|

|

In this chapter we’re going to learn how COMN models express relationships, how data plays roles, and how expressing these relationships as predicates makes the connection from data to semantics. We’re going to start with a design that’s not entirely clear, and then straighten it out based on what we’ve learned about subtypes and predicates.

Arrivals and Departures

Suppose you were in an airport and glanced up to see a display screen with the following information on it:

|

Flight Number |

City |

Time |

|

351 |

Charlotte |

11:05 AM |

|

295 |

Chicago |

11:00 AM |

|

445 |

Gary |

9:17 AM |

|

1023 |

Topeka |

10:47 AM |

Aha, you say, a flight schedule! There’s just one very important piece of information missing: are these departures or arrivals? You typically have to search for a title over the display screen for that information. This shows that two or more sets of data can have the same structure even though they are meant for substitution into different predicates (that is, the logical predicates of chapter 14). Even though the structure of departure and arrival data is the same, there is a great difference in meaning between the proposition that flight 351 is departing for Charlotte at 11:05 AM and the proposition that flight 351 is arriving from Charlotte at 11:05 AM. If you’re a passenger, confusing those two meanings can result in a missed flight, and if you’re an air traffic controller, confusing those two meanings can result in pandemonium!

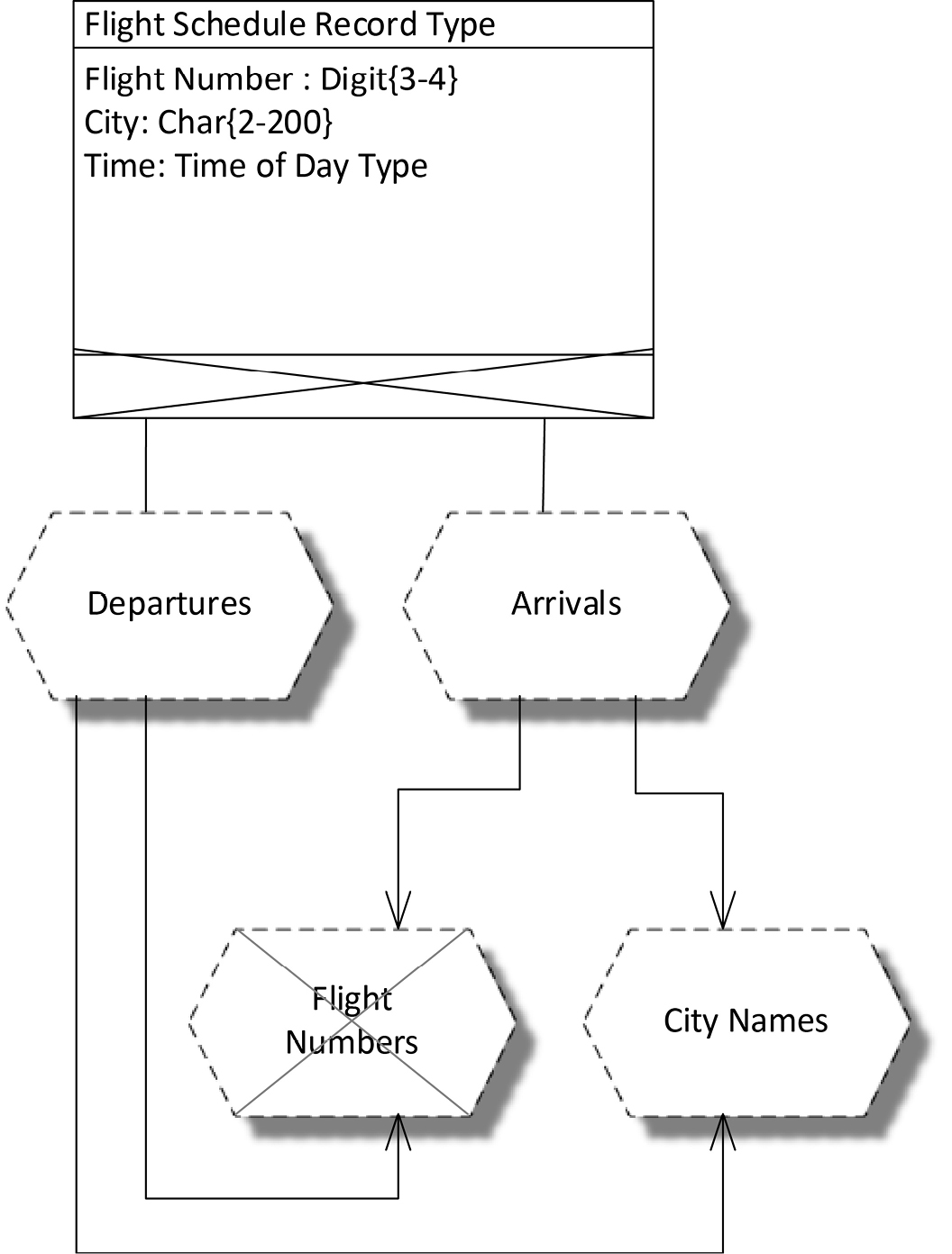

Figure 15-1 shows the common Flight Schedule Record Type as the type of both the Departures and Arrivals record collections.

Figure 15-1. Departures and Arrivals

Since we know that not every 3- or 4-digit number is an actual flight number, nor that every string of up to 200 characters is an actual city name, we want to keep collections of the legitimate values. Before a record of data is stored in the Departures or Arrivals collection, we can check these collections to ensure that the flight number and city name are known. The Flight Number and City Name collections are shown at the bottom of Figure 15-1. Flight Numbers are just integers, and integers are simple types; hence the crossed lines through the hexagon. City Names are character strings, which are arrays of characters and therefore composite types, and so there are no crossed lines. (A single character is a simple type.)

The Departures and Arrivals collections reference the Flight Numbers and City Names collections, as shown by the relationship lines with open arrowheads indicating the direction of reference. This kind of relationship expresses reference without any kind of composition.

Logically—ignoring implementation details—the references to Flight Numbers are made by the Flight Number components of Departures and Arrivals, and the references to City Names are made by the City components of Departures and Arrivals. In a SQL database, the Flight Number and City components are called foreign keys. A foreign key is a component that can only take on values that are found as key values in the referenced table. In this way, a flight schedule’s flight number is restricted to be only known flight numbers and not just any 3- or 4-digit number, and a flight schedule’s city name is restricted to be only known city names and not just any string of characters. No relationship is shown to a table of times. We’d rather not keep a table of all 1440 minutes in a day! Instead, we depend on the Time of Day Type to enforce that the time reference hours and minutes in a day in a customary format.

By this point in the book your COMN antennae may have gone up when you read the words “restricted”, and you might suspect that there are subtypes somewhere here—and in fact there are. Let’s examine the Flight Number component. Its format is defined to be a 3- or 4-digit number. But only some 3- or 4-digit numbers are listed in the Flight Numbers collection, and only those are legitimate flight numbers. Thus, we have two sets:

- the set of all 3- and 4-digit numbers

- the subset of 3- and 4-digit numbers found in the Flight Numbers table.

The foreign key constraint that restricts a Flight Schedule’s Flight Number component is in fact a type, because it designates a set, that set being the flight numbers listed in the Flight Number table.

This shows that it is always true that a foreign key constraint is a subtype. The supertype is the underlying type of the key. The subtype designates the set of key values actually in the referenced table.

This is a really radical observation, because up until now we have always said that the lines in a data model represent relationships, and now we’re learning that some of the lines in fact represent types! To be specific, a reference to a collection without aggregation or assembly, shown in COMN with an open arrowhead, amounts to the definition of a subtype, if the collection has a key.

Many document DBMSs, and other NoSQL DBMSs, don’t have the concept of a foreign key, and will allow flight number and city name fields to accept any digit strings or character strings. But the fact that these DBMSs don’t enforce the type constraints doesn’t mean that the types don’t logically exist. For your NoSQL database design, you should still document that these types exist at the logical level. When you move to physical database design, and have no way to represent or enforce these logical types physically, it will be important to document that these fields are wide open, and the database is dependent on the application code to store only data that is of the correct logical type.

Labeling Relationship Lines

It is customary in E-R notations and in the UML to label a relationship line with any or all of the following:

- the name of the relationship type (for example, employment)

- verb phrases for reading the relationship in one or both directions (for example, employs / is employed by)

- the role played by the data at each end of the relationship (for example, employer, employee)

These labels are given in fact-based models by labeling the role boxes that are connected by lines to so-called object types (which we would simply call types in COMN).

These labels correspond directly to the predicates that give the data meaning, so they’re pretty important. The roles are the predicate variables, and either one of the verb phrases or the name of the relationship type can be used as the name of the predicate.

Looking at Table 15-1, we can deduce the predicates implicit in the data, as follows:

Flight #Flight Number departs to city City.

Flight #Flight Number departs at time Time.

or

Flight #Flight Number arrives from city City.

Flight #Flight Number arrives at time Time.

These predicates have been broken down into simple predicates (no AND conjunction) so that each one expresses a binary relationship—just two variables. I’ve done that so we could put these predicates on relationship lines, which connect just two entities. We haven’t yet covered how to show relationships between three or more entities.

We would like to label the relationship lines in our Departures and Arrivals model—specifically, the reference relationships with open arrowheads—but we have several problems. We can easily label the line from Departures to City Names with “departs to city”, and the line from Arrivals to City Names with “arrives at city”. But where do we put the labels “departs at time” and “arrives at time”? And is there any meaningful way to label the lines from Departures and Arrivals to Flight Numbers?

We have a model, then, that can’t support the annotation of all of the meaning that it expresses.

We’re going to address this situation by doing two things:

- We are going to clean up the model of Figure 15-1, so that it contains more type information and less redundancy.

- We are going to borrow the role box notation of fact-based modeling to enable us to document relationships even when we don’t have relationship lines to label.

Cleaning Up the Model

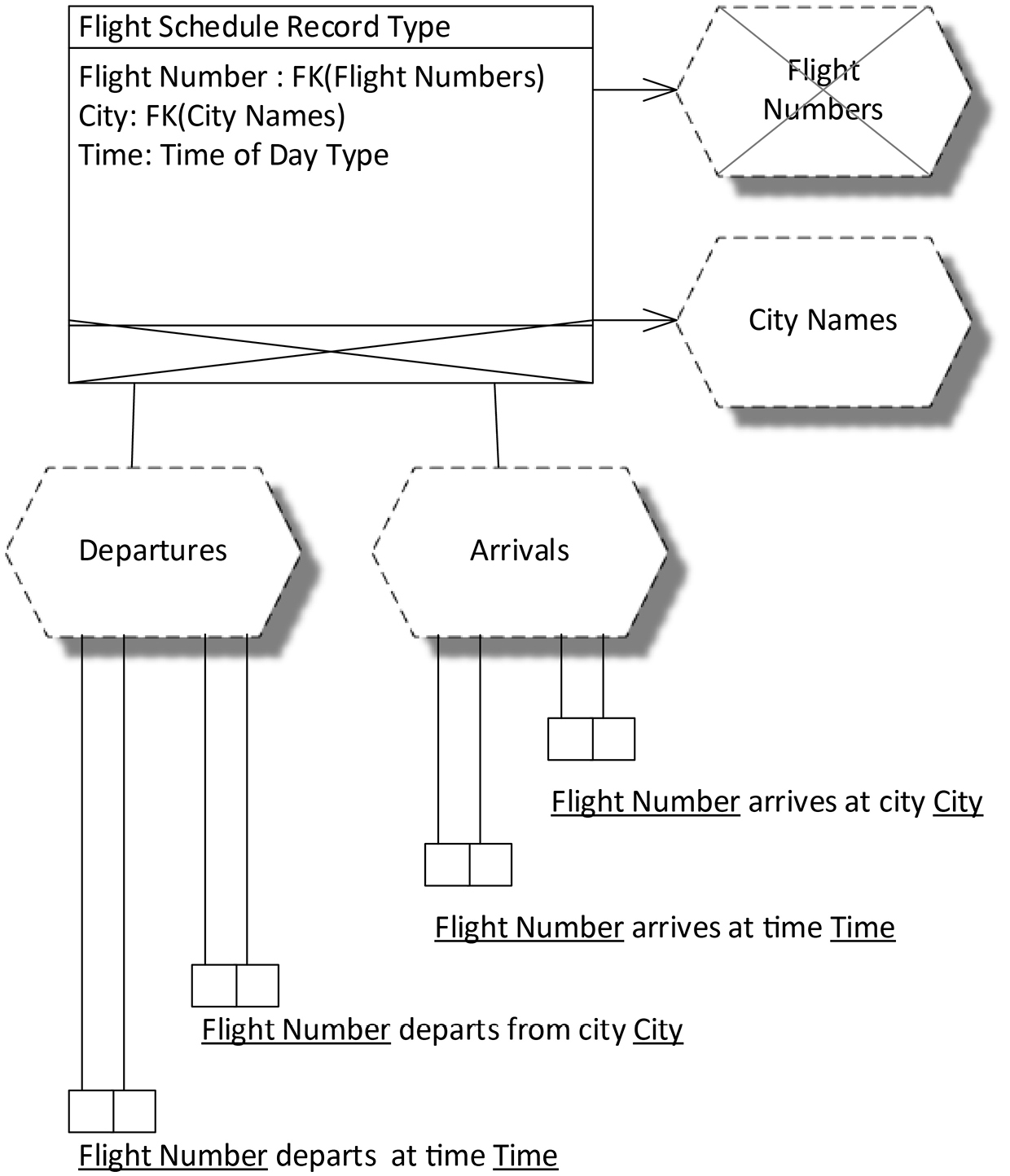

We learned in the previous section that foreign-key reference relationships actually represent subtypes. Our Flight Schedule Record Type does not benefit from this reality, because its types for Flight Number and City are very weak: those components will accept any 3-4 digit numbers and any 2-200 character strings, respectively, whether or not they are known flight numbers and known city names. To fix this, we should have the Flight Schedule Record Type reference the Flight Numbers and City Names collections. This will also remove the parallel references to those collections from the Departures and Arrivals collections, making the model less cluttered. Of course, this removes some of the relationship lines we’d like to label, but we’ll address that problem with role boxes.

We’ll use role boxes to give us places to record the predicates relevant to this model.

The result is shown in Figure 15-2.

Figure 15-2. Flight Schedules with Role Boxes

Within the Flight Schedule Record Type rectangle, we’ve changed the types of the components Flight Number and City. The type of Flight Number is now given as FK(Flight Numbers), meaning that a Flight Number’s type is the set of all key values found in the Flight Numbers collection. “FK” stands for foreign key. Likewise, the type of City has been changed to FK(City Names). If we wanted to know the underlying types of Flight Numbers and City Names—that is, the types of the keys, which are the supertypes involved here—we’d have to look at the logical record types for Flight Numbers and City Names. They aren’t shown in this model just to keep the clutter down. This change further reduces redundancy in the model, because now those underlying types are defined only once, rather than both at their origin and at their point of reference.

At the bottom of Figure 15-2 you’ll see the role boxes used in fact-based modeling. Each group of small role box rectangles represents a predicate, and the number of boxes in the group gives the number of variables in the predicate. The phrase near a group spells out the predicate, and uses logical record type component names (underlined) as variable names.

The role boxes illustrate that, in a record-oriented design, relationships exist between components of a single logical record. Foreign-key relationships are really subtype specifications.

If you’re lucky enough to have a design where all the important relationships correspond to the subtype/foreign key relationships, you can skip the role boxes and label those relationship lines. But you can see from this example that you might not always be so lucky.

Which notation should one use? That is almost entirely an issue of preference. There is a large community of data modelers and business people who are comfortable with E-R notations, and the very similar UML notation. The community of data modelers and business people familiar with fact-based modeling is much smaller. This would tilt the preference for notation in favor of foreign-key/subtype relationship lines over small-box relationship notation. However, if one wished to show the relationships that exist between components of a single logical record type when no foreign key is involved, or when the diagram doesn’t show the referenced logical record type as a rectangle, role-box notation can be used.

Furthermore, role-box notation can show relationships involving three or more data items—predicates with three or more variables—without forcing the inclusion of a so-called “associative entity” in the diagram.

Roles, Predicates, and Relationships

Recall our discussion in chapter 13 about how a person related to a coffee shop can play either the role of a customer or the role of an employee, or both. This shows that a person can play multiple roles in life. (Certainly, actors play multiple roles!) We saw in chapter 13 how to illustrate data about these multiple roles in COMN.

Now we see that even data plays roles. In fact, as we saw in the previous chapter, a value isn’t even data unless it plays a role as a value for a variable in a predicate.

We’ve also seen that relationships exist between the components of a single logical record type, and that predicates express those relationships.

It turns out that the great struggle to find good names for logical record type components (data attributes) is a struggle to name the variables of logical predicates. This struggle is not made any easier by the fact that we rarely write down the predicates. Understanding that data attributes play roles should focus us on naming logical record type components based on the roles played by them in relationships.

We have used the term “relationship” heavily throughout this book. It is time to give it a robust definition. A relationship is a proposition concerning two or more entities. Thus, the statement that “Flight #351 is departing for the city of Charlotte” is a relationship. So is the statement that “Flight #351 departs at 11:05 AM.”

A collection of logical records expresses a set of relationships, which are propositions that we would intuitively recognize are all of the same type. Using our COMN terminology, we would search for something that designates that set of relationships, and whatever designates that set is the type.

It turns out that, just as we have two types involved in every foreign key relationship—the type of the key, which is the supertype, and the collection of key values, which are the set designated by the foreign key—we have two types involved in every table of records.

The logical record type, apart from any particular collection of values, creates the potential to have a set of values which contains every possible combination of flight number, city name, and time. (It’s highly unlikely that we’d ever create a table with all those values.) So the logical record type is a type because it designates that set.

The Departures and Arrivals collections both draw from that same supertype. Their particular values are those values for which their related predicates are true. Thus, the predicates in effect designate sets of values, and that means—you guessed it!—a predicate is a type. We can say specifically that a logical predicate is a relationship type, because it designates a potential set of relationship propositions.

|

Key Points

|

Chapter Glossary

relationship : a proposition concerning two or more entities

relationship type : a logical predicate