Chapter 13. Wireless Data with Bluetooth

When you hear the term Bluetooth, you might think first of telephone headsets, speakers, computer mice, or keyboards. These have nothing to do with Internet connections, right? Right. At least at first glance. However, closer examination reveals that Bluetooth may have a role to play in Internet-connected devices.

One of the hurdles of data transmission with WiFi is the need to set up an Internet connection, often manually, by selecting a network or providing a network password. This often hinders the design and development of connected experiences. Bluetooth has the potential to ease entry into a connected system. With Bluetooth, you can connect directly to devices, skipping configuration of networks or Internet access points. You can then build clever gateways to provide small data packages, depending on your location or profile.

The Bluetooth Low Energy Protocol

There are two kinds of Bluetooth currently in common use: the high-bandwidth Bluetooth popularized for telephone headsets, and the newer Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), also known as Smart Bluetooth and Bluetooth 4.0. The two protocols are entirely different from each other. Both can be used for building “smart” objects, but BLE is more common in IoT applications due to its low power consumption. Here are a few Bluetooth-based IoT applications:

-

Bluetooth can be used for discovering and identifying devices and services such as data from physical objects. This data can help to make information from elsewhere apparent/visible/tangible in your physical surroundings—for example, a tempescope can visualize weather conditions, or BLE beacons can be strategically placed in a store to let customers know of current promotions.

-

It can help to control things in the range of the Bluetooth radio, which is typically around 10–30 meters depending on how many other devices and humans communicate. This can be nice for automated lighting systems and robots that fly (small drones) or drive (small vehicles).

Note

Bluetooth is named after Harald Bluetooth, King of Denmark. The king’s name served as a placeholder for the project name when the technology was developped in the research labs of Ericsson in the 1990s. Bluetooth was first used to connect headphones to phones, but quickly spread into different realms of wireless data transmission.

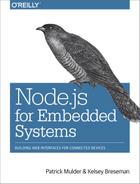

The Bluetooth Low Energy protocol stack, shown in Figure 13-1, can be a bit daunting to understand at first. To adapt to the needs of IoT applications, additional specs have been introduced.

Figure 13-1. The Bluetooth Low Energy Protocol stack (source: https://www.bluetooth.com/specifications/bluetooth-core-specification)

From a software perspective, we are interested mainly in the upper layers of the Bluetooth protocol stack. But the underlying layers are important for application design as well, especially if you want to buy hardware for your products.

In Figure 13-1, you can see that the protocol stack builds on three main layers:

- Application layer

-

Applications can use Bluetooth to communicate with remote devices (i.e., asking for or providing data). To help you understand this process, imagine a conversation between applications as strings of bytes. These strings of bytes can take two modes. Either they advertise properties to “scanning” devices, or they provide connections between devices.

- Host layer

-

To assemble the string of bytes, there are abstractions such as “generic profiles” and “attributes.” These abstractions provide information about the broadcasting device—whether it is a watch or light, for example.

- Controller layer

-

On the lowest layer, data is transmitted without intimate knowledge of the data. This is done with circuits and chips that handle the Bluetooth radio signals.

The host and controller can be integrated on the same chip or can be separated. The bridge between host and controller is called the host-controller-interface (HCI) around which some tools are built (such as the hcitool).

To understand the different aspects of the host and application layers, it is necessary to look at the communication modes between devices. This will help you get a better feeling for the profiles and attributes of Bluetooth devices.

Communication Modes

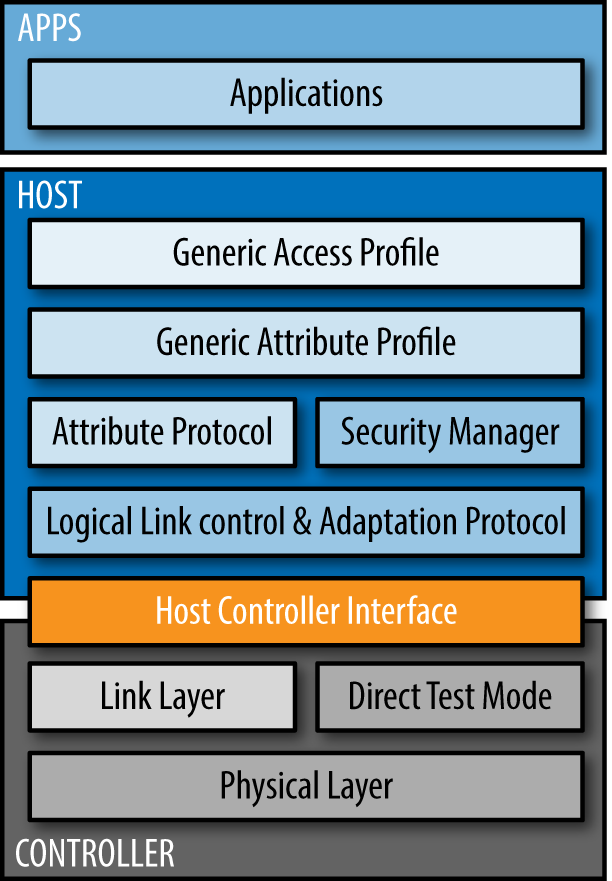

When it comes to communication, devices act either as a central or a peripheral. A common “central” is your smartphone, which can scan for or control peripherals in your environment. Examples of “peripherals” are smart watches or some connected lightbulbs. The location of a device can be identified from the signal strength between devices.

With BLE, communication can happen in two modes. The first mode is the “advertisement” mode, as shown in Figure 13-2. In this mode, a peripheral advertises data packages that might be interesting to centrals. For this, no pairing (or connection) is necessary. While the peripheral advertises its services, the central can capture the packages through scanning their environment. This communication mode is what makes so-called Bluetooth “beacons” work.

Figure 13-2. The advertisement mode

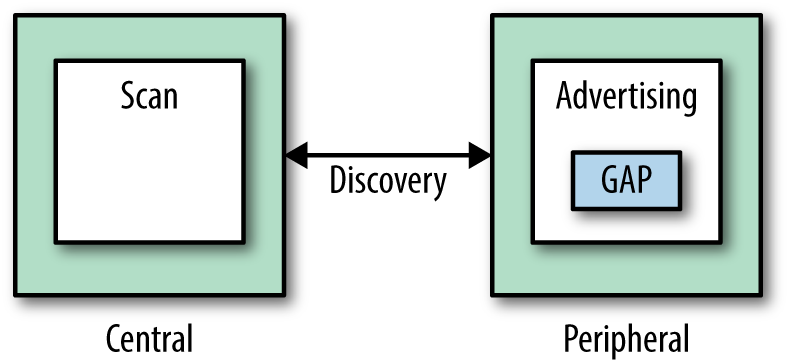

When a central and peripheral device connect, they enter the second BLE communication mode. In this mode, data can be transmitted through services and characteristics, as shown in Figure 13-3.

Figure 13-3. Connection mode

When devices are connected, services are the main grounds for communication. A service says something about the main features of a device and are identified by universally unique identifiers (UUIDs). To get a sense of services and some official UUIDs, take a look at the Bluetooth SIG list. In addition to the official list of 16-bit-long UUIDs, you can define your own services with 128-bit UUIDs.

The generic attribute protocol (GATT) defines a generic hierarchy of data that a peripheral exposes. Attributes are identified with 128-bit unique IDs. These are called “characteristics,” and they define whether data can be written or read, and how to notify a device about changes. A characteristic can have one or many attributes. Each attribute in a characteristic has a unique identifier.

GATT clients may use the attribute identifier to access and modify it. This is done with “write” and “read” operations.

Connect with Centrals

Many mobile phones come with Smart Bluetooth technology by default, which makes mobile phones a good starting point for exploring Bluetooth.

The smartphone typically plays the role of a central, which connects to a peripheral. Support of Bluetooth on smartphones depends on both the operating system and its underlying chipset. Many smartphones, particularly older Android devices, do not support BLE protocols out of the box.

When you work with a smartphone, apps play an important role. You will find a number of apps to discover BLE services in the Play store or on iTunes (LightBlue is a good example on iOS).

If you don’t have a smartphone with BLE support, you can also use a Raspberry Pi, Intel Edison, or Tessel to act as central.

Note

Many smartphones can also act as peripherals. For example, when you control music from your smart watch on a smartphone, the phone is a peripheral to the watch. Modern smartphones also support a beacon mode to broadcast presence. In some cases, it is not possible to turn the device into a peripheral because of chipset limitations.

Another option to work with Bluetooth devices around you is via a web browser. With modern browsers, you can discover beacons through the new Web Bluetooth API. For example, Opera supports some operations to query profiles. Also, Google Chrome allows you to connect to a device and query characteristics.

Beacons

Beacons emit data, such as an ID or other attributes. In this way, they can tell other devices something about data in the environment. The format of the beacon’s advertising data plays a special role and varies between different companies. The most famous beacon formats are Apple’s iBeacon and Google’s EddyStone, though there are also other specifications including the open source AltBeacon.

Invented by Apple, the iBeacon standard describes a special form of advertising of data from devices. Scanning devices pick these sequences of bytes up and can compare them against an external database. The data contains “major” and “minor” identifiers, which are used to differentiate individual stores and locations, respectively.

Invented by Google, the Eddystone specs describe advertisement of URLs. The specs can be found here: https://github.com/google/eddystone/blob/master/protocol-specification.md. Eddystone is one of the cornerstones of Google’s Physical Web, an initiative to make physical objects “smart” by having each broadcast an associated URL.

To develop applications with beacons, you need some hardware, such as the options shown in Figure 13-4. There are also cheaper options that offer a nice start in Bluetooth-based experiences.

The Gimbal beacons by Qualcomm support both the iBeacon and Eddystone standards. The Gimbal beacons are interesting for their size, price, and battery life. For a nice tutorial on using Gimbal beacons with Node.js, check out “Beacon Tracking with Node.js and Raspberry Pi”.

Figure 13-4. The Gimbal (left) and Tile (right) are just two examples of BLE beacons

RedBear Shields and Boards

If you are looking for Bluetooth hardware comparable to Arduino, RedBear Labs offers a nice collection of Bluetooth boards:

- RedBear Duo

-

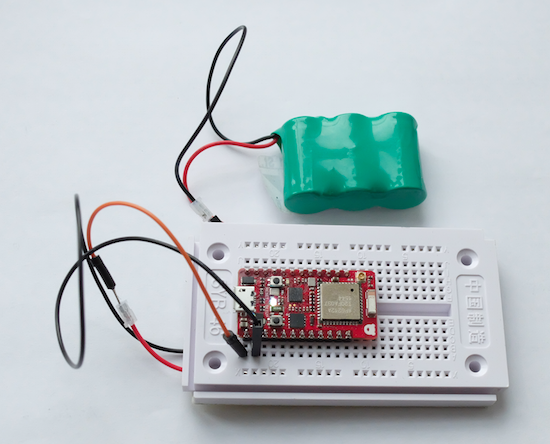

In this recent Kickstarter project, RedBear included a BLE module and a WiFi module, as shown in Figure 13-5. The board is similar to a Particle. As you can see in the figure, it is possible to add batteries on the VIN pins of the board as shown. This makes the boards suitable to design responsive environments.

Figure 13-5. The RedBear Duo powered by a battery supports BLE, WiFi, and Arduino

- RedBear Blend, Micro, and Mini

-

In addition to the Duo, you’ll find boards and shields that add Bluetooth capabilities to an Arduino. Instructions for how to set up these boards with the Arduino Board manager are found here: https://github.com/RedBearLab/Blend and https://github.com/RedBearLab/nRF8001.

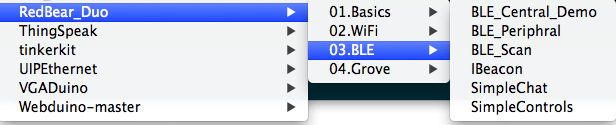

Once you have imported the board data with the Arduino board manager, you have access to a number of Arduino examples, as shown in Figure 13-6.

Figure 13-6. Arduino BLE examples from RedBear board

As many Arduino boards are based on a Nordic Semiconductor nRF_8001, there exists a special Node.js library to interact with these Bluetooth devices. It can be found at https://github.com/sandeepmistry/arduino-BLEPeripheral.

BlueIOT

The BlueIOT module is based on the BlueGiga BLE113, as shown in Figure 13-7.

Figure 13-7. BlueIOT board from fab-lab.eu (via tindie.com)

It has a couple of advantages compared to other solutions:

-

BlueIOT has a very small form factor and can be powered from a coin cell battery, and sleeping currents can be smaller than 1 uA.

-

It uses a FCC/Bluetooth-certified BLE module. This can save you time and costs if you want to develop your own BLE products later.

-

The module comes with an ATmega328p chip that can be easily programmed with the Arduino toolchain.

-

It is possible to update the module with OTA and connectivity configuration could be scripted with bgscript. This helps to separate application logic and communication logic, as well as reduce the load on the host processor.

Libraries for Bluetooth

Now that we’ve covered the hardware, it’s time to discuss different strategies for developing software for Bluetooth solutions.

Arduino

Arduino provides a nice language to work with bits and bytes of Bluetooth as well as the microcontroller. Most of the identifiers can easily be coded in arrays of bytes. You can then attach Arduino functions to protocols from Arduino.

Let’s look at a code example for building a Bluetooth beacon first with a RedBear Duo:

// redbear_beacon.ino

static advParams_t adv_params;

// When advertising, use these 128 bits

static uint8_t adv_data[31]={0x02,0x01,0x06, 0x1A,0xFF,0x4C,0x00,

0x02,0x15,0x71,0x3d,0x00,0x00,0x50,0x3e,0x4c,0x75,0xba,0x94,0x31,

0x48,0xf1,0x8d,0x94,0x1e,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0xC5};

void setup()

{

Serial.begin(115200);

delay(5000);

Serial.println("IBeacon demo.");

ble.debugLogger(true);

ble.init();

adv_params.adv_int_min = 0x00A0;

adv_params.adv_int_max = 0x01A0;

adv_params.adv_type = 3;

adv_params.dir_addr_type = 0;

memset(adv_params.dir_addr,0,6);

adv_params.channel_map = 0x07;

adv_params.filter_policy = 0x00;

ble.setAdvParams(&adv_params);

ble.setAdvData(sizeof(adv_data), adv_data);

ble.startAdvertising();

Serial.println("BLE start advertising.");

}

void loop()

{

}

You can discover this beacon with a BLE central. In Node.js, you can use a library such as a command-line utility to start the scan process:

$ ibeacon iBeacon command line utility

Options: -h, --help Displays this message -v, --version Displayes the version -s, --scan Scan for iBeacons -b, --broadcast Broadcast as an iBeacon -u, --uuid Proximity UUID

To scan a RedBear Duo Bean, you can use:

$ ibeacon -scan

Starting scan

bleacon found: {"uuid":"713d0000503e4c75ba943148f18d941e",

"major":0,"minor":0,"measuredPower":-59,

"rssi":-71,"accuracy":2.134232534620913,

"proximity":"near"}

BLE Scanner and Parser

If you use a Raspberry Pi, Intel Edison, or Linux machine with the Bluez tool installed (see “Installing Bluez”), you can easily start scanning for BLE devices around you:

// ble_scan.js

var Scanner = require("ble-scanner");

var bleParser = require('ble-packet-parser');

var device = "scanner";

var callback = function(packet) {

// packet is an array with hex values

console.log( "Received Packet: " + packet);

json = bleParser(packet);

console.log(json);

}

// create new Scanner var bleScanner = new Scanner(device,callback);

You can then run this script:

# node ble_scan.js

And see something like:

HCICONFIG: succesfully brought up device scanner

HCIDUMP: cleared (code 0)

HCITOOL: cleared (code 0)

Received Packet: 04,3E,2B,02,01,03,01,A6,...

{ Event_Code: 62,

Subevent_Code: 2,

Packet_Length: 43,

Reports:

[ { eventType: 3,

addressType: 1,

address: '32:BF:50:C1:FB:A6',

data: [Object],

rssi: -77 } ] }

To make better sense of the low-level bytes of the BLE protocol, the Noble.js library (discussed in the following section) is more helpful.

Noble.js

With Noble.js, you can easily explore Bluetooth services from any computer that runs Node.js. The library comes with some helpful Getting Started documentation.

On an Edison, you must prepare the Bluetooth radio. The easiest way to make sure it is running is to switch it on and off:

# rfkill unblock bluetooth

Tessel 2 also uses the Noble.js library for its BLE getting started experience.

Noble allows you to discover, read, and write characteristics from peripherals.

Let’s first look at a simple scan for discovery of devices:

// simple_scan.js

var noble=require('noble');

// to keep track if the radio is powered or not

noble.on('stateChange', function(state) {

// radio must be powered on

if (state === 'poweredOn') {

noble.startScanning([], false);

}

else {

console.log('stop scanning');

noble.stopScanning();

}

});

noble.on('discover', function(peripheral) {

console.log('Found device with local name: ' +

peripheral.advertisement.localName);

console.log('advertising the following

service uuid\'s: ' + peripheral.advertisement.serviceUuids);

});

Next, you want to see the details of a service. You can do this with:

$ node scan_services.js poweredOn found device: eddie2 services: ec00

Bleno.js

In BLE, the “GATT server” serves the peripheral’s attributes. The Bleno library lets you use a computer to act as a GATT in order to easily test BLE peripherals.

On GitHub, the library is described as “a Node.js module for implementing BLE peripherals.” Similar to Noble.js, you must first start the radio and then wait for the connection:

// act_as_beacon.js

bleno.on('stateChange', function(state) {

console.log('on -> stateChange: ' + state);

// Start advertising

if (state === 'poweredOn') {

bleno.startAdvertising('Beacon', [customService.uuid]);

}

});

Example Project: Proximity Detection

In this section, we’ll use our new technical abilities (coupled with a library that helps you get information about the location of a device) to address a concrete human need: humans, physiologically, are bad at paying attention. Direct, concentrated focus is difficult to achieve in the face of even minor distraction, and compared to a computer we are not nearly as efficient at processing pure information. With this in mind, let’s now take a look at robots that assess your environment and adapt to you.

Note

“Ubiquitous computing” and “calm technology” are terms coined by Mark Weiser to discuss what technology of the future might look like. This area of research explores the concept of humans as parts of a whole technological system. This concept is presented with some prototype applications in Kelsey Breseman’s 2014 talk “Beyond the Screen: Humans as Input and Output”, where she urges technologists to “create technology you can forget about.”

The Nest thermostat and the August lock are two fairly prescient examples of passive technology—that is, technology that magically works even without your input into the system.

For example, with an August lock installed, your front door can magically open for you in response to discovery of your smart watch or smartphone’s BLE profile. Nest is meant to learn your habits and temperature preferences over time, and adapt itself into a system you can ignore.

In web programming, this type of responsiveness is familiar: an API call triggering an event in response to new information, or webhooks that republish a site based on a GitHub merge. How do we expand this type of system into physical space? It’s intuitive: physical actions already occur in response to events. By making web-connected sensors and actuators, we bridge the gap between two systems that are already event-driven.

The August Lock approach could be extended to turn lights/audio/heaters/anything on and off based on the presence of the user’s devices. For example, a database could have the device IDs for the smartphones of everyone in an office. The first employee to arrive at the office would trigger not just the lock but the power to the building’s systems, and it could shut off again after the last employee leaves the office.