Chapter 12. Concurrent Performance Techniques

In the history of computing to date, software developers have typically written code in a sequential format. Programming languages and hardware generally only supported the ability to process one instruction at a time. In many situations a so-called “free lunch” was enjoyed, where application performance would improve with the purchase of the latest hardware. The increase in transistors available on a chip led to better and more capable processors.

Many readers will have experienced the situation where moving the software to a bigger or a newer box was the solution to capacity problems, rather than paying the cost of investigating the underlying issues or considering a different programming paradigm.

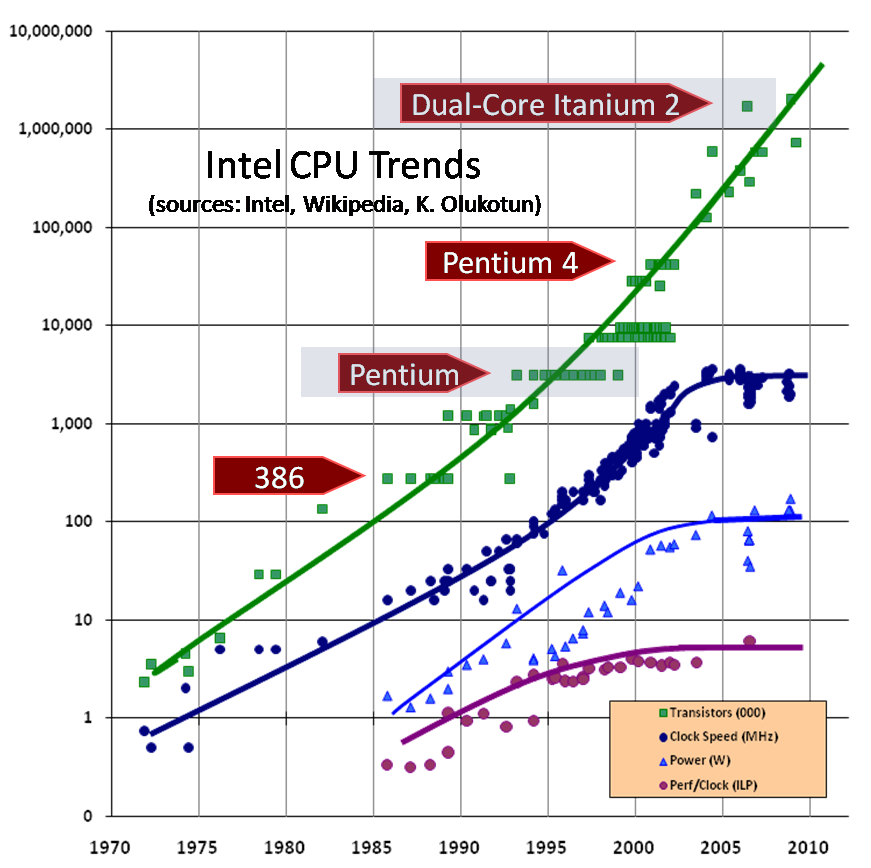

Moore’s Law originally predicted the number of transistors on a chip would approximately double each year. Later the estimate was refined to every 18 months. Moore’s Law held fast for around 50 years, but it has started to falter. The momentum we have enjoyed for 50 years is increasingly difficult to maintain. The impact of the technology running out of steam can be seen in Figure 12-1, a central pillar of “The Free Lunch Is Over,” an article written by Herb Sutter that aptly describes the arrival of the modern era of performance analysis.1

Figure 12-1. The Free Lunch Is Over (Sutter, 2005)

We now live in a world where multicore processors are commonplace. Well-written applications can (and increasingly, must) take advantage of distributing application processing over multiple cores. Application execution platforms such as the JVM are at a distinct advantage. This is because there are always VM threads that can take advantage of multiple processor cores for operations such as JIT compilation. This means that even JVM applications that only have a single application thread benefit from multicore.

To make full use of current hardware, the modern Java professional must have at least a basic grounding in concurrency and its implications for application performance. This chapter is a basic overview but is not intended to provide complete coverage of Java concurrency. Instead, a guide such as Java Concurrency in Practice by Brian Goetz et al. (Addison-Wesley Professional) should be consulted in addition to this discussion.

Introduction to Parallelism

For almost 50 years, single-core speed increased, and then around 2005 it began to plateau at about 3 GHz clock speed. In today’s multicore world, however, Amdahl’s Law has emerged as a major consideration for improving the execution speed of a computation task.

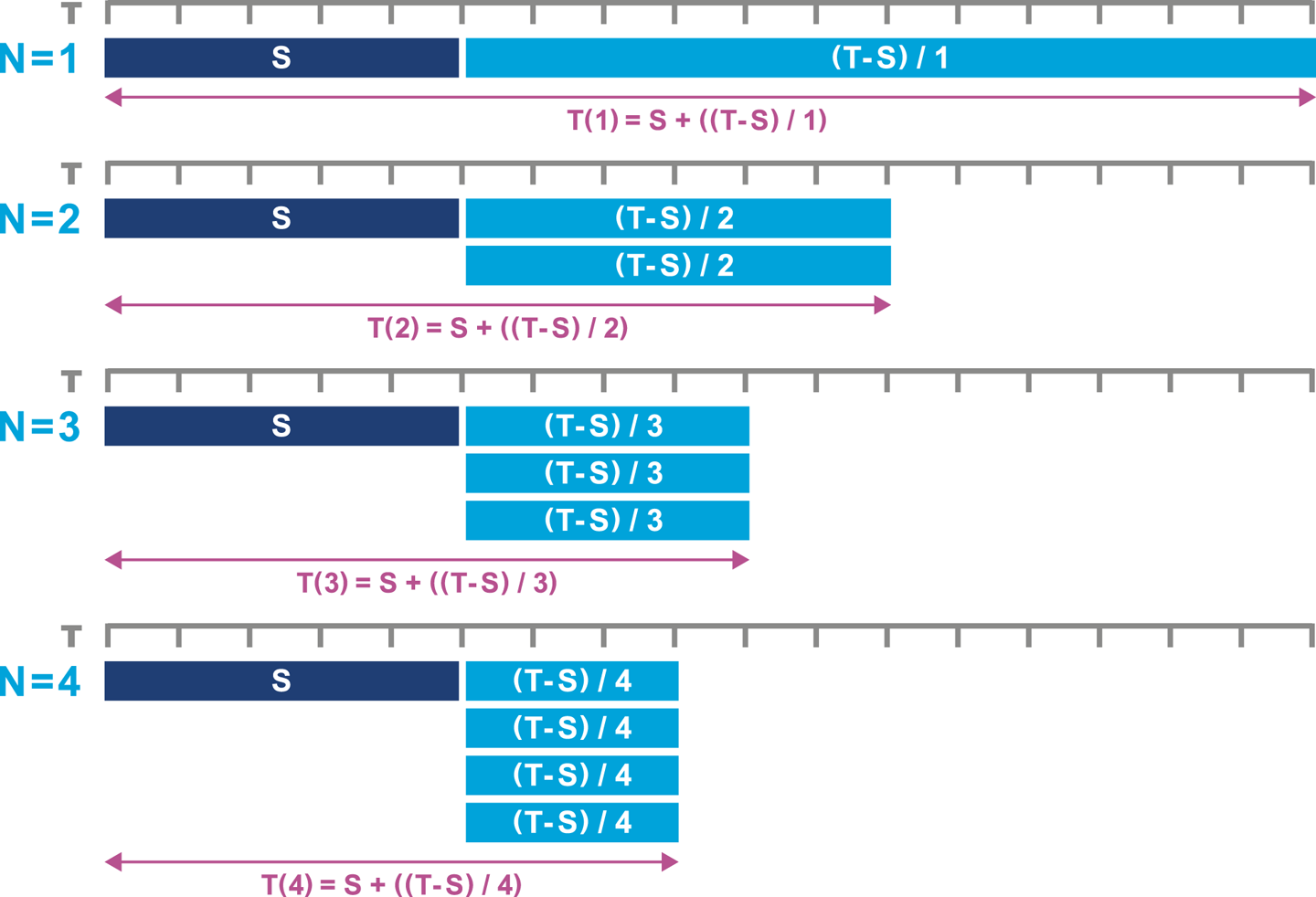

We introduced Amdahl’s Law in “Reading Performance Graphs”, but we now need a more formal description. Consider a computing task that can be divided up into two parts—one part that can be executed in parallel, and one that has to run serially (for, e.g., collating results, or dispatching units of work for parallel execution).

Let’s refer to the serial part as S and the total time needed for the task as T.

We can use as many processors as we like for the task, so we denote the number of processors as N.

This means that we should write T as a function of the number of processors, T(N).

The concurrent part of the work is T - S, and if this can be shared equally among N processors, the overall time taken for the task is:

T(N) = S + (1/N) * (T - S)

This means that no matter how many processors are used, the total time taken can never be less than the serial time. So, if the serial overhead is, say, 5% of the total, then no matter how many cores are used, the effective speedup will never be more than 20x. This insight and formula is the underlying theory behind the introductory discussion of Amdahl’s Law in Chapter 1. The impact can be seen in another way in Figure 12-2.

Figure 12-2. Amdahl’s Law revisited

Only improvements in single-threaded performance, such as faster cores, can reduce the value of S.

Unfortunately, trends in modern hardware mean that CPU clock speeds are no longer improving by any meaningful amount.

As a consequence of single-core processors no longer getting faster, Amdahl’s Law is often the practical limit of software scaling.

One corollary of Amdahl’s Law is that if no communication between parallel tasks or other sequential processing is necessary, then unlimited speedup is theoretically possible. This class of workloads is known as embarrassingly parallel, and in this case, concurrent processing is fairly straightforward to achieve.

The usual approach is to subdivide the workload between multiple worker threads without any shared data. Once shared state or data is introduced between threads, the workload increases in complexity and inevitably reintroduces some serial processing and communication overhead.

Writing correct programs is hard; writing correct concurrent programs is harder. There are simply more things that can go wrong in a concurrent program than in a sequential one.

Java Concurrency in Practice, Brian Goetz et al. (Addison-Wesley Professional)

In turn, this means that any workload with shared state requires correct protection and control. For workloads that run on the JVM, the platform provides a set of memory guarantees called the Java Memory Model (JMM). Let’s look at some simple examples that explain the problems of Java concurrency before introducing the model in some depth.

Fundamental Java Concurrency

One of the first lessons learned about the counterintuitive nature of concurrency is the realization that incrementing a counter is not a single operation. Let’s take a look:

publicclassCounter{privateinti=0;publicintincrement(){returni=i+1;}}

Analyzing the bytecode for this produces a series of instructions that result in loading, incrementing, and storing the value:

publicintincrement();Code:0:aload_01:aload_02:getfield#2// Field i:I5:iconst_16:iadd7:dup_x18:putfield#2// Field i:I11:ireturn

If the counter is not protected by an appropriate lock and is accessed in a multithreaded way, it is possible a load could happen before another thread is stored. This problem results in lost updates.

To see this in more detail, consider two threads, A and B, that are both calling the increment() method on the same object.

For simplicity’s sake, suppose they are running on a machine with a single CPU and that the bytecode accurately represents low-level execution (so, no reordering, cache effects, or other details of real processors).

Note

As the operating system scheduler causes context switching of the threads at nondeterministic times, many different sequences of bytecodes are possible with even just two threads.

Suppose the single CPU executes the bytecodes as shown (note that there is a well-defined order of execution for the instructions, which would not be the case on an actual multiprocessor system):

A0:aload_0A1:aload_0A2:getfield#2// Field i:IA5:iconst_1A6:iaddA7:dup_x1B0:aload_0B1:aload_0B2:getfield#2// Field i:IB5:iconst_1B6:iaddB7:dup_x1A8:putfield#2// Field i:IA11:ireturnB8:putfield#2// Field i:IB11:ireturn

Each thread will have a private evaluation stack from its individual entry into the method, so only the operations on fields can interfere with each other (because the object fields are located in the heap, which is shared).

The resulting behavior is that, if the initial state of i is 7 before either A or B starts executing, then if the execution order is precisely as just shown, both calls will return 8 and the field state will be updated to 8, despite the fact that increment() was called twice.

Warning

This issue is caused by nothing other than OS scheduling—no hardware trickery was required to surface this problem, and it would be an issue even on a very old CPU without modern features.

A further misconception is that adding the keyword volatile will make the increment operation safe.

By forcing the value to always be reread by the cache, volatile guarantees that any updates will be seen by another thread.

However, it does not prevent the lost update problem just shown, as it is due to the composite nature of the increment operator.

The following example shows two threads sharing a reference to the same counter:

packageoptjava;publicclassCounterExampleimplementsRunnable{privatefinalCountercounter;publicCounterExample(Countercounter){this.counter=counter;}@Overridepublicvoidrun(){for(inti=0;i<100;i++){System.out.println(Thread.currentThread().getName()+" Value: "+counter.increment());}}}

The counter is unprotected by synchronized or an appropriate lock.

Each time a program runs, the execution of the two threads can potentially interleave in different ways.

On some occasions the code will run as expected and the counter will increment fine.

This is down to the programmer’s dumb luck!

On other occasions the interleaving may show repeated values in the counter due to lost updates, as seen here:

Thread-1 Value: 1 Thread-1 Value: 2 Thread-1 Value: 3 Thread-0 Value: 1 Thread-1 Value: 4 Thread-1 Value: 6 Thread-0 Value: 5

In other words, a concurrent program that runs successfully most of the time is not the same thing as a correct concurrent program. Proving it fails is as difficult as proving it is correct; however, it is sufficient to find one example of failure to demonstrate it is not correct.

To make matters worse, reproducing bugs in concurrent code can be extremely difficult. Dijkstra’s famous maxim that “testing shows the presence, not the absence of bugs” applies to concurrent code even more strongly than to single-threaded applications.

To solve the aforementioned problems, we could use synchronized to control the updating of a simple value such as an int—and before Java 5, that was the only choice.

The problem with using synchronization is that it requires some careful design and up-front thought. Without this, just adding synchronization can slow down the program rather than speeding it up.

This is counter to the whole aim of adding concurrency: to increase throughput. Accordingly, any exercise to parallelize a code base must be supported by performance tests that fully prove the benefit of the additional complexity.

Note

Adding synchronization blocks, especially if they are uncontended, is a lot cheaper than in older versions of the JVM (but should still not be done if not necessary). More details can be found in “Locks and Escape Analysis”.

To do better than just a shotgun approach to synchronization, we need an understanding of the JVM’s low-level memory model and how it applies to practical techniques for concurrent applications.

Understanding the JMM

Java has had a formal model of memory, the JMM, since version 1.0. This model was heavily revised and some problems were fixed in JSR 133,2 which was delivered as part of Java 5.

In the Java specifications the JMM appears as a mathematical description of memory. It has a somewhat formidable reputation, and many developers regard it as the most impenetrable part of the Java specification (except, perhaps, for generics).

The JMM seeks to provide answers to questions such as:

-

What happens when two cores access the same data?

-

When are they guaranteed to see the same value?

-

How do memory caches affect these answers?

Anywhere shared state is accessed, the platform will ensure that the promises made in the JMM are honored. These promises fall into two main groups: guarantees related to ordering and those concerned with visibility of updates across threads.

As hardware has moved from single-core to multicore to many-core systems, the nature of the memory model has become increasingly important. Ordering and thread visibility are no longer theoretical issues, but are now practical problems that directly impact the code of working programmers.

At a high level, there are two possible approaches that a memory model like the JMM might take:

- Strong memory model

-

All cores always see the same values at all times.

- Weak memory model

-

Cores may see different values, and there are special cache rules that control when this may occur.

From the programming point of view, a strong memory model seems very appealing—not least because it doesn’t require programmers to take any extra care when writing application code.

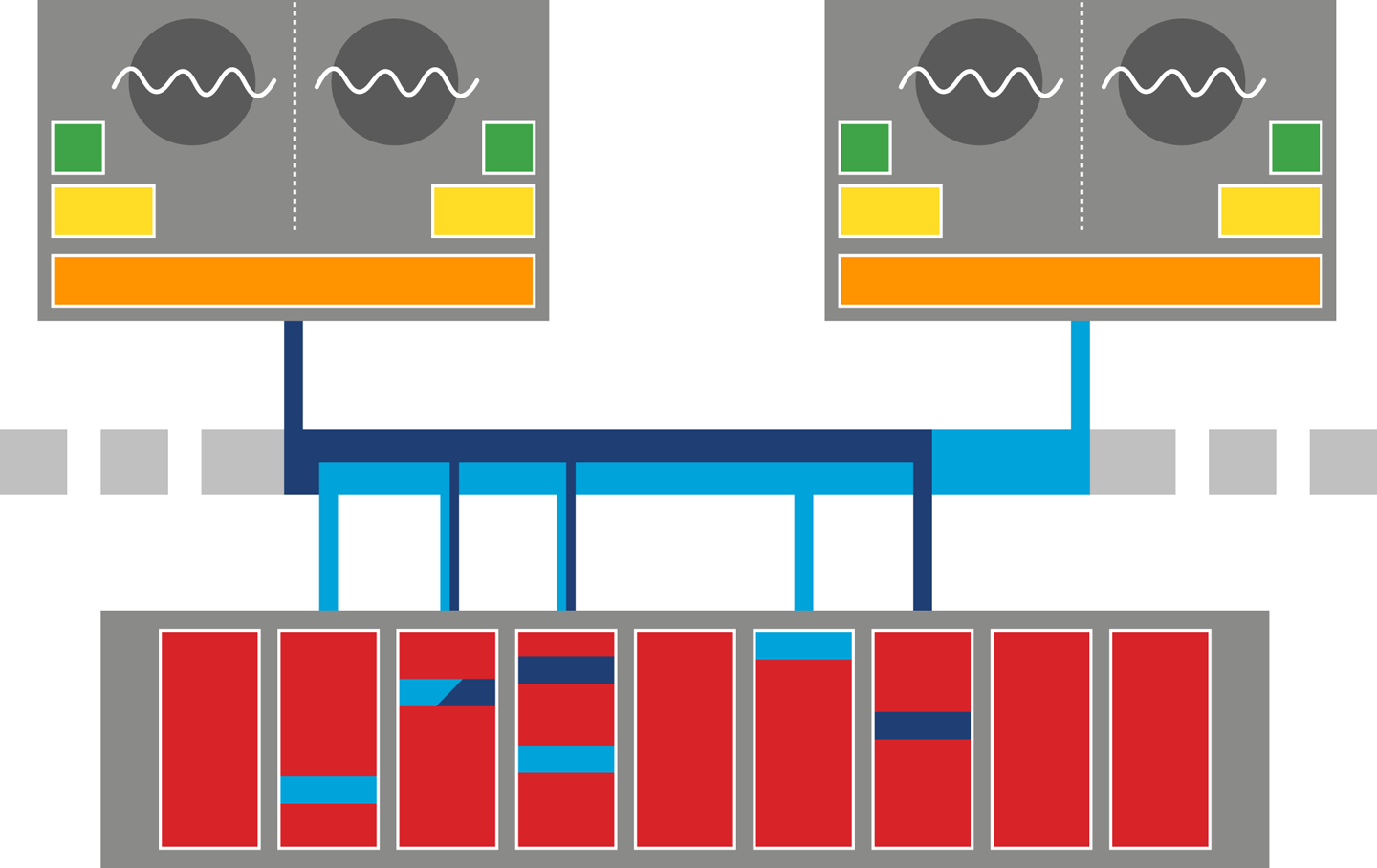

In Figure 12-3, we can see a (greatly) simplified view of a modern multi-CPU system. We saw this view in Chapter 3 and again in Chapter 7 (where it was discussed in the context of NUMA architectures).

Figure 12-3. Modern multi-CPU system

If a strong memory model were to be implemented on top of this hardware, this would be equivalent to a writeback approach to memory. Notification of cache invalidation would swamp the memory bus, and effective transfer rates to/from main memory would nosedive. This problem would only get worse as the number of cores increases, which makes this approach fundamentally unsuitable for the many-core world.

It is also worth remembering that Java is designed to be an architecture-independent environment. This means that if the JVM were to specify a strong memory model, it would require additional implementation work to be done in software running on top of hardware that does not support a strong memory model natively. In turn, this would greatly increase the porting work required to implement a JVM on top of weak hardware.

In reality, the JMM has a very weak memory model. This fits better with trends in real CPU architecture, including MESI (described in “Memory Caches”). It also makes porting easier, as the JMM makes few guarantees.

It is very important to realize that the JMM is a minimum requirement only. Real JVM implementations and CPUs may do more than the JMM requires, as discussed in “Hardware Memory Models”.

This can lead to application developers being lulled into a false sense of security. If an application is developed on a hardware platform with a stronger memory model than the JMM, then undiscovered concurrency bugs can survive—because they do not manifest in practice due to hardware guarantees. When the same application is deployed onto weaker hardware, the concurrency bugs may become a problem as the application is no longer being protected by the hardware.

The guarantees provided by the JMM are based upon a set of basic concepts:

- Happens-Before

- Synchronizes-With

-

The event will cause its view of an object to be synchronized with main memory.

- As-If-Serial

-

Instructions appear to execute in order outside of the executing thread.

- Release-Before-Acquire

-

Locks will be released by one thread before being acquired by another.

One of the most important techniques for handling shared mutable state is locking via synchronization. It is a fundamental part of the Java view of concurrency, and we will need to discuss it in some depth to work adequately with the JMM.

Warning

For developers who are interested in performance, a passing acquaintance with the Thread class and the language-level basic primitives of Java’s concurrency mechanism is not enough.

In this view, threads have their own description of an object’s state, and any changes made by the thread have to be flushed to main memory and then reread by any other threads that are accessing the same data. This fits well with the write-behind view of hardware as discussed in the context of MESI, but in the JVM there is a considerable amount of implementation code that wraps the low-level memory access.

From this standpoint, it is immediately clear what the Java keyword synchronized refers to: it means that the local view of the thread holding the monitor has been Synchronized-With main memory.

Synchronized methods and blocks define touchpoints where threads must perform syncing. They also define blocks of code that must fully complete before other synchronized blocks or methods can start.

The JMM does not have anything to say about unsynchronized access. There are no guarantees about when, if ever, changes made on one thread will become visible to other threads. If such guarantees are required, then the write access must be protected by a synchronized block, triggering a writeback of the cached values to main memory. Similarly, the read access must also be contained within a synchronized section of code, to force a reread from memory.

Prior to the arrival of modern Java concurrency, using the Java keyword synchronized was the only mechanism of guaranteeing ordering and visibility of data across multiple threads.

The JMM enforces this behavior and offers various guarantees that can be assumed about Java and memory safety.

However, the traditional Java synchronized lock has several limitations, which have become increasingly severe:

-

All

synchronizedoperations on the locked object are treated equally. -

Lock acquiring and releasing must be done on a method level or within a

synchronizedblock within a method. -

Either the lock is acquired or the thread is blocked; there is no way to attempt to acquire the lock and carry on processing if the lock cannot be obtained.

A very common mistake is to forget that operations on locked data must be treated equitably.

If an application uses synchronized only on write operations, this can lead to lost updates.

For example, it might seem as though a read does not need to lock, but it must use synchronized to guarantee visibility of updates coming from other threads.

Note

Java synchronization between threads is a cooperative mechanism and it does not work correctly if even one participating thread does not follow the rules.

One resource for newcomers to the JMM is the JSR-133 Cookbook for Compiler Writers. This contains a simplified explanation of JMM concepts without overwhelming the reader with detail.

For example, as part of the treatment of the memory model a number of abstract barriers are introduced and discussed. These are intended to allow JVM implementors and library authors to think about the rules of Java concurrency in a relatively CPU-independent way.

The rules that the JVM implementations must actually follow are detailed in the Java specifications. In practice, the actual instructions that implement each abstract barrier may well be different on different CPUs. For example, the Intel CPU model automatically prevents certain reorderings in hardware, so some of the barriers described in the cookbook are actually no-ops.

One final consideration: the performance landscape is a moving target. Neither the evolution of hardware nor the frontiers of concurrency have stood still since the JMM was created. As a result, the JMM’s description is an inadequate representation of modern hardware and memory.

In Java 9 the JMM has been extended in an attempt to catch up (at least partially) to the reality of modern systems. One key aspect of this is compatibility with other programming environments, especially C++11, which adapted ideas from the JMM and then extended them. This means that the C++11 model provides definitions of concepts outside the scope of the Java 5 JMM (JSR 133). Java 9 updates the JMM to bring some of those concepts to the Java platform and to allow low-level, hardware-conscious Java code to interoperate with C++11 in a consistent manner.

To delve deeper into the JMM, see Aleksey Shipilёv’s blog post “Close Encounters of the Java Memory Model Kind”, which is a great source of commentary and very detailed technical information.

Building Concurrency Libraries

Despite being very successful, the JMM is hard to understand and even harder to translate into practical usage. Related to this is the lack of flexibility that intrinsic locking provides.

As a result, since Java 5, there has been an increasing trend toward standardizing high-quality concurrency libraries and tools as part of the Java class library and moving away from the built-in language-level support. In the vast majority of use cases, even those that are performance-sensitive, these libraries are more appropriate than creating new abstractions from scratch.

The libraries in java.util.concurrent have been designed to make writing multithreaded applications in Java a lot easier.

It is the job of a Java developer to select the level of abstraction that best suits their requirements, and it is a fortunate confluence that selecting the well-abstracted libraries of java.util.concurrent will also yield better “thread hot” performance.

The core building blocks provided fall into a few general categories:

-

Locks and semaphores

-

Atomics

-

Blocking queues

-

Latches

-

Executors

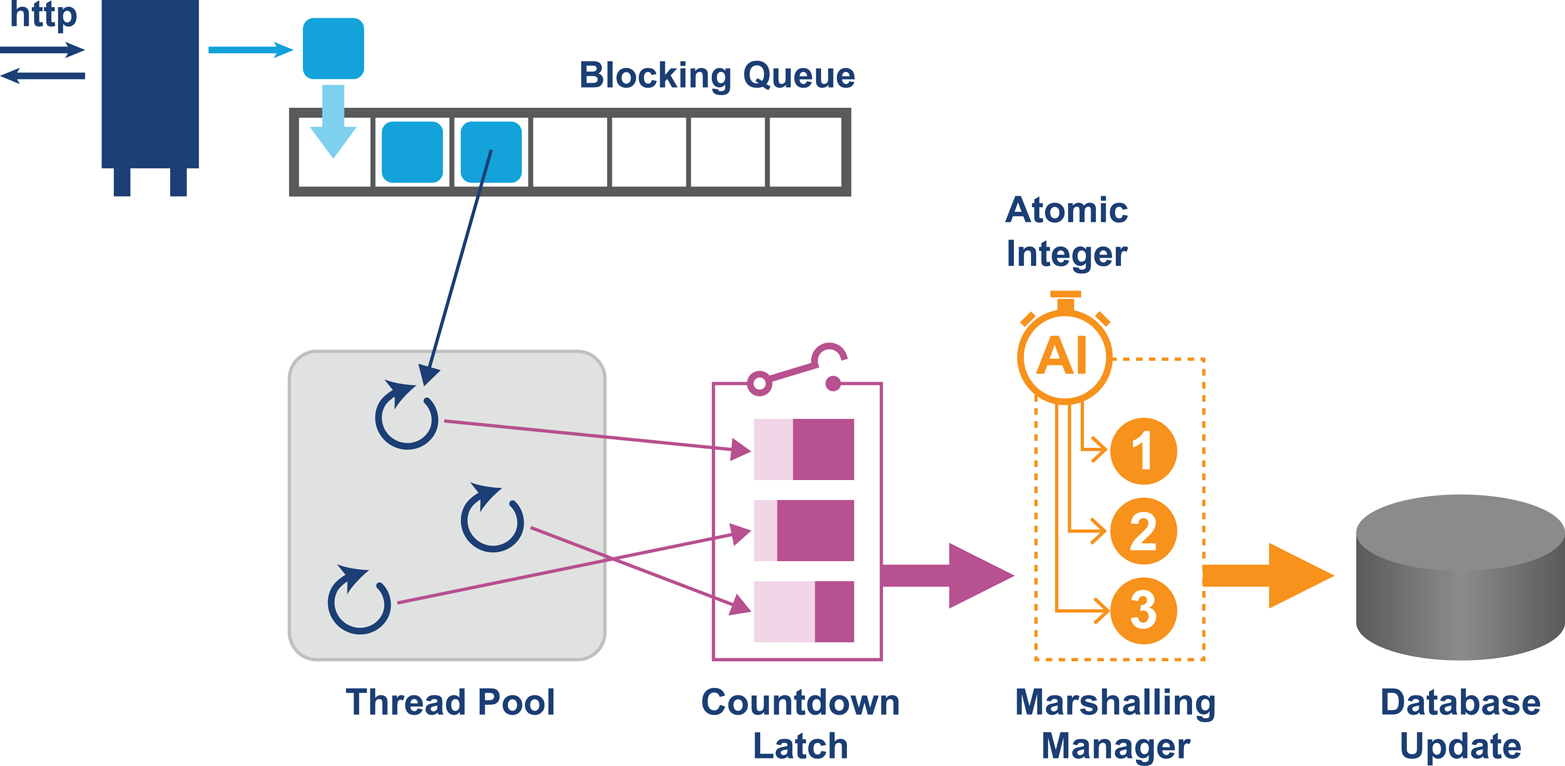

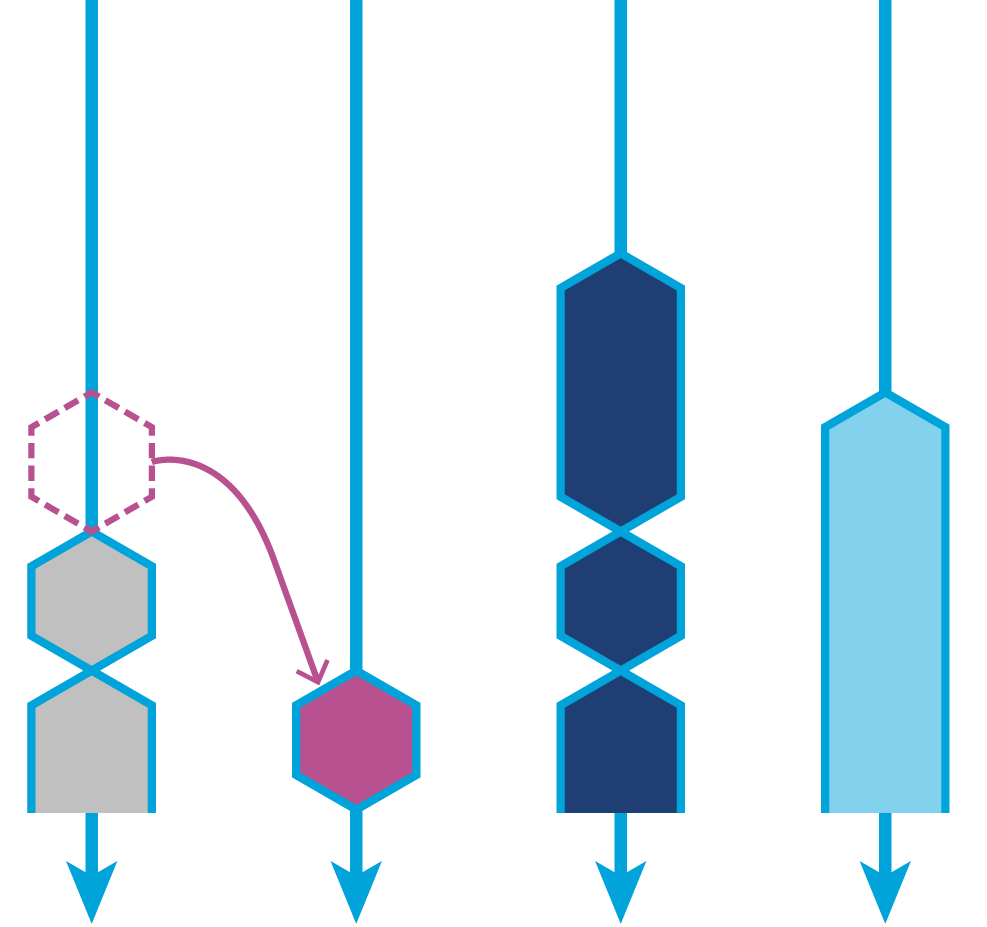

In Figure 12-4, we can see a representation of a typical modern concurrent Java application that is built up from concurrency primitives and business logic.

Figure 12-4. Example concurrent application

Some of these building blocks are discussed in the next section, but before we review them, let’s take a look at some of the main implementation techniques used in the libraries. An understanding of how the concurrent libraries are implemented will allow performance-conscious developers to make the best use of them. For developers operating at the extreme edge, knowing how the libraries work will give teams who have outgrown the standard library a starting point for choosing (or developing) ultra-high-performance replacements.

In general, the libraries try to move away from relying upon the operating system and instead work more in user space where possible. This has a number of advantages, not least of which is that the behavior of the library is then hopefully more globally consistent, rather than being at the mercy of small but important variations between Unix-like operating systems.

Some of the libraries (notably locks and atomics) rely on low-level processor instructions and operating system specifics to implement a technique known as Compare and Swap (CAS).

This technique takes a pair of values, the “expected current value” and the “wanted new value,” and a memory location (a pointer). As an atomic unit, two operations occur:

-

The expected current value is compared with the contents of the memory location.

-

If they match, the current value is swapped with the wanted new value.

CAS is a basic building block for several crucial higher-level concurrency features, and so this is a classic example of how the performance and hardware landscape has not stood still since the JMM was produced.

Despite the fact that the CAS feature is implemented in hardware on most modern processors, it does not form part of the JMM or the Java platform specification.

Instead, it must be treated as an implementation-specific extension, and so access to CAS hardware is provided via the sun.misc.Unsafe class.

Unsafe

sun.misc.Unsafe is an internal implementation class, and as the package name suggests, it is not part of the standard API of the Java platform.

Therefore, it is generally not to be used by application developers directly; the clue is in the class name.

Any code that does use it is technically directly coupled to the HotSpot VM, and is potentially fragile.

Tip

Unsafe is an unsupported, internal API and so technically could be withdrawn or modified at any time, without regard to user applications.

It has been placed in the module jdk.unsupported in Java 9, as we will discuss later.

However, Unsafe has become a key part of the implementation of basically every major framework in one way or another.

It provides ways to break the standard behavior of the JVM.

For example, Unsafe allows such possibilities as:

-

Allocate an object, but don’t run its constructor.

-

Access raw memory and the equivalent of pointer arithmetic.

-

Use processor-specific hardware features (such as CAS).

These operations enable high-level framework features such as:

-

Fast (de-)serialization

-

Thread-safe native memory access (for example, off-heap or 64-bit indexed access)

-

Atomic memory operations

-

Efficient object/memory layouts

-

Custom memory fences

-

Fast interaction with native code

-

A multi–operating system replacement for JNI

-

Access to array elements with volatile semantics

While Unsafe is not an official standard for Java SE, its widespread popular usage in the industry has made it a de facto standard.

In addition, it has become something of a dumping ground for nonstandard but necessary features.

This landscape has been affected by the arrival of Java 9, however, and is expected to evolve significantly over the next few versions of Java.

Let’s take a look at CAS in action, by exploring the atomic classes that were introduced with Java 5.

Atomics and CAS

Atomics have composite operations to add, increment, and decrement, which combine with a get() to return the affected result.

This means that an operation to increment on two separate threads will return currentValue + 1 and currentValue + 2.

The semantics of atomic variables are an extension of volatile, but they are more flexible as they can perform state-dependent updates safely.

Atomics do not inherit from the base type they wrap, and do not allow direct replacement.

For example, AtomicInteger does not extend Integer—for one thing, java.lang.Integer is (rightly) a final class.

Let’s look at how Unsafe provides the implementation of a simple atomic call:

publicclassAtomicIntegerExampleextendsNumber{privatevolatileintvalue;// setup to use Unsafe.compareAndSwapInt for updatesprivatestaticfinalUnsafeunsafe=Unsafe.getUnsafe();privatestaticfinallongvalueOffset;static{try{valueOffset=unsafe.objectFieldOffset(AtomicIntegerExample.class.getDeclaredField("value"));}catch(Exceptionex){thrownewError(ex);}}publicfinalintget(){returnvalue;}publicfinalvoidset(intnewValue){value=newValue;}publicfinalintgetAndSet(intnewValue){returnunsafe.getAndSetInt(this,valueOffset,newValue);}// ...

This relies on some methods from Unsafe, and the key methods here are native and involve calling into the JVM:

publicfinalintgetAndSetInt(Objecto,longoffset,intnewValue){intv;do{v=getIntVolatile(o,offset);}while(!compareAndSwapInt(o,offset,v,newValue));returnv;}publicnativeintgetIntVolatile(Objecto,longoffset);publicfinalnativebooleancompareAndSwapInt(Objecto,longoffset,intexpected,intx);

The sample demonstrates the usage of a loop within Unsafe to repeatedly retry a CAS operation.

It is vital for effective use of atomics that developers use the facilities provided and do not roll their own implementations of, say, an atomic increment operation using a loop, as the Unsafe implementation will already utilize that technique internally.

Atomics are lock-free and therefore cannot deadlock. Often atomics are accompanied by an internal retry loop, to deal with the situation of failure to compare and update. Usually this occurs when another thread just performed an update.

This retry loop produces a linear degradation of performance if multiple retries are required to update the variable. When considering performance, it is important to monitor the contention level to ensure throughput levels remain high.

Using Unsafe to provide access to lower-level hardware instructions is interesting, as Java usually allows the developer to be completely abstracted away from the machine.

However, in this case the access to machine instructions is critical to enforcing the desired semantics of the atomic classes.

Locks and Spinlocks

The intrinsic locks that we have met up until now work by invoking the operating system in user code. The OS is used to put a thread into an indefinite wait until signaled. This can be a huge overhead if the contended resource is only in use for a very short period of time. In this case, it may be much more efficient to have the blocked thread stay active on a CPU, accomplish no useful work, and “burn CPU” retrying the lock until it becomes available.

This technique is known as a spinlock and is intended to be more lightweight than a full mutual-exclusion lock. In modern systems, spinlocks are usually implemented with CAS, assuming that the hardware supports it. Let’s look at a simple example in low-level x86 assembly:

locked:dd0spin_lock:moveax,1xchgeax,[locked]testeax,eaxjnzspin_lockretspin_unlock:moveax,0xchgeax,[locked]ret

The exact implementation of a spinlock varies between CPUs, but the core concept is the same on all systems:

-

The “test and set” operation—implemented here by

xchg—must be atomic. -

If there is contention for the spinlock, processors that are waiting execute a tight loop.

CAS essentially allows the safe updating of a value in one instruction if the expected value is correct. This helps us to form the building blocks for a lock.

Summary of Concurrent Libraries

We’ve seen an introduction to the low-level implementation techniques used to enable atomic classes and simple locks. Now, let’s take a look at how the standard library uses these capabilities to create fully featured production libraries for general-purpose use.

Locks in java.util.concurrent

Java 5 reimagined locks and added a more general interface for a lock in java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock.

This interface offers more possibilities than the behavior of intrinsic locks:

lock()-

Traditionally acquires the lock and will block until the lock is available.

newCondition()-

Creates conditions around the lock, which allows the lock to be used in a more flexible way. Allows a separation of concerns within the lock (e.g., a read and a write).

tryLock()-

Tries to acquire the lock (with an optional timeout), allowing for a thread to continue the process in the situation where the lock does not become available.

unlock()-

Releases the lock. This is the corresponding call following a

lock().

In addition to allowing different types of locks to be created, locks can now also span multiple methods, as it is possible to lock in one method and unlock in another.

If a thread wants to acquire a lock in a nonblocking manner, it is able to do so using the tryLock() method and back out if the lock is not available.

The ReentrantLock is the main implementation of Lock, and basically uses a compareAndSwap() with an int.

This means that the acquisition of the lock is lock-free in the uncontended case.

This can dramatically increase the performance of a system where there is less lock contention, while also providing the additional flexibility of different locking policies.

Tip

The idea of a thread being able to reacquire the same lock is known as re-entrant locking, and this prevents a thread from blocking itself. Most modern application-level locking schemes are re-entrant.

The actual calls to compareAndSwap() and the usage of Unsafe can be found in the static subclass Sync, which is an extension to AbstractQueuedSynchronizer.

AbstractQueuedSynchronizer also makes use of the LockSupport class, which has methods that allow threads to be parked and resumed.

The LockSupport class works by issuing permits to threads, and if there isn’t a permit available a thread must wait.

The idea of permits is similar to the concept of issuing permits in semaphores, but here there is only a single permit (a binary semaphore).

If a permit is not available a thread will be parked, and once a valid permit is available the thread will be unparked.

The methods of this class replace the long-deprecated methods of Thread.suspend() and Thread.resume().

There are three forms of park() that influence the following basic pseudocode.

while(!canProceed()){...LockSupport.park(this);}}

They are:

park(Object blocker)-

Blocks until another thread calls

unpark(), the thread is interrupted, or a spurious wakeup occurs. parkNanos(Object blocker, long nanos)-

Behaves the same as

park(), but will also return once the specified nano time elapses. parkUntil(Object blocker, long deadline)-

Is similar to

parkNanos(), but also adds a timeout to the scenarios that will cause the method to return.

Read/Write Locks

Many components in applications will have an imbalance between the number of read operations and write operations.

Reads don’t change the state, whereas write operations will.

Using the traditional synchronized or ReentrantLock (without conditions) will follow a single lock strategy.

In situations like caching, where there may be many readers and a single writer, the data structure may spend a lot of time unnecessarily blocking the readers due to another read.

The ReentrantReadWriteLock class exposes a ReadLock and a WriteLock that can be used within code.

The advantage is that multiple threads reading do not cause other reading threads to block. The only operation that will block is a write. Using this locking pattern where the number of readers is high can significantly improve thread throughput and reduce locking. It is also possible to set the lock into “fair mode,” which degrades performance but ensures threads are dealt with in order.

The following implementation for AgeCache would be a significant improvement over a version that uses a single lock:

packageoptjava.ch12;importjava.util.HashMap;importjava.util.Map;importjava.util.concurrent.locks.Lock;importjava.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantReadWriteLock;publicclassAgeCache{privatefinalReentrantReadWriteLockrwl=newReentrantReadWriteLock();privatefinalLockreadLock=rwl.readLock();privatefinalLockwriteLock=rwl.writeLock();privateMap<String,Integer>ageCache=newHashMap<>();publicIntegergetAge(Stringname){readLock.lock();try{returnageCache.get(name);}finally{readLock.unlock();}}publicvoidupdateAge(Stringname,intnewAge){writeLock.lock();try{ageCache.put(name,newAge);}finally{writeLock.unlock();}}}

However, we could make it even more optimal by considering the underlying data structure. In this example a concurrent collection would be a more sensible abstraction and yield greater thread hot benefits.

Semaphores

Semaphores offer a unique technique for allowing access to a number of available resources—for instance, threads in a pool or database connection objects. A semaphore works on the premise that “at most X objects are allowed access” and functions by having a set number of permits to control access:

// Semaphore with 2 permits and a fair modelprivateSemaphorepoolPermits=newSemaphore(2,true);

Semaphore::acquire() reduces the number of available permits by one, and if there are no permits available will block. Semaphore::release() returns a permit and will release a waiting acquirer if there is one. Because semaphores are often used in a way where resources are potentially blocked or queued, it is most likely that a semaphore will be initialized as fair to avoid thread starvation.

A one-permit semaphore (binary semaphore) is equivalent to a mutex, but with one distinct difference. A mutex can only be released by a thread that the mutex is locked on, whereas a semaphore can be released by a nonowning thread. A scenario where this might be necessary would be forcing the resolution of a deadlock. Semaphores also have the advantage of being able to ask for and release multiple permits. If multiple permits are being used, it is essential to use fair mode; otherwise, there is an increased chance of thread starvation.

Concurrent Collections

In Chapter 11 we explored optimizations that could be considered for Java collections. Since Java 5, there have been implementations of the collections interfaces that have been specifically designed for concurrent uses. These concurrent collections have been modified and improved over time to give the best possible thread hot performance.

For example, the map implementation (ConcurrentHashMap) uses a split into buckets or segments, and we can take advantage of this structure to achieve real gains in performance. Each segment can have its own locking policy—that is, its own series of locks. Having both a read and a write lock enables many readers to be reading across the ConcurrentHashMap, and if a write is required the lock only needs to be on that single segment.

Readers generally do not lock and can overlap safely with put()- and remove()-style operations.

Readers will observe the happens-before ordering for a completed update operation.

It is important to note that iterators (and the spliterators used for parallel streams) are acquired as a sort of snapshot, meaning that they will not throw a ConcurrentModificationException.

The table will be dynamically expanded when there are too many collisions, which can be a costly operation.

It is worthwhile (as with the HashMap) to provide an approximate sizing if you know it at the time of writing the code.

Java 5 also introduced the CopyOnWriteArrayList and CopyOnWriteArraySet, which in certain usage patterns can improve multithreaded performance.

With these, any mutation operation against the data structure causes a fresh copy of the backing array to be created. Any existing iterators can continue to traverse the old array, and once all references are lost the old copy of the array is eligible for garbage collection.

Again, this snapshot style of iteration ensures that there is no ConcurrentModificationException raised.

This tradeoff works well in systems where the copy-on-write data structure is accessed for reading many more times than mutating. If you are considering using this approach, make the change with a good set of tests to measure the performance improvement.

Latches and Barriers

Latches and barriers are useful techniques for controlling the execution of a set of threads. For example, a system may be written where worker threads:

-

Retrieve data from an API and parse it.

-

Write the results to a database.

-

Finally, compute results based on a SQL query.

If the system simply started all the threads running, there would be no guarantee on the ordering of events. The desired effect would be to allow all threads to complete task #1 and then task #2 before starting on task #3. One possibility would be to use a latch. Assuming we have five threads running, we could write code like the following:

packageoptjava.ch12;importjava.util.concurrent.CountDownLatch;importjava.util.concurrent.ExecutorService;importjava.util.concurrent.Executors;importjava.util.concurrent.TimeUnit;publicclassLatchExampleimplementsRunnable{privatefinalCountDownLatchlatch;publicLatchExample(CountDownLatchlatch){this.latch=latch;}@Overridepublicvoidrun(){// Call an APISystem.out.println(Thread.currentThread().getName()+" Done API Call");try{latch.countDown();latch.await();}catch(InterruptedExceptione){e.printStackTrace();}System.out.println(Thread.currentThread().getName()+" Continue processing");}publicstaticvoidmain(String[]args)throwsInterruptedException{CountDownLatchapiLatch=newCountDownLatch(5);ExecutorServicepool=Executors.newFixedThreadPool(5);for(inti=0;i<5;i++){pool.submit(newLatchExample(apiLatch));}System.out.println(Thread.currentThread().getName()+" about to await on main..");apiLatch.await();System.out.println(Thread.currentThread().getName()+" done awaiting on main..");pool.shutdown();try{pool.awaitTermination(5,TimeUnit.SECONDS);}catch(InterruptedExceptione){e.printStackTrace();}System.out.println("API Processing Complete");}}

In this example, the latch is set to have a count of 5, with each thread making a call to countdown() reducing the number by one.

Once the count reaches 0, the latch will open, and any threads held on the await() function will be released to continue their processing.

It is important to realize that this type of latch is single-use only.

This means that once the result is 0, the latch cannot be reused; there is no reset.

Note

Latches are extremely useful in examples such as cache population during startup and multithreaded testing.

In our example, we could have used two different latches: one for the API results to be finished and another for the database results to complete.

Another option is to use a CyclicBarrier, which can be reset.

However, figuring out which thread should control the reset is quite a difficult challenge and involves another type of synchronization.

One common best practice is to use one barrier/latch for each stage in the pipeline.

Executors and Task Abstraction

In practice, most Java programmers should not have to deal with low-level threading concerns.

Instead, we should be looking to use some of the java.util.concurrent features that support concurrent programming at a suitable level of abstraction.

For example, keeping threads busy using some of the java.util.concurrent libraries will enable better thread hot performance (i.e., keeping a thread running rather than blocked and in a waiting state).

The level of abstraction that offers few threading concerns can be described as a concurrent task—that is, a unit of code or work that we require to run concurrently within the current execution context. Considering units of work as tasks simplifies writing a concurrent program, as the developer does not have to consider the thread lifecycle for the actual threads executing the tasks.

Introducing Asynchronous Execution

One way of fulfilling the task abstraction in Java is by using the Callable interface to represent a task that returns a value.

The Callable<V> interface is a generic interface defining one function, call(), that returns a value of type V and throws an exception in the case that a result cannot be calculated.

On the surface Callable looks very similar to Runnable; however, Runnable does not return a result and does not throw an exception.

Note

If Runnable throws an uncaught unchecked exception, it propagates up the stack and by default the executing thread stops running.

Dealing with exceptions in the lifetime of a thread is a difficult programming problem and can result in Java programs continuing to run in strange states if not managed correctly.

It should also be noted that threads can be treated as OS-style processes, meaning they can be expensive to create on some operating systems.

Getting hold of any result from Runnable can also add extra complexity, particularly in terms of coordinating the execution return against another thread, for instance.

The Callable<V> type provides us with a way to deal with the task abstraction nicely, but how are these tasks actually executed?

An ExecutorService is an interface that defines a mechanism for executing tasks on a pool of managed threads.

The actual implementation of the ExecutorService defines how the threads in the pool should be managed and how many there should be.

An ExecutorService can take either Runnable or Callable via the submit() method and its overloads.

The helper class Executors has a series of new* factory methods that construct the service and backing thread pool according to the selected behavior.

These factory methods are the usual way to create new executor objects:

newFixedThreadPool(int nThreads)-

Constructs an

ExecutorServicewith a fixed-size thread pool, in which the threads will be reused to run multiple tasks. This avoids having to pay the cost of thread creation multiple times for each task. When all the threads are in use, new tasks are stored in a queue. newCachedThreadPool()-

Constructs an

ExecutorServicethat will create new threads as required and reuse threads where possible. Created threads are kept for 60 seconds, after which they will be removed from the cache. Using this thread pool can give better performance with small asynchronous tasks. newSingleThreadExecutor()-

Constructs an

ExecutorServicebacked by a single thread. Any newly submitted tasks are queued until the thread is available. This type of executor can be useful to control the number of tasks concurrently executed. newScheduledThreadPool(int corePoolSize)-

Has an additional series of methods that allow a task to be executed at a point in the future that take

Callableand a delay.

Once a task is submitted it will be processed asynchronously, and the submitting code can choose to block or poll for the result.

The submit() call to the ExecutorService returns a Future<V> that allows a blocking get() or a get() with a timeout, or a nonblocking call using isDone() in the usual manner.

Selecting an ExecutorService

Selecting the right ExecutorService allows good control of asynchronous processing and can yield significant performance benefits if you choose the right number of threads in the pool.

It is also possible to write a custom ExecutorService, but this is not often necessary.

One way in which the library helps is by providing a customization option: the ability to supply a ThreadFactory.

The ThreadFactory allows the author to write a custom thread creator that can set properties on threads such as name, daemon status, and thread priority.

The ExecutorService will sometimes need to be tuned empirically in the settings of the entire application.

Having a good idea of the hardware that the service will run on and other competing resources is a valuable part of the tuning picture.

One metric that is usually used is the number of cores versus the number of threads in the pool. Selecting a number of threads to run concurrently that is higher than the number of processors available can be problematic and cause contention. The operating system will be required to schedule the threads to run, and this causes a context switch to occur.

When contention hits a certain threshold, it can negate the performance benefits of moving to a concurrent way of processing. This is why a good performance model and being able to measure improvements (or losses) is imperative. Chapter 5 discusses performance testing techniques and antipatterns to avoid when undertaking this type of testing.

Fork/Join

Java offers several different approaches to concurrency that do not require developers to control and manage their own threads.

Java 7 introduced the Fork/Join framework, which provides a new API to work efficiently with multiple processors.

It is based on a new implementation of ExecutorService, called ForkJoinPool.

This class provides a pool of managed threads, which has two special features:

-

It can be used to efficiently process a subdivided task.

-

It implements a work-stealing algorithm.

The subdivided task support is introduced by the ForkJoinTask class.

This is a thread-like entity that is more lightweight than a standard Java thread.

The intended use case is that potentially large numbers of tasks and subtasks may be hosted by a small number of actual threads in a ForkJoinPool executor.

The key aspect of a ForkJoinTask is that it can subdivide itself into “smaller” tasks, until the task size is small enough to compute directly.

For this reason, the framework is suitable only for certain types of tasks, such as computation of pure functions or other “embarrassingly parallel” tasks.

Even then, it may be necessary to rewrite algorithms or code to take full advantage of this part of Fork/Join.

However, the work-stealing algorithm part of the Fork/Join framework can be used independently of the task subdivision. For example, if one thread has completed all the work allocated to it and another thread has a backlog, it will steal work from the queue of the busy thread. This rebalancing of jobs across multiple threads is quite a simple but clever idea, yielding considerable benefit. In Figure 12-5, we can see a representation of work stealing.

Figure 12-5. The work-stealing algorithm

ForkJoinPool has a static method, commonPool(), that returns a reference to the system-wide pool. This prevents developers from having to create their own pool and provides the opportunity for sharing.

The common pool is lazily initialized so will be created only if required.

The sizing of the pool is defined by Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors()—1.

However, this method does not always return the expected result.

Writing on the Java Specialists mailing list, Heinz Kabutz found a case where a 16-4-2 machine (16 sockets, each with 4 cores and 2 hyperthreads per core) returned the value 16. This seems very low; the naive intuition gained by testing on our laptops may have led us to expect the value to be 16 * 4 * 2 = 128. However, if we were to run Java 8 on this machine, it would configure the common Fork/Join pool to have a parallelism of only 15.

The VM doesn’t really have an opinion about what a processor is; it just asks the OS for a number. Similarly, the OS usually doesn’t care either, it asks the hardware. The hardware responds with a number, usually the number of “hardware threads.” The OS believes the hardware. The VM believes the OS.

Brian Goetz

Thankfully, there is a flag that allows the developer to programmatically set the desired parallelism:

-Djava.util.concurrent.ForkJoinPool.common.parallelism=128

As discussed in Chapter 5, though, be careful with magic flags. And as we will discuss with selecting the parallelStream option, nothing comes for free!

The work-stealing aspect of Fork/Join is becoming more utilized by library and framework developers, even without task subdivision.

For example, the Akka framework, which we will meet “Actor-Based Techniques”, uses a ForkJoinPool primarily for the benefits of work stealing.

The arrival of Java 8 also raised the usage level of Fork/Join significantly, as behind the scenes parallelStream() uses the common Fork/Join pool.

Modern Java Concurrency

Concurrency in Java was originally designed for an environment where long-running blocking tasks could be interleaved to allow other threads to execute—for instance, I/O and other similar slow operations. Nowadays, virtually every machine a developer writes code for will be a multiprocessor system, so making efficient use of the available CPU resources is very sensible.

However, when the notion of concurrency was built into Java it was not something the industry had a great deal of experience with. In fact, Java was the first industry-standard environment to build in threading support at language level. As a result, many of the painful lessons developers have learned about concurrency were first encountered in Java. In Java the approach has generally been not to deprecate features (especially core features), so the Thread API is still a part of Java and always will be.

This has led to a situation where in modern application development, threads are quite low-level in comparison to the abstraction level at which Java programmers are accustomed to writing code. For example, in Java we do not deal with manual memory management, so why do Java programmers have to deal with low-level threading creation and other lifecycle events?

Fortunately, modern Java offers an environment that enables significant performance to be gained from abstractions built into the language and standard library. This allows developers to have the advantages of concurrent programming with fewer low-level frustrations and less boilerplate.

Streams and Parallel Streams

By far the biggest change in Java 8 (arguably the biggest change ever) was the introduction of lambdas and streams. Used together, lambdas and streams provide a sort of “magic switch” to allow Java developers to access some of the benefits of a functional style of programming.

Leaving aside the rather complex question of just how functional Java 8 actually is as a language, we can say that Java now has a new paradigm of programming. This more functional style involves focusing on data rather than the imperative object-oriented approach that it has always had.

A stream in Java is an immutable sequence of data items that conveys elements from a data source.

A stream can be from any source (collection, I/O) of typed data.

We operate on streams using manipulating operations, such as map(), that accept lambda expressions or function objects to manipulate data.

This change from external iteration (traditional for loops) to internal iteration (streams) provides us with some nice opportunities to parallelize data and to lazily evaluate complicated expressions.

All collections now provide the stream() method from the Collection interface.

This is a default method that provides an implementation to create a stream from any collection, and behind the scenes a ReferencePipeline is created.

A second method, parallelStream(), can be used to work on the data items in parallel and recombine the results. Using parallelStream() involves separating the work using a Spliterator and executing the computation on the common Fork/Join pool.

This is a convenient technique to work on embarrassingly parallel problems, because stream items are intended to be immutable and so allow us to avoid the problem of mutating state when working in parallel.

The introduction of streams has yielded a more syntactically friendly way of working with Fork/Join than recoding using RecursiveAction.

Expressing problems in terms of the data is similar to task abstraction in that it helps the developer avoid having to consider low-level threading mechanics and data mutability concerns.

It can be tempting to always use parallelStream(), but there is a cost to using this approach.

As with any parallel computation, work has to be done to split up the task across multiple threads and then to recombine the results—a direct example of Amdahl’s Law.

On smaller collections serial computation can actually be much quicker.

You should always use caution and performance-test when using parallelStream().

Missing out on compute power could be disastrous, but the message of “measure, don’t guess” applies here.

In terms of using parallel streams to gain performance, the benefit needs to be direct and measurable, so don’t just blindly convert a sequential stream to parallel.

Lock-Free Techniques

Lock-free techniques start from the premise that blocking is bad for throughput and can degrade performance. The problem with blocking is that it yields to the operating system to show that there is an opportunity to context-switch the thread.

Consider an application running two threads, t1 and t2, on a two-core machine. A lock scenario could result in threads being context-switched out and back onto the other processor. In addition, the time taken to pause and wake can be significant, meaning that locking can be a lot slower than a technique that is lock-free.

One modern design pattern that highlights the potential performance gains of lock-free concurrency is the Disruptor pattern, originally introduced by the London Multi Asset Exchange (LMAX).

When benchmarked against an ArrayBlockingQueue, the Disruptor outperformed it by orders of magnitude.

The GitHub project page shows some of these comparisons. One sample from the web page has the performance numbers listed in Table 12-1.

| Array blocking queue | Disruptor | |

|---|---|---|

Unicast: 1P–1C |

5,339,256 |

25,998,336 |

Pipeline: 1P–3C |

2,128,918 |

16,806,157 |

Sequencer: 3P–1C |

5,539,531 |

13,403,268 |

Multicast: 1P–3C |

1,077,384 |

9,377,871 |

These astonishing results are achieved with a spinlock.

The synchronization is effectively manually controlled between the two threads by way of a volatile variable (to ensure visibility across threads):

privatevolatileintproceedValue;//...while(i!=proceedValue){// busy loop}

Keeping the CPU core spinning means that once data is received, it is immediately ready to operate on that core with no context switching required.

Of course, lock-free techniques also come at a cost. Occupying a CPU core is expensive in terms of utilization and power consumption: the computer is going to be busier doing nothing, but busier also implies hotter, which means more power will be required to cool down the core that’s processing nothing.

Running applications that require this kind of throughput often requires the programmer to have a good understanding of the low-level implications of the software. This should be supplemented by a mechanical sympathy for how the code will interact with the hardware. It is not a coincidence that the term mechanical sympathy was coined by Martin Thompson, one of the originators of the Disruptor pattern.

The name “mechanical sympathy” comes from the great racing driver Jackie Stewart, who was a three times world Formula 1 champion. He believed the best drivers had enough understanding of how a machine worked so they could work in harmony with it.

Martin Thompson

Actor-Based Techniques

In recent years, several different approaches to representing tasks that are somehow smaller than a thread have emerged.

We have already met this idea in the ForkJoinTask class.

Another popular approach is the actor paradigm.

Actors are small, self-contained processing units that contain their own state, have their own behavior, and include a mailbox system to communicate with other actors. Actors manage the problem of state by not sharing any mutable state and only communicating with each other via immutable messages. The communication between actors is asynchronous, and actors are reactive to the receipt of a message to perform their specified task.

By forming a network in which they each have specific tasks within a parallel system, actors take the view of abstracting away from the underlying concurrency model completely.

Actors can live within the same process, but are not required to. This opens up a nice advantage that actor systems can be multiprocess and even potentially span multiple machines. Multiple machines and clustering enables actor-based systems to perform effectively when a degree of fault tolerance is required. To ensure that actors work successfully in a collaborative environment, they typically have a fail-fast strategy.

For JVM-based languages, Akka is a popular framework for developing actor-based systems. It is written in Scala but also has a Java API, making it usable for Java and other JVM languages as well.

The motivation for Akka and an actor-based system is based on several problems that make concurrent programming difficult. The Akka documentation highlights three core motivations for considering the use of Akka over traditional locking schemes:

-

Encapsulating mutable state within the domain model can be tricky, especially if a reference to the objects internals is allowed to escape without control.

-

Protecting state with locks can cause significant reduction in throughput.

-

Locks can lead to deadlock and other types of liveness problems.

Additional problems highlighted include the difficulty of getting shared memory usage correct and the performance problems this can introduce by forcing cache lines to be shared across multiple CPUs.

The final motivation discussed is related to failures in traditional threading models and call stacks. In the low-level threading API, there is no standard way to handle thread failure or recovery. Akka standardizes this, and provides a well-defined recovery scheme for the developer.

Overall, the actor model can be a useful addition to the concurrent developer’s toolbox. However, it is not a general-purpose replacement for all other techniques. If the use case fits within the actor style (asynchronous passing of immutable messages, no shared mutable state, and time-bounded execution of every message processor), then it can be an excellent quick win. If, however, the system design includes request-response synchronous processing, shared mutable state, or unbounded execution, then careful developers may choose to use another abstraction for building their systems.

Summary

This chapter only scratches the surface of topics that you should consider before aiming to improve application performance using multithreading. When converting a single-threaded application to a concurrent design:

-

Ensure that the performance of straight-line processing can be measured accurately.

-

Apply a change and test that the performance is actually improved.

-

Ensure that the performance tests are easy to rerun, especially if the size of data processed by the system is likely to change.

Avoid the temptation to:

-

Use parallel streams everywhere.

-

Create complicated data structures with manual locking.

-

Reinvent structures already provided in

java.util.concurrent.

Aim to:

-

Improve thread hot performance using concurrent collections.

-

Use access designs that take advantage of the underlying data structures.

-

Reduce locking across the application.

-

Provide appropriate task/asynchronous abstractions to prevent having to deal with threads manually.

Taking a step back, concurrency is key to the future of high-performance code. However:

-

Shared mutable state is hard.

-

Locks can be challenging to use correctly.

-

Both synchronized and asynchronous state sharing models are needed.

-

The JMM is a low-level, flexible model.

-

The thread abstraction is very low-level.

The trend in modern concurrency is to move to a higher-level concurrency model and away from threads, which are increasingly looking like the “assembly language of concurrency.” Recent versions of Java have increased the amount of higher-level classes and libraries available to the programmer. On the whole, the industry seems to be moving to a model of concurrency where far more of the responsibility for safe concurrent abstractions is managed by the runtime and libraries.