|

|

In the previous chapter we have seen how very basic types, such as integer types, are simple—having no components—but classes describing software objects are always composite. In this chapter we will dig into types that have components—so-called composite types—which actually dominate the work of data modeling.

Composite Types as Logical Record Types

A COMN model may show a composite type as a simple dashed rectangle without crossing lines through it, or it may show the details of the composition of the type using a dashed rectangle with three sections, in a manner very similar to the UML’s three-section rectangle showing the name, components, and methods of a class.

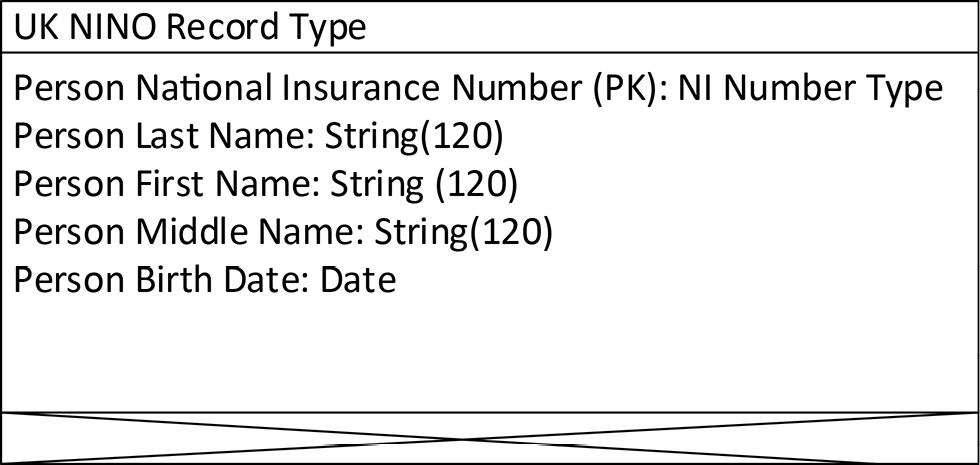

Figure 12-1 uses a rectangle with three sections to illustrate a hypothetical design for a record for the United Kingdom Department for Work and Pensions to keep track of National Insurance Numbers (NINOs) and the people to whom they are assigned. The top section of the rectangle contains the name of the type. The middle section contains the components of the type, often called its data attributes.

Figure 12-1. UK NINO Logical Record Type

The name of the first component of the UK NINO Record type, the Person National Insurance Number, is followed by the letters “PK” in parentheses. This means that it is a component (in this case, the only component) of the primary key of the record type. A key is a component or set of components whose values are always unique in any set of records of the type. Without a key, records in a set of records can be difficult or impossible to distinguish from each other.

The bottom section of the rectangle has lines crossing through it. This notation asserts that this type has no methods. When a composite type has no methods, it does not encapsulate its components. They are visible and directly manipulatable by all. Now, encapsulation is incredibly valuable. By controlling what routines can access or modify the component objects of a software object, encapsulation makes software much simpler, therefore easier to write and easier to avoid generating bugs in the writing. Encapsulation has led to a significant increase in the reliability of software, and a concomitant decrease in the cost of software development. But upon reflection, one realizes that the value of encapsulation is related to the encapsulation of mechanisms. We want to limit the routines which can operate the internal mechanisms of an object. But in the case of data, we actually want data to be visible to others—we don’t want to hide it as we want to hide internal mechanisms. “Information hiding” a là David Parnas [Parnas 1972] should be about hiding information about mechanisms, not about hiding information per se.

So, when we define a logical record type, we typically don’t define any particular methods. We might do so at a higher level than an individual logical record type. For example, we might have a higher-level type that references several different record types, and that provides mechanisms to manipulate groups of records of those various types in ways that ensure that their values remain consistent with each other. By encapsulating access to groups of related records of different types, and allowing only the methods of the encapsulating type to access them, we achieve all the benefits of encapsulation, without forcing the overhead of encapsulation on the very methods designed to manipulate instances of those record types. We also enable powerful relational operations (see chapter 16) which are not possible on encapsulated data. This form of composition of records and objects through reference is composition by assembly.

Types Representing Things in the Real World: Identification

It is very common, and fundamental to data modeling, to use types of values to represent types of things in the real world. Consider an identifier: a number or alphanumeric string assigned within a computer system to identify a real-world object. The example in the previous section mentions the UK National Insurance Number (two letters, six digits, one letter), which is used to identify people. Other countries have their own national identifiers, such as the US Social Security Number (a 9-digit decimal number). Drivers’ license numbers also represent people, though a slightly different set of people than national identifiers do; namely, those licensed by some state or nation to drive vehicles. Lottery tickets are identified by numbers. Houses on streets are usually identified by numbers assigned by a postal authority. Individual automobiles are identified by Vehicle Identification Numbers (VINs) assigned at the time of manufacture. And so on.

We can diagram in COMN exactly how identification works. Figure 12-2 shows that same logical record type for UK national insurance numbers, but now it’s shown connected to a collection of records, through that collection to the real-world persons that the records are about, and to the NI Number type.

Figure 12-2. UK NINO Logical Record Type with Related Types

We’ve seen rectangles in COMN before, but the UK Person Type rectangle is drawn differently: it has a solid bold outline. A solid outline indicates that the type represented designates objects, not concepts, and people are material objects, because they can be perceived by the senses. The bold outline indicates that these objects exist in the real world and not in the computer. A person is a material object but not a computer object. We named this type UK Person Type because it’s not the type of all persons, but only the type of persons known to the UK Department for Work and Pensions.

In between the UK NINO Record Type and the UK Person Type we have a dashed hexagon with a shadow labeled the UK NINO Record Collection. A dashed hexagon is the COMN symbol for a variable, and the unadorned line connecting it to the UK NINO Record Type tells us that that is the type of the variable. The shadow indicates a collection, so the shadowed hexagon represents a collection of variables. Since we’re focused on logical data design and not implementation, we haven’t decided yet whether the collection will be represented by a table in a SQL database, a collection of documents in a NoSQL document database, or something else. In any case, we think of this collection of records as a collection of variables, where each variable has the UK NINO Record Type. Each variable will eventually be a table row, a document, or something similar.

The representation line from the UK NINO Record Collection to UK Person Type indicates that the record collection represents the UK Person type. This means that each value of a record in the UK NINO Record Collection represents a UK Person. Since we know that the key of a UK NINO Record—the Person National Insurance Number—is always unique, we know that in fact it is the Person National Insurance Number that represents, or identifies, a UK Person.

It is not true that every NINO identifies a UK Person. It is only a NINO that has been assigned to a person, as recorded in a UK NINO Record, that identifies a UK Person. This is where the NI Number Type on the right of Figure 12-2 comes in. The NI Number Type designates the full set of NINO numbers, whether assigned or not. The full set is defined as all those strings of characters starting with two letters, then six decimal digits, and finally one suffix letter, minus certain prohibited combinations as defined by the UK Department for Work and Pensions. NINOs to be assigned to people must be drawn from this set.

Let’s look more closely at the relationship from the UK NINO Record Type to the NI Number Type. The definition of the UK NINO Record Type includes a component, the Person National Insurance Number, whose type is NI Number Type. The UK NINO Record Type incorporates the NI Number Type by aggregation; in other words, the NI Number Type is part of the UK NINO Record Type and can’t be separated from it, although it remains a recognizably separate part. The line with the solid arrowhead pointing from the UK NINO Record Type to the NI Number Type indicates this. As is standard in COMN notation, arrowheads always point in the direction of reference. The UK NINO Record Type mentions the NI Number Type, and not the other way around.

We can now see that we have two subtly different sets of values that have two different functions. The NI Number Type designates a set of strings of characters in a certain format. The UK NINO Record Collection includes a subset of all possible NI Number Type strings, specifically only those NI Number Type values actually assigned to identify persons. This subset of NI Number Type values is what represents or identifies the UK Person Type.

In striving toward our goal of efficient development of reliable systems, both the UK NINO Record Type and the NI Number Type are valuable. The NI Number Type can be used at points of data entry to ensure that character strings entered as purported NINOs are at least in the right format, whether or not they are assigned to anybody. This level of type checking is a valuable first line of defense in ensuring high data quality, and might be all that’s possible if access to the UK government’s authoritative NINO database isn’t readily available. To be really sure that a NINO identifies a UK Person, one must look in the authoritative UK NINO Record Collection to find a matching value there.

In place of the logical record type rectangle, the record collection shadowed hexagon, and the UK Person type rectangle, an E-R data model would show a single rectangle. In an E-R data model the rectangle would be called an “entity”, but it would in fact represent three things simultaneously: the record type, the actual collection of records, and the real-world objects represented by the identifiers on the records. An equivalent model could be drawn in COMN using a single shadowed hexagon with components recorded directly in it, as long as the details of the representation relationships were not important—and we will do exactly this in chapter 13. But for the representation of reusable composite types such as measures, this separation is essential. We will also see in chapter 15 how separating the three things can give us important insights to our data.

Stepwise Refinement and Completeness

Perhaps you’ve seen a pattern as to how COMN can be used to depict varying degrees of detail in a model. A type or class may be depicted as a simple rectangle containing nothing more than its name, or it may be expanded and divided into three sections so that its components and methods may be shown. When components are shown, their types or classes may also be shown. A type or class that is referenced by another type or class may optionally be added to a diagram, whether or not the referencing types or classes are drawn with three sections, calling out their components and their types by name, or just one section.

However, if a type or class is added to a diagram, then every relationship it has to other types or classes on the same diagram must be drawn. This principle, which is called the completeness principle, is essential, because if drawing relationship lines were optional, one could never know from a COMN drawing whether what it depicted was complete. The fact that two types were on the same drawing but without relationship lines between them could not be taken as indicating that they were not directly related. The completeness principle lets the reader know without any doubt whether any two types on a drawing are related or not. It also leads to a strategy for laying out large models such that limits on clutter require subdividing diagrams into clusters of closely related types. This makes for more readable and more logically organized models.

This flexibility in showing varying levels of detail enables an analyst or designer to approach a modeling problem a little bit at a time. One can start by drawing the simple rectangles for composite types that aren’t split into three sections. One can gradually add additional rectangles to show relationships to other types and classes, and perhaps hexagons to show instances of data and objects relating to those types and classes. Finally, one can begin to expand some of the type and class rectangles to show details of their components and methods. This approach to modeling is called stepwise refinement, where the high-level details of a design are first captured, and then additional details are gradually added, until the model is complete. Unlike with E-R modeling, a COMN model supports stepwise refinement at every level of abstraction—conceptual, logical, and physical—without changing models or model types. A suitable modeling tool would enable one to alter the level of detail displayed dynamically, after the details had been added, and to separate a model into diagrams showing just the parts relevant to a particular subject or audience.

Types Representing Other Types

It is very common—and fundamental—that we use values to represent other values. As an example, let’s look at good ole’ ASCII, that character set and encoding that is foundational to all computer-to-computer and computer-to-human communication.

The American Standard Code for Information Interchange, or ASCII, has two parts, as shown in Table 12-1:

- a set of 95 graphical characters that can be printed on paper and used to express human-readable text, plus a set of 33 so-called “control characters” that are useful for computer-to-computer communication

- integers in the range 0 to 127, each of which is used to represent one of the 128 characters described by ASCII

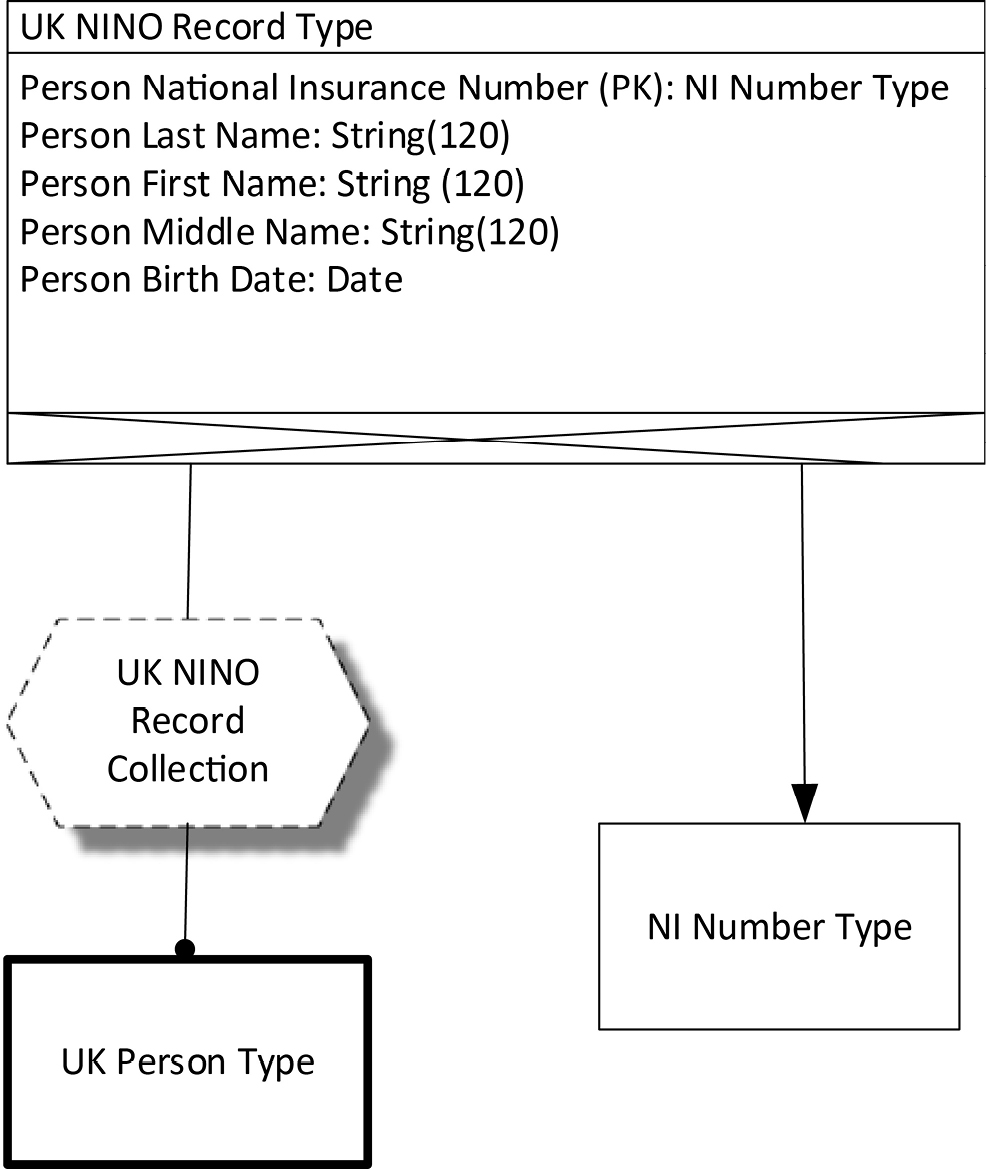

Figure 12-3 shows the ASCII encoding expressed in COMN. The type being represented is named ASCII Character, and designates the set of characters given in Table 12-1. The ASCII Character rectangle has lines crossing through it because an ASCII character has no components, even though its representations have components. The type doing the representing is called ASCII Type, and is a composite type with one component. The component is called Ordinal. It is an integer in the range of 0 to 127 that corresponds to one of the 128 ASCII characters.

ASCII Type encapsulates its component. Only its methods can access the integer variable in order to manipulate it. In this way ASCII Type can make sure that the integer is manipulated only in ways that make sense given that it represents a character and not an integer. For instance, although one can multiply two integers together, it makes no sense to multiply two ASCII characters together, so ASCII Type does not offer a multiplication method. It is possible, however, to flip alphabetic letters between upper case and lower case. ASCII Type has methods toUpper and toLower that can manipulate the integer component Ordinal in ways to make this happen. These methods and others are shown in the bottom section of the ASCII Type rectangle.

|

0 |

NUL |

16 |

DLE |

32 |

SP |

48 |

0 |

64 |

@ |

80 |

P |

96 |

` |

112 |

p |

|||||||

|

1 |

SOH |

17 |

DC1 |

33 |

! |

49 |

1 |

65 |

A |

81 |

Q |

97 |

a |

113 |

q |

|||||||

|

2 |

STX |

18 |

DC2 |

34 |

“ |

50 |

2 |

66 |

B |

82 |

R |

98 |

b |

114 |

r |

|||||||

|

3 |

ETX |

19 |

DC3 |

35 |

# |

51 |

3 |

67 |

C |

83 |

S |

99 |

c |

115 |

s |

|||||||

|

4 |

EOT |

20 |

DC4 |

36 |

$ |

52 |

4 |

68 |

D |

84 |

T |

100 |

d |

116 |

t |

|||||||

|

5 |

ENQ |

21 |

NAK |

37 |

% |

53 |

5 |

69 |

E |

85 |

U |

101 |

e |

117 |

u |

|||||||

|

6 |

ACK |

22 |

SYN |

38 |

& |

54 |

6 |

70 |

F |

86 |

V |

102 |

f |

118 |

v |

|||||||

|

7 |

BEL |

23 |

ETB |

39 |

‘ |

55 |

7 |

71 |

G |

87 |

W |

103 |

g |

119 |

w |

|||||||

|

8 |

BS |

24 |

CAN |

40 |

( |

56 |

8 |

72 |

H |

88 |

X |

104 |

h |

120 |

x |

|||||||

|

9 |

TAB |

25 |

EM |

41 |

) |

57 |

9 |

73 |

I |

89 |

Y |

105 |

i |

121 |

y |

|||||||

|

10 |

LF |

26 |

EOF |

42 |

* |

58 |

: |

74 |

J |

90 |

Z |

106 |

j |

122 |

z |

|||||||

|

11 |

VT |

27 |

ESC |

43 |

+ |

59 |

; |

75 |

K |

91 |

[ |

107 |

k |

123 |

{ |

|||||||

|

12 |

FF |

28 |

FS |

44 |

, |

60 |

< |

76 |

L |

92 |

\ |

108 |

l |

124 |

| |

|||||||

|

13 |

CR |

29 |

GS |

45 |

- |

61 |

= |

77 |

M |

93 |

] |

109 |

m |

125 |

} |

|||||||

|

14 |

SO |

30 |

RS |

46 |

. |

62 |

> |

78 |

N |

94 |

^ |

110 |

n |

126 |

~ |

|||||||

|

15 |

SI |

31 |

US |

47 |

/ |

63 |

? |

79 |

O |

95 |

_ |

111 |

o |

127 |

DEL |

On the far right we show the integer type of the Ordinal component of ASCII Type, but this is for illustration purposes only. The model is complete without this rectangle.

Since ASCII Type is a type and not a class, no storage allocation has been specified. We need a class before there’s anything to implement in a computer. A class implementing ASCII Type would quite reasonably store each character code in a byte, but the methods of the class would limit the byte to entering only 128 of its 256 possible states. The other 128 states would have no meaning in this usage. If we wished to show this level of detail, we would draw a class that represents the ASCII Type, and show that its only component is an integer class having a byte component.

Measures as Composite Types

We’ve seen how composite types can be used to represent other types. Now we’ll look at how composite types can be used to express measures. A measure is a combination of a number giving a count, quantity, or amount, and a type of thing that is being measured. Here are some example measures:

- 5 kilograms

- 2 cups

- $39, or USD 39

- 20 million people (perhaps the population of a metropolitan area)

- 1.9 children (perhaps the average number of children in a family)

We are used to units of measurement being related to space (for example, distance or volume) and time (for example, seconds or days), but in fact measures apply to anything that can be counted or measured.

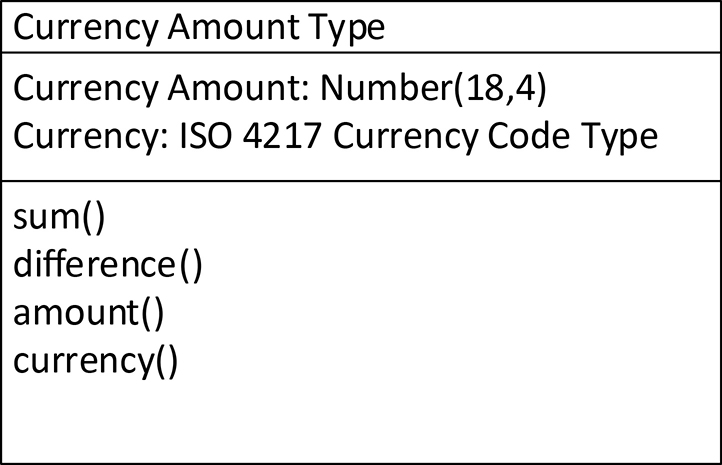

A measure can be modeled as a composite type with two components. For the sake of illustration, let us consider a measure of currency, where the number component is a decimal number to five decimal places, and the currency is identified by a 3-character ISO 4217 currency code. See Figure 12-4.

Figure 12-4. A Measure of Currency

A measure is a very special thing, because it encapsulates a multiplicative relationship between a numeric measure (in this case, the Currency Amount) and a type of things that’s being measured or counted (in this case, Currency). In other words, “5 kilograms” really means “5 x kilogram”, and “$39” really means “39 x USD”. Because of this, not all of the operations valid on plain numbers are valid on measures. For instance, it is only valid to add or subtract two currency measures together if they are measures of the same currency. Multiplying two currency measures together probably makes no sense, although multiplying measures of physical units is quite sensible and yields measures of different types; for example, multiplying distance by weight yields energy. Because of this, encapsulating the two components of a measure and providing methods that only allow correct operations on the measure provides a higher level of correct operation than if the two components remained unencapsulated.

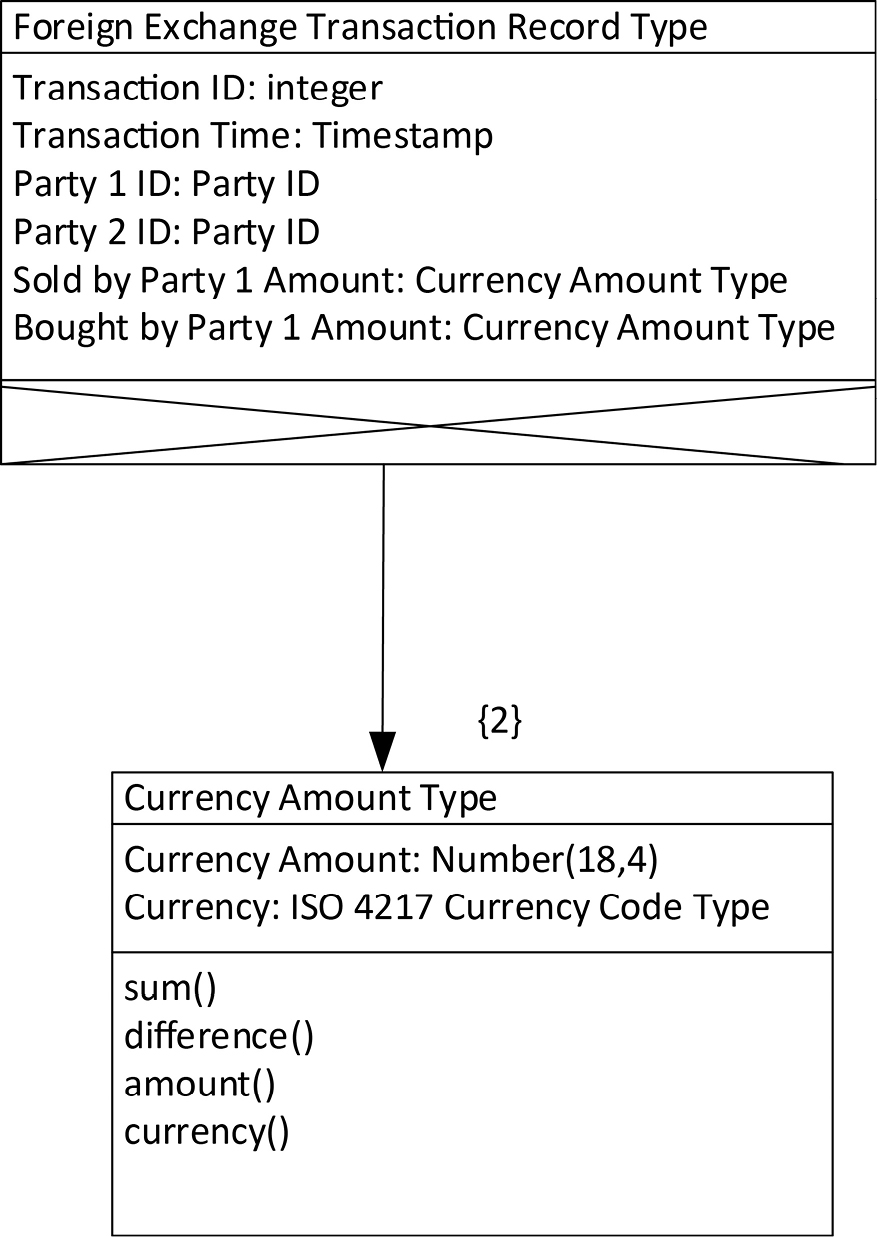

Composite types, including measures, are wonderful as units of reuse. The structure of a composite type can be specified just once and reused in hundreds of places without modification, enabling the original design to be carried through to many unrelated designs— just as standardized parts in manufacturing enabled the industrial revolution. A composite type can also be used to express an organizational decision to use that structure as a standard. Let’s look at a foreign exchange transaction. In a foreign exchange transaction, one party “sells” or gives up some amount of a certain currency, in exchange for some amount of a different currency. The other party is the mirror image: that party “buys” the currency being given up by the first party, by supplying the requested amount of the different currency. This is exactly what happens if you travel from continental Europe to the United Kingdom and “buy” British pounds with your euros, or if you cross from the United States to Canada and “buy” Canadian dollars with your America dollars.

The design for a logical record type of a foreign exchange transaction is depicted in Figure 12-5. Its first component is a simple integer Transaction ID, enabling us to distinguish transaction records from each other. Next we have a date and time on which the transaction took place, as a variable whose type is “timestamp”. We have two identifiers that identify the parties to the transaction. Finally, we have two variables: Amount Sold by Party 1 (which is bought by Party 2) and Amount Bought by Party 1 (which is sold by Party 2). These two variables have the same type, which is the Currency Amount Type introduced earlier. The number “2” near the aggregation arrowhead indicates that the Currency Amount Type has been included in the Foreign Exchange Transaction Record Type twice.

Figure 12-5. A Foreign Exchange Transaction Logical Record Type

By re-using the Currency Amount Type, the designer of the Foreign Exchange Transaction Record Type does not have to define four variables as components of Foreign Exchange Record, but only two. The designer does not have to look up how many decimal digits the organization wishes to use when recording currency amounts. That standard has already been built into the Currency Amount Type, and the designer merely has to reference the composite type in order to incorporate that standard. Finally, the names of the two variables reflect their role in the record type, and aren’t lengthened or complicated by the names and types of the individual components of Currency Amount Type. All these benefits are in addition to the additional type safety gained by encapsulating the components of the measure.

In a large or even a medium-sized enterprise, there are typically hundreds of composite types that need standardization and thousands of opportunities to re-use those standard types. Examples of such composite types include postal addresses, personal names, telephone numbers, and various identifiers: the list could go on for quite some time. Most data modeling notations either can’t express reusable composite types, or can but insist that their components always be encapsulated. (For the reasons why, review the relevant chapters in part II). In COMN, expressing these things is straightforward.

Incidentally, the world of database design has standardized on names to use with measures, to make it easier to judge from the name of a component what it indicates. Conventional use will make sure that a measure’s name ends in one of the three words count, quantity, or amount, as follows:

- count: an integral number of things that are counted; for example, Access Attempt Count

- quantity: a possibly fractional number of things that are measured, not counted, including the result of statistical functions on counts; for example, Order Item Quantity, Average Children Per Family Quantity, Fuel Capacity Gallon Quantity, Distance Kilometer Quantity

- amount: a quantity of some currency; for example, Price Amount

Nested Types

Types that represent other types are only useful if they are incorporated into composite types as the types of some components. Measures are composite types that are most useful when incorporated into other composite types by aggregation, as the Currency Amount Type was incorporated twice into the Foreign Exchange Transaction Record Type.

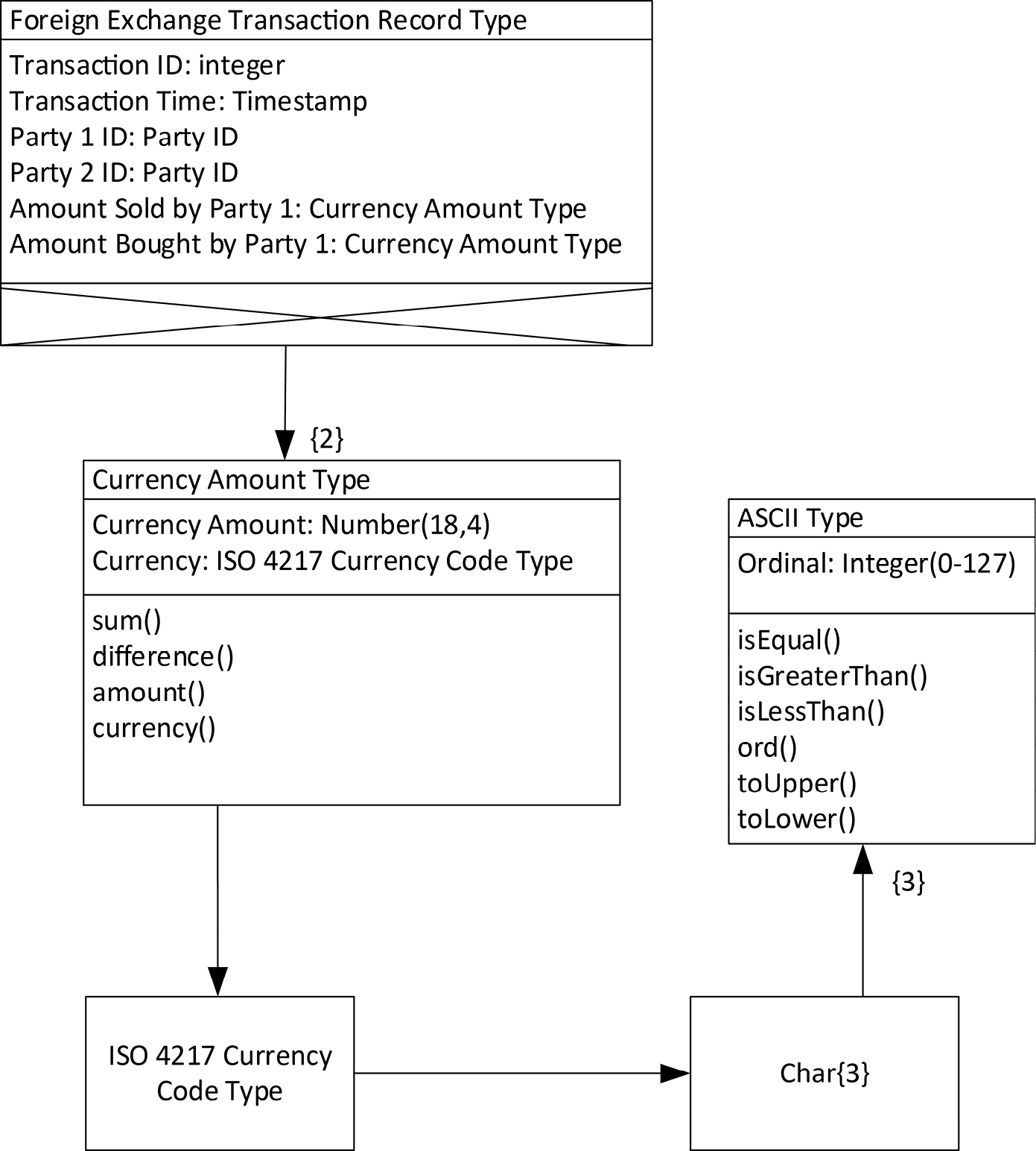

There is nothing that says that this composition by aggregation must be limited to a single level. It can go on for as many levels as are useful. We call this nesting of types. In Figure 12-6 below, we have nesting to four levels, as follows:

- ASCII Type is nested three times inside Char{3}.

- Char{3} is nested inside ISO 4217 Currency Code Type.

- ISO 4217 Currency Code Type is nested inside Currency Amount Type.

- Currency Amount Type is nested (twice) inside Foreign Exchange Transaction Record Type.

The Unified Modeling Language (UML) and object-oriented programming languages can express arbitrary nesting like this. The eXtensible Markup Language (XML) and JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) can express nesting. Entity-relationship models and SQL cannot express nesting. This is often blamed on the relational model, but chapter 16 will show that the limitation is in implementations, not relational theory.

One must be careful to consider that all of the types in question here are not classes. They say nothing about the layout of these types in storage. When one is focused on logical design, the goal is to create a model that most efficiently expresses requirements. It is only at the stage of physical design (discussed in chapter 17) that storage layouts should be considered. To read COMN types as entity-relationship’s “entities”, as SQL database tables, or as the UML’s classes, is to jump prematurely to the physical level and get tangled up in physical design decisions before the requirements are fully articulated.

Modeling Documents

Some vendors offer what they call “document databases”, which are presumably structured in such a way that they can efficiently store the electronic equivalents of what we would recognize in printed form as documents: contracts, tax forms, papers, even entire books. A document in this parlance is a composite type, and should be modeled in COMN as such. Documents often include nested types, and as we have just seen, these can be modeled in a straightforward manner in COMN.

The eXtensible Markup Language (XML) is a common form for exchanging documents in electronic form. See Figure 12-7 for a snippet of an XML document. The names enclosed in angle brackets are called tags, and constitute the markup of what is otherwise plain text. Most tags come in pairs with text between the start tag and end tag, and the whole construction is called an element. For example, in Figure 12-7 the plain text “Chapter 1” is surrounded by the start tag <title> and the end tag </title>. Elements can next. For example, the Chapter 1 title is nested inside a <chapter> element. The same <chapter> element also contains two <para> elements. The <chapter> element is nested inside the <book> element.

<?xml version=”1.0” encoding=”UTF-8”?>

<book xml:id=”simple_book” xmlns=”http://docbook.org/ns/docbook” version=”5.0”>

<title>Very simple book</title>

<chapter xml:id=”chapter_1”>

<title>Chapter 1</title>

<para>Hello world!</para>

<para>I hope that your day is proceeding <emphasis>splendidly</emphasis>!</para>

</chapter>

<chapter xml:id=”chapter_2”>

<title>Chapter 2</title>

<para>Hello again, world!</para>

</chapter>

</book>

Figure 12-7. An XML Document Snippet

An XML document is an instance of some document type—whether that type is articulated or not. An XML document’s type—the structure of its elements and the way in which they nest—might be expressed in a variety of schema languages, such as Document Type Definition (DTD), XML Schema, and RELAX NG (RNG). COMN notation can directly express exactly what these schema languages can express, with the same precision and without ambiguity, using nested composite types—something that cannot be done in E-R notations or in fact-based modeling.

JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) is a very simple language for expressing values. JSON is built around two kinds of composite structures: array and object. An array is a set of values which are distinguished solely by the order in which they appear, while an object is a set of values which are distinguished by their names. A unit of JSON text is called simply that: a JSON text. See Figure 12-8 for an example of a JSON text.

{

“firstName”: “John”,

“lastName”: “Smith”,

“isAlive”: true,

“age”: 25,

“address”: {

“streetAddress”: “21 2nd Street”,

“city”: “New York”,

“state”: “NY”,

“postalCode”: “10021-3100”

},

“phoneNumbers”: [

{

“type”: “home”,

“number”: “212 555-1234”

},

{

“type”: “office”,

“number”: “646 555-4567”

}

],

“children”: [],

“spouse”: null

}

As with XML, a JSON text may or may not have its type described by some other document using a schema language such as JSON Schema. As with XML, COMN can directly express exactly what a JSON schema language can express, using nested composite types—something that, again, cannot be done in E-R notations or in fact-based modeling.

JSON is often compared to XML as a more efficient language with the same expressive power. This is not quite accurate. The confusion has arisen because XML has been heavily used as a data interchange language, although that was not its original design intent. XML is a markup language, which means that it is focused primarily on adding annotations to human-readable text; those annotations are most often used to express the meaning or significance of the text that they mark up. In contrast, JSON is a language for expressing data, which might include human-readable text as data but not marked-up text in the same sense as XML. It is unfortunate that the term “document” is commonly used to describe a piece of JSON text. The JSON spec never uses that term, and simply refers to “a JSON text”.

Notwithstanding the confusion between “a JSON text” and “document”, COMN can be used to model a JSON text’s type as a composite type.

Arrays

An array is a special kind of composite type. It consists of some non-negative integral number (possibly zero) of variables all of a single type. Each variable is called an element of the array. The entire collection of variables is known by the name of the array, and each element within the array is identified by an integer known as its element number or index.

An array type is defined by the element type plus the range of possible numbers of elements that may be possessed by a variable of the array type. The possible numbers are called the multiplicity of the array. (The actual number of elements in any particular array variable or value is called its cardinality.) Here are some example array multiplicities and the COMN notation for expressing them:

- a plus sign (“+”), indicating that one to any integral number of elements may occur

- an asterisk (“*”), indicating that zero to any integral number of elements may occur

- integer expressions enclosed in a pair of curly braces(“{“ and “}”) giving the possible numbers of elements. The expressions can take the following forms:

- a single positive integer, indicating exactly that many elements will occur; for example, “{3}”

- a range of integers specified as two non-negative integers separated by a hyphen; for example, “{0-2}”

- a comma-separated list of non-negative integers giving allowable numbers of elements; for example, “{0, 2, 4, 6}”

- any combination of number ranges and non-negative integers; for example, “{0, 2-5, 9}”

Arrays can be represented in COMN diagrams in two ways:

- When a type or class is depicted with a rectangle having three sections, the multiplicity of a component can be indicated using one of the above expressions after the element’s type.

- When one type or class is composed of another by either aggregation or assembly, the arrowhead pointing to the element type or class may have a multiplicity expression next to it, at the element type end.

One kind of array we can’t live without is the character string. We’ve already seen a three-character array type, Char{3}, as a component of the ISO 4217 Currency Code Type. It is quite common to use variable-length character strings to represent human-readable text in various contexts. For example, you might see character string components defined like this:

- Person Last Name: ASCII Type{1-200}

- Product Name: Unicode Type{1-1000}

- Postal Code: Unicode Type{2-50}

These simple arrays are heavily used in data design. However, an array’s element type can be of arbitrary complexity. We can have arrays of measures (perhaps a series of sensor readings), arrays of records (hmm, that sounds like a table!), and, since an array is a composite type, we can have arrays of arrays if we find that useful.

|

Key Points

|

Chapter Glossary

logical record type : a composite type that is intended to be used as the type of data records stored singly or in a collection of records

measure : a composite type consisting of a number and a type of thing being measured or counted

identifier : any value that represents exactly one member of a designated set

array : a collection of some integral number of variables or objects of the same type or class

References

[Parnas 1972] Parnas, D. L. “On the Criteria to be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules.” Communications of the ACM, 15, 12. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 1972, pp. 1053-1058.