The SELECT Pipeline

The SELECT syntax

tries to represent a generic framework that is capable of expressing

many different types of queries. To achieve this, SELECT has a large number of optional clauses, each with

its own set of options and formats.

The most general format of a standalone SQLite SELECT statement looks like this:

SELECT [DISTINCT]select_headingFROMsource_tablesWHEREfilter_expressionGROUP BYgrouping_expressionsHAVINGfilter_expressionORDER BYordering_expressionsLIMITcountOFFSETcount

Every SELECT command

must have a select heading, which defines the returned values. Each

additional line (FROM, WHERE, GROUP

BY, etc.) represents an optional clause.

Each clause represents a step in the SELECT pipeline. Conceptually, the result of

a SELECT statement is calculated by

generating a working table, and then passing that table through the

pipeline. Each step takes the working table as input, performs a specific

operation or manipulation, and passes the modified table on to the next

step. Manipulations operate the whole working table, similar to vector or

matrix operations.

Practically, the database engine takes a few shortcuts and makes plenty of optimizations when processing a query, but the end result should always match what you would get from independently going through each step, one at a time.

The clauses in a SELECT statement are not evaluated in the same order they

are written. Rather, their evaluation order looks something like

this:

Designates one or more source tables and combines them together into one large working table.

Groups sets of rows in the working table based off similar values.

Defines the result set columns and (if applicable) grouping aggregates.

Filters specific rows out of the grouped table. Requires a

GROUP BY.Skips over rows at the beginning of the result set. Requires a

LIMIT.

No matter how large or complex a SELECT statement may be, they all follow

this basic pattern. To understand how any query works, break it down and

look at each individual step. Make sure you understand what the working

table looks like before each step, how that step manipulates and modifies

the table, and what the working table looks like when it is passed to the

next step.

FROM Clause

The FROM clause

takes one or more source tables from the database and

combines them into one large table. Source tables are usually named

tables from the database, but they can also be views or subqueries

(see Subqueries for more details on

subqueries).

Tables are combined using the JOIN operator. Each JOIN combines two tables into a larger

table. Three or more tables can be joined together by stringing a

series of JOIN operators together.

JOIN operators are evaluated

left-to-right, but there are several different types of joins, and not

all of them are commutative or associative. This makes the ordering

and grouping very important. If necessary, parentheses can be used to

group the joins correctly.

Joins are the most important and most powerful database operator. Joins are the only way to bring together information stored in different tables. As we’ll see in the next chapter, nearly all of database design theory assumes the user is comfortable with joins. If you can master joins, you’ll be well on your way to mastering relational databases.

SQL defines three major types of joins: the

CROSS JOIN, the INNER JOIN, and the OUTER JOIN.

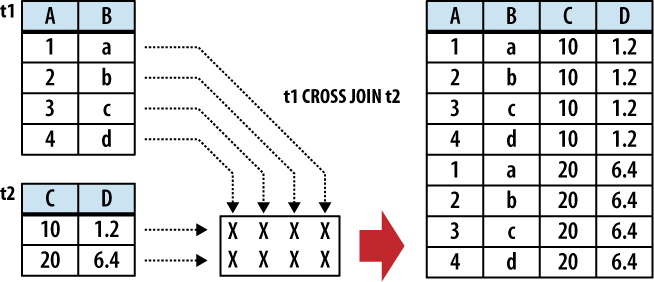

CROSS JOIN

A CROSS

JOIN matches every row of the first table with every row of the

second table. If the input tables have x

and y columns, respectively, the resulting

table will have x+y columns. If the input

tables have n and m

rows, respectively, the resulting table will have

n·m rows. In mathematics, a CROSS JOIN is known as a

Cartesian product.

The syntax for a CROSS JOIN is quite simple:

SELECT ... FROM t1 CROSS JOIN t2 ...

Figure 5-1 shows

how a CROSS JOIN is

calculated.

Because CROSS

JOINs have the potential to generate extremely

large tables, care must be taken to only use them when

appropriate.

INNER JOIN

An INNER

JOIN is very similar to a CROSS

JOIN, but it has a built-in condition that is

used to limit the number of rows in the resulting table. The

conditional is normally used to pair up or match rows from the

two source tables. An INNER

JOIN without any type of conditional expression

(or one that always evaluates to true) will result in a CROSS JOIN. If the input tables

have x and y columns,

respectively, the resulting table will have no more than

x+y columns (in some cases, it can

have fewer). If the input tables have n and

m rows, respectively, the resulting

table can have anywhere from zero to n·m

rows, depending on the condition. An INNER JOIN is the most common type of join, and

is the default type of join. This makes the INNER keyword optional.

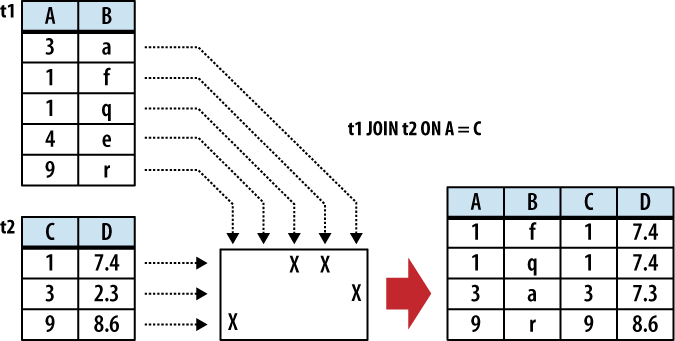

There are three primary ways to specify the

conditional. The first is with an ON expression. This provides a simple

expression that is evaluated for each potential row. Only those

rows that evaluate to true are actually joined. A JOIN...ON looks like

this:

SELECT ... FROM t1 JOIN t2 ON conditional_expression ...An example of this is shown in Figure 5-2.

If the input tables have

C and D columns,

respectively, a JOIN...ON

will always result in C+D columns.

The conditional expression can be used to

test for anything, but the most common type of expression tests

for equality between similar columns in both tables. For

example, in a business employee database, there is likely to be

an employee table that

contains (among other things) a name column and an eid column (employee ID number). Any other

table that needs to associate rows to a specific employee will

also have an eid column that

acts as a pointer or reference to the correct employee. This

relationship makes it very common to have queries with ON expressions similar

to:

SELECT ... FROM employee JOIN resource ON employee.eid = resource.eid ...

This query will result in an output table

where the rows from the resource table are correctly matched to their

corresponding rows in the employee table.

This JOIN

has two issues. First, that ON condition is a lot to type out for something

so common. Second, the resulting table will have two eid columns, but for any given

row, the values of those two columns will always be identical.

To avoid redundancy and keep the phrasing shorter, inner join

conditions can be declared with a USING expression. This expression specifies a

list of one or more columns:

SELECT ... FROM t1 JOIN t2 USING ( col1 ,... ) ...

Queries from the employee database would now look something like this:

SELECT ... FROM employee JOIN resource USING ( eid ) ...

To appear in a USING condition, the column name must exist in

both tables. For each listed column name, the USING

condition will test for equality between the pairs

of columns. The resulting table will have only one instance of

each listed column.

If this wasn’t concise enough, SQL provides an additional

shortcut. A

NATURAL JOIN is similar to a

JOIN...USING, only it

automatically tests for equality between the values of every

column that exists in both tables:

SELECT ... FROM t1 NATURAL JOIN t2 ...

If the input tables have

x and y columns,

respectively, a JOIN...USING

or a NATURAL JOIN will result

in anywhere from max(x,y) to

x+y columns.

Assuming eid is the only column identifier to appear in

both the employee and

resource table, our

business query becomes extremely simple:

SELECT ... FROM employee NATURAL JOIN resource ...

NATURAL

JOINs are convenient, as they are very concise,

and allow changes to the key structure of various tables without

having to update all of the corresponding queries. They can also

be a tad dangerous unless you follow some discipline in naming

your columns. Because none of the columns are explicitly named,

there is no error checking in the sanity of the join. For

example, if no matching columns are found, the JOIN will automatically (and

without warning) degrade to a CROSS

JOIN, just like any other INNER JOIN. Similarly, if two

columns accidentally end up with the same name, a NATURAL JOIN will automatically

include them in the join condition, if you wanted it or

not.

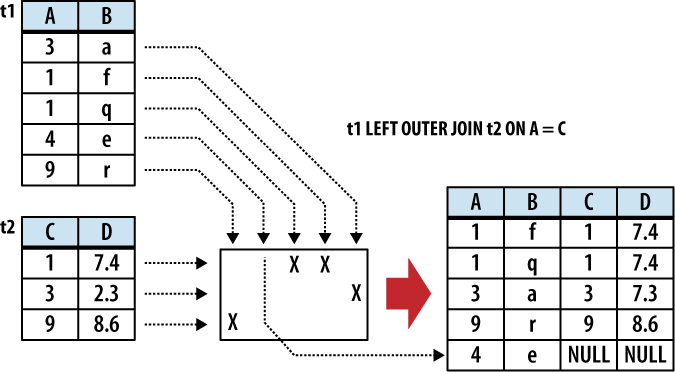

OUTER JOIN

The OUTER

JOIN is an extension of the INNER

JOIN. The SQL standard defines three types of

OUTER JOINs: LEFT, RIGHT, and FULL. Currently, SQLite only supports the

LEFT OUTER JOIN.

OUTER

JOINs have a conditional that is identical to

INNER JOINs, expressed

using an ON, USING, or NATURAL keyword. The initial

results table is calculated the same way. Once the primary

JOIN is calculated, an

OUTER join will take

any unjoined rows from one or both tables, pad them out with

NULLs, and append them to the resulting table. In the case of a

LEFT OUTER JOIN, this

is done with any unmatched rows from the first table (the table

that appears to the left of the word JOIN).

Figure 5-3 shows

an example of a LEFT OUTER

JOIN.

The result of a LEFT OUTER JOIN will contain at least one

instance of every row from the lefthand table. If the input

tables have x and y

columns, respectively, the resulting table will have no more

than x+y columns (the exact number depends

on which conditional is used). If the input tables have

n and m rows,

respectively, the resulting table can have anywhere from

n to n·m

rows.

Because they include unmatched rows,

OUTER JOINs are often

specifically used to search for unresolved or “dangling”

rows.

Table aliases

Because the JOIN operator combines the columns of different tables into one,

larger table, there may be cases when the resulting working

table has multiple columns with the same name. To avoid

ambiguity, any part of the SELECT statement can qualify any column

reference with a source-table name. However, there are some

cases when this is still not enough. For example, there are some

situations when you need to join a table to itself, resulting in

the working table having two instances of the same source-table.

Not only does this make every column name ambiguous, it makes it

impossible to distinguish them using the source-table name.

Another problem is with subqueries, as they don’t have concrete

source-table names.

To avoid ambiguity within the SELECT statement, any instance

of a source-table, view, or subquery can be assigned an alias.

This is done with the AS

keyword. For example, in the cause of a self-join, we can assign

a unique alias for each instance of the same table:

SELECT ... FROM x AS x1 JOIN x AS x2 ON x1.col1 = x2.col2 ...

Or, in the case of a subquery:

SELECT ... FROM ( SELECT ... ) AS sub ...

Technically, the AS keyword

is optional, and each source-table name can simply

be followed with an

alias name. This can be quite confusing, however, so it is

recommended you use

the AS keyword.

If any of the subquery columns conflict with

a column from a standard source table, you can now use the

sub qualifier as a

table name. For example, sub.col1.

Once a table alias has been assigned, the original source-table name becomes invalid and cannot be used as a column qualifier. You must use the alias instead.

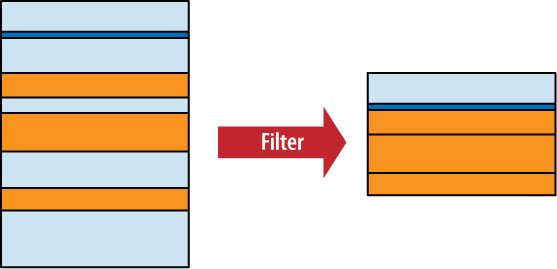

WHERE Clause

The WHERE

clause is used to filter rows from the working table

generated by the FROM clause. It is

very similar to the WHERE clause

found in the UPDATE and DELETE commands. An expression is

provided that is evaluated for each row. Any row that causes the

expression to evaluate to false or NULL is discarded. The resulting

table will have the same number of columns as the original table, but

may have fewer rows. It is not considered an error if the WHERE clause eliminates every row in

the working table. Figure 5-4 shows how the

WHERE clause works.

Some WHERE clauses can get quite

complex, resulting in a long series of AND operators used to join sub-expressions together.

Most filter for a specific row, however, searching for a specific key

value.

GROUP BY Clause

The GROUP BY

clause is used to collapse, or “flatten,” groups of rows. Groups can be

counted, averaged, or otherwise aggregated together. If you need to

perform any kind of inter-row operation that requires data from more

than one row, chances are you’ll need a GROUP

BY.

The GROUP BY

clause provides a list of grouping expressions and optional

collations. Very often the expressions are simple column references,

but they can be arbitrary expressions. The syntax looks like

this:

GROUP BYgrouping_expression[COLLATEcollation_name] [,...]

The grouping process has two steps. First, the

GROUP BY expression list is

used to arrange table rows into different groups. Once the groups are

defined, the SELECT header

(discussed in the next section) defines how those groups are flattened

down into a single row. The resulting table will have one row for each

group.

To split up the working table into groups, the list of expressions is evaluated across each row of the table. All of the rows that produce equivalent values are grouped together. An optional collation can be given with each expression. If the grouping expression involves text values, the collation is used to determine which values are equivalent. For more information on collations, see ORDER BY Clause.

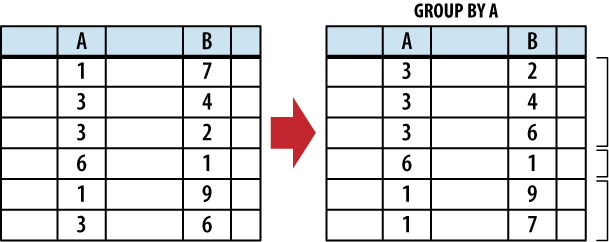

Figure 5-5 shows how

the rows are grouped together with the GROUP

BY clause.

Once grouped together, each collection of rows is

collapsed into a single row. This is typically done using aggregate

functions that are defined in the SELECT heading, which is described in the next

section, on page .

Because it is common to GROUP BY using expressions that are defined in the

SELECT header, it is possible

to simply reference SELECT heading

expressions in the GROUP BY

expression list. If a GROUP BY

expression is given as a literal integer, that number is used as a

column index in the result table defined by the SELECT header. Indexes start at one

with the leftmost column. A GROUP

BY expression can also reference a result column

alias. Result column aliases are explained in the next section.

SELECT Header

The SELECT

header is used to define the format and content of the final result table.

Any column you want to appear in the final results table must be

defined by an expression in the SELECT header. The SELECT heading is the only required step in the

SELECT command

pipeline.

The format of the header is fairly simple, consisting of a list of expressions. Each expression is evaluated in the context of each row, producing the final results table. Very often the expressions are simple column references, but they can be any arbitrary expression involving column references, literal values, or SQL functions. To generate the final query result, the list of expressions is evaluated once for each row in the working table.

Additionally, you can provide a column name

using the AS

keyword:

SELECTexpression[AScolumn_name] [,...]

Don’t confuse the AS keyword used in the SELECT header with the one used in the FROM clause. The SELECT header uses the AS keyword to assign a column name to

one of the output columns, while the FROM clauses uses the AS keyword to assign a source-table alias.

Providing an output column name is optional, but

recommended. The column name assigned to a results table is not

strictly defined unless the user provides an AS column alias. If your application searches for a

specific column name in the query results, be sure to assign a known

name using AS. Assigning a column

name will also allow other parts of the SELECT statement to reference an output column by

name. Steps in the SELECT pipeline

that are processed before the SELECT header, such as the WHERE and GROUP BY

clause, can also reference output columns by name, just as long as the

column expression does not contain an aggregate function.

If there is no working table (no FROM clause), the expression list is

evaluated a single time, producing a single row. This row is then used

as the working table. This is useful to test and evaluate standalone

expressions.

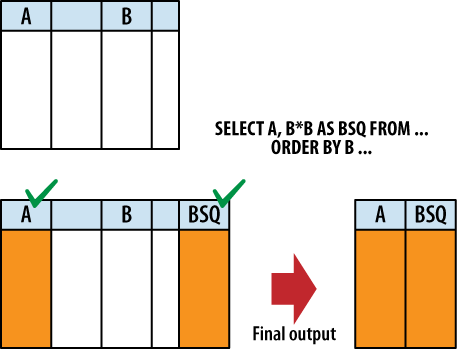

Although the SELECT header appears to filter columns from the

working table, much like the WHERE

clause filters rows, this isn’t exactly correct. All of the columns

from the original working table are still available to clauses that

are processed after the SELECT

header. For example, it is possible to sort the results (via ORDER BY, which is processed after the

SELECT header) using a column

that doesn’t appear in the query output.

It would be more accurate to say that the SELECT header tags specific columns

for output. Not until the whole SELECT pipeline has been processed and the results

are ready to be returned, are the unused columns stripped out. Figure 5-6 illustrates this point.

In addition to the standard expressions, SELECT supports two wildcards. A simple asterisk (*) will cause

every user-defined column from every source table in the FROM clause to be output. You can also

target a specific table (or table alias) using the format table_name.*

Be aware that the SELECT wildcards will not return any automatically

generated ROWID columns. To return

both the ROWID and the user-defined

columns, simply ask for them both:

SELECT ROWID, * FROM table;Wildcards do include any user-defined INTEGER PRIMARY KEY column that have

replaced the standard ROWID column.

See Primary keys for more information about how

ROWID and INTEGER PRIMARY KEY columns

interact.

In addition to determining the columns of the

query result, the SELECT header

determines how row-groups (produced by the GROUP BY clause) are flattened into a single row.

This is done using

aggregate functions. An aggregate function

takes a column expression as input and aggregates, or combines, all of

the column values from the rows of a group and produces a single

output value. Common aggregate functions include count(), min(), max(), and

avg(). Appendix E provides a full list of all the built-in

aggregate

functions.

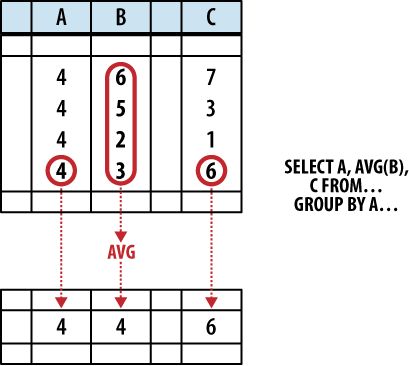

Any column or expression that is not passed

through an aggregate function will assume whatever value was contained

in the last row of the group. However, because SQL tables are

unordered, and because the SELECT

header is processed before the ORDER

BY clause, we don’t really know which row is “last.”

This means the values for any unaggregated output will be taken from

some essentially random row in the group. Figure 5-7 shows how

this works.

In some cases, picking the value from a random row

is not a bad thing. For example, if a SELECT header expression is also used as a GROUP BY expression, then we know that

column has an equivalent value in every row of a group. No matter

which row you choose, you will always get the same value.

Where you can run into trouble is when the

SELECT header uses column

references that were not part of the GROUP

BY clause, nor were they passed through aggregate

functions. In those cases there is no deterministic way to figure out

what the output value will be. To avoid this, when using a GROUP BY clause, SELECT header expressions should only

use column references as aggregate function inputs, or the header

expressions should match those used in the GROUP BY clause.

Here are some examples. In this case all of the expressions are bare column references to help make things clear:

SELECT col1, sum( col2 ) FROM tbl GROUP BY col1; -- well formed

This is a well formed statement. The GROUP BY clause shows that the rows

are being grouped based off the values in col1. That makes it safe for col1 to appear in the SELECT header, since every row in a particular group

will have an equivalent value in col1. The SELECT

header also references col2, but it

is fed into an aggregate function. The aggregate function will take

all of the col2 values from

different rows in the group and produce a logical answer—in this case,

a numerical summation.

The result of this statement will be two columns.

The first column will have one row for each unique value from col1. Each row of the second column

will have the sum of all the values in col2 that are associated with the col1 value listed in the first result

column. More detailed examples can be found at the end of the

chapter.

This next statement is not well formed:

SELECT col1, col2 FROM tbl GROUP BY col1; -- NOT well formed

As before, the rows are grouped based off the

value in col1, which makes it safe

for col1 to appear in the SELECT header. The column col2 appears bare, however, and not as

an aggregate parameter. When this statement is run, the second return

column will contain random values from the original col2 column.

Although every row within a group should have an equivalent value in a

column or expression that was used as a grouping key, that doesn’t

always mean the values are the exact same. If a collation such as

NOCASE was used, different

values (such as 'ABC' and 'abc') are considered equivalent. In

these cases, there is no way to know the specific value that will be

returned from a SELECT header. For

example:

CREATE TABLE tbl ( t ); INSERT INTO tbl VALUES ( 'ABC' ); INSERT INTO tbl VALUES ( 'abc' ); SELECT t FROM tbl GROUP BY t COLLATE NOCASE;

This query will only return one row, but there is no way to know which specific value will be returned.

Finally, if the SELECT header contains an aggregate function, but the

SELECT statement has no

GROUP BY clause, the entire

working table is treated as a single group. Since flattened groups

always return one row, this will cause the query to return only one

row—even if the working table contained no rows.

HAVING Clause

Functionally, the

HAVING clause is identical to the

WHERE clause. The HAVING clause consists of a filter

expression that is evaluated for each row of the working table. Any

row that evaluates to false or NULL is filtered out and removed. The

resulting table will have the same number of columns, but may have

fewer rows.

The main difference between the WHERE clause and the HAVING clause is where they appear in

the SELECT pipeline. The HAVING clause is processed after the

GROUP BY and SELECT clauses, allowing HAVING to filter rows based off the

results of any GROUP BY aggregate.

HAVING clauses can even have

their own aggregates, allowing them to filter on aggregate results

that are not part of the SELECT

header.

HAVING clauses

should only contain filter expressions that depend on the GROUP BY output. All other filtering

should be done in the WHERE

clause.

Both the HAVING

and WHERE clauses can reference

result column names defined in the SELECT header with the AS keyword. The main difference is that the WHERE clause can only reference

expressions that do not contain aggregate functions, while the

HAVING clause can reference

any result column.

DISTINCT Keyword

The DISTINCT

keyword will scan the result set and eliminate any duplicate rows.

This ensures the returned rows constitute a proper set. Only the

columns and values specified in the SELECT header are considered when determining if a

row is a duplicate or not. This is one of the few cases when NULLs are

considered to have “equality,” and will be eliminated.

Because SELECT

DISTINCT must compare every row against every other

row, it is an expensive operation. In a well-designed database, it is

also rarely required. Therefore, its usage is somewhat unusual.

ORDER BY Clause

The ORDER BY

clause is used to sort, or order, the rows of the results table. A

list of one or more sort expressions is provided. The first expression

is used to sort the table. The second expression is used to sort any

equivalent rows from the first sort, and so on. Each expression can be

sorted in ascending or descending order.

The basic format of the ORDER BY clause looks like this:

ORDER BYexpression[COLLATEcollation_name] [ASC|DESC] [,...]

The expression is evaluated for each row. Very

often the expression is a simple column reference, but it can be any

expression. The resulting value is then compared against those values

generated by other rows. If given, the named collation is used to sort

the values. A collation defines a specific sorting order for text

values. The

ASC or DESC keywords can be used to force the sort in an

ascending or descending order. By default, values are sorted in an

ascending order using the default collation.

An ORDER BY

expression can utilize any source column, including those that do not

appear in the query result. Like GROUP

BY, if an ORDER BY

expression consists of a literal integer, it is assumed to be a column

index. Column indexes start on the left with 1, so the phrase ORDER BY 2 will sort the results table

by its second column.

Because SQLite allows different datatypes to be stored in the same column, sorting can get a bit more interesting. When a mixed-type column is sorted, NULLs will be sorted to the top. Next, integer and real values will be mixed together in proper numeric order. The numbers will be followed by text values, with BLOB values at the end. There will be no attempt to convert types. For example, a text value holding a string representation of a number will be sorted in with the other text values, and not with the numeric values.

In the case of numeric values, the natural sort

order is well defined. Text values are sorted by the active collation,

while BLOB values are always sorted using the BINARY collation. SQLite comes with three built-in

collation functions. You can also use the API to define your own

collation functions. The three built-in collations are:

-

BINARY Text values are sorted according to the semantics of the POSIX

memcmp()call. The encoding of a text value is not taken into account, essentially treating it as a large binary string. BLOB values are always sorted with this collation. This is the default collation.-

NOCASE Same as

BINARY, only ASCII uppercase characters are converted to lowercase before the comparison is done. The case-conversion is strictly done on 7-bit ASCII values. The normal SQLite distribution does not support UTF-aware collations.-

RTRIM Same as

BINARY, only trailing (righthand) whitespace is ignored.

While ORDER BY

is extremely useful, it should only be used when it is actually

needed—especially with

very large result tables. Although SQLite can sometimes make use of an

index to calculate the query results in order, in many cases SQLite

must first calculate the entire result set and then sort it, before

rows are returned. In that case, the intermediate results table must

be held in memory or on disk until it is fully computed and can then

be sorted.

Overall, there are plenty of situations where

ORDER BY is justified, if not

required. Just be aware there can be some significant costs involved

in its use, and you shouldn’t get in the habit of tacking it on to

every query “just because.”

LIMIT and OFFSET Clauses

The LIMIT and

OFFSET clauses allow you to extract a specific subset of rows from the

final results table. LIMIT defines

the maximum number of rows that will be returned, while OFFSET defines the number of rows to

skip before returning the first row. If no OFFSET is provided, the LIMIT is applied to the top of the table. If a

negative LIMIT is provided, the

LIMIT is removed and will

return the whole table.

There are three ways to define a LIMIT and OFFSET:

LIMITlimit_countLIMITlimit_countOFFSEToffset_countLIMIToffset_count,limit_count

Caution

Note that if both a limit and offset are given using the third format, the order of the numbers is reversed.

Here are some examples. Notice that the OFFSET value defines how many rows are

skipped, not the position of the first row:

LIMIT 10 -- returns the first 10 rows (rows 1 - 10) LIMIT 10 OFFSET 3 -- returns rows 4 - 13 LIMIT 3 OFFSET 20 -- returns rows 21 - 23 LIMIT 3, 20 -- returns rows 4 - 23 (different from above!)

Although it is not strictly required, you usually

want to define an ORDER BY if

you’re using a LIMIT. Without an

ORDER BY, there is no

well-defined order to the result, making the limit and offset somewhat

meaningless.