APPENDIX C

Understanding the Pitfalls of SSLv2

With all the elements of a secure connection — cryptography, authentication, secure key exchange and message authentication — it should be a simple matter to put it all together securely, right? Well, as it turns out, even when all the pieces are in place, it's surprisingly easy to get subtly wrong. Just ask the original Netscape engineers who released SSLv2. On paper, they did everything right, but the protocol was found to have subtle, but fatal flaws after it had been widely released. To the credit of the Netscape protocol designers, everybody else thought that they had gotten everything right the first time around as well. It wasn't until the protocol had been intensively studied in action that the chinks in the armor began to show.

Because SSLv2 was widely disseminated before it was found to be flawed, it's interesting to start by examining exactly how it worked, and then move on to see what's wrong with the protocol. SSL was specified fairly rigorously and submitted as an IETF draft (http://www.mozilla.org/projects/security/pki/nss/ssl/draft02.html), but its flaws were discovered before it was accepted, so it's never been officially blessed by the IETF. Although SSLv2 has been deprecated, there are pockets of support for it, so you can easily find the protocol details.

This appendix details an SSLv2 implementation similar to the TLS implementation presented in Chapter 6. I've assumed you're familiar with Chapter 6; I discuss only the differences between the two implementations here. I do my best to avoid covering old ground, but since SSLv2 and TLS 1.0 have the same goals — to encrypt and authenticate a channel — it's unavoidable that some similar elements reappear here.

Listing C-1 details the SSL function prototypes. Notice that there's no ssl_shutdown routine; SSLv2 didn't explicitly mark the end of a secure session.

Listing C-1: "ssl.h" SSL function prototypes

int ssl_connect( int connection, SSLParameters *parameters );

int ssl_send( int connection, const char *application_data, int length,

int options, SSLParameters *parameters );

int ssl_recv( int connection, char *target_buffer, int buffer_size,

int options, SSLParameters *parameters );

You can modify the HTTP client implementation introduced in Chapter 1 as shown in Listing C-2 to be SSL-enabled by replacing socket-layer function calls with these new SSL library calls.

Listing C-2: "https.c" main routine with SSLv2 support

#define HTTPS_PORT 443

...

int main( int argc, char *argv[ ] )

{

...

SSLParameters ssl_context;

...

host_address.sin_family = AF_INET;

host_address.sin_port = htons( HTTPS_PORT );

memcpy( &host_address.sin_addr, host_name->h_addr_list[ 0 ],

sizeof( struct in_addr ) );

if ( connect( client_connection, ( struct sockaddr * ) &host_address,

sizeof( host_address ) ) == −1 )

{

perror( "Unable to connect to host" );

return 2;

}

if ( ssl_connect( client_connection, &ssl_context ) )

{

fprintf( stderr, "Error: unable to negotiate SSL connection.\n" );

return 3;

}

http_get( client_connection, path, host, &ssl_context );

display_result( client_connection, &ssl_context );

...

As you can see, the changes to the main routine, which establishes the HTTP connection, are fairly minimal. The changes to the http_get routine in Listing C-3 are similarly unobtrusive.

Listing C-3: "https.c" http_get with SSLv2 support

int http_get( int connection, const char *path, const char *host, SSLParameters *ssl_context ) { static char get_command[ MAX_GET_COMMAND ]; sprintf( get_command, "GET /%s HTTP/1.1\r\n", path ); if ( ssl_send( connection, get_command, strlen( get_command ), 0, ssl_context ) == −1 ) { return −1; } sprintf( get_command, "Host: %s\r\n", host ); if ( ssl_send( connection, get_command, strlen( get_command ), 0, ssl_context ) == −1 ) { return −1; } strcpy( get_command, "Connection: Close\r\n\r\n" ); if ( ssl_send( connection, get_command, strlen( get_command ), 0, ssl_context ) == −1 ) { return −1; } return 0; } ... int display_result( int connection, SSLParameters *ssl_context ) { int received = 0; static char recv_buf[ BUFFER_SIZE + 1 ]; // Can't exit when return value is 0 like in http.c, since empty SSL // messages can be sent (openssl does this) while ( ( received = ssl_recv( connection, recv_buf, BUFFER_SIZE, 0, ssl_context ) ) >= 0 ) { recv_buf[ received ] = '\0'; printf( "data: %s", recv_buf ); } printf( "\n" ); }

The application flow is exactly the same as before — in fact, other than the extra call to ssl_connect after the actual socket is connected, you could make this completely transparent by defining a few macros.

Implementing the SSL Handshake

The bulk of the work in an SSL library is in the SSL handshake. When the ssl_connect function is called, the connection is unsecured. ssl_connect is primarily responsible for performing a secure key exchange and keeping track of the exchanged keys. Its job is to fill out the SSLParameters structure that's passed in as shown in Listing C-4.

Listing C-4: "ssl.h" SSLParameters declaration

// Technically, this is a variable-length parameter; the client can send

// between 16 and 32 bytes. Here, it's left as a fixed-length

// parameter.

#define CHALLENGE_LEN 16

typedef struct

{

CipherSpec *active_cipher_spec;

CipherSpec *proposed_cipher_spec;

// Flow-control variables

int got_server_hello;

int got_server_verify;

int got_server_finished;

int handshake_finished;

int connection_id_len;

rsa_key server_public_key;

unsigned char challenge[ CHALLENGE_LEN ];

unsigned char *master_key;

unsigned char *connection_id;

void *read_state;

void *write_state;

unsigned char *read_key;

unsigned char *write_key;

unsigned char *read_iv;

unsigned char *write_iv;

int read_sequence_number;

int write_sequence_number;

unsigned char *unread_buffer;

int unread_length;

}

SSLParameters;

The server_public_key is the key with which RSA key exchange is performed as described in Chapter 3. (SSLv2 didn't support Diffie-Hellman key exchange.) You should be familiar with the read_key, write_key, and write_iv from Chapter 2. There are a few internal variables to examine as you go through the implementation of ssl_connect.

The first two parameters are the active_cipher_spec and the proposed_cipher_spec. The cipher_spec describes exactly what encryption and MAC should be applied to each packet.

The format of a CipherSpec structure in Listing C-5 shouldn't be too surprising.

Listing C-5: "ssl.h" SSLv2 CipherSpec declaration

typedef struct

{

int cipher_spec_code;

int block_size;

int IV_size;

int key_size;

int hash_size;

void (*bulk_encrypt)( const unsigned char *plaintext,

const int plaintext_len,

unsigned char ciphertext[],

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key );

void (*bulk_decrypt)( const unsigned char *ciphertext,

const int ciphertext_len,

unsigned char plaintext[],

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key );

void (*new_digest)( digest_ctx *context );

}

CipherSpec;

Each cipher and MAC combination is identified by a unique, three-byte combination. SSLv2 defined 7 cipher/MAC combinations as shown in Listing C-6.

Listing C-6: "ssl.h" CipherSuite Declarations

#define SSL_CK_RC4_128_WITH_MD5 0x800001 #define SSL_CK_DES_64_CBC_WITH_MD5 0x400006 #define SSL_CK_DES_192_EDE3_CBC_WITH_MD5 0xc00007 #define SSL_CK_RC4_128_EXPORT40_WITH_MD5 0x800002 #define SSL_CK_RC2_128_CBC_WITH_MD5 0x800003 #define SSL_CK_RC2_128_CBC_EXPORT40_WITH_MD5 0x800004 #define SSL_CK_IDEA_128_CBC_WITH_MD5 0x800005 #define SSL_PE_NO_CIPHER 0x0100 #define SSL_PE_NO_CERTIFICATE 0x0200 #define SSL_PE_BAD_CERTIFICATE 0x0400 #define SSL_PE_UNSUPPORTED_CERTIFICATE_TYPE 0x0600

#define SSL_CT_X509_CERTIFICATE 1 #define SSL_MT_ERROR 0 #define SSL_MT_CLIENT_HELLO 1 #define SSL_MT_CLIENT_MASTER_KEY 2 #define SSL_MT_CLIENT_FINISHED 3 #define SSL_MT_SERVER_HELLO 4 #define SSL_MT_SERVER_VERIFY 5 #define SSL_MT_SERVER_FINISHED 6

Because RC2 or IDEA weren't examined, they won't be supported here, although it should be fairly straightforward at this point how you might go about doing so. Notice that in all cases, the MAC algorithm is MD5; SHA is not supported in SSLv2. RC4 is supported, of course, and two other bulk cipher algorithms, DES and 3DES (identified here as DES_192_EDE3) are defined. In all cases, block ciphers use CBC chaining.

Also notice SSL_CK_RC4_128_EXPORT40_WITH_MD5. SSLv2 supports export-grade ciphers as discussed in Chapter 8, but it does so slightly differently than TLS does. The 128 in the cipher suite identifier, of course, identifies the key length in bits. However, export40 mandates that only 40 bits of the key be protected by the key exchange algorithm; the remaining 88 bits are transmitted in the clear.

Add support for three of these ciphers in Listing C-7.

Listing C-7: "ssl.c" cipher spec declarations

#define NUM_CIPHER_SPECS 3

static CipherSpec specs[] =

{

{ SSL_CK_DES_64_CBC_WITH_MD5, 8, 8, 8, MD5_BYTE_SIZE, des_encrypt,

des_decrypt, new_md5_digest },

{ SSL_CK_DES_192_EDE3_CBC_WITH_MD5, 8, 8, 24, MD5_BYTE_SIZE,

des3_encrypt, des3_decrypt, new_md5_digest },

{ SSL_CK_RC4_128_WITH_MD5, 0, 0, 16, MD5_BYTE_SIZE, rc4_128_encrypt,

rc4_128_decrypt, new_md5_digest }

};

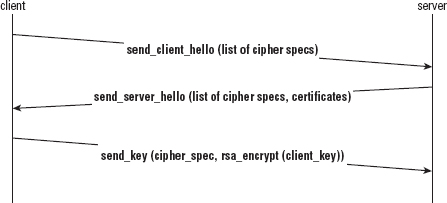

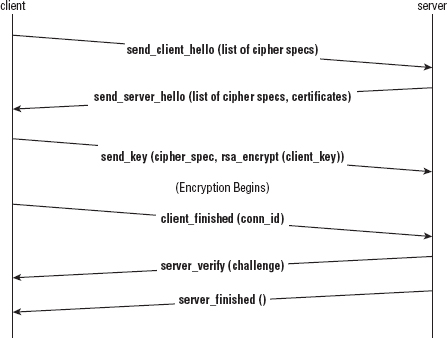

So how does the SSL handshake work? First, the client advertises to the server which cipher specs it supports; it's not required to support all of them. The server responds by advising the client which specs it supports, as well as sending an X.509 certificate containing its public RSA key. Assuming there's at least one cipher spec that both sides understand, the client selects one, creates a key, encrypts it using the server's public key, and sends it on. This exchange is illustrated in Figure C-1.

As a double-check against man-in-the-middle attacks, the client also sends a challenge token, which the server must encrypt using the newly negotiated key before sending back the encrypted value, in its hello message. The client verifies that the decrypted token is the same as what was sent. If it's not, the handshake is rejected. Likewise, the server sends a connection-id that the client must send back, encrypted, after the key exchange succeeds.

The complete handshake is illustrated in Figure C-2.

Figure C-1: SSLv2 opening handshake

Figure C-2: SSLv2 complete handshake

The specification states that the client finished message should be sent before the server_verify is received. However, every working implementation sends the server_verify immediately after the key is received. This isn't a problem and doesn't affect the security of the implementation, but it is something that you need to be aware of when coding the SSLv2 handshake.

All six of these handshake messages are sent in the ssl_connect function. After the server_finished message has been received, the higher-level protocol begins.

The code for ssl_connect is shown in Listing C-8.

Listing C-8: "ssl.c" ssl_connect

int ssl_connect( int connection,

SSLParameters *parameters )

{

init_parameters( parameters );

if ( send_client_hello( connection, parameters ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

while ( !parameters->got_server_hello )

{

// set proposed_cipher_spec from server hello

if ( receive_ssl_message( connection, NULL, 0, parameters ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

}

// If proposed_cipher_spec is not set at this point, no cipher could

// be negotiated

if ( parameters->proposed_cipher_spec == NULL )

{

send_error( connection, SSL_PE_NO_CIPHER, parameters );

return −1;

}

compute_keys( parameters );

if ( send_client_master_key( connection, parameters ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

// From this point forward, everything is encrypted

parameters->active_cipher_spec = parameters->proposed_cipher_spec;

parameters->proposed_cipher_spec = NULL;

if ( send_client_finished( connection, parameters ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

while ( !parameters->got_server_verify ) { if ( receive_ssl_message( connection, NULL, 0, parameters ) == −1 ) { return −1; } } while ( !parameters->got_server_finished ) { if ( receive_ssl_message( connection, NULL, 0, parameters ) == −1 ) { return −1; } } parameters->handshake_finished = 1; return 0; }

The first call is to init_parameters in Listing C-9, which just resets all of the SSLParameters values.

Listing C-9: "ssl.c" init_parameters

static void init_parameters( SSLParameters *parameters )

{

int i;

parameters->active_cipher_spec = NULL;

parameters->proposed_cipher_spec = NULL;

parameters->write_key = NULL;

parameters->read_key = NULL;

parameters->read_state = NULL;

parameters->write_state = NULL;

parameters->write_iv = NULL;

parameters->read_iv = NULL;

parameters->write_sequence_number = 0;

parameters->read_sequence_number = 0;

parameters->got_server_hello = 0;

parameters->got_server_verify = 0;

parameters->handshake_finished = 0;

for ( i = 0; i < CHALLENGE_LEN; i++ )

{

// XXX this should be random

parameters->challenge[ i ] = i;

}

parameters->master_key = NULL;

parameters->server_public_key.modulus = malloc( sizeof( huge ) ); parameters->server_public_key.exponent = malloc( sizeof( huge ) ); set_huge( parameters->server_public_key.modulus, 0 ); set_huge( parameters->server_public_key.exponent, 0 ); parameters->unread_buffer = NULL; parameters->unread_length = 0; }

You can easily match the remaining function calls with the sequence diagram in Figure C-2. If this function runs to completion, the caller can assume that a secure channel has been successfully negotiated and, for the most part, does not need to worry about it again. An implementation of each of the handshake functions is presented next.

SSL Client Hello

The client is responsible for initiating an SSL handshake by sending the ClientHello message. If this isn't the first message that is sent, the server responds with an error and shuts down the socket. So what does this message look like? Listing C-10 defines in in C struct form.

Listing C-10: "ssl.h" ClientHello declaration

typedef struct

{

unsigned char version_major;

unsigned char version_minor;

unsigned short cipher_specs_length;

unsigned short session_id_length;

unsigned short challenge_length;

unsigned char *cipher_specs;

unsigned char *session_id;

unsigned char *challenge;

}

ClientHello;

I examine the specifics of the wire format in a minute, but first examine the contents of the client hello message. As you see, the client starts by announcing the version of SSL that it understands. You might expect this to be 2.0, but SSLv2 is actually version 0.2! Although SSLv2 was pretty widespread at one time, the designers considered it to be fairly experimental when it was proposed. It was never even actually officially "released."

Following the version number are the cipher specs that this client understands, a sessionID, and the challenge token. I have discussed the cipher specs and the challenge token, and session IDs are in place to support session resumption as detailed in Chapter 8.

Because each of the three parameters — cipher specs, session ID and challenge token — can be of variable length, length bytes are given for each before their values. You can build a client hello packet for a new, non-resumed, session as in Listing C-11.

Listing C-11: "ssl.c" send_client_hello

#define SSL_MT_CLIENT_HELLO 1

static int send_client_hello( int connection,

SSLParameters *parameters )

{

unsigned char *send_buffer, *write_buffer;

int buf_len;

int i;

unsigned short network_number;

int status = 0;

ClientHello package;

package.version_major = 0;

package.version_minor = 2;

package.cipher_specs_length = sizeof( specs ) / sizeof( CipherSpec );

package.session_id_length = 0;

package.challenge_length = CHALLENGE_LEN;

// Each cipher spec takes up 3 bytes in SSLv2

package.cipher_specs = malloc( sizeof( unsigned char ) * 3 *

package.cipher_specs_length );

package.session_id = malloc( sizeof( unsigned char ) *

package.session_id_length );

package.challenge = malloc( sizeof( unsigned char ) *

package.challenge_length );

buf_len = sizeof( unsigned char ) * 2 +

sizeof( unsigned short ) * 3 +

( package.cipher_specs_length * 3 ) +

package.session_id_length +

package.challenge_length;

for ( i = 0; i < package.cipher_specs_length; i++ )

{

memcpy( package.cipher_specs + ( i * 3 ),

&specs[ i ].cipher_spec_code, 3 );

}

memcpy( package.challenge, parameters->challenge, CHALLENGE_LEN );

write_buffer = send_buffer = malloc( buf_len );

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer,

&package.version_major, 1 );

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, &package.version_minor, 1 ); network_number = htons( package.cipher_specs_length * 3 ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * ) &network_number, 2 ); network_number = htons( package.session_id_length ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * ) &network_number, 2 ); network_number = htons( package.challenge_length ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * ) &network_number, 2 ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, package.cipher_specs, package.cipher_specs_length * 3 ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, package.session_id, package.session_id_length ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, package.challenge, package.challenge_length ); status = send_handshake_message( connection, SSL_MT_CLIENT_HELLO, send_buffer, buf_len, parameters ); free( package.cipher_specs ); free( package.session_id ); free( package.challenge ); free( send_buffer ); return status; }

This code should be straightforward to understand. First, fill out a ClientHello structure and then "flatten" it into a linear memory array with the byte ordering corrected. Then invoke send_handshake_message with a pointer to the flattened buffer.

Listing C-12 shows the send_handshake_message call. You pass in five parameters — the socket id (connection), the message type (client hello in this case), the buffer and its length, and finally the SSL parameters array you're building. This function is actually a small one.

Listing C-12: "ssl.c" send_handshake_message

static int send_handshake_message( int connection,

unsigned char message_type,

unsigned char *data,

int data_len,

SSLParameters *parameters )

{

unsigned char *buffer;

int buf_len;

buf_len = data_len + 1;

buffer = malloc( buf_len ); buffer[ 0 ] = message_type; memcpy( buffer + 1, data, data_len ); if ( send_message( connection, buffer, buf_len, parameters ) == −1 ) { return −1; } free( buffer ); return 0; }

The send_message function in Listing C-13 actually writes something onto the socket itself.

Listing C-13: "ssl.c" send_message

static int send_message( int connection,

const unsigned char *data,

unsigned short data_len,

SSLParameters *parameters )

{

unsigned char *buffer;

int buf_len;

unsigned short header_len;

buf_len = data_len + 2;

buffer = malloc( buf_len );

header_len = htons( data_len );

memcpy( buffer, &header_len, 2 );

buffer[ 0 ] |= 0x80; // indicate two-byte length

memcpy( buffer + 2, data, data_len );

if ( send( connection, ( void * ) buffer, buf_len, 0 ) < buf_len )

{

return −1;

}

free( buffer );

return 0;

}

This function, like the last, just prepends yet another header in front of the data to be sent. This header consists of the two-byte length of the payload, followed by the payload. In the case of a handshake message, the first byte of the payload is a byte indicating which handshake message this is. Note that there's nothing to indicate that this is a handshake message to begin with. The receiver is supposed to keep track of where it is in the overall exchange. In other words, if the server hasn't gotten any data yet, it should assume that the next message it receives will be a ClientHello handshake message.

Every record transmitted over an SSL-secured channel must start with this header, including encrypted application data. When data is encrypted, the header is stripped off, the data is decrypted, and then it's passed up to the calling function.

The only potentially confusing part of the send_message function in Listing C-13 is this:

buffer[ 0 ] |= 0x80; // indicate two-byte length

SSLv2 allows for two- or three-byte payload lengths. In a nod toward efficiency, the SSLv2 protocol designers borrowed a page from the ASN.1 protocol designers' playbook and used the first bit of the first byte to indicate the length of the length. If the most significant bit of the first byte is 1, this is a two-byte length. This function is extended for three-byte lengths later.

At this point, the server accepts the client hello, processes it or rejects it with an error, and sends back its own hello message.

SSL Server Hello

The ServerHello message is structured as in Listing C-14.

Listing C-14: "ssl.h" ServerHello declaration

typedef struct

{

unsigned char session_id_hit;

unsigned char certificate_type;

unsigned char server_version_major;

unsigned char server_version_minor;

unsigned short certificate_length;

unsigned short cipher_specs_length;

unsigned short connection_id_length;

signed_x509_certificate certificate;

unsigned char *cipher_specs;

unsigned char *connection_id;

}

ServerHello;

The first byte, session_id_hit, is a true/false indicator of whether the session ID supplied was recognized by the server — 0 for false, 1 for true. Of course, if the client doesn't supply a session ID indicating a request for a brand-new session, session_id_hit is always 0.

The next byte is the certificate_type. This was added to support other certificates besides x.509, although no other certificate types were ever defined. This is followed by the version of SSL that the server understands. The specification isn't clear on what should be done if, in theory, the server understands a higher version of the protocol than the client, or if it doesn't understand the version that the client sent. However, this turned out to be a moot point. The next version of SSL was defined completely incompatibly with SSLv2, so version interoperability never came up. If the client sends an SSLv3+ handshake message to an SSLv2-only server, the server doesn't understand the message to begin with and immediately errors out. Likewise, if the client requests SSLv2, but the server would rather negotiate SSLv3 (which would be good advice), its only option is to reject the client hello with an error and hope the client retries with SSLv3 semantics. To complicate matters even further, there's no standard SSLv2 error message indicating that the protocol version requested isn't supported. As such, the only thing you ever see in these two bytes is 0, 2.

Finally, the server sends its variable length parameters — its certificate, its supported cipher specs, and its connection ID.

The certificate is in the format described in Chapter 5. Actually, the SSLv2 specification wasn't entirely clear on how the certificate should be encoded, but all implementations present the certificate in ANS.1 DER encoding. Notice that the definition only leaves room for one certificate — there's no concept of "certificate chaining" here. SSLv3/TLS 1.0 introduced certificate chaining, although without x.509v3 certificate extensions, this turned out to be a mistake.

The certificate is followed by a variable-length list of the cipher specs that the server supports. It's not clear whether this should be all of the ciphers that the server supports, or just the union of those that it supports with those that it knows the client supports. Remember, the client has already sent an exhaustive list of which ciphers it supports in its own hello message. However, it's unclear what use a client might make of the knowledge that the server supports a cipher that the client doesn't, so OpenSSL 0.9.8 returns the union of the two lists. Notice that SSLv2 lets the client finally select the cipher suite; SSLv3+ has the server do this — which actually makes more sense.

Finally, the server sends back a connection_id that serves the same purpose to the server that the challenge token served the client — to prevent replay attacks by forcing the client to encrypt a random value on each connection attempt. Note that the connection ID is not the session ID — that will be sent at the very end, in the server finished message.

After ssl_connect sends its ClientHello message, it waits until the server responds with a ServerHello:

while ( !parameters->got_server_hello )

{

// set proposed_cipher_spec from server hello

receive_ssl_message in Listing C-15 thus reads the data available from the socket, strips off the SSL header, and, if it's a handshake message, processes it.

Listing C-15: "ssl.c" receive_ssl_message

static int receive_ssl_message( int connection,

char *target_buffer,

int target_bufsz,

SSLParameters *parameters )

{

int status = 0;

unsigned short message_len;

unsigned short bytes_read;

unsigned short remaining;

unsigned char *buffer, *bufptr;

// New message - read the length first

if ( recv( connection, &message_len, 2, 0 ) <= 0 )

{

return −1;

}

message_len = ntohs( message_len );

if ( message_len & 0x8000 )

{

// two-byte length

message_len &= 0x7FFF;

}

// else TODO

// Now read the rest of the message. This will fail if enough memory

// isn't available, but this really should never be the case.

bufptr = buffer = malloc( message_len );

remaining = message_len;

bytes_read = 0;

while ( remaining )

{

if ( ( bytes_read = recv( connection, bufptr,

remaining, 0 ) ) <= 0 )

{

return −1;

}

bufptr += bytes_read;

remaining -= bytes_read;

} if ( !parameters->handshake_finished ) { switch ( buffer[ 0 ] ) { case SSL_MT_ERROR: status = parse_server_error( parameters, buffer + 1 ); return −1; case SSL_MT_SERVER_HELLO: status = parse_server_hello( parameters, buffer + 1 ); if ( status == −1 ) { send_error( connection, SSL_PE_UNSUPPORTED_CERTIFICATE_TYPE, parameters ); } break; default: printf( "Skipping unrecognized handshake message %d\n", buffer[ 0 ] ); break; } } free( buffer ); return status; }

First, read the length of the message. Remember that the first two or three bytes of every SSLv2 message must be the length of the following payload:

if ( recv( connection, &message_len, 2, 0 ) <= 0 )

{

return −1;

}

message_len = ntohs( message_len );

if ( message_len & 0x8000 )

{

// two-byte length

message_len &= 0x7FFF;

}

Because you know this is an SSLv2 connection, you know that at least two bytes should be available. Check the MSB of the first byte and, if it's 1, mask it out to get the actual length (you'll deal with the three-byte case below).

Next, read the whole payload into memory:

bufptr = buffer = malloc( message_len );

remaining = message_len;

bytes_read = 0;

while ( remaining )

{

if ( ( bytes_read = recv( connection, bufptr,

remaining, 0 ) ) <= 0 )

{

return −1;

}

bufptr += bytes_read;

remaining -= bytes_read;

}

Finally, parse and handle the message. If the HandshakeFinished flag hasn't been set, then this message ought to be a handshake message, and the first byte should therefore be a handshake message type.

if ( !parameters->handshake_finished )

{

switch ( buffer[ 0 ] )

{

case SSL_MT_ERROR:

status = parse_server_error( parameters, buffer + 1 );

return −1;

case SSL_MT_SERVER_HELLO:

status = parse_server_hello( parameters, buffer + 1 );

if ( status == −1 )

{

send_error( connection,

SSL_PE_UNSUPPORTED_CERTIFICATE_TYPE,

parameters );

}

break;

default:

printf( "Skipping unrecognized handshake message %d\n",

buffer[ 0 ] );

break;

}

}

The error message format is pretty simple as shown in Listing C-16: It's a two-byte error code. SSLv2 only defines four error codes, so one byte would have been more than enough, but the Netscape designers were being forward-thinking.

Listing C-16: "ssl.c" parse_server_error

static int parse_server_error( SSLParameters *parameters, unsigned char *buffer ) { unsigned short error_code; memcpy( &error_code, buffer, sizeof( unsigned short ) ); error_code = ntohs( error_code ); switch ( error_code ) { case SSL_PE_NO_CIPHER: fprintf( stderr, "No common cipher.\n" ); break; default: fprintf( stderr, "Unknown or unexpected error %d.\n", error_code ); break; } return error_code; }

Also notice that this routine only processes one type of error code, but there are three others spelled out in the specification: no certificate, bad certificate, and unsupported certificate. The server won't send any of these to the client — at least not in this implementation — so don't bother recognizing them.

The server hello message is accepted and parsed by the parse_server_hello function in Listing C-17.

Listing C-17: "ssl.c" parse_server_hello

static int parse_server_hello( SSLParameters *parameters,

unsigned char *buffer )

{

int i, j;

int status = 0;

ServerHello package;

buffer = read_buffer( &package.session_id_hit, buffer, 1 );

buffer = read_buffer( &package.certificate_type, buffer, 1 );

buffer = read_buffer( &package.server_version_major, buffer, 1 );

buffer = read_buffer( &package.server_version_minor, buffer, 1 );

buffer = read_buffer( ( void * ) &package.certificate_length,

buffer, 2 );

package.certificate_length = ntohs( package.certificate_length );

buffer = read_buffer( ( void * ) &package.cipher_specs_length,

buffer, 2 );

package.cipher_specs_length = ntohs( package.cipher_specs_length ); buffer = read_buffer( ( void * ) &package.connection_id_length, buffer, 2 ); package.connection_id_length = ntohs( package.connection_id_length ); // Only one of these was ever defined if ( package.certificate_type == SSL_CT_X509_CERTIFICATE ) { init_x509_certificate( &package.certificate ); if ( status = parse_x509_certificate( buffer, package.certificate_length, &package.certificate ) ) { // Abort immediately if there's a problem reading the certificate return status; } } else { printf( "Error - unrecognized certificate type %d\n", package.certificate_type ); status = −1; return status; } buffer += package.certificate_length; package.cipher_specs = malloc( package.cipher_specs_length ); buffer = read_buffer( package.cipher_specs, buffer, package.cipher_specs_length ); package.connection_id = malloc( package.connection_id_length ); buffer = read_buffer( package.connection_id, buffer, package.connection_id_length ); parameters->got_server_hello = 1; // Copy connection ID into parameter state; this is needed for key // computation, next parameters->connection_id_len = package.connection_id_length; parameters->connection_id = malloc( parameters->connection_id_len ); memcpy( parameters->connection_id, package.connection_id, parameters->connection_id_len ); // cycle through the list of cipher specs until one is found that // matches // XXX this will match the last one on the list for ( i = 0; i < NUM_CIPHER_SPECS; i++ ) { for ( j = 0; j < package.cipher_specs_length; j++ ) { if ( !memcmp( package.cipher_specs + ( j * 3 ), &specs[ i ].cipher_spec_code, 3 ) ) { parameters->proposed_cipher_spec = &specs[ i ];

break; } } } // TODO validate the certificate/Check expiration date/Signer copy_huge( parameters->server_public_key.modulus, package.certificate.tbsCertificate.subjectPublicKeyInfo. rsa_public_key.modulus ); copy_huge( parameters->server_public_key.exponent, package.certificate.tbsCertificate.subjectPublicKeyInfo. rsa_public_key.exponent ); free( package.cipher_specs ); free( package.connection_id ); free_x509_certificate( &package.certificate ); return status; }

Part of the unflattening process involves a call to parse_x509_certificate, developed in Chapter 5. The process of parsing a certificate did not change between SSLv2 and TLS 1.2, although the certificate format itself grew a bit to include extensions and unique IDs.

Now, choose a cipher spec. Cycle through the list presented by the server and when you find one that's supported by this implementation, make that the proposed_cipher_spec. Also keep track of the connection ID, and the server's public RSA key.

Finally, if anything went wrong, receive_ssl_message will halt the process with an error message:

if ( status == −1 )

{

send_error( connection,

SSL_PE_UNSUPPORTED_CERTIFICATE_TYPE,

parameters );

}

Sending an SSL error message in Listing C-18 is as simple as receiving one.

Listing C-18: "ssl.c" send_error

static int send_error( int connection,

unsigned short error_code,

SSLParameters *parameters )

{

unsigned char buffer[ 3 ];

unsigned short send_error;

buffer[ 0 ] = SSL_MT_ERROR;

send_error = htons( error_code ); memcpy( buffer + 1, &send_error, sizeof( unsigned short ) ); if ( send_message( connection, buffer, 3, parameters ) == −1 ) { return −1; } return 0; }

If a server hello response was received, and the certificate parsed OK, but the client and server had no common cipher specs, the ssl_connect responds with an error (note that the server could, and should, have done this instead of sending a server hello message):

if ( parameters->proposed_cipher_spec == NULL )

{

send_error( connection, SSL_PE_NO_CIPHER, parameters );

return −1;

}

If nothing has gone wrong, at this point you have a public key, a proposed cipher spec, and have exchanged both a challenge token and a connection ID. You now have enough information to compute keys.

SSL Client Master Key

SSLv3+ generated keying material through a fairly complex pseudo-random function. SSLv2 didn't; instead, it just MD5-hashed a random master key along with the challenge token and the connection ID to produce as much keying material — read/write keys — as it needed. This master key is the same length as the cipher spec's symmetric key. Because you're only supporting three cipher specs here, this is easy to enumerate: 8 bytes for DES, 24 bytes for 3DES, and 16 bytes for 128-bit RC4.

Remember that the MD5 algorithm produces 16 bytes of output, regardless of the length of its input. For DES, that's as much key material as you need for both sides; each side needs 8 bytes. For RC4, you have to run the MD5 algorithm twice, and for 3DES, three times. So that you don't get the same key over and over again, you must also increment a counter on each run.

NOTE The last published draft specification for SSLv2 (version 0.2, 1995) stated that the counter should not be used — that is, the byte itself should be omitted — for DES, which only requires 16 bytes of keying material. No implementation of SSLv2 ever followed this element of the specification; the code to omit this byte is shown in Listing C-19, but it's wrapped up in an #if 0 to retain compatibility with other SSLv2 implementations. Because the specification was never formally accepted by the IETF, the versions that don't follow it to the letter can't truly be said to be non-compliant; they had nothing to comply with.

Remember that the ssl_connect routine first invokes compute_keys and then send_client_master_key:

compute_keys( parameters );

if ( send_client_master_key( connection, parameters ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

compute_keys in Listing C-19 creates a master secret and then runs the MD5 digest algorithm on it to generate the encryption keys.

Listing C-19: "ssl.c" compute_keys

static void compute_keys( SSLParameters *parameters )

{

int i;

digest_ctx md5_digest;

int key_material_len;

unsigned char *key_material, *key_material_ptr;

char counter = '0';

key_material_len = parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size * 2;

key_material_ptr = key_material = malloc( key_material_len );

parameters->master_key = malloc(

parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size );

for ( i = 0; i < parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size; i++ )

{

// XXX should be random

parameters->master_key[ i ] = i;

}

// Technically wrong per the 1995 draft specification, but removed to

// maintain compatibility

#if 0

if ( key_material_len <= 16 )

{

counter = '\0'; // don't use the counter here

}

#endif

while ( key_material_len )

{

new_md5_digest( &md5_digest );

update_digest( &md5_digest, parameters->master_key, parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size ); if ( counter ) { update_digest( &md5_digest, &counter, 1 ); counter++; } update_digest( &md5_digest, parameters->challenge, CHALLENGE_LEN ); update_digest( &md5_digest, parameters->connection_id, parameters->connection_id_len ); finalize_digest( &md5_digest ); memcpy( key_material_ptr, md5_digest.hash, MD5_BYTE_SIZE ); key_material_ptr += MD5_BYTE_SIZE; key_material_len -= MD5_BYTE_SIZE; } parameters->read_key = malloc( parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size ); parameters->write_key = malloc( parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size ); memcpy( parameters->read_key, key_material, parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size ); memcpy( parameters->write_key, key_material + parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size, parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size ); parameters->read_iv = malloc( parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->IV_size ); parameters->write_iv = malloc( parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->IV_size ); for ( i = 0; i < parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->IV_size; i++ ) { // XXX these should be random parameters->read_iv[ i ] = i; parameters->write_iv[ i ] = i; } free( key_material ); }

First, figure out how much keying material you need: twice as much as the length of the key as specified in the cipher spec. Generate the master key, the same length as one key:

key_material_len = parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size * 2; key_material_ptr = key_material = malloc( key_material_len ); parameters->master_key = malloc(

parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size ); for ( i = 0; i < parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size; i++ ) { // XXX should be random parameters->master_key[ i ] = i; }

You need to store the master key because it is what is RSA encrypted and sent on to the server. Before you send it, though, go ahead and compute the keys themselves. The server needs to repeat the computation when it receives the RSA-encrypted master key:

while ( key_material_len )

{

new_md5_digest( &md5_digest );

update_digest( &md5_digest, parameters->master_key,

parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size );

if ( counter )

{

update_digest( &md5_digest, &counter, 1 );

counter++;

}

update_digest( &md5_digest, parameters->challenge, CHALLENGE_LEN );

update_digest( &md5_digest, parameters->connection_id,

parameters->connection_id_len );

finalize_digest( &md5_digest );

memcpy( key_material_ptr, md5_digest.hash, MD5_BYTE_SIZE );

key_material_ptr += MD5_BYTE_SIZE;

key_material_len -= MD5_BYTE_SIZE;

}

Depending on how much keying material you need, cycle through the loop one to three times, creating a new digest, updating and finalizing it each time. The key material is stored in the temporary buffer key_material.

Next, copy the key_material buffer's contents into the read/write keys:

parameters->read_key = malloc( parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size ); parameters->write_key = malloc( parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size ); memcpy( parameters->read_key, key_material, parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size ); memcpy( parameters->write_key, key_material + parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size, parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size );

Finally, generate the initialization vectors: parameters->read_iv = malloc( parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->IV_size ); parameters->write_iv = malloc( parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->IV_size ); for ( i = 0; i < parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->IV_size; i++ ) { // XXX these should be random parameters->read_iv[ i ] = i; parameters->write_iv[ i ] = i; }

Notice that these values are not related to the master key — they're transmitted directly (in cleartext) to the server. This is generally not a problem because an attacker still needs to have access to the key in order to make use of the values. In fact, SSLv3 and TLS 1.0 computed the IVs from the master secret rather than transmitting them, which was later discovered to be a minor security flaw and TLS 1.1+ went back to transmitting them in cleartext just as SSLv2 did. (Although the flaw was related to carrying CBC state from one packet to the next, which SSLv2 also does.)

RC4 does not make use of an initialization vector, but it does need to keep track of its state from one call to the next. Insert a special RC4-only clause in here to support this case. If you have other stream ciphers, you should do something similar for them:

memcpy( parameters->write_key, key_material +

parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size,

parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size );

// Compute IV's (or, for stream cipher, initialize state vector)

if ( parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->cipher_spec_code ==

SSL_CK_RC4_128_WITH_MD5 )

{

rc4_state *read_state = malloc( sizeof( rc4_state ) );

rc4_state *write_state = malloc( sizeof( rc4_state ) );

read_state->i = read_state->j = write_state->i = write_state->j = 0;

parameters->read_iv = NULL;

parameters->write_iv = NULL;

parameters->read_state = read_state;

parameters->write_state = write_state;

memset( read_state->S, '\0', RC4_STATE_ARRAY_LEN );

memset( write_state->S, '\0', RC4_STATE_ARRAY_LEN );

}

else

{

parameters->read_state = NULL;

parameters->write_state = NULL; parameters->read_iv = malloc( parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->IV_size ); parameters->write_iv = malloc( parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->IV_size ); for ( i = 0; i < parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->IV_size; i++ ) { // XXX these should be random parameters->read_iv[ i ] = i; parameters->write_iv[ i ] = i; } }

Now that you have generated the master key and computed the session keys, the client must send the client_master_key message shown in Listing C-20.

Listing C-20: "ssl.h" ClientMasterKey declaration

typedef struct

{

unsigned char cipher_kind[ 3 ];

unsigned short clear_key_len;

unsigned short encrypted_key_len;

unsigned short key_arg_len;

unsigned char *clear_key;

unsigned char *encrypted_key;

unsigned char *key_arg;

}

ClientMasterKey;

Note that the first element here is the cipher spec that has been chosen. In SSLv2, it's up to the client to select a cipher spec that both it and the server understand. It's important that this be transmitted at this point because the server needs to know how much key material to generate — that is, how many times to run the MD5 algorithm over the master key.

Three variable-length arguments follow the selected cipher spec. The clear_key, the encrypted_key, and the key_arg. Recall that SSLv2 specifically supports "export grade" ciphers such as RC4_128_EXPORT40. What this means is that 40 bits of the master key are encrypted and the other 88 bits are transmitted in cleartext. If the cipher spec calls for any unencrypted key material, the unencrypted bytes are transmitted in clear_key. This is the only difference between "export grade" and standard ciphers; the actual key is 128 bits (for example), but a potential attacker has 88 of them to start with.

The encrypted bytes are encrypted using the server's RSA key as described in Chapter 3. Finally, the key_arg is the optional area for the initialization vector.

The SSLv2 specification isn't clear on how many initialization vectors you should use. Should each side have its own initialization vector, or should the same one be used for both client and server? OpenSSL expects a single initialization vector that both sides start with (of course, they diverge immediately), so follow suit.

The send_client_master_key function is shown in Listing C-21.

Listing C-21: "ssl.c" send_client_master_key

static int send_client_master_key( int connection,

SSLParameters *parameters )

{

int status = 0;

unsigned char *send_buffer, *write_buffer;

int buf_len;

unsigned short network_number;

ClientMasterKey package;

memcpy( package.cipher_kind,

¶meters->proposed_cipher_spec->cipher_spec_code, 3 );

package.clear_key_len = 0; // not supporting export ciphers

package.encrypted_key_len = rsa_encrypt( parameters->master_key,

parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->key_size,

&package.encrypted_key, ¶meters->server_public_key );

package.key_arg_len = parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->IV_size;

package.clear_key = malloc( sizeof( unsigned char ) *

package.clear_key_len );

package.key_arg = malloc( sizeof( unsigned char ) *

package.key_arg_len );

memcpy( package.key_arg, parameters->read_iv,

parameters->proposed_cipher_spec->IV_size );

buf_len = sizeof( unsigned char ) * 3 +

sizeof( unsigned short ) * 3 +

package.clear_key_len +

package.encrypted_key_len +

package.key_arg_len;

send_buffer = write_buffer = malloc( buf_len );

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, package.cipher_kind, 3 );

network_number = htons( package.clear_key_len );

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer,

( void * ) &network_number, 2 );

network_number = htons( package.encrypted_key_len );

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer,

( void * ) &network_number, 2 );

network_number = htons( package.key_arg_len ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * ) &network_number, 2 ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, package.clear_key, package.clear_key_len ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, package.encrypted_key, package.encrypted_key_len ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, package.key_arg, package.key_arg_len ); status = send_handshake_message( connection, SSL_MT_CLIENT_MASTER_KEY, send_buffer, buf_len, parameters ); free( package.clear_key ); free( package.encrypted_key ); free( package.key_arg ); free( send_buffer ); return status; }

First fill out a ClientMasterKey struct, flatten it, and then send it as an SSL_MT_CLIENT_MASTER_KEY handshake message. Notice that clear_key is always 0 (no support for export-grade ciphers), and that rsa_encrypt, from Chapter 3, is invoked to encrypt the master key. Otherwise, this works just like the previous two handshake messages.

SSL Client Finished

As noted above, the specification makes it appear that the client should send client_finished before expecting the next message, a server_verify. Technically speaking, it doesn't really matter; neither of these two messages depends on the other. In general, the server sends the server_verify immediately without waiting for the client_finished, and the client sends client_finished without waiting for server verify, so these two messages can and do "pass" each other in transmit. Go ahead and follow the specification's advice and send the client finished before looking for the server verify.

ClientFinished is a pretty simple message, as shown in Listing C-22.

Listing C-22: "ssl.h" ClientFinished declaration

typedef struct

{

unsigned char *connection_id;

}

ClientFinished;

As you can see, it just reflects the connection_id back to the server.

However, what makes this a bit more complicated, and useful, is that the whole client_finished message — and every subsequent packet transmitted over this connection — should be encrypted with the newly negotiated session keys.

ssl_connect makes the "pending" cipher spec the active one:

parameters->active_cipher_spec = parameters->proposed_cipher_spec; parameters->proposed_cipher_spec = NULL;

Sending the client_finished method in Listing C-23 is straightforward.

Listing C-23: "ssl.c" send_client_finished

static int send_client_finished( int connection,

SSLParameters *parameters )

{

int status = 0;

unsigned char *send_buffer, *write_buffer;

int buf_len;

ClientFinished package;

package.connection_id = malloc( parameters->connection_id_len );

memcpy( package.connection_id, parameters->connection_id,

parameters->connection_id_len );

buf_len = parameters->connection_id_len;

write_buffer = send_buffer = malloc( buf_len );

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, package.connection_id,

parameters->connection_id_len );

status = send_handshake_message( connection, SSL_MT_CLIENT_FINISHED,

send_buffer, buf_len, parameters );

free( send_buffer );

free( package.connection_id );

return status;

}

There shouldn't be any surprises here. Fill in a structure, flatten it, and send it via send_handshake_message.

To actually support encryption, extend send_message in Listing C-24 to check to see if the active_cipher_spec parameter of the SSLParameters argument in non-null. If it is, it is used to encrypt and MAC the packet.

Listing C-24: "ssl.c" send_message with encryption support

if ( parameters->active_cipher_spec == NULL )

{

// TODO support three-byte headers (when encrypting) buf_len = data_len + 2; buffer = malloc( buf_len ); header_len = htons( data_len ); memcpy( buffer, &header_len, 2 ); buffer[ 0 ] |= 0x80; // indicate two-byte length memcpy( buffer + 2, data, data_len ); } else { int padding = 0; unsigned char *encrypted, *encrypt_buf, *mac_buf; if ( parameters->active_cipher_spec->block_size ) { padding = parameters->active_cipher_spec->block_size - ( data_len % parameters->active_cipher_spec->block_size ); } buf_len = 3 + // sizeof header parameters->active_cipher_spec->hash_size + // sizeof mac data_len + // sizeof data padding; // sizeof padding buffer = malloc( buf_len ); header_len = htons( buf_len - 3 ); memcpy( buffer, &header_len, 2 ); buffer[ 2 ] = padding; encrypt_buf = malloc( buf_len - 3 ); encrypted = malloc( buf_len - 3 ); memset( encrypt_buf, '\0', buf_len - 3 ); // Insert a MAC at the start of "encrypt_buf" mac_buf = malloc( data_len + padding ); memset( mac_buf, '\0', data_len + padding ); memcpy( mac_buf, data, data_len ); add_mac( encrypt_buf, mac_buf, data_len + padding, parameters ); free( mac_buf ); // Add the data (padding was already set to zeros) memcpy( encrypt_buf + parameters->active_cipher_spec->hash_size, data, data_len ); // Finally encrypt the whole thing parameters->active_cipher_spec->bulk_encrypt( encrypt_buf, buf_len - 3, encrypted, parameters->write_state ? parameters->write_state : parameters->write_iv, parameters->write_key ); memcpy( buffer + 3, encrypted, buf_len - 3 );

free( encrypt_buf ); free( encrypted ); } if ( send( connection, ( void * ) buffer, buf_len, 0 ) < buf_len ) { return −1; } parameters->write_sequence_number++; free( buffer ); }

As you can see, the bulk of send_message is now handling encryption. Check to see if the active cipher spec requires that the message be padded to a certain multiple:

if ( parameters->active_cipher_spec->block_size )

{

padding = parameters->active_cipher_spec->block_size -

( data_len % parameters->active_cipher_spec->block_size );

}

In practice, block_size is always either 8 (for DES or 3DES) or 0 (for RC4).

Next, allocate enough space for the SSLv2 header, which now is three bytes instead of two, the MAC, the data itself, and the padding.

buf_len = 3 + // sizeof header

parameters->active_cipher_spec->hash_size + // sizeof mac

data_len + // sizeof data

padding; // sizeof padding

buffer = malloc( buf_len );

header_len = htons( buf_len - 3 );

memcpy( buffer, &header_len, 2 );

buffer[ 2 ] = padding;

encrypt_buf = malloc( buf_len - 3 );

encrypted = malloc( buf_len - 3 );

memset( encrypt_buf, '\0', buf_len - 3 );

Notice the allocation of two buffers. buffer is the memory array that is actually sent over the connection. This is where the three-byte header is passed. Actually, the first two bytes are the length of the message, just as they were in the two-byte header. The third byte encodes the amount of padding on the end of the message, which is required to be present even if the cipher spec is a stream cipher.

NOTE Technically, this code is wrong. The next-to-most-significant bit in a three-byte header is reserved; if bit 6 is set to 1, then the message should be treated as a "security escape." What this might mean and what you might do when such a message is received has never been defined, so you don't have to worry about it. However, technically you ought to ensure that the size of the outgoing packet is never greater than 2^14 = 16,384 bytes.

The second buffer, encrypted, is the buffer that's passed into the bulk encryption routine. You may wonder why another buffer is needed for this purpose. After all, the input parameter data is the plaintext to be encrypted. Well, SSLv2 requires that you prepend this data with a MAC and then encrypt the whole thing.

So, the next thing to do is to generate the MAC in the first mac-length bytes of the encrypt buffer.

mac_buf = malloc( data_len + padding ); memset( mac_buf, '\0', data_len + padding ); memcpy( mac_buf, data, data_len ); add_mac( encrypt_buf, mac_buf, data_len + padding, parameters ); free( mac_buf );

As you can see, another buffer is used to MAC the data to be sent; this includes the plaintext data, plus the padding (the padding must be MAC'ed). Invoke add_mac in Listing C-25 to actually generate the MAC.

Listing C-25: "ssl.c" add_mac

static void add_mac( unsigned char *target,

const unsigned char *src,

int src_len,

SSLParameters *parameters )

{

digest_ctx ctx;

int sequence_number;

parameters->active_cipher_spec->new_digest( &ctx );

update_digest( &ctx, parameters->write_key,

parameters->active_cipher_spec->key_size );

update_digest( &ctx, src, src_len );

sequence_number = htonl( parameters->write_sequence_number );

update_digest( &ctx, ( unsigned char * ) &sequence_number,

sizeof( int ) );

finalize_digest( &ctx );

memcpy( target, ctx.hash,

parameters->active_cipher_spec->hash_size );

}

Notice that SSLv2 does not use the HMAC function. HMAC wasn't actually specified until 1997. Instead, SSLv2 uses a slightly weaker form that concatenates the write secret, the data, and a sequence number, and then securely hashes this combination of things.

Getting back to send_message, you have a data buffer with the MAC of the plaintext data. Now, from the data pointer that was passed into the function in the first place, copy the actual plaintext after it and encrypt the whole thing into the target buffer.

// Add the data (padding was already set to zeros)

memcpy( encrypt_buf + parameters->active_cipher_spec->hash_size,

data, data_len );

// Finally encrypt the whole thing

parameters->active_cipher_spec->bulk_encrypt( encrypt_buf,

buf_len - 3, encrypted,

parameters->write_state ? parameters->write_state :

parameters->write_iv,

parameters->write_key );

Now, the encrypted buffer contains the MAC, the plaintext, and the padding, all encrypted using the client write key. Finally, copy the encrypted data into the target buffer:

memcpy( buffer + 3, encrypted, buf_len - 3 ); free( encrypt_buf ); free( encrypted ); }

The only other addition to send_message is the following, which updates the sequence number upon which the add_mac function relies:

parameters->write_sequence_number++;

The server receives this encrypted message, decrypts it using the negotiated keys, and verifies the MAC. If decryption and MAC verification succeed, the server finally verifies that the connection ID received matches the one that it sent.

What if any of these steps fail? The specification states that a MAC verify or decrypt error "is to be treated as if an 'I/O Error' had occurred (i.e. an unrecoverable error is asserted and the connection is closed)." However, it doesn't define any unrecoverable (or recoverable, for that matter) error codes describing this scenario. As a result, all existing implementations simply shut down the socket on error.

SSL Server Verify

As discussed earlier, OpenSSL goes ahead and sends the server_verify as soon as the key exchange is complete, although the specification suggests that it should wait until the client_finished is received correctly. The ServerVerify message in Listing C-26 looks just like, and serves the same purpose as, the client finished message.

Listing C-26: "ssl.h" ServerVerify declaration

typedef struct { unsigned char challenge[ CHALLENGE_LEN ]; } ServerVerify;

NOTE There's also a server finished message that is not analogous to the client finished.

Here the server MACs, encrypts, and reflects back the client's challenge token. The client must verify that it can be decrypted, verified, and that it matches what the client sent initially. As discussed earlier, if anything goes wrong, no specific error code is sent. The connection is just closed.

After sending client_finished, ssl_connect starts looking for server_verify:

while ( !parameters->got_server_verify )

{

if ( receive_ssl_message( connection, NULL, 0, parameters ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

}

Of course, because the key exchange has been completed, this message is encrypted. You can still invoke receive_ssl_message here, but it has to be extended to handle encrypted incoming messages.

First of all, recognize and process the three-byte lengths described in the previous section as shown in Listing C-27.

Listing C-27: "ssl.c" receive_ssl_message with encryption support

unsigned char padding_len = 0;

...

if ( message_len & 0x8000 )

{

// two-byte length

message_len &= 0x7FFF;

}

else

{

// three-byte length, include a padding value

if ( recv( connection, &padding_len, 1, 0 ) <= 0 )

{

return −1;

}

}

As you may recall from the previous section, the first two bytes are the length of the payload, and the third byte is the length of the padding (if any).

Next, check to see if a cipher spec is active and if so, apply it:

bufptr += bytes_read;

remaining -= bytes_read;

}

// Decrypt if a cipher spec is active

if ( parameters->active_cipher_spec != NULL )

{

unsigned char *decrypted = malloc( message_len );

int mac_len = parameters->active_cipher_spec->hash_size;

parameters->active_cipher_spec->bulk_decrypt( buffer, message_len,

decrypted,

parameters->read_state ? parameters->read_state :

parameters->read_iv,

parameters->read_key );

if ( !verify_mac( decrypted + mac_len, message_len - mac_len,

decrypted, mac_len, parameters ) )

{

return −1;

}

free( buffer );

buffer = malloc( message_len - mac_len - padding_len );

memcpy( buffer, decrypted + mac_len,

message_len - mac_len - padding_len );

message_len = message_len - mac_len, padding_len;

free( decrypted );

}

parameters->read_sequence_number++;

This more or less parallels the changes made to send_message, in Listing C-24. First allocate a decrypted buffer and decrypt the whole packet into it. Next, the MAC is verified in Listing C-28.

Listing C-28: "ssl.c" verify_mac

static int verify_mac( const unsigned char *data,

int data_len,

const unsigned char *mac,

int mac_len,

SSLParameters *parameters )

{

digest_ctx ctx;

int sequence_number;

parameters->active_cipher_spec->new_digest( &ctx ); update_digest( &ctx, parameters->read_key, parameters->active_cipher_spec->key_size ); update_digest( &ctx, data, data_len ); sequence_number = htonl( parameters->read_sequence_number ); update_digest( &ctx, ( unsigned char * ) &sequence_number, sizeof( int ) ); finalize_digest( &ctx ); return ( !memcmp( ctx.hash, mac, mac_len ) ); }

This works just like add_mac. In fact, the only differences here are that it uses the read_key as the first n bytes of the MAC buffer, and rather than memcpy-ing the resultant MAC to a target output buffer, it instead does a memcmp and returns a true or false.

If the MAC verifies properly, the decrypted data is copied into a target buffer and processed just as if it had been received as plaintext. Add a third "case arm" to the handshake processing switch:

if ( !parameters->handshake_finished )

{

switch ( buffer[ 0 ] )

{

...

case SSL_MT_SERVER_VERIFY:

status = parse_server_verify( parameters, buffer + 1 );

break;

Parsing the ServerVerify, after it's been successfully decrypted, is straightforward, as shown in Listing C-29.

Listing C-29: "ssl.c" parse_server_verify

static int parse_server_verify( SSLParameters *parameters,

const unsigned char *buf )

{

ServerVerify package;

memcpy( package.challenge, buf, CHALLENGE_LEN );

parameters->got_server_verify = 1;

return ( !memcmp( parameters->challenge, package.challenge,

CHALLENGE_LEN ) );

}

Compare the challenge token sent back by the server with the challenge token sent in the "hello" message, and return an error code if they don't match. If the two tokens don't match, this error code is a signal to the outer function to close the socket.

SSL Server Finished

At this point, the secure channel has been all but negotiated. The only thing remaining is the server_finished message. This also has only one field in Listing C-30.

Listing C-30: "ssl.h" ServerFinished declaration

typedef struct

{

unsigned char *session_id;

}

ServerFinished;

This is the session ID, chosen by the server, that can be passed in a later client_hello message to resume this session.

The ssl_connect function waits until this is received and, after it has been, marks the handshake as complete:

while ( !parameters->got_server_finished )

{

if ( receive_ssl_message( connection, NULL, 0, parameters ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

}

parameters->handshake_finished = 1;

Server finished is the final case arm in receive_ssl_message's handshake switch:

if ( !parameters->handshake_finished )

{

switch ( buffer[ 0 ] )

{

...

case SSL_MT_SERVER_FINISHED:

status = parse_server_finished( parameters, buffer + 1,

message_len );

break;

For this implementation, parse_server_finished in Listing C-31 is a formality because the session ID isn't stored anywhere.

Listing C-31: "ssl.c" parse_server_finished

static int parse_server_finished( SSLParameters *parameters, const unsigned char *buf, int buf_len ) { ServerFinished package; package.session_id = malloc( buf_len - 1 ); memcpy( package.session_id, buf, buf_len - 1 ); parameters->got_server_finished = 1; free( package.session_id ); return 0; }

At this point, ssl_connect returns with a successful status code, and the calling code continues processing as if no SSL handshake had been performed. The only difference, as shown earlier, is that instead of calling the socket-layer send and recv messages, it instead calls ssl_send and ssl_recv.

SSL send

ssl_send in Listing C-32 is a pretty simple function.

Listing C-32: "ssl.c" ssl_send

int ssl_send( int connection, const char *application_data, int length,

int options, SSLParameters *parameters )

{

return ( send_message( connection, application_data, length,

parameters ) );

}

All of the heavy lifting is done by the send_message function. If a key exchange has been successfully performed on the socket identified by connection, send_message pads, MAC's, and encrypts the application_data.

SSL recv

ssl_recv in Listing C-33 is just as simple.

Listing C-33: "ssl.c" ssl_recv

int ssl_recv( int connection, char *target_buffer, int buffer_size,

int options, SSLParameters *parameters )

{

return receive_ssl_message( connection, target_buffer,

buffer_size, parameters );

}

However, because an SSL packet can be up to 16,384 bytes in length, either the caller should always supply a buffer of this length, or ssl_recv needs to deal with the case where the input buffer is smaller than the SSL packet. This means that it needs to remember what was left over but not read and passes that back to the caller on the next ssl_recv.

if ( !parameters->handshake_finished )

{

...

}

else

{

// If the handshake is finished, the app should be expecting data;

// return it

if ( message_len > target_bufsz )

{

memcpy( target_buffer, buffer, target_bufsz );

status = target_bufsz;

// Store the remaining data so that the next "read" call just

// picks it up

parameters->unread_length = message_len - target_bufsz;

parameters->unread_buffer = malloc( parameters->unread_length );

memcpy( parameters->unread_buffer, buffer + target_bufsz,

parameters->unread_length );

}

else

{

memcpy( target_buffer, buffer, message_len );

status = message_len;

}

}

Finally, near the top of ssl_recv, check to see if there was any unread data from the previous call:

if ( parameters->unread_length )

{

buffer = parameters->unread_buffer;

message_len = parameters->unread_length;

parameters->unread_buffer = NULL;

parameters->unread_length = 0;

}

else

{

// New message - read the length first

if ( read( connection, &message_len, 2, 0 ) <= 0 )

{

return −1;

SSLv2 didn't give any special treatment to connection closing as SSLv3 did, so closing the socket requires no special processing.

Examining an HTTPS End-to-End Example

I'm sure you'd like to see this code in action. It's very unlikely that you can find a public website that accepts an SSLv2 connection, so if you want to see this code run you have to start a server locally. You can do this with OpenSSL; it has a built-in s_server command that is designed specifically to test implementations. You need to supply a path to a certificate and the corresponding private key; Chapter 5 discusses how to generate these.

On the command line, run

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ openssl s_server -accept 8443 -cert cert.pem \ -key key.pem Enter pass phrase for key.pem: Using default temp DH parameters ACCEPT

Now, run the https application developed in this appendix:

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./https https://localhost:8443/index.html Connecting to host 'localhost' on port 8443 Connection complete; negotiating SSL parameters Retrieving document: 'index.html' sending: GET /index.html HTTP/1.1 Displaying Response... data: HTTP/1.0 200 ok Content-type: text/html <HTML><BODY BGCOLOR="#ffffff"> <pre> s_server -accept 8443 -cert cert.pem -key key.pem -www Ciphers supported in s_server binary ...

Viewing the TCPDump Output

To see what's going on beneath the hood, you can run the tcpdump application while you run the https application. You need to make sure to listen on the "loopback" interface because you're running both client and server on your localhost. If you listen on your actual Ethernet card, you won't see any traffic.

With tcpdump enabled, if you re-run the https command again, you see something like this:

[root@localhost ssl]# /usr/sbin/tcpdump -s 0 -x -i lo tcp port 8443 listening on lo, link-type EN10MB (Ethernet), capture size 65535 bytes

15:57:38.845640 IP localhost.localdomain.50704 > localhost.localdomain.pcsync-https: S 2610069118:2610069118(0) win 32792 <mss 16396,sackOK,timestamp 24215142 0,nop,wscale 7> 0x0000: 4500 003c 0018 4000 4006 3ca2 7f00 0001 0x0010: 7f00 0001 c610 20fb 9b92 7e7e 0000 0000 0x0020: a002 8018 0e99 0000 0204 400c 0402 080a 0x0030: 0171 7e66 0000 0000 0103 0307 ...

Recall however that the HTTPS protocol (but not necessarily SSL!) mandates that the very first packet sent after the connection is established must be an SSL ClientHello. The next packet, therefore, is

15:57:38.846983 IP localhost.localdomain.50704 >

localhost.localdomain.pcsync-https: P 1:37(36)

ack 1 win 257 <nop,nop,timestamp 24215144 24215142>

0x0000: 4500 0058 001a 4000 4006 3c84 7f00 0001

0x0010: 7f00 0001 c610 20fb 9b92 7e7f 9bb0 f1f9

0x0020: 8018 0101 fe4c 0000 0101 080a 0171 7e68

0x0030: 0171 7e66 8022 0100 0200 0900 0000 1006

0x0040: 0040 0100 8007 00c0 0001 0203 0405 0607

0x0050: 0809 0a0b 0c0d 0e0f

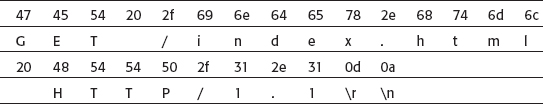

The TCP header ends at byte 0x0034, so the SSL data begins at 0x0035. If you refer to the specification for the ClientHello, you see that it starts with a version major and a version minor byte. However, this is preceded by a two-byte length field with the high-bit set to "1" to indicate that this is a two-, rather than three-, byte header. Removing the high-bit, you get a length of 34 bytes (0x22 = 34 base 10), which you can see matches the packet length. This is followed by the handshake type, a one-byte 0x01, which is the code for ClientHello. The receiver is responsible for keeping track of the fact that this is a new connection, and that a handshake message is expected.

The length header is followed by the ClientHello packet:

unsigned char version_major; // 00 unsigned char version_minor; // 02 unsigned short cipher_specs_length; // 0009 unsigned short session_id_length; // 0000 unsigned short challenge_length; // 0010 unsigned char *cipher_specs; // 0600400100800700c0 unsigned char *session_id; // (empty) unsigned char *challenge; // 000102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f

You can compare this to the data that was loaded in the send_client_hello function; remember that the challenge, which actually ought to be a random number, is just an increasing sequence of bytes.

The server responds with its own hello, where it informs the client which ciphers it supports, and provides a public key, wrapped up in an X.509 certificate.

15:57:38.847302 IP localhost.localdomain.pcsync-https >

localhost.localdomain.50704: P 1:893(892) ack 37 win 256

<nop,nop,timestamp 24215144 24215144>

0x0000: 4500 03b0 8fa0 4000 4006 a9a5 7f00 0001

0x0010: 7f00 0001 20fb c610 9bb0 f1f9 9b92 7ea3

0x0020: 8018 0100 01a5 0000 0101 080a 0171 7e68

0x0030: 0171 7e68 837a 0400 0100 0203 5600 0900

0x0040: 1030 8203 5230 8202 fca0 0302 0102 0209

0x0050: 00c7 5c9d eade c1a2 5030 0d06 092a 8648

0x0060: 86f7 0d01 0105 0500 3081 a431 0b30 0906

0x0070: 0355 0406 1302 5553 310e 300c 0603 5504

0x0080: 0813 0554 6578 6173 3112 3010 0603 5504

0x0090: 0713 0953 6f75 7468 6c61 6b65 3114 3012

0x00a0: 0603 5504 0a13 0b54 7261 7665 6c6f 6369

0x00b0: 7479 3115 3013 0603 5504 0b13 0c41 7263

....

0x0380: bd17 59e8 3508 bd6a 9554 96ed 9790 66ec

0x0390: c2a8 eca0 8c6a b706 0040 0100 8007 00c0

0x03a0: b73b 8d2a 4c35 192b f6ff e87b 0137 8772

The length of this packet is 0x037A = 890 bytes; because the ServerHello packet includes the certificate, it's going to be fairly long. The type is 0x04, ServerHello. This is followed by the ServerHello packet:

unsigned char session_id_hit; // 00

unsigned char certificate_type; // 01 = SSL_CT_X509_CERTIFICATE

unsigned char server_version_major; // 00

unsigned char server_version_minor; // 02

unsigned short certificate_length; // 0356

unsigned short cipher_specs_length; // 0009

unsigned short connection_id_length; // 0010

signed_x509_certificate certificate; // (an entire DER-encoded X.509

// certificate)

unsigned char *cipher_specs; // 0600400100800700c0

unsigned char *connection_id; // b73b8d2a4c35192bf6ffe87b01378772

The next packet is the client's master key message. The client selects a cipher spec from the ones presented by the server, generates a master key, encrypts it using the public key presented by the server, and sends it back:

15:57:38.915469 IP localhost.localdomain.50704 >

localhost.localdomain.pcsync-https: P 37:121(84) ack 893

win 271 <nop,nop,timestamp 24215212 24215144>

0x0000: 4500 0088 001c 4000 4006 3c52 7f00 0001

0x0010: 7f00 0001 c610 20fb 9b92 7ea3 9bb0 f575

0x0020: 8018 010f fe7c 0000 0101 080a 0171 7eac

0x0030: 0171 7e68 8052 0206 0040 0000 0040 0008 0x0040: 8b78 24fb 8643 724b c052 5b9d 7460 ad16 0x0050: ea68 5b82 70fe 138c 9701 8261 1ec7 055f 0x0060: 7a0b ecd9 8f25 008d 62c4 f8db 8bf5 6029 0x0070: e797 1138 8b26 3c43 d889 164d 55fd cd22 0x0080: 0001 0203 0405 0607

Again, the length of the packet is 0x0052 = 82 bytes, and the message type is 0x02 = SSL_MT_CLIENT_MASTER_KEY.

unsigned char cipher_kind[ 3 ]; // 060040 =

// SSL_CK_DES_64_CBC_WITH_MD5

unsigned short clear_key_len; // 0000 (no cleartext key,

// not an export cipher)

unsigned short encrypted_key_len; // 0040

unsigned short key_arg_len; // 0008 (8 bytes of IV)

unsigned char *clear_key; // (empty)

unsigned char *encrypted_key; // 8b7824fb8643724bc0525b9d7460ad16

// ea685b8270fe138c970182611ec7055f

// 7a0becd98f25008d62c4f8db8bf56029

// e79711388b263c43d889164d55fdcd22

unsigned char *key_arg; // 0001020304050607

To decrypt this, you need the private key, of course. Refer to Chapter 5 to see how to extract it from "key.pem" if you've forgotten. You can then use the rsa utility developed in Chapter 3 to decrypt this and verify that it is, indeed, the master key that was generated:

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./rsa -d \ 0xB8C4AB64DF20DCECB49C02ACECEA1B832742550267762E4CBE39EC3A0657E779A71\ 2B9DE5048313CFDE01DFDACD12E999082E08FC3FFFFABA0816E3C54337AFF \ 0x1DCD8343DB05C6FCDB490AD96FC1773C99798692C3B37956619CA030DFD30FFFF601\ CEE22444C1E32C9E89B37EB8C76AC9E49FA52C3AB463306A067C05B4B1B9 \ 0x8b7824fb8643724bc0525b9d7460ad16ea685b8270fe138c970182611ec7055f7a0be\ cd98f25008d62c4f8db8bf56029e79711388b263c43d889164d55fdcd22 02 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 0a 0b 0c 0d 0e 0f 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 1a 1b 1c 1d 1e 1f 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 2a 2b 2c 2d 2e 2f 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 00 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 00 0001020304050607

Recall from Listing C-19 that 0001020304050607 is, in fact, the generated master key. At this point, the key exchange is complete, and every subsequent packet is encrypted using the chosen cipher.

Both sides now compute symmetric encryption keys. Remember that, in SSLv2, this is done by running the MD5 algorithm against the master key, the counter "0", the client's challenge, and the server's connection ID. You can see that this works out to

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./digest -md5 \ 0x000102030405060730000102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f\ b73b8d2a4c35192bf6ffe87b01378772 14f258c2fe6bf291b84ce9aeebc6d4d8

| Master Key | 0001020304050607 |

| ASCII Zero | 30 |

| Challenge | 000102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f |

| Connection Id | b73b8d2a4c35192bf6ffe87b01378772 |

| Read Key | 14f258c2fe6bf291 |

| Write Key | b84ce9aeebc6d4d8 |

According to the specification, the client should next respond with a client_finished message, but OpenSSL jumps the gun and sends its own server_verify. Because neither is dependent on the other, it doesn't matter what order they are received in:

15:57:38.916066 IP localhost.localdomain.pcsync-https >

localhost.localdomain.50704: P 893:936(43) ack 121

win 256 <nop,nop,timestamp 24215213 24215212>

0x0000: 4500 005f 8fa1 4000 4006 acf5 7f00 0001

0x0010: 7f00 0001 20fb c610 9bb0 f575 9b92 7ef7

0x0020: 8018 0100 fe53 0000 0101 080a 0171 7ead

0x0030: 0171 7eac 0028 0777 76d1 5c1e 94b1 d24d

0x0040: a349 b24c b342 af66 537b 0b19 154b 6daf

0x0050: 2a36 064c a459 53b4 5c55 7c70 509a 14

However, the connection is now encrypted. A passive observer could follow along until this point, but without access to the keys — either the server's private key or the negotiated symmetric keys — he would be unable to figure out what the contents of this packet were, or even what type it is. You can decrypt it, though, because you know the keys. The first three bytes are sent in plain text; they are the length of the packet (0x0028), and the length of the padding (0x07). The rest is DES encrypted:

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./des -d 0x14f258c2fe6bf291 \ 0x0001020304050607 \ 0x7776d15c1e94b1d24da349b24cb342af66537b0b19154b6daf\ 2a36064ca45953b45c557c70509a14490d1f61abaf26ace8326d\ baa79b5f2805000102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f00000000000000

You can see the seven bytes of padding, which should be removed:

490d1f61abaf26ace8326dbaa79b5f2805000102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f

Recall that every packet is prefixed with a 16-byte MD5 hash of the key, the data, the padding, and a sequence number (which starts at 1). You can verify the hash:

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./digest -md5 \ 0x14f258c2fe6bf2910500010203040506070809\ 0a0b0c0d0e0f0000000000000000000001 490d1f61abaf26ace8326dbaa79b5f28

| Read Key | 14f258c2fe6bf291 |