CHAPTER 8

Advanced SSL Topics

The prior two chapters examined the TLS handshake process in detail, walking through each message that each side must send and receive. So far, you've looked at the most common use of SSL/TLS—a server-authenticated RSA key exchange. However, there are actually quite a few more options available to the user when performing a TLS handshake. Some potential scenarios are simpler, and some are more complex than those presented so far—it's possible to connect without authenticating the server, or to force the client to authenticate itself, or to employ different key exchange mechanisms. It's even possible to bypass the handshake completely, if secure parameters have already been negotiated. This chapter looks at the less common—or not strictly required—but still important aspects of the TLS handshake.

Passing Additional Information with Client Hello Extensions

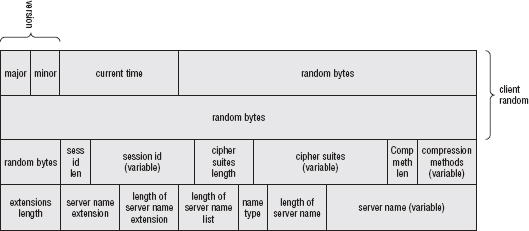

Peek back to the definition of the handshake messages defined in Chapter 6. Although each one is prepended with a length, most of them—with the exception of the certificate message—have lengths that are fixed or that can easily be inferred from their structure. The client hello message, for instance, is a fixed two bytes of version information, 32 bytes of random data, and three variable-length structures each of which includes their length. The receiver can easily figure out where the record ends without being given an explicit length.

So, why restate the length? Well, the designers of the protocol anticipated, correctly, that they might not have covered all the bases when they described the handshake, so they allowed extra data to be appended to the client hello handshake message. This is the reason why the code in the last chapter handles the parsing of client hello messages differently than all the other messages. In fact, if you tried using TCPdump to sniff your own browser's traffic, you probably noticed some of these extensions in its client hello messages. The TLS protocol designers didn't, however, specify what form these extensions should take. This wasn't actually standardized until years later, when RFC 3546 was drafted.

One of the most important of these standardized extensions is the server name identification (SNI) extension. It's common in today's Internet for low-traffic websites to share a hosting provider. There's no particular reason why a blog that gets a few hundred hits a day needs a dedicated server; it can share bandwidth (and costs) with several other sites on a single host. However, this can pose problems for TLS. Each physical server on the Internet has its own IP address, even if that physical host maps to multiple domains. So, for instance, if a shared hosting provider had three hosts named www.hardware.com, www.books.com, and www.computers.com, all hosted from a single physical server, each one would resolve to the same IP address.

This doesn't seem like a problem for TLS until you consider that TLS must send a certificate whose domain name matches the requested domain name to avoid the man-in-the-middle attack described in Chapter 5. However, TLS doesn't know what domain was requested. Domain names are for people; computers deal in IP addresses. Therefore, the client has to have some way to notify the server that it should present the certificate for www.books.com rather than the certificate for www.computers.com; wildcard certificates don't help here, because it's specifically prohibited to generate a wildcard of the form *.com—for obvious reasons.

Therefore, the client is optionally permitted to indicate with a client hello extension the name of the host it's trying to connect to, and all modern browsers do this. It's easy to add client hello extension parsing to the parse_client_hello routine from Listing 7-9 as shown in Listing 8-1.

Listing 8-1: "tls.c" parse_client_hello with client hello extension support

static char *parse_client_hello( char *read_pos,

int pdu_length,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

char *init_pos;

init_pos = read_pos; // keep track of start to check for extensions

... free( hello.session_id ); } // Parse client hello extensions if ( ( read_pos - init_pos ) < pdu_length ) { read_pos = parse_client_hello_extensions( read_pos, parameters ); } return read_pos; }

Client hello extensions are, of course, a list of extensions; like every other variable-length list in TLS, the extensions list is preceded by the byte count (not the item count!) of the list that follows. The extensions themselves are as open-ended as possible; each starts with a two-byte extension identifier and another variable-length blob of data whose contents depend on the extension identifier. The interpretation of this blob varies greatly from one extension to the next. In many cases, it's yet another variable-length list of data, but in other cases it's a simple numeric type, and sometimes it's empty if the extension is just a marker that indicates that a certain feature is supported.

This book won't exhaustively cover all the available client hello extensions. Of those that are covered, most are discussed as they come up rather than in this section. They'll make more sense that way. However, Listings 8-2 and 8-3 illustrate the parsing of the server name extension:

Listing 8-2: "tls.c" parse_client_hello_extensions

typedef enum

{

server_name = 0

}

ExtensionType;

static char *parse_client_hello_extensions( char *read_pos,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

unsigned short extensions_size, extension_data_size;

char *init_pos;

ExtensionType type;

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &extensions_size, ( void * ) read_pos, 2 );

extensions_size = ntohs( extensions_size );

init_pos = read_pos;

while ( ( read_pos - init_pos ) < extensions_size )

{ read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &type, ( void * ) read_pos, 2 ); read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &extension_data_size, ( void * ) read_pos, 2 ); type = ntohs( type ); extension_data_size = ntohs( extension_data_size ); switch ( type ) { case server_name: parse_server_name_extension( read_pos, extension_data_size, parameters ); printf( "Got server name extension\n" ); break; default: printf( "warning, skipping unsupported client hello extension %d\n", type ); break; } read_pos += extension_data_size; } return read_pos; }

Listing 8-3: "tls.c" parse_server_name_extension

typedef enum

{

host_name = 0

}

NameType;

static void parse_server_name_extension( unsigned char *data,

unsigned short data_len,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

unsigned short server_name_list_len;

unsigned char name_type;

unsigned char *data_start;

data = read_buffer( ( void * ) &server_name_list_len, ( void * ) data, 2 );

server_name_list_len = ntohs( server_name_list_len );

data_start = data;

data = read_buffer( ( void * ) &name_type, ( void * ) data, 1 );

switch ( name_type )

{

case host_name:

{ unsigned short host_name_len; unsigned char *host_name; data = read_buffer( ( void * ) &host_name_len, ( void * ) data, 2 ); host_name_len = ntohs( host_name_len ); host_name = malloc( host_name_len + 1 ); data = read_buffer( ( void * ) host_name, ( void * ) data, host_name_len ); host_name[ host_name_len ] = '\0'; printf( "got host name '%s'\n", host_name ); // TODO store this and use it to select a certificate // TODO return an "unrecognized_name" alert if the host name // is unknown free( host_name ); } break; default: // nothing else defined by the spec break; } }

As you can see from these listings, there's nothing particularly different about the server name extension—it's a triply-nested list. Each list is prepended with a two-byte length that needs to be converted from network order to host order before the list can be processed, as usual. A client hello with a server name extension is illustrated in Figure 8-1. Compare this to the plain client hello in Figure 6-2.

Figure 8-1: Client Hello with SNI

Strangely, the server name extension itself allows for a list of host names. It's not clear how the server ought to behave if one of the names was recognized, but another wasn't, or if both were recognized and correspond, for example, to available certificates. Prefer the first? Prefer the last? I know of no TLS client that supports SNI but also sends more than one host name. OpenSSL, reasonably enough, regards it as an error if you pass more than one (prior to version 1.0, though, OpenSSL just ignores this).

The implementation presented in this book is only capable of sending one certificate, so all this code does is print out the host name it receives from the client and throws away the negotiated server name. A more robust implementation would, of course, keep track of this. If the server recognized, accepted, and understood the server name extension, it should include an empty server-name extension in its own hello message, to let the client know that the extension was recognized. This might prompt the client, for instance, to tighten its security requirements if the received certificate was invalid. Of course, this wouldn't be useful against a malicious server, but might expose an innocently misconfigured one.

There are quite a few other extensions defined; RFC 3546 defines six, and there are several others that are fairly common and are examined later.

Safely Reusing Key Material with Session Resumption

Recall in Chapter 6 that the server was responsible for assigning a unique session ID to each TLS connection. However, if you browse through the remainder of the handshake, that session ID is never used again. Why does the server generate it, then?

SSL, since v2, has always supported session resumption. Remember that SSL was originally conceived as an HTTP add-on; it was only later retrofitted to other protocols. It was also designed back when HTTP 1.0 was state-of-the-art, and HTTP 1.0 required the web client—the browser—to close the socket connection to indicate the end of request. This meant that a lot of HTTP requests needed to be made for even a single web page. Although this was corrected somewhat in HTTP 1.1 with pipelining of requests/keepalives, the fact still remains that HTTP has a very low data-to-socket ratio. Add the time it takes to do a key exchange and the corresponding private key operations, and SSL can end up being a major drain on the throughput of the system.

To get a handle on this, SSL, and TLS, allow keying material to be reused across multiple sockets. This works by passing an old session ID in the client hello message and short-circuiting the handshake. This allows the lifetime of the SSL session—the keying material that's used to protect the data—to be independent of the lifetime of the socket. Regardless of the protocol used, this is a good thing. After a 128-bit key has been successfully negotiated, depending on the cipher spec, it can be used to protect potentially hundreds of thousands of bytes of content. There's no reason to throw away these carefully negotiated keys just because the top-level protocol itself has ended.

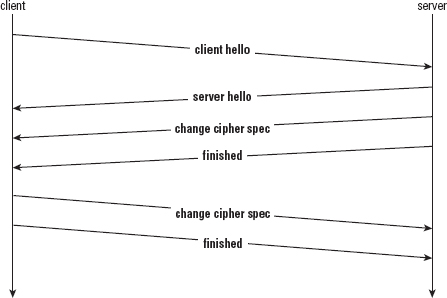

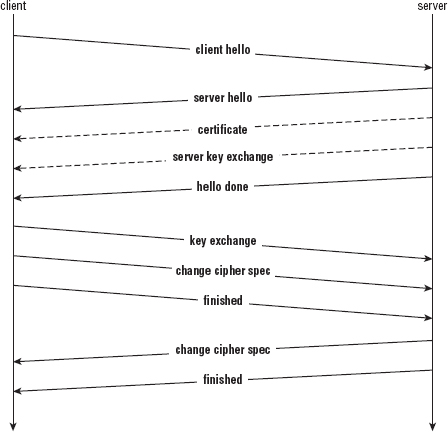

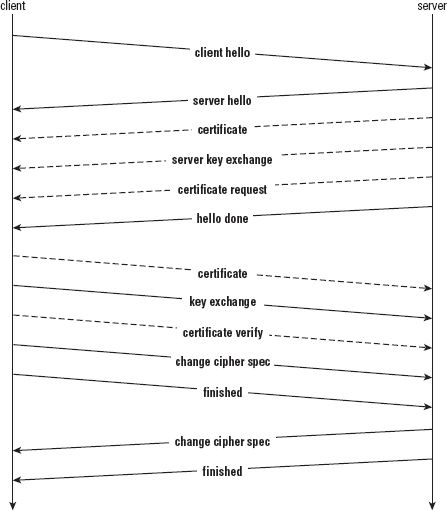

Figure 8-2 shows that the certificate, hello done, and key exchange messages have all been elided. Because the client and the server have already negotiated a master secret, there's no reason to resend these parameters.

Figure 8-2: Shortened session resumption handshake sequence

Interestingly, when the handshake is shortened for session resumption, the server sends the finished message first, whereas for a normal handshake as shown back in Figure 6-1, it's the client. This is a nod to efficiency: The server needn't wait for the client to send a key exchange before it computes its finished message, so it can go ahead and pipeline all three of its messages in a single burst if the server is willing to renegotiate.

Adding Session Resumption on the Client Side

What if the server isn't willing to renegotiate? According to the specification, the server should go ahead and silently begin a new handshake, and send its certificate and hello done message. It's technically up to the client if it wants to abort at this point, or go ahead and just negotiate a new session. In most cases, the client wants to continue anyway. It's hard to imagine a scenario where a client wouldn't want to negotiate a new session in this case. All TLS-based software that I'm familiar with automatically does so, without prompting or notifying the user. It's possible, though, that some particularly security-conscious (say, military) software somewhere may say, "Hey, you gave me this session ID two minutes ago, and now you're not willing to resume it? Something's wrong here, I'm bailing," and notify the user to investigate what could possibly be a security breach.

Requesting Session Resumption

To add session resumption to the TLS client from Chapter 6, modify the TLSParameters structure from Listing 6-5 to include an optional session ID as shown in Listing 8-4:

Listing 8-4: "tls.h" TLSParameters with session ID

#define MAX_SESSION_ID_LENGTH 32

typedef struct

{

...

int session_id_length;

unsigned char session_id[ MAX_SESSION_ID_LENGTH ];

}

TLSParameters;

Adding Session Resumption Logic to the Client

Now, go ahead and define a new top-level function called tls_resume that renegotiates a previously negotiated session. If you were so inclined, you could probably work this into the logic of tls_connect from Listing 6-7, but it's clearer to just define a new function. tls_resume is shown in Listing 8-5.

Listing 8-5: "tls.c" tls_resume

int tls_resume( int connection,

int session_id_length,

const unsigned char *session_id,

const unsigned char *master_secret,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

init_parameters( parameters );

parameters->connection_end = connection_end_client;

parameters->session_id_length = session_id_length;

memcpy( ¶meters->session_id, session_id, session_id_length );

new_md5_digest( ¶meters->md5_handshake_digest );

new_sha1_digest( ¶meters->sha1_handshake_digest );

// Send the TLS handshake "client hello" message

if ( send_client_hello( connection, parameters ) < 0 )

{

perror( "Unable to send client hello" );

return 1;

}

// Receive server hello, change cipher spec & finished.

parameters->server_hello_done = 0;

parameters->peer_finished = 0; while ( !parameters->peer_finished ) { if ( receive_tls_msg( connection, NULL, 0, parameters ) < 0 ) { perror( "Unable to receive server finished" ); return 6; } if ( server_hello_done ) { // Check to see if the server agreed to resume; if not, // abort, even though the server is probably willing to continue // with a new session. if ( memcmp( session_id, ¶meters->session_id, session_id_length ) ) { printf( "Server refused to renegotiate, exiting.\n" ); return 7; } else { memcpy( parameters->master_secret, master_secret, MASTER_SECRET_LENGTH ); calculate_keys( parameters ); } } } if ( !( send_change_cipher_spec( connection, parameters ) ) ) { perror( "Unable to send client change cipher spec" ); return 4; } if ( !( send_finished( connection, parameters ) ) ) { perror( "Unable to send client finished" ); return 5; } return 0; }

This is pretty close to tls_connect from Chapter 6; the differences are, of course, that it doesn't send a client_key_exchange message, and it has some special processing when the server_hello_done message is received:

if ( server_hello_done )

{

if ( memcmp( session_id, ¶meters->session_id, session_id_length ) )

{

printf( "Server refused to renegotiate, exiting.\n" ); return 7; } else { memcpy( parameters->master_secret, master_secret, MASTER_SECRET_LENGTH ); calculate_keys( parameters ); } }

First, it checks to see if the session ID returned by the server matches the one offered by the client. If not, the server is unable to or is unwilling to renegotiate this session. This code aborts if this is the case; normally you'd want to just continue on with the handshake and negotiate new keys. However, for experimental purposes, you should be more interested in ensuring that a resumption succeeded. This way, if you mistype the session ID, for instance, you get an immediate error.

Restoring the Previous Session's Master Secret

If the server is willing to resume, the client has to reproduce the master secret, so it had better have it handy. If it does, it can just perform the calculate keys routine. You could do this with the premaster secret, the master secret, or the keying material itself, but it's easiest to work with the master secret. Notice that the finished messages start over "from scratch" when a session resumes; neither side needs to keep track of the digest from the original handshake.

None of the subordinate functions except send_client_hello and parse_server_hello are aware that they are participating in a resumption instead of an initial handshake. send_client_hello, of course, needs to send the ID of the session it's trying to resume as shown in Listing 8-6.

Listing 8-6: "tls.c" send_client_hello with session resumption

static int send_client_hello( int connection, TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

memcpy( package.random.random_bytes, parameters->client_random + 4, 28 );

if ( parameters->session_id_length > 0 )

{

package.session_id_length = parameters->session_id_length;

package.session_id = parameters->session_id;

}

else

{

package.session_id_length = 0;

package.session_id = NULL;

If the client supports any extensions, it re-sends them here. This is important if the session ID is not recognized and the server starts a new handshake. It needs to be able to see all of the original extensions. Of course, if the client negotiates an extension the first time around, you should assume it's still in effect if the session is resumed.

Testing Session Resumption

You must update parse_server_hello, of course, to store the session ID assigned by the server as shown in Listing 8-7.

Listing 8-7: "tls.c" parse_server_hello with session ID support

memcpy( ( void * ) ( parameters->server_random + 4 ), ( void * )

hello.random.random_bytes, 28 );

parameters->session_id_length = hello.session_id_length;

memcpy( parameters->session_id, hello.session_id, hello.session_id_length );

Go ahead and expand the https example from Listing 6-2 to allow the user to pass in a session ID/master secret combination from a prior session for resumption. The session ID is unique to the target server. If you try to pass a session ID to a different server, the session ID will almost certainly not be recognized, and if it is, you don't know what the master secret was, so the session resumption fails when the server tries to verify your finished message. The modified https example is shown in Listing 8-8.

Listing 8-8: "https.c" main routine with session resumption

int main( int argc, char *argv[ ] )

{

...

int master_secret_length;

unsigned char *master_secret;

int session_id_length;

unsigned char *session_id;

...

proxy_host = proxy_user = proxy_password = host = path =

session_id = master_secret = NULL;

session_id_length = master_secret_length = 0;

for ( ind = 1; ind < ( argc - 1 ); ind++ )

{

if ( !strcmp( "-p", argv[ ind ] ) )

{

if ( !parse_proxy_param( argv[ ++ind ], &proxy_host, &proxy_port,

&proxy_user, &proxy_password ) ) { fprintf( stderr, "Error - malformed proxy parameter '%s'.\n", argv[ 2 ] ); return 2; } } else if ( !strcmp( "-s", argv[ ind ] ) ) { session_id_length = hex_decode( argv[ ++ind ], &session_id ); } else if ( !strcmp( "-m", argv[ ind ] ) ) { master_secret_length = hex_decode( argv[ ++ind ], &master_secret ); } } if ( ( ( master_secret_length > 0 ) && ( session_id_length == 0 ) ) || ( ( master_secret_length == 0 ) && ( session_id_length > 0 ) ) ) { fprintf( stderr, "session id and master secret must both be provided.\n" ); return 3; } ... if ( session_id != NULL ) { if ( tls_resume( client_connection, session_id_length, session_id, master_secret, &tls_context ) ) { fprintf( stderr, "Error: unable to negotiate SSL connection.\n" ); if ( close( client_connection ) == −1 ) { perror( "Error closing client connection" ); return 2; } return 3; } } else { if ( tls_connect( client_connection, &tls_context ) ) { ... if ( session_id != NULL ) { free( session_id ); }

Other than calling tls_resume instead of tls_connect, nothing else changes. As far as the rest of the library is concerned, it's as if the socket was never closed. Of course, if you actually want to try this out, you need to know what the session ID and master secret are; you can go ahead and print them out just after performing the TLS shutdown:

tls_shutdown( client_connection, &tls_context ); printf( "Session ID was: " ); show_hex( tls_context.session_id, tls_context.session_id_length ); printf( "Master secret was: " ); show_hex( tls_context.master_secret, MASTER_SECRET_LENGTH ); if ( close( client_connection ) == −1 )

Viewing a Resumed Session

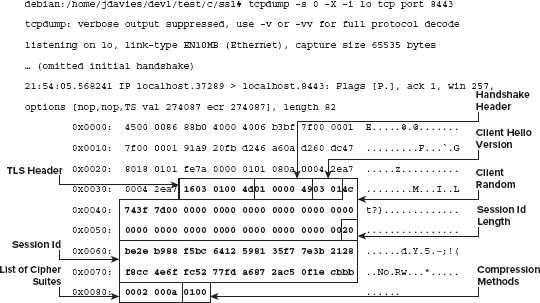

The following code illustrates a network trace of a resumed session:

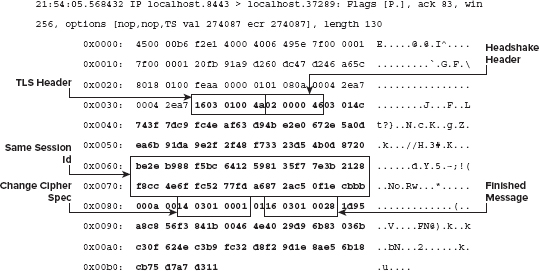

Here, the client hello message looks like the client hello message in Chapter 6, except that, this time, the session ID is non-empty.

The server responds with a server hello message containing the identical session ID. If the session ID is different here, the client should begin negotiating a new connection. If the session ID is the same, however, the client should expect the server hello to be followed immediately by a change cipher spec message, followed by a server finished.

The client follows up with its own change cipher spec and server finished message; this is followed immediately by encrypted application data, as shown here:

Adding Session Resumption on the Server Side

How about supporting session resumption on the server side? The server has to do quite a bit more work than the client. It must remember each session ID it assigns and the master key associated with each.

Assigning a Unique Session ID to Each Session

The first change you must make to support server-side session resumption is to assign a unique session ID to each session. Recall that in Chapter 7, each server hello message is sent with an empty session ID, which the client should interpret as "server unable to resume session." The changes to assign unique session IDs to each session are shown in Listing 8-9.

Listing 8-9: "tls.c" server-side session resumption support

static int next_session_id = 1;

static int send_server_hello( int connection, TLSParameters *parameters )

{

ServerHello package;

...

memcpy( package.random.random_bytes, parameters->server_random + 4, 28 );

if ( parameters->session_id_length == 0 )

{

// Assign a new session ID

memcpy( parameters->session_id, &next_session_id, sizeof( int ) );

parameters->session_id_length = sizeof( int );

next_session_id++;

}

package.session_id_length = parameters->session_id_length;

Here, I've gone ahead and made next_session_id a static variable. This could potentially create some threading problems if I was using this in a multithreaded application. The session ID in this case is a monotonically increasing 4-byte identifier. I also didn't bother correcting for host ordering, so if this is run on a little-endian machine, the first session ID shows up as 0x01000000, the second as 0x02000000, and so on. This increase doesn't really matter in this case, as long as each is unique. Finally, notice that the code checks whether a session ID has already been assigned before assigning one. This will be the case, when session resumption is added in Listing 8-15, if a session is being resumed.

Adding Session ID Storage

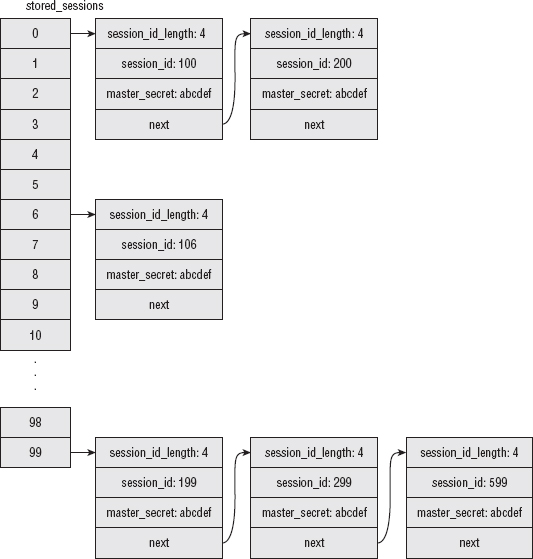

To actually store these, you need some internal data structure that can easily map session IDs to master secret values. As a nod to efficiency, go ahead and make this a hash table. First, declare a storage structure and a static instance to contain it as shown in Listing 8-10.

Listing 8-10: "tls.c" session storage hash table

#define HASH_TABLE_SIZE 100 typedef struct StoredSessionsList_t

{ int session_id_length; unsigned char session_id[ MAX_SESSION_ID_LENGTH ]; unsigned char master_secret[ MASTER_SECRET_LENGTH ]; struct StoredSessions_list_t *next; } StoredSessionsList; static StoredSessionsList *stored_sessions[ HASH_TABLE_SIZE ];

This structure simply contains the session ID and the master secret, which is the bare minimum amount of information you need to resume a prior session.

Because this is a static variable (again, not thread safe), it must be initialized on startup by the init_tls function shown in Listing 8-11.

Listing 8-11: "tls.c" init_tls

void init_tls()

{

int i = 0;

for ( i = 0; i < HASH_TABLE_SIZE; i++ )

{

stored_sessions[ i ] = NULL;

}

}

First of all, you need to store each successfully negotiated session in this structure. Listing 8-12 illustrates how to find the correct placement in the hash map for the master secret. By forcing the session IDs themselves to be numeric values, the hash function is simply the session ID modulo the size of the hash table.

Listing 8-12: "tls.c" remember_session

/**

* Store the session in the stored sessions cache

*/

static void remember_session( TLSParameters *parameters )

{

if ( parameters->session_id_length > 0 )

{

int session_id;

StoredSessionsList *head;

memcpy( &session_id, parameters->session_id, sizeof( int ) );

head = stored_sessions[ session_id % HASH_TABLE_SIZE ];

if ( head == NULL )

{

head = stored_sessions[ session_id % HASH_TABLE_SIZE ] =

malloc( sizeof( StoredSessionsList ) );

}

else

{ while ( head->next != NULL ) { head = ( StoredSessionsList * ) head->next; } head->next = malloc( sizeof( StoredSessionsList ) ); head = ( StoredSessionsList * ) head->next; } head->session_id_length = parameters->session_id_length; memcpy( head->session_id, &session_id, head->session_id_length ); memcpy( head->master_secret, parameters->master_secret, MASTER_SECRET_LENGTH ); head->next = NULL; } }

Figure 8-3 illustrates how this would be laid out in memory if you stored, for example, six sessions with IDs 100, 106, 199, 200, 299, and 599. Each entry in the stored_sessions array is a pointer to a linked list of every session whose ID is equal to its index, mod 100.

If you've ever studied data structures, this common technique for balancing storage space with lookup speed ought to look familiar. Listing 8-13 is the corresponding retrieval function.

Listing 8-13: "tls.c" find_stored_session

/**

* Check to see if the requested session ID is stored in the local cache.

* If the session ID is recognized, parameters will be updated to include

* it, and the master secret will be stored in the parameters.

* If it is not recognized, the session

* ID in the parameters will be left empty, indicating that a new handshake

* should commence.

*/

static void find_stored_session( int session_id_length,

const unsigned char *session_id,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

int session_id_num;

StoredSessionsList *head;

if ( session_id_length > sizeof( int ) )

{

// Definitely didn't come from this server.

return;

}

memcpy( &session_id_num, session_id, session_id_length );

for ( head = stored_sessions[ session_id_num % HASH_TABLE_SIZE ];

head != NULL; head = ( StoredSessionsList * ) head->next ) { if ( !memcmp( session_id, head->session_id, session_id_length ) ) { parameters->session_id_length = session_id_length; memcpy( parameters->session_id, head->session_id, session_id_length ); memcpy( parameters->master_secret, head->master_secret, MASTER_SECRET_LENGTH ); break; } } }

Figure 8-3: stored_sessions table

Notice that find_stored_session doesn't actually return anything. If it finds an entry corresponding to the request session, it updates the TLSParameters structure with the corresponding master secret and continues on. It's up to the caller to check to see if the TLSParameters structure was updated or not.

Modifying parse_client_hello to Recognize Session Resumption Requests

To make use of these new functions, parse_client_hello must first be modified to check to see if the client is attempting a renegotiation as shown in Listing 8-14.

Listing 8-14: "tls.c" parse_client_hello with session resumption support

static char *parse_client_hello( char *read_pos,

int pdu_length,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

free( hello.compression_methods );

if ( hello.session_id_length > 0 )

{

find_stored_session( hello.session_id_length, hello.session_id,

parameters );

}

if ( hello.session_id )

This just invokes find_stored_session_id if the client passes one in. If the requested session ID is found, the parameters structure now contains the master secret and the session ID that has been found. If not, nothing is done and the handshake should continue as if no session ID had been suggested. An unrecognized session ID is not necessarily an error—the client could just be trying to resume an old session.

Correspondingly, tls_accept must be updated to check this condition and perform the shortened handshake if the client is resuming as in Listing 8-15.

Listing 8-15: "tls.c" tls_accept with session resumption support

int tls_accept( int connection,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

parameters->got_client_hello = 0;

while ( !parameters->got_client_hello )

{

if ( receive_tls_msg( connection, NULL, 0, parameters ) < 0 )

{

perror( "Unable to receive client hello" ); send_alert_message( connection, handshake_failure, ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); return 1; } } if ( parameters->session_id_length > 0 ) { // Client asked for a resumption, and this server recognized the // session id. Shortened handshake here. "parse_client_hello" // will have already initiated calculate keys. if ( send_server_hello( connection, parameters ) ) { send_alert_message( connection, handshake_failure, ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); return 3; } // Can't calculate keys until this point because server random // is needed. calculate_keys( parameters ); // send server change cipher spec/finished message // Order is reversed when resuming if ( !( send_change_cipher_spec( connection, parameters ) ) ) { perror( "Unable to send client change cipher spec" ); send_alert_message( connection, handshake_failure, ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); return 7; } // This message will be encrypted using the newly negotiated keys if ( !( send_finished( connection, parameters ) ) ) { perror( "Unable to send client finished" ); send_alert_message( connection, handshake_failure, ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); return 8; } parameters->peer_finished = 0; while ( !parameters->peer_finished ) { if ( receive_tls_msg( connection, NULL, 0, parameters ) < 0 ) { perror( "Unable to receive client finished" ); send_alert_message( connection, handshake_failure, ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); return 6; }

If the session isn't being resumed—that is, it's new—the tls_accept must also remember it for future resumptions as shown in Listing 8-16.

Listing 8-16: "tls.c" tls_accept with session storage

if ( !( send_finished( connection, parameters ) ) )

{

perror( "Unable to send client finished" );

send_alert_message( connection, handshake_failure,

¶meters->active_send_parameters );

return 7;

}

// Handshake is complete; now ready to start sending encrypted data

// IFF the handshake was successful, put it into the sesion ID cache

// list for reuse.

remember_session( parameters );

}

The only other change that needs to made here is that init_parameters must initialize the session ID to be empty, as in Listing 8-17.

Listing 8-17: "tls.c" init_parameters with session resumption support

static void init_parameters( TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

parameters->session_id_length = 0;

}

Drawbacks of This Implementation

This implementation is by no means perfect, or complete. After a session is added to the hash table, it's never removed until the server shuts down. Not only is this an operational problem—its memory consumption grows without bounds until it crashes—it's also a security problem because a session can be resumed days or even weeks afterward. This won't be a significant problem for the use you put this server to, but it would be for a highly available server.

The TLS specification, RFC 2246, mandates that if a session was not shut down correctly—if the client didn't send a close notify alert before shutting down the socket—then the session should be marked non-resumable and attempts to resume it should fail. From section 7.2.1 of the RFC, which discusses the close_notify alert:

This message notifies the recipient that the sender will not send any more messages on this connection. The session becomes unresumable if any connection is terminated without proper close_notify messages with level equal to warning.

This was not widely implemented, and later versions of the specification rescinded this requirement. However, to be technically compliant with RFC 2246, this implementation ought to include this requirement when the negotiated protocol version is 3.1.

There's also a theoretical problem with this implementation. The server remembers the session ID and the master secret, and nothing else. What happens if the client sends a hello request with the same session ID, but a different set of cipher suites? What if, for example, the original session used RC4/MD5, but the new client hello only includes AES/SHA-1? In this case, it actually does work correctly because the master secret is just expanded as many times as it needs to be to generate the appropriate keying material. If the client is requesting the wrong cipher suite, though, you should just abandon the connection because it's most likely that somebody is trying to do something nasty.

A more robust server implementation should also keep track of which client hello extensions are successfully negotiated and ensure that the second hello request includes those same extensions. Depending on the negotiated extension, omitting it on a resumption request might be a fatal error.

Avoiding Fixed Parameters with Ephemeral Key Exchange

Chapter 6 states that after the server hello, the server should follow up with a certificate for key exchange. Technically, this isn't always true. Recall from Chapter 5 that although X.509 defines and allows the server to provide Diffie-Hellman parameters—Ys, p and g — in a certificate, the reality of Diffie-Hellman is that it works best when Ys is computed from a different secret value a for each instance. If the key exchange parameters aren't in the certificate, is the certificate strictly necessary?

As it turns out, no. There is a class of cipher suites referred to as ephemeral cipher suites that don't expect a key to be supplied in a certificate at all. Instead, the server sends a server key exchange message that contains the key exchange parameters—normally a set of Diffie-Hellman parameters. This way, each connection gets its own, unique, key exchange parameters which are never stored anywhere after the connection ends.

Supporting the TLS Server Key Exchange Message

To support ephemeral key exchange on the client side, the client must be prepared to accept either a certificate or a server key exchange message. As you can probably guess, implementing this first involves adding a new case arm to receive_tls_msg, shown in Listing 8-18.

Listing 8-18: "tls.c" receive_tls_msg with server key exchange

static int receive_tls_msg( int connection,

char *buffer,

int bufsz,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

switch ( handshake.msg_type )

{

...

case server_key_exchange:

read_pos = parse_server_key_exchange( read_pos, parameters );

if ( read_pos == NULL )

{

send_alert_message( connection, handshake_failure,

¶meters->active_send_parameters );

return −1;

}

break;

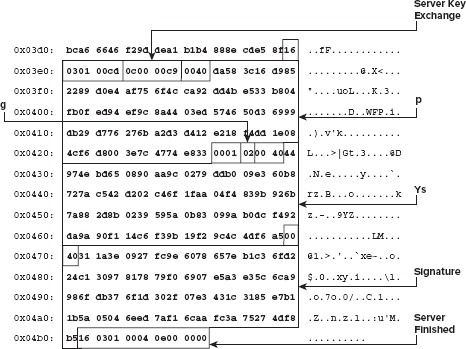

The optional server key exchange message is sent after the server hello. Both the certificate and the server key exchange handshake messages are optional, as indicated by the dashed lines in Figure 8-4.

Recall from Listing 6-37 that the send_client_key_exchange was coded to perform Diffie-Hellman key exchange if the cipher suite called for it, so the only thing left to do in parse_server_key_exchange is to store the Diffie-Hellman parameters for the subsequent key exchange as shown in Listing 8-19.

Listing 8-19: "tls.c" parse_server_key_exchange

static char *parse_server_key_exchange( unsigned char *read_pos,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

short length;

int i;

unsigned char *dh_params = read_pos;

for ( i = 0; i < 3; i++ )

{

memcpy( &length, read_pos, 2 );

length = ntohs( length );

read_pos += 2; switch ( i ) { case 0: load_huge( ¶meters->server_dh_key.p, read_pos, length ); break; case 1: load_huge( ¶meters->server_dh_key.g, read_pos, length ); break; case 2: load_huge( ¶meters->server_dh_key.Y, read_pos, length ); break; } read_pos += length; } return read_pos; }

Figure 8-4: TLS handshake with server key exchange

The server key exchange message is just a list of parameters; the receiver must know how to interpret them. Each element p, g, and Ys are given as variable-length structures so, in TLS style, are prepended by their lengths. Here you can see, they're each loaded into huge structures.

That's it; you already added support for the rest of the Diffie-Hellman key exchange in Listing 6-42. It was just a matter of getting the parameters to complete the exchange.

You can use this on a live server. The cipher suites that are named DH_anon_XXX work correctly with this code, as is, if the server supports the cipher suite. Wait — "if the server supports them"? Why wouldn't the server support them? Well, the name of the cipher suite offers a clue: DH_anon. This means that the handshake is anonymous and no protection against man-in-the-middle attacks is offered. How could you even check? There's no certificate, so there's no common name to compare to the domain name. Even if there were, there'd be no signature to verify with a trusted public key.

Authenticating the Server Key Exchange Message

Strictly speaking, it's not necessarily the case that certificate messages and server key exchange messages are mutually exclusive. Remember DSA certificates, which didn't seem terribly useful because you couldn't use the DSA public key for a key exchange? This is what they're useful for. A DSA certificate can provide a public key that can be used to verify a signature over a set of ephemeral Diffie-Hellman parameters. This same certificate can include a verifiable common name and a trusted signature. The signature itself can even be an RSA signature (which is fortunate, because I have yet to find a certificate authority that uses DSA to sign certificates).

In fact, the server can even send an RSA certificate before sending the server key exchange message in support of a Diffie-Hellman key exchange. You may wonder why anybody would want to go to all this trouble if they've already gotten an RSA certificate that can be used directly to do a key exchange, but remember that Diffie-Hellman achieves perfect forward secrecy. If RSA is used for key exchange, and the server's private key is ever compromised, every communication that is protected by that key is at risk.

Therefore, TLS defines another set of cipher suites called DHE_DSS_XXX for Diffie-Hellman with a DSA signature and DHE_RSA_XXX for Diffie-Hellman with an RSA signature. In both cases, the server key exchange is preceded by a certificate bearing either a DSA public key or an RSA public key. (There are also DH_XXX cipher suites that skip the server key exchange and expect the Diffie-Hellman parameters to appear in the certificate itself. As has been noted, this is rare).

As presented so far, though, this is still vulnerable to a man-in-the-middle attack. You can verify that the certificate belongs to the site you believe you're connecting to, but you can't verify that the key exchange parameters are the ones that were sent by the server itself. The man in the middle can replace the server's DH parameters with his own and you have no way of detecting this. After you verify the certificate and decide to trust this connection, the man in the middle takes over, drops the connection to the server, and you complete the handshake with the falsified server, none the wiser.

Therefore, the specification enables the server key exchange to be signed by the public key in the certificate. This optional signature immediately follows the key exchange parameters if present; it is present for any key exchange except for the anonymous types.

Extend the parse_server_key_exchange function from Listing 8-19 as shown in Listing 8-20 to recognize this signature if it is present and verify it. If it is present but doesn't verify according to the previously received certificate, return NULL, which causes the calling tls_receive_message to fail with the illegal parameter handshake alert.

Listing 8-20: "tls.c" parse_server_key_exchange with signature verification

static char *parse_server_key_exchange( unsigned char *read_pos,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

for ( i = 0; i < 4; i++ )

...

case 3:

// The third element is the signature over the first three, including their

// length bytes

if ( !verify_signature( dh_params,

( read_pos - 2 - dh_params ),

read_pos, length, parameters ) )

{

return NULL;

}

break;

}

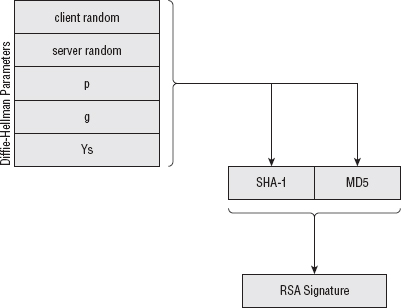

The signature type depends on the type of public key in the certificate. TLS defines two: RSA and DSA. Recall from Chapter 3 that an RSA signature is a secure hash of the data to be signed, encrypted with the private key. TLS actually takes a slightly more paranoid approach to RSA signatures, and encrypts both the MD5 and the SHA-1 hash, presumably to guard against a compromise of either hash function. Unfortunately, both are fairly weak today, and TLS 1.0 doesn't provide a way to negotiate a stronger hash function. Recall from Chapter 5 that the X.509 certificate signature included the OID of the corresponding hash function in its signature; TLS 1.0, unfortunately, didn't follow suit.

To verify an RSA signature over the server key exchange parameters, implement the verify_signature function in Listing 8-21.

Listing 8-21: "tls.c" verify_signature

static int verify_signature( unsigned char *message,

int message_len,

unsigned char *signature,

int signature_len,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

unsigned char *decrypted_signature;

int decrypted_signature_length;

digest_ctx md5_digest;

digest_ctx sha1_digest;

new_sha1_digest( &sha1_digest );

update_digest( &sha1_digest, parameters->client_random, RANDOM_LENGTH );

update_digest( &sha1_digest, parameters->server_random, RANDOM_LENGTH );

update_digest( &sha1_digest, message, message_len );

finalize_digest( &sha1_digest );

new_md5_digest( &md5_digest );

update_digest( &md5_digest, parameters->client_random, RANDOM_LENGTH );

update_digest( &md5_digest, parameters->server_random, RANDOM_LENGTH );

update_digest( &md5_digest, message, message_len );

finalize_digest( &md5_digest );

decrypted_signature_length = rsa_decrypt( signature, signature_len,

&decrypted_signature,

¶meters->server_public_key.rsa_public_key );

if ( memcmp( md5_digest.hash, decrypted_signature, MD5_BYTE_SIZE ) ||

memcmp( sha1_digest.hash, decrypted_signature + MD5_BYTE_SIZE,

SHA1_BYTE_SIZE ) )

{

return 0;

}

free( decrypted_signature );

return 1;

}

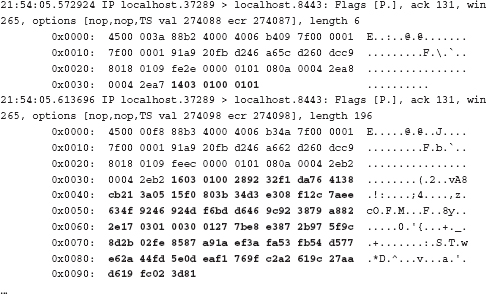

Each digest is over the two random values and then the parameters; incorporating the random values this way prevents replay attacks. The whole signature process is illustrated in Figure 8-5.

Figure 8-5: Server key exchange signature

Examining an Ephemeral Key Exchange Handshake

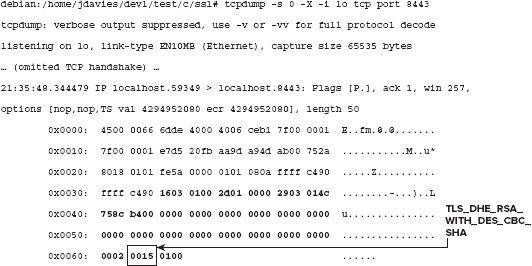

Here is an illustration of an abbreviated DHE/RSA/DES/SHA-1 handshake.

This is an ordinary client hello message, just like the one in Chapter 6. The only noteworthy point here is that the only offered cipher suite is an ephemeral Diffie-Hellman cipher.

21:35:48.345236 IP localhost.8443 > localhost.59349: Flags [P.], ack 51, win

256, options [nop,nop,TS val 4294952080 ecr 4294952080], length 1158

0x0000: 4500 04ba b1bb 4000 4006 8680 7f00 0001 E.....@.@.......

0x0010: 7f00 0001 20fb e7d5 ab00 752a aa9d a97f ..........u*....

0x0020: 8018 0100 02af 0000 0101 080a ffff c490 ................ 0x0030: ffff c490 1603 0100 4a02 0000 4603 014c ........J...F..L 0x0040: 758c b47e 27e1 3d63 09fa 4c62 83c8 a510 u..~'.=c..Lb.... 0x0050: 72a1 9a98 4c4e 186d 000b c059 31c1 4220 r...LN.m...Y1.B. 0x0060: 1823 08ca b7af a651 a39a f8e4 56c2 5934 .#.....Q....V.Y4 0x0070: 2ffd c57b aafe 12f9 bff3 9b0f 85ef 08a9 /..{............ 0x0080: 0015 0016 0301 0357 0b00 0353 0003 5000 .......W...S..P. ... (omitted certificate) ...

The server hello and certificate messages occur as before; however, instead of being followed immediately by server done, they're followed by a server key exchange message that identifies the Diffie-Hellman values p, g, and Ys. The length declarations of each are highlighted in the preceding code. This is followed by the RSA signature of the MD5 hash of client random, server random, and the remainder of the server key exchange, followed by the SHA-1 hash of the client random, the server random, and the remainder of the message. The client should use the public key of the certificate—which should have been verified using the public key of a trusted certificate—to verify these key exchange parameters.

The server hello done is always followed by a client key exchange, whether the key exchange was an ephemeral one or not. In this case, the client key exchange is significantly shorter than in the case of an RSA key exchange, especially because the "secret" value A was hardcoded to be 6 by this implementation. Because g is 2 (see the preceding code), Yc = 26 %p = 64. To complete the key exchange, the server must compute 64B %p. I can't show you this computation because I don't know what B was. No matter how hard I try, I shouldn't be able to figure it out. The client must compute Ys6 %p to settle on the premaster secret.

The remainder of the handshake continues as in the RSA key exchange case; now that the premaster secret has been successfully exchanged, the client sends a change cipher spec, followed by a finished message, which the server reciprocates as shown below.

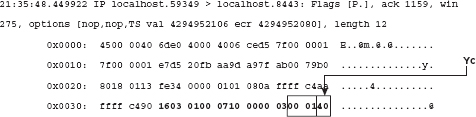

21:35:48.488513 IP localhost.59349 > localhost.8443: Flags [P.], ack 1159, win

275, options [nop,nop,TS val 4294952116 ecr 4294952116], length 51

0x0000: 4500 0067 6de1 4000 4006 cead 7f00 0001 E..gm.@.@.......

0x0010: 7f00 0001 e7d5 20fb aa9d a98b ab00 79b0 ..............y.

0x0020: 8018 0113 fe5b 0000 0101 080a ffff c4b4 .....[..........

0x0030: ffff c4b4 1403 0100 0101 1603 0100 28ac ..............(.

0x0040: cc09 37ea 64f2 4677 68e8 0025 bf96 f1df ..7.d.Fwh..%....

0x0050: 92f3 f83a b5a9 cb9e 6672 e245 4687 2259 ...:....fr.EF."Y

0x0060: 9135 c6f2 707a b6 .5..pz.

21:35:48.488901 IP localhost.8443 > localhost.59349: Flags [P.], ack 114, win

256, options [nop,nop,TS val 4294952116 ecr 4294952116], length 51

0x0000: 4500 0067 b1be 4000 4006 8ad0 7f00 0001 E..g..@.@.......

0x0010: 7f00 0001 20fb e7d5 ab00 79b0 aa9d a9be ..........y.....

0x0020: 8018 0100 fe5b 0000 0101 080a ffff c4b4 .....[..........

0x0030: ffff c4b4 1403 0100 0101 1603 0100 2827 ..............('

0x0040: a9bf 753d f061 2e90 62b3 5cfa 19f8 52f4 ..u=.a..b.\...R.

0x0050: 4ad5 6a59 5d4e 5bba 7f89 3ce3 9e25 c15f J.jY]N[...<..%._

0x0060: 5e1d 0ef8 a8ce 22 ^....."

This works for all of the DHE_RSA_xxx cipher suites—that is, those whose certificate includes an RSA public key. What about the DHE_DSS_xxx cipher suites?

If you recall from Listing 6-5, the TLSParameters structure is declared to have space only for an RSA public key. If the server returns a DSA public key, it is ignored. Back then, that was a sensible decision because you were just focusing on RSA-based key exchanges, but now you can actually do something with a DSA certificate.

To support DSA verification, change the TLSParameters server_public_key type from an rsa_key to the public_key_info structure that is defined in Listing 5-26. This has a section for either an rsa_key or a dsa key, plus the required dsa params. This is shown in Listing 8-22.

... ProtectionParameters active_recv_parameters; public_key_info server_public_key; dh_key server_dh_key; ... } TLSParameters;

Pass this into parse_x509_chain when parsing the certificate message as shown in Listing 8-23.

Listing 8-23: "tls.c" receive_tls_message with DSA key support

static int receive_tls_msg( int connection,

char *buffer,

int bufsz,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

case certificate:

read_pos = parse_x509_chain( read_pos, handshake.length,

¶meters->server_public_key );

Modify send_client_key_exchange to recognize this new level of indirection as in Listing 8-24.

Listing 8-24: "tls.c" send_client_key_exchange

static int send_client_key_exchange( int connection, TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

key_exchange_message_len = rsa_key_exchange(

¶meters->server_public_key.rsa_public_key,

premaster_secret, &key_exchange_message );

Because parse_x509_chain has to update the server_public_key structure rather than just an RSA key structure, make the appropriate modifications as shown in Listing 8-25.

Listing 8-25: "x509.c" parse_x509_chain with DSA support

char *parse_x509_chain( unsigned char *buffer,

int pdu_length,

public_key_info *server_public_key )

{

...

if ( !pos++ )

{

// Copy public key information into target on first cert only

server_public_key->algorithm =

certificate.tbsCertificate.subjectPublicKeyInfo.algorithm;

switch ( server_public_key->algorithm ) { case rsa: server_public_key->rsa_public_key.modulus = ( huge * ) malloc( sizeof( huge ) ); server_public_key->rsa_public_key.exponent = ( huge * ) malloc( sizeof( huge ) ); set_huge( server_public_key->rsa_public_key.modulus, 0 ); set_huge( server_public_key->rsa_public_key.exponent, 0 ); copy_huge( server_public_key->rsa_public_key.modulus, certificate.tbsCertificate.subjectPublicKeyInfo.rsa_public_key.modulus ); copy_huge( server_public_key->rsa_public_key.exponent, certificate.tbsCertificate.subjectPublicKeyInfo.rsa_public_key.exponent ); break; case dsa: set_huge( &server_public_key->dsa_parameters.g, 0 ); set_huge( &server_public_key->dsa_parameters.p, 0 ); set_huge( &server_public_key->dsa_parameters.q, 0 ); set_huge( &server_public_key->dsa_public_key, 0 ); copy_huge( &server_public_key->dsa_parameters.g, &certificate.tbsCertificate.subjectPublicKeyInfo.dsa_parameters.g ); copy_huge( &server_public_key->dsa_parameters.p, &certificate.tbsCertificate.subjectPublicKeyInfo.dsa_parameters.p ); copy_huge( &server_public_key->dsa_parameters.q, &certificate.tbsCertificate.subjectPublicKeyInfo.dsa_parameters.q ); copy_huge( &server_public_key->dsa_public_key, &certificate.tbsCertificate.subjectPublicKeyInfo.dsa_public_key ); break; default: // Diffie-Hellman certificates not supported in this implementation break; }

This just copies the relevant parts of the certificate's subjectPublicKeyInfo values into the one in TLSParameters.

Modify verify_signature itself to verify a DSA signature when appropriate. Recall from Chapter 4 that a DSA signature by its nature is computed over a single hash value; you can't safely play games with concatenated hash values using DSA like TLS does with RSA. The dsa_verify function of Listing 4-33 just returns a true or false; you don't "decrypt" anything. Also, a DSA signature is not just a single number; it is two numbers, r and s. To keep them straight, TLS mandates that they be provided in ASN.1 DER-encoded form.

Modify verify_signature as shown in Listing 8-26 to verify DSA signatures if the certificate contains a DSA public key.

Listing 8-26: "tls.c" verify_signature

static int verify_signature( unsigned char *message,

int message_len,

unsigned char *signature, int signature_len, TLSParameters *parameters ) { // This is needed for RSA or DSA digest_ctx sha1_digest; new_sha1_digest( &sha1_digest ); update_digest( &sha1_digest, parameters->client_random, RANDOM_LENGTH ); update_digest( &sha1_digest, parameters->server_random, RANDOM_LENGTH ); update_digest( &sha1_digest, message, message_len ); finalize_digest( &sha1_digest ); if ( parameters->server_public_key.algorithm == rsa ) { unsigned char *decrypted_signature; int decrypted_signature_length; digest_ctx md5_digest; decrypted_signature_length = rsa_decrypt( signature, signature_len, &decrypted_signature, ¶meters->server_public_key.rsa_public_key ); // If the signature algorithm is RSA, this will be the md5 hash, followed by // the sha-1 hash of: client random, server random, params). // If DSA, this will just be the sha-1 hash new_md5_digest( &md5_digest ); update_digest( &md5_digest, parameters->client_random, RANDOM_LENGTH ); update_digest( &md5_digest, parameters->server_random, RANDOM_LENGTH ); update_digest( &md5_digest, message, message_len ); finalize_digest( &md5_digest ); if ( memcmp( md5_digest.hash, decrypted_signature, MD5_BYTE_SIZE ) || memcmp( sha1_digest.hash, decrypted_signature + MD5_BYTE_SIZE, SHA1_BYTE_SIZE ) ) { return 0; } free( decrypted_signature ); } else if ( parameters->server_public_key.algorithm == dsa ) { struct asn1struct decoded_signature; dsa_signature received_signature; asn1parse( signature, signature_len, &decoded_signature ); set_huge( &received_signature.r, 0 ); set_huge( &received_signature.s, 0 ); load_huge( &received_signature.r, decoded_signature.children->data, decoded_signature.children->length );

load_huge( &received_signature.s, decoded_signature.children->next->data, decoded_signature.children->next->length ); asn1free( &decoded_signature ); if ( !dsa_verify( ¶meters->server_public_key.dsa_parameters, ¶meters->server_public_key.dsa_public_key, sha1_digest.hash, SHA1_BYTE_SIZE, &received_signature ) ) { free_huge( &received_signature.r ); free_huge( &received_signature.s ); return 0; } free_huge( &received_signature.r ); free_huge( &received_signature.s ); } return 1; }

Notice that the SHA-1 digest is computed regardless of the signature type; it is needed whether the signature is an RSA or DSA signature.

DHE is not very common; most servers still prefer RSA for key exchange, and those that do support DHE still present an RSA, rather than a DSA, certificate. This doesn't mean that RSA has an advantage over Diffie-Hellman for key exchange; RSA also uses the same private key over and over, for potentially millions and millions of handshakes. There's no particular reason why certificate-based Diffie-Hellman can't be used, or why the server key exchange can't include an RSA key which was different for each connection instead of DH parameters. However, the fact that RSA can be used for both signature generation and encryption meant that it was more common in certificates, so this has ended up being the way it was most often used.

Verifying Identity with Client Authentication

In almost all cases—unless the cipher suite is one of the DH_anon_XXX cipher suites—the server is required to present a certificate, signed by a certificate authority, whose subject name's CN field matches the DNS name to which the client is trying to connect. This is always useful to guard against man-in-the-middle attacks; without this certificate, there's no way, at all, to be sure that a malicious attacker didn't hijack your connection during the handshake.

But what about the reverse situation? The server has no way of verifying that the client is really who it says it is. This may or may not be important, but most applications that use TLS to protect the privacy and authenticity of communications also require that the client authenticate itself through some means such as a shared password.

If you think about it, this is sort of archaic. All of the problems of synchronizing shared keys apply to shared passwords. Because you have public-key cryptography and PKI, why not use it?

Imagine, for instance, an online bank that creates its own internal CA and then uses that CA to sign customer's certificate requests at a physical branch location (after authenticating them physically by verifying a driver's license, fingerprints, and so on). The customer can then install that CA's root certificate and his own signed certificate on his computer and use that to prove his identity in addition to the primitive username/password authentication method currently used. (You need both methods to guard against the damage of a private key compromise.)

TLS allows for this. The server can demand a certificate and refuse to complete the handshake unless the client provides one, signed by a suitable certificate authority. RSA Data Security's RSA Key Manager (RKM) product uses this technique to authenticate requests from applications, but it's not as widespread as it could be. This is a shame, because it's a very good, secure way to authenticate users. If a bank started requiring this sort of "mutual authentication," I would definitely put all of my money in it.

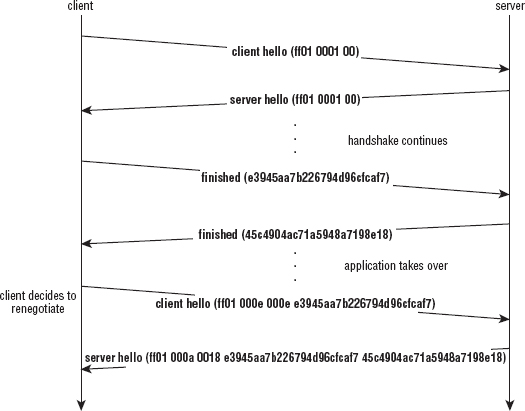

TLS describes two additional handshake messages to support client authentication.

- The CertificateRequest handshake message is sent by the server to the client, notifying the client that it expects the client to authenticate itself with a certificate. The Certificate message sent by the client is exactly the same format as the certificate message sent by the server.

- the CertificateVerify message, the second new handshake message, is sent by the client to prove that it is, in fact, in possession of the private key corresponding to the public key in the certificate itself.

Supporting the CertificateRequest Message

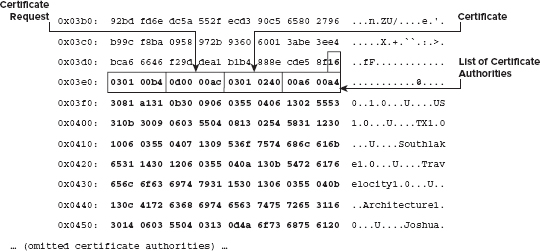

The CertificateRequest handshake message is sent by the server after sending its own certificate and, if applicable, server key exchange.

NOTE If the server did not send a certificate—for example, if it is performing an anonymous key exchange—it may not request a certificate from the client.

The designers of TLS could have designed the certificate request to have been defined as a simple marker request like the hello done and ChangeCipherSpec messages were. However, to streamline things a bit, the TLS designers allowed the server to indicate what sorts of certificates it would accept, and by which CAs. This makes some sense. The most likely use case for a client-side authentication is a private CA, not one of the public, shared, pre-trusted (and expensive!) ones. As long as the CA's private key is kept private, it's no less secure than a public CA. In fact, it might be more secure.

The format of the CertificateRequest message is first a list of the types of certificates it accepts; TLS 1.0 defines four: rsa_sign, dss_sign, rsa_fixed_dh, and dss_fixed_dh. Following this is a list of the ASN.1 DER-encoded distinguished names of the certificate authorities that the server trusts. The specification is silent on whether this list must contain any entries or is allowed to be empty, and what to do if the list of trusted CAs is empty. Some implementations respond with an empty list to indicate that any CA is trusted. Although this sort of defeats the purpose, you should be aware that it is a possible condition.

Adding Certificate Request Parsing Capability for the Client

The client has no way of knowing when a server might demand a client certificate, so it has to be ready to handle the request, whether by supplying a certificate or by aborting the connection. Add a new flag to TLSParameters as shown in Listing 8-27.

Listing 8-27: "tls.h" TLSParameters with certificate request flag

typedef struct

{

...

int peer_finished;

int got_certificate_request;

digest_ctx md5_handshake_digest;

...

}

TLSParameters;

Of course, as with all potential handshake messages, you need to add a new conditional in receive_tls_msg as shown in Listing 8-28.

Listing 8-28: "tls.c" receive_tls_msg with certificate request support

static int receive_tls_msg( int connection,

char *buffer,

int bufsz,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

case certificate_request: // Abort if server requests a certificate?

read_pos = parse_certificate_request( read_pos, parameters );

break;

...

The certificate request message indicates what sort of certificates the server is capable of receiving and what CAs it trusts to sign one. This implementation isn't robust enough to associate potential certificates with their signers; it just hardcodes a single certificate and always returns that, if asked for any certificate. This has to be good enough for the server. However, to illustrate the layout of the certificate request message, go ahead and add code to parse it as shown in Listing 8-29.

Listing 8-29: "tls.c" parse_certificate_request

#define MAX_CERTIFICATE_TYPES 4

typedef enum

{

rsa_signed = 1,

dss_signed = 2,

rsa_fixed_dh = 3,

dss_fixed_dh = 4

}

certificate_type;

typedef struct

{

unsigned char certificate_types_count;

certificate_type supported_certificate_types[ MAX_CERTIFICATE_TYPES ];

}

CertificateRequest;

static unsigned char *parse_certificate_request( unsigned char *read_pos,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

int i;

int trusted_roots_length;

unsigned char *init_pos;

CertificateRequest request;

read_pos = read_buffer( &request.certificate_types_count, read_pos, 1 );

for ( i = 0; i < request.certificate_types_count; i++ )

{

read_pos = read_buffer(

( void * ) &request.supported_certificate_types[ i ], read_pos, 1 );

}

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &trusted_roots_length, read_pos, 2 );

trusted_roots_length = htons( trusted_roots_length );

init_pos = read_pos;

while ( ( read_pos - init_pos ) < trusted_roots_length )

{

int dn_length;

struct asn1struct dn_data;

name dn; read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &dn_length, read_pos, 2 ); dn_length = htons( dn_length ); asn1parse( read_pos, dn_length, &dn_data ); parse_name( &dn, &dn_data ); printf( "Server trusts issuer: C=%s/ST=%s/L=%s/O=%s/OU=%s/CN=%s\n", dn.idAtCountryName, dn.idAtStateOrProvinceName, dn.idAtLocalityName, dn.idAtOrganizationName, dn.idAtOrganizationalUnitName, dn.idAtCommonName ); asn1free( &dn_data ); read_pos += dn_length; } parameters->got_certificate_request = 1; return read_pos; }

Handling the Certificate Request

The certificate request is split into two parts. The first is a variable-length list of recognized certificate types; the values defined by TLS 1.0 are described by the enumeration certificate_types. The second part is a variable-length list of ASN.1 DER-encoded X.509 distinguished names (whew!) of trusted CAs. Notice in Listing 8-29 that the CertificateRequest structure defined in this book's implementation has a section to store the received certificate types but not the CA names. You can—and a robust implementation certainly should—store them for downstream processing, but the memory management gets fairly complex and adds little to the discussion here because this code ignores the information. Still, for your edification, the list of trusted CAs is parsed and printed out. In most common use cases, there is only a single trusted CA here.

The only really important bit of this routine is the setting of the got_certificate_request flag. This indicates to the tls_connect routine that it must send a certificate. If, and only if, the server sends a certificate request, the client should send a certificate. The client certificate message is in exactly the same format as the server certificate; the code can be reused as is, as shown in Listing 8-30.

Listing 8-30: "tls.c" tls_connect with support for certificate requests

// Step 2. Receive the server hello response (will also have gotten

// the server certificate along the way)

parameters->server_hello_done = 0;

parameters->got_certificate_request = 0;

while ( !parameters->server_hello_done )

{

if ( receive_tls_msg( connection, NULL, 0, parameters ) < 0 )

{ perror( "Unable to receive server hello" ); return 2; } } // Certificate precedes key exchange if ( parameters->got_certificate_request ) { send_certificate( connection, parameters ); }

The send_certificate routine is exactly the same as the one from Listing 7-11; there's no difference between the two at all.

NOTE Because the certificate name is hardcoded into this routine, if you run the server from Chapter 7 from the same directory as you run the client, you actually return the same certificate that the server uses for key exchange! Obviously, this isn't the way things normally work, but it's good enough for illustration purposes.

Supporting the Certificate Verify Message

The code presented in Listing 8-30 won't quite work, though. Consider; the client has presented a certificate whose common name is, for example, "Joshua Davies." The certificate is signed by a trusted CA. It's also passed in the clear, so any eavesdropper who's listening in can capture it and reuse it, masquerading as this "Joshua Davies" fellow. Recall that the server's certificate was tied to a domain name; the client could verify that the CN component of the certificate's subject name matches the domain name to which it is connecting. The server can't do that with the client's certificate; the client is likely to be mobile and probably won't have a domain name.

Therefore, there's one last thing the client needs to do in order to satisfy a certificate request. It must use the private key that corresponds to the server's public key to sign a secure hash of the handshake messages that have been exchanged so far.

This should sound familiar; it's the same thing that was done for the finished message in Listing 6-53. In fact, the code to build the CertificateVerify handshake message is pretty similar to the code to compute the verify data in the finished message. The only real difference is that instead of iterating the secure hash through the PRF, the secure hash is signed using the private key.

Refactoring rsa_encrypt to Support Signing

Recall from Chapter 4 that RSA signatures are data encrypted using an RSA private key. This is almost exactly the same as RSA encryption, except that the block type is slightly different; rather than padding with random bytes, the padding section contains all 1's.

Why is this? Well, imagine that the same RSA key was used to decrypt private data as well as to sign messages. To keep the example small and simple, use small values—the mini-key pair e = 79, d = 1019, and n = 3337 from Chapter 3 works nicely. Now, let's say you encrypted your secret number, 42, using the public key e and n, which works out to 2,973. So far, so good; an eavesdropper without access to d can't recover your secret number 42. All he saw was 2,973, which is useless to him.

However, he can trick the private key holder into revealing it. He can ask the private key holder to please sign his credit card number, which happens to be 2,973. Now, the private key holder computes 2973d % n, which is your secret number 42. Oops.

To guard against this, PKCS #1 mandates that signatures and encryptions be padded differently. It's the responsibility of the signer to add this padding before signing anything.

It's easy to refactor the rsa_encrypt routing from Listing 3-17 to support signing and encrypting correctly. Extract everything except the padding into a separate routing called rsa_process that takes a block_type as an argument, and call it from rsa_encrypt and rsa_sign as shown in Listing 8-31.

Listing 8-31: "rsa.c" rsa_encrypt and rsa_sign

int rsa_process( unsigned char *input,

unsigned int len,

unsigned char **output,

rsa_key *public_key,

unsigned char block_type )

{

...

memcpy( padded_block + ( modulus_length - block_size ), input, block_size );

// set block type

padded_block[ 1 ] = block_type;

for ( i = 2; i < ( modulus_length - block_size - 1 ); i++ )

{

if ( block_type == 0x02 )

{

// TODO make these random

padded_block[ i ] = i;

}

else

{

padded_block[ i ] = 0xFF;

}

}

load_huge( &m, padded_block, modulus_length ); ... } int rsa_encrypt( unsigned char *input, unsigned int len, unsigned char **output, rsa_key *public_key ) { return rsa_process( input, len, output, public_key, 0x02 ); } int rsa_sign( unsigned char *input, unsigned int len, unsigned char **output, rsa_key *private_key ) { return rsa_process( input, len, output, private_key, 0x01 ); }

Now you can use this signature routine to generate the certificate verify message as shown in Listing 8-32.

Listing 8-32: "tls.c" send_certificate_verify

static int send_certificate_verify( int connection,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

unsigned char *buffer;

int buffer_length;

rsa_key private_key;

digest_ctx tmp_md5_handshake_digest;

digest_ctx tmp_sha1_handshake_digest;

unsigned short handshake_signature_len;

unsigned char *handshake_signature;

unsigned short certificate_verify_message_len;

unsigned char *certificate_verify_message;

unsigned char handshake_hash[ ( MD5_RESULT_SIZE * sizeof( int ) ) +

( SHA1_RESULT_SIZE * sizeof( int ) ) ];

compute_handshake_hash( parameters, handshake_hash );

memcpy( handshake_hash, tmp_md5_handshake_digest.hash, MD5_BYTE_SIZE );

memcpy( handshake_hash + MD5_BYTE_SIZE, tmp_sha1_handshake_digest.hash,

SHA1_BYTE_SIZE );

if ( !( buffer = load_file_into_memory( "key.der", &buffer_length ) ) )

{

perror( "Unable to load file" );

return 0;

} parse_private_key( &private_key, buffer, buffer_length ); free( buffer ); handshake_signature_len = ( unsigned short ) rsa_sign( handshake_hash, MD5_BYTE_SIZE + SHA1_BYTE_SIZE, &handshake_signature, &private_key ); certificate_verify_message_len = handshake_signature_len + sizeof( unsigned short ); certificate_verify_message = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( certificate_verify_message_len ); // copying this "backwards" so that I can use the signature len // as a numeric input but then htons it to send on. memcpy( ( void * ) ( certificate_verify_message + 2 ), ( void * ) handshake_signature, handshake_signature_len ); handshake_signature_len = htons( handshake_signature_len ); memcpy( ( void * ) certificate_verify_message, ( void * ) &handshake_signature_len, sizeof( unsigned short ) ); send_handshake_message( connection, certificate_verify, certificate_verify_message, certificate_verify_message_len, parameters ); free( certificate_verify_message ); free( handshake_signature ); return 1; } ... int tls_connect( int connection, TLSParameters *parameters ) { ... if ( !( send_client_key_exchange( connection, parameters ) ) ) { perror( "Unable to send client key exchange" ); return 3; } // Certificate verify comes after key exchange if ( parameters->got_certificate_request ) { if ( !send_certificate_verify( connection, parameters ) ) { perror( "Unable to send certificate verify message" ); return 3; } }

Almost all of this logic was discussed in the compute_verify_data routine in Listing 6-53 and the parse_client_key_exchange in Listing 7-18. The only thing new here is the formatting of the certificate verify message; this is just the length of the signature, followed by the signature bytes. Network byte ordering makes this a bit more complex than you might expect it to be, but otherwise there's not much to it. The full handshake, with optional client authentication, is shown in Figure 8-6.

Figure 8-6: TLS handshake with client authentication

As you can see, a full TLS handshake can take as many as 13 independent messages. However, by taking advantage of message concatenation, this can be reduced to four network round trips. This is still quite a few, considering that the TCP handshake itself already used up three. You can see why session resumption is important.

Testing Client Authentication

You can use OpenSSL to test client authentication because you'll probably find it very difficult to locate a server on the public Internet that requests and accepts client certificates. The process for even getting OpenSSL's test server s_server to accept client certificates is a complicated one:

- Create a root cert; you did this in Chapter 5 via

openssl req -x509 -newkey rsa:512 -out root_cert.pem -keyout root_key.pem

- Copy this into a special directory; call it "trusted_certs" (for example).

- OpenSSL requires that all root certificates be named according to a special convention—the name should be a hash of the subject name followed by a number. You can see the hash of the subject name by running the command

openssl x509 -hash -in root_cert.pem -noout 6018de75

6018de75 is the hash in this case. Rename (or symbolically link, if your system supports it) the root certificate to 6018de75.0.

- Create a certificate that the client passes back in.

- First, create a CSR:

openssl req -newkey rsa:512 -out client_csr.pem -keyout client_key.pem

Notice that the same command, req, is used to create a CSR as was used to create the self-signed root certifi cate above. The difference between the creation of the CSR and of the root CA is that the CSR-creation command omits the -x509 parameter.

- Sign the CSR using the root certifi cate you generated in step 1. This is an involved process; OpenSSL supports it as a demonstration of how it can be done. OpenSSL recommends that you not actually use the software for this purpose except for testing, although apparently some entities do use this as a full-blown CA.

- To configure your own mini-CA, you need to first create a file called ca.cnf as shown in Listing 8-33.

NOTE These files are required to complete a CSR signature; if you want to know more about what they're for and what other options are available, consult the OpenSSL documentation.

- You also need an empty index.txt file

touch index.txt

or, on a windows system

fsutil file createnew index.txt 0

and a file name serial with the next serial number in it. Because this is a new "certificate authority," the first serial number it issues is serial number 1:

echo 01 > serial

- With this very minimal infrastructure, you can now sign your CSR using the root CA file:

[jdavies@localhost trusted_certs]$ openssl ca -config ca.cnf -cert root_cert.pem \ -keyfile root_key.pem -in client_csr.pem -out client_cert.pem -outdir .-md sha1 \ -days 365 Using configuration from ca.cnf Enter pass phrase for root_key.pem: Check that the request matches the signature Signature ok The Subject's Distinguished Name is as follows countryName :PRINTABLE:'US' stateOrProvinceName :PRINTABLE:'TX' localityName :PRINTABLE:'Southlake' organizationName :PRINTABLE:'Architecture' organizationalUnitName:PRINTABLE:'Travelocity' commonName :PRINTABLE:'Joshua Davies Client' emailAddress :IA5STRING:'joshua.davies@travelocity.com' Certificate is to be certified until Aug 11 22:31:21 2011 GMT (365 days) Sign the certificate? [y/n]:y

1 out of 1 certificate requests certified, commit? [y/n]y Write out database with 1 new entries Data Base Updated

This produces the client_cert.pem file that you pass back to the server from the client. You may also have noticed that it modifi es the index.txt and serial files that you created earlier.

- Start up the openssl s_server with client certifi cate support active:

openssl s_server -tls1 -accept 8443 -cert cert.pem -key key.pem -Verify 1 \ -CApath trusted_certs/ -CAfile trusted_certs/root_cert.pem -www

- First, create a CSR:

This tells the server to demand a certificate that has been signed by root_cert.pem. Notice that the server does not need access to the root certificate's private key to do this; the public key is sufficient to verify a signature, just not to generate one. Also notice that the certificate presented by the server for its own authentication need not be—shouldn't be, in fact—the same as the root certificate that signs client certificates.

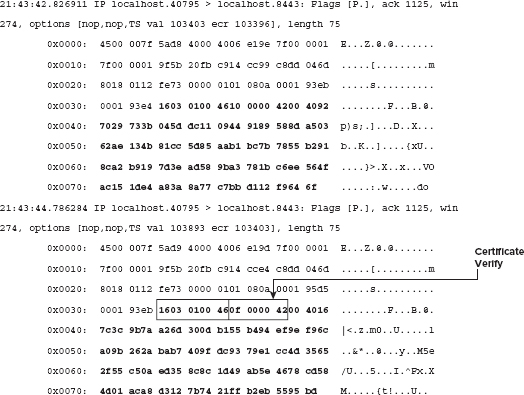

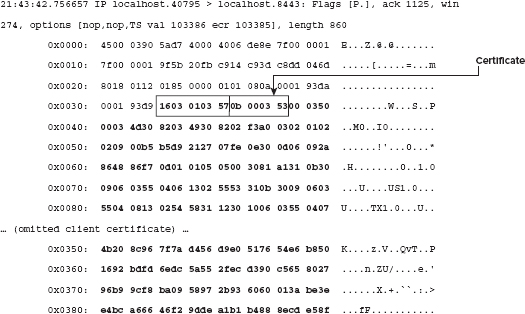

Viewing a Mutually-Authenticated TLS Handshake

The following is an examination of a network capture of a mutually authenticated handshake.

debian:/home/jdavies/devl/test/c/ssl# tcpdump -s 0 -X -i lo tcp port 8443

tcpdump: verbose output suppressed, use -v or -vv for full protocol decode

listening on lo, link-type EN10MB (Ethernet), capture size 65535 bytes

... (omitted TCP handshake) ...

21:43:42.754999 IP localhost.40795 > localhost.8443: Flags [P.], ack 1, win 257,

options [nop,nop,TS val 103385 ecr 103385], length 50

0x0000: 4500 0066 5ad5 4000 4006 e1ba 7f00 0001 E..fZ.@.@.......

0x0010: 7f00 0001 9f5b 20fb c914 c90b c8dd 0009 .....[..........

0x0020: 8018 0101 fe5a 0000 0101 080a 0001 93d9 .....Z..........

0x0030: 0001 93d9 1603 0100 2d01 0000 2903 014c ........-...)..L

0x0040: 758e 8e00 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 u...............

0x0050: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

0x0060: 0002 002f 0100 .../..

21:43:42.755151 IP localhost.8443 > localhost.40795: Flags [P.], ack 51, win

256, options [nop,nop,TS val 103385 ecr 103385], length 1124

0x0000: 4500 0498 93d1 4000 4006 a48c 7f00 0001 E.....@.@.......