Chapter 11. Java Language Performance Techniques

So far, we have explored the mechanisms by which the JVM takes the code written by a developer, converts it into bytecode, and optimizes it to high-performance compiled code.

It would be wonderful if every Java application were composed of top-quality, pristine code that was architected with performance in mind. The reality, however, is often quite different. Despite this, in many cases the JVM can take suboptimal code and make it work reasonably well—a testament to the power and robustness of the environment.

Even applications that have an insane code base and are difficult to maintain can often somehow be made to work adequately in production. Of course, no one wants to maintain or modify such applications. So what is left for the developer to consider when this type of code base needs to be tuned for performance?

After external application factors, such as network connectivity, I/O, and databases, one of the biggest potential bottlenecks for performance is the design of the code. Design is an incredibly difficult part to get right, and no design is ever perfect.

Note

Optimizing Java is complicated, and in Chapter 13, we’ll look at how profiling tools can assist in finding code that is not performing as it should.

In spite of this, there are some basic aspects of code that the performance-conscious developer should keep in mind. For example, how data is stored in the application is incredibly important. And, as business requirements change, the way data is stored may also need to evolve. In order to understand the options available for data storage, it is important to familiarize yourself with the data structures available in the Java Collections API and their implementation details.

Selecting a data structure without knowing how it will be updated and queried is dangerous. Though some developers will reach straight for their favorite classes and use them without thinking about it, a conscientious developer considers how the data will be queried and which algorithms will most effectively query the data. There are many algorithms and operations that java.lang.Collections supplies in the form of static methods.

Tip

Before writing an implementation of a common algorithm (e.g., a manually written bubble sort) for use in production code, check to see if there’s something in java.lang.Collections that can be utilized.

Understanding domain objects and their lifetime within the system can have a significant impact on performance. There are several heuristics to consider, and the way that domain objects are used within an application can impact garbage collection and add overhead, which the JVM has to then manage (often unnecessarily) at runtime.

In this chapter, we will explore each of these concerns, starting with what the performance-conscious developer should know about collections.

Optimizing Collections

Most programming language libraries provide at least two general types of container:

-

Sequential containers store objects at a particular position, denoted by a numerical index.

-

Associative containers use the object itself to determine where the object should be stored inside the collection.

For certain container methods to work correctly, the objects being stored must have a notion of comparability and of equivalence. In the core Java Collections API this is usually expressed by the statement that the objects must implement hashCode() and equals(), in accordance with the contract popularized by Josh Bloch in his book Effective Java (Pearson).

As we saw in “Introducing the HotSpot Runtime”, fields of reference type are stored as references in the heap. Consequently, although we talk loosely about objects being stored sequentially, it is not the object itself that is stored in the container, but rather a reference to it. This means that you will not typically get the same performance as from using a C/C++-style array or vector.

This is an example of how Java’s managed memory subsystem requires you to give up low-level control of memory in exchange for automatic garbage collection. The usual example of the low-level control being relinquished is manual control of allocation and release, but here we see that control of low-level memory layout is also given up.

Tip

Another way to think about this issue is that Java has, as yet, no way to lay out the equivalent of an array of C structs.

Gil Tene (CTO of Azul Systems) often labels this limitation as one of the last major performance barriers between Java and C. The ObjectLayout website has more information on how layout could be standardized, and the code there will work and compile on Java 7 and above. Its intention is that an optimized JVM would be able to take these types and lay out the structures correctly with the semantics described without breaking compatibility with other JVMs.

In Chapter 15 we will discuss the future of the Java environment and describe the effort to bring value types to the platform. This will go considerably further than is possible with the object layout code.

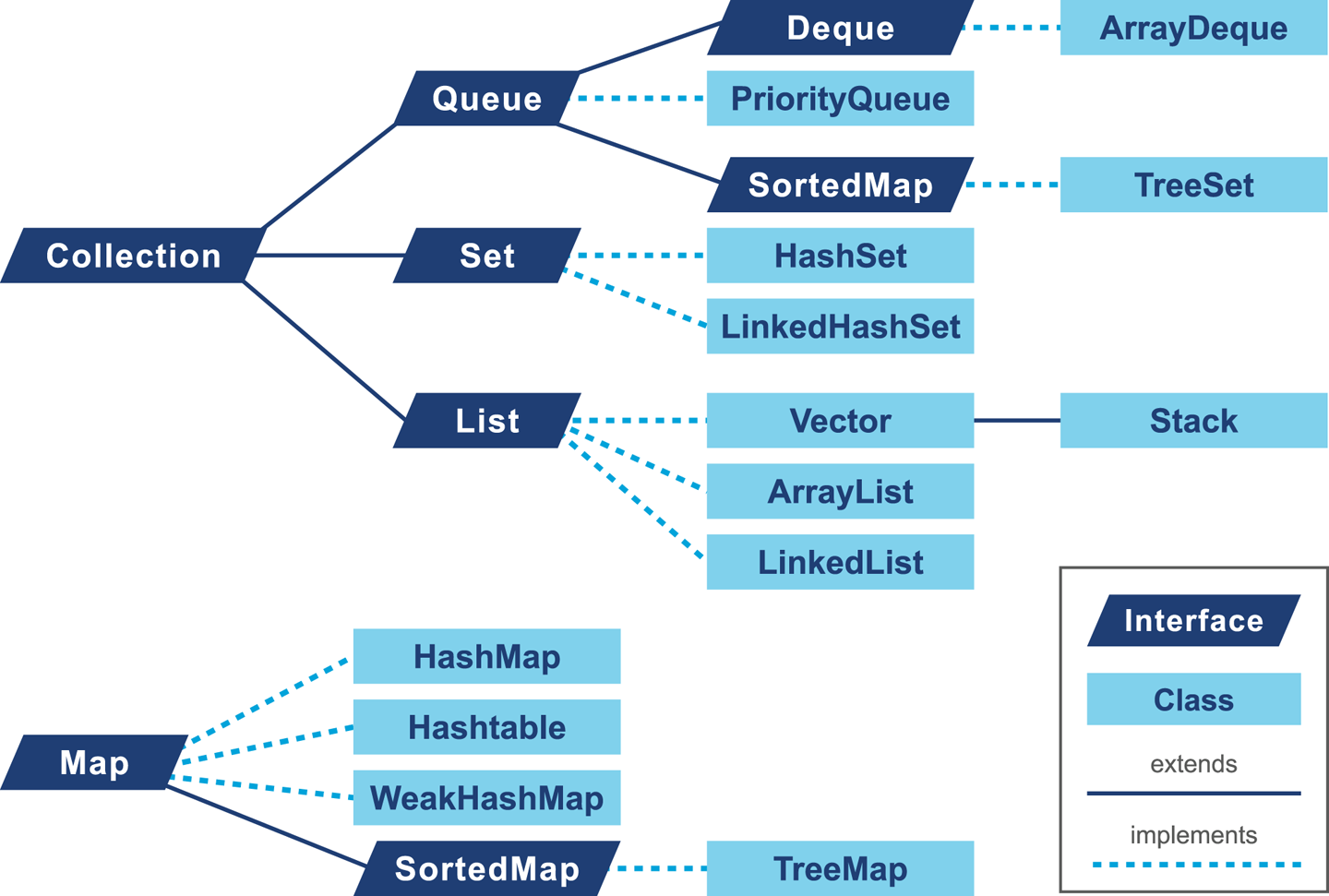

The Collections API defines a set of interfaces specifying the operations a container of that type must conform to. Figure 11-1 shows the basic type layout.

Figure 11-1. Class hierarchy from Java Collections API

In addition to the interfaces, there are several implementations of the collections available inside the JDK. Selecting the right implementation based on the design is the first part of the problem, but we also need to recognize that our choice may have an impact on the overall performance of the application.

Optimization Considerations for Lists

In core Java there are basically two options for representing a list, ArrayList and LinkedList.

Warning

Although Java also has Stack and Vector classes, the former supplies additional semantics that are usually unwarranted and the latter is heavily deprecated. Your code should not use Vector, and you should refactor to remove any usage of it that you find.

Let’s talk about each in turn, starting with the array-backed list.

ArrayList

ArrayList is backed by an array that has a fixed size. Entries can be added to the array up to the maximum size of the backing array. When the backing array is full, the class will allocate a new, larger array and copy the old values. The performance-conscious programmer must therefore weigh the cost of the resize operation versus the flexibility of not having to know ahead of time how big the lists will become. An ArrayList is initially backed by an empty array. On the first addition to the ArrayList a backing array of capacity 10 is allocated. We can prevent this resizing behavior by passing our preferred initial capacity value to the constructor. We can also use the ensureCapacity() to increase the capacity of the ArrayList to avoid resizing.

Tip

It is wise to set a capacity whenever possible, as there is a performance cost to the resizing operation.

The following is a microbenchmark in JMH (as covered in “Introduction to JMH”) showing this effect:

@BenchmarkpublicList<String>properlySizedArrayList(){List<String>list=newArrayList<>(1_000_000);for(inti=0;i<1_000_000;i++){list.add(item);}returnlist;}@BenchmarkpublicList<String>resizingArrayList(){List<String>list=newArrayList<>();for(inti=0;i<1_000_000;i++){list.add(item);}returnlist;}

Note

The microbenchmarks in this section are designed to be illustrative, rather than authoritative. If your applications are genuinely sensitive to the performance implications of these types of operations, you should explore alternatives to the standard collections.

This results in the following output:

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units ResizingList.properlySizedArrayList thrpt 10 287.388 ± 7.135 ops/s ResizingList.resizingArrayList thrpt 10 189.510 ± 4.530 ops/s

The properlySizedArrayList test is able to perform around 100 extra operations per second when it comes to insertion, as even though the cost of reallocation is amortized there is still an overall cost. Choosing a correctly sized ArrayList is always preferable when possible.

LinkedList

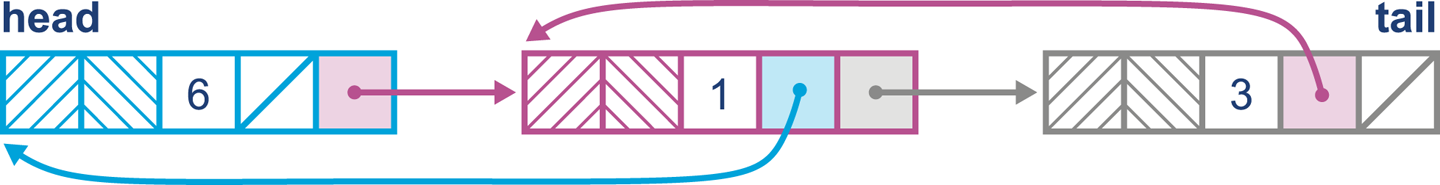

The LinkedList has a more dynamic growth scheme; it is implemented as a doubly linked list and this means (among other things) that appending to the list will always be O(1).

Each time an item is added to the list, a new node is created and referenced from the previous item. An example can be seen in Figure 11-2.

Figure 11-2. A LinkedList

ArrayList versus LinkedList

The real decision of whether to use an ArrayList or a LinkedList (or another nonstandard implementation of List) depends on the pattern of access and modification of the data. Inserting at the end of a list in both ArrayList and LinkedList is a constant-time operation (after the resize operations are amortized, in the case of ArrayList).

However, adding at an index in ArrayList requires all other elements to be shifted by one position to the right. LinkedList, on the other hand, has to traverse node references to find the position in the list where the insert is required, but the insert itself simply involves creating a new node and setting two references, one pointing to the node at the beginning of the list (the first reference) and the other to the next node in the list (the next reference). This benchmark shows the difference in performance of inserting at the beginning of each type of list:

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units InsertBegin.beginArrayList thrpt 10 3.402 ± 0.239 ops/ms InsertBegin.beginLinkedList thrpt 10 559.570 ± 68.629 ops/ms

List removal has a similar behavior; it is cheaper to remove from a LinkedList, at most two references need to change. In an ArrayList, all items to the right of the deletion need to shift one place to the left.

If the list is mainly accessed randomly ArrayList is the best choice, as any element can be accessed in O(1) time, whereas LinkedList requires navigation from the beginning to the index count. The costs of accessing the different types of list by a specific index are shown in the following simple benchmark:

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units AccessingList.accessArrayList thrpt 10 269568.627 ± 12972.927 ops/ms AccessingList.accessLinkedList thrpt 10 0.863 ± 0.030 ops/ms

In general it is recommended to prefer ArrayList unless you require the specific behavior of LinkedList, especially if you are using an algorithm that requires random access.

If possible, size the ArrayList correctly ahead of time to avoid the charge of resizing. Collections in modern Java take the view that the developer should incur the synchronization costs for all accesses and should either use the concurrent collections or manually manage synchronization when necessary.

In the Collections helper class there is a method called synchronizedList(), which is effectively a decorator that wraps all of the List method invocations in a synchronized block.

In Chapter 12 we will discuss in more detail how to use java.util.concurrent for structures that can be used more effectively when you are writing multithreaded applications.

Optimization Considerations for Maps

A mapping in general describes a relationship between a key and an associated value (hence the alternative term associative array). In Java this follows the interface java.util.Map<K,V>. Both key and value must be of reference type, of course.

HashMap

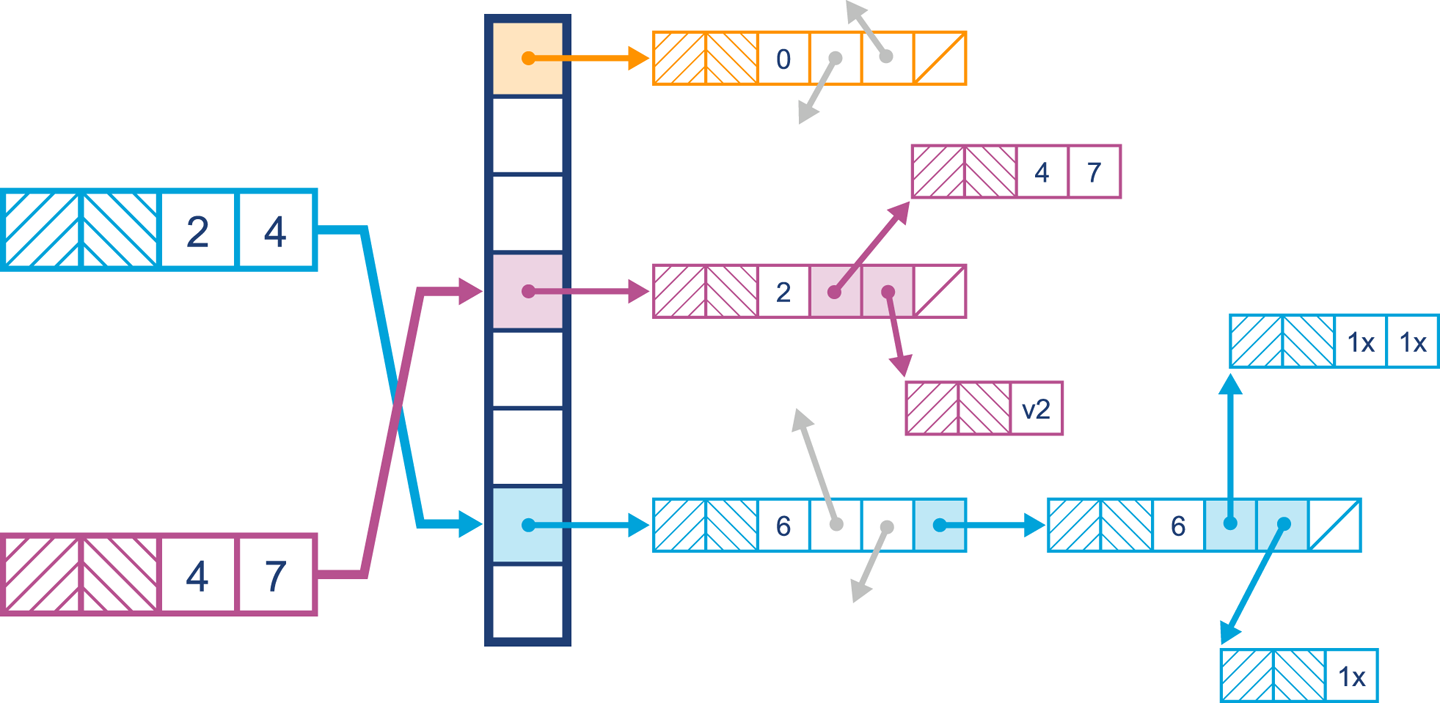

In many ways, Java’s HashMap can be seen as a classic introductory computer science hash table, but with a few additional embellishments to make it suitable for modern environments.

A cut-down version of the HashMap (eliding generics and a couple of key features, which we will return to) has some key methods that look like this:

publicObjectget(Objectkey){// SIMPLIFY: Null keys are not supportedif(key==null)returnnull;inthash=key.hashCode();inti=indexFor(hash,table.length);for(Entrye=table[i];e!=null;e=e.next){Objectk;if(e.hash==hash&&((k=e.key)==key||key.equals(k)))returne.value;}returnnull;}privateintindexFor(inth,intlength){returnh&(length-1);}// This is a linked list nodestaticclassNodeimplementsMap.Entry{finalinthash;finalObjectkey;Objectvalue;Nodenext;Node(inth,Objectk,Objectv,Entryn){hash=h;key=k;value=v;next=n;}}

In this case, the HashMap.Node class is restricted to package access in java.util; that is, it is a classic use case for a static class.

The layout of the HashMap is shown in Figure 11-3.

Figure 11-3. A simple HashMap

Initially the bucket entries will be stored in a list. When it comes to finding a value, the hash of the key is calculated and then the equals() method is used to find the key in the list. Because of the mechanics of hashing the key and using equality to find it in the list, duplicate keys are not permitted in a HashMap. Inserting the same key simply replaces the key currently stored in the HashMap.

In modern Java versions, one of the improvements is that indexFor() has been replaced by code that uses the hashCode() of the key object and applies a mask to spread higher bits in the hash downward.

This has been designed as a tradeoff to ensure that the HashMap takes into account higher bits when calculating which bucket a key hashes to. If this was not done, the higher bits might not be used in computing index calculations. This is problematic for a number of reasons, not least of which is that it violates Shannon’s Strict Avalanche Criteria—the idea that even arbitrarily small changes in input data should produce potentially very large changes in the output of the hash function.

Two important variables impact the performance of a HashMap: initialCapacity and loadFactor, both of which can be set via parameters passed to the constructor. The capacity of a HashMap represents the current number of buckets that have been created, which defaults to 16. The loadFactor represents how full the hash table is allowed to get before the capacity is automatically increased. Increasing the capacity and recalculating hashes is a procedure known as rehashing, which doubles the number of buckets available and redistributes the data stored.

Note

Setting the initialCapacity of a HashMap follows the same rules as for ArrayList: if you know up front roughly how much information will be stored, you should set it.

An accurate initialCapacity will avoid the need to automatically rehash as the table grows. It is also possible to tweak loadFactor, but 0.75 (the default) provides a good balance between space and time of access. A loadFactor of higher than 0.75 will reduce the rehashing requirement, but access will become slower as buckets will generally become fuller. Setting the initialCapacity to the maximum number of elements divided by the loadFactor will prevent a rehash operation from occurring.

The HashMap provides constant-time support for get() and put() operations, but iteration can be costly. As mentioned in the JavaDoc, setting the initialCapacity and loadFactor high will severely impact the iteration performance.

Another factor that impacts performance is a process known as treeifying. This relatively recent innovation is an internal implementation detail of HashMap, but is potentially useful for performance engineers.

Consider the case where a bucket becomes highly populated. If the bucket elements are implemented as a LinkedList, traversal to find an element becomes on average more expensive as the list grows.

To counteract this linear effect, modern implementations of HashMap have a new mechanism. Once a bucket reaches a TREEIFY_THRESHOLD, it is converted to a bin of TreeNodes (and behaves similar to a TreeMap).

Why not do this from the beginning? TreeNodes are about double the size of a list node, and therefore a space cost is paid. A well-distributed hashing function will rarely cause buckets to be converted to TreeNodes. Should this occur in your application, it is time to consider revisiting the hash function, initialCapacity, and loadFactor settings for the HashMap.

As with everything else in performance, practical techniques are driven by tradeoffs and pragmatism, and you should adopt a similarly hardheaded and data-driven approach to the analysis of your own code.

LinkedHashMap

LinkedHashMap is a subclass of HashMap that maintains the insertion order of elements by using a doubly linked list running through the elements.

By default, using LinkedHashMap maintains the insertion order, but it is also possible to switch the mode to access order. LinkedHashMap is often used where ordering matters to the consumer, and it is not as costly as the usage of a TreeMap.

In most cases, neither the insertion order nor the access order will matter to the users of a Map, so there should be relatively few occasions in which LinkedHashMap is the correct choice of collection.

TreeMap

The TreeMap is, essentially, a red-black tree implementation. This type of tree is basically a binary tree structure with additional metadata (node coloring) that attempts to prevent trees from becoming overly unbalanced.

Note

For the nodes of the tree (TreeNodes) to be considered ordered it is necessary that keys use a comparator that is consistent with the equals() method.

The TreeMap is incredibly useful when a range of keys is required, allowing quick access to a submap. The TreeMap can also be used to partition the data from the beginning up to a point, or from a point to the end.

The TreeMap provides log(n) performance for the get(), put(), containsKey(), and remove() operations.

In practice, most of the time HashMap fulfills the Map requirement, but consider one example: the case where it is useful to process portions of a Map using streams or lambdas. Under these circumstances, using an implementation that understands partitioning of data—for example, TreeMap—may make more sense.

Lack of MultiMap

Java does not provide an implementation for MultiMap (a map that allows multiple values to be associated with a single key). The reason given in the documentation is that this is not often required and can be implemented in most cases as Map<K, List<V>>. Several open source implementations exist that provide a MultiMap implementation for Java.

Optimization Considerations for Sets

Java contains three types of sets, all of which have very similar performance considerations to Map.

In fact, if we start by taking a closer look at a version of HashSet (cut down for brevity), it is clear that it is implemented in terms of a HashMap (or LinkedHashMap in the case of LinkedHashSet):

publicclassHashSet<E>extendsAbstractSet<E>implementsSet<E>,Serializable{privatetransientHashMap<E,Object>map;// Dummy value to associate with an Object in the backing MapprivatestaticfinalObjectPRESENT=newObject();publicHashSet(){map=newHashMap<>();}HashSet(intinitialCapacity,floatloadFactor,booleandummy){map=newLinkedHashMap<>(initialCapacity,loadFactor);}publicbooleanadd(Ee){returnmap.put(e,PRESENT)==null;}}

The behavior of a Set is to not allow duplicate values, which is exactly the same as a key element in a Map. In the add() method, the HashSet simply inserts the element E as a key in the HashMap and uses a dummy object, PRESENT, as the value. There is minimal overhead to this, as the PRESENT object will be created once and referenced. HashSet has a second protected constructor that allows a LinkedHashMap; this can be used to mimic the same behavior while keeping track of the insert order. HashSet has O(1) insertion, removal, and contains operation time; it does not maintain an ordering of elements (unless used as a LinkedHashSet), and iteration cost depends on the initialCapacity and loadFactor.

A TreeSet is implemented in a similar way, leveraging the existing TreeMap previously discussed. Using a TreeSet will preserve the natural ordering of keys defined by the Comparator, making range-based and iteration operations far more suited to a TreeSet. A TreeSet guarantees log(n) time cost for insertion, removal, and contains operations and maintains the ordering of elements. Iteration and retrieval of subsets is efficient, and any range-based or ordering considerations would be better approached using TreeSet.

Domain Objects

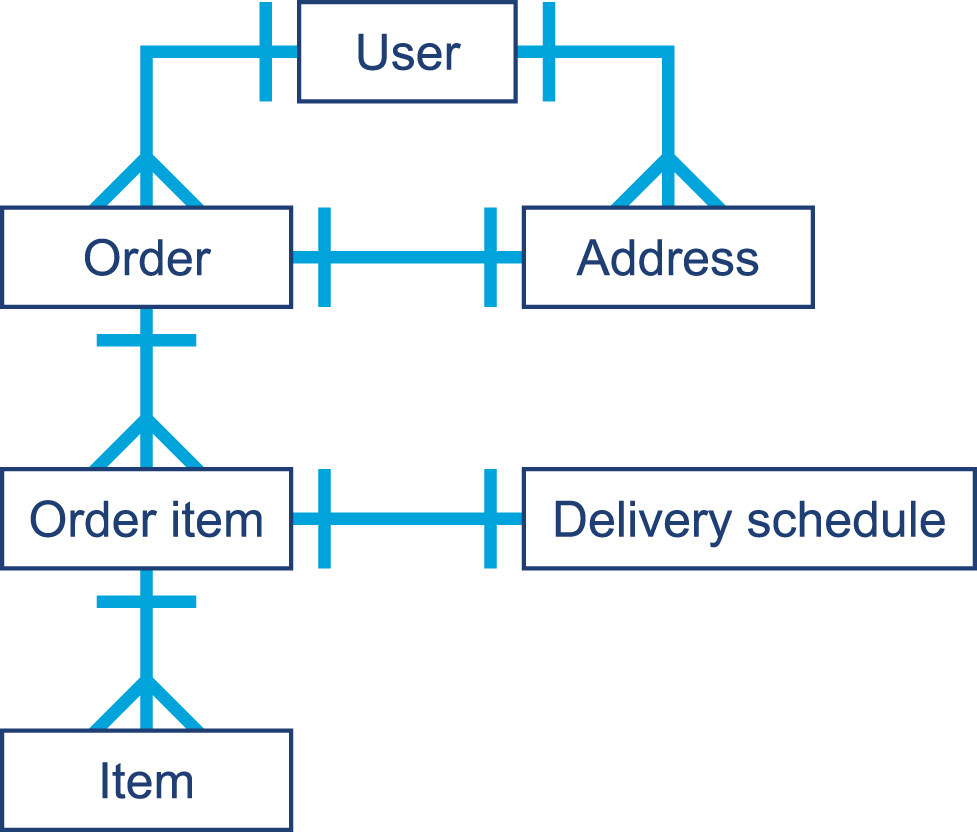

Domain objects are the code that expresses the business concepts that matter to your applications.

Examples might be an Order, an OrderItem, and a DeliverySchedule for an ecommerce site.

They will typically have relationships between the types (so an Order has multiple OrderItem instances associated with it). For example:

publicclassOrder{privatefinallongid;privatefinalList<OrderItem>items=newArrayList<>();privateDeliveryScheduleschedule;publicOrder(longid){this.id=id;}publicDeliverySchedulegetSchedule(){returnschedule;}publicvoidsetSchedule(DeliveryScheduleschedule){this.schedule=schedule;}publicList<OrderItem>getItems(){returnitems;}publiclonggetId(){returnid;}}publicclassOrderItem{privatefinallongid;privatefinalStringdescription;privatefinaldoubleprice;publicOrderItem(longid,Stringdescription,doubleprice){this.id=id;this.description=description;this.price=price;}@OverridepublicStringtoString(){return"OrderItem{"+"id="+id+", description="+description+", price="+price+'}';}}publicfinalclassDeliverySchedule{privatefinalLocalDatedeliveryDate;privatefinalStringaddress;privatefinaldoubledeliveryCost;privateDeliverySchedule(LocalDatedeliveryDate,Stringaddress,doubledeliveryCost){this.deliveryDate=deliveryDate;this.address=address;this.deliveryCost=deliveryCost;}publicstaticDeliveryScheduleof(LocalDatedeliveryDate,Stringaddress,doubledeliveryCost){returnnewDeliverySchedule(deliveryDate,address,deliveryCost);}@OverridepublicStringtoString(){return"DeliverySchedule{"+"deliveryDate="+deliveryDate+", address="+address+", deliveryCost="+deliveryCost+'}';}}

There will be ownership relationships between the domain types, as we can see in Figure 11-4.

Ultimately, however, the vast majority of the data items at the leaves of the domain object graph will be simple data types such as strings, primitives, and LocalDateTime objects.

Figure 11-4. Domain objects graph

In “Introducing Mark and Sweep”, we encountered the jmap -histo command. This provides a quick insight into the state of the Java heap, and equivalent functionality is available through GUI tools such as VisualVM. It is worth learning to use one of these very simple tools, as they can help diagnose a memory leak of domain objects under some (limited, but fairly common) circumstances.

Tip

The domain objects of an application have a somewhat unique status. As they are the representations of the first-order business concerns of the application, they are highly visible when you are looking for bugs such as memory leaks.

To see why, we need to consider a couple of basic facts about the Java heap:

-

The most commonly allocated data structures include strings, char arrays, byte arrays, and instances of Java collection types.

-

Data that corresponds to a leak will show up as an anomalously large dataset in

jmap.

That is, we expect the top entries by both memory volume and number of instances to be commonly occurring data structures from the core JDK. If application-specific domain objects appear in the top 30 or so entries generated by jmap, then this is a possible, but not conclusive, sign of a memory leak.

Another common behavior for leaking domain objects is the “all generations” effect. This effect occurs because objects of a specific type are not being collected when they should be. This means that they will eventually live long enough to become Tenured, and will show up with all possible values for the generational count after they survive enough collections.

If we plot a histogram of bytes per generational count (by data type), then we will see potentially leaking domain objects show up across all generations. This could be because they are being kept alive artificially beyond their natural lifetime.

One quick win is to look at the size of the dataset that corresponds to domain objects and see if this is reasonable and within the expected bounds for how many domain objects there should be in the working set.

At the other end of the spectrum, short-lived domain objects can be the cause of another form of the floating garbage problem that we have already met. Recall the SATB constraint for concurrent collectors—the idea that any objects, no matter how short-lived, are considered to be alive if they were allocated after a marking cycle started.

Warning

One occasionally observed feature of leaking domain objects is that they can show up as the culprit for high GC mark times. The root cause of this is that a single long-lived object is keeping alive an entire long chain of objects.

Domain objects can provide a useful “canary in the coal mine” for many applications; because they are the most obvious and natural representations of the business concerns, they seem to be more susceptible to leaks. Performance-conscious developers should ensure that they remain aware of their domain and the size of the relevant working sets.

Avoid Finalization

Java’s finalize() mechanism is an attempt to provide automatic resource management, in a similar way to the Resource Acquisition Is Initialization (RAII) pattern from C++. In that pattern, a destructor method (known as finalize() in Java) is provided to enable automatic cleanup and release of resources when an object is destroyed.

The basic use case is thus fairly simple. When an object is created, it takes ownership of some resource, and the object’s ownership of that resource persists for the lifetime of the object. Then, when the object dies, the ownership of the resource is automatically relinquished.

The standard example for this approach is the observation that when the programmer opens a file handle, it is all too easy to forget to call the close() function when it is no longer required.

Let’s look at a quick and simple C++ example that shows how to put an RAII wrapper around C-style file I/O:

classfile_error{};classfile{public:file(constchar*filename):_h_file(std::fopen(filename,"w+")){if(_h_file==NULL){throwfile_error();}}// Destructor~file(){std::fclose(_h_file);}voidwrite(constchar*str){if(std::fputs(str,_h_file)==EOF){throwfile_error();}}voidwrite(constchar*buffer,std::size_tnumc){if(numc!=0&&std::fwrite(buffer,numc,1,_h_file)==0){throwfile_error();}}private:std::FILE*_h_file;};

This promotes good design, especially when the only reason for a type to exist is to act as a “holder” of a resource such as a file or network socket. In that case, strongly tying the resource ownership to the object lifetime makes sense. Getting rid of the object’s resources automatically then becomes the responsibility of the platform, not the programmer.

War Story: Forgetting to Clean Up

Like many software war stories, this tale starts with production code that had been working fine for years. It was a service that connected via TCP to another service to establish permissions and entitlements information. The entitlements service was relatively stable and had good load balancing, usually responding instantly to requests. A new TCP connection was opened on each request—far from ideal in design.

One weekend a change happened that caused the entitlements system to be slightly slower in the response time. This caused the TCP connection to occasionally time out, a code path never previously seen in production. A TimeOutException was thrown and caught, nothing was logged, and there was no finally block—the close() function had previously been called from the success path.

Sadly, the problem did not end there. The close() function not being called meant that the TCP connection was left open. Eventually the production machine the application was running on ran out of file handles, which impacted other processes tenanted on that box. The resolution was to rewrite the code to first of all close the TCP connection and immediately patch, and second to pool the connection and not open a new connection for each resource.

Forgetting to call close() is an easy mistake to make, especially when using proprietary libraries.

Why Not Use Finalization to Solve the Problem?

Java initially offered the finalize() method, which lives on Object; by default, it is a no-op (and should usually remain that way). It is, however, possible to override finalize() and provide some behavior. The JavaDoc describes this as follows:

Called by the garbage collector on an object when garbage collection determines that there are no more references to the object. A subclass overrides the

finalize()method to dispose of system resources or to perform other cleanup.

The way that this is implemented is to use the JVM’s garbage collector as the subsystem that can definitively say that the object has died.

If a finalize() method is provided on a type, then all objects of that type receive special treatment.

An object that overrides finalize() is treated specially by the garbage collector.

The JVM implements this by registering individual finalizable objects on a successful return from the constructor body of java.lang.Object (which must be called at some point on the creation path of any object).

One detail of HotSpot that we need to be aware of at this point is that the VM has some special implementation-specific bytecodes in addition to the standard Java instructions. These specialist bytecodes are used to rewrite the standard ones in order to cope with certain special circumstances.

A complete list of the bytecode definitions, both standard Java and HotSpot special-case, can be found in hotspot/share/interpreter/bytecodes.cpp.

For our purposes, we care about the special-case return_register_finalizer bytecode.

This is needed because it is possible for, say, JVMTI to rewrite the bytecode for Object.<init>().

To precisely obey the standard, it is necessary to identify the point at which Object.<init>() completes (without rewriting), and the special-case bytecode is used to mark this point.

The code for actually registering the object as needing finalization can be seen in the HotSpot interpreter.

The file src/hotspot/cpu/x86/c1_Runtime.cpp contains the core of the x86-specific port of the HotSpot interpreter.

This has to be processor-specific because HotSpot makes heavy use of low-level assembly/machine code. The case register_finalizer_id contains the registration code.

Once the object has been registered as needing finalization, instead of being immediately reclaimed during the garbage collection cycle, the object follows this extended lifecycle:

-

Finalizable objects are moved to a queue.

-

After application threads restart, separate finalization threads drain the queue and run the

finalize()method on each object. -

Once the

finalize()method terminates, the object will be ready for actual collection in the next cycle.

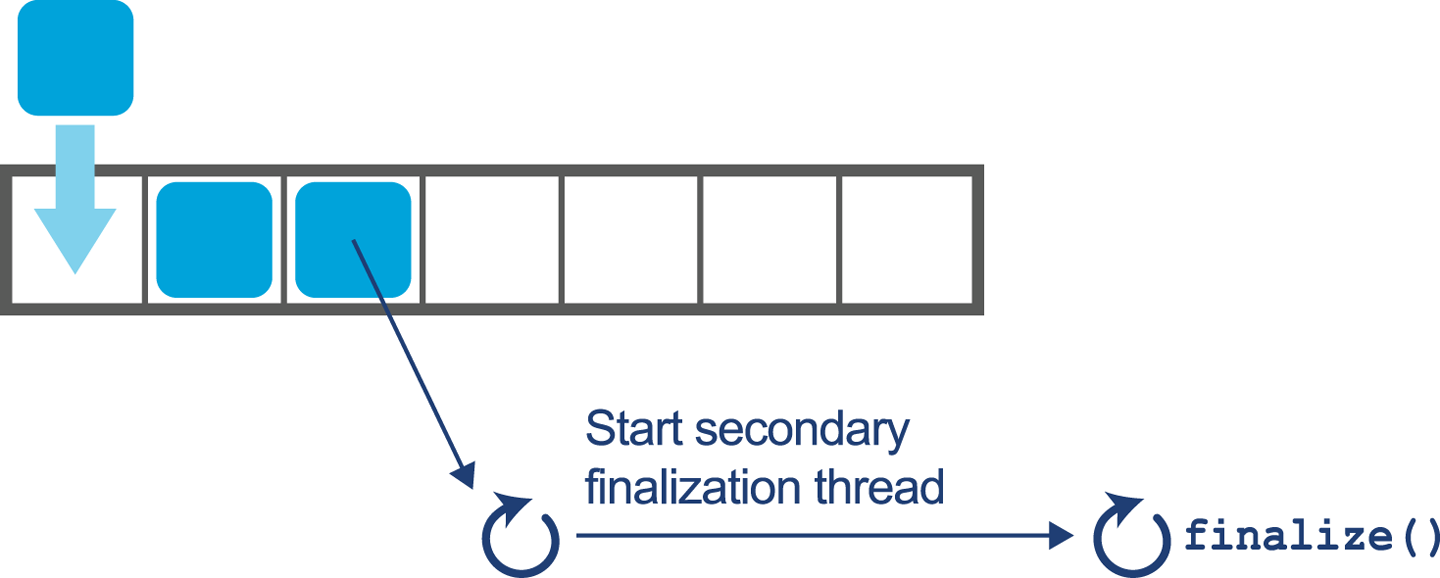

Overall, this means that all objects to be finalized must first be recognized as unreachable via a GC mark, then finalized, and then GC must run again in order for the data to be collected. This means that finalizable objects persist for one extra GC cycle at least. In the case of objects that have become Tenured, this can be a significant amount of time. The finalization queue processing can be seen in Figure 11-5.

Figure 11-5. Draining the finalization queue

There are other problems with finalize(); for example, what would happen if the method throws an exception while it is being executed by a finalization thread? There is no context inside the user’s application code at this point, so the exception is simply ignored. There is no way for the developer to know about or recover from a fault caused during finalization.

It is also possible that finalization could contain a blocking operation and therefore require the JVM to spawn a thread to run the finalize() method, with the inherent overhead of creating and running the new thread. Once again, the thread creation and management is outside of the developer’s control but is necessary to avoid locking up the entire JVM subsystem.

The majority of the implementation for finalization actually takes place in Java.

The JVM has separate threads to perform finalization that run at the same time as application threads for the majority of the required work.

The core functionality is contained in the package-private class java.lang.ref.Finalizer, which should be fairly simple to read.

The class also provides some insight into how certain classes are granted additional privileges by the runtime. For example, it contains code like this:

/* Invoked by VM */staticvoidregister(Objectfinalizee){newFinalizer(finalizee);}

Of course, in regular application code this would be nonsensical, as it creates an unused object. Unless the constructor has side effects (usually considered a bad design decision in Java), this would do nothing. In this case, the intent is to “hook” a new finalizable object.

The implementation of finalization also relies heavily on the FinalReference class. This is a subclass of java.lang.ref.Reference, which is a class that the runtime is aware of as a special case.

Like the better-known soft and weak references, FinalReference objects are treated specially by the GC subsystem, comprising a mechanism that provides an interesting interaction between the VM and Java code (both platform and user).

However, for all its technical interest the implementation is fatally flawed, due to differences in the memory management schemes of the two languages. In the C++ case, dynamic memory is handled manually, with explicit lifetime management of objects under the control of the programmer. This means that destruction can happen as the object is deleted, and so the acquisition and release of resources is directly tied to the lifetime of the object.

Java’s memory management subsystem is a garbage collector that runs as needed, in response to running out of available memory to allocate. It therefore runs at nondeterministic intervals and so the finalize() method is run only when the object is collected, which will be at an unknown time.

Put another way, finalization does not safely implement automatic resource management, as the garbage collector does not run with any time guarantees. This means that there is nothing in the mechanism that ties resource release to the lifetime of the object, and so it is always possible to exhaust resources.

Finalization is not fit for its originally intended main purpose. The advice given to developers by Oracle (and Sun) has, for many years, been to avoid finalization in ordinary application code, and Object.finalize() has been deprecated in Java 9.

try-with-resources

Prior to Java 7 the responsibility of closing a resource was purely in the hands of the developer. As discussed in “War Story: Forgetting to Clean Up” it is easy to forget and not notice the impact of this kind of omission until there is a production problem bearing down on you. The following code sample shows the responsibilities of a developer prior to Java 7:

publicvoidreadFirstLineOld(Filefile)throwsIOException{BufferedReaderreader=null;try{reader=newBufferedReader(newFileReader(file));StringfirstLine=reader.readLine();System.out.println(firstLine);}finally{if(reader!=null){reader.close();}}}

The developer must:

-

Create the

BufferedReaderand initialize it tonullto ensure visibility from thefinallyblock. -

Throw or catch and handle the

IOException(and possibly theFileNotFoundExceptionit hides). -

Perform the business logic interacting with the external resource.

-

Check that the reader isn’t

null, and then close the resource.

This example uses only a single external resource, but the complexity increases dramatically when multiple external resources are handled. If you need a reminder, take a look at raw JDBC calls.

try-with-resources, a language-level construct added in Java 7, allows the creation of a resource to be specified in parentheses following the try keyword. Any object that implements the AutoCloseable interface can be used in the try parentheses. At the end of the scope of the try block, the close() method will be called automatically, rather than the developer having to remember to call the function. The following invocation of the close() method behaves just as in the preceding code example, and is run regardless of an exception being thrown in the business logic:

publicvoidreadFirstLineNew(Filefile)throwsIOException{try(BufferedReaderreader=newBufferedReader(newFileReader(file))){StringfirstLine=reader.readLine();System.out.println(firstLine);}}

Using javap we can compare the bytecode generated by the two versions. Here’s the bytecode from the first example:

publicvoidreadFirstLineOld(java.io.File)throwsjava.io.IOException;Code:0:aconst_null1:astore_22:new#2// class java/io/BufferedReader5:dup6:new#3// class java/io/FileReader9:dup10:aload_111:invokespecial#4// Method java/io/FileReader."<init>":// (Ljava/io/File;)V14:invokespecial#5// Method java/io/BufferedReader."<init>":// (Ljava/io/Reader;)V17:astore_218:aload_219:invokevirtual#6// Method java/io/BufferedReader.readLine:// ()Ljava/lang/String;22:astore_323:getstatic#7// Field java/lang/System.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;26:aload_327:invokevirtual#8// Method java/io/PrintStream.println:// (Ljava/lang/String;)V30:aload_231:ifnull5434:aload_235:invokevirtual#9// Method java/io/BufferedReader.close:()V38:goto5441:astore443:aload_244:ifnull5147:aload_248:invokevirtual#9// Method java/io/BufferedReader.close:()V51:aload453:athrow54:returnExceptiontable:fromtotargettype23041any414341any

The equivalent bytecode from the try-with-resources version looks like this:

publicvoidreadFirstLineNew(java.io.File)throwsjava.io.IOException;Code:0:new#2// class java/io/BufferedReader3:dup4:new#3// class java/io/FileReader7:dup8:aload_19:invokespecial#4// Method java/io/FileReader."<init>":// (Ljava/io/File;)V12:invokespecial#5// Method java/io/BufferedReader."<init>":// (Ljava/io/Reader;)V15:astore_216:aconst_null17:astore_318:aload_219:invokevirtual#6// Method java/io/BufferedReader.readLine:// ()Ljava/lang/String;22:astore424:getstatic#7// Field java/lang/System.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;27:aload429:invokevirtual#8// Method java/io/PrintStream.println:// (Ljava/lang/String;)V32:aload_233:ifnull10836:aload_337:ifnull5840:aload_241:invokevirtual#9// Method java/io/BufferedReader.close:()V44:goto10847:astore449:aload_350:aload452:invokevirtual#11// Method java/lang/Throwable.addSuppressed:// (Ljava/lang/Throwable;)V55:goto10858:aload_259:invokevirtual#9// Method java/io/BufferedReader.close:()V62:goto10865:astore467:aload469:astore_370:aload472:athrow73:astore575:aload_276:ifnull10579:aload_380:ifnull10183:aload_284:invokevirtual#9// Method java/io/BufferedReader.close:()V87:goto10590:astore692:aload_393:aload695:invokevirtual#11// Method java/lang/Throwable.addSuppressed:// (Ljava/lang/Throwable;)V98:goto105101:aload_2102:invokevirtual#9// Method java/io/BufferedReader.close:()V105:aload5107:athrow108:returnExceptiontable:fromtotargettype404447Classjava/lang/Throwable183265Classjava/lang/Throwable183273any838790Classjava/lang/Throwable657573any

On the face of it, try-with-resources is simply a compiler mechanism to autogenerate boilerplate.

However, when used consistently, it is a very useful simplification and can prevent classes from having to know how to release and clean up other classes.

The result is to establish better encapsulation and bug-free code.

The try-with-resources mechanism is the recommended best practice for implementing something similar to the C++ RAII pattern.

It does limit the use of the pattern to block-scoped code, but this is due to the Java platform’s lack of low-level visibility into object lifetime.

The Java developer must simply exercise discipline when dealing with resource objects and scope them as highly as possible—which is in itself a good design practice.

By now, it should be clear that these two mechanisms (finalization and try-with-resources), despite having the same design intent, are radically different from each other.

Finalization relies on assembly code far inside the runtime to register objects for special-case GC behavior. It then uses the garbage collector to kick off the cleanup using a reference queue and separate dedicated finalization threads. In particular, there is little if any trace of finalization in the bytecode, and the feature is provided by special mechanisms within the VM.

By contrast, try-with-resources is a purely compile-time feature that can be seen as syntactic sugar that simply produces regular bytecode and has no other special runtime behavior.

The only possible performance effect of using try-with-resources is that because it leads to a large amount of automatically generated bytecode, it may impact the ability of the JIT compiler to effectively inline or compile methods that use this approach.

However, as with all other potential performance effects, the engineer should measure the effect of using try-with-resources on runtime performance and expend the effort to refactor only if it can be clearly shown that the feature is causing problems.

In summary, for resource management and in almost all other cases, finalization is not fit for purpose. Finalization depends on GC, which is itself a nondeterministic process. This means that anything relying on finalization has no time guarantee as to when the resource will be released.

Whether or not the deprecation of finalization eventually leads to its removal, the advice remains the same: do not write classes that override finalize(), and refactor any classes you find in your own code that do.

Method Handles

In Chapter 9 we met invokedynamic.

This major development in the platform, introduced in Java 7, brings much greater flexibility in determining which method is to be executed at a call site.

The key point is that an invokedynamic call site does not determine which method is to be called until runtime.

Instead, when the call site is reached by the interpreter, a special auxiliary method (known as a bootstrap method, or BSM) is called. The BSM returns an object that represents the actual method that should be called at the call site. This is known as the call target and is said to be laced into the call site.

Note

In the simplest case, the lookup of the call target is done only once—the first time the call site is encountered—but there are more complex cases whereby the call site can be invalidated and the lookup rerun (possibly with a different call target resulting).

A key concept is the method handle, an object that represents the method that should be called from the invokedynamic call site.

This is somewhat similar to concepts in reflection, but there are limitations inherent in reflection that make it inconvenient for use with invokedynamic.

Instead, Java 7 added some new classes and packages (especially java.lang.invoke.MethodHandle) to represent directly executable references to methods.

These method handle objects have a group of several related methods that allow execution of the underlying method.

Of these, invoke() is the most common, but there are additional helpers and slight variations of the primary invoker method.

Just as for reflective calls, a method handle’s underlying method can have any signature. Therefore, the invoker methods present on method handles need to have a very permissive signature so as to have full flexibility. However, method handles also have a new and novel feature that goes beyond the reflective case.

To understand what this new feature is, and why it’s important, let’s first consider some simple code that invokes a method reflectively:

Methodm=...Objectreceiver=...Objecto=m.invoke(receiver,newObject(),newObject());

This produces the following rather unsurprising piece of bytecode:

17:iconst_018:new#2// class java/lang/Object21:dup22:invokespecial#1// Method java/lang/Object."<init>":()V25:aastore26:dup27:iconst_128:new#2// class java/lang/Object31:dup32:invokespecial#1// Method java/lang/Object."<init>":()V35:aastore36:invokevirtual#3// Method java/lang/reflect/Method.invoke// :(Ljava/lang/Object;[Ljava/lang/Object;)// Ljava/lang/Object;

The iconst and aastore opcodes are used to store the zeroth and first elements of the varadic arguments into an array to be passed to invoke().

Then, the overall signature of the call in the bytecode is clearly invoke:(Ljava/lang/Object;[Ljava/lang/Object;)Ljava/lang/Object;, as the method takes a single object argument (the receiver) followed by a varadic number of parameters that will be passed to the reflective call.

It ultimately returns an Object, all of which indicates that nothing is known about this method call at compile time—we are punting on every aspect of it until runtime.

As a result, this is a very general call, and it may well fail at runtime if the receiver and Method object don’t match, or if the parameter list is incorrect.

By way of a contrast, let’s look at a similar simple example carried out with method handles:

MethodTypemt=MethodType.methodType(int.class);MethodHandles.Lookupl=MethodHandles.lookup();MethodHandlemh=l.findVirtual(String.class,"hashCode",mt);Stringreceiver="b";intret=(int)mh.invoke(receiver);System.out.println(ret);

There are two parts to the call: first the lookup of the method handle, and then the invocation of it. In real systems, these two parts can be widely separated in time or code location; method handles are immutable stable objects and can easily be cached and held for later use.

The lookup mechanism seems like additional boilerplate, but it is used to correct an issue that has been a problem with reflection since its inception—access control.

When a class is initially loaded, the bytecode is extensively checked. This includes checks to ensure that the class does not maliciously attempt to call any methods that it does not have access to. Any attempt to call inaccessible methods will result in the classloading process failing.

For performance reasons, once the class has been loaded, no further checks are carried out. This opens a window that reflective code could attempt to exploit, and the original design choices made by the reflection subsystem (way back in Java 1.1) are not wholly satisfactory, for several different reasons.

The Method Handles API takes a different approach: the lookup context.

To use this, we create a context object by calling MethodHandles.lookup().

The returned immutable object has state that records which methods and fields were accessible at the point where the context object was created.

This means that the context object can either be used immediately, or stored.

This flexibility allows for patterns whereby a class can allow selective access to its private methods (by caching a lookup object and filtering access to it).

By contrast, reflection only has the blunt instrument of the setAccessible() hack, which completely subverts the safety features of Java’s access control.

Let’s look at the bytecode for the lookup section of the method handles example:

0:getstatic#2// Field java/lang/Integer.TYPE:Ljava/lang/Class;3:invokestatic#3// Method java/lang/invoke/MethodType.methodType:// (Ljava/lang/Class;)Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodType;6:astore_17:invokestatic#4// Method java/lang/invoke/MethodHandles.lookup:// ()Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodHandles$Lookup;10:astore_211:aload_212:ldc#5// class java/lang/String14:ldc#6// String hashCode16:aload_117:invokevirtual#7// Method java/lang/invoke/MethodHandles$Lookup.findVirtual:// (Ljava/lang/Class;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/invoke/// MethodType;)Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodHandle;20:astore_3

This code has generated a context object that can see every method that is accessible at the point where the lookup() static call takes place.

From this, we can use findVirtual() (and related methods) to get a handle on any method visible at that point.

If we attempt to access a method that is not visible through the lookup context, then an IllegalAccessException will be thrown.

Unlike with reflection, there is no way for the programmer to subvert or switch off this access check.

In our example, we are simply looking up the public hashCode() method on String, which requires no special access.

However, we must still use the lookup mechanism, and the platform will still check whether the context object has access to the requested method.

Next, let’s look at the bytecode generated by invoking the method handle:

21:ldc#8// String b23:astore425:aload_326:aload428:invokevirtual#9// Method java/lang/invoke/MethodHandle.invoke// :(Ljava/lang/String;)I31:istore533:getstatic#10// Field java/lang/System.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;36:iload538:invokevirtual#11// Method java/io/PrintStream.println:(I)V

This is substantially different from the reflective case because the call to invoke() is not simply a one-size-fits-all invocation that accepts any arguments, but instead describes the expected signature of the method that should be called at runtime.

Note

The bytecode for the method handle invocation contains better static type information about the call site than we would see in the corresponding reflective case.

In our case, the call signature is invoke:(Ljava/lang/String;)I, and nothing in the JavaDoc for MethodHandle indicates that the class has such a method.

Instead, the javac source code compiler has deduced an appropriate type signature for this call and emitted a corresponding call, even though no such method exists on MethodHandle.

The bytecode emitted by javac has also set up the stack such that this call will be dispatched in the usual way (assuming it can be linked) without any boxing of varargs to an array.

Any JVM runtime that loads this bytecode is required to link this method call as is, with the expectation that the method handle will at runtime represent a call of the correct signature and that the invoke() call will be essentially replaced with a delegated call to the underlying method.

Note

This slightly strange feature of the Java language is known as signature polymorphism and applies only to method handles.

This is, of course, a very un-Java-like language feature, and the use case is deliberately skewed toward language and framework implementors (as was done with the C# Dynamic feature, for example).

For many developers, one simple way to think of method handles is that they provide a similar capability to core reflection, but done in a modern way with maximum possible static type safety.

Summary

In this chapter, we have discussed some performance aspects of the standard Java Collections API. We have also introduced the key concerns of dealing with domain objects.

Finally, we explored two other application performance considerations that are more concerned with the platform level: finalization and method handles. Both of these are concepts that many developers will not encounter every day. Nevertheless, for the performance-oriented engineer, a knowledge and awareness of them will be useful additions to the toolbox of techniques.

In the next chapter, we will move on to discuss several important open source libraries, including those that provide an alternative to the standard collections, as well as logging and related concerns.