CHAPTER 9

Adding TLS 1.2 Support to Your TLS Library

TLS 1.2 was formally specified in 2008 after several years of debate. It represents a significant change to its predecessor TLS 1.1 — mostly in terms of increased security options and additional cipher suite choices. This chapter details the changes that you need to make to the TLS 1.0 implementation of the previous three chapters to make it compliant with TLS 1.2.

The next two sections detail the message-format level changes that TLS 1.2 introduced. I move quickly here, assuming a good familiarity with the material in the previous three chapters — if you don't remember what the PRF is or what messages are involved in the TLS handshake, you may want to jump back and briefly review at least Chapter 6. Alternatively, if you're more interested in what TLS 1.2 does, rather than how it does it, you can skip ahead to the section in the chapter on AEAD encryption.

Supporting TLS 1.2 When You Use RSA for the Key Exchange

This section covers changes sufficient enough to support TLS 1.2 in the most straightforward case: when RSA is used directly for key exchange. To do so, you would follow these basic steps.

- Obviously, you should change the version number declared in the header file from 3.1 to 3.3 as shown in Listing 9-1.

- After this, you need to make the code TLS 1.1 compliant. If you recall from Chapter 6, the most significant difference between TLS 1.0 and TLS 1.1 is that, for CBC-based block ciphers, TLS 1.1 prepends the IV to each block rather than computing it from the master secret. TLS 1.2 does this as well.

- You can go ahead and remove the IV calculation from the calculate_keys routine if you're so inclined. However, it's not really important that you do; for TLS 1.1+, computing an unused set of IVs just becomes a few wasted clock cycles.

- You do, however, have to modify send_message and tls_decrypt to prepend the IVs and recognize them, respectively.

The necessary changes to send_message are shown in Listing 9-2.

Listing 9-2: "tls.c" send_message with explicit IVs

// Finally, write the whole thing out as a single packet. if ( active_suite->bulk_encrypt ) { unsigned char *encrypted_buffer = malloc( send_buffer_size + active_suite->IV_size ); int plaintext_len; // TODO make this random memset( parameters->IV, '\0', active_suite->IV_size ); // The first 5 bytes (the header) and the IV aren't encrypted memcpy( encrypted_buffer, send_buffer, 5 ); memcpy( encrypted_buffer + 5, parameters->IV, active_suite->IV_size ); plaintext_len = 5 + active_suite->IV_size; active_suite->bulk_encrypt( send_buffer + 5, send_buffer_size - 5, encrypted_buffer + plaintext_len, parameters->IV, parameters->key ); free( send_buffer ); send_buffer = encrypted_buffer; send_buffer_size += active_suite->IV_size;As you can see, there's not much to change, here; just make sure to overwrite the IV with random bytes before encrypting, and put the IV in between the send buffer header and the encrypted data. You may wonder why you should keep the IV pointer in parameters at all given that the IV is being generated randomly each time a message is sent. Well, don't forget that the IV parameter was used as a generic state area for stream ciphers such as RC4 and needs to be kept intact, because RC4 looks just the same in TLS 1.1+ as it does in TLS 1.0.

- Listing 9-3 details the converse changes that you must make to tls_decrypt to properly decode buffers that are written this way.

Listing 9-3: "tls.c" tls_decrypt with explicit IVs

CipherSuite *active_suite = &( suites[ parameters->suite ] ); encrypted_length -= active_suite->IV_size; *decrypted_message = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( encrypted_length ); if ( active_suite->bulk_decrypt ) { if ( active_suite->IV_size ) { memcpy( parameters->IV, encrypted_message, active_suite->IV_size ); } active_suite->bulk_decrypt( encrypted_message + active_suite->IV_size, encrypted_length, *decrypted_message, parameters->IV, parameters->key );To decrypt, it's even easier; just check to see if the cipher suite calls for an IV, and, if so, copy the first IV_size bytes of the message into the parameters->IV.

If you change the TLS_MINOR_VERSION to 2, you actually now have a TLS 1.1-compliant implementation. You can probably easily see how this code could have been structured to allow the same function to service TLS 1.1 and TLS 1.0 with a handful of if statements. You might even want to try to do this as an exercise.

NOTE Note that this code makes no attempt at checking versions. If a client asks for version 3.1, it gets version 3.3, which is actually an error. To be properly compliant, the server should either negotiate the version requested by the client, or the highest version it supports. It can never negotiate a version higher than was requested.

TLS 1.2 Modifications to the PRF

The code in the previous section is still not TLS 1.2 compliant. TLS 1.2 made two significant structural changes to the message formats. The first was a change in the PRF.

Remember from Listing 6-33 that the TLS PRF defined a P_hash function that took as input a label and a seed, and securely generated an arbitrary number of bytes based on a hash function. In TLS 1.1 and earlier, this P_hash function was called twice; once with the hash function MD5, and once with the hash function SHA-1. The two calls each got half of the secret, and the outputs were XORed together to create the final output. Getting the PRF right is by far the most difficult part of implementing TLS.

If you're cringing in terror at what new horrors might await you with the complexity of TLS 1.2's modifications to the PRF, you'll be pleasantly surprised that TLS 1.2 actually simplifies the PRF. The P_hash function stays the same, but it's no longer a combination of two separate hash functions. You just call P_hash one time, give it the whole secret, and return the results directly as the output.

You may be wondering, of course, which hash function you should use if you're calling P_hash just one time. MD5 or SHA-1? Actually, TLS 1.2 makes this configurable; there's a new client hello extension that enables the client to suggest a hash function that should be used. If the client doesn't suggest one, though, both sides should default to SHA-256. Modify the PRF function from Listing 6-29 as shown in Listing 9-4.

Listing 9-4: "prf.c" PRF2

void PRF( const unsigned char *secret,

int secret_len,

const unsigned char *label,

int label_len,

const unsigned char *seed,

int seed_len,

unsigned char *output,

int out_len )

{

unsigned char *concat = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( label_len + seed_len );

memcpy( concat, label, label_len );

memcpy( concat + label_len, seed, seed_len );

P_hash( secret, secret_len, concat, label_len + seed_len, output,

out_len, new_sha256_digest );

free( concat );

}

As you can see, you almost don't need a PRF function anymore; you could just as easily change the callers to directly invoke P_hash because PRF isn't really adding any value anymore. Leaving it in place minimizes the changes to other code, though; everything else can stay just as it is.

TLS 1.2 Modifications to the Finished Messages Verify Data

You may recall from Listing 6-53 that there was one other data value that depended on the combination of an MD5 and an SHA-1 hash: the verify data in the finished message. And yes, sure enough, this changes in TLS 1.2 as well. Rather than tracking the MD5 and SHA-1 hashes of the handshake messages and then running those hashes through the PRF to generate the finished message, TLS 1.2 instead tracks a single hash; the same one that the PRF uses (the one negotiated in the client hello or the default SHA-256). It still hashes all handshake messages, and does so in the same way as TLS 1.1.

To support the TLS 1.2 finished message, follow these steps:

- Modify TLSParameters as shown in Listing 9-5 to keep track of an SHA-256 digest.

- Of course, the two digest updates in send_handshake_message and receive_tls_msg must be changed to update this digest as shown in Listing 9-6.

Listing 9-6: "tls.c" SHA-256 digest update

int send_handshake_message( int connection, int msg_type, const unsigned char *message, int message_len, TLSParameters *parameters ) { ... memcpy( send_buffer + 1, &record.length, 3 ); memcpy( send_buffer + 4, message, message_len ); update_digest( ¶meters->sha256_handshake_digest, send_buffer, send_buffer_size ); response = send_message( connection, content_handshake, send_buffer, send_buffer_size, ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); ... static int receive_tls_msg( int connection, char *buffer, - Finally, tls_resume and tls_connect must both be changed to initialize this digest rather than the two parallel digests that they initialized in Chapters 6 and 8. Listing 9-7 demonstrates.

Listing 9-7: "tls.c" TLS 1.2 handshake digest initialization

int tls_resume( int connection, int session_id_length, const unsigned char *session_id, const unsigned char *master_secret, TLSParameters *parameters ) { init_parameters( parameters, 0 ); parameters->connection_end = connection_end_client; parameters->session_id_length = session_id_length; memcpy( ¶meters->session_id, session_id, session_id_length ); new_sha256_digest( ¶meters->sha256_handshake_digest ); ... int tls_connect( int connection, TLSParameters *parameters, int renegotiate ) { init_parameters( parameters, renegotiate ); parameters->connection_end = connection_end_client; new_sha256_digest( ¶meters->sha256_handshake_digest ); ... int tls_accept( int connection, TLSParameters *parameters ) { init_parameters( parameters, 0 ); parameters->connection_end = connection_end_server; new_sha256_digest( ¶meters->sha256_handshake_digest ); ...

Of course, if you want to implement this code to support TLS 1.0 through TLS 1.2 concurrently, you'd have some conditional logic to initialize the handshake digests depending on the version of TLS.

Impact to Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange

As mentioned previously, the changes in the previous section are sufficient to support TLS 1.2 in the most straightforward case: when RSA is used directly for key exchange. However, there's one other significant structural change that was introduced by TLS 1.2 that impacts ephemeral Diffie-Hellman (DHE) key exchange suites. Recall that when DHE is used for key exchange the server must sign the DH parameters g, p, and Ys with the private key corresponding to the public key in the server's certificate. Prior to TLS 1.2, the type of signature was implied. If the server certificate included an RSA key, the client knew that the signature was an RSA signature. If the certificate was a DSA key, the client knew to perform a DSA signature check.

This works, but in the long-term is a bit of a burden on the implementer. It would be nice if each signature included an indicator of what type it is; this is exactly what TLS 1.2 added to the inline signatures. Additionally, recall from Listing 8-21 that RSA signatures were RSA-encrypted concatenations of the MD5 hash followed by the SHA-1 hash. TLS 1.2 changes this here, just as it does in the PRF; an RSA signature is an encrypted representation of a single hash — SHA-256 unless a client hello extension has negotiated a different hash. The hash algorithm is also identified in the encrypted data, just like an X.509 signature is. This is redundant; the signature first declares the hash algorithm, and then the signature itself redeclares it. Why was it done this way? DSA has no provision for including a declaration of a hash algorithm, so TLS 1.2 adds it before the signature as well.

Parsing Signature Types

To parse these new signature types, modify the verify_signature code from Listing 8-21 as shown in Listing 9-8 to first read off the hash and signature algorithm and then to ASN.1-decode the decrypted RSA signature value to locate the actual signed hash code. (DSS validation stays the same, as it must.)

Listing 9-8: "tls.c" TLS 1.2 signature verification

int verify_signature( unsigned char *message,

int message_len,

unsigned char *signature,

int signature_len,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

digest_ctx sha_digest;

new_sha256_digest( &sha_digest );

... if ( parameters->server_public_key.algorithm == rsa ) { unsigned char *decrypted_signature; int decrypted_signature_length; struct asn1struct rsa_signature; decrypted_signature_length = rsa_decrypt( signature, signature_len, &decrypted_signature, ¶meters->server_public_key.rsa_public_key ); // TLS 1.2; no longer includes MD-5, just SHA-256, // but the RSA signature also includes the signature scheme, // so must be DER-decoded asn1parse( decrypted_signature, decrypted_signature_length, &rsa_signature ); if ( memcmp( sha_digest.hash, rsa_signature.children->next->data, SHA256_BYTE_SIZE ) ) { asn1free( &rsa_signature ); free( decrypted_signature ); return 0; } asn1free( &rsa_signature ); free( decrypted_signature ); }

Notice that the MD5 computation has been removed here; it's no longer needed. The implementation in Listing 9-8 also completely ignores the declared hash algorithm; it's included as an OID as the first child of the top-level structure. The implementation ought to verify that the declared hash algorithm is SHA-256 and, in theory, compute a separate hash if it isn't. Because no other hash algorithms are supported here, this check is omitted. If the server gives back, say, SHA-384, the hashes don't match and an alert is thrown.

The signature structures also prepend the signature and hash algorithms, but they don't do so as full-blown X.509 OIDs (fortunately). Instead, an enumeration of supported algorithms is declared as shown in Listing 9-9.

Listing 9-9: "tls.h" signature and hash algorithms

typedef enum

{

none = 0,

md5 = 1,

sha1 = 2,

sha224 = 3,

sha256 = 4,

sha384 = 5,

sha512 = 6

} HashAlgorithm; typedef enum { anonymous = 0, sig_rsa = 1, sig_dsa = 2, sig_ecdsa = 3 } SignatureAlgorithm;

This is less extensible, but significantly easier to code, than the X.509 OID structure.

Modify parse_server_key_exchange from Listing 8-19 as shown in Listing 9-10 to read the hash and signature algorithm from the beginning of the packet. Note that this implementation reads, but completely ignores, the declared signature and hash algorithms; a proper, robust implementation verifies that the algorithm is one that has a public key to verify with and, if the hash algorithm is not SHA-256, the implementation computes that hash or throws an alert indicating that it can't.

Listing 9-10: "tls.c" parse_server_key_exchange with signature and hash algorithm declaration

static char *parse_server_key_exchange( unsigned char *read_pos,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

short length;

int i;

unsigned char *dh_params = read_pos;

HashAlgorithm hash_alg;

SignatureAlgorithm sig_alg;

// TLS 1.2 read off the signature and hash algorithm

hash_alg = read_pos[ 0 ];

sig_alg = read_pos[ 1 ];

read_pos += 2;

for ( i = 0; i < 4; i++ )

These changes are necessary to support ephemeral key exchange algorithms. Because the structure of the message itself changes, you must be ready to at least look in a different place for the key exchange parameters.

Finally, remember that if the server wants a client certificate, the client must also send back a certificate verify message with its own signature. To save the client the trouble of sending a certificate whose public key the server cannot use to verify a signature, the certificate request message was changed in TLS 1.2 to include a list of supported signature and hash algorithms. The enumerations from Listing 9-9 are reused here. To properly parse the certificate request, modify the parse_certificate_request routine from Listing 8-29 as shown in Listing 9-11:

Listing 9-11: "tls.c" parse_certificate_request with TLS 1.2 support

#define MAX_CERTIFICATE_TYPES 4

typedef enum

{

rsa_signed = 1,

dss_signed = 2,

rsa_fixed_dh = 3,

dss_fixed_dh = 4

}

certificate_type;

#define MAX_SIGNATURE_ALGORITHMS 28

typedef struct

{

HashAlgorithm hash;

SignatureAlgorithm signature;

}

SignatureAndHashAlgorithm;

typedef struct

{

unsigned char certificate_types_count;

certificate_type supported_certificate_types[ MAX_CERTIFICATE_TYPES ];

unsigned char signature_algorithms_length;

SignatureAndHashAlgorithm

supported_signature_algorithms[ MAX_SIGNATURE_ALGORITHMS ];

}

CertificateRequest;

static unsigned char *parse_certificate_request( unsigned char *read_pos,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

read_pos = read_buffer(

( void * ) &request.supported_certificate_types[ i ], read_pos, 1 );

}

read_pos = read_buffer( &request.signature_algorithms_length, read_pos, 2 );

for ( i = 0; i < request.signature_algorithms_length; i++ )

{

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * )

&request.supported_signature_algorithms[ i ].hash, read_pos, 1 );

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &request.supported_signature_algorithms[ i ].signature, read_pos, 1 ); } read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &trusted_roots_length, read_pos, 2 );

The supported signature/hash algorithms list occurs between the list of supported certificate types and the list of trusted root authorities. The length of the list is declared as being two bytes, even though there are only 7 × 4 = 28 possible combinations of signature and hash algorithms; the length is declared to be this long for future extensibility. In a full-featured implementation, the signature and hash algorithms are used to select an appropriate certificate, end the handshake prematurely, or just decline to supply a certificate and see what happens.

Now, it may occur to you that it's not very fair for the server to list its supported signature and hash algorithms while the client is left at the mercy of whatever the server supports, and you'd be right. RFC 5246 also standardizes a new client hello extension that enables the client to list its supported signature and hash algorithms; this extension takes the same form as the list of signature and hash algorithms in the certificate request (see Listing 8-29). This new extension is extension number 13 and is documented in section 7.4.1.4.1 of the TLS 1.2 specification.

To summarize, TLS 1.2 differs from TLS 1.0, at the message-format level, in the following ways:

- Initialization vectors are explicitly declared at the start of each message for block ciphers.

- The client can negotiate, by way of a new hello extension, a stronger hash algorithm to be used whenever the algorithm itself calls for one.

- The PRF is based on a single hash, rather than a combination of MD-5 and SHA-1. If no stronger hash algorithm is negotiated, the default is SHA-256.

- The finished message's verify data is also based on SHA-256 instead of MD-5 and SHA-1.

- Signatures computed over handshake messages such as the server key exchange and certificate verify declare their hash and signature algorithms explicitly.

The changes described in this section are, at a minimum, what you need to change in order to support TLS 1.2. Of course, there's no significant benefit to making these changes just to upgrade to TLS 1.2 if you don't take advantage of the cool new features that it includes. The following two sections examine the most significant cryptographic advances introduced by TLS 1.2: Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data (AEAD) ciphers and Elliptic-Curve Cryptography (ECC) support.

Adding Support for AEAD Mode Ciphers

TLS 1.0 defined two cipher modes: block and stream. The primary reason for the distinction is that block ciphers need an IV and padding whereas block ciphers don't. TLS 1.2 describes a third cipher mode — Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data (AEAD) — that is often described as combining the authentication with the encryption in one fell swoop. I find this description somewhat misleading; AEAD ciphers encrypt the data and then MAC it, just like block and stream ciphers do. However, the main difference is that an AEAD cipher describes both a protection and an authentication method that must be used as an inseparable unit.

Maximizing Throughput with Counter Mode

Recall from Chapter 2 that the simplest way to apply a block cipher is the electronic code book (ECB) mode: chop the input into blocks and process each one according to the block cipher itself. This mode has some problems, though, because identical input blocks become identical output blocks. Because most block ciphers operate on relatively short block sizes, an attacker can spot a lot of similarities in a large block of plaintext encrypted with a single key. Cipher block chaining (CBC), the preferred mode of SSL and TLS, combats this by XORing each block, before encryption, with the encrypted prior block. Yet another mode, output feedback (OFB), inverts CBC and, rather than encrypting the plaintext and then XORing it with the initialization vector, encrypts the initialization vector over and over again, XORing it with the plaintext and turning a block cipher into a stream cipher.

STREAM CIPHERS VERSUS BLOCK CIPHERS

Stream ciphers have some advantages in some contexts. With stream ciphers, there's no padding, so the ciphertext length is the same as the plaintext length. On the other hand, this can be a vulnerability as well. If the ciphertext is as long as the plaintext, a passive eavesdropper can determine the length of the plaintext, which is a problem in many contexts. In HTTPS, for instance, the browser usually sends a fixed-length block of header and preamble, with the only variable-length part of the request being the page being requested. If an eavesdropper knows the length of the plaintext, he can likely narrow down the actual requested page to a short list. Block ciphers have an advantage because the padding doesn't necessarily have to be the minimum amount that makes a full block; if you need three bytes of padding to satisfy an eight-byte block, you can choose to provide 3, 11, 19, 27, and so on up to 251 blocks of padding to frustrate such an attack.

You could, of course, define a stream cipher that allows optional padding, but that sort of defeats the purpose. The principal benefit of a stream cipher is that you can transmit data as soon as it becomes available and not wait for an entire block.

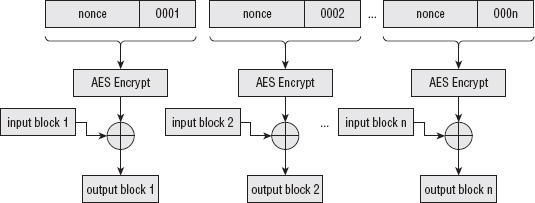

Counter (CTR) mode, illustrated in Figure 9-1, is similar to OFB, but instead of encrypting an initialization vector over and over again, it encrypts a monotonically increasing sequence called a nonce and XOR's that with the plaintext to produce the ciphertext. This approach has an advantage over CBC and OFB because it's infinitely parallelizable. If you have 10 dedicated AES chips that can encrypt a block in a single clock cycle, you can encrypt 10 blocks in a single clock cycle with CTR mode; this is not the case with CBC and OFB because the final output of each block depends on all of the blocks that preceded it. Additionally, if you lose one block somewhere in the middle, you can't recover the following block if you're using CBC and OFB, but you can recover it with CTR mode.

Figure 9-1: Counter mode encryption

Listing 9-12 illustrates how to modify the AES-CBC sample from Listing 2-42 to work in CTR mode.

Listing 9-12: AES-CTR mode

void aes_ctr_encrypt( const unsigned char *input,

int input_len,

unsigned char *output,

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key )

{

unsigned char *nonce = ( unsigned char * ) iv;

unsigned char input_block[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE ]; unsigned int next_nonce; int block_size; while ( input_len ) { block_size = ( input_len < AES_BLOCK_SIZE ) ? input_len : AES_BLOCK_SIZE; aes_block_encrypt( nonce, input_block, key, 16 ); xor( input_block, input, block_size ); // implement CTR memcpy( ( void * ) output, ( void * ) input_block, block_size ); memcpy( ( void * ) &next_nonce, ( void * ) ( nonce + 12 ), sizeof( unsigned int ) ); // Have to preserve byte ordering to be NIST compliant next_nonce = ntohl( next_nonce ); next_nonce++; next_nonce = htonl( next_nonce ); memcpy( ( void * ) ( nonce + 12 ), ( void * ) &next_nonce, sizeof( unsigned int ) ); input += block_size; output += block_size; input_len -= block_size; } }

If you compare Listing 9-12 with Listing 2-42, you notice a few key differences:

- Of course, the IV is referred to as a nonce to fit the terminology used in the CTR-mode specification.

- The input itself is never encrypted; only the nonce is. The input is XORed with the encrypted nonce output.

This function expects to be passed in a 16-byte value, the first 12 bytes of which should be randomly chosen, but not necessarily kept secret, and the last 4 bytes of which should be all zeros. Each block computation is followed by an increment of the nonce; the last 4 bytes are treated as a four-byte integer, incremented, and updated in-place.

Also notice that the input does not need to be block-aligned. CTR mode turns a block cipher into a stream cipher. Because the nonce is the only thing that's encrypted, it's the only thing that has to be an even multiple of the block size. This implementation is hard-coded to use the 128-bit AES encryption algorithm; of course, you can modify this or make it configurable if you are so inclined.

One particularly interesting point about the CTR mode is that the exact same routine is used to decrypt. Recall from Chapter 2 that AES isn't a reversible cipher like DES is, but when you use AES in CTR mode, AES doesn't need to be reversible. Because the counter is what's encrypted at each step, re-creating it and encrypting it again, XORing each such encrypted block with the ciphertext recovers the plaintext. In fact, if you try to use aes_decrypt here, you end up getting the wrong answer.

Nonce selection is crucial with CTR mode, though. You can never, ever reuse a nonce with the same key. In CBC mode, reusing an initialization vector was sort of bad. With CTR mode, it's catastrophic. Consider the CTR-mode encryption of the ASCII string "Hello, World!!" (0x68656c6c6f20776f726c642121) with the key 0x404142434445464748494a4b4c4d4e4f and a nonce of 0x10111213141516. This encrypts, in CTR mode, to 0xfb35f1556ac63f6f226935cd57. So far, so good; an attacker can't determine anything about the plaintext from the ciphertext.

Later, though, you encrypt the plaintext "Known Plaintxt" (0x4b6e6f776e20506c616e747874), which the attacker knows. Using the same key and the same nonce (starting from counter 0), this encrypts to 0xd83ef24e6bc6186c316b259402. Unfortunately, if the attacker now XOR's the first cipher text block with the second, and then XOR's this with the known input, he recovers p1. This attack is illustrated in Table 9-1. This vulnerability has nothing to do with the strength of the cipher or the choice of the key; it's a fixed property of CTR mode itself. As long as you keep incrementing the counter, you're safe. As soon as the counter is reset (or wraps) back to 0, you must change the nonce.

Table 9-1: Recovering unknown plaintext from known plaintext when a nonce is reused

| PURPOSE | VALUE |

| cipher text block 2 (c1) | 0xfb35f1556ac63f6f226935cd57 |

| cipher text block 1 (c2) | 0xd83ef24e6bc6186c316b259402 |

| c1⊕c2 | 0x230b031b010027031302105955 |

| plain text 2 (p2) | 0x4b6e6f776e20506c616e747874 |

| p2⊕c1⊕c2 | 0x68656c6c6f20776f726c642121 |

As usual, the implementation presented by this book completely disregards this critical security advice and reuses the same hardcoded nonce over and over again for the sake of illustration. However, at least you can get around this security hole by making sure never to reuse a nonce. There's another problem with CTR mode that you can't solve, at least not within CTR mode.

Consider the plaintext 0xAB and the CTR-mode key stream byte 0x34. XORed together, they become the cipher text 0xB2. So far, so good; the attacker can't recover the plaintext 0xAB without the keystream byte 0x34 and can't learn anything about the plaintext from the ciphertext. But say that the attacker does know that the first nibble is "A", and he wants to change it to a "C" (pretend this is a really simple protocol where C is an identifier representing the attacker and B is a value indicating that A or C should get a million dollars). Because "A" XOR "C" is "2", he can XOR the first nibble of the cipher text with 2 to produce 0x82. When the recipient decrypts it, he applies the keystream byte 0x34 and reveals 0xCB.

This is called a bit-flipping attack, and CTR mode is particularly vulnerable to it. If the attacker knows part of the plaintext, he can change it to anything he wants by XORing the known plaintext with the desired plaintext and then XORing that with the ciphertext. Of course, you can probably guess the solution: a MAC. This is why AEAD ciphers are so named; they use a cipher mode that must be combined with a MAC function.

Reusing Existing Functionality for Secure Hashes with CBC-MAC

Chapter 4 focuses on HMAC to provide Message Authentication Codes; HMAC is a widely used, intensively scrutinized MAC algorithm. It isn't, however, the only way to generate a secure MAC. Recall from Chapter 4 what sort of qualities you should look for in a good MAC algorithm. It should be impossible:

- To reverse-engineer. Knowing the input and the MAC should not make it any easier to discover the shared MAC key.

- For somebody without the shared key to generate a valid MAC.

- To deliberately construct a message such that it shares a MAC with another message.

- To engineer two separate messages that share a MAC.

Of course, to be cryptographically correct, you must replace the word "impossible" with "computationally infeasible" in the requirements, but this is the essence of a keyed-MAC construction. The second two requirements are met by the use of secure hash algorithms; the first two come from the HMAC construct itself.

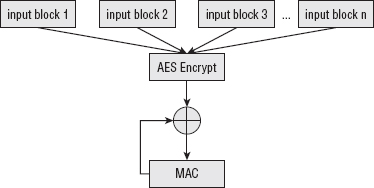

Similar to the concept of using OFB or CTR mode to convert a block cipher into a stream cipher, CBC-MAC converts a block cipher into a secure keyed-MAC construction. The construct itself is simple; you can probably guess how it works. Encrypt the input using the block cipher in CBC mode — start with an IV of all zeros. Throw away all output blocks except the last; this is your MAC. Notice that a secure hash of the input is not computed or required with CBC-MAC. You can actually implement this using the aes_encrypt function from Listing 2-42 directly, but to be a bit more memory efficient, you should write a separate function that only uses a single block of output, as shown in Listing 9-13.

Listing 9-13: aes_cbc_mac

#define MAC_LENGTH 8 void aes_cbc_mac( const unsigned char *key, int key_length, const unsigned char *text, int text_length, unsigned char *mac ) { unsigned char input_block[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE ]; unsigned char mac_block[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE ]; memset( mac_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); while ( text_length >= AES_BLOCK_SIZE ) { memcpy( input_block, text, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); xor( input_block, mac_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); aes_block_encrypt( input_block, mac_block, key, key_length ); text += AES_BLOCK_SIZE; text_length -= AES_BLOCK_SIZE; } memcpy( mac, mac_block, MAC_LENGTH ); }

If you compare Listing 9-13 to Listing 2-42, you see that the only difference here — besides different variable names — is that the output is copied to the same mac_block over and over again. The mac output pointer can't be used for this purpose because it's not guaranteed to be the same length as an AES block; if you need fewer bytes of MAC, you discard the least-significant bytes of the final AES block. Of course, if you need a longer MAC, you must use a different MAC function; the output of the CBC-MAC is bounded by the block size of the underlying block cipher. The process is illustrated in Figure 9-2.

However, CBC-MAC fails to provide all of the requirements for a secure MAC.

- It satisfies the first and second requirements. You cannot discover the key from the output, and somebody without the key cannot generate a valid MAC.

- It fails to satisfy the last two requirements; it is possible to deliberately engineer collisions this way.

Therefore, CBC-MAC must be used with an encryption algorithm; the MAC itself must be protected by a cipher.

Combining CTR and CBC-MAC into AES-CCM

AES-CCM uses AES in CTR mode to achieve encryption and the same algorithm in CBC-MAC mode to achieve authentication (CCM just stands for Counter with CBC-MAC). AES-CCM is specified by the U.S. government's NIST at http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-38C/SP800-38C.pdf. Both encryption and MAC are used with the same key to provide a simultaneously encrypted and authenticated block. The length of the output is the same as that of the input, plus the chosen length of the MAC.

The length of the MAC is variable; as noted previously, you can make it any length you want, up to the length of an AES block. However, both sides must agree, before exchanging any data, what this length is; although the MAC length affects the output, it's not recoverable from the ciphertext. Therefore, the length must generally be fixed at implementation time, or exchanged out of band. To keep things relatively simple, you fix it at eight bytes.

Conceptually, AES-CCM is simple — CTR mode and CBC-MAC are both fairly easy to understand. However, as they say, "the devil is in the details." Actually implementing AES-CCM according to the standard is fairly complex, because everything has to be just-so to achieve proper interoperability. Most of the complexity in CCM surrounds the MAC. Remember from Chapter 4 that a good MAC function must include the length of the input somehow; MD5 and SHA both append a padding block terminated with the length of the input, in bits. This ensures that a single 0 bit MAC's to something different than, say, two 0 bits. CCM uses CBC-MAC with such a length, but the length is prepended rather than appended.

In fact, the first input block to the MAC function is an entire 16-byte block of header information. This header information is never encrypted, but is just used to initialize the MAC. The first byte of this header information declares both the length of the MAC and the number of bytes that encode the length of the input. In other words, if the length of the input is encoded in a four-byte integer, then the first byte of the header block declares "4". (This also means that the length of the input must be known before encryption begins. AES-CCM does not lend itself to "running" computations.)

The remaining 15 bytes of the header block are split between the nonce and the actual length of the input. Therefore, if the number of bytes that encode the length of the input is 4, then the nonce is 11 bytes. The encoding of the first byte is particularly complex, to keep things packed tightly; to simplify, just hardcode the value 0x1F, which declares — in a very roundabout way — that the MAC is 8 bytes long, and the length of the length is also 8 bytes long. This implies that the nonce is 7 bytes long.

Therefore, if the nonce is 0x01020304050607 and the input length is 500 bytes, the header block looks like this:

0x1F 0x01020304050607 0x00000000000001F4

This should be fed into the CBC-MAC function to initialize it. After this initialization is complete, the CBC-MAC function operates on the input exactly as shown in Listing 9-13.

The first "input-length" bytes of output are the CTR-mode encryption of the input itself. The only stipulation that CCM places on the CTR mode is that the first byte of each nonce must be a declaration of the number of bytes that encode the length that was described in the header, followed by the nonce as was declared in the header, followed by an incrementing sequence that starts at 1 (not 0!).

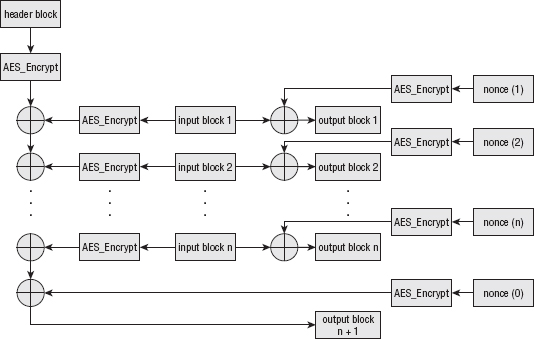

Finally, the last "mac-length" bytes of output are, of course, the MAC, but before the MAC is output, it's counter-mode encrypted itself. It's encrypted with the counter at 0. The whole process is illustrated in Figure 9-3.

If this is not quite clear, the code in Listing 9-14 should clarify.

Listing 9-14: "aes.c" aes_ccm_encrypt

#define MAC_LENGTH 8

/**

* This implements 128-bit AES-CCM.

* The IV is the nonce; it should be seven bytes long.

* output must be the input_len + MAC_LENGTH

* bytes, since CCM adds a block-length header

*/

int aes_ccm_encrypt( const unsigned char *input,

int input_len,

unsigned char *output,

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key )

{

unsigned char nonce[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE ];

unsigned char input_block[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE ];

unsigned char mac_block[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE ];

unsigned int next_nonce;

int block_size;

unsigned int header_length_declaration;

// The first input block is a (complicated) standardized header

// This is just for the MAC; not output

memset( input_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE );

input_block[ 0 ] = 0x1F; // t = mac_length = 8 bytes, q = 8 bytes (so n = 7)

header_length_declaration = htonl( input_len );

memcpy( ( void * ) ( input_block + ( AES_BLOCK_SIZE - sizeof( int ) ) ),

&header_length_declaration, sizeof( unsigned int ) );

memcpy( ( void * ) ( input_block + 1 ), iv, 8 );

// update the CBC-MAC

memset( mac_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE );

xor( input_block, mac_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE );

aes_block_encrypt( input_block, mac_block, key, 16 );

// Prepare the first nonce

memset( nonce, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE );

nonce[ 0 ] = 0x07; // q hardcode to 8 bytes, so n = 7

memcpy( ( nonce + 1 ), iv, 8 );

while ( input_len )

{

// Increment counter

memcpy( ( void * ) &next_nonce, ( void * ) ( nonce + 12 ),

sizeof( unsigned int ) );

// Preserve byte ordering, although not strictly necessary

next_nonce = ntohl( next_nonce );

next_nonce++;

next_nonce = htonl( next_nonce ); memcpy( ( void * ) ( nonce + 12 ), ( void * ) &next_nonce, sizeof( unsigned int ) ); // encrypt the nonce block_size = ( input_len < AES_BLOCK_SIZE ) ? input_len : AES_BLOCK_SIZE; aes_block_encrypt( nonce, input_block, key, 16 ); xor( input_block, input, block_size ); // implement CTR memcpy( output, input_block, block_size ); // update the CBC-MAC memset( input_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); memcpy( input_block, input, block_size ); xor( input_block, mac_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); aes_block_encrypt( input_block, mac_block, key, 16 ); // advance to next block input += block_size; output += block_size; input_len -= block_size; } // Regenerate the first nonce memset( nonce, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); nonce[ 0 ] = 0x07; // q hardcode to 8 bytes memcpy( ( nonce + 1 ), iv, 8 ); // encrypt the header and output it aes_block_encrypt( nonce, input_block, key, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); // MAC is the CBC-mac XOR'ed with S0 xor( mac_block, input_block, MAC_LENGTH ); memcpy( output, mac_block, MAC_LENGTH ); return 0; }

The first section builds the CCM mode header in the input_block:

memset( input_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); input_block[ 0 ] = 0x1F; // t = mac_length = 8 bytes, q = 8 bytes (so n = 7) header_length_declaration = htonl( input_len ); memcpy( ( void * ) ( input_block + ( AES_BLOCK_SIZE - sizeof( int ) ) ), &header_length_declaration, sizeof( unsigned int ) ); memcpy( ( void * ) ( input_block + 1 ), iv, 8 );

As always, the length of the length must be put in network byte order.

The next section updates the CBC-MAC with this header:

memset( mac_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); xor( input_block, mac_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); aes_block_encrypt( input_block, mac_block, key, 16 );

This is followed by a single loop through the input data that simultaneously performs the CTR-mode encryption and updates the CBC-MAC. This enables the encrypt-and-authenticate process to pass over the data only one time. Because CTR mode encryption encrypts the counter, and CBC-MAC encrypts the input itself, it's necessary to invoke aes_block_encrypt twice inside the loop. If you want to be hyper-efficient, you can modify aes_block_encrypt to accept two inputs and generate two outputs; you can then reuse the key schedule computation.

The order of things in the main loop of Listing 9-14 is only slightly different than those of Listings 9-12 and 9-13 (you may want to compare them before continuing). Because AES-CCM wants the first counter block to have the value of 1, the counter is initialized outside the loop and then incremented at the top instead of after encryption.

Finally, the MAC itself is encrypted in CTR mode with the 0 counter and output:

// Regenerate the first nonce memset( nonce, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); nonce[ 0 ] = 0x07; // q hardcode to 8 bytes memcpy( ( nonce + 1 ), iv, 8 ); // encrypt the header and output it aes_block_encrypt( nonce, input_block, key, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); // MAC is the CBC-mac XOR'ed with S0 xor( mac_block, input_block, MAC_LENGTH ); memcpy( output, mac_block, MAC_LENGTH );

Although counter-mode makes a reversible cipher from any block cipher, you do still need a special decrypt routine for AES-CCM. The encryption routine generates the output and appends a MAC, so the decryption routine must be aware of the MAC and not output it. For robustness, the decryption routine should probably verify the MAC as well. However, the bulk of the routine is the same as the encryption routine, so it makes sense to combine them into one common routine and just pass in a flag indicating which operation is taking place: encrypt or decrypt.

Rename aes_ccm_encrypt to aes_ccm_process and add a decrypt flag to it as shown in Listing 9-15.

Listing 9-15: "aes.c" aes_ccm_process common routine for encrypt and decrypt

int aes_ccm_process( const unsigned char *input,

int input_len,

unsigned char *output,

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key,

int decrypt )

{

...

unsigned int next_nonce; int process_len; int block_size; ... input_block[ 0 ] = 0x1F; // t = mac_length = 8 bytes, q = 8 bytes (so n = 7) process_len = input_len - ( decrypt ? MAC_LENGTH : 0 ); header_length_declaration = htonl( process_len ); ... while ( process_len ) { // Increment counter memcpy( ( void * ) &next_nonce, ( void * ) ( nonce + 12 ), sizeof( unsigned int ) ); ... block_size = ( process_len < AES_BLOCK_SIZE ) ? process_len : AES_BLOCK_SIZE; ... // update the CBC-MAC memset( input_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); memcpy( input_block, decrypt ? output : input, block_size ); xor( input_block, mac_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); ... output += block_size; process_len -= block_size; } ... if ( !decrypt ) { xor( mac_block, input_block, MAC_LENGTH ); memcpy( output, mac_block, MAC_LENGTH ); return 1; } else { xor( input_block, input, MAC_LENGTH ); if ( memcmp( mac_block, input_block, MAC_LENGTH ) ) { return 0; } return 1; } int aes_ccm_encrypt( const unsigned char *input, int input_len, unsigned char *output, void *iv, const unsigned char *key ) { return aes_ccm_process( input, input_len, output, iv, key, 0 ); }

int aes_ccm_decrypt( const unsigned char *input, int input_len, unsigned char *output, void *iv, const unsigned char *key ) { return aes_ccm_process( input, input_len, output, iv, key, 1 ); }

As you can see, most of the changes involve making sure to process only the ciphertext in decrypt mode. The big change is at the end; in decrypt mode, rather than outputting the MAC, you decrypt it and then compare the computed MAC with the one that was received. If they don't match, return false.

Note that there's nothing AES-specific about this routine; for optimum flexibility, you could pass a pointer to a block encrypt function and invoke that for each block. However, CCM with AES has been extensively studied and is believed to be secure; if you swap AES with some arbitrary block cipher function, you may not be so lucky. Your best bet for now is to only use CCM with AES.

Maximizing MAC Throughput with Galois-Field Authentication

CBC-MAC has some theoretical problems, which are not serious enough to discount using it (AES-CCM is actually becoming pretty popular), but the problems are significant enough that professional cryptanalysts have spent effort trying to find improvements. Additionally, recall that one of the benefits of CTR mode is that it's infinitely parallelizable. Unfortunately, CBC-MAC has the same throughput problems that CBC encryption has, so CCM loses one of the main advantages of using CTR mode in the first place.

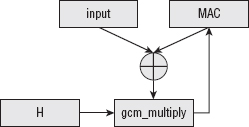

An alternative that avoids the problems with CBC-MAC is the GHASH authentication routine. GHASH is based on Galois-Field (GF) multiplication; i.e. multiplication in a finite field. The idea behind GHASH is to XOR each block with the previous block, but compute the GF(2128) multiplication in the fixed polynomial field x128 + x7 + x2 + x + 1. This may sound somewhat familiar — it's actually the same thing that you did to code the AES matrix multiplication, only it's relative to a different polynomial. The code to perform this multiplication is similar to the dot/xtime computation from Listing 2-36. The only real difference here, other than the new polynomial, is that GHASH computation is done over 128-bit fields rather than only 8.

If all of that doesn't mean much to you, don't worry; you can treat the GHASH function as a black box in the same way you treated the MD5 and SHA functions. It creates a probabilistically unique, impossible-to-reverse output from its input. How it does so is not as important as the fact that it does. Listing 9-16 shows the gf_multiply function.

Listing 9-16: "aes.c" gf_multiply

/** * "Multiply" X by Y (in a GF-128 field) and return the result in Z. * X, Y, and Z are all AES_BLOCK_SIZE in length. */ static void gf_multiply( const unsigned char *X, const unsigned char *Y, unsigned char *Z ) { unsigned char V[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE ]; unsigned char R[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE ]; unsigned char mask; int i, j; int lsb; memset( Z, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); memset( R, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); R[ 0 ] = 0xE1; memcpy( V, X, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); for ( i = 0; i < 16; i++ ) { for ( mask = 0x80; mask; mask >>= 1 ) { if ( Y[ i ] & mask ) { xor( Z, V, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); } lsb = ( V[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE - 1 ] & 0x01 ); for ( j = AES_BLOCK_SIZE - 1; j; j-- ) { V[ j ] = ( V[ j ] >> 1 ) | ( ( V[ j - 1 ] & 0x01 ) << 7 ); } V[ 0 ] >>= 1; if ( lsb ) { xor( V, R, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); } } } }

This is just another variant of the same double-and-add multiplication routine that has come up over and over again throughout this book — the counter variables i and mask iterate over the bits of the input Y and add X to the Z computation whenever the input bit is 1 (you may want to refer to Listing 3-9 for a more detailed look at this format). The only big difference is that X — which is copied into the temporary variable V at the start of the routine — is right-shifted at each step and, if the least-significant bit of X is a 1, X is additionally XORed with the field polynomial 0xE1 × 2120. The value of this polynomial is significant, in the number-theoretic sense, but you can just treat it as a magic constant that you must use to maintain compatibility with other implementations.

The GHASH routine, illustrated in Figure 9-4, takes as input a key that the specification calls H. It computes a variable-length MAC from its input by GF-multiplying each input block by H and XORing all of the resulting blocks to each other. If the last block is not block-length aligned, it's padded with 0's, and there's a single "pseudo-block" trailer that includes the 64-bit length of the input itself.

Figure 9-4: GHASH MAC algorithm

A standalone GHASH implementation is shown in Listing 9-17.

Listing 9-17: "aes.c" ghash

static void ghash( unsigned char *H,

unsigned char *X,

int X_len,

unsigned char *Y ) // Y is the output value

{

unsigned char X_block[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE ];

unsigned int input_len;

int process_len;

memset( Y, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE );

input_len = htonl( X_len << 3 ); // remember this for final block

while ( X_len )

{

process_len = ( X_len < AES_BLOCK_SIZE ) ? X_len : AES_BLOCK_SIZE;

memset( X_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE );

memcpy( X_block, X, process_len );

xor( X_block, Y, AES_BLOCK_SIZE );

gf_multiply( X_block, H, Y );

X += process_len;

X_len -= process_len;

}

// Hash the length of the ciphertext as well memset( X_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); memcpy( X_block + 12, ( void * ) &input_len, sizeof( unsigned int ) ); xor( X_block, Y, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); gf_multiply( X_block, H, Y ); }

As you can see, it's not too complex after you've gotten gf_multiply working. The input is gf_multiply'ed, one block at a time, and each resulting block is XOR'ed with the last. Here, the block size is hardcoded as AES_BLOCK_SIZE because this is used in the context of AES. The terse variable names presented here match the specification so you can easily compare what this code is doing with what the specification declares.

Combining CTR and Galois-Field Authentication with AES-GCM

AES-GCM is specified by http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-38D/SP-800-38D.pdf and in more detail in http://www.csrc.nist.gov/groups/ST/toolkit/BCM/documents/proposedmodes/gcm/gcm-revised-spec.pdf. It's a lot like AES-CCM, but it uses GHASH instead of CBC-MAC. It also MAC's the encrypted values rather than the plaintext, so although you can, in theory, try to write one über-routine that encapsulated both, you'd end up with such a mess of special cases it wouldn't really be worth it. AES-GCM also does away with AES-CCM's special header block and starts the encryption on counter block 2, rather than counter block 1; the MAC is encrypted with counter block 1 rather than counter block 0.

Listing 9-18 illustrates a combined CTR/GHASH implementation of AES-GCM. There are a lot of similarities between this and the AES-CCM implementation in Listing 9-14, but not quite enough to make it worth trying to combine them into a single common routine.

Listing 9-18: "aes.c" aes_gcm_encrypt

/**

* This implements 128-bit AES-GCM.

* IV must be exactly 12 bytes long and must consist of

* 12 bytes of random, unique data. The last four bytes will

* be overwritten.

* output must be exactly 16 bytes longer than input.

*/

int aes_gcm_encrypt( const unsigned char *input,

int input_len,

unsigned char *output,

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key ) { unsigned char nonce[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE ]; unsigned char input_block[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE ]; unsigned char zeros[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE ]; unsigned char H[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE ]; unsigned char mac_block[ AES_BLOCK_SIZE ]; unsigned int next_nonce; int original_input_len; int block_size; memset( zeros, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); aes_block_encrypt( zeros, H, key, 16 ); memcpy( nonce, iv, 12 ); memset( nonce + 12, '\0', sizeof( unsigned int ) ); // MAC initialization memset( mac_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); original_input_len = htonl( input_len << 3 ); // remember this for final block next_nonce = htonl( 1 ); while ( input_len ) { next_nonce = ntohl( next_nonce ); next_nonce++; next_nonce = htonl( next_nonce ); memcpy( ( void * ) ( nonce + 12 ), ( void * ) &next_nonce, sizeof( unsigned int ) ); block_size = ( input_len < AES_BLOCK_SIZE ) ? input_len : AES_BLOCK_SIZE; aes_block_encrypt( nonce, input_block, key, 16 ); xor( input_block, input, block_size ); // implement CTR memcpy( ( void * ) output, ( void * ) input_block, block_size ); // Update the MAC; input_block contains encrypted value memset( ( input_block + AES_BLOCK_SIZE ) - ( AES_BLOCK_SIZE - block_size ), '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE - block_size ); xor( input_block, mac_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); gf_multiply( input_block, H, mac_block ); input += block_size; output += block_size; input_len -= block_size; } memset( input_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); memcpy( input_block + 12, ( void * ) &original_input_len, sizeof( unsigned int ) ); xor( input_block, mac_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); gf_multiply( input_block, H, output );

// Now encrypt the MAC block and output it memset( nonce + 12, '\0', sizeof( unsigned int ) ); nonce[ 15 ] = 0x01; aes_block_encrypt( nonce, input_block, key, 16 ); xor( output, input_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); return 0; }

As you can see, the H parameter that GHASH requires is a block of all zeros, AES-encrypted with the shared key.

memset( zeros, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); aes_block_encrypt( zeros, H, key, 16 ); memset( nonce + 12, '\0', sizeof( unsigned int ) );

The CTR-mode computation is identical to that of AES-CCM; the only difference is that the nonce counter starts at 2, rather than at 1. However, the MAC is different: AES-GCM MACs the encrypted output, instead of the plaintext as AES-CCM does. The only potentially confusing line of Listing 9-18, then, is this one:

memset( ( input_block + AES_BLOCK_SIZE ) -

( AES_BLOCK_SIZE - block_size ), '\0',

AES_BLOCK_SIZE - block_size );

Because the MAC is computed over the encrypted output, and input_block currently contains the encrypted output (it was memcpy'd into output on the previous line), you can feed this block into the MAC computation. However, the GHASH MAC requires that a non-aligned block be zero-padded, whereas the CTR mode just drops any unused output. This complex line, then, zero pads the final block, if needed. Otherwise, this looks just like the GHASH computation in Listing 9-17, with somewhat more meaningful variable names.

Finally, the trailer is appended to the MAC:

memset( input_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); memcpy( input_block + 12, ( void * ) &original_input_len, sizeof( unsigned int ) ); xor( input_block, mac_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); gf_multiply( input_block, H, output );

Note that original_input_len is given in bits, not bytes — hence the << 3 at the start of the function.

Finally, the whole MAC is CTR-mode encrypted with nonce 1 (not nonce 0, as it was with AES-CCM), and output as the final block:

memset( nonce + 12, '\0', sizeof( unsigned int ) ); nonce[ 15 ] = 0x01; aes_block_encrypt( nonce, input_block, key, 16 ); xor( output, input_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE );

Of course, it's not particularly useful to write an encryption routine without a decryption routine. As with AES-CCM, decrypting is pretty much the same as encrypting, you just have to remember to authenticate the last block rather than decrypting and outputting it. In fact, the changes to support decryption in aes_gcm_process in Listing 9-19 are nearly identical to those to apply the same change to aes_ccm_process in Listing 9-15.

Listing 9-19: "aes.c" aes_gcm_process with encrypt and decrypt support

int aes_gcm_process( const unsigned char *input,

int input_len,

unsigned char *output,

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key,

int decrypt )

{

...

int original_input_len;

int process_len;

int block_size;

...

memset( nonce + 12, '\0', sizeof( unsigned int ) );

process_len = input_len - ( decrypt ? AES_BLOCK_SIZE : 0 );

// MAC initialization

memset( mac_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE );

original_input_len = htonl( process_len,, 3 );

...

while ( process_len )

{

...

block_size = ( process_len < AES_BLOCK_SIZE ) ? process_len : AES_BLOCK_SIZE;

aes_block_encrypt( nonce, input_block, key, 16 );

xor( input_block, input, block_size ); // implement CTR

memcpy( ( void * ) output, ( void * ) input_block, block_size );

if ( decrypt )

{

// When decrypting, put the input – e.g. the ciphertext -

// back into the input block for the MAC computation below

memcpy( input_block, input, block_size );

}

// Update the MAC; input_block contains encrypted value

memset( ( input_block + AES_BLOCK_SIZE ) -

...

process_len -= block_size;

}

... memset( nonce + 12, '\0', sizeof( unsigned int ) ); nonce[ 15 ] = 0x01; if ( !decrypt ) { gf_multiply( input_block, H, output ); // Now encrypt the MAC block and output it aes_block_encrypt( nonce, input_block, key, 16 ); xor( output, input_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); } else { gf_multiply( input_block, H, mac_block ); // Now decrypt the final (MAC) block and compare it aes_block_encrypt( nonce, input_block, key, 16 ); xor( input_block, input, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); if ( memcmp( mac_block, input_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ) ) { return 1; } } return 0; } int aes_gcm_encrypt( const unsigned char *input, int input_len, unsigned char *output, void *iv, const unsigned char *key ) { return aes_gcm_process( input, input_len, output, iv, key, 0 ); } int aes_gcm_decrypt( const unsigned char *input, int input_len, unsigned char *output, void *iv, const unsigned char *key ) { return aes_gcm_process( input, input_len, output, iv, key, 1 ); }

AES-CCM and AES-GCM are fairly simple to understand, but not necessarily simple to implement, due to the required precision surrounding their associated MACs. Fortunately, once you get the details all worked out, you can treat the functions as black boxes — plaintext goes in, ciphertext comes out. As long as you're careful to ensure that nonces are never reused with a single key, you can be confident that the encrypted data is safely protected.

Authentication with Associated Data

By now you may be wondering, "If AEAD stands for Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data, what's the associated data part?" The Associated Data is data that should be authenticated along with the encrypted data, but not itself encrypted. If you remember the use of the MAC in TLS 1.0, it MAC'ed one additional piece of data that was not transmitted — the sequence number — and some that were transmitted but not encrypted. Because the main upside of AEAD is to incorporate the authentication into the encryption, you need to replicate the authentication of the original TLS 1.0 MAC.

The associated data, if present, is MAC'ed before the rest of the data stream, but in the case of CCM, after the header block. In order to process associated data during AES-CCM or AES-GCM, make the changes shown in Listing 9-20 to the encrypt and decrypt routines.

Listing 9-20: "aes.h" AES-CCM and AES-GCM with associated data support

int aes_ccm_encrypt( const unsigned char *input,

const int input_len,

const unsigned char *addldata,

const int addldata_len,

unsigned char output[],

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key )

{

return aes_ccm_process( input, input_len, addldata, addldata_len,

output, iv, key, 0 );

}

int aes_ccm_decrypt( const unsigned char *input,

const int input_len,

const unsigned char *addldata,

const int addldata_len,

unsigned char output[],

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key )

{

return aes_ccm_process( input, input_len, addldata, addldata_len,

output, iv, key, 1 );

}

int aes_gcm_encrypt( const unsigned char *plaintext,

const int input_len,

const unsigned char *addldata, const int addldata_len, unsigned char output[], void *iv, const unsigned char *key ) { return aes_gcm_process( input, input_len, addldata, addldata_len, output, iv, key, 0 ); } int aes_gcm_decrypt( const unsigned char *input, const int input_len, const unsigned char *addldata, const int addldata_len, unsigned char output[], void *iv, const unsigned char *key ) { return aes_gcm_process( input, input_len, addldata, addldata_len, output, iv, key, 1 ); }

Now modify aes_ccm_process and aes_gcm_process to accept and authenticate the associated data. This is not too terribly complex; you just run the associated data through the MAC computation before beginning the encrypt/MAC process. The only complicating factor for CCM is that the first two bytes of the first block of associated data must include the length of the additional data. Remember that every time you MAC anything, you must include the length of what you're MAC'ing in the processing somehow to ensure that two inputs of differing lengths whose trailing bytes are all zeros MAC to different values (if the reason for this isn't clear, you might want to jump back and briefly review Chapter 4). AES-CCM with additional data support is shown in Listing 9-21.

Listing 9-21: "aes.c" aes_ccm_process with associated data

int aes_ccm_process( const unsigned char *input,

int input_len,

const unsigned char *addldata,

unsigned short addldata_len,

unsigned char *output,

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key,

int decrypt )

{

...

memset( input_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE );

input_block[ 0 ] = 0x1F; // t = mac_length = 8 bytes, q = 8 bytes (so n = 7)

input_block[ 0 ] |= addldata_len ? 0x40 : 0x00; ... xor( input_block, mac_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); aes_block_encrypt( input_block, mac_block, key, 16 ); if ( addldata_len ) { int addldata_len_declare; int addldata_block_len; // First two bytes of addl data are the length in network order addldata_len_declare = ntohs( addldata_len ); memset( input_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); memcpy( input_block, ( void * ) &addldata_len_declare, sizeof( unsigned short ) ); addldata_block_len = AES_BLOCK_SIZE - sizeof( unsigned short ); do { block_size = ( addldata_len < addldata_block_len ) ? addldata_len : addldata_block_len; memcpy( input_block + ( AES_BLOCK_SIZE - addldata_block_len ), addldata, block_size ); xor( input_block, mac_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); aes_block_encrypt( input_block, mac_block, key, 16 ); addldata_len -= block_size; addldata += block_size; addldata_block_len = AES_BLOCK_SIZE; memset( input_block, '\0', addldata_block_len ); } while ( addldata_len ); } // Prepare the first nonce memset( nonce, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE );

Remember that, in CCM, there was a header that was MAC'ed before the data, and that the first byte of this header was a byte of flags. One of these flags indicates whether to expect associated data. The first change in Listing 9-21 sets the adata flag in the header that indicates that there is associated data in the first place; the remainder of the changes are contained in the if block. This if block just cycles through the additional data supplied (if any) and computes it into the MAC; the only thing that makes this a bit complex is that the first two bytes of the first block must be the length of the additional data, in network byte order.

To see this in action, go ahead and modify the AES test main routine to call aes_ccm_encrypt instead of aes_128_encrypt when the key size is 16 bytes, and add a provision to optionally pass in some additional data as shown in Listing 9-22.

Listing 9-22: "aes.c" main routine modified to accept associated data

#ifdef TEST_AES

int main( int argc, char *argv[ ] )

{

unsigned char *key;

unsigned char *input;

unsigned char *iv;

unsigned char *addl_data;

int key_len;

int input_len;

int iv_len;

int addldata_len;

if ( argc < 5 )

{

fprintf( stderr, "Usage: %s [-e|-d] <key> <iv> <input> [<addl data>]\n",

argv[ 0 ] );

exit( 0 );

}

key_len = hex_decode( argv[ 2 ], &key );

iv_len = hex_decode( argv[ 3 ], &iv );

input_len = hex_decode( argv[ 4 ], &input );

if ( argc > 5 )

{

addldata_len = hex_decode( argv[ 5 ], &addl_data );

}

else

{

addldata_len = 0;

addl_data = NULL;

}

if ( !strcmp( argv[ 1 ], "-e" ) )

{

unsigned char *ciphertext = ( unsigned char * )

malloc( input_len + MAC_LENGTH );

if ( key_len == 16 )

{

aes_ccm_encrypt( input, input_len, addl_data, addldata_len, ciphertext,

( void * ) iv, key );

}

...

else if ( !strcmp( argv[ 1 ], "-d" ) )

{ unsigned char *plaintext = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( input_len – MAC_LENGTH ); if ( key_len == 16 ) { if ( aes_ccm_decrypt( input, input_len, addl_data, addldata_len, plaintext, ( void * ) iv, key ) ) { fprintf( stderr, "Error, MAC mismatch.\n" ); } } ... show_hex( plaintext, input_len - MAC_LENGTH ); free( plaintext ); ... free( iv ); free( key ); free( input ); free( addl_data ); return 0; } #endif

Now, you can see an AES-CCM encryption in action:

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./aes -e "@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNO" "12345678" "tuvwxyz" "abc" 404855688058bb65f9c511

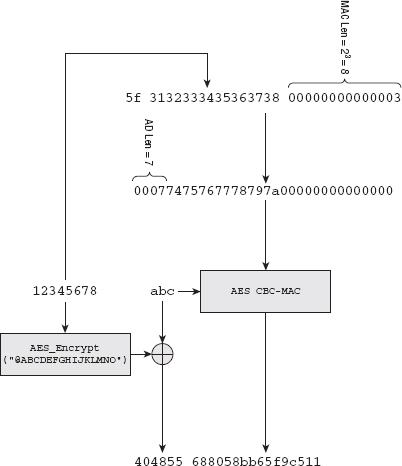

Here, "@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNO" is the key, "12345678" is the nonce, "tuvwxyz" is the associated data, and "abc" is the data to encrypt. The encrypted output — the CTR-mode part — is the three bytes 0x404855. The remainder of the output is the eight-byte MAC 0x688058bb65f9c511. This MAC is computed over first the header block 0x5f313233343536373800000000000003. 0x5F is the declaration that there is associated data, the MAC size is eight bytes, and that the declaration of the length of the input takes up seven bytes. This is followed by the nonce itself and the length of the input — in this case, three bytes. The associated data is then added to the MAC — this is 0x00077475767778797a00000000000000. Notice that the first two bytes are the length of the associated data, followed by the zero-padded associated data itself. Finally, the plaintext input "abc" is added to the MAC (again, zero-padded). This final MAC block is AES-counter-mode encrypted with nonce 0: 0x31323334353637380000000000000000.

This entire operation is illustrated in Figure 9-5.

Figure 9-5: AES-CCM encryption example

Decrypting gives you back the original input:

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./aes -d "@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNO" "123456789012" "tuvwxyz" \ 0x404855688058bb65f9c511 616263

If the MAC is wrong, though, you just get back nothing:

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./aes -d "@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNO" "123456789012" "tuvwxyz" \ 0x404855688058bb65f9c5112 Error, MAC mismatch.

Technically, though, there's nothing stopping you, if you have the key, from writing a CTR-mode decryption routine and decrypting the first three bytes anyway. If you know the MAC is eight bytes, you know the input was three. You can decrypt, but not authenticate, the ciphertext even if you don't know what the additional data was; it's just used in the MAC computation.

AES-GCM with associated data is even easier; there's no length to prepend to the associated data, so you can just incorporate the associated data processing into the MAC just before encryption starts, as shown in Listing 9-23:

Listing 9-23: "aes.c" aes_gcm_process with associated data support

int aes_gcm_process( const unsigned char *input,

int input_len,

const unsigned char *addl_data,

unsigned short addldata_len,

unsigned char *output,

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key,

int decrypt )

{

...

original_input_len = htonl( process_len << 3 ); // remember this for final block

while ( addldata_len )

{

block_size = ( addldata_len < AES_BLOCK_SIZE ) ?

addldata_len : AES_BLOCK_SIZE;

memset( input_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE );

memcpy( input_block, addl_data, block_size );

xor( input_block, mac_block, AES_BLOCK_SIZE );

gf_multiply( input_block, H, mac_block );

addl_data += block_size;

addldata_len -= block_size;

}

next_nonce = htonl( 1 );

...

However, remember from the previous section that the GCM MAC itself included a trailer block whose last eight bytes was the length, in bits, of the MAC'ed data. If you start including additional data in the MAC, you must declare that length as well. Because the trailer block is 16 bytes long, and the last 8 bytes are the length of the ciphertext, you can probably guess that the first 8 bytes are the length of the additional data. Modify aes_gcm_process as shown in Listing 9-24 to account for this.

Listing 9-24: "aes.c" aes_gcm_process with associated data length declaration

int original_input_len, original_addl_len; ... original_input_len = htonl( process_len << 3 ); // remember this for final blockt

original_addl_len = htonl( addldata_len << 3 ); // remember this for final block ... memset( input_block, '\0', AES_BLOCK_SIZE ); memcpy( input_block + 4, ( void * ) &original_addl_len, sizeof( unsigned int ) ); memcpy( input_block + 12, ( void * ) &original_input_len, sizeof( unsigned int ) );

You can see this in action, as well, if you modify the main routine to invoke aes_gcm_encrypt or aes_gcm_decrypt instead of aes_ccm:

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./aes -e "@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNO" "12345678" "tuvwxyz" "abc" 87fd0515d242cf110c77b98055c3ad3196aec6 [jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./aes -d "@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNO" "12345678" "tuvwxyz" \ 0x87fd0515d242cf110c77b98055c3ad3196aec6 616263

Notice that the AES-GCM output for the same input is 8 bytes longer than the AES-CCM output because the AES-GCM routine included a 16-byte MAC, but AES-CCM's was just 8. There's no particular reason why it must be this way. This is the way they're shown in their relative specifications, so they were coded this way here. The MAC-length is variable, but remember that because the length itself is not included anywhere in the output, both sides must agree on what it must be before transmitting any data.

Incorporating AEAD Ciphers into TLS 1.2

AEAD ciphers such as AES-CCM and AES-GCM are just different enough than block and stream ciphers, from the perspective of TLS 1.2, to warrant their own format. Both ciphers examined here are stream ciphers with a MAC, which is just like RC4 with SHA-1. However, AEAD ciphers must also transmit their nonce. Block ciphers do something similar with their IVs; they incorporate padding, but in theory you could implement an AEAD cipher by treating it as a block-ciphered structure with a 0-length input block.

In fact, you could get away with this for AES-CCM. If you declared the cipher as aes_ctr_(en/de)crypt, you could make the MAC function variable and replace the default HMAC operation with a CBC-MAC. This would actually work with the block ciphered encryption structure coded in Listing 6-64. However, this would fail for AES-GCM. AES-GCM computes a MAC over the ciphertext, rather than the plaintext. Although you could probably write code to maintain this as a special case, AEAD ciphers are designed to be treated as a black-box. You give it the plaintext and the key, and it gives you back an arbitrarily sized chunk of data that it promises to decrypt and authenticate, with the key, at a later date. To properly support AEAD, you must treat AEAD ciphers as yet another sort of cipher.

To this end, modify the CipherSuite structure declaration to include a section for AEAD ciphers as shown in Listing 9-25.

Listing 9-25: "tls.h" CipherSuite declaration with AEAD support

typedef struct

{

...

void (*new_digest)( digest_ctx *context );

int (*aead_encrypt)( const unsigned char *plaintext,

const int plaintext_len,

const unsigned char *addldata,

const int addldata_len,

unsigned char ciphertext[],

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key );

int (*aead_decrypt)( const unsigned char *ciphertext,

const int ciphertext_len,

const unsigned char *addldata,

const int addldata_len,

unsigned char plaintext[],

void *iv,

const unsigned char *key );

}

CipherSuite;

Now, to add support for the standardized AES_GCM cipher mode, you must just add another element to the list of cipher suites declared in Listing 6-10. Unfortunately, RFC 5288 assigns the cipher suite ID 0x9C to AES-GCM. Remember that the suites array is positional; if you skip an element, you have to insert a NULL placeholder. Cipher suite ID 0x9C works out to element 156. Prior to this chapter, the last element in this array was 58. To keep up with this method of inserting new ciphers, you'd have to include 98 empty elements in this array. Instead, just expand the list as shown in Listing 9-26.

Listing 9-26: "tls.h" aes-gcm cipher suite

typedef enum

{

...

TLS_DH_anon_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA = 0x003A,

TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 = 0x009C,

MAX_SUPPORTED_CIPHER_SUITE = 0x009D

} CipherSuiteIdentifier

Now, rather than explicitly declaring this new cipher suite in the array initializer, add it to the init_tls call as shown in Listing 9-27.

Listing 9-27: "tls.c" init_tls with AES-GCM cipher suite

void init_tls() { ... // Extra cipher suites not previously declared suites[ TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 ].id = TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_ SHA256; suites[ TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 ].block_size = 0; suites[ TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 ].IV_size = 12; suites[ TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 ].key_size = 16; suites[ TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 ].hash_size = 16; suites[ TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 ].bulk_encrypt = NULL; suites[ TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 ].bulk_decrypt = NULL; suites[ TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 ].new_digest = NULL; suites[ TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 ].aead_encrypt = aes_gcm_encrypt; suites[ TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 ].aead_decrypt = aes_gcm_decrypt; }

This declares the new cipher suite TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256. "But wait," you may be saying, "what is this 'SHA256'? Doesn't AES-GCM declare its own MAC?" It does, in fact; RFC 5288 indicates that the SHA-256 should be used to control the PRF. This is in response to section 5 of RFC 5246, which states

At this point, all that's left to do is invoke the AEAD cipher when such a suite becomes active. This happens in the functions send_message, originally defined in Listing 6-64, and tls_decrypt, originally defined in Listing 6-68. You might want to peek back to their final definitions before continuing. After the digest routines, these are the two most complex functions in this book.

If you recall, send_message first computed a MAC over the data to be sent, prepended with a 64-bit sequence number. It then applies padding as necessary, prepends the IV in the case of a block cipher (TLS 1.1+), and encrypts the plaintext and the MAC before sending. AES-GCM is not much different, but a single call computes the ciphertext and the MAC, and the associated data is the sequence number and the header. The CipherSuite declaration from Listing 9-27 lists the new_digest as NULL, but the hash_size as 16. You can rewrite send_ message to take advantage of this by calculating the associated data whenever the hash_size is non-zero as shown in Listing 9-28.

Listing 9-28: "tls.c" send_message with associated data support

int send_message( int connection,

int content_type,

const unsigned char *content,

short content_len, ProtectionParameters *parameters ) { ... unsigned char *mac = NULL; unsigned char mac_header[ 13 ]; digest_ctx digest; ... active_suite = &suites[ parameters->suite ]; // Compute the MAC header always, since this will be used // for AEAD or other ciphers // Allocate enough space for the 8-byte sequence number, the 5-byte pseudo // header, and the content. // These will be overwritten below if ( active_suite->hash_size ) { int sequence_num; memset( mac_header, '\0', 8 ); sequence_num = htonl( parameters->seq_num ); memcpy( mac_header + 4, &sequence_num, sizeof( int ) ); header.type = content_type; header.version.major = TLS_VERSION_MAJOR; header.version.minor = TLS_VERSION_MINOR; header.length = htons( content_len ); mac_header[ 8 ] = header.type; mac_header[ 9 ] = header.version.major; mac_header[ 10 ] = header.version.minor; memcpy( mac_header + 11, &header.length, sizeof( short ) ); } if ( active_suite->new_digest ) { unsigned char *mac_buffer = malloc( 13 + content_len ); mac = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( active_suite->hash_size ); active_suite->new_digest( &digest ); memcpy( mac_buffer, mac_header, 13 ); memcpy( mac_buffer + 13, content, content_len ); ...

This change just creates a new mac_header buffer and pulls its computation out of the MAC computation so that it's accessible to the AEAD encryption function.

Of course, you must also do the encryption itself. This is a tad complex just because you're indexing into various places in various buffers but ultimately boils down to a call to AEAD encrypt with the plaintext, associated data, nonce, and key previously negotiated. This is shown in Listing 9-29.

Listing 9-29: "tls.c" send_message with AEAD encryption support

...

if ( active_suite->bulk_encrypt || active_suite->aead_encrypt )

{

unsigned char *encrypted_buffer = malloc( send_buffer_size +

active_suite->IV_size +

( active_suite->aead_encrypt ? active_suite->hash_size : 0 ) );

int plaintext_len;

// TODO make this random

memset( parameters->IV, '\0', active_suite->IV_size );

// The first 5 bytes (the header) and the IV aren't encrypted

memcpy( encrypted_buffer, send_buffer, 5 );

memcpy( encrypted_buffer + 5, parameters->IV, active_suite->IV_size );

plaintext_len = 5 + active_suite->IV_size;

if ( active_suite->bulk_encrypt )

{

active_suite->bulk_encrypt( send_buffer + 5,

send_buffer_size - 5, encrypted_buffer + plaintext_len,

parameters->IV, parameters->key );

}

else if ( active_suite->aead_encrypt )

{

active_suite->aead_encrypt( send_buffer + 5,

send_buffer_size - 5 - active_suite->hash_size,

mac_header, 13, ( encrypted_buffer + active_suite->IV_size + 5 ),

parameters->IV, parameters->key );

}

free( send_buffer );

send_buffer = encrypted_buffer;

send_buffer_size += active_suite->IV_size;

}

...

As you can see, other than allocating enough space in the target encryption buffer for the MAC, this isn't that much different than ordinary block cipher encryption.

Decrypting with AEAD cipher support is about the same. First, declare a mac_header independent of the MAC buffer and precompute it. However, remember that the length declared in the MAC header was the length of the data before padding or the MAC was added. For this reason, it's impossible, in the block cipher case, to precompute the MAC header before decrypting the data; you need to know how much padding was added, and you can't do that without decrypting. All this means is that a bit of code — the MAC header computation — must be duplicated in tls_decrypt as shown in Listing 9-30 whereas it was reused in send_message.

Listing 9-30: "tls.c" tls_decrypt with AEAD decryption