Advanced Techniques

Beyond the basic SELECT syntax, there are a few advanced techniques for

expressing more complex queries.

Subqueries

The SELECT

command provides a great deal of flexibility, but there are times

when a single SELECT command cannot

fully express a query. To help with these situations, SQL supports

subqueries. A subquery is nothing more

than a SELECT statement that is

embedded in another SELECT

statement. Subqueries are also known as sub-selects.

Subqueries are most commonly found in the FROM clause, where they act as a

computed source table. This type of subquery can return any number of

rows or columns, and is similar to creating a view or running the

query, recording the results into a temporary table, and then

referencing that table in the main query. The main advantage of using

an in-line subquery is that the query optimizer is able to merge the

subquery into the main SELECT

statement and look at the whole problem, often leading to a more

efficient query plan.

To use a subquery in the FROM clause, simply enclose it in parentheses. The following two statements will produce the same output:

SELECT * FROM TblA AS a JOIN TblB AS b; SELECT * FROM TblA AS a JOIN (SELECT * FROM TblB) AS b;

Subqueries can show up in other places, including

general expressions used in any SQL command. The

EXISTS and IN operators both utilize subqueries. In fact, you

can use a subquery any place an expression expects a list of literal

values (a subquery cannot be used to generate a list of identifiers,

however). See Appendix D for more details on SQL

expressions.

Compound SELECT Statements

In addition to subqueries, multiple SELECT

statements can be combined together to form a compound

SELECT.

Compound SELECTs use set operators

on the rows generated by a series of SELECT statements.

In order to combine correctly, each SELECT statement must generate the

same number of columns. The column names from the first SELECT statement will be used for the

overall result. Only the last SELECT statement can have an ORDER BY, LIMIT or

OFFSET clause, which get

applied to the full compound result table. The syntax for a compound

SELECT looks like

this:

SELECT ... FROM ... WHERE ... GROUP BY ... HAVING ...

compound_operator

SELECT ... FROM ... WHERE ... GROUP BY ... HAVING ...

[...]

ORDER BY ... LIMIT ... OFFSET ...Multiple compound operators can be used to include

additional SELECT

statements.

-

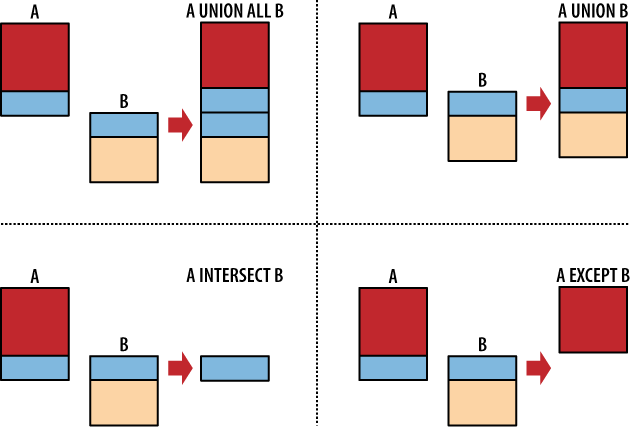

UNION ALL The

UNION ALLoperator concatenates all of the rows returned by eachSELECTinto one large table. If the twoSELECTblocks generate N and M rows, respectively, the resulting table will have N+M rows.-

UNION The

UNIONoperator is very similar to theUNION ALLoperator, but it will eliminate any duplicate rows, including duplicates that came from the sameSELECTblock. If the twoSELECTblocks generate N and M rows, respectively, the resulting table can have anywhere from 1 to N+M rows.-

INTERSECT The

INTERSECToperator will return one instance of any row that is found (one or more times) in bothSELECTblocks. If the twoSELECTblocks generate N and M rows, respectively, the resulting table can have anywhere from 0 toMIN(N,M)rows.-

EXCEPT The

EXCEPToperator will return all of the rows in the firstSELECTblock that are not found in the secondSELECTblock. It is essentially a subtraction operator. If there are duplicate rows in the first block, they will all be eliminated by a single, matching row in the second block. If the twoSELECTblocks generate N and M rows, respectively, the resulting table can have anywhere from 0 to N rows.

SQLite supports the UNION, UNION ALL,

INTERSECT, and EXCEPT compound operators. Figure 5-8 shows the result of each

operator.

Once all the compound operators have been

combined, any trailing ORDER BY,

LIMIT, and OFFSET is applied to the final result

table. In the case of compound SELECT statements, the expressions present in any

ORDER BY clause must be

exactly match one of the result columns, or use a column index.

Alternate JOIN Notation

There are two styles of join notation. The style shown earlier in this chapter is

known as

explicit join notation. It is named such

because it uses the keyword JOIN to

explicitly describe how each table is joined to the next. The explicit

join notation is also known as

ANSI join notation, as it was introduced when

SQL went through the standardization process.

The older, original join notation is known

as

implicit join notation. Using this notation,

the FROM clause is simply a

comma-separated list of tables. The tables in the list are combined

using a Cartesian product and the relevant rows are extracted with

additional WHERE conditions. In

effect, it degrades every join to a CROSS

JOIN and then moves the join conditions out of

the

FROM clause and into the WHERE clause.

This first statement uses the explicit join notation we learned earlier in the chapter:

SELECT ... FROM employee JOIN resource ON ( employee.eid = resource.eid ) WHERE ...

This is the same statement written with the implicit join notation:

SELECT ... FROM employee, resource WHERE employee.eid = resource.eid AND ...

There is no performance difference between the two notations: it is purely a matter of syntax.

In general, the explicit notion (the first one)

has become the standard way of doing things. Most people find the

explicit notation easier to read, making the intent of the query more

transparent and easier to understand. I’ve always felt the explicit

notation is a bit cleaner, as it puts the complete join specification

into the FROM clause, leaving the

WHERE clause free for

query-specific filters. Using the explicit notation, the FROM clause (and the FROM clause alone) fully and

independently specifies what you’re selecting “from.”

The explicit notation also lets you be much more

specific about the type and order of each JOIN. In SQLite, you must use the explicit notation

if you want an OUTER JOIN—the

implicit notation can only be used to indicate a CROSS JOIN or INNER JOIN.

If you’re learning SQL for the first time, I would strongly suggest you become comfortable with the explicit notation. Just be aware that there is a great deal of SQL code out there (including older books and tutorials) using the older, implicit notation.