|

|

Now that we’ve established that computers are composed of material objects, most of which have meaningless physical states, we need to find a way to express meaning. In this chapter we’ll learn how types provide meaning. When we have a good handle on types, we’ll realize that that’s where we focus our data analysis and logical data design efforts, and we’ll know how to express that in COMN.

Types in Programming and Databases

The term “type” began to be used in the earliest of so-called “high-level programming languages” in the 1950s in a way that was very different than its English meaning, which is related mostly to classification. “Type” was used as a way for a programmer to inform a compiler that a variable could take on any value in the set designated by the type, and simultaneously that a variable needed a certain amount of memory so that it could represent all the values of that set. So, for instance, in the days when 16 bits of memory were commonly used for storing numbers, a variable whose type was INTEGER required 16 bits of memory and could take on any value that could be represented using 16 bits—that is, any integer in the range from -32,768 to +32,767. A variable whose type was REAL required 32 bits of memory and could take on a much larger range of numbers that also included fractional digits; that is to say, digits to the right of the decimal point. (REAL was a misnomer, since such variables could not take on irrational real numbers such as pi or the square root of two; FLOATINGPOINT, meaning floating decimal point, would have been a better name for the type.) Thus, the name of the type designated the set of values the associated variable could take on, and additionally communicated a memory allocation requirement.

This notion of type naturally extended to database management systems (DBMSs), which came along about a decade after high-level programming languages were created. Each DBMS defines a fixed, relatively small set of “types” that describe what values can be represented in individual fields in a database. Since a DBMS usually uses a mass storage medium such as hard disk or flash memory, its types can be quite different than those supported in main memory by programming languages. Designers took advantage of the greater flexibility they had with mass storage than with main memory to define types differently than programming languages types, and incompatibilities between programming language types and DBMS data types were born.

Nowadays, the programming language type called int and the DBMS type called INTEGER are most likely to occupy 32 bits of memory or storage and are able to represent numbers in the range of negative two billion to positive two billion, while the programming language type called double and the DBMS type called DOUBLE PRECISION are most likely to occupy 64 bits of storage and are able to represent a large range of floating-point rational numbers. Other types exist to handle the expression and storage of such things as character strings and dates.

What Does a Type Tell Us?

Let’s look closely at what a traditional database or programming language type communicates. A DBMS uses a data type and a high-level language compiler uses a variable’s type for the same two purposes:

- a logical purpose: A traditional type specifies the possible values a variable or field can take on. This is extremely valuable in helping to ensure the correctness of programs and data through a process called type checking. A compiler or DBMS either checks when compiling a program, or generates executable code to check when the program is running, to ensure that only values in a variable’s type’s range are assigned to the variable. For example, a DBMS will refuse to allow a program to store the character “X” in a field whose type is DOUBLE PRECISION. Similarly, when compiling code to assign the value of a variable of type DOUBLE PRECISION to a variable of type INTEGER, a compiler will generate code to report an error if the value of the variable of type DOUBLE PRECISION exceeds the range of values that can be represented by a variable of type INTEGER.

- a physical purpose: A traditional type specifies the memory or storage required for a variable or data item. A compiler or DBMS ensures that the proper amount of computer memory is allocated so that it can represent all of the values in the type’s range. In the examples above, 32 bits (four bytes) of storage is typically allocated to a variable whose type is INTEGER, while 64 bits (eight bytes) of storage is typically allocated to a variable whose type is DOUBLE PRECISION.

Thus, while the English word “type” can mean a classification, in DBMS and high-level programming language terminology the word “type” means a constraint on values and a specification of the storage required for any variable declared to be using that type. But the two meanings still have something important in common: both designate a set, either implicitly or explicitly. Type as classification designates the set of things that belong to the classification. Likewise, the DBMS or programming language type designates the set of values that may be represented in memory or storage. This is consistent with what we said in chapter 4, that types designate sets.

Classes in Object-Oriented Software

As mentioned above, in ordinary English the words “type” and “class” are synonyms. However, with the advent of object-oriented languages in the late 1960s [Holmevik 1994], the world of IT gradually adopted the term “class” to mean something different than “type”. “Type” for the most part retained its early meaning of set of values plus storage specification. Additionally, because the term “type” was adopted early in the history of programming language development, types were generally quite simple or “primitive”, specifying little more than sets of letters and/or numbers. In fact, in some contexts the terms “primitive type” and “data type” are considered synonyms, and the adjective “primitive” considered unnecessary. In contrast, the “class” of object-oriented programming is associated with the enablement of programmers to define structures of arbitrary complexity, leading to a terminology that considers “classes” to be more powerful in their descriptive capabilities than mere “[primitive/data] types”. Both class and type retained their use as specifying storage in addition to designating a set. In programming and database development (though not in data modeling), both terms lost their meaning related to classification.

Unfortunately, this vocabulary leaves the programmer or database developer with several problems. One problem is that it becomes difficult for the analyst or designer to talk of types and classes of things in the real world without confusing those terms with the very different meanings of “type” and “class” in data and software. Modeling the real world, and translating those models into their representations in software and data, can get quite confusing. Making this worse is the fact that the fields of semantics and philosophy use the terms “type” and “class” differently than their ordinary English meanings and differently than their programming-language and DBMS meanings.

Another problem is that there is no substantial difference between the programming / DBMS meanings of “type” and “class” other than degree of complexity. We are left with two words for things that appear, at least on the surface, to be very similar.

Separating Type and Class

It turns out that it can be very helpful to separate the two functions of a programming language or DBMS type, namely the specification of a constraint on values and the specification of memory or storage requirements. This separation preserves both terms as very useful, but by clearly focusing each term on only one meaning, thought and communication about data, semantics, and software becomes much clearer and more powerful.

As we have seen in chapter 10, the term “class”, when properly understood, can be used to describe the composition and “behavior” of computer objects—that is, software objects and hardware objects—all the way down to the level of the hardware objects of which computers are composed. We will preserve this use of “class”.

Classes therefore can be used to specify storage allocation requirements. We will remove this aspect of types, and limit types to designating sets of things—that is, sets of concepts or objects. Types become our means to specify the values that are to be represented in storage, without any presuppositions about how much storage will be needed or how those representations will be constructed.

A class indicates the meaning of the physical states of its objects by declaring that it represents a type. A class represents a type if its objects are designed so that each state of an object represents a member of the set designated by the type.

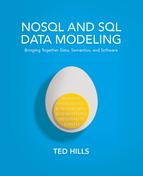

That’s a mouthful, and a lot to remember, so let’s draw that in COMN. See Figure 11-1. Starting at the top of the drawing, we see two rectangles with a line connecting them. The solid rectangle on the right represents a class, and the dashed rectangle on the left represents a type. In COMN, classes are drawn as rectangles using solid lines, in an allusion to the solidity of matter, while types are drawn as rectangles using dashed lines, to indicate that they are conceptual, not physical.

Figure 11-1. Representation Relationships (The relationship labels are unnecessary.)

The line from class to type with the solid ball on one end expresses the assertion that this class represents this type. The small arrow to the left of the word “represents” indicates the reading direction. Since a line with a ball on the end always indicates a representation relationship in COMN, the word “represents” isn’t actually necessary. It’s just included in this diagram to help you remember what that kind of line means. Because the representation relationship is conceptual and not physical, it is drawn with a dashed line.

In the middle of the diagram we have two hexagons also connected with a representation relationship. We saw the solid hexagon in chapter 10. It represents a software object. The dashed hexagon represents a variable in a program or a field declaration (perhaps a table column, perhaps a document component) in a database. This diagram says that the object represents the variable. In other words, something solid and material, capable of having multiple physical states, represents something symbolic that is declared to be able to take on any of the values of its type. It is usually a compiler or DBMS that allocates an object to represent the variable or field specified symbolically by a programmer or database designer.

At the bottom of this diagram we have two rounded rectangles. The solid-outline rounded rectangle on the right represents a physical state of the object above it. The dashed-outline rounded rectangle on the left represents a value of the type, to which the variable above it is bound. This, finally, shows the mapping of an otherwise meaningless physical state to a value of a type. The declaration that the class at the top represents the type at the top is only valid if in fact every possible state of any of the class’s objects represents a value of the type.

By this means, the representation mapping expresses the meaning of the states of otherwise meaningless objects.

The unadorned lines in this figure (all of which happen to be vertical) have meanings based on the symbols they connect:

- The line from object to class indicates that the object is an instance of the class.

- The line from object to state indicates that the object may have the state.

- The line from variable to type indicates that the variable has the type.

- The line from variable to value indicates that the variable is bound to the value.

- The line on the far left, from type to value, indicates that the type includes the value.

Again, in the case of the unadorned lines, the words are not needed, as there is only one possible interpretation for these lines. Lines in COMN drawings either have a meaning given by arrowheads and tails, such as the ball at the head of the “represents” line, have a meaning given by what they connect, such as the unadorned lines connecting dissimilar symbols, or have a meaning given explicitly in words and other symbols. We will see examples of these later.

Connecting lines are dashed or solid based on whether the relationships they represent are conceptual (dashed) or physical (solid). Any relationship involving something conceptual must itself be conceptual. Relationships between physical things may be physical, but may also be merely conceptual.

Computer objects are physical, and their states are physical phenomena, but descriptions of computer objects—that is, software and DBMS classes—are conceptual. Nonetheless, we draw classes in solid outline to indicate that they are descriptions of physical things.

What is gained by the separation of type and class? Exactly what the world of computer science has been striving for decades, through modeling notations, high-level programming languages, data languages, virtual machines, and other means that have never quite achieved these goals:

- Specification of the “what” independent of the “how”: Existing modeling notations, programming languages, and data languages have tried to enable the expression of software and data requirements independent of particular computer architectures, but the fact that the most basic types assumed some particular representation meant they always failed. A virtual machine is not devoid of such assumptions: it simply specifies a particular set of representation assumptions independent of any real computer (even including the arbitrary choice of endian-ness). In contrast, COMN can truly describe the “what” in terms of types independently of any assumed virtual or real representations.

- Description of the “how” independent of the “what”: Classes can be used to describe the mechanisms and states of raw computer hardware before any meaning has been attached to those states. Most modeling notations and high-level programming languages cannot express ideas at this low level.

- Specification of the representation of requirements separately from specification of the requirements: Once a pure description of the “what” has been drawn in COMN, the design of the “how” can be completed by building up classes and objects from those available on the implementation platform, and those classes and objects can be mapped to the types in the requirements using representation mappings. Most existing notations and languages cannot express this mapping, either because they’ve tangled the concept of types with assumed representations and implementations, or they’ve prohibited the expression of implementation concerns, or (strangely but commonly) both.

Simple Types

We have seen how hardware objects are simple objects, having no components (from the point of view of software), and how we will rarely deal with hardware objects directly. We leave that difficult and tedious work to compilers and DBMSs.

Not so with simple types. Database designers must deal with simple types, and composite types, throughout the analysis, design, and implementation phases of any project.

The implementers of DBMSs and programming languages have done us a great favor by creating large collections of so-called “types”—which we now think of as classes representing types—that name and describe particular implementations of representations of values. We can use these implementations to build our systems. But if, at analysis time, we ignore these implementations and focus only on specifying the sets of values to be represented—types in the COMN sense—we can specify our systems’ requirements—the “what”—without even a glance at what particular implementation systems provide for us. For example, if we need some variable to range between -1 and 100,000, we can specify that as a type, and defer until later the exact choice of an implementation of some class whose objects can represent just those values. We can also specify that type without recourse to the arbitrarily distinct idea of a so-called “domain” supported by some E-R modeling tools. These modeling tools need the concept of “domain” in addition to the concept of “type” because they’ve hard-wired “type” to the fixed set of mostly simple types provided by DBMS implementations. If, instead, types have nothing to do with implementations, then a type is a type is a type, whether it is directly supported by an implementation out of the box or will require some programming. The E-R modeling concept of “domain” is just redundant.

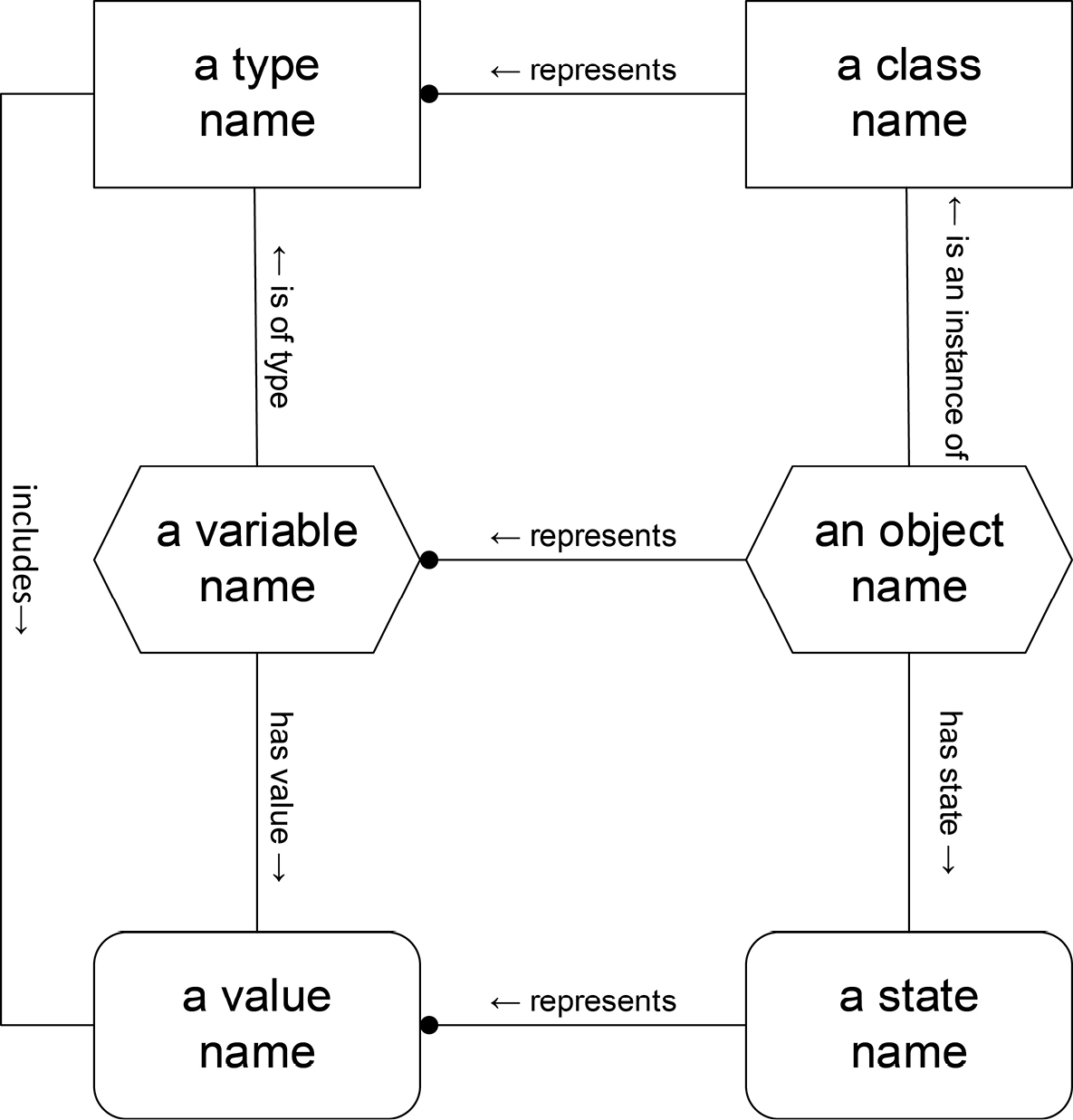

In addition to the simple type starter kits provided to us by DBMSs and programming languages, we often need to make up our own simple types. One of the most common of these is an enumeration. An enumeration is a type that is specified by listing the names of the members of the set it designates. Here are some example enumerations:

- account status: open, closed, suspended, abandoned

- organization type: corporation, government entity, non-profit

- order status: ordered, shipped, back-ordered, canceled

In general, enumerations have no components. Now, their representations do: the example enumerations listed above represent enumeration values with words and phrases which are composed of letters and punctuation. But what these representations represent have no components. For instance, an account status of “open” can’t be broken down into any constituent parts. Likewise, an order status of “shipped” has no components. Don’t confuse the value, which is simple, with information about what these values represent. For instance, we can learn of the date on which an account was opened, or the reason an order was canceled. But the enumerated values that these data are about, “open” and “canceled”, are simple values.

Figure 11-2 below shows a COMN diagram for account status. Such a drawing is most useful for enumerated types that designate relatively small and stable sets of values. Stable enumerated types of those sorts can be extremely important in a data design, as it enables distinct parts of a system to communicate with each other. For larger and/or more fluid enumerated types, the type names are often kept in a database table. (There are well documented standard techniques for managing such lists of reference values in databases.) For the more fluid enumerated types, a model will typically just show the type rectangle and omit the enumerated values.

The rectangles and rounded rectangles in Figure 11-2 are dashed because they represent concepts, and are in bold outline because they represent the concepts in the real world, not as expressed in data. The lines crossing through the shapes indicate that these are a simple type and simple values, having no components.

Figure 11-2. An Enumerated Type in COMN

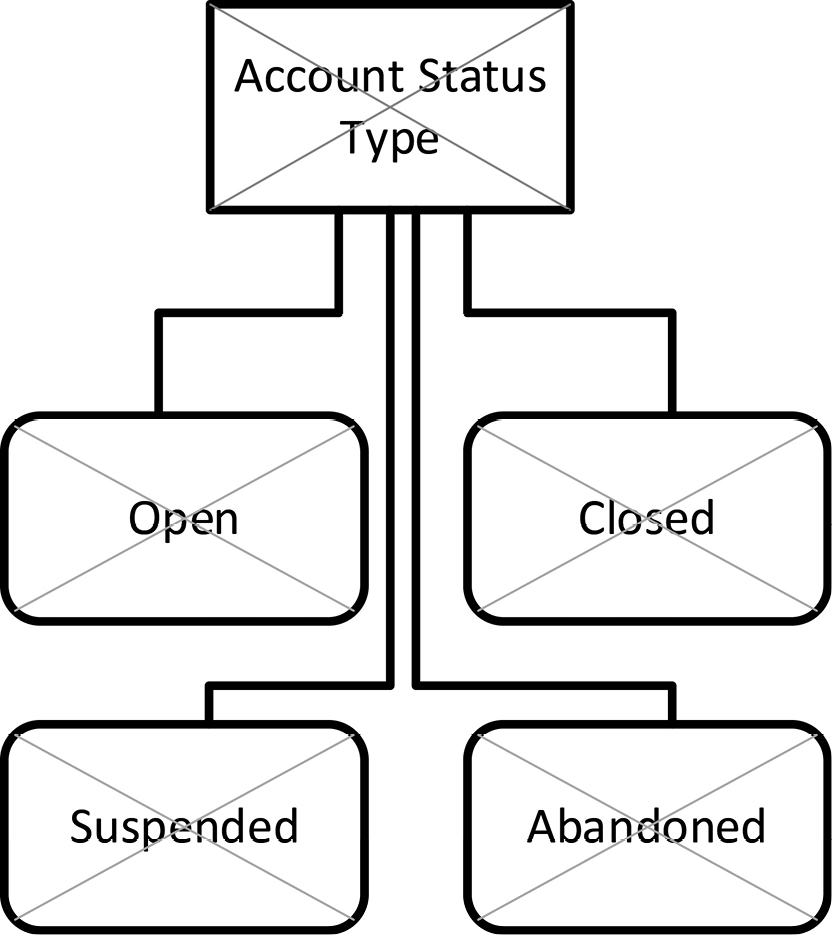

How will these enumerated values be represented in a running system? That is a physical design decision that is expressed through classes. It is possible that a program would represent the values using integers in the range 0-3, and a database would store each status as a single letter code. A user interface would wish to display the values using their full character string form. All three modes of representation can be expressed in COMN, separately from the type diagram but mapped to it. Figure 11-3 shows just one possible representation of the enumerated type, as letter codes. Other representations could be shown on the same or different diagrams.

This figure gives more detail than would ordinarily be shown, for the purposes of teaching the notation. It’s easy to see that each possible state of an object of the Account Status Char Class represents a value of the Account Status Type, and it is therefore valid to say that the Account Status Char Class represents the Account Status Type. In the upper right-hand corner we’ve shown that the Account Status Char Class is composed of something called CHAR{1}, which is a DBMS type. The solid arrowhead indicates that the composition is by aggregation, meaning that the DBMS type is an integral part of the class, though it can still be seen as a separate component of the class. (Recall the definition of aggregation back in chapter 3.) The CHAR{1} class is composed of a simple hardware class, a byte, again through aggregation. We’ll look more closely at composition in chapter 12.

A conceptual modeler will focus solely on the abstract definition of Account Status Type and its enumerated values without giving a thought to its eventual representation and implementation. Database designers and programmers will focus on the middle section, giving thought to how to represent the abstract values in symbols such as characters and numbers. A data modeler will not normally show the details of representation at the lowest levels on a COMN model, but if he wanted to, he could. Furthermore, a data modeling tool could generate the low-level details from information in the model, in order to assist in analyzing physical design details, and as the final and heavily automated step in model-driven development.

Figure 11-3. Physical Representation of an Enumerated Type

Figure 11-3 is just a small representative sample of how COMN supports high-level analysis, decisions about representations for information, and physical design decisions. We will look at representation more closely as part of chapter 12, when we look at composite types.

As we will see in chapter 13, the type/class split makes it easier to work with subtypes, which are a powerful tool for analysis and design.

References

[Holmevik 1994] Holmevik, Jan Rune (1994). “Compiling Simula: A historical study of technological genesis”. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 16 (4): 25–37. doi:10.1109/85.329756.

|

Key Points

|

Chapter Glossary

simple type : a type that designates a set whose members have no components

composite type : a type that designates a set whose members have components