|

|

While working at Control Data Corporation in the Netherlands in the early 1970s, Dutch computer scientist Sjir Nijssen developed what came to be known as the Natural-language Information Analysis Methodology, or NIAM, which incorporates fact-based modeling. The unique central aspect of fact-based modeling is an approach where modeling starts with statements of facts about a problem domain, provided by domain experts in their own language. The data analyst deduces patterns from these fact statements called fact types. A fact type is a statement in natural language that has one or more blanks or “roles” to be filled in. The roles are played either by object types or by label types.

Several very similar graphical notations, and associated methodologies, have been developed to support fact-based modeling, including Object Role Modeling (ORM) and Fully Communication-Oriented Information Modeling (FCO-IM). The examples in this section were drawn in ORM notation using the NORMA tool [NORMA] and Microsoft Visual Studio.

Facts and Relationships

Fact-based modeling starts with statements of fact in the problem domain. Here are some such statements.

Sam Houston works at 123 East Main Street, Dallas, Texas 75208.

Dolly Doolittle works at 123 East Main Street, Dallas, Texas 75208.

Sam Houston lives at 456 Pine Street, Fort Worth, Texas 76104.

Dolly Doolittle lives at 789 Elm Street, Fort Worth, Texas 76104.

Sam Houston’s mobile phone number is 214-555-1212.

Sam Houston’s FAX phone number is 214-555-9999.

Dolly Doolittle’s home phone number is 214-555-1234.

A fact-based modeler would recognize the patterns in these statements and reduce them to the following fact types:

. . . works at . . .

. . . lives at . . .

. . . has mobile phone number . . .

. . . has FAX phone number . . .

. . . has home phone number . . .

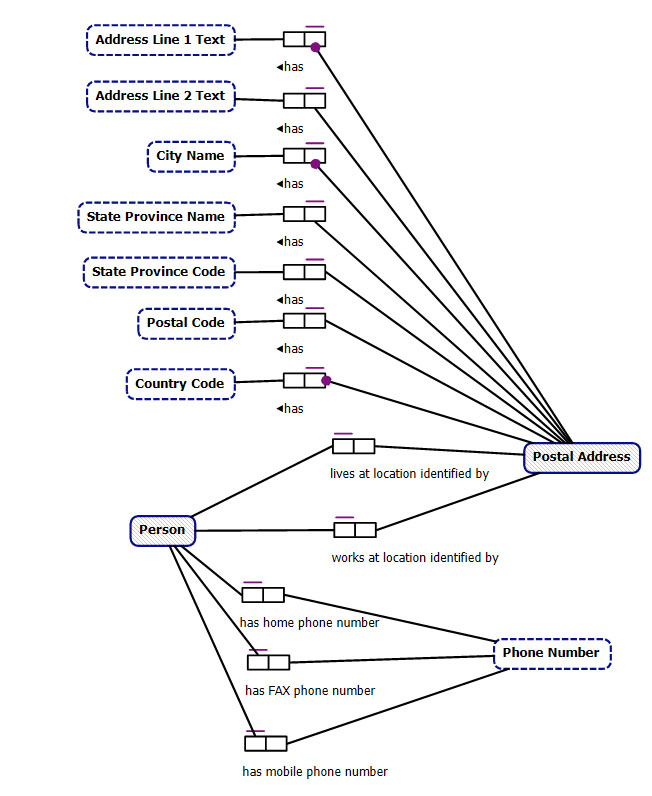

This would lead to the model shown in Figure 7-1 below.

Each rounded rectangle represents what is called either an object type or a value type. An object type typically represents a type of real-world object or concept in the problem domain. A value type represents something that is expressed entirely through a symbol or string of symbols—in other words, numbers and/or text.

Fact-based modeling notations are somewhat unique in the universe of data modeling notations in that they do not support the direct expression of data attributes within the symbol for an object type. Attributes of an object type are shown via relationships to object types or value types. This approach can be seen with the definition of the Postal Address type and its relationships to its component parts. This approach also leads to relational database designs that are already fully normalized (in fact, are in fifth-normal form), making the normalization process that is normally part of logical database design nothing more than a bad memory.

The rounded rectangle representing a Person type is shaded because no “reference mode” has been established for it. A reference mode is a manner in which some value refers to an object. If we were further along in our design, we would have chosen some symbolic identifier type for Person, and shown that as a value type in a dashed rounded rectangle.

Similarly, the Postal Address type is shaded. In truth, the aggregate of the postal address’s parts provide the postal address itself, but given the way this model is drawn, an additional value type will be needed to enable reference to an individual postal address. This is desirable in any case, from a database design point of view, for efficient access to postal addresses.

A distinct advantage of fact-based modeling is that it is relatively straightforward to verbalize relationships in natural language; so straightforward, in fact, that modeling tools can do it. This is a wonderful tool for confirming that the model expresses the intended semantics. For example, the relationship from Person to Postal Address via “works at location identified by” is verbalized by the NORMA tool as follows:

Person works at location identified by Postal Address.

Each Person works at location identified by at most one Postal Address.

It is possible that more than one Person works at location identified by the same Postal Address.

Not shown in Figure 7-1 are additional constraints that can be imposed on any of the relationships in a model. Fact-based modeling has a full set of constraint symbols that allow the constraints of reality and of business requirements to be expressed. This captures more meaning in the model and increases the likelihood that the implementation will meet requirements.

Limitations of Fact-Based Modeling

If one wishes to connect one’s data model to the real world, it can be very important to represent, not only real-world entity types, but also particular instances of those types—particular entities—and relationships to data about those instances.

For instance, a model of the legal system of the United States would need to include an entity type called “Court”, but may need to represent the Supreme Court, which is an entity and not an entity type, since it is a very special one-of-a-kind court. The model would need to show relationships between the Court object type and the Supreme Court—but it can’t. A fact-based model can represent “Court” but not “the Supreme Court”. Such individual entity instances are left implicit in a model, and there is an unsatisfied need to show that objects of a certain type always connect to data about those implicit entity instances.

Incompleteness

The latest edition of Halpin and Morgan’s book [Halpin 2008] positions ORM as a tool that should be used to ensure that a conceptual model is valid before proceeding to use E-R modeling or UML modeling to express physical database design details. In this approach, the details of the mappings from ORM to the final database design can be lost between the models.

The FCO-IM book [Bakema 2002] does not recommend the use of other established modeling notations to express physical database schemas. Instead, the book illustrates relational schemas with sample tables and words. In both cases, the fact-based notations exclude the possibility of illustrating physical design details. This is deliberate, as a way to reduce the chance that physical database design considerations will enter into the data analysis phase of a project. It is certainly a problem if such a thing happens, but to prevent the possibility by making those very important physical design decisions inexpressible limits the value of the notation.

Fact-based modeling follows the observation from NIAM that we do not actually represent the real-world in our data, but rather representations of the real-world. COMN accepts this reality, but enables us to model exactly how those representations work. COMN also recognizes that our representations are ultimately realized in a computer as otherwise meaningless physical states of material objects. It is important to grasp this reality, and to be able to express the mapping of the meaningless physical states of material objects to things that have meaning. Thus, COMN supports the expression of physical design alongside conceptual and logical design. If a designer has allowed physical details to drift into conceptual and logical models, that will be apparent from COMN’s very different graphical notation for implementation details.

Tools such as NORMA (for ORM) and CaseTalk (for FCO-IM) enable the automatic generation of relational database schemas from conceptual models. This minimizes the need to graphically display the generated schema, but does not handle NoSQL databases. It also provides no means for a database designer to express physical design decisions graphically, nor to map them to the object types to which they relate in order to ensure a complete and correct implementation.

Difficulty

Fact-based modeling is a powerful technique for analysis, and its associated notations can capture requirements in about as complete a manner as possible. However, it has been found to be difficult to learn for data modelers, and difficult to read for business users. In my experience, business users find it much easier to relate to the record-oriented graphics of E-R notations and of the UML. Somewhat counter-balancing this difficulty is the availability of relationship verbalizations generated from the fact-based modeling tools, which are quite easy for business users to grasp.

Terminology

The terminology of fact-based modeling uses the terms object, object type, entity, entity type, value, and value type in important ways that cannot necessarily be deduced from the ordinary meanings of the words.

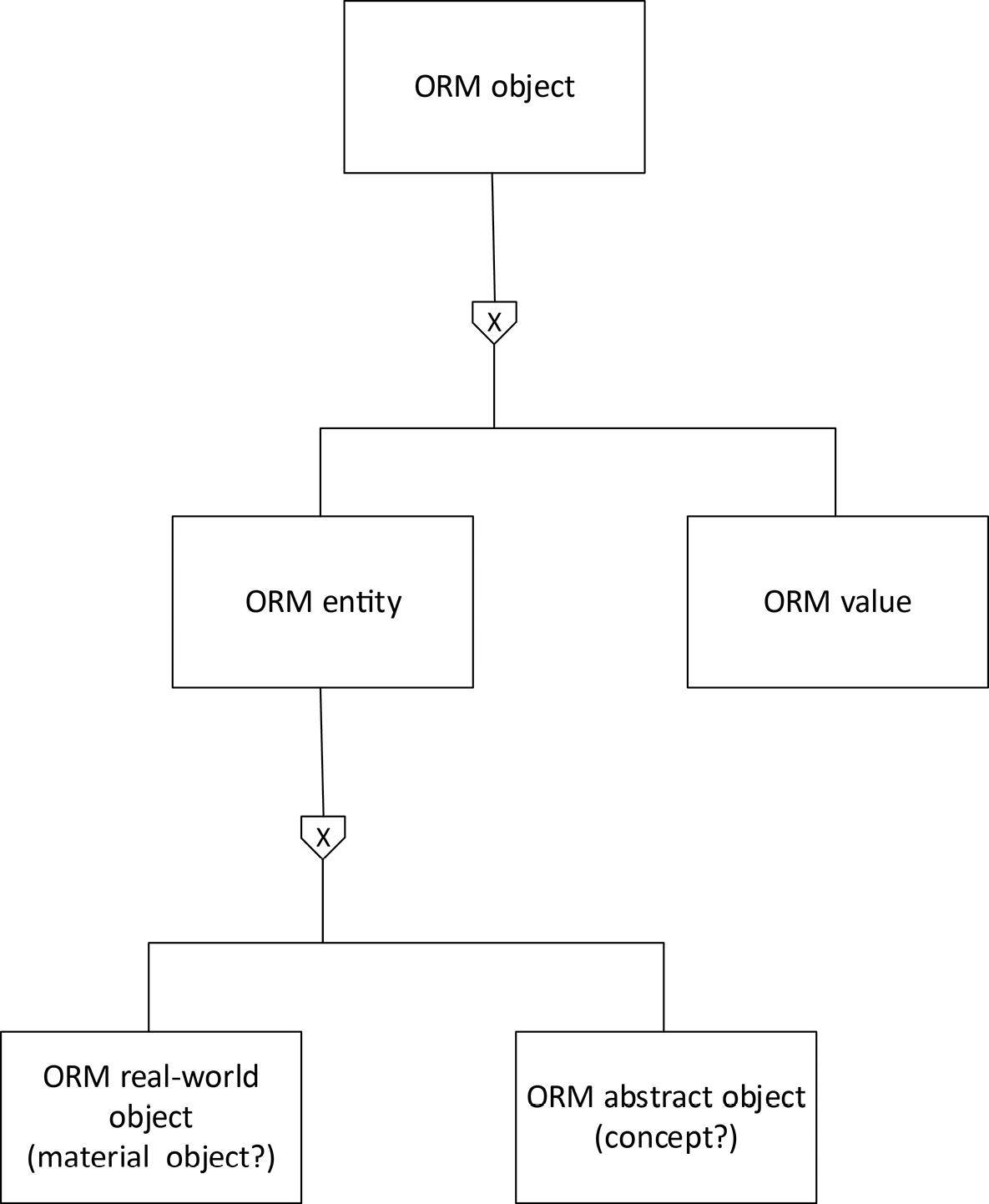

The most basic term in fact-based modeling is object, which means thing (the generic “entity” of English and of COMN). Objects come in two flavors: entities and values. An entity is either a “real object” (presumably meaning a material object and not to be confused with the “object” we started with above), or an “abstract object” (presumably meaning a concept, and again not to be confused with the “object” we started with above). A value is fully defined by the string of symbols that express it. So, for example, “123” is a value, and “abc” is a value. This terminology is expressed as a type hierarchy in COMN in Figure 7-2.

Figure 7-2. The Ontology of ORM in COMN Notation

There can be types of entities, types of values, and types of objects. As in COMN, a type designates a set. It is unclear whether an object type is a type of real or abstract object, or a type of generic object.

ORM has a special place for measures, which are quantities of some units; for example, centimeters or kilograms. Measures in COMN are discussed as special kinds of composite types in chapter 12.

The view of relationships and roles in fact-based modeling is very similar to the view in COMN. This should become evident as you read chapter 15 on relationships and roles.

Fact-Based Modeling Terms Mapped to COMN Terms

A mapping from fact-based modeling terms to the corresponding COMN terms is given in the table below. Where two COMN terms are given for a single fact-based modeling term, it indicates that the fact-based modeling term is ambiguous.

|

Fact-Based Modeling Term |

COMN Term |

|

object |

entity |

|

entity |

real-world object or concept |

|

value |

that which is fully represented by a symbol, or the symbol itself |

|

label |

identifier |

|

reference mode |

identifier type |

|

fact type |

relationship type |

|

role |

role |

|

predicate |

predicate |

|

Key Points

|

References

[NORMA] NORMA for Visual Studio. Available for download at https://www.ormfoundation.org/.

[Halpin 2008] Halpin, Terry and Tony Morgan. Information Modeling and Relational Databases, second edition. Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, 2008.

[Bakema 2002] Bakema, Guido, Jan Pietr Zwart, and Harm van der Lek. Fully Communication Oriented Information Modeling (FCO-IM). Netherlands: BCP Software, 2002.