Chapter 15. Java 9 and the Future

While this book was being written, Java 9 was in active development. The new release contains a number of performance-related features and enhancements that are relevant to the Java/JVM application engineer.

In the first part of this chapter, we survey the new and modified aspects of the platform that a performance engineer should know about in Java 9.

The truth is, for most developers, Java 9 really does consist of “modules and then everything else.” Just as Java 8 was all about lambdas and their consequences (streams, default methods, and small aspects of functional programming), so Java 9 is mostly about modules.

Modules are a new way of building and deploying software and are not easy to adopt piecemeal. They represent a very modern way to build well-architected apps. However, it may take teams and projects a while to see the long-term benefits of adopting modules. For our purposes modules are not of any real performance significance, and so we make no attempt to discuss them in any detail and instead focus on the smaller but performance-relevant changes.

Note

Readers interested in Java 9 modules should consult an appropriate reference, such as Java 9 Modularity by Sander Mak and Paul Bakker (O’Reilly).

The majority of this chapter is taken up with a discussion of the future, as it exists at the time of writing. The Java platform ecosystem has a number of initiatives under way that have the potential to radically reshape the performance landscape for JVM applications. To conclude the book, we will take a look at these projects and their relevance to Java performance professionals.

Small Performance Enhancements in Java 9

This section discusses the enhancements made in Java 9 that are relevant to performance. Some of them are quite small, but could be significant for some applications. In particular, we will discuss changes such as:

-

The segmented code cache

-

Compact strings

-

New string concatenation

-

C2 compiler improvements

-

G1 changes

Segmented Code Cache

One improvement delivered in Java 9 is to split the code cache into separate regions for:

-

Nonmethod code such as the interpreter

-

Profiled code (Level 2 and Level 3 from the client compiler)

-

Nonprofiled code (Level 1 and Level 4)

This should result in shorter sweeper times (the nonmethod region will not require sweeping) and better code locality for fully optimized code. The downside of a segmented code cache is the possibility of one region filling up while there is space available in other regions.

Compact Strings

In Java, the contents of a string have always been stored as a char[].

As char is a 16-bit type, this means that roughly twice as much space is used to store ASCII strings than is actually required.

The platform has always treated this overhead as a price worth paying to simplify Unicode handling.

With Java 9 comes the possibility of compact strings.

This is a per-string opportunity to optimize.

If the string can be represented in Latin-1, then it is represented as a byte array (with the bytes understood to correspond to Latin-1 characters), and the empty zero bytes of the char representation are saved.

In the source code of the Java 9 String class, this change looks like this:

privatefinalbyte[]value;/*** The identifier of the encoding used to encode the bytes in* {@code value}. The supported values in this implementation are** LATIN1* UTF16** @implNote This field is trusted by the VM, and is a subject to* constant folding if String instance is constant. Overwriting this* field after construction will cause problems.*/privatefinalbytecoder;staticfinalbyteLATIN1=0;staticfinalbyteUTF16=1;

In Java 9, the value field is now byte[] rather than char[] as in earlier versions.

Note

You can disable or enable this feature by passing -XX:-CompactStrings or -XX:+CompactStrings (which is the default).

This change will have the most pronounced effect on applications that have a large heap containing a lot of string data that is Latin-1 (or ASCII) only—for example, ElasticSearch, caches, and other related components. For these applications, it may be worth moving to a Java 9 runtime for this improvement alone.

New String Concatenation

Consider this simple bit of Java:

publicclassConcat{publicstaticvoidmain(String[]args){Strings="("+args[0]+" : "+args[1]+")";System.out.println(s);}}

Since Java 5, this language feature has been desugared into a series of method calls involving the StringBuilder type.

This produces a fairly large amount of bytecode:

publicstaticvoidmain(java.lang.String[]);Code:0:new#2// class java/lang/StringBuilder3:dup4:invokespecial#3// Method java/lang/StringBuilder."<init>":()V7:ldc#4// String (9:invokevirtual#5// Method java/lang/StringBuilder.append:// (Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;12:aload_013:iconst_014:aaload15:invokevirtual#5// Method java/lang/StringBuilder.append:// (Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;18:ldc#6// String :20:invokevirtual#5// Method java/lang/StringBuilder.append:// (Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;23:aload_024:iconst_125:aaload26:invokevirtual#5// Method java/lang/StringBuilder.append:// (Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;29:ldc#7// String )31:invokevirtual#5// Method java/lang/StringBuilder.append:// (Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;34:invokevirtual#8// Method java/lang/StringBuilder.toString:// ()Ljava/lang/String;37:astore_138:getstatic#9// Field java/lang/System.out:// Ljava/io/PrintStream;41:aload_142:invokevirtual#10// Method java/io/PrintStream.println:// (Ljava/lang/String;)V45:return

However, under Java 9, the compiler produces radically different bytecode:

publicstaticvoidmain(java.lang.String[]);Code:0:aload_01:iconst_02:aaload3:aload_04:iconst_15:aaload6:invokedynamic#2,0// InvokeDynamic #0:makeConcatWithConstants:// (Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;)// Ljava/lang/String;11:astore_112:getstatic#3// Field java/lang/System.out:// Ljava/io/PrintStream;15:aload_116:invokevirtual#4// Method java/io/PrintStream.println:// (Ljava/lang/String;)V19:return

This relies on invokedynamic, which was introduced in “Introduction to JVM Bytecode”.

By looking at the verbose output from javap we can see the bootstrap method in the constant pool:

0:#17REF_invokeStaticjava/lang/invoke/StringConcatFactory.makeConcatWithConstants:(Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodHandles$Lookup;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodType;Ljava/lang/String;[Ljava/lang/Object;)Ljava/lang/invoke/CallSite;

This uses a factory method called makeConcatWithConstants() from the StringConcatFactory to produce a recipe for concatenation.

This technique can use a number of different strategies, including writing bytecode for a new custom method.

It is similar in some ways to using a prepared statement for SQL execution rather than naive string assembly.

The overall performance impact of this small change is not expected to be very significant for many applications.

However, the change does indicate the broader use of invokedynamic and illustrate the general direction of the evolution of the platform.

C2 Compiler Improvements

The C2 compiler is now quite mature, and it is widely believed (by companies such as Twitter, and even by experts such as Cliff Click) that no more major enhancements are possible within the current design. This means that any improvements are, of necessity, somewhat marginal. However, one area that would potentially allow better performance is the use of Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) extensions present on modern CPUs.

When compared to other programming environments, Java and the JVM are in a good position to exploit these due to the following platform features:

-

Bytecode is platform-agnostic.

-

The JVM performs CPU probing at startup, so it knows the capabilities of the hardware it executes on at runtime.

-

JIT compilation is dynamic code generation, so can use all instructions available on the host.

As discussed in “Intrinsics”, the route to implement these improvements is the area of VM intrinsics.

A method is intrinsified if the HotSpot VM replaces the annotated method with hand-written assembly and/or handwritten compiler IR—a compiler intrinsic to improve performance.

@HotSpotIntrinsicCandidate JavaDoc

HotSpot already supports some of x86 SIMD instructions, including:

-

Automatic vectorization of Java code

-

Superword optimizations in C2 to derive SIMD code from sequential code

-

JVM SIMD intrinsics, including array copying, filling, and comparison

The Java 9 release contains a number of fixed issues that implement improved or new intrinsics to take even better advantage of SIMD and related processor features. From the release notes, the following issues are closed as fixed, due to the addition of enhanced intrinsics:

-

Masked vector post loops

-

SuperWord loop unrolling analysis

-

Multiversioning for range check elimination

-

Support for vectorizing double-precision

sqrt -

Improved vectorization of parallel streams

-

SuperWord enhancement to support vector conditional move (CMovVD) on Intel AVX CPUs

In general, intrinsics should be recognized as point fixes and not general techniques. They have the advantage that they are powerful, lightweight, and flexible, but have potentially high development and maintenance costs as they must be supported across multiple architectures. The SIMD techniques are useful and welcome, but are clearly an approach offering only diminishing returns to performance engineers.

New Version of G1

As discussed in “G1”, G1 is designed to solve several problems at once, offering features such as easier tuning and better control of pause times. In Java 9, it became the default garbage collector. This means that applications moving from Java 8 to 9 that do not explicitly set their choice of collector will experience a change of collection algorithm. Not only that, but the version of G1 that ships in Java 9 is different from the version in Java 8.

Oracle has claimed that in its benchmarks, the new version performs substantially better than the version present in Java 8. This has not been supported by the public publication of any results or studies, however, and for now we have only anecdotal community evidence at best.

Hopefully most applications will not be negatively impacted by this change of algorithm. However, all applications moving to Java 9 should do a full performance test if they are impacted by the switch (i.e., if they use Java 8 with default collection or G1).

Java 10 and Future Versions

Java 9 has just been released at the time of writing. As a result, development effort on the platform has now fully switched to the next version, Java 10. In this section, we’ll discuss the new release model that will be in effect as of the next version before looking at what is known about Java 10 at this point.

New Release Process

Mere days before the release of Java 9, Oracle announced a brand new release model for Java, starting with Java 10. Releases had historically been feature-driven; major changes were targeted for a specific release, and if necessary the release was delayed until the feature was ready. This approach caused significant delays to the release of Java 9, and also impacted Java 8.

The feature-driven release cycle also had far deeper implications for the overall speed of development of the Java platform. Keystone features actually acted as a blocker on other smaller features, due to the long cycles needed to produce and fully test a release. Delaying a release close to the end of the development cycle means that the source repos are in a locked-down or semi-locked-down form for a much higher percentage of the available development cycle.

From Java 10 onward, the project has moved to a strict time-based model. A new version of Java, containing new features, will ship every six months. These releases are to be known as feature releases, and are the equivalent of major releases in the old model.

Note

Feature releases will not typically contain as many new features or as much change as a major Java release did in the old model. However, major features will still sometimes arrive in a feature release.

Oracle will also offer Long-Term Support (LTS) releases for some of the feature releases. These will be the only releases that Oracle will make as a proprietary JDK. All other releases will be OpenJDK binaries, under the GNU Public License (GPL) with the Classpath exemption—the same license that has always been used for open source Java builds. Other vendors may also offer support for their binaries, and may decide to support releases other than LTS versions.

Java 10

At the time of writing, the scope for Java 10 is still being confirmed and locked down. As a result, there is still the possibility of significant changes to its scope and content between now and the release. For example, in the few weeks immediately after the release of Java 9, there was a public debate about the version numbering scheme that would be used going forward.

New JVM features or enhancements are tracked through the Java Enhancement Process. Each JDK Enhancement Proposal (JEP) has a number that it can be tracked under. These are the major features that shipped as part of Java 10, not all of which are performance-related or even directly developer-facing:

-

286: Local-Variable Type Inference

-

296: Consolidate the JDK Forest into a Single Repository

-

304: Garbage-Collector Interface

-

307: Parallel Full GC for G1

-

310: Application Class-Data Sharing

-

312: Thread-Local Handshakes

JEP 286 allows the developer to reduce boilerplate in local variable declarations, so that the following becomes legal Java:

varlist=newArrayList<String>();// infers ArrayList<String>varstream=list.stream();// infers Stream<String>

This syntax will be restricted to local variables with initializers and local variables in for loops.

It is, of course, implemented purely in the source code compiler and has no real effect on bytecode or performance.

Nevertheless, the discussion of and reaction to this change illustrates one important aspect of language design, known as Wadler’s Law after the functional programmer and computer scientist Philip Wadler:

The emotional intensity of debate on a language feature increases as one moves down the following scale: Semantics, Syntax, Lexical Syntax, Comments.

Of the other changes, JEP 296 is purely housekeeping and JEP 304 increases code isolation of different garbage collectors and introduces a clean interface for garbage collectors within a JDK build. Neither of these has any impact on performance either.

The remaining three changes all have some impact, albeit potentially small, on performance. JEP 307 solves a problem with the G1 garbage collector that we have not previously addressed; if it ever has to fall back to a full GC, then a nasty performance shock awaits. As of Java 9, the current implementation of the full GC for G1 uses a single-threaded (i.e., serial) mark-sweep-compact algorithm. The aim of JEP 307 is to parallelize this algorithm so that in the unlikely event of a G1 full GC the same number of threads can be used as in the concurrent collections.

JEP 310 extends a feature called Class-Data Sharing (CDS), which was introduced in Java 5. The idea is that the JVM records a set of classes and processes them into a shared archive file. This file can then be memory-mapped on the next run to reduce startup time. It can also be shared across JVMs and thus reduce the overall memory footprint when multiple JVMs are running on the same host.

As of Java 9, CDS only allows the Bootstrap classloader to load archived classes. The aim of this JEP is to extend this behavior to allow the application and custom classloaders to make use of archive files. This feature exists, but is currently available only in Oracle JDK, not OpenJDK. This JEP therefore essentially moves the feature into the open repo from the private Oracle sources.

Finally, JEP 312 lays the groundwork for improved VM performance, by making it possible to execute a callback on application threads without performing a global VM safepoint. This would mean that the JVM could stop individual threads and not just all of them. Some of the improvements that this change will enable include:

-

Reducing the impact of acquiring a stack trace sample

-

Enabling better stack trace sampling by reducing reliance on signals

-

Improving biased locking by only stopping individual threads for revoking biases

-

Removing some memory barriers from the JVM

Overall, Java 10 is unlikely to contain any major performance improvements, but instead represents the first release in the new, more frequent and gradual release cycle.

Unsafe in Java 9 and Beyond

No discussion of the future of Java would be complete without mention of the controversy surrounding the class sun.misc.Unsafe and the associated fallout.

As we saw in “Building Concurrency Libraries”, Unsafe is an internal class that is not a part of the standard API, but as of Java 8 has become a de facto standard.

From the point of view of the library developer, Unsafe contains a mixture of features of varying safety.

Methods such as those used to access CAS hardware are basically entirely safe, but nonstandard.

Other methods are not remotely safe, and include such things as the equivalent of pointer arithmetic.

However, some of the “not remotely safe” functionality cannot be obtained in any other way.

Oracle refers to these capabilities as critical internal APIs, as discussed in the relevant JEP.

The main concern is that without a replacement for some of the features in sun.misc.Unsafe and friends, major frameworks and libraries will not continue to function correctly.

This in turn indirectly impacts every application using a wide range of frameworks, and in the modern environment, this is basically every application in the ecosystem.

In Java 9, the --illegal-access runtime switch has been added to control runtime accessibility to these APIs.

The critical internal APIs are intended to be replaced by supported alternatives in a future release, but it was not possible to complete this before Java 9 shipped.

As a result, access to the following classes has had to be maintained:

-

sun.misc.{Signal,SignalHandler} -

sun.misc.Unsafe -

sun.reflect.Reflection::getCallerClass(int) -

sun.reflect.ReflectionFactory -

com.sun.nio.file.{ExtendedCopyOption,ExtendedOpenOption, ExtendedWatchEventModifier,SensitivityWatchEventModifier}

In Java 9, these APIs are defined in and exported by the JDK-specific module jdk.unsupported, which has this declaration:

modulejdk.unsupported{exportssun.misc;exportssun.reflect;exportscom.sun.nio.file;openssun.misc;openssun.reflect;}

Despite this temporary (and rather grudging) support from Oracle, many frameworks and libraries are having problems moving to Java 9, and no announcement has been made as to when the temporary support for critical internal APIs will be withdrawn.

Having said that, definite progress has been made in creating alternatives to these APIs.

For example, the getCallerClass() functionality is available in the stack-walking API defined by JEP 259.

There is also one other very important new API that aims to start replacing functionality from Unsafe; we’ll look at that next.

VarHandles in Java 9

We have already met method handles in Chapter 11 and Unsafe in Chapter 12.

Method handles provide a way to manipulate directly executable references to methods, but the original functionality was not 100% complete for fields as only getter and setter access was provided. This is insufficient, as the Java platform provides access modes for data that go beyond those simple use cases.

In Java 9, method handles have been extended to include variable handles, defined in JEP 193. One intent of this proposal was to plug these gaps and, in doing so, provide safe replacements for some of the APIs in Unsafe.

The specific replacements include CAS functionality and access to volatile fields and arrays.

Another goal is to allow low-level access to the memory order modes available in JDK 9 as part of the updates to the JMM.

Let’s look at a quick example that shows how we might approach replacing Unsafe:

publicclassAtomicIntegerWithVarHandlesextendsNumber{privatevolatileintvalue=0;privatestaticfinalVarHandleV;static{try{MethodHandles.Lookupl=MethodHandles.lookup();V=l.findVarHandle(AtomicIntegerWithVarHandles.class,"value",int.class);}catch(ReflectiveOperationExceptione){thrownewError(e);}}publicfinalintgetAndSet(intnewValue){intv;do{v=(int)V.getVolatile(this);}while(!V.compareAndSet(this,v,newValue));returnv;}// ....

This code is essentially equivalent to the example of the atomic integer that we saw in “Building Concurrency Libraries” and demonstrates how a VarHandle can replace the usage of unsafe techniques.

At the time of writing, the actual AtomicInteger class has not been migrated to use the VarHandle mechanism (due to cyclic dependencies) and still relies on Unsafe.

Nevertheless, Oracle strongly advises all libraries and frameworks to move to the new supported mechanisms as soon as possible.

Project Valhalla and Value Types

The mission statement of Project Valhalla is to be “a venue to explore and incubate advanced Java VM and Language feature candidates.” The major goals of the project are explained as:

-

Aligning JVM memory layout behavior with the cost model of modern hardware

-

Extending generics to allow abstraction over all types, including primitives, values, and even

void -

Enabling existing libraries, especially the JDK, to compatibly evolve to fully take advantage of these features

Buried within this description is a mention of one of the most high-profile efforts within the project: exploring the possibility of value types within the JVM.

Recall that, up to and including version 9, Java has had only two types of values: primitive types and object references. To put this another way, the Java environment deliberately does not provide low-level control over memory layout. As a special case, this means that Java has no such thing as structs, and any composite data type can only be accessed by reference.

To understand the consequences of this, let’s look at the memory layout of arrays.

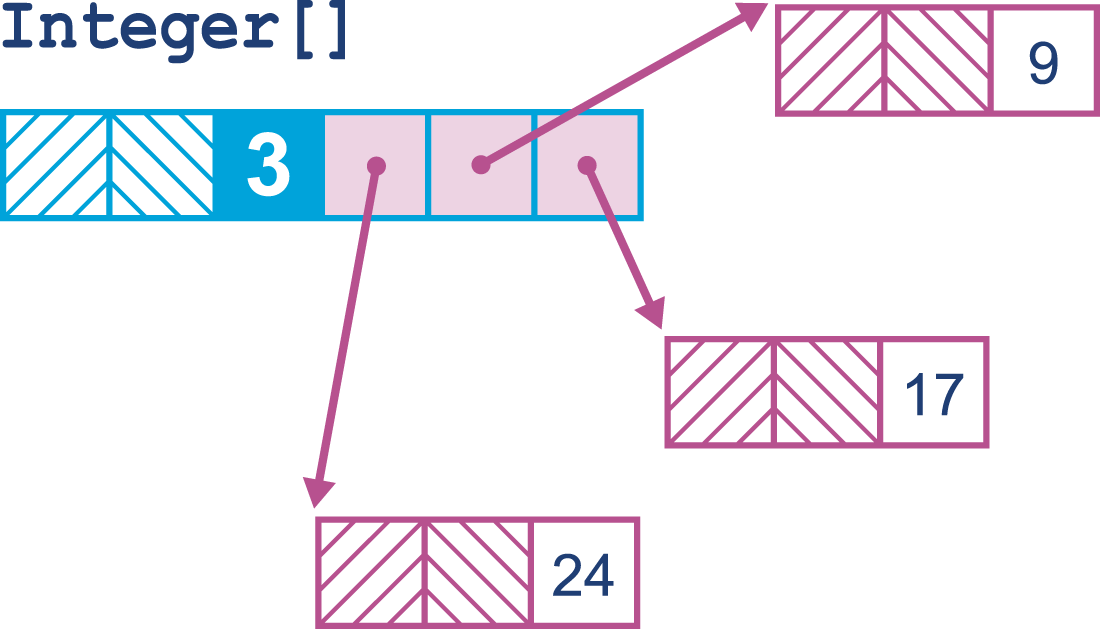

In Figure 15-1 we can see an array of primitive ints.

As these values are not objects, they are laid out at adjacent memory locations.

Figure 15-1. Array of ints

By contrast, the boxed integer is an object and so is referred to by reference.

This means that an array of Integer objects will be an array of references.

This is shown in Figure 15-2.

Figure 15-2. Array of Integers

For over 20 years, this memory layout pattern has been the way that the Java platform has functioned. It has the advantage of simplicity, but has a performance tradeoff—dealing with arrays of objects involves unavoidable indirections and attendant cache misses.

As a result, many performance-oriented programmers would like the ability to define types that can be laid out in memory more effectively. This would also include removing the overhead of needing a full object header for each item of composite data.

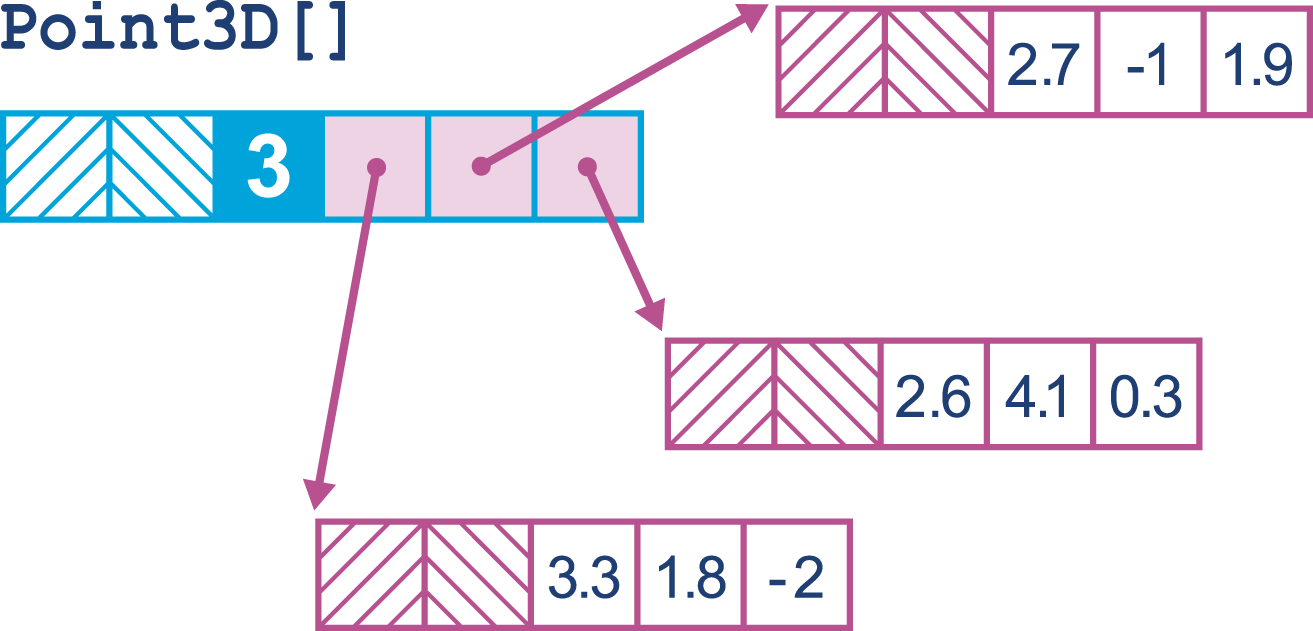

For example, a point in three-dimensional space, a Point3D, really only comprises the three spatial coordinates.

As of Java 9, such a type can only be represented as an object type with three fields:

publicfinalclassPoint3D{privatefinaldoublex;privatefinaldoubley;privatefinaldoublez;publicPoint3D(doublea,doubleb,doublec){x=a;y=b;c=z;}// Getters and other boilerplate elided}

Therefore, an array of points will have the memory layout shown in Figure 15-3.

Figure 15-3. Array of Point3Ds

When this array is being processed, each entry must be accessed via an additional indirection to get the coordinates of each point. This has the potential to cause a cache miss for each point in the array, for no real benefit.

It is also the case that object identity is meaningless for the Point3D types.

That means that they are equal if and only if all their fields are equal.

This is broadly what is meant by a value type in the Java ecosystem.

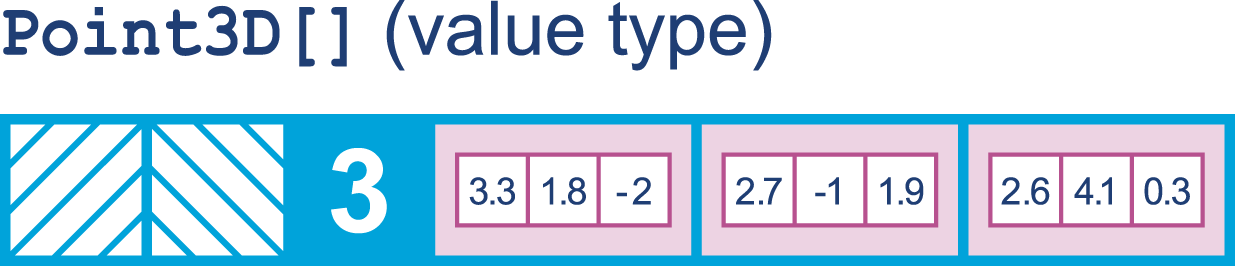

If this concept can be implemented in the JVM, then for simple types such as spatial points, a memory layout such as that shown in Figure 15-4 (effectively an array of structs) would be far more efficient.

Figure 15-4. Array of “struct-like” Point3Ds

Not only this, but then other possibilities (such as user-defined types that behave in a similar way to built-in primitive types) also emerge.

However, there are some key conceptual difficulties in this area.

One important problem is related to the design decisions made as part of the addition of generic types in Java 5. This is the fact that the Java type system lacks a top type, so there is no type that is the supertype of both Object and int.

We can also say that the Java type system is not single-rooted.

As a consequence of this, Java’s generics range only over reference types (subtypes of Object), and there is no obvious way to construct a consistent meaning for, say, List<int>.

Java uses type erasure to implement backward-compatible generic types over reference types, but this much-hated mechanism is not responsible for the lack of a top type and the resulting lack of primitive collections.

If the Java platform is to be extended to include value types, then the question naturally arises as to whether value types can be used as type parameter values. If not, then this would seem to greatly limit their usefulness. Therefore, the design of value types has always included the assumption that they will be valid as values of type parameters in an enhanced form of generics.

At the time of writing, this has led to a design in which there should be three different shapes of JVM class and interface types:

-

Reference types (

R), which represent references to an instance of a class that has an identity or isnull -

Value types (

Q), which are instances of value classes that lack identity

This begs the question, “How should type information in existing class files be understood?”

That is, are the existing L types (that correspond to current types in Java 9 class files) actually R types, or are they really U types, and it’s simply the case that we’ve never seen a Q type before?

For compatibility reasons, and to allow us to extend the definition of generics to include Q types, L types are understood to be U types, rather than R types.

This is quite an early prototype, and there are still plenty of design issues to be worked out—for example, the question of whether value types will require variable-width values at VM level.

In Java 9, at VM level all types have fixed-width values. Primitive types are either 1, 2, 4, or 8 bytes wide and object references are pointers (so they are 1 machine word wide). On modern hardware this means that references are either 32- or 64-bit depending on the hardware architecture of the machine.

Will the addition of value types mean the bytecode will need to accommodate variable-width types? Is there space in the bytecode for the instructions needed for this? Currently, it is believed that only two new opcodes need to be added:

-

vdefault, which produces the defaultQ-typed instance of a value class -

withfield, which produces a new value of the input type and throws an exception on nonvalue ornullinputs

Some bytecodes will also need some retrofitting to handle the new Q types.

Above the VM level, extensive work is also needed to allow the core libraries to evolve in a compatible manner.

Valhalla may be motivated by performance considerations, but a better way to view it is as enhancing abstraction, encapsulation, safety, expressiveness, and maintainability—without giving up performance.

Brian Goetz

Due to the changes to the release schedule, it is unclear which release of Java will eventually introduce value types as a production feature. The authors’ best guess is that they will arrive in one of the 2019 releases, but this is unconfirmed by Oracle.

Graal and Truffle

The C2 compiler present in HotSpot has been enormously successful. However, it has been delivering obvious diminishing returns in recent years, and no major improvements have been implemented in the compiler in the last several years. For all intents and purposes, C2 has reached the end of its lifecycle and must now be replaced.

The current direction of research intended to lead to new shipping products is based around Graal and Truffle. The former is a specialized JIT compiler, and the latter is an interpreter generator for hosting languages on the JVM runtime.

One avenue of potential improvement for the JIT compiler is that the C2 compiler is written in C++, which exposes some potentially serious issues. C++, is, of course, an unsafe language that uses manual memory management, so errors in C2’s code can crash the VM. Not only that, but the code in C2 has been modified and iterated on repeatedly and as a result has become very hard to maintain and extend.

To make progress, Graal is trying a different approach; it is a JIT compiler for the JVM written in Java. The interface that the JVM uses to talk to Graal is called the JVM Compiler Interface (JVMCI) and was added to the platform as JEP 243. This lets you plug in a Java interface as a JIT compiler, in a similar way to how Java agents can be plugged into the JVM.

The view taken by the project is that a JIT compiler really just needs to be able to accept JVM bytecode and produce machine code.

At a low level, the compiler just transforms a byte[] (bytecode) into another byte[] (machine code), so there is no reason why this couldn’t be implemented in Java.

This Java-in-Java approach has a number of benefits, including simplicity, memory safety, and being able to use a standard Java toolchain such as IDEs and debuggers rather than requiring compiler developers to have skills in an esoteric dialect of C++.

These advantages are enabling powerful new optimizations such as partial escape analysis (as mentioned in “Limitations of Escape Analysis”) to be implemented in Graal rather than C2. One additional advantage is that Graal enables teams to modify parts of it for their own applications, such as developing custom intrinsics (e.g., for custom hardware) or optimization passes.

Truffle is a framework for developing interpreters for languages on the JVM. It is designed to work in concert with Graal as a library to automatically generate a high-performance JIT compiler for the input language from just the interpreter, using an academic technique called the Futamuru projection. This is a technique from the area of academic computer science known as partial specialization that has recently become more practical to use in real systems (although some of the ideas have been used in the Python PyPy implementation for several years).

Truffle is an alternative to the approach of generating bytecode at runtime that is used by existing language implementations on the JVM, such as JRuby, Jython, and Nashorn. The performance measurements so far indicate that the combination of Truffle and Graal can potentially deliver much higher performance than previously seen.

The umbrella project for all of this work is the new Project Metropolis. This is an effort to rewrite more of the VM in Java, starting with HotSpot’s JIT compilers and possibly the interpreter.

The Metropolis/Graal technology is present and shipping in Java 9, although it is still very much experimental. The switches to enable a new JIT compiler to be used are:

-XX:+UnlockExperimentalVMOptions -XX:+EnableJVMCI -XX:+UseJVMCICompiler

There is one other way in which Graal can be used in Java 9: the Ahead-of-Time compiler mode.

This compiles Java directly into machine code, in a similar way to C and C++.

Java 9 includes a jatoc command that uses Graal and has the sole goal of speeding up startup time until the normal tiered compilation can take over.

The tool currently supports only the java.base module on a single platform (Linux/ELF), but support is expected to expand over the next few releases of Java.

To create the binaries from Java class files, we use the new jaotc tool as follows:

jaotc --output libHelloWorld.so HelloWorld.class jaotc --output libjava.base.so --module java.base

Finally, SubstrateVM is a research project (also using Graal) to take this functionality further and to compile a whole JVM written in Java along with a Java application to produce a single, statically linked native executable. The aim is that this will produce native binaries that do not need any form of JVM installed and can be as small as a few kilobytes and start in a few milliseconds.

Future Directions in Bytecode

One of the biggest changes in the VM has been the arrival of invokedynamic.

This new bytecode has opened the door to a rethinking of how JVM bytecode can be written.

There is now an attempt to extend the technology used in this opcode to provide even more flexibility to the platform.

For example, recall the distinction between ldc and const in “Overview of Bytecode Interpretation”. There is rather more to this than is obvious at first sight. Let’s look at a simple bit of code:

publicstaticfinalStringHELLO="Hello World";publicstaticfinaldoublePI=3.142;publicvoidshowConstsAndLdc(){Objecto=null;inti=-1;i=0;i=1;o=HELLO;doubled=0.0;d=PI;}

This produces the following rather straightforward bytecode sequence:

publicvoidshowConstsAndLdc();Code:0:aconst_null1:astore_12:iconst_m13:istore_24:iconst_05:istore_26:iconst_17:istore_28:ldc#3// String Hello World10:astore_111:dconst_012:dstore_313:ldc2_w#4// double 3.142d16:dstore_317:return

There are now also some extra entries that show up in the constant pool:

#3=String#29// Hello World#4=Double3.142d...#29=Utf8HelloWorld

The basic pattern is clear: the “true constants” show up as const instructions, while loads from the constant pool are represented by ldc instructions.

The former are a small finite set of constants, such as the primitives 0, 1, and null.

In contrast, any immutable value can be considered a constant for ldc, and recent Java versions have greatly increased the number of different constant types that can live in the constant pool.

For example, consider this piece of Java 7 (or above) code that makes use of the Method Handles API we met in “Method Handles”:

publicMethodHandlegetToStringMH()throwsNoSuchMethodException,IllegalAccessException{MethodTypemt=MethodType.methodType(String.class);MethodHandles.Lookuplk=MethodHandles.lookup();MethodHandlemh=lk.findVirtual(getClass(),"toString",mt);returnmh;}publicvoidcallMH(){try{MethodHandlemh=getToStringMH();Objecto=mh.invoke(this,null);System.out.println(o);}catch(Throwablee){e.printStackTrace();}}

To see the impact of method handles on the constant pool, let’s add this simple method to our previous trivial ldc and const example:

publicvoidmh()throwsException{MethodTypemt=MethodType.methodType(void.class);MethodHandlemh=MethodHandles.lookup().findVirtual(BytecodePatterns.class,"mh",mt);}

This produces the following bytecode:

publicvoidmh()throwsjava.lang.Exception;Code:0:getstatic#6// Field java/lang/Void.TYPE:Ljava/lang/Class;3:invokestatic#7// Method java/lang/invoke/MethodType.methodType:// (Ljava/lang/Class;)Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodType;6:astore_17:invokestatic#8// Method java/lang/invoke/MethodHandles.lookup:// ()Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodHandles$Lookup;10:ldc#2// class optjava/bc/BytecodePatterns12:ldc#9// String mh14:aload_115:invokevirtual#10// Method java/lang/invoke/MethodHandles$Lookup.// findVirtual:(Ljava/lang/Class;Ljava/lang/// String;Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodType;)Ljava/// lang/invoke/MethodHandle;18:astore_219:return}

This contains an additional ldc, for the BytecodePatterns.class literal, and a workaround for the void.class object (which must live as a houseguest in the java.lang.Void type).

However, class constants are only a little more interesting than strings or primitive constants.

This is not the whole story, and the impact on the constant pool once method handles are in play is very significant. The first place we can see this is in the appearance of some new types of pool entry:

#58=MethodHandle#6:#84// invokestatic java/lang/invoke/LambdaMetafactory.// metafactory:(Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodHandles// $Lookup;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/invoke/// MethodType;Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodType;Ljava/// lang/invoke/MethodHandle;Ljava/lang/invoke/// MethodType;)Ljava/lang/invoke/CallSite;#59=MethodType#22// ()V#60=MethodHandle#6:#85// invokestatic optjava/bc/BytecodePatterns.// lambda$lambda$0:()V

These new types of constant are required to support invokedynamic, and the direction of the platform since Java 7 has been to make greater and greater use of the technology.

The overall aim is to make calling a method via invokedynamic as performant and JIT-friendly as the typical invokevirtual calls.

Other directions for future work include the possibility of a “constant dynamic” capability—an analog of invokedynamic, but for constant pool entries that are unresolved at link time but calculated when first encountered.

It is expected that this area of the JVM will continue to be a very active topic of research in forthcoming Java versions.

Future Directions in Concurrency

As we discussed in Chapter 2, one of Java’s major innovations was to introduce automatic memory management. These days, virtually no developer would even try to defend the manual management of memory as a positive feature that any new programming language should use.

We can see a partial mirror of this in the evolution of Java’s approach to concurrency. The original design of Java’s threading model is one in which all threads have to be explicitly managed by the programmer, and mutable state has to be protected by locks in an essentially cooperative design. If one section of code does not correctly implement the locking scheme, it can damage object state.

Note

This is expressed by the fundamental principle of Java threading: “Unsynchronized code does not look at or care about the state of locks on objects and can access or damage object state at will.”

As Java has evolved, successive versions have moved away from this design and toward higher-level, less manual, and generally safer approaches—effectively toward runtime-managed concurrency.

One aspect of this is the recently announced Project Loom. This project deals with supporting JVM concurrency at a lower level than has been done on the JVM until now. The essential problem with core Java threads is that every thread has a stack. These are expensive and are not endlessly scalable; once we have, say, 10,000 threads, the memory that is devoted to them amounts to gigabytes.

One solution is to take a step back and consider a different approach: execution units that are not directly schedulable by the operating system, have a lower overhead, and may be “mostly idle” (i.e., don’t need to be executing a high percentage of the wallclock time).

This chimes well with the approach taken by other languages (both JVM-based and not). In many cases they have lower-level cooperative constructs, such as goroutines, fibers, and continuations. These abstractions must be cooperative rather than pre-emptive, as they are operating below the visibility of the operating system and do not constitute schedulable entities in their own right.

Following this approach requires two basic components: a representation of the called code (e.g., as a Runnable or similar type) and a scheduler component.

Ironically, the JVM has had a good scheduling component for these abstractions since version 7, even if the other parts were not in place.

The Fork/Join API (described in “Fork/Join”) arrived in Java 7 and was based on two concepts—the idea of recursive decomposition of executable tasks and that of work stealing, where idle threads can take work from the queues of busier threads.

The ForkJoinPool executor is at the heart of these two concepts, and is responsible for implementing the work-stealing algorithm.

It turns out that recursive decomposition is not all that useful for most tasks.

However, the executor thread pool with work stealing can be applied to many different situations.

For example, the Akka actor framework has adopted ForkJoinPool as its executor.

It is still very early days for Project Loom, but it seems entirely possible that the ForkJoinPool executor will also be used as the scheduling component for these lightweight execution objects.

Once again, standardizing this capability into the VM and core libraries greatly reduces the need to use external libraries.

Conclusion

Java has changed a huge amount since its initial release. From not being explicitly designed as a high-performance language, it has very much become one. The core Java platform, community, and ecosystem have remained healthy and vibrant even as Java has expanded into new areas of applicability.

Bold new initiatives, such as Project Metropolis and Graal, are reimagining the core VM.

invokedynamic has enabled HotSpot to break out of its evolutionary niche and reinvent itself for the next decade.

Java has shown that it is not afraid to undertake ambitious changes, such as adding value types and returning to tackle the complex issue of generics.

Java/JVM performance is a very dynamic field, and in this chapter we have seen that advances are still being made in a large number of areas. There are numerous other projects that we did not have time to mention, including Java/native code interaction (Project Panama) and new garbage collectors such as Oracle’s ZGC.

As a result, this book is nowhere near complete, as there is simply so much to comprehend as a performance engineer. Nevertheless, we hope that it has been a useful introduction to the world of Java performance and has provided some signposts for readers on their own performance journey.