|

|

Sam came barreling into the plant manager’s office, clutching a roll of blueprints in one hand. He was so excited. “Joe, have I got great news!” he called out.

Joe looked up from his desk behind the office counter. He looked weary. Well, keeping track of everything that goes on in a 150-acre refinery that processes 200,000 barrels of oil a day could make anyone weary. He pushed back his chair, got up, and ambled over to the counter.

“What’s the news?” Joe asked.

“The boys in engineering have figured out that, by just combining a few material flows earlier in the process, the petrochemical plant could reduce emissions, produce more product from the same input flows, and add $5,000 a day to the plant’s bottom line in reduced expenses! So I’ve come down here to find out what it will take to implement these changes.” Joe placed the rolled-up blueprints on the counter and spread them out.

Sam started studying the drawings, running his finger over the many lines and shapes that represented the thousands of pipes visible out the office windows. He licked his finger and pulled the top drawing back to look at the next blueprint, and then the next, all while Joe watched excitedly but silently. Sam had a reputation. He knew his stuff. If Sam said it could be done, it could be done, and if he said it couldn’t, well, you’d better do a ton of research before you said Sam was wrong.

Finally Sam looked up from the counter. “I think I get it. This isn’t too bad. We’ll just have to re-route a few pipes and this could be implemented pretty easily.”

Joe was happy and relieved. “So, how long do you think it will take?”

Sam kept his look level when he delivered the blow. “I think about six months.”

“Six months!” Joe nearly shouted. “I thought you said this was easy! Why, in six months we will have lost”—Joe figured fast in his head—“nearly a million dollars in savings!”

“I know, but it can’t be helped,” Sam explained. “You see, although the change is easy, we have to be really careful we don’t mess up any downstream product flows that could be inadvertently affected by this change. And that takes time to figure out.”

“It takes six months to look at these drawings and figure out what the impact of the change is?” Joe asked, somewhat incredulously.

Sam’s poker face began to show a little discomfort. “Well, that’s the problem,” Sam said. “You see, the drawings engineering used weren’t up to date, so we have to check them against the actual piping, and update them, and then look at the change request again.”

Joe wasn’t just going to accept this as the final verdict. “Why do you have to look at the actual piping? Why not pull out the latest drawings that engineering should have used, and compare to them?”

Sam began to turn a little red. “I’m not quite sure how to say this, but engineering did use the latest drawings we have on file. The problem is that they don’t match what’s actually been implemented in the plant.”

Joe felt the tension rising, and realized that now was the time to pull out all his diplomatic skills, to avoid a confrontation that could hide the truth. He paused a moment, looked down at the counter to collect his thoughts, put on his best “professor” demeanor, and then looked up at Sam. “So I guess what you’re saying is that changes were made in the field, but the drawings weren’t updated to reflect them.”

“That’s right,” Sam said quietly. “The project office doesn’t like us spending time on drawings when we should be out in the field fixing things, and no one ever asks us for the drawings, so we just do stuff to make the plant run better and the drawings stay in the filing drawer.”

Joe was surprised and a bit distressed, but kept his voice level. “Interesting. What kinds of changes do you do out in the field that don’t require engineering’s involvement?”

“We’ve got this great guy—Manny. He’s worked here for 30 years, and knows where every pipe goes and how every fitting fits together. When something goes wrong, we call Manny, and he usually fixes the problem and finds an improvement that the engineering guys overlooked. So we discuss it and then implement the improvement, and everything runs better.”

“But no one updates the drawings,” Joe said quietly.

“Well, yeah,” Sam muttered embarrassedly, looking away from Joe.

“And no one tells engineering what changed,” Joe added. Sam didn’t say anything. “Well, Sam, thanks for explaining the situation. I’ll go back to the project office and we’ll see if we can figure out any way to update the drawings with the current process flows in less than six months.” Joe turned to go, but then hesitated and turned back. “Could Manny work with the engineers to document his changes? I presume that would be faster than having someone check every single connection.”

Sam turned white. He didn’t want to break this news. “Manny doesn’t work here anymore.”

Joe’s shoulders slumped. “What happened to him?”

“He retired last month.”

Taking Care of Data

This sad story of plant change control gone awry, changes made in the field without engineering involvement or approval, and a lack of any documentation about the current state of things, will likely be all too familiar to many readers. This is often how we treat our databases and our software. When we roll out a new system, our documentation will be pretty good for a few months, but then, as the changes accumulate, the documentation moves from being an asset to being overhead, and eventually even becoming a liability, as there is a risk that someone might rely on what it says when it’s completely wrong.

This plant change control story is, of course, fictitious, and not at all representative of what goes on in chemical plants or in most construction-based industries. Such industries learned long ago that they need a strictly controlled process for making changes in a physical plant. Changes can originate with an engineer, a field operator, or a product manager, but all change requests follow the same strict process:

- Take a copy of the strictly controlled current drawing and update it with the requested change.

- Obtain engineering approval for the change.

- Implement the change according to the drawing.

- Check when the change is complete that the drawing matches the implementation exactly. Update the drawing if necessary to reflect the “as-built” condition of the plant.

- File the updated drawing as the latest, fully reliable picture of reality.

There is never any debate about whether the “overhead” of following this process is “worth it”. Everyone knows that a mistake could lead to a fire or an explosion in a chemical plant, a building collapse, or other possibilities we don’t even want to think about.

Unfortunately, we’re not so smart when it comes to our data designs. If someone has a bright idea how to make things better, then we say, sure, let’s give it a try. It might really be a bright idea, too, but someone needs to think through the potential unintended consequences of what an “improvement” could do to the rest of the system. But it’s really hard to think through the potential unintended consequences when an up-to-date drawing of a database design does not exist. Every change, even a trivial change, becomes slow, tedious, and full of risk.

Let’s fast forward a year to how things have worked out in our fictitious petrochemical plant.

Plant Change Control 2.0

Sam was in his office, happily conversing with one of his field operators. Life was good. Costs were down and profits were up. The Environmental Protection Agency was happy about the recent reduction in emissions. And things didn’t seem to be breaking as often as they used to.

Joe walked into the plant manager’s office. As soon as he saw Joe, Sam came over to shake his hand. “How are things, Joe? Have any more brilliant money-saving ideas for us?”

“Not today, Sam. Just thought I’d see how implementation is going on the last one.”

“Well,” Sam said, “Robbie is out there right now making a final check on the actual piping versus the as-built drawings. As soon as he’s done that, he’ll implement the change. He’ll be done checking today, and he’ll start the changes tomorrow.”

“Done today?” Joe exclaimed. “I thought he only started checking today.”

“That’s right.” Sam smiled. “Robbie is fast.”

“Faster than Manny,” Joe joked, and winked.

“You got that,” Sam retorted.

Where did the Savings Come From?

You see, Robbie is a robot. Robbie is comparing the pipes and fittings he sees to an electronic drawing that shows what they should be. If there are any differences—which could only come about if someone deviated from the change-control process—Robbie will report exactly what those differences are, the drawings will be updated to reflect the changes, and engineering will be notified of a change they didn’t authorize.

It’s relatively easy to envision drawings of pipes and fittings, and the pipes and fittings themselves. With data, it’s not so easy. Data is abstract. You can’t walk up to it and touch it, or pick it up and move it around. Nonetheless, our databases are very much like the pipes and fittings of a petrochemical plant. They define what the data is and how it is interconnected. A data model gives us a way to visualize the data and its inter-relationships. A data model is our tool to design and plan for our data before a database is created, and to keep track of changes to the database after it’s been implemented.

It sounds a bit far-fetched—or at least a little bit futuristic—to imagine a robot looking at pipes and fittings and comparing them to drawings, but this capability exists for the majority of our databases today. Most database designs to this point have been implemented using something called the Structured Query Language, or SQL. Software tool vendors have done a superb job building so-called “data modeling tools” that enable a person to draw a graphical design for a database at a high level of abstraction, progressively add detail to that design (a process called stepwise refinement) until it is detailed enough to implement, then literally “push a button” and have the tool generate the database itself. The same tools enable a person to read the design of a database and generate a graphical model which is an “as-built” drawing. The first process—from drawing to implementation—is called forward engineering, and the second process—generating a drawing from an actual implementation—is called reverse engineering. The forward-engineered model can be compared to the reverse-engineered model in order to ensure that they stay in sync—that no unauthorized changes have been made to the implementation without first updating the design. This process of forward- and reverse-engineering with comparison is called round-trip engineering. When combined with a disciplined change-control process that makes sure every change starts with the design drawings, the process is called model-driven development.

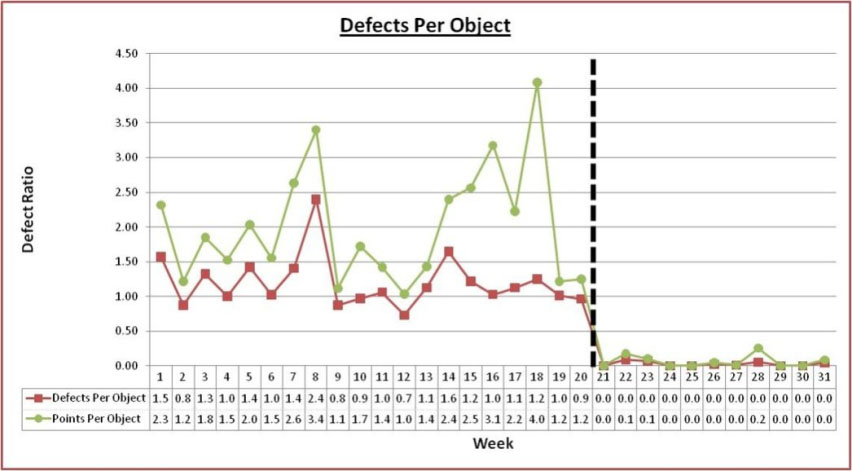

There are many stories of disciplined data modeling leading to faster delivery and fewer bugs. Figure 1 below shows what happened after data modeling was introduced to the database implementation of one agile software development project.

There are many other such stories that can and have been told, where disciplined data modeling saved a project, and ongoing data modeling processes kept a system healthy.

Figure 1. Defects per Object Before and After Data Modeling Adopted. Courtesy of Ron Huizenga.

I have personally had positive experiences in my career with model-driven development. It leads to many happy people:

- Engineers (often referred to as “data modelers”, “data architects”, and “database administrators” in IT projects) are happy because they know that the database they are responsible for is truly under their control. All changes go through them, and they can look for the far-reaching implications of what may appear to be simple changes.

- Implementers (called “software developers” and “database developers” in IT projects) are happy because they can trust that someone thought about potential unintended consequences before a change was made, and in fact the engineers included them in that process.

- Managers, operational personnel, marketers, sales people, and other business stakeholders are happy because change requests are handled quickly and efficiently, with the utmost automation possible.

- Everyone is happy because the design documentation is a living, breathing thing that is an asset to the corporation.

I have written this book for many reasons, but many of those reasons could be summed up as my desire to see model-driven development become the norm in information technology.

There are two barriers to this happening and this book is aimed at destroying both of them.

First, there aren’t enough people who know what data modeling is and how to use it effectively. There needs to be a cadre of well-trained data modelers who know how to use data modeling notations, techniques, and tools to do forward and reverse engineering of databases. This book is intended to educate such people.

Second, existing theories of data aren’t enough. Although data modeling tools can do forward and reverse engineering of SQL databases, there is a relatively new set of database technologies collectively called NoSQL database management systems (DBMSs) not yet supported by traditional tools. Some of the difficulties the data modeling tool vendors are having adapting to these newer tools originate with defective theories of data. This book refines our current data theories so they work just as well with NoSQL databases as they do with SQL databases. These updated theories of data also mesh with semantics and with software design, so that data designs can make sense as a description of real world objects and concepts, can meet business requirements, and can guide implementation.

Business stakeholders, software developers, and many others need to learn about the pitfalls of poorly managed data and the advantages of model-driven development. For them, there will be white papers, seminars, conference presentations, and more. But for you—whether you are a seasoned data modeler or just getting started—this book will teach you how to be the master of any data design problem that comes your way.

As the title implies, NoSQL and SQL Data Modeling teaches techniques for database design that are applicable to both the newer NoSQL (No SQL or Not Only SQL) databases and the traditional SQL databases. It draws connections to representations of the real world, and of meaning (semantics) in the real world and in data. It shows how data is represented in and manipulated by object-oriented software. It introduces the Concept and Object Modeling Notation or COMN (pronounced “common”) for documenting data designs.

Why Model?

Creating a model is not an absolutely necessary step before implementing a database. So, why would we want to take the time to draw up a data model at all, rather than just diving in and creating the database and storing data? A data model describes the schema of a database or document, but if our NoSQL DBMS is “schema-less” or “schema-free”, meaning that we don’t need to dictate the schema to the DBMS before we start writing data, what sense does it make to model at all?

The advantage of a schema-less DBMS is that one can start storing and accessing data without first defining a schema. While this sounds great, and certainly facilitates a speedy start to a data project, experience shows that a lack of forethought is usually followed by a lot of afterthought. As data volumes grow and access times become significant, thought needs to be given to re-organizing data in order to speed access and update, and sometimes to change tradeoffs between the speed, consistency, and atomicity of various styles of access. It is also commonly the case that patterns emerge in the data’s structure, and the realization grows that, although the DBMS demands no particular data schema, much of the data being stored has some significant schema in common.

So, some vendors say, just reorganize your data dynamically. That’s fine if the volume isn’t too large. If a lot of data has been stored, reorganization can be costly in terms of time and even storage space that’s temporarily needed, possibly delaying important customers’ access to the data. And schema changes don’t just affect the data: they can affect application code that must necessarily be written with at least a few assumptions about the data’s schema.

A data model gives the opportunity to play with database design options on paper, on a whiteboard, or in a drawing tool such as Microsoft Visio, before one has to worry about the syntax of data definitions, data already stored, or application logic. It’s a great way to think through the implications of data organization, and/or to recognize in advance important patterns in the data, before committing to any particular design. It’s a lot easier to redraw part of a model than to recreate a database schema, move significant quantities of data around, and change application code.

If one is implementing in a schema-less DBMS without a model, then, after implementation is complete, the only ways to understand the data will be to talk to a developer or look at code. Being dependent on developers to understand the data can severely restrict the bandwidth business people have available to propose changes and expansions to the data, and can be a burden on developers. And although you might have friendly developers, trying to deduce the structure of data from code can be a very unfriendly experience. In such situations, a model might be your best hope.

Beside schema-less DBMSs, some NoSQL DBMSs support schemas. Document DBMSs often support XML Schema, JSON Schema, or other schema languages. And, even when not required, it is often highly desirable to enforce conformance to some schema for some or all of the data being stored, in order to make it more likely that only valid data is stored, and to give guarantees to application code that a certain degree of sanity is present in the data.

And this is not all theory. I have seen first-hand the failure of projects due to a lack of a data model or a lack of data modeling discipline. I have also seen tremendous successes resulting from the intelligent and disciplined application of data modeling to database designs.

Here are some stories of failure and of success:

- A customer data management system was designed and developed using the latest object-oriented software design techniques. Data objects were persisted and reconstituted using an object/relational mapping tool. After the system was implemented, performance was terrible, and simple queries for customer status either couldn’t be done or were nearly impossible to implement. Almost everyone on the project, from the manager to the lowliest developer, either left the company or was fired, and the entire system had to be re-implemented, this time successfully using a data model and traditional database design.

- Two customer relationship management (CRM) systems were implemented. One followed the data model closely; the other deviated from the model to “improve” things a bit. The CRM system that deviated from the model had constant data quality problems, because it forced operational personnel to duplicate data manually, and of course the data that was supposed to be duplicated never quite matched. It also required double the work to maintain the data that, in the original model, was defined to be in only one place. In contrast, the CRM system that followed the data model had none of these data quality or operational problems.

- A major financial services firm developed a database of every kind of financial instrument traded in every exchange around the world. The database was multi-currency and multi-language, and kept historical records plus future-dated data for new financial instruments that were going to start trading soon. The system was a success from day one. A model-driven development process was used to create the system, and to maintain it as additional financial instrument types were added, so that all database changes started with a data modeler and a data model change. Database change commands were generated directly from the model. The system remained successful for its entire lifetime.

- A business person requested that the name of a product be changed on a report, to match changes in how the business was marketing its products. Because the database underlying the report had not been designed with proper keys, the change, which should have taken a few minutes, took several weeks.

You see, developing a data model is just like developing a blueprint for a building. If you’re building a small building, or one that doesn’t have to last, then you can risk skipping the drawings and going right to construction. But those projects are rare. Besides, those simple, “one-off” projects have a tendency to outlive early expectations, to grow beyond their original requirements, and become real problems if implemented without a solid design. For any significant project, to achieve success and lasting value, one needs a full data model developed and maintained as part of a model-driven development process. If you skip the modeling process, you risk the data equivalents of painting yourself into corners, disabling the system from adapting to changing requirements, baking in quality problems that are hard to fix, and even complete project failure.

Why COMN?

There are many data modeling notations already in the world. In fact, Part II of this book surveys most of them. So why do we need one more?

COMN’s goal is to be able to describe all of the following things in a single notation:

- the real world, with its objects and concepts

- data about real-world objects and concepts

- objects in a computer’s memory whose states represent data about real-world objects and concepts

COMN connects concepts, real-world objects, data, and implementation in a single notation. This makes it possible to have a single model that represents everything from the nouns of requirements all the way down to a functional database running in a NoSQL or SQL database management system. This gives a greater ability to trace requirements all the way through to an implementation and make sure nothing was lost in translation along the way. It enables changes to be similarly governed. It enables the expression of reverse-engineered data and the development of logical and conceptual models to give it meaning. It enables the modeling of things in the Internet of Things, in addition to modeling data about them. No other modeling notation can express all this, and that is why COMN is needed.

Book Outline

The book is divided into four parts. Part I lays out foundational concepts that are necessary for truly understanding what data is and how to think about it. It peels back the techno-speak that dominates data modeling today, and recovers the ordinary meanings of the English words we use when speaking of data. Do not skip part I! If you do, the rest of the book will be meaningless to you.

Part II reviews existing data modeling, semantic, and software notations, and object-oriented programming languages, and creates the connections between those and the COMN defined in this book. If you are experienced with any of those notations, you should read the relevant chapter(s) of part II. COMN uses some familiar terms in significantly different ways, so it is critical that you learn these differences. Those chapters about notations you are not familiar with are optional, but will serve as a handy reference for you when dealing with others who know those notations.

Part III introduces the new way of thinking about data and semantics that is the essence of this book and of the Concept and Object Modeling Notation. Make sure you’ve read part I carefully before starting on Part III.

Part IV walks through a realistic data modeling example, showing how to apply COMN to represent the real world, data design, and implementation. By the time you finish this part, you should feel comfortable applying your COMN knowledge to problems at hand.

Each chapter ends with a summary of key points and a glossary of new terms introduced. There is a full glossary at the end, along with a comprehensive index. In addition, an Appendix provides a quick reference to COMN. You can download the full reference and a Visio stencil from http://www.tewdur.com/. This will enable you to experiment with drawing models of your own data challenges while you read this book.

Each person who picks up this book comes to it with a unique background, educational level, and set of experiences. No book can precisely match every reader’s needs, but this book was written with the following readers in mind in order to come as close as possible.

NoSQL Database Developer

You might be someone excited to use the newest NoSQL database management software, but are aware of pitfalls that can hamper the performance and/or flexibility of NoSQL database designs. You may have found that established data modeling notations, such as E-R, fact-based, or the UML, can’t be used directly for NoSQL designs, without at least some non-standard extensions. This book will teach you COMN, which can express your NoSQL designs precisely enough to be used in model-driven development.

You might be surprised to find that the most difficult problems to solve in database design are logical and not physical. Since the differences between NoSQL and SQL databases are mostly physical and not logical, the bulk of this book is focused on enabling you to think through the logical design of data apart from physical considerations, and then to step through the process of physical database design while remaining faithful to the logical design. Make sure you read part I carefully, then dig into part III and learn these techniques. We’ll cover the differences between NoSQL and SQL in chapter 17. If you have a software development background, you should also read chapter 9 on object-oriented programming languages.

SQL Database Developer

You might be an experienced developer of SQL databases who always created designs directly in SQL, or used your own informal or home-grown data modeling notation—perhaps on a whiteboard or the back of a napkin—before you dove into specifying primary keys, indexes, partitions, and constraints. You’re intrigued by the idea of data modeling, or you just want to know if there’s something you’ve been missing. This book will teach you how to think about data at a logical level, before those critical physical design decisions come into play. Read part I carefully, then all of part III. We’ll get to the physical issues where you’re already an expert in chapter 17.

Data Modeler

You might be an experienced data modeler, already using an E-R or fact-based modeling notation, or the UML, to design your databases. But there are some niggling design problems that you always felt should not be so hard to tackle. Or, you might want to fold semantics into your data models but aren’t sure how to do that. You’ll find that learning COMN will build on the data modeling knowledge you’ve already acquired, and expand how far you can use that knowledge to include NoSQL databases, semantics, and some aspects of software development. Make sure you read part I, then the relevant chapters in part II, before you dig into part III and learn how to think differently about data and data models. After you’ve learned COMN, you’ll find that much of the advice on data modeling you’ve already learned is still valuable, but you’ll be able to apply it much more effectively than before.

Software Developer

You might be a software developer who knows that there’s more to data than meets the eye, and has decided to set aside some time to think about it. This book will help you do just that. Make sure you read part I, then chapter 9 on object-oriented programming languages. Chapter 9 will be especially relevant for you, as it will draw connections between data and the object-oriented programming that you’re already familiar with. If you design software with the Unified Modeling Language (UML), you should also read chapter 6.

Ontologist

You’ve begun to apply semantic languages like OWL to describing the real world. However, you find the mapping from semantics to data tedious and also incomplete. It’s difficult to maintain a mapping between a model of real-world things and a model of data. COMN is a tool you can use to express that mapping. Make sure you read part I carefully, and chapter 8 on semantic notations, before continuing on to part III.

|

Key Points

|