Prepared Statements

Once a database connection is established, we can start to execute SQL

commands. This is normally done by preparing and stepping through

statements. Statements are held in

sqlite3_stmt data structures.

Statement Life Cycle

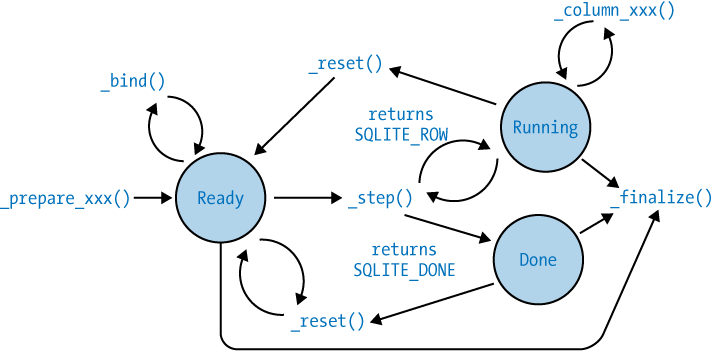

The life cycle of a prepared statement is a bit complex. Unlike database connections, which are typically opened, used for some period of time, and then closed, a statement can be in a number of different states. A statement might be prepared, but not run, or it might be in the middle of processing. Once a statement has run to completion, it can be reset and re-executed multiple times before eventually being finalized and released.

The life cycle of a typical sqlite3_stmt looks something like this

(in pseudo-code):

/* create a statement from an SQL string */

sqlite3_stmt *stmt = NULL;

sqlite3_prepare_v2( db, sql_str, sql_str_len, &stmt, NULL );

/* use the statement as many times as required */

while( ... )

{

/* bind any parameter values */

sqlite3_bind_xxx( stmt, param_idx, param_value... );

...

/* execute statement and step over each row of the result set */

while ( sqlite3_step( stmt ) == SQLITE_ROW )

{

/* extract column values from the current result row */

col_val = sqlite3_column_xxx( stmt, col_index );

...

}

/* reset the statement so it may be used again */

sqlite3_reset( stmt );

sqlite3_clear_bindings( stmt ); /* optional */

}

/* destroy and release the statement */

sqlite3_finalize( stmt );

stmt = NULL;The prepare process converts an SQL command string into a prepared statement. That statement can then have values bound to any statement parameters. The statement is then executed, or “stepped through.” In the case of a query, each step will make a new results row available for processing. The column values of the current row can then be extracted and processed. The statement is stepped through, row by row, until no more rows are available.

The statement can then be reset, allowing it to be

re-executed with a new set of bindings. Preparing a statement can be

somewhat costly, so it is a common practice to reuse statements as

much as possible. Finally, when the statement is no longer in use, the

sqlite3_stmt data structure

can be finalized. This releases any internal resources and frees the

sqlite3_stmt data structure,

effectively deleting the statement.

Prepare

To convert an SQL command string into a prepared statement, use one of the

sqlite3_prepare_xxx()

functions:

-

int sqlite3_prepare( sqlite3 *db, const char *sql_str, int sql_str_len, sqlite3_stmt **stmt, const char **tail )

int sqlite3_prepare16( sqlite3 *db, const void *sql_str, int sql_str_len, sqlite3_stmt **stmt, const void **tail ) It is strongly recommended that all new developments use the

_v2version of these functions.

-

int sqlite3_prepare_v2( sqlite3 *db, const char *sql_str, int sql_str_len, sqlite3_stmt **stmt, const char **tail )

int sqlite3_prepare16_v2( sqlite3 *db, const void *sql_str, int sql_str_len, sqlite3_stmt **stmt, const void **tail ) Converts an SQL command string into a prepared statement. The first parameter is a database connection. The second parameter is an SQL command encoded in a UTF-8 or UTF-16 string. The third parameter indicates the length of the command string in bytes. The fourth parameter is a reference to a statement pointer. This is used to pass back a pointer to the new

sqlite3_stmtstructure.The fifth parameter is a reference to a string (

charpointer). If the command string contains multiple SQL statements and this parameter is non-NULL, the pointer will be set to the start of the next statement in the command string.These

_v2calls take the exact same parameters as the original versions, but the internal representation of thesqlite3_stmtstructure that is created is somewhat different. This enables some extended and automatic error handling. These differences are discussed later in Result Codes and Error Codes.

If the length parameter is negative, the length

will be automatically computed by the prepare call. This requires that

the command string be properly null-terminated. If the length is

positive, it represents the maximum number of bytes that will be

parsed. For optimal performance, provide a null-terminated string and

pass a valid length value that includes the null-termination

character. If the SQL command string passed to sqlite3_prepare_xxx() consists of only

a single SQL statement, there is no need to terminate it with a

semicolon.

Once a statement has been prepared, but before it

is executed, you can bind parameter values to the statement. Statement

parameters allow you to insert a special token into the SQL command

string that represents an unspecified literal value. You can then bind

specific values to the parameter tokens before the statement is

executed. After execution, the statement can be reset and new

parameter values can be assigned. This allows you to prepare a

statement once and then re-execute it multiple times with different

parameter values. This is commonly used with commands, such as

INSERT, that have a common

structure but are repeatedly executed with different values.

Parameter binding is a somewhat in-depth topic, so we’ll get back to that in the next section. See Bound Parameters for more details.

Step

Preparing an SQL statement causes the command string to be parsed and converted into a set of byte-code commands. This byte-code is fed into SQLite’s Virtual Database Engine (VDBE) for execution. The translation is not a consistent one-to-one affair. Depending on the database structure (such as indexes), the query optimizer may generate very different VDBE command sequences for similar SQL commands. The size and flexibility of the SQLite library can be largely attributed to the VDBE architecture.

To execute the VDBE code, the function sqlite3_step() is called. This

function steps through the current VDBE command sequence until some

type of program break is encountered. This can happen when a new row

becomes available, or when the VDBE program reaches its end,

indicating that no more data is available.

In the case of a SELECT query, sqlite3_step() will return once for each row in the

result set. Each subsequent call to sqlite3_step() will continue execution of the

statement until the next row is available or the statement reaches its

end.

The function definition is quite simple:

-

int sqlite3_step( sqlite3_stmt *stmt ) Attempts to execute the provided prepared statement. If a result set row becomes available, the function will return with a value of

SQLITE_ROW. In that case, individual column values can be extracted with thesqlite3_column_xxx()functions. Additional rows can be returned by making further calls tosqlite3_step(). If the statement execution reaches its end, the codeSQLITE_DONEwill be returned. Once this happens,sqlite3_step()cannot be called again with this prepared statement until the statement is first reset usingsqlite3_reset().

If the first call to sqlite3_step() returns SQLITE_DONE, it means that the statement was

successfully run, but there was no result data to make available. This

is the typical case for most commands, other than SELECT. If sqlite3_step() is called repeatedly, a SELECT command will return SQLITE_ROW for each row of the result

set before finally returning SQLITE_DONE. If a SELECT command returns no rows, it will return

SQLITE_DONE on the first call

to sqlite3_step().

There are also some PRAGMA commands that will return a value. Even if the

return value is a simple scalar value, that value will be returned as

a one-row, one-column result set. This means that the first call to

sqlite3_step() will return

SQLITE_ROW, indicating result

data is available. Additionally, if

PRAGMA count_changes is set to

true, the INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE commands will return the number of rows they

modified as a one-row, one-column integer value.

Any time sqlite3_step() returns SQLITE_ROW, new row data is available for processing.

Row values can be inspected and

extracted from the statement using the sqlite3_column_xxx() functions, which we will

look at next. To resume execution of the statement, simply call

sqlite3_step() again. It is

common to call sqlite3_step() in a

loop, processing each row until SQLITE_DONE is returned.

Rows are returned as soon as they are computed. In

many cases, this spreads the processing costs out across all of the

calls to sqlite3_step(), and allows

the first row to be returned reasonably quickly. However, if the query

has a GROUP BY or ORDER BY clause, the statement may be

forced to first gather all of the rows within the result set before it

is able to complete the final processing. In these cases, it may take

a considerable time for the first row to become available, but

subsequent rows should be returned very very quickly.

Result Columns

Any time sqlite3_step() returns the code SQLITE_ROW, a

new result set row is available within the statement. You can use the

sqlite3_column_xxx()

functions to inspect and extract the column values from this row. Many

of these functions require a column index parameter (cidx). Like C arrays, the first column

in a result set always has an index of zero, starting from the

left.

-

int sqlite3_column_count( sqlite3_stmt *stmt ) Returns the number of columns in the statement result. If the statement does not return values, a count of zero will be returned. Valid column indexes are zero through the count minus one. (

Ncolumns have the indexes0throughN-1).-

const char* sqlite3_column_name( sqlite3_stmt *stmt, int cidx )

const void* sqlite3_column_name16( sqlite3_stmt *stmt, int cidx ) Returns the name of the specified column as a UTF-8 or UTF-16 encoded string. The returned string is the name provided by the

ASclause within theSELECTheader. For example, this function would returnperson_idfor column zero of the SQL statementSELECT pid AS person_id,.... If noASexpression was given, the name is technically undefined and may change from one version of SQLite to another. This is especially true of columns that consist of an expression.The returned pointers will remain valid until one of these functions is called again on the same column index, or until the statement is destroyed with

sqlite3_finalize(). The pointers will remain valid (and unmodified) across calls tosqlite3_step()andsqlite3_reset(), as column names do not change from one execution to the next. These pointers should not be passed tosqlite3_free().-

int sqlite3_column_type( sqlite3_stmt *stmt, int cidx ) Returns the native type (storage class) of the value found in the specified column. Valid return codes can be

SQLITE_INTEGER,SQLITE_FLOAT,SQLITE_TEXT,SQLITE_BLOB, orSQLITE_NULL. To get the correct native datatype, this function should be called before any attempt is made to extract the data.This function returns the type of the actual value found in the current row. Because SQLite allows different types to be stored in the same column, the type returned for a specific column index may vary from row to row. This is also how you detect the presence of a NULL.

These sqlite3_column_xxx() functions allow your code to get

an idea of what the available row looks like. Once you’ve figured out

the correct value type, you can extract the value with one of these

typed sqlite3_column_xxx()

functions. All of these functions take the same parameters: a

statement pointer and a column index.

-

const void* sqlite3_column_blob( sqlite_stmt *stmt, int cidx ) Returns a pointer to the BLOB value from the given column. The pointer may be invalid if the BLOB has a length of zero bytes. The pointer may also be NULL if a type conversion was required.

-

double sqlite3_column_double( sqlite_stmt *stmt, int cidx ) Returns a 64-bit floating-point value from the given column.

-

int sqlite3_column_int( sqlite_stmt *stmt, int cidx ) Returns a 32-bit signed integer from the given column. The value will be truncated (without warning) if the column contains an integer value that cannot be represented in 32 bits.

-

sqlite3_int64 sqlite3_column_int64( sqlite_stmt *stmt, int cidx ) -

const unsigned char* sqlite3_column_text( sqlite_stmt *stmt, int cidx )

const void* sqlite3_column_text16( sqlite_stmt *stmt, int cidx ) Returns a pointer to a UTF-8 or UTF-16 encoded string from the given column. The string will always be null-terminated, even if it is an empty string. Note that the returned

charpointer is unsigned and will likely require a cast. The pointer may also be NULL if a type conversion was required.-

sqlite3_value* sqlite3_column_value( sqlite_stmt *stmt, int cidx ) Returns a pointer to an unprotected

sqlite3_valuestructure. Unprotectedsqlite3_valuestructures cannot safely undergo type conversion, so you should not attempt to extract a primitive value from this structure using thesqlite3_value_xxx()functions. If you want a primitive value, you should use one of the othersqlite3_column_xxx()functions. The only safe use for the returned pointer is to callsqlite3_bind_value()orsqlite3_result_value(). The first is used to bind the value to another prepared statement, while the second is used to return a value in a user-defined SQL function (see Binding Values, or Returning Results and Errors).

There is no sqlite3_column_null() function. There is no need for

one. If the native datatype is NULL, there is no additional value or

state information to extract.

Any pointers returned by these functions become

invalid if another call to any sqlite3_column_xxx() function is made using the same

column index, or when sqlite3_step() is next called. Pointers will also

become invalid if the statement is reset or finalized. SQLite will

take care of all the memory management associated with these

pointers.

If you request a datatype that is different from the native value, SQLite will attempt to convert the value. Table 7-1 describes the conversion rules used by SQLite.

| Original type | Requested type | Converted value |

| NULL | Integer | 0 |

| NULL | Float | 0.0 |

| NULL | Text | NULL pointer |

| NULL | BLOB | NULL pointer |

| Integer | Float | Converted float |

| Integer | Text | ASCII number |

| Integer | BLOB | Same as text |

| Float | Integer | Rounds towards zero |

| Float | Text | ASCII number |

| Float | BLOB | Same as text |

| Text | Integer | Internal atoi() |

| Text | Float | Internal atof() |

| Text | BLOB | No change |

| BLOB | Integer | Converts to text, atoi() |

| BLOB | Float | Converts to text, atof() |

| BLOB | Text | Adds terminator |

Some conversions are

done in place, which can cause subsequent calls to sqlite3_column_type() to

return undefined results. That’s why it is important to call sqlite3_column_type() before trying to extract a value,

unless you already know exactly what datatype you want.

Although numeric values are returned directly, text and BLOB values are returned in a buffer. To determine how large that buffer is, you need to ask for the byte count. That can be done with one of these two functions.

-

int sqlite3_column_bytes( sqlite3_stmt *stmt, int cidx ) Returns the number of bytes in a BLOB or in a UTF-8 encoded text value. If returning the size of a text value, the size will include the terminator.

-

int sqlite3_column_bytes16( sqlite3_stmt *stmt, int cidx ) Returns the number of bytes in a UTF-16 encoded text value, including the terminator.

Be aware that these functions can cause a data

conversion in text values. That conversion can invalidate any

previously returned pointer. For example, if you call sqlite3_column_text() to get a pointer to a UTF-8 encoded string,

and then call sqlite3_column_bytes16() on the same column, the

internal column value will be converted from a UTF-8 encoded string to

a UTF-16 encoded string. This will invalidate the character pointer

that was originally returned by sqlite3_column_text().

Similarly, if you first call sqlite3_column_bytes16() to get the

size of UTF-16 encoded string, and then call sqlite3_column_text(), the internal value will be

converted to a UTF-8 string before a string pointer is returned. That

will invalidate the length value that was originally returned.

The easiest way to avoid problems is to extract the datatype you want and then call the matching bytes function to find out how large the buffer is. Here are examples of safe call sequences:

/* correctly extract a blob */ buf_ptr = sqlite3_column_blob( stmt, n ); buf_len = sqlite3_column_bytes( stmt, n ); /* correctly extract a UTF-8 encoded string */ buf_ptr = sqlite3_column_text( stmt, n ); buf_len = sqlite3_column_bytes( stmt, n ); /* correctly extract a UTF-16 encoded string */ buf_ptr = sqlite3_column_text16( stmt, n ); buf_len = sqlite3_column_bytes16( stmt, n );

By matching the correct bytes function for your desired datatype, you can avoid any type conversions keeping both the pointer and length valid and correct.

You should always use sqlite3_column_bytes() to determine the size

of a BLOB.

Reset and Finalize

When a call to sqlite3_step() returns SQLITE_DONE, the statement has successfully finished execution. At that

point, there is nothing further you can do with the statement. If you

want to use the statement again, it must first be reset.

The function sqlite3_reset() can be called any time after sqlite3_step() is called. It is valid

to call sqlite3_reset() before a

statement is finished executing (that is, before sqlite3_step() returns SQLITE_DONE or an error indicator).

You can’t cancel a running sqlite3_step() call this way, but you can

short-circuit the return of additional SQLITE_ROW values.

For example, if you only want the first six rows of a result set, it

is perfectly valid to call sqlite3_step() only six times and then reset the

statement, even if sqlite3_step()

would continue to return SQLITE_ROW.

The function sqlite3_reset() simply resets a statement, it does

not release it. To destroy a prepared statement and release its

memory, the statement must be finalized.

The function sqlite3_finalize()

can be called at any time on any statement that was

successfully prepared. All of the prepared statements associated with

a database connection must be finalized before the database connection

can be closed.

Although both of these functions can return errors, they always

perform their function. Any error that is returned was generated by

the last call to sqlite3_step().

See Result Codes and Error Codes for more details.

It is a good idea to reset or finalize a statement as soon as you are

done using it. A call to sqlite3_reset() or sqlite3_finalize() ensures the statement will release

any locks it might be holding, and frees any resources associated with

the prior statement execution. If an application keeps statements

around for an extended period of time, they should be kept in a reset

state, ready to be bound and executed.

Statement Transitions

Prepared statements have a significant amount of state. In addition to the currently bound parameter values and other details, every prepared statement is always in one of three major states. The first is the “ready” state. Any freshly prepared or reset statement will be “ready.” This indicates that the statement is ready to execute, but hasn’t been started. The second state is “running,” indicating that a statement has started to execute, but hasn’t yet finished. The final state is “done,” which indicates the statement has completed executing.

Knowing the current state of a statement is important. Although some

API functions can be called at any time (like sqlite3_reset()), other API functions can only be

called when a statement is in a specific state. For example, the

sqlite3_bind_xxx() functions

can only be called when a statement is in its “ready” state. Figure 7-1 shows the different states

and how a statement transitions from one state to another.

There is no way to query the current state of a statement. Transitions between states are normally controlled by the design and flow of the application.

Examples

Here are two examples of using prepared statements. The first example

executes a CREATE TABLE

statement by first preparing the SQL string and then

calling sqlite3_step() to execute

the statement:

sqlite3_stmt *stmt = NULL;

/* ... open database ... */

rc = sqlite3_prepare_v2( db, "CREATE TABLE tbl ( str TEXT )", -1, &stmt, NULL );

if ( rc != SQLITE_OK) exit( -1 );

rc = sqlite3_step( stmt );

if ( rc != SQLITE_DONE ) exit ( -1 );

sqlite3_finalize( stmt );

/* ... close database ... */The CREATE TABLE statement is a DDL

command that does not return any type of value and only needs to be

“stepped” once to fully execute the command. Remember to reset or

finalize statements as soon as they’re finished executing. Also

remember that all statements associated with a database connection

must be fully finalized before the connection can be closed.

This second example is a bit more complex. This code performs a

SELECT and loops over

sqlite3_step() extracting all

of the rows in the table. Each value is displayed as it is

extracted:

const char *data = NULL;

sqlite3_stmt *stmt = NULL;

/* ... open database ... */

rc = sqlite3_prepare_v2( db, "SELECT str FROM tbl ORDER BY 1", -1, &stmt, NULL );

if ( rc != SQLITE_OK) exit( -1 );

while( sqlite3_step( stmt ) == SQLITE_ROW ) {

data = (const char*)sqlite3_column_text( stmt, 0 );

printf( "%s\n", data ? data : "[NULL]" );

}

sqlite3_finalize( stmt );

/* ... close database ... */This example does not check the type of the column value. Since the

value will be displayed as a string, the code depends on SQLite’s

internal conversion process and always requests a text value. The only

tricky bit is that the string pointer may be NULL, so we need to be

prepared to deal with that in the printf()

statement.