CHAPTER 6

A Usable, Secure Communications Protocol: Client-Side TLS

Armed with symmetric encryption to protect sensitive data from eavesdroppers, public-key encryption to exchange keys securely over an insecure medium, message authentication to ensure message integrity, and certificates and their digital signatures to establish trust, it's possible to create a secure protocol that operates over an insecure line without any prior interaction between parties. This is actually pretty amazing when you think about it. You can assume that anybody who's interested in snooping on your traffic has full and complete access to it. Nevertheless, it's possible to securely send data such that only the intended recipient can read it, and be assured, within reason, that you're communicating with the intended recipient and not an impostor.

Even with all the pieces in place, though, it's possible to get this subtly wrong. This is why the TLS protocol was developed — even if you use the strongest cryptography, key exchange, MAC and signature algorithms available, you can still leave yourself vulnerable by improper use of random numbers, improper seeding of random number generation, improper verification of parameters, and a lot of other, subtle, easy-to-overlook flaws. TLS was designed as a standard for secure communications. You must, of course, use strong, secure cryptographic algorithms; the best way to ensure this is to use standard algorithms that were designed and have been thoroughly reviewed by security professionals for years. To ensure that you're using them correctly, your best bet is to also follow a standard protocol that was also designed and has been thoroughly reviewed by security professionals for years.

FROM SSLV2 TO TLS 1.2: THE HISTORY OF THE SSL PROTOCOL

SSL is currently on its fifth revision over its fifteen-year history, and has undergone one name change and one ownership change in that time period. This book focuses mainly on TLS 1.0, which is the version in most widespread use. This section looks over the history of the protocol at a high level. This overview is a helpful segue into the details of TLS 1.0 — some elements of TLS 1.0 make the most sense if you understand the problems with its predecessors that it means to solve.

SSLv2: The First Widespread Attempt at a Secure Browser Protocol

In 1995, most people had never heard of a "web browser." The Internet itself had been a reality for quite a while, but it was clear to a handful of visionaries that the World Wide Web is what would bring networked computing to the masses. Marc Andreessen had written Mosaic, the first graphical web browser, while at the University of Illinois. At the time, Mosaic was incredibly popular, so Andreessen started a company named Netscape which was going to create the computing platform of the future — the Netscape browser (and its companion server).

The World Wide Web was to become the central platform for the fledgling "e-commerce" industry. There was one problem, though — its users didn't trust it with their sensitive data. In 1995, Kipp Hickman, then an employee of Netscape Communications, drafted the first public revision of SSLv2, which was at the time viewed as an extension to HTTP that would allow the user to establish a secure link on a nonsecure channel using the concepts and techniques examined in previous chapters.

Although SSLv2 mostly got it right, it overlooked a couple of important details that rendered it, while not useless, not as secure as it ought to have been. The details of SSLv2 aren't examined in detail here, but if you're curious, Appendix C includes a complete examination of the SSLv2 protocol.

The cracks in SSLv2 were identified after it was submitted for peer review, and Netscape withdrew it, following up with SSLv3 in 1996. However, by this time, in spite of the fact that it was never standardized or ratified by the IETF, SSLv2 had found its way into several commercial browser and server implementations. Although its use has been deprecated for a decade, you may still run across it from time to time. However, it's considered to be too unsafe to the extent that the Payment Card Industry, which regulates the use of credit cards on the Internet, no longer permits websites that support SSLv2 to even accept credit cards.

SSL 3.0, TLS 1.0, and TLS 1.1: Successors to SSLv2

The IETF was much happier with the SSLv3 proposal; however, it made a few superficial changes before formally accepting it. The most significant superficial change was that, for whatever reason, they decided to change the name from the widespread, recognizable household name "SSL" to the somewhat awkward "TLS." SSLv3.1 became TLS v1.0. To this day, the version numbers transmitted and published in a TLS connection are actually SSL versions, not TLS versions. TLS 1.0 was formally specified by RFC 2246 in 1999.

Although SSLv3 was also never officially ratified by the IETF, SSLv3 and TLS 1.0 are both widespread. Most current commercial implementations of SSL/TLS support both SSLv3 and TLS 1.0; TLS also includes a mechanism to negotiate the highest version supported. SSLv3 and TLS 1.0, although similar except for some cosmetic differences, are not interoperable — a client that only supports SSLv3 cannot establish a secure connection with a server that only supports TLS 1.0. However, a client that supports both can ask for TLS 1.0 and be gracefully downgraded to SSLv3.

At the time of this writing, SSLv3 and TLS 1.0 are by far the most widespread implementations of the protocol. In 2006, a new version, 1.1, was released in RFC 4346; it's not radically different than TLS 1.0, and the few differences are examined at the end of this chapter. Two years later, TLS 1.2 was released, and it was a major revision; TLS 1.2 is covered in depth in Chapter 9.

This chapter focuses on TLS 1.0. A complete implementation of the client-side of TLS 1.0 is presented here in some detail.

Implementing the TLS 1.0 Handshake (Client Perspective)

As much as possible, TLS aims to be completely transparent to the upper-layer protocol. Effectively, this means that it tries to be completely transparent to the application programmer; the application programmer implements the protocol in question as if TLS was not being used. As long as nothing goes wrong, TLS succeeds admirably in this goal; although, as you'll see, if something does go wrong, everything fails miserably and the developer is left scratching his head, trying to figure out what he missed.

Of course, TLS can't be completely transparent. The application must indicate in some way that it wants to negotiate a secure channel. Perhaps surprisingly, TLS doesn't specify how the application should do this nor does it even provide any guidance. Remembering that SSL was initially developed as an add-on to HTTP, this makes some sense. The protocol designers weren't thinking about applicability to other protocols at the time. In fact, they didn't even specify how to use HTTP with SSL, assuming that there was only way to do so. It actually wasn't until 2000 that Eric Rescorla finally drafted RFC 2818 that describes how it should be done.

TLS requires that the handshake — a secure key exchange — takes place before it can protect anything. Effectively the question is when the handshake should take place; anything that's transmitted before the handshake is complete is transmitted in plaintext and is theoretically interceptable. HTTPS takes an extreme position on this. The very first thing that must take place on the channel is the TLS handshake; no HTTP data can be transmitted until the handshake is complete.

You can probably spot a problem with this approach. HTTP expects the very first byte(s) on the connection to be an HTTP command such as GET, PUT, POST, and so on. The client has to have some way of warning the server that it's going to start with a TLS negotiation rather than a plaintext HTTP command. The solution adopted by HTTPS is to require secure connections to be established on a separate port. If the client connects on port 80, the next expected communication is a valid HTTP command. If the client connects on port 443, the next expected communication is a TLS handshake after which, if the handshake is successful, an encrypted, authenticated valid HTTP command is expected.

Adding TLS Support to the HTTP Client

To add TLS support to the HTTP client developed in Chapter 1, you define four new top-level functions as shown in Listing 6-1.

Listing 6-1: "tls.h" top-level function prototypes

/**

* Negotiate an TLS channel on an already-established connection

* (or die trying).

* @return 1 if successful, 0 if not.

*/

int tls_connect( int connection,

TLSParameters *parameters );

/**

* Send data over an established TLS channel. tls_connect must already

* have been called with this socket as a parameter.

*/

int tls_send( int connection,

const char *application_data,

int length,

int options,

TLSParameters *parameters );

/**

* Received data from an established TLS channel.

*/

int tls_recv( int connection,

char *target_buffer,

int buffer_size,

int options,

TLSParameters *parameters );

/**

* Orderly shutdown of the TLS channel (note that the socket itself will

* still be open after this is called). */ int tls_shutdown( int connection, TLSParameters *parameters );

The primary "goal" of tls_connect is to fill in the TLSParameters structure that is passed in. It contains, among other things, the negotiated encryption and authentication algorithms, along with the negotiated keys. Because this structure is large and complex, it is built up incrementally throughout the course of this chapter; the bulk of this chapter is dedicated to filling out the tls_connect function and the TLSParamaters structure.

To apply these to an HTTP connection, open it as usual but immediately call tls_connect, which performs a TLS handshake. Afterward, assuming it succeeds, replace all calls to send and recv with tls_send and tls_recv. Finally, just before closing the socket, call tls_shutdown. Note that SSLv2 didn't have a dedicated shutdown function — this opened the connection to subtle attacks.

In order to support HTTPS, the first thing you'll need to do is to modify the main routine in http.c to start with a TLS handshake as shown in Listing 6-2.

Listing 6-2: "https.c" main routine

#define HTTPS_PORT 443

...

int main( int argc, char *argv[ ] )

{

int client_connection;

char *host, *path;

struct hostent *host_name;

struct sockaddr_in host_address;

int port = HTTPS_PORT;

TLSParameters tls_context;

...

printf( "Connection complete; negotiating TLS parameters\n" );

if ( tls_connect( client_connection, &tls_context ) )

{

fprintf( stderr, "Error: unable to negotiate TLS connection.\n" );

return 3;

}

printf( "Retrieving document: '%s'\n", path );

http_get( client_connection, path, host, &tls_context );

display_result( client_connection, &tls_context );

tls_shutdown( client_connection, &tls_context );

...

Here, http_get and display_result change only slightly, as shown in Listing 6-3; they take an extra parameter indicating the new tls_context, and they call tls_send and tls_recv to send and receive data; otherwise, they're identical to the functions presented in Chapter 1:

Listing 6-3: "https.c" http_get and display_result

int http_get( int connection, const char *path, const char *host,

TLSParameters *tls_context )

{

static char get_command[ MAX_GET_COMMAND ];

sprintf( get_command, "GET /%s HTTP/1.1\r\n", path );

if ( tls_send( connection, get_command,

strlen( get_command ), 0, tls_context ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

sprintf( get_command, "Host: %s\r\n", host );

if ( tls_send( connection, get_command,

strlen( get_command ), 0, tls_context ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

strcpy( get_command, "Connection: Close\r\n\r\n" );

if ( tls_send( connection, get_command,

strlen( get_command ), 0, tls_context ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

return 0;

}

void display_result( int connection, TLSParameters *tls_context )

{

...

while ( ( received = tls_recv( connection, recv_buf,

BUFFER_SIZE, 0, tls_context ) ) >= 0 )

{

recv_buf[ received ] = '\0';

printf( "data: %s", recv_buf );

}

...

Notice that the proxy negotiation part of http_get is missing from Listing 6-3. Negotiating proxies is a major complication for SSL; by now you can probably see why. The proxy performs the HTTP connection on behalf of the client and then returns the results back to it. Unfortunately this is by definition a man-in-the-middle attack. HTTPS can, of course, be extended to work correctly behind a proxy. This topic is revisited in Chapter 10.

Otherwise, this is it. After the tls_connect, tls_send, tls_recv, and tls_shutdown routines are complete, this client is HTTPS-compliant. If you are inclined to extend display_result to parse the HTML response and build a renderable web page, you can do so without giving a single thought to whether or not the connection is secure. If you add support for POST, HEAD, PUT, DELETE, and so on into the client-side implementation, you do so just as if the connection was plaintext; just be sure to call tls_send instead of send. Of course, you should probably extend this to actually pay attention to the protocol and perform a TLS connection only if the user requested "https" instead of "http." I'll leave that as an exercise for you if you're interested.

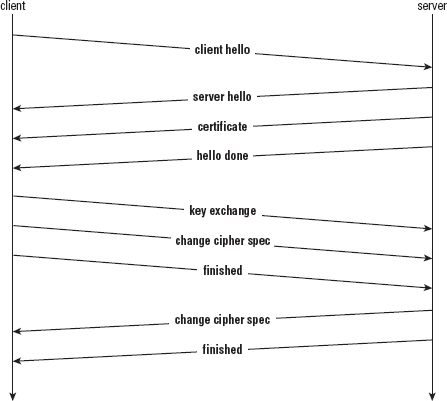

Understanding the TLS Handshake Procedure

Most of the complexity is in the handshake; after the handshake has been completed, sending and receiving is just a matter of encrypting/decrypting, MAC'ing/verifying data before/after it's received. At a high-level, the handshake procedure is as shown in Figure 6-1.

The client is responsible for sending the client hello that gets the ball rolling and informs the server, at a minimum, what version of the protocol it understands and what cipher suites (cryptography, key exchange, and authentication triples) it is capable of working with. It also transmits a unique random number, which is important to guard against replay attacks and is examined in depth later.

The server selects a cipher suite, generates its own random number, and assigns a session ID to the TLS connection; each connection gets a unique session ID. The server also sends enough information to complete a key exchange. Most often, this means sending a certificate including an RSA public key.

The client is then responsible for completing the key exchange using the information the server provided. At this point, the connection is secured, both sides have agreed on an encryption algorithm, a MAC algorithm, and respective keys. Of course, the whole process is quite a bit more complex than this, but you may want to keep this high-level overview in mind as you read the remainder of this chapter.

TLS Client Hello

Every step in the TLS handshake is responsible for updating some aspect of the TLSParameters structure. As you can probably guess, the most important values are the MAC secret, the symmetric encryption key, and, if applicable, the initialization vector. These are defined in the ProtectionParameters structure shown in Listing 6-4.

Listing 6-4: "tls.h" ProtectionParameters

typedef struct

{

unsigned char *MAC_secret;

unsigned char *key;

unsigned char *IV;

...

}

ProtectionParameters;

Tracking the Handshake State in the TLSParameters Structure

TLS actually allows a different MAC secret, key, and IV to be established for the sender and the receiver. Therefore, the TLSParameters structure keeps track of two sets of ProtectionParameters as shown in Listing 6-5.

#define MASTER_SECRET_LENGTH 48 typedef unsigned char master_secret_type[ MASTER_SECRET_LENGTH ]; #define RANDOM_LENGTH 32 typedef unsigned char random_type[ RANDOM_LENGTH ]; typedef struct { master_secret_type master_secret; random_type client_random; random_type server_random; ProtectionParameters pending_send_parameters; ProtectionParameters pending_recv_parameters; ProtectionParameters active_send_parameters; ProtectionParameters active_recv_parameters; // RSA public key, if supplied public_key_info server_public_key; // DH public key, if supplied (either in a certificate or ephemerally) // Note that a server can legitimately have an RSA key for signing and // a DH key for key exchange (e.g. DHE_RSA) dh_key server_dh_key; ... } TLSParameters;

TLS 1.0 is SSL version 3.1, as described previously. The pending_send_parameter and pending_recv_parameters are the keys currently being exchanged; the TLS handshake fills these out along the way, based on the computed master secret. The master secret, server random, and client random values are likewise provided by various hello and key exchange messages; the public keys' purpose ought to be clear to you by now.

What about this active_send_parameters and active_recv_parameters? After the TLS handshake is complete, the pending parameters become the active parameters, and when the active parameters are non-null, the parameters are used to protect the channel. Separating them this way simplifies the code; you could get away with a single set of send and recv parameters in the TLSParameters structure, but you'd have to keep track of a lot more state in the handshake code.

Both the TLSParameters and ProtectionParameters structures are shown partially filled out in Listings 6-4 and 6-5; you add to them along the way as you develop the client-side handshake routine.

As always, you need a couple of initialization routines, shown in Listing 6-6.

Listing 6-6: "tls.c" init_parameters

static void init_protection_parameters( ProtectionParameters *parameters ) { parameters->MAC_secret = NULL; parameters->key = NULL; parameters->IV = NULL; ... } static void init_parameters( TLSParameters *parameters ) { init_protection_parameters( ¶meters->pending_send_parameters ); init_protection_parameters( ¶meters->pending_recv_parameters ); init_protection_parameters( ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); init_protection_parameters( ¶meters->active_recv_parameters ); memset( parameters->master_secret, '\0', MASTER_SECRET_LENGTH ); memset( parameters->client_random, '\0', RANDOM_LENGTH ); memset( parameters->server_random, '\0', RANDOM_LENGTH ); ... }

So, tls_connect, shown partially in Listing 6-7, starts off by calling init_parameters.

Listing 6-7: "tls.c" tls_connect

/**

* Negotiate TLS parameters on an already-established socket.

*/

int tls_connect( int connection,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

init_parameters( parameters );

// Step 1. Send the TLS handshake "client hello" message

if ( send_client_hello( connection, parameters ) < 0 )

{

perror( "Unable to send client hello" );

return 1;

}

...

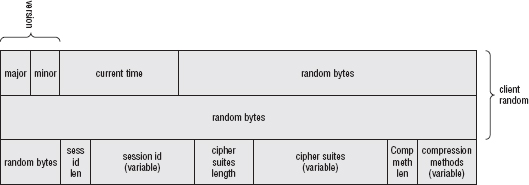

Recall from the overview that the first thing the client should do is send a client hello message. The structure of this message is defined in Listing 6-8.

Listing 6-8: "tls.h" client hello structure

typedef struct

{

unsigned char major, minor;

}

ProtocolVersion;

typedef struct { unsigned int gmt_unix_time; unsigned char random_bytes[ 28 ]; } Random; /** * Section 7.4.1.2 */ typedef struct { ProtocolVersion client_version; Random random; unsigned char session_id_length; unsigned char *session_id; unsigned short cipher_suites_length; unsigned short *cipher_suites; unsigned char compression_methods_length; unsigned char *compression_methods; } ClientHello;

Listing 6-9 shows the first part of the send_client_hello function, which is responsible for filling out a ClientHello structure and sending it on to the server.

Listing 6-9: "tls.c" send_client_hello

/**

* Build and submit a TLS client hello handshake on the active

* connection. It is up to the caller of this function to wait

* for the server reply.

*/

static int send_client_hello( int connection, TLSParameters *parameters )

{

ClientHello package;

unsigned short supported_suites[ 1 ];

unsigned char supported_compression_methods[ 1 ];

int send_buffer_size;

char *send_buffer;

void *write_buffer;

time_t local_time;

int status = 1;

package.client_version.major = TLS_VERSION_MAJOR;

package.client_version.minor = TLS_VERSION_MINOR;

time( &local_time );

package.random.gmt_unix_time = htonl( local_time );

// TODO - actually make this random.

// This is 28 bytes, but client random is 32 - the first four bytes of

// "client random" are the GMT unix time computed above. memcpy( parameters->client_random, &package.random.gmt_unix_time, 4 ); memcpy( package.random.random_bytes, parameters->client_random + 4, 28 ); package.session_id_length = 0; package.session_id = NULL; // note that this is bytes, not count. package.cipher_suites_length = htons( 2 ); supported_suites[ 0 ] = htons( TLS_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA ); package.cipher_suites = supported_suites; package.compression_methods_length = 1; supported_compression_methods[ 0 ] = 0; package.compression_methods = supported_compression_methods;

NOTE Notice that the client random isn't entirely random — the specification actually mandates that the first four bytes be the number of seconds since January 1, 1970. Fortunately, C has a built-in time function to compute this. The remaining 28 bytes are supposed to be random. The most important thing here is that they be different for each connection.

The session ID is left empty, indicating that a new session is being requested (session reuse is examined in Chapter 8). To complete the ClientHello structure, the supported cipher suites and compression methods are indicated. Only one of each is given here: For the cipher suite, it's RSA key exchange; 3DES (EDE) with CBC for encryption; and SHA-1 for MAC. The compression method selected is "no compression." TLS allows the client and sender to agree to compress the stream before encrypting.

You may be wondering, legitimately, what compression has to do with security. Nothing, actually — however, it was added to TLS and, at the very least, both sides have to agree not to compress. If the stream is going to be compressed, however, it is important that compression be applied before encryption. One property of secure ciphers is that they specifically not be compressible, so if you try to compress after encrypting, it will be too late.

Describing Cipher Suites

So, what about this TLS_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA value? Strictly speaking, it's not always safe to "mix and match" encryption functions with key exchange and MAC functions, so TLS defines them in triples rather than allowing the two sides to select them à la carte. As a result, each allowed triple has a unique identifier: TLS_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA is 10 or 0x0A hex. Go ahead and define a CipherSuiteIdentifier enumeration as shown in Listing 6-10.

TLS_RSA_WITH_NULL_MD5 = 0x0001, TLS_RSA_WITH_NULL_SHA = 0x0002, TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_RC4_40_MD5 = 0x0003, TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_MD5 = 0x0004, TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_SHA = 0x0005, TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_RC2_CBC_40_MD5 = 0x0006, TLS_RSA_WITH_IDEA_CBC_SHA = 0x0007, TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_DES40_CBC_SHA = 0x0008, TLS_RSA_WITH_DES_CBC_SHA = 0x0009, TLS_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA = 0x000A, ... } CipherSuiteIdentifier;

Notice the NULL cipher suites 0, 1 and 2. TLS_NULL_WITH_NULL_NULL indicates that there's no encryption, no MAC and no key exchange. This is the default state for a TLS handshake — the state it starts out in. Cipher suites 1 and 2 allow a non-encrypted, but MAC'ed, cipher suite to be negotiated. This can actually be pretty handy when you're trying to debug something and you don't want to have to decrypt what you're trying to debug. Unfortunately for the would-be debugger, for obvious security reasons, most servers won't allow you to negotiate this cipher suite by default.

There's no particular rhyme or reason to the identifiers assigned to the various cipher suites. They're just a sequential list of every combination that the writers of the specification could think of. They're not even grouped together meaningfully; the RSA key exchange cipher suites aren't all in the same place because after the specification was drafted, new cipher suites that used the RSA key exchange method were identified. It would certainly have been nicer, from an implementer's perspective, if they had allocated, say, three bits to identify the key exchange, five bits to identify the symmetric cipher, two for the MAC, and so on.

Additional cipher suites are examined later on. For now, you're just writing a client that understands only 3DES, RSA, and SHA-1.

Flattening and Sending the Client Hello Structure

Now that the ClientHello message has been built, it needs to be sent on. If you look at RFC 2246, which describes TLS, you see that the formal description of the client hello message looks an awful lot like the C structure defined here. You may be tempted to try to just do something like this:

send( connection, ( void * ) &package, sizeof( package ), 0 );

This is tempting, but your compiler thwarts you at every turn, expanding some elements, memory-aligning others, and generally performing unexpected optimizations that cause your code to run faster and work better (the nerve!). Although it is possible to include enough compiler directives to force this structure to appear in memory just as it needs to appear on the wire, you'd be, at the very least, locking yourself into a specific platform. As a result, you're better off manually flattening the structure to match the expected wire-level interface as shown in Listing 6-11:

Listing 6-11: "tls.c" send_client_hello (continued in Listing 6-13)

// Compute the size of the ClientHello message after flattening.

send_buffer_size = sizeof( ProtocolVersion ) +

sizeof( Random ) +

sizeof( unsigned char ) +

( sizeof( unsigned char ) * package.session_id_length ) +

sizeof( unsigned short ) +

( sizeof( unsigned short ) * 1 ) +

sizeof( unsigned char ) +

sizeof( unsigned char );

write_buffer = send_buffer = ( char * ) malloc( send_buffer_size );

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * )

&package.client_version.major, 1 );

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * )

&package.client_version.minor, 1 );

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * )

&package.random.gmt_unix_time, 4 );

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * )

&package.random.random_bytes, 28 );

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * )

&package.session_id_length, 1 );

if ( package.session_id_length > 0 )

{

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer,

( void * )package.session_id,

package.session_id_length );

}

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer,

( void * ) &package.cipher_suites_length, 2 );

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer,

( void * ) package.cipher_suites, 2 );

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer,

( void * ) &package.compression_methods_length, 1 );

if ( package.compression_methods_length > 0 )

{

write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer,

( void * ) package.compression_methods, 1 );

}

The append_buffer function, in Listing 6-12, is a convenience routine designed to be called incrementally as in Listing 6-11.

Listing 6-12: "tls.c" append buffer

/** * This is just like memcpy, except it returns a pointer to dest + n instead * of dest, to simplify the process of repeated appends to a buffer. */ static char *append_buffer( char *dest, char *src, size_t n ) { memcpy( dest, src, n ); return dest + n; }

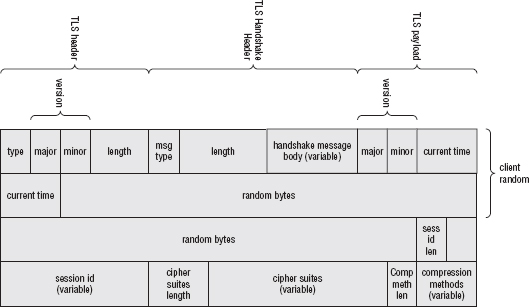

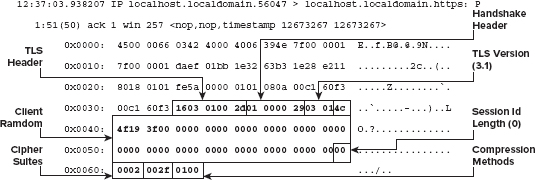

This flattened structure is illustrated in Figure 6-2.

Figure 6-2: Client hello structure

Finally, the client hello is sent off in Listing 6-13:

Listing 6-13: "tls.c" send_client_hello (continued from Listing 6-11)

assert( ( ( char * ) write_buffer - send_buffer ) == send_buffer_size );

status = send_handshake_message( connection, client_hello, send_buffer,

send_buffer_size );

free( send_buffer );

return status;

}

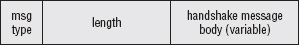

Notice that send still isn't called. Instead, you invoke send_handshake_message. Like TCP and IP, and network programming in general, TLS is an onion-like nesting of headers. Each handshake message must be prepended with a header indicating its type and length. The definition of the handshake header is shown in Listing 6-14.

Listing 6-14: "tls.h" handshake structure

/** * Handshake message types (section 7.4) */ typedef enum { hello_request = 0, client_hello = 1, server_hello = 2, certificate = 11, server_key_exchange = 12, certificate_request = 13, server_hello_done = 14, certificate_verify = 15, client_key_exchange = 16, finished = 20 } HandshakeType; /** * Handshake record definition (section 7.4) */ typedef struct { unsigned char msg_type; unsigned int length; // 24 bits(!) } Handshake;

This structure is illustrated in Figure 6-3.

Figure 6-3: TLS handshake header

The send_handshake_message function that prepends this header to a handshake message is shown in Listing 6-15.

Listing 6-15: "tls.c" send_handshake_message

static int send_handshake_message( int connection,

int msg_type,

const unsigned char *message,

int message_len )

{

Handshake record;

short send_buffer_size;

unsigned char *send_buffer;

int response; record.msg_type = msg_type; record.length = htons( message_len ) << 8; // To deal with 24-bits... send_buffer_size = message_len + 4; // space for the handshake header send_buffer = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( send_buffer_size ); send_buffer[ 0 ] = record.msg_type; memcpy( send_buffer + 1, &record.length, 3 ); memcpy( send_buffer + 4, message, message_len ); response = send_message( connection, content_handshake, send_buffer, send_buffer_size ); free( send_buffer ); return response; }

This would be a bit simpler except that, for some strange reason, the TLS designers mandated that the length of the handshake message must be given in a 24-bit field, which no compiler that I'm aware of can generate. Of course, on a big-endian machine, this wouldn't be a problem; just truncate the high-order byte of a 32-bit integer and you'd have a 24-bit integer. Unfortunately, most general purpose computers these days are little-endian, so it's necessary to convert it and then truncate it.

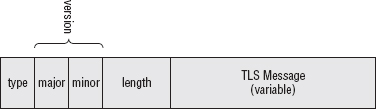

But send_handshake_message still doesn't call send! TLS mandates not only that every handshake message be prepended with a header indicating its type and length, but that every message, including the already-prepended handshake messages, be prepended with yet another header indicating its type and length!

So, finally, define yet another header structure and some supporting enumerations in Listing 6-16.

Listing 6-16: "tls.h" TLSPlaintext header

/** This lists the type of higher-level TLS protocols that are defined */

typedef enum {

content_change_cipher_spec = 20,

content_alert = 21,

content_handshake = 22,

content_application_data = 23

}

ContentType;

typedef enum { warning = 1, fatal = 2 } AlertLevel;

/**

* Enumerate all of the error conditions specified by TLS.

*/ typedef enum { close_notify = 0, unexpected_message = 10, bad_record_mac = 20, decryption_failed = 21, record_overflow = 22, decompression_failure = 30, handshake_failure = 40, bad_certificate = 42, unsupported_certificate = 43, certificate_revoked = 44, certificate_expired = 45, certificate_unknown = 46, illegal_parameter = 47, unknown_ca = 48, access_denied = 49, decode_error = 50, decrypt_error = 51, export_restriction = 60, protocol_version = 70, insufficient_security = 71, internal_error = 80, user_canceled = 90, no_renegotiation = 100 } AlertDescription; typedef struct { unsigned char level; unsigned char description; } Alert; /** * Each packet to be encrypted is first inserted into one of these structures. */ typedef struct { unsigned char type; ProtocolVersion version; unsigned short length; } TLSPlaintext;

There are four types of TLS messages defined: handshake messages, alerts, data, and "change cipher spec," which is technically a handshake message, but is broken out for specific implementation types that are examined later. Also, the protocol version is included on every packet.

The TLS Message header is illustrated in Figure 6-4.

Figure 6-4: TLS Message header

Notice that this header is added to every packet that is sent over a TLS connection, not just the handshake messages. If, after handshake negotiation, either side receives a packet whose first byte is not greater than or equal to 20 and less than or equal to 23 then something has gone wrong, and the whole connection should be terminated.

Finally, you need one last send function that prepends this header on top of the handshake message as shown in Listing 6-17.

Listing 6-17: "tls.c" send_message

static int send_message( int connection,

int content_type,

const unsigned char *content,

short content_len )

{

TLSPlaintext header;

unsigned char *send_buffer;

int send_buffer_size;

send_buffer_size = content_len;

send_buffer_size +=5;

send_buffer = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( send_buffer_size );

header.type = content_type;

header.version.major = TLS_VERSION_MAJOR;

header.version.minor = TLS_VERSION_MINOR;

header.length = htons( content_len );

send_buffer[ 0 ] = header.type;

send_buffer[ 1 ] = header.version.major;

send_buffer[ 2 ] = header.version.minor;

memcpy( send_buffer + 3, &header.length, sizeof( short ) );

memcpy( send_buffer + 5, content, content_len );

if ( send( connection, ( void * ) send_buffer, send_buffer_size, 0 ) < send_buffer_size ) { return −1; } free( send_buffer ); return 0; }

At this point, the actual socket-level send function is called. Now the client hello message, with its handshake message header, with its TLS header, are sent to the server for processing. After all of this prepending, the final wire-level structure is as shown in Figure 6-5.

Figure 6-5: TLS Client Hello with all headers

TLS Server Hello

The server should now select one of the supported cipher suites and respond with a server hello response. The client is required to block, waiting for an answer; nothing else can happen on this socket until the server responds. Expand tls_connect:

// Step 2. Receive the server hello response

if ( receive_tls_msg( connection, parameters ) < 0 )

{

perror( "Unable to receive server hello" );

return 2;

}

The function receive_tls_msg, as you can probably imagine, is responsible for reading a packet off the socket, stripping off the TLS header, stripping off the handshake header if the message is a handshake message, and processing the message itself. This is shown in Listing 6-18.

Listing 6-18: "tls.c" receive_tls_msg

/**

* Read a TLS packet off of the connection (assuming there's one waiting)

* and try to update the security parameters based on the type of message

* received. If the read times out, or if an alert is received, return an error

* code; return 0 on success.

* TODO - assert that the message received is of the type expected (for example,

* if a server hello is expected but not received, this is a fatal error per

* section 7.3).

* returns −1 if an error occurred (this routine will have sent an

* appropriate alert). Otherwise, return the number of bytes read if the packet

* includes application data; 0 if the packet was a handshake. −1 also

* indicates that an alert was received.

*/

static int receive_tls_msg( int connection,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

TLSPlaintext message;

unsigned char *read_pos, *msg_buf;

unsigned char header[ 5 ]; // size of TLSPlaintext

int bytes_read, accum_bytes;

// STEP 1 - read off the TLS Record layer

if ( recv( connection, header, 5, 0 ) <= 0 )

{

// No data available; it's up to the caller whether this is an error or not.

return −1;

}

message.type = header[ 0 ];

message.version.major = header[ 1 ];

message.version.minor = header[ 2 ];

memcpy( &message.length, header + 3, 2 );

message.length = htons( message.length );

Adding a Receive Loop

First, the TLSPlaintext header is read from the connection and validated. The error handling here leaves a bit to be desired, but ignore that for the time being. If everything goes correctly, message.length holds the number of bytes remaining in the current message. Because TCP doesn't guarantee that all bytes are available right away, it's necessary to enter a receive loop in Listing 6-19:

Listing 6-19: "tls.c" receive_tls_msg (continued in Listing 6-21)

msg_buf = ( char * ) malloc( message.length ); // keep looping & appending until all bytes are accounted for accum_bytes = 0; while ( accum_bytes < message.length ) { if ( ( bytes_read = recv( connection, ( void * ) msg_buf, message.length - accum_bytes, 0 ) ) <= 0 ) { int status; perror( "While reading a TLS packet" ); if ( ( status = send_alert_message( connection, illegal_parameter ) ) ) { free( msg_buf ); return status; } return −1; } accum_bytes += bytes_read; msg_buf += bytes_read; }

This loop, as presented here, is vulnerable to a denial of service attack. If the server announces that 100 bytes are available but never sends them, the client hangs forever waiting for these bytes. There's not much you can do about this, though. You can (and should) set a socket-level timeout, but if it expires, there's not much point in continuing the connection.

Sending Alerts

Notice that if recv returns an error, a function send_alert_message is invoked. Remember the four types of TLS messages? Alert was one of them. This is how clients and servers notify each other of unexpected conditions. In theory, an alert can be recoverable — expired certificate is defined as an alert, for example — but this poses a problem for the writer of a general-purpose TLS implementation. If the client tells the server that its certificate has expired then in theory the server could present a new certificate that hadn't expired. But why did it send an expired certificate in the first place, if it had one that was current? In general, all alerts are treated as fatal errors.

Alerts are also frustratingly terse. As you can see, if the client wasn't able to receive the entire message, it just returns an illegal parameter with no further context. Although it logs a more detailed reason, the server developer probably doesn't have access to those logs and has no clue what he did wrong. It would certainly be nice if the TLS alert protocol allowed space for a descriptive error message.

send_alert_message is shown in Listing 6-20.

Listing 6-20: "tls.c" send_alert_message

static int send_alert_message( int connection,

int alert_code )

{

char buffer[ 2 ];

// TODO support warnings

buffer[ 0 ] = fatal;

buffer[ 1 ] = alert_code;

return send_message( connection, content_alert, buffer, 2 );

}

By reusing the send_message routine from above, sending an alert message is extremely simple.

Parsing the Server Hello Structure

Assuming nothing went wrong, the message has now been completely read from the connection and is contained in msg_buf. For the moment, the only type of message you're interested in is content_handshake, whose parsing is shown in Listing 6-21:

Listing 6-21: "tls.c" receive_tls_msg (continued from Listing 6-19)

read_pos = msg_buf;

if ( message.type == content_handshake )

{

Handshake handshake;

// Now, read the handshake type and length of the next packet

// TODO - this fails if the read, above, only got part of the message

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &handshake.msg_type,

( void * ) read_pos, 1 );

handshake.length = read_pos[ 0 ] << 16 | read_pos[ 1 ] << 8 | read_pos[ 2 ];

read_pos += 3;

// TODO check for negative or unreasonably long length

// Now, depending on the type, read in and process the packet itself.

switch ( handshake.msg_type )

{

// Client-side messages

case server_hello:

read_pos = parse_server_hello( read_pos, handshake.length, parameters ); if ( read_pos == NULL ) /* error occurred */ { free( msg_buf ); send_alert_message( connection, illegal_parameter ); return −1; } break; default: printf( "Ignoring unrecognized handshake message %d\n", handshake.msg_type ); // Silently ignore any unrecognized types per section 6 // TODO However, out-of-order messages should result in a fatal alert // per section 7.4 read_pos += handshake.length; break; } } else { // Ignore content types not understood, per section 6 of the RFC. printf( "Ignoring non-recognized content type %d\n", message.type ); } free( msg_buf ); return message.length; }

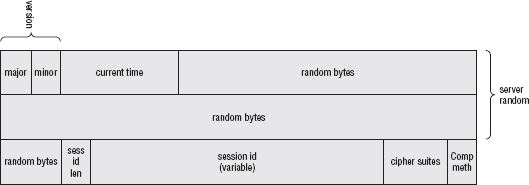

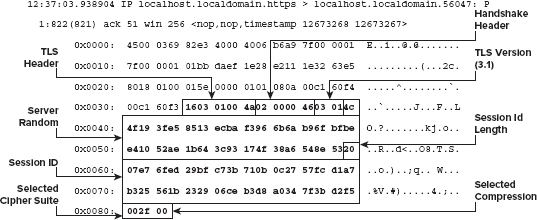

As I'm sure you can imagine, you fill this out quite a bit more throughout this chapter. For now, though, just focus on the parse_server_hello function. The Server Hello message is illustrated in Figure 6-6.

Figure 6-6: Server Hello structure

As with the client hello, go ahead and define a structure to hold its value in Listing 6-22.

Listing 6-22: "tls.h" ServerHello structure

typedef struct { ProtocolVersion server_version; Random random; unsigned char session_id_length; unsigned char session_id[ 32 ]; // technically, this len should be dynamic. unsigned short cipher_suite; unsigned char compression_method; } ServerHello;

Because the TLSParameters were passed into the receive_tls_message function, the parse_server_hello can go ahead and update the ongoing state as it's parsed, as in Listing 6-23.

Listing 6-23: "tls.c" parse_server_hello

static char *parse_server_hello( char *read_pos,

int pdu_length,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

ServerHello hello;

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &hello.server_version.major,

( void * ) read_pos, 1 );

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &hello.server_version.minor,

( void * ) read_pos, 1 );

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &hello.random.gmt_unix_time,

( void * ) read_pos, 4 );

// *DON'T* put this in host order, since it's not used as a time! Just

// accept it as is

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) hello.random.random_bytes,

( void * ) read_pos, 28 );

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &hello.session_id_length,

( void * ) read_pos, 1 );

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) hello.session_id,

( void * ) read_pos, hello.session_id_length );

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &hello.cipher_suite,

( void * ) read_pos, 2 );

hello.cipher_suite = ntohs( hello.cipher_suite );

// TODO check that these values were actually in the client hello

// list.

parameters->pending_recv_parameters.suite = hello.cipher_suite;

parameters->pending_send_parameters.suite = hello.cipher_suite;

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &hello.compression_method,

( void * ) read_pos, 1 );

if ( hello.compression_method != 0 )

{ fprintf( stderr, "Error, server wants compression.\n" ); return NULL; } // TODO - abort if there's more data here than in the spec (per section // 7.4.1.2, forward compatibility note) // TODO - abort if version < 3.1 with "protocol_version" alert error // 28 random bytes, but the preceding four bytes are the reported GMT unix // time memcpy( ( void * ) parameters->server_random, &hello.random.gmt_unix_time, 4 ); memcpy( ( void * ) ( parameters->server_random + 4 ), ( void * ) hello.random.random_bytes, 28 ); return read_pos; }

Note that if the server asked for compression, this function returns null because this implementation doesn't support compression. This is recognized by the calling routine and is used to generate an alert. Here the terseness of the TLS alert protocol shows. If the server asked for compression, it just gets back a nondescript illegal parameter but receives no indication of which parameter was illegal. It certainly would be more robust if you were allowed to tell it which parameter you were complaining about. This is generally not a problem for users of TLS software — if you get an illegal parameter while using, say, a browser, that means that the programmer of the browser did something wrong — but is a hassle when developing/testing TLS software like the library developed in this book. When developing, therefore, it's best to test against a client or server with its debug levels set to maximum so that if you do get back an illegal parameter (or any other nondescript alert message), you can go look at the server logs to see what you actually did wrong.

This routine stores the server random, of course, because it is needed later on in the master secret computation. Primarily, though, it sets the values pending_send_parameters and pending_recv_parameters with the selected suite. Expand the definition of ProtectionParameters to keep track of this in Listing 6-24.

Listing 6-24: "tls.h" ProtectionParameters with cipher suite

typedef struct

{

unsigned char *MAC_secret;

unsigned char *key;

unsigned char *IV;

CipherSuiteIdentifier suite;

}

ProtectionParameters;

Recall that CipherSuiteIdentifier was defined as part of the client hello.

parse_server_hello is something of the opposite of send_client_hello and it even makes use of a function complementary to append_buffer, shown in Listing 6-25.

Listing 6-25: "tls.c" read_buffer

static char *read_buffer( char *dest, char *src, size_t n )

{

memcpy( dest, src, n );

return src + n;

}

Reporting Server Alerts

What if the server doesn't happen to support TLS_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA (or any of the cipher suites on the list the client sends)? It doesn't return a server_hello at all; instead it responds with an alert message. You need to be prepared to deal with alerts at any time, so extend receive_tls_message to handle alerts as shown in Listing 6-26.

Listing 6-26: "receive_tls_message" with alert support

static int receive_tls_msg( int connection,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

if ( message.type == content_handshake )

{

...

}

else if ( message.type == content_alert )

{

while ( ( read_pos - decrypted_message ) < decrypted_length )

{

Alert alert;

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &alert.level,

( void * ) read_pos, 1 );

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &alert.description,

( void * ) read_pos, 1 );

report_alert( &alert );

if ( alert.level == fatal )

{

return −1;

}

}

}

Notice that alert level is checked. If the server specifically marks an alert as a fatal, the handshake is aborted; otherwise, the handshake process continues. Effectively this means that this implementation is ignoring warnings, which is technically a Bad Thing. However, as noted previously, there's really not much that can be done about the few alerts defined as warnings anyway. In any case, the alert itself is written to stdout via the helper function report_alert in Listing 6-27.

Listing 6-27: "tls.c" report_alert

static void report_alert( Alert *alert )

{

printf( "Alert - " );

switch ( alert->level )

{

case warning:

printf( "Warning: " );

break;

case fatal:

printf( "Fatal: " );

break;

default:

printf( "UNKNOWN ALERT TYPE %d (!!!): ", alert->level );

break;

}

switch ( alert->description )

{

case close_notify:

printf( "Close notify\n" );

break;

case unexpected_message:

printf( "Unexpected message\n" );

break;

case bad_record_mac:

printf( "Bad Record Mac\n" );

break;

...

default:

printf( "UNKNOWN ALERT DESCRIPTION %d (!!!)\n", alert->description );

break;

}

TLS Certificate

According to the handshake protocol, the next message after the server hello ought to be the certificate that both identifies the server and provides a public key for key exchange. The client, then, should accept the server hello and immediately start waiting for the certificate message that follows.

The designers of TLS recognized that it is somewhat wasteful to rigidly separate messages this way, so the TLS format actually allows either side to concatenate multiple handshake messages within a single TLS message. This capability was one of the big benefits of TLS over SSLv2. Remember the TLS header that included a message length which was then followed by the seemingly superfluous handshake header that included essentially the same length? This is why it was done this way; a single TLS header can identify multiple handshake messages, each with its own independent length. Most TLS implementations do take advantage of this optimization, so you must be prepared to handle it.

This slightly complicates the design of receive_tls_msg, though. The client must now be prepared to process multiple handshake messages within a single TLS message. Modify the content_handshake handler to keep processing the TLS message until there are no more handshake messages remaining as in Listing 6-28.

Listing 6-28: "tls.c" receive_tls_msg with multiple handshake support

if ( message.type == content_handshake )

{

while ( ( read_pos - decrypted_message ) < decrypted_length )

{

Handshake handshake;

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &handshake.msg_type,

( void * ) read_pos, 1 );

...

switch ( handshake.msg_type )

{

...

case certificate:

read_pos = parse_x509_chain( read_pos, handshake.length,

¶meters->server_public_key );

if ( read_pos == NULL )

{

printf( "Rejected, bad certificate\n" );

send_alert_message( connection, bad_certificate );

return −1;

}

break;

Notice that the call is made, not directly to the parse_x509_certificate function developed in Chapter 5, but to a new function parse_x509_chain. TLS actually allows the server to pass in not just its own certificate, but the signing certificate of its certificate, and the signing certificate of that certificate, and so on, until a top-level, self-signed certificate is reached. It's up to the client to determine whether or not it trusts the top-level certificate. Of course, each certificate after the first should be checked to ensure that it includes the "is a certificate authority" extension described in Chapter 5 as well.

Therefore, the TLS certificate handshake message starts off with the length of the certificate chain so that the receiver knows how many bytes of certificate follow. If you are so inclined, you can infer this from the length of the handshake message and the ASN.1 structure declaration that begins each certificate, but explicitness can never hurt.

Certificate chain parsing, then, consists of reading the length of the certificate chain from the message, and then reading each certificate in turn, using each to verify the last. Of course, the first must also be verified for freshness and domain name validity. At a bare minimum, though, in order to complete a TLS handshake, you need to read and store the public key contained within the certificate because it's required to perform the key exchange. Listing 6-29 shows a bare-bones certificate chain parsing routine that doesn't actually verify the certificate signatures or check validity parameters.

Listing 6-29: "x509.c" parse_x509_chain

/**

* This is called by "receive_server_hello" when the "certificate" PDU

* is encountered. The input to this function should be a certificate chain.

* The most important certificate is the first one, since this contains the

* public key of the subject as well as the DNS name information (which

* has to be verified against).

* Each subsequent certificate acts as a signer for the previous certificate.

* Each signature is verified by this function.

* The public key of the first certificate in the chain will be returned in

* "server_public_key" (subsequent certificates are just needed for signature

* verification).

* TODO verify signatures.

*/

char *parse_x509_chain( unsigned char *buffer,

int pdu_length,

public_key_info *server_public_key )

{

int pos;

signed_x509_certificate certificate;

unsigned int chain_length, certificate_length;

unsigned char *ptr;

ptr = buffer;

pos = 0;

// TODO this won't work on a big-endian machine

chain_length = ( *ptr << 16 ) | ( *( ptr + 1 ) << 8 ) | ( *( ptr + 2 ) );

ptr += 3;

// The chain length is actually redundant since the length of the PDU has

// already been input.

assert ( chain_length == ( pdu_length - 3 ) );

while ( ( ptr - buffer ) < pdu_length ) { // TODO this won't work on a big-endian machine certificate_length = ( *ptr << 16 ) | ( *( ptr + 1 ) << 8 ) | ( *( ptr + 2 ) ); ptr += 3; init_x509_certificate( &certificate ); parse_x509_certificate( ( void * ) ptr, certificate_length, &certificate ); if ( !pos++ ) { server_public_key->algorithm = certificate.tbsCertificate.subjectPublicKeyInfo.algorithm; switch ( server_public_key->algorithm ) { case rsa: server_public_key->rsa_public_key.modulus = ( huge * ) malloc( sizeof( huge ) ); server_public_key->rsa_public_key.exponent = ( huge * ) malloc( sizeof( huge ) ); set_huge( server_public_key->rsa_public_key.modulus, 0 ); set_huge( server_public_key->rsa_public_key.exponent, 0 ); copy_huge( server_public_key-> rsa_public_key.modulus, certificate.tbsCertificate.subjectPublicKeyInfo. rsa_public_key.modulus ); copy_huge( server_public_key-> rsa_public_key.exponent, certificate.tbsCertificate.subjectPublicKeyInfo. rsa_public_key.exponent ); break; default: break; } } ptr += certificate_length; // TODO compute the hash of the certificate so that it can be validated by // the next one free_x509_certificate( &certificate ); } return ptr; }

This blindly accepts whatever certificate is presented by the server. It doesn't check the domain name parameter of the subject name, doesn't check to see that it's signed by a trusted certificate authority, and doesn't even verify that the validity period of the certificate contains the current date. Clearly, an industrial-strength TLS implementation needs to do at least all of these things.

TLS Server Hello Done

After the certificate the server should send a hello done message — at least that's what happens in the most common type of TLS handshake being examined here. This indicates that the server will not send any more unencrypted handshake messages on this connection.

This may seem surprising, but if you think about it, there's nothing more for the server to do. It has chosen a cipher suite acceptable to the client and provided enough information — the public key — to complete a key exchange in that cipher suite. It's incumbent on the client to now come up with a key and exchange it. Parsing the server hello done message is trivial, as in Listing 6-30.

Listing 6-30: "tls.c" receive_tls_message with server hello done support

switch ( handshake.msg_type )

{

...

case server_hello_done:

parameters->server_hello_done = 1;

break;

As you can see, there's really nothing there; the server hello done message is just a marker and contains no data. Note that this will almost definitely be piggy-backed onto a longer message that contains the server hello and the server certificate.

This routine just sets a flag indicating that the server hello done message has been received. Add this flag to TLSParameters as shown in Listing 6-31; it's used internally to track the state of the handshake.

Listing 6-31: "tls.h" TLSParameters with state tracking included

typedef struct

{

...

int server_hello_done;

}

TLSParameters;

Finally, recall that this whole process was being controlled by tls_connect. It sent a client hello message and then received the server hello. Due to piggy-backing of handshake messages, though, that call to receive probably picked up all three expected messages and processed them, culminating in the setting of server_hello_done. This isn't guaranteed, though; the server could legitimately split these up into three separate messages (the server you develop in the next chapter does this, in fact). To handle either case, modify tls_connect to keep receiving TLS messages until server_hello_done is set, as in Listing 6-32.

Listing 6-32: "tls.c" tls_connect multiple handshake messages

// Step 2. Receive the server hello response (will also have gotten

// the server certificate along the way)

parameters->server_hello_done = 0;

while ( !parameters->server_hello_done )

{

if ( receive_tls_msg( connection, parameters ) < 0 )

{

perror( "Unable to receive server hello" );

return 2;

}

}

TLS Client Key Exchange

Now it's time for the client to do a key exchange, which is the most critical part of the whole TLS handshake. You might reasonably expect that if RSA is used as a key exchange method then the client selects a set of keys, encrypts them, and sends them on. If DH was used as a key exchange method, both sides would agree on Z and that would be used as the key. As it turns out, however, TLS mandates a bit more complexity here; the key exchange is used to exchange a premaster secret, which is expanded using a pseudo-random function into a master secret which is used for keying material. This procedure guards against weaknesses in the client's key generation routines.

Sharing Secrets Using TLS PRF (Pseudo-Random Function)

In several places during the TLS negotiation, the algorithm calls for a lot of data to be generated deterministically so that both sides agree on the same result, based on a seed. This process is referred to as pseudo-random, just like the software pseudo-random generator that's built into every C implementation. TLS has a fairly complex pseudo-random function called the PRF that generates data from a seed in such a way that two compliant implementations, given the same seed data, generate the same data, but that the output is randomly distributed and follows no observable pattern.

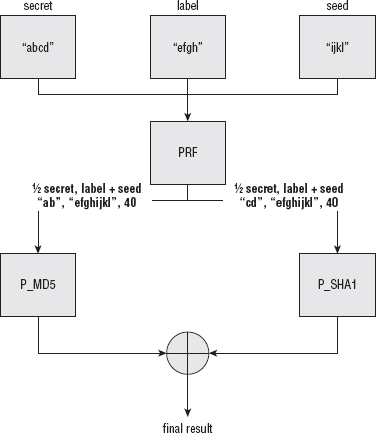

It should come as no surprise at this point that this pseudo-random function is based on secure hash algorithms, which deterministically generate output from input in a non-predictable way. TLS's PRF is actually based on the HMAC algorithm. It takes as input three values: the seed, a label, and a secret. The seed and the label are both used as input to the HMAC algorithm.

The PRF for TLS v1.0 involves both MD5 and SHA-1 (and the use of these specific hash algorithms is hard-coded into the specification). MD5 and SHA-1 are each used, along with the HMAC algorithm specified in Chapter 4, to generate an arbitrary quantity of output independently. Then the results of both the MD5 HMAC and the SHA HMAC are XORed together to produce the final result. The secret is split up so that the MD5 routine gets the first half and the SHA routine gets the second half:

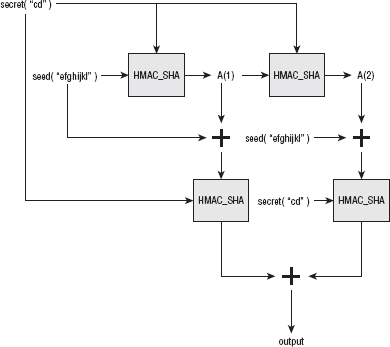

Consider using the triple ("abcd", "efgh", "ijkl" ) to generate 40 bytes of output through the PRF as shown in Figure 6-7.

Figure 6-7: TLS's pseudo-random function

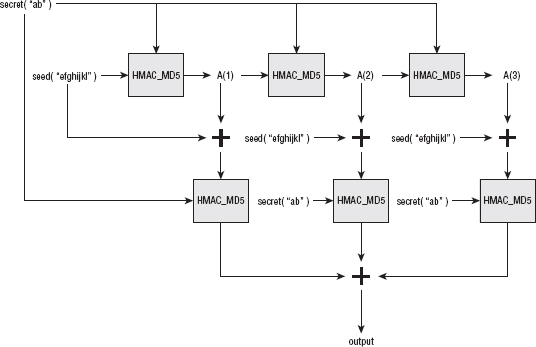

So what are these P_MD5 and P_SHA1 blocks that are XORed together to produce the final result? Well, if you recall from Chapter 4, MD5 produces 16 bytes of output, regardless of input length, and SHA-1 produces 20. If you want to produce an arbitrary amount of data based on the secret, the label, and the seed using these hashing algorithms, you have to call them more than once. Of course, you have to call them with different data each time, otherwise you get the same 16 bytes back each time. P_[MD5|SHA1] actually use the HMAC algorithm, again, to produce the input to the final HMAC algorithm. So what goes into the HMAC algorithms that go into the HMAC algorithms? More HMAC output, of course! The seed is HMAC'ed once to produce the HMAC input for the first n bytes (where n is 16 or 20 depending on the algorithm), and then that is HMAC'ed again to produce the input for the next n bytes.

All of this sounds almost self-referential, but it actually does work. Figure 6-8 shows the P_MD5 algorithm, illustrated out to three iterations (to produce 48 = 16 * 3 bytes of output).

So, given a secret of "ab" and a seed of "efghijkl", A(1) is HMAC_MD5("ab", "efghijkl"), or 0xefe3a7027ddbdb424cabd0935bfb3898. A(2), then, is HMAC_MD5( "ab", 0xefe3a7027ddbdb424cabd0935bfb3898), or 0xda55f448c81b 93ce1231cb7668bee2a2. Because you need 40 bytes of output, and MD5 only produces 16 per iteration, you need to iterate three times to produce 48 bytes and throw away the last 8. This means that you need A(3) as well, which is HMAC_MD5( "ab", A(2) = 0xda55f448c81b93ce1231cb7668bee2a2), or 0xbfa8ec7eda156ec26478851358c7a1fa.

With all the As computed, you now have enough information to feed into the "real" HMAC operations that generate the requisite 48 bytes of output. The final 48 bytes of output (remembering that you discard the last 8) are

HMAC( "ab", A(1) . "efghijkl" ) . HMAC( "ab", A(2) . "efghijkl" ) . HMAC( "ab", A(3), "efghijkl" )

Notice that the secret and the seed are constant throughout each HMAC operation; the only difference in each are the A values. These operations produce the 48 output bytes:

0x1b6ca10d18faddfbeb92b2d95f55ce2607d6c81ebe4b96d 1bec81813b9a0275725564781eda73ac521548d7d1f982c17

P_SHA1 is identical. It just replaces the SHA-1 hash algorithm with the MD5 hash algorithm. Because SHA-1 produces 20 bytes of output per iteration, though, it's only necessary to iterate twice and none of the output is discarded. P_SHA is fed the exact same seed, but only the last half of the secret, as diagrammed in Figure 6-9.

This produces the 40 bytes:

0xcbb3de5db9295cdb68eb1ab18f88939cb3146849fe167cf8f9ec5f131790005d7f27b 2515db6c590

Finally, these two results are XORed together to produce the 40-byte pseudo-random combination:

0xd0df7f50a1d381208379a868d0dd5dbab4c2a057405dea2947244700ae30270 a5a71f5d0b011ff55

Notice that there's no predictable repetition here, and no obvious correlation with the input data. This procedure can be performed to produce any arbitrarily large amount of random data that two compliant implementations, both of which share the secret, can reproduce consistently.

In code, this is shown in Listing 6-33.

Listing 6-33: "prf.c" PRF function

/**

* P_MD5 or P_SHA, depending on the value of the "new_digest" function

* pointer.

* HMAC_hash( secret, A(1) + seed ) + HMAC_hash( secret, A(2) + seed ) + ...

* where + indicates concatenation and A(0) = seed, A(i) =

* HMAC_hash( secret, A(i - 1) )

*/

static void P_hash( const unsigned char *secret,

int secret_len,

const unsigned char *seed,

int seed_len,

unsigned char *output,

int out_len,

void (*new_digest)( digest_ctx *context ) )

{

unsigned char *A;

int hash_len; // length of the hash code in bytes

digest_ctx A_ctx, h;

int adv;

int i;

new_digest( &A_ctx );

hmac( secret, secret_len, seed, seed_len, &A_ctx );

hash_len = A_ctx.hash_len * sizeof( int );

A = malloc( hash_len + seed_len );

memcpy( A, A_ctx.hash, hash_len );

memcpy( A + hash_len, seed, seed_len );

i = 2;

while ( out_len > 0 )

{

new_digest( &h );

// HMAC_Hash( secret, A(i) + seed )

hmac( secret, secret_len, A, hash_len + seed_len, &h );

adv = ( h.hash_len * sizeof( int ) ) < out_len ?

h.hash_len * sizeof( int ) : out_len;

memcpy( output, h.hash, adv );

out_len -= adv;

output += adv;

// Set A for next iteration

// A(i) = HMAC_hash( secret, A(i-1) )

new_digest( &A_ctx );

hmac( secret, secret_len, A, hash_len, &A_ctx );

memcpy( A, A_ctx.hash, hash_len );

} free( A ); } /** * P_MD5( S1, label + seed ) XOR P_SHA1(S2, label + seed ); * where S1 & S2 are the first & last half of secret * and label is an ASCII string. Ignore the null terminator. * * output must already be allocated. */ void PRF( const unsigned char *secret, int secret_len, const unsigned char *label, int label_len, const unsigned char *seed, int seed_len, unsigned char *output, int out_len ) { int i; int half_secret_len; unsigned char *sha1_out = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( out_len ); unsigned char *concat = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( label_len + seed_len ); memcpy( concat, label, label_len ); memcpy( concat + label_len, seed, seed_len ); half_secret_len = ( secret_len / 2 ) + ( secret_len % 2 ); P_hash( secret, half_secret_len, concat, ( label_len + seed_len ), output, out_len, new_md5_digest ); P_hash( secret + ( secret_len / 2 ), half_secret_len, concat, ( label_len + seed_len ), sha1_out, out_len, new_sha1_digest ); for ( i = 0; i < out_len; i++ ) { output[ i ] ^= sha1_out[ i ]; } free( sha1_out ); free( concat ); }

To see the PRF in action, put together a short test main routine in Listing 6-34.

{ unsigned char *output; int out_len, i; int secret_len; int label_len; int seed_len; unsigned char *secret; unsigned char *label; unsigned char *seed; if ( argc < 5 ) { fprintf( stderr, "usage: %s [0x]<secret> [0x]<label> [0x]<seed> <output len>\n", argv[ 0 ] ); exit( 0 ); } secret_len = hex_decode( argv[ 1 ], &secret ); label_len = hex_decode( argv[ 2 ], &label ); seed_len = hex_decode( argv[ 3 ], &seed ); out_len = atoi( argv[ 4 ] ); output = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( out_len ); PRF( secret, secret_len, label, label_len, seed, seed_len, output, out_len ); for ( i = 0; i < out_len; i++ ) { printf( "%.02x", output[ i ] ); } printf( "\n" ); free( secret ); free( label ); free( seed ); free( output ); return 0; } #endif

You can try out the PRF, although it's not earth-shatteringly interesting:

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./prf secret label seed 20 b5baf4722b91851a8816d22ebd8c1d8cc2e94d55

Creating Reproducible, Unpredictable Symmetric Keys with Master Secret Computation

The client selects the premaster secret and sends it to the server (or agrees on it, in the case of DH key exchange). The premaster secret is, as the name implies, secret — in fact, it's really the only important bit of handshake material that's hidden from eavesdroppers. However, the premaster secret itself isn't used as a session key; this would open the door to replay attacks. The premaster secret is combined with the server random and client random values exchanged earlier in the handshake and then run through the PRF to generate the master secret, which is used, indirectly, as the keying material for the symmetric encryption algorithms and MACs that actually protect the data in transit.

Given, for example, a premaster secret

030102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f101112131415161718191a1b1c1d1e 1f202122232425262728292a2b2c2d2e2f

a client random

4af0a38100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

and a server random

4af0a3818ff72033b852b9b9c09e7d8045ab270eabc74e11d565ece018c9a5ec

you would compute the final master secret from which the actual keys are derived using — you guessed it — the PRF.

Remember that the PRF takes three parameters: a secret, a label, and a seed. The premaster secret is the secret, the label is just the unimaginative text string "master secret", and the seed is the client random and the server random concatenated one after the other, client random first.

The PRF is the XOR of the SHA-1 and the MD5 HMACs of the secret and the label concatenated with the seed, expanded out iteratively. With the PRF function defined above, master secret expansion is actually simple to code, as in Listing 6-35.

Listing 6-35: "tls.c" master secret computation

/**

* Turn the premaster secret into an actual master secret (the

* server side will do this concurrently) as specified in section 8.1:

* master_secret = PRF( pre_master_secret, "master secret",

* ClientHello.random + ServerHello.random );

* ( premaster_secret, parameters );

* Note that, with DH, the master secret len is determined by the generator (p)

* value.

*/

static void compute_master_secret( const unsigned char *premaster_secret,

int premaster_secret_len,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{ const char *label = "master secret"; PRF( premaster_secret, premaster_secret_len, label, strlen( label ), // Note - cheating, since client_random & server_random are defined // sequentially in the structure parameters->client_random, RANDOM_LENGTH * 2, parameters->master_secret, MASTER_SECRET_LENGTH ); }

RSA Key Exchange

After the server hello done has been received, the server believes that the client has enough information to complete the key exchange specified in the selected cipher suite. If the key exchange is RSA, this means that the client now has the server's public key. It's the client's problem whether to trust that key or not, based on the certificate chain.

The client should thus send a key exchange as shown in Listing 6-36, in tls_connect.

Listing 6-36: "tls.c" tls_connect with key exchange

// Step 3. Send client key exchange, change cipher spec (7.1) and encrypted

// handshake message

if ( !( send_client_key_exchange( connection, parameters ) ) )

{

perror( "Unable to send client key exchange" );

return 3;

}

send_client_key_exchange is slightly complex because RSA and DH key exchanges are so different. For now, just focus on RSA in Listing 6-37.

Listing 6-37: "tls.c" send_client_key_exchange

/**

* Send the client key exchange message, as detailed in section 7.4.7

* Use the server's public key (if it has one) to encrypt a key. (or DH?)

* Return true if this succeeded, false otherwise.

*/

static int send_client_key_exchange( int connection, TLSParameters *parameters )

{

unsigned char *key_exchange_message;

int key_exchange_message_len;

unsigned char *premaster_secret;

int premaster_secret_len;

switch ( parameters->pending_send_parameters.suite ) {

case TLS_NULL_WITH_NULL_NULL:

// XXX this is an error, exit here

break;

case TLS_RSA_WITH_NULL_MD5: case TLS_RSA_WITH_NULL_SHA: ... case TLS_RSA_WITH_DES_CBC_SHA: case TLS_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA: case TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA: case TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA: premaster_secret_len = MASTER_SECRET_LENGTH; premaster_secret = malloc( premaster_secret_len ); key_exchange_message_len = rsa_key_exchange( ¶meters->server_public_key.rsa_public_key, premaster_secret, &key_exchange_message ); break; default: return 0; } if ( send_handshake_message( connection, client_key_exchange, key_exchange_message, key_exchange_message_len ) ) { free( key_exchange_message ); return 0; } free( key_exchange_message ); // Now, turn the premaster secret into an actual master secret (the // server side will do this concurrently). compute_master_secret( premaster_secret, premaster_secret_len, parameters ); // XXX - for security, should also "purge" the premaster secret from // memory. calculate_keys( parameters ); free( premaster_secret ); return 1; }

The goal of the key exchange is to exchange a premaster secret, turn it into a master secret, and use that to calculate the keys that are used for the remainder of the connection. As you can see, send_client_key_exchange starts by checking if the key exchange method is RSA. If the key exchange method is RSA, send_client_key_exchange calls rsa_key_exchange to build the appropriate handshake message. compute_master_secret has already been examined in Listing 6-35, and calculate_keys is examined later in Listing 6-41.

This routine goes ahead and lets the rsa_key_exchange function select the premaster secret. There's no reason why send_client_key_exchange couldn't do this, and pass the premaster secret into rsa_key_exchange. However, this configuration makes DH key exchange easier to support because the upcoming dh_key_exchange necessarily has to select the premaster secret, due to the nature of the Diffie-Hellman algorithm.

The rsa_key_exchange message is built in Listing 6-38.

Listing 6-38: "tls.c" rsa_key_exchange

int rsa_key_exchange( rsa_key *public_key,

unsigned char *premaster_secret,

unsigned char **key_exchange_message )

{

int i;

unsigned char *encrypted_premaster_secret = NULL;

int encrypted_length;

// first two bytes are protocol version

premaster_secret[ 0 ] = TLS_VERSION_MAJOR;

premaster_secret[ 1 ] = TLS_VERSION_MINOR;

for ( i = 2; i < MASTER_SECRET_LENGTH; i++ )

{

// XXX SHOULD BE RANDOM!

premaster_secret[ i ] = i;

}

encrypted_length = rsa_encrypt( premaster_secret, MASTER_SECRET_LENGTH,

&encrypted_premaster_secret, public_key );

*key_exchange_message = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( encrypted_length + 2 );

(*key_exchange_message)[ 0 ] = 0;

(*key_exchange_message)[ 1 ] = encrypted_length;

memcpy( (*key_exchange_message) + 2, encrypted_premaster_secret,

encrypted_length );

free( encrypted_premaster_secret );

return encrypted_length + 2;

}

This function takes as input the RSA public key, generates a "random" premaster secret, encrypts it, and returns both the premaster secret and the key exchange message. The format of the key exchange message is straightforward; it's just a two-byte length followed by the PKCS #1 padded, RSA encrypted premaster secret. Notice that the specification mandates that the first two bytes of the premaster secret must be the TLS version — in this case, 3.1. In theory, the server is supposed to verify this. In practice, few servers do the verification because there are a few buggy TLS implementations floating around that they want to remain compatible with.

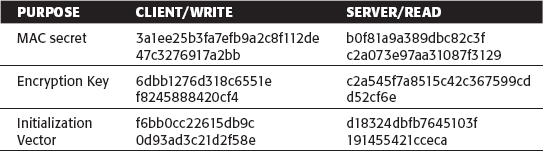

Now the only thing left to do is to turn the master secret into a set of keys. The amount, and even the type, of keying material needed depends on the cipher suite. If the cipher suite uses SHA-1 HMAC, the MAC requires a 20-byte key; if MD5, it requires a 16-byte key. If the cipher suite uses DES, it requires an 8-byte key; if AES-256, it requires a 32-byte key. If the encryption algorithm uses CBC, initialization vectors are needed; if the algorithm is a stream algorithm, no initialization vector is involved.

Rather than build an enormous switch/case statement for each possibility, define a CipherSuite structure as in Listing 6-39.

Listing 6-39: "tls.h" CipherSuite structure

typedef struct

{

CipherSuiteIdentifier id;

int block_size;

int IV_size;

int key_size;

int hash_size;

void (*bulk_encrypt)( const unsigned char *plaintext,

const int plaintext_len,

unsigned char ciphertext[],

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key );

void (*bulk_decrypt)( const unsigned char *ciphertext,

const int ciphertext_len,

unsigned char plaintext[],

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key );

void (*new_digest)( digest_ctx *context );

}

CipherSuite;

This includes everything you need to know about a cipher suite; by now, the utility of declaring the encrypt, decrypt, and hash functions with identical signatures in the previous chapters should be clear. Now, for each supported cipher suite, you need to generate a CipherSuite instance and index it as shown in Listing 6-40.

Listing 6-40: "tls.c" cipher suites list

static CipherSuite suites[] =

{

{ TLS_NULL_WITH_NULL_NULL, 0, 0, 0, 0, NULL, NULL, NULL },

{ TLS_RSA_WITH_NULL_MD5, 0, 0, 0, MD5_BYTE_SIZE, NULL, NULL, new_md5_digest },

{ TLS_RSA_WITH_NULL_SHA, 0, 0, 0, SHA1_BYTE_SIZE, NULL, NULL, new_sha1_digest },

{ TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_RC4_40_MD5, 0, 0, 5, MD5_BYTE_SIZE, rc4_40_encrypt,

rc4_40_decrypt, new_md5_digest }, { TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_MD5, 0, 0, 16, MD5_BYTE_SIZE, rc4_128_encrypt, rc4_128_decrypt, new_md5_digest }, { TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_SHA, 0, 0, 16, SHA1_BYTE_SIZE, rc4_128_encrypt, rc4_128_decrypt, new_sha1_digest }, { TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_RC2_CBC_40_MD5, 0, 0, 0, MD5_BYTE_SIZE, NULL, NULL, new_md5_digest }, { TLS_RSA_WITH_IDEA_CBC_SHA, 0, 0, 0, SHA1_BYTE_SIZE, NULL, NULL, new_sha1_digest }, { TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_DES40_CBC_SHA, 0, 0, 0, SHA1_BYTE_SIZE, NULL, NULL, new_sha1_digest }, { TLS_RSA_WITH_DES_CBC_SHA, 8, 8, 8, SHA1_BYTE_SIZE, des_encrypt, des_decrypt, new_sha1_digest }, { TLS_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA, 8, 8, 24, SHA1_BYTE_SIZE, des3_encrypt, des3_decrypt, new_sha1_digest }, ...

Because these instances are referred to by position, you have to list each one, even if it's not supported. Notice, for example, that TLS_RSA_WITH_IDEA_CBC_SHA is declared, but left empty. It is never used by this implementation, but by allocating space for it, the rest of the code is allowed to refer to elements in the CipherSuite structure by just referencing the suites array.

If you wanted to create a key for a 3DES cipher suite, for example, you could invoke

suites[ TLS_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA ].key_size

In fact, because the CipherSuiteIdentifier was added to ProtectionParameters, the key computation code can just invoke

suites[ parameters->suite ].key_size

when it needs to know how much keying material to retrieve from the master secret.