

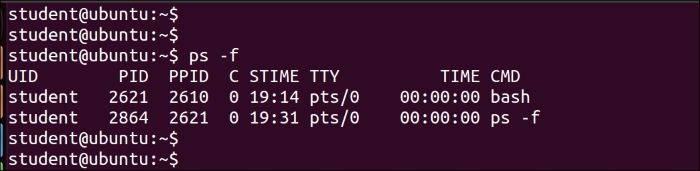

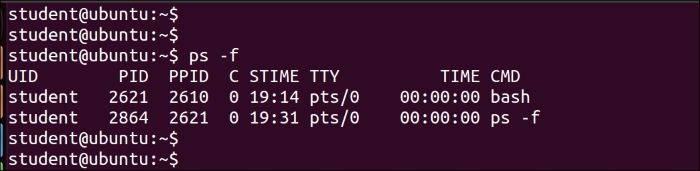

$ ps –f

We can see the process ID in the PID column and the parent process ID in the PPID column in the preceding output.

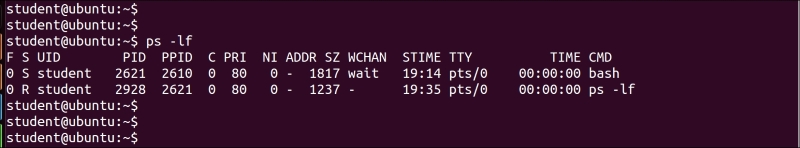

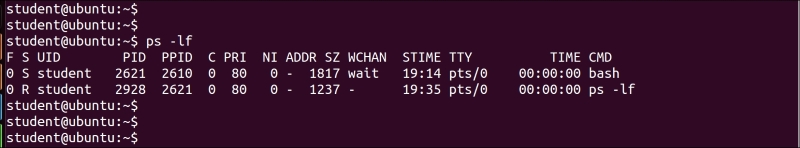

$ ps –lf

In the preceding output, the column with S (state) shows the current state of a process, such as R for running and S for suspended state.

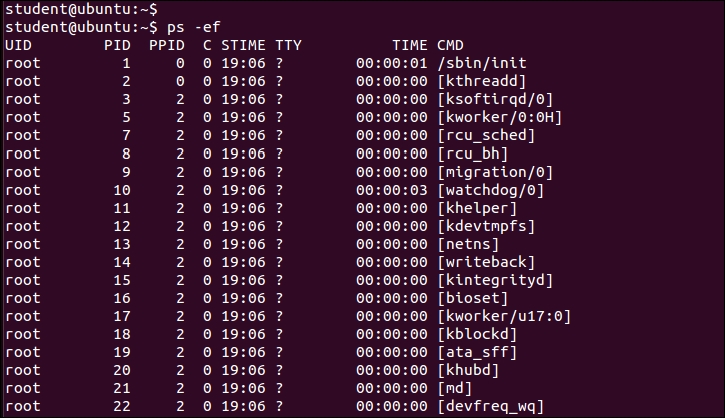

$ ps –ef

The process names in [] are kernel threads. If you are interested in more options to learn about the ps command, you can use the following command:

$ man ps.

To find a particular process, you can use the following command:

$ ps –ef | grep "process_name"

The command with grep will display the process with process_name.

$ kill pid_of_process_to_be_killed

$ kill command, you may need to pass additional option to ensure that the required process is killed, which is shown as follows:

$ kill -9 pid_of_process_to_be_killed

$ pkill command_name $ pkill sleep

Or:

$ pkill -9 command_name

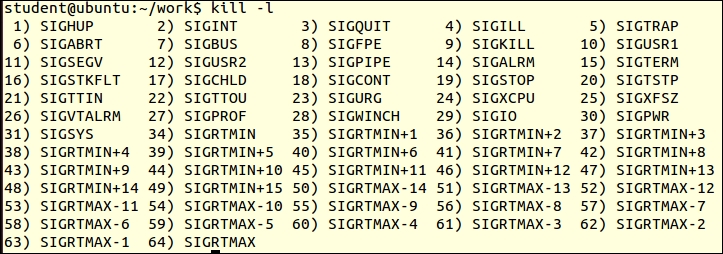

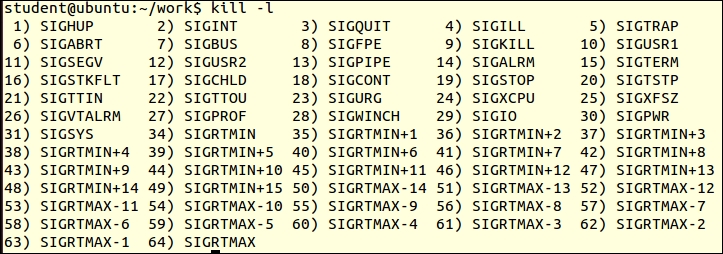

kill, enter following command:

$ kill –l

This displays all the signals or software interrupts used by the operating system. When we enter the $ kill command, the operating system sends the SIGTERM signal to the process. If the process is not killed by this command, then we enter the following command:

$ kill -9 process_name

This sends SIGKILL to the process to be killed.

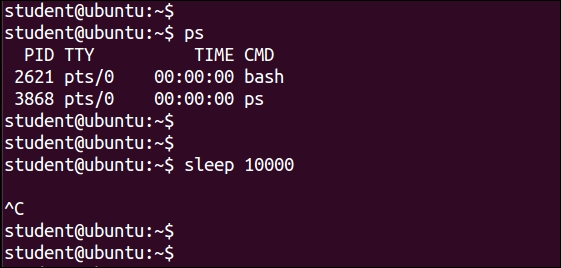

Since we have understood the command to check processes, we will learn more about managing different processes as follows:

&.Hello as the background process, then the command would be as follows:

$ Hello &

&, then it starts running as the background process.For example, we will issue a simple sleep command, which creates a new process. This process sleeps for the duration, which is mentioned in the integer value next to the sleep command:

10000 seconds. This means we will not be able to use any other command from the same terminal:$ sle ep 10000

sleep command.

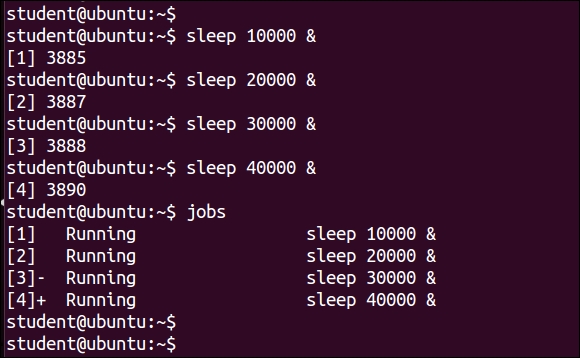

$ sleep 10000 &

The preceding command will create a new process, which will be put to sleep for 10000 seconds; but this time, it will start running in the background. Therefore, we will be able to enter the next command in the Bash terminal.

$ sleep 20000 & $ sleep 30000 & $ sleep 40000 &

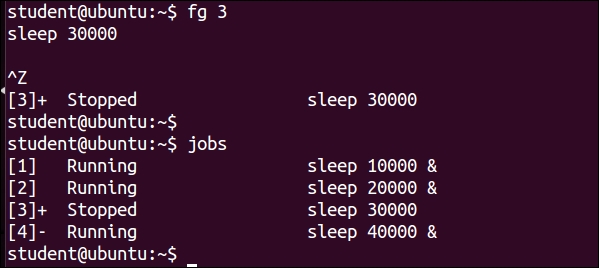

$ jobs

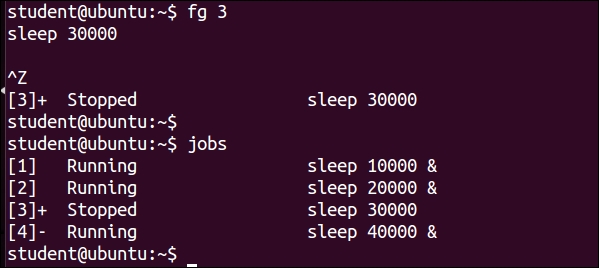

The jobs command lists all the processes running in terminal, including foreground and background processes. You can clearly see their status as running, suspended, or stopped. The numbers in [] show the job ID. The + sign indicates which command will receive fg and bg commands by default. We will study them in the next topics.

$ fg 3

The preceding command will make the job number 3 to run in the foreground instead of the background.

If we want to make the process to stop executing and get it suspended, then press Ctrl + Z. This key combination makes the foreground process to stop executing. Please note that the process has stopped but not terminated.

$ bg job_number $ bg 3

The preceding command will make suspended job numbered process 3 to run in background.

$ jobs –l // This will list jobs with pid $ kill pid or $ kill %job_id // This will kill job $ kill %3

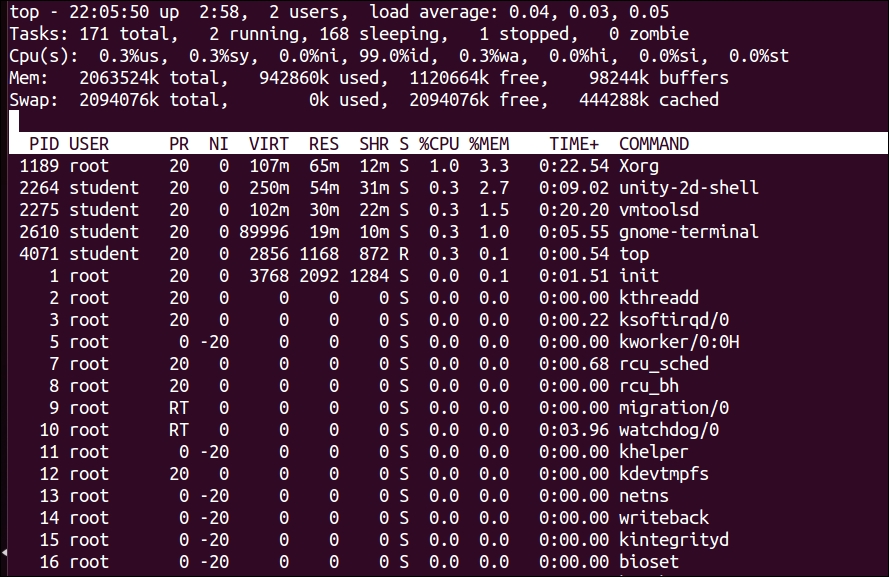

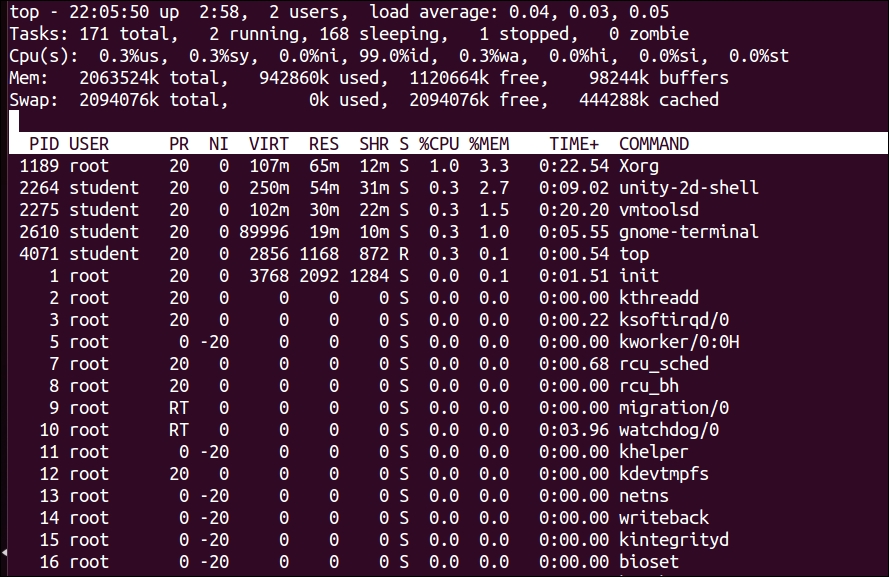

We can view the native performance of various processes in OS using tools which will be discussed further. To view a dynamic real-time view of the top running processes in OS, use the following command:

$top

An explanation of the top command generated output is as follows:

The $top command displays a lot of information about the running system.

The first line of the display is shown as follows:

The description of fields in the first line is as follows:

The second line is shown as follows:

This line shows the summary of tasks or processes. It shows the total number of all the processes, which includes the total number of running, sleeping, stopped, and zombie processes.

The third line is shown as follows:

This line shows information about CPU usage in % in different modes as follows:

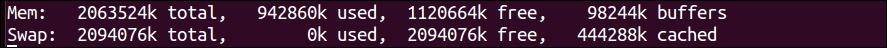

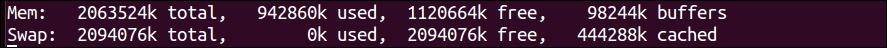

The fourth line is shown as follows:

This line provides information about memory usage. It shows the physical memory that is used, free, available, and used for buffers. The next line shows the swap memory that is available, used, free, and cached.

After this line, we see the table of values with the following columns:

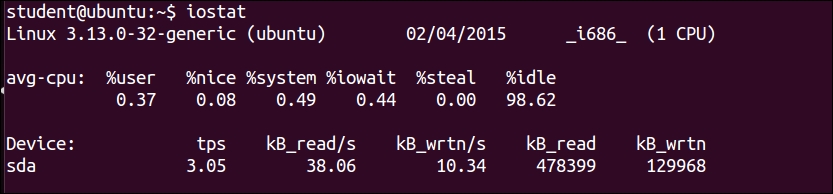

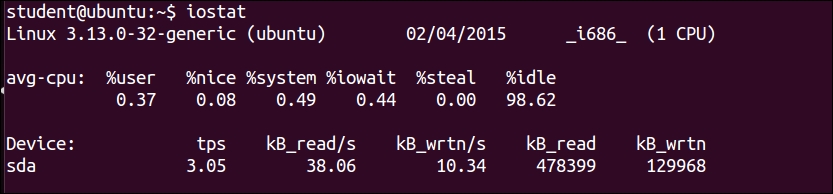

PID: This is the ID of the processUSER: This is the user that is the owner of the processPR: This is the priority of the processNI: This is the "NICE" value of the processVIRT: This is the virtual memory used by the processRES: This is the physical memory used for the processSHR: This is the shared memory of the processS: This indicates the status of the process: S=sleep, R=running, and Z=zombie (S)%CPU: This is the % of CPU used by this process%MEM: This is the % of RAM used by the processTIME+: This is the total time of activity of this processCOMMAND: This is the name of the processLet's take a look at the performance monitoring tools—iostat, vmstat, and sar:

$ iostat

$ iostat –c

Shows only CPU statistics

$ iostat –d

Shows only disk statistics

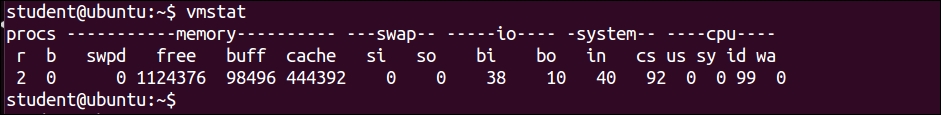

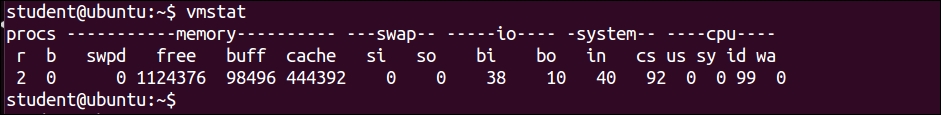

$vmstat

$ vmstat -s

This shows various event counters and memory statistics.

$ vmstat –t 1 5

Runs for every one second stops after executing for five intervals.

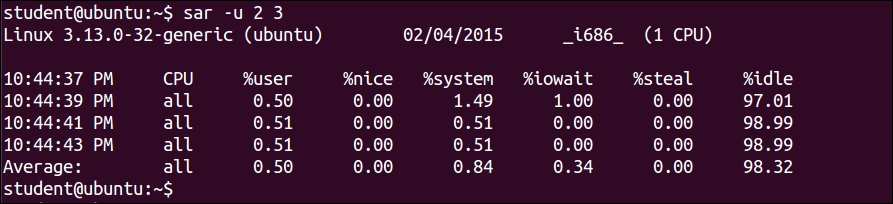

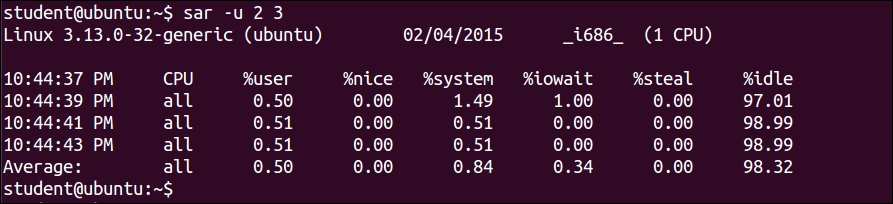

$ sar –u 2 3

This will show the CPU activity report every 2 seconds, 3 times:

Many a times we need to schedule a task for a future time, say in the evening at 8 P.M. on a specific day. We can use the at command in such a situation.

Sometimes we need to repeat the same task at a specific time, periodically, every day, or every month. In such situations, we can use the crontab command.

Let's learn more about the utility of the at command. To use the at command, the syntax is as follows:

$ at time date

The following are the examples of the at command:

Control + D command will save the at job. The task will be executed at 11.15 A.M. This command will log messages to the log.txt file at 11.15 A.M.:$ at 11.15 AM at > echo "Hello World" > $HOME/log.txt at > Control + D

$ at 10am mar 31 2015 at> echo "taxes due" | mail jon at> ^D

$ at 11 am may 20

at command can be listed using the following command:

$ atq

atq command, we can use the following command:

$ atrm job-id

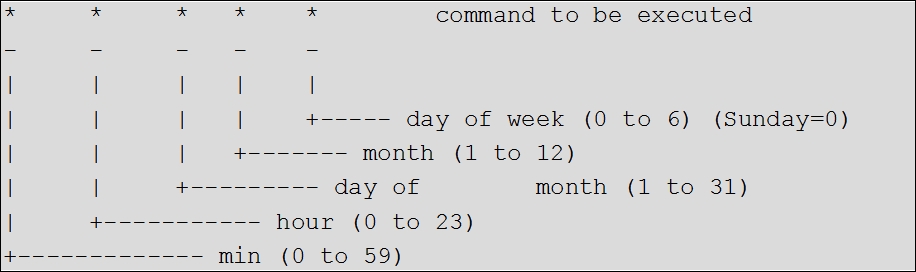

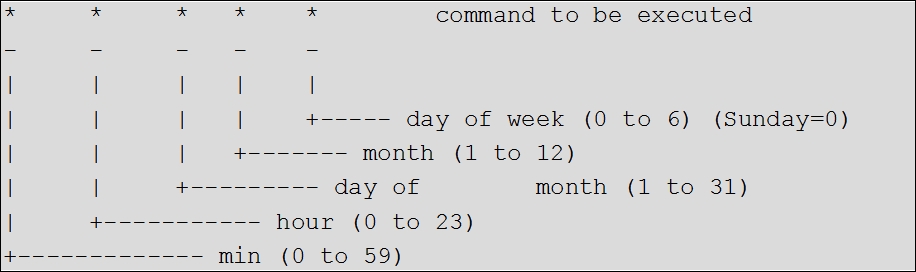

If we need to run a specific task repetitively, then the solution is to use crontab.

The syntax of the command is as follows:

$ crontab –e

This will open a new editor. The following diagram is the syntax to add tasks. The fields to use for repeating tasks at what time are explained here:

Finally, to save the jobs, use the following:

wq # save and quite crontab job

The following are a few examples of the crontab command:

5 * * * * $HOME/bin/daily.job >> $HOME/tmp/out 2>&1

5 0 * * * $HOME/bin/daily.job >> $HOME/tmp/out 2>&1

15 14 1 * * * $HOME/bin/monthly

<ganesh@abc.com>:

0 22 * * 1-5 sendmail ganesh@abc.com < ~/work/email.txt

sendmail utility is used for sending e-mails. We can use the mail utility also as follows:

sendmail user@example.com < /tmp/email.txt

23 0-23/2 * * * echo "run 23 minutes after midn, 2 am, 4 am, everyday 5 4 * * sun echo "run at 5 after 4 every Sunday"

The following are a few more crontab command examples:

|

Min |

Hour |

Day / month |

Month |

Day / week |

Execution time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

45 |

0 |

5 |

1,6,12 |

* |

00:45 hrs on the 5th of January, June, and December. |

|

0 |

18 |

* |

10 |

1-5 |

6.00 P.M. every weekday (Monday-Friday) only in October. |

|

0 |

0 |

1,10,15 |

* |

* |

Midnight on the 1st ,10th, and 15th of the month |

|

5,10 |

0 |

10 |

* |

1 |

At 12.05 and 12.10 every Monday and on the 10th of every month |

We can add macros in the crontab file. Use the following to restart my_program after each reboot:

@reboot /bin/my_program @reboot echo `hostname` was rebooted at `date` | mail -s "Reboot notification" ganesh.admin@some-corp.com

The following is the summary of a few more macros:

|

Entry |

Description |

Equivalent To |

|---|---|---|

|

@reboot |

Run once at startup |

None |

|

@weekly |

Run once a week |

0 0 * * 0 |

|

@daily |

Run once a day |

0 0 * * * |

|

@midnight |

(same as @daily) |

0 0 * * * |

|

@hourly |

Run once an hour |

0 * * * * |

In this chapter, we studied about the basic process management. You learned about the ps command. Using commands like jobs, fg, bg, kill, and pkill, we studied about job management. Later on, you learned about the top, iostat, and vmstat process monitoring tools.

In the next chapter, you will learn about standard input/output, various meta-characters, and text filters used in Shell scripting.

In the last chapter, you studied about basic process management. You learned about the ps command. You also studied about job management using commands such as jobs, fg, bg, kill, pkill as well as various other tools such as top, iostat, and vmstat.

In this chapter, you will cover the following topics:

Normally, Shell scripting involves report generation, which will include processing various text files and filtering their output to finally produce desirable results. Lets start discussing the two Linux commands, namely, more and less:

more: Sometimes we get a very large output on the screen for certain commands, which cannot be viewed completely on one screen. In such cases, we can use the more command to view the output text one page at a time. Add "| more" after the command, as follows:

$ ll /dev | more

The | is called pipe. You will learn more about it in the next chapters. In this command, pressing the spacebar will move the output on the screen one page at a time, or pressing Enter will move the screen by one line at a time.

less: Instead of more, if you use less it will show a screen containing the full text all at once. We can move forward as well as backwards. This is a very useful text filtering tool.

The syntax of usage is as follows:

$ command | less e.g. $ ll /proc | less

This command will show a long listing of directory listing of the /proc folder. Let's say that we want to see if the cpuinfo file is present in the directory or not? Just press the arrow key up or down to scroll through the display. With the more command, you can not scroll backwards. You can move forward only. With page up and down key presses, you can move forward or backward one page at a time, which is very fast.

In addition to scrolling forward or backward, you can search for pattern using / for forward search and ? for backward search. You can use N for repeating the search in a forward or backward direction.

For testing the next few commands, we will need a file with a sequence of numbers 1 to 100. For this, use the following command:

$ seq 100 > numbers.txt

The preceding command created a file with the numbers 1 to 100 on separate lines. The following example shows the usage of the head command:

$ head // will display top 10 lines $ head -3 numbers.txt // will show first 3 lines $ head +5 numbers.txt // will show from line 5. Some shell may not work this command

The following example shows the usage of the tail command:

$ tail // will display last 10 lines $ tail -5 numbers.txt // will show last 5 lines $ tail +15 numbers.txt // will show from line 15 onwards. Some shell may not work

To print lines 61 to 65 from numbers.txt into file log.txt, type the following:

$ head -65 numbers.txt | tail -5 > log.txt

The diff command is used to find differences between two files. Let's see a few examples to find out its usage.

The content of file1 is as follows:

I go for shopping on Saturday I rest completely on Sunday I use Facebook & Tweeter for social networking

The content of file2 is as follows:

Today is Monday. I go for shopping on Saturday I rest completely on Sunday I use Facebook & Tweeter for social networking

Then, type the diff command:

$ diff file1 file2

Output:

0a1 > Today is Monday

In the output, 0a1 tells us that line number 1 is added in file2.

Let's learn another example with line deletion.

The content of file1 is as follows:

Today is Monday I go for shopping on Saturday I rest completely on Sunday I use Facebook & Tweeter for social networking

The content of file2 is as follows:

Today is Monday I go for shopping on Saturday I rest completely on Sunday

Then, type the diff command:

$ diff file1 file2

The output is as follows:

4d3 < I use Facebook & Tweeter for social networking.

In the output, 4d3 tells us that line number 4 is deleted in file2. Similarly, the change command will show us changes in file as well.

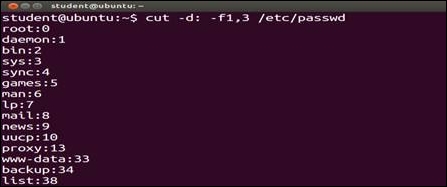

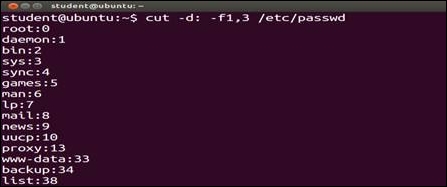

The cut command is used to extract specified columns/characters of a text, which is given as follows:

-c: Will specify the filtering of characters-d: Will specify the delimiter for fields-f: Will specify the field numberThe following are few examples that show the usage of the cut command:

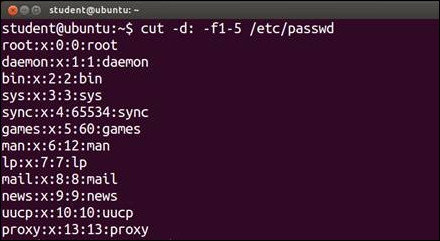

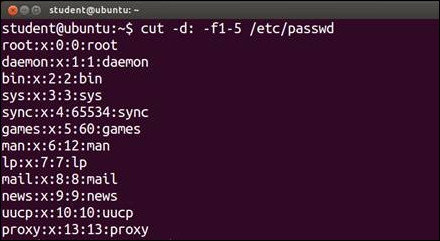

/etc/passwd file, the fields 1 and 3 will be displayed. The display will contain the login name and user ID. We used the –d: option to specify that the field or columns are separated by a colon (:):

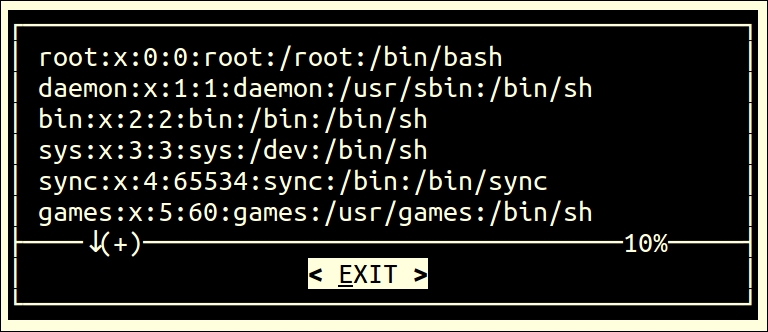

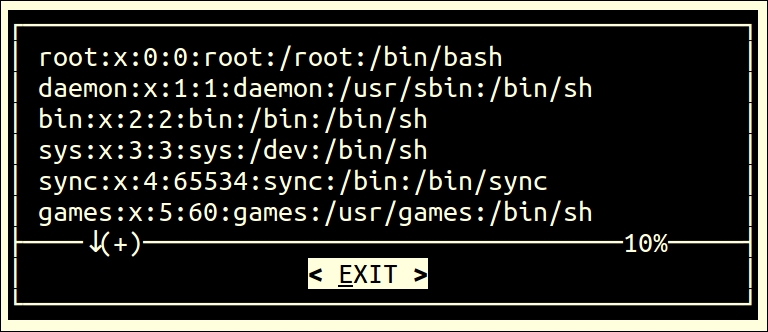

$ cut -d: -f1,3 /etc/passwd

/etc/passwd file, the fields 1 to 5 will be displayed. The display will contains the login name, encrypted password, user ID, group ID, and user name:

$ cut -d: -f1-5 /etc/passwd

emp.lst file:

$ cut -c1-3,8-12 /home/student/emp.lst

date command is sent as an input to the cut command and only the first three characters are printed on screen, which is shown as follows:$ date | cut -c1-3 Mon

Using this utility, we can paste two files horizontally, such as file_1, which will become the first column and file_2 will become the second column:

$ paste file_1 file_2

Consider two files, namely, one.txt and two.txt.

one.txt is as follows:1 India 2 UK 3 Canada 4 US 5 Ireland

two.txt is as follows:1 New Delhi 2 London 3 Toronto 4 Washington 5 Dublin

In this case, for both the files, the common fields are the fields which have serial numbers that are the same in both files. We can combine both files by following command:

$ join one.txt two.txt

The output will be as follows:

1 India New Delhi 2 UK London 3 Canada Toronto 4 US Washington 5 Ireland Dublin

The comm command shows the lines unique to file_1, file_2 along with the common lines in them. We can use various options while using the command in the scripts:

$ cat file_1 Barack Obama David Cameron Narendra Modi $ cat file_2 Barack Obama Engela Merkel Vladimir Putin $ comm –nocheck-order file_1 file_2 Barack Obama David Cameron Engela Merkel Narendra Modi Vladimir Putin

In the preceding example, we can see:

file_1file_2The output shows that the unique files in file_1 are David Cameron and Narendra Modi. Unique files in the second file are Engela Merkel and Vladimir Putin. The command name in both the files is Barack Obama, which is displayed in the third column.

The tr command is a Linux utility for text processing such as translating, deleting, or squeezing repeated characters, which is shown as follows:

$ tr '[a-z]' '[A-Z]' < filename

This will translate the lower case characters to upper case:

$ tr '|' '~' < emp.lst

This will squeeze multiple spaces into a single space:

$ ls –l | tr -s " "

In this example, the -s option squeezes multiple contiguous occurrences of the character into a single char.

Additionally, the -d option can remove the characters.

Sort: It sorts the contents of a text file, line by line.

-n: Will sort as per the numeric value-d: Will sort as per the dictionary meaning-r: Will sort in the reverse order-t: Option to specify delimiter for fields+num: Specifies sorting field numbers-knum: Specifies sorting filed numbers$ sort +4 sample.txt: This will sort according to the 4th field$ sort –k4 sample.txt: This will sort according to the 4th field|

Sr |

Examples of command usage |

Explanation |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

sort |

Alphabetically sorting of lines |

|

2 |

sort -u |

Duplicate entries are sorted |

|

3 |

sort -r |

Reverse sort |

|

4 |

sort-n -k3 |

Numerical sorting of the 3rd field |

You will learn the very useful concept of I/O redirection in this section.

All I/O, including files, pipes, and sockets, are handled by the kernel via a mechanism called the file descriptor. A file descriptor is a small unsigned integer, an index into a file-descriptor table maintained by the kernel and used by the kernel to reference open files and I/O streams. Each process inherits its own file-descriptor table from its parent. The first three file descriptors are 0, 1, and 2. File descriptor 0 is standard input (stdin), 1 is standard output (stdout), and 2 is standard error (stderr). When you open a file, the next available descriptor is 3, and it will be assigned to the new file.

When a file descriptor is assigned to something other than a terminal, it is called I/O redirection. The shell performs redirection of output to a file by closing the standard output file descriptor 1 (the terminal) and then assigning that descriptor to the file. When redirecting standard input, the shell closes file descriptor 0 (the terminal) and assigns that descriptor to a file. The Bash shells handle errors by assigning a file to the file descriptor 2.

The following command will take input from the sample.txt file:

$ wc < sample.txt

The preceding command will take content from the sample.text file. The wc command will print the number of lines, words, and characters in the sample.txt file.

$ echo "Hello world" > log.txt

This command will redirect output to be saved in the log.txt file.

$ echo "Welcome to Shell Scripting" >> log.txt

This command will append the Hello World text in the log.txt file.

The single > will overwrite or replace the existing text in log file. And double >> will append the text in the log file.

Let's see a few more examples:

$ tr '[A-Z]' '[a-z]' < sample.txt

The preceding tr command will read text from the sample.txt file. The tr command will convert all uppercase letters to lower case letters and will print converted text on screen:

$ ls > log.txt $ cat log.txt

The output of command will be as follows:

dir_1 sample.txt extra.file

In this example command, ls is sending directory content to file log.txt. Whenever we want to store the result of the command in the file, we can use the preceding example.

$ date >> log.txt $ cat log.txt

Output:

dir_1 dir_2 file_1 file_2 file_3 Sun Sept 17 12:57:22 PDT 2004

In the preceding example, we are redirecting and appending the result of the date command to the log.txt file.

$ gcc hello.c 2> error_file

The gcc is a C language compiler program. If an error is encountered during compilation, then it will be redirected to error_file. The > character is used for a success result and 2> is used for error results redirection. We can use error_file for debugging purposes:

$ find . –name "*.sh" > success_file 2> /dev/null

In the preceding example, we are redirecting output or success results to success_file and errors to /dev/null. /dev/null is used to destroy the data, which we do not want to be shown on screen.

$ find . –name "*.sh" &> log.txt

The preceding command will redirect both output and error to log.txt.

$ find . –name "*.sh" > log.tx 2>&1

The preceding command will redirect result to log.txt and send errors to where the output is going, such as log.txt.

$ echo "File needs an argument" 1>&2

The preceding command will send a standard output to the standard error. This will merge the output with the standard error.

The summary of all I/O redirection commands will be as follows:

|

< sample.txt |

The command will take input from |

|

> sample.txt |

The success result will be stored in |

|

>> sample.txt |

The successive outputs will be appended to |

|

2> sample.txt |

The error results will be stored in |

|

2>> sample.txt |

The successive error output will be appended to |

|

&> sample.txt |

This will store success and errors, such as in |

|

>& sample.txt |

This will store success and errors, such as in |

|

2>&1 |

This will redirect an error to where output is going |

|

1>&2 |

This will redirects output to where error is going |

|

>| |

This overrides no clobber when redirecting the output |

|

<> filename |

This uses the file as both standard input and output if a device file (from |

|

cat xyz > success_file 2> error_file |

This stores success and failure in different files |

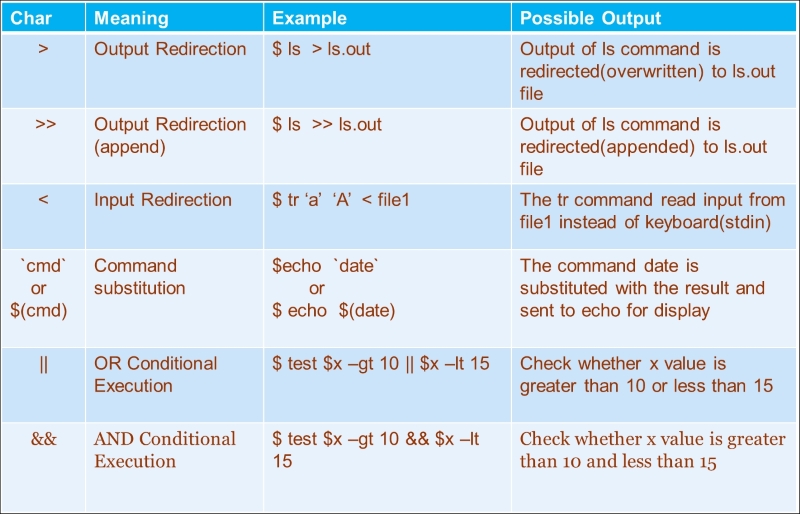

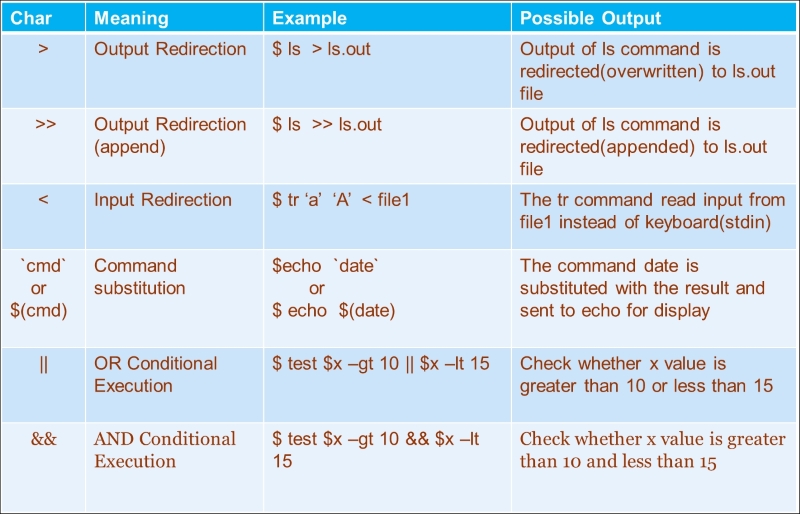

The following is the summary of various metacharacters:

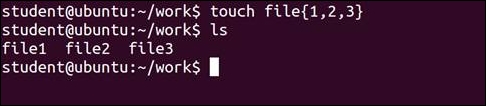

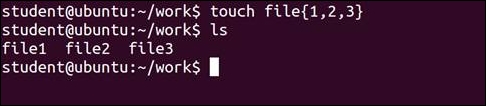

$ touch filea fileb filec fileab filebc filead filebd filead $ touch file{1,2,3}

Try the following command out:

$ ls s* $ ls file $ ls file[abc] $ ls file[abc][cd] $ ls file[^bc] $ touch file file1 file2 file3 … file20 $ ls ????? file1 file2 file3 $ ls file* file file1 file10 file2 file3 $ ls file[0-9] file1 file2 file3 $ ls file[0-9]* file1 file10 file2 file3 $ ls file[!1-2] file3

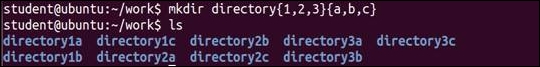

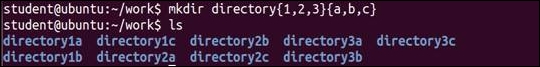

Curly braces allow you to specify a set of characters from which the shell automatically forms all possible combinations. To make this work, the characters to be combined with the given string must be specified as a comma separated list with no spaces:

$ touch file{1,2,3} $ ls

$ mkdir directory{1,2,3}{a,b,c} $ ls

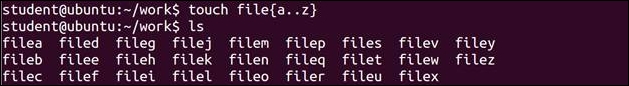

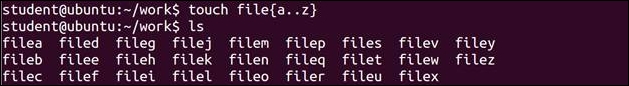

$ touch file{a..z} $ ls

The following is the summary of various io-redirection and logical operators:

For example:

$ ls || echo "Command un-successful" $ ls a abcd || echo "Command un-successful"

These commands will print Command un-successful if the ls command is unsuccessful.

For learning pattern matching, we will ensure that the pattern that we will search should be highlighted when the searched pattern is found.

The configuration file for vi is /etc/vimrc.

In the vi editor, give the following command to highlight search:

|

Sr. |

Commands |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

|

This highlights search pattern |

|

2 |

|

Show when you are in insert mode |

|

3 |

|

Ignore case when searching |

|

4 |

|

Shows case sensitive search |

The mentioned user should open the file in vi, press the Esc button so that it goes into command mode and then enter colon followed by these commands.

The following are commands for pattern search and replace:

The following is an example of regular expression for replacing Tom by David:

:1,$s/tom/David/g // from line 1 to end ($), replace tom by David :1,$s/\<[tT]om\>/David/g // start and end of word \< \>

This is another example of regular expression.

Create the love.txt file, as follows:

Man has love for Art World is full of love Love makes world wonderful love looove lve love Love love lover loves I like "Unix" more than DOS I love "Unix"/ I said I love "Unix" I love "unix" a lot

Use the following commands for testing pattern searching facilities:

The g/RE/p stands for globally search for the regular expression (RE) and print out the line.

Return status – success 0, pattern not found 1, file not found 2.

$ ps -ef | grep root

The preceding command will show all processes running currently whose user ID is "root".

$ ll /proc | grep "cpuinfo"

The preceding command will show the file with the name cpuinfo from the /proc directory.

$ grep –lir "text" * // only file names // $ grep –ir "text" dir_name // show lines of files //

We will try the following commands on the love.txt file:

We will create a new file sample.txt, as follows:

Apple Fruit 5 4.5 Potato Vegetable 4 .5 Onion Vegetable .3 8 Guava Fruit 5 1.5 Almonds Nuts 1 16 Tomato Vegetable 3 6 Cashew Nuts 2 12 Mango Fruit 6 6 Watermelon Fruit 5 1

We will try the following commands on the sample.txt file:

In this chapter, you learned about using more, less, head, and tail commands, and text processing tools like cut, paste, comm, and uniq. We also learned what standard input, output, and standard error are. Later on, you learned about metacharacters and pattern matching using vi and grep.

In the next chapter, you will learn about analyzing shell interpretation of commands, working with command substitution, command separators, and pipes.

In the last chapter, you learned about using more, less, head, and tail commands, and text processing tools like diff, cut, paste, comm, and uniq. You learned what standard input, output, and standard error are. You also learned about metacharacters and pattern matching using vi and grep.

In this chapter, you will cover the following topics:

When we log in, the

$ sign will be visible in the shell terminal (# prompt if logged in as root or administrator). The Bash shell runs scripts as interpreter. Whenever we type a command, the BASH shell will read them as series of words (tokens). Each word is separated by a space ( ), semi colon (;), or any other command delimiter. We terminate the command by pressing the Enter key. This will insert a new line character at the end of the command. The first word is taken as a command, then consecutive words are treated as options or parameters.

The shell processes the command line as follows:

$name and $user) is performedecho `cal` and echo `date`) is performedrm *)The sequence of execution of different types of commands will be as follows:

l, ll, egrep, and similar)for, if, while, and similar)bg, fg, source, cd, and similar)bin and sbin folder)Whenever a command is given in a shell or terminal, the complete command will be tokenized, and then shell will check if the command is alias.

Aliases, keywords, functions, and built-in commands are executed in the current shell, therefore their execution is fast as compared to executable external commands or scripts. Executable external commands will have a corresponding binary file or Shell script file in the file system, which will be stored in any folder. The shell will search the binary file or script of a command by searching in the PATH environment variable. If we want to know what the type of command it is, such as if it is an alias or a function or internal command, it can be found out by the type built-in command, which is shown as follows:

$ type mkdir mkdir is /bin/mkdir $ type cd cd is a shell builtin $ type ll ll is aliased to `ls -alF' $ type hello hello is a function hello () { echo "Hello World !"; } $ type for for is a shell keyword

Bash has provision of a few built-in commands to change the sequence of command line processing. We can use these built-in commands to change default behavior of command-line processing.

$ command ls

This will make aliases and functions be ignored and the external ls command will execute.

builtin command will work as follows:

$ builtin BUILT-IN

This will ignore aliases and functions from the shell environment and only built-in commands and external commands will be processed.

break built-in command will work as follows:

$ builtin –n break

This will make the break built-in to be disabled and the external command break will be processed.

$ enable

|

. |

command |

eval |

history |

pwd |

test |

|

.. |

compgen |

exec |

jobs |

read |

times |

|

[ |

complete |

exit |

kill |

readarray |

trap |

|

alias |

compopt |

export |

let |

readonly |

true |

|

bg |

continue |

false |

local |

return |

type |

|

bind |

declare |

fc |

logout |

set, unset |

typeset |

|

break |

dirs |

fg |

mapfile |

shift |

ulimit |

|

builtin |

disown |

getopts |

popd |

shopt |

umask |

|

caller |

echo |

hash |

printf |

source |

unalias |

|

cd |

enable |

help |

pushd |

suspend |

wait |

$ enable –n built-in-command

For example: $ enable –n test

In this case, in my shell, if we have to test an external command, then instead of the internal test command, the external test command will be executed.

In Shell scripting, we need to check if the last command has successfully executed or not. For example, whether a file or directory is present or not. As per the result, our Shell script will continue processing.

For this purpose, the BASH shell has one status variable ?. The status of the last command execution is stored in ?. The range of numerical value stored in ? will be from 0 to 255. If successful in execution, then the value will be 0; otherwise, it will be non-zero, which is as follows:

$ ls $ echo $? 0

Here, zero as the return value indicates success.

In the next case, we see:

$ ls /root $ echo $? 2

Here, non-zero value indicates an error in the last command execution.

In the next case, we see:

$ find / -name hello.c $ echo $?

The return value will indicate if the hello.c file is present or not!

In the keyboard, there is one interesting key, the backward quote such as "`". This key is normally situated below the Esc key. If we place text between two successive back quotes, then echo will execute those as commands instead of processing them as plane text.

Alternate syntax for $(command) is the backtick character "`", which we can see as follows:

$(command) or `command`

For example:

$ echo "Hello, whoami"

Hello, whoami:

Hello, whoami

$ echo "Hello, `whoami`." Hello, student

When we enclose whoami text in the "`" character, the same text which was printed as plain text will run as a command, and the command output will be printed on screen.

$ echo "Hello, $(whoami)." Hello, student.

Same like the earlier explanation.

echo "Today is date"

Output:

Today is date

A similar example:

echo "Today is `date`"

Or:

echo "Today is $(date)"

Output:

Today is Fri Mar 20 15:55:58 IST 2015

Further, similar examples include:

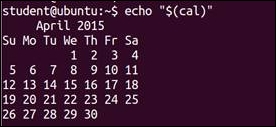

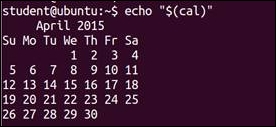

$ echo $(cal)

In this example, new lines are lost.

Another example:

$ echo "$(cal)"

Here, the display is properly formatted.

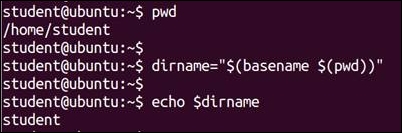

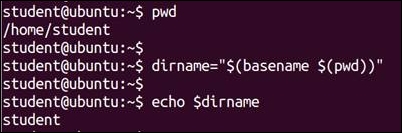

Next, nesting of commands is as follows:

$ pwd /home/student/work $ dirname="$(basename $(pwd)) " $ echo $dirname

This command shows us that the base directory for the current directory is student.

Commands can also be combined in such a way that they are executed in a particular sequence.

A command line can consist of multiple commands. Each command is separated by a semicolon, and the command line is terminated with a newline. The exit status is that of the last command in the chain of commands.

The first command is executed, and the second one is started as soon as the first one has finished.

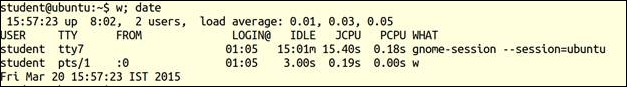

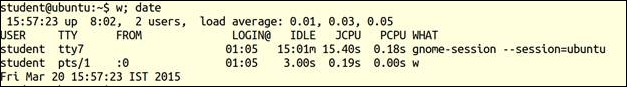

$ w; date

Output:

$ w ; date > whoandwhen

Output of the date command will be redirected to the whoandwhen file.

In the preceding example, we can see that when we put multiple commands on the same line, but separated by the ";" command, then those commands execute sequentially one by one.

$ date; who am i Tue Mar 10 23:21:38 PDT 201 student pts/0 2015-03-10 23:12 (:0.0)

In the preceding example, the date command is executed first and the who am I command will be executed next. Both the commands are typed on same lines, separated by the ";" " command.

Commands may also be grouped so that all of the output is either piped to another command or redirected to a file.

$ ( ls; pwd; date ) > outputfile

The output of each of the commands is sent to the file called outputfile. The spaces inside the parentheses are necessary.

$ ( w ; date ) > whoandwhen

The output of the w command and date will be redirected to the whoandwhen file:

$ (echo "***x.c***";cat x.c) > log.txt

Output:

This redirects the content of x.c with a heading ***x.c*** to the file out.

$ (pwd; ls; date) > log.txt

Output:

This redirects output of commands pwd, ls, and date in the log.txt file.

Let's now take a look at logical operators.

The first command is started in the background to continue until it has finished; immediately after starting first command, the second command is started and it will run in the foreground:

$ find / -name "*.z" & s ---------------- ----- Command1 command2

In the preceding example, first command such as find will start running in the background and while the find command is running in background, the ls command will start running in foreground.

The second command is only started if the first command is successful. To achieve this, the shell checks the exit (return) status of the first command and starts the second command only if and when that exit status is found to be "0".

$ ls /home/ganesh && echo "Command executed successfully" Since we are working as user ganesh, $ ls /root && echo "Command executed successfully"

Since we are working as a normal user, we cannot access the /root directory. Therefore, nothing will be printed on screen.

The second command is only started if the first command fails. The shell checks the exit status of the first command and starts the second command only if that exit status is not equal to "0".

$ ls /root || echo "Command execution failed"

Example:

$ ls || echo "command ls failed"

In the preceding example, if ls runs successfully, then echo will not be called. If the ls command fails such as $ ls /root and if user is not root, then ls will fail and the echo command will print command ls failed.

When && or || are used, the exit status of the first command is checked first, then the decision to perform the next will be taken.

For example:

$ ls $ echo $? 0 $ ls /root ls: /root: Permission denied $ echo $? 1 $ tar cvzf /dev/st0 /home /etc | | mail -s "Something went wrong with the backup" root

If we give the command as follows:

$ cd /home/student/work/temp/; rm –rf *

Initially, the shell will change to the /home/student/work/temp folder, and then it will delete all files and folders.

If we give the command as follows:

cd /backup/ol/home/student/work/temp/ && rm * -rf

This will first change to the required folder, and then the rm command will be called for deletion. The problem with ";" is that even if the shell fails to change to the required folder, the rm command will execute and it will delete all the files and folders from your original folder. This will be really dangerous.

For example:

$ [[ "a" = "b" ]]; echo ok ok

In this case, the [[ ]] expression will evaluate to false. Since the semicolon will not check the status of the earlier command, ok will be printed even if the first [[ ]] fails.

$ [[ "a" = "b" ]] && echo ok

In this case, the [[ ]] expression will evaluate to false. As the first expression is false, the "&&" operator will not proceed to execute the next command.

In this case, ok will be printed only if [[ ]] is true.

We have already used pipes in many earlier sessions. It is a tool for inter-process communication.

$ command_1 | command_2

In this case, the output of command_1 will be send as an input to command_2. The limitation is that the communication is half duplex. This means the data can flow in only one direction. Normally for inter-process communication, you need to open files then get the file descriptor. This will be used to write to the pipe file. Again, we need to create a Fifo file by special commands. The preceding technique simplifies all this process. We only need to insert "|" in between the two processes. The operating system creates one intermediate buffer. This buffer is used for storing the data from one command and will be used again for the second command.

A simple example is as follows:

$ who | wc

The preceding simple command will be carrying out three different activities. First, it will copy the output of the who command to the temporary file. Then the wc command will read the temporary file and display the result. Finally, the temporary file will be deleted.

Normally, there will be two processes. The first command is the writer process. The second process is the reader process. The writer process will write to temp_file and the reader will read from temp_file. Examples of writer processes are ps, ls, and date. Examples of reader processes are wc, cat, and sort.

In this chapter, you learned about how the shell interprets any command entered on the command line. We also studied command substitution and separators in detail.

In the next chapter, you will learn about variables and environment variables. You will also learn about how to export environment variables, and then you will learn about read only variables, command line arguments, and arrays.

In the last chapter, you learned about how shell interprets any command, which is entered in the terminal or the command line. We also studied command substitution and separators in detail.

In this chapter, we will cover following topics:

Let's learn about creating variables in shell.

Declaring variables in Linux is very easy. We just need to use the variable name and initialize it with the required content.

$ person="Ganesh Naik"

To get the content of the variable we need to prefix $ before the variable.

For example:

$ echo person person $ echo $person Ganesh Naik

The unset command can be used to delete a variable:

$ a=20 $ echo $a $ unset a

The unset command will clear or remove the variable from shell environment as well.

$ person="Ganesh Naik" $ echo $person $ set

Here, the

set command will show all variables declared in shell.

$ declare -x variable=value

Here, the declare command with the –x option will make it an environmental or global variable. We will understand more about environmental variables in the next sessions.

$ set

Again here, the set command will display all variables as well as functions that have been declared.

$ env

Here, the env command will display all environmental variables.

variable=value

Whenever we declare a variable, that variable will be available in the current terminal or shell. This variable will not be available to any other processes, terminal, or shell.

Let's write a Shell script as follows:

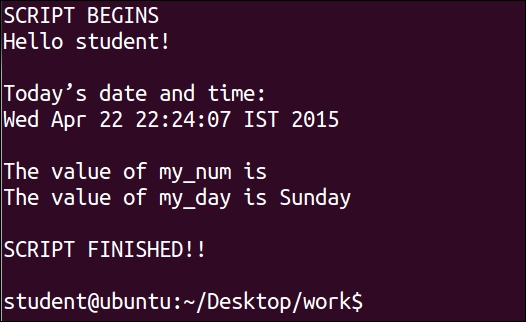

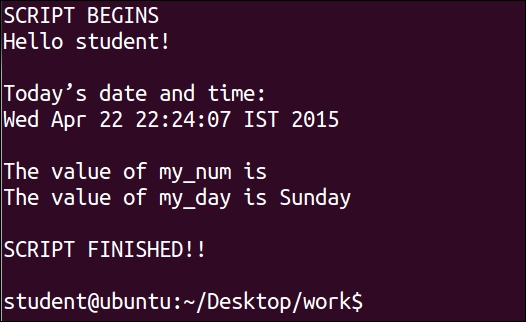

#!/bin/bash # This script clears the window, greets the user, # and displays the current date and time. clear # Clear the window echo "SCRIPT BEGINS" echo "Hello $LOGNAME!" # Greet the user echo echo "Today's date and time:" date # Display current date and time echo # Will print empty line my_num=50 my_day="Sunday" echo "The value of my_num is $my_num" echo "The value of my_day is $my_day" echo echo "SCRIPT FINISHED!!" echo

Let's see the effect of $, "", '' and \ on variable behavior:

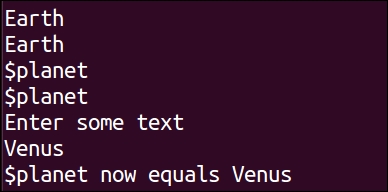

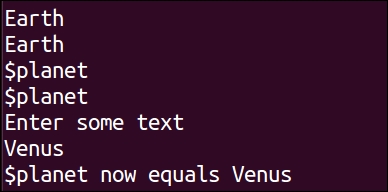

#!/bin/bash planet="Earth" echo $planet echo "$planet" echo '$planet' echo \$planet echo Enter some text read planet echo '$planet' now equals $planet exit 0

Output:

You will learn about the read command in the next chapters. Using read, we can ask the user to enter data, which can be stored in a variable.

From the preceding script execution, we can observe that $variable and "$ variable" can be used for displaying the content of the variable. But if we use '$variable' or \$variable, then special functionality of the $ symbol is not available. The $ symbol is used as a simple text character instead of utilizing its special functionality of getting variable content.

Environmental variables are inherited by any subshells or child processes. For example, HOME, PATH. Every shell terminal has the memory area called environment. Shell keeps all details and settings in the environment. When we start a new terminal or shell, this environment is created every time.

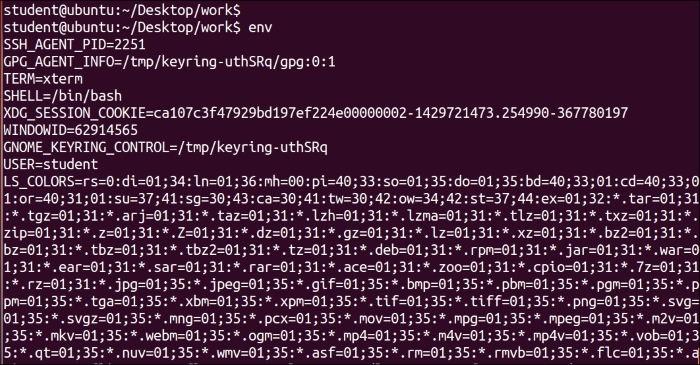

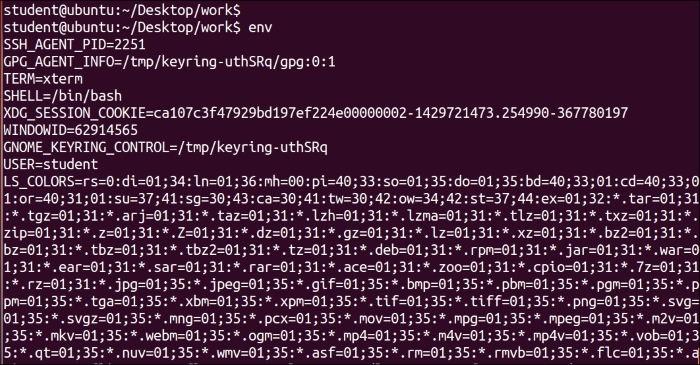

We can view environment variables by the following command:

$ env

Or:

$ printenv

Output:

This is the output of the $ env command. The list of environment variables will be quite extensive. I advise you to browse through the complete list. We can change the content of any of these environment variables.

Environmental variables are defined in a terminal or shell. They will be available in subshells or child shells created from the current shell terminal. You will learn about these activities in the next few sections. You have already learned that every command in shell creates a new subshell from the current shell.

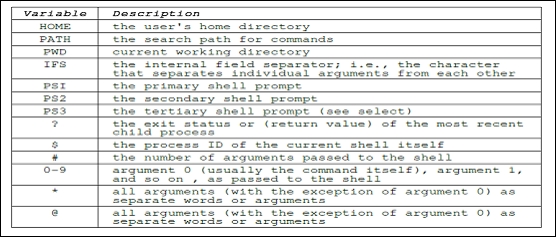

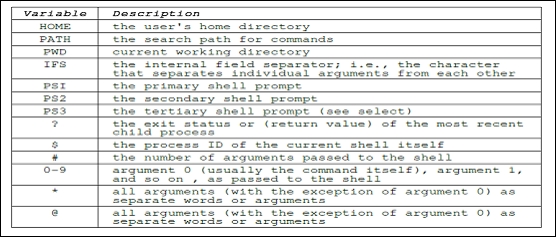

The following is a brief summary of the few environmental variables:

Whenever any user logs in, the /etc/profile Shell script is executed.

For every user, the .bash_profile Shell script is stored in the home folder. The complete path or location is /home/user_name/.profile.

Whenever a new terminal is created, every new terminal will execute the script .bashrc, which is located in the home folder of every user.

In the current shell, we can create and store user defined variables. These may contain characters, digits, and "_". A variable should not start with a digit. Normally for environment variables, upper case characters are used.

If we create a new variable, it will not be available in subshells. The newly created variable will be available only in the current shell. If we run Shell script, then local variables will not be available in the commands called by Shell script. Shell has one special variable $$. This variable contains the process ID of the current shell.

Let's try a few commands:

$ echo $$ 1234

This is the process ID of the current shell.

$ name="Ganesh Naik" $ echo $name Ganesh Naik

We declared the variable name and initialized it.

$ bash

This command will create a new subshell.

$ echo $$ 1678

This is the process ID of the newly created subshell.

$ echo $name

Nothing will be displayed, as the local variables from the parent shell are not inherited in the newly created child shell or subshell:

$ exit

We will exit the subshell and return to the original shell terminal.

$ echo $$ 1234

This is the process ID of the current shell or parent shell.

$ echo $name Ganesh Naik

This is displaying the variable's presence in the original shell or parent shell.

Variables created in the current shell will not be available in a subshell or child shell. If we need to use a variable in a child shell, then we need to export them using the export command.

Using the export command, we are making variables available in the child process or subshell. But if we declare new variables in the child process and export it in the child process, the variable will not be available in parent process. The parent process can export variables to child, but the child process cannot export variables to the parent process.

Whenever we create a Shell script and execute it, a new shell process is created and the Shell script runs in that process. Any exported variable values are available to the new shell or to any subprocess.

We can export any variable as follows:

$ export NAME

Or:

$ declare -x NAME

Let's understand the concept of exporting the variable by the following example:

$ PERSON="Ganesh Naik" $ export PERSON $ echo $PERSON Ganesh Naik $ echo $$ 515

The process ID of the current shell or parent shell is 515.

$ bash

This will start a subshell.

$ echo $$ 555

This is the process ID of new or subshell.

$ echo $PERSON Ganesh Naik $ PERSON="Author" $ echo $PERSON Author $ exit

This will terminate the subshell, and will be placed in the parent shell.

$ echo $$ 515

This is the process ID of the parent shell.

$ echo $PERSON Author