|

|

The English language has at least four words related to “thing”. Consider these definitions from Merriam-Webster:

thing : a separate and distinct individual quality, fact, idea, or usually entity

entity 2 : something that has separate and distinct existence1 and objective or conceptual reality

object 1a : something material that may be perceived by the senses

concept 1 : something conceived in the mind : thought, notion

I added the italics to the second half of the word “something” in the definitions above to emphasize that the definitions of entity, object, and concept depend on the definition of thing. You’ll also see that there is a partial circularity between the definition of “thing” and the definition of “entity”, because each definition uses the other word.

The worlds of software development and database development have heavily overloaded two of these words, namely the words “entity” and “object”. (They’ve avoided the word “thing”, I think, because who would boast of being skilled at thing-relationship modeling or thing-oriented programming?) Let’s make sure we understand what these words meant before technologists got a hold of them.

In ordinary English, the words “thing” and “entity” are pretty much identical in meaning. “Entity” can be thought of as the technical term for “thing”. For those who are familiar with entity-relationship (E-R) modeling, please note how the ordinary English definition of “entity” is completely different from the E-R definition. Those familiar with philosophy and semantics will recognize that the word “object” is usually used in those fields to represent the same meaning as the ordinary English meaning of “entity”.

The Merriam-Webster definition for “entity” makes a very important distinction between two kinds of things: objective things and conceptual things.

An objective thing is something whose existence can be verified through the senses. Things that stimulate the senses include light and sound, but there’s an important kind of objective thing that the dictionary defines as an “object”: “something material that may be perceived by the senses.” Something “material” is something that is made of matter. What is matter?

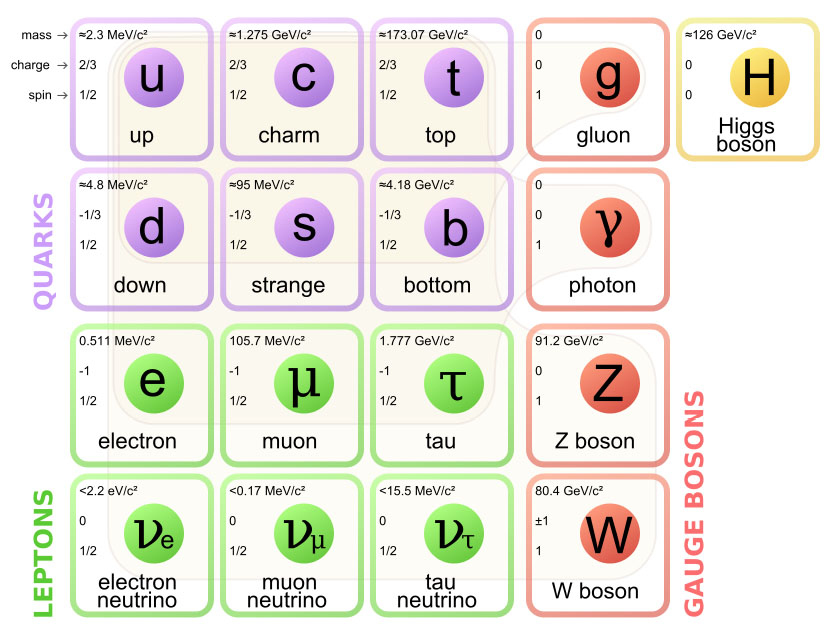

At the current limits of scientific knowledge of the universe, we believe that all matter consists of so-called elementary particles, which come in a relatively small number of types. (See Figure 2-1.) We call them elementary because, as far as we know, they aren’t composed of anything else. All other matter is composed of them. An electron is an elementary particle. Protons and neutrons are composed of the elementary particles called quarks. If a relatively fixed number of electrons, protons, and neutrons remain in a relatively static relationship to each other—protons and neutrons bound together in a nucleus, and electrons orbiting the nucleus—we have what we call an atom. We call atoms that are bound to each other in certain spatial relationships molecules. Molecules can get quite large, and can form, among other things, minerals, proteins and other raw materials of living things, and, very simply, everything that we can see or touch.

In ordinary parlance, when enough matter in relatively static spatial relationships is aggregated together to the point where we can see and touch it, we call the aggregate an object. If, for instance, you looked at your desk and saw a pencil and a pen, you would say that these were two objects on your desk—and you would be right, despite the fact that you will sharpen the pencil and it will get shorter, and the pen will gradually run out of ink. You have an intuitive and approximate but very useful concept of what an object is. In fact, your idea of an object is a concept that is widely shared by many persons.

Based on these observations, we can define the object of ordinary parlance and experience using a technique called induction. Our induction rests on two simple definitions.

- An elementary particle of matter (that is, an electron or other lepton, or a quark) is an object.

- Any collection of objects in relatively static spatial arrangements to each other is an object.

Figure 2-1. The Elementary Particles

The first definition is really just a linguistic definition. It says that we will use the term “object” to refer to, among other things, elementary particles of matter. An electron is an object, a quark is an object, etc.

The second definition is where the trick is. It says that objects are built from other objects. On the surface of it, this sounds like a circular definition: where does the object begin? So let’s take this definition apart to see how it works.

If we are going to build objects from objects, what objects can we start with? Well, in definition number one we said that we would call the elementary particles of matter objects, so then we can build our first objects from elementary particles. Let’s put together three elementary particles—three quarks—to make a proton. The three quarks stick very closely together—that’s a relatively static spatial arrangement. So a proton, built from objects which are elementary particles, qualifies by definition number two as an object. Next, let’s grab an electron—which is also an object because it’s an elementary particle, too—and put it in orbit around the proton. An orbit is a relatively static spatial arrangement, so the electron/proton combination—which happens to be a hydrogen atom—must be an object, too.

Relax—I won’t go on constructing the universe one particle at a time! But hopefully I’ve gone far enough that you can see how induction works. We start with our starter kit of objects—elementary particles of matter—and from those we can build all objects, eventually up to objects we can see and touch.

This inductive definition reflects the reality that all objects, except the elementary particles, are built from other, simpler objects. We say that they are composite objects, composed of other objects called components.

We’ve now covered one-half of the definition of entity. We know what objective entities are, and, more particularly, we know what objects are. Let’s turn now to conceptual entities: what are they?

A concept is, according to Merriam-Webster’s Online Dictionary, a thought or notion; essentially, an idea. We know that persons have ideas, and that they exist in a person’s brain as a configuration of neurons, their physical states, and their interconnections. We also know that there are many ideas that are shared by persons—many ideas that are known by the same names, understood in approximately the same way, and enable communication. For instance, if you are reading this book and understanding even a part of it, it is because you and I share some of the same ideas, or concepts, about what the words I am using mean.

The interesting thing about widely shared concepts is that, unlike objects, they have no place or time: they are not confined to a geographic location or a particular point in time, or even to the same set of words. For instance, the concepts of the number “one”, of numbers in general, and of counting, are understood by all human cultures, even though people who speak different languages use different names for any given number. In light of this, it would be wrong to say, “The number one is here and not there”, or, “The number one began at this point in time and will go out of existence at this other point in time.” Perhaps if our knowledge of history were perfect we could identify the point in time at which the first person had the idea of “one” for the first time. But we don’t know history to that degree of detail, and it’s irrelevant anyway. The only way in which the number one would come to an end would be if all humans ceased to exist. If that happened, there would be no one to record the event, so it would be irrelevant. We therefore treat the number one, and similar shared concepts, as if they have no time or place, and if we are wise we recognize that the names of concepts are just symbols that are quite separate from the concepts they represent.

In summary, then, an entity is a thing that exists either objectively or conceptually. An object is an objective entity that is either an elementary particle of matter or is composed of other objects in relatively fixed spatial relationships. A conceptual entity is a concept; essentially, an idea.

As will be explained in greater detail in subsequent chapters, the word “entity” will be used in exactly the sense of the definition quoted above, un-overloaded, as meaning any thing that exists, whether it is an object (whose existence can be objectively verified) or a concept (whose existence is merely as an idea). The chapter on entity-relationship data modeling will examine the word “entity” as it is used in that context.

The word object will also be used in exactly the sense of the definition quoted above, to mean a material entity, in contrast to concept, which is a conceptual entity. We will examine the meaning of object in object-oriented programming, but we’ll save that for later.

|

Key Points

|

Chapter Glossary

entity : something that has separate and distinct existence and objective or conceptual reality (Merriam-Webster)

object : something material that may be perceived by the senses (Merriam-Webster)

concept : something conceived in the mind : thought, notion (Merriam-Webster)

composite : made up of distinct parts (Merriam-Webster)

component : a constituent part (Merriam-Webster)