|

|

You’ve very excited to have been brought into a new specialty coffee shop business. The owner is starting small, but has high hopes of taking his chain to an international level. You’ve been selected to design the information system and its database that will enable the chain to operate a few stores in one locality but eventually expand to operations in several countries.

You’ve learned the value and discipline of model-driven development. You understand that your first task is to understand the business owner’s requirements, and the business itself. You plan to document relevant aspects of the business, in COMN, so that you can then figure out what data will be needed to support operations and what analytics will be needed to support marketing. Only then will you begin the work of selecting appropriate DBMSs and designing the implementation classes for a high-quality, high-performance information system that will help this business go from inception to success.

Analysis: Documenting Real-World Entities

Every business involves certain real-world object classes and certain types of concepts which we can very quickly identify as relevant to our data modeling task. Real-world object classes include customers, employees, physical facilities, vendors, and products. Concept types include orders, purchases, and accounts payable and receivable.

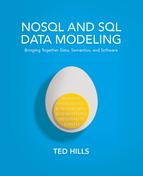

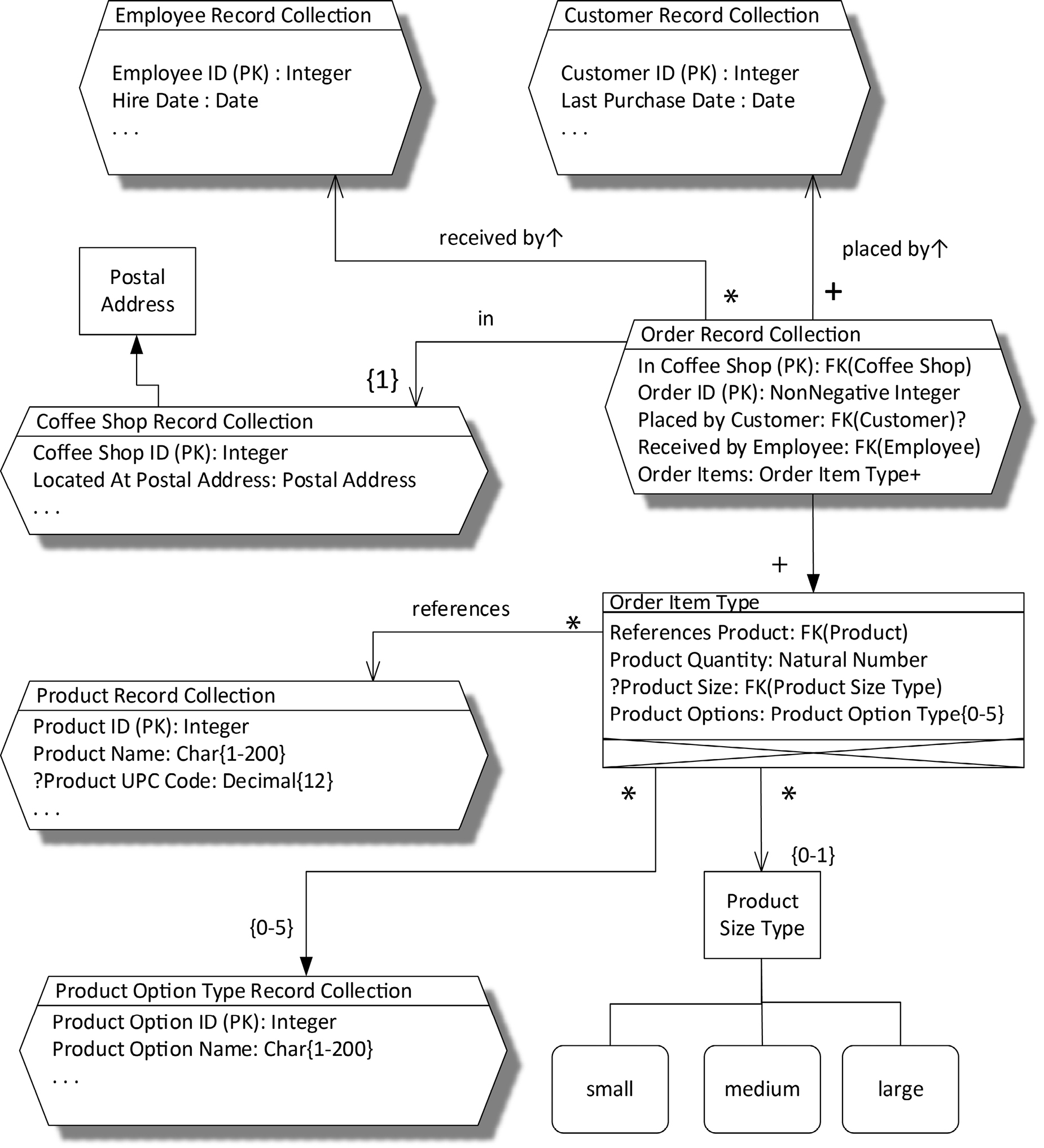

Let’s look first at where commerce begins in a coffee shop. A customer walks in, walks up to the counter, and places an order by speaking. The order could be as simple as, “Black coffee to go.” It could be as complicated as, “I’d like two lattes: one small and one medium; a large hot chocolate with no whipped cream; and a bag of French-roast coffee. Could you grind the coffee for me, please?” This indicates the need for a data design exploding with possibilities. Let’s analyze. Figure 18-1 is a COMN model of some of the important things in the business that we must understand before we can begin to design data to represent these things. Some of these are objects and some are concepts.

Figure 18-1. Real-World Entity Types in the COMN Coffee Shop

We saw back in chapter 13 that a customer is more specifically described as a person playing the role of customer. It was important to spell that out in chapter 13 so that we could understand how roles work, but now we’ll abbreviate the name of that same real-world class, a subtype of the Person class, to merely Customer. The rectangle representing the set of customers gets a bold solid outline, because persons are real-world physical objects. The class of employee—persons playing the role of employee—is similarly represented as a rectangle with a bold solid outline.

A customer speaks, and an order is expressed. The order did not exist as a stable set of physical objects that we could observe. It existed first in the mind of the customer, then briefly as sound waves vibrating in the air, and finally the order existed in the mind of the employee working at the counter. The order is a real-world concept that is shared ever so briefly between customer and employee. To reflect this, we draw the type of orders as a bold, dashed outline.

A customer places an order. We annotate the relationship line from Customer to Order with the verb “places”. Since this can be read correctly in a left-to-right direction, we don’t include an arrow to indicate reading direction, although it would be not wrong to do so. Since Order is conceptual, its relationship to Customer is also conceptual, so the relationship line is drawn dashed. A particular customer may, at different times, place many orders. However, we don’t consider a person a customer until she places at least one order. So we show a plus sign on the Customer to Order relationship line, next to the Order type, to indicate that the multiplicity of the relationship from Customer to Order is 1 or more. A particular order cannot be given by more than one customer, so we don’t indicate multiplicity at the other end of the line. This indicates by default that an Order is placed by exactly one Customer.

A particular employee may, at different times, receive many orders. We have placed an asterisk on the Employee-to-Order relationship line, next to the Order type, to indicate this. Since an order is received by only one employee at a time, we don’t indicate multiplicity at the other end of the line. This is in keeping with a business rule that any particular order is the responsibility of exactly one employee.

The order mentioned products. All of our coffee shop’s products are physical objects, so we represent the class of products as a rectangle with a bold, solid outline. An order must mention at least one product, so the Order-to-Product relationship line has a plus sign at the Product end to indicate a multiplicity of one or more. Since any product can be referenced by any number of orders, including none (either because the product is being offered for the first time or is a total failure), there is an asterisk at the Order end of the line.

Each order must be placed within a coffee shop, so there is a Coffee Shop real-world class shown, and the multiplicity of the relationship from Order to Coffee Shop is exactly one, which is indicated by default in the absence of any explicit notation at the Coffee Shop end of the relationship line. In the reverse direction, there can be any number of orders placed within a given coffee shop, including none if the coffee shop just opened. Therefore there is an asterisk at the Order end of the same relationship line.

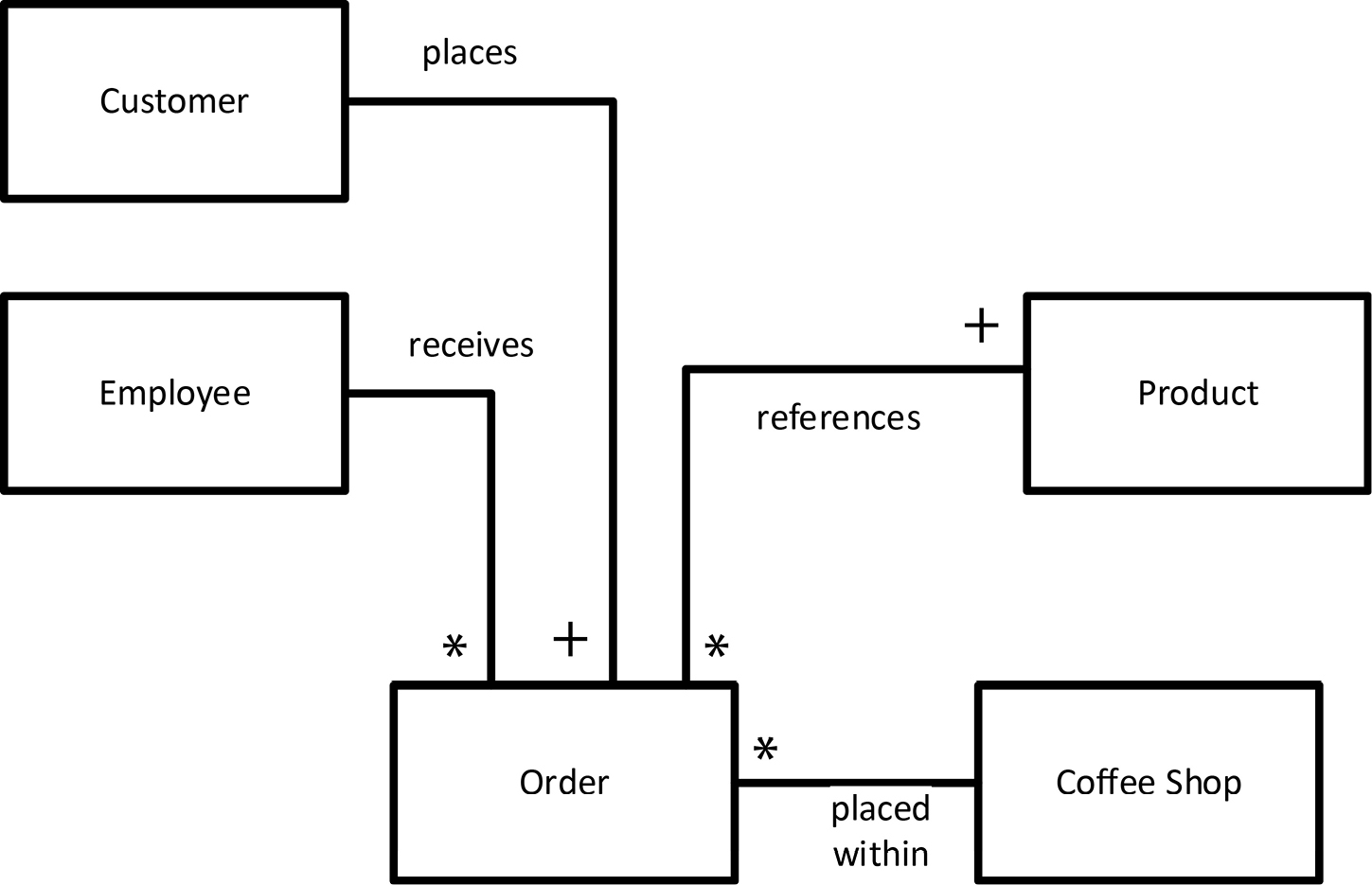

As the example orders above indicated, each product mentioned in an order can get pretty complicated, with sizes, flavors, and optional ingredients. There can be requests for processing products before delivery, such as a request to grind whole-bean coffee. Figure 18-2 shows a fraction of the product offerings. This diagram illustrates how straightforward it is for COMN to show the composition of real-world objects. Each object class that is a subtype of the Product class—indicated by an unadorned line connecting the class to the exclusive subtype pentagon—is the class of a product that is sold directly to a customer. Some of these products are also blended (double arrowhead) into other products. For example, espresso is sold as a product, but is also blended into cappuccino and latte. Hot chocolate is a blend of cocoa mix and one of four different types of a milk-type ingredient; whipped cream can be optionally added on top (aggregated).

It’s important to note that, although Figure 18-2 clearly shows that there are three exclusive subtypes of bagged whole-bean coffee, we don’t show that the supertype is a product. Instead, each of the three subtypes is a product. It would not be wrong to show the supertype as a product, and then provide a means to indicate which type of bagged coffee the customer wanted. However, we’re thinking of the idea that each type of bagged coffee will have its own Universal Product Code (UPC) encoded in a bar code directly on the bag. We want to sell each type of bagged coffee as its own product, not as a subtype of some abstract supertype of product. Categorization is a process we humans do almost without thought, but it can get in the way of proper analysis and data design. We keep the supertype off to the side as a way to document that three of our products are bagged whole-bean coffee products, but we don’t force that vocabulary on our customers and coffee shop workers. Later on we might want to classify sales of bagged whole-bean coffee products together in a marketing analysis report, so the supertype might be useful later on—but not when we’re trying to understand how customers order products.

We are limited in this book to rather small diagrams. In a facilitated requirements-gathering session with business stakeholders, full-size models can be drawn on large whiteboards or large sheets of paper. Afterwards, these drawings can be entered into an electronic drawing tool that doesn’t have strict size limitations.

Figure 18-2. Coffee Shop Products

Logical Data Modeling: Designing the Data

In chapter 13 we documented our logical data design for tracking data about customers and employees, and connected it to the real-world classes of Coffee-Shop Person, Employee, and Customer. Let’s turn our attention to the order, which is a central part of our coffee shop business (and indeed, of any business).

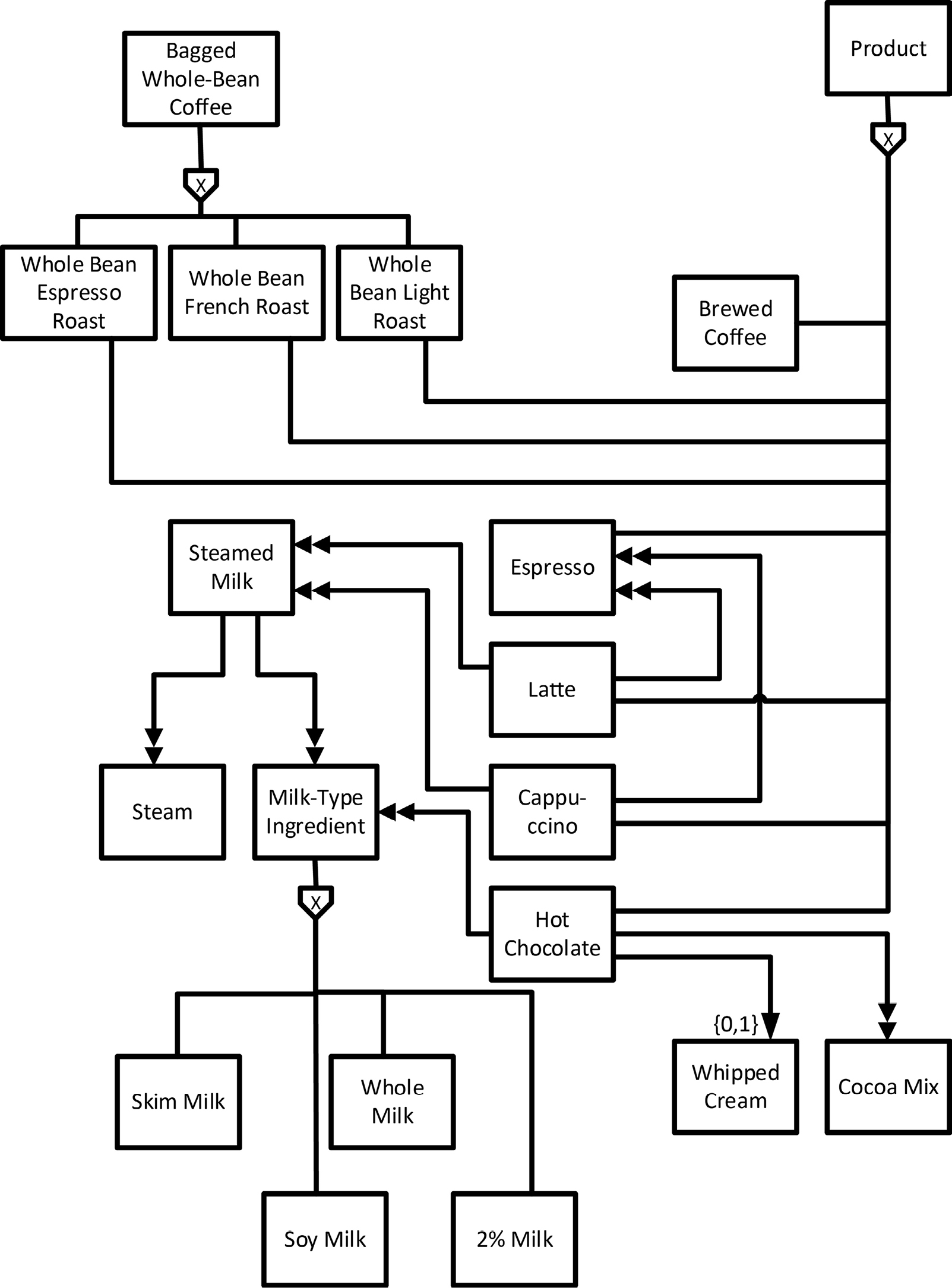

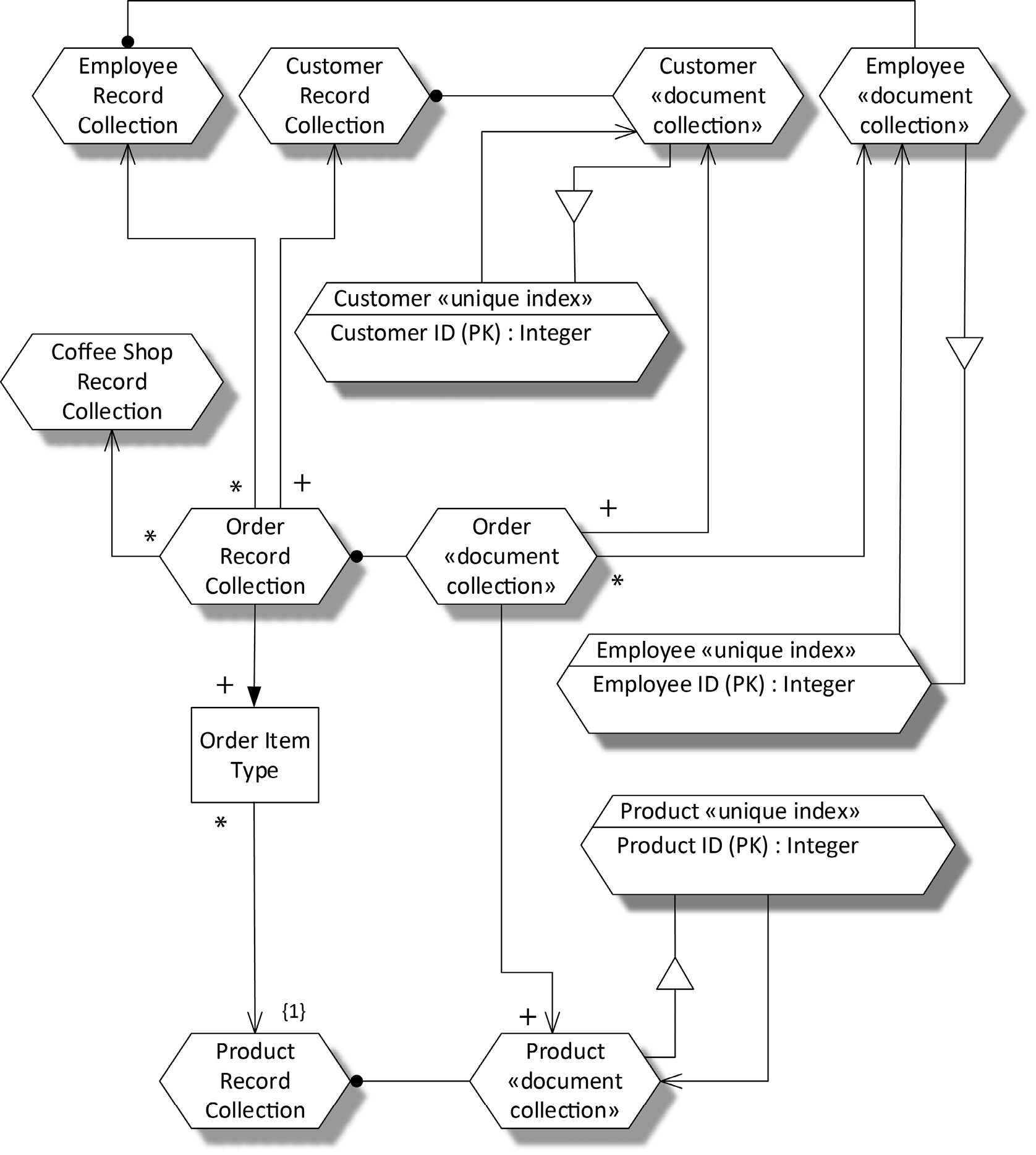

Figure 18-3 shows a logical data design for orders that references the real-world entity types and classes of Figure 18-1. We can carefully examine this model to ensure that every real-world entity type in Figure 18-1 is represented by some data in Figure 18-3, and that the relationship multiplicities given in Figure 18-1 are able to be represented by the corresponding data types. Let’s see how this works.

Each relationship line—each line with a solid circle at one end—shows a one-to-one relationship from some logical record collection to the real-world type or class it represents. For the most part, the relationships between the record collections and the real-world types that they represent are parallel. But it’s a little more complicated with the order record collection. In the real world, an order references one or more products. However, in our data design an order does not represent products directly. Instead, we see that an order record collection is composed of one or more order items, and each order item references exactly one product in the product record collection. So the multiplicities of the relationship from order to product are preserved in the data: one order has one or more order items, and each order item references a product, so one order (indirectly) references one or more products. Thus, the multiplicities in the real-world model of the entity types in the business are preserved in our logical data model.

The relationship line from the Order data record collection to the Order Item data type indicates that an Order is composed of one or more Order Items. The multiplicity in the reverse direction says that an Order Item cannot stand alone; it must always be related to an order.

Figure 18-3. Coffee Shop Order

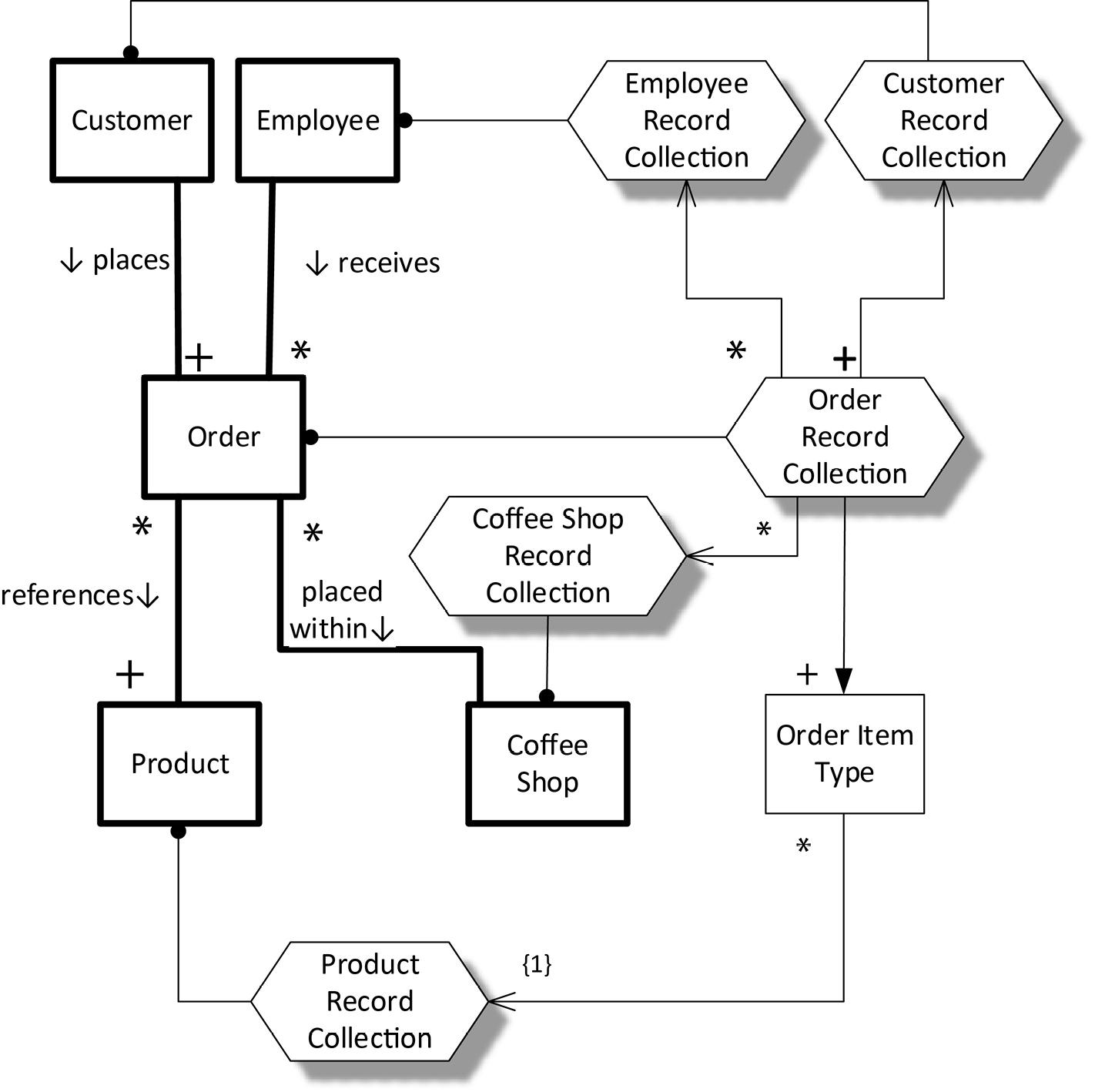

So far, so good. However, we have a few gaps. We have not yet decided how our order will identify our products, our employees, and our customers. We don’t have a means for identifying the coffee shop within which each order is placed. Identification is an issue centered mostly in data. We’re going to need more space in our diagram to develop our identification schemes. Since we’ve confirmed that our data model accurately represents the real world, in Figure 18-4 we’ve dropped the real entity types, and redrawn just the logical record collection hexagons and logical types of Figure 18-3 in the three-section form. This gives us the room we need to show the components of the records in the collections.

This diagram will illustrate the significant difference in a logical data design between composition and reference. An order is composed of order items, but merely references a customer, an employee, and a coffee shop. What’s the difference here?

Data we can’t identify separately can only exist as a component of some other data. In our data model we’ve decided that we must be able to reference data about employees, customers, products, orders, and coffee shops, because, in the real world, they all stand apart from each other. For one instance of data to reference another instance of data, it must have some value by which to identify the referenced data. From relational theory we know that the data attribute or attributes of some data record that distinguish it from all other data records in a set are its key, and that the value of a key is an identifier of a particular record in that set. This is a true statement whether the data in questions is stored in tables, in graph nodes, in documents, or in some other form. Relational theory is not limited to describing the storage of data in tables. In fact, we need to understand when we need keys in our data before we get to the question of how we’ll store the data.

So, in order for us to enable an Order to reference a customer, an employee, and a coffee shop, we must have keys for the three corresponding record collections. They are indicated in each record collection rectangle as components with a (PK) suffix. “PK” stands for primary key. A composite data type may have more than one key. Each additional key is identified by “AK” for alternate key, and can be numbered, as in AK1, AK2, etc. No alternate keys are used in this design.

We also want to be able to reference orders by some kind of identifier. In a busy coffee shop, employees might need to communicate to each other about which order they are working on. And since we plan for the business to grow, we know we’re going to want to analyze order data that’s been collected across many coffee shops and many days. So orders need keys, too. The key for the Order data type is particularly interesting. It is composed of two components (two data attributes). We call such a key a composite (or compound) key. A key with a single data attribute is a simple key. Since an order is always placed within a single coffee shop, we have designed orders to be identified by a simple integer sequence, Order ID, but qualified by the Coffee Shop ID—the data attribute playing the role of describing In (which) Coffee Shop the order was placed. This design allows a database in each coffee shop to assign key values—identifiers—to orders that don’t overlap with other coffee shops’ key values, simply because each coffee shop has its own unique Coffee Shop ID.

Figure 18-4. Coffee Shop Order Data Types with Components

An order’s In Coffee Shop data attribute has an interesting type, FK(Coffee Shop). “FK” stands for foreign key. We learned in chapter 16 that a foreign key constraint defines a subtype. The type of the In Coffee Shop data attribute is the set of all values which are key values of the Coffee Shop record set. We can see that the primary key of the Coffee Shop data type is the data attribute Coffee Shop ID, which has a type Integer. Therefore, we know that Order’s In Coffee Shop supertype is Integer. The FK(Coffee Shop) notation is much more informative than a mere “Integer”. Order’s key is therefore dependent on Coffee Shop’s key.

Each order also references the Employee Record Collection and the Customer Record Collection using foreign keys. But the type of the data attribute Placed by Customer—the foreign key—is followed by a question mark. When a data attribute’s type is followed by a question mark, this means that it is possible that, at the time a record is written, the value for this data attribute might not be known. There is no question that every order is placed by a customer—there is no question mark before the data attribute’s name—but we are well aware that we don’t always know the identity of each customer, and that’s OK. We’ll record the identities of those customers who have signed up for our frequent buyer program, but for the rest we’ll just leave the customer ID value as “unknown”.

“Unknown” is completely different from “optional”, which we’ll see is used in the order item record collection and elsewhere.

Product Quantity is simply a natural number. A natural number is a counting number (1, 2, 3, . . .) and so is always greater than zero. It doesn’t make sense to have an order item for zero products. By choosing a natural number type rather than a rational number type, we disallow fractional quantities of products. A customer can’t order half a cup of coffee.

It would be so tempting to aggregate Product Size Type directly into Order Item Type, as it appears on the surface that nothing could be simpler than indicating whether a product size ordered is small, medium, or large. However, we’re thinking about our business expanding globally. As soon as we expand into a multi-lingual market such as Canada, we will need to support expressing the same product sizes in multiple languages; for example, petit, médium, and grand. Therefore we’ve chosen for Order Item Type to reference Product Size Type, so that we can look up the appropriate language in which to express size to the customer. The Product Size component is preceded by a question mark, meaning that it’s optional. Size does not apply to every type of product. As explained above, an optional data attribute, indicated by a question mark preceding its name, is not the same as a potentially unknown, indicated by a question mark following its type. If size does apply to a product, we must know which size the customer selects.

Our design allows for up to five options to be specified as values of the Product Option Type. For the sake of brevity, we’ve omitted the design for data about product options. As with product size data, we want to reference product option data so that we can support multiple languages.

The designs for Employee Record Collection and Customer Record Collection were described in chapter 13. We have two remaining record collection designs to look at, namely Coffee Shop Record Collection and Product Record Collection.

Each coffee shop will be identified by a simple natural number, which carries no particular meaning, other than indirectly through the fact that the first coffee shop we open will be coffee shop #1. The most distinct fact about a coffee shop that we’ll record is its postal address. We will aggregate the Postal Address type directly into each coffee shop record, since we don’t need to make sure that coffee shop postal addresses can stand alone. Therefore, no key is needed for coffee shop postal addresses. We might make a different choice for customer postal addresses. For example, we might want to know when two customers share an address, as that might indicate that they are part of the same household, and we might want to combine marketing efforts to all customers in the same household. We will not explore such a design here. The ellipsis indicates that there are other coffee shop record components that are not shown. These could include such things as the date on which the coffee shop was opened, the date on which it was closed if it is no longer in operation, etc.

Products will also be identified by simple, meaningless natural numbers. A product record optionally carries a Universal Product Code (UPC), which is that number associated with a scannable bar code. Some products, such as bagged coffee, will be marked with UPCs, but it doesn’t make sense to have a UPC on a product that can’t be scanned, such as a cup of coffee. As with Product Size Type, we want to be able to refer to our products with language-specific names, so we’ve separated product names into their own record collection. The primary key for Product Name Record Collection is a composite key. One data attribute of the key is a foreign key to the Product Record Collection. The other data attribute has the ISO 639-1 Code as its type. That code is the international standard for referencing human languages. The two data attributes together identify a language-specific name for a product.

In summary, we can see that one of the most important issues driving logical data design is whether a given type of data needs to be able to be referenced separately from other data or can be incorporated into other data without its own key.

Physical Data Modeling: Designing the Implementation

We’ve reviewed the logical data model with our business stakeholders, and we’re reasonably certain that our data as designed will adequately represent all of the entities involved in daily coffee shop operations. Now it’s time to choose a physical representation for the data.

It is at the point of physical data design that performance considerations come in. We want to make sure that access to the data is efficient in the contexts where it’s used. We are going to think about two usage contexts. The first usage is in coffee shop operations, where orders must be able to be captured quickly. Fast update is a concern. The second usage is in marketing analytics, where we collect orders from coffee shops throughout our empire, and want to look across all of the data to be able to compare such things as which kinds of products sell best in which regions and which are the busiest times of day.

For coffee shop operations, the most straightforward design is to represent an order, together with its items, as a single document. We’ll choose a NoSQL document database for our in-coffee-shop operational database management system. That means that each of the independent logical record collections of Figure 18-4 will be represented as a document collection. Figure 18-5 shows the physical design.

The physical record collections depicted here have type names given in guillemets (« »). A type name in guillemets in a record collection indicates the type of the instance. For example, the Customer «document collection» is an instance of a DBMS document collection named Customer. In a physical data model targeting a specific DBMS, the DBMS’s type name would be used within the guillemets.

The modeling of indexes deserves special attention. The Customer «unique index» is an instance of a DBMS unique index named customer. The extension symbol with its narrow side towards the index expresses the fact that the index contains a projection of the document collection—a vertical slice, so to speak—where only certain data attributes of each document are included in the index.

Figure 18-5. Coffee Shop Document Database

The Customer «unique index» symbol shows that only the Customer ID is included. This use of projection of a record collection expresses physical data copying. Fortunately, the DBMS takes care for us that the copied data in the index always stays in sync with the original data in the document collection. The non-dashed arrow pointing to the Customer «document collection» indicates that each record in the index has a one-to-one physical relationship to a record in the document collection. If an index were non-unique, then it would have a plus sign at the document collection end of the arrow, showing that a single index entry might reference multiple records, but would always reference at least one.

Most, but not all, of the logical record collections and types are represented by document collections. We intend each coffee shop to have its own copy of the database, and we don’t see the need to store data about all the other coffee shops in each coffee shop’s database, so there’s no document collection representing the coffee shop record collection. The Order Item Type is aggregated into the Order record collection, so it doesn’t need a separate representation by its own document collection. All the rest of our logical record collections are represented by document collections.

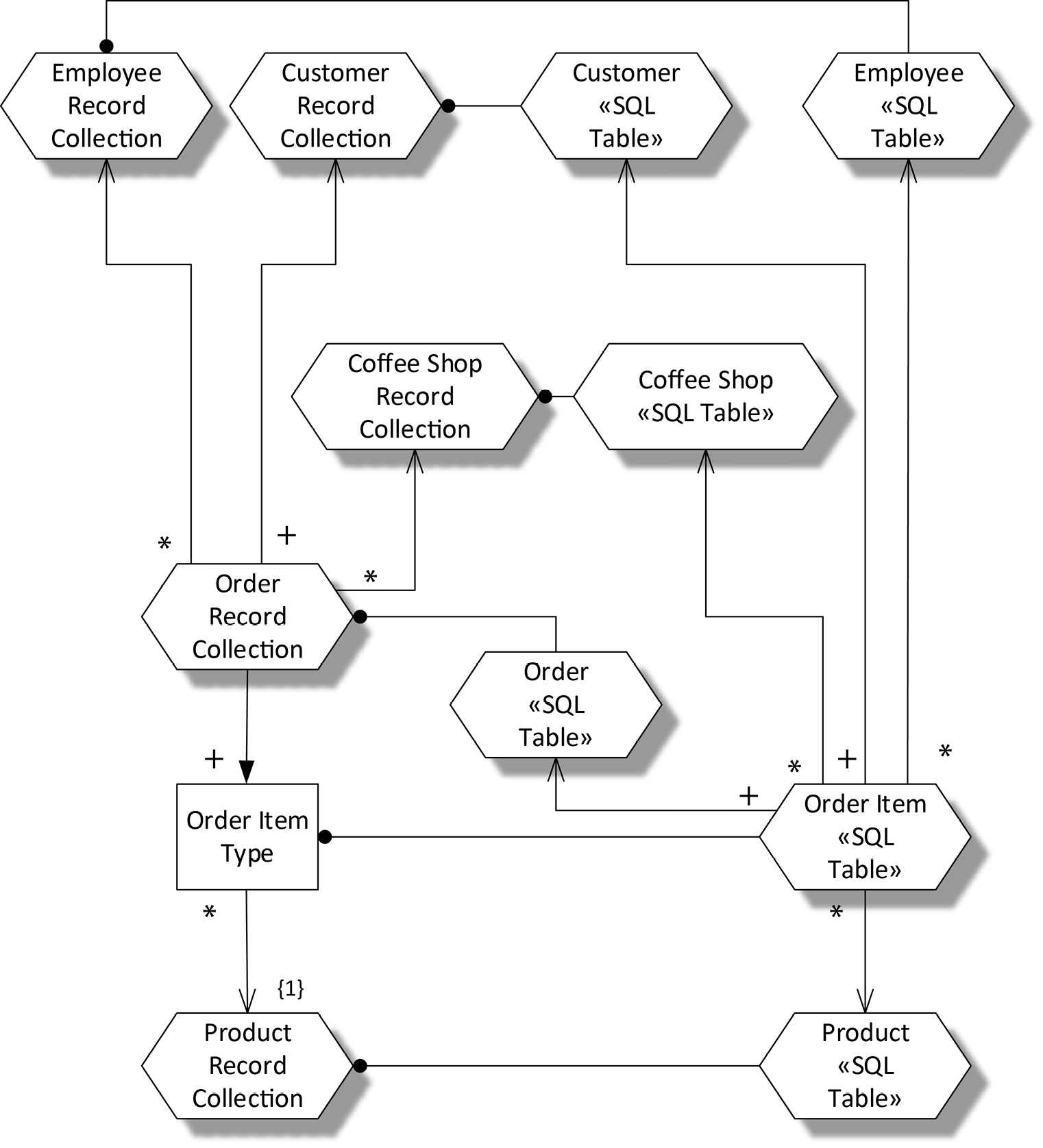

The unique indexes on the primary keys of the document collections enable fast lookup of customers, employees, and products, which is all we need for fast order entry in the shop. But when we want to analyze this data later, we will need much more flexible navigation through the data. Figure 18-6 shows a data warehouse designed to represent the same logical data with an entirely different physical structure. This is a dimensional warehouse design to be implemented in a SQL database. In this design, the Order Item «SQL Table» is the central fact table, and there are separate tables for the Customer, Employee, Product, Order, and Coffee Shop dimensions. Unlike our operational database, Coffee Shop data is now represented, as we’re collecting data in our warehouse from all of our coffee shops.

Following the physical data modeling pattern presented for the coffee shop operational database design, we can use this diagram to confirm that we’ve represented multiplicities correctly, then create another diagram that drops the logical data and expands the tables to show their components. We can show unique and non-unique indexes on the tables. Following traditional techniques for dimensional data warehouse modeling, we can add additional fact tables and additional dimensions.

Using the expressive Concept and Object Modeling Notation, we can model the types of entities—types of concepts and types of objects—that are present in a problem domain, model at a logical level the data we will use to identify and describe those types of entities, and model at a physical level how we will arrange our representations of that data.

Figure 18-6. The Order Item Fact Table in the Coffee Shop Data Warehouse

We can model how the data will represent the real-world entities in the problem domain, and confirm at every stage of modeling that we have preserved the same relationships in the data as exist in the real-world entities. We can take the physical model to a level of detail where implementation in a NOSQL database and/or a SQL database can be mechanically derived from the physical model, and therefore something that could be fully automated. COMN enables model-driven development from the identification of problem-space entity types all the way through to multiple physical implementations of the same data.