CHAPTER 3

Secure Key Exchange over an Insecure Medium with Public Key Cryptography

Chapter 2 examined symmetric or private/shared key algorithms. The fundamental challenge in applying private key algorithms is keeping the private key private — or, to put it another way, exchanging keys without letting an interested eavesdropper see them. This may seem like an insoluble problem; you can't establish keys over an insecure channel, and you can't establish a secure channel without keys. Perhaps surprisingly, there is a solution: public-key cryptography. With public-key algorithms, there are actually two keys, which are mathematically related such that an encrypt operation performed with one can only be decrypted using the other one. Furthermore, to be usable in a cryptography setting, it must be impossible, or at least mathematically infeasible, to compute one from the other after the fact. By far the most common public-key algorithm is the RSA algorithm, named after its inventors Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman. You may recall Rivest from Chapter 2 as the inventor of RC4.

You may notice a difference in the technical approach between this chapter and the last. Whereas symmetric/shared key algorithms are based on shifting and XORing bits, asymmetric/public key algorithms are based entirely on properties of natural numbers. Whereas symmetric encryption algorithms aim to be as complex as their designers can get away with while still operating reasonably quickly, public-key cryptography algorithms are constrained by their own mathematics. In general, public-key cryptography aims to take advantage of problems that computers are inherently bad at and as a result don't translate nearly as easily to the domain of programming as symmetric cryptography does. In fact, the bulk of this chapter simply examines how to perform arithmetic on arbitrarily large numbers. Once that's out of the way, the actual process of public key cryptography is surprisingly simple.

Understanding the Theory Behind the RSA Algorithm

The theory behind RSA public-key cryptosystems is actually very simple. The core is modulus arithmetic; that is, operations modulo a number. For example, you're most likely familiar with C's mod operator %; (x % 2) returns 0 if x is even and 1 if x is odd. RSA public-key cryptography relies on this property of a finite number set. If you keep incrementing, eventually you end up back where you started, just like the odometer of a car. Specifically, RSA relies on three numbers e, d, and n such that (me)d % n = m — here m is the message to be encrypted and converted to a number.

Not all numbers work this way; in fact, finding three numbers e, d, and n that satisfy this property is complex, and forms the core of the RSA specification. After you've found them, though, using them to encrypt is fairly straightforward. The number d is called the private key, and you should never share it with anybody. e and n together make up the public key, and you can make them available to anybody who cares to send you an encoded message. When the sender is ready to send you something that should remain private, he first converts the message into a number m and then computes me% n and sends you the result c. When you receive it, you then compute cd% n and, by the property stated above, you get back the original message m.

Pay special attention to the nomenclature here. Most people, when first introduced to the RSA algorithm, find it confusing and "backward" that encryption is done with the public key and decryption with the private key. However, if you think about it, it makes sense: The public key is the one that's shared with anybody, anywhere, and thus you can use it to encrypt messages. You don't care how many people can see your public key because it can only be used to encrypt messages that you alone can read. It's the decryption that must be done privately, thus the term private key.

The security of the system relies on the fact that even if an attacker has access to e and n — which he does because they're public — it's computationally infeasible for him to compute d. For this to be true, d and n have to be enormous — at least 512 bit numbers (which is on the order of 10154) — but most public key cryptosystems use even larger numbers. 1,024- or even 2,048-bit numbers are common.

As you can imagine, computing anything to the power of a 2,048-bit number is bound to be more than a bit computationally expensive. Most common computers these days are 32-bit architectures, meaning that they can only perform native computations on numbers with 32 or fewer bits. Even a 64-bit architecture isn't going to be able to deal with this natively. And even if you could find a 2,048-bit architecture, the interim results are on the order of millions of bits! To make this possible on any hardware, modern or futuristic, you need an arbitrary precision math module, and you need to rely on several tricks to both speed up things and minimize memory footprint.

Performing Arbitrary Precision Binary Math to Implement Public-Key Cryptography

Developing an arbitrary precision binary math module — one that can efficiently represent and process numbers on the order of 2,048 bits — is not difficult, although it's somewhat tedious at times. It's important that the numeric representation be constrained only by available memory and, in theory, virtual memory — that is, disk space (to oversimplify a bit). The number must be able to grow without bounds and represent, exactly, any size number. In theory, this is straightforward; any integer can be represented by an array of C chars, which are eight bits each. The least-significant-bit (LSB) of the next-to-last char represents 28, with the most-significant-bit (MSB) of the last being 27. As the integer being represented overflows its available space, more space is automatically allocated for it.

NOTE For a more detailed understanding of LSB and MSB, see Appendix A.

As such, define a new type, called huge, shown in Listing 3-1.

Listing 3-1: "huge.h" huge structure

typedef struct

{

unsigned int size;

unsigned char *rep;

}

huge;

Each huge is simply an arbitrarily-sized array of chars. As it's manipulated — added to, subtracted from, multiplied or divided by — its size will be dynamically adjusted to fit its contents so that the size member always indicates the current length of rep.

Implementing Large-Number Addition

Addition and subtraction are perhaps more complex than you might expect. After all, adding and subtracting numbers is fundamentally what computers do; you'd expect that it would be trivial to extend this out to larger numbers. However, when dealing with arbitrarily-sized numbers, you must deal with inputs of differing sizes and the possibility of overflow. A large-number add routine is shown in Listing 3-2.

Listing 3-2: "huge.c" add routine

/**

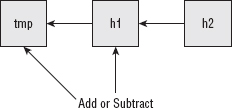

* Add two huges - overwrite h1 with the result.

*/

void add( huge *h1, huge *h2 )

{

unsigned int i, j;

unsigned int sum;

unsigned int carry = 0;

// Adding h2 to h1. If h2 is > h1 to begin with, resize h1.

if ( h2->size > h1->size )

{

unsigned char *tmp = h1->rep;

h1->rep = ( unsigned char * ) calloc( h2->size,

sizeof( unsigned char ) );

memcpy( h1->rep + ( h2->size - h1->size ), tmp, h1->size );

h1->size = h2->size;

free( tmp );

}

i = h1->size;

j = h2->size;

do

{

i--;

if ( j )

{

j--;

sum = h1->rep[ i ] + h2->rep[ j ] + carry;

}

else

{

sum = h1->rep[ i ] + carry;

}

carry = sum > 0xFF;

h1->rep[ i ] = sum;

}

while ( i );

if ( carry )

{

This routine adds the value of h2 to h1, storing the result in h1. It does so in three stages. First, allocate enough space in h1 to hold the result (assuming that the result will be about as big as h2). Second, the addition operation itself is actually carried out. Finally, overflow is accounted for.

Listing 3-3: "huge.c" add routine (size computation)

if ( h2->size > h1->size )

{

unsigned char *tmp = h1->rep;

h1->rep = ( unsigned char * ) calloc( h2->size,

sizeof( unsigned char ) );

memcpy( h1->rep + ( h2->size - h1->size ), tmp, h1->size );

h1->size = h2->size;

free( tmp );

}

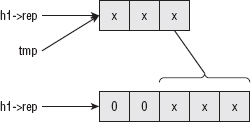

If h1 is already as long as or longer than h2, in Listing 3-3, nothing needs to be done. Otherwise, allocate enough space for the result in h1, and carefully copy the contents of h1 into the right position. Remember that the chars are read right-to-left, so if you allocate two new chars to hold the result, those chars need to be allocated at the beginning of the array, so the old contents need to be copied. Note the use of calloc here to ensure that the memory is cleared.

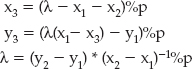

If h1 is three chars and h2 is five, you see something like Figure 3-1.

Figure 3-1: Large Integer alignment

Note that if h2 is smaller than h1, h1 is not changed at all, which means that h1 and h2 do not necessarily line up, that is, you can add a three-char number to a five-char number — so you have to be careful to account for this when implementing. This is the next step in the addition operation, shown in Listing 3-4.

Listing 3-4: "huge.c" add routine (addition loop)

i = h1->size; j = h2->size; do { i--; if ( j ) { j--; sum = h1->rep[ i ] + h2->rep[ j ] + carry; } else { sum = h1->rep[ i ] + carry; } carry = sum > 0xFF; h1->rep[ i ] = sum; } while ( i );

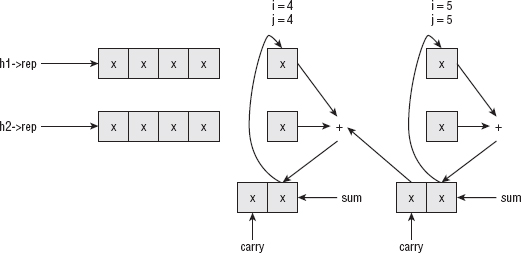

Most significantly, start at the end of each array, which, again, could be two different sizes, although h2 is guaranteed to be equal to or smaller in length than h1. Each char can be added independently, working right-to-left, keeping track of overflow at each step, and propagating it backward to the subsequent char, as shown in figure 3-2.

Figure 3-2: Large number addition

Note that the overflow cannot be more than one bit. To convince yourself that this is true, consider adding two four-bit numbers. The largest such (unsigned) number is 15 (binary 1111). If you add 15 and 15, you get:

As you can see, the result fits into five bits. Also notice that although if you add four bits to four bits and they overflow, they wrap. The wrapped result is the lower four bits of the correct response. Therefore, you can just add the two ints, keep track of whether they overflowed, and carry this overflow (of one bit) into the next addition.

Notice that sum — the temporary workspace for each addition operation — is itself an int. You check for overflow by comparing it to MAXCHAR (0xFF). Although the Intel instruction set does keep track of whether or not an operation — such as an add — overflowed and updates an overflow bit (also called a carry bit), the C language has never standardized access to such a bit, in spite of the fact that every microprocessor or microcontroller defines one. Because you don't have access to the overflow bit, you have to check for it on each add operation.

The only other point to notice is that you must continue until you've looped through all of the bytes of h1. You can't stop after you hit the last (actually, the first because you're working backward) byte of h2 because there may be a carry bit that needs to be propagated backward. In one extreme case, which actually does occur in cryptographic applications, h1 may be 0x01FFFFFEFF and h2 may be 0x0100. In this case, each byte of h1 overflows all the way to the very first. Thus, the while loop continues until i is 0, even if there's nothing left to do with h2 (for example, j = 0).

Finally, there's a possibility that you can get to the end of the add operation and still have a carry bit left over. If this is the case, you need to expand h1 by exactly one char and set its lower-order bit to 1 as shown in Listing 3-5.

Listing 3-5: "huge.c" add (overflow expansion)

// Still overflowed; allocate more space

if ( carry )

{

expand( h1 );

}

Here you call the function expand, shown in Listing 3-6, which is defined for precisely this purpose.

Listing 3-6: "huge.c" expand

/** * Extend the space for h by 1 char and set the LSB of that int * to 1. */ void expand( huge *h )

{ unsigned char *tmp = h->rep; h->size++; h->rep = ( unsigned char * ) calloc( h->size, sizeof( unsigned char ) ); memcpy( h->rep + 1, tmp, ( h->size - 1 ) * sizeof( unsigned char ) ); h->rep[ 0 ] = 0x01; free( tmp ); }

The code in Listing 3-6 should look familiar. It is a special case of the expansion of h1 that was done when h2 was larger than h1. In this case, the expansion is just a bit simpler because you know you're expanding by exactly one char.

Implementing Large-Number Subtraction

Another thing to note about this add routine — and the huge datatype in general — is that you use unsigned chars for your internal representation. That means that there's no concept of negative numbers or two's-complement arithmetic. As such, you need a specific subtract routine, shown in Listing 3-7.

Listing 3-7: "huge.c" subtract

static void subtract( huge *h1, huge *h2 )

{

int i = h1->size;

int j = h2->size;

int difference; // signed int - important!

unsigned int borrow = 0;

do

{

i--;

if ( j )

{

j--;

difference = h1->rep[ i ] - h2->rep[ j ] - borrow;

}

else

{

difference = h1->rep[ i ] - borrow;

}

borrow = ( difference < 0 ) ;

h1->rep[ i ] = difference;

}

while ( i );

if ( borrow && i ) { if ( !( h1->rep[ i - 1 ] ) ) // Don't borrow i { printf( "Error, subtraction result is negative\n" ); exit( 0 ); } h1->rep[ i - 1 ]--; } contract( h1 ); }

The subtract routine looks a lot like the add routine, but in reverse. Note that there's no allocation of space at the beginning. Because you're subtracting, the result always uses up less space than what you started with. Also, there's no provision in this library yet for negative numbers, so behavior in this case is undefined if h2 is greater than h1.

Otherwise, subtracting is pretty much like adding: You work backward, keeping track of the borrow from the previous char at each step. Again, although the subtraction operation wraps if h2->rep[ j ] > h1->rep[ i ], the wrap ends up in the right position. To see this, consider the subtraction 30 – 15 (binary 11110 – 1111). To keep things simple, imagine that a char is four bits. The integer 30 then takes up two four-bit chars and is represented as:

(0001 1110) : (1 14 )

whereas 15 takes up one char and is represented as 1111 (15). When subtracting, start by subtracting 15 from 14 and end up "wrapping" back to 15 as illustrated in Table 3-1.

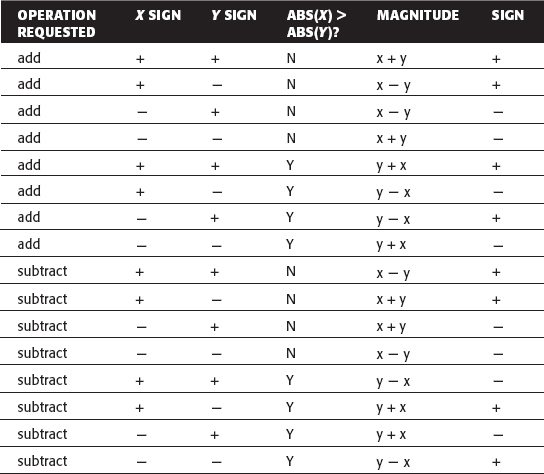

Table 3-1: Subtraction Wrapping Behavior

Because 15 is greater than 14, you set the borrow bit and subtract one extra from the preceding char, ending up with the representation (0 15) (0000 1111), which is the correct answer.

To be a bit more memory efficient, you should also contract the response before returning. That is, look for extraneous zero ints on the left side and remove them, as shown in Listing 3-8.

Listing 3-8: "huge.c" contract

/**

* Go through h and see how many of the left-most bytes are unused.

* Remove them and resize h appropriately.

*/

void contract( huge *h )

{

int i = 0;

while ( !( h->rep[ i ] ) && ( i < h->size ) ) { i++; }

if ( i && i < h->size )

{

unsigned char *tmp = &h->rep[ i ];

h->rep = ( unsigned char * ) calloc( h->size - i,

sizeof( unsigned char ) );

memcpy( h->rep, tmp, h->size - i );

h->size -= i;

}

}

This happens in two steps. First, find the leftmost non-zero char, whose position is contained in i. Second, resize the array representation of h. This works, obviously, just like expansion but in reverse.

As shown earlier, addition and subtraction are somewhat straightforward; you can take advantage of the underlying machine architecture to a large extent; most of your work involves memory management and keeping track of carries and borrows.

Implementing Large-Number Multiplication

Multiplication and division aren't quite so easy, unfortunately. If you tried to multiply "backward" one char at a time as you did with addition, you'd never even come close to getting the right result. Of course, multiplication is just successive adding — multiplying five by three involves adding five to itself three times — 5 + 5 + 5 = 3 * 5 = 15. This suggests an easy implementation of a multiplication algorithm. Remember, though, that you're going to be dealing with astronomical numbers. Adding five to itself three times is not a terribly big deal — it wouldn't even be a big deal if you did it in the reverse and added three to itself five times. But adding a 512-bit number to itself 2512 times would take ages, even on the fastest desktop computer. As a result, you have to look for a way to speed this up.

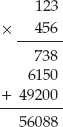

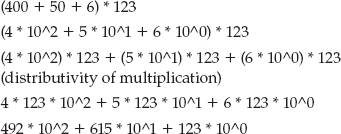

When you were in elementary school, you were probably taught how to do multi-digit multiplication like this:

You may have never given much thought to what you were doing, or why this works, but notice that you've shortened what might otherwise have been 123 addition operations down to 3. A more algebraic way to represent this same multiplication is

Because multiplying by 10n just involves concatenating n zeros onto the result, this is simply

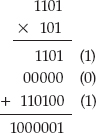

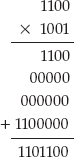

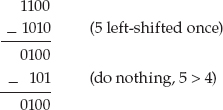

What you actually did at each step was to first multiply 123 by one of the digits of 456, and then shift it left — that is, concatenate a zero. Can you do the same thing with binary multiplication? Yes, you can. In fact, it's significantly easier because the interim multiplications — the multiplication by the digits of 456 — are unnecessary. You either multiply by 1 or 0 at each step, so the answer is either the first number or just 0. Consider the multiplication of 12 (binary 1100) by 9 (1001):

Here, the 12 is left-shifted 0 times and 3 times, because the bits at positions 0 and 3 of the multiplicand 1001 are set. The two resulting values — 1100 and 1100000 — are added together to produce 26 + 25 + 23 + 22 = 108, the expected answer.

Now you've reduced what might have been an O(2n) operation to a simple O(n) operation, where n is the number of bits of the smaller of the two operators. In practice, it really doesn't matter if you try to optimize and use the smaller number to perform the multiplication, so this implementation just takes the numbers as given.

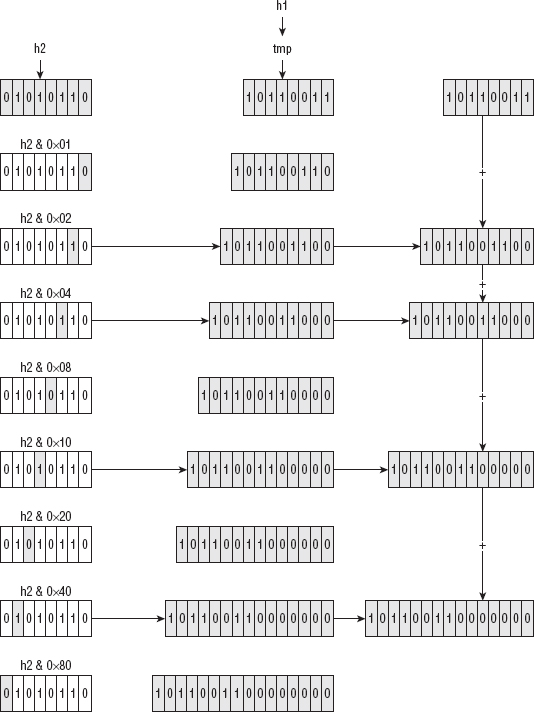

In code, this algorithm is implemented as shown in Listing 3-9 and illustrated in Figure 3-3.

Listing 3-9: "huge.c" multiply

/**

* Multiply h1 by h2, overwriting the value of h1.

*/

void multiply( huge *h1, huge *h2 )

{

unsigned char mask;

unsigned int i;

huge temp;

set_huge( &temp, 0 );

copy_huge( &temp, h1 );

set_huge( h1, 0 );

i = h2->size;

do

{

i--; for ( mask = 0x01; mask; mask <<= 1 ) { if ( mask & h2->rep[ i ] ) { add( h1, &temp ); } left_shift( &temp ); } } while ( i ); }

First, notice that you need a couple of utility routines: copy_huge, free_huge, and set_huge. The implementations of the first two are straightforward in Listing 3-10.

Listing 3-10: "huge.c" copy_huge and free_huge

void copy_huge( huge *tgt, huge *src )

{

if ( tgt->rep )

{

free( tgt->rep );

}

tgt->size = src->size;

tgt->rep = ( unsigned char * )

calloc( src->size, sizeof( unsigned char ) );

memcpy( tgt->rep, src->rep,

( src->size * sizeof( unsigned char ) ) );

}

void free_huge( huge *h )

{

if ( h->rep )

{

free( h->rep );

}

}

To be more generally useful, set_huge is perhaps a bit more complex than you would expect. After all, what you're doing here is copying an int into a byte array. However, you need to be as space-efficient as possible, so you need to look at the int in question and figure out the minimum number of bytes that it can fit into. Note that this space-efficiency isn't merely a performance concern; the algorithms illustrated here don't work at all if the huge presented includes extraneous leading zeros. And, of course, you have to deal with little-endian/big-endian conversion. You can accomplish this as shown in Listing 3-11.

Figure 3-3: Large number multiplication

Listing 3-11: "huge.c" set_huge

void set_huge( huge *h, unsigned int val ) { unsigned int mask, i, shift; h->size = 4; // Figure out the minimum amount of space this "val" will take // up in chars (leave at least one byte, though, if "val" is 0). for ( mask = 0xFF000000; mask > 0x000000FF; mask >>=8 ) { if ( val & mask ) { break; } h->size--; } h->rep = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( h->size ); // Now work backward through the int, masking off each 8-bit // byte (up to the first 0 byte) and copy it into the "huge" // array in big-endian format. mask = 0x000000FF; shift = 0; for ( i = h->size; i; i-- ) { h->rep[ i - 1 ] = ( val & mask ) >> shift; mask <<= 8; shift += 8; } }

Notice that at the top of the multiply routine you see

set_huge( & temp, 0 );

but then you overwrite it immediately with a call to copy_huge. This is necessary because the huge temp is allocated on the stack and is initialized with garbage values. Because copy_huge immediately tries to free any pointer allocated, you need to ensure that it's initialized to NULL. set_huge accomplishes this.

Start multiplying by setting aside a temporary space for the left-shifted first operand, copy that into the temporary space, and reset h1 to 0. Then, loop through each char of h2 (backward, again), and check each bit of each char. If the bit is a 1, add the contents of temp to h1. If the bit is a zero, do nothing. In either case, left-shift temp by one position. Left-shifting a huge is, of course, a separate operation that works on one char at a time, right-to-left.

Listing 3-12: "huge.c" left_shift

void left_shift( huge *h1 ) { int i; int old_carry, carry = 0; i = h1->size; do { i--; old_carry = carry; carry = ( h1->rep[ i ] & 0x80 ) == 0x80; h1->rep[ i ] = ( h1->rep[ i ] << 1 ) | old_carry; // Again, if C exposed the overflow bit... } while ( i ); if ( carry ) { expand( h1 ); } }

Because each char can overflow into the next-leftmost char, it's necessary to manually keep track of the carry bit and expand the result if it overflows, just as you did for addition.

This double-and-add approach to multiplication is important when dealing with binary arithmetic. In fact, you've seen it once before, in Chapter 2, when you implemented AES multiplication in terms of the dot and xtime operations. It comes up later when I redefine multiplication yet again in the context of elliptic curves. However, this is not the most efficient means of performing binary multiplication. Karatsuba's algorithm, originally published by Anatolii Karatsuba in the "Proceedings of the USSR Academy of Sciences" in 1962, is actually much faster, albeit much more complicated to implement — I won't cover it here, but you can consult a book on advanced algorithms if you're curious. However, this routine runs well enough on modern hardware, so just leave it as is.

Implementing Large-Number Division

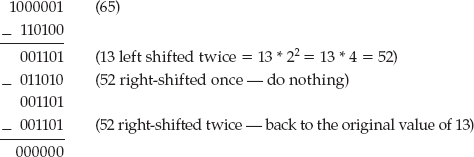

Finally, what about division? Division is, of course, the inverse of multiplication, so it makes sense that you ought to be able to reverse the multiplication process and perform a division. Consider the multiplication of 13 by 5, in binary:

To reverse this, you have as input 100001 and 1101, and you want to recover 101. You can do this by subtracting and right-shifting:

If you just keep track of which iterations involved a subtraction — that is, which right-shifts yielded a value less than the current value of the dividend — you get "subtract" "nothing" "subtract" or, in binary, 101, which is exactly the value you were looking for.

Of course, there's one immediate problem with implementing this: How do you know to left-shift 13 twice before subtracting it? You could look at the bit-length of the dividend — 65 in the example — and compare it to the bit-length of the divisor (13), which tells you that you need to left-shift by two positions. However, finding the bit-length of a value is somewhat non-trivial. An easier (and faster) approach is just to keep left-shifting the divisor until it's greater than the dividend.

Finally, you're doing integer division here — there's no compensation for uneven division. So what happens if you divide 14 by, say, 5?

Now you get a quotient of 10 (2) and the dividend, at the end of the operation, is 4, which happens to be the remainder of the division of 14 by 5. Remember the discussion of the importance of modular arithmetic to the RSA cryptosystem? As it turns out, you almost never call divide for the quotient. Instead, you are interested in the remainder (or modulus). The complete division routine is implemented in Listing 3-13.

Listing 3-13: "huge.c" divide

/**

* dividend = numerator, divisor = denominator

*

* Note that this process destroys divisor (and, of course,

* overwrites quotient). The dividend is the remainder of the

* division (if that's important to the caller). The divisor will

* be modified by this routine, but it will end up back where it

* "started".

*/

void divide( huge *dividend, huge *divisor, huge *quotient )

{

int bit_size, bit_position;

// "bit_position" keeps track of which bit, of the quotient,

// is being set or cleared on the current operation.

bit_size = bit_position = 0;

// First, left-shift divisor until it's >= than the dividend

while ( compare( divisor, dividend ) < 0 )

{

left_shift( divisor );

bit_size++;

}

// overestimates a bit in some cases

quotient->size = ( bit_size / 8 ) + 1;

quotient->rep = ( unsigned char * )

calloc(quotient->size, sizeof( unsigned char ) );

memset( quotient->rep, 0, quotient->size );

bit_position = 8 - ( bit_size % 8 ) - 1;

do

{

if ( compare( divisor, dividend ) <= 0 )

{

subtract( dividend, divisor ); // dividend -= divisor

quotient->rep[ ( int ) ( bit_position / 8 ) ] |=

( 0x80 >> ( bit_position % 8 ) );

}

if ( bit_size )

{

Start by left shifting the divisor until it's greater than or equal to the dividend. Most of the time, this means you "overshoot" a bit, but that's not a problem because you compare again when you start the actual division.

while ( compare( divisor, dividend ) < 0 )

{

left_shift( divisor );

bit_size++;

}

Comparing Large Numbers

Notice the call to the compare function. Remember the subtract function a while ago — in theory, you could just call subtract here, and check to see if the result is negative. Two problems with that approach are that a) subtract overwrites its first operator, and b) you don't have any provision for negative numbers. Of course, you could work around both of these, but a new compare function, shown in Listing 3-14, serves better.

Listing 3-14: "huge.c" compare

/**

* Compare h1 to h2. Return:

* 0 if h1 == h2

* a positive number if h1 > h2

* a negative number if h1 < h2

*/

int compare( huge *h1, huge *h2 )

{

int i, j;

if ( h1->size > h2->size )

{

return 1;

}

if ( h1->size < h2->size )

{

return −1;

}

// Otherwise, sizes are equal, have to actually compare.

// only have to compare "hi-int", since the lower ints // can't change the comparison. i = j = 0; // Otherwise, keep searching through the representational integers // until one is bigger than another - once we've found one, it's // safe to stop, since the "lower order bytes" can't affect the // comparison while ( i < h1->size && j < h2->size ) { if ( h1->rep[ i ] < h2->rep[ j ] ) { return −1; } else if ( h1->rep[ i ] > h2->rep[ j ] ) { return 1; } i++; j++; } // If we got all the way to the end without a comparison, the // two are equal return 0; }

If the sizes of the huges to be compared are different, you don't have to do any real comparison. A five-char huge always has a larger value than a three-char huge, assuming you've been diligent in compressing representations to remove leading 0's:

if ( h1->size > h2->size )

{

return 1;

}

if ( h1->size < h2->size )

{

return −1;

}

Otherwise, you need to do a char-by-char comparison. You can safely stop at the first non-equal char, though. If the first char of h1 is larger than the first char of h2, the lower-order integers can't change the comparison.

while ( i < h1->size && j < h2->size )

{

if ( h1->rep[ i ] < h2->rep[ j ] )

{

return −1;

}

Of course, if you go through both h1 and h2, and they're both the same size, and each char is equal, then they both represent equal numbers.

Referring to the original divide function, the second step is to allocate space for the quotient by keeping track of how many times the dividend was left shifted. The quotient can't be any bigger than this, which overallocates just a bit, but not so much that you need to worry about it.

quotient->size = ( bit_size / 8 ) + 1; quotient->rep = ( unsigned char * ) calloc( quotient->size, sizeof( unsigned char ) ); memset( quotient->rep, 0, quotient->size );

Finally, start the "compare and subtract" loop. If the current dividend, after being left-shifted, is less than the current divisor, then the quotient should have that bit position set, and the current dividend should be subtracted from the divisor. In all cases, the dividend should be right-shifted by one position for the next loop iteration. Although the comparison, subtraction and right-shift operators are easy to understand — they just call the compare and subtract functions coded earlier — the setting of the "current" bit of the quotient is somewhat complex:

quotient->rep[ ( int ) ( bit_position / 8 ) ] |=

( 0x80 >> ( bit_position % 8 ) );

Remember that bit_position is absolute. If quotient is a 128-bit number, bit_position ranges from 0 to 127. So, in order to set the correct bit, you need to determine which char this refers to in the array of chars inside quotient and then determine which bit inside that char you need to set (that is, or). This may look familiar; this is essentially the SET_BIT macro developed in Chapter 2.

Finally, right-shift the divisor at each step except the last:

if ( bit_size )

{

right_shift( divisor );

}

Technically, you could get away with always right-shifting and not skipping this on the last step, but by doing this, you guarantee that divisor is reset to the value that was passed in to the function originally. This is useful behavior because you are calling "divide" over and over again with the same argument, which keeps you from having to make a temporary copy of the divisor.

right_shift, the reverse of left_shift, is shown in Listing 3-15.

Listing 3-15: "huge.c" right_shift

static void right_shift( huge *h1 ) { int i; unsigned int old_carry, carry = 0; i = 0; do { old_carry = carry; carry = ( h1->rep[ i ] & 0x01 ) << 7; h1->rep[ i ] = ( h1->rep[ i ] >> 1 ) | old_carry; } while ( ++i < h1->size ); contract( h1 ); }

Optimizing for Modulo Arithmetic

One optimization you might as well make is to allow the caller to indicate that the quotient is unimportant. For public-key cryptography operations you never actually care what the quotient is; you're interested in the remainder, which the dividend operator is turned into after a call to divide. Extend divide just a bit to enable the caller to pass in a NULL pointer for quotient that indicates the quotient itself should not be computed, as shown in Listing 3-16.

Listing 3-16: "huge.c" divide

void divide( huge *dividend, huge *divisor, huge *quotient )

{

int i, bit_size, bit_position;

bit_size = bit_position = 0;

while ( compare( divisor, dividend ) < 0 )

{

left_shift( divisor );

bit_size++;

}

if ( quotient )

{

quotient->size = ( bit_size / 8 ) + 1;

quotient->rep = ( unsigned char * )

calloc( quotient->size, sizeof( unsigned char ) );

memset( quotient->rep, 0, quotient->size );

}

bit_position = 8 - ( bit_size % 8 ) - 1; do { if ( compare( divisor, dividend ) <= 0 ) { subtract( dividend, divisor ); if ( quotient ) { quotient->rep[ ( int ) ( bit_position / 8 ) ] |= ( 0x80 >> ( bit_position % 8 ) ); } } if ( bit_size ) { right_shift( divisor ); } bit_position++; } while ( bit_size-- ); }

One note about the choice to use chars – that is, bytes — instead of ints for the huge arrays: You could reduce the number of add and subtract operations by a factor of four if you represent huges as integer arrays rather than char arrays. This is actually how OpenSSL, GMP, and Java implement their own arbitrary-precision math libraries. However, this introduces all sorts of problems later on when you try to convert from big endian to little endian. You also need to keep close track of the exact non-padded size of the huge. A three-byte numeral uses up one int; however, you'd need to remember that the leading byte of that int is just padding. RSA implementations in particular are very finicky about result length; if they expect a 128-byte response and you give them 129 bytes, they error out without even telling you what you did wrong.

Using Modulus Operations to Efficiently Compute Discrete Logarithms in a Finite Field

The modulus operation — that is, the remainder left over after a division operation — is important to modern public-key cryptography and is likely going to remain important for the foreseeable future. In general, and especially with respect to the algorithms currently used in SSL/TLS, public-key operations require that all mathematical operations — addition, subtraction, multiplication, division — be performed in such a finite field. In simple terms, this just means that each operation is followed by a modulus operation to truncate it into a finite space.

Given the importance of modulus arithmetic to public-key cryptography, it's been the subject of quite a bit of research. Every computational cycle that can be squeezed out of a modulus operation is going to go a long way in speeding up public-key cryptography operations. There are a couple of widely implemented ways to speed up cryptography operations: the Barrett reduction and the Montgomery reduction. They work somewhat similarly; they trade a relatively time-consuming up-front computation for faster modulus operations. If you're going to be computing a lot of moduli against a single value — which public-key cryptography does — you can save a significant amount of computing time by calculating and storing the common result.

I don't cover these reductions in detail here. The divide operation shown earlier computes moduli fast enough for demonstration purposes, although you can actually observe a noticeable pause whenever a private-key operation occurs. If you're interested, the Barrett reduction is described in detail in the journal "Advances in Cryptology '86" (http://www.springerlink.com/content/c4f3rqbt5dxxyad4/), and the Montgomery reduction in "Math Computation vol. 44" (http://www.jstor.org/pss/2007970).

Encryption and Decryption with RSA

You now have enough supporting infrastructure to implement RSA encryption and decryption. How the exponents d and e or the corresponding modulus n are computed has not yet been discussed, but after you've correctly determined them, you just need to pass them into the encrypt or decrypt routine. How you specify the message m is important; for now, just take the internal binary representation of the entire message to be encrypted as m. After you have done this, you can implement encryption as shown in Listing 3-17.

Listing 3-17: "rsa.c" rsa_compute

/**

* Compute c = m^e mod n.

*/

void rsa_compute( huge *m, huge *e, huge *n, huge *c )

{

huge counter;

huge one;

copy_huge( c, m );

set_huge( &counter, 1 );

set_huge( &one, 1 );

while ( compare( &counter, e ) < 0 )

{

multiply( c, m );

add( &counter, &one );

}

Remember that encryption and decryption are the exact same routines, just with the exponents switched; you can use this same routine to encrypt by passing in e and decrypt by passing in d. Just keep multiplying m by itself (notice that m was copied into c once at the beginning) and incrementing a counter by 1 each time until you've done it e times. Finally, divide the whole mess by n and the result is in c. Here's how you might call this:

huge e, d, n, m, c; set_huge( &e, 79 ); set_huge( &d, 1019 ); set_huge( &n, 3337 ); set_huge( &m, 688 ); rsa_compute( &m, &e, &n, &c ); printf( "Encrypted to: %d\n", c.rep[ 0 ] ); set_huge( &m, 0 ); rsa_compute( &c, &d, &n, &m ); printf( "Decrypted to: %d\n", m.rep[ 0 ] );

Encrypting with RSA

Because this example uses small numbers, you can verify the accuracy by just printing out the single int representing c and m:

Encrypted to: 1570 Decrypted to: 688

The encrypted representation of the number 688 is 1,570. You can decrypt and verify that you get back what you put in.

However, this public exponent 79 is a small number for RSA, and the modulus 3,337 is microscopic — if you used numbers this small, an attacker could decipher your message using pencil and paper. Even with these small numbers, 68879 takes up 1,356 bytes. And this is for a small e. For reasons you see later, a more common e value is 65,537.

NOTE Note that everybody can, and generally does, use the same e value as long as the n — and by extension, the d — are different.

A 32-bit integer raised to the power of 65,537 takes up an unrealistic amount of memory. I tried this on my computer and, after 20 minutes, I had computed 68849422, which took up 58,236 bytes to represent. At this point, my computer finally gave up and stopped allocating memory to my process.

First, you need to get the number of multiplications under control. If you remember when I first discussed huge number multiplication, the naïve implementation that would have involved adding a number m to itself n times to compute m × n was rejected. Instead, you developed a technique of doubling and adding. Can you do something similar with exponentiation? In fact, you can. Instead of doubling and adding, square and multiply. By doing so, you reduce 65,537 operations down to log2 65,537 = 17 operations.

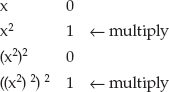

Fundamentally, this works the same as double and add; cycle through the bits in the exponent, starting with the least-significant bit. If the bit position is 1, perform a multiplication. At each stage, square the running exponent, and that's what you multiply by at the 1 bits. Incidentally, if you look at the binary representation of 65,537 = 10000000000000001, you can see why it's so appealing for public-key operations; it's big enough to be useful, but with just two 1 bits, it's also quick to operate on. You square m 17 times, but only multiply the first and 17th results.

NOTE Why 65,537? Actually, it's the smallest prime number (which e must be) that can feasibly be used as a secure RSA public-key exponent. There are only four other prime numbers smaller than 65,537 that can be represented in just two 1 bits: 3, 5, 17, and 257, all of which are far too small for the RSA algorithm. 65,537 is also the largest such number that can be represented in 32 bits. You could, if you were so inclined, take advantage of this and speed up computations by using native arithmetic operations.

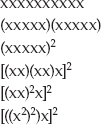

If it's not clear that this should work for exponentiation as well as for multiplication, consider x10. This, expanded, is

Notice how you can successively split the x's in half, reducing them to squaring operations each time. It should be clear that you can do this with any number; you may have a spare x left over, if the exponent is an odd number, but that's OK.

If you look at the binary representation of the decimal number 10 (1010 in binary) and you work backward through its binary digits, squaring at each step, you get:

multiplying the two "hits" together, you get x2((x2)2)2 or [((x2)2)x]2 which is what you got when you deconstructed decimal 10 in the first place.

Listing 3-18 shows how you can implement this in code. Compare this to the implementation of multiply in Listing 3-9.

Listing 3-18: "huge.c" exponentiate

/**

* Raise h1 to the power of exp. Return the result in h1.

*/

void exponentiate( huge *h1, huge *exp )

{

int i = exp->size, mask;

huge tmp1, tmp2;

set_huge( &tmp1, 0 );

set_huge( &tmp2, 0 );

copy_huge( &tmp1, h1 );

set_huge( h1, 1 );

do

{

i--;

for ( mask = 0x01; mask; mask <<= 1 )

{

if ( exp->rep[ i ] & mask )

{

multiply( h1, &tmp1 );

}

// Square tmp1

copy_huge( &tmp2, &tmp1 );

multiply( &tmp1, &tmp2 );

}

}

while ( i );

free_huge( &tmp1 );

free_huge( &tmp2 );

}

This works; you've drastically reduced the number of multiplications needed to compute an exponentiation. However, you still haven't addressed the primary problem of memory consumption. Remember that you allocated 56 kilobytes of memory to compute an interim result — just throw it away when you compute the modulus at the end of the operation. Is this really necessary? As it turns out, it's not. Because the modulus operator is distributive — that is, (abc) % n = [a % n * b % n * c % n] % n, you can actually compute the modulus at each step. Although this results in more computations, the memory savings are drastic. Remember that multiplications take as many addition operations as there are bits in the representation as well, so reducing the size of the numbers being multiplied actually speeds things up considerably.

Listing 3-19, then, is the final RSA computation (me) % n, with appropriate speed-ups.

Listing 3-19: "huge.c" mod_pow

/**

* Compute c = m^e mod n.

*

* Note that this same routine is used for encryption and

* decryption; the only difference is in the exponent passed in.

* This is the "exponentiate" algorithm, with the addition of a

* modulo computation at each stage.

*/

void mod_pow( huge *h1, huge *exp, huge *n, huge *h2 )

{

unsigned int i = exp->size;

unsigned char mask;

huge tmp1, tmp2;

set_huge( &tmp1, 0 );

set_huge( &tmp2, 0 );

copy_huge( &tmp1, h1 );

set_huge( h2, 1 );

do

{

i--;

for ( mask = 0x01; mask; mask <<= 1 )

{

if ( exp->rep[ i ] & mask )

{

multiply( h2, &tmp1 );

divide( h2, n, NULL );

}

// square tmp1

copy_huge( &tmp2, &tmp1 );

multiply( &tmp1, &tmp2 ); divide( &tmp1, n, NULL ); } } while ( i ); free_huge( &tmp1 ); free_huge( &tmp2 ); // Result is now in "h2" }

Besides the introduction of a call to divide, for its side effect of computing a modulus, and the substitution of m and c for h1, Listing 3-19 is identical to the exponentiate routine in Listing 3-18. This works, and performs reasonably quickly, using a reasonable amount of memory, even for huge values of m, e, and n. Given a message m and a public key e and n, you encrypt like this:

huge c; mod_pow( &m, &e, &n, &c );

Decrypting with RSA

Decryption is identical, except that you swap e with d and of course you switch c and m:

huge m; mod_pow( &c, &d, &n, &e );

There is one subtle, but fatal, security flaw with this implementation of decrypt, however. Notice that you multiply and divide log2 d times as you iterate through the bits in d looking for 1 bits. This is not a problem. However, you do an additional multiply and divide at each 1 bit in the private exponent d. These multiply and divide operations are reasonably efficient, but not fast. In fact, they take long enough that an attacker can measure the time spent decrypting and use this to determine how many 1 bits were in the private exponent, which is called a timing attack. This information drastically reduces the number of potential private keys that an attacker has to try before finding yours. Remember, part of the security of the RSA public key cryptosystem is the infeasibility of a brute-force attack. The most straightforward way to correct this is to go ahead and perform the multiply and divide even at the 0 bits of the exponent, but just throw away the results. This way, the attacker sees a uniform duration for every private key operation. Of course, you should only do this for the private-key operations. You don't care if an attacker can guess your public key (it's public, after all).

It may occur to you that, if the modulus operation is distributive throughout exponentiation, it must also be distributive throughout multiplication and even addition. It is perfectly reasonable to define "modulus-aware" addition and multiplication routines and call those from exponentiation routine. This would actually negate the need for the division at each step of the exponentiation. There are actually many additional speed-ups possible; real implementations, of course, enable all of these. However, this code is performant enough.

Encrypting a Plaintext Message

So, now that you have a working RSA encrypt and decrypt algorithm, you're still missing two important pieces of the puzzle. The first is how keys are generated and distributed. The topic of key distribution actually takes up all of Chapter 5. The second topic is how to convert a plaintext message into a number m to be passed into rsa_compute. Each rsa_compute operation returns a result mod n. This means that you can't encrypt blocks larger than n without losing information, so you need to chop the input up into blocks of length n or less. On the flip side, if you want to encrypt a very small amount of data, or the non-aligned end of a long block of data, you need to pad it to complicate brute-force attacks.

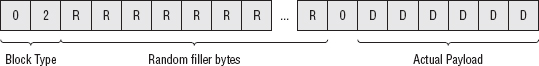

Just like the previous chapter's symmetric algorithms, RSA works on blocks of data. Each block includes a header and some padding (of at least 11 bytes), so the resulting input blocks are modulus_length −11 bytes minimum. The header is pretty simple: It's a 0 byte, followed by a padding identifier of 0, 1, or 2. I examine the meaning of the different padding bytes later. For RSA encryption, always use padding identifier 2, which indicates that the following bytes, up to the first 0 byte, are padding and should be discarded. Everything following the first 0 byte, up to the length of the modulus n in bytes, is data.

NOTE Unlike the symmetric algorithms of the previous chapter, RSA pads at the beginning of its block.

To implement this in code, follow these steps:

- Define an rsa_key type that holds the modulus and exponent of a key, as shown in Listing 3-20. Notice that it doesn't matter whether it's a public or a private key. Each includes a modulus and an exponent; the only difference is which exponent.

- Define an rsa_encrypt routine that takes in the data to be encrypted along with the public key. Notice also that the output is a pointer to a pointer. Due to the way padding works, it's difficult for the caller to figure out how much space the decrypted data takes up (a one-byte payload could encrypt to a 256-byte value!). As a result, Listing 3-21 allocates space in the target output array.

Listing 3-21: "rsa.c" rsa_encrypt

/** * The input should be broken up into n-bit blocks, where n is the * length in bits of the modulus. The output will always be n bits * or less. Per RFC 2313, there must be at least 8 bytes of padding * to prevent an attacker from trying all possible padding bytes. * * output will be allocated by this routine, must be freed by the * caller. * * returns the length of the data encrypted in output */ int rsa_encrypt( unsigned char *input, unsigned int len, unsigned char **output, rsa_key *public_key ) { int i; huge c, m; int modulus_length = public_key->modulus->size; int block_size; unsigned char *padded_block = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( modulus_length ); int encrypted_size = 0; *output = NULL; while ( len ) { encrypted_size += modulus_length; block_size = ( len < modulus_length - 11 ) ? len : ( modulus_length - 11 ); memset( padded_block, 0, modulus_length ); memcpy( padded_block + ( modulus_length - block_size ), input, block_size ); // set block type padded_block[ 1 ] = 0x02; for ( i = 2; i < ( modulus_length - block_size - 1 ); i++ ) { // TODO make these random padded_block[ i ] = i; }load_huge( &m, padded_block, modulus_length ); mod_pow( &m, public_key->exponent, public_key->modulus, &c ); *output = ( unsigned char * ) realloc( *output, encrypted_size ); unload_huge( &c, *output + ( encrypted_size - modulus_length ), modulus_length ); len -= block_size; input += block_size; free_huge( &m ); free_huge( &c ); } free( padded_block ); return encrypted_size; }

- Figure out how long the block size is. It should be the same as the length of the modulus, which is usually 512, 1024, or 2048 bits. There's no fundamental reason why you couldn't use any other modulus lengths if you wanted, but these are the usual lengths. The encrypted result is the same length as the modulus:

int modulus_length = public_key->modulus->size;

- Allocate that much space and then fill up this block with the padding, as described earlier, and encrypt it using rsa_compute.

unsigned char *padded_block = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( modulus_length );

- Operate on the input data until there is no more. Figure out if you're dealing with a whole block (modulus-length – 11 bytes) or less than that, copy the input to the end of the block (remember that in RSA, the padding goes at the beginning), and set the padding type to 2.

while ( len ) { encrypted_size += modulus_length; block_size = ( len < modulus_length - 11 ) ? len : ( modulus_length - 11 ); - Technically speaking, you ought to follow this with random bytes of padding, up to the beginning of the data. Throw security out the window here, and just pad with sequential bytes:

for ( i = 2; i < ( modulus_length - block_size - 1 ); i++ ) { // TODO make these random padded_block[ i ] = i; } - RSA-encrypt the padded block:

load_huge( &m, padded_block, modulus_length ); rsa_compute( &m, public_key->exponent, public_key->modulus, &c );

Notice the new function load_huge. This function essentially just memcpy's a block into a huge, as shown in Listing 3-22:

Listing 3-22: "huge.c" load_huge

/** * Given a byte array, load it into a "huge", aligning integers * appropriately */ void load_huge( huge *h, const unsigned char *bytes, int length ) { while ( !( *bytes ) ) { bytes++; length--; } h->size = length; h->rep = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( length ); memcpy( h->rep, bytes, length ); }NOTE One interesting point to note here is that you start by skipping over the zero bytes. This is an important compatibility point. Most SSL implementations (including OpenSSL, GnuTLS, NSS and JSSE) zero-pad positive numbers so that they aren't interpreted as negative numbers by a two's-complement-aware large number implementation. This one isn't, and zero-padding actually confuses the comparison routine, so just skip them.

- Returning to the rsa_encrypt function; now you've encrypted the input block, and the result is in huge c. Convert this huge c into a byte array:

*output = ( unsigned char * ) realloc( *output, encrypted_size ); unload_huge( &c, *output + ( encrypted_size - modulus_length ), modulus_length ); - Allocate space for the output at the end of the output array — if this is the first iteration, the end is the beginning — and unload_huge, shown in Listing 3-23, into it.

- Adjust len and input and free the previously allocated huges for the next iteration.

len -= block_size; input += block_size; free_huge( &m ); free_huge( &c ); }

If the input is less than modulus_length – 11 bytes (which, for SSL/TLS, is actually always the case), there will only be one iteration.

Decrypting an RSA-Encrypted Message

Decryption is, of course, the opposite.

You operate on blocks of modulus_length at a time, decrypt the block — again using rsa_compute, but this time with the private key — and remove the padding, as shown in Listing 3-24.

Listing 3-24: "rsa.c" rsa_decrypt

/**

* Convert the input into key-length blocks and decrypt, unpadding

* each time.

* Return −1 if the input is not an even multiple of the key modulus

* length or if the padding type is not "2", otherwise return the

* length of the decrypted data.

*/

int rsa_decrypt( unsigned char *input,

unsigned int len,

unsigned char **output,

rsa_key *private_key )

{ int i, out_len = 0; huge c, m; int modulus_length = private_key->modulus->size; unsigned char *padded_block = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( modulus_length ); *output = NULL; while ( len ) { if ( len < modulus_length ) { fprintf( stderr, "Error - input must be an even multiple \ of key modulus %d (got %d)\n", private_key->modulus->size, len ); free( padded_block ); return −1; } load_huge( &c, input, modulus_length ); mod_pow( &c, private_key->exponent, private_key->modulus, &m ); unload_huge( &m, padded_block, modulus_length ); if ( padded_block[ 1 ] > 0x02 ) { fprintf( stderr, "Decryption error or unrecognized block \ type %d.\n", padded_block[ 1 ] ); free_huge( &c ); free_huge( &m ); free( padded_block ); return −1; } // Find next 0 byte after the padding type byte; this signifies // start-of-data i = 2; while ( padded_block[ i++ ] ); out_len += modulus_length - i; *output = realloc( *output, out_len ); memcpy( *output + ( out_len - ( modulus_length - i ) ), padded_block + i, modulus_length - i ); len -= modulus_length; input += modulus_length;

This should be easy to follow, after the description of rsa_encrypt in Listing 3-21 — the primary differences are that the input is always a multiple of modulus_length; exit with an error if this is not the case. The block-length computation is simpler. Check for padding type 2; most likely, if the decrypted padding type is not 2, this represents a decryption error (for example, you decrypted using the wrong private key). Remove the padding and copy the resultant output, one block at a time, into the output array.

NOTE The previously described padding algorithm is called PKCS1.5 padding. There are other, even more secure padding algorithms such as OAEP. For now, though, PKCS1.5 padding is just fine; the attacks that OAEP guards against are all theoretical attacks, although interesting. Additionally, TLS v1.0 mandates this padding, so there's not much point in implementing another format unless it is used outside of SSL.

Note also that, technically speaking, you should also permit CBC chaining, as well as other chaining algorithms such as OFB. However, SSL never uses RSA for more than a single block, so this won't be examined here. If you're interested, the discussion on CBC in the previous chapter should make it simple to add this feature.

Testing RSA Encryption and Decryption

Finally, develop a main routine, shown in Listing 3-25, that you can use to test this out. How to compute e, d, and n has still not been covered, so hardcode some default values that are used if nothing is passed in.

Listing 3-25: "rsa.c" test main routine

#ifdef TEST_RSA

const unsigned char TestModulus[] = {

0xC4, 0xF8, 0xE9, 0xE1, 0x5D, 0xCA, 0xDF, 0x2B,

0x96, 0xC7, 0x63, 0xD9, 0x81, 0x00, 0x6A, 0x64,

0x4F, 0xFB, 0x44, 0x15, 0x03, 0x0A, 0x16, 0xED,

0x12, 0x83, 0x88, 0x33, 0x40, 0xF2, 0xAA, 0x0E,

0x2B, 0xE2, 0xBE, 0x8F, 0xA6, 0x01, 0x50, 0xB9,

0x04, 0x69, 0x65, 0x83, 0x7C, 0x3E, 0x7D, 0x15,

0x1B, 0x7D, 0xE2, 0x37, 0xEB, 0xB9, 0x57, 0xC2, 0x06, 0x63, 0x89, 0x82, 0x50, 0x70, 0x3B, 0x3F }; const unsigned char TestPrivateKey[] = { 0x8a, 0x7e, 0x79, 0xf3, 0xfb, 0xfe, 0xa8, 0xeb, 0xfd, 0x18, 0x35, 0x1c, 0xb9, 0x97, 0x91, 0x36, 0xf7, 0x05, 0xb4, 0xd9, 0x11, 0x4a, 0x06, 0xd4, 0xaa, 0x2f, 0xd1, 0x94, 0x38, 0x16, 0x67, 0x7a, 0x53, 0x74, 0x66, 0x18, 0x46, 0xa3, 0x0c, 0x45, 0xb3, 0x0a, 0x02, 0x4b, 0x4d, 0x22, 0xb1, 0x5a, 0xb3, 0x23, 0x62, 0x2b, 0x2d, 0xe4, 0x7b, 0xa2, 0x91, 0x15, 0xf0, 0x6e, 0xe4, 0x2c, 0x41 }; const unsigned char TestPublicKey[] = { 0x01, 0x00, 0x01 }; int main( int argc, char *argv[ ] ) { int exponent_len; int modulus_len; int data_len; unsigned char *exponent; unsigned char *modulus; unsigned char *data; rsa_key public_key; rsa_key private_key; if ( argc < 3 ) { fprintf( stderr, "Usage: rsa [-e|-d] [<modulus> <exponent>] <data>\n" ); exit( 0 ); } if ( argc == 5 ) { modulus_len = hex_decode( argv[ 2 ], &modulus ); exponent_len = hex_decode( argv[ 3 ], &exponent ); data_len = hex_decode( argv[ 4 ], &data ); } else { data_len = hex_decode( argv[ 2 ], &data ); modulus_len = sizeof( TestModulus ); modulus = TestModulus; if ( !strcmp( "-e", argv[ 1 ] ) ) { exponent_len = sizeof( TestPublicKey ); exponent = TestPublicKey; }

else { exponent_len = sizeof( TestPrivateKey ); exponent = TestPrivateKey; } } public_key.modulus = ( huge * ) malloc( sizeof( huge ) ); public_key.exponent = ( huge * ) malloc( sizeof( huge ) ); private_key.modulus = ( huge * ) malloc( sizeof( huge ) ); private_key.exponent = ( huge * ) malloc( sizeof( huge ) ); if ( !strcmp( argv[ 1 ], "-e" ) ) { unsigned char *encrypted; int encrypted_len; load_huge( public_key.modulus, modulus, modulus_len ); load_huge( public_key.exponent, exponent, exponent_len ); encrypted_len = rsa_encrypt( data, data_len, &encrypted, &public_key ); show_hex( encrypted, encrypted_len ); free( encrypted ); } else if ( !strcmp( argv[ 1 ], "-d" ) ) { int decrypted_len; unsigned char *decrypted; load_huge( private_key.modulus, modulus, modulus_len ); load_huge( private_key.exponent, exponent, exponent_len ); decrypted_len = rsa_decrypt( data, data_len, &decrypted, &private_key ); show_hex( decrypted, decrypted_len ); free( decrypted ); } else { fprintf( stderr, "unrecognized option flag '%s'\n", argv[ 1 ] ); } free( data ); if ( argc == 5 ) { free( modulus ); free( exponent ); } } #endif

If called with only an input, this application defaults to the hardcoded keypair. If you run this, you see

jdavies@localhost$ rsa -e abc 40f73315d3f74703904e51e1c72686801de06a55417110e56280f1f8471a3802406d2110011e1f38 7f7b4c43258b0a1eedc558a3aac5aa2d20cf5e0d65d80db3

The output is hex encoded as before. Notice that although you only encrypted three bytes of input, you got back 64 bytes of output. The modulus is 512 bits, so the output must also be 512 bits.

You can see this decoded:

jdavies@localhost$ rsa -d \ 0x40f73315d3f74703904e51e1c7\ 2686801de06a55417110e56280f1f8471a3802406d2110011e1f387f\ 7b4c43258b0a1eedc558a3aac5aa2d20cf5e0d65d80db3 616263

The decryption routine decrypts, removes the padding, and returns the original input "616263" (the hex values of the ASCII characters a, b, and c). Note that if you try to decrypt with the public key, you get gibberish; once encrypted, the message can only be decrypted using the private key.

PROCEDURE FOR GENERATING RSA KEYPAIRS

Although code to generate RSA keypairs isn't examined here, it's not prohibitively difficult to do so. The procedure is as follows:

- Select two random prime numbers p and q.

- Compute the modulus n = pq.

- Compute the totient function ϕ(n) = (p – 1)(1 – 1)

- Select a random public exponent e < ϕ(n) (as previously mentioned, 65,537 is a popular choice).

- Perform a modular inversion (to be introduced shortly) to compute the private exponent d: de % n = 1.

You also likely noticed that your computer slowed to a crawl while decrypting; encrypting isn't too bad, because of the choice of public exponent (65,537). Decrypting is slow — not unusably slow, but also not something you want to try to do more than a few times a minute. It should come as no surprise to you that reams of research have been done into methods of speeding up the RSA decryption operation. None of them are examined here; they mostly involve keeping track of the interim steps in the original computation of the private key and taking advantage of some useful mathematical properties thereof.

So, because public-key cryptography can be used to exchange secrets, why did Chapter 2 spend so much time (besides the fact that it's interesting) looking at private-key cryptography? Well, public-key cryptography is painfully slow. There are actually ways to speed it up — the implementation presented here is slower than it could be, even with all the speed-ups employed — but it's still not realistic to apply RSA encryption to a data stream in real time. You would severely limit the network utilization if you did so. As a result, SSL actually calls on you to select a symmetric-key algorithm, generate a key, encrypt that key using an RSA public key, and, after that key has been sent and acknowledged, to begin using the symmetric algorithm for subsequent communications. The details of how precisely to do this is examined in painstaking detail in Chapter 6.

Achieving Perfect Forward Secrecy with Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange

The security in RSA rests in the difficulty of computing first the private exponent d from the public key e and the modulus n as well as the difficulty in solving the equation mx%n = c for m. This is referred to as the discrete logarithm problem. These problems are both strongly believed (but technically not proven) to be impossible to solve other than by enumerating all possible combinations. Note that although RSA can be used as a complete cryptography solution, its slow runtime limits is practical uses to simple encryption of keys to be used for symmetric cryptography. Another algorithm that relies similarly on the difficulty of factoring large prime numbers and the discrete logarithm problem is Diffie-Hellman key exchange, named after its inventors, Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman and originally described by Diffie and Hellman in the "Journal IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 22" in 1976. One significant difference between RSA and Diffie-Hellman is that although RSA can be used to encrypt arbitrary bits of data, Diffie-Hellman can only be used to perform a key exchange because neither side can predict what value both sides will ultimately agree upon, even though it's guaranteed that they'll both arrive at the same value. This ability to encrypt arbitrary data using RSA, although desirable in some contexts, is something of a double-edged sword. One potential drawback of the RSA algorithm is that, if the private key is ever compromised, any communication that was secured using that private key is now exposed. There's no such vulnerability in the Diffie-Hellman key exchange algorithm. This property — communications remaining secure even if the private key is uncovered — is referred to as perfect forward secrecy.

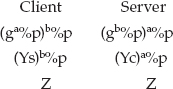

Diffie-Hellman key agreement relies on the fact that

g and p are agreed on by both sides, either offline or as part of the key exchange. They don't need to be kept secret and SSL/TLS transmits them in the clear. The server chooses a value a at random and the client chooses a value b at random. Then the server computes

The server transmits Ys to the client and the client transmits Yc to the server. At this point, they each have enough to compute the final value Z = gab%p:

And Z is the key that both sides use as the symmetric key. The server knows the value a (because it chose it), and the client knows the value b (because, again, it chose it). Neither knows the other's value, but they don't need to. Nor can an eavesdropper glean the value of Z without either a or b, neither of which has been shared. You can think of each side as computing one-half of an exponentiation and sharing that half with the other side, which then completes the exponentiation. Because the exponentiation operation is done mod p, it can't be feasibly inverted by an attacker, unless the attacker has solved the discrete logarithm problem.

Using the mod_pow function developed earlier for RSA, this is simple to implement in code as shown in Listing 3-26.

Listing 3-26: "dh.c" Diffe-Hellman key agreement

static void dh_agree( huge *p, huge *g, huge *e, huge *Y )

{

mod_pow( g, &e, p, Y );

}

static void dh_finalize( huge *p, huge *Y, huge *e, huge *Z )

{

mod_pow( Y, &e, p, &Z );

}

In fact, there's not much point in defining new functions to implement this because all they do is call mod_pow. Given p, g, and a, the server does something like

huge Ys, Yc, Z; dh_agree( p, g, a, &Ys ); send_to_client( &Ys ); receive_from_client( &Yc ); dh_finalize( p, Yc, a, Z ); // ... use "Z" as shared key

At the same time, the client does:

huge Ys, Yc, Z; dh_agree( p, g, b, &Yc );

send_to_server( &Yc ); receive_from_server( &Ys ); dh_finalize( p, &Ys, b, &Z ); // ... use "Z" as shared key

Notice also that the client doesn't need to wait for Ys before computing Yc, assuming p and g are known to both sides. In SSL, the server picks p and g, and transmits them along with Ys, but Diffie-Hellman doesn't actually require that key exchange be done this way.

One particularly interesting difference between RSA and DH is that RSA is very, very picky about what values you can use for e, d, and n. As you saw earlier, not every triple of numbers works (in fact, relative to the size of all natural numbers, very few do). However, DH key exchange works with essentially any random combination of p, g, a, and b. What guidance is there for picking out "good" values? Of course, you want to use large numbers, especially for p; other than using a large number — 512-bit, 1024-bit, and so on — you at least want to ensure that the bits are securely randomly distributed.

It also turns out that some choices of p leave the secret Z vulnerable to eavesdroppers who can employ the Pohlig-Hellman attack. The attack itself, originally published by Stephen Pollig and Martin Hellman in the journal "IEEE Transactions on Information Theory" in 1978, is mathematically technical, but it relies on a p – 1 that has no large prime factors. The math behind the attack itself is outside of the scope of this book, but guarding against it is straightforward, as long as you're aware of the risk. Ensure that the choice p – 1 is not only itself large, but that it includes at least one large prime factor. RFC 2631 recommends that p = jq + 1 where q is a large prime number and j is greater than or equal to 2. Neither q nor j needs to be kept secret; in fact, it's recommended that they be shared so that the receiver can verify that p is a good choice.

In most implementations, g is actually a very small number — 2 is a popular choice. As long as p, a, and b are very large, you can get away with such a small g and still be cryptographically secure.

Getting More Security per Key Bit: Elliptic Curve Cryptography

Although the concept and theory of elliptic curves and their application in cryptography have been around for quite a while (Miller and Koblitz described the first ECC cryptosystem in 1985), elliptic curves only managed to find their way into TLS in the past few years. TLS 1.2 introduced support for Elliptic-Curve Cryptography (ECC) in 2008. Although it hasn't, at the time of this writing, found its way into any commercial TLS implementations, it's expected that ECC will become an important element of public-key cryptography in the future. I explore the basics of ECC here — enough for you to add support for it in the chapter 9, which covers TLS 1.2 — but overall, I barely scratch the surface of the field.

ECC — elliptic-curves in general, in fact — are complex entities. An elliptic-curve is defined by the equation y2 = x3 + ax + b. a and b are typically fixed and, for public-key cryptography purposes, small numbers. The mathematics behind ECC is extraordinarily complex compared to anything you've seen so far. I won't get any deeper into it than is absolutely necessary.

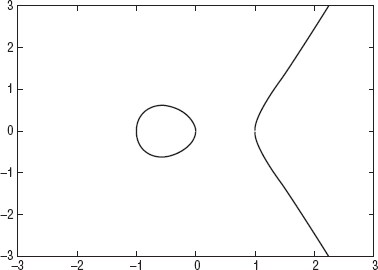

Figure 3-5 shows the graph of y2 = x3 + ax + b, the elliptic curve defined by a = –1, b = 0. Notice the discontinuity between 0 and 1;  has no solutions between 0 and 1 because x3 – ax < 0.

has no solutions between 0 and 1 because x3 – ax < 0.

Figure 3-5: Elliptic curve with a = –1, b = 0

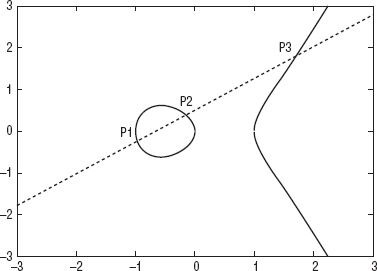

Cryptographic operations are defined in terms of multiplicative operations on this curve. It's not readily apparent how one would go about "multiplying" anything on a curve, though. Multiplication is defined in terms of addition, and "addition," in ECC, is the process of drawing a line through two points and finding it's intersection at a third point on the curve as illustrated in Figure 3-6.

Figure 3-6: Point multiplication on an elliptic curve

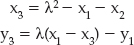

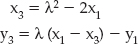

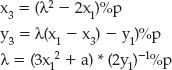

So, given two points p1 = (x1, y1), p2 = (x2, y2), "addition" of points p3 = p1 + p2 is defined as:

where

(that is, the slope of the line through p1 and p2). You may be able to spot a problem with this definition, though: How do you add a point to itself? A point all by itself has no slope —  in this case. So you need a special rule for "doubling" a point. Given p1 = (x1, y1), 2p1 is defined as:

in this case. So you need a special rule for "doubling" a point. Given p1 = (x1, y1), 2p1 is defined as:

where

Remember that a was one of the constants in the definition of the curve.

So, armed with a point addition and a point-doubling routine, you can define multiplication of a point by a scalar in terms of double and add. Recall that, for integer operations, double-and-add was a "nice" speed-up. In terms of elliptic curves, though, it's a necessity because you can't add a point to itself a given number of times. Notice also that multiplication of points is meaningless; you can add two points together, but you can only meaningfully multiply a point by a scalar value.

Whew! I warned you elliptic curves were complex. However, that's not all. As a programmer, you can likely still spot a problem with this definition: the division operation in the definition of λ. Whenever you divide integers, you get fractions, and fractions create all sorts of problems for cryptographic systems, which need absolute precision. The solution to this problem, which is probably not a surprise to you at this point, is to define everything modulo a prime number.

But — how do you divide modulo a number?

How Elliptic Curve Cryptography Relies on Modular Inversions

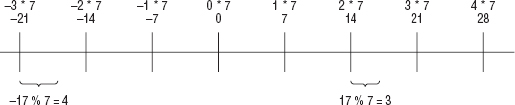

Recall that addition modulo a number n is pretty straightforward: Perform the addition normally and then compute the remainder after dividing by n. Multiplication and exponentiation are the same; just perform the operation as you normally would and compute the remainder. The distributivity of the modulus operator enables you to implement this as multiple operations each followed by modulo, but the end result is the same.

What about division modulo n? Can you divide x by y and then compute the remainder when divided by n? Consider an example. 5 × 6 = 30 and 30 % 13 = 4 (because 2 * 13 = 26 and 30 – 26 = 4). Division mod n ought to return 6 if you apply it to 5. In other words, you need an operation that, given 4, 5, and 13, returns 6. Clearly, normal division doesn't work at all: (5 × 6) % 13 = 4, but (4 / 5) % 13 = 0.8, not 6. In fact, division modulo n isn't particularly well defined.

You can't really call it division, but you do need an operation referred to as the modular inverse to complete elliptic-curve operations. This is an operation on x such that

So, going back to the example of (5 × 6) % 13 = 4, you want to discover an operation to compute a number which, when multiplied by 4 and then computed % 13 returns 6, inverting the multiplication.

Using the Euclidean Algorithm to compute Greatest Common Denominators

Such an operation exists, but it's not easily expressible; it's not nearly as simple as modulus addition or multiplication. Typically, x–1 is computed via the extended Euclidean algorithm. The normal (that is, non-extended) Euclidean algorithm is an efficient way to discover the greatest common denominator (GCD) of two numbers; the largest number that divides both evenly. The idea of the algorithm is to recursively subtract the smaller of the two numbers from the larger until one is 0. The other one is the GCD. In code, this can be implemented recursively as in Listing 3-27.

Listing 3-27: gcd (small numbers)

int gcd( int x, int y )

{

if ( x == 0 ) { return y; }

if ( y == 0 ) { return x; }

if ( x > y )

{

return gcd( x - y, y );

}

else

{

return gcd( y - x, x );

}

}

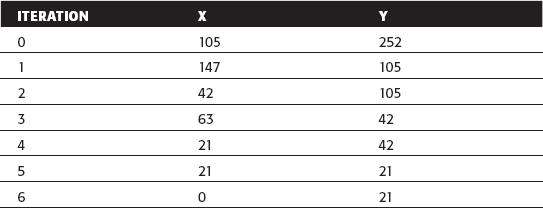

So, for example, given x = 105, y = 252:

This tells you that 21 is the largest number that evenly divides both 105 and 252 — 105/21 = 5, and 252/21 = 12. The actual values of the division operations aren't particularly important in this context. What's important is that 21 is the largest number that divides both without leaving a fractional part.

It may not be intuitively clear, but it can be proven that this will always complete. If nothing else, any two numbers always share a GCD of 1. In fact, running the GCD algorithm and verifying that the result is 1 is a way of checking that two numbers are coprime or relatively prime, in other words they share no common factors.

Computing Modular Inversions with the Extended Euclidean Algorithm

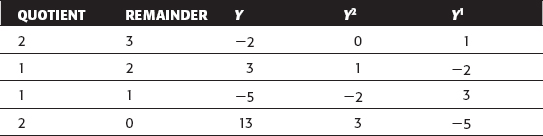

Although certainly interesting, it's not yet clear how you can use the Euclidean algorithm to compute the modular inverse of a number as defined earlier. The extended Euclidean algorithm actually runs this same process in reverse, starting from 0 up to the GCD. It also computes, in the process, two numbers y1 and y2 such that ay1 + zy2 = gcd(a,z); if z is a prime number, y1 is also the solution to a –1 a%z = 1, which is exactly what you're looking for.

The extended Euclidean algorithm for computing modular inverses is described algorithmically in FIPS-186-3, Appendix C. Listing 3-28 presents it in C code form.

Listing 3-28: "ecc_int.c" extended Euclidean algorithm (small numbers)

int ext_euclid( int z, int a )

{

int i, j, y2, y1, y, quotient, remainder;

i = a;

j = z;

y2 = 0;

y1 = 1;

while ( j > 0 )

{

quotient = i / j;

remainder = i % j;

y = y2 - ( y1 * quotient );

i = j;

j = remainder;

y2 = y1;

y1 = y;

}

return ( y2 % a );

}

Returning again to the example above of 5 and 6 % 13, remember that (5 × 6) % 13 = 4. ext_euclid tells you what number x satisfied the relationship (4x) % 13 = 6, thus inverting the multiplication by 5. In this case, z = 5 and a = 13.

Halt because remainder = 0.

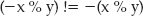

The solution, ext_euclid(5,13) = y1 % a = –5 % 13 = –5. You can check this result by verifying that (4 × –5) % 13 = –20 % 13 = 6 because 13 × –2 = –26 and – 20 – (–26) = 6.

Of course, it should come as no surprise that, to compute secure elliptic curve parameters, you are dealing with numbers far too large to fit within a single 32-bit integer, or even a 64-bit integer. Secure ECC involves inverting 1,024- or 2,048-bit numbers, which means you need to make use of the huge library again.

You may see a problem here, though. When you inverted the multiplication of 5 modulo 13, you got a negative result, and the interim computation likewise involved negative numbers, which the huge library was not equipped to handle. Unfortunately, there's just no way around it. You need negative number support in order to compute modular inverses that are needed to support ECC.

Adding Negative Number Support to the Huge Number Library

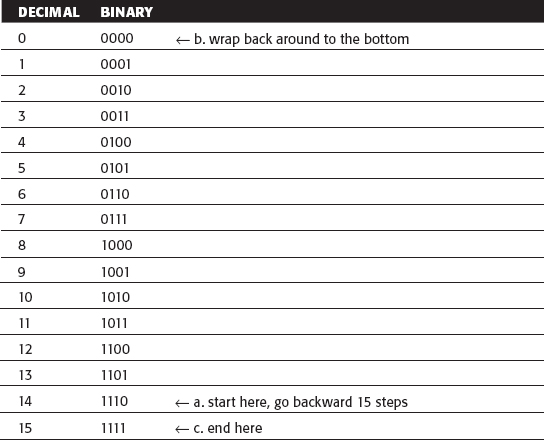

You may be familiar with two's complement binary arithmetic. In two's complement binary arithmetic, the lower half of the bit space represents positive numbers and the upper half represents negative numbers. This enables you to take advantage of the natural wrapping behavior of digital registers to efficiently perform signed operations. Given, say, a 4-bit register (to keep things small), you'd have the following:

| 0000 | 0 |

| 0001 | 1 |

| 0010 | 2 |

| 0011 | 3 |

| 0100 | 4 |

| 0101 | 5 |

| 0110 | 6 |

| 0111 | 7 |

| 1000 | –8 |

| 1001 | –7 |

| 1010 | –6 |

| 1011 | –5 |

| 1100 | –4 |

| 1101 | –3 |

| 1110 | –2 |

| 1111 | –1 |

If you subtract 3 (0011) from 1 (0001), the counters naturally wrap and end up back on 1110, which is chosen to represent –2. Multiplication preserves sign as well –2 × –3 = 0010 × 1101:

Truncate the leading three digits and you get the correct result: 1010, or –6.

This truncation creates a problem when you're trying to implement arbitrary precision binary math, though. Consider 7 × 7, which overflows this four-bit implementation:

You've computed the correct answer — 49 — but according to the rule stated earlier, you should throw away the first bit and end up with an incorrect answer of –7. You could, of course, check the magnitude of each operand, check to see if it would have overflowed, and adjust accordingly, but this is an awful lot of trouble to go to. It also negates the benefit of two's complement arithmetic. In general, two's complement arithmetic only works correctly when bit length is fixed. Instead, just keep track of signs explicitly and convert the "huge" data type to a sign/magnitude representation.

COMPUTING WITH A FIXED-PRECISION NUMERIC REPRESENTATION

As an aside, it would be possible to create, say, a fixed-precision 2,048-bit numeric representation and perform all calculations using this representation; if you do, then you can, in fact, make use of two's complement arithmetic to handle negative numbers. You can get away with this in the context of public-key cryptography because all operations are performed modulo a fixed 512-, 1024-, or 2048-bit key. Of course, in the future, you might need to expand this out to 4,096 bits and beyond. The downside of this approach is that every number, including single-byte numbers, take up 256 bytes of memory, so you trade memory for speed. I'm not aware of any arbitrary-precision math library that works this way, however; OpenSSL, GnuTLS (via GMP, via gcrypt), NSS and Java all take the "sign/magnitude" approach that's examined here.