|

|

Recall from chapter 2 that we have restored the words entity, object, and concept to their ordinary English meanings—meanings that these words possessed for centuries before computing machines were even imagined, let alone constructed. For your reference, here are the definitions again that give those meanings, all of which are quoted from Merriam-Webster’s Online Dictionary.

entity 2 : something that has separate and distinct existence and objective or conceptual reality

object 1a : something material that may be perceived by the senses

concept 1 : something conceived in the mind : thought, notion

In this chapter we will take steps toward using these ordinary English words to describe software and data, but without distorting their ordinary meanings. It is the distortions that have made it so difficult for us to think clearly about real-world problems and their solutions in computer systems.

We will go down to a very low level of abstraction, specifically the level of computer hardware. We don’t want to stay there, because designing data one storage location at a time or developing software one computer instruction at a time is a laborious and inefficient way to work. But we do have to glance at this basement level, because that’s where the foundation is. Understanding that everything rests on very physical objects and their very physical states gives the more abstract things we do a solid foundation.

If you are familiar with any of the notations or languages discussed in part II of this book, make sure you refer frequently to the relevant terminology maps at the end of each chapter in part II, to keep your mind clearly focused on the simpler, more natural terminology of COMN.

Material Objects

Figure 10-1 below shows a fundamental example of an object in the ordinary English sense of the word “object”. The object pictured is a rock. It is certainly material, and it can certainly be perceived by the senses.

Figure 10-1. A Rock; a Material Object

Admittedly, a rock is not a very interesting object. A more instructive example of a material object is a flashlight, or electric torch. See Figure 10-2 below.

Figure 10-2. A Flashlight; a Material Object

From this point onwards, unless it is already clear from the context, I will qualify the word “object” with the adjective “material” to mean an object in the natural language sense.

Objects with States

Let us consider the flashlight’s characteristics. It is an object in the same sense that a rock is an object, because it can be perceived by the senses: you can see it—even when it’s off—and touch it.

However, a flashlight is interesting for more than its capability to be seen and touched. A flashlight can be turned on and off. We describe this capability by saying that the flashlight can hold a state. A flashlight has a built-in mechanism for changing its state from off to on and back to off: it’s a switch. (In the commonly accepted terminology of computer science, mechanisms built into an object to change its state are called methods—but then we’re getting ahead of ourselves.)

In contrast to the flashlight, the rock has no states—at least not in the sense that the flashlight has states. More precisely, the rock is in a single state (solid), and offers no mechanisms of its own for changing that state. We call objects like the flashlight stateful, while we call objects like the rock stateless.

In summary, then:

- A material object is an object in the natural-language sense of the word; in other words, something you can see and touch.

- Some objects have states and methods to change those states (for example, a flashlight), and some do not (for example, a rock).

- Objects capable of having more than one state are called stateful. Objects having only one state are called stateless.

Meaning of States

Some material objects have states with intrinsic meaning. Consider the lighted sign in Figure 10-3.

This stateful material object does have intrinsic meaning. If this sign is over a doorway to a studio, and it is lit, then it indicates that there are live microphones inside the studio transmitting all sounds to a recording device. This object has two states and two meanings, and the meanings are fixed to the states.

In contrast, consider the flashlight again. I have conducted a fun little experiment with several groups of people. I hold a flashlight in front of the group, and, without any other preamble, ask everyone in the group to call out the state of the flashlight as it changes. I then begin to operate the flashlight’s switch, and everyone dutifully calls out, in unison, “on … off … on … off”.

I then stop the experiment and tell everyone that this time I want them to call out, not the flashlight’s state, but rather its value. As I begin to operate the switch, unanimity is gone. I still hear a few calling out “on … off”, but then I hear some calling out “one … zero” (those are the programmers), some calling out “useful … useless”, some calling out “light … dark”, and some saying nothing except by the confused looks on their faces.

The point is this: There is widely accepted nomenclature for the states of a flashlight (on and off), and no explanation is needed in order for a person familiar with natural language to name each state. But there is not such a widely accepted nomenclature for the values of these states. That is because state and value are very different things. At least in the case of a flashlight, meanings must be assigned to the states—or not: if one wishes to use the flashlight simply to see in the dark, no assignment of meaning is required.

In summary, we have learned the following about objects and their states:

- The states of some objects have intrinsic meaning, while the states of other objects have no intrinsic meaning.

- It is not always necessary to assign meanings to the states of an object in order for the object to be useful.

Objects with More States

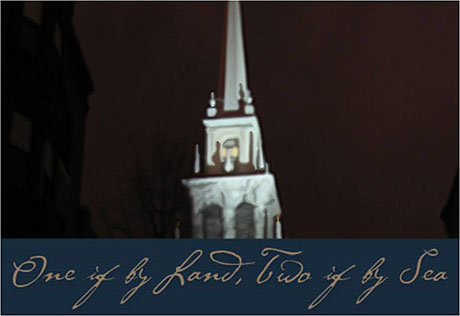

Next let us consider a slightly more complex object than a flashlight or a lighted sign. Consider an important stateful object from the history of the American Revolution: the Old North Church in Boston, Massachusetts.

Figure 10-4. The Old North Church in Boston, Massachusetts, US

On the night of April 18, 1776, the American revolutionaries in Massachusetts learned that British soldiers were going to leave Boston the next day and march to the towns of Lexington and Concord, in order to confiscate the guns and ammunition cached there. The revolutionaries wanted to alert the towns along the route to be ready for the incursion. However, they were not absolutely sure of the route, because they did not know whether the soldiers would leave the Boston peninsula by boat, or march up the peninsula to the mainland. The plan was that when Robert Newman, the sexton of the Old North Church, learned of the route, he would signal it by carrying lighted lanterns up to the church tower: one lantern would signify the land route, and two lanterns would signify the route across water. Robert Newman placed two lanterns in the tower, indicating that the soldiers were coming “by sea”.

Thus, on the evening of April 18, 1776, the tower of the Old North Church was used as a stateful object, with the following states and meanings:

- no lanterns: information unavailable

- one lantern: the soldiers were coming by land

- two lanterns: the soldiers were coming by sea

The advantage of this system of signaling was that, although anyone could observe the state of the church tower (no lanterns, one lantern, two lanterns), only those who knew the values assigned to each state could interpret and act upon the signal. The revolutionaries could communicate secretly to each other even though the soldiers could see the signals, because only the revolutionaries knew the meanings of the signals.

Even More States

Let us consider a hypothetical modification of the Old North Church tower. Suppose that two lanterns were permanently affixed in the tower, and Robert Newman were to signal by lighting one or two lanterns. Then the states of the church tower would have meanings as follows:

- neither lantern lit: information unavailable

- the first lantern lit, the second lantern unlit: the soldiers were coming by land

- the first lantern unlit, the second lantern lit: the soldiers were coming by land

- both lanterns lit: the soldiers were coming by sea

Now we have four states, but only three meanings! From this we learn that

- We sometimes have stateful objects with more states than meanings.

Methods

Object-oriented technologists talk much about methods, which, in terms of material objects, are mechanisms that are part of those objects that enable one to change their states. Let us consider the methods that are part of the material objects we have considered so far.

- rock: no methods (which makes sense, since it has but one state)

- flashlight: one method, the on-off switch

- lighted sign: a method to turn the sign on or off

- Old North Church: a method to light either lantern

Just to keep you nimble, here is one more material object to consider: a tricycle.

This is a material object that definitely incorporates a mechanism, namely pedals attached to the front wheel. Yet one can see that operation of this mechanism does not change the state of the tricycle: no particular position of the pedals has any significance over any other positions. We thus learn that

- Some material objects have methods but not states.

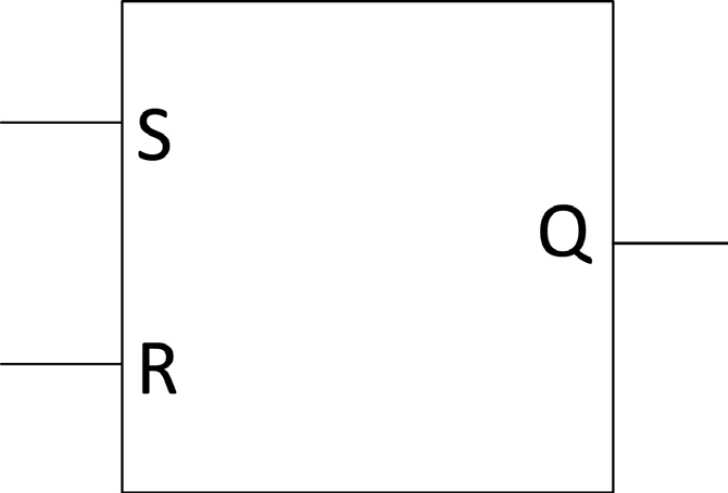

Material Objects in Computers

Digital computers are composed of vast arrays of a single kind of material object called a flip-flop. A flip-flop is a small electronic device built to hold one of two states at any time (either flip or flop, so to speak), and having methods to change the flip-flop from one state to the other. See Figure 10-6 for a symbol representing a flip-flop. The state of a flip-flop can be observed by checking the voltage on a wire labeled Q. This voltage might be high (not very high; typically about 3 volts or the same as two AA batteries tied together) or low (that is, about 0 volts). The input labeled S is used to set the flip-flop to a high-voltage state, and the input labeled R is used to reset the flip-flop-to a low-voltage state. This kind of flip-flop is called an R-S flip-flop, after its two inputs.

Figure 10-6. A Symbol Representing an R-S Flip-Flop. A Computer’s Memory Is Made of Billions of These.

The vast majority of the flip-flops in a computer—those composing the so-called main memory of a computer—have no predefined significance, and are specifically designed so that their states can be assigned different meanings at different times. It is this ability to assign and re-assign meaning to states that gives rise to the great utility of digital computers to process a wide variety of information.

When electronic circuit designers are dealing with flip-flops, they avoid even the appearance of assigning meaning to the two states. They simply name the two states H and L, for high-voltage and low-voltage, respectively. It is irrelevant to the designer of a memory circuit whether the H state is called one and the L state is called zero, or vice-versa. After all, the user of the memory may eventually call the H state “green” and the L state “red”, or the H state “stop” and the L state “go”: the possibilities are endless.

Despite all this care that electrical engineers take to avoid the appearance of meaning, once the memory chip has left their care, it is very common for users of the chips to assign the number zero to one state (perhaps the H state; perhaps the L state) and to assign the number one to the other state. These two numbers, zero and one, become the standard names for the state of a flip-flop in a computer’s memory, and we don’t need to know or care about voltages. But it is important to remember that those abstract values zero and one are represented by the meaningless physical states of material objects; specifically, the high- and low-voltage states of R-S flip-flops.

Flip-flops in a digital computer are more often used in combination with each other than singly. In fact, computers usually make memory available only in groups of eight flip-flops called bytes. Each of the eight flip-flops has two states, so a byte has 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2, or 28, or 256, states.

If we look at each of the eight flip-flops in a byte as representing a binary digit or bit, then we can think of a byte as representing an 8-digit binary number. Eight binary digits can represent numbers in the range from zero to 255. Now we can refer to each of the 256 states of a byte with a number.

With regard to the material objects found in computers called flip-flops, we have learned that:

- For practical purposes, the meaningless physical states of material objects are often numbered. The states of objects with two states are often numbered 0 and 1.

- For different purposes, at different times we may assign different meanings to the same states of an object.

- Objects are often combined into a composite object. In general, the composite object has a number of states which is the product of the number of states of its component objects.

Summary

In summary then,

- A material object is an object in the natural-language sense of the word; in other words, something you can see and touch.

- Some objects have states and methods to change those states (for example, a flashlight), and some do not (for example, a rock).

- Objects capable of having more than one state are called stateful. Objects having only one state are called stateless.

- The states of some objects have intrinsic meaning, while the states of other objects have no intrinsic meaning.

- It is not always necessary to assign meanings to the states of an object in order for the object to be useful.

- We sometimes have stateful objects with more states than meanings.

- Some material objects have methods but not states.

- For practical purposes, the meaningless physical states of material objects are often numbered. The states of objects with two states are often numbered 0 and 1.

- For different purposes, at different times we may assign different meanings to the same states of an object.

- Objects are often combined into a composite object. In general, the composite object has a number of states which is the product of the number of states of its component objects.

Computer Object Defined

When using the term “object” in any context within computer science or technology, we will use the following definition.

computer object: a stateful material object whose state can be read and/or modified by the execution of computer instructions

If context makes it clear that a computer object is meant, the modifier “computer” will often be dropped.

A computer object is a material object that has two distinct qualities beyond those possessed by most material objects:

- A computer object is a stateful mechanism. This means that it has two or more possible states, and means for changing those states.

- A computer object’s state may be read by a computer, or modified by a computer, or both.

This latter distinction will, for the most part, restrict an object to be something internal to a computer. However, to the extent that material objects are hard-wired to a computer, they fall under this same definition. For example, the internal mechanisms of a laser printer that are directly controlled by a processor inside the printer are computer objects in the sense of this definition. In contrast, material objects might be observable by a computer, for example via a digital camera, without their states being directly read by the execution of computer instructions, and so would not qualify as computer objects in this sense.

This generic definition of “object” is meant to be a building block. (Remember, a good definition is a building block.) Let us see how this definition is used in the definitions of two more specialized kinds of objects that make the composition of complex objects possible.

Composing Objects

We have two kinds of computer objects: hardware objects and software objects.

- hardware object: a computer object which is part of the physical composition of a computer

- software object: an object composed of hardware objects and/or other software objects by exclusively authorizing only certain routines to access the component objects

If all we had to work with were hardware objects, we could only write assembly-language programs at a very low level of abstraction. We need a way to compose hardware objects into more complex objects, so that we can have mechanisms that are more complex than computer hardware. The definition of “software object” is crafted to serve this purpose.

We’ll defer looking at what it means to exclusively authorize only certain routines, and focus first on how software objects are composed.

Software Object Composition

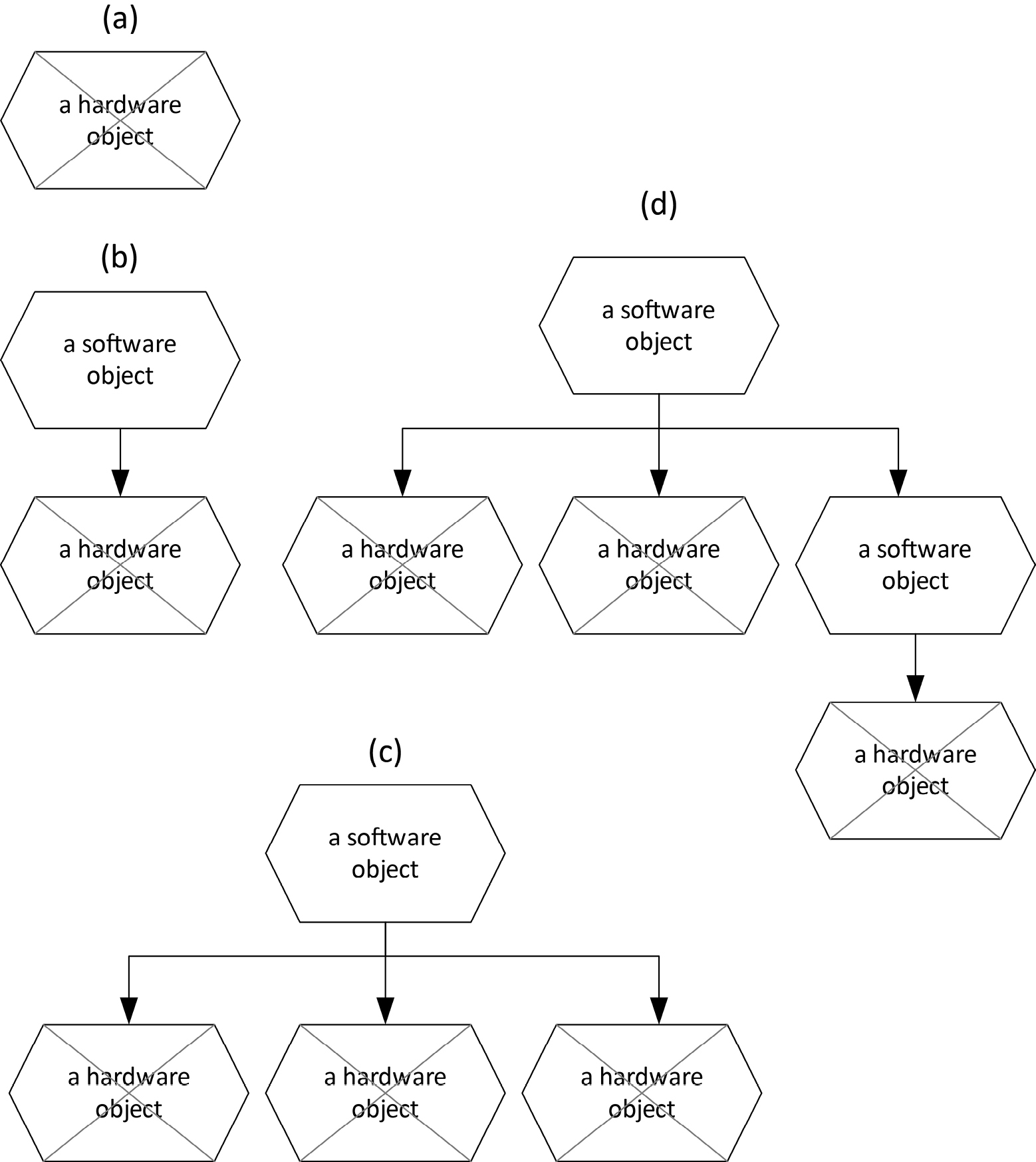

If we drew a graph of the composition of any software object, it would form a strict tree, where

- all of the leaves of the graph would be hardware objects; and

- no software object would be composed of itself, either directly or indirectly through other software objects.

Figure 10-7 shows some example graphs of possible software object compositions using COMN. Each hexagon is an object. A hexagon with an X through it is a simple hardware object; that is, a hardware object that is not divided into component parts. Recall from chapter 2 that all material objects, except for the fundamental particles, are composed of other objects. However, when we are illustrating the component parts of computer objects in COMN, we are not concerned with the physical composition of R-S flip-flops. Rather, we are concerned with whether or not the computer is able to address any smaller part of a hardware object. For example, an 8-bit byte in memory, even though it clearly consists of eight R-S flip-flops, would be considered a simple hardware object if the computer can’t address its individual bits separately.

Figure 10-7. Example Graphs of Software Object Compositions

A hexagon with no X through it is a software object. Software objects always have components, which are either hardware objects or other software objects. An arrow with a solid arrowhead from one object to another indicates composition by aggregation; that is, the referencing object has the referenced (pointed-to) object as a component.

For the programmers among you, here is an extremely precise description of the composition of a software object. The underlying hardware objects—the R-S flip-flops—are aggregated on a silicon chip. They retain their identity, but there’s no breaking them apart. In object-oriented programming languages, a software object is (directly or eventually) formed from a group of adjacent hardware objects in memory. The adjacent objects are juxtaposed to each other. Memory allocation manages a single software object as if it were an aggregation of the juxtaposed hardware objects. Therefore, we consider that software object composition is by aggregation.

We are concerned here with software objects that are composed by aggregation. If one of the components of a software object references another object by address (pointer), that could be composition by assembly, or it could be merely reference.

The graphs in this figure show the following:

- a hardware object

- a software object composed of a single hardware object, where access to the hardware object is restricted to only certain routines

- a software object composed of three hardware objects, where access to those hardware objects is restricted

- a software object composed of two hardware objects and one other software object, which in turn is composed of a hardware object

Thankfully, the composition of software objects from hardware objects is, in most cases, taken care of for us by compilers and database management systems. We are usually focused on composing software objects from other software objects. But it’s really important to understand that at the bottom of every software object are hardware objects—material things having meaningless physical states to which we assign meaning. It is also critical to the completeness goal of COMN that it be able to illustrate this ultimate outcome of any software or data development effort, even if it is just to enable a modeling tool to generate the low-level picture. If we can rely on the fact that a valid COMN design, no matter how high level, can concretely map to a COMN illustration of how that design can be realized in computer hardware and memory, then we know that COMN is both complete and precise.

Authorizing Certain Routines

The second part of the definition of a software object says that access is restricted to a software object’s components “by exclusively authorizing only certain routines to access the component objects”.

How does this exclusive authorization work? The widespread practice in so-called object-oriented software development is that an object-oriented programming language (e.g., Java, C++, or C#) is used to express both the composition of software objects and the routines that may access the component objects. In this context, it is the software written by a programmer that authorizes only certain routines to operate on certain objects, and it is a compiler for the programming language used that enforces this exclusive access. If a programmer writes code that references a software object’s components, and that code is part of a routine not authorized by the program to access those components, the compiler will not allow that code to be translated into computer instructions.

An object-oriented programming language has a construct called a class, which is a specification having two parts:

- some number of components which are objects of other classes, giving the structure of objects of the class

- some number of routines exclusively authorized to access those components, called the methods of the class, collectively establishing the behavior of objects of the class

A class can describe the composition of any software object of any degree of complexity.

This object-oriented programming-language idea of “class” is in line with the definition introduced in chapter 4:

class : a description of the structural and/or behavioral characteristics of potential and/or actual objects

We say that a class encapsulates the components of a software object by exclusively authorizing only the class’s methods to access the components. Encapsulation contributes significantly to the reliability of software systems, by making it easier to confirm that a software object’s states will be manipulated only in legitimate ways. Only the object’s class’s methods need to be validated in order to ensure that the object will “behave” correctly. Objects become the building blocks of larger systems, and those larger systems are more reliable when they are built from objects whose correct operation has been verified.

It is interesting to observe that a software object shares some characteristics with hardware objects.

- A hardware object has a fixed built-in set of mechanisms, accessible by computer instructions, for accessing and/or changing its state. Similarly, a software object has a fixed set of routines for accessing and/or changing its state.

- A hardware object may be composed of other hardware objects not directly accessible by computer instructions. Similarly, a software object may be composed of other (hardware or software) objects not directly accessible by its routines, if those objects are encapsulated within higher-level software objects that are part of the software object.

Summary

Computer objects are entirely physical. Hardware objects have physical states that, for the most part, have no meaning. We refer to the states of these hardware objects using numbers, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that the states represent numbers. They may; they may not.

Software objects can be constructed from hardware objects and other software objects in a tree-like fashion, but—at least as far as we know at this point—the composite states of software objects have no more intrinsic meaning than the states of the hardware objects of which they are composed.

Objects as seen in this light may have states that are useful even though they have no meaning. Think of the flashlight whose “on” state is useful for seeing in the dark, but which has no meaning. When one assigns meaning to an object’s state for some signaling purpose, the state itself still does not express the meaning. A British soldier could stare all night at the two lanterns in the Old North Church tower and never discover the meaning assigned to them. In general, the meanings of an object’s states must be supplied from some source outside the object itself. In the next chapter we’ll see how meaning is supplied.

In addition to the states of objects having no intrinsic meaning, so far the concepts of “value” and “data” are also not associated with objects. This will be shocking to many in the industry. This is a major departure from established thought and terminology. This will be justified in the next chapter.

|

Key Points

|

Chapter Glossary

computer object : a stateful material object whose state can be read and/or modified by the execution of computer instructions

hardware object : a computer object which is part of the physical composition of a computer

software object : an object composed of hardware objects and/or other software objects by exclusively authorizing only certain routines to access the component objects

method : a routine authorized to operate on the components of software objects of the class of which it is a part

encapsulate : to authorize only a certain set of routines (called methods of the class) to operate on the components of objects of a class

state : the physical condition of an object

stateful : having more than one state

stateless : having only one state

value : a concept that is fully specified by a symbol for the concept; also, a symbol for such a concept