CHAPTER 4

Authenticating Communications Using Digital Signatures

In Chapter 3, you examined public key cryptography in detail. Public key cryptography involves generating two mathematically related keys, one of which can be used to encrypt a value and the other of which can be used to decrypt a value previously encrypted with the other. One important point to note is that it technically doesn't matter which key you use to perform the encryption, as long as the other one is available to perform the decryption. The RSA algorithm defines a public key that is used to encrypt, and a private key that is used to decrypt. However, the algorithm works if you reverse the keys — if you encrypt something with the private key, it can be decrypted with — and only with — the public key.

At first glance, this doesn't sound very useful. The public key, after all, is public. It's freely shared with anybody and everybody. Therefore, if a value is encrypted with the private key, it can be decrypted by anybody and everybody as well. However, the nature of public/private keypairs is such that it's also impossible — or, to be technically precise, mathematically infeasible — for anybody except the holder of the private key to generate something that can be decrypted using the public key. After all, the encryptor must find a number c such that ce%n = m for some arbitrary m. By definition, c = md satisfies this condition and it is believed to be computationally infeasible to find another such number c.

As a result, the private key can also be used to prove identity. The holder of the private key generates a message m, and sends it to the receiver (unencrypted). Then the holder of the private key encrypts m using the private key (d,n) and sends the resulting c to the receiver. The receiver uses the public key (e,n) to "decrypt" c. If the decrypted value is exactly equal to m, the message is verified. The receiver is confident that it was truly sent by somebody with access to the private key. Note that, in this scenario, anybody can read m — it is sent in cleartext. In this case, you're just proving identity. Of course, this sort of digital signature can be easily combined with encryption. The sender could encrypt the request, sign the encrypted value, and send that on for the receiver to verify. An eavesdropper could, of course, decrypt the signature, but all he would get is the encrypted string, which he can't decrypt without the key.

There's another benefit to this approach as well. If anything changed in transit — due to a transmission error or a malicious hacker — the decrypted value won't match the signature. This guarantees not only that the holder of the private key sent it, but that what was received is exactly what was sent.

There's one problem with this approach to digital signatures, though. You've essentially doubled, at least, the length of each message. And, as you recall from the previous chapter, public key cryptography is too slow for large blocks of information. In general, you use public key operations to encode a symmetric key for subsequent cryptography operations. Obviously, you can't do this for digital signatures; you're trying to prove that somebody with access to the private key generated the message. What you need is a shortened representation of the message that can be computed by both sides. Then the sender can encrypt that using the private key, and the receiver can compute the same shortened representation, decrypt it using the public key and verify that they're identical.

Using Message Digests to Create Secure Document Surrogates

Such a shortened representation of a message is referred to as a message digest. The simplest form of a message digest is a checksum. Given a byte array of arbitrary length, add up the integer value of each byte (allowing the sum to overflow), and return the total, for example, Listing 4-1.

Listing 4-1: checksum

int checksum( char *msg )

{

int sum = 0;

int i;

for ( i = 0; i < strlen( msg ); i++ )

{

sum += msg[ i ];

}

Here, the message "abc" sums to 294 because, in ASCII, a = 97, b = 98 and c = 99; "abd" sums to 295. Because you just ignore overflow, you can compute a digest of any arbitrarily sized message.

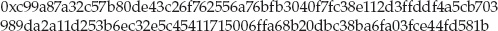

The problem with this approach is that it can be easily reversed. Consider the following scenario: I want to send a message that says, "Please transfer $100 to account 123," to my bank. My bank wants to ensure that this message came from me, so I digitally sign it. First I compute the checksum of this message: 2,970. I then use my private key to compute the signature. Using the mini-key pair e = 79, d = 1019, n = 3337 from Chapter 3, this encodes (without any padding) to 29701019 % 3337 = 2552. The bank receives the message, computes the same checksum, decodes 2552 using the public key and computes 255279 % 3337 = 2970. Because the computed checksum matches the encrypted checksum, the message can be accepted as authentic because nobody else can solve x79 % 3337 = 2970.

However, there's a problem with this simple checksum digest routine. Although an attacker who might want to submit, "Please transfer $1,000,000 to account 3789," which sums to 3171, is not able to solve x79 % 3337 = 3171, he can instead look for ways to change the message itself so that it sums to 2970. Remember that the signature itself is public, transmitted over a clear channel. If the attacker can do this, he can reuse my original signature of 2552. As it turns out, it's not hard to work backward from 2970 to engineer a collision by changing the message to "Transfer $1,000,000 to account 3789 now!" (Notice that I dropped the "please" from the beginning and inserted "now!") A bank employee might consider this rude, but the signature matches. You may have to play tricks with null terminators and backspace characters to get the messages to collide this way, but for $1,000,000, an attacker would consider it well worth the effort. Note that this would have been a vulnerability even if you had encoded the whole message rather than the output of the digest algorithm.

Therefore, for cryptographic security, you need a more secure message digest algorithm. Although it may seem that cryptography would be the hardest category of secure algorithms to get right, message digests actually are. The history of secure message digest algorithms is littered with proposals that were later found to be insecure — that is, not properly collision resistant.

Implementing the MD5 Digest Algorithm

One of the earliest secure message digest algorithms in the literature is MD2 (MD1 appears never to have been released). It was followed by MD4 (rather than MD3), which was finally followed by MD5 and is the last of the MD series of message digest algorithms. All were created by Dr. Ron Rivest, who was also one-third of the RSA team.

Understanding MD5

The goal of MD5, specified in RFC 1321, or any secure hashing algorithm, is to reduce an arbitrarily sized input into an n-bit hash in such a way that it is very unlikely that two messages, regardless of length or content, produce identical hashes — that is, collide — and that it is impossible to specifically reverse engineer such a collision. For MD5, n = 128 bits. This means that there are 2128 possible MD5 hashes. Although the input space is vastly larger than this, 2128 makes it highly unlikely that two messages will share the same MD5 hash. More importantly, it should be impossible, assuming that MD5 hashes are evenly, randomly distributed, for an attacker to compute a useful message that collides with another by way of brute force.

MD5 operates on 512-bit (64-byte) blocks of input. Each block is reduced to a 128-bit (16-byte) hash. Obviously, with such a 4:1 ratio of input blocks to output blocks, there will be at least a one in four chance of a collision. The challenge that MD5's designer faced is making it difficult or impossible to work backward to find one.

If the message to be hashed is greater than 512 bits, each 512-bit block is hashed independently and the hashes are added together, being allowed to overflow, and the result is the final sum. This obviously creates more potential for collisions.

Unlike cryptographic algorithms, though, message digests do not have to be reversible — in fact, this irreversibility is the whole point. Therefore, algorithm designers do not have to be nearly as cautious with the number and type of operations they apply to the input. The more operations, in fact, the better; this is because operations make it more difficult for an attacker to work backward from a hash to a message. MD5 applies 64 transformations to each input block. It first splits the input into 16 32-bit chunks, and the current hash into four 32-bit chunks referred to tersely as A, B, C, and D in the specification. Most of the operations are done on A, B, C, and D, which are subsequently added to the input. The 64 operations themselves consist of 16 repetitions of the four bit flipping functions F, G, H, and I as shown in Listing 4-2.

Listing 4-2: "md5.c" bit manipulation routines

unsigned int F( unsigned int x, unsigned int y, unsigned int z )

{

return ( x & y ) | ( ~x & z );

}

unsigned int G( unsigned int x, unsigned int y, unsigned int z )

{

return ( x & z ) | ( y & ~z );

}

unsigned int H( unsigned int x, unsigned int y, unsigned int z ) { return ( x ^ y ^ z ); } unsigned int I( unsigned int x, unsigned int y, unsigned int z ) { return y ^ ( x | ~z ); }

The purpose of these functions is simply to shuffle bits in an unpredictable way; don't look for any deep meaning here.

Notice that this is implemented using unsigned integers. As it turns out, MD5, unlike any of the other cryptographic algorithms in this book, operates on little-endian numbers, which makes implementation a tad easier on an Intel-based machine — although MD5 has an odd concept of "little endian" in places.

The function F is invoked 16 times — once for each input block — and then G is invoked 16 times, and then H, and then I. So, what are the inputs to F, G, H, and I? They're actually permutations of A, B, C, and D — remember that the hash was referred to as A, B, C, and D. The results of F, G, H, and I are added to A, B, C, and D along with each of the input blocks, as well as a set of constants, shifted, and added again. In all cases, adds are performed modulo 32 — that is, they're allowed to silently overflow in a 32-bit register. After all 64 operations, the final values of A, B, C, and D are concatenated together to become the hash of a 512-bit input block.

More specifically, each of the 64 transformations on A, B, C, and D involve applying one of the four functions F, G, H, or I to some permutation of A, B, C, or D, adding it to the other, adding the value of input block (i % 4), adding the value of 4294967296 * abs(sin(i)), rotating by a per-round amount, and adding the whole mess to yet one more of the A, B, C, or D hash blocks.

A Secure Hashing Example

If this is all making your head spin, it's supposed to. Secure hashing algorithms are necessarily complex. In general, they derive their security from their complexity:

- Define a ROUND macro that will be expanded 64 times, as shown in Listing 4-3.

Listing 4-3: "md5.c" ROUND macro

#define BASE_T 4294967296.0 #define ROUND( F, a, b, c, d, k, s, i ) \ a = ( a + F( b, c, d ) + x[ k ] + \

( unsigned int ) ( BASE_T * fabs( sin( ( double ) i ) ) ) ); \ a = ( a << s ) | ( a >> ( 32 - s ) ); \ a += b;

This macro takes as input the function to be performed, a, b, c and d; a value k which is an offset into the input; a value s which is an amount to rotate; and a value i which is the operation number. Notice that i is used to compute the value of 4294967296 * abs(sin(i)) on each invocation. Technically speaking, these values ought to be precomputed because they'll never change.

- Using this macro, the MD5 block operation function is straightforward, if a bit tedious, to code, as in Listing 4-4:

Listing 4-4: "md5.c" md5_block_operate function

// Size of MD5 hash in ints (128 bits) #define MD5_RESULT_SIZE 4 void md5_block_operate( const unsigned char *input, unsigned int hash[ MD5_RESULT_SIZE ] ) { unsigned int a, b, c, d; int j; unsigned int x[ 16 ]; a = hash[ 0 ]; b = hash[ 1 ]; c = hash[ 2 ]; d = hash[ 3 ]; for ( j = 0; j < 16; j++ ) { x[ j ] = input[ ( j * 4 ) + 3 ] << 24 | input[ ( j * 4 ) + 2 ] << 16 | input[ ( j * 4 ) + 1 ] << 8 | input[ ( j * 4 ) ]; } // Round 1 ROUND( F, a, b, c, d, 0, 7, 1 ); ROUND( F, d, a, b, c, 1, 12, 2 ); ROUND( F, c, d, a, b, 2, 17, 3 ); ROUND( F, b, c, d, a, 3, 22, 4 ); ROUND( F, a, b, c, d, 4, 7, 5 ); ROUND( F, d, a, b, c, 5, 12, 6 ); ROUND( F, c, d, a, b, 6, 17, 7 ); ROUND( F, b, c, d, a, 7, 22, 8 ); ROUND( F, a, b, c, d, 8, 7, 9 ); ROUND( F, d, a, b, c, 9, 12, 10 );ROUND( F, c, d, a, b, 10, 17, 11 ); ROUND( F, b, c, d, a, 11, 22, 12 ); ROUND( F, a, b, c, d, 12, 7, 13 ); ROUND( F, d, a, b, c, 13, 12, 14 ); ROUND( F, c, d, a, b, 14, 17, 15 ); ROUND( F, b, c, d, a, 15, 22, 16 ); // Round 2 ROUND( G, a, b, c, d, 1, 5, 17 ); ROUND( G, d, a, b, c, 6, 9, 18 ); ROUND( G, c, d, a, b, 11, 14, 19 ); ROUND( G, b, c, d, a, 0, 20, 20 ); ROUND( G, a, b, c, d, 5, 5, 21 ); ROUND( G, d, a, b, c, 10, 9, 22 ); ROUND( G, c, d, a, b, 15, 14, 23 ); ROUND( G, b, c, d, a, 4, 20, 24 ); ROUND( G, a, b, c, d, 9, 5, 25 ); ROUND( G, d, a, b, c, 14, 9, 26 ); ROUND( G, c, d, a, b, 3, 14, 27 ); ROUND( G, b, c, d, a, 8, 20, 28 ); ROUND( G, a, b, c, d, 13, 5, 29 ); ROUND( G, d, a, b, c, 2, 9, 30 ); ROUND( G, c, d, a, b, 7, 14, 31 ); ROUND( G, b, c, d, a, 12, 20, 32 ); // Round 3 ROUND( H, a, b, c, d, 5, 4, 33 ); ROUND( H, d, a, b, c, 8, 11, 34 ); ROUND( H, c, d, a, b, 11, 16, 35 ); ROUND( H, b, c, d, a, 14, 23, 36 ); ROUND( H, a, b, c, d, 1, 4, 37 ); ROUND( H, d, a, b, c, 4, 11, 38 ); ROUND( H, c, d, a, b, 7, 16, 39 ); ROUND( H, b, c, d, a, 10, 23, 40 ); ROUND( H, a, b, c, d, 13, 4, 41 ); ROUND( H, d, a, b, c, 0, 11, 42 ); ROUND( H, c, d, a, b, 3, 16, 43 ); ROUND( H, b, c, d, a, 6, 23, 44 ); ROUND( H, a, b, c, d, 9, 4, 45 ); ROUND( H, d, a, b, c, 12, 11, 46 ); ROUND( H, c, d, a, b, 15, 16, 47 ); ROUND( H, b, c, d, a, 2, 23, 48 ); // Round 4 ROUND( I, a, b, c, d, 0, 6, 49 ); ROUND( I, d, a, b, c, 7, 10, 50 ); ROUND( I, c, d, a, b, 14, 15, 51 ); ROUND( I, b, c, d, a, 5, 21, 52 ); ROUND( I, a, b, c, d, 12, 6, 53 ); ROUND( I, d, a, b, c, 3, 10, 54 );

ROUND( I, c, d, a, b, 10, 15, 55 ); ROUND( I, b, c, d, a, 1, 21, 56 ); ROUND( I, a, b, c, d, 8, 6, 57 ); ROUND( I, d, a, b, c, 15, 10, 58 ); ROUND( I, c, d, a, b, 6, 15, 59 ); ROUND( I, b, c, d, a, 13, 21, 60 ); ROUND( I, a, b, c, d, 4, 6, 61 ); ROUND( I, d, a, b, c, 11, 10, 62 ); ROUND( I, c, d, a, b, 2, 15, 63 ); ROUND( I, b, c, d, a, 9, 21, 64 ); hash[ 0 ] += a; hash[ 1 ] += b; hash[ 2 ] += c; hash[ 3 ] += d; }

- Create a work area to hold the a, b, c, and d values from the current hash. You see in just a minute how this is initialized — this is important. Then, split the input, which is required to be exactly 512 bits, into 16 integers. Notice that you convert to integers using little-endian conventions, rather than the big-endian conventions you've been following thus far:

for ( j = 0; j < 16; j++ ) { x[ j ] = input[ ( j * 4 ) + 3 ] << 24 | input[ ( j * 4 ) + 2 ] << 16 | input[ ( j * 4 ) + 1 ] << 8 | input[ ( j * 4 ) ]; }

Technically speaking, because you know you're compiling to a 32-bit little-endian architecture, you could actually memcpy into x — or even forgo it completely if you are willing to be fast and loose with your typecasting. The rest of the function consists of 64 expansions of the ROUND macro. You can probably see how, if you just index hash directly, rather than using the work area variables a, b, c, and d, you can change this from a macro expansion to a loop. In fact, if you want to get a bit tricky, you could follow the pattern in the k's and s's and code the whole thing in a terse loop. You can replace md5_block_operate with the shorter, but more divergent — in terms of the specification — function shown in Listing 4-5.

Listing 4-5: Alternate md5_block_operate implementation

static int s[ 4 ][ 4 ] = {

{ 7, 12, 17, 22 },

{ 5, 9, 14, 20 },

{ 4, 11, 16, 23 },

{ 6, 10, 15, 21 }

};

void md5_block_operate( const unsigned char *input, unsigned int hash[ MD5_RESULT_SIZE ] ) { int a, b, c, d, x_i, s_i; int i, j; unsigned int x[ 16 ]; unsigned int tmp_hash[ MD5_RESULT_SIZE ]; memcpy( tmp_hash, hash, MD5_RESULT_SIZE * sizeof( unsigned int ) ); for ( j = 0; j < 16; j++ ) { x[ j ] = input[ ( j * 4 ) + 3 ] << 24 | input[ ( j * 4 ) + 2 ] << 16 | input[ ( j * 4 ) + 1 ] << 8 | input[ ( j * 4 ) ]; } for ( i = 0; i < 64; i++ ) { a = 3 - ( ( i + 3 ) % 4 ); b = 3 - ( ( i + 2 ) % 4 ); c = 3 - ( ( i + 1 ) % 4 ); d = 3 - ( i % 4 ); if ( i < 16 ) { tmp_hash[ a ] += F( tmp_hash[ b ], tmp_hash[ c ], tmp_hash[ d ] ); x_i = i; } else if ( i < 32 ) { tmp_hash[ a ] += G( tmp_hash[ b ], tmp_hash[ c ], tmp_hash[ d ] ); x_i = ( 1 + ( ( i - 16 ) * 5 ) ) % 16; } else if ( i < 48 ) { tmp_hash[ a ] += H( tmp_hash[ b ], tmp_hash[ c ], tmp_hash[ d ] ); x_i = ( 5 + ( ( i - 32 ) * 3 ) ) % 16; } else { tmp_hash[ a ] += I( tmp_hash[ b ], tmp_hash[ c ], tmp_hash[ d ] ); x_i = ( ( i - 48 ) * 7 ) % 16; } s_i = s[ i / 16 ][ i % 4 ]; tmp_hash[ a ] += x[ x_i ] + ( unsigned int ) ( BASE_T * fabs( sin( ( double ) i + 1 ) ) ); tmp_hash[ a ] = ( tmp_hash[ a ] << s_i ) | ( tmp_hash[ a ] >> ( 32 - s_i ) );

tmp_hash[ a ] += tmp_hash[ b ]; } hash[ 0 ] += tmp_hash[ 0 ]; hash[ 1 ] += tmp_hash[ 1 ]; hash[ 2 ] += tmp_hash[ 2 ]; hash[ 3 ] += tmp_hash[ 3 ]; }

The longer implementation in Listing 4-5 follows the specification more closely; the shorter implementation is a bit difficult to read, but it yields the same results.

NOTE Actually, the specification includes C code! The implementation there is a bit different than this one, though. The reason is covered later.

This produces a 128-bit hash on a 512-bit block. If the input is greater than 512 bits, just call the function again, this time passing the output of the previous call as the initializer. If this is the first call, initialize the hash code to the cryptographically meaningless initializer in Listing 4-6.

Listing 4-6: "md5.c" md5 initial hash

unsigned int md5_initial_hash[ ] = {

0x67452301,

0xefcdab89,

0x98badcfe,

0x10325476

};

Notice that this initializer doesn't have any quasi-mystical cryptographic security properties; it's just the byte sequence 0123456789abcdef (in little-endian form), followed by the same thing backward. It doesn't much matter what you initialize the hash to — although 0's would be a bad choice — as long as every implementation agrees on the starting value.

Securely Hashing Multiple Blocks of Data

If you need to encrypt less than 512 bits, or a bit string that's not an even multiple of 512 bits, you pad the last block. However, you can't just pad with 0's or just with 1's. Remember, 512 0's is a legitimate input to MD5. So is one 0. You need some way to ensure that 512 0's hashes to a different value than one 0. Therefore, MD5 requires that the last eight bytes of the input be set to the length, in bits (remember that you may want to hash a value that's not an even multiple of eight bits) of the input preceding it. This means that MD5 is essentially undefined for lengths greater than 264 bits, and that if the input happens to be between 448 (512 – 64) and 512 bits, you need to add an extra 512-bit block of padding just to store the length. A sole "1" bit follows the last bit of input, followed by enough 0's to pad up to 448 bits, followed by the length of the message itself in bits.

NOTE According to the specification, if the length is greater than 264 bits, you can throw away the high-order bits of the length. This won't come up with any of the values that are hashed in this book.

Now, the MD5 specification has a strange formulation for the length. Rather than just being a little-endian 64-bit integer, it's instead stored as "low-order 32 bits" and "high-order 32 bits."

The code to process an arbitrarily sized input into an MD5 hash, including padding and iteration over multiple blocks, is shown in Listing 4-7.

Listing 4-7: "md5.c" md5 hash algorithm

#define MD5_BLOCK_SIZE 64

#define MD5_INPUT_BLOCK_SIZE 56

#define MD5_RESULT_SIZE 4

int md5_hash( const unsigned char *input,

int len,

unsigned int hash[ MD5_RESULT_SIZE ] )

{

unsigned char padded_block[ MD5_BLOCK_SIZE ];

int length_in_bits = len * 8;

// XXX should verify that len < 2^64, but since len is only 32 bits, this won't

// be a problem.

hash[ 0 ] = md5_initial_hash[ 0 ];

hash[ 1 ] = md5_initial_hash[ 1 ];

hash[ 2 ] = md5_initial_hash[ 2 ];

hash[ 3 ] = md5_initial_hash[ 3 ];

while ( len >= MD5_INPUT_BLOCK_SIZE )

{

// Special handling for blocks between 56 and 64 bytes

// (not enough room for the 8 bytes of length, but also

// not enough to fill up a block)

if ( len < MD5_BLOCK_SIZE )

{

memset( padded_block, 0, sizeof( padded_block ) );

memcpy( padded_block, input, len );

padded_block[ len ] = 0x80;

md5_block_operate( padded_block, hash );

input += len;

len = −1;

} else { md5_block_operate( input, hash ); input += MD5_BLOCK_SIZE; len -= MD5_BLOCK_SIZE; } } // There's always at least one padded block at the end, which includes // the length of the message memset( padded_block, 0, sizeof( padded_block ) ); if ( len >= 0 ) { memcpy( padded_block, input, len ); padded_block[ len ] = 0x80; } // Only append the length for the very last block // Technically, this allows for 64 bits of length, but since we can only // process 32 bits worth, we leave the upper four bytes empty // This is sort of a bizarre concept of "little endian"... padded_block[ MD5_BLOCK_SIZE - 5 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0xFF000000 ) >> 24; padded_block[ MD5_BLOCK_SIZE - 6 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x00FF0000 ) >> 16; padded_block[ MD5_BLOCK_SIZE - 7 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x0000FF00 ) >> 8; padded_block[ MD5_BLOCK_SIZE - 8 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x000000FF ); md5_block_operate( padded_block, hash ); return 0; }

NOTE Notice that this code requires that the entire input to be hashed be available when this function is called. As it turns out, you can't assume that this is always be the case. I address this shortcoming later.

Now, follow these steps:

- Initialize the hash response to the standard starting value defined earlier.

- Iterate through 512-bit blocks, calling md5_block_operate until you come to the last, or next-to-last block depending on whether the last block aligns on less than 448 bits or not.

- If the last block is between 448 and 512 bits (56 and 64 bytes), pad by adding a "1" bit, which is always hex 0x80 because this implementation never accepts non-byte-aligned input, and fill the rest of the buffer with 0's.

- The length is appended to the next block. Set len = –1 as a reminder for the next section not to append another "1" bit.

// Special handling for blocks between 56 and 64 bytes // (not enough room for the 8 bytes of length, but also // not enough to fill up a block) if ( len < MD5_BLOCK_SIZE ) { memset( padded_block, 0, sizeof( padded_block ) ); memcpy( padded_block, input, len ); padded_block[ len ] = 0x80; md5_block_operate( padded_block, hash ); input += len; len = −1; }

- Append the length, the padding bits and a trailing "1" bit — if it hasn't already been added — and operate on the final block. There will be 448 – l. These are l bits of padding, where l is the length of the input in bits. Note that this always happens, even if the input is 1 bit long.

// There's always at least one padded block at the end, which includes // the length of the message memset( padded_block, 0, sizeof( padded_block ) ); if ( len >= 0 ) { memcpy( padded_block, input, len ); padded_block[ len ] = 0x80; } // Only append the length for the very last block // Technically, this allows for 64 bits of length, but since we can only // process 32 bits worth, we leave the upper four bytes empty // This is sort of a odd concept of "little endian"... padded_block[ MD5_BLOCK_SIZE - 5 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0xFF000000 ) >> 24; padded_block[ MD5_BLOCK_SIZE - 6 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x00FF0000 ) >> 16; padded_block[ MD5_BLOCK_SIZE - 7 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x0000FF00 ) >> 8; padded_block[ MD5_BLOCK_SIZE - 8 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x000000FF ); md5_block_operate( padded_block, hash ); - Because input greater than 232 isn't allowed in this implementation, leave the last four bytes empty (0) in all cases.

And you now have a 128-bit output that is essentially unique to the input.

MD5 Vulnerabilities

If you gathered 366 people in a room, there's a 100 percent chance that two of them will share the same birthday. There are only 365 birthdays to go around, so with 366 people at least two must have the same birthday (367 if you want to count Feb. 29 and Mar. 1 as two distinct birthdays). This is clear. Here's a question for you, though: How many people would you have to gather in a room to have a 50 percent chance that two of them share the same birthday? You might hazard a guess that it would take about 183 — half the people, half the chance.

As it turns out, the answer is stunningly lower. If 23 people are gathered together in a room, there's a 50 percent chance that two of them share the same birthday. To resolve this seeming paradox, consider this: If there are n people in a room, there are 365n possible birthdays. The first person can have any of 365 birthdays; the second can have any of 365 birthdays; and so on. However, there are only 365*364 ways that two people can have unique birthdays. The first person has "used up" one of the available birthdays. Three people can only have 365*364*363 unique birthday combinations. In general, n people can have  unique combinations of birthdays. So, there are

unique combinations of birthdays. So, there are  ways that at least two people share a birthday — that is, that the birthday combinations are not unique. The math is complex, but clear: With n possibilities, you need n + 1 instances to guarantee a repeat, but you need

ways that at least two people share a birthday — that is, that the birthday combinations are not unique. The math is complex, but clear: With n possibilities, you need n + 1 instances to guarantee a repeat, but you need  to have a 50% chance of a repeat. This surprising result is often referred to as the birthday paradox.

to have a 50% chance of a repeat. This surprising result is often referred to as the birthday paradox.

This doesn't bode well for MD5. MD5 produces 128 bits for each input. 2128 is a mind-bogglingly large number. In decimal, it works out to approximately 340 million trillion trillion. However,  . That's still a lot, but quite a few less than 2128. Remember that the purpose of using MD5 rather than a simple checksum digest was that it ought to be impossible for an attacker to engineer a collision. If I deliberately go looking for a collision with a published hash, I have to compute for a long time. However, if I go looking for two documents that share a hash, I need to look for a much shorter time, albeit still for a long time. And, as you saw with DES, this brute-force birthday attack is infinitely parallelizable; the more computers I can add to the attack, the faster I can get an answer.

. That's still a lot, but quite a few less than 2128. Remember that the purpose of using MD5 rather than a simple checksum digest was that it ought to be impossible for an attacker to engineer a collision. If I deliberately go looking for a collision with a published hash, I have to compute for a long time. However, if I go looking for two documents that share a hash, I need to look for a much shorter time, albeit still for a long time. And, as you saw with DES, this brute-force birthday attack is infinitely parallelizable; the more computers I can add to the attack, the faster I can get an answer.

This vulnerability to a birthday attack is a problem that all digest algorithms have; the only solution is to make the output longer and longer until a birthday attack is infeasible in terms of computing power. As you saw with symmetric cryptography, this is a never-ending arms race as computers get faster and faster and protocol designers struggle to keep up. However, MD5 is even worse off than this. Researchers have found cracks in the protocol's fundamental design.

In 2005, security researchers Xiaoyan Wang and Hongbo Yu presented their paper "How to break MD5 and other hash functions" (http://merlot.usc.edu/csac-s06/papers/Wang05a.pdf), which detailed an exploit capable of producing targeted MD5 collisions in 15 minutes to an hour using commodity hardware. This is not a theoretical exploit; Magnus Daum and Stefaun Lucks illustrate an actual real-world MD-5 collision in their paper http://th.informatik.uni-mannheim.de/people/lucks/HashCollisions/.

In spite of this, MD5 is fairly popular; TLS mandates its use! Fortunately for the TLS-using public, it does so in a reasonably secure way — or, at least, a not terribly insecure way — so that the TLS protocol itself is not weakened by the inclusion of MD5.

Increasing Collision Resistance with the SHA-1 Digest Algorithm

Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA-1) is similar to MD5. The only principal difference is in the block operation itself. The other two superficial differences are that SHA-1 produces a 160-bit (20-byte) hash rather than a 128-bit (16-byte) hash, and SHA-1 deals with big-endian rather than little-endian numbers. Like MD5, SHA-1 operates on 512-bit blocks, and the final output is the sum (modulo 32) of the results of all of the blocks. The operation itself is slightly simpler; you start by breaking the 512-bit input into 16 4-byte values x. You then compute 80 four-byte W values from the original input where the following is rotated left once: W[0<t<16] = x[t], and W[17<7<80] = W[ t – 3 ] xor W[ t – 8 ] xor W[ t – 14 ] xor W[ t – 16 ]

This W array serves the same purpose as the 4294967296 * abs(sin(i)) computation in MD5, but is a bit easier to compute and is also based on the input.

After that, the hash is split up into five four-byte values a, b, c, d, and e, which are operated on in a series of 80 rounds, similar to the operation in MD5 — although in this case, somewhat easier to implement in a loop. At each stage, a rotation, an addition of another hash integer, an addition of an indexed constant, an addition of the W array, and an addition of a function whose operation depends on the round number is applied to the active hash value, and then the hash values are cycled so that a new one becomes the active one.

Understanding SHA-1 Block Computation

If you understood the MD5 computation in Listing 4-4, you should have no trouble making sense of the SHA-1 block computation in Listing 4-8.

Listing 4-8: "sha.c" bit manipulation, initialization and block operation

static const int k[] = {

0x5a827999, // 0 <= t <= 19

0x6ed9eba1, // 20 <= t <= 39

0x8f1bbcdc, // 40 <= t <= 59

0xca62c1d6 // 60 <= t <= 79

};

// ch is functions 0 - 19

unsigned int ch( unsigned int x, unsigned int y, unsigned int z )

{ return ( x & y ) ^ ( ~x & z ); } // parity is functions 20 - 39 & 60 - 79 unsigned int parity( unsigned int x, unsigned int y, unsigned int z ) { return x ^ y ^ z; } // maj is functions 40 - 59 unsigned int maj( unsigned int x, unsigned int y, unsigned int z ) { return ( x & y ) ^ ( x & z ) ^ ( y & z ); } #define SHA1_RESULT_SIZE 5 void sha1_block_operate( const unsigned char *block, unsigned int hash[ SHA1_RESULT_SIZE ] ) { unsigned int W[ 80 ]; unsigned int t = 0; unsigned int a, b, c, d, e, T; // First 16 blocks of W are the original 16 blocks of the input for ( t = 0; t < 80; t++ ) { if ( t < 16 ) { W[ t ] = ( block[ ( t * 4 ) ] << 24 ) | ( block[ ( t * 4 ) + 1 ] << 16 ) | ( block[ ( t * 4 ) + 2 ] << 8 ) | ( block[ ( t * 4 ) + 3 ] ); } else { W[ t ] = W[ t - 3 ] ^ W[ t - 8 ] ^ W[ t - 14 ] ^ W[ t - 16 ]; // Rotate left operation, simulated in C W[ t ] = ( W[ t ] << 1 ) | ( ( W[ t ] & 0x80000000 ) >> 31 ); } } a = hash[ 0 ]; b = hash[ 1 ]; c = hash[ 2 ]; d = hash[ 3 ]; e = hash[ 4 ];

for ( t = 0; t < 80; t++ ) { T = ( ( a << 5 ) | ( a >> 27 ) ) + e + k[ ( t / 20 ) ] + W[ t ]; if ( t <= 19 ) { T += ch( b, c, d ); } else if ( t <= 39 ) { T += parity( b, c, d ); } else if ( t <= 59 ) { T += maj( b, c, d ); } else { T += parity( b, c, d ); } e = d; d = c; c = ( ( b << 30 ) | ( b >> 2 ) ); b = a; a = T; } hash[ 0 ] += a; hash[ 1 ] += b; hash[ 2 ] += c; hash[ 3 ] += d; hash[ 4 ] += e; }

Regarding Listing 4-8:

- The constants k are defined — one for each set of 20 rounds.

- The functions ch, maj, and parity are defined: ch for rounds 0 – 19, maj for rounds 40–59, and parity for the remaining rounds. Like MD5's F, G, H, and I, these four functions just shuffle the bits of their input randomly.

- The block operation function computes the W array. Notice that you're using unsigned ints here, rather than four-byte blocks, so you have to be careful to account for endian-ness as usual. The benefit is that you only have to keep track of this transformation once, at the beginning of the computation, and from that point you can use native operations on a 32-bit architecture.

- After W has been computed, the individual five hash integers are copied into a, b, c, d, and e for computation; at each round, a new T value is computed according to

T = ( ( a << 5 ) | ( a >> 27 ) ) + e + k[ ( t / 20 ) ] + W[ t ] + ch/parity/maj(b,c,d);

- a, b, c, d, and e are then rotated through each other, just as in MD5, and, for good measure, c is rotated left 30 positions as well. Although the mechanics are slightly different, this is very similar to what was done with MD5.

You don't really have to try to make sense of the mechanics of this. It's supposed to be impossible to do so. As long as the details are correct, you can safely think of the block operation function as a true black-box function.

Understanding the SHA-1 Input Processing Function

The input processing function of SHA-1 is almost identical to that of MD5. The length is appended, in bits, at the very end of the last block, each block is 512 bits, the hash must be initialized to a standard value before input begins, and the hash computations of each block are added to one another, modulo 32, to produce the final result. The function in Listing 4-9, which computes SHA-1 hashes of a given input block, differs from md5_hash in only a few places, which are highlighted in bold.

Listing 4-9: "sha.c" SHA-1 hash algorithm

#define SHA1_INPUT_BLOCK_SIZE 56

#define SHA1_BLOCK_SIZE 64

unsigned int sha1_initial_hash[ ] = {

0x67452301,

0xefcdab89,

0x98badcfe,

0x10325476,

0xc3d2e1f0

};

int sha1_hash( unsigned char *input, int len,

unsigned int hash[ SHA1_RESULT_SIZE ] )

{

unsigned char padded_block[ SHA1_BLOCK_SIZE ];

int length_in_bits = len * 8;

hash[ 0 ] = sha1_initial_hash[ 0 ];

hash[ 1 ] = sha1_initial_hash[ 1 ];

hash[ 2 ] = sha1_initial_hash[ 2 ]; hash[ 3 ] = sha1_initial_hash[ 3 ]; hash[ 4 ] = sha1_initial_hash[ 4 ]; while ( len >= SHA1_INPUT_BLOCK_SIZE ) { if ( len < SHA1_BLOCK_SIZE ) { memset( padded_block, 0, sizeof( padded_block ) ); memcpy( padded_block, input, len ); padded_block[ len ] = 0x80; sha1_block_operate( padded_block, hash ); input += len; len = −1; } else { sha1_block_operate( input, hash ); input += SHA1_BLOCK_SIZE; len -= SHA1_BLOCK_SIZE; } } memset( padded_block, 0, sizeof( padded_block ) ); if ( len >= 0 ) { memcpy( padded_block, input, len ); padded_block[ len ] = 0x80; } padded_block[ SHA1_BLOCK_SIZE - 4 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0xFF000000 ) >> 24; padded_block[ SHA1_BLOCK_SIZE - 3 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x00FF0000 ) >> 16; padded_block[ SHA1_BLOCK_SIZE - 2 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x0000FF00 ) >> 8; padded_block[ SHA1_BLOCK_SIZE - 1 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x000000FF ); sha1_block_operate( padded_block, hash ); return 0; }

In fact, sha1_hash and md5_hash are so similar it's almost painful not to just go ahead and consolidate them into a common function. Go ahead and do so.

Because md5_block_operate and sha1_block_operate have identical method signatures (what a coincidence!), you can just pass the block_operate function in as a function pointer as in Listing 4-10.

Listing 4-10: "digest.h" digest_hash function prototype

int digest_hash( unsigned char *input, int len, unsigned int *hash, void (*block_operate)(const unsigned char *input, unsigned int hash[] ));

Because SHA1_BLOCK_SIZE and MD5_BLOCK_SIZE are actually identical, there's not much benefit in using two different constants. You could pass the block size in as a parameter to increase flexibility, but there are already quite a few parameters, and you don't need this flexibility — at least not yet. The initialization is different because SHA has one extra four-byte integer, but you can just initialize outside of the function to take care of that.

Understanding SHA-1 Finalization

The only remaining difference is the finalization. Remember that MD5 had sort of an odd formulation to append the length to the end of the block in little-endian format. SHA doesn't; it sticks with the standard big endian. You could probably code your way around this, but a better approach is to just refactor this into another function in Listing 4-11 and Listing 4-12.

Listing 4-11: "md5.c" md5_finalize

void md5_finalize( unsigned char *padded_block, int length_in_bits )

{

padded_block[ MD5_BLOCK_SIZE - 5 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0xFF000000 ) >> 24;

padded_block[ MD5_BLOCK_SIZE - 6 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x00FF0000 ) >> 16;

padded_block[ MD5_BLOCK_SIZE - 7 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x0000FF00 ) >> 8;

padded_block[ MD5_BLOCK_SIZE - 8 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x000000FF );

}

Listing 4-12: "sha.c" sha1_finalize

void sha1_finalize( unsigned char *padded_block, int length_in_bits )

{

padded_block[ SHA1_BLOCK_SIZE - 4 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0xFF000000 ) >> 24;

padded_block[ SHA1_BLOCK_SIZE - 3 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x00FF0000 ) >> 16;

padded_block[ SHA1_BLOCK_SIZE - 2 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x0000FF00 ) >> 8;

padded_block[ SHA1_BLOCK_SIZE - 1 ] = ( length_in_bits & 0x000000FF );

}

So the final "digest" function looks like Listing 4-13, with two function parameters.

/** * Generic digest hash computation. The hash should be set to its initial * value *before* calling this function. */ int digest_hash( unsigned char *input, int len, unsigned int *hash, void (*block_operate)(const unsigned char *input, unsigned int hash[] ), void (*block_finalize)(unsigned char *block, int length ) ) { unsigned char padded_block[ DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE ]; int length_in_bits = len * 8; while ( len >= INPUT_BLOCK_SIZE ) { // Special handling for blocks between 56 and 64 bytes // (not enough room for the 8 bytes of length, but also // not enough to fill up a block) if ( len < DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE ) { memset( padded_block, 0, sizeof( padded_block ) ); memcpy( padded_block, input, len ); padded_block[ len ] = 0x80; block_operate( padded_block, hash ); input += len; len = −1; } else { block_operate( input, hash ); input += DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE; len -= DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE; } } memset( padded_block, 0, sizeof( padded_block ) ); if ( len >= 0 ) { memcpy( padded_block, input, len ); padded_block[ len ] = 0x80; } block_finalize( padded_block, length_in_bits ); block_operate( padded_block, hash ); return 0; }

This single function is now responsible for computing both MD5 and SHA-1 hashes. To compute an MD5 hash, call

unsigned int hash[ 4 ]; memcpy( hash, md5_initial_hash, 4 * sizeof( unsigned int ) ); digest_hash( argv[ 2 ], strlen( argv[ 2 ] ), hash, 4, md5_block_operate, md5_finalize );

and to compute an SHA-1 hash, call

unsigned int hash[ 5 ]; memcpy( hash, sha1_initial_hash, 5 * sizeof( unsigned int ) ); digest_hash( argv[ 2 ], strlen( argv[ 2 ] ), hash, 5, sha1_block_operate, sha1_finalize );

If you were paying close attention, you may have also noticed that the first four integers of the sha1_initial_hash array are the same as the first four integers of the md5_initial_hash array. Technically you could even use one initial_hash array and share it between the two operations.

There's one final problem you run into when trying to use digest as in Listing 4-13. The output of md5 is given in big-endian format, whereas the output of SHA-1 is given in little-endian format. In and of itself, this isn't really a problem, but you want to be able to treat digest as a black box and not care which algorithm it encloses. As a result, you need to decide which format you want to follow. Arbitrarily, pick the MD5 format, and reverse the SHA-1 computations at each stage. The changes to sha.c are detailed in Listing 4-14.

Listing 4-14: "sha.c" SHA-1 in little-endian format

unsigned int sha1_initial_hash[ ] = {

0x01234567,

0x89abcdef,

0xfedcba98,

0x76543210,

0xf0e1d2c3

};

...

void sha1_block_operate( const unsigned char *block, unsigned int hash[ 5 ] )

{

...

W[ t ] = ( W[ t ] << 1 ) | ( ( W[ t ] & 0x80000000 ) >> 31 );

}

}

hash[ 0 ] = ntohl( hash[ 0 ] );

hash[ 1 ] = ntohl( hash[ 1 ] );

hash[ 2 ] = ntohl( hash[ 2 ] );

hash[ 3 ] = ntohl( hash[ 3 ] );

hash[ 4 ] = ntohl( hash[ 4 ] );

a = hash[ 0 ]; b = hash[ 1 ]; c = hash[ 2 ]; d = hash[ 3 ]; ... hash[ 3 ] += d; hash[ 4 ] += e; hash[ 0 ] = htonl( hash[ 0 ] ); hash[ 1 ] = htonl( hash[ 1 ] ); hash[ 2 ] = htonl( hash[ 2 ] ); hash[ 3 ] = htonl( hash[ 3 ] ); hash[ 4 ] = htonl( hash[ 4 ] ); }

Notice that all this does is reverse the hash values prior to each sha1_block_operate call so that you can use the native arithmetic operators to work on the block. It then re-reverses them on the way out. Of course, you also have to reverse sha1_initial_hash.

Now you can call digest and treat the hash results uniformly, whether the hash algorithm is MD5 or SHA-1. Go ahead and build a test main routine and see some results as shown in Listing 4-15.

Listing 4-15: "digest.c" main routine

#ifdef TEST_DIGEST

int main( int argc, char *argv[ ] )

{

unsigned int *hash;

int hash_len;

int i;

unsigned char *decoded_input;

int decoded_len;

if ( argc < 3 )

{

fprintf( stderr, "Usage: %s [-md5|-sha] [0x]<input>\n", argv[ 0 ] );

exit( 0 );

}

decoded_len = hex_decode( argv[ 2 ], &decoded_input );

if ( !( strcmp( argv[ 1 ], "-md5" ) ) )

{

hash = malloc( sizeof( int ) * MD5_RESULT_SIZE );

memcpy( hash, md5_initial_hash, sizeof( int ) * MD5_RESULT_SIZE );

hash_len = MD5_RESULT_SIZE;

digest_hash( decoded_input, decoded_len, hash,

md5_block_operate, md5_finalize );

}

else if ( !( strcmp( argv[ 1 ], "-sha1" ) ) ) { hash = malloc( sizeof( int ) * SHA1_RESULT_SIZE ); memcpy( hash, sha1_initial_hash, sizeof( int ) * SHA1_RESULT_SIZE ); hash_len = SHA1_RESULT_SIZE; digest_hash( decoded_input, decoded_len, hash, sha1_block_operate, sha1_finalize ); } else { fprintf( stderr, "unsupported digest algorithm '%s'\n", argv[ 1 ] ); exit( 0 ); } { unsigned char *display_hash = ( unsigned char * ) hash; for ( i = 0; i < ( hash_len * 4 ); i++ ) { printf( "%.02x", display_hash[ i ] ); } printf( "\n" ); } free( hash ); free( decoded_input ); return 0; } #endif

Compile and run this to see it in action:

jdavies@localhost$ digest -md5 abc 900150983cd24fb0d6963f7d28e17f72 jdavies@localhost$ digest -sha1 abc a9993e364706816aba3e25717850c26c9cd0d89d

Notice that the SHA-1 output is a bit longer than the MD5 output; MD5 gives you 128 bits, and SHA-1 gives you 160.

Even More Collision Resistance with the SHA-256 Digest Algorithm

Even SHA, with its 160 bits of output, is no longer considered sufficient to effectively guard against hash collisions. There have been three new standardized SHA extensions named SHA-256, SHA-384 and SHA-512. In general, the SHA-n algorithm produces n bits of output. You don't examine them all here, but go ahead and add support for SHA-256 because it's rapidly becoming the minimum required standard where secure hashing is concerned (you'll also need it later in this chapter, to support elliptic-curve cryptography). At the time of this writing, the NIST is evaluating proposals for a new SHA standard, which will almost certainly have an even longer output.

Everything about SHA-256 is identical to SHA-1 except for the block processing itself and the output length. The block size, padding, and so on are all the same. You can reuse the digest_hash function from Listing 4-13 verbatim, if you just change the block_operate function pointer.

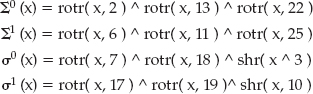

SHA-256's block operation is similar; ch and maj reappear, but the parity function disappears and four new functions, which are identified in the specification as Σ1, Σ0, σ1 and σ0are introduced:

This choice of nomenclature doesn't translate very well into code, so call S sigma_rot (because the last operation is a rotr — "rotate right") and s sigma_shr (because the last operation is a shr — "shift right"). In code, this looks like Listing 4-16.

Listing 4-16: "sha.c" SHA-256 sigma functions

unsigned int rotr( unsigned int x, unsigned int n )

{

return ( x >> n ) | ( ( x ) << ( 32 - n ) );

}

unsigned int shr( unsigned int x, unsigned int n )

{

return x >> n;

}

unsigned int sigma_rot( unsigned int x, int i )

{

return rotr( x, i ? 6 : 2 ) ^ rotr( x, i ? 11 : 13 ) ^ rotr( x, i ? 25 : 22 );

}

unsigned int sigma_shr( unsigned int x, int i )

{

return rotr( x, i ? 17 : 7 ) ^ rotr( x, i ? 19 : 18 ) ^ shr( x, i ? 10 : 3 );

}

The block operation itself should look familiar; instead of just a, b, c, d and e, you have a-h because there are eight 32-bit integers in the output now. There's a 64-int (instead of an 80-int) W that is precomputed, and a static k block. There's also a 64-iteration round that's applied to a-h where they shift positions each round and whichever input is at the head is subject to a complex computation. The code should be more or less self-explanatory; even if you can't see why this works, you should be more than convinced that the output is a random permutation of the input, which is what you want from a hash function. This is shown in Listing 4-17.

Listing 4-17: "sha.c" SHA-256 block operate

void sha256_block_operate( const unsigned char *block,

unsigned int hash[ 8 ] )

{

unsigned int W[ 64 ];

unsigned int a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h;

unsigned int T1, T2;

int t, i;

/**

* The first 32 bits of the fractional parts of the cube roots

* of the first sixty-four prime numbers.

*/

static const unsigned int k[] =

{

0x428a2f98, 0x71374491, 0xb5c0fbcf, 0xe9b5dba5, 0x3956c25b, 0x59f111f1,

0x923f82a4, 0xab1c5ed5, 0xd807aa98, 0x12835b01, 0x243185be, 0x550c7dc3,

0x72be5d74, 0x80deb1fe, 0x9bdc06a7, 0xc19bf174, 0xe49b69c1, 0xefbe4786,

0x0fc19dc6, 0x240ca1cc, 0x2de92c6f, 0x4a7484aa, 0x5cb0a9dc, 0x76f988da,

0x983e5152, 0xa831c66d, 0xb00327c8, 0xbf597fc7, 0xc6e00bf3, 0xd5a79147,

0x06ca6351, 0x14292967, 0x27b70a85, 0x2e1b2138, 0x4d2c6dfc, 0x53380d13,

0x650a7354, 0x766a0abb, 0x81c2c92e, 0x92722c85, 0xa2bfe8a1, 0xa81a664b,

0xc24b8b70, 0xc76c51a3, 0xd192e819, 0xd6990624, 0xf40e3585, 0x106aa070,

0x19a4c116, 0x1e376c08, 0x2748774c, 0x34b0bcb5, 0x391c0cb3, 0x4ed8aa4a,

0x5b9cca4f, 0x682e6ff3, 0x748f82ee, 0x78a5636f, 0x84c87814, 0x8cc70208,

0x90befffa, 0xa4506ceb, 0xbef9a3f7, 0xc67178f2

};

// deal with little-endian-ness

for ( i = 0; i < 8; i++ )

{

hash[ i ] = ntohl( hash[ i ] );

}

for ( t = 0; t < 64; t++ )

{

if ( t <= 15 )

{

W[ t ] = ( block[ ( t * 4 ) ] << 24 ) |

( block[ ( t * 4 ) + 1 ] << 16 ) |

( block[ ( t * 4 ) + 2 ] << 8 ) | ( block[ ( t * 4 ) + 3 ] ); } else { W[ t ] = sigma_shr( W[ t - 2 ], 1 ) + W[ t - 7 ] + sigma_shr( W[ t - 15 ], 0 ) + W[ t - 16 ]; } } a = hash[ 0 ]; b = hash[ 1 ]; c = hash[ 2 ]; d = hash[ 3 ]; e = hash[ 4 ]; f = hash[ 5 ]; g = hash[ 6 ]; h = hash[ 7 ]; for ( t = 0; t < 64; t++ ) { T1 = h + sigma_rot( e, 1 ) + ch( e, f, g ) + k[ t ] + W[ t ]; T2 = sigma_rot( a, 0 ) + maj( a, b, c ); h = g; g = f; f = e; e = d + T1; d = c; c = b; b = a; a = T1 + T2; } hash[ 0 ] = a + hash[ 0 ]; hash[ 1 ] = b + hash[ 1 ]; hash[ 2 ] = c + hash[ 2 ]; hash[ 3 ] = d + hash[ 3 ]; hash[ 4 ] = e + hash[ 4 ]; hash[ 5 ] = f + hash[ 5 ]; hash[ 6 ] = g + hash[ 6 ]; hash[ 7 ] = h + hash[ 7 ]; // deal with little-endian-ness for ( i = 0; i < 8; i++ ) { hash[ i ] = htonl( hash[ i ] ); } }

Notice that there are quite a few more k values for SHA-256 than for SHA-1, and that σ shows up only in the computation of W and Σ in the main loop. You also have to have an initial hash in Listing 4-18.

Listing 4-18: "sha.c" SHA-256 initial hash

static const unsigned int sha256_initial_hash[] =

{

0x67e6096a,

0x85ae67bb,

0x72f36e3c,

0x3af54fa5,

0x7f520e51,

0x8c68059b,

0xabd9831f,

0x19cde05b

};

These are presented here backward (that is, in little-endian format) with respect to the specification. If you want to invoke this, you need to call the same digest_hash function developed earlier:

unsigned int hash[ 8 ]; memcpy( hash, sha256_initial_hash, 8 * sizeof( unsigned int ) ); digest_hash( argv[ 2 ], strlen( argv[ 2 ] ), hash, 8, sha256_block_operate, sha1_finalize );

Notice that the finalize pointer points to sha1_finalize — finalization is exactly the same for SHA-256 as it is for SHA-1, so there's no reason to define a new function here.

Preventing Replay Attacks with the HMAC Keyed-Hash Algorithm

Related to message digests (and particularly relevant to SSL) are HMACs, specified in RFC 2104. To understand the motivation for HMAC, consider the secure hash functions (MD5 and SHA) examined in the previous three sections. Secure hashes are reliable, one-way functions. You give them the input, they give you the output, and nobody — not even you — can work backward from the output to uncover the input. Right?

Well, not exactly — or at least, not always. Imagine that a company maintains a database of purchase orders, and to verify that the customer is in possession of the credit card number used to place an order, a secure hash of the credit card number is stored for each order. The customer is happy, because her credit card number is not being stored in a database for some hacker to steal; and the company is happy, because it can ask a customer for her credit card number and then retrieve all orders that were made using that card for customer service purposes. The company just asks the customer for the credit card number again, hashes it, and searches the database on the hash column.

Unfortunately, there's a problem with this approach. Although there are a lot of potential hash values — even for a small hash function such as MD5 — there aren't that many credit card numbers. About 10,000 trillion. In fact, not every 16-digit number is a valid credit card number, and the LUHN consistency check that verifies the validity of a credit card number is a public algorithm. In cryptography terms, this isn't actually a very big number. A motivated attacker might try to compute the MD5 hash — or whatever hash was used — of all 10,000 trillion possible credit card numbers and store the results, keyed back to the original credit card number. This might take months to complete on a powerful cluster of computers, but after it's computed this database could be used against any database that stores an MD5 hash of credit card numbers. Fortunately, this direct attack is infeasible for a different reason. This would require 320,000 trillion bytes of memory — about 320 petabytes. The cost of this storage array far outweighs the value of even the largest database of credit card numbers.

So far, so good. An attacker would have to spend months mounting a targeted attack against the database or would have to have an astronomical amount of storage at his disposal. Unfortunately, Martin Hellman, in his paper "A Cryptanalytic Time — Memory Trade-Off", came up with a way to trade storage space for speed. His concept has been refined into what are now called rainbow tables. The idea is to start with an input, hash it, and then arbitrarily map that hash back to the input space. This arbitrary mapping doesn't undo the hash — that's impossible — it just has to be repeatable. You then take the resulting input, hash it, map it back, and so on. Do this n times, but only store the first and the last values. This way, although you have to go through every possible input value, you can drastically reduce the amount of storage you need.

When you have a hash code you want to map back to its original input, look for it in your table. If you don't find it, apply your back-mapping function, hash that, and look in the table again. Eventually, you find a match, and when you do, you have uncovered the original input. This approach has been successfully used to crack passwords whose hashes were stored rather than their actual contents; rainbow tables of common password values are available for download online; you don't even have to compute them yourself.

The easiest way to guard against this is to include a secret in the hash; without the secret, the attacker doesn't know what to hash in the first place. This is, in fact, the idea behind the HMAC. Here, both sides share a secret, which is combined with the hash in a secure way. Only a legitimate holder of the secret can figure out H(m,s) where H is the secure hash function, m is the message, and s is the secret.

A weak, naïve, shared-secret MAC operation might be:

where h refers to a secure digest. The problem with this approach is its vulnerability to known plaintext attacks. The attack works like this: The attacker convinces somebody with the MAC secret to hash and XOR the text "abc" or some other value that is known to the attacker. This has the MD5 hash 900150983cd24fb0d6963f7d28e17f72. Remember that the attacker can compute this as well — an MD5 hash never changes. The holder of the secret then XORs this value with the secret and makes the result available.

Unfortunately, the attacker can then XOR the hash with the result and recover the secret. Remember that a ⊕ b ⊕ b = a, but a ⊕ b ⊕ a = b as well. So hash ⊕ secret ⊕ hash = secret. Since mac = (hash ⊕ secret), mac ⊕ hash = secret, and the secret has been revealed.

Implementing a Secure HMAC Algorithm

A more secure algorithm is specified in RFC 2104 and is the standard for combining shared secrets with secure hash algorithms. Overall, it's not radically different in concept than XORing the shared secret with the result of a secure hash; it just adds a couple of extra functions.

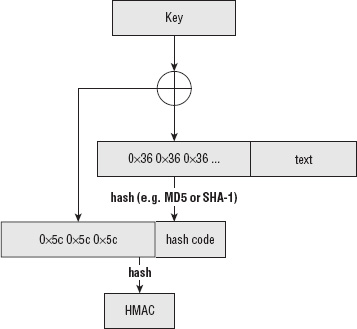

An HMAC-hash prepends one block of data to the data to be hashed. The prepended block consists of 64 bytes of 0x36, XORed with the shared secret. This means that the shared secret can't be longer than 64 bytes. If it is, it should be securely hashed itself, and the results of that hash used as the shared secret. This result (the prepended block, plus the input data itself) is then hashed, using a secure hash algorithm. Finally, this hash is appended to a new block of data that consists of one block of the byte 0x5C, XORed again with the shared secret (or its computed hash as described previously), and hashed again to produce the final hash value. Figure 4-1 illustrates this process.

This double-hash technique stops the attacker in the known-plaintext attack described earlier from computing the hash code and XORing it against the secret to recover it. All of this complexity is carefully designed to create a repeatable process. Remember, if "abc" hashes to "xyz" for me, it must hash that way for you no matter when you run it or what type of machine you're on — but in such a way that can't be reversed or forged. It seems complicated (and it is), but after it's implemented, it can be treated as a black box.

Using the digest algorithm above, you can put together an HMAC implementation that can work with any hash algorithm in Listing 4-19.

Listing 4-19: "hmac.c" HMAC function

/** * Note: key_length, text_length, hash_block_length are in bytes. * hash_code_length is in ints. */ void hmac( const unsigned char *key,

int key_length, const unsigned char *text, int text_length, void (*hash_block_operate)(const unsigned char *input, unsigned int hash[] ), void (*hash_block_finalize)(const unsigned char *block, int length ), int hash_block_length, int hash_code_length, unsigned int *hash_out ) { unsigned char *ipad, *opad, *padded_block; unsigned int *hash1; int i; // TODO if key_length > hash_block_length, should hash it using "hash_ // function" first and then use that as the key. assert( key_length < hash_block_length ); hash1 = ( unsigned int * ) malloc( hash_code_length * sizeof( unsigned int ) ); ipad = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( hash_block_length ); padded_block = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( text_length + hash_block_length ); memset( ipad, 0x36, hash_block_length ); memset( padded_block, '\0', hash_block_length ); memcpy( padded_block, key, key_length ); for ( i = 0; i < hash_block_length; i++ ) { padded_block[ i ] ^= ipad[ i ]; } memcpy( padded_block + hash_block_length, text, text_length ); memcpy( hash1, hash_out, hash_code_length * sizeof( unsigned int ) ); digest_hash( padded_block, hash_block_length + text_length, hash1, hash_code_length, hash_block_operate, hash_block_finalize ); opad = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( hash_block_length ); memset( opad, 0x5C, hash_block_length ); free( padded_block ); padded_block = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( ( hash_code_length * sizeof( int ) ) + hash_block_length ); memset( padded_block, '\0', hash_block_length ); memcpy( padded_block, key, key_length ); for ( i = 0; i < hash_block_length; i++ ) { padded_block[ i ] ^= opad[ i ];

} memcpy( padded_block + hash_block_length, hash1, hash_code_length * sizeof( int ) ); digest_hash( padded_block, hash_block_length + ( hash_code_length * sizeof( int ) ), hash_out, hash_code_length, hash_block_operate, hash_block_finalize ); free( hash1 ); free( ipad ); free( opad ); free( padded_block ); }

The method signature is a behemoth, repeated in Listing 4-20.

Listing 4-20: "hmac.h" HMAC function prototype

void hmac( const unsigned char *key,

int key_length,

const unsigned char *text,

int text_length,

int (*hash_block_operate)(const unsigned char *input, unsigned int hash[] ),

int (*hash_block_finalize)(unsigned char *block, int length ),

int hash_block_length,

int hash_code_length,

unsigned int *hash_out )

Here, key and key_length describe the shared secret; text and text_length describe the data to be HMAC-ed; hash_block_operate and hash_block_finalize describe the hash operation; hash_block_length describes the length of a block in bytes (which is always 64 for MD5 and SHA-1); hash_code_length is the length of the resultant hash in ints (4 for MD5, = for SHA-1); and hash_out is a pointer to the hash code to be generated.

Because you don't need to deal with shared secrets that are greater than 64 bytes for SSL, just ignore them:

// TODO if key_length > hash_block_length, should hash it using "hash_ // function" first and then use that as the key. assert( key_length < hash_block_length );

NOTE Note that hash_out must be initialized properly, according to the secure hashing algorithm. Alternatively, you could have added an initialization parameter, but you're already up to nine parameters here.

Remember that HMAC requires that you compute an initial hash based on the text to be hashed, prepended with a block of 0x36s XORed with the shared secret, called the key here. This section of the HMAC function builds this block of data:

hash1 = ( unsigned int * ) malloc( hash_code_length * sizeof( unsigned int ) );

ipad = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( hash_block_length );

padded_block = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( text_length 1 hash_block_length );

memset( ipad, 0x36, hash_block_length );

memset( padded_block, '\0', hash_block_length );

memcpy( padded_block, key, key_length );

for ( i = 0; i < hash_block_length; i11 )

{

padded_block[ i ] ^= ipad[ i ];

}

You allocate a new block of memory as long as the text to be hashed plus one extra block, fill it with 0x36s, and XOR that with the key. Finally, compute the hash of this new data block:

memcpy( padded_block 1 hash_block_length, text, text_length ); memcpy( hash1, hash_out, hash_code_length * sizeof( unsigned int ) ); digest_hash( padded_block, hash_block_length 1 text_length, hash1, hash_code_length, hash_block_operate, hash_block_finalize );

Notice that you're hashing into an internal block called hash1, and remember that HMAC requires you to hash that hash. There's a minor implementation problem here, though. The caller of digest_hash must preinitialize the hash code to its proper initialization value. You could ask the caller of this function to pass the correct initialization value in as a parameter, but you can "cheat" instead to save an input parameter. Because you know that the caller of hmac had to initialize hash_out, copy that value into hash1 to properly initialize it.

Completing the HMAC Operation

Now you have the first hash code computed in hash1, according to the secure hashing algorithm that was passed in. To complete the HMAC operation, you need to prepend that with another block of 0x5Cs, XORed with the shared secret, and hash it:

opad = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( hash_block_length );

memset( opad, 0x5C, hash_block_length );

free( padded_block );

padded_block = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( hash_code_length 1

( hash_block_length * sizeof( int ) ) );

memset( padded_block, '\0', hash_block_length );

memcpy( padded_block, key, key_length );

for ( i = 0; i < hash_block_length; i11 )

{

padded_block[ i ] ^= opad[ i ];

}

Notice that this frees and reallocates padded_block. You may wonder why you'd want to reallocate here because you already allocated this temporary space to compute the first hash value. However, consider the case where text_length is less than hash_code_length, which sometimes it is. In this case, you'd have too little space for the prepended hash code. You could make this a bit more efficient by allocating max( hash_code_length, text_length ) at the top of the function, but this implementation is good enough.

Finally, compute the hash into hash_out, which is the return value of the function

memcpy( padded_block 1 hash_block_length, hash1, hash_code_length * sizeof( int ) ); digest_hash( padded_block, hash_block_length 1 ( hash_code_length * sizeof( int ) ), hash_out, hash_code_length, hash_block_operate, hash_block_finalize );

Creating Updateable Hash Functions

Notice that, in order to compute an HMAC, you had to build an internal buffer consisting of a padded, XORed key followed by the text to be hashed. However, the hash functions presented here don't ever need to go back in the data stream. After block #N has been hashed, subsequent operations won't change the hash of block #N. They are just added to it, modulo 32. Therefore, you can save memory and time by allowing the hash operation to save its state and pick back up where it left off later — that is, feed it a block of data, let it update the hash code, and then feed it another, and so on.

Of course, the padding requirements of MD5 and SHA make this a little trickier than it sounds at first. You need to keep track of the running bit-length of the input so that it can be appended later on. This is, incidentally, how a 32-bit architecture can hash an input of more than 232 bits. Plus, for additional flexibility, you'd want to allow the caller to pass in less than a single block at a time and accumulate the blocks yourself.

You could store this running state in a static global, but this would cause thread-safety problems (if you ever wanted to use this routine in a threaded context, anyway). Instead, you'd do better to pass a context object into the hashing function, with a routine named something like hash_update that would also take the data to be added to the running hash, and another routine named hash_finalize that would add the final padding blocks and return the result. This is, in fact, the only non-superficial difference between the MD5 code included in RFC 1321 and the MD5 implementation presented here. You need to be able to compute running hashes for SSL, so implement this extension for MD5 and SHA. Change your digest function to allow running updates and improve the HMAC implementation a bit.

Defining a Digest Structure

Because you can no longer call digest in one shot, but must instead keep track of a long-running operation, define a context structure that stores the state of an ongoing digest computation as shown in Listing 4-21.

Listing 4-21: "digest.h" digest context structure declaration

typedef struct

{

unsigned int *hash;

int hash_len;

unsigned int input_len;

void (*block_operate)(const unsigned char *input, unsigned int hash[] );

void (*block_finalize)(const unsigned char *block, int length );

// Temporary storage

unsigned char block[ DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE ];

int block_len;

}

digest_ctx;

hash and hash_len are fairly straightforward; this is the hash code as it has been computed with the data that's been given so far. input_len is the number of bytes that have been passed in; remember input_len needs to be tracked in order to append the length in bits to the virtual buffer before computing the final hash code. Go ahead and stick the block_operate and block_finalize function pointers in here so that you don't have to further pollute your function call signatures. Finally, there's a block of temporary storage; if a call to update is made with less than a full block (or with a non-aligned bit left over), store it here, along with its length, and pass it on to block_operate when there's enough data to make a full block. This is shown in Listing 4-22.

Listing 4-22: "digest.c" update digest function

void update_digest( digest_ctx *context, const unsigned char *input, int input_len )

{

context->input_len += input_len;

// Process any left over from the last call to "update_digest"

if ( context->block_len > 0 )

{

// How much we need to make a full block

int borrow_amt = DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE - context->block_len;

if ( input_len < borrow_amt )

{

memcpy( context->block + context->block_len, input, input_len );

context->block_len += input_len;

input_len = 0;

}

else

{

memcpy( context->block + context->block_len, input, borrow_amt );

context->block_operate( context->block, context->hash );

context->block_len = 0;

input += borrow_amt;

input_len -= borrow_amt;

}

}

while ( input_len >= DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE )

{

context->block_operate( input, context->hash );

input += DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE;

input_len -= DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE;

}

// Have some non-aligned data left over; save it for next call, or

// "finalize" call.

if ( input_len > 0 ) { memcpy( context->block, input, input_len ); context->block_len = input_len; } }

This is probably the most complex function presented so far, so it's worth going through carefully:

- Update the input length. You have to append this to the very last block, whenever that may come.

context->input_len 1= input_len; // Process any left over from the last call to "update_digest" if ( context->block_len > 0 ) { ... } - Check to see if you have any data left over from a previous call. If you don't, go ahead and process the data, one block at a time, until you run out of blocks:

while ( input_len >= DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE ) { context->block_operate( input, context->hash ); input += DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE; input_len -= DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE; }This ought to look familiar; it's the main loop of the original digest function from Listing 4-13.

- Process one entire block, update the hash, increment the input pointer and decrement the length counter. At the end, input_len is either 0 or some integer less than the block size, so just store the remaining data in the context pointer until the next time update_digest is called:

if ( input_len > 0 ) { memcpy( context->block, input, input_len ); context->block_len = input_len; }At this point, you know that input_len is less than one block size, so there's no danger of overrunning the temporary buffer context->block.

- Next time update_digest is called, check to see if there's any data left over from the previous call. If so, concatenate data from the input buffer onto the end of it, process the resulting block, and process whatever remaining blocks are left.

if ( context->block_len > 0 ) { // How much we need to make a full block int borrow_amt = DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE - context->block_len; if ( input_len < borrow_amt ) { - borrow_amt is the number of bytes needed to make a full block. If you still don't have enough, just add it to the end of the temporary block and allow the function to exit.

memcpy( context->block 1 context->block_len, input, input_len ); context->block_len 1= input_len; input_len = 0; }

Otherwise, go ahead and copy borrow_amt bytes into the temporary block, process that block, and continue:

else

{

memcpy( context->block 1 context->block_len, input, borrow_amt );

context->block_operate( context->block, context->hash );

context->block_len = 0;

input 1= borrow_amt;

input_len -= borrow_amt;

}

Appending the Length to the Last Block

So, the caller calls update_digest repeatedly, as data becomes available, allowing it to compute a running hash code. However, to complete an MD5 or SHA-1 hash, you still have to append the length, in bits, to the end of the last block. The function finalize_digest handles what used to be the complex logic in digest_hash to figure out if the remaining data consists of one or two blocks — that is, if there's enough space for the end terminator and the length on the end of the remaining block as shown in Listing 4-23.

Listing 4-23: "digest.c" finalize digest

/**

* Process whatever's left over in the context buffer, append

* the length in bits, and update the hash one last time.

*/

void finalize_digest( digest_ctx *context )

{

memset( context->block + context->block_len, 0, DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE -

context->block_len ); context->block[ context->block_len ] = 0x80; // special handling if the last block is < 64 but > 56 if ( context->block_len >= INPUT_BLOCK_SIZE ) { context->block_operate( context->block, context->hash ); context->block_len = 0; memset( context->block + context->block_len, 0, DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE - context->block_len ); } // Only append the length for the very last block // Technically, this allows for 64 bits of length, but since we can only // process 32 bits worth, we leave the upper four bytes empty context->block_finalize( context->block, context->input_len * 8 ); context->block_operate( context->block, context->hash ); }

This logic was described when it was originally presented in the context of MD5.

Listing 4-24 shows how you initialize the MD5 digest context.

Listing 4-24: "md5.c" MD5 digest initialization

void new_md5_digest( digest_ctx *context )

{

context->hash_len = 4;

context->input_len = 0;

context->block_len = 0;

context->hash = ( unsigned int * )

malloc( context->hash_len * sizeof( unsigned int ) );

memcpy( context->hash, md5_initial_hash,

context->hash_len * sizeof( unsigned int ) );

memset( context->block, '\0', DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE );

context->block_operate = md5_block_operate;

context->block_finalize = md5_finalize;

}

Listing 4-25 shows how you initialize the SHA-1 context.

Listing 4-25: "sha.c" SHA-1 digest initialization

void new_sha1_digest( digest_ctx *context )

{

context->hash_len = 5;

context->input_len = 0;

context->block_len = 0;

context->hash = ( unsigned int * )

malloc( context->hash_len * sizeof( unsigned int ) );

memcpy( context->hash, sha1_initial_hash,

context->hash_len * sizeof( unsigned int ) );

memset( context->block, '\0', DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE ); context->block_operate = sha1_block_operate; context->block_finalize = sha1_finalize; }

And finally, Listing 4-26 shows how you initialize the SHA-256 context.

Listing 4-26: "sha.c" SHA-256 digest initialization

void new_sha256_digest( digest_ctx *context )

{

context->hash_len = 8;

context->input_len = 0;

context->block_len = 0;

context->hash = ( unsigned int * ) malloc( context->hash_len *

sizeof( unsigned int ) );

memcpy( context->hash, sha256_initial_hash, context->hash_len *

sizeof( unsigned int ) );

memset( context->block, '\0', DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE );

context->block_operate = sha256_block_operate;

context->block_finalize = sha1_finalize;

}

Of course if you want to support more hash contexts, just add more of them here.

After the contexts have been initialized, they're just passed to update_digest as new data becomes available, and passed to finalize_digest after all the data to be hashed has been accumulated.

Computing the MD5 Hash of an Entire File

An example might help to clarify how these updateable digest functions work. Consider a real-world example — computing the MD5 hash of an entire file:

// hash a file; buffer input

digest_ctx context;

const char *filename = "somefile.tmp";

char buf[ 400 ]; // purposely non-aligned to exercise updating logic

int bytes_read;

int f = open( filename, O_RDONLY );

if ( !f )

{

fprintf( stderr, "Unable to open '%s' for reading: ", filename );

perror( "" );

exit( 0 );

}

new_md5_digest( &context );

while ( ( bytes_read = read( f, buf, 400 ) ) > 0 ) { update_digest( &context, buf, bytes_read ); } finalize_digest( &context ); if ( bytes_read == −1 ) { fprintf( stderr, "Error reading file '%s': ", filename ); perror( "" ); } close( f ); { unsigned char *hash = ( unsigned char * ) context.hash; for ( i = 0; i < ( context.hash_len * 4 ); i11 ) { printf( "%.02x", hash[ i ] ); } printf( "\n" ); } free( context.hash );

Pay special attention to how this works:

- A new MD5 digest structure is initialized by calling new_md5_digest from Listing 4-24.

- The file is opened and read, 400 bytes at a time.

- These 400-byte blocks are passed into update_digest from Listing 4-22, which is responsible for computing the hash "so far," on top of the hash that's already been computed.

- Before completing, finalize_digest from Listing 4-23 is called to append the total length of the file as required by the digest structure and the final hash is computed.

- At this point, the context parameter can no longer be reused; if you wanted to compute another hash, you'd have to initialize another context.

The benefit of this approach is that rather than reading the whole file into memory and calling md5_hash from Listing 4-7 (which would produce the exact same result), the whole file doesn't need to be stored in memory all at once.

The hash is converted to a char array at the end so that it prints out in canonical order — remember that MD5 is little-endian; however, it's customary to display a hash value in big-endian order anyway.

NOTE This update_digest/finalize_digest/digest_ctx all but invents C++. (Don't worry, I promise it won't happen again.) In fact, if C and C++ weren't so difficult to interoperate, I'd just turn digest into a new superclass with three subclasses, md5digest, sha1digest, and sha256digest.

This new updateable hash operation simplifies HMAC a bit because you don't need to do so much copying to get the buffers set up correctly as shown in Listing 4-27.

Listing 4-27: "hmac.c" modified HMAC function to use updateable digest functions

void hmac( unsigned char *key,

int key_length,

unsigned char *text,

int text_length,

digest_ctx *digest )

{

unsigned char ipad[ DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE ];

unsigned char opad[ DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE ];

digest_ctx hash1;

int i;

// TODO if key_length > hash_block_length, should hash it using

// "hash_function" first and then use that as the key.

assert( key_length < DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE );

// "cheating"; copy the supplied digest context in here, since we don't

// know which digest algorithm is being used

memcpy( &hash1, digest, sizeof( digest_ctx ) );

hash1.hash = ( unsigned int * ) malloc(

hash1.hash_len * sizeof( unsigned int ) );

memcpy( hash1.hash, digest->hash, hash1.hash_len * sizeof( unsigned int ) );

memset( ipad, 0x36, DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE );

for ( i = 0; i < key_length; i++ )

{

ipad[ i ] ^= key[ i ];

}

update_digest( &hash1, ipad, DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE );

update_digest( &hash1, text, text_length );

finalize_digest( &hash1 );

memset( opad, 0x5C, DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE );

for ( i = 0; i < key_length; i++ )

{ opad[ i ] ^= key[ i ]; } update_digest( digest, opad, DIGEST_BLOCK_SIZE ); update_digest( digest, ( unsigned char * ) hash1.hash, hash1.hash_len * sizeof( int ) ); finalize_digest( digest ); free( hash1.hash ); }

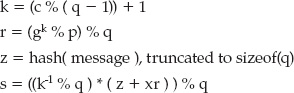

Although update_digest and finalize_digest themselves are practically impenetrable if you don't already know what they're doing, HMAC is actually much easier to read now that you've shunted memory management off to update_digest. Now you simply XOR the key with a block of 0x36s, update the digest, update it again with the text, finalize, XOR the key with another block of 0x5Cs, update another digest, update it again with the result of the first digest, and finalize that. The only real "magic" in the function is at the beginning.