Common Structures and Relationships

Database design has a small number of design structures and relationships that act as basic building blocks. Once you master how to use them and how to manipulate them, you can use these building blocks to build much larger and more complex data representations.

One-to-One Relationships

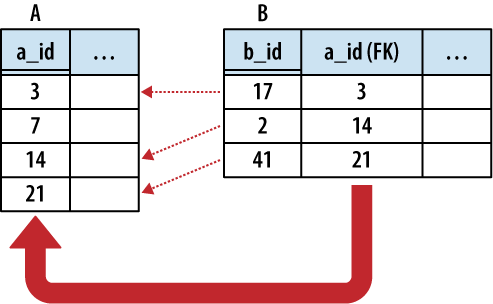

The most basic kind of inter-table relationship is the one-to-one relationship. As you can guess, this type of relationship establishes a reference from a single row in one table to a single row in another table. Most commonly, one-to-one relationships are represented by having a foreign key in one table reference a primary key in another table. If the foreign key column is made unique, only one reference will be allowed. As Figure 6-3 illustrates, a unique foreign key creates a one-to-one relationship between the rows of the two tables.

In the strictest sense, a foreign key relationship is a one-to-(zero or one) relationship. When two tables are involved in a one-to-one relationship, there is nothing to enforce that every primary key has an incoming reference from a foreign key. For that matter, if the foreign key allows NULLs, there may be unassigned foreign keys as well.

One-to-one relationships are commonly used to create detail tables. As the name implies, a detail table typically holds details that are linked to the records in a more prominent table. Detail tables can be used to hold data that is only relevant to a small subsection of the database application. Breaking the detail data apart from the main tables allows different sections of the database design to evolve and grow much more independently.

Detail tables can also be helpful when extended

data only applies to a limited number of records. For example, a

website might have a sales_items

table that lists common information (price, inventory, weight, etc.)

for all available items. Type-specific data can then be held in detail

tables, such as cd_info for CDs

(artist name, album name, etc.) or dvd_info (directors, studio, etc.) for DVDs. Although

the sales_items table would have a

unique one-to-one relationship with every type-specific info table,

each individual row in the sales_item table would be referenced by only one type

of detail table.

One-to-one relationships can also be used to

isolate very large data elements, such as BLOBs. Consider an employee database that contains an

image of each employee. Due to the data storage and I/O overhead, it

might be unwise to include a photo

column directly in the employee

table, but it is easy to create a photo table that references the

employee table. Consider these two tables:

CREATE TABLE employee (

employee_id INTEGER NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

name TEXT NOT NULL

/* ...etc... */

);

CREATE TABLE employee_photo (

employee_id INTEGER NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY

REFERENCES employee,

photo_data BLOB

/* ...etc... */

);This example is a bit unique, because the employee_photo.employee_id column is

both the primary key for the employee_photo table, as well as a foreign key to the

employee table. Since we want

a one-to-one relationship, it makes sense to just pair up primary

keys. Because this foreign key does not allow NULL keys, every

employee_photo row must be

matched to a specific employee row.

The database does not guarantee that every employee will have a matching employee_photo, however.

One-to-Many Relationships

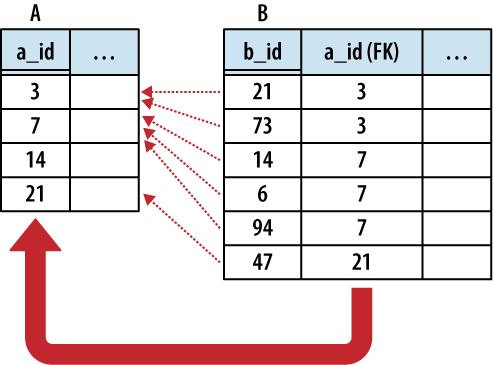

One-to-many relationships establish a link between a single row in one table to multiple rows in another table. This is done by expanding a one-to-one relationship, allowing one side to contain duplicate keys. One-to-many relationships are often used to associate lists or arrays of items back to a single row. For example, multiple shipping addresses can be linked to a single account. Unless otherwise specified, “many” usually means “zero or more.”

The only difference between a one-to-one relationship and a one-to-many relationship is that the one-to-many relationship allows for duplicate foreign key values. This allows multiple rows in one table (the many table) to refer back to a single row in another table (the One table). In building a one-to-many relationship, the foreign key must always be on the many side.

Figure 6-4 illustrates the relationship in more detail.

Any time you find yourself wondering how to stuff an array or list into the column of a table, the solution is to separate the array elements out into their own table and establish a one-to-many relationship.

The same is true any time you start to contemplate

sets of columns, such as item0,

item1, item2, etc., that are all designed to

hold instances of the same type of value. Such designs have inherent

limits, and the insert, update, and removal process becomes quite

complex. It is much easier to just break the data out into its own

table and establish a proper relationship.

One example of a one-to-many relationship is music albums, and the songs they contain. Each album has a list of songs associated with that album. For example:

CREATE TABLE albums (

album_id INTEGER NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

album_name TEXT );

CREATE TABLE tracks (

track_id INTEGER NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

track_name TEXT,

track_number INTEGER,

track_length INTEGER, -- in seconds

album_id INTEGER NOT NULL REFERENCES albums );Each album and track has a unique ID. Each track also has a foreign key reference back to its album. Consider:

INSERT INTO albums VALUES ( 1, "The Indigo Album" ); INSERT INTO tracks VALUES ( 1, "Metal Onion", 1, 137, 1 ); INSERT INTO tracks VALUES ( 2, "Smooth Snake", 2, 212, 1 ); INSERT INTO tracks VALUES ( 3, "Turn A", 3, 255, 1 ); INSERT INTO albums VALUES ( 2, "Morning Jazz" ); INSERT INTO tracks VALUES ( 4, "In the Bed", 1, 214, 2 ); INSERT INTO tracks VALUES ( 5, "Water All Around", 2, 194, 2 ); INSERT INTO tracks VALUES ( 6, "Time Soars", 3, 265, 2 ); INSERT INTO tracks VALUES ( 7, "Liquid Awareness", 4, 175, 2 );

To get a simple list of tracks and their associated album, we just join the tables back together. We can also sort by both album name and track number:

sqlite>SELECT album_name, track_name, track_number...>FROM albums JOIN tracks USING ( album_id )...>ORDER BY album_name, track_number;album_name track_name track_number ------------ ---------- ------------ Morning Jazz In the Bed 1 Morning Jazz Water All 2 Morning Jazz Time Soars 3 Morning Jazz Liquid Awa 4 The Indigo A Metal Onio 1 The Indigo A Smooth Sna 2 The Indigo A Turn A 3

We can also manipulate the track groupings:

sqlite>SELECT album_name, sum( track_length ) AS runtime, count(*) AS tracks...>FROM albums JOIN tracks USING ( album_id )...>GROUP BY album_id;album_name runtime tracks ---------------- ---------- ---------- The Indigo Album 604 3 Morning Jazz 848 4

This query groups the tracks based off their album, and then aggregates the track data together.

Many-to-Many Relationships

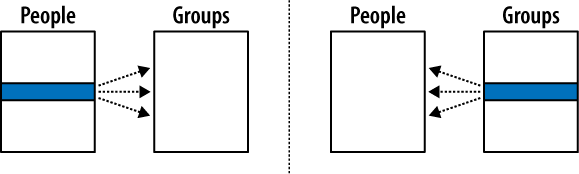

The next step is the many-to-many relationship. A many-to-many relationship associates one row in the first table to many rows in the second table while simultaneously allowing individual rows in the second table to be linked to multiple rows in the first table. In a sense, a many-to-many relationship is really two one-to-many relationships built across each other.

Figure 6-5 shows the classic many-to-many example of people and groups. One person can belong to many different groups, while each group is made up of many different people. Common operations are to find all the groups a person belongs to, or to find all the people in a group.

Many-to-many relationships are a bit more complex than other relationships. Although the tables have a many-to-many relationship with each other, the entries in both tables must remain unique. We cannot duplicate either person rows or group rows for the purpose of matching keys. This is a problem, since each foreign key can only reference one row. This makes it impossible for a foreign key of one table (such as a group) to refer to multiple rows of another table (such as people).

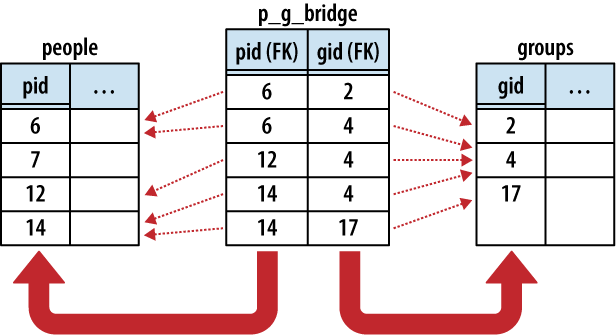

To solve this, we go back to the advice from before: if you need to add a list to a row, break out that list into its own table and establish a one-to-many relationship with the new table. You cannot directly represent a many-to-many relationship with only two tables, but you can take a pair of one-to-many relationships and link them together. The link requires a small table, known as a link table, or bridge table, that sits between the two many tables. Each many-to-many relationship requires a unique bridge table.

In its most basic form, the bridge table consists of nothing but two foreign keys—one for each of the tables it is linking together. Each row of the bridge table links one row in the first many table to one row in the second many table. In our People-to-Groups example, the link table defines a membership of one person in one group. This is illustrated in Figure 6-6.

The logical representation of a many-to-many relationship is actually a one-to-many-to-one relationship, with the bridge table (acting as a record of membership) in the middle. Each person has a one-to-many relationship with memberships, just as groups have a one-to-many relationship with memberships. In addition to binding the two tables together, the bridge table can also hold additional information about the membership itself, such as a first-joined date or an expiration date.

Here are three tables. The people and groups table are obvious enough. The p_g_bridge table acts as the bridge

table between the people table and

groups table. The two columns

are both foreign key references, one to people and one to groups. Establishing a primary key across both

foreign key columns ensures the memberships remain unique:

CREATE TABLE people ( pid INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, name TEXT, ... );

CREATE TABLE groups ( gid INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, name TEXT, ... );

CREATE TABLE p_g_bridge(

pid INTEGER NOT NULL REFERENCES people,

gid INTEGER NOT NULL REFERENCES groups,

PRIMARY KEY ( pid, gid )

);This query will list all the groups that a person belongs to:

SELECT groups.name AS group_name

FROM people JOIN p_g_bridge USING ( pid ) JOIN groups USING ( gid )

WHERE people.name = search_person_name;The query simply links people to groups

using the bridge table, and then filters out the appropriate

rows.

We don’t always need all three tables. This query

counts all the members of a group without utilizing the people table:

SELECT name AS group_name, count(*) AS members FROM groups JOIN p_g_bridge USING ( gid ) GROUP BY gid;

There are many other queries we can do, like finding all the groups that have no members:

SELECT name AS group_name FROM groups LEFT OUTER JOIN p_g_bridge USING ( gid ) WHERE pid IS NULL;

This query performs an outer join from the

groups table to the p_g_bridge table. Any unmatched group

rows will be padded out with a NULL in the p_g_bridge.pid column. Since this column is marked

NOT NULL, we know the only

possible way for a row to be NULL in that column is from the outer

join, meaning the row is unmatched to any memberships. A very similar

query could be used to find any people that have no memberships.

Hierarchies and Trees

Hierarchies and other tree-style data relationships are common and frequently show up in database design. Modeling one in a database can be a challenge because you tend to ask different types of questions when dealing with hierarchies.

Common tree operations include finding all the sub-nodes under a given node, or querying the depth of a given node. These operations have an inherent recursion in them—a concept that SQL doesn’t support. This can lead to clumsy queries or complex representations.

There are two common methods for representing a tree relation using database tables. The first is the adjacency model, which uses a simple representation that is easy to modify but complex to query. The other common representation is the nested set, which allows relatively simple queries, but at the cost of a more complex representation that can be expensive to modify.

Adjacency Model

A tree is basically a series of nodes that have a one-to-many relationship between the parents and the children. We already know how to define a one-to-many relationship: give each child a foreign key that points to the primary key of the parent. The only trick is that the same table is sitting on both sides of the relationship.

For example, here is a basic adjacency model table:

CREATE TABLE tree (

node INTEGER NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

name TEXT,

parent INTEGER REFERENCES tree );Each node in the tree will have a unique node identifier. Each node will also have a reference to its parent node. The root of the tree can simply have a NULL parent reference. This allows multiple trees to be stored in the same table, as multiple nodes can be defined as a root node of different trees.

If we want to represent this tree:

A

A.1

A.1.a

A.2

A.2.a

A.2.b

A.3We would use the following data:

INSERT INTO tree VALUES ( 1, 'A', NULL ); INSERT INTO tree VALUES ( 2, 'A.1', 1 ); INSERT INTO tree VALUES ( 3, 'A.1.a', 2 ); INSERT INTO tree VALUES ( 4, 'A.2', 1 ); INSERT INTO tree VALUES ( 5, 'A.2.a', 4 ); INSERT INTO tree VALUES ( 6, 'A.2.b', 4 ); INSERT INTO tree VALUES ( 7, 'A.3', 1 );

The following query will give a list of nodes and parents by joining the tree table to itself:

sqlite>SELECT n.name AS node, p.name AS parent...>FROM tree AS n JOIN tree AS p ON n.parent = p.node;node parent ---------- ---------- A.1 A A.1.a A.1 A.2 A A.2.a A.2 A.2.b A.2 A.3 A

Inserting or removing nodes is fairly straightforward, as is moving subtrees around to different parents.

What isn’t easy are tree-centric operations, like counting all of the nodes in a subtree, or computing the depth of a specific node (often used for output formatting). You can do limited traversals (like finding a grand-parent) by joining the tree table to itself multiple times, but you cannot write a single query that can compute an answer to these types of questions on a tree of arbitrary size. The only choice is to write application routines that loop over different levels in the tree, computing the answers you seek.

Overall, the adjacency model is easy to understand, and the trees are easy to modify. The model is based on foreign keys, and can take full advantage of the database’s built-in referential integrity. The major disadvantage is that many types of common data queries require the application code to loop over several individual database queries and assist in calculating answers.

Nested set

As the name implies, the nested set representation depends on nesting groups of nodes inside other groups. Rather than representing some type of parent-child relationship, each node holds bounding data about the full subtree underneath it. With some clever math, this allows us to query all kinds of information about a node.

A nested set table might look like this:

CREATE TABLE nest (

name TEXT,

lower INTEGER NOT NULL UNIQUE,

upper INTEGER NOT NULL UNIQUE,

CHECK ( lower < upper ) );The nested set can be visualized by converting the tree structure into a parenthetical representation. We then count the parentheses and record the upper and lower bound of each nested set. The index numbers can also be calculated with a depth-first tree traversal, where the lower bound is a pre-visit count and the upper bound is a post-visit count.

A( A.1( A.1.a( ) ), A.2( A.2.a( ), A.2.b( ) ), A.3( ) ) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

INSERT INTO nest VALUES ( 'A', 1, 14 ); INSERT INTO nest VALUES ( 'A.1', 2, 5 ); INSERT INTO nest VALUES ( 'A.1.a', 3, 4 ); INSERT INTO nest VALUES ( 'A.2', 6, 11 ); INSERT INTO nest VALUES ( 'A.2.a', 7, 8 ); INSERT INTO nest VALUES ( 'A.2.b', 9, 10 ); INSERT INTO nest VALUES ( 'A.3', 12, 13 );

This might not look that useful, but it allows a number of different queries. For example, if you want to find all the leaf nodes (nodes without children) just look for nodes that have an upper and lower value that are next to each other:

SELECT name FROM nest WHERE lower + 1 = upper;

You can find the depth of a node by counting all of its ancestors:

sqlite>SELECT n.name AS name, count(*) AS depth...>FROM nest AS n JOIN nest AS p...>ON p.lower <= n.lower AND p.upper >= n.upper...>GROUP BY n.name;name depth ---------- ---------- A 1 A.1 2 A.1.a 3 A.2 2 A.2.a 3 A.2.b 3 A.3 2

There are many other queries that match patterns or differences in the upper and lower bounds.

Nested sets are very efficient at calculating many types of queries, but they are expensive to change. For the math to work correctly, there can’t be any gaps in the numbering sequence. This means that any insert or delete requires renumbering a significant number of entries in the table. This isn’t bad for something with a few dozen nodes, but it can quickly prove impractical for a tree with hundreds of nodes.

Additionally, because nested sets aren’t based off any kind of key reference, the database can’t help enforce the correctness of the tree structure. This leaves database integrity and correctness in the hands of the application—something that is normally avoided.

More information

This is just a brief overview of how to represent tree relationships. If you need to implement a tree, I suggest you do a few web searches on adjacency model or nested set. Many of the larger SQL books mentioned in Wrap-up also have sections on tree and hierarchies.