APPENDIX A

Binary Representation of Integers: A Primer

If you know how to program in C, you must have spent some time looking at machine-level details, including binary number representations, as you learned it. This appendix covers some of these details that you were probably familiar with at one point, but have since (maybe willfully) forgotten.

The Decimal and Binary Numbering Systems

Humans use a base-10 numbering system. Ten unique digits (including 0) represent the first nine ordinal numbers. After the ninth position, you use multiple digits to represent numerals. Anthropologists believe that the base-10 numbering system, which is ubiquitous in almost all human societies, came about because humans have 10 fingers. As it turns out, though, computers have just one such "finger" because they're electrical machines. I'll go out on a limb and assume you interact with electricity at least occasionally when you turn on a light switch — the switch is the counter which can be in two states: on and off. If it's on, electricity flows; if it's off, it doesn't.

To grossly oversimplify, a CPU is nothing but a series of interrelated electronic switches. Numbers are represented by unique combinations of multiple switches. One such switch can count two unique values. Two switches can count four: on-on, on-off, off-on and off-off. Three switches can count eight values, and n switches can count 2n values. Most modern computers are said to be 32-bit processors, which means that the internal counters are composed of 32 switches each and are capable of counting up to 232, or about 4.3 billion.

The binary numbering system works, at a logical level at least, just like the decimal system. With decimal numbers, the first nine digits are represented (for instance) by the Arabic numerals 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. After 9, a tens-place is introduced, and 90 more unique numerals can be represented. After this, a hundreds-place is introduced, and 900 more unique numerals can be represented, and so on. Algebraically, the numeral 97,236 is 9 * 104 + 7 * 103 + 2 * 102 + 3 * 101 + 6 * 100.

Binary numbers are usually represented with just two digits — 0 and 1 — corresponding to the off and on states of the internal hardware. It takes quite a few more digits to represent a number in binary than in decimal, but any number that can be expressed in one can be converted to the other. The binary number 11011010 is equal to 1 * 27 + 1 * 26 + 0 * 25 + 1 * 24 + 1 * 23 + 0 * 22 + 1 * 21 + 0 * 20 = 218.

It's customary to delimit binary numbers at the byte level, where one byte consists of eight bits. There's no technical reason why this has to be eight bits (although hardware design is slightly easier when the number of bits is a power of 2). In the early days of computing, when communications providers charged by the bit (!), early airline reservation systems adopted a five-bit byte to save on communication costs.

Understanding Binary Logical Operations

Binary numbers can be added, subtracted, multiplied and divided just like decimal numbers. Every computing device in existence has a dedicated circuit called an Arithmetic Logical Unit (ALU) whose purpose is to take as input two or more numbers in binary form and output the result of a mathematical operation on those numbers. This is done using more primitive operations on binary numbers — AND, OR, NOT, and XOR.

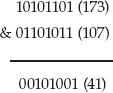

The AND Operation

The AND operation operates at a bit-level. If both bits are 1, AND returns 1. If either bit is 0, AND returns 0. In other words, only if x is on AND y is on are x AND y on. C exposes the AND operation via the & operator, and it works on whole bytes. The result of C's & operator is the AND of each bit in the first operand with the corresponding bit in the second operand.

There's no mathematical relationship between the two operands and their output; the & operation just sets the bits that match in both operands. In C, this is useful to check the value of a single bit — if you compute x & 00010000, you get 0 if the fifth bit (counting from the right) is unset, and you get 32 if it isn't. You can put this into a logical operation such as

if ( x & 00010000 ) { do_something(); }

because C considers non-zero to be "true."

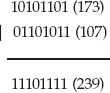

The OR Operation

The OR operation is sort of the opposite. If x is on OR y is on, then x OR y is on. If x is off and y is on, x OR y is on. If x is on and y is off, x OR y is on. The only way OR returns off is if x and y are both off. C exposes this via the | operator. This is useful to optionally set a bit without changing others. If you want to set the fifth bit of x, you can compute x = x | 00010000. This won't change the values of the other bits but does force the fifth bit of x to be 1 even if it was 0 before. For example,

Compare this with the AND output in the previous section. Again, there's no mathematical relationship between the input and the output.

The NOT Operation

The NOT operation, C's ~ operator, inverts a bit. 0 becomes 1 and 1 becomes 0.

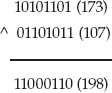

The XOR Operation

Finally, the Exclusive OR (XOR) operation is just like OR, except that if both bits are 1, the output is 0. For example,

What makes XOR particularly interesting is that it's invertible; this important property is examined in depth in Chapter 2.

Position Shifting of Binary Numbers

Binary numbers can also meaningfully be shifted. Shifting a binary number consists of moving all of the bits in one direction. Just as adding a zero to a decimal number multiplies it by 10, shifting the bits in a binary number to the left doubles its value. Similarly, shifting to the right halves it.

Two's-Complement Representation of Negative Numbers

Because humans are so bad at performing mathematical computations, computers were invented to reliably add and subtract numbers. Although we've found a few additional purposes for which we can use computers, they're still fundamentally adding and subtracting machines. However, no computer can add or subtract infinitely. Every ALU has a register size that dictates how many bits represent a number; if an arithmetic operation needs more bits than the register size, the operation overflows, and wraps back around to a logically smaller number.

The idea behind two's-complement arithmetic is to split the available space in half, assigning one half positive numbers and the other negative numbers. Because, logically, negative numbers are smaller than positive numbers, you might guess that the first (lowest) half are the negative numbers and that the last half are the positive numbers. However, for compatibility with unsigned numbers, the first half are the positives, and the last half are the negatives.

Because the last (greatest) half of any binary number space is the half with the most-significant-bit (MSB) set, this provides an easy check for a negative number — if the MSB is set, the number is negative. This also simplifies the process of negating a number. If you just invert the bits — apply the NOT operation on all of them — you get the proper representation of the same number, with the sign reversed. This representation is called one's complement arithmetic. The only trick here is that if you invert 0 — binary 00000000 — you get 11111111. This is –0, which doesn't make any sense because 0 is neither negative nor positive. To get around this, two's-complement arithmetic inverts the number and adds one. This means that there is one more negative number than there are positive numbers.

Generally, you don't need to worry much about negative number representation or two's-complement arithmetic unless you're displaying a number; printf, for example, needs to know whether a number with its MSB set is a negative number or a very large positive number. The only other time this comes up is when you start shifting numbers. Remember that shifting to the right halves a binary number? Well, if that number is negative, you must preserve the sign bit to keep the number negative. Therefore, the shift operation behaves differently with a signed number than with an unsigned one; if an unsigned number is shifted right, the MSB becomes 0 in all cases. If a signed integer is shifted right, the MSB is preserved, and becomes the next-most-significant-bit.

Consider the binary number 10101101. Interpreted as an unsigned integer, this is decimal 173. Interpreted as a signed integer, this is –81; invert all of the bits except the sign bit and add one and you get 1010011. So, if the unsigned integer is divided in half, the answer should be 86, which 01010110 is if you right-shift each digit by 1 place and put a 0 in as the new MSB. However, the signed integer, shifted once to the right, should be –40, which is binary 11010110. And, if you shift 10101101 (–81) to the right, but keep the MSB as a 1, you'll get the correct answer.

For this reason, if you need to apply bit-shifting operations, which come up quite a bit in cryptographic programming, you need to pay careful attention to the signed-ness of your variables.

Big-Endian versus Little-Endian Number Formats

Bits are usually segmented into bytes, which are eight bits. (Another term you'll come across eventually is the nybble, which is four bits. Get it? A small byte is a nybble). Bits within a byte are logically numbered right-to-left in increasing order, just like decimal numbers are; in the decimal number 97,236, the 6 is the least-significant digit, because changing it alters the numeric value the least. The 9 is the most-significant digit; if the fifth digit of your bank balance changes overnight, for example, you'll probably start investigating immediately.

Binary numbers have a most-significant and a least-significant digit; by convention, they're written ordered left-to-right in decreasing significance, but this convention has no bearing on how the computer hardware actually implements them. In fact, Intel hardware orders them the other way internally. This implementation detail isn't important except for the fact that when a number expands beyond the value 255 that a single eight-bit byte can represent, it expands not to the left, but to the right. What goes on inside a single byte is none of your concern. Unfortunately, it is your concern if you use multiple bytes to represent a number and you want to communicate with other software systems.

The reason you need to care about this is that the computer systems of the early Internet used what is called a big-endian numbering convention, where bytes are listed in decreasing order of significance, with the most significant byte occurring first. If you want to transmit a number to one of these systems, one byte at a time, you must transmit the most significant byte first. If your computer stores the least-significant byte first in memory, which is known as the little-endian convention, you must reverse these bytes before transmitting, or the other side will get the wrong answer.

Listing A-1 illustrates the problem with internal byte ordering.

Listing A-1: "endian.c"

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main( int argc, char *argv[ ] )

{

int i;

int x = 3494632738; // 32 bit integer

unsigned char y[ 4 ]; // same integer in 8 bit chunks

memcpy( y, &x, sizeof( int ) );

printf( "%x\n", x );

for ( i = 0; i < 4; i++ )

{

printf( "%.02x, ", y[ i ] );

}

printf( "\n" );

}

If you run this on a little-endian machine, you see this:

[jdavies@localhost c]$ ./endian d04bdd22 22, dd, 4b, d0,

As you see, although the most-significant-byte-first representation is d04bdd22, its internal representation is backward, and starts with the least significant byte. Unfortunately, if you stream this or any other integer over a socket connection, you are streaming it one byte at a time, and therefore in the wrong order. You can find numerous references in this text to the functions htonl and htons which convert from host to network longs and shorts, respectively, and ntohl and ntohs which reverse this. Network order is always big-endian — the dominant computers of the early Internet (which almost nobody actually uses anymore) firmly established this. Host order is whatever the individual host wants it to be — and this is almost always little endian these days.