|

|

Before the type/class split, we could consider the terms “subtype” and “subclass” to be synonyms. But now that a type designates a set while a class describes a computer object, these two terms take on distinct meanings. Both meanings are quite useful, separately and together.

Subtypes

The modern era of biological classification started in about the Sixteenth Century, as biologists began to recognize common characteristics across classes of animals, and began to create “super-classes” of animals. For instance, elephants, lions, and tigers were all classified as “mammals”. Lions, tigers, jaguars, and other similar mammals were recognized as a subclass of mammals called “cats”. A full taxonomy (system of classification) was developed by a number of scientists, and refined over time.

There are many taxonomies that classify many things besides animals. For example, there are systems for classifying currency (for example, hard and soft), crimes (for example, misdemeanors and felonies), and passenger cars (for example, 2-door, 4-door, and SUV). There can even be multiple classification systems for a single set of things. For example, here are just a few ways the cards in a standard deck of 52 playing cards can be classified:

- by suit: diamonds, hearts, spades, clubs

- by suit color: red, black

- by rank: face card, number card

Many of the most fascinating card games classify playing cards by complex criteria, and even by dynamically changing classification criteria. For example, some games allow a player to designate a suit of cards to be “trump”, making all cards of that suit rank higher than any other card for the duration of one round (hand) of the card game. In the next round, the trump might be different.

A subset is a set of things drawn from a larger set of things. Just as a type designates a set, a subtype designates a subset. A subtype is always related to the type that designates the larger set; that is its supertype.

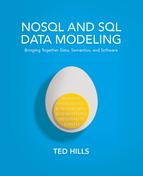

As an example, let’s consider the nature of some forms of government. Figure 13-1 shows a brief taxonomy of forms of government. All of the shapes and connecting lines are both dashed and bold. They are dashed to show that they are about concepts, not material objects. They are bold because they are about real-world concepts, not data concepts.

Figure 13-1. A Taxonomy of Forms of Government

You’ve seen the type rectangles before. The new shape in this figure is the pentagon, which depicts a restriction relationship. The wider side of each pentagon is towards the type that designates the set with more members; in other words, the supertype. The pointed side of each pentagon is towards the type that designates the set with fewer members; in other words, the subtype. For each subtype, there is some restricting condition, not directly modeled, that determines whether a member of the supertype is included in the subtype. For instance, it’s clear from the labeling of the type rectangles that, out of the set of all possible forms of government, only those governments where the individual is considered to be greater than the state are in the set designated by the type, “Form of Government Where Individual Greater Than State”.

The X in each pentagon indicates that the subtypes connected through it to a common supertype are exclusive of each other. In other words, a given member of the set designated by one subtype is not designated by the other subtype.

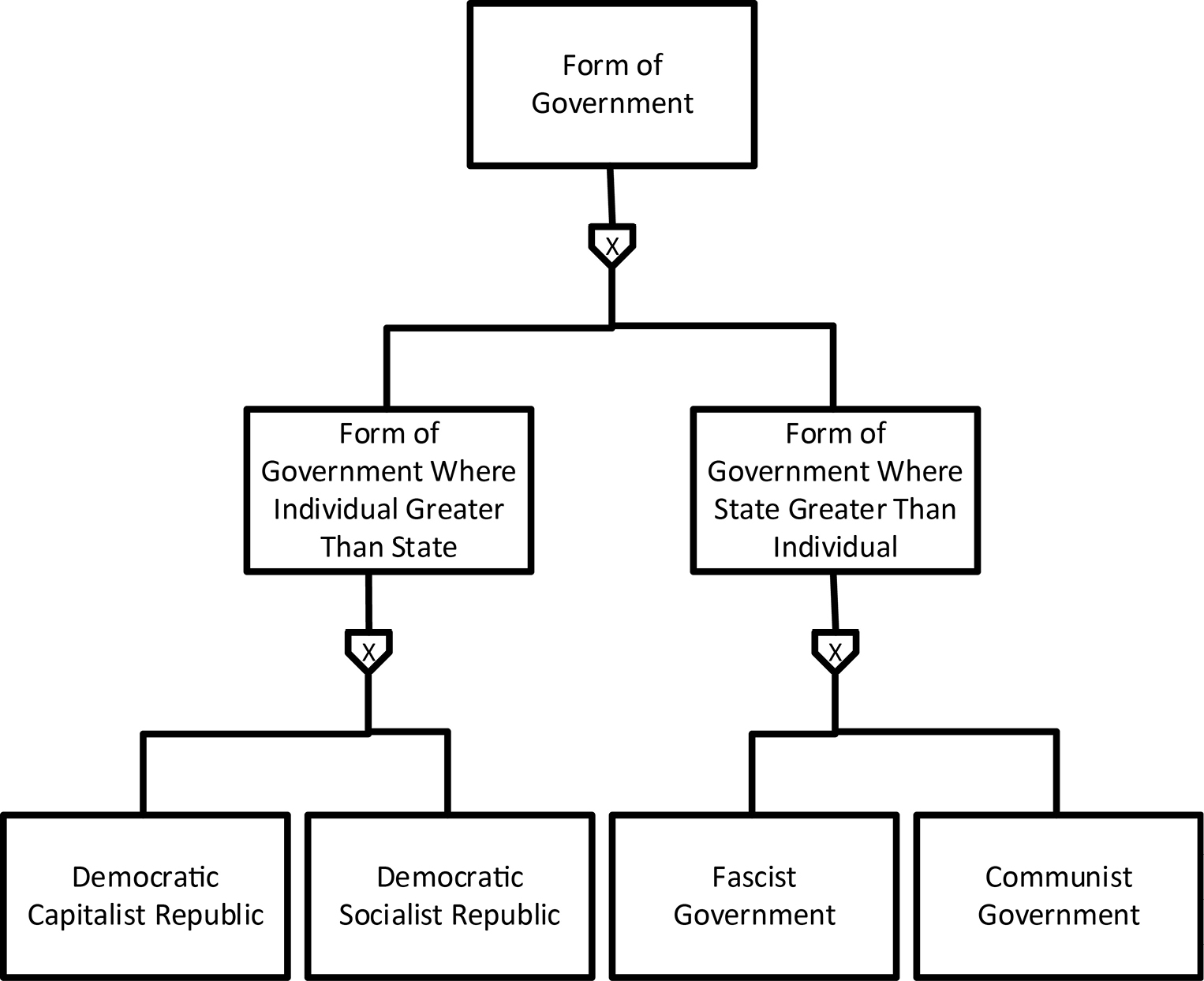

It is very common to define subtypes as restrictions on supertypes. But we can go the other way around, too. For example, we can define the type called “alphanumeric character” as a supertype of the types “letter” and “number”. Figure 13-2 is a model of the alphanumeric character type. The symbols are mostly the same as in Figure 13-1. Let’s look at the differences.

Figure 13-2. Alphanumeric Character as a Supertype of Letter and Digit.

First of all, the shapes and connecting lines in this figure are solid and bold. They are solid because characters are material objects. An individual character doesn’t exist unless it can be seen. It has to exist as some relatively stable configuration of matter. It could be ink on paper, or liquid crystals on a computer display, or even objects on a flat surface juxtaposed to form characters. The COMN shapes are bold because the material objects being described exist outside a computer’s memory. Something we refer to as a character that’s inside a computer’s memory exists only as a representation of a character, and not a character itself. Those kinds of characters don’t get bold outlines.

The second difference is that there is an arrowhead on the line from Alphanumeric Character to the pentagon. Arrowheads on lines in COMN always indicate a direction of reference. This arrow says that the Alphanumeric Character type references the Letter and Digit types, and not the other way around. This is what tells us that Alphanumeric Character is defined in terms of its subtypes. Such a supertype is called a union type, because the set it designates is the union of the sets designated by its subtypes. When a type is defined like this, it is more accurate to call the relationship represented by the pentagon an inclusion relationship, especially since there is no restriction in effect. But the sub/super-type relationships that result are the same as those in a restriction relationship.

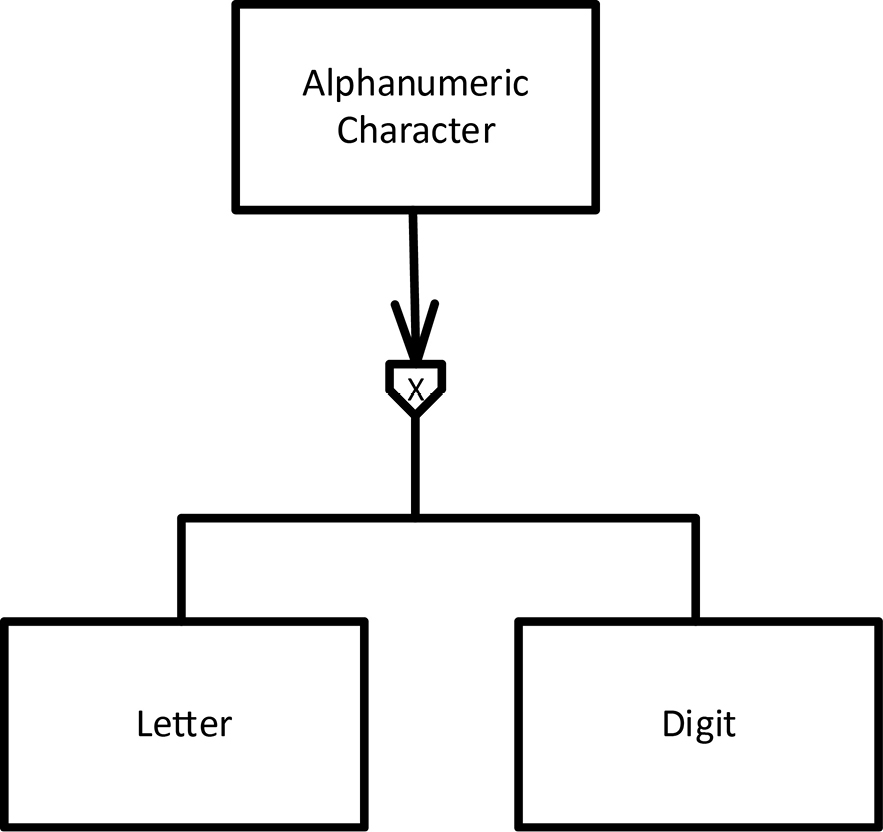

Figures 13-1 and 13-2 show simple strict type hierarchies, where each type has only one supertype, except for the type at the top, which has no supertype. But not everything is that simple, and it is a major mistake in analysis to force all things into a single type hierarchy with a single root. To illustrate, let’s go back to our deck of playing cards. Realize that any standard deck of playing cards can be divided in half based on the color of the suits (excluding jokers): all cards in a red suit (hearts and diamonds) can be put in one pile, and all cards in a black suit (spades and clubs) can be put in the other pile. We could then further subdivide the two piles by the four suits. Figure 13-3 shows this type hierarchy. The shapes and lines are in bold outline because they describe real-world things. Since the things they describe are material objects, they are in solid outline. The rectangle at the top represents any playing card, regardless of suit, color, or rank. Each of the middle two rectangles represents the class of card whose suit is in one of the two colors. The rectangles at the bottom reflect the four suits.

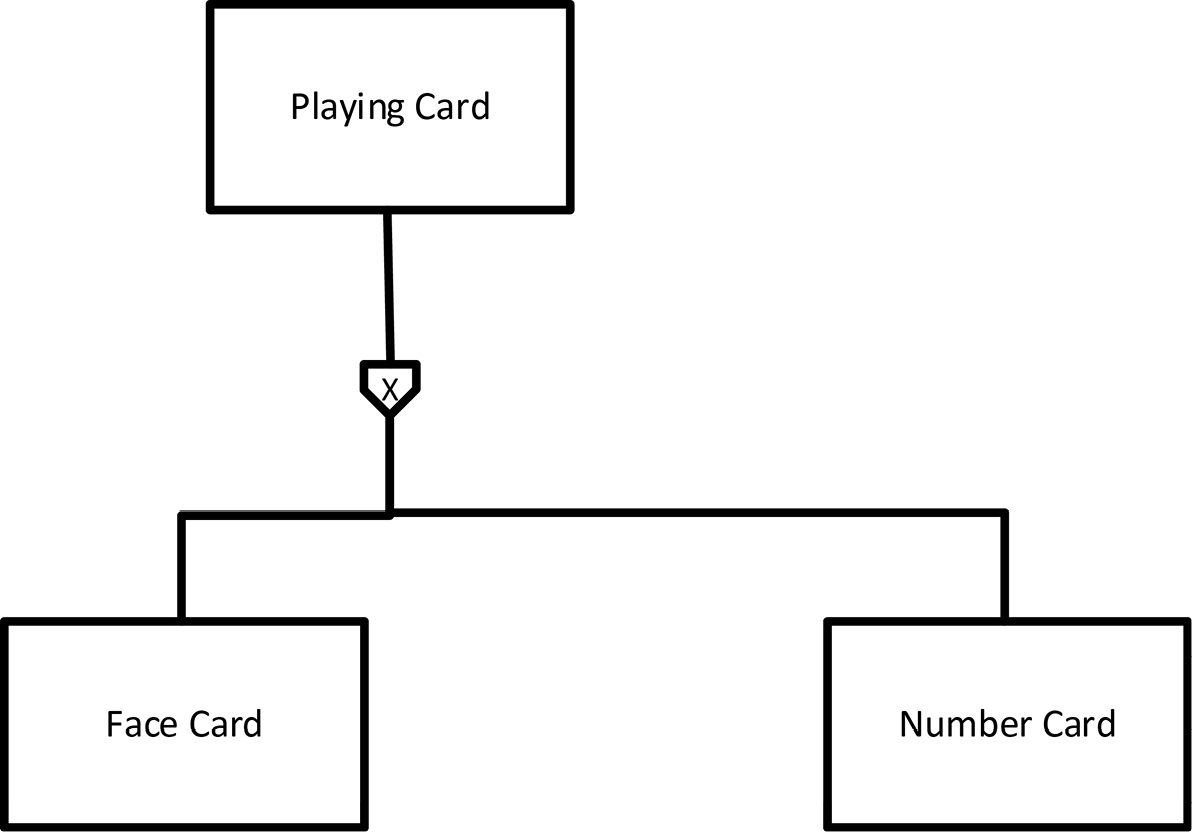

This is not the only way to divide a deck of cards. Figure 13-4 shows an alternative way of classifying playing cards, by type of rank: face card (king, queen, and jack) and number card (ace through ten).

Figure 13-3. Playing Cards Divided into Suits

Figure 13-4. Playing Cards Divided by Rank

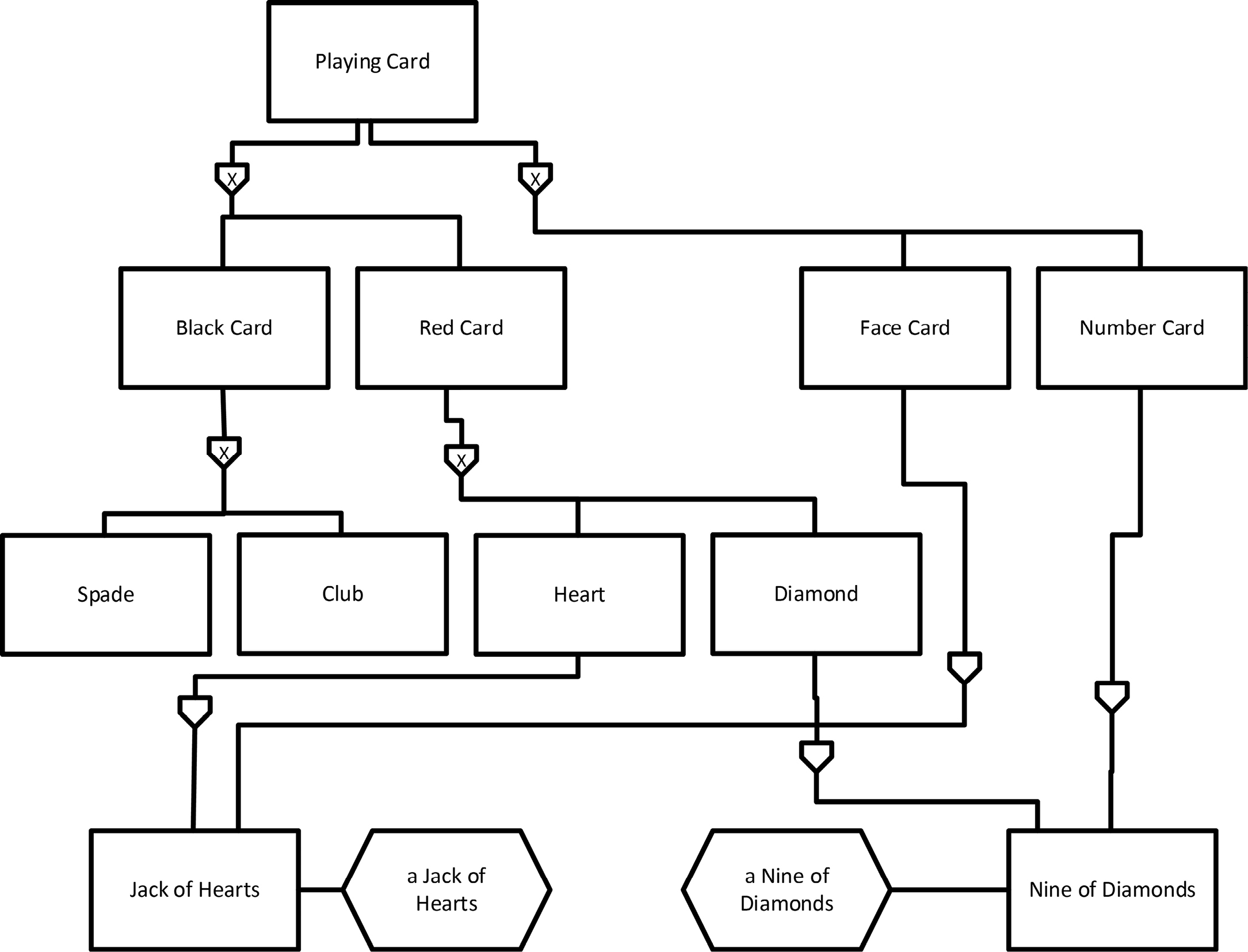

Figure 13-5 shows a deck of cards classified by all of the criteria above. Now we can see that, although a given classification system may be complete, there can be multiple classification systems side-by-side.

The symbols at the bottom of this figure deserve some attention. Two particular cards are shown: jack of hearts and nine of diamonds. But each is shown twice, once as a type and once as an object. That’s to emphasize that “jack of hearts” and “nine of diamonds” are still types of cards, not individual cards. Yes, it’s true that in a single deck of cards there will be only one card which is a jack of hearts and one card which is a nine of diamonds. But there is more than one deck of cards in the universe, and each deck contains one of those cards, so “jack of hearts” and “nine of diamonds” identify, not just one card, but a potentially unlimited set of cards. If we want to talk about hypothetical single cards, we show them using object symbols with the name beginning with the indefinite article, “a” (or “an”): “a jack of hearts” and “a nine of diamonds”.

Figure 13-5. Playing Cards Divided by Multiple Criteria

Each of the types “jack of hearts” and “nine of diamonds” is connected to two type hierarchies, the hierarchy that classifies by suit and the hierarchy that classifies by rank. This shows that a type can have more than one supertype. This is sometimes referred to as multiple inheritance, but we’ll avoid that term for now.

These illustrations of subtype/supertype relationships specified by restriction and inclusion have used real-world concepts and objects as examples, rather than data and computer objects. Subtype/supertype relationships work the same with data and computer objects. Since subtype/supertype relationships have to do with selecting members from supersets or combining members from subsets, no alterations to the structure of the types occur as a result of these operations. Because of this, no issues arise when an individual object (or concept) has multiple types. The problems of multiple inheritance only arise when one is dealing with subclassing, which we’ll review in the next section.

Restriction is Subtyping

Recall that we said in chapter 4 that a type could be defined in a number of ways, including:

- by selection

- by enumeration

- by generation

By far the most common method of defining a subtype is by selection from a supertype using some criteria. The criteria restrict which members of the supertype may be members of the subtype.

It turns out that every restriction defines a subtype. If you scan through any data system design, you will find many data definitions that are defined as restrictions on more general data definitions. These are all subtypes. Here are some examples:

- An edit control on a user interface page normally accepts any character, but code on the page restricts the control to accepting only decimal digits. The restricted edit control only accepts values of type “numeric string”, which is a subtype of “string”.

- A field in a database is defined with the database’s built-in type of “string”, but a constraint is defined on the field such that only strings matching a certain regular expression can be stored in it. The regular expression defines a subtype of string.

Here is a powerful analysis technique: When analyzing any system or its requirements, look for expressions that restrict possible values, and label that expression a subtype. Identify the set of values being restricted, and label that expression the supertype.

Subclasses

We know that types designate sets while classes describe objects. Let’s see how the physicality of objects affects what it means to have a subclass.

Recall from chapter 10 that the world of object-oriented programming defined the term “class” as a description of something in the memory of a computer. In object-oriented programming, a subclass is derived from a base class. The subclass includes (“inherits”) all of the components defined by the base class, and adds its own components to them. The methods of the base class continue to be valid for operating on objects of the subclass, but since they were written without knowledge of the subclass, they won’t operate on any components of objects that are only defined in the subclass. It is common practice for a subclass to override many of the methods inherited from the base class, in order to extend them to operate on components added by the subclass in addition to those of the base class.

This description of the structure of subclasses is complete without making any reference to meaning. The world of object-oriented programming has put a strong and fixed set of ideas on the meaning of subclasses, but we are going to keep those ideas on the side for now, and come back to them in the next section of this chapter. For now, we will focus only on the physicality of objects and the mechanism of subclassing. This is consistent with COMN’s view that, at their base, computer objects and their states have no intrinsic meaning.

A type designates a set. A class describes objects, but by so doing also designates a set, which is the potential and/or actual set of objects described by a class. The burning question, then, is, is a subclass equivalent to a subtype as described in the previous section?

To examine this question, let us consider the following base class and subclass:

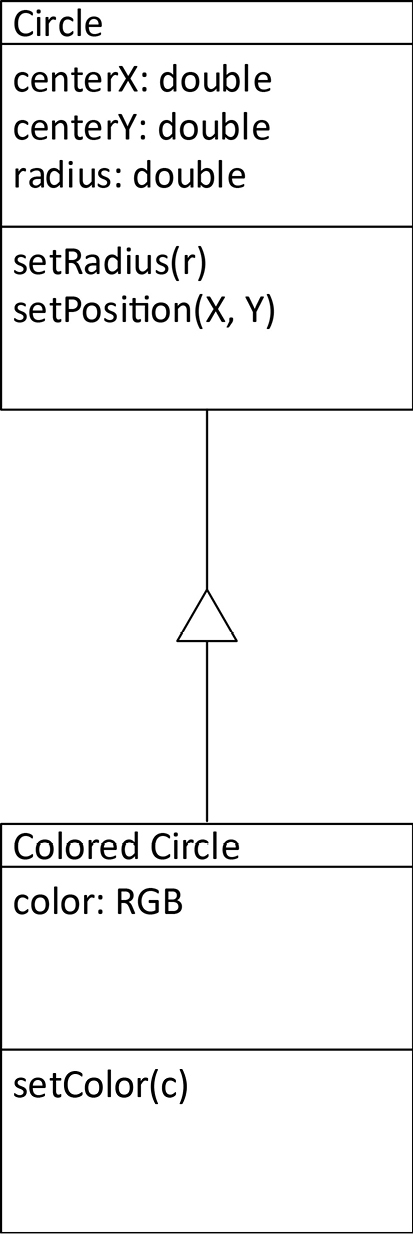

- The base class is Circle. This class describes an object representing a circle drawn on a graphical display. It holds three values: the X and Y coordinates of the center of the circle, and the radius of the circle. This is all the data that is needed to draw the circle on the display. The Circle class does not support the concept of color. A circle is always drawn in white on a black background. The methods of the class are simply setPosition (X, Y) and setRadius(r).

- The derived class is Colored Circle. This class inherits the X, Y, and radius components of Circle, and adds a fourth component, which is color. The setPosition and setRadius methods still work, but now there’s an additional setColor() method.

Figure 13-6 shows this design. The triangle between Circle and Colored Circle indicates extension, where the extending class adds components to those already in the base class, adds its own methods, and may override methods in the base class2. The way to remember the direction is that the wider side of the triangle is toward the class that adds components, while the narrower side of the triangle is toward the base class.

Figure 13-6. Circle and Colored Circle

Is Colored Circle a subtype of Circle? If it were, then it would describe fewer objects than Circle. In fact, it describes more objects than Circle. All Circle objects are white, while Colored Circles can have many more colors than white. In fact, every Circle object can be represented by a Colored Circle object whose color is set to white. A Circle is a subtype of a Colored Circle!

So we see, then, that—at least in this case—a subclass is not a subtype. In fact, the subtype relationship can be in the opposite direction of the subclass relationship.

COMN describes this kind of derivation relationship between two classes as extension. In order to avoid confusion with the term “subtype”, COMN avoids the term “subclass” and calls the class that adds components to the base class the extending class.

Since objects of an extending class have more components than those of their base class, objects of an extending class have more potential states.

Extension only applies to composite types and classes, because one can only add components to something that can have components. In contrast, subtyping applies equally to simple and composite types and classes, since it depends on restricting the (simple or composite) values and states of, respectively, variables and objects.

As object-oriented programmers know, defining a class as extending more than one base class can get pretty gnarly pretty fast. It is mostly out of the scope of this book to discuss that kind of multiple inheritance, but two comments are relevant. First, recall that restricting multiple supertypes is not a kind of multiple inheritance that leads to any problems. Only extending multiple base classes or types can become difficult. Second, if one is careful to define the type a class represents, and possibly a type hierarchy, before designing a class extension hierarchy, one is likely going to be guided to use extension in valid ways that are quite workable in implementation.

Subtypes and Extensions: Perfect Together

Let’s put these two ideas together, and see how they enable COMN to precisely model a common situation, which is a database of persons playing multiple roles. Let’s imagine we are developing a database in support of a coffee shop. (It could be a bank, or a retailer, or any business that has individuals as customers.) We have the usual “rewards” program, where regular customers earn points with every purchase. We therefore need to represent customers in our data. We also need to represent employees in our data, so that we can track their working hours and pay them. We need to know when an employee is also a customer, because we give our employees discounts on their purchases.

Naïve early data models for such situations would use two separate tables: one for employees and one for customers. This approach sounds good enough until you consider common scenarios:

- Each table would need the person’s name. The employee/customer would be obligated to enter his name twice, which is rather annoying.

- There would be the task of tracking which employee/customer pairs were in fact the same person. Personal names are notoriously difficult to use to achieve this, for many reasons, including:

- People’s names have many forms, and people can’t be depended upon to enter their names the same way every time. For example, I might use “Theodore” in the employee database and “Ted” in the customer database.

- People’s names aren’t unique.

For all these reasons and more, it would make much more sense to design a database with three tables:

- a table of persons, holding the data common to persons regardless of whether they are customers or employees

- a table of customers, holding data unique to customers, such as the dates of their last purchases

- a table of employees, holding data unique to employees, such as their dates of hire

The tables of customers and employees would refer back to the table of persons for data common to both.

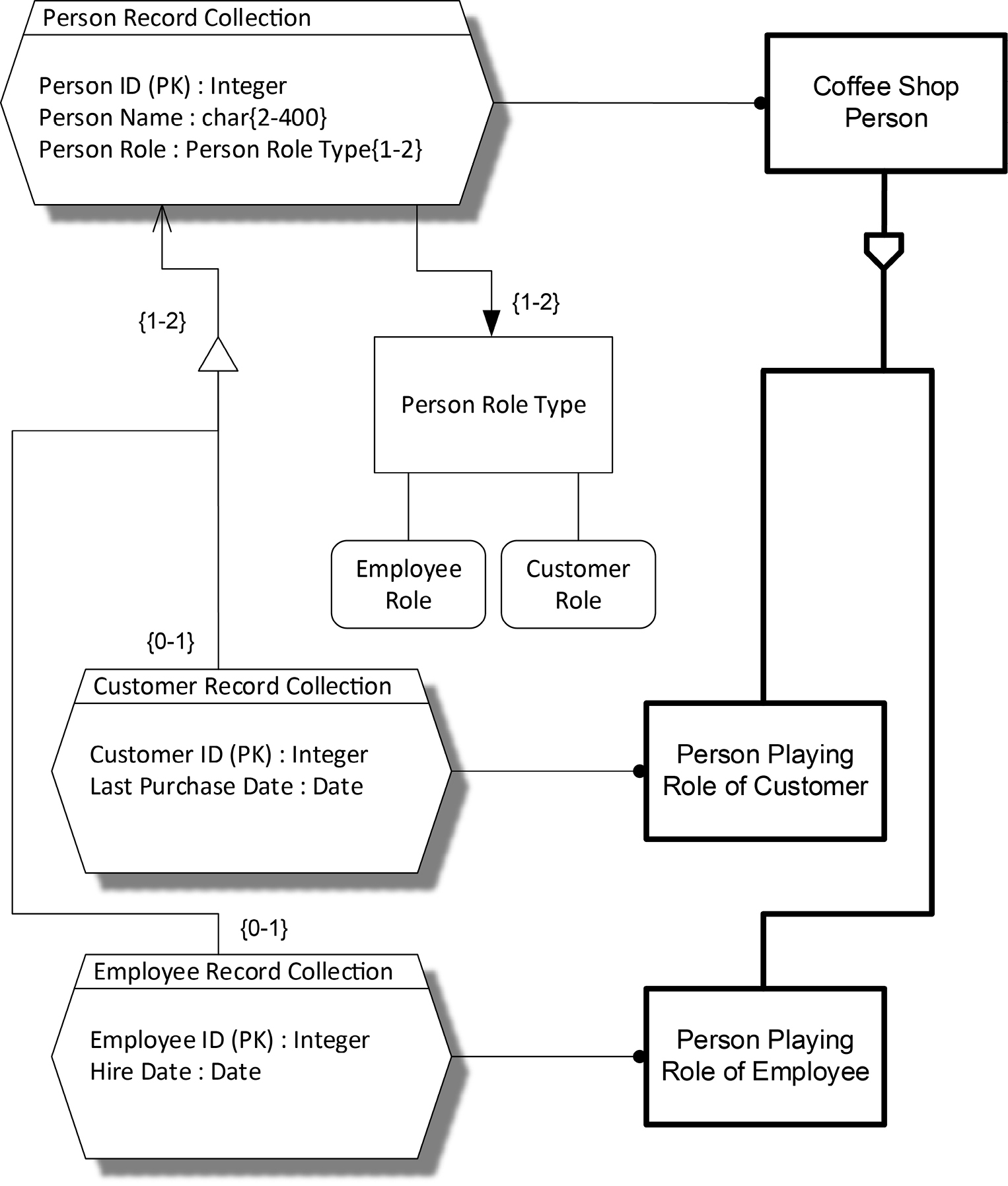

See Figure 13-7 for a depiction of such a design. Let’s take a close look at this model. In the top right-hand corner of the diagram we have Coffee Shop Person, which is the type that designates the set of real-world persons that matter to the coffee shop, namely employees and/or customers. Below the Coffee Shop Person type we have two subtypes, connected by the restriction pentagon. Some are customers, or, to be more technically accurate, persons playing the role of being a customer. Some are employees, similarly playing a role. The pentagon has no X in it, meaning that you might find the same person as a member of both subtypes—in other words, a person who is both a customer and an employee.

Figure 13-7. Coffee Shop Persons

To the left of the Coffee Shop Person rectangle we have a dashed hexagon representing the collection of logical records that will hold data about these persons. This is our first example of a hexagon divided into two parts. The top part contains the name of the collection of records, and the bottom part contains the names and types of the components of each record. This form of COMN enables one to model a set of composite variables or objects without an explicitly named type.

Each record in the Person Record Collection has three components: the internally generated meaningless number, called Person ID, which we use to distinctly identify each person; each person’s name as Person Name; and the role(s) played by each person. The component name Person ID is followed by the letters PK in parentheses, indicating that it is a key to any set of Person data. The relationship line from Person to Coffee Shop Person is a representation relationship. It is the values of the key of Person Record Collection, namely Person ID values, which represent, or identify, Coffee Shop Persons.

The Person Role component of a person record is defined as an array of one to two variables of type Person Role Type. This tells us all we need to know about the Person Role component, but we’d like to know more about the Person Role Type, so that has been drawn, connected to the Person Record Collection with a line having a solid arrowhead, which indicates aggregation. When variables are defined in-line in a data structure, they are juxtaposed, and their types are effectively aggregated together in the structure’s type.

There are two values depicted as values of the Person Role type, namely Customer Role and Employee Role. Each of the one or two elements of the Person Role component of a person record can be bound to either of these role values. We presume that there is a business rule that eliminates the possibility that a person could be recorded as playing the employee role twice or as playing the customer role twice. This rule is not expressed directly in this model, but it is expressed indirectly through the relationships to the customer and employee record collections, as we shall see.

Below the Person Record Collection we have two more record collections, one each for Customers and Employees. These are connected to the Person logical record type via a triangle, which is COMN’s symbol for extension. The wider base of the triangle is on the side towards the types that extend the Person type, in an analogy to the fact that these types have more components than Person. Don’t read the triangle as indicating direction of reference. The direction of reference is given by the arrowhead pointing to Person.

The multiplicity of the extension relationship is given differently above and below the triangle symbol. Below the triangle, the text “{0-1}” indicates that a customer record might or might not extend a person record, and an employee record might or might not extend a person record. Above the triangle, the text “{1-2}” indicates that a person record will be extended at least once and possibly twice. The model therefore indicates that a person record must not be created without creating at least one extending record. This prevents the system from keeping records of data about persons who are neither customers nor employees—probably a good thing.

The Customer and Employee logical record types include their own IDs, which are in addition to Person ID. You can imagine customers with key-ring cards with bar codes on them holding their customer IDs, and employees with identification badges showing their employee numbers. Customers and employees will typically not know their Person IDs.

It is an implementation question whether Person ID values will be carried on Customer and Employee records, or whether two or three records of these types will be aggregated, such that Person ID is immediately accessible. This design decision is influenced by whether we implement in a SQL or NoSQL database. We can document the logical design, and defer that physical question. We will examine physical database design issues in chapter 18.

The Customer and Employee logical record types each hold data that is applicable only to customers and employees, respectively. Only customers have a Last Purchase Date, and only employees have a Hire Date. Extension is meant whenever a composite type or a class is extended with additional components, such that instances of the extending type or class may have more values or states, respectively, than the base type or class.

This picture is completed by the representation lines drawn from the Customer and Employee record collections to these Person Playing Role types. We see that the Customer Record Collection represents the type of Person Playing Role of Customer, and the Employee Record Collection represents the type Person Playing Role of Employee. A Customer ID identifies a customer, and an Employee ID identifies an employee.

Thus we see that extension and subtyping are very different but often exist side-by-side.

Inheritance

Both subtyping and extension are valuable because they enable us to define data and write software that inherits components and/or methods of a supertype, base type, or base class. The derived type or class can then be defined merely in terms of what’s different from or in addition to the base. This makes the task of writing software more efficient. It also makes software more reliable, because it is easier to verify the correctness of a base type or class, and then separately verify the correctness of a derived type or class assuming that the base is correct, than it is to verify two separate but redundant implementations, especially when one implementation—the one that would have been derived—is more complex than the other.

Inheritance multiplies reuse when you realize that variables, values, and objects of derived types or classes can sometimes be used in places where only the base types or classes were contemplated in the original design. These are extremely powerful mechanisms for expanding software and data reuse. But this kind of reuse is subject to certain limitations—limitations that, it turns out, guarantee the correctness of the reuse. Let’s look at these more closely.

Using Subtype Variables and Values

Suppose we have a logical record type with a component defined as a number of up to 5 decimal digits. Suppose we have a user interface page with an edit box allowing the entry of up to 4 decimal digits. The type “4 digit decimal number” is a subtype of the type “5 digit decimal number”. We can see that it will always be safe to store numbers entered in the user interface in the logical record type’s 5-digit component. In fact, if the system knows of these type definitions, it doesn’t even need to check values before allowing the storage, because it can depend on the subtype relationship to guarantee that the values coming from the user interface are within the range provided by the storage system.

Clearly, going in the reverse direction is not so safe. If our system retrieves a 5-digit number from a record, and attempts to display it in a 4-digit field in a user-interface, it had better first check whether the value from the record is no greater than 9,999. If the value were too large, it would be truncated on display and mislead the user as to the actual value. It would be better for the system to report an error (an “exception”), so that someone could either correct the data or the software. This simple example illustrates truths about rules regarding subtype variables and values.

- A value of a subtype can always be safely assigned to a variable of its supertype.

- Because of the above fact, any variable of a subtype can be safely assigned to a variable of its supertype.

- A value of a supertype might be able to be assigned to a variable of a subtype, but its value needs to be checked first to see if it meets the subtype’s constraints.

- Because of the above fact, any variable of a supertype might be able to be assigned to a variable of a subtype, but its value needs to be checked first to see if it meets the subtype’s constraints.

Using Extending Types and Classes

Recall our Circle and Colored Circle classes. If we pass a Colored Circle object to software written before circles had color, that software should be able to use the setPosition and setRadius methods of the Colored Circle object and get the right behavior out of the circle. It won’t be able to affect the color of the object, but that’s OK: through extension we have made it possible for software written to be able to operate on objects of the base class to be able to operate on objects of the extending class, too.

Things don’t work so nicely in the reverse direction. If we try to pass an object of a non-colored Circle to software expecting Colored Circles, that software could fail when it tried to invoke the non-existent setColor method of the plain (white) Circle object. This simple example illustrates truths about rules regarding extending class objects.

- An object of an extending class may be passed to software expecting an object of its base class.

- An object of a base class may not be passed to software expecting an object of an extending class (of the base class).

Projection: The Inverse of Extension

Just as inclusion is the inverse of restriction, projection is the inverse of extension. Projection is the process of eliminating components from a base class or type.

Projection is a common operation in SQL databases. The process of selecting a subset of a table’s columns in a query or view is projection. Projection is just as meaningful for types or classes in memory, except that projection can invalidate any methods that reference components that have been projected away.

The extension triangle represents projection when it is read in the reverse direction. A direction of reference arrow indicates when the projecting model element references the base model element. We’ll see some uses of projection in chapter 17 on physical design.

|

Key Points

|

Chapter Glossary

subtype : something that designates a subset of the set designated by another type, called the supertype

restriction relationship : a relationship between two types, where one type, called the subtype, is defined in terms of a restriction on members of the set designated by the other type, called the supertype; inverse of inclusion relationship

inclusion relationship : a relationship between types, where the supertype is defined as a union of its subtypes; inverse of restriction relationship

extending class (or type) : a class (or type) that is defined in terms of another class (or type), called a base class (or type), by defining components and/or methods to what are already available in the base class (or type)

extension : the addition of components to a base class or type; its inverse is projection