Chapter 14. High-Performance Logging and Messaging

When compared to languages such as C++, the use of Java and the JVM is sometimes considered a tradeoff. Java has achieved increased productivity by reducing the number of lower-level concerns a developer must deal with in day-to-day development. The perceived tradeoff is higher-level language abstraction, leading to increased developer productivity at the expense of low-level control and raw performance.

C++ takes the approach that regardless of any new language features, performance must never be compromised. The C++ philosophy leads to a sophisticated level of control, at the cost that every developer has to manage resources manually or conform to appropriate idioms.

The Java platform takes the approach that the developer should be free from concerns about the low-level details. The benefit of automatic memory management should not be underestimated as a huge productivity boost—the authors have spent many years witnessing the mistakes that can be made and damage done by an unwitting C++ developer, and still have the scars.

However, garbage collection and other higher-level managed abstractions on the JVM can cause a level of unpredictability where performance is concerned. This nondeterminism is, naturally, something that should be minimized in latency-sensitive applications.

Warning

Does this mean that Java and the JVM is not a suitable platform for high-performance systems?

This chapter aims to explore some common concerns that developers need to address when considering high-performance, latency-sensitive applications. It also looks at the design approaches and requirements placed on low-latency systems. Two considerations that are central to low-latency, high-performance systems are logging and messaging.

Logging should be a concern of any Java developer, as a maintainable Java system usually contains a high number of log messages. However, for the latency-conscious developer, logging can take on a special significance. Fortunately, logging is an area where much development and research have been conducted, which we will explore in this chapter.

Messaging systems have provided one of the most successful architectural patterns in recent years. As a result, they are usually at the forefront of low-latency systems and are typically measured in number of messages processed per second. The number of messages a system is capable of processing is often critical to gaining a competitive advantage. The ability to tie a tangible value to throughput (e.g., trades per second) means that this is an area that is heavily researched and funded. We will discuss some modern messaging approaches later in the chapter.

Logging

For many developers, the logging library is not considered an important part of the project, and its selection is a “path of least resistance” process. This is in contrast to many of the other libraries that are introduced into a project, where time is committed to researching their features and perhaps even to reviewing some performance benchmarks.

A few antipatterns surrounding the selection of a production-grade logging system include:

- The “10-year logger”

-

Someone once configured the logger successfully. It is much easier to borrow that config than to recreate it.

- The “project-wide logger”

-

Someone once wrapped the logger to avoid having to reconfigure the logger in each part of the project.

- The “firm-wide logger”

-

Someone once created a logger for the entire firm to use.

Of course, someone is never intentionally trying to create a future problem. There is usually a valid case for logging architecture choices—for example, integration with other functions in an organization, leading to the firm-wide logger. The problem is often around maintenance of the logging system, as it is typically not seen as business-critical. This neglect leads to a technical debt that has the potential to reach across the entire organization. Despite loggers not being exciting and their selection frequently following one of the preceding antipatterns, they are central to all applications.

In many high-performance environments, processing accuracy and reporting are as important as speed. There is no point doing things quickly and incorrectly, and often there can be audit requirements to accurately report processing. Logs help to identify production issues, and should log enough that teams will be able to investigate a problem after the fact. It is important that the logger is not treated simply as a cost but rather like any other component in the system—one that requires careful control and thoughtful inclusion in the project.

Logging Microbenchmarks

This section will explore a set of microbenchmarks intended to fairly compare the performance of the three most popular loggers (Logback, Log4j, and java.util.logging) using various log patterns.

The statistics are based on an open source project by Stephen Connolly and can be found on GitHub. The project is well designed and presented in a runnable benchmark suite, with multiple logger runs with various configurations.

Tip

These benchmarks explore each logger combined with different logging formats to give us an idea of the logging framework’s overall performance and whether the pattern has any impact on performance.

At this point it is essential that we explicitly explain why we are using a microbenchmark approach. When discussing the details of these specific technologies, we faced a similar problem to a library author: we wanted to get an idea of the performance of different loggers based on different configurations, but we knew it would be really tricky to find a good corpus of applications using the exact configurations of logging we needed and produce results that would provide a meaningful comparison.

In this situation, where the code will run in many different applications, a microbenchmark provides an estimate of how that code will perform. This is the “general-purpose, no meaningful corpus exists” use case for microbenchmarks.

The figures give us an overall picture, but it’s imperative to profile the application before and afterward to get a true perspective of the changes before implementing them in a real application.

That said, let’s take a look at the results and how they were achieved.

Measurements

For purposes of comparison the benchmarks have been run on an iMac and on an AWS (Amazon Web Services) EC t2.2xlarge instance (see Tables 14-1 and 14-2). Profiling on macOS can cause problems due to various power-saving techniques, and AWS has the disadvantage that other containers can impact the results of the benchmark. No environment is perfect: there is always noise, and as discussed in Chapter 5, microbenchmarks are full of perils. Hopefully comparison between two datasets of the benchmarks will help uncover useful patterns for guidance in profiling real applications. Remember Feynman’s “you must not fool yourself” principle whenever experimental data needs to be handled.

| No logging | Logback format | java.util.logging format | Log4j format | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Java util logger |

158.051 (±0.762) |

42404.202 (±541.229) |

86054.783 (±541.229) |

74794.026 (±2244.146) |

Log4j |

138.495 (±94.490) |

8056.299 (±447.815) |

32755.168 (±27.054) |

5323.127 (±47.160) |

Logback |

214.032 (±2.260) |

5507.546 (±258.971) |

27420.108 (±37.054) |

3501.858 (±47.873) |

The Java util logger performs its logging operations at between 42,404 ns and 86,054 ns per operation.

The worst-case performance for this logger is using the java.util.logging format—over 2.5× worse than using the same format on Log4j.

Overall Logback offers the best performance from this benchmark run on the iMac, performing best using the Log4j style of logging formatter.

| No logging | Logback format | java.util.logging format | Log4j format | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Java util logger |

1376.597 (±106.613) |

54658.098 (±516.184) |

144661.388 (±10333.854) |

109895.219 (±5457.031) |

Log4j |

1699.774 (±111.222) |

5835.090 (±27.592) |

34605.770 (±38.816) |

5809.098 (±27.792) |

Logback |

2440.952 (±159.290) |

4786.511 (±29.526) |

30550.569 (±39.951) |

5485.938 (±38.674) |

Looking at the benchmarks for AWS, we can see the results show a similar overall pattern to the iMac results. Logback is slightly quicker than Log4j. There are some key takeaways from these results.

Warning

The correct way to measure the impact to the application is to profile the application before and after the configuration is changed on production hardware. The benchmarks that have been run here should be repeated on a configuration that mirrors your specific production machine and not taken as is.

AWS, though, has noticeably quicker execution speeds overall, which could be due to power saving kicking in on the iMac or other factors that have not been captured.

Logger results

The benchmarks reveal that there is a range of results depending on the logging format that is used, the logging framework, and the configuration used. Util logging generally offers the worst performance across the board in terms of execution time. The Log4j format appears to give the most consistent results across the board, with Logback executing the log statement in the best time.

In real systems, it is worth testing execution time performance on production kit, especially when the numbers are this close. Real systems are murky, and only the clearest of signals should be taken as evidence of anything underlying; a few tens of percent is not normally enough.

The danger with microbenchmarks, as discussed in Chapter 5, is that looking at the problem in the small can potentially disguise its impact on our application as a whole. We could make a decision based on these microbenchmarks that would influence the application in other unexpected ways.

The amount of garbage generated by a logging framework might be one such consideration, as would the amount of CPU time spent logging instead of processing business-critical parallel tasks. The design of the logging library and the mechanism by which it works are just as important as the straight-line execution results in the microbenchmarks.

Designing a Lower-Impact Logger

Logging is a critical component of any application, but in low-latency applications it is essential that the logger does not become a bottleneck for business logic performance. Earlier in the chapter, we explored the idea that there is often no conscious process for the developer in selecting an appropriate logger, and no benchmarking. In many circumstances logging surfaces as a problem only when it becomes a large or dominant cost in the application.

To date, I’ve rarely run into a customer whose system wasn’t somehow negatively impacted by logging. My extreme case is a customer that was facing a 4.5-second time budget where logging accounted for 4.2 seconds.

Kirk Pepperdine

The Log4j 2.6 release aims to address the concerns Kirk voiced by introducing a steady-state garbage-free logger.

The documentation highlights a simple test, consisting of running the application in Java Flight Recorder to sample logging a string as often as possible over 12 seconds.

The logger was configured to be asynchronous via a RandomAccessFile appender with the pattern %d %p %c{1.} [%t] %m %ex%n.

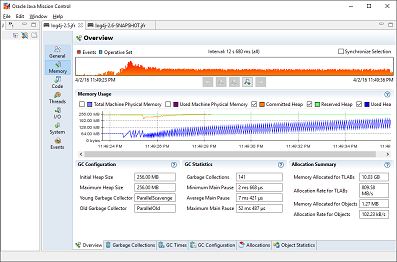

Figure 14-1 demonstrates a non-steady-state garbage collector and a sample profile for comparison. This is not intended to be an accurate microbenchmark but rather an overview of profiling the behavior of logging. The profiler shows significant GC cycles: 141 collections with an average pause time of around 7 ms and a maximum pause time of 52 ms.

Figure 14-1. Sample running Log4j 2.5

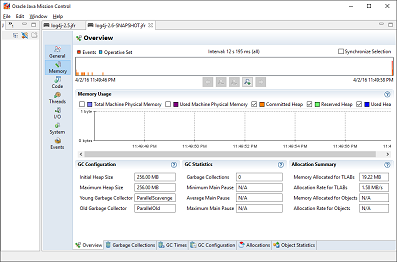

Comparing this to Figure 14-2 shows the difference that Log4j 2.6 provides, with 0 GC cycles kicking in during the same time period.

Figure 14-2. Sample running Log4j 2.6

Log4j 2.6 provides some clear advantages when configured to run as in Figure 14-2. However, there are some limitations due to the way the zero-allocation logger is implemented—as always, there are no free lunches!

Log4j achieves the performance observed by reusing objects, rather than creating temporary objects on each log message.

This is a classic use of the Object Pool pattern, with all of the consequences that come along with it.

Log4j 2.6 reuses objects by using ThreadLocal fields and by reusing buffers for converting strings to bytes.

Warning

This is one of the outcomes that we could not have deduced by looking solely at the microbenchmark. As always, the design and the big picture must be considered.

ThreadLocal objects can be problematic in web containers, in particular when web applications are loaded into and unloaded from the container.

Log4j 2.6 won’t use ThreadLocal when running inside a web container, but it will still use some shared and cached structures to help improve performance.

If an application is already using an older version of Log4j, directly upgrading to 2.6 and reviewing the configuration should be a consideration. Log4j reduces the number of allocations by using varargs, creating a temporary array for parameters being passed in to the log statement. If Log4j is used via SLF4J, the facade will still only support two parameters; using more via SLF4J would require not using a garbage-free approach or refactoring the code base to use Log4j2 libraries directly.

Low Latency Using Real Logic Libraries

Real Logic is a UK-based company founded by Martin Thompson. Martin is known for pioneering the approach of mechanical sympathy, based on an understanding of how lower-level details influence high-performance design. One of Martin’s best-known contributions to the Java space is the Disruptor pattern.

Note

Martin’s blog, also called Mechanical Sympathy, and the associated mailing list are great resources for developers who want to push the performance envelope of their applications.

Real Logic’s GitHub page houses several popular open source projects that build on the expertise of Martin and the other contributors, including:

- Agrona

-

High-performance data structures and utility methods for Java

- Simple Binary Encoding (SBE)

-

A high-performance message codec

- Aeron

-

An efficient reliable UDP unicast, UDP multicast, and IPC message transport

- Artio

-

A resilient, high-performance, FIX gateway

The following sections will explore these projects and the design philosophy that enables these libraries to push the bounds of Java performance.

Note

Real Logic also hosts a resilient high-permanence FIX gateway utilizing these libraries. However, this will not be something we explore further in this chapter.

Agrona

Project Agrona (which derives its name from Celtic mythology in Wales and Scotland) is a library containing building blocks for low-latency applications.

In “Building Concurrency Libraries”, we discussed the idea of using java.util.concurrent at the appropriate level of abstraction to not reinvent the wheel.

Agrona provides a similar set of libraries for truly low-latency applications. If you have already proved that the standard libraries do not meet your use case, then a reasonable next step would be to evaluate these libraries before rolling your own. The project is well unit-tested and documented and has an active community.

Buffers

Richard Warburton has written an excellent article on buffers and the problems with buffers in Java.

Broadly, Java offers a ByteBuffer class, which offers an abstraction for a buffer that is either direct or nondirect.

A direct buffer lives outside of the usual Java heap (but still within the “C heap” of the overall JVM process). As a result, it can often have slower allocation and deallocation rates as compared to an on-heap (nondirect) buffer. The direct buffer has the advantage that the JVM will attempt to invoke instructions directly on that structure without an intermediate mapping.

The main problem with ByteBuffer is the generalized use case, meaning that optimizations specific to the type of buffer are not applied.

For example, they don’t support atomic operations, which is a problem if you want to build a producer/consumer-style model across a buffer.

ByteBuffer requires that every time you wrap a different structure a new underlying buffer is allocated.

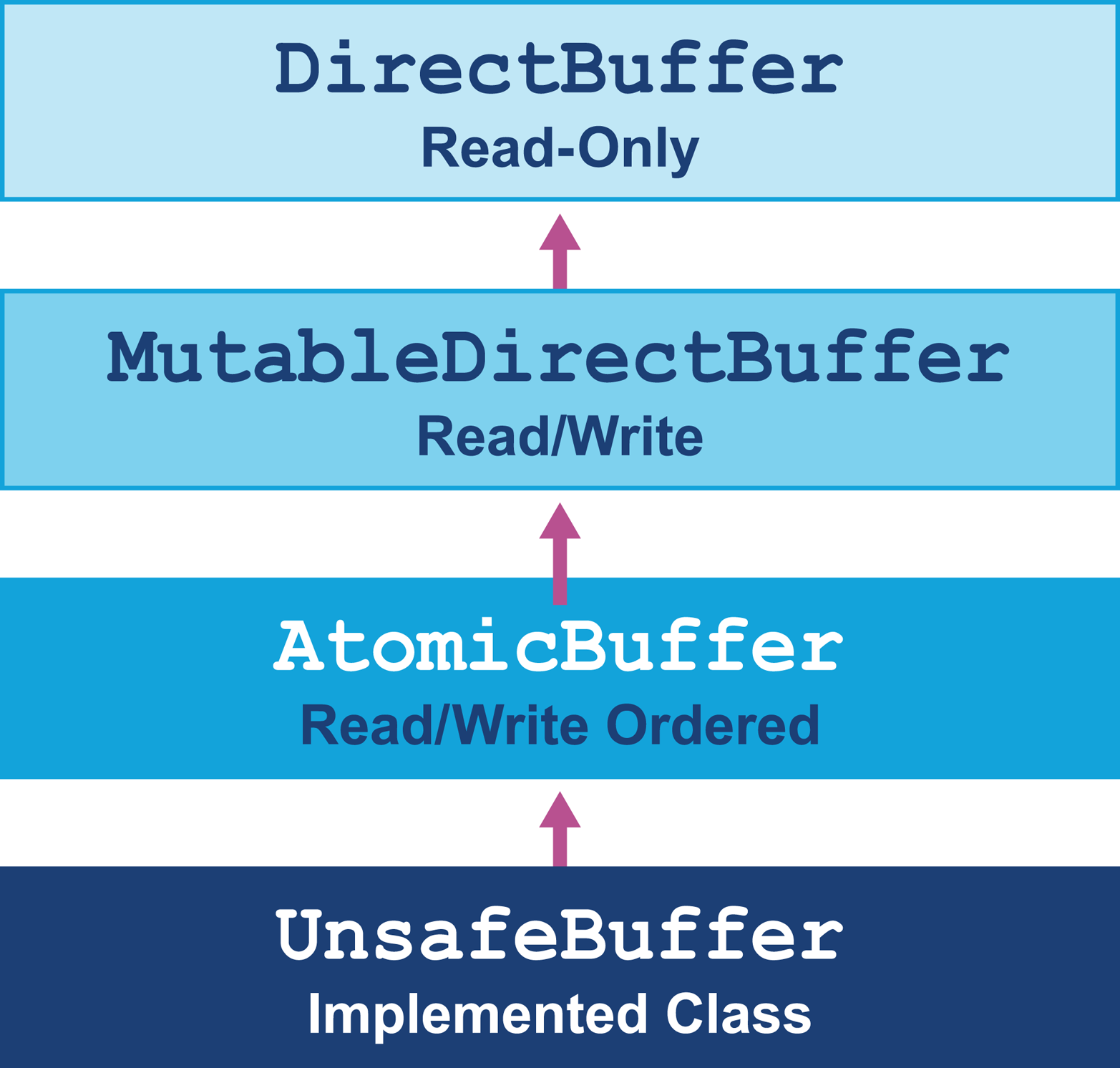

In Agrona the copy is avoided, and it supports four types of buffer with different characteristics, allowing you to define and control the interactions possible with each buffer object:

-

The

DirectBufferinterface provides the ability to read only from the buffer and forms the top level of the hierarchy. -

The

MutableDirectBufferinterface extendsDirectBufferand adds write access to the buffer. -

The

AtomicBufferinterface extendsMutableDirectBuffer, offering ordering behavior. -

UnsafeBufferis the class that usesUnsafeto implementAtomicBuffer.

Figure 14-3 shows the inheritance hierarchy of buffer classes for Agrona’s buffers.

Figure 14-3. Agrona buffers

The code in Agrona, as you might imagine, is very low-level and uses Unsafe extensively, including in this code fragment:

// This horrible filth is to encourage the JVM to call memset()// when address is even.// TODO: check if this still applies when Java 9 is out!!!UNSAFE.putByte(byteArray,indexOffset,value);UNSAFE.setMemory(byteArray,indexOffset+1,length-1,value);

This is not to say that Agrona is hacky in any way—quite the opposite. The need for this code was to bypass an old optimization that was applied inside the JVM that is now an antioptimization. The library has gone down to this level of detail in ensuring maximum performance can be gained.

Agrona buffers allow access to the underlying data through various get methods—for example, getLong(int index).

Even though the buffer is wrapped, it is up to the developer to know at what point the index of their data resides.

In addition, put operations allow putting the long value at a specific point on the buffer. Note that the buffer is not of any single type; it is down to the developer to select and manage the appropriate structure for their data.

Bounds checking can be enabled/disabled, so dead code can be optimized away by the JIT compiler.

Lists, maps, and sets

Agrona provides a series of list implementations that are backed by arrays of ints or long primitives.

As mentioned in “Optimizing Collections”, Java does not have a mechanism of laying out objects side by side in an array, and in standard collections the result is an array of references.

Forcing the usage of an object rather than a primitive in standard collections results in autoboxing and unboxing, in addition to the size overhead of the object itself.

Agrona also supplies ArrayList utilities that allow fast removal from an ArrayList but spoil the ordering.

Agrona’s map and set implementations store keys and values side by side in a hash table structure. If a collision of keys occurs, the next value is stored immediately after that position in the table. This kind of structure lends itself well to quick access of primitive mappings present on the same cache line.

Queues

Agrona has its own concurrent package that contains useful concurrent utilities and structures including queues and ring buffers.

Queues follow the standard java.util.Queue interface, and they can be used in place of a standard queue implementation.

Agrona queues also implement the org.agrona.concurrent.Pipe interface, which adds support for a container processed in sequence.

In particular, Pipe adds support for counting, capacity, and draining operations, to interact easily with consumers of the queue.

The queues are all lockless and use Unsafe to make them appropriate for use in low-latency systems.

The org.agrona.concurrent.AbstractConcurrentArrayQueue provides the first level of support for a series of queues that will provide different producer/consumer models.

One interesting part of this API are these classes:

/*** Pad out a cache line to the left of a producer fields* to prevent false sharing.*/classAbstractConcurrentArrayQueuePadding1{@SuppressWarnings("unused")protectedlongp1,p2,p3,p4,p5,p6,p7,p8,p9,p10,p11,p12,p13,p14,p15;}/*** Values for the producer that are expected to be padded.*/classAbstractConcurrentArrayQueueProducerextendsAbstractConcurrentArrayQueuePadding1{protectedvolatilelongtail;protectedlongheadCache;protectedvolatilelongsharedHeadCache;}/*** Pad out a cache line between the producer and consumer fields to prevent* false sharing.*/classAbstractConcurrentArrayQueuePadding2extendsAbstractConcurrentArrayQueueProducer{@SuppressWarnings("unused")protectedlongp16,p17,p18,p19,p20,p21,p22,p23,p24,p25,p26,p27,p28,p29,p30;}/*** Values for the consumer that are expected to be padded.*/classAbstractConcurrentArrayQueueConsumerextendsAbstractConcurrentArrayQueuePadding2{protectedvolatilelonghead;}/*** Pad out a cache line between the producer and consumer fields to* prevent false sharing.*/classAbstractConcurrentArrayQueuePadding3extendsAbstractConcurrentArrayQueuePadding2{@SuppressWarnings("unused")protectedlongp31,p32,p33,p34,p35,p36,p37,p38,p39,p40,p41,p42,p43,p44,p45;}/*** Leftover immutable queue fields.*/publicabstractclassAbstractConcurrentArrayQueue<E>extendsAbstractConcurrentArrayQueuePadding3implementsQueuedPipe<E>{...}

Note

It is worth noting that sun.misc.contended (or jdk.internal.vm.annotation.Contended) may be made available to generate this kind of cache line padding in the future.

The code fragment from AbstractConcurrentArrayQueue shows a clever (forced) arrangement of the queue memory to avoid false sharing when the queue is accessed by the consumer and producer concurrently.

The reason that we require this padding is because the layout of fields in memory is not guaranteed by Java or the JVM.

Putting the producer and consumer on separate cache lines ensures that the structure can adequately perform in a low-latency, high-throughput situation. Cache lines are used to access memory, and if the producer and consumer shared the same cache line, problems would occur when the cache line was accessed concurrently.

There are three concrete implementations, and separating out the implementation in this way enables coordination in code only where necessary:

OneToOneConcurrentArrayQueue-

If we choose one producer and one consumer, we are opting into a policy that the only concurrent access occurring is when the producer and consumer are accessing the structure at the same time. The main point of interest is the head and tail positions, as these are only updated by one thread at a time.

The head can only be updated by a poll or drain operation to take from the queue, and the tail can only be updated by a

put()operation. Selecting this mode avoids unnecessary loss of performance due to additional coordination checks, which are required by the other two types of queue. ManyToManyConcurrentArrayQueue-

Alternatively, if we choose to have many producers, then additional controls are required for the updating of the tail position (as this may have been updated by another producer). Using

Unsafe.compareAndSwapLongin awhileloop until the tail is updated ensures a lock-free way of updating the queue tail safely. Again, there is no such contention on the consumer side, as we are guaranteeing one consumer. ManyToOneConcurrentArrayQueue-

Finally, if we choose to have many producers and consumers, then coordination controls are needed for the update of the head or the tail. This level of coordination and control is achieved by a

whileloop wrapping acompareAndSwap. This will require the most coordination of all of the alternatives and so should be used only if that level of safety is required.

Ring buffers

Agrona provides org.agrona.concurrent.RingBuffer as an interface for exchanging binary-encoded messages for interprocess communication.

It uses a DirectBuffer to manage the storage of the message off-heap.

Thanks to some ASCII art in the source code, we can see that messages are stored in a RecordDescriptor structure:

*0123*01234567890123456789012345678901*+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+*|R|Length|*+-+-------------------------------------------------------------+*|Type|*+---------------------------------------------------------------+*|EncodedMessage...*...|*+---------------------------------------------------------------+

There are two types of ring buffer implemented in Agrona, the OneToOneRingBuffer and the ManyToOneRingBuffer.

The write operation takes a source buffer to write a message to the buffer, whereas read operations are called back on an onMessage style of handler.

Where many producers are writing in the ManyToOneRingBuffer, a call to Unsafe.storeFence() manually controls memory synchronization.

The store fence “ensures lack of reordering of stores before the fence with loads or stores after the fence.”

Agrona has many low-level structures and interesting aspects. If the software system that you are looking to build is at this level of detail, this project is a great first step to experiment with.

There are other projects available, such as JCTools, that also provide variations for concurrent queue structures. Unless a very specific use case is required, developers should not ignore the existence of these open source libraries and should avoid reinventing the wheel.

Simple Binary Encoding

SBE was developed to meet the need for a binary encoding representation suitable for low-latency performance. The encoding was created specifically for the FIX protocol used in financial systems.

Simple Binary Encoding (SBE) provides different characteristics than other binary encodings. It is optimized for low latency. This new FPL binary encoding complements the existing only binary encoding developed in 2005 (FAST) with a focus on reducing bandwidth utilization for market data.

Simple Binary Encoding specification Release Candidate 1

SBE is an application-layer concern used for encoding and decoding messages; the buffers that are used in SBE are from Agrona. SBE has been optimized to allow low-latency messages to pass through the data structure without triggering GC and optimizing concerns such as memory access. It was designed specifically for the high-frequency trading environment, where responding to market events often must happen in micro- or nanoseconds.

Note

The SBE encoding was defined within the FIX protocol organization only in contrast to competing proposals to encode FIX with Google Protocol Buffers and ASN.1.

Another key nonfunctional requirement of high-frequency trading is that operation should be consistently fast. One of the authors has witnessed a system that would process messages at a reasonably high throughput, then suddenly would pause for two minutes due to a GC bug. This kind of pause would be completely unacceptable in a low-latency application, and avoiding garbage collection altogether is one way to ensure consistent performance. These types of performance issues will be identified via a soak test or other long-running performance exercise.

The goal of low-latency applications is to squeeze every possible measure of performance out of the application. This can lead to an “arms race” where teams at competing trading firms try to outdo each other in reducing latency through a trading application’s critical path.

The authors of SBE proposed a series of design principles to reflect these concerns and explain their thinking. We will explore some of the design decisions and how they relate to low-latency system design in the following sections.

Copy-free and native type mapping

Copying comes at a cost, and anyone who has done any programming in C++ will probably have been caught out from time to time copying objects accidentally. Copying isn’t expensive when objects are small, but as the size of objects increases so does the cost of the copy.

High-level Java programmers may not always consider this problem, as they are so used to working with references and having memory automatically managed. The copy-free technique in SBE is designed to ensure that no intermediate buffers are used when encoding or decoding messages.

Writing to the underlying buffer directly does, however, come at a design cost: larger messages that cannot fit in the buffer aren’t supported. In order to support them, a protocol would have to be built in to segment the messages and reassemble them.

Types that natively map to sensible assembly instructions also help when you are working with a copy-free design. Having a mapping that corresponds to a good selection of assembly operations dramatically improves the performance of field retrieval.

Steady-state allocation

Allocating objects in Java introduces a natural problem where low-latency applications are concerned. The allocation itself requires CPU cycles (even if it’s very small, such as a TLAB allocation), and then there’s the problem of deleting the object after the usage is complete.

GC is often stop-the-world, which introduces a pause. This is true even of more advanced collectors that work mostly concurrently. Even when limiting the absolute pause time, the process of GC can introduce a meaningful variance in the performance model.

Tip

It might seem natural to think that C++ could help to resolve that problem, but allocation and deallocation mechanisms can also introduce problems. In particular, some memory pools may employ a locking mechanism that damages performance.

SBE is allocation-free because it uses the flyweight pattern over the underlying buffer.

Streaming access and word-aligned access

Access to memory is something that we would not normally have control over in Java. In “Optimizing Collections”, we discussed ObjectLayout, which is a proposal to store objects in alignment like in C++ vectors. Normally arrays in Java are arrays of references, meaning reading in memory sequentially would not be possible.

SBE is designed to encode and decode messages in a forward progression that also is framed correctly to allow for good word alignment. Without good alignment, performance issues can start to occur at the processor level.

Working with SBE

SBE messages are defined as XML schema files specifying the layout of the messages. Although XML is nowadays quite generally disliked, schemas do give us a good mechanism for specifying a message interface accurately. XML also has instant toolchain support in IDEs such as Eclipse and Intellij.

SBE provides sbe-tool, a command-line tool that, when given a schema, allows you to generate the appropriate encoders and decoders.

The steps to get this to work are as follows:

# Fork or clone the project

git clone git@github.com:real-logic/simple-binary-encoding.git

# Build the project using your favorite build tool

gradle

# The sbe-tool will be created in

sbe-tool/build/libs

# Run the sbe-tool with a schema-a sample schema is provided at

# https://github.com/real-logic/simple-binary-encoding/blob/master/

sbe-samples/src/main/resources/example-schema.xml

java -jar sbe-tool-1.7.5-SNAPSHOT-all.jar message-schema.xml

# When this command completes it will generate a series of .java files in the

baseline directory

$ ls

BooleanType.java GroupSizeEncodingEncoder.java

BoostType.java MessageHeaderDecoder.java

BoosterDecoder.java MessageHeaderEncoder.java

BoosterEncoder.java MetaAttribute.java

CarDecoder.java Model.java

CarEncoder.java OptionalExtrasDecoder.java

EngineDecoder.java OptionalExtrasEncoder.java

EngineEncoder.java VarStringEncodingDecoder.java

GroupSizeEncodingDecoder.java VarStringEncodingEncoder.java

It is important to remember that one of the core parts of the SBE protocol is that the messages must be read in order, which means essentially as defined in the schema. The tutorial to start working with these messages is outlined in the SBE Java Users Guide.

Aeron

Aeron is the final product in the Real Logic stack that we will explore. It should be no surprise that we’ve left this until last, as it builds upon both SBE and Agrona. Aeron is a UDP (User Datagram Protocol) unicast, multicast, and IPC (inter-process communication) message transport written for Java and C++. It is media layer–agnostic, which means that it will also work nicely with InfiniBand.

Essentially, this is a general, all-encompassing messaging protocol that you can use to get applications to speak to each other via IPC on the same machine or over the network. Aeron is designed to have the highest throughput possible and aims to achieve the lowest and most predictable latency results (consistency being important, as we discussed in “Simple Binary Encoding”). This section explores the Aeron API and discusses some of the design decisions.

Why build something new?

One of the primary reasons for building a new product such as Aeron is that some products in the market have become more general. This is not meant as a criticism, but when customers demand features (and are usually paying for them), it can push a product in a particular direction. The products can become bloated and provide many more features than originally intended, perhaps even becoming frameworks.

Messaging systems in low-level Java are quite fun to build and may start life as a pet project inside a company or in the open source community. The potential problem is that a lack of experience with what is needed from a low-latency perspective can make it hard to take these pet projects and make them production-ready. Ensuring that a product is built for low latency from the ground up without sacrificing performance remains a difficult challenge.

As this chapter has highlighted, the strong design principle behind Aeron is that it is built as a library of components. This means that you are not bound to a framework, and if you only require a low-level data structure then Agrona will provide that, without the need to bring in many other dependencies.

Publishers

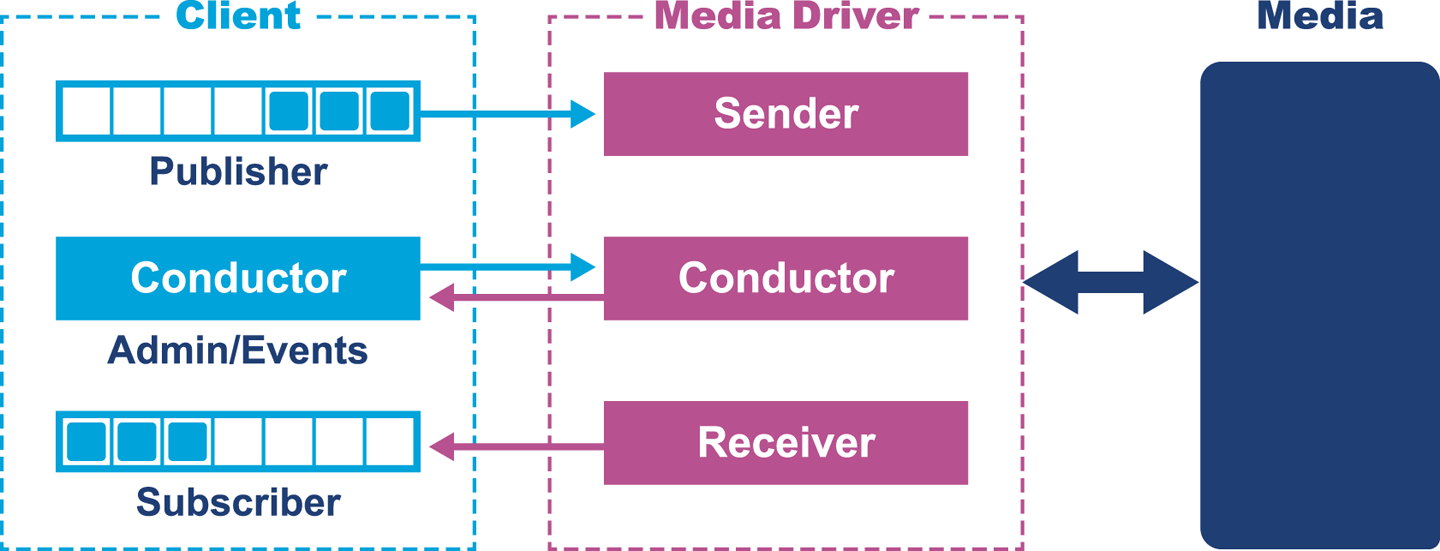

Before we discuss Aeron in depth, it is useful to understand some of the higher-level components depicted in Figure 14-4.

Figure 14-4. Architecture overview of Aeron’s major components

Specifically:

-

Media refers to the mechanism over which Aeron will communicate; for example, this could be UDP or IPC. It could also be InfiniBand or another medium. The main point is Aeron as a client has an abstraction away from this.

-

The media driver refers to the connection between the media and Aeron, allowing configuration to be set and communication to occur with that transport.

-

The conductor is responsible for administration, such as setting up the buffers and listening to requests for new subscribers and publishers. It will also look for NAKs (Negative Acknowledgments) and arrange for retransmission. The conductor allows the sender and receiver to just deal with shifting bytes for maximum throughput.

-

The sender reads data from producers and sends it out on sockets.

-

The receiver reads data from the sockets and forwards it on to the corresponding channel and session.

The media driver is usually a separate process that provides the buffers to be used for transmitting and receiving messages.

Different media drivers can be used to exploit optimizations on different hardware deployments; the MediaDriver.Context is the configuration that sets up the optimizations for that media driver.

The media driver can also be launched in an embedded way within the same process; the embedded process can be configured with a context or through system properties.

Starting up an embedded media driver can be done as follows:

finalMediaDriverdriver=MediaDriver.launch();

The Aeron applications need to connect to the media driver as either publishers or subscribers. The Aeron class makes this fairly straightforward. Aeron also has an inner Context class that can be used to configure the settings:

finalAeron.Contextctx=newAeron.Context();

Aeron can then connect a publication to communicate over a given channel and stream.

Because a Publication is AutoClosable, it will be automatically cleaned up when the try block finishes executing:

try(Publicationpublication=aeron.addPublication(CHANNEL,STREAM_ID)){...}

To send a message a buffer is offered to the publisher, with the result of the offer determining the state of the message.

Publication has a series of long constants that represent a mapping of errors that can be compared to the long result from the offer() method:

finallongresult=publication.offer(BUFFER,0,messageBytes.length);

Sending a message is as simple as that, but in order for this to be of any use a subscriber should be listening to the same media driver.

Subscribers

The subscriber’s startup is similar to the publisher’s: the media driver needs to be accessed and then the Aeron client connects. The components of a consumer mirror the image shown in Figure 14-4. The consumer registers a callback function that is triggered when a message is received:

finalFragmentHandlerfragmentHandler=SamplesUtil.printStringMessage(STREAM_ID);try(Aeronaeron=Aeron.connect(ctx);Subscriptionsubscription=aeron.addSubscription(CHANNEL,STREAM_ID)){SamplesUtil.subscriberLoop(fragmentHandler,FRAGMENT_COUNT_LIMIT,running).accept(subscription);}

These examples have just explored the basic setup; the Aeron project has samples that explore more advanced examples.

The Design of Aeron

Martin Thompson’s talk at Strange Loop provides an extremely good introduction to Aeron and the reason why it was built. This section will explore some of the discussion in the video, in conjunction with the open documentation.

Transport requirements

Aeron is an OSI layer 4 transport for messaging, which means it has a series of responsibilities that it must comply with:

- Ordering

-

Packets will be received out of order from lower-level transports, and it is responsible for reordering out-of-sequence messages.

- Reliability

-

Problems will occur when data is lost, and it must make a request to retransmit that data. While the request for old data is in progress, the process of receiving new data should not be impeded. Reliability in this context refers to connection-level reliability rather than session-level reliability (e.g., fault tolerance over multiple process restarts).

- Back pressure

-

Subscribers will come under pressure under high-volume scenarios, so the service must support flow control and back-pressure measures.

- Congestion

-

This is a problem that can occur on saturated networks, but if a low-latency application is being built it should not be a primary concern. Aeron provides an optional feature to activate congestion control; users that are on low-latency networks can turn it off and users sensitive to other traffic can turn it on. Congestion control can impact a product that in the optimal path has adequate network capacity.

- Multiplexing

-

The transport should be capable of handling multiple streams of information across a single channel without compromising the overall performance.

Latency and application principles

Aeron is driven by eight design principles, as outlined on the Aeron Wiki:

- Garbage-free in steady-state running

-

GC pauses are a large cause of latency and unpredictability in Java applications. Aeron has been designed to ensure steady state to avoid GC, which means it can be included in applications that also observe this same design decision.

- Apply Smart Batching in the message path

-

Smart Batching is an algorithm that is designed to help handle the situation when burst messages are received. In many messaging systems, it is incorrect to assume that messages will be received steadily throughout the day. It is more likely that messages are received in bursts due to business-based events. While processing a message, if another message is received it can also be bundled into the same network packet, up to capacity. Using appropriate data structures, Aeron enables this batching to work without stalling producers writing to the shared resource.

- Lock-free algorithms in the message path

-

Locking introduces contention where threads can be blocked while other threads run; even parking and waking from locks can slow down an application. Avoiding locks prevents the slowdowns that they can cause. Locks and lock-free techniques are discussed in more detail in Chapter 14.

- Nonblocking I/O in the message path

-

Blocking I/O can block a thread, and the cost of waking is high. Using nonblocking I/O avoids these costs.

- No exceptional cases in the message path

-

Applications spend the majority of their time executing primary scenarios and not smaller edge-case scenarios. Edge-case scenarios should be handled, but not at the cost of the execution speed of the primary scenarios.

- Apply the Single Writer Principle

-

As discussed with the

ManyToOneConcurrentArrayQueuein “Queues”, having multiple writers involves a high degree of control and coordination to access the queue. Establishing a single writer significantly simplifies this policy and reduces contention on writing. Aeron publication objects are thread-safe and support multiple writers, but subscribers are not thread-safe—one is required per thread that you want to subscribe on. - Prefer unshared state

-

A single writer solves the problem of contention on the queue, but also introduces another point at which mutable data has to be shared. Maintaining private or local state is far preferred in all walks of software design, as it considerably simplifies the data model.

- Avoid unnecessary data copies

-

As we have mentioned, data is normally cheap to copy, but the invalidation of cache lines and potential to evict other data causes a problem in both Java and C++. Minimizing copies helps to prevent this accidental churn of memory.

How it works under the hood

Many existing protocols introduce complicated data structures, such as skip lists, to try to build effective message processing systems. This complexity, mainly due to indirection of pointers, leads to systems that have unpredictable latency characteristics.

Fundamentally Aeron creates a replicated persistent log of messages.

Martin Thompson

Aeron was designed to provide the cleanest and simplest way of building a sequence of messages in a structure. Although it might not seem like the most likely choice initially, Aeron makes significant use of the concept of a file. Files are structures that can be shared across interested processes, and using the memory-mapped file feature of Linux directs all calls to the file to memory rather than a physical file write.

Note

Aeron by default maps to tmpfs (which is volatile memory mounted like a file). The performance is significantly better than with a disk-memory-mapped file.

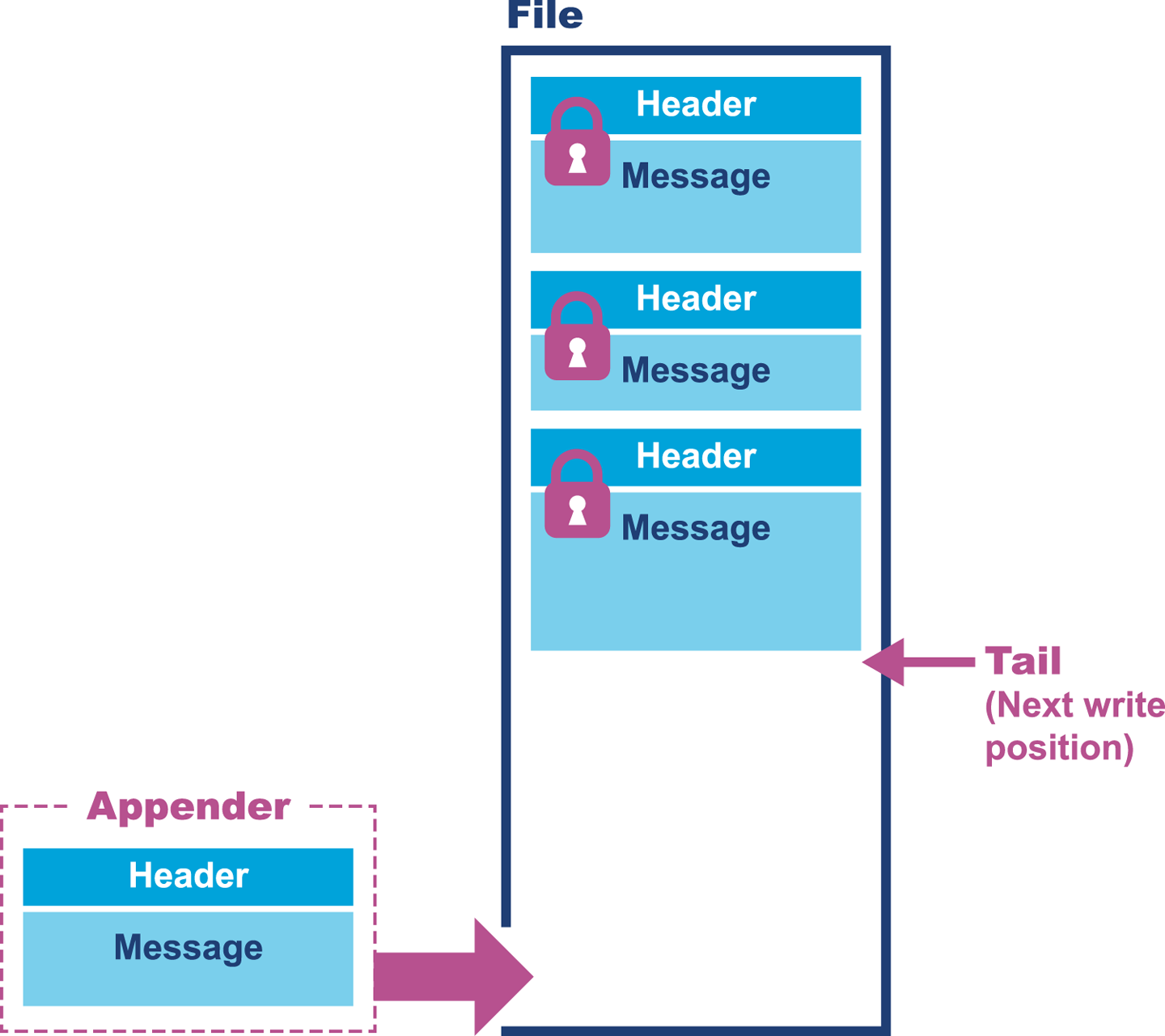

The tail pointer is used to keep track of where the last message was written. Figure 14-5 shows a single message has been written into our current file along with the header.

Figure 14-5. Messages written to a file

The sequencing of events is quite interesting here. The tail pointer reserves the space for the message in the file. The increment of the tail is atomic, and therefore the writer knows the beginning and end of its section.

Note

The Critical Patch Update intrinsic to making this increment atomic was added as part of Java 8.

This allows multiple writers to update the file in a lock-free manner, which is what effectively establishes the file writing protocol. The message is then written, but how can we tell that it’s finished? The header is the last thing to be written atomically to the file. Its presence tells us that the message is complete.

Files are persistent structures that grow when written and do not mutate. Reading records from the file does not require locks, as the file can be opened and read only by an observing process. But is it possible to simply have a file that grows infinitely?

This introduces a lot of problems due to page faults and page churn being introduced in our previously nicely memory-mapped file. We address this concern by having three files: active, dirty, and clean. Active represents the file currently being written to, dirty is the file that was previously written to, and clean is the next file for writing to. The files are rotated to avoid latency caused by bigger files.

Messages are never allowed to go across files. If the tail is pushed off the end of the active file, the insertion process pads the remainder of the file and writes the message into the clean file. From the dirty file it is possible to archive and deep-store the transaction log permanently.

The mechanism for handling missing messages is also really clever and avoids the skip lists and other structures mentioned earlier. The header of the message contains the message’s ordering. When a message is inserted, if it comes out of order a space is left for the previous messages(s). When the missing message is received, it can be inserted in the correct position in the file. This gives an ever-increasing series of messages with no gaps or other structures involved. Ordering data incrementally also has the added benefit of being incredibly quick to work with from a mechanical sympathy perspective.

A watermark represents the current position of the last received message. If the watermark and tail end up being different for a period of time, it indicates missing messages. To resolve the missing messages, NAKs are sent to request them. A NAK can be sent for a message and populated once the message is received.

One interesting side effect of this protocol is that every message received has a unique way of identifying the bytes in each message, based on the streamId, sessionId, termId, and termOffset.

The Aeron Archive can be used to record and replay messaging streams.

By combining the archive and this unique representation it is possible to uniquely identify all messages throughout the history.

The logfile is at the heart of Aeron’s ability to maintain speed and state. It is also a simple, elegantly executed design that allows the product to compete with—and in many cases beat—well-established (and pricey) multicast products.

Summary

Logging is an unavoidable part of all production-grade applications, and the type of logger used can have a significant impact on overall application performance. It is important to consider the application as a whole when it comes to logging (not just the execution of the log statement), as well as the impact it has on other JVM subsystems such as thread usage and garbage collection.

This chapter contains some simple examples of low-latency libraries, starting from the lowest level and progressing all the way up to a full messaging implementation. It is clear that the goals and objectives of low-latency systems need to be applied throughout the software stack, right from the lowest level of queues up to the higher-level usage. Low-latency, high-throughput systems require a great deal of thought, sophistication, and control, and many of the open source projects discussed here have been built from a huge wealth of experience. When you are creating a new low-latency system, these projects will save you days, if not weeks, of development time, provided you adhere to the low-level design goals up to the top-level application.

The chapter started by asking to what extent Java and the JVM can be used for high-throughput applications. Writing low-latency, high-throughput applications is hard in any language, but Java provides some of the best tooling and productivity of any language available. Java and the JVM do, however, add another level of abstraction, which needs to be managed and in some cases circumvented. It is important to consider the hardware, the JVM performance, and much lower-level concerns.

These lower-level concerns are not normally surfaced during day-to-day Java development. Using newer logging libraries that are allocation-free, and the data structures and messaging protocols discussed in this chapter, significantly lowers the barrier to entry, as much of the complexity has been solved by the open source community.