CHAPTER 2

Protecting Against Eavesdroppers with Symmetric Cryptography

Encryption refers to the practice of scrambling a message such that it can only be read (descrambled) by the intended recipient. To make this possible, you must scramble the message in a reversible way, but in such a way that only somebody with a special piece of knowledge can descramble it correctly. This special piece of knowledge is referred to as the key, evoking an image of unlocking a locked drawer with its one and only key to remove the contents. Anybody who has the key can descramble — decrypt, in crypto-speak — the scrambled message. In theory, at least, no one without the key can decrypt the message.

When computers are used for cryptography, messages and keys are actually numbers. The message is converted to (or at least treated as) a number, which is numerically combined with the key (also a number) in a specified way according to a cryptographic algorithm. As such, an attacker without the key can try all keys, starting at "1" and incrementing over and over again, until the correct key is found. To determine when he's hit the right combination, the attacker has to know something about the message that was encrypted in the first place, obviously. However, this is usually the case. Consider the case of an HTTP exchange. The first four characters of the first request are likely to be "G E T." The hypothetical attacker can just do a decryption using a proposed key, check the first four letters, and if they don't match, move on to the next.

This sort of attack is called a brute force attack. To be useful and resistant to brute-force attacks, keys should be fairly large numbers, and algorithms should accept a huge range of potential keys so that an attacker has to try for a very, very long time before hitting on the right combination. There's no defense against a brute-force attack; the best you can hope for is to ensure that an attacker spends so much time performing one that the data loses its value before a brute force attack might be successful.

The application of encryption to SSL is obvious — encrypting data is effectively the point. When transmitting one's credit card number over the public Internet, it's reassuring to know that only the intended recipient can read it. When you transmit using an SSL-enabled algorithm, such as HTTPS, all traffic is encrypted prior to transmission, and must subsequently be decrypted before processing.

There are two very broad categories of cryptographic algorithms — symmetric and public. The difference between the two is in key management:

- Symmetric algorithms are the simpler of the two, at least conceptually (although the implementations are the other way around), and are examined in this chapter.

- Public algorithms, properly public key algorithms, are the topic of the next chapter.

With symmetric cryptography algorithms, the same key is used both for encryption and decryption. In some cases, the algorithm is different, with decryption "undoing" what encryption did. In other cases, the algorithm is designed so that the same set of operations, applied twice successively, cycle back to produce the same result; encryption and decryption are actually the same algorithms. In all cases, though, both the sender and the receiver must both agree what the key is before they can perform any encrypted communication. This key management turns out to be the most difficult part of encryption operations and is where public-key cryptography enters in Chapter 3. For now, just assume that this has been worked out and look at what to do with a key after you have one.

NOTE This chapter is the most technically dense chapter in this book; this is the nature of symmetric cryptography. If you're not entirely familiar with terminology such as left shift and big endian, you might want to take a quick look at Appendix A for a refresher.

Understanding Block Cipher Cryptography Algorithms

Julius Caesar is credited with perhaps the oldest known symmetric cipher algorithm. The so-called Caesar cipher — a variant of which you can probably find as a diversion in your local newspaper — assigns each letter, at random, to a number. This mapping of letters to numbers is the key in this simple algorithm. Modern cipher algorithms must be much more sophisticated than Caesar's in order to withstand automated attacks by computers. Although the basic premise remains — substituting one letter or symbol for another, and keeping track of that substitution for later — further elements of confusion and diffusion were added over the centuries to create modern cryptography algorithms. One such hardening technique is to operate on several characters at a time, rather than just one. By far the most common category of symmetric encryption algorithm is the block cipher algorithm, which operates on a fixed range of bytes rather than on a single character at a time.

In this section you examine three of the most popular block cipher algorithms — the ones that you'll most likely encounter in modern cryptographic implementations. These algorithms will likely remain relevant for several decades — changes in cryptographic standards come very slowly, and only after much analysis by cryptographers and cryptanalysts.

Implementing the Data Encryption Standard (DES) Algorithm

The Data Encryption Standard (DES) algorithm, implemented and specified by IBM at the behest of the NSA in 1974, was the first publicly available computer-ready encryption algorithm. Although for reasons you see later, DES is not considered particularly secure any more, it's still in widespread use (!) and serves as a good starting point for the study of symmetric cryptography algorithms in general. Most of the concepts that made DES work when it was first introduced appear in other cryptographic algorithms. DES is specified at the following web site: http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/fips/fips46-3/fips46-3.pdf.

DES breaks its input up into eight-byte blocks and scrambles them using an eight-byte key. This scrambling process involves a series of fixed permutations — swapping bit 34 with bit 28, bit 28 with bit 17, and so on — rotations, and XORs. The core of DES, though, and where it gets its security, is from what the standard calls S boxes where six bits of input become four bits of output in a fixed, but non-reversible (except with the key) way.

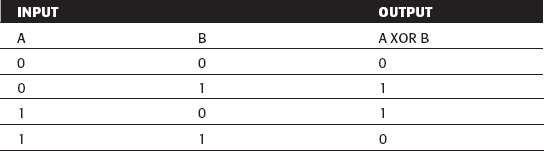

Like any modern symmetric cryptographic algorithm, DES relies heavily on the XOR operation. The logic table for XOR is shown in Table 2-1:

If any of the input bits are 1, the output is 1, unless both of the inputs bits are one. This is equivalent to addition modulo 2 and is referred to that way in the official specification. One interesting and important property of XOR for cryptography is that it's reversible. Consider:

However:

This is the same operation as the previous one, but reversed; the output is the input, but it's XORed against the same set of data. As you can see, you've recovered the original input this way. You may want to take a moment to look at the logic of the XOR operation and convince yourself that this is always the case.

To make your implementation match the specification and most public descriptions of the algorithm, you operate on byte arrays rather than taking advantage (where you can) of the wide integer types of the target hardware. DES is described using big endian conventions — that is, the most significant bit is bit 1 — whereas the Intel x86 conventions are little endian — bit 1 is the least-significant bit. To take full advantage of the hardware, you'd have to reverse quite a few parts of the specification, which you won't do here.

Instead, you operate on byte (unsigned char) arrays. Because you work at the bit level — that is, bit 39 of a 64-bit block, for example — you need a few support macros for finding and manipulating bits within such an array. The bit manipulation support macros are outlined in Listing 2-1.

Listing 2-1: "des.c" bit macros

// This does not return a 1 for a 1 bit; it just returns non-zero #define GET_BIT( array, bit ) \ ( array[ ( int ) ( bit / 8 ) ] & ( 0x80 >> ( bit % 8 ) ) ) #define SET_BIT( array, bit ) \

( array[ ( int ) ( bit / 8 ) ] |= ( 0x80 >> ( bit % 8 ) ) ) #define CLEAR_BIT( array, bit ) \ ( array[ ( int ) ( bit / 8 ) ] &= ~( 0x80 >> ( bit % 8 ) ) )

Although this is a bit dense, you should see that GET_BIT returns 0 if an array contains a 0 at a specific bit position and non-zero if an array contains a 1. The divide operator selects the byte in the array, and the shift and mod operator selects the bit within that byte. SET_BIT and CLEAR_BIT work similarly, but actually update the position. Notice that the only difference between these three macros is the operator between the array reference and the mask: & for get, |= for set, and &= ~ for clear.

Because this example XORs entire arrays of bytes, you need a support routine for that as shown in Listing 2-2.

Listing 2-2: "des.c" xor array

static void xor( unsigned char *target, const unsigned char *src, int len )

{

while ( len-- )

{

*target++ ^= *src++;

}

}

This overwrites the target array with the XOR of it and the src array.

Finally, you need a permute routine. The permute routine is responsible for putting, for instance, the 57th bit of the input into the 14th bit of the output, depending on the entries in a permute_table array. As you'll see in the code listings that follow, this function is the workhorse of the DES algorithm; it is called dozens of times, with different permute_tables each time.

Listing 2-3: "des.c" permutation

/**

* Implement the initial and final permutation functions. permute_table

* and target must have exactly len and len * 8 number of entries,

* respectively, but src can be shorter (expansion function depends on this).

* NOTE: this assumes that the permutation tables are defined as one-based

* rather than 0-based arrays, since they're given that way in the

* specification.

*/

static void permute( unsigned char target[],

const unsigned char src[],

const int permute_table[],

int len )

{

int i;

for ( i = 0; i < len * 8; i++ )

{ if ( GET_BIT( src, ( permute_table[ i ] - 1 ) ) ) { SET_BIT( target, i ); } else { CLEAR_BIT( target, i ); } } }

Now, on to the steps involved in encrypting a block of data using DES.

DES Initial Permutation

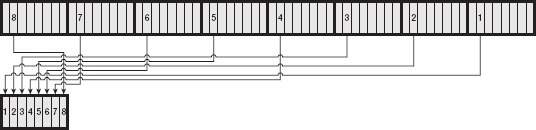

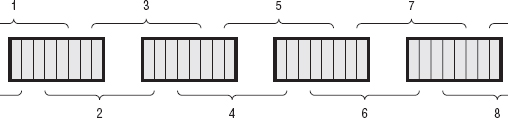

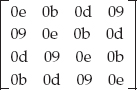

DES specifies that the input should undergo an initial permutation. The purpose of this permutation is unclear, as it serves no cryptographic purpose (the output would be just as secure without this). It may have been added for optimization for certain hardware types. Nevertheless, if you don't include it, your output will be wrong, and you won't be able to interoperate with other implementations. The specification describes this permutation in terms of the input bits and the output bits, but it works out to copying the second bit of the last byte into the first bit of the first byte of the output, followed by the second bit of the next-to-last byte into the second bit of the first byte of the output, and so on, so that the first byte of output consists of the second bits of all of the input bytes, "backward." (Remember that the input is exactly eight-bytes long, so given an 8-bit byte, taking the second bit of each input byte yields one byte of output.) The second byte of the output is the fourth bit of each of the input bytes, again backward. The third is built from the sixth bits, the fourth from the eighth bits, and the fifth comes from the first bits, and so on. So, given an 8-byte input as shown in Figure 2-1:

Figure 2-1: Unpermuted 8-byte input

The first byte of output comes from the second bits of each input byte, backward as shown in Figure 2-2.

The second byte of output comes from the fourth bits of each input byte, backward as shown in Figure 2-3.

Figure 2-2: First byte of output

Figure 2-3: Second byte of output

and so on for bytes 3 and 4; the fifth byte of output comes from the first bit of input as shown in Figure 2-4:

Figure 2-4: Five permuted bytes

and so on until all of the input bits were exhausted.

You can code this all in a very terse loop without using a lookup table on that basis, something like what's shown in Listing 2-4.

Listing 2-4: Terse initial permutation

for ( i = 1; i != 8; i = ( i + 2 ) % 9 )

{

for ( j = 7; j >= 0; j-- )

{ output[ ( i % 2 ) ? ( ( i - 1 ) >> 1 ) : ( ( 4 + ( i >> 1 ) ) ) ] |= ( ( ( input[ j ] & ( 0x80 >> i ) ) >> ( 7 - i ) ) << j ); } }

However, the specification is given in terms of permutations, so you do the same, using the permute routine. The permute_table for the initial permutation is shown in Listing 2-5.

Listing 2-5: "des.c" initial permutation table

static const int ip_table[] = {

58, 50, 42, 34, 26, 18, 10, 2,

60, 52, 44, 36, 28, 20, 12, 4,

62, 54, 46, 38, 30, 22, 14, 6,

64, 56, 48, 40, 32, 24, 16, 8,

57, 49, 41, 33, 25, 17, 9, 1,

59, 51, 43, 35, 27, 19, 11, 3,

61, 53, 45, 37, 29, 21, 13, 5,

63, 55, 47, 39, 31, 23, 15, 7 };

This specifies that the 58th bit of the input is the first bit of the output; the 50th bit of the input is the second bit of the output; and so on. You may want to convince yourself that this is the same as described above.

NOTE When examining the permutation table above, remember the structure of the GET_BIT and SET_BIT macros. The first bit, bit 58, works out to be byte #58/8 = 7, bit #58%8 = 2. Remember that DES considers bytes to be ordered according to big endian conventions, which means that bit 2 is the next-to-the-most significant bit.

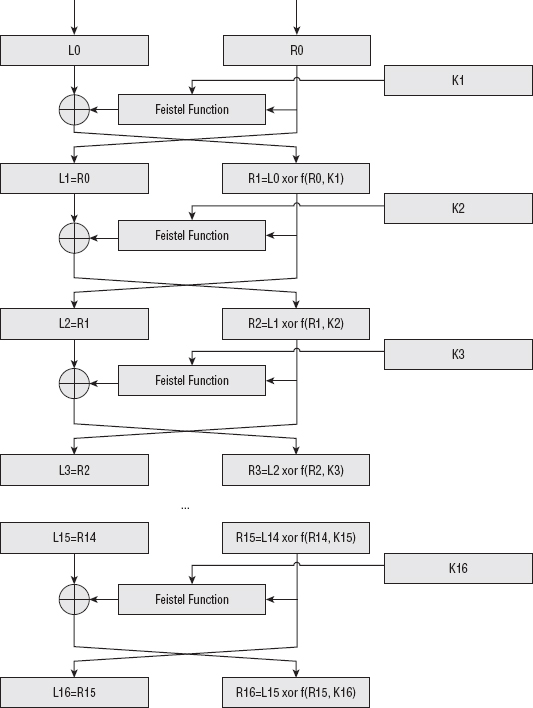

After the input has been so permuted, it is combined with the key in a series of 16 rounds, each of which consists of the following:

- Expand bits 32–64 of the input to 48 bits (described in the expansion function in Listing 2-10).

- XOR the expanded right half of the input with the key.

- Use the output of this XOR to look up eight entries in the s-box table and overwrite the input with these contents.

- Permute this output according to a specific p-table.

- XOR this output with the left half of the input (bits 1–32) and swap sides so that the XORed left half becomes the right half, and the (as of yet untouched) right-half becomes the left half. On the next round, the same series of operations are applied again, but this time on what used to be the right half.

This five step procedure is referred to as the Feistel function after its originator. Graphically, the rounds look like Figure 2-5.

Finally, the halves are swapped one last time, and the output is subject to the inverse of the initial permutation — this just undoes what the initial permutation did.

NOTE The specification suggests that you should implement this last step by just not swapping in the last round; the approach presented here is a bit simpler to implement and the result is the same.

The final permutation table is show in Listing 2-6.

Listing 2-6: "des.c" final permutation table

/**

* This just inverts ip_table.

*/

static const int fp_table[] = { 40, 8, 48, 16, 56, 24, 64, 32,

39, 7, 47, 15, 55, 23, 63, 31,

38, 6, 46, 14, 54, 22, 62, 30,

37, 5, 45, 13, 53, 21, 61, 29,

36, 4, 44, 12, 52, 20, 60, 28,

35, 3, 43, 11, 51, 19, 59, 27,

34, 2, 42, 10, 50, 18, 58, 26,

33, 1, 41, 9, 49, 17, 57, 25 };

There are several details missing from the description of the rounds. The most important of these details is what's termed the key schedule.

DES Key Schedule

In the description of step 2 of the rounds, it states "XOR the expanded right half of the input with the key." If you look at the diagram, you see that the input to this XOR is shown as K1, K2, K3, ... K15, K16. As it turns out, there are 16 different 48-bit keys, which are generated deterministically from the initial 64-bit key input.

The key undergoes an initial permutation similar to the one that the input goes through, with slight differences — this time, the first byte of the output is equal to the first bits of each input byte (again, backward); the second byte is equal to the second bit of each input byte; and so on. However, the key itself is specified as two 28-bit halves — the second half works backward through the input bytes so that the first byte of the second half is the seventh bit of each input byte; the second byte is the sixth bit; and so on. Also, because the key halves are 28 bits each, there are only three and a half bytes; the last half byte follows the pattern but stops after four bits. Finally, although the key input is 8 bytes (64 bits), the output of two 28-bit halves is only 56 bits. Eight of the key bits (the least-significant-bit of each input byte) are discarded and not used by DES.

Again, the DES specification presents this as a bit-for-bit permutation, so you will, too. This permutation table is shown in Listing 2-7.

Listing 2-7: "des.c" key permutation table 1

static const int pc1_table[] = { 57, 49, 41, 33, 25, 17, 9, 1,

58, 50, 42, 34, 26, 18, 10, 2,

59, 51, 43, 35, 27, 19, 11, 3,

60, 52, 44, 36,

63, 55, 47, 39, 31, 23, 15, 7,

62, 54, 46, 38, 30, 22, 14, 6,

61, 53, 45, 37, 29, 21, 13, 5,

28, 20, 12, 4 };

If you look carefully at this table, you see that bits 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, 56, and 64 — the LSBs of each input byte — never appear. Early DES implementations used more fault-prone hardware than you are probably used to — the LSBs of the keys were used as parity bits to ensure that the key was transmitted correctly. Strictly speaking, you should ensure that the LSB of each byte is the sum (modulo 2) of the other seven bits. Most implementers don't bother, as you can probably trust your hardware to hang on to the key you loaded into it correctly.

At each round, each of the two 28-bit halves of this 56-bit key are rotated left once or twice — once in rounds 1, 2, 9, and 16, twice otherwise. These rotated halves are then permuted (surprise) according to the second permutation table in Listing 2-8.

Listing 2-8: "des.c" key permutation table 2

static const int pc2_table[] = { 14, 17, 11, 24, 1, 5,

3, 28, 15, 6, 21, 10,

23, 19, 12, 4, 26, 8,

16, 7, 27, 20, 13, 2,

41, 52, 31, 37, 47, 55,

30, 40, 51, 45, 33, 48,

44, 49, 39, 56, 34, 53,

46, 42, 50, 36, 29, 32 };

This produces a 48-bit subkey from the 56-bit (rotated) key. Due to the rotation, this means that each round has a unique key K1, K2, K3, ..., K15, K16. These subkeys are referred to as the key schedule.

Notice that the key schedule is independent of the encryption operations and can be precomputed and stored before encryption or decryption even begins. Most DES implementations do this as a performance optimization, although this one doesn't bother.

The independent rotations of the two key-halves are shown in Listing 2-9:

Listing 2-9: "des.c" rotate left

/**

* Perform the left rotation operation on the key. This is made fairly

* complex by the fact that the key is split into two 28-bit halves, each

* of which has to be rotated independently (so the second rotation operation

* starts in the middle of byte 3).

*/

static void rol( unsigned char *target )

{

int carry_left, carry_right;

carry_left = ( target[ 0 ] & 0x80 ) >> 3;

target[ 0 ] = ( target[ 0 ] << 1 ) | ( ( target[ 1 ] & 0x80 ) >> 7 );

target[ 1 ] = ( target[ 1 ] << 1 ) | ( ( target[ 2 ] & 0x80 ) >> 7 );

target[ 2 ] = ( target[ 2 ] << 1 ) | ( ( target[ 3 ] & 0x80 ) >> 7 );

// special handling for byte 3

carry_right = ( target[ 3 ] & 0x08 ) >> 3;

target[ 3 ] = ( ( ( target[ 3 ] << 1 ) |

( ( target[ 4 ] & 0x80 ) >> 7 ) ) & ~0x10 ) | carry_left;

target[ 4 ] = ( target[ 4 ] << 1 ) | ( ( target[ 5 ] & 0x80 ) >> 7 );

target[ 5 ] = ( target[ 5 ] << 1 ) | ( ( target[ 6 ] & 0x80 ) >> 7 );

target[ 6 ] = ( target[ 6 ] << 1 ) | carry_right;

}

Here you see that each byte of the key, which is in a 7-byte array, is left-shifted by one place, and the MSB of the next byte is used as the LSB. The only complicating factor here is that the key is in a 7-byte array, but the dividing point between the two halves is in the middle of the third byte.

DES Expansion Function

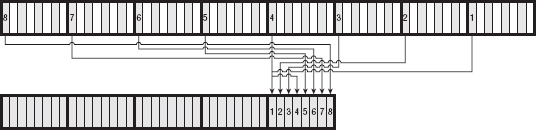

Notice in the previous section that the subkeys are 48-bits long, but the input halves that are to be XORed are 32 bits long. Now, you can't properly XOR a 32-bit input with a 48-bit key, so the input is expanded — some bits are duplicated — before being XORed. The output of the expansion function is illustrated in Figure 2-6.

The output is split into eight six-bit blocks (which works out to six eight-bit bytes), with the first and last bits of each block overlapping the preceding and following blocks. Note that the first and last block wrap around and use the last bit of the input as the first bit of output and the first bit of input as the last bit of output. Again, rather than specifying this in code, you use a permutation table as shown in Listing 2-10:

Figure 2-6: DES expansion function

Listing 2-10: "des.c" expansion table

static const int expansion_table[] = {

32, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5,

4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9,

8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13,

12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17,

16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21,

20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25,

24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29,

28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 1 };

After this has been XORed with the correct subkey for this round, it is fed into the s-box lookup. The s-boxes are what makes DES secure. It's important that the output not be a linear function of the input; if it was, a simple statistical analysis would reveal the key. An attacker knows, for example, that the letter "E" is the most common letter in the English language — if he knew that the plaintext was ASCII-encoded English, he could look for the most frequently occurring byte of output, assume that was an "E", and work backward from there (actually, in ASCII-encoded English text, the space character 32 is more common than the "E"). If he was wrong, he could find the second-most occurring character, and try again. This sort of cryptanalysis has been perfected to the point where it can be performed by a computer in seconds. Therefore, the s-boxes are not permutations, rotations or XORs but are lookups into a set of completely random tables.

Each six-bits of the input — the expanded right-half XORed with the subkey — correspond to four bits of table output. In other words, each six bits of input is used as an index into a table of four-bit outputs. In this way, the expanded, XORed right half is reduced from 48-bits to 32. The s-boxes are described in a particularly confusing way by the DES specification. Instead, I present them here as simple lookup tables in Listing 2-11. Note that each six-bit block has its own unique s-box.

Listing 2-11: "des.c" s-boxes

static const int sbox[8][64] = {

{ 14, 0, 4, 15, 13, 7, 1, 4, 2, 14, 15, 2, 11, 13, 8, 1,

3, 10, 10, 6, 6, 12, 12, 11, 5, 9, 9, 5, 0, 3, 7, 8,

4, 15, 1, 12, 14, 8, 8, 2, 13, 4, 6, 9, 2, 1, 11, 7,

15, 5, 12, 11, 9, 3, 7, 14, 3, 10, 10, 0, 5, 6, 0, 13 },

{ 15, 3, 1, 13, 8, 4, 14, 7, 6, 15, 11, 2, 3, 8, 4, 14,

9, 12, 7, 0, 2, 1, 13, 10, 12, 6, 0, 9, 5, 11, 10, 5,

0, 13, 14, 8, 7, 10, 11, 1, 10, 3, 4, 15, 13, 4, 1, 2,

5, 11, 8, 6, 12, 7, 6, 12, 9, 0, 3, 5, 2, 14, 15, 9 },

{ 10, 13, 0, 7, 9, 0, 14, 9, 6, 3, 3, 4, 15, 6, 5, 10,

1, 2, 13, 8, 12, 5, 7, 14, 11, 12, 4, 11, 2, 15, 8, 1,

13, 1, 6, 10, 4, 13, 9, 0, 8, 6, 15, 9, 3, 8, 0, 7,

11, 4, 1, 15, 2, 14, 12, 3, 5, 11, 10, 5, 14, 2, 7, 12 },

{ 7, 13, 13, 8, 14, 11, 3, 5, 0, 6, 6, 15, 9, 0, 10, 3,

1, 4, 2, 7, 8, 2, 5, 12, 11, 1, 12, 10, 4, 14, 15, 9,

10, 3, 6, 15, 9, 0, 0, 6, 12, 10, 11, 1, 7, 13, 13, 8,

15, 9, 1, 4, 3, 5, 14, 11, 5, 12, 2, 7, 8, 2, 4, 14 },

{ 2, 14, 12, 11, 4, 2, 1, 12, 7, 4, 10, 7, 11, 13, 6, 1,

8, 5, 5, 0, 3, 15, 15, 10, 13, 3, 0, 9, 14, 8, 9, 6,

4, 11, 2, 8, 1, 12, 11, 7, 10, 1, 13, 14, 7, 2, 8, 13,

15, 6, 9, 15, 12, 0, 5, 9, 6, 10, 3, 4, 0, 5, 14, 3 },

{ 12, 10, 1, 15, 10, 4, 15, 2, 9, 7, 2, 12, 6, 9, 8, 5,

0, 6, 13, 1, 3, 13, 4, 14, 14, 0, 7, 11, 5, 3, 11, 8,

9, 4, 14, 3, 15, 2, 5, 12, 2, 9, 8, 5, 12, 15, 3, 10,

7, 11, 0, 14, 4, 1, 10, 7, 1, 6, 13, 0, 11, 8, 6, 13 },

{ 4, 13, 11, 0, 2, 11, 14, 7, 15, 4, 0, 9, 8, 1, 13, 10,

3, 14, 12, 3, 9, 5, 7, 12, 5, 2, 10, 15, 6, 8, 1, 6,

1, 6, 4, 11, 11, 13, 13, 8, 12, 1, 3, 4, 7, 10, 14, 7,

10, 9, 15, 5, 6, 0, 8, 15, 0, 14, 5, 2, 9, 3, 2, 12 },

{ 13, 1, 2, 15, 8, 13, 4, 8, 6, 10, 15, 3, 11, 7, 1, 4,

10, 12, 9, 5, 3, 6, 14, 11, 5, 0, 0, 14, 12, 9, 7, 2,

7, 2, 11, 1, 4, 14, 1, 7, 9, 4, 12, 10, 14, 8, 2, 13,

0, 15, 6, 12, 10, 9, 13, 0, 15, 3, 3, 5, 5, 6, 8, 11 }

};

Also note that I have taken the liberty to reorder these, as they're given out-of-order in the specification.

After substitution, the input block undergoes a final permutation, shown in Listing 2-12.

Listing 2-12: "des.c" final input block permutation

static const int p_table[] = { 16, 7, 20, 21,

29, 12, 28, 17,

1, 15, 23, 26,

5, 18, 31, 10,

All of this is performed on the right-half of the input, which is then XORed with the left half, becoming the new right-half, and the old right-half, before any transformation, becomes the new left half.

Finally, the code to implement this is shown in Listing 2-13. This code accepts a single eight-byte block of input and an eight-byte key and returns an encrypted eight-byte output block. The input block is not modified. This is the DES algorithm itself.

Listing 2-13: "des.c" des_block_operate

#define DES_BLOCK_SIZE 8 // 64 bits, defined in the standard

#define DES_KEY_SIZE 8 // 56 bits used, but must supply 64 (8 are ignored)

#define EXPANSION_BLOCK_SIZE 6

#define PC1_KEY_SIZE 7

#define SUBKEY_SIZE 6

static void des_block_operate( const unsigned char plaintext[ DES_BLOCK_SIZE ],

unsigned char ciphertext[ DES_BLOCK_SIZE ],

const unsigned char key[ DES_KEY_SIZE ] )

{

// Holding areas; result flows from plaintext, down through these,

// finally into ciphertext. This could be made more memory efficient

// by reusing these.

unsigned char ip_block[ DES_BLOCK_SIZE ];

unsigned char expansion_block[ EXPANSION_BLOCK_SIZE ];

unsigned char substitution_block[ DES_BLOCK_SIZE / 2 ];

unsigned char pbox_target[ DES_BLOCK_SIZE / 2 ];

unsigned char recomb_box[ DES_BLOCK_SIZE / 2 ];

unsigned char pc1key[ PC1_KEY_SIZE ];

unsigned char subkey[ SUBKEY_SIZE ];

int round;

// Initial permutation

permute( ip_block, plaintext, ip_table, DES_BLOCK_SIZE );

// Key schedule computation

permute( pc1key, key, pc1_table, PC1_KEY_SIZE );

for ( round = 0; round < 16; round++ )

{

// "Feistel function" on the first half of the block in 'ip_block'

// "Expansion". This permutation only looks at the first

// four bytes (32 bits of ip_block); 16 of these are repeated

// in "expansion_table".

permute( expansion_block, ip_block + 4, expansion_table, 6 );

// "Key mixing" // rotate both halves of the initial key rol( pc1key ); if ( !( round <= 1 || round == 8 || round == 15 ) ) { // Rotate twice except in rounds 1, 2, 9 & 16 rol( pc1key ); } permute( subkey, pc1key, pc2_table, SUBKEY_SIZE ); xor( expansion_block, subkey, 6 ); // Substitution; "copy" from updated expansion block to ciphertext block memset( ( void * ) substitution_block, 0, DES_BLOCK_SIZE / 2 ); substitution_block[ 0 ] = sbox[ 0 ][ ( expansion_block[ 0 ] & 0xFC ) >> 2 ] << 4; substitution_block[ 0 ] |= sbox[ 1 ][ ( expansion_block[ 0 ] & 0x03 ) << 4 | ( expansion_block[ 1 ] & 0xF0 ) >> 4 ]; substitution_block[ 1 ] = sbox[ 2 ][ ( expansion_block[ 1 ] & 0x0F ) << 2 | ( expansion_block[ 2 ] & 0xC0 ) >> 6 ] << 4; substitution_block[ 1 ] |= sbox[ 3 ][ ( expansion_block[ 2 ] & 0x3F ) ]; substitution_block[ 2 ] = sbox[ 4 ][ ( expansion_block[ 3 ] & 0xFC ) >> 2 ] << 4; substitution_block[ 2 ] |= sbox[ 5 ][ ( expansion_block[ 3 ] & 0x03 ) << 4 | ( expansion_block[ 4 ] & 0xF0 ) >> 4 ]; substitution_block[ 3 ] = sbox[ 6 ][ ( expansion_block[ 4 ] & 0x0F ) << 2 | ( expansion_block[ 5 ] & 0xC0 ) >> 6 ] << 4; substitution_block[ 3 ] |= sbox[ 7 ][ ( expansion_block[ 5 ] & 0x3F ) ]; // Permutation permute( pbox_target, substitution_block, p_table, DES_BLOCK_SIZE / 2 ); // Recombination. XOR the pbox with left half and then switch sides. memcpy( ( void * ) recomb_box, ( void * ) ip_block, DES_BLOCK_SIZE / 2 ); memcpy( ( void * ) ip_block, ( void * ) ( ip_block + 4 ), DES_BLOCK_SIZE / 2 ); xor( recomb_box, pbox_target, DES_BLOCK_SIZE / 2 ); memcpy( ( void * ) ( ip_block + 4 ), ( void * ) recomb_box, DES_BLOCK_SIZE / 2 ); } // Swap one last time

memcpy( ( void * ) recomb_box, ( void * ) ip_block, DES_BLOCK_SIZE / 2 ); memcpy( ( void * ) ip_block, ( void * ) ( ip_block + 4 ), DES_BLOCK_SIZE / 2 ); memcpy( ( void * ) ( ip_block + 4 ), ( void * ) recomb_box, DES_BLOCK_SIZE / 2 ); // Final permutation (undo initial permutation) permute( ciphertext, ip_block, fp_table, DES_BLOCK_SIZE ); }

This code is a bit long, but if you followed the descriptions of the permutations and the Feistel function, you should be able to make sense of it.

DES Decryption

One of the nice things about the way DES was specified is that decryption is the exact same as encryption, except that the key schedule is inverted. Instead of the original key being rotated left at each round, it's rotated right. Otherwise, the routines are identical. You can easily add decryption support to des_block_operate, as illustrated in Listing 2-14.

Listing 2-14: "des.c" des_block_operate with decryption support

typedef enum { OP_ENCRYPT, OP_DECRYPT } op_type;

static void des_block_operate( const unsigned char plaintext[ DES_BLOCK_SIZE ],

unsigned char ciphertext[ DES_BLOCK_SIZE ],

const unsigned char key[ DES_KEY_SIZE ],

op_type operation )

{

...

for ( round = 0; round < 16; round++ )

{

permute( expansion_block, ip_block + 4, expansion_table, 6 );

// "Key mixing"

// rotate both halves of the initial key

if ( operation == OP_ENCRYPT )

{

rol( pc1key );

if ( !( round <= 1 || round == 8 || round == 15 ) )

{

// Rotate twice except in rounds 1, 2, 9 & 16

rol( pc1key );

}

}

permute( subkey, pc1key, pc2_table, SUBKEY_SIZE );

if ( operation == OP_DECRYPT )

{

ror( pc1key ); if ( !( round >= 14 || round == 7 || round == 0 ) ) { // Rotate twice except in rounds 1, 2, 9 & 16 ror( pc1key ); } } xor( expansion_block, subkey, 6 ); ... }

That's it. The substitution boxes and all the permutations are identical; the only difference is the rotation of the key. The ror function, in Listing 2-15, is the inverse of the rol function.

Listing 2-15: "des.c" rotate right

static void ror(unsigned char *target )

{

int carry_left, carry_right;

carry_right = ( target[ 6 ] & 0x01 ) << 3;

target[ 6 ] = ( target[ 6 ] >> 1 ) | ( ( target[ 5 ] & 0x01 ) << 7 );

target[ 5 ] = ( target[ 5 ] >> 1 ) | ( ( target[ 4 ] & 0x01 ) << 7 );

target[ 4 ] = ( target[ 4 ] >> 1 ) | ( ( target[ 3 ] & 0x01 ) << 7 );

carry_left = ( target[ 3 ] & 0x10 ) << 3;

target[ 3 ] = ( ( ( target[ 3 ] >> 1 ) |

( ( target[ 2 ] & 0x01 ) << 7 ) ) & ~0x08 ) | carry_right;

target[ 2 ] = ( target[ 2 ] >> 1 ) | ( ( target[ 1 ] & 0x01 ) << 7 );

target[ 1 ] = ( target[ 1 ] >> 1 ) | ( ( target[ 0 ] & 0x01 ) << 7 );

target[ 0 ] = ( target[ 0 ] >> 1 ) | carry_left;

}

Padding and Chaining in Block Cipher Algorithms

As shown earlier, DES operates on eight-byte input blocks. If the input is longer than eight bytes, the des_block_operate function must be called repeatedly. If the input isn't aligned on an eight-byte boundary, it has to be padded. Of course, the padding must follow a specific scheme so that the decryption routine knows what to discard after decryption. If you adopt a convention of padding with 0 bytes, the decryptor needs to have some way of determining whether the input actually ended with 0 bytes or whether these were padding bytes. National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) publication 800-38A (http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-38a/sp800-38a.pdf) recommends that a "1" bit be added to the input followed by enough zero-bits to make up eight bytes. Because you're working with byte arrays that must end on an 8-bit (one-byte) boundary, this means that, if the input block is less than eight bytes, you add the byte 0x80 (128), followed by zero bytes to pad. The decryption routine just starts at the end of the decrypted output, removing zero bytes until 0x80 is encountered, removes that, and returns the result to the caller.

Under this padding scheme, an input of, for example, "abcdef" (six characters) needs to have two bytes added to it. Therefore, "abcdef" would become

61 62 63 64 65 66 80 00 a b c d e f

This would be encrypted under DES (using, say, a key of the ASCII string password) to the hex string: 25 ac 8f c5 c4 2f 89 5d. The decryption routine would then decrypt it to a, b, c, d, e, f, 0x80, 0x00, search backward from the end for the first occurrence of 0x80, and remove everything after it. If the input string happened to actually end with hex byte 0x80, the decryptor would see 0x80 0x80 0x0 ... and still correctly remove only the padding.

There's one wrinkle here; if the input did end on an eight-byte boundary that happened to contain 0 bytes following a 0x80, the decryption routine would remove legitimate input. Therefore, if the input ends on an eight-byte boundary, you have to add a whole block of padding (0x80 0x0 0x0 0x0 0x0 0x0 0x0 0x0) so that the decryptor doesn't accidentally remove something it wasn't supposed to.

You can now implement a des_encrypt routine, as shown in Listing 2-16, that uses des_block_operate after padding its input to encrypt an arbitrarily sized block of text.

Listing 2-16: "des.c" des_operate with padding support

static void des_operate( const unsigned char *input,

int input_len,

unsigned char *output,

const unsigned char *key,

op_type operation )

{

unsigned char input_block[ DES_BLOCK_SIZE ];

assert( !( input_len % DES_BLOCK_SIZE ) );

while ( input_len )

{

memcpy( ( void * ) input_block, ( void * ) input, DES_BLOCK_SIZE );

des_block_operate( input_block, output, key, operation );

input += DES_BLOCK_SIZE;

output += DES_BLOCK_SIZE;

input_len -= DES_BLOCK_SIZE;

}

}

des_operate iterates over the input, calling des_block_operate on each eight-byte block. The caller of des_operate is responsible for padding to ensure that the input is eight-byte aligned, as shown in Listing 2-17.

Listing 2-17: "des.c" des_encrypt with NIST 800-3A padding

void des_encrypt( const unsigned char *plaintext,

const int plaintext_len,

unsigned char *ciphertext,

const unsigned char *key )

{

unsigned char *padded_plaintext;

int padding_len;

// First, pad the input to a multiple of DES_BLOCK_SIZE

padding_len = DES_BLOCK_SIZE - ( plaintext_len % DES_BLOCK_SIZE );

padded_plaintext = malloc( plaintext_len + padding_len );

// This implements NIST 800-3A padding

memset( padded_plaintext, 0x0, plaintext_len + padding_len );

padded_plaintext[ plaintext_len ] = 0x80;

memcpy( padded_plaintext, plaintext, plaintext_len );

des_operate( padded_plaintext, plaintext_len + padding_len, ciphertext,

key, OP_ENCRYPT );

free( padded_plaintext );

}

The des_encrypt variant shown in Listing 2-17 first figures out how much padding is needed — it will be between one and eight bytes. Remember, if the input is already eight-byte aligned, you must add a dummy block of eight bytes on the end so that the decryption routine doesn't remove valid data. des_encrypt then allocates enough memory to hold the padded input, copies the original input into this space, sets the first byte of padding to 0x80 and the rest to 0x0 as described earlier.

Another approach to padding, called PKCS #5 padding, is to append the number of padding bytes as the padding byte. This way, the decryptor can just look at the last byte of the output and then strip off that number of bytes from the result (with 8 being a legitimate number of bytes to strip off). Using the "abcdef" example again, the padded input now becomes

61 62 63 64 65 66 02 02 a b c d e f

Because two bytes of padding are added, the number 2 is added twice. If the input was "abcde," the padded result is instead.

des_encrypt can be changed simply to implement this padding scheme as shown in Listing 2-18.

Listing 2-18: "des.c" des_encrypt with PKCS #5 padding

// First, pad the input to a multiple of DES_BLOCK_SIZE

padding_len = DES_BLOCK_SIZE - ( plaintext_len % DES_BLOCK_SIZE );

padded_plaintext = malloc( plaintext_len + padding_len );

// This implements PKCS #5 padding.

memset( padded_plaintext, padding_len, plaintext_len + padding_len );

memcpy( padded_plaintext, plaintext, plaintext_len );

des_operate( padded_plaintext, plaintext_len + padding_len, ciphertext,

key, OP_ENCRYPT );

So, of these two options, which does SSL take? Actually, neither. SSL takes a somewhat simpler approach to padding — the number of padding bytes is output explicitly. If five bytes of padding are required, the very last byte of the decrypted output is 5. If no padding was necessary, an extra 0 byte is appended on the end.

Implementing Cipher Block Chaining

A subtler issue with this implementation of DES is that two identical blocks of text, encrypted with the same key, produce the same output. This can be useful information for an attacker who can look for repeated blocks of ciphertext to determine the characteristics of the input. Even worse, it lends itself to replay attacks. If the attacker knows, for example, that an encrypted block represents a password, or a credit card number, he doesn't need to decrypt it to use it. He can just present the same ciphertext to the authenticating server, which then dutifully decrypts it and accepts it as though it were encrypted using the original key — which, of course, it was.

The simplest way to deal with this is called cipher block chaining (CBC). After encrypting a block of data, XOR it with the results of the previous block. The first block, of course, doesn't have a previous block, so there's nothing to XOR it with. Instead, the encryption routine should create a random eight-byte initialization vector (sometimes also referred to as salt) and XOR the first block with that. This initialization vector doesn't necessarily have to be strongly protected or strongly randomly generated. It just has to be different every time so that encrypting a certain string with a certain password produces different output every time.

Incidentally, you may come across the term ECB or Electronic Code Book chaining, which actually refers to encryption with no chaining (that is, the encryption routine developed in the previous section) and mostly serves to distinguish non-CBC from CBC. There are other chaining methods as well, such as OFB (output feedback), which I discuss later.

You can add support for initialization vectors into des_operate easily as shown in Listing 2-19.

Listing 2-19: "des.c" des_operate with CBC support and padding removed from des_encrypt

static void des_operate( const unsigned char *input,

int input_len,

unsigned char *output,

const unsigned char *iv,

const unsigned char *key,

op_type operation )

{

unsigned char input_block[ DES_BLOCK_SIZE ];

assert( !( input_len % DES_BLOCK_SIZE ) );

while ( input_len )

{

memcpy( ( void * ) input_block, ( void * ) input, DES_BLOCK_SIZE );

xor( input_block, iv, DES_BLOCK_SIZE ); // implement CBC

des_block_operate( input_block, output, key, operation );

memcpy( ( void * ) iv, ( void * ) output, DES_BLOCK_SIZE ); // CBC

input += DES_BLOCK_SIZE;

output += DES_BLOCK_SIZE;

input_len -= DES_BLOCK_SIZE;

}

}

...

void des_encrypt( const unsigned char *plaintext,

const int plaintext_len,

unsigned char *ciphertext,

const unsigned char *iv,

const unsigned char *key )

{

des_operate( plaintext, plaintext_len, ciphertext,

iv, key, OP_ENCRYPT );

}

As you can see, this isn't particularly complex. You just pass in a DES_BLOCK_SIZE byte array, XOR it with the first block — before encrypting it — and then keep track of the output on each iteration so that it can be XORed, before encryption, with each subsequent block.

Notice also that, with each operation, you overwrite the contents of the iv array. This means that the caller can invoke des_operate again, pointing to the same iv memory location, and encrypt streamed data.

At decryption time, then, you first decrypt a block, and then XOR that with the encrypted previous block.

But what about the first block? The initialization vector must be remembered and transmitted (or agreed upon) before decryption can continue. To support CBC in decryption, you have to change the order of things just a bit as shown in Listing 2-20.

Listing 2-20: "des.c" des_operate with CBC for encrypt or decrypt

while ( input_len )

{

memcpy( ( void * ) input_block, ( void * ) input, DES_BLOCK_SIZE );

if ( operation == OP_ENCRYPT )

{

xor( input_block, iv, DES_BLOCK_SIZE ); // implement CBC

des_block_operate( input_block, output, key, operation );

memcpy( ( void * ) iv, ( void * ) output, DES_BLOCK_SIZE ); // CBC

}

if ( operation == OP_DECRYPT )

{

des_block_operate( input_block, output, key, operation );

xor( output, iv, DES_BLOCK_SIZE );

memcpy( ( void * ) iv, ( void * ) input, DES_BLOCK_SIZE ); // CBC

}

input += DES_BLOCK_SIZE;

output += DES_BLOCK_SIZE;

input_len -= DES_BLOCK_SIZE;

}

And finally, the decrypt routine that passes in the initialization vector and removes the padding that was inserted, using the PKCS #5 padding scheme, is shown in Listing 2-21.

Listing 2-21: "des.c" des_decrypt

void des_decrypt( const unsigned char *ciphertext,

const int ciphertext_len,

unsigned char *plaintext,

const unsigned char *iv,

const unsigned char *key )

{

des_operate( ciphertext, ciphertext_len, plaintext, iv, key, OP_DECRYPT );

// Remove any padding on the end of the input

//plaintext[ ciphertext_len - plaintext[ ciphertext_len - 1 ] ] = 0x0;

}

The commented-out line at the end of Listing 2-21 illustrates how you might remove padding. As you can see, removing the padding is simple; just read the contents of the last byte of the decrypted output, which contains the number of padding bytes that were appended. Then replace the byte at that position, from the end with a null terminator, effectively discarding the padding. You don't want this in a general-purpose decryption routine, though, because it doesn't deal properly with binary input and because, in SSL, the caller is responsible for ensuring that the input is block-aligned.

To see this in action, you can add a main routine to your des.c file so that you can do DES encryption and decryption operations from the command line. To enable compilation of this as a test app as well as an included object in another app — which you do when you add this to your SSL library — wrap up the main routine in an #ifdef as shown in Listing 2-22.

Listing 2-22: "des.c" command-line test routine

#ifdef TEST_DES

int main( int argc, char *argv[ ] )

{

unsigned char *key;

unsigned char *iv;

unsigned char *input;

unsigned char *output;

int out_len, input_len;

if ( argc < 4 )

{

fprintf( stderr, "Usage: %s <key> <iv> <input>\n", argv[ 0 ] );

exit( 0 );

}

key = argv[ 1 ];

iv = argv[ 2 ];

input = argv[ 3 ];

out_len = input_len = strlen( input );

output = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( out_len + 1 );

des_encrypt( input, input_len, output, iv, key );

while ( out_len-- )

{

printf( "%.02x", *output++ );

}

printf( "\n" );

return 0;

}

#endif

Notice that the input must be an even multiple of eight. If you give it bad data, the program just crashes unpredictably. The output is displayed in hexadecimal because it's almost definitely not going to be printable ASCII. Alternatively, you could have Base64-encoded this, but using hex output leaves it looking the same as the network traces presented later. You have to provide a -DTEST_DES flag to the compiler when building this:

gcc -DTEST_DES -g -o des des.c

After this has been compiled, you can invoke it via

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./des password initialz abcdefgh 71828547387b18e5

Just make sure that the input is block-aligned. The key and the initialization vector must be eight bytes, and the input must be a multiple of eight bytes.

What about decryption? You likely want to see this decrypted, but the output isn't in printable-ASCII form and you have no way to pass this in as a command-line parameter. Expand the input to allow the caller to pass in hex-coded values instead of just printable-ASCII values. You can implement this just like C does; if the user starts an argument with "0x," the remainder is assumed to be a hex-coded byte array. Because this hex-parsing routine is useful again later, put it into its own utility file, shown in Listing 2-23.

Listing 2-23: "hex.c" hex_decode

/**

* Check to see if the input starts with "0x"; if it does, return the decoded

* bytes of the following data (presumed to be hex coded). If not, just return

* the contents. This routine allocates memory, so has to be free'd.

*/

int hex_decode( const unsigned char *input, unsigned char **decoded )

{

int i;

int len;

if ( strncmp( "0x", input, 2 ) )

{

len = strlen( input ) + 1;

*decoded = malloc( len );

strcpy( *decoded, input );

len--;

}

else

{

len = ( strlen( input ) >> 1 ) - 1;

*decoded = malloc( len );

for ( i = 2; i < strlen( input ); i += 2 )

{

(*decoded)[ ( ( i / 2 ) - 1 ) ] =

( ( ( input[ i ] <= '9' ) ? input[ i ] - '0' :

( ( tolower( input[ i ] ) ) - 'a' + 10 ) ) << 4 ) |

( ( input[ i + 1 ] <= '9' ) ? input[ i + 1 ] - '0' :

Whether the input starts with "0x" or not, the decoded pointer is initialized and filled with either the unchanged input or the byte value of the hex-decoded input — minus, of course, the "0x" leader. While you're at it, go ahead and move the simple hex_display routine that was at the end of des.c's main routine into a reusable utility function as shown in Listing 2-24.

Listing 2-24: "hex.c" show_hex

void show_hex( const unsigned char *array, int length )

{

while ( length-- )

{

printf( "%.02x", *array++ );

}

printf( "\n" );

}

Now, des.c's main function becomes what's shown in Listing 2-25.

Listing 2-25: "des.c" main routine with decryption support

int main( int argc, char *argv[ ] )

{

unsigned char *key;

unsigned char *iv;

unsigned char *input;

int key_len;

int input_len;

int out_len;

int iv_len;

unsigned char *output;

if ( argc < 4 )

{

fprintf( stderr, "Usage: %s [-e|-d] <key> <iv> <input>\n", argv[ 0 ] );

exit( 0 );

}

key_len = hex_decode( argv[ 2 ], &key );

iv_len = hex_decode( argv[ 3 ], &iv );

input_len = hex_decode( argv[ 4 ], &input );

out_len = input_len;

output = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( out_len + 1 ); if ( !( strcmp( argv[ 1 ], "-e" ) ) ) { des_encrypt( input, input_len, output, iv, key ); show_hex( output, out_len ); } else if ( !( strcmp( argv[ 1 ], "-d" ) ) ) { des_decrypt( input, input_len, output, iv, key ); show_hex( output, out_len ); } else { fprintf( stderr, "Usage: %s [-e|-d] <key> <iv> <input>\n", argv[ 0 ] ); } free( input ); free( iv ); free( key ); free( output ); return 0; }

Now you can decrypt the example:

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./des -d password initialz \ 0x71828547387b18e5 6162636465666768

Notice that the output here is hex-coded; 6162636465666768 is the ASCII representation of abcdefgh. The key and initialization vector were also changed to allow hex-coded inputs. In general, real DES keys and initialization vectors are not printable-ASCII characters, but they draw from a larger pool of potential input bytes.

Using the Triple-DES Encryption Algorithm to Increase Key Length

DES is secure. After forty years of cryptanalysis, no feasible attack has been demonstrated; if anybody has cracked it, they've kept it a secret. Unfortunately, the 56-bit key length is built into the algorithm. Increasing the key length requires redesigning the algorithm completely because the s-boxes and the permutations are specific to a 64-bit input. 56 bits is not very many, these days. 256 possible keys means that the most naïve brute-force attack would need to try, on the average, 255 (256 / 2), or 36,028,797,018,963,968 (about 36,000 trillion operations) before it hit the right combination. This is not infeasible; my modern laptop can repeat the non-optimized decrypt routine shown roughly 7,500 times per second. This means it would take me about 5 trillion seconds, or about 150,000 years for me to search the entire keyspace. This is a long time, but the brute-forcing process is infinitely parallelizable. If I had two computers to dedicate to the task, I could have the first search keys from 0–255 and the second search keys from 255–256. They would crack the key in about 79,000 years. If, with significant optimizations, I could increase the decryption time to 75,000 operations per second (which is feasible), I'd only need about 7,500 years with two computers. With about 7,500 computers, I'd only need a little less than two years to search through half the keyspace.

In fact, optimized, parallelized hardware has been shown to be capable of cracking a DES key by brute force in just a few days. The hardware is not cheap, but if the value of the data is greater than the cost of the specialized hardware, alternative encryption should be considered.

The proposed solution to increase the keyspace beyond what can feasibly be brute-forced is called triple DES or 3DES. 3DES has a 168-bit (56 * 3) key. It's called triple-DES because it splits the key into three 56-bit keys and repeats the DES rounds described earlier three times, once with each key. The clearest and most secure way to generate the three keys that 3DES requires is to just generate 168 bits, split them cleanly into three 56-bit chunks, and use each independently. The 3DES specification actually allows the same 56-bit key to be used three times, or to use a 112-bit key, split it into two, and reuse one of the two keys for one of the three rounds. Presumably this is allowed for backward-compatibility reasons (for example, if you have an existing DES key that you would like to or need to reuse as is), but you can just assume the simplest case where you have 168 bits to play with — this is what SSL expects when it uses 3DES as well.

One important wrinkle in the 3DES implementation is that you don't encrypt three times with the three keys. Instead you encrypt with one key, decrypt that with a different key — remember that decrypting with a mismatched key produces garbage, but reversible garbage, which is exactly what you want when doing cryptographic work — and finally encrypt that with yet a third key. Decryption, of course, is the opposite — decrypt with the third key, encrypt that with the second, and finally decrypt that with the first. Notice that you reverse the order of the keys when decrypting; this is important! The Encrypt/Decrypt/Encrypt procedure makes cryptanalysis more difficult. Note that the "use the same key three times" option mentioned earlier is essentially useless. You encrypt with a key, decrypt with the same key, and re-encrypt again with the same key to produce the exact same results as encrypting one time.

Padding and cipher-block-chaining do not change at all. 3DES works with eight-byte blocks, and you need to take care with initialization vectors to ensure that the same eight-byte block encrypted twice with the same key appears different in the output.

Adding support for 3DES to des_operate is straightforward. You add a new triplicate flag that tells the function that the key is three times longer than before and call des_block_operate three times instead of once, as shown in Listing 2-26.

Listing 2-26: "des.c" des_block_operate with 3DES support

static void des_operate( const unsigned char *input,

int input_len,

unsigned char *output,

const unsigned char *iv,

const unsigned char *key,

op_type operation,

int triplicate )

{

unsigned char input_block[ DES_BLOCK_SIZE ];

assert( !( input_len % DES_BLOCK_SIZE ) );

while ( input_len )

{

memcpy( ( void * ) input_block, ( void * ) input, DES_BLOCK_SIZE );

if ( operation == OP_ENCRYPT )

{

xor( input_block, iv, DES_BLOCK_SIZE ); // implement CBC

des_block_operate( input_block, output, key, operation );

if ( triplicate )

{

memcpy( input_block, output, DES_BLOCK_SIZE );

des_block_operate( input_block, output, key + DES_KEY_SIZE,

OP_DECRYPT );

memcpy( input_block, output, DES_BLOCK_SIZE );

des_block_operate( input_block, output, key + ( DES_KEY_SIZE * 2 ),

operation );

}

memcpy( ( void * ) iv, ( void * ) output, DES_BLOCK_SIZE ); // CBC

}

if ( operation == OP_DECRYPT )

{

if ( triplicate )

{

des_block_operate( input_block, output, key + ( DES_KEY_SIZE * 2 ),

operation );

memcpy( input_block, output, DES_BLOCK_SIZE );

des_block_operate( input_block, output, key + DES_KEY_SIZE,

OP_ENCRYPT );

memcpy( input_block, output, DES_BLOCK_SIZE );

des_block_operate( input_block, output, key, operation );

}

else { des_block_operate( input_block, output, key, operation ); } xor( output, iv, DES_BLOCK_SIZE ); memcpy( ( void * ) iv, ( void * ) input, DES_BLOCK_SIZE ); // CBC } input += DES_BLOCK_SIZE; output += DES_BLOCK_SIZE; input_len -= DES_BLOCK_SIZE; } }

If you were paying close attention in the previous section, you may have noticed that des_block_operate accepts a key as an array of a fixed size, whereas des_operate accepts a pointer of indeterminate size. Now you can see why it was designed this way.

Two new functions, des3_encrypt and des3_decrypt, are clones of des_encrypt and des_decrypt, other than the passing of a new flag into des_operate, shown in Listing 2-27.

Listing 2-27: "des.c" des3_encrypt

void des_encrypt( const unsigned char *plaintext,

...

{

des_operate( plaintext, plaintext_len, ciphertext,

iv, key, OP_ENCRYPT, 0 );

}

void des3_encrypt( const unsigned char *plaintext,...

{

des_operate( padded_plaintext, plaintext_len + padding_len, ciphertext,

iv, key, OP_ENCRYPT, 1 );

}

void des_decrypt( const unsigned char *ciphertext,

...

{

des_operate( ciphertext, ciphertext_len, plaintext, iv, key, OP_DECRYPT, 0 );

}

void des3_decrypt( const unsigned char *ciphertext,

...

{

des_operate( ciphertext, ciphertext_len, plaintext, iv, key, OP_DECRYPT, 1 );

}

You may be wondering why you created two new functions that are essentially clones of the others instead of just adding a triplicate flag to des_encrypt and des_decrypt as you did to des_operate. The benefit of this approach is that des_encrypt and des3_encrypt have identical function signatures. Later on, when you actually start developing the SSL framework, you take advantage of this and use function pointers to refer to your bulk encryption routines. You see this at work in the next section on AES, which is the last block cipher bulk encryption routine you examine. Notice also that I've removed the padding; for SSL purposes, you want to leave the padding up to the caller.

You can easily extend the test main routine in des.c to perform 3DES as shown in Listing 2-28; just check the length of the input key. If the input key is eight bytes, perform "single DES"; if it's 24 bytes, perform 3DES. Note that the block size, and therefore the initialization vector, is still eight bytes for 3DES; it's just the key that's longer.

Listing 2-28: "des.c" main routine with 3DES support

...

if ( !( strcmp( argv[ 1 ], "-e" ) ) )

{

if ( key_len == 24 )

{

des3_encrypt( input, input_len, output, iv, key );

}

else

{

des_encrypt( input, input_len, output, iv, key );

}

show_hex( output, out_len );

}

else if ( !( strcmp( argv[ 1 ], "-d" ) ) )

{

if ( key_len == 24 )

{

des3_decrypt( input, input_len, output, iv, key );

}

else

{

des_decrypt( input, input_len, output, iv, key );

}

For example,

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./des -e twentyfourcharacterinput initialz abcdefgh c0c48bc47e87ce17 [jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./des -d twentyfourcharacterinput initialz \ 0xc0c48bc47e87ce17 6162636465666768

Faster Encryption with the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) Algorithm

3DES works and is secure — that is, brute-force attacks against it are computationally infeasible, and it has withstood decades of cryptanalysis. However, it's clearly slower than it needs to be. To triple the key length, you also have to triple the operation time. If DES itself were redesigned from the ground up to accommodate a longer key, processing time could be drastically reduced.

In 2001, the NIST announced that the Rijndael algorithm (http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/fips/fips197/fips-197.pdf) would become the official replacement for DES and renamed it the Advanced Encryption Standard. NIST evaluated several competing block-cipher algorithms, looking not just at security but also at ease of implementation, relative efficiency, and existing market penetration.

If you understand the overall workings of DES, AES is easy to follow as well. Like DES, it does a non-linear s-box translation of its input, followed by several permutation- and shift-like operations over a series of rounds, applying a key-schedule to its input at each stage. Just like DES, AES relies heavily on the XOR operation — particularly the reversibility of it. However, it operates on much longer keys; AES is defined for 128-, 192-, and 256-bit keys. Note that, assuming that a brute-force attack is the most efficient means of attacking a cipher, 128-bit keys are less secure than 3DES, and 192-bit keys are about the same (although 3DES does throw away 24 bits of key security due to the parity check built into DES). 256-bit keys are much more secure. Remember that every extra bit doubles the time that an attacker would have to spend brute-forcing a key.

AES Key Schedule Computation

AES operates on 16-byte blocks, regardless of key length. The number of rounds varies depending on key length. If the key is 128 bits (16 bytes) long, the number of rounds is 10; if the key size is 192 bits (24 bytes) long, the number of rounds is 12; and if the key size is 256 bits (32 bytes), the number of rounds is 14. In general, rounds = (key-size in 4-byte words) + 6. Each round needs 16 bytes of keying material to work with, so the key schedule works out to 160 bytes (10 rounds * 16 bytes per round) for a 128-bit key; 192 bytes (12 * 16) for a 192-bit key; and 224 bytes (14 * 16) for a 256-bit key. (Actually there's one extra key permutation at the very end, so AES requires 176, 208, and 240 bytes of keying material). Besides the number of rounds, the key permutation is the only difference between the three algorithms.

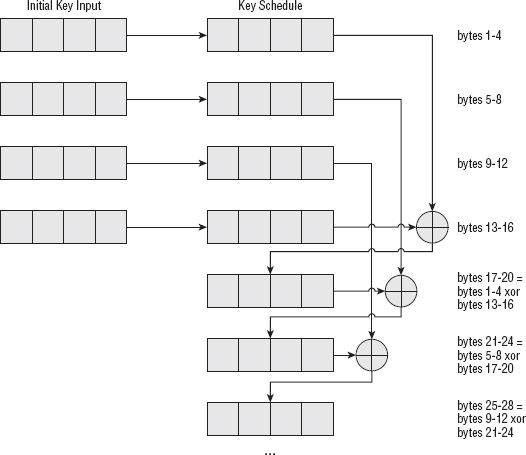

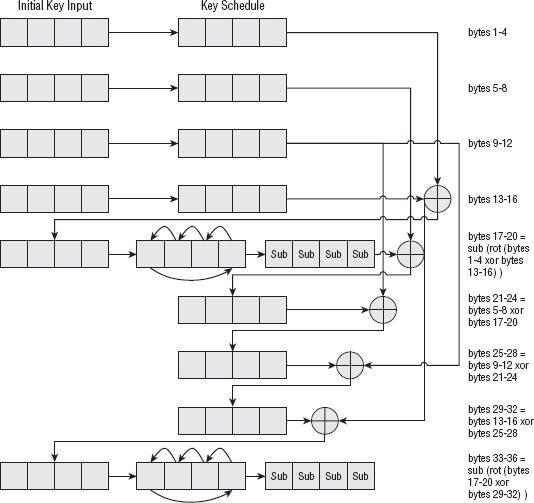

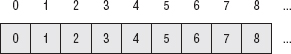

So, given a 16-byte input, the AES key schedule computation needs to produce 176 bytes of output. The first 16 bytes are the input itself; the remaining 160 bytes are computed four at a time. Each four bytes are a permutation of the previous four bytes. Therefore, key schedule bytes 17–20 are a permutation of key bytes 13–16; 21–24 are a permutation of key bytes 17–20; and so on. Three-fourths of the time, this permutation is a simple XOR operation on the previous "key length" four bytes — bytes 21–24 are the XOR of bytes 17–20 and bytes 5–8. Bytes 25–28 are the XOR of bytes 21–24 and bytes 9–12. Graphically, in the case of a 128-bit key, this can be depicted as shown in Figure 2-7.

Figure 2-7: AES 128-bit key schedule computation

For a 192-bit key, the schedule computation is shown in Figure 2-8. It's just like the 128-bit key, but copies all 24 input bytes before it starts combining them.

And the 256-bit key is the same, but copies all 32 input bytes.

This is repeated 44, 52 or 60 times (rounds * 4 + 1) to produce as much keying material as needed — 16 bytes per round, plus one extra chunk of 16 bytes.

This isn't the whole story, though — every four iterations, there's a complex transformation function applied to the previous four bytes before it is XORed with the previous key-length four bytes. This function consists of first rotating the four-byte word, then applying it to a substitution table (AES's s-box), and XORing it with a round constant.

Figure 2-8: AES 192-bit key schedule computation

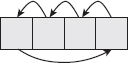

Rotation is straightforward and easy to understand. The first byte is overwritten with the second, the second with the third, the third with the fourth, and the fourth with the first, as shown in Figure 2-9 and Listing 2-29.

Listing 2-29: "aes.c" rot_word

static void rot_word( unsigned char *w ) { unsigned char tmp; tmp = w[ 0 ]; w[ 0 ] = w[ 1 ]; w[ 1 ] = w[ 2 ]; w[ 2 ] = w[ 3 ]; w[ 3 ] = tmp; }

The substitution involves looking up each byte in a translation table and then replacing it with the value found there. The translation table is 16 × 16 bytes; the row is the high-order nibble of the source byte and the column is the low-order nibble. So, for example, the input byte 0x1A corresponds to row 1, column 10 of the lookup table, and input byte 0xC5 corresponds to row 12, column 5.

Actually, the lookup table values can be computed dynamically. According to the specification, this computation is "the affine transformation (over GF(28)) of bi + b(i+4)%8 + b(i+5)%8 + b(i+6)%8 + b(i+7)%8 + ci after taking the multiplicative inverse in the finite field GF(28)". If that means anything to you, have at it.

This isn't something you'd want to do dynamically anyway, though, because the values never change. Instead, hardcode the table as shown in Listing 2-30, just as you did for DES:

Listing 2-30: "aes.c" sbox

static unsigned char sbox[ 16 ][ 16 ] = {

{ 0x63, 0x7c, 0x77, 0x7b, 0xf2, 0x6b, 0x6f, 0xc5,

0x30, 0x01, 0x67, 0x2b, 0xfe, 0xd7, 0xab, 0x76 },

{ 0xca, 0x82, 0xc9, 0x7d, 0xfa, 0x59, 0x47, 0xf0,

0xad, 0xd4, 0xa2, 0xaf, 0x9c, 0xa4, 0x72, 0xc0 },

{ 0xb7, 0xfd, 0x93, 0x26, 0x36, 0x3f, 0xf7, 0xcc,

0x34, 0xa5, 0xe5, 0xf1, 0x71, 0xd8, 0x31, 0x15 },

{ 0x04, 0xc7, 0x23, 0xc3, 0x18, 0x96, 0x05, 0x9a,

0x07, 0x12, 0x80, 0xe2, 0xeb, 0x27, 0xb2, 0x75 },

{ 0x09, 0x83, 0x2c, 0x1a, 0x1b, 0x6e, 0x5a, 0xa0,

0x52, 0x3b, 0xd6, 0xb3, 0x29, 0xe3, 0x2f, 0x84 },

{ 0x53, 0xd1, 0x00, 0xed, 0x20, 0xfc, 0xb1, 0x5b,

0x6a, 0xcb, 0xbe, 0x39, 0x4a, 0x4c, 0x58, 0xcf },

{ 0xd0, 0xef, 0xaa, 0xfb, 0x43, 0x4d, 0x33, 0x85,

0x45, 0xf9, 0x02, 0x7f, 0x50, 0x3c, 0x9f, 0xa8 },

{ 0x51, 0xa3, 0x40, 0x8f, 0x92, 0x9d, 0x38, 0xf5,

0xbc, 0xb6, 0xda, 0x21, 0x10, 0xff, 0xf3, 0xd2 },

{ 0xcd, 0x0c, 0x13, 0xec, 0x5f, 0x97, 0x44, 0x17,

0xc4, 0xa7, 0x7e, 0x3d, 0x64, 0x5d, 0x19, 0x73 }, { 0x60, 0x81, 0x4f, 0xdc, 0x22, 0x2a, 0x90, 0x88, 0x46, 0xee, 0xb8, 0x14, 0xde, 0x5e, 0x0b, 0xdb }, { 0xe0, 0x32, 0x3a, 0x0a, 0x49, 0x06, 0x24, 0x5c, 0xc2, 0xd3, 0xac, 0x62, 0x91, 0x95, 0xe4, 0x79 }, { 0xe7, 0xc8, 0x37, 0x6d, 0x8d, 0xd5, 0x4e, 0xa9, 0x6c, 0x56, 0xf4, 0xea, 0x65, 0x7a, 0xae, 0x08 }, { 0xba, 0x78, 0x25, 0x2e, 0x1c, 0xa6, 0xb4, 0xc6, 0xe8, 0xdd, 0x74, 0x1f, 0x4b, 0xbd, 0x8b, 0x8a }, { 0x70, 0x3e, 0xb5, 0x66, 0x48, 0x03, 0xf6, 0x0e, 0x61, 0x35, 0x57, 0xb9, 0x86, 0xc1, 0x1d, 0x9e }, { 0xe1, 0xf8, 0x98, 0x11, 0x69, 0xd9, 0x8e, 0x94, 0x9b, 0x1e, 0x87, 0xe9, 0xce, 0x55, 0x28, 0xdf }, { 0x8c, 0xa1, 0x89, 0x0d, 0xbf, 0xe6, 0x42, 0x68, 0x41, 0x99, 0x2d, 0x0f, 0xb0, 0x54, 0xbb, 0x16 }, };

Performing the substitution is a matter of indexing this table with the high-order four bits of each byte of input as the row and the low-order four bits as the column, which is illustrated in Listing 2-31.

Listing 2-31: "aes.c" sub_word

static void sub_word( unsigned char *w )

{

int i = 0;

for ( i = 0; i < 4; i++ )

{

w[ i ] = sbox[ ( w[ i ] & 0xF0 ) >> 4 ][ w[ i ] & 0x0F ];

}

}

Finally, the rotated, substituted value is XORed with the round constant. The low-order three bytes of the round constant are always 0, and the high-order byte starts at 0x01 and shifts left every four iterations, so that it becomes 0x02 in the eighth iteration, 0x04 in the twelfth, and so on. Therefore, the first round constant, applied at iteration #4 if the key length is 128 bits, iteration #6 if the key length is 192 bits, and iteration #8 if the key length is 256 bits, is 0x01000000. The second round constant, applied at iteration #8, #12, or #16 depending on key length, is 0x02000000. The third at iteration #12, #18, or #24 is 0x04000000, and so on.

If you've been following closely, though, you may notice that for a 128-bit key, the round constant is left-shifted 10 times because a 128-bit key requires 44 iterations with a left-shift occurring every four iterations. However, if you left-shift a single byte eight times, you end up with zeros from that point on. Instead, AES mandates that, when the left-shift overflows, you XOR the result — which in this case is zero — with 0x1B. Why 0x1B? Well, take a look at the first 51 iterations of this simple operation – left shift and XOR with 0x1B on overflow:

01, 02, 04, 08, 10, 20, 40, 80, 1b, 36, 6c, d8, ab, 4d, 9a, 2f, 5e, bc, 63, c6, 97, 35, 6a, d4, b3, 7d, fa, ef, c5, 91, 39, 72, e4, d3, bd, 61, c2, 9f, 25, 4a, 94, 33, 66, cc, 83, 1d, 3a, 74, e8, cb, 8d

After the 51st iteration, it wraps back around to 0x01 and starts repeating.

This strange-looking formulation enables you to produce unique values simply and quickly for quite a while, although the key schedule computation only requires 10 iterations (this comes up again in the column mixing in the actual encryption/decryption process). Of course, you could have just added one each time and produced 255 unique values, but the bit distribution wouldn't have been as diverse. Remember that you're XORing each time; you want widely differing bit values when you do this.

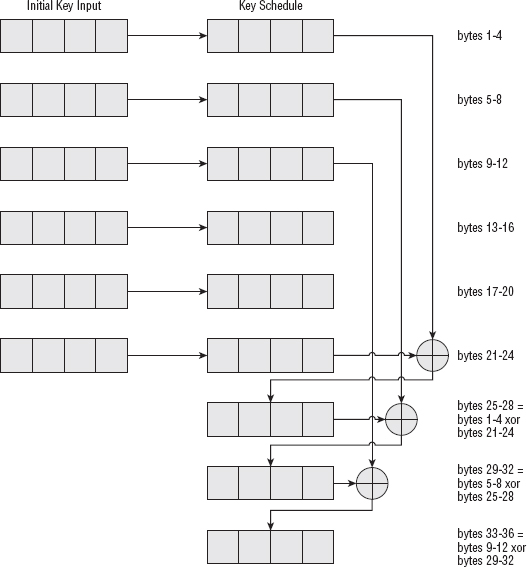

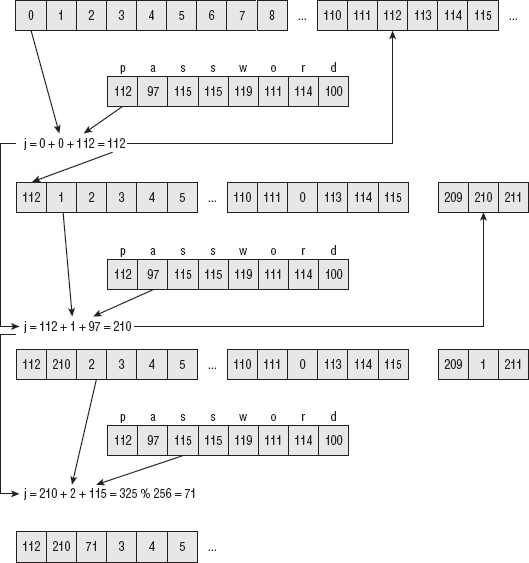

So, for a 128-bit key, the actual key schedule process looks more like what's shown in Figure 2-10.

Figure 2-10: AES 128-bit key schedule computation

The 192-bit key schedule is the same, except that the rotation, substitution and round-constant XOR is applied every sixth iteration instead of every fourth. For a 256-bit key, rotation, substitution, and XORing happens every eighth iteration. Because every eight iterations doesn't work out to that many, a 256-bit key schedule adds one small additional wrinkle — every fourth iteration, substitution takes place, but rotation and XOR — only take place every eighth iteration.

The net result of all of this is that the key schedule is a non-linear, but repeatable, permutation of the input key. The code to compute an AES key schedule is shown in Listing 2-32.

Listing 2-32: "aes.c" compute_key_schedule

static void compute_key_schedule( const unsigned char *key,

int key_length,

unsigned char w[ ][ 4 ] )

{

int i;

int key_words = key_length >> 2;

unsigned char rcon = 0x01;

// First, copy the key directly into the key schedule

memcpy( w, key, key_length );

for ( i = key_words; i < 4 * ( key_words + 7 ); i++ )

{

memcpy( w[ i ], w[ i - 1 ], 4 );

if ( !( i % key_words ) )

{

rot_word( w[ i ] );

sub_word( w[ i ] );

if ( !( i % 36 ) )

{

rcon = 0x1b;

}

w[ i ][ 0 ] ^= rcon;

rcon <<= 1;

}

else if ( ( key_words > 6 ) && ( ( i % key_words ) == 4 ) )

{

sub_word( w[ i ] );

}

w[ i ][ 0 ] ^= w[ i - key_words ][ 0 ];

w[ i ][ 1 ] ^= w[ i - key_words ][ 1 ];

w[ i ][ 2 ] ^= w[ i - key_words ][ 2 ];

w[ i ][ 3 ] ^= w[ i - key_words ][ 3 ];

}

}

Here, key_length is given in bytes, and w is the key schedule array to fill out. First copy key_length bytes directly into w, and then perform ( ( key_length / 4 ) + 6 ) * 4 iterations of the key schedule computation described above — if the iteration number is an even multiple of the key size, a rotation, substitution and XOR by the round constant of the previous four-byte word is performed. In any case, the result is XORed with the value of the previous key_length word.

The following code:

else if ( ( key_words > 6 ) && ( ( i % key_words ) == 4 ) )

{

sub_word( w[ i ] );

}

covers the exceptional case of a 256-bit key. Remember, for a 256-bit key, you have to perform a substitution every four iterations.

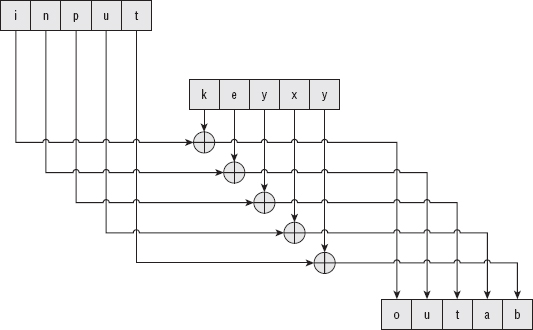

AES Encryption

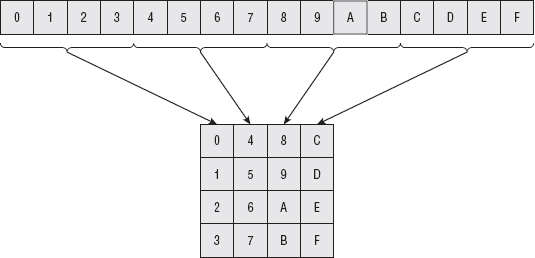

With the key schedule computation defined, you can look at the actual encryption process. AES operates on 16-byte blocks of input, regardless of key size; the input is treated as a 4 × 4 two-dimensional array of bytes. The input is mapped vertically into this array as shown in Figure 2-11.

Figure 2-11: AES state mapping initialization

This 4 × 4 array of input is referred to as the state. It should come as no surprise that the encryption process, then, consists of permuting, substituting, and combining the keying material with this state to produce the output.

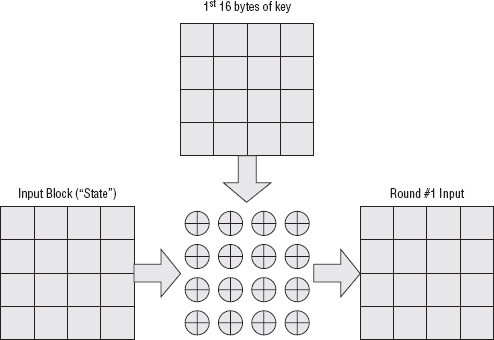

The first thing to do is to XOR the state with the first 16 bytes of keying material, which comes directly from the key itself (see Figure 2-12). This is illustrated in Listing 2-33.

Figure 2-12: AES key combination

Listing 2-33: "aes.c" add_round_key

static void add_round_key( unsigned char state[ ][ 4 ],

unsigned char w[ ][ 4 ] )

{

int c, r;

for ( c = 0; c < 4; c++ )

{

for ( r = 0; r < 4; r++ )

{

state[ r ][ c ] = state[ r ][ c ] ^ w[ c ][ r ];

}

}

}

Note that this is done before the rounds begin.

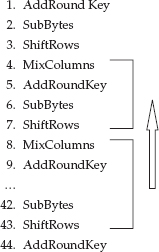

Each round consists of four steps: a substitution step, a row-shifting step, a column-mixing step, and finally a key combination step.

Substitution is performed on each byte individually and comes from the same table that the key schedule substitution came from, as in Listing 2-34.

Listing 2-34: "aes.c" sub_bytes

static void sub_bytes( unsigned char state[ ][ 4 ] ) { int r, c; for ( r = 0; r < 4; r++ ) { for ( c = 0; c < 4; c++ ) { state[ r ][ c ] = sbox[ ( state[ r ][ c ] & 0xF0 ) >> 4 ] [ state[ r ][ c ] & 0x0F ]; } } }

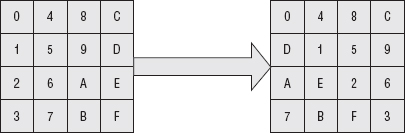

Row shifting is a rotation applied to each row. The first row is rotated zero places, the second one place, the third two, and the fourth three. Graphically, this can be viewed as shown in Figure 2-13.

In code, this is shown in Listing 2-35.

Listing 2-35: "aes.c" shift_rows

static void shift_rows( unsigned char state[ ][ 4 ] )

{

int tmp;

tmp = state[ 1 ][ 0 ];

state[ 1 ][ 0 ] = state[ 1 ][ 1 ];

state[ 1 ][ 1 ] = state[ 1 ][ 2 ];

state[ 1 ][ 2 ] = state[ 1 ][ 3 ];

state[ 1 ][ 3 ] = tmp;

tmp = state[ 2 ][ 0 ];

state[ 2 ][ 0 ] = state[ 2 ][ 2 ];

state[ 2 ][ 2 ] = tmp; tmp = state[ 2 ][ 1 ]; state[ 2 ][ 1 ] = state[ 2 ][ 3 ]; state[ 2 ][ 3 ] = tmp; tmp = state[ 3 ][ 3 ]; state[ 3 ][ 3 ] = state[ 3 ][ 2 ]; state[ 3 ][ 2 ] = state[ 3 ][ 1 ]; state[ 3 ][ 1 ] = state[ 3 ][ 0 ]; state[ 3 ][ 0 ] = tmp; }

Note that for simplicity and clarity, the position shifts are just hardcoded at each row. The relative positions never change, so there's no particular reason to compute them on each iteration.

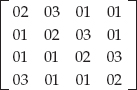

Column mixing is where AES gets a bit confusing and where it differs considerably from DES. The column mix step is actually defined as a matrix multiplication of each column in the source array with the matrix:

Multiplying Matrices

If you don't remember what matrix multiplication is, or you never studied linear algebra, this works out to multiplying each element of each column with each element of each row and then adding the results to come up with the target column. (Don't worry, I show you some code in just a second). If you do remember linear algebra, don't get too excited because AES redefines the terms multiply and add to mean something completely different than what you probably consider multiply and add.

An ordinary, traditional 4 × 4 matrix multiplication can be implemented as in Listing 2-36.

Listing 2-36: Example matrix multiplication

static void matrix_multiply( unsigned char m1[4][4],

unsigned char m2[4][4],

unsigned char target[4][4])

{

int r, c;

for ( r = 0; r < 4; r++ )

{

for ( c = 0; c < 4; c++ )

{

target[ r ][ c ] =

m1[ r ][ 0 ] * m2[ 0 ][ c ] + m1[ r ][ 1 ] * m2[ 1 ][ c ] + m1[ r ][ 2 ] * m2[ 2 ][ c ] + m1[ r ][ 3 ] * m2[ 3 ][ c ]; } } }

As you can see, each element of the target matrix becomes the sum of the rows of the first matrix multiplied by the columns of the second. As long as the first matrix has as many rows as the second has columns, two matrices can be multiplied this way. This code can be made even more general to deal with arbitrarily sized matrices, but C's multidimensional array syntax makes that tricky, and you won't need it for AES.

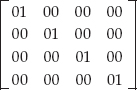

If you multiply something, there ought to be a way to unmultiply (that is, divide) it. And certainly if you're using this in an encryption operation you need a well-defined way to undo it. Matrix division is not as clear-cut as matrix multiplication, however. To undo a matrix multiplication, you must find a matrix's inverse. This is another matrix which, when multiplied, as defined above, will yield the identity matrix:

If you look back at the way matrix multiplication was defined, you can see why it's called the identity matrix. If you multiply this with any other (four-column) matrix, you get back the same matrix. This is analogous to the case of multiplying a number by 1 — when you multiply any number by the number 1 you get back the same number.

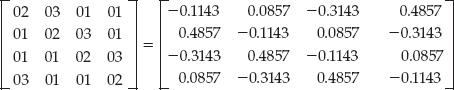

The problem with the standard matrix operations, as they pertain to encryption, is that the inversion of the matrix above is:

As you can imagine, multiplying by this inverted matrix to decrypt would be terribly slow, and the inclusion of floating point operations would introduce round-off errors as well. To speed things up, and still allow for invertible matrices, AES redefines the add and multiply operations for its matrix multiplication. This means also that you don't have to worry about the thorny topic of matrix inversion, which is fortunate because it's as complex as it looks (if not more so).

Adding in AES is actually redefined as XORing, which is nothing at all like adding. Multiplying is repeated adding, just as in ordinary arithmetic, but it's done modulo 0x1B (remember this value from the key schedule?). The specification refers to this as a dot product — another linear algebra term, but again redefined. If your head is spinning from this mathematicalese, perhaps some code will help.

To multiply two bytes — that is, to compute their dot product in AES — you XOR together the xtime values of the multiplicand with the multiplier. What are xtime values? They're the "left-shift and XOR with 0x1B on overflow" operation that described the round constant in the key schedule computation. In code, this works out to Listing 2-37.

Listing 2-37: "aes.c" dot product

unsigned char xtime( unsigned char x )

{

return ( x << 1 ) ^ ( ( x & 0x80 ) ? 0x1b : 0x00 );

}

unsigned char dot( unsigned char x, unsigned char y )

{

unsigned char mask;

unsigned char product = 0;

for ( mask = 0x01; mask; mask <<= 1 )

{

if ( y & mask )

{

product ^= x;

}

x = xtime( x );

}

return product;

}

This probably doesn't look much like multiplication to you — and, honestly, it isn't — but this is algorithmically how you'd go about performing binary multiplication if you didn't have a machine code implementation of it to do the heavy lifting for you. In fact, this concept reappears in the next chapter when the topic of arbitrary-precision binary math is examined.

Fortunately, from an implementation perspective, you can just accept that this is "what you do" with the bytes in a column-mixing operation.

Mixing Columns in AES

Armed with this strange multiplication operation, you can implement the matrix multiplication that performs the column-mixing step in Listing 2-38.

Listing 2-38: "aes.c" mix_columns

static void mix_columns( unsigned char s[ ][ 4 ] )

{

int c;

unsigned char t[ 4 ];

for ( c = 0; c < 4; c++ )

{

t[ 0 ] = dot( 2, s[ 0 ][ c ] ) ^ dot( 3, s[ 1 ][ c ] ) ^

s[ 2 ][ c ] ^ s[ 3 ][ c ];

t[ 1 ] = s[ 0 ][ c ] ^ dot( 2, s[ 1 ][ c ] ) ^

dot( 3, s[ 2 ][ c ] ) ^ s[ 3 ][ c ];

t[ 2 ] = s[ 0 ][ c ] ^ s[ 1 ][ c ] ^ dot( 2, s[ 2 ][ c ] ) ^

dot( 3, s[ 3 ] [ c ] );

t[ 3 ] = dot( 3, s[ 0 ][ c ] ) ^ s[ 1 ][ c ] ^ s[ 2 ][ c ] ^

dot( 2, s[ 3 ][ c ] );

s[ 0 ][ c ] = t[ 0 ];

s[ 1 ][ c ] = t[ 1 ];

s[ 2 ][ c ] = t[ 2 ];

s[ 3 ][ c ] = t[ 3 ];

}

}

Remembering that adding is XORing and mutiplying is dot-ing, this is a straightforward matrix multiplication. Compare this to Listing 2-35.